Development of a Compact Data Acquisition System for Immersive Ultrasonic Inspection of Small-Diameter Pipelines

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

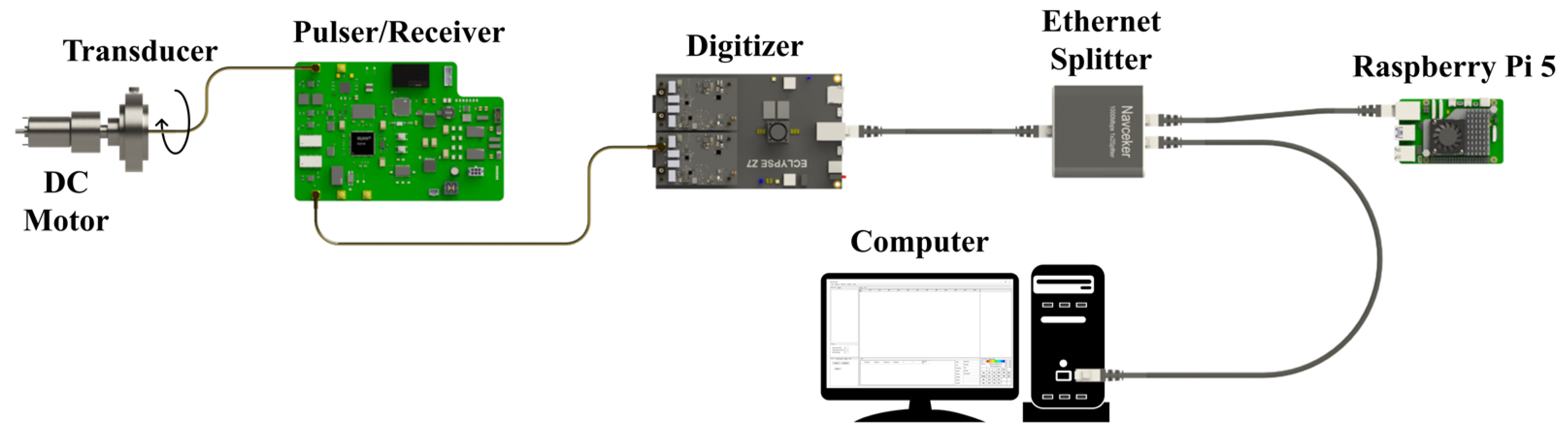

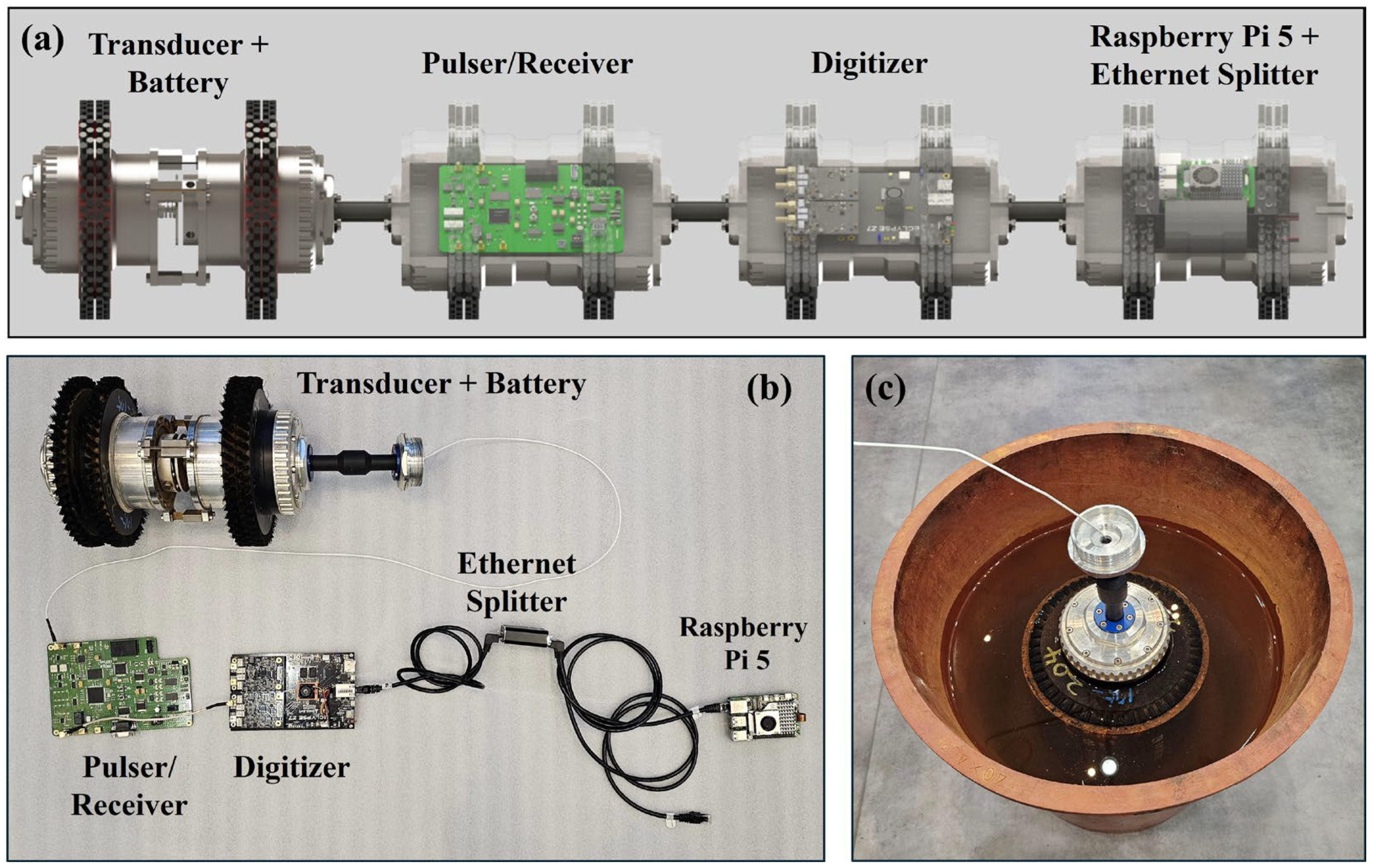

- Compact and fully integrated UT data-acquisition framework for small-diameter pipelines. The proposed system combines a customized high-voltage pulser/receiver, a 14-bit 100 MS/s FPGA-based digitizer, and a Raspberry Pi 5 storage module into a size-restricted PIG platform suitable for 8-inch (200 mm) pipelines, addressing the space limitations that prevent the use of commercial IRIS systems.

- (2)

- Unlike commercial instruments like MS5800 that require tethered PC operation, the system performs in-pipe local data recording using an embedded SSD, enabling long-distance inspection without external communication.

- (3)

- The system achieves smooth A-scan waveforms for both the front and back walls. The wall-thickness accuracy within ±2.5% demonstrates a reliable measurement performance.

- (4)

- Modular hardware structure enables flexible extension to full PIG inspection. The design supports future integration of position encoders and water-driven propulsion, providing a scalable foundation for complete autonomous pipeline inspection.

