1. Introduction

Phase change concrete (PCC) offers a transformative approach to enhancing building energy efficiency by leveraging the latent heat of encapsulated phase change materials (PCMs) for thermal regulation [

1,

2,

3]. Among various encapsulation techniques, shape-stabilized composites using expanded perlite (EP) have shown particular promise due to their high PCM adsorption capacity and good compatibility with cementitious matrices [

4,

5]. However, the widespread application of PCC is critically limited by a significant and well-documented drawback: the substantial deterioration of mechanical properties, especially compressive strength, upon PCM incorporation [

6,

7].

This strength loss, reported to be 20–50% at PCM volumes of 10–30%, is primarily attributed to the weak interfacial transition zone (ITZ) around PCM aggregates and their inherent low strength [

8,

9]. While mitigation strategies such as fiber reinforcement [

10] have been explored, their efficacy in high-PCM content systems (>30%)—where microstructural damage is most severe—remains inadequate. The utilization of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) presents a more fundamental approach to microstructural enhancement [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].Silica fume (SF) is known to densify the matrix and strengthen the ITZ through its ultra-fine particles and high pozzolanic reactivity [

17,

18,

19,

20], while fly ash (FA) improves long-term performance via its pozzolanic and micro-filler effects [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, achieving high PCM content in cementitious composites often comes at a substantial cost to mechanical strength, which has been a major practical limitation hindering their broader structural applications. While scanning electron microscopy (SEMs) like SF and FA are known to mitigate strength loss, their synergistic effects—specifically in high-volume PCM systems utilizing expanded perlite-based paraffin (PA) PCM—remain unexplored. This lack of understanding represents a critical knowledge gap in optimizing the overall performance of PCC.

Therefore, this study aims to systematically investigate the reinforcing effects of SF and FA in PCC, with the objective of developing a material that retains favorable mechanical performance while preserving its thermal energy storage capacity. The specific objectives include: (1) examining the influence of PCM content (ranging from 10% to 40% by volume) on compressive strength; (2) evaluating the effectiveness of combined SF and FA as reinforcing agents; (3) elucidating the underlying reinforcement mechanisms through microstructural analysis.

The innovation of this study lies in proposing a systematic approach to mitigate the degradation of mechanical properties in PCC with high PCM content—a challenge that has not been effectively addressed in prior research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of PCC

PCC consists of PCM and concrete, and the following is the process of PCM preparation:

The specimen was prepared through adsorption under a vacuum and ultrasonic environment to form the composite PCM(PA/EP-V).

Spray coating encapsulation was employed: PA/EP was poured into a filter bottle, and the mouth of the bottle was sealed with a paper towel. The encapsulant nozzle was directed at the bottle opening for uniform spraying, while a glass stirring rod was used to continuously stir the mixture of encapsulant and PA/EP within the bottle, ensuring complete coating of each particle. This process yielded the encapsulated PCM, which was then removed from the filter bottle using a glass stirring rod for use in the experiment.

The raw materials used for the preparation of PCM are shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 1.

The key experimental equipment includes the vacuum adsorption device for PA/EP composite materials, differential scanning calorimeter, scanning electron microscope and pressure testing machine. Their appearances and configurations are detailed in

Figure 2.

