1. Introduction

In recent years, environmental challenges and the urgency to reduce harmful emissions have accelerated global efforts toward energy transition and clean power adoption. Within this context, electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as a practical solution, attracting significant interest and progressing rapidly. As EV usage expands worldwide, the demand for charging infrastructure is also growing, raising new concerns regarding maintenance and reliability [

1].

The widespread adoption of EVs has accelerated the development of DC charging infrastructure. Alongside this growth, ensuring safety and reliability through effective fault diagnosis methods has become a critical concern [

2]. DC fast chargers are widely adopted for their efficiency and rapid charging capability; however, they remain vulnerable to open-circuit and short-circuit faults. Operational safety and grid stability are seriously threatened by malfunctions in switching components like DC link or charging capacitors, diodes, Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors (MOSFETs), Insulated-Gate Bipolar Transistors (IGBTs), and damage from external disturbances like lightning strikes [

3,

4].

These faults can cause voltage fluctuations, operational inefficiencies, and significant downtime, resulting in higher maintenance costs and lower service reliability. Traditional fault diagnosis approaches face challenges due to the complex architecture of charging systems, which complicates accurate mathematical modeling and restricts applicability to specific configurations [

5].

Open-circuit and short-circuit diagnosis methods for DC charging piles serve as the main part of power electronic converter fault detection techniques, which are widely classified into two types [

6]: analytical model-based and sample-based diagnostic methods. Harmonic analysis is one of the most important sample-based methodologies for diagnosing faults in microgrid systems, as revealed in recent studies [

7].

Analytical model-based diagnostic methods use analytical knowledge of the system to establish a mathematical model. A state observer is then designed to monitor both the measured output of the system and the predicted output generated by the model. Faults are diagnosed by evaluating the residual difference between these two outputs. This approach is highly effective for systems where accurate models can be derived. However, the development of an appropriate mathematical model for DC charging pile circuits is challenging, thereby limiting the application of analytical model-based fault diagnosis approaches.

Signal-based diagnostic approaches typically use a two-step structure. In the first step, signal analysis algorithms such as the Pike transform [

8], Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [

9], Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) [

10], Empirical Modal Decomposition (EMD) [

11,

12], Improved S-transform, and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) [

13], among others, are used to analyze the signal characteristics of the system failure. In the second stage, classification techniques such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [

14,

15] and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [

16,

17] are used to classify and diagnose the retrieved features. These methods offer benefits such as clear principles, straightforward implementation, little computational demand, and no requirement for extensive sampling. However, the two-step approach increases computational load and may result in inefficiencies, as inaccuracies in preprocessing have a direct impact on feature extraction accuracy, demanding extensive memory resources. This method may also struggle with real-time diagnostics, as sequential processing introduces delays, making it challenging to meet the time-sensitive demands of power electronic systems.

Deep learning-based diagnostic methods include two directions [

18,

19]. The first involves transforming the signal into a feature picture for the deep learning algorithm used in diagnosis. However, this approach is limited by the image generation, storage, and reading procedures, which have a negative impact on the real-time algorithms. Furthermore, the image processing is prone to feature loss, which causes significant data redundancy [

20]. These methods have benefits in terms of automation, precision, and scalability, but constraints such as high data requirements, computing demands, and lack of interpretability necessitate careful consideration of their applicability for power electronic converter diagnostics. They are frequently weighed against more interpretable or computationally efficient methods. The second direction involves using the deep learning algorithm to directly extract the one-dimensional signal features for diagnosis, but this method cannot completely maximize the parallel processing capabilities of the deep learning algorithm [

21]. Threshold-based diagnostic methods have been shown to detect switch faults in grid-connected converters with latencies on the order of milliseconds; for example, switch fault diagnosis in a 3-phase AC-DC PWM converter within about 4 ms using a calculated threshold independent of load conditions [

22]. Recent advances in THD-based and FLL-based protection techniques have demonstrated the effectiveness of SOGI-FLL or MSOGI-FLL structures for grid-side disturbance detection, voltage quality monitoring, or communication-less protection in microgrids [

5,

23]. These approaches primarily rely on THD estimation, frequency deviation, or MSOGI-based voltage observers to detect anomalies in distribution networks, but they do not classify internal converter faults or distinguish between multiple fault locations.

In response to these challenges, signal-based diagnostic methods offer a promising alternative by directly analyzing fault-related signals.

This study examines the use of the THD estimation technique in conjunction with the SOGI–FLL. The THD method is effective at identifying harmonic distortions that indicate open and short-circuit faults in real time. The integrated technique provides a dependable method of problem identification and isolation, resulting in safer operation and more effective maintenance of DC charging systems. Unlike existing diagnostic frameworks—which primarily focus on grid-side disturbance detection, voltage-quality monitoring, or communication-less protection in microgrids—the proposed method performs explicit fault classification inside the Vienna rectifier. Moreover, the same approach can be applied to faults in other power-electronic circuits, including converters, rectifiers, and many similar systems.

