Assessment of Muscle Activity During Uphill Propulsion in a Wheelchair Equipped with an Anti-Rollback Module

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

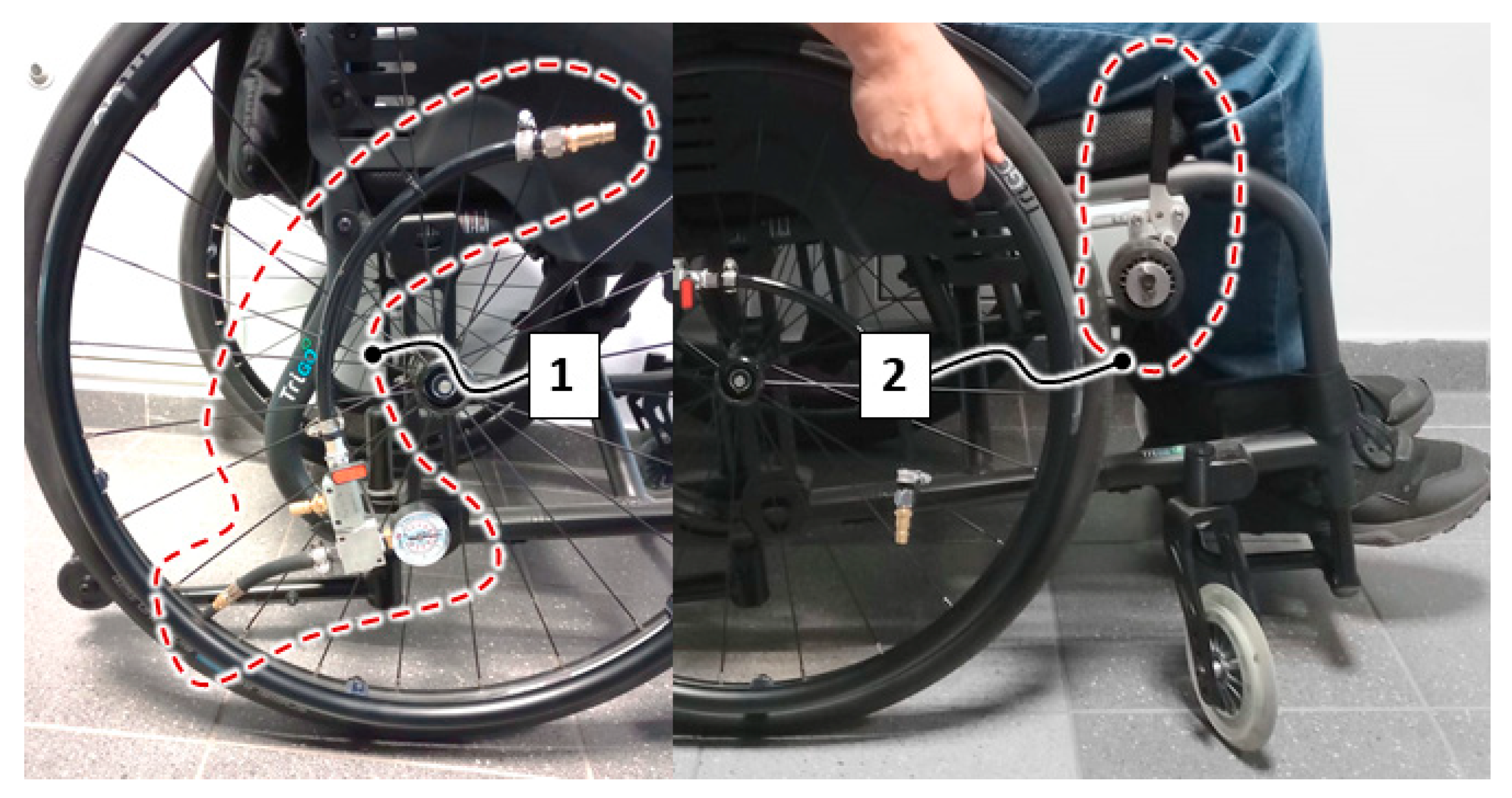

2.1. Materials

2.2. Participants Taking Part in the Tests

2.3. Research Method and Analyzed Parameters

- the number of push cycles required to complete the entire track, NP (section from S to E);