As shown in

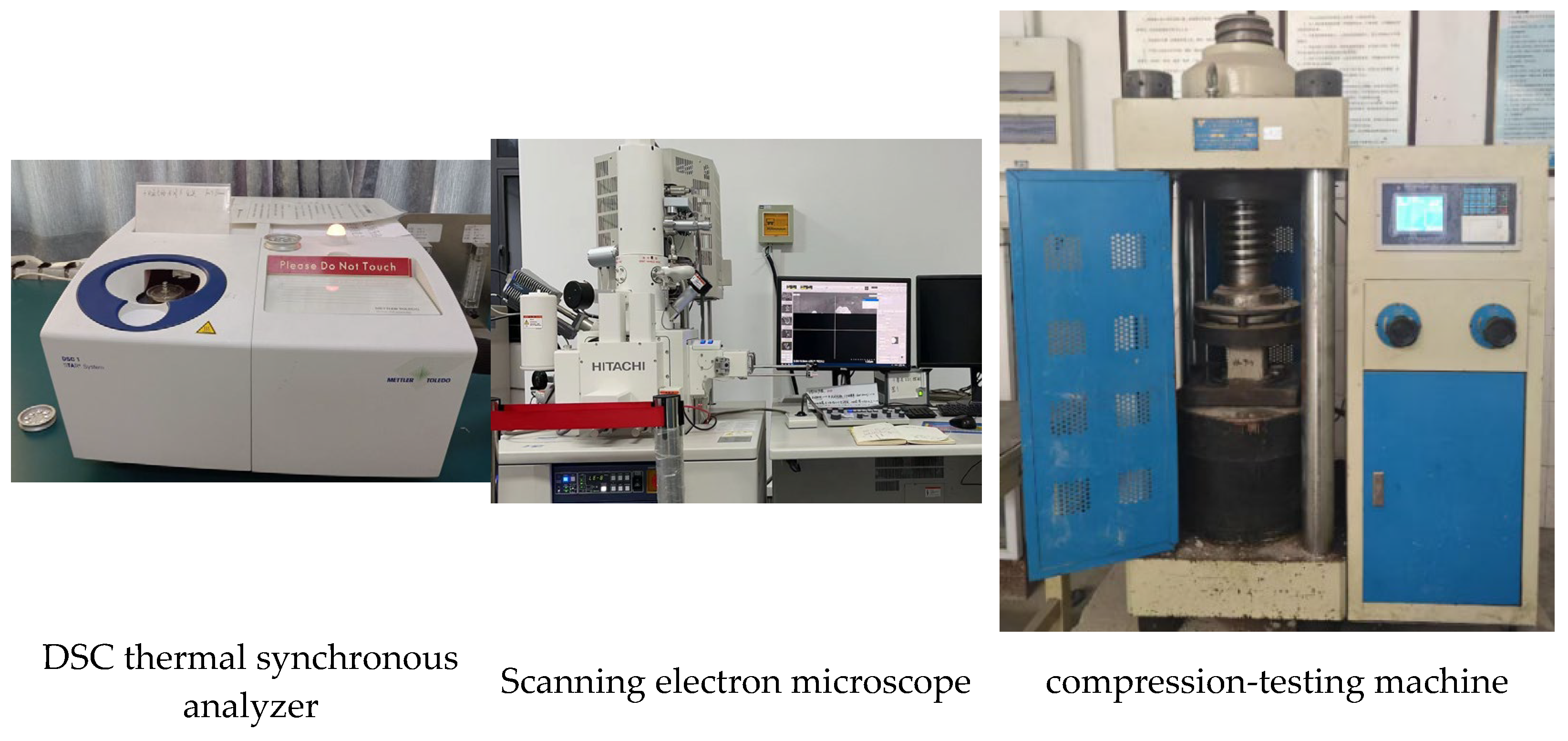

Figure 3, the DSC curves of the composite PCM of liquid PA and solid PA at different mass ratios are presented.

When the mass ratio of solid PA to liquid PA is 5:5, the heat storage capacity reaches its maximum value. The phase change temperature of the composite PA at this ratio is 31.21 °C, and the latent heat of phase change is −77.46 J/g. In this study, the composite PA with this optimal ratio is used as the experimental material.

The materials and apparatus used for PCC molding in this experiment are shown in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 3, the detailed mix proportions of unreinforced PCC are provided. This group served as the control and is hereafter referred to as Group C.

The reinforced PCC group, with the mix proportion specified in

Table 4, served as the enhancement group and is hereafter referred to as Group R.

The concrete test block molding work was carried out according to the mix ratios shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The water-to-binder ratio in both Group C and Group R is 0.38. The key difference is that Group R employs an equal-mass substitution approach, replacing a portion of cement with SF and FA as reinforcing materials.

A total of eight groups (four for conventional and four for reinforced concrete) were prepared, with three specimens per group. The compressive strength for each group was taken as the average of the three replicates.

All specimens were cured for 28 days under controlled environmental conditions, with temperature maintained at 20 ± 2 °C and relative humidity kept above 95%. Compressive strength was used as the primary evaluation metric. The cured concrete specimens, including the PCC specimens, are presented in

Figure 4.

2.2. Experimental Design

Ordinary PCC group (hereinafter referred to as Group C): In this experiment, PCM with a particle size of 1–2 mm was utilized to replace sand in the concrete according to the volume ratio.

Reinforced PCC group (hereinafter referred to as Group R): In this experiment, PCM with a particle size of 1–2 mm was utilized to replace sand in the concrete according to the volume ratio. The enhanced method incorporates 8% SF and 10% FA by mass of cementitious materials, while maintaining a constant water-to-binder ratio of 0.38, consistent with that of the conventional concrete mixture.

The mix proportions were designed using the absolute volume method. The substitution ratio of PCM for sand in concrete is determined based on density equivalence. Given that the density of sand is 3.94 times higher than that of PCM, replacing 3.94 kg of sand with 1 kg of PCM ensures that the overall volume of the concrete mixture remains constant. The superplasticizer dosage was adjusted for each mixture to maintain consistent workability across different PCM contents.

The experimental setup consisted of two groups, each containing four distinct PCM replacement rates, with detailed grouping information presented in

Table 5.

3. Results

3.1. Test Results

Table 6 presents the compressive strength values, strength standard deviations, and mean compressive strength for each specimen group. The small standard deviations (0.17–0.78 Mpa) demonstrate high consistency and repeatability of the measurement results.

The cured cubic specimens were moistened with water to maintain surface saturation and subjected to compressive strength testing at a room temperature of 20 °C. Each specimen was carefully positioned at the center of the lower platen of the testing machine, and the loading rate was set to 0.5 Mpa/s. Upon contact between the specimen and the upper platen, a constant loading rate was applied until failure occurred, and the peak compressive strength was recorded. The processed experimental data are presented in