Prior approaches do not distinguish between open-circuit and short-circuit faults within the power converter or identify which component has failed. In contrast, our work combines SOGI-FLL based THD estimation with frequency and amplitude tracking to extract fault-specific signatures that clearly separate and identify the faults.

2. System Description and Diagnostic Methodology

2.1. Circuit Topology of DC Charging Pile (Vienna Rectifier)

A three-phase, three-level Vienna rectifier, which offers excellent efficiency, less harmonic distortion, and power factor correction, is typically used in the front-stage circuit of the majority of charging modules that are currently on the market. The backstage generally incorporates an isolated high-frequency DC/DC converter to enable power conversion and electrical isolation. This work concentrates on potential faults occurring in the front-stage, particularly within the Vienna rectifier and the charging capacitors.

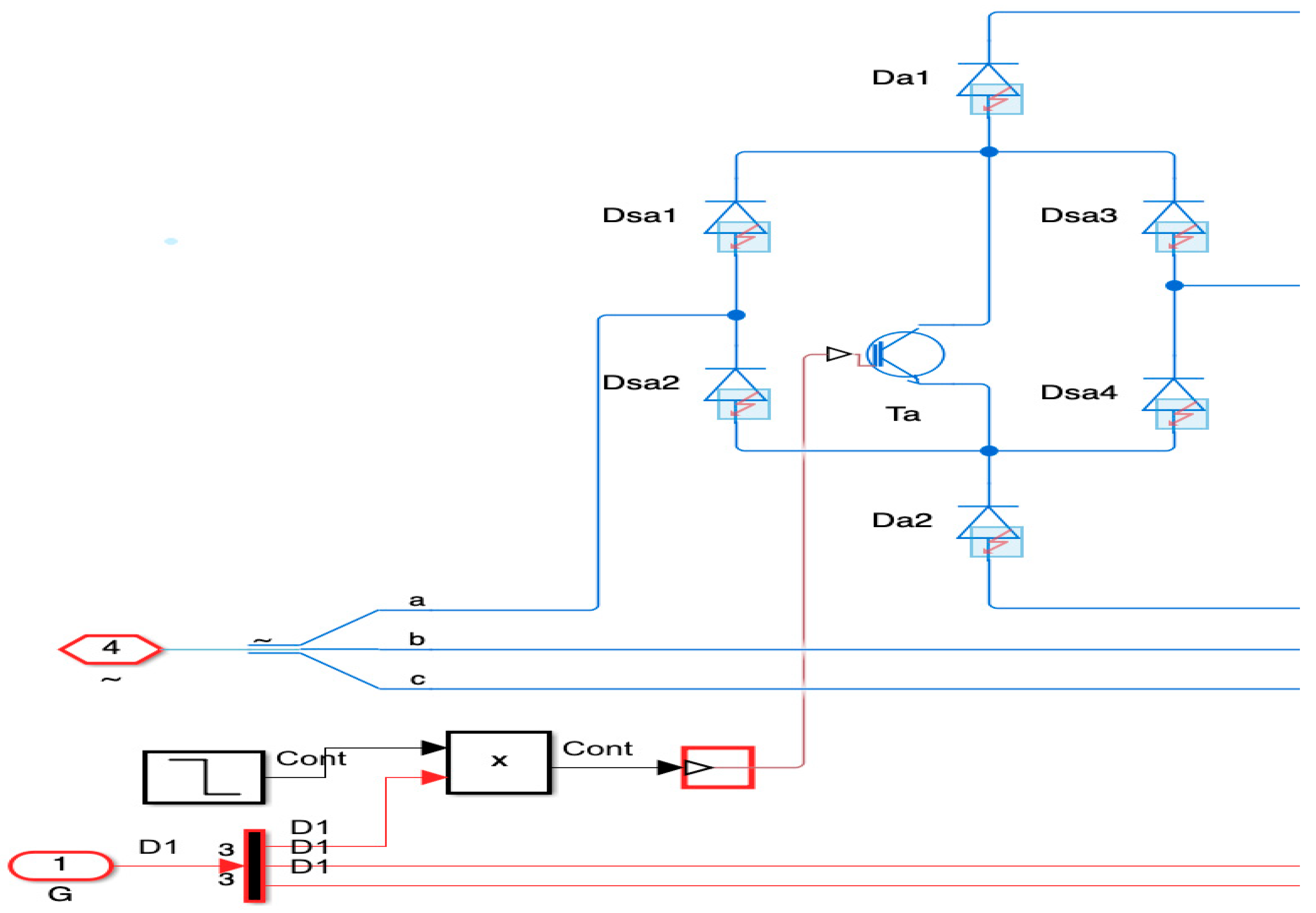

This setup has various advantages, including low harmonic production, a high-power factor, increased safety, adaptability to input voltage changes, and fewer power devices. These characteristics make it an ideal topology for fault diagnosis analysis. The circuit structure is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The front-stage rectifier consists of three-phase input inductors (La, Lb, Lc), three-phase power modules (Sa, Sb, Sc), and DC-side capacitors (C1, C2). Each phase of the front-stage power modules is identical and includes the fully controlled switching device T, four shunt diodes (Ds1, Ds2, Ds3, Ds4), and two clamping diodes (D1, D2), respectively. These components are arranged symmetrically across phases a, b, and c. The circuit topology is shown in

Figure 2.

2.2. Fault Types in the Vienna Rectifier in the DC Charging Pile

In this paper, we study the diagnosis of open-circuit and short-circuit faults in the front stage of the DC charging pile (Vienna rectifier) for electric vehicles.

Among the different fault scenarios simulated in Vienna rectifiers, real-world reliability studies of DC fast-charging stations identify certain faults as the most probable due to the operational conditions and nature of the hardware involved. Among these, open-circuit faults in electrolytic DC-link capacitors are the most frequently encountered. The high ripple currents, thermal cycling, and aging effects inherent in fast-charging environments place tremendous stress on these capacitors, accelerating their degradation and resulting in an increased rate of open-circuit faults and performance degradation problems over time [

24].

In addition to capacitors, open-circuit or degraded semiconductor switches—including IGBTs and diodes—represent another significant fault category. These devices are vulnerable to electrical overstress, transient surges, manufacturing variances, and repeated thermal cycling, any of which may lead to both intermittent and permanent open-circuit failures. Practical research and diagnostic implementations have confirmed the existence of such defects, especially as systems age or operate in harsh environmental conditions [

25,

26].

Short-circuit faults in diodes and switches are statistically less common than open-circuit failures, but they are critical because they can cause catastrophic system damage. Such faults are most commonly caused by insulation failure, high overcurrent events, or poor handling during installation or maintenance, resulting in abrupt protection trips or complete system shutdowns [