- the duration of a single propulsion cycle, tPC, measured on the incline (section from SS to SE);

- the normalized muscle activity signal for a single propulsion cycle, EMGnorm, measured on the incline (section from SS to SE);

- the normalized cumulative muscle load for a single propulsion cycle, CML, measured on the incline (section from SS to SE);

- the peak-to-mean ratio, PMR, of the EMG signal for a single propulsion cycle during uphill propulsion (section from SS to SE).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CML | Cumulative Muscle Load |

| EAR | Elastic Anti-Rollback module |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| EMGnorm | Normalized Electromyographic Activity |

| EMGmax | Maximum Electromyographic Activity |

| ERC | Musculus extensor carpi radialis |

| ECU | Musculus extensor carpi ulnaris |

| MVC | Maximum Voluntary Contraction |

| NP | Number of Pushes |

| NAR | No Anti-Rollback module |

| PMR | Peak-to-Mean Ratio |

| SAR | Stiff Anti-Rollback module |

| TBM | Caput mediale musculi tricipitis brachii |

| TBL | Caput laterale musculi tricipitis brachii |

| tPC | Push Cycle Time |

| UCL | Upper Confidence Limit |

Appendix A

| Muscle | CML | EMGnorm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | ± | Mean | ± | ||

| NAR | TBM | 41.38 | 10.78 | 0.42 | 0.11 |

| TBL | 59.84 | 20.73 | 0.60 | 0.21 | |

| ECU | 35.81 | 7.72 | 0.36 | 0.08 | |

| ERC | 9.97 | 2.23 | 0.27 | 0.06 | |

| Mean | 36.75 | 8.33 | 0.41 | 0.09 | |

| EAR | TBM | 37.96 | 9.40 | 0.37 | 0.09 |

| TBL | 57.73 | 19.96 | 0.57 | 0.20 | |

| ECU | 36.48 | 6.21 | 0.37 | 0.06 | |

| ERC | 10.85 | 2.52 | 0.32 | 0.07 | |

| Mean | 35.76 | 7.16 | 0.40 | 0.07 | |

| SAR | TBM | 40.15 | 10.79 | 0.42 | 0.11 |

| TBL | 56.20 | 19.02 | 0.57 | 0.19 | |

| ECU | 34.20 | 7.52 | 0.34 | 0.07 | |

| ERC | 10.01 | 1.97 | 0.32 | 0.07 | |

| Mean | 35.14 | 7.45 | 0.41 | 0.07 | |

References

- Fernandes, T. Choosing a Manual Wheelchair: The Options. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2007, 14, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, A.; Malviya, M.; Pandya, R.; Rao, P. Empowering Mobility: Applying Advancements in Walker Design for Differently Abled Individuals. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kamand, India, 24–28 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aissaoui, R. Automatic Filtering and Phase Detection of Propulsive and Recovery Phase during Wheelchair Propulsion. Assist. Technol. Res. Ser. 2010, 26, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.N.; Foglyano, K.M.; Bean, N.F.; Triolo, R.J. Effect of Context-Dependent Modulation of Trunk Muscle Activity on Manual Wheelchair Propulsion. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 100, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slowik, J.S.; Requejo, P.S.; Mulroy, S.J.; Neptune, R.R. The Influence of Wheelchair Propulsion Hand Pattern on Upper Extremity Muscle Power and Stress. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 1554–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amancio, A., Jr.; Leonardi, F.; de Toleto Fleury, A.; Ackermann, M. The Influence of Inertial Forces on Manual Wheelchair Propulsion. In International Symposium on Dynamic Problems of Mechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Part F6; pp. 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, F.K.; Tan, A.M.; Weizman, Y. The Effect of Arm Movements on the Dynamics of the Wheelchair Frame during Manual Wheelchair Actuation and Propulsion. Actuators 2024, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocci, G.; Smalley, C.; Page, A.; Digiovine, C. Manual Wheelchair Propulsion on Ramp Slopes Encountered When Boarding Public Transit Buses. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2019, 14, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Woude, L.H.V.; Vegter, R.J.K.; Hettinga, F.J.; Valent, L.J.; Mason, B.S.; Verellen, J.; De Groot, S. Wheeled Mobility: An Ergonomics Perspective. Assist. Technol. Res. Ser. 2011, 29, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendraoui, N.; Bogard, F.; Murer, S.; Ahram, T.; Taiar, R. Optimization and Ergonomics of Novel Modular Wheelchair Design. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2018, 588, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Alonazi, M.; Abdelhaq, M.; Al Mudawi, N.; Algarni, A.; Jalal, A.; Liu, H. Robust Human Locomotion and Localization Activity Recognition over Multisensory. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1344887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Miyazaki, K.; Shiotani, M.; Symonds, A.; Holloway, C.; Suzuki, T. A Basic Study on Temporal Parameter Estimation of Wheelchair Propulsion Based on Measurement of Upper Limb Movements Using Inertial Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Budapest, Hungary, 9–12 October 2016; pp. 2729–2733. [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, B.; Warguła, Ł.; Rybarczyk, D. Impact of a Hybrid Assisted Wheelchair Propulsion System on Motion Kinematics during Climbing up a Slope. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deems-Dluhy, S.L.; Jayaraman, C.; Green, S.; Albert, M.V.; Jayaraman, A. Evaluating the Functionality and Usability of Two Novel Wheelchair Anti-Rollback Devices for Ramp Ascent in Manual Wheelchair Users with Spinal Cord Injury. PMR 2017, 9, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R. An Affordable Anti Rollback Brake for Wheelchairs. Assist. Technol. Res. Ser. 2013, 33, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, B.; Kukla, M.; Rybarczyk, D.; Warguła, Ł. Evaluation of the Biomechanical Parameters of Human-Wheelchair Systems during Ramp Climbing with the Use of a Manual Wheelchair with Anti-Rollback Devices. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, B.; Kukla, M.; Warguła, Ł.; Giedrowicz, M.; Rybarczyk, D. Evaluation of Anti-Rollback Systems in Manual Wheelchairs: Muscular Activity and Upper Limb Kinematics during Propulsion. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merletti, R.; Botter, A.; Cescon, C.; Minetto, M.A.; Vieira, T.M.M. Advances in Surface EMG: Recent Progress in Clinical Research Applications. CRB 2010, 38, 347–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laferriere, P.; Lemaire, E.D.; Chan, A.D.C. Surface Electromyographic Signals Using Dry Electrodes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2011, 60, 3259–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.A.A.; De Araújo, C.A.; Dos Santos, S.S. ERGO1 Physical Evaluation and Training for Wheelchair Users. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support, Rome, Italy, 24–26 October 2014; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Peula, J.M.; Urdiales, C.; Herrero, I.; Fernandez-Carmona, M.; Sandoval, F. Case-Based Reasoning Emulation of Persons for Wheelchair Navigation. Artif. Intell. Med. 2012, 56, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.; Gooch, S.D.; Theallier, D.; Dunn, J. Analysis of a Lever-Driven Wheelchair Prototype and the Correlation between Static Push Force and Wheelchair Performance. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 19, 9895–9900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysiuk, Z.; Błaszczyszyn, M.; Piechota, K.; Nowicki, T. Movement Patterns of Polish National Paralympic Team Wheelchair Fencers with Regard to Muscle Activity and Co-Activation Time. J. Hum. Kinet. 2022, 82, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Wakeling, J.; Grange, S.; Ferguson-Pell, M. Coordination Patterns of Shoulder Muscles during Level-Ground and Incline Wheelchair Propulsion. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2013, 50, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Ferguson-Pell, M.; Lu, Y. The Effect of Manual Wheelchair Propulsion Speed on Users’ Shoulder Muscle Coordination Patterns in Time-Frequency and Principal Component Analysis. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 27, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, B.; Warguła, Ł.; Gierz, Ł.; Zharkevich, O.; Nikonova, T.; Sydor, M. Electromyographic Analysis of Upper Limb Muscles for Automatic Wheelchair Propulsion Control. Prz. Elektrotechniczny 2024, 100, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warguła, Ł.; Wieczorek, B.; Krystofiak, T.; Sydor, M. Impact of Surface Finishing Technology on Slip Resistance of Oak Lacquer Wood Floorboards with Distinct Gloss Levels. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 19, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7176-1:2014; Wheelchairs Part 1: Determination of static stability. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/56817.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Bradley, J.V. Complete Counterbalancing of Immediate Sequential Effects in a Latin Square Design. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958, 53, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, B. The Wheelchair Propulsion Wheel Rotation Angle Function Symmetry in the Propelling Phase: Motion Capture Research and a Mathematical Model. Symmetry 2022, 14, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Wakeling, J.; Grange, S.; Ferguson-Pell, M. Changes in Surface Electromyography Signals and Kinetics Associated with Progression of Fatigue at Two Speeds during Wheelchair Propulsion. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2012, 49, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liu, W.; Hitt, J.; Millon, D. Spatial, Temporal and Muscle Action Patterns of Tai Chi Gait. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2004, 14, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subashini, J.M.; Judin, L.G.; Amirdha, S.; Vislavath, S.C.; Palanisamy, R.; Sathiyamoorthy, S.; Veluswamy, P. Durability Design and Construction Enhancement of Textile Electrode Shape on Analysis of Its Surface Electromyography Signal. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, 8, 3458906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sae-lim, W.; Phukpattaranont, P.; Thongpull, K. Effect of Electrode Skin Impedance on Electromyography Signal Quality. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON), Chiang Rai, Thailand, 18–21 July 2018; pp. 748–751. [Google Scholar]