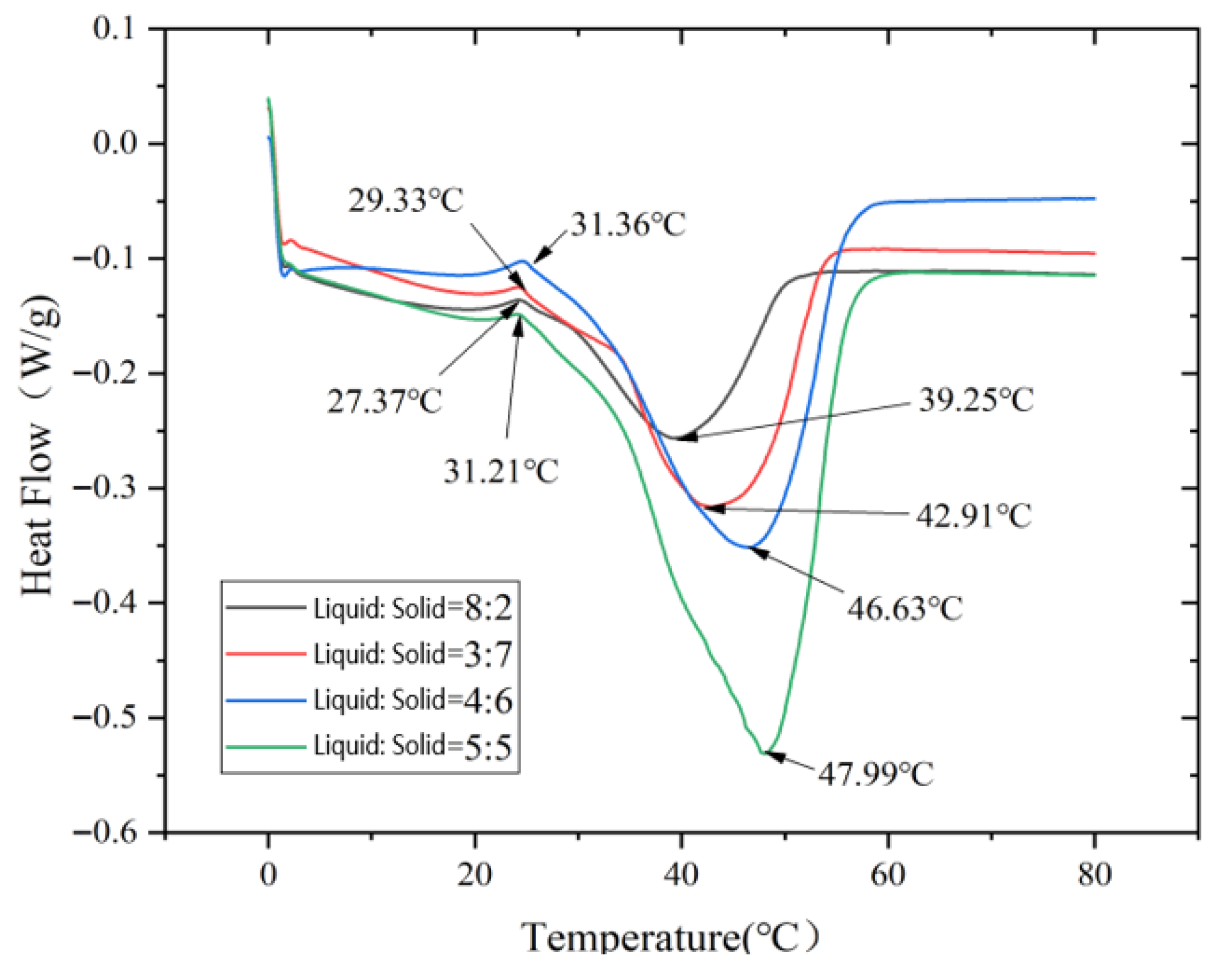

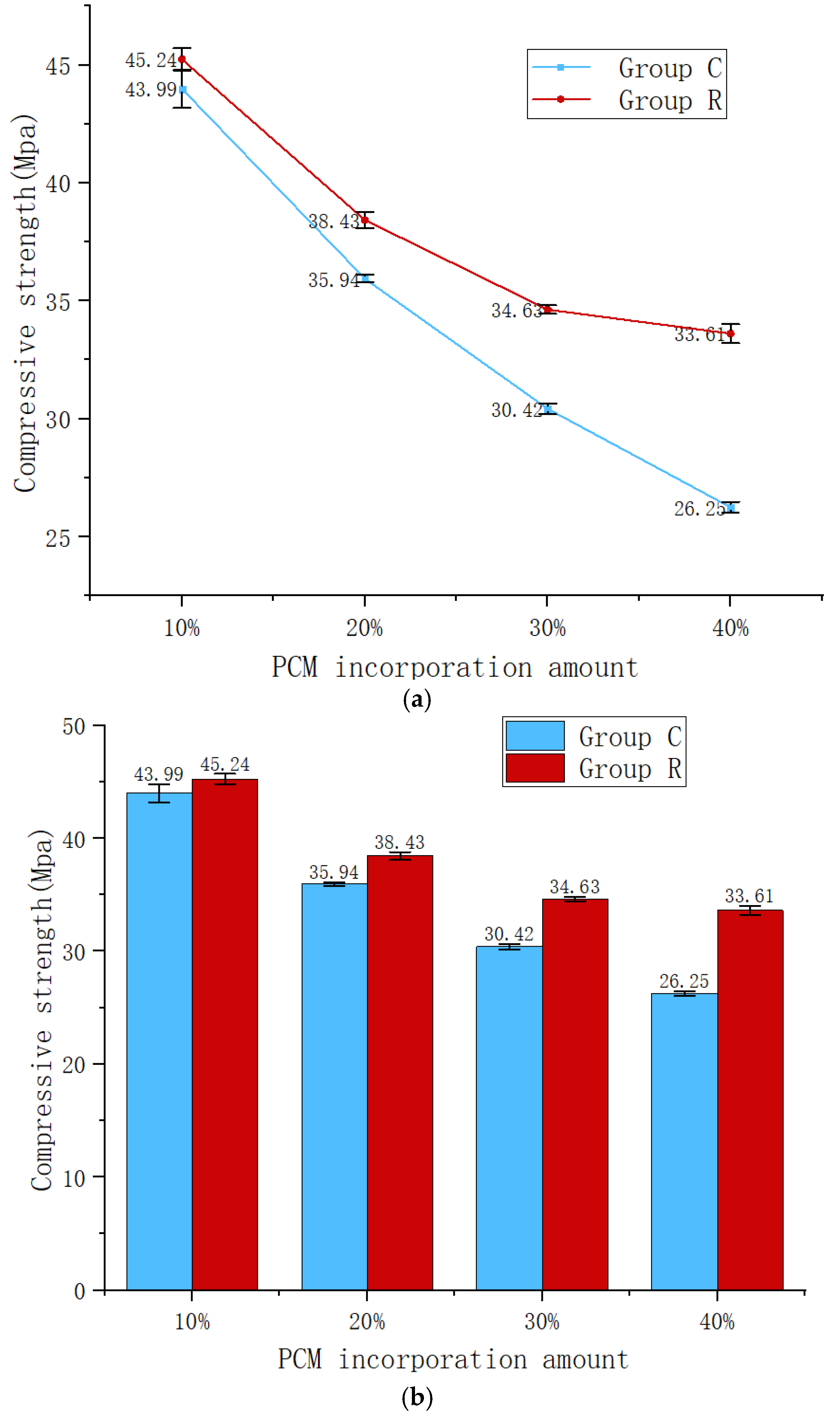

Figure 5. The values at the nodes denote the mean compressive strength, while the black error bars represent the corresponding standard deviation.

In

Figure 5a, the compressive strength of the reinforced group R consistently surpassed that of the control group C. As the PCM dosage increased, the compressive strength of group C exhibited a nearly linear decreasing trend, with a more pronounced rate of strength reduction. In contrast, for group R, the decline in strength was steeper at lower PCM dosages but gradually leveled off as the dosage increased. With increasing PCM content, the reinforcing effect on the compressive strength of PCC became increasingly evident.

In

Figure 5b, it is evident that when the PCM dosage exceeded 30%, the enhancement effect became significant: the compressive strength of concrete in group R decreased more slowly, and the strengths at 30% and 40% PCM dosage were similar.

3.2. Two-Factors Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

Data description for two-way ANOVA: Factor A (Group) included two levels (Group C, Group R), and Factor B (PCM incorporation level) included four levels (10%, 20%, 30%, 40%). A fully crossed factorial design was employed, with each treatment combination replicated three times, resulting in a total sample size of 2 × 4 × 3 = 24 compressive strength measurements.

A normality test was performed on the compressive strength, with the null hypothesis stating that the data follow a normal distribution. Given that the sample size was less than 50, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied. The results indicated that the test statistic for compressive strength was not statistically significant (

p > 0.05), supporting the acceptance of the null hypothesis—namely, that the compressive strength data exhibit characteristics of a normal distribution. Detailed statistical results are presented in

Table 7.

Homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene’s test to evaluate the dispersion of data across groups and determine whether significant differences existed. As shown in