25], and more maintenance work and manpower are required for power companies.

The scientific literature thus confirms that DC-link capacitor failures are the major real-world concern with Vienna rectifiers, followed by switch and diode defects, with each demanding strong safety methods and regular condition monitoring for reliability in DC charging applications [

24,

25,

26].

In this study, fault conditions were introduced after the system reached a steady-state operating condition to ensure accurate fault characterization and a clear distinction of fault signatures. For simulating the open-circuit (OC) fault in the IGBT, a step signal was applied to the gate terminal during normal operation, and the gate signal was subsequently removed at the fault instant to emulate an open-circuit condition across the device. The open-circuit fault in the DC-link capacitor was realized using a circuit breaker (CB) that opens at a predefined time to represent capacitor disconnection. Similarly, both open-circuit (OC) and short-circuit (SC) faults in the diodes were simulated using the fault configuration parameters available within the respective block settings. Introducing these faults after steady-state operation allows for more different fault waveforms and facilitates a more reliable analysis of the system’s transient and steady-state responses under different fault scenarios.

According to the location of the component within the Vienna rectifier, where the open/short circuit fault occurs, the faults are classified into a total of seven categories, as shown in

Table 1.

Open-circuit and short-circuit faults may occur within the Vienna rectifier of the charging module circuit. The three-phase currents (

,

, and

) flowing through the inductor

exhibit the fault-related characteristics of the fault of the front-stage circuit, which can be used for diagnosing faults of the Vienna rectifier circuit components [

13]. In this study, the Vienna rectifier is simulated, followed by the DC side capacitor and a simple resistive load.

The load side consists of a split DC-link configuration, consisting of two capacitors ( and ) connected in series between the positive and negative rails, with their midpoint connected to the neutral point (0) of the Vienna rectifier. A load resistor is connected across the DC-link, drawing current from the output. The circuit includes voltage sensors ( and ) to monitor the voltages across each capacitor for balancing control, a current sensor to measure the load current, and an additional voltage sensor to monitor the total output voltage.

The three-phase input currents and voltages under normal operating conditions are illustrated in

Figure 3.

Under nominal grid configurations, the observed input phase voltage and current show minor high-frequency ripples overlaid on the 50 Hz fundamental. These ripples are expected and primarily caused by existing grid harmonics (5th/7th, etc.) and a little phase imbalance.

The ripple remains substantially below the fundamental magnitude and within the planned EMI filter bandwidth; thus, it has no impact on power-quality targets (low THD) or front-end stability. In actuality, the SOGI-FLL rejects these components and locks to the fundamental, causing the estimated amplitude and frequency to settle rapidly while the residual ripple remains minimal, as is typical of normal operation [

27].

