Relationship Between Fault Elements and the Structural Evolution of Strike–Slip Fault Zones: A Case Study from the Ordos Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

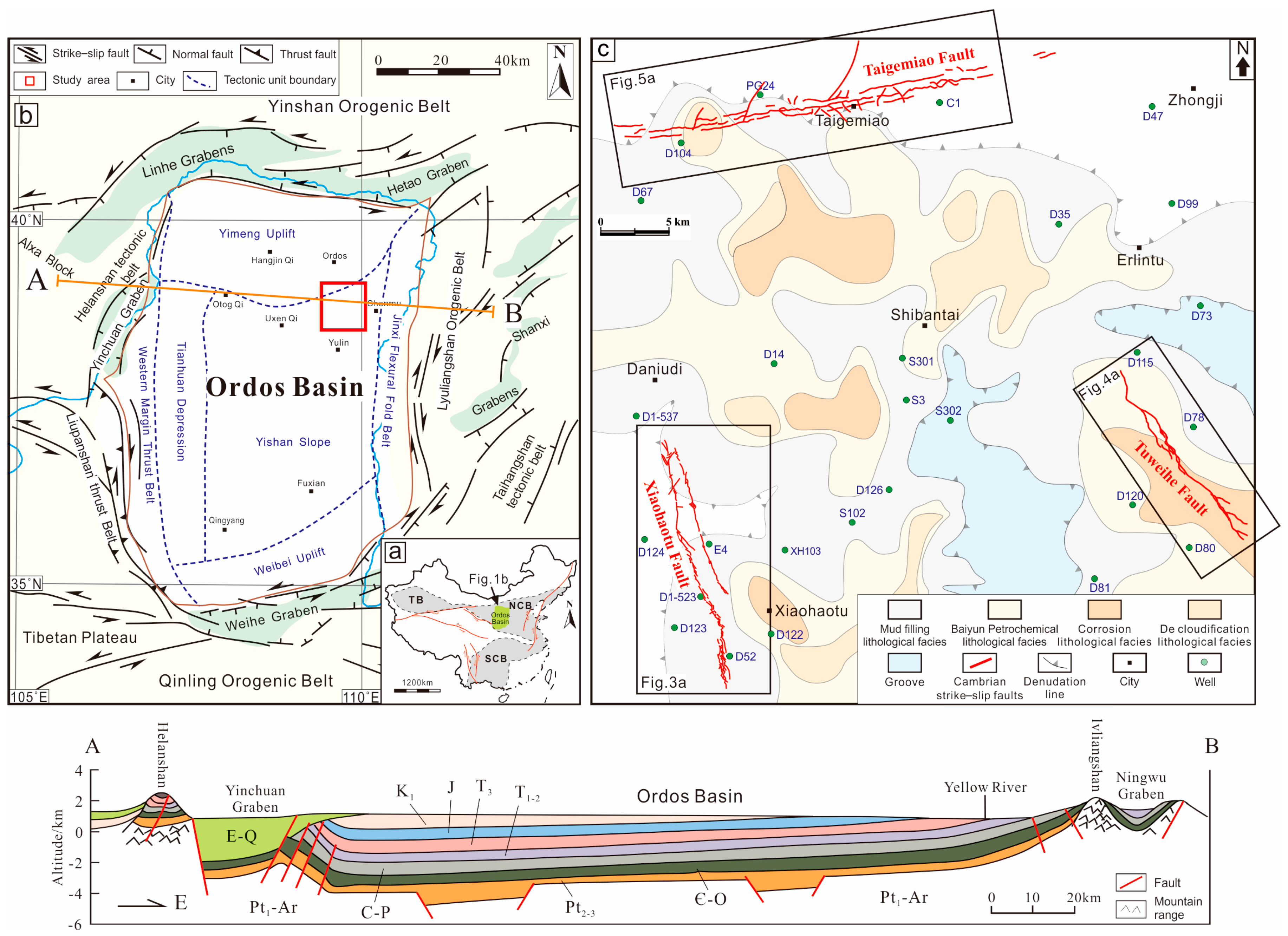

2. Geological Setting

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Measurement Method for Fault Elements