2. System Design

2.1. System Block Diagram

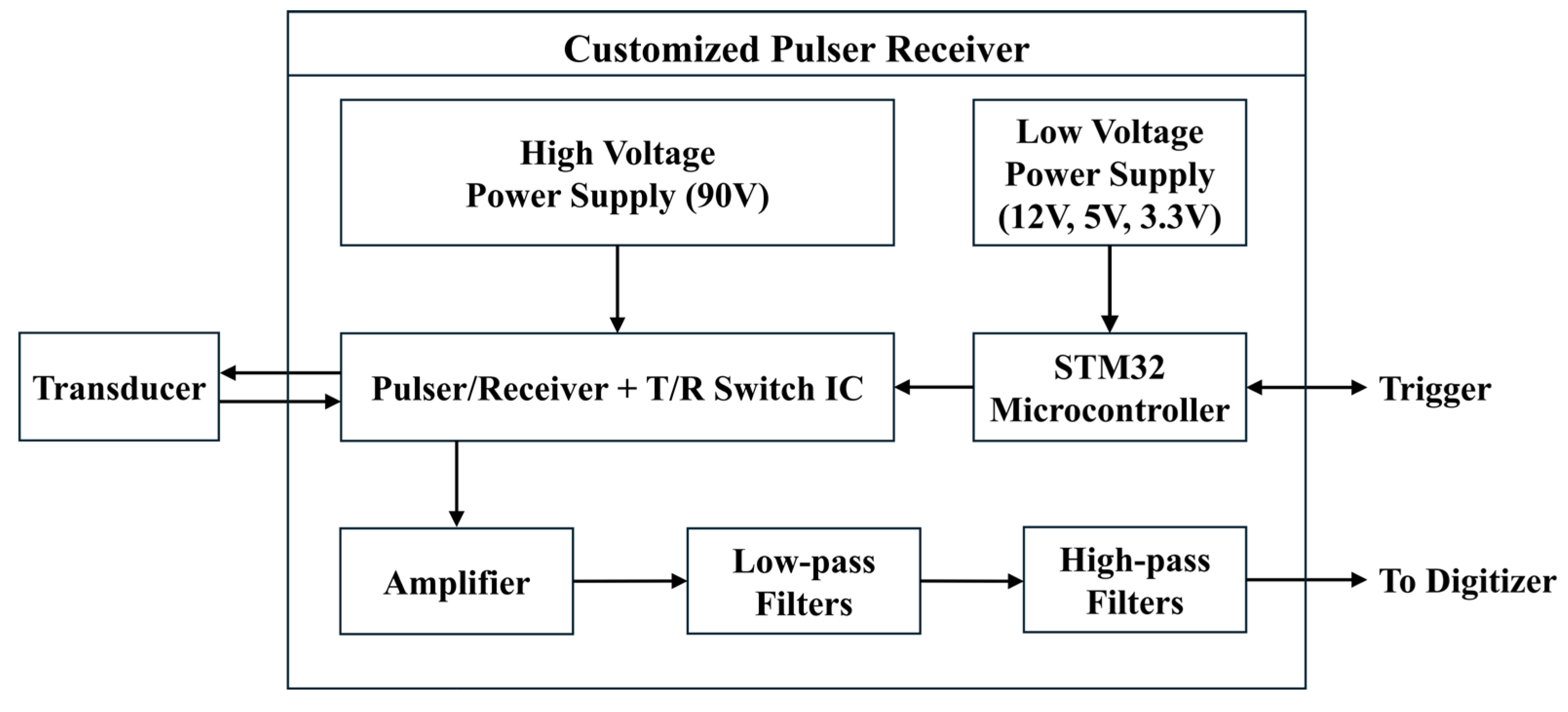

2.2. Pulser/Receiver Architecture

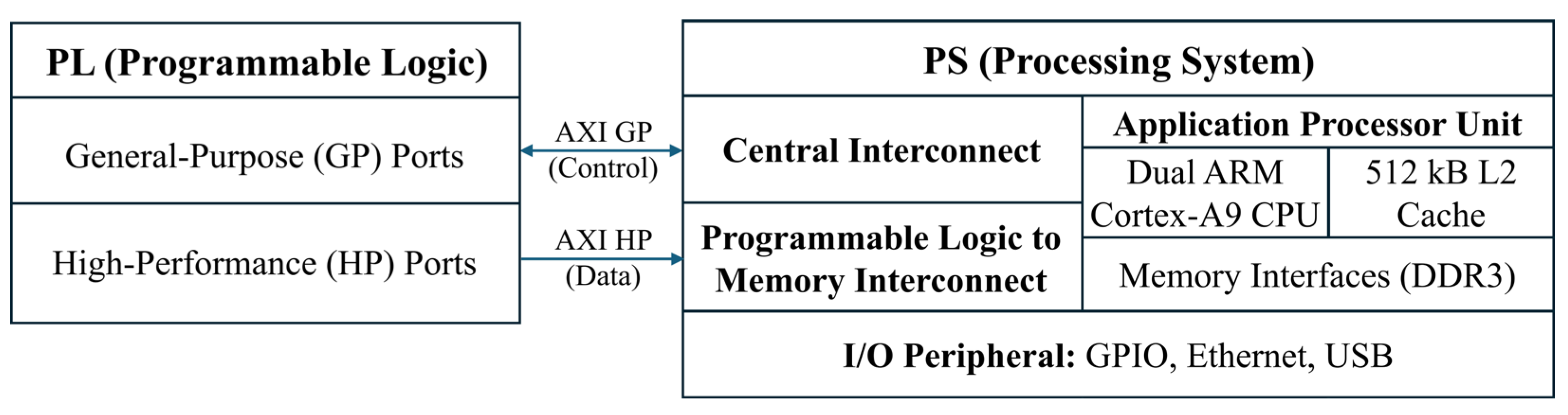

2.3. Digitizer Architecture

2.4. GUI for Calibration and Image Processing

2.5. Module Functions and Data Acquisition Method

3. Experiment Setup

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. A-Scan Signal Quality

4.2. B-Scan and C-Scan Image Reconstruction

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strogen, B.; Bell, K.; Breunig, H.; Zilberman, D. Environmental, public health, and safety assessment of fuel pipelines and other freight transportation modes. Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pootakham, T.; Kumar, A. A comparison of pipeline versus truck transport of bio-oil. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, K.; Jha, A.; Muller, N.; Walsh, R. External costs of transporting petroleum products: Evidence from shipments of crude oil from North Dakota by pipelines and rail. Energy J. 2019, 40, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, L.; Liu, G.; Tian, G.; Ona, D.; Song, Y.; Li, S. Comparative analysis of in-line inspection equipments and technologies. Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 382, 032021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trench, C.J.; Kiefner, J.F. Oil pipeline characteristics and risk factors: Illustrations from the decade of construction. Am. Pet. Inst. 2001, 2–6. Available online: https://www.api.org/-/media/files/oil-and-natural-gas/ppts/other-files/decadefinal.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Guan, L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; An, W.; Noureldin, A. A Review on Small-Diameter Pipeline Inspection Gauge Localization Techniques: Problems, Methods and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Communications, Signal Processing, and Their Applications (ICCSPA), Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 19–21 March 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Qin, L.; Sun, M.; Lin, D.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Z. Influence of excitation parameters on the magnetization of MFL ILI tools for small-diameter pipelines. Magn. Mater. 2025, 616, 172780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, M.; Djukic, M.B.J. External corrosion of oil and gas pipelines: A review of failure mechanisms and predictive preventions. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 100, 104467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Liang, Q.; Wei, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, T. Applicability evaluation technology for steel small diameter pipes containing external surface corrosion defects. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Ma, W.; Pang, G.; Wang, K.; Ren, J.; Nie, H.; Dang, W.; Yao, T. Failure analysis on girth weld cracking of underground tee pipe. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2021, 191, 104371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtadi-Bonab, M.J.M. Effects of different parameters on initiation and propagation of stress corrosion cracks in pipeline steels: A review. Metals 2019, 9, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lv, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, K.; Xu, Z.; Yuan, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Fu, A.; Feng, Y. Sulfide stress corrosion cracking in L360QS pipelines: A comprehensive failure analysis and implications for natural gas transportation safety. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2024, 212, 105324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yang, X.; Cui, L.; Wang, F.; Li, S. Material flow influence on the weld formation and mechanical performance in underwater friction taper plug welds for pipeline steel. Mater. Des. 2015, 88, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Li, R.; Nie, B.; Liu, S.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H. Literature review: Theory and application of in-line inspection technologies for oil and gas pipeline girth weld defection. Sensors 2016, 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Shi, S.; Yan, F.; Huang, Y.; Bao, Y. Experimental study on combined effect of mechanical loads and corrosion using tube-packaged long-gauge fiber Bragg grating sensors. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 22, 3985–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.B.; Tewari, S.; Biswas, S.; Sharma, A. A comprehensive study of techniques utilized for structural health monitoring of oil and gas pipelines. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 23, 1816–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spandonidis, C.; Theodoropoulos, P.; Giannopoulos, F.; Galiatsatos, N.; Petsa, A. Evaluation of deep learning approaches for oil & gas pipeline leak detection using wireless sensor networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 113, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, M.; Földesi, P. A New Extensible Feature Matching Model for Corrosion Defects Based on Consecutive In-Line Inspections and Data Clustering. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-H.; Park, J.-H.; Kim, J.-J.; Yoo, K.; Kim, D.-K.; Jeong, H.-Y. Robust and Unbiased Estimation of Robot Pose and Pipe Diameter for Natural Gas Pipeline Inspection Using 3D Time-of-Flight (ToF) Sensors. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tian, G.; Zeng, Y.; Li, R.; Song, H.; Wang, Z.; Gao, B.; Zeng, K. Pipeline in-line inspection method, instrumentation and data management. Sensors 2021, 21, 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, M.-Q.; Tang, B.; Cui, C.; Xu, X.-F. Dynamic characteristics of the pipeline inspection gauge under girth weld excitation in submarine pipeline. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan Tien, N.; Hui Ryong, Y.; Yong Woo, R.; Sang Bong, K. Speed control of PIG using bypass flow in natural gas pipeline. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE 2001) (Cat. No.01TH8570), Busan, Republic of Korea, 12–16 June 2001; Volume 862, pp. 863–868. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Kim, S.B.; Yoo, H.R.; Rho, Y.W. Modeling and simulation for PIG flow control in natural gas Pipeline. KSME Int. J. 2001, 15, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan Tien, N.; Dong Kyu, K.; Yong Woo, R.; Sang Bong, K. Dynamic modeling and its analysis for PIG flow through curved section in natural gas pipeline. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.01EX515), Banff, AB, Canada, 29 July–1 August 2001; pp. 492–497. [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi, G.; Giunta, G. Acoustic detection and tracking of a pipeline inspection gauge. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 194, 107549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.; El-Borgi, S.; Patil, D.; Song, G. Inspection and monitoring systems subsea pipelines: A review paper. Struct. Health Monit. 2020, 19, 606–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaei, H.; Eslami, A.; Egbewande, A. A review on pipeline corrosion, in-line inspection (ILI), and corrosion growth rate models. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2017, 149, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlak, B.O.; Yavasoglu, H.A. A comprehensive analysis of in-line inspection tools and technologies for steel oil and gas pipelines. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Tian, Z. A review on pipeline integrity management utilizing in-line inspection data. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 92, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wen, M.; Lin, D.; Gao, J.; Qin, L.; Liu, C.; Xu, X.; Lian, Z. Failure analysis of local effusion corrosion in small diameter gas pipeline: Experiment and numerical. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 161, 108300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, K.; Beller, M.; Willems, H.; Barbian, O. A new generation of ultrasonic in-line inspection tools for detecting, sizing and locating metal loss and cracks in transmission pipelines. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, Munich, Germany, 8–11 October 2002; pp. 665–671. [Google Scholar]

