1. Introduction

Compared with switched reluctance motor (SRM), permanent magnet-assisted switched reluctance motor (PMa-SRM) combine the advantages of permanent magnet synchronous motors and switched reluctance motors, making full use of the reluctance torque and the permanent magnet torque [

1,

2,

3]. They feature not only high energy efficiency and higher power density but also have the advantages of a wide speed regulation range and high cost-effectiveness. The assembly process and magnetization sequence of permanent magnets define the electromagnetic nature of PMa-SRM. These factors not only determine the distribution of the air-gap magnetic field, the improvement of torque density, and the torque ripple characteristics but also profoundly influence the parameter tuning of control strategies and the flux-weakening speed expansion capability [

4,

5]. However, owing to the double salient structure and the mode of switching phase winding, the magnetic circuit, which makes a larger torque ripple, is nonlinear, resulting in obvious vibration and noise. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the actual torque traces the reference torque in the case of high speeds and heavy loads in industries and electric vehicles. Therefore, suppressing the torque ripple of reluctance motors across a wide speed range has become a research hotspot [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Nowadays, many control methods have been presented to suppress torque ripple, such as direct torque control (DTC), direct instantaneous torque control (DITC), TSF, and model predictive torque control (MPTC). The cutting-edge research on dynamically regulated polarization selection [

13], zone-specific assembly governed by many-body interactions [

14], and adaptive propulsion across a broad frequency range [

15] in colloidal systems has provided critical insights into and validation for the implementation of adaptive control strategies in complex systems. In [

16], a model predictive torque control strategy based on optimized voltage vectors is proposed. This control strategy divides the motor operation sectors according to the torque characteristics, thereby reducing the number of candidate voltage vectors, effectively reducing the computational burden of predictive control, and it can effectively reduce torque ripple and enhance dynamic response capability. In [

17], a high torque–ampere ratio is acquired in the two-phase exchange (TpE) region by an optimized DTC, and reference torque is distributed rationally. A rotor pole angle is divided into six regions, and a different voltage state is selected in each region in an improved DITC strategy [

18]. The inductance variation rate of the outcoming phase quickly declines in the TpE region, resulting in small torque, so torque error compensation is applied to the outcoming phase to reduce torque ripple [

19]. An offline TSF based on the flux characteristic can suppress torque ripple with minimum copper loss [

20]. In [

21], an optimal TSF strategy is introduced where linear active disturbance rejection control is adopted, and a modified coyote optimization algorithm is presented to automatically adjust the turn-on and turn-off angles. To reduce the current error at high speeds, the reference current of the input and output phases is compensated in the TpE regions, respectively [

22,

23]. In [

24], an optimal TSF is devised based on the electromagnetic characteristics of the motor, which is controlled by the cerebellar model articulation controller (CMAC) to suppress the electromagnetic torque of the outcoming phase and increase the electromagnetic torque of the incoming phase. Both the turn-on and turn-off angles are adjusted in the next electrical cycle by sampling the current in online TSF strategy [

25]. In [

26,

27], the TpE is segmented into two regions, and the corresponding hysteresis control strategy is designed based on the inductance characteristics.

Several intelligent algorithms have been integrated with SRM control methods, including sliding mode control, neural networks, and fuzzy control. In [

28], a sliding mode control strategy is employed to regulate the phase current that can remedy the torque ripple in the TpE region online. In [

29], the three-phase currents are accurately reconstructed and controlled using a single-phase current measurement. In [

30], the phase current of the incoming and outgoing phase in the TpE region is dominated by a nonlinear regulatory factor to suppress torque ripple. In [

31], the parameters are optimized by using a genetic algorithm, and the TSF is more consistent with the torque characteristics in the TpE. In [

32,

33], by estimating the demagnetization ability of the online phase, the mechanical angle period is divided into six sectors. As a consequence of this division, the negative torque is avoided and the optimizable region is determined.

But there exists larger torque ripple in conventional TSF, especially under high speeds or heavy loads. A TSF control method with an adaptive conduction angle in three regions is presented in this paper. The TpE is subdivided into two regions according to the inductance characteristics, and different control methods are employed in different regions. The turn-on angle is regulated at different speeds and loads, and the simulation and prototype experiment are carried out to prove performance of suppressing torque ripple. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows: (1) A novel partitioned torque sharing function method is proposed. (2) An adaptive adjustment of the turn-on angle is realized.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 describes the mathematical model about the PMa-SRM;

Section 3 and

Section 4 describe the theoretical principles of a traditional TSF and a novel TSF control method;

Section 5 describes the turn-on angle optimization algorithm;

Section 6 and

Section 7 present the simulation and experiment results to verify the accuracy.

2. Mathematical Model of PMa-SRM

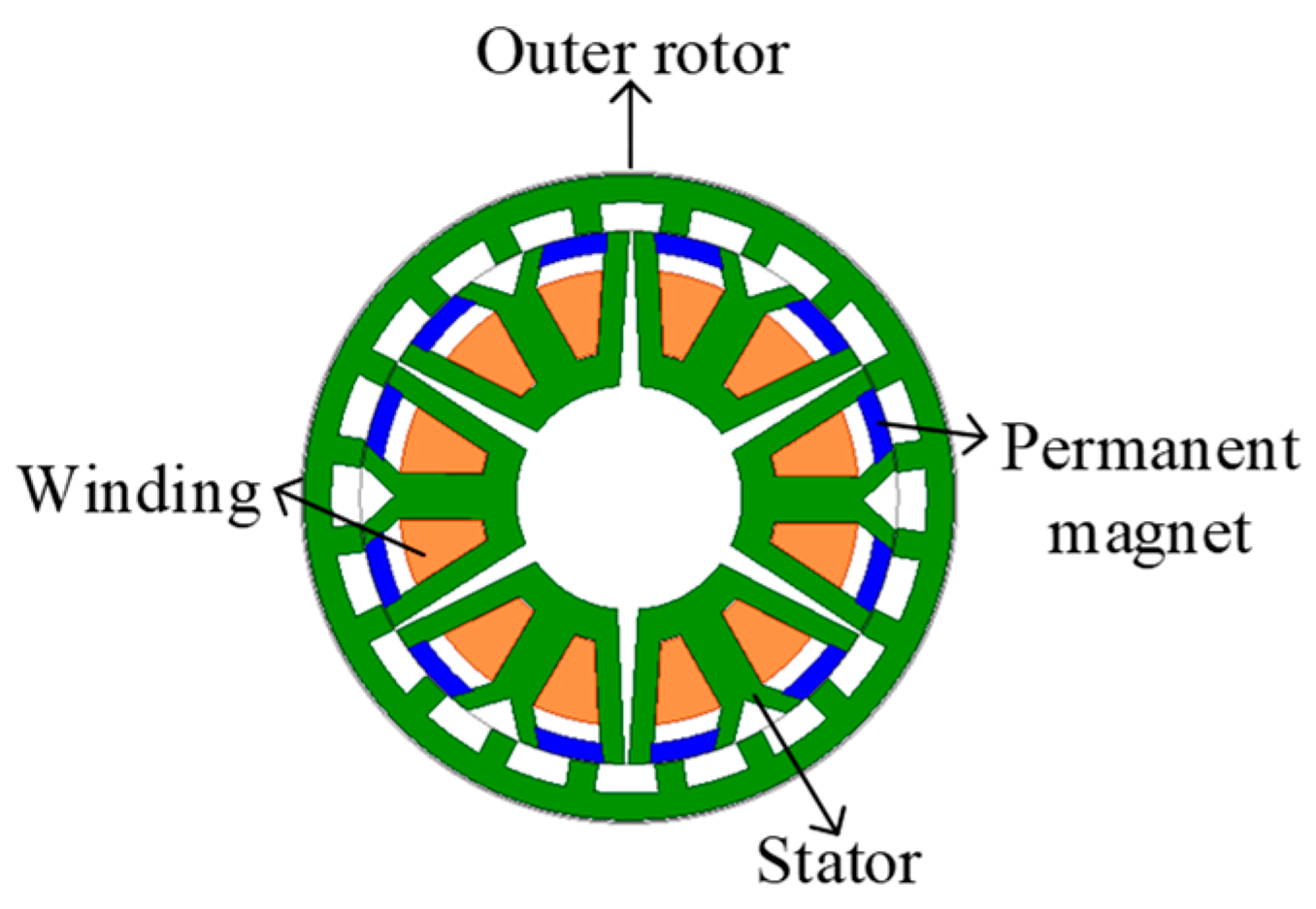

The structural model of the PMa-SRM presented in

Figure 1 is composed of an outer rotor and an inner stator. The stator is made up of six segmented modules, each of which is W-shaped. There is only one phase winding per module. Both opposing coils are connected in series to compose one phase, and there are three phase windings.

2.1. Electromagnetic Characteristic

Both the stator and rotor of PMa-SRM are salient pole structures. The motor’s magnetic circuit is nonlinear, because the flux linkage is switched among the phase windings when the rotor rotates. The tooth tip is highly saturated when the rear edge of the stator tooth meets the leading edge of the rotor tooth. The accuracy of the established linear model is limited due to nonlinear factors, including the skin effect in stator windings and the hysteresis of permanent magnets. The position and current accuracy of the model is poor, making it difficult to implement effective control strategies.

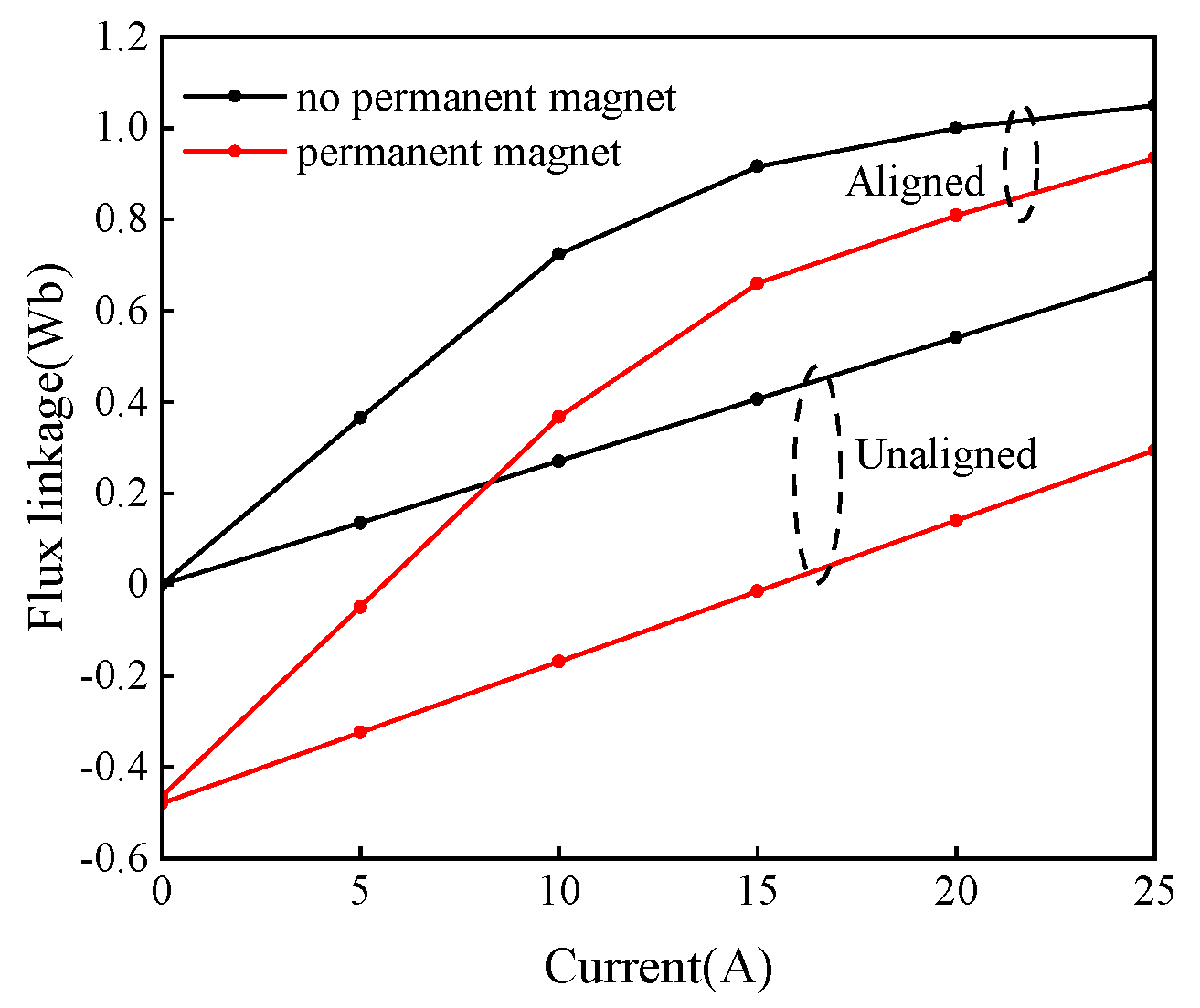

Based on the electromechanical energy transmission relationship, the output electromagnetic torque of the PMa-SRM is the graphic area enclosed by the two curves in

Figure 2: one is the flux linkage of the unaligned position “tooth-to-slot”, the other is that of the aligned position “tooth-to-tooth”. The area enclosed by the black curve is the electromagnetic torque of the SRM, and the red one is that of the PMa-SRM. The PMa-SRM’s flux linkage is produced by the permanent magnet and the armature winding. The two red curves bodily move to the negative half-plane of the flux linkage and current, and the enclosed area is larger and the electromagnetic torque increases.