The fault is simulated as given in

Figure 4, representing an open-circuit fault across the switching devices, including the IGBT and diodes.

2.3. Fault-Diagnostic Method Using SOGI Filter with THD Measurement

This section presents the diagnostic methods for electric vehicle DC charging piles, tailored to the distinct fault characteristics of the Vienna rectifier.

Figure 5 depicts the block diagram of an SOGI-FLL grid monitoring system. In this figure, the SOGI consists of a frequency-adjustable resonator, regulated with a gain of 2ξ (where ξ is the damping factor), to ensure that the output remains synchronized in-phase with the input [

23,

27,

28].

The resonator is made up of two integrators that provide a second output in quadrature phase . The FLL is composed of a simple gradient descent algorithm that adapts the system to the frequency of vin utilizing the SOGI error and output .

The frequency is calculated using the SOGI’s orthogonal voltage components and .

The SOGI produces two orthogonal signals at steady state:

where

is the instantaneous phase angle of the input signal.

The instantaneous frequency

is the rate of change of this phase:

From the two orthogonal signals, the phase derivative and hence frequency can be expressed as follows:

The SOGI in-phase

and quadrature-phase

outputs are used to estimate the grid voltage’s fundamental component as follows:

The FLL calculates the grid frequency from the product of

and

, then normalizes the frequency using the square of

. The FLL can be represented as follows:

where

is the FLL gain and

is the estimated frequency.

Now that the square of

in

Figure 5 is available, the THD [

27] is reduced to

where

.

And the corresponding block diagram is shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 7 indicates a Simulink model of a SOGI-based system for real-time estimation of crucial signal properties such as amplitude, frequency, and total harmonic distortion. The SOGI block isolates the orthogonal components of the input voltage (

and

), which are then used in different computing operations. The amplitude is calculated as the root-sum-square of these components and smoothed with an averaging filter. To calculate the instantaneous frequency, the frequency estimation path multiplies, gains and integrates the orthogonal signals. Meanwhile, the THD estimation branch filters and analyzes the squared signal components to compute the harmonic distortion present in the waveform. Overall, this model provides accurate and dynamic tracking of signal characteristics, making it suitable for fault analysis and resulting in power quality monitoring and grid synchronization applications.

2.4. Simulation and Experimental Analysis

In this section, the dataset is established through the MATLAB Simulink simulation model, charging module circuit topology (Vienna rectifier), and the diagnostic model (THD measurement using SOGI-FLL) is trained and tested. The circuit design parameters are shown in the following

Table 2.