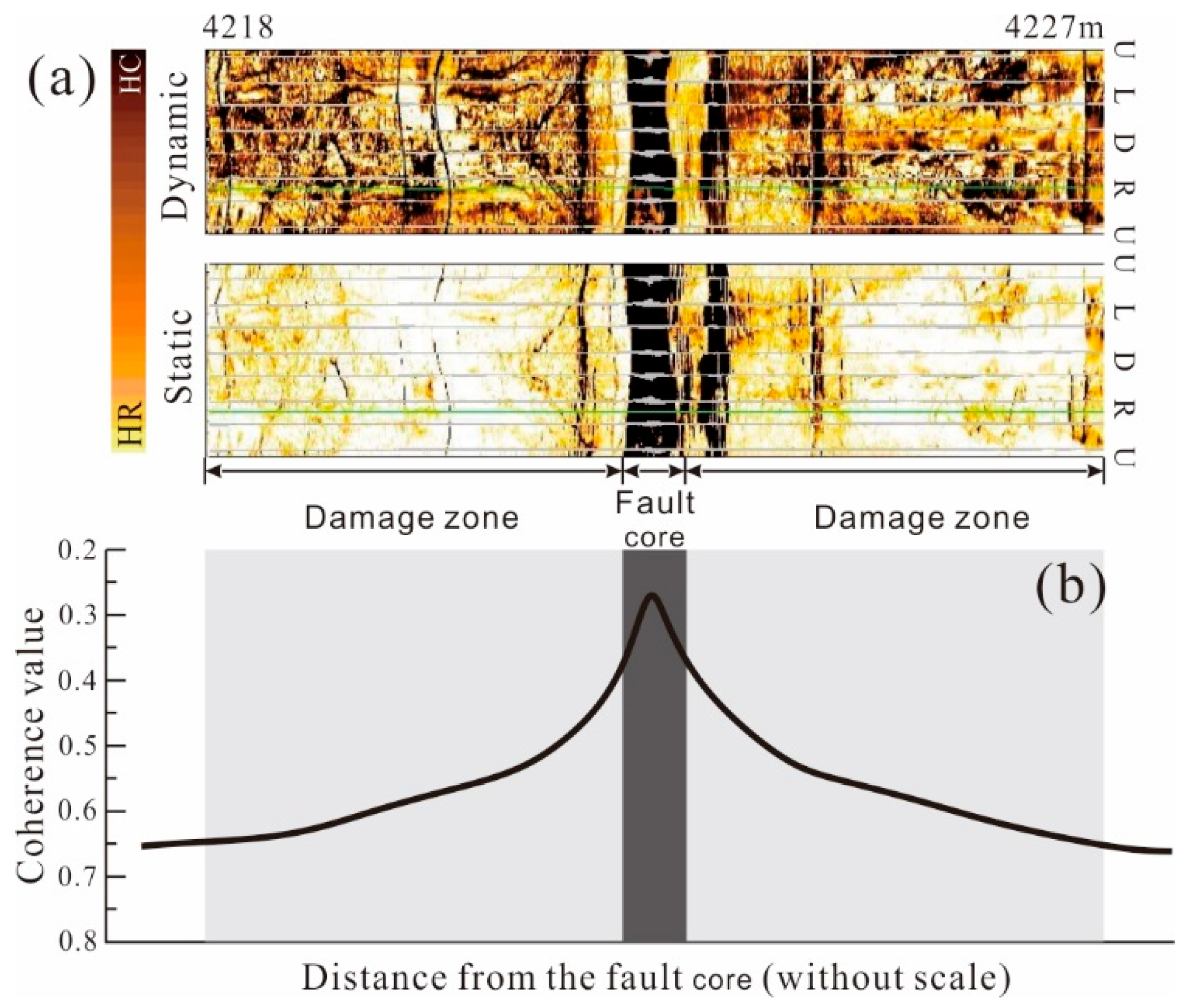

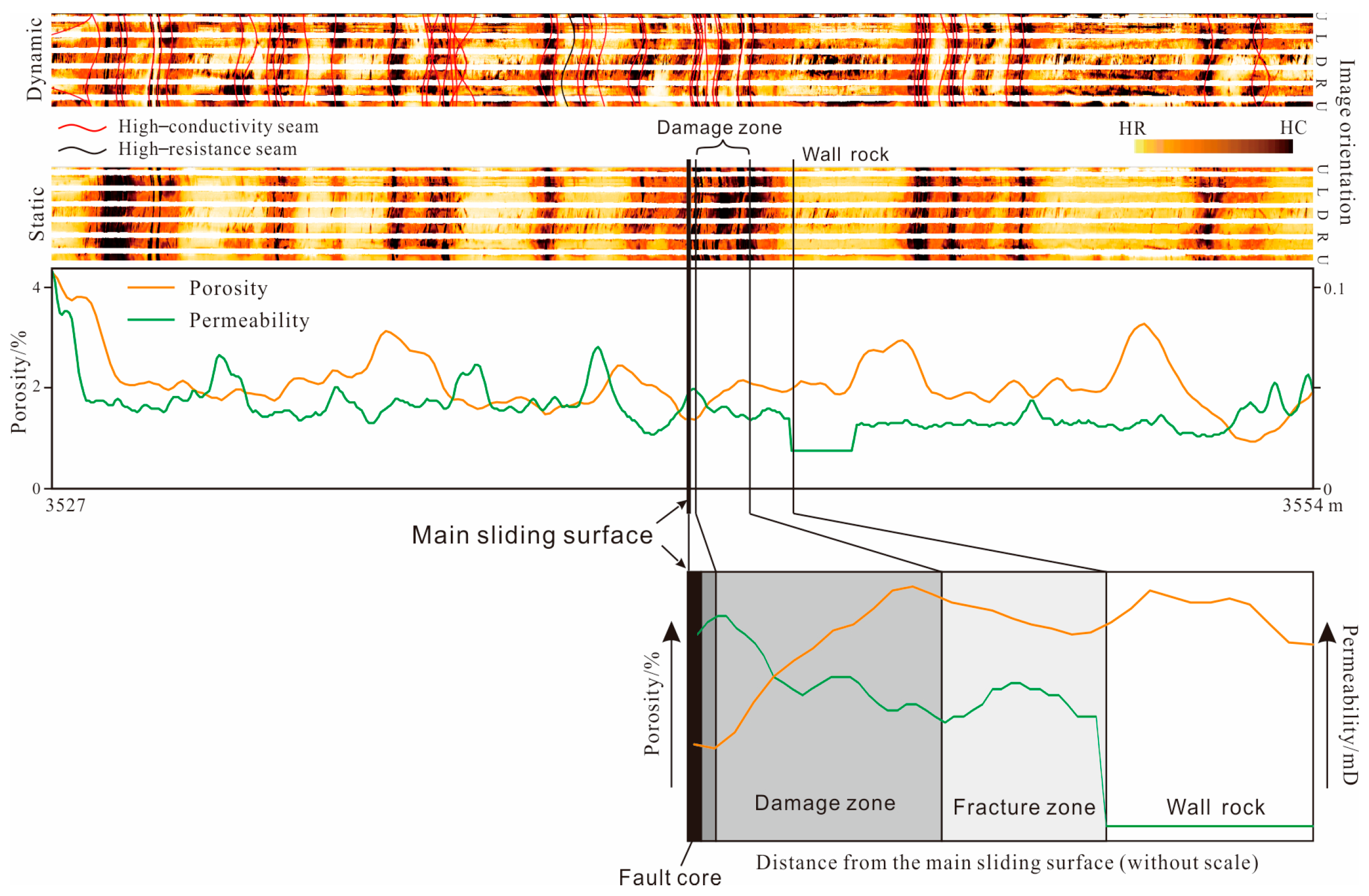

3.1.1. Measurement of Damage Zone Width

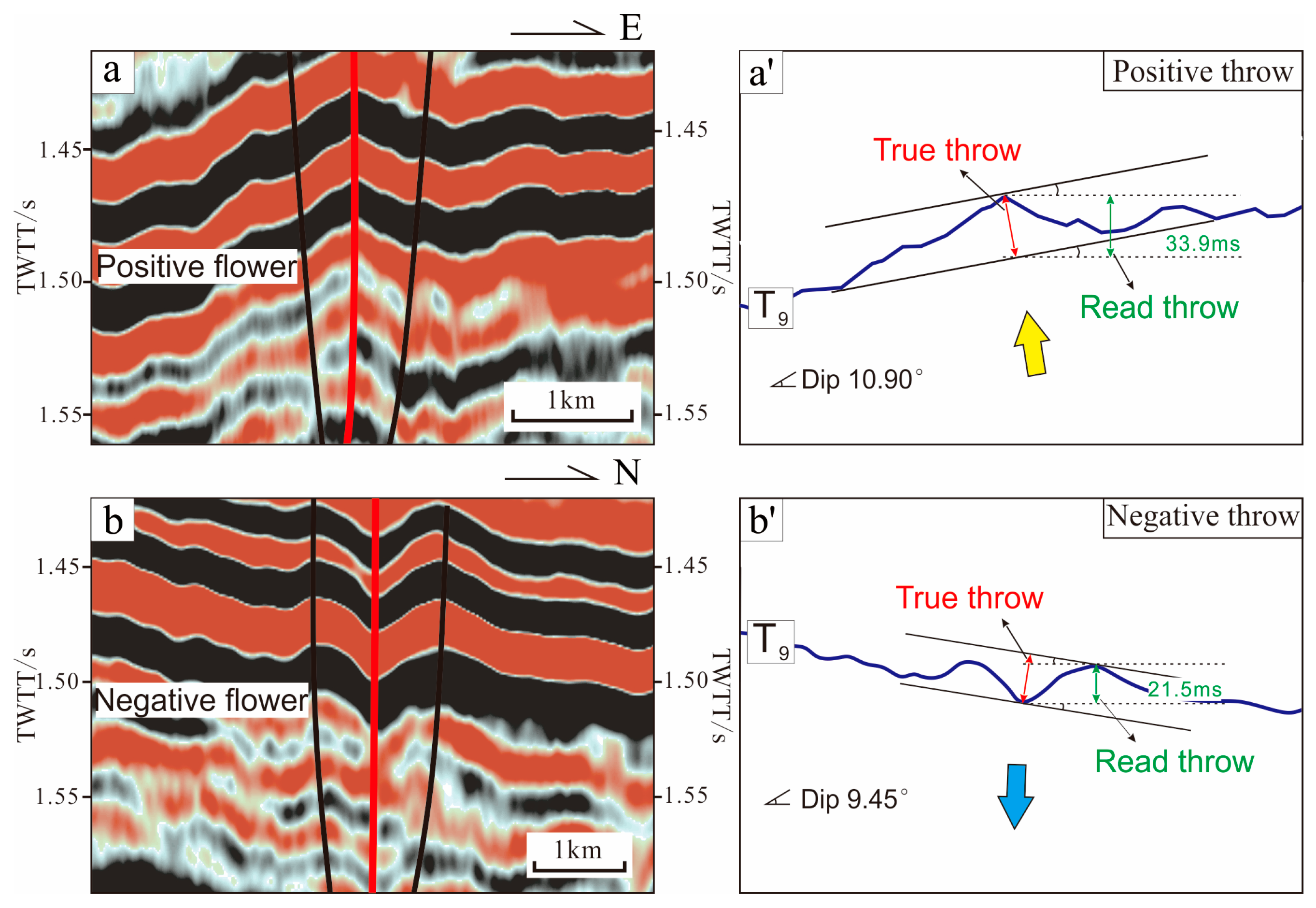

3.1.2. Throw from 3D Seismic Data

4. Results

4.1. Imaging Logging Display of Strike–Slip Fault Zone

4.2. Relationship Between Vertical Displacement and Distance

4.2.1. Xiaohaotu Fault Zone

4.2.2. Tuweihe Fault Zone

4.2.3. Taigemiao Fault Zone

4.3. Fault Damage Zone on Seismic Data

4.4. The Interrelationship Between Fault Elements