2.2. Mathematical Model

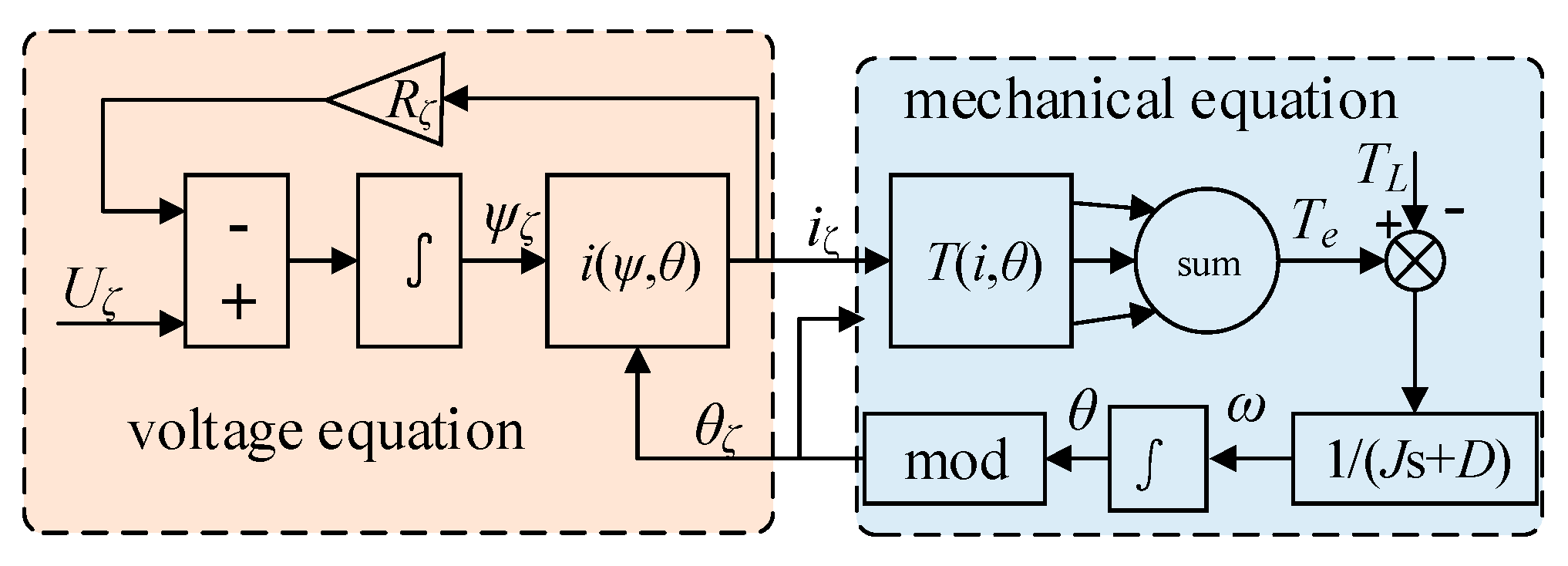

As shown in

Figure 3, a mathematical model is established based on the voltage equation of winding and electromechanical equation of PMa-SRM.

The voltage equation of the windings is

where

Uj,

ij,

Rj, and

ψj are the voltage, current, resistance, and flux linkage of the

j-th phase windings, respectively, and

Mζ is the flux linkage of permanent magnet. The flux linkage will change when the current of the phase windings and the position of the rotor change in the reluctance motor; that is, the look-up table

ψj (

i,

θ) can be obtained if the current and position are given. The current

ij (

ψ,

θ) in

Figure 3 can also be obtained from the flux linkage if the position of the rotor is given; that is, the inversion current can be checked.

where

Te,

TL,

J, and

D are the electromagnetic torque, load torque, moment of inertia, and viscous friction coefficient, respectively. The electromagnetic torque can be acquired by the look-up table from the rotor position and the current.

Building the mathematical model of the PMa-SRM requires the

ij (

ψ,

θ) and

Tj (

i,

θ) from

Figure 3, where winding current changes with the flux linkage and rotor position, and the electromagnetic torque changes with the current and rotor position. As shown in

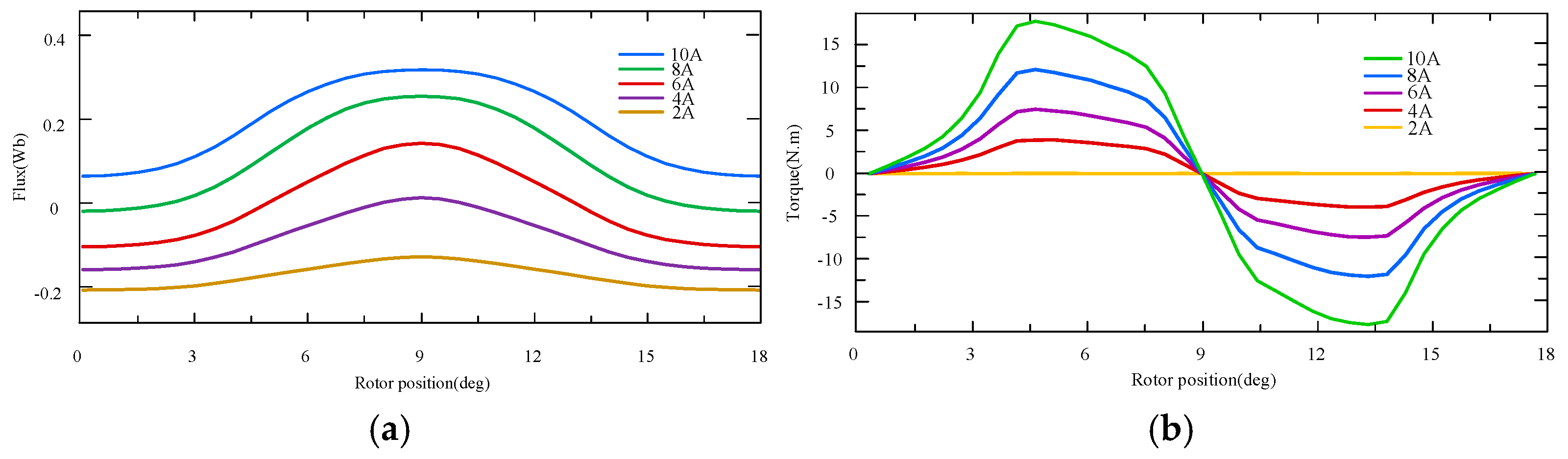

Figure 4, the characteristic curve of the flux linkage

ψj (

i,

θ) and torque

Tj (

i,

θ) can be acquired by static field simulation in Maxwell. However, the current

ij (

ψ,

θ) cannot be acquired, because the switched reluctance motor (SRM) modeled in Maxwell software must be driven by an external circuit, which adopts the form of a three-phase voltage source bridge inverter circuit. The external circuit provides a DC voltage of 240 V, and achieves current control through a chopping method by setting the current limiting amplitude. In Maxwell, the flux linkage characteristic curve can be obtained through simulation by specifying the voltage, current, and stator/rotor position; however, as an input variable, the current cannot be directly obtained through Maxwell simulation. So, an inverse interpolation method is present in the next section.

2.3. Inverse Interpolation Method

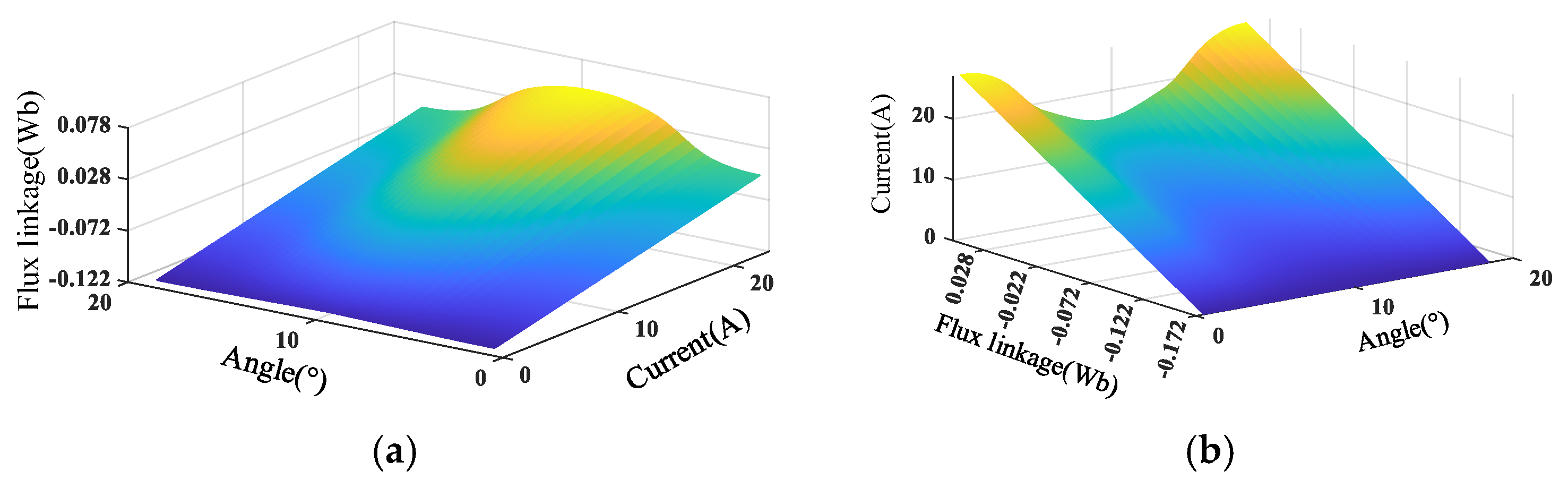

Assuming the motor is completely symmetric, its inductance distribution has a nonlinear correlation with both current and the stator/rotor position. The flux linkage of the PMa-SRM is nonlinear, as shown in

Figure 5a; the flux linkage data matrix has the dimensions 450 × 37, with the rotor angle ranging from 1 to 18 degrees in steps of 0.5; and the current ranges from 0 to 24 in steps of 0.05. Due to the nonlinearity of the curve, an inverse calculation using linear interpolation was employed. The data was then linearized with reference to Equation (3).

where

and

are the maximum and minimum flux linkage, respectively. The maximum flux linkage is produced when the rotor reaches the complete alignment position and the current simultaneously reaches the maximum value. The minimum flux linkage is generated when the rotor reaches the completely unaligned position and the current is zero. This interval between the complete alignment position and the unaligned position is subdivided into

N, which is set to 1000 to compromise for the accuracy and calculation speed of the model.

Owing to the nonlinear magnetic circuit, the data on the flux linkage obtained by simulation is inconsistent with that obtained by linearity at the same rotor position, so linear interpolation method is presented below. If the smaller flux linkage occurs near the nonaligned rotor position when the current is small, there is no current value corresponding to this flux linkage near the aligned position, and the data needs to be supplemented. Conversely, if there is no larger current corresponding to the large flux linkage near the nonaligned position, the data also needs to be supplemented. Therefore, there are three cases, as outlined below.

①

: when the rotor is at some fixed position, the linearized flux linkage is greater than the flux linkage which is generated when the current is zero, and less than that when the current is at its maximum. The current is obtained from the linear quadratic interpolation formula below.

where both

and

are the flux linkage of two neighboring points;

and

are the corresponding current values.

② : the flux linkage calculated by linear interpolation is smaller than that generated by simulation software when the current is zero.