- Birchall, M.; Sevciuc, N.; Madureira, C. Internal ultrasonic pipe & tube inspection–IRIS. In Proceedings of the IV Conferencia panamericana de END, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 22–26 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.P.; Tarpara, E.G.; Patankar, V. Experimentation for sag and dimension measurement of thin-walled tubes and pipes using multi-channel ultrasonic imaging system. J. Nondestruct. Evaluation 2021, 40, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.P.; Patankar, V. Battery-powered FPGA-based embedded system for ultrasonic pipe inspection and gauging systems. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2023, 94, 034712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.P.; Patankar, V. Zynq SoC FPGA-based water-immersible ultrasonic instrumentation for pipe inspection and gauging. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 015313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.T.; Nguyen, T.M.T.; Dinh, T.T.N.; Bui, Q.C.; Vo, T.H.; Phan, D.T.; Park, S.; Choi, J.; Kang, Y.-H.; Kim, B.-G.; et al. Design of a Multichannel Pulser/Receiver and Optimized Damping Resistor for High-Frequency Transducer Applied to SAM System. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pulser | Channel | 1 |

| Voltage | 90 V (fixed) | |

| Pulse width | 5–50 ns (5 ns/step) | |

| Rise time | 2 ns | |

| Receiver | Bandwidth | 30 MHz |

| Gain | 53 dB maximum | |

| Low-pass filter | 36 MHz | |

| Digitizer | Resolution | 14 bits |

| Sample rate | 100 MHz | |

| Record length | 512 (at 4.5 kHz) | |

| Trigger delay | 50 us (at 4.5 kHz) | |

| Data Transfer | Speed | 4500 14-bit A-scans per second |

| Module/Processor | Primary Functions | Programming Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| STM32 