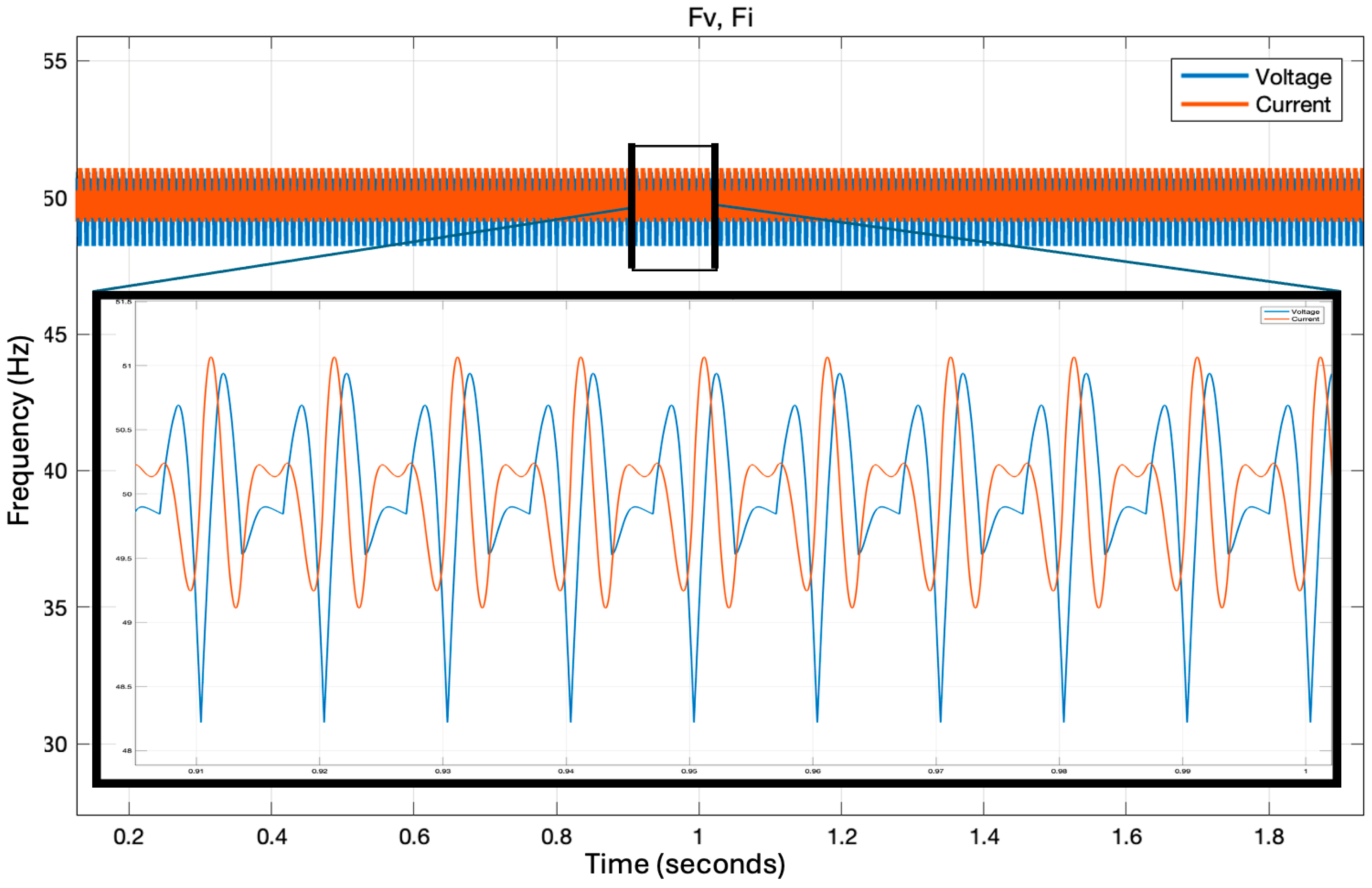

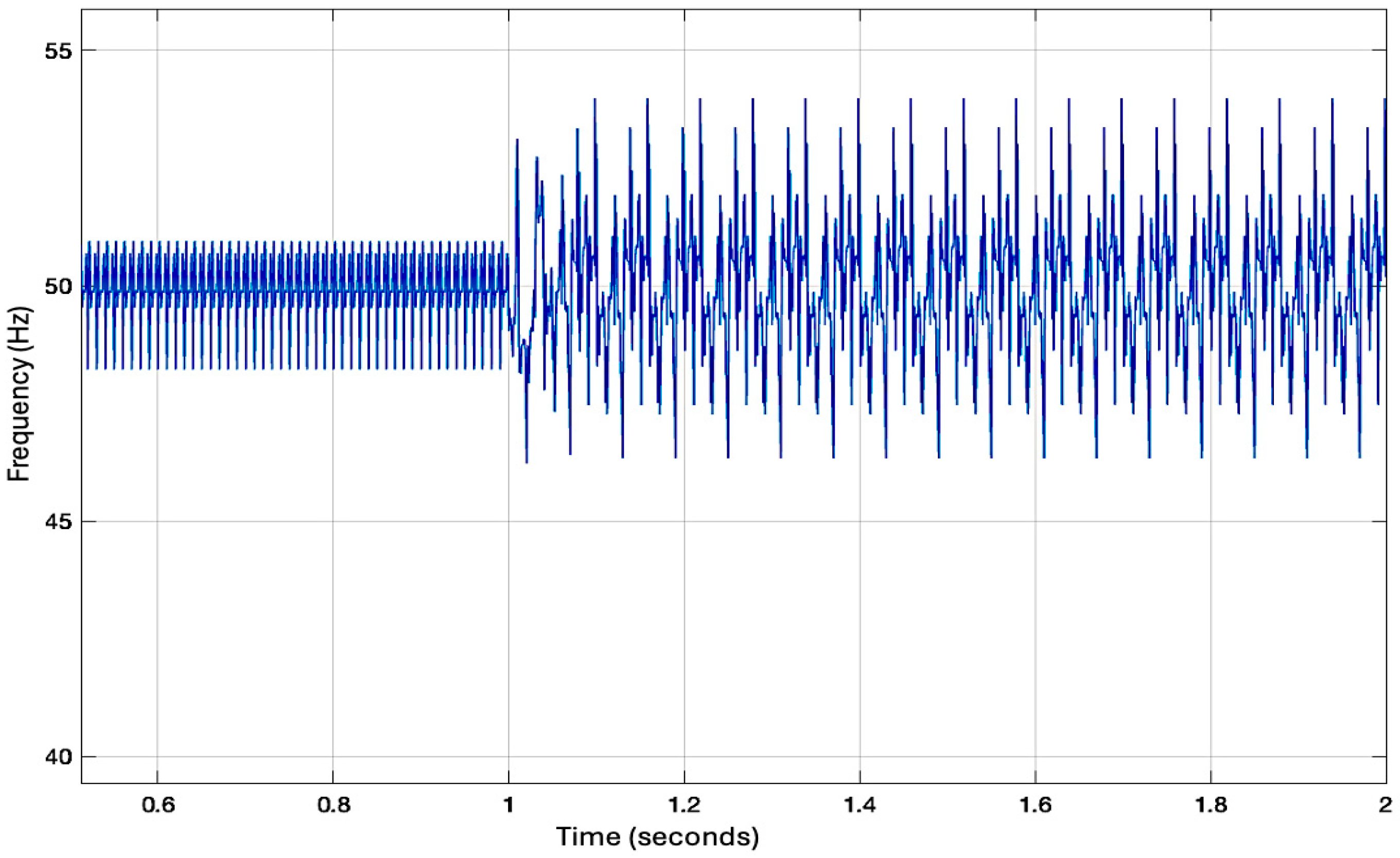

Under normal operating conditions, as shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, the Vienna rectifier demonstrates low and stable THD levels across all frequencies, with a clean harmonic spectrum showing minimal distortion. The frequency tracking performance using SOGI-FLL exhibits stable and accurate tracking at 50 Hz with minimal oscillations and rapid convergence to steady-state operation.

With the chosen parameters, the Vienna rectifier transients settle quickly, and the input voltage and current reach steady state within 0.28 s. The voltage peaks to 0.48 THD at t = 0.035 s, and the current peaks at 0.32 THD at roughly the same time before decaying to their steady values (V = 0.22 THD, I = 0.18 THD), as shown in

Figure 8. This transient peak occurs only during initial startup. Also, the small oscillations observed in

Figure 9 are due to harmonic components in the input signal, which are reflected in the SOGI-FLL output during frequency tracking.

3. Results

Each fault exhibits unique transient and steady-state response characteristics helpful for fault identification and diagnosis, as shown in

Figure 10.

F1 (open-circuit at IGBT and 4 parallel diodes in Phase A): The fault simulates the elimination of the gate signal, resulting in an open circuit across the IGBT and diodes. It causes distorted voltage and current waveforms, increased THD, and variations in frequency and amplitude tracking signals (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). The THD drops to zero for F1 because the open-circuit fault completely interrupts the voltage waveform, resulting in either zero or constant output voltage. Since there are no harmonic components, the computed THD gradually decreases and converges to zero.

F2 (short-circuit at four parallel diodes in Phase A) is a severe fault causing significant waveform distortions, a rapid increase in THD level (~1.0), and instability in frequency and amplitude tracking, indicating a critical fault condition and complete loss of voltage quality.