It can be seen from

Figure 5b that, owing to the presence of permanent magnet, the flux linkage may be negative at certain position even though the current is zero. Therefore, the current is zero in the inverse interpolation; that is,

③ : the flux linkage is larger than that generated by simulation software even if the current is at its maximum.

There is no corresponding current in the inverse calculation in this case. The magnetic circuit is in a high saturation state, and the flux linkage hardly varies. It is impossible that

occurs in the actual simulation analysis and the prototype experiment. The current is calculated by formula 6 below, which has no effect on the model.

Therefore, the nonlinear model developed in this paper for the PMa-SRM achieves a high accuracy and rapid response. Moreover, this model is mainly applied to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed control strategy through theoretical analysis and simulation.

3. Conventional TSF

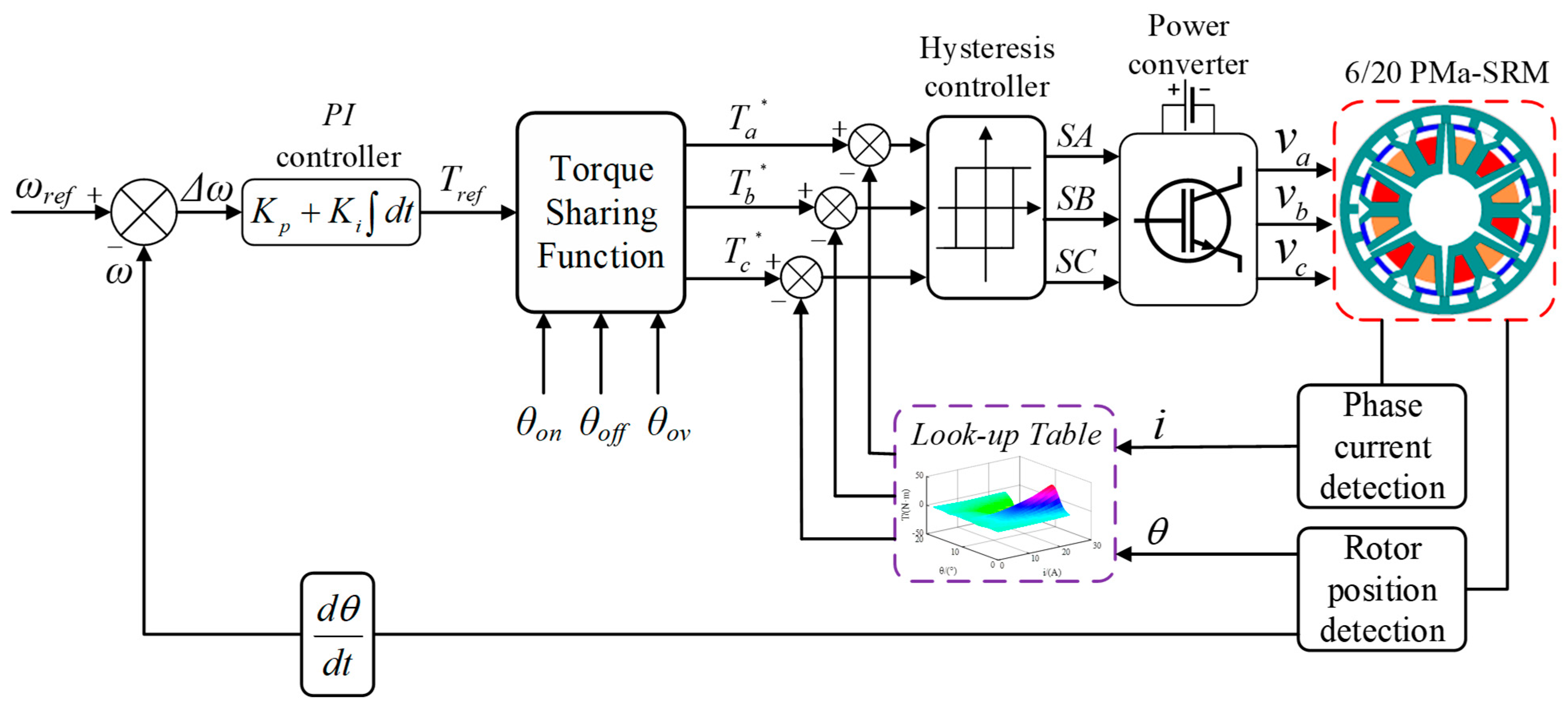

3.1. Conventional TSF Control System

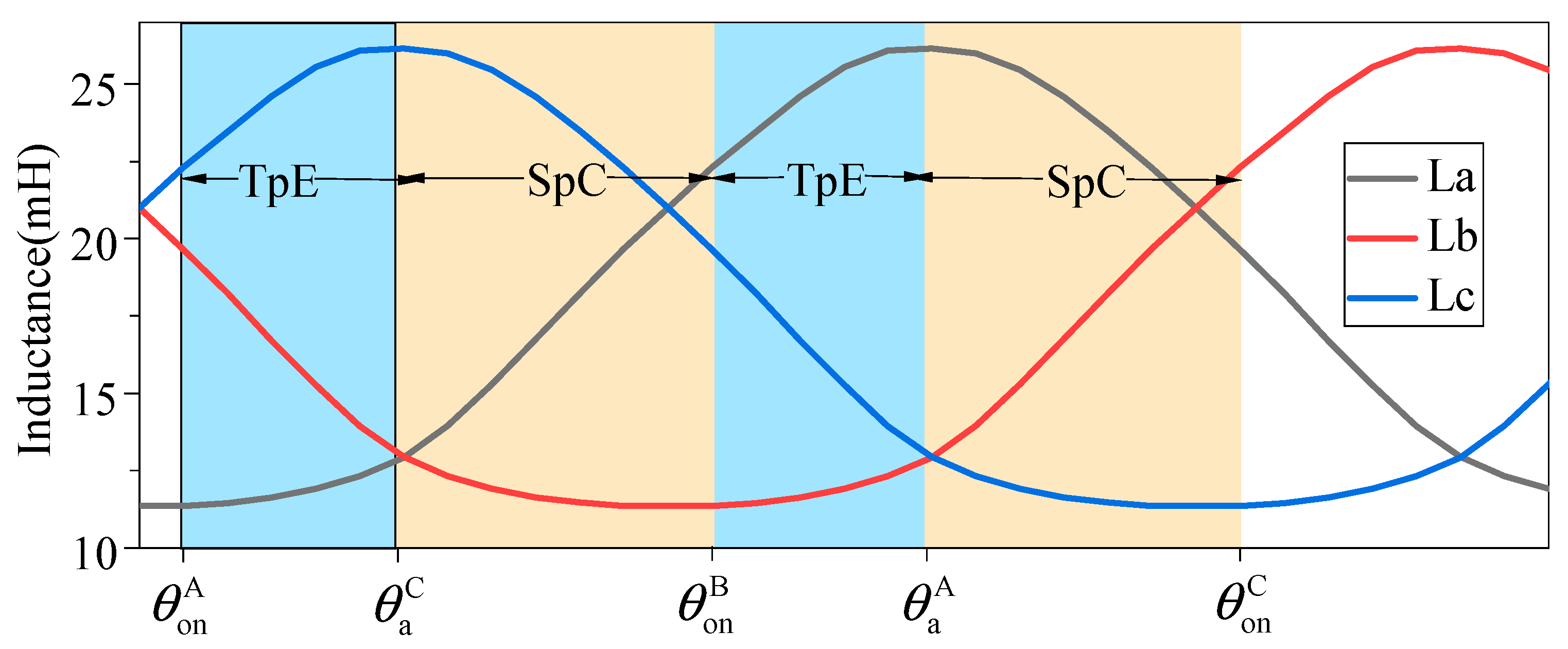

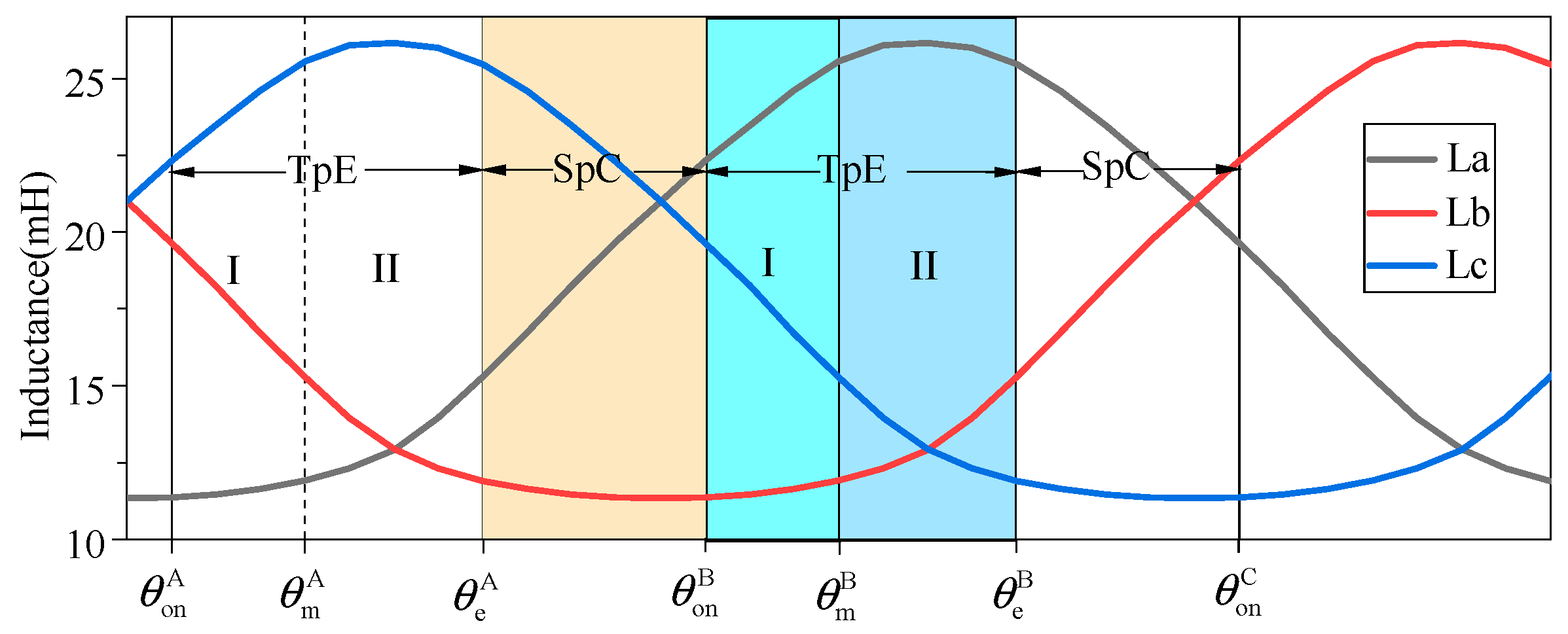

The three-phase windings are sequentially excited once during a mechanic angle of the rotor pole. As shown in

Figure 6, the electrical angle of one phase winding, which is excited, is subdivided into two regions based on the inductance characteristic curve in the conventional TSF; that is, the single-phase conducting (SpC) region and two-phase exchanging (TpE) region. The torque of the incoming phase rises in the TpE, and that of the outgoing phase decreases.