- Warnock, B.; Gyemi, D.L.; Brydges, E.; Stefanczyk, J.M.; Kahelin, C.; Burkhart, T.A.; Andrews, D.M. Comparison of Upper Extremity Muscle Activation Levels between Isometric and Dynamic Maximum Voluntary Contraction Protocols. Int. J. Kinesiol. Sports Sci. 2019, 7, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Beltran Martinez, K.; Golabchi, A.; Tavakoli, M.; Rouhani, H. A Dynamic Procedure to Detect Maximum Voluntary Contractions in Low Back. Sensors 2023, 23, 4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwan, A.; Forrest, S.M.; Holt, C.A.; Whatling, G.M. Can Activities of Daily Living Contribute to EMG Normalization for Gait Analysis? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, M.; Forsman, M.; Enquist, H.; Olsen, H.B.; Søgaard, K.; Sjøgaard, G.; Østensvik, T.; Nilsen, P.; Andersen, L.L.; Jacobsen, M.D.; et al. Frequency of Breaks, Amount of Muscular Rest, and Sustained Muscle Activity Related to Neck Pain in a Pooled Dataset. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraga-García, B.; Lozano-Berrio, V.; Gutiérrez, A.; Gil-Agudo, A.; Del-Ama, A.J. A Systematic Methodology to Analyze the Impact of Hand-Rim Wheelchair Propulsion on the Upper Limb. Sensors 2019, 19, 4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolaccini, G.D.S.; Carvalho Filho, I.F.P.D.; Christofoletti, G.; Paschoarelli, L.C.; Medola, F.O. The Influence of Axle Position and the Use of Accessories on the Activity of Upper Limb Muscles during Manual Wheelchair Propulsion. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2018, 24, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.H.M.; McGill, S.M. Co-Activation Alters the Linear versus Non-Linear Impression of the EMG-Torque Relationship of Trunk Muscles. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, I.M.; Jeng, B.; Silveira, S.L.; Motl, R.W. Push-Rate Threshold for Physical Activity Intensity in Persons Who Use Manual Wheelchairs. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 100, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.D.; Fowler, N.E.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L. The Intra-Push Velocity Profile of the over-Ground Racing Wheelchair Sprint Start. J. Biomech. 2005, 38, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briley, S.J.; Vegter, R.J.K.; Tolfrey, V.L.; Mason, B.S. Propulsion Biomechanics Do Not Differ between Athletic and Nonathletic Manual Wheelchair Users in Their Daily Wheelchairs. J. Biomech. 2020, 104, 109725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, D.H.; Babineau, A.-C.; Champagne, A.; Desroches, G.; Aissaoui, R. Pushrim Biomechanical Changes with Progressive Increases in Slope during Motorized Treadmill Manual Wheelchair Propulsion in Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2014, 51, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, D.; Babineau, A.-C.; Champagne, A.; Desroches, G.; Aissaoui, R. Trunk and Shoulder Kinematic and Kinetic and Electromyographic Adaptations to Slope Increase during Motorized Treadmill Propulsion among Manual Wheelchair Users with a Spinal Cord Injury. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 636319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, S.M.; Tordi, N.; Ruiz, J.; Parratte, B. Changes in Oxygen Uptake, Shoulder Muscles Activity, and Propulsion Cycle Timing during Strenuous Wheelchair Exercise. Spinal Cord. 2007, 45, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, E.; Kloosterman, M.G.M.; Buurke, J.H.; Rietman, J.S.; Janssen, T.W.J. Rolling Resistance and Propulsion Efficiency of Manual and Power-Assisted Wheelchairs. Med. Eng. Phys. 2015, 37, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akima, H.; Maeda, H.; Koike, T.; Ishida, K. Effect of Elbow Joint Angles on Electromyographic Activity versus Force Relationships of Synergistic Muscles of the Triceps Brachii. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.W.; Millikan, T.A.; Carlton, L.G.; Chae, W.; Lim, Y.; Morse, M.I. Kinematic and Electromyographic Analysis of Wheelchair Propulsion on Ramps of Different Slopes for Young Men with Paraplegia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kholinne, E.; Zulkarnain, R.F.; Sun, Y.C.; Lim, S.; Chun, J.-M.; Jeon, I.-H. The Different Role of Each Head of the Triceps Brachii Muscle in Elbow Extension. Acta Orthop. Et Traumatol. Turc. 2018, 52, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, S.-C.; Lee, M.-H. Effect of Wheelchair Seat Height on Shoulder and Forearm Muscle Activities during Wheelchair Propulsion on a Ramp. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2012, 24, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.P.; Wakeling, J.; Grange, S.; Ferguson-Pell, M. Effect of Velocity on Shoulder Muscle Recruitment Patterns during Wheelchair Propulsion in Nondisabled Individuals: Pilot Study. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2012, 49, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafta, H.A.; Guppy, R.; Whatling, G.; Holt, C. Impact of Rear Wheel Axle Position on Upper Limb Kinematics and Electromyography during Manual Wheelchair Use. Int. Biomech. 2018, 5, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, N.; Gorce, P. Surface Electromyography Activity of Upper Limb Muscle during Wheelchair Propulsion: Influence of Wheelchair Configuration. Clin. Biomech. 2010, 25, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, S.; Son, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y. Upper Limb Joint Motion of Two Different User Groups during Manual Wheelchair Propulsion. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2013, 62, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, S.H.; Lee, C.-R. Comparison of Neck and Upper-Limb Muscle Activities between Able-Bodied and Paraplegic Individuals during Wheelchair Propulsion on the Ground. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1473–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kim, H.; Ahn, J.; Park, W. Impacts of Disability Duration and Physical Activity Level on Wheelchair Propulsion Strategies in People with T12/L1 Spinal Cord Injury. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Lübeck, Germany, 9–13 September 2025; Volume 68, pp. 613–614. [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, L.O.; Aronow, H.U.; Kasman, G.S. A Pilot Study to Investigate Shoulder Muscle Fatigue during a Sustained Isometric Wheelchair-Propulsion Effort Using Surface EMG. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2004, 58, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diong, J.; Kishimoto, K.C.; Butler, J.E.; Héroux, M.E. Muscle Electromyographic Activity Normalized to Maximal Muscle Activity, Not to Mmax, Better Represents Voluntary Activation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, N.D.; Kirby, R.L.; Smith, C.; Russell, K.F.J.; Theriault, C.J.; Doucette, S.P. Effect of Seat Height on Manual Wheelchair Foot Propulsion, a Repeated-Measures Crossover Study: Part 2–Wheeling Backward on a Soft Surface. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 17, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, S.; Lu, Y. Dynamics of Vehicle-Pavement Coupled System Based on a Revised Flexible Roller Contact Tire Model. Sci. China Ser. E-Technol. Sci. 2009, 52, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assila, N.; Rushton, P.W.; Duprey, S.; Begon, M. Trunk and Glenohumeral Joint Adaptations to Manual Wheelchair Propulsion over a Cross-Slope: An Exploratory Study. Clin. Biomech. 2024, 111, 106167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.A.; Teodorski, E.E.; Sporner, M.L.; Collins, D.M. Manual Wheelchair Propulsion Over Cross-Sloped Surfaces: A Literature Review. Assist. Technol. 2011, 23, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Code | Age [lata] | Height [m] | Weight [kg] | BMI [kg/m2] | MVC [μV] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBM | TBL | ECU | ERC | |||||