Table 8, the sample variances for compressive strength across different groups were not statistically significant (

p > 0.05), indicating consistent variability among groups and no evidence of heterogeneity. Therefore, the assumption of homogeneity of variance—required for analysis of variance (ANOVA)—is satisfied, supporting the appropriateness of conducting subsequent ANOVA.

As shown in

Table 9, the

p-values for all factors are significantly less than 0.05, indicating that the application of PCC reinforcement, the dosage of PCM incorporation, and their interaction exert statistically significant effects on compressive strength. Specifically, reinforcement exerts a positive influence on compressive strength, whereas higher dosages of PCM are associated with reduced compressive strength—a finding consistent with established principles of material mechanical behavior. Notably, the magnitude of the reinforcement effect varies significantly across different levels of PCM dosage, providing further evidence of a significant interaction between these two factors.

Section 3.3 provides a detailed discussion of the specific patterns and underlying mechanisms of this interaction.

3.3. Analysis of Test Results

Effect of PCM doping on compressive strength: As shown in

Table 10 and

Table 11, the rate of decrease in compressive strength is defined as the ratio of the strength reduction at each PCM dosage level relative to the 10% PCM dosage group. Alternatively, the rate of strength decrease can also be calculated based on the reduction relative to the immediately preceding dosage level.

As shown in

Table 10, the cubic compressive strength of PCC in Group C decreases with the increase in the PCM dosage, and the extent of the compressive strength decline gradually increases.

As shown in

Table 11, with increasing PCM content, the percentage reduction in cube compressive strength and the rate of strength decline for PCC in Group R are significantly lower than those in Group C. When the PCM dosage exceeds 30%, the compressive strength of phase change enhanced concrete shows no significant difference from the previous dosage level, indicating that the reinforcing effect becomes markedly enhanced beyond this threshold.