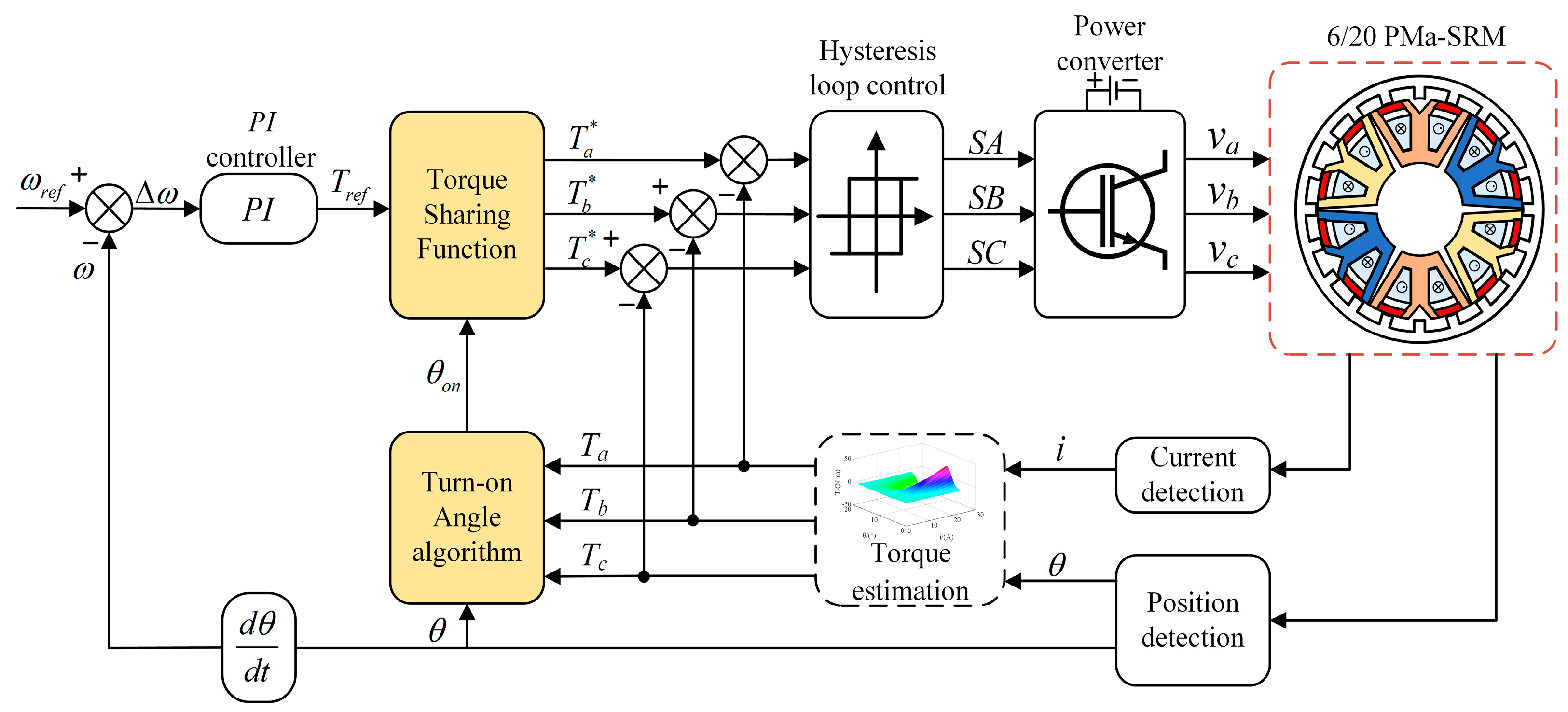

The conventional TSF control system consists of a look-up table, PID module, torque sharing function, and hysteresis control, as shown in

Figure 7. The error between the actual and reference speed is input into the PID module, and the instantaneous reference torque of each phase winding can be allocated by TSF, the turn-on angle, turn-off angle, and overlapped angle. The actual torque obtained by the look-up table is compared with the instantaneous reference torque in the hysteresis controller to control the power converter.

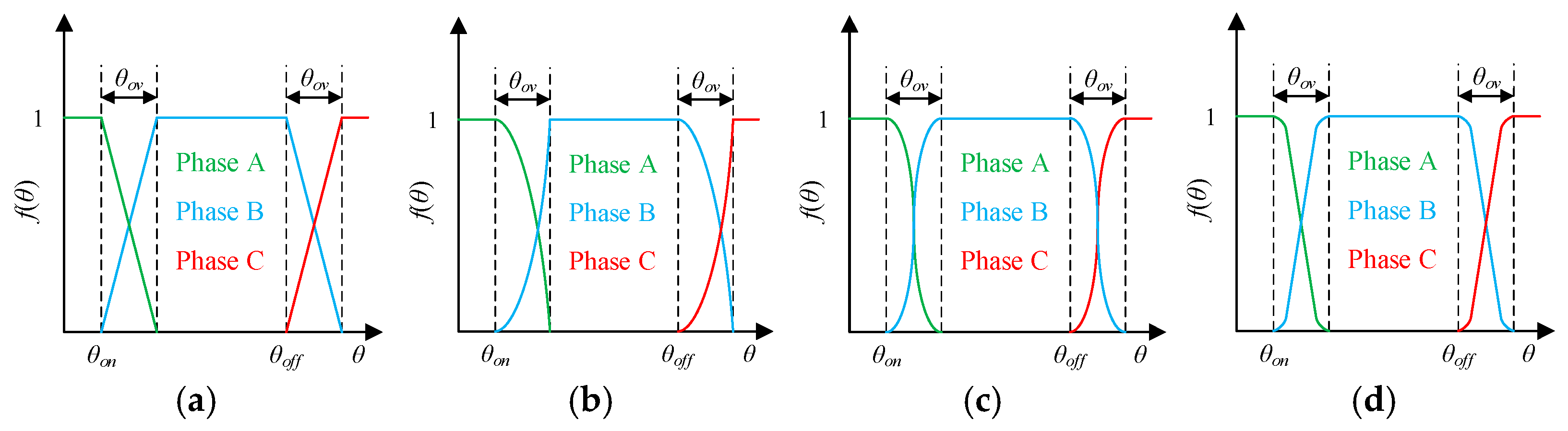

3.2. Conventional Torque Sharing Function

The TSF module assigns the reference torque to three-phase windings based on the TSF curve so that the electromagnetic and reference torque are equal in the TpE region.

(

k = 1, 2, 3) is defined as the torque sharing function, which must be met with the following formula:

The two-phase windings provide output torque in the TpE simultaneously, but only in one phase winding in the SpC.

is generally expressed as below:

where

R(

θ) is the TSF curve of the incoming phase in the TpE, which is generally of four types—linear, exponential, sine, and cubic—as shown in

Figure 8.

θon,

θoff, and

θov are the turn-on angle, turn-off angle, and overlap angle, respectively. At the same position, the output phase winding is disconnected and the input phase winding is independently connected; that is, the output phase angle

is equal to the input phase angle

.

3.3. Cause of Torque Ripple Generation

The torque ripple can be effectively decreased by the conventional TSF strategy, but it is still larger in the TpE region when the load and speed vary. On the one hand, both the current of the outgoing phase and the rate of inductance changing simultaneously decrease in the first half of the TpE region, which leads the electromagnetic torque to drop obviously. It is smaller than the reference torque allocated to the outgoing phase. In addition, the small inductance changing rate of the incoming phase only produces a small electromagnetic torque. It is also smaller than the reference torque allocated to the incoming phase. Therefore, the electromagnetic torque cannot quickly track the reference torque, and a lower torque ripple appears.

On the other hand, the torque ripple is larger when the rotor is in the second half of the TpE region. It can be seen from Formula (2) that the angular acceleration is negative when Te is less than TL, and the angular velocity begins to decrease, resulting in the actual speed being less than the reference speed. In order to quickly track the reference speed, the speed loop needs to be adjusted, resulting in the reference torque being greater than the actual torque. In addition, the changing rate of the incoming phase inductance starts to increase, and the electromagnetic torque increase rapidly. Therefore, the total torque is large, and the value of the torque ripple peaks.

Furthermore, the conduction angle is fixed in the conventional TSF scheme, so the range of speeds is relatively narrow. This will cause a greater torque ripple, especially at high speeds. A TSF control method with an adaptive turn-on angle in three regions, can effectively decrease the torque ripple for partial loads and speeds.

4. Novel TSF with Three Regions

Although the conventional TSF control method can decrease torque ripple, the range of speeds and loads is limited. Both the current and rotor position need to be detected, and the torque of each phase winding also needs be estimated in the conventional TSF control method. A TSF control method with an adaptive turn-on angle in three regions is presented, which can automatically regulate the turn-on angle based different speeds and loads.

4.1. Subdivided Region

The electrical angle of one phase winding, which is excited, is subdivided into three regions, that are the two phase-exchanging regions, TpE I and TpE II, and the single phase-conducting (SpC) region; the end point of TpE II is a fixed angle where the rear edge of the rotor just meets the front edge of the stator, as shown in

Figure 9.

The position where the inductance of the incoming phase obviously changes is named the inductance boundary point, where the TpE is separated into two regions; that is, TpE I and TpE II. The starting point of TpE I is defined by the turn-on angle of the incoming phase. This angle is determined by an optimized function that considers different speeds and loads. The endpoint of the TpE II region is at the aligned position. This is a fixed angle defined as the instant when the rear edge of the rotor aligns with the front edge of the stator, and the inductance of the outgoing phase begins to decrease. After the outgoing phase is demagnetized in TpE I and TpE II, its current is very small or zero, so the electromagnetic torque can be ignored.

4.2. Control Method

The control block diagram of a TSF control method with an adaptive turn-on angle in three regions is shown in

Figure 10. Compared with the conventional TSF, an adaptive turn-on angle module and a new torque sharing function are added in the novel TSF in accordance with the characteristics of inductance in the TpE regions.

Taking the A and B phases as examples, with the phase A acting as the outgoing phase and phase B as the incoming phase, the TSF control method is set in each region for the outgoing and incoming phase. Half of the electromagnetic torque is provided, respectively, by phases A and B at the inductance boundary points .

SpC region (

): only phase A works, while phase B and phase C do not work. Therefore, the TSF expression is described in this region as

TpE I region (

): the changing rate of incoming-phase inductance is very small, and only a little electromagnetic torque can be generated. Most of it is provided by the outgoing phase. Therefore, phase B is always excited to rapidly raise the current, and phase A is controlled to diminish the torque ripple. The turn-on angle is inversely calculated by the optimized turn-on angle formula. The TSF expression is described in TpE I as

TpE II region (

): the changing rate of the incoming-phase inductance quickly grows, and most of the electromagnetic torque comes from the incoming phase. The current of the outgoing phase should be quickly reduced to refrain from generating a large negative torque in the next SpC. Therefore, phase A is turned off all the time, and phase B is controlled to reduce the torque ripple. The TSF expression is shown in the TpE II as

In conclusion, the expression of the new TSF curve is

where

Rk =

Tk/

Tref and

k represents the A, B, and C phases;

Tk and

Tref represent the torque of each phase and the reference torque, respectively.

5. Adaptive Turn-On Angle Algorithm

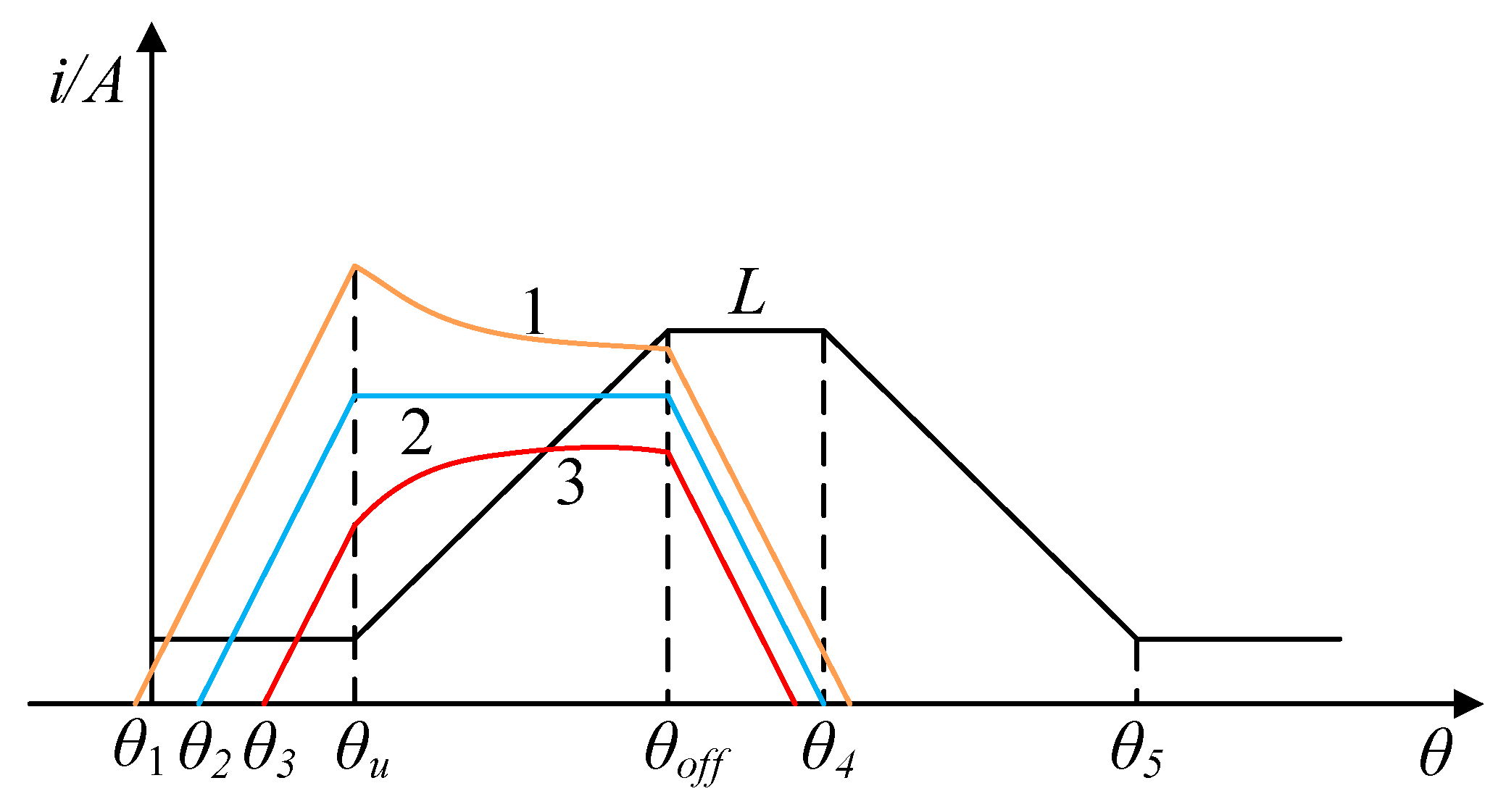

A larger incoming phase current is needed to produce sufficient electromagnetic torque in cases of a heavy load. However, the current of the outgoing phase will reduce rapidly to prevent negative torque. The current of the incoming phase cannot track the reference current at the fixed conduction angle, and it does not have enough time to reduce the current of the outcoming phase. So, the motor cannot carry a large load at a fixed conduction angle mode.