F3 (open-circuit at upper diode in Phase A) results in asymmetrical waveforms and higher harmonic distortion, affecting the system’s frequency tracking accuracy, as illustrated in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. This results in a moderately high THD = 0.58, indicating a significant but non-catastrophic fault, where the converter still operates but with degraded power quality.

F4 (open-circuit at lower diode in Phase A) fault prevents conduction during the negative half-cycle of phase A, causing a strong waveform asymmetry and large harmonic content—reflected by the high steady-state THD (0.81). It is more severe than the upper-diode open (F3), producing greater voltage distortion, increased DC-link ripple, and extra stress on the remaining switching devices and loss of frequency tracking ability, the same as F3.

F5 (open-circuit at capacitor C1) fault disrupts the DC-link voltage balance, reducing the filtering capability of the converter. As a result, the output voltage exhibits moderate distortion with a steady-state THD of about 0.42, indicating a medium-severity fault that degrades power quality but allows continued, though unbalanced, operation.

F6 (open-circuit at capacitor C2) has similar effects to F5, but in the other capacitor. This fault disturbs the DC-link voltage symmetry, but on the opposite side of the midpoint. The imbalance introduces low-frequency ripple and moderate harmonic distortion, yielding a steady-state THD of about 0.41—signifying a moderate fault that affects voltage stability and waveform quality without causing total system failure.

F7 (open-circuit at both capacitors C1 and C2): This fault removes the DC-link’s entire filtering and energy storage path, causing severe voltage imbalance and pronounced ripple across all phases. The resulting steady-state THD of about 0.46 indicates significant waveform distortion—greater than with a single-capacitor fault—yet slightly lower than phase faults because the converter continues to operate with highly fluctuating frequency, voltage, and current, but a non-collapsed system, as shown in

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18.