Influence of reinforcement on compressive strength: The reinforcement growth rate listed in

Table 12 is defined as the ratio of the compressive strength of Group R to that of Group C at the same PCM dosage. This comparison enables a direct analysis of the strength enhancement pattern between the reinforced and control groups under identical PCM admixture levels.

It can be observed that the reinforcement growth rate gradually increases with increasing PCM content, indicating that the supplementary cementitious materials SF and FA) exert a progressively more pronounced effect on improving the compressive strength of PCC. As clearly shown in the compressive strength trend graph, the strength of Group R concrete exhibits a slower rate of attenuation with increasing PCM content, further illustrating this reinforcing effect.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of EP and PCM

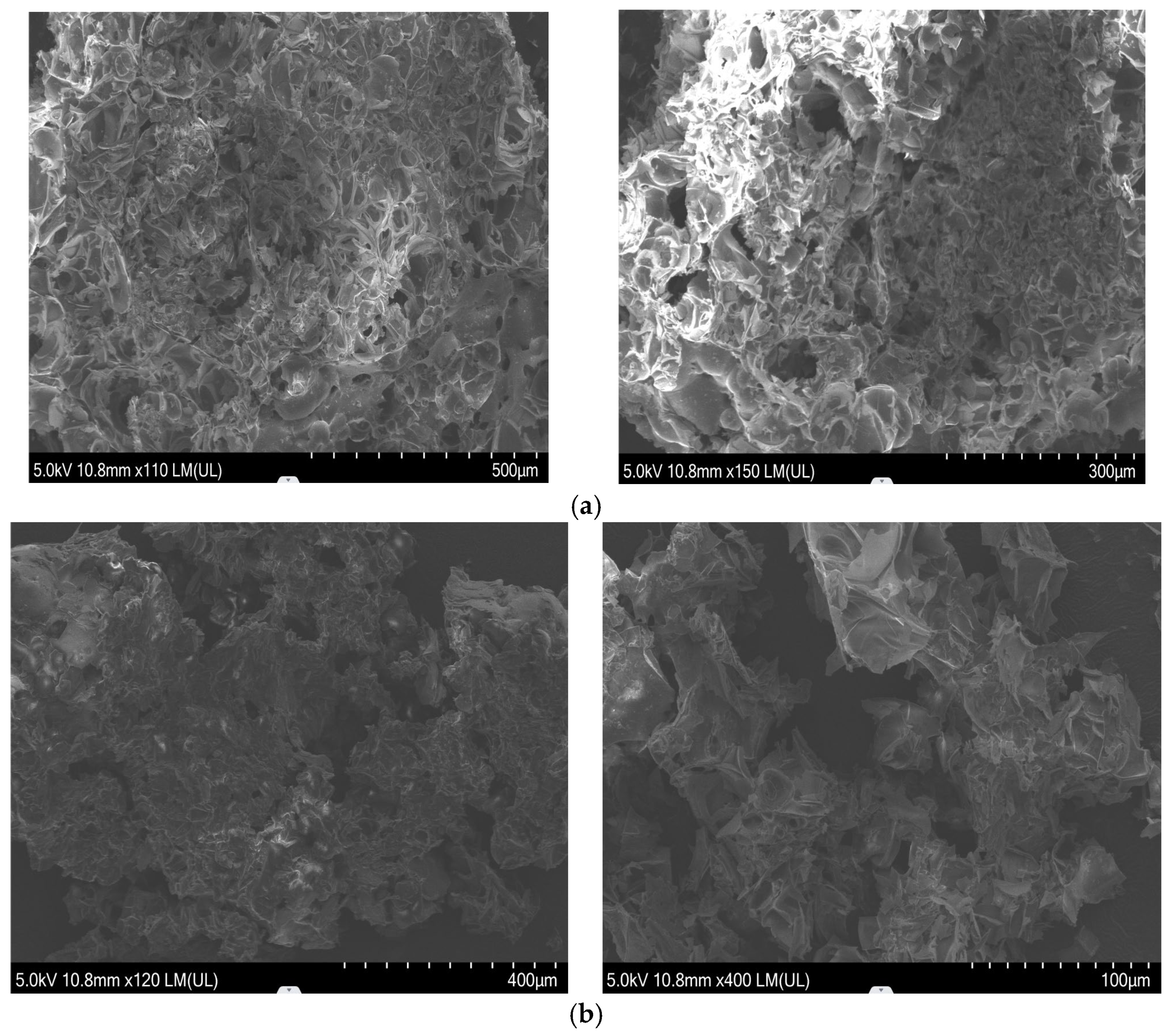

As shown in

Figure 6a, the microscopic morphology of expanded perlite observed via scanning electron microscopy reveals a highly porous internal structure. This inherent porosity enables the theoretical adsorption of PA within the material. However, because phase change PA melts at approximately 30 °C and the pores of expanded perlite are open and interconnected with the external environment, a significant leakage risk arises. Therefore, following PA infiltration into the expanded perlite, thorough stirring is necessary to ensure uniform dispersion of the encapsulant within the PA/EP matrix and to achieve complete encapsulation. As illustrated in

Figure 6b, the resulting encapsulated PCM exhibits markedly reduced porosity, confirming effective immobilization of PA within the internal pores of the shaped support material.