The turn-on angle has an important effect on the current and torque of phase windings. As shown in

Figure 11, if the turn-on angle

θon is at the position

θ1, the phase winding is excited for a long time during the small inductance region, so the current is larger, resulting in a larger torque. Conversely, if

θon is at the position

θ3, the torque is smaller, which will reduce the efficiency of the motor. Only when

θon is at the appropriate position

θ2, is the waveform of the phase current nearly flat, and the torque ripple small.

The turn-on angle also has a certain influence on speed variation. In the low-speed region, an earlier turn-on angle helps extend the current conduction time, ensuring that the phase current can fully build up during the period of the inductance rising. As the speed increases, the back electromotive force (EMF) of the motor also rises, significantly restricting the rate at which the phase current builds up. Adopting a turn-on angle that precedes the minimum inductance position provides the necessary time advance for current growth. If the turn-on angle is set too late, the current will be unable to track the reference waveform in time, leading to insufficient torque output at high speeds. The optimization of the turn-on angle essentially represents a dynamic trade-off between the torque output capability and the upper operational speed limit.

In order to optimize the turn-on angle, an online turn-on angle optimization function is designed based on the mathematical model for the PMa-SRM. The online optimization of the turn-on angle could maintain system performance, reducing sensitivity to speed estimation errors to some extent.

is substituted into Formula (1), and the differential of flux linkage can be expressed as

The upper equation is integrated with both the turn-on angle

and the inductance boundary point

as follows:

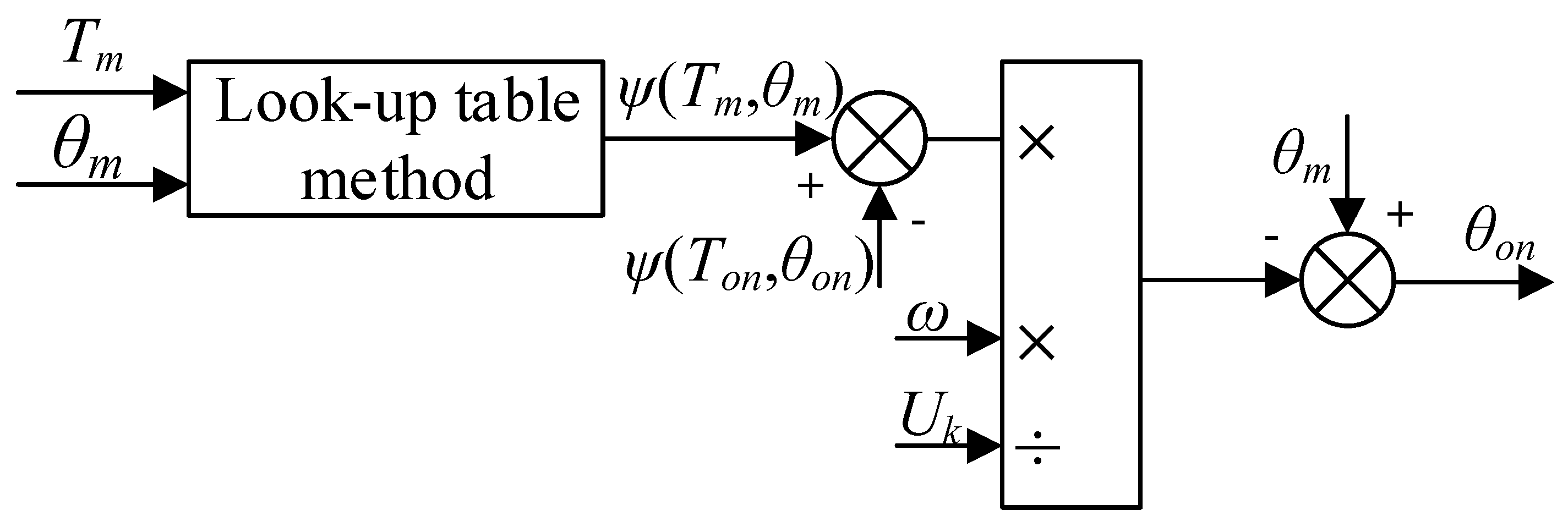

Finally, the updated turn-on angle is obtained by

where

Tm is the reference torque at the inductance boundary point, and

Ton is the torque at the turn-on angle

θon;

and

are the flux linkage at

θm and

θon, respectively, both of which can be obtained by software simulation and digital interpolation. The control block diagram of the turn-on angle is shown in

Figure 12, and

Tm is the phase reference torque from the TSF; the derived turn-on angle

θon is a critical and dynamic optimization variable, adjusted in real-time according to the motor’s operating conditions. To mitigate the sensitivity to interpolation errors inherent in the lookup table method, this study utilizes a high-accuracy lookup table, thereby minimizing the associated errors and improving overall system robustness.

According to Equation (15), if the torque become larger at the constant speed, the turn-on angle will reduce. The conducting time of the phase winding will become longer, and the current will increase at the same bus voltage. Otherwise, the current decreases.

6. Simulation Analysis

A model of a three-phase 6/20 PMa-SRM is built in Matlab(2023a)/Simulink to prove the feasibility of the novel TSF strategy with an adaptive conduction angle and three regions. The parameters of the PMa-SRM are shown in

Table 1.

The motor’s speed is set at 500, 1000, and 1500 rpm, respectively, and the load is set at 2 N·m. The turn-on angle and overlapping angle are 0° and 3° in the conventional TSF, respectively. The coefficient of torque ripple

Kr is expressed below to compare the performance of ripple suppression.

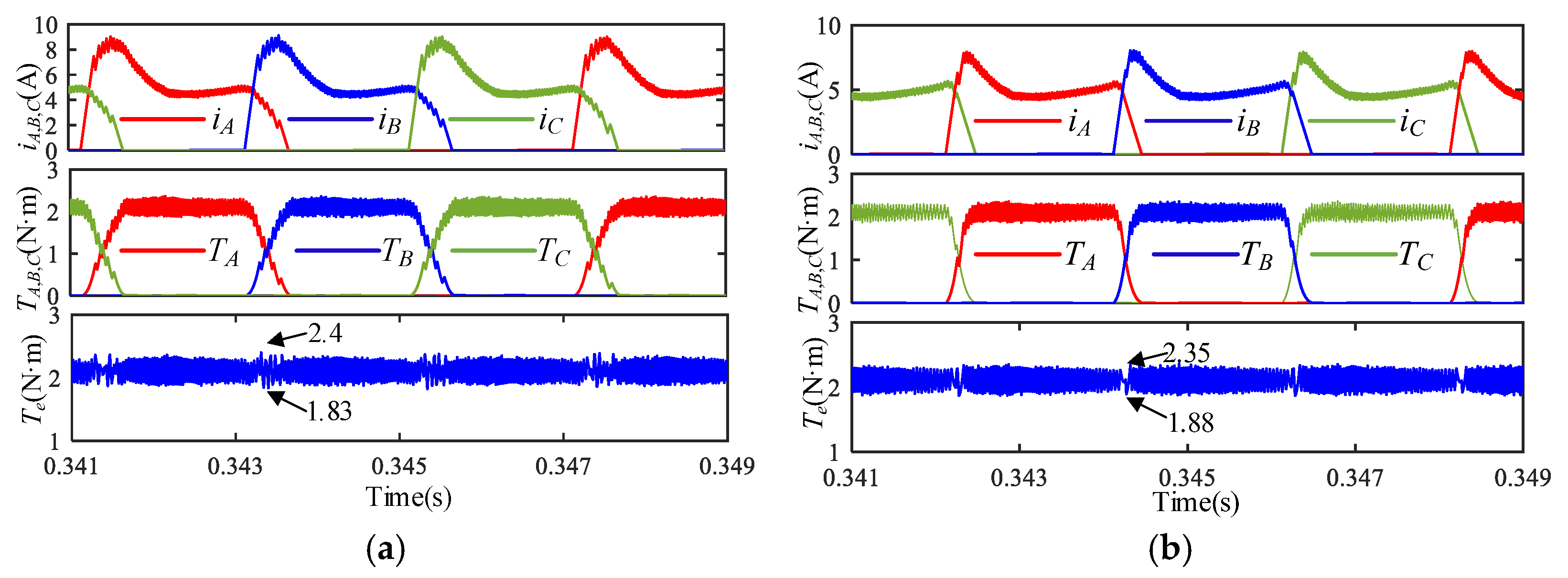

Both the novel TSF and the conventional TSF strategy can suppress torque ripple at low speeds well. The

Kr is 23% in the novel TSF, and 29% in the conventional TSF strategy, as shown in

Figure 13 when the speed is 500 rpm and the load is 2 N·m. In addition, the current peak is smaller, and the current waveform is smoother in the novel TSF.

According to

Figure 14a,b,

Kr is 23% and 58% in the novel TSF method and the conventional TSF method, respectively, when the speed is 1000 rpm and the load is 2 N·m. When the speed increases, there is not enough time for the phase current to be excited, and the average current is small. The changing rate of inductance of incoming phase is light in the TpE I, so a smaller torque is produced. On the contrary, the changing rate of inductance quickly increases in TpE II, resulting in a larger torque. The turn-on angle is 1.1° in

Figure 14b and 1.6° in

Figure 13b, because the time when the incoming phase is excited increases when the speed rises from 500 to 1000 rpm. The incoming phase is always excited throughout TpE I to raise the minimum torque, and the outgoing phase is turned off throughout TpE II so that there is no negative torque.