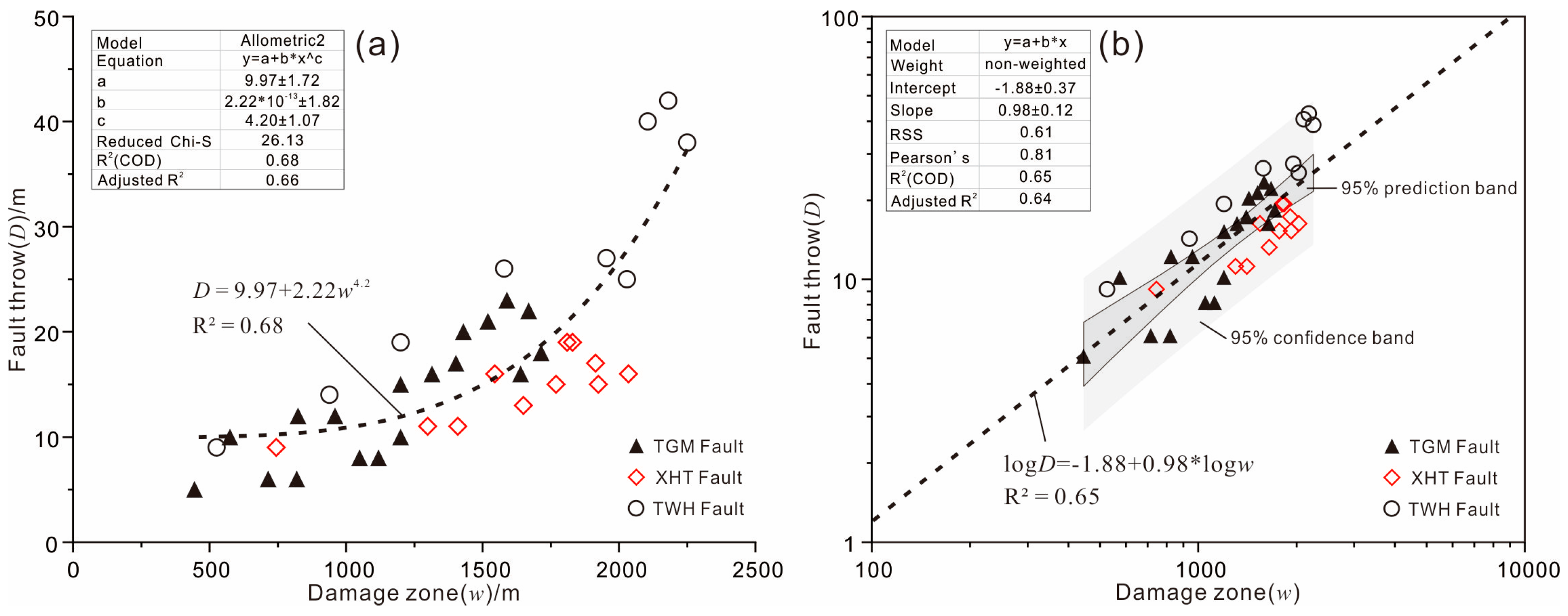

4.4.1. Relationship Between the Fault Damage Zone and Vertical Displacement

4.4.2. Power–Law Relationship and Confidence Interval Among Fault Elements

5. Discussion

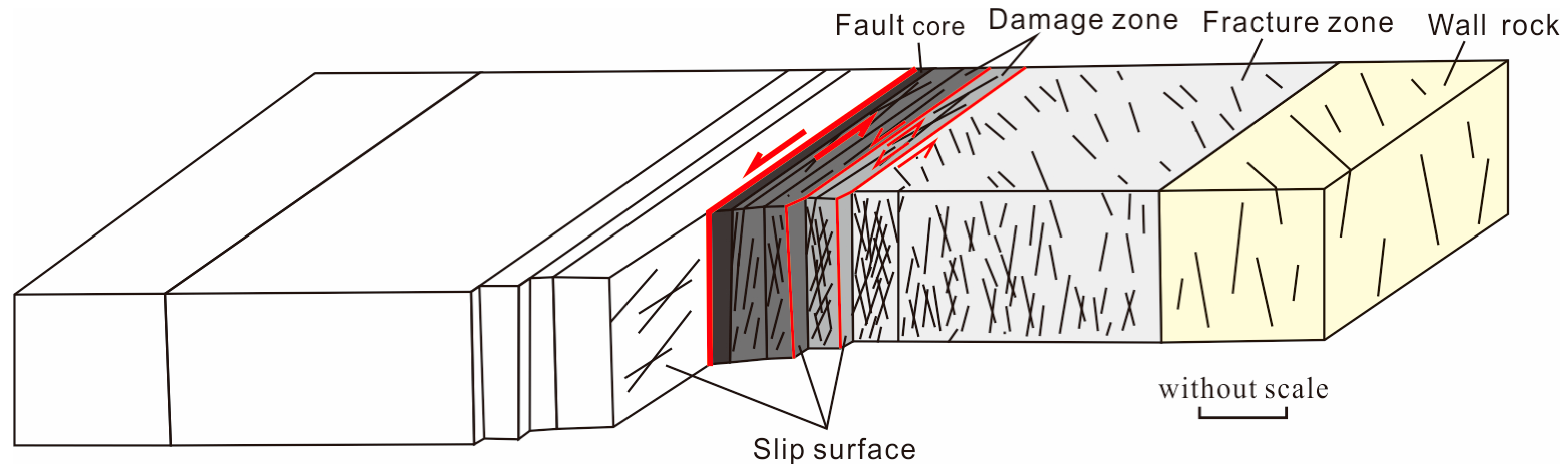

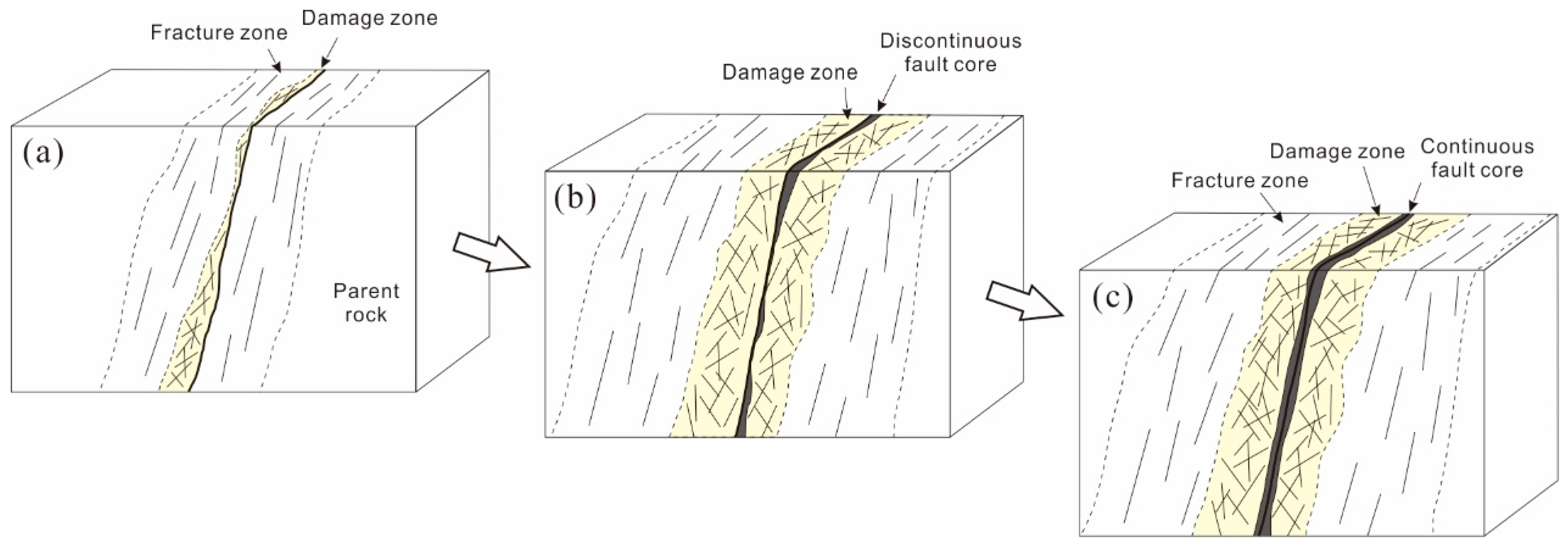

5.1. Development and Evolution Patterns of Strike–Slip Fault Zones

- (1)

- In the early stages of deformation, there is no fault core developed, or it is discontinuously developed. Small and dense fractures form at the deformation site, in the form of en echelon fault zones, with a narrow range of damage zones.

- (2)

- As the displacement increases, the width of the damage zone expands notably, and the originally discontinuous fault core gradually connects. The fault core is dominated by high-permeability fault breccia, surrounded by a damage zone. The density of fractures decreases away from the damage zone, which is the fracture zone. The fault undergoes shear fracturing, forming a typical ternary structure.

- (3)

- The fault zone further evolves, forming a strike–slip fault zone with a distinct ternary structure, namely a continuous fault core, a damage zone, and a fracture zone. The fault core develops fault breccia, fault gouge, or sliding surfaces, and lenses. The width of the damage zone and fracture zone increases slightly, and the range of fault zone modification of the reservoir is the largest (Figure 11).