Although the porosity of the prepared PCM is significantly lower than that of expanded perlite, due to the inherently low density of expanded perlite and the low compressive strength of both expanded perlite and PA, a high proportion of PCM incorporation is required to achieve excellent thermal performance in PCC. However, such high loading inevitably compromises mechanical properties. Therefore, effectively filling the internal pores of PCC to enhance the mechanical properties of conventional specimens and minimize property degradation has become a central challenge in this study.

4.2. Analysis of the Reinforcement Effect of Concrete Strengthening

SF particles that remain chemically inert occupy the micro-pores within the cement matrix, thereby promoting material densification, effectively reducing total porosity, suppressing the formation of harmful macropores, and consequently enhancing the mechanical properties and resistance to deterioration of mortar and concrete at the macroscopic level. The active components in FA participate in secondary hydration reactions with Ca(OH)2, forming C-S-H gel and reducing the Ca(OH)2 content. These hydration products exhibit a dense microstructure, as typically observed in such systems. When substantial amounts of FA and slag undergo hydration, they generate agglomerated and spherical particles, with calcium zeolite being among the resulting phases. These reaction products contribute to more effective pore-filling, thereby improving the strength of the cementitious system.

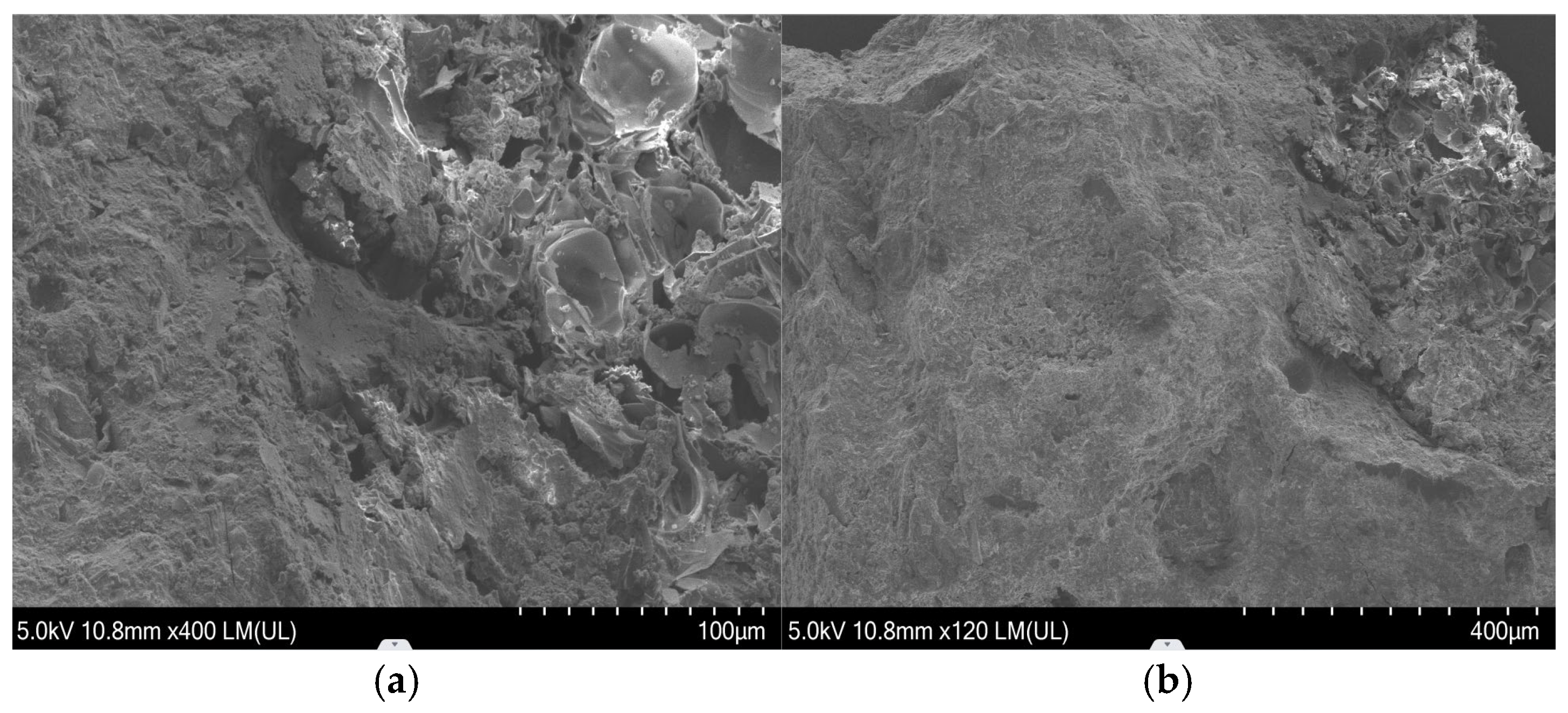

As shown in

Figure 7a, the SEM image of the PCC in Group C reveals numerous pores, including residual voids unfilled with PA and inherent pores within the concrete matrix. In contrast,

Figure 7b demonstrates that the reinforced PCC in Group R exhibits a denser microstructure and a more complete and advanced hydration process.