Since the fundamental component tends to zero under F1 and our SOGI-based proxy metric μ = e2/A2 behaves poorly when A tends to zero, to prevent division by zero by the block that calculates using the square of the amplitude, the lower bound has been set to saturate to a minimum value, like 0.1; this will avoid the result going to infinity. Also, to avoid this confusion, THD will not be taken into consideration for fault identification. As a result, we have specifically included a guard in the diagnostic logic: the algorithm avoids the THD-based decision by classifying the condition as a voltage collapse/critical fault (F1) based solely on amplitude when the estimated fundamental amplitude falls below a small threshold A.

Under F1, the amplitude-collapse criterion and frequency data are used for classification instead of the THD indicator, which loses its physical significance.

Classification has been made using simple numeric thresholds (derived from plotted steady values):

THD ≥ 0.90–1.0 → F2 (severe/short)

THD ≥ 0.83 → F4 (severe)

THD = 0.50–0.65 → F3 (high)

THD = 0.42–0.47 → F7 (high)

THD = 0.35–0.42 → F5/F6 (moderate)

otherwise → Unknown

The frequency-based classification can be summarized as follows:

|f − 50| ≥ 5 Hz → Critical (F1, F2)

|f − 50| ≈ 3–5 Hz → Severe (F4)

|f − 50| ≈ 2–3 Hz → High (F3, F7)

|f − 50| ≈ 1–2 Hz → Moderate (F5, F6)

|f − 50| < 1 Hz → Healthy/Tolerable

The amplitude-based classification is given below:

Amplitude → < 20% of nominal → Critical (F1)

Amplitude > 40% or spikes > 120% → Severe (F2, F4)

Amplitude ~ 25–40% → High (F3, F7)

Amplitude ~ 10–25% → Moderate (F5, F6)

Amplitude < 10% → Healthy

For each fault, the measured THD, amplitude ripple, and frequency deviation were recorded after transient decay. These values formed tight ranges that were used as classification boundaries. These initial threshold values for fault classification were derived from the steady-state simulation results shown in

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18. The estimated signals (THD, frequency, and amplitude) are being traced by our fault detector, which can allow our methodology to provide almost real-time fault detection in a live operational environment.

The detection time of the proposed diagnostic approach is calculated directly from the simulation using a fixed-step solver, which provides a consistent sample interval for exact timing analysis. The fault classifier output generates a binary detection flag, which has the value “0” during healthy operation and “1” when the algorithm detects a fault. When the fault is injected at a known time

, the simulation reports both the binary flag and the simulation time. The initial rising transition of the detection flag (0→1) is noted in the logged data, with the associated time stamp as

. The fault detection delay is computed as

. The faults description, its classification criteria, and its detection time are given in the following

Table 3.

4. Discussion

The fault assessment framework integrates multiple electrical signal indicators to improve the accuracy and reliability of power system diagnosis. Total harmonic distortion (THD), frequency, and amplitude are assessed with additional indicator for voltage and current measurements, providing more than six distinct input channels to the detection module. These signals are processed by a fault detector configured with a 5% tolerance margin, allowing the system to distinguish between normal fluctuations and genuine anomalies. By simultaneously analyzing deviations from these parameters, the detector can determine not only the fault type but also its severity. This dual-output structure provides a more complete characterization of disturbances and supports faster maintenance decisions, improving overall fault-management robustness in power grids.

Figure 19 shows the block diagram of the fault detector designed to detect faults.

THD should not be used as a stand-alone screening tool for fault detection, as some faults produce similar THD levels. It needs to be complemented by additional analyses such as frequency tracking and amplitude monitoring. Frequency tracking detects dynamic shifts and transient behaviors, serving as a strong indicator for distinguishing short-circuit and open-circuit faults, while amplitude analysis helps resolve subtle differences in signal magnitude and helps differentiate faults occurring in the phase components from those originating in the DC-link capacitors.

Together, these three measures form a comprehensive multi-parameter fault detection approach that improves accuracy, fault discrimination, and reliability beyond what THD alone can provide. This layered methodology is supported by simulation results and practical diagnostic strategies in Vienna rectifier systems. Therefore, THD complemented with frequency and amplitude analyses improve the fault discrimination and diagnostic accuracy.

For the event, where three parameters are not sufficient to clearly distinguish among the faults (for example F5 and F6), to enhance selectivity, the mid-point voltage imbalance can be incorporated into the proposed framework, defined as follows:

In the extended diagnostic logic, is evaluated only after the THD/frequency/amplitude criteria have identified the fault as capacitor-related. The sign and amplitude of are utilized to distinguish between open-circuits in , and simultaneous failures of the capacitors (F5, F6, and F7). This extra indicator significantly lowers ambiguity among these fault modes, improving the proposed method’s overall classification accuracy even under non-ideal operating conditions.

The final framework is shown in the given

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 presents the complete decision flow of the proposed fault diagnosis framework.

Figure 21 shows the actual implementation in MATLAB.