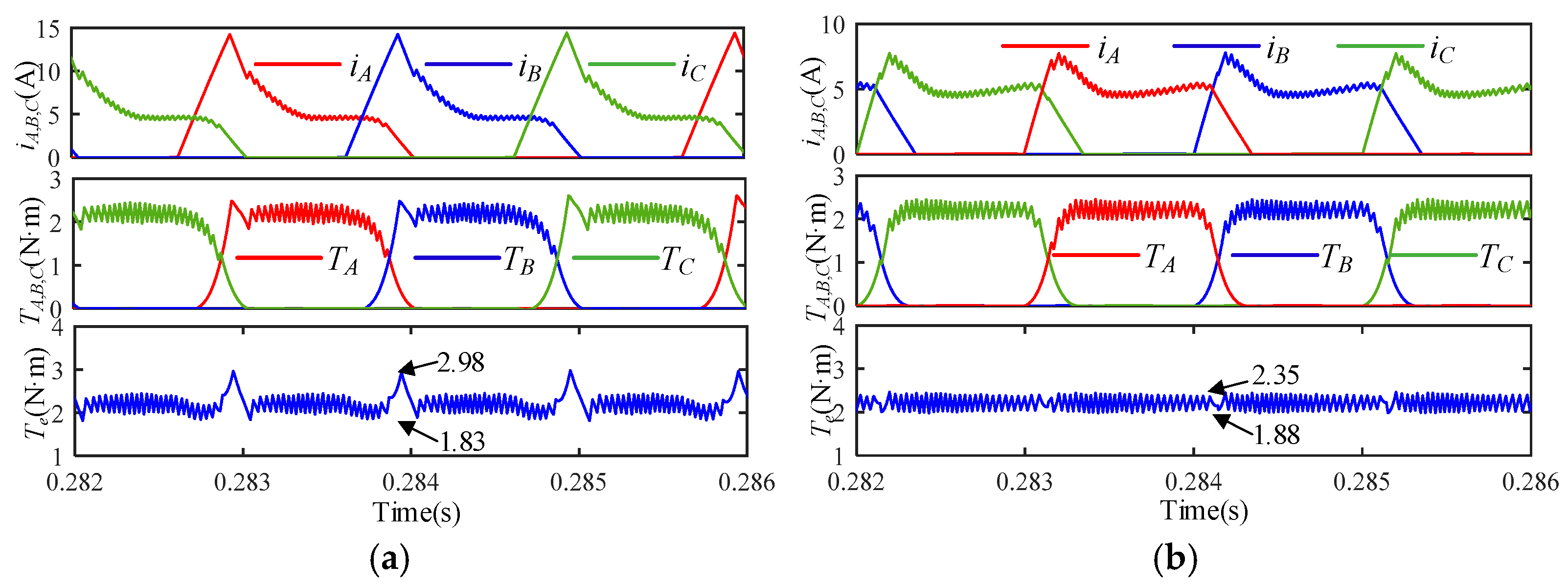

Kr is 25% and 175% in the adaptive turn-on angle TSF control and conventional TSF control in

Figure 15, respectively, when the speed is 1500 rpm and the load is 2 N·m. When the speed increases, the rising time of the incoming phase current shortens and the three-phase synthetic torque is small. Therefore, the reference speed is greater than the actual speed, resulting in a large speed error. The three-phase synthetic torque is enlarged by the outer speed loop to eliminate the speed error, and a large torque ripple emerges.

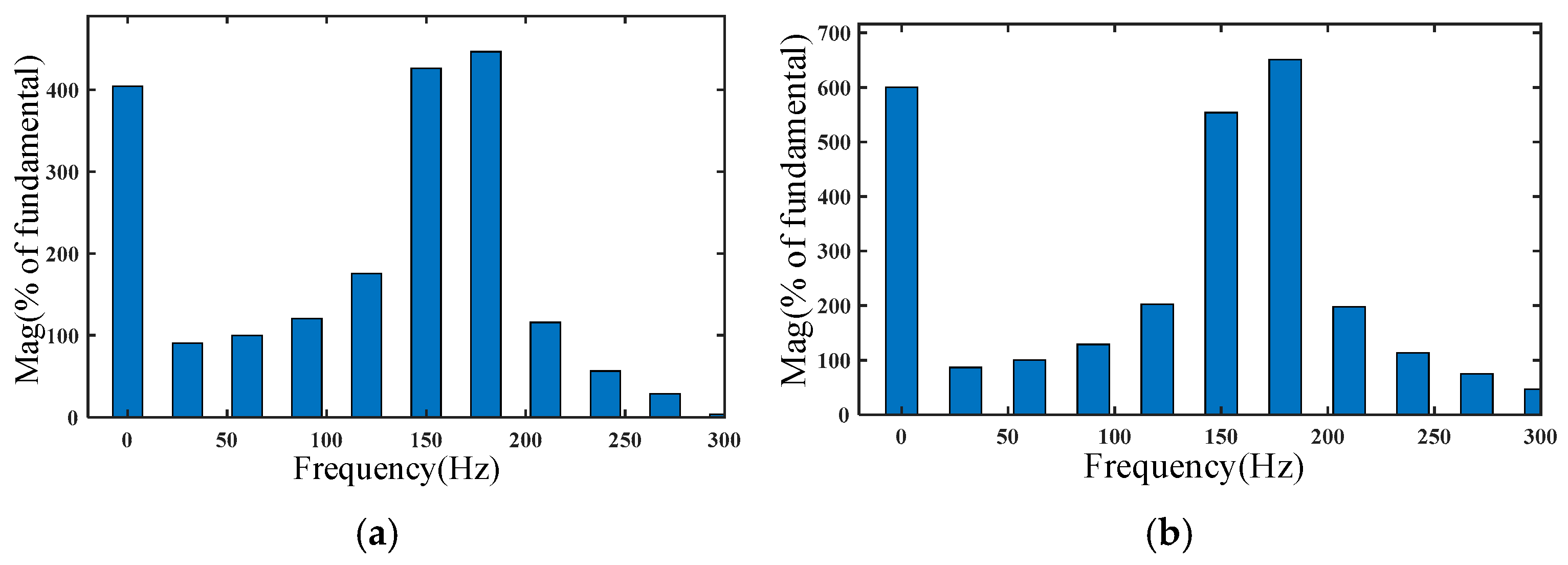

As shown in

Figure 16, by performing FFT on the current, it can be observed that the conventional TSF control strategy exhibits higher magnitudes at 0, 150, and 180 Hz. In contrast, the improved TSF proposed in this paper demonstrates lower overall magnitudes, indicating effective suppression of torque ripple.

The turn-on angle is 0.65° for the conventional TSF in

Figure 15, but it is 1.1° for the novel TSF. Therefore, it has enough time when the incoming phase is excited to increase the electromagnetic torque, resulting in a smaller torque ripple. The conventional TSF does not apply to variable speeds and large loads, and the waveform of the current and torque cannot be obtained, as shown in

Figure 15a. But the novel TSF can do this, as shown in

Figure 15b. The performance of torque ripple at different speeds and loads is shown in

Table 2, and the effect of suppressing torque ripple is very obvious at high speeds and large loads.

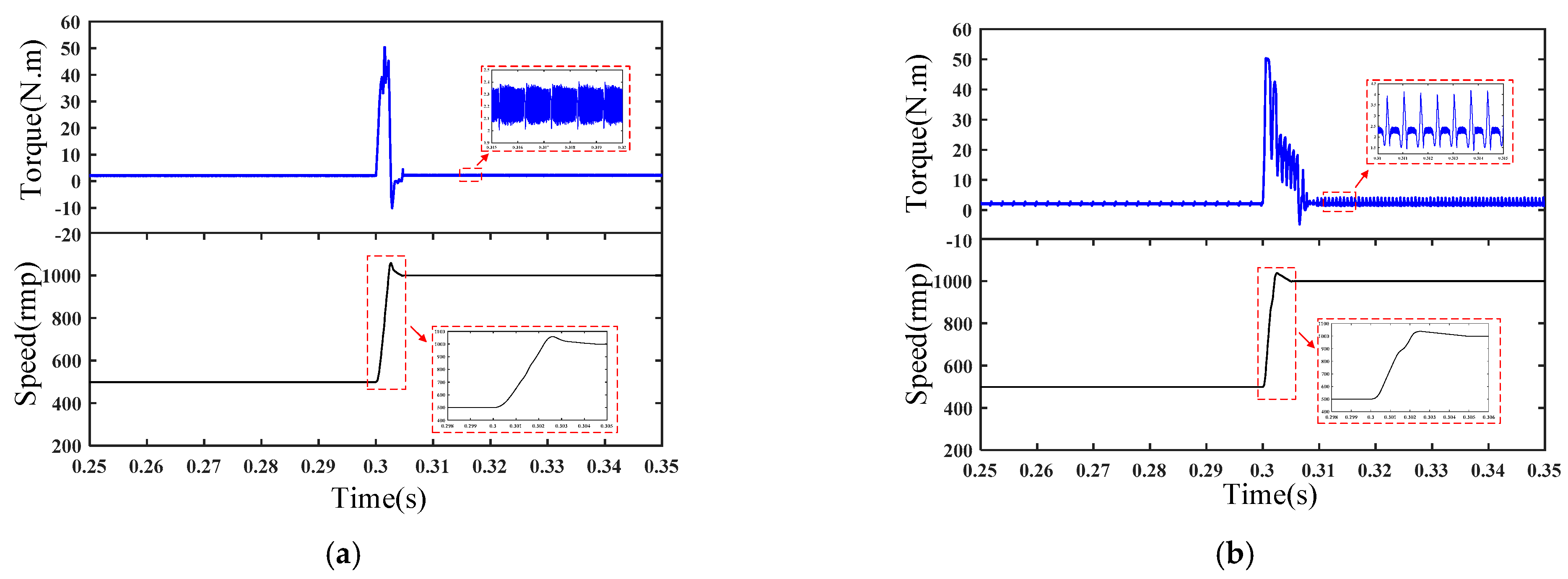

To verify the effectiveness of the control strategy proposed in this paper under speed and load disturbances, the simulation results are shown in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18. The speed and torque waveforms of the control strategy proposed in this paper and the traditional TSF control strategy, under speed disturbances, are shown in

Figure 17a,b. As can be seen from the figure, when the speed increases from 500 r/min to 1000 r/min at 0.3 s, the control strategy proposed in this paper still has a good effect on torque fluctuation suppression during sudden speed changes.

The torque waveforms of the control strategy proposed in this paper and the traditional TSF control strategy under torque disturbances, as shown in

Figure 18. As can be seen from the figure, at 0.3s, the load increases from 2 N·m to 4 N·m, and the control strategy proposed in this paper still has a good effect on suppressing torque ripple during sudden load changes.

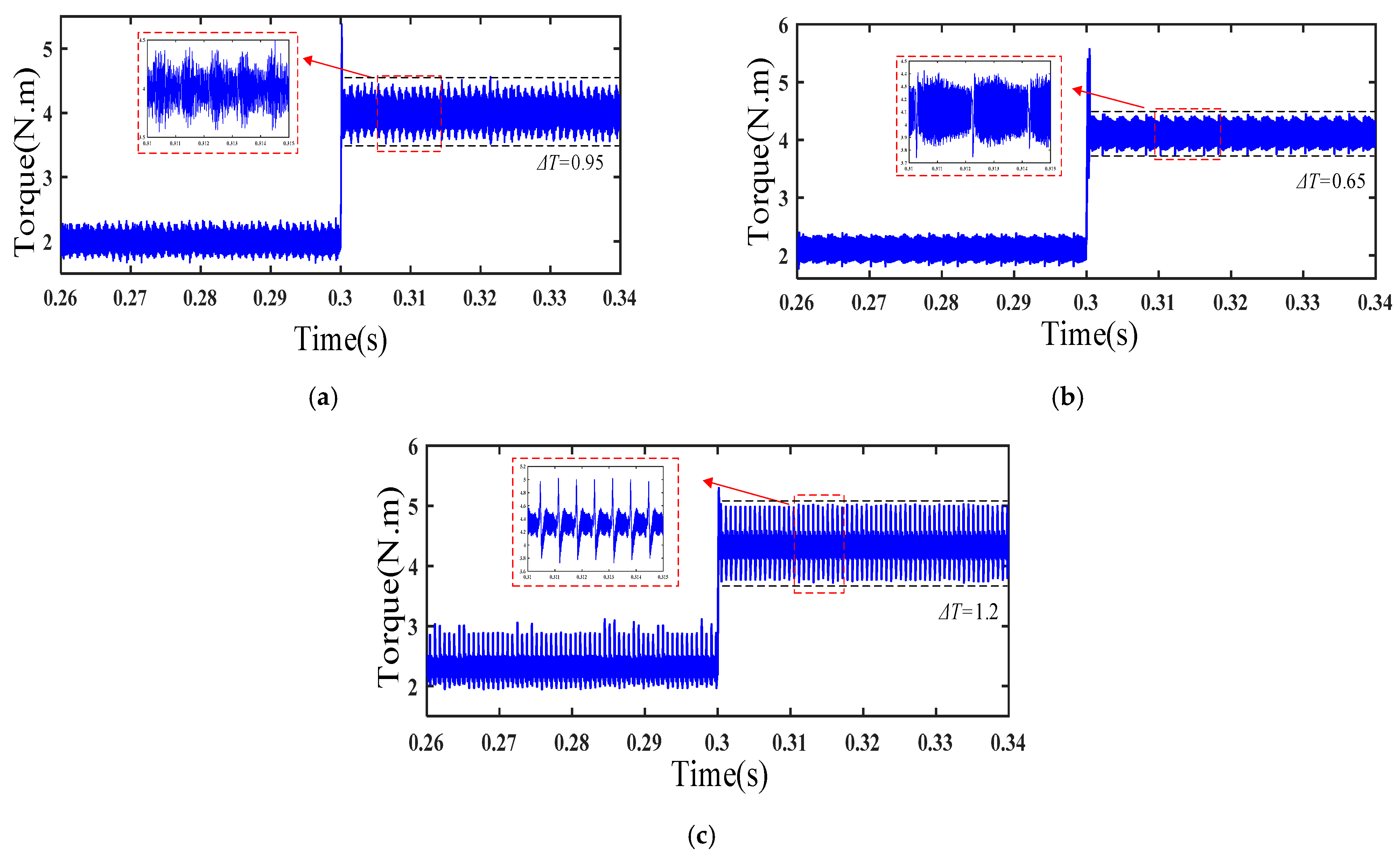

7. Prototype Experiment

To further verify the TSF control method with an adaptive turn-on angle in three regions, an experimental platform for the PMa-SRM is built, as shown in

Figure 19. The TMS320F28335 is employed as the control board, the sampling frequency is 10 kHz, the P parameter in the PI controller is 5, the I parameter is 0.1, an asymmetric half-bridge circuit is taken as the drive board, and a 15-bit absolute encoder is used for real-time position signaling. The experimental platform uses a 15-bit BRT38-COM32768 absolute encoder model manufactured by Britech Technology in Shenzhen, China. The accuracy of this encoder can reach 0.01°. The position signal sent by the encoder is read using the CAN communication protocol F28335. The motor current is measured by an RP1001c current sensor model manufactured by RIGOL in Beijing, China, while the motor speed and torque are measured using an HCNJ-101 sensor manufactured by the Haibohua Technology Company in Beijing, China. The parameters are consistent with the motor parameters in the simulation test.