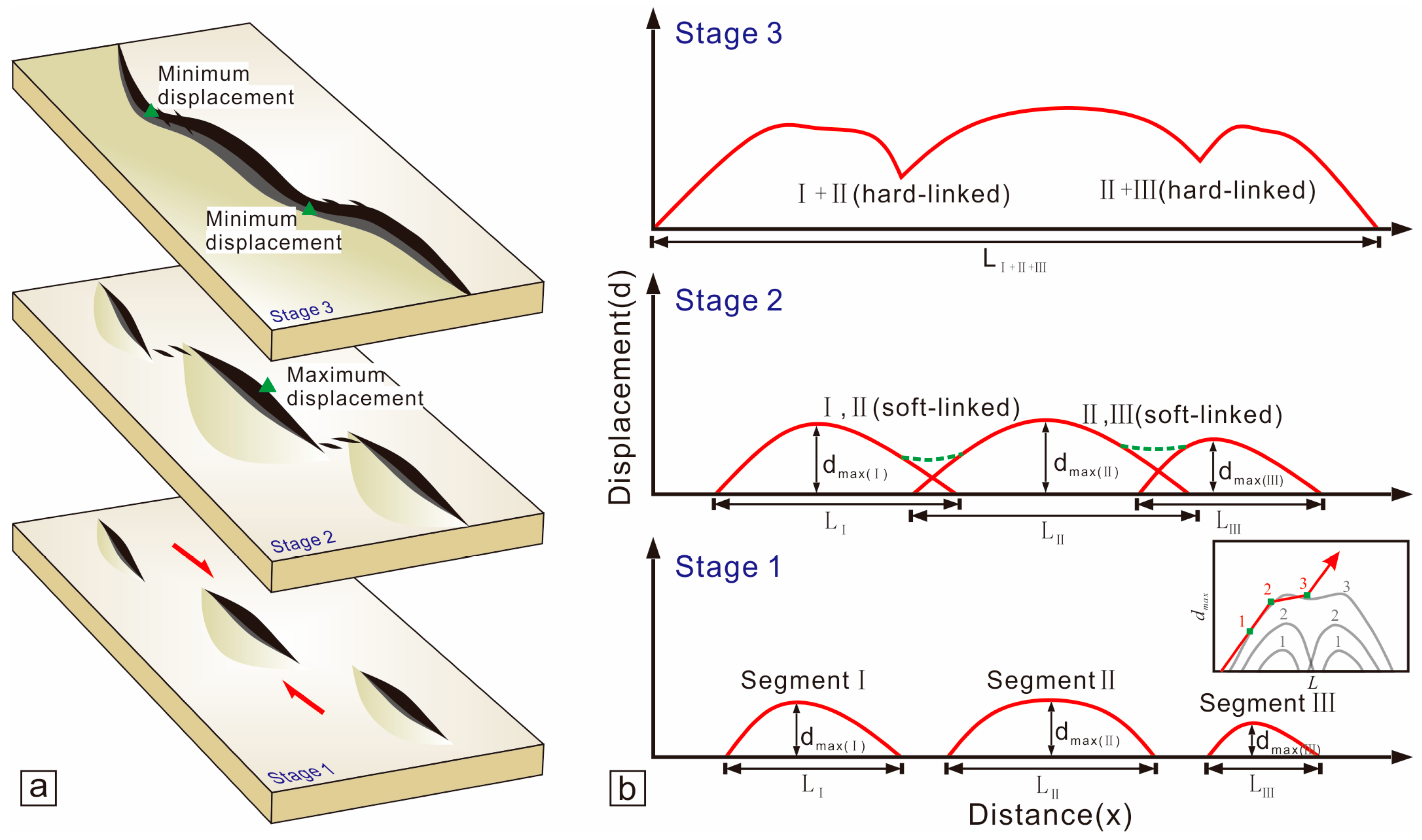

5.2. The Process and Pattern of Segmented Linkage of Strike–Slip Faults

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Along-strike throw of the strike–slip fault zone in the Daniudi Block exhibits a characteristic pattern, being highest centrally and decreasing toward both tips, with minor variation in the location of the maximum value. The development of fault overlay zones and secondary faults significantly enlarges the width of fault damage zone.

- (2)

- A positive power–law correlation exists between fault throw and damage zone width. This relationship allows the damage zone width of strike–slip faults in the study area to be roughly predicted from throw data, enabling mutual verification between these two parameters in future work.

- (3)