Phase-change mortar and phase-change concrete strength reduction is due to the following reasons: expanded perlite (EP) as a setting material is made of perlite ore under high-temperature conditions volume expansion of about 20 times, with a loose and porous structure, and has a lightweight, friable and other characteristics. Expanded perlite has a lower bearing capacity than cement paste, leading to stress inhomogeneity within the mortar’s internal structure, expanded perlite in the cement matrix to form a porous structure, the interface between the aggregate and the cement stone within the matrix in the transition zone of the presence of more harmful large pores.

As the dosage of PCMs increases, the enhancement rate gradually rises. This is mainly attributed to the greater number of pores in PCC with high PCM content, which provides more reaction space for SF and FA, allowing their pozzolanic activity and micro-aggregate filling effect to be more fully exerted. The synergy between SF and FA not only strengthens more PCM interfacial transition zones but also effectively fills internal pores. However, under lower PCM dosage, the limited number of pores restricts the action range of SF and FA, resulting in relatively insignificant enhancement effects. Therefore, it can be inferred that under high PCM content conditions, the mechanical performance improvement of the enhanced group is more significant, benefiting from the more efficient hydration reaction and densification of SF and FA in the more abundant pore structure.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, different dosage of PCM is used to replace sand in concrete to study the effect of PCM dosage on compressive strength; by adding SF and FA to concrete to study the effect of reinforcing materials on the compressive strength law of phase-change concrete, analyzed the failure mechanism, SF and FA reinforcing mechanism, the specific conclusions are as follows:

With the gradual increase in PCMs, the effectiveness of the mechanical enhancement shows an increasing trend with higher PCM content. Tests show that when the replacement rate of PCM is lower than 30%, the PCC can meet the 30 Mpa compressive strength standard without reinforcement; when the dosage is more than 40%, it needs to be reinforced to achieve the same strength requirements. At 40% PCM dosage, compressive strength (33.6 Mpa) decreased by only 2.9% compared to 30% group (34.6 Mpa), indicating stabilized reinforcement efficiency. In actual projects, through enhanced processing, a high proportion substitution of PCM for sand was achieved. The higher the PCM content, the better the thermal performance. The reinforcing PCC, while ensuring the PCM dosage, maximally restrains the degradation of mechanical properties. Compared to conventional concrete, it significantly mitigates excessive loss in mechanical performance, thereby ensuring structural reliability without compromising thermal functionality.

The higher PCM content in PCC significantly enhances the reinforcing effect of SF and FA, attributed to the provision of more pores which offer sufficient reaction space for SF and FA, enabling their pozzolanic activity and micro-aggregate filling effect to be fully exerted. This effectively improves the ITZ and achieves a denser microstructure.

The research results demonstrate that through rational optimization of the cementitious material system, combined with experimental results and microstructural analysis, enhanced PCC can not only effectively maintain the intended PCM dosage but also exhibit excellent mechanical properties, thereby providing a feasible technical pathway for its large-scale application in practical engineering.