The hardware implementation of the aforementioned control system is achieved as follows: The rotor position and phase current data, acquired by an encoder and by current sampling, are sent to the TMS320F28335 microcontroller for computation. The TMS320F28335 is manufactured by TI in Dallas, TX, USA. The control algorithm then generates conduction signals, which are output via the PWM module to an asymmetric half-bridge driver. This driver subsequently switches the IGBTs on and off, thus controlling the motor’s operation.

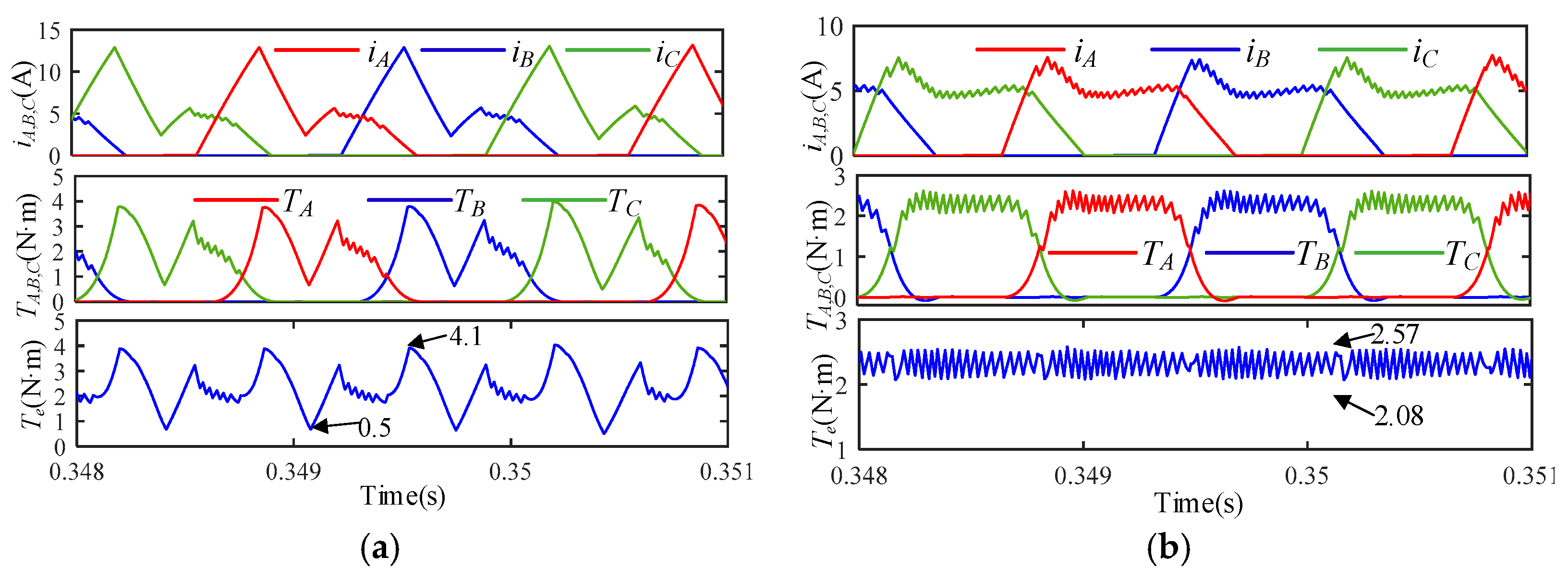

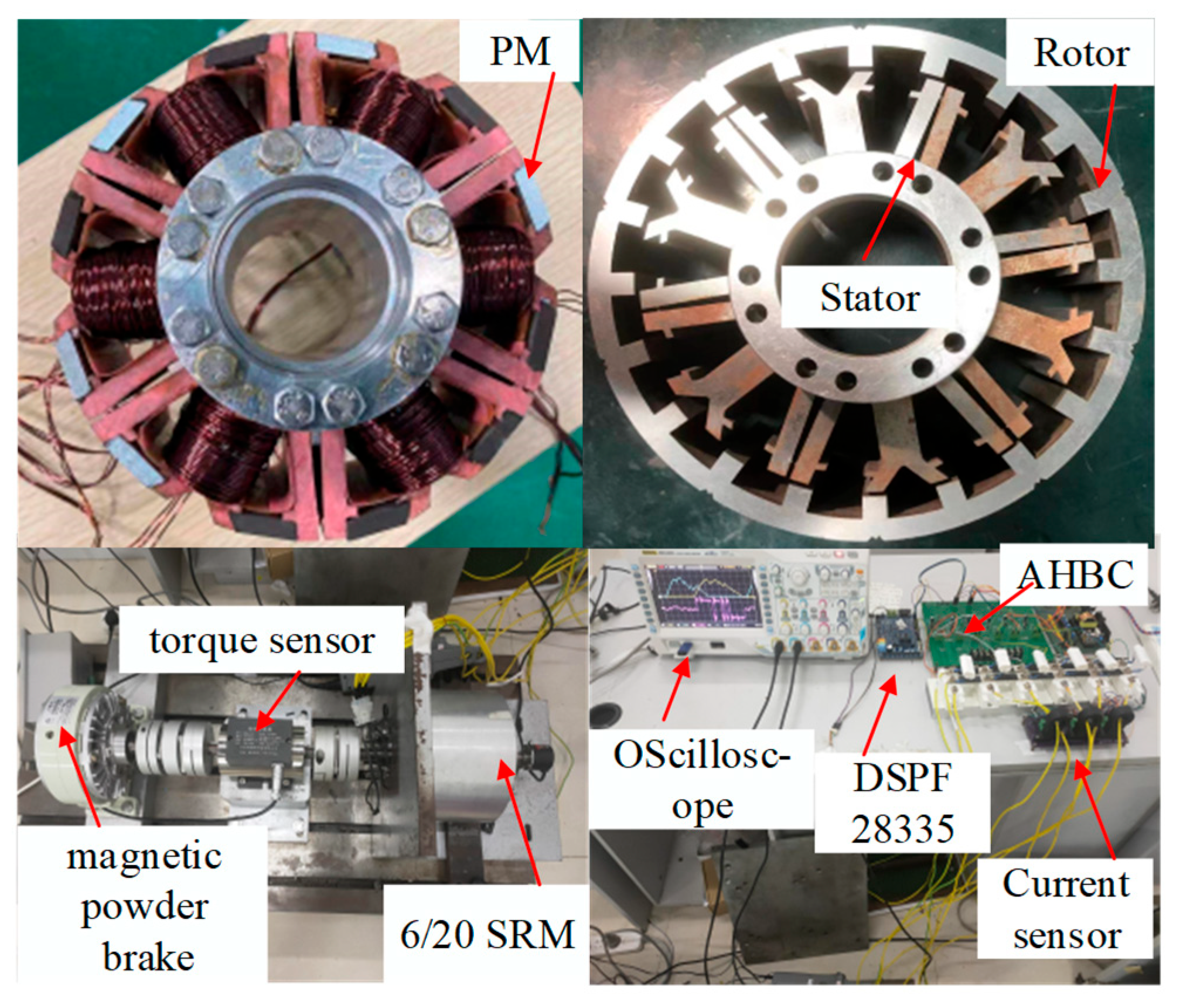

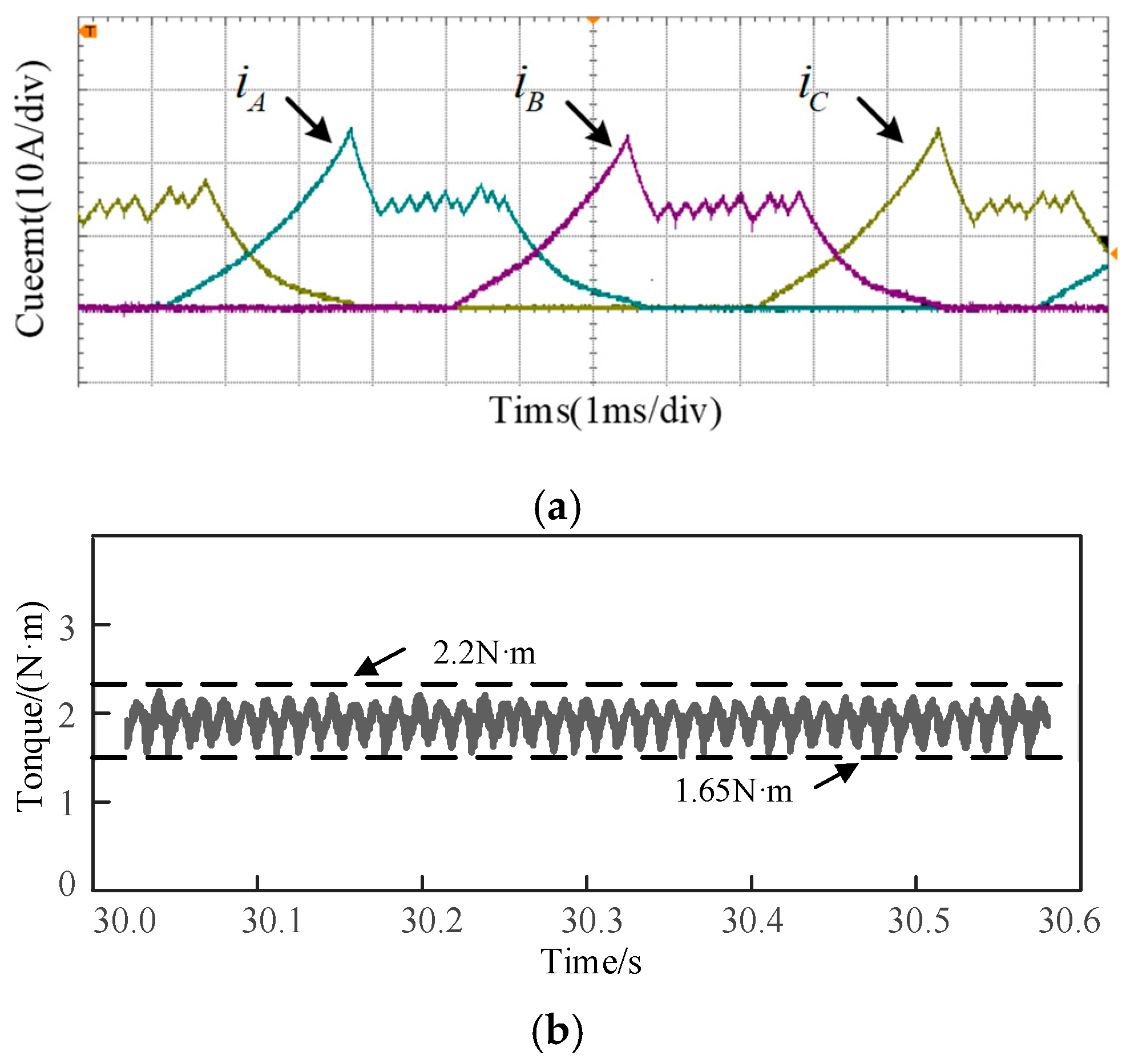

To test the novel TSF strategy, the prototype experiment is carried out in both the conventional TSF and the novel TSF when the load is set at 2 N·m and the speed is 500 rpm. The test results are shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21. In

Figure 20a, owing to the PI control at the speed loop in the conventional TSF strategy, the current slowly increases. But the incoming phase is always excited in TpE I in the novel TSF method in

Figure 21a, so the phase current quickly increases. The torque ripple of the conventional TSF scheme is 40%, as shown in

Figure 20b, and that of the novel TSF method is 27.5%, as shown in

Figure 21b. The torque ripple is significantly reduced.