- The Xiaohaotu and Tuweihe Fault Zones are each formed through the linkage of three initially independent fault segments. The Xiaohaotu Fault is currently transitioning from segment isolation to soft linkage, whereas the Tuweihe Fault has progressed to a fully integrated strike–slip system through hard linkage.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torabi, A.; Berg, S.S. Scaling of fault attributes: A review. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2011, 28, 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, H.; Rotevatn, A. Fault linkage and relay structures in extensional settings—A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 154, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Sanderson, D.J. The relationship between displacement and length of faults: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2005, 68, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manighetti, I.; King, G.; Sammis, C.G. The role of off-fault damage in the evolution of normal faults. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2004, 217, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, C.W.; Vaagan, S.; Sanderson, D.J.; Gawthorpe, R.L. Spatial distribution of damage and strain within a normal fault relay at Kilve, U.K. J. Struct. Geol. 2019, 118, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, D.C.P. Propagation, interaction and linkage in normal fault systems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2002, 58, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.A.; Mansfield, C.; Trudgill, B. The growth of normal faults by segment linkage. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1996, 99, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen, K.J.; Shaw, J.H. Displacement profiles and displacement-length scaling relationships of thrust faults constrained by seismic-reflection data. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2010, 122, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Burbank, D.W.; Fisher, D.; Wallace, S.; Nobes, D. Thrust-fault growth and segment linkage in the active Ostler fault zone, New Zealand. J. Struct. Geol. 2005, 27, 1528–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraoka, H.; Kamata, H. Displacement distribution along minor fault traces. J. Struct. Geol. 1983, 5, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, D.C.P. Displacements and segment linkage in strike-slip fault zones. J. Struct. Geol. 1991, 13, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.L.D.; Bezerra, F.H.R.; Branco, R.M.G.C. Geophysical evidence of crustal-heterogeneity control of fault growth in the Neocomian Iguatu basin, NE Brazil. J. South Am. Earth Ences 2008, 26, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiny, C.D.M.A.; De Castro, D.L.; Rego Bezerra, F.H.; Bertotti, G. Rift fault geometry and evolution in the Cretaceous Potiguar Basin (NE Brazil) based on fault growth models. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2016, 71, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, P.A.; Scholz, C.H. Physical explanation for the displacement-length relationship of faults using a post-yield fracture mechanics model. J. Struct. Geol. 1992, 14, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Andrews, J.R.; Sanderson, D.J. Damage zones around strike-slip fault systems and strike-slip fault evolution, Crackington Haven, southwest England. Geosci. J. 2000, 4, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.J.; Watterson, J. Distributions of cumulative displacement and seismic slip on a single normal fault surface. J. Struct. Geol. 1987, 9, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.J.; Watterson, J. Analysis of the relationship between displacements and dimensions of faults. J. Struct. Geol. 1988, 10, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlische, R.W.; Young, S.S.; Ackermann, R.V.; Gupta, A. Geometry and scaling relations of a population of very small rift-related normal faults. Geology 1996, 24, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, D.C.P.; Sanderson, D.J. Displacements, segment linkage and relay ramps in normal fault zones. J. Struct. Geol. 1991, 13, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.H.; Kim, Y.; Su, Z.; Yang, P.; Ma, D.B.; Zheng, D.M. Segment interaction and linkage evolution in a conjugate strike-slip fault system from the Tarim Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 112, 104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.A.; Trudgill, B.D.; Mansfield, C.S. Fault growth by segment linkage: An explanation for scatter in maximum displacement and trace length data from the Canyonlands Grabens of SE Utah. J. Struct. Geol. 1995, 17, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, J.S.; Evans, J.P.; Forster, C.B. Fault zone architecture and permeability structure. Geology 1996, 24, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibberley, C.A.J.; Shimamoto, T. Internal structure and permeability of major strike-slip fault zones: The Median Tectonic Line in Mie Prefecture, Southwest Japan. J. Struct. Geol. 2009, 25, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, D.R.; Rutter, E.H. Can the maintenance of overpressured fluids in large strike-slip fault zones explain their apparent weakness? Geology 2001, 29, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawling, G.C.; Goodwin, L.B.; Wilson, J.L. Internal architecture, permeability structure, and hydrologic significance of contrasting fault-zone types. Geology 2001, 29, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipe, R.J. Juxtaposition and seal diagrams to help analyze fault seals in hydrocarbon reservoirs. AAPG Bull. 1997, 81, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipe, R.J.; Jones, G.; Fisher, Q.J. Faulting, fault sealing and fluid flow in hydrocarbon reservoirs: An introduction. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 1998, 25, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.G.; Miao, P.S.; Chen, L.L.; Zhao, H.L.; Wang, C. U-Pb ages and Hf isotopes of detrital zircons from the Cretaceous succession in the southwestern Ordos Basin, Northern China: Implications for provenance and tectonic evolution. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2021, 219, 104896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.H.; Li, L.; Zhou, J.; Jia, H.C.; Sun, X.; Qu, X.Y.; Zhou, D.; Gong, T.; Ding, C. Mesozoic structural evolution of the Hangjinqi area in the northern Ordos Basin, North China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2015, 55, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.H.; Li, S.X.; Guo, Q.H.; Guo, W.; Zhou, X.P.; Liu, J.Y. Enrichment conditions and favorable area optimization of continental shale oil in Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2022, 43, 1702–1716. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.J.; Liu, L.F.; Wang, T.G.; Wu, K.J.; Dou, W.C.; Song, X.P.; Feng, C.Y.; Li, X.Z.; Ji, H.T.; Yang, Y.S.; et al. Characteristics and controlling factors of lacustrine tight oil reservoirs of the Triassic Yanchang Formation Chang 7 in the Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 82, 265–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Tao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, H.C.; Jiang, H.J.; Ma, L.B.; Wang, F.B. Evaluation of geochemical characteristics and source of natural gas in Lower Paleozoic, Daniudi area, Ordos Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2021, 43, 307–314. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.T.; Chen, H.D.; Ouyang, Z.J.; Jin, X.Q. Sequence lithofacies paleogeographic characteristics of Majiagou Formation in Ordos area. Geol. China 2012, 39, 623–633. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.F.; Deng, H.C.; He, J.H.; Lei, T.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Hu, X.F. Characteristics and genesis of fractures in Middle Ordovician Majiagou Formation, Daniudi Gas Field, Ordos Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2022, 44, 41–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Deng, H.C.; Lei, T.; Fu, M.Y.; He, J.H.; Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Lan, H.X. Control of different faults on supergene karst in the Majiagou Formation of Daniudi Gas Field, northeastern Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2023, 34, 431–444. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hale, D. Methods to compute fault images, extract fault surfaces, and estimate fault throws from 3D seismic images. Geophysics 2013, 78, O33–O43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wu, K.; Liu, Q.; Wang, D.; Guo, W.J.; Liu, Y.L.; Xu, G.H. Enhanced interpretation of strike-slip faults using hybrid attributes: Advanced insights into fault geometry and relationship with hydrocarbon accumulation in Jurassic formations of the Junggar Basin. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipton, Z.K.; Cowie, P.A. Damage zone and slip-surface evolution over μm to km scales in high-porosity Navajo sandstone, Utah. J. Struct. Geol. 2001, 23, 1825–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, D.C.P.; Nixon, C.W.; Rotevatn, A.; Sanderson, D.J.; Zuluaga, L.F. Interacting faults. J. Struct. Geol. 2017, 97, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Fuxiao, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.T.; Scarselli, N.; Li, S.Y.; Yu, Y.L.; Wu, G.H. Seismic analysis of fault damage zones in the northern Tarim Basin (NW China): Implications for growth of ultra-deep fractured reservoirs. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2023, 255, 105778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Neng, Y.; Han, J.; Huang, C.; Zhu, X.X.; Chen, P.; Li, Q.Q. Structural styles and linkage evolution in the middle segment of a strike-slip fault: A case from the Tarim Basin, NW China. J. Struct. Geol. 2022, 157, 104558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Deng, S.; Tang, L.; Cao, Z. Geometry, kinematics and displacement characteristics of strike-slip faults in the northern slope of Tazhong uplift in Tarim Basin: A study based on 3D seismic data. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 88, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Fan, T.; Holdsworth, R.E.; Gao, Z.; Wu, J.; Gao, S.; Wang, M.; Yuan, Y. The spatial characterization of stepovers along deeply buried strike-slip faults and their influence on reservoir distribution in the central Tarim Basin, NW China. J. Struct. Geol. 2023, 170, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Gao, Z.Q.; Fan, T.L.; Shang, Y.X.; Qi, L.X.; Yun, L. Structural characterization and hydrocarbon prediction for the SB5M strike-slip fault zone in the Shuntuo Low Uplift, Tarim Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 117, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, V.; Childs, C.; Madritsch, H.; Camanni, G. Layering and structural inheritance controls on fault zone structure in three dimensions: A case study from the northern Molasse Basin, Switzerland. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2020, 177, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.S.; Nieto-Samaniego, A.F.; Alaniz-Álvarez, S.A.; Velasquillo-Martínez, L.G. Effect of sampling and linkage on fault length and length–displacement relationship. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2006, 95, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Fan, T.; Gao, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.H.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, N.; Yuan, Y.X. New insights on the geometry and kinematics of the Shunbei 5 strike-slip fault in the central Tarim Basin, China. J. Struct. Geol. 2021, 150, 104400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemse, E.J.M.; Pollard, D.D.; Aydin, A. Three-dimensional analyses of slip distributions on normal fault arrays with consequences for fault scaling. J. Struct. Geol. 1996, 18, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.H.; Dawers, N.H.; Yu, J.Z.; Anders, M.H.; Cowie, P.A. Fault growth and fault scaling laws: Preliminary results. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1993, 98, 21951–21961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.J.; Watterson, J. Geometric and kinematic coherence and scale effects in normal fault systems. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1991, 56, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lv, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, H. Internal structure and sealing properties of the volcanic fault zones in Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin, China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2014, 41, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolnai, G. Continental Wrench-Tectonics and Hydrocarbon Habita: Tectonique Continentale en Cisaillementt; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, A.; Brown, J.L.; Welbon, A.I.; McCallum, J.E.; Brockbank, P.; Knott, S. Characteristics of fault zones in sandstones from NW England: Application to fault transmissibility. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1997, 124, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Edwards, P.; Ko, K.; Kim, Y.S. Definition and classification of fault damage zones: A review and a new methodological approach. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 152, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Sanderson, D.J. Structural similarity and variety at the tips in a wide range of strike–slip faults: A review. Terra Nova 2006, 18, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, H.M.; Brodsky, E.E. Collateral damage: Evolution with displacement of fracture distribution and secondary fault strands in fault damage zones. J. Geophys. Res. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, P.A.; Scholz, C.H. Displacement-length scaling relationship for faults: Data synthesis and discussion. J. Struct. Geol. 1992, 14, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.T.; Zeng, L.B.; Mao, Z.; Han, J.; Cao, D.S.; Lin, B. Differential deformation of a strike-slip fault in the Paleozoic carbonate reservoirs of the Tarim Basin, China. J. Struct. Geol. 2023, 173, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutareaud, S.; Wibberley, C.A.J.; Fabbri, O.; Shimamoto, T. Permeability structure and co-seismic thermal pressurization on fault branches: Insights from the Usukidani Fault, Japan. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2008, 299, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, A.; Simmenes, T.H.; Larsen, B.; Philipp, S.L. Effects of internal structure and local stresses on fracture propagation, deflection, and arrest in fault zones. J. Struct. Geol. 2010, 32, 1643–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, D.R.; Lewis, A.C.; Rutter, E.H. On the internal structure and mechanics of large strike-slip fault zones: Field observations of the Carboneras fault in southeastern Spain. Tectonophysics 2003, 367, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondriest, M. Structure and Mechanical Properties of Seismogenic Fault Zones in Carbonates. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Padova, Padua, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Micarelli, L.; Benedicto, A.; Wibberley, C.A.J. Structural evolution and permeability of normal fault zones in highly porous carbonate rocks. J. Struct. Geol. 2006, 28, 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, D.C.P.; Parfitt, E.A. Active relay ramps and normal fault propagation on Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii. J. Struct. Geol. 2002, 24, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.S.; Nieto-Samaniego, A.F.; Alaniz-Alvarez, S.A.; Velasquillo-Martínez, L.G.; Grajales-Nishimura, J.M.; García-Hernández, J.; Murillo-Muñetón, G. Changes in fault length distributions due to fault linkage. J. Geodyn. 2010, 49, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, P.A.; Walsh, J.J.; Watterson, J. Limitations of dimension and displacement data from single faults and the consequences for data analysis and interpretation. J. Struct. Geol. 1992, 14, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Yang, M. Relationship Between Fault Elements and the Structural Evolution of Strike–Slip Fault Zones: A Case Study from the Ordos Basin. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12821. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312821

Li J, Yang M. Relationship Between Fault Elements and the Structural Evolution of Strike–Slip Fault Zones: A Case Study from the Ordos Basin. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12821. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312821

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jingying, and Minghui Yang. 2025. "Relationship Between Fault Elements and the Structural Evolution of Strike–Slip Fault Zones: A Case Study from the Ordos Basin" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12821. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312821

APA StyleLi, J., & Yang, M. (2025). Relationship Between Fault Elements and the Structural Evolution of Strike–Slip Fault Zones: A Case Study from the Ordos Basin. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12821. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312821