Limitations of the study: The cost implications associated with large-scale substitution of up to 40% of sand with PCM require further investigation to support practical engineering applications. This study primarily focused on compressive strength as a key mechanical property. Future research should systematically evaluate additional mechanical properties, durability, freeze–thaw resistance, thermal performance at the concrete component level, and morphological parameters of EP particles—such as particle size distribution and roundness—within enhanced phase change concrete, in order to comprehensively assess the practical applicability of the developed PCM-enhanced concrete.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. (Yanwei Li), Y.L. (Yunfeng Li) and Y.D.; methodology, Y.L. (Yunfeng Li) and Y.L. (Yanwei Li); software, Y.L. (Yanwei Li) and Y.D.; validation, Y.L. (Yunfeng Li) and Y.L. (Yanwei Li); formal analysis, Y.L. (Yanwei Li); investigation, Y.D.; resources, Y.L. (Yunfeng Li); data curation, Y.L. (Yanwei Li); writing—original draft preparation, Y.D., Y.L. (Yunfeng Li) and Y.L. (Yanwei Li); writing—review and editing, Y.L. (Yanwei Li) and Y.L. (Yunfeng Li); visualization, Y.D. and Y.L. (Yanwei Li); supervision, Y.L. (Yunfeng Li); project administration, Y.L. (Yunfeng Li) and Y.L. (Yanwei Li); funding acquisition, Y.L. (Yanwei Li) and Y.L. (Yunfeng Li). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gaitero, J.J.; Prabhu, A.; Hochstein, D.; Mohammadi-Firouz, R.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; Bendouma, M.; Snoeck, D.; Ramón-Álvarez, I.; Sánchez-Delgado, S.; Torres-Carrasco, M.; et al. Reviewing Experimental Studies on Sensible Thermal Energy Storage in Cementitious Composites: Report of the RILEM TC 299-TES. Mater. Struct. 2024, 57, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotun, S.S.; Gooroochurn, M.; Lollchund, R.M. Determining the Most Efficient Phase Change Materials Configuration for Enhancing the Thermal and Energy Performance of Concrete Building Envelopes in a Tropical Region. Energy Build. 2025, 331, 115380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Al Majali, H.; Bendea, C.; Bungau, C.C.; Bungau, T. Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Buildings through PCM Integration: A Study across Different Climatic Regions. Buildings 2024, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa-Stratulat, S.-M.; Taranu, G.; Toma, A.-M.; Olteanu, I.; Pastia, C.; Bunea, G.; Toma, I.-O. Effect of Expanded Perlite Aggregates and Temperature on the Strength and Dynamic Elastic Properties of Cement Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapeluszna, E.; Kotwica, Ł.; Pichór, W.; Nocuń-Wczelik, W. Cement-Based Composites with Waste Expanded Perlite—Structure, Mechanical Properties and Durability in Chloride and Sulphate Environments. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2020, 24, e00160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somani, P.; Gaur, A. Thermo-Mechanical Analysis of Microencapsulated Phase Change Material Incorporated in Concrete Pavement. Mater. Lett. 2024, 366, 136520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lai, Y.; Pei, W.; Qin, Z.; Li, H. Study on the Physical Mechanical Properties and Freeze-Thaw Resistance of Artificial Phase Change Aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 329, 127225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.E.; Trageser, J.E.; Jones, R.E.; Rimsza, J.M. Sensitivity of the Strength and Toughness of Concrete to the Properties of the Interfacial Transition Zone. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 336, 126875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraneni, P.; Burris, L.; Shearer, C.R.; Hooton, R.D. ASTM C618 Fly Ash Specification: Comparison with Other Specifications, Shortcomings, and Solutions. ACI Mater. J. 2021, 118, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, C.; Song, F.; He, B.; Li, W.; Jiang, Z. Autogenous Self-Healing of Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced Concrete with Varying Silica Fume Dosages: Secondary Hydration and Structural Regeneration. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 137, 104905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sante, M.; Khan, M.K.; Calò, L.; Fratalocchi, E.; Mazzieri, F. The Combined Use of Fly Ash and Lime to Stabilize a Clayey Soil: A Sustainable and Promising Approach. Geosciences 2025, 15, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Aggarwal, P. Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Concrete: A Comprehensive Review. Silicon 2022, 14, 2453–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.S.; Hasan, Z.A.; Jaaz, H.A.G.; Abed, M.K.; Falah, M.W.; Hashim, T.M. Mechanical Properties of Sustainable Reactive Powder Concrete Made with Low Cement Content and High Amount of Fly Ash and Silica Fume. J. Mech. Behav. Mater. 2022, 31, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantilli, A.P.; Nishiwaki, T. Ecological and Mechanical Performances of Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced Cementitious Composite Containing Fly Ash. ACI Mater. J. 2023, 120, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, D.M.; Effting, C.; Schackow, A.; Gomes, I.R.; Cifuentes, G.A.; Ganasini, D. Thermomechanical Behavior of High-Volume Fly Ash Concretes. ACI Mater. J. 2020, 117, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azare, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.H.W.; Alshalif, A.F.; Jaya, R.P.; Nindyawati, N. Bibliometric Analysis of High-Strength Self-Compacting Concrete Performance Containing Silica Fume and Fly Ash: Review. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2025, 49, 3255–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, A.; Bissonnette, B.; Duchesne, J.; Fournier, B. Shrinkage of Alkali-Activated Combined Slag and Fly Ash Concrete Cured at Ambient Temperature. ACI Mater. J. 2022, 119, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadkar, A.; Subramaniam, K.V.L. Self-Leveling Geopolymer Concrete Using Alkali-Activated Fly Ash. ACI Mater. J. 2021, 118, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y.; Kang, S.-H.; Kim, M.O.; Moon, J. Acceleration of Cement Hydration from Supplementary Cementitious Materials: Performance Comparison between Silica Fume and Hydrophobic Silica. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 112, 103688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Fan, W.; Nong, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, J. Combined Effects of Nano-Silica and Silica Fume on the Mechanical Behavior of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2021, 10, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.C.S.; Arunakanthi, E. Microstructural and Mechanical Evaluation of HVFAC Incorporating Recycled Plastic Flakes and Pozzolanic Additives for Environmental Sustainability. Environ. Chall. 2025, 20, 101196. [Google Scholar]

- Lekshmi, S.; Sudhakumar, J. Performance of Fly Ash Geopolymer Mortar Containing Clay Blends. ACI Mater. J. 2022, 119, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyelowe, K.C.; Kontoni, D.-P.N.; Ebid, A.M.; Dabbaghi, F.; Soleymani, A.; Jahangir, H.; Nehdi, M.L. Multi-Objective Optimization of Sustainable Concrete Containing Fly Ash Based on Environmental and Mechanical Considerations. Buildings 2022, 12, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankaja, B.S.; Ranjita, N.H.; Ramesh, H.N.; Kho, J.C.; Raghunandan, M.E. Suitability of Fly Ash–Cement Kiln Dust Columns for Stabilizing Expansive (Black Cotton) Soils. Arch. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2025, 3, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, S.; Duan, P.; Yang, S. Influence of Particle Morphology of Ground Fly Ash on the Fluidity and Strength of Cement Paste. Materials 2021, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvallet, T.Y.; Paraschiv, M.; Oberlink, A.E.; Jewell, R.B.; Robl, T.L. Study of Alite–Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Produced from a High-Alumina Fly Ash. ACI Mater. J. 2022, 119, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kuźnia, M. A Review of Coal Fly Ash Utilization: Environmental, Energy, and Material Assessment. Energies 2025, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).