The flowchart combines THD, frequency deviation, and amplitude ripple thresholds to systematically classify faults (F1–F7) and assess their severity. The proposed voltage-based fault detection algorithm was programmed in MATLAB/Simulink with a real-time signal input. The detection logic is based on threshold-based classification, which allows for immediate identification of the fault type once the measured voltage exceeds the corresponding threshold.

Detection time depends strongly on the characteristics of the specific fault. Faults with sharp transients excite fast harmonics, resulting in the shortest detection time, while less abrupt waveform changes produce longer delays. The fastest observed detection times are around 3 ms, while the slowest can reach 55 ms. This variation is mainly dictated by how rapidly the fault alters the measurable indicators, rather than by processing speed or inherent limits in the SOGI-FLL estimator itself. The LPF cutoff frequency influences response time; lower values smoothen the THD signal but increase the detection delay. Adaptive tuning is recommended to balance response speed and signal ripple. Ultimately, the detection delay is not critical because the system logs faults for maintenance alerts rather than immediate shutdown actions, and system logs can be helpful for manufacturer and maintenance companies.

Compared with conventional FFT-based THD computation, the proposed SOGI-FLL method requires only a few mathematical operations—squaring, low-pass filtering, square-root, and division—resulting in a significantly smaller computational burden and faster online response [

27]. The experimental evaluation in [

27] showed that SOGI-FLL-based THD estimation executes in approximately 354 processor cycles, whereas the FFT-based implementation demands more than 3000 cycles even for 64-sample frames, highlighting the suitability of the proposed approach for real-time digital signal processor (DSP) applications.

For DC charging piles and power converters, signal-based diagnostic techniques that include time-frequency transformations and machine learning have also been suggested. For instance, ref. [

25] combines EMD-based feature extraction with an optimized random forest classifier for Vienna rectifier failures, while [

13] uses an enhanced S-transform and LightGBM to diagnose open-circuit faults in DC charging stations. For multilevel converters and motor-drive systems, similar two-stage pipe-lines—feature extraction by wavelet packets, S-transform, or EMD followed by SVMs, ANNs, or gradient-boosted trees—have been documented [

8,

10,

11]. Although these methods usually result in excellent classification accuracy, they necessitate careful feature set selection, offline training, and extra memory and computing power for feature vectors. In contrast, the suggested approach directly leverages SOGI-FLL outputs and a limited number of analytically defined thresholds, avoiding an explicit feature-extraction and classifier-training stage. This leads to a diagnostic procedure that is simpler to implement in a real-time controller, more completely interpretable, and easier to tune.

In subsequent work, a Monte-Carlo-based validation methodology can be built to improve the diagnostic thresholds’ robustness beyond ideal steady-state settings. Each fault category (F1–F7) and the healthy case would be re-simulated under randomized perturbations that are indicative of actual operating environments in such a framework, and the results may be recorded as datasets. Phase imbalance up to ±3%, tiny load steps around the nominal load, additive sensor noise, parameter drift in the input inductors and DC-link capacitors, and fifth and seventh grid harmonics in the range of 0–5% of the fundamental are some of these perturbations. With special focus on misclassification among capacitor-related faults (F5/F6/F7), the generated dataset would allow analysis of confusion matrixes, detection delays, and false-alarm behavior under healthy but distorted settings. In order to maintain clarity, cases where fixed thresholds are close to their sensitivity limits can be highlighted using typical trends rather than comprehensive statistical tables.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a complete fault detection methodology for DC charging systems that incorporates THD, frequency, and amplitude analysis using a SOGI-FLL structure. The approach accurately distinguishes between open and short circuit problems in the Vienna rectifier and DC-link components. By combining the harmonic distortion index with dynamic amplitude and frequency tracking, the suggested method enables precise and real-time defect identification while remaining computationally simple. The comparison results show that SOGI-FLL-based THD estimates can be implemented efficiently with minimum CPU load, making it a viable alternative to traditional FFT-based techniques.

Although this study focuses on simulation-based validation, the adopted parameters, switching behavior, and signal-processing blocks are consistent with experimentally validated designs from existing literature.

Future work will include comparison with other types of SOGI (double SOGI, SSOGI, and MSOGI), hardware-in-the-loop testing, development of adaptive threshold mechanisms for varying grid conditions, and integration of predictive maintenance strategies. The methodology has strong potential for extension to multi-phase converters, renewable energy interfaces, and motor drive systems where rapid problem identification is critical for preserving dependability and safety.

Also, future research will concentrate on expanding this technology to multi-phase and high-power converter setups, implementing adaptive thresholds for changing grid and load situations, and integrating data-driven predictive maintenance strategies. The technique can also be implemented in digital controllers or edge-computing platforms, allowing for distributed fault monitoring across various power conversion devices, hence improving the robustness and resilience of future smart energy systems.