| M01 | 28 | 1.70 | 75 | 26.0 | 18.13 ± 7.76 | 58.23 ± 24.18 | 138.17 ± 57.71 | 373.9 ± 134.88 |

| M02 | 36 | 1.73 | 100 | 33.4 | 40.67 ± 14.64 | 110.88 ± 43.91 | 134.81 ± 39.59 | 212.14 ± 56.50 |

| M03 | 37 | 1.76 | 95 | 30.7 | 49.45 ± 23.22 | 82.75 ± 47.05 | 116.30 ± 110.83 | 437.59 ± 171.73 |

| M04 | 20 | 1.73 | 55 | 18.4 | 104.44 ± 48.05 | 236.17 ± 109.52 | 130.54 ± 45.81 | 274.60 ± 91.82 |

| M05 | 35 | 1.78 | 110 | 34.7 | 91.21 ± 59.00 | 82.19 ± 40.97 | 170.27 ± 46.06 | 108.11 ± 32.07 |

| M06 | 33 | 1.80 | 115 | 35.5 | 52.53 ± 53.57 | 41.36 ± 28.06 | 238.83 ± 140.16 | 299.07 ± 124.65 |

| M07 | 39 | 1.86 | 73 | 21.1 | 25.82 ± 17.39 | 50.14 ± 28.67 | 128.83 ± 55.51 | 223.95 ± 86.12 |

| M08 | 40 | 1.80 | 73 | 22.5 | 49.71 ± 38.25 | 92.86 ± 64.39 | 157.58 ± 93.95 | 202.74 ± 100.84 |

| Mean | 33.5 ± 5.03 | 1.77 ± 0.05 | 87.0 ± 17.61 | 27.79 ± 5.57 | 53.99 ± 24.94 | 94.32 ± 51.67 | 151.92 ± 32.63 | 266.51 ± 87.03 |

| Patient Code | Muscle | NAR | EAR | SAR | Perceived Effort During the Use of the Anti-Rollback Module | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | EMGmax | α | EMGmax | α | EMGmax | |||

| [°] | [μV] | [°] | [μV] | [°] | [μV] | |||

| M01 | ERC | 63.76 | 149 | 71.43 | 195 | 73.33 | 203 | 2 |

| M02 | ERC | 60.36 | 117 | 77.05 | 127 | 65.01 | 115 | 2 |

| M03 | ERC | 82.63 | 364 | 81.55 | 377 | 82.61 | 384 | 4 |

| M04 | ERC | 83.43 | 240 | 82.96 | 235 | 79.78 | 234 | 4 |

| M05 | ERC | 54.59 | 71 | 64.55 | 95 | 66.31 | 102 | 2 |

| M06 | ERC | 66.54 | 129 | 67.06 | 175 | 73.87 | 144 | 3 |

| M07 | TBL | 73.97 | 176 | 78.47 | 183 | 82.70 | 168 | 2 |

| M08 | TBL | 75.06 | 172 | 78.85 | 210 | 84.21 | 225 | 2 |

| Parameter | Variant | Mean | p = 0.05 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of push NP [-] | NAR | 13.4 | [12.89; 13.91] |

| EAR | 14.3 | [13.98; 14.62] | |

| SAR | 14.4 | [14.08; 14.72] | |

| Propulsion cycle time tPC [s] | NAR | 1.22 | [1.16; 1.28] |

| EAR | 1.59 | [1.51; 1.67] | |

| SAR | 1.39 | [1.31; 1.47] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wieczorek, B.; Warguła, Ł. Assessment of Muscle Activity During Uphill Propulsion in a Wheelchair Equipped with an Anti-Rollback Module. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12834. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312834

Wieczorek B, Warguła Ł. Assessment of Muscle Activity During Uphill Propulsion in a Wheelchair Equipped with an Anti-Rollback Module. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12834. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312834

Chicago/Turabian StyleWieczorek, Bartosz, and Łukasz Warguła. 2025. "Assessment of Muscle Activity During Uphill Propulsion in a Wheelchair Equipped with an Anti-Rollback Module" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12834. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312834

APA StyleWieczorek, B., & Warguła, Ł. (2025). Assessment of Muscle Activity During Uphill Propulsion in a Wheelchair Equipped with an Anti-Rollback Module. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12834. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312834