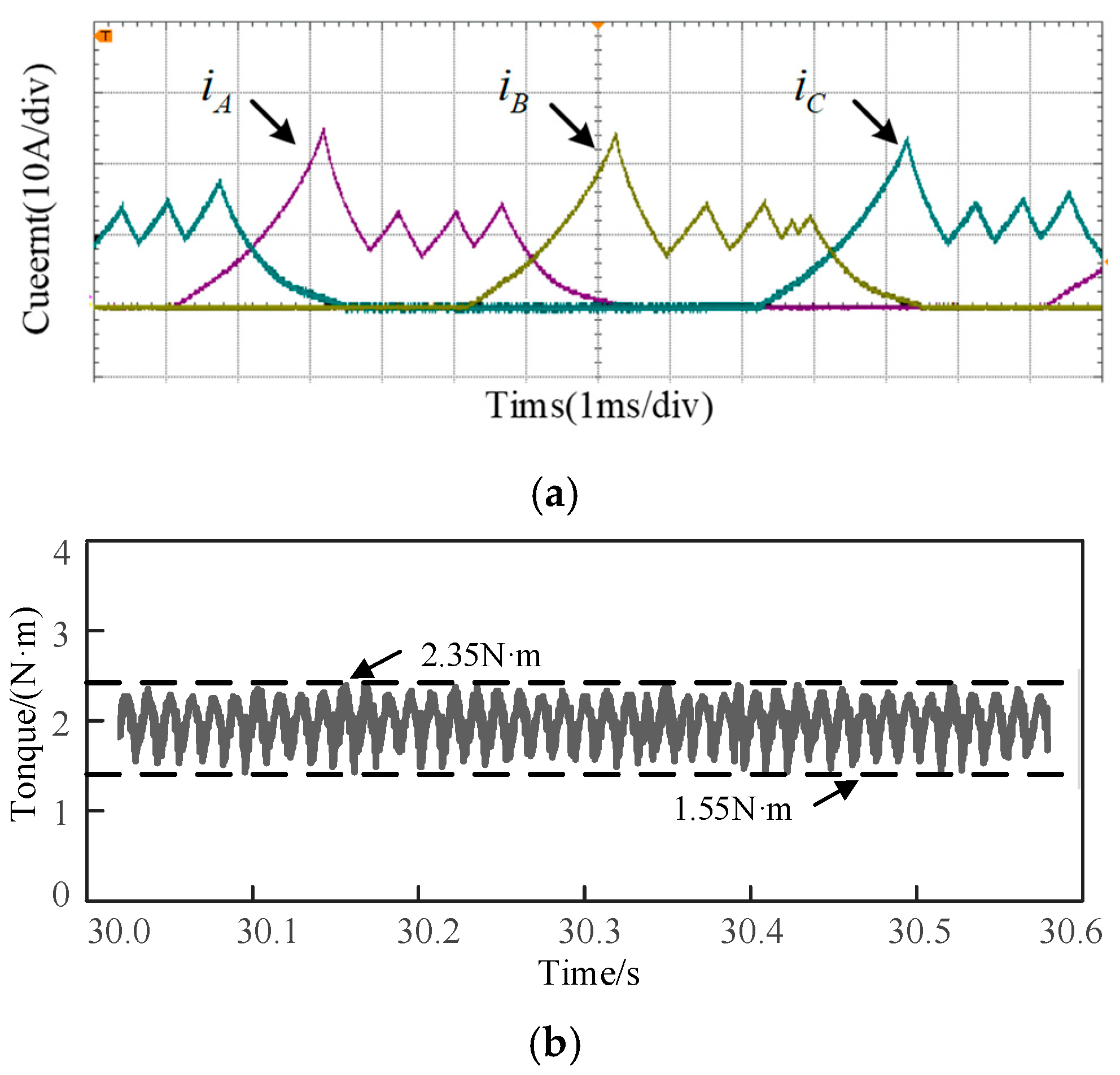

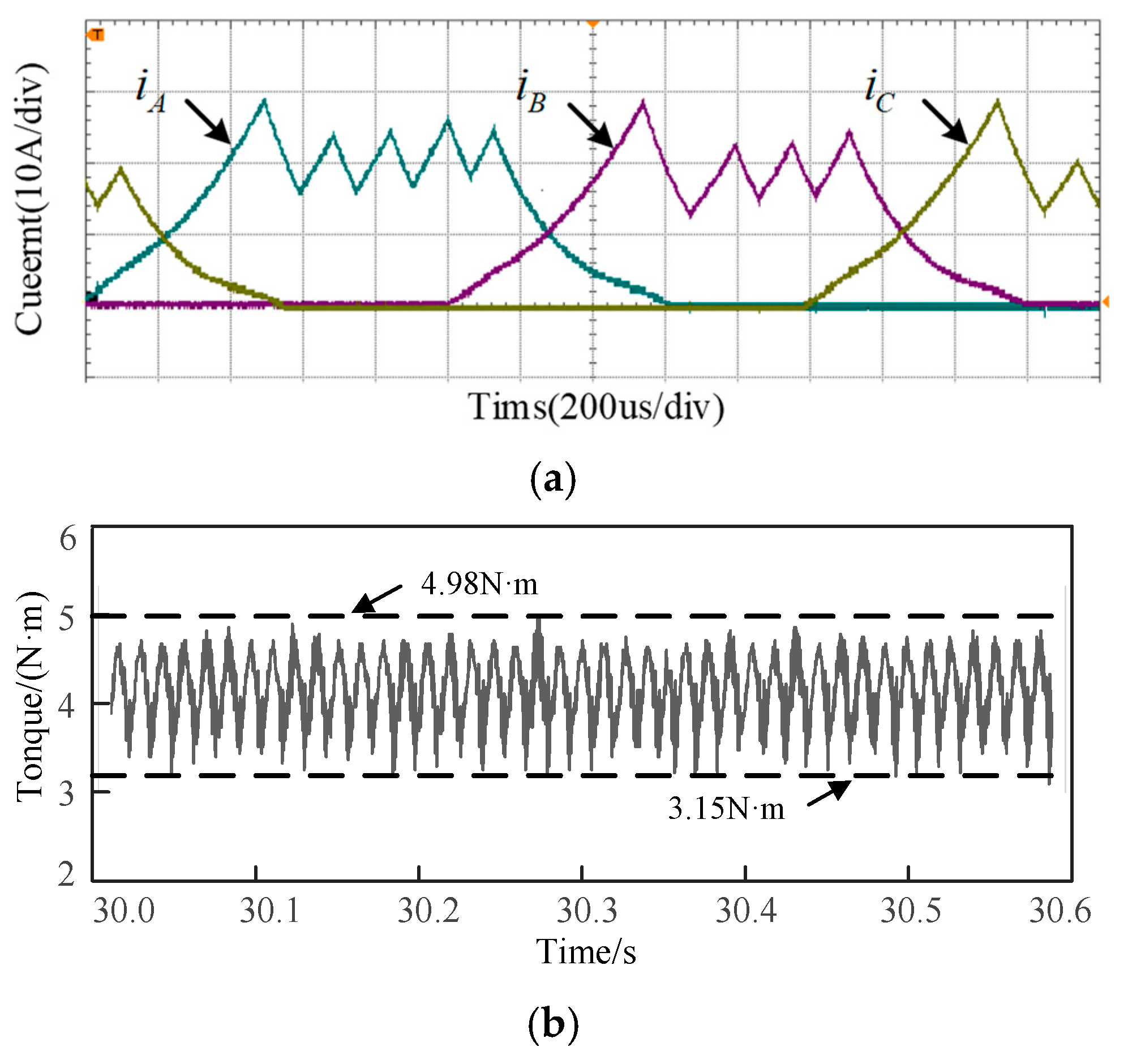

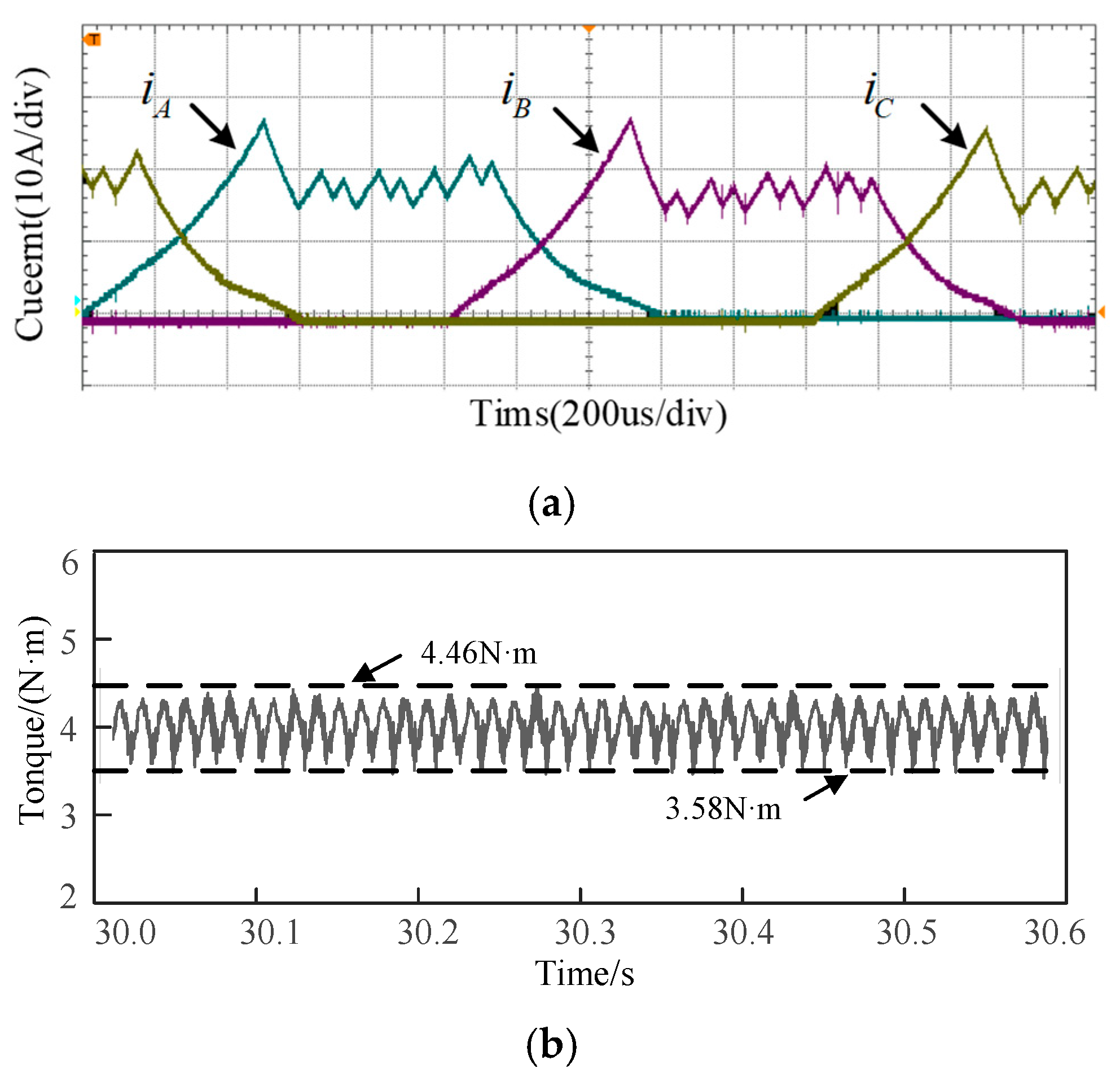

To verify the performance of the adaptive turn-on angle at different rotational speeds and the effectiveness of the proposed control strategy, the prototype experiment is carried out in both the conventional TSF and the novel TSF when the load is set to 5 N·m and the speed is 1000 rpm. The test results are shown in

Figure 22 and

Figure 23. The torque ripple of the conventional TSF scheme is 46%, as shown in

Figure 22b, and that of the novel TSF method is 22%, as shown in

Figure 23b. The torque ripple is significantly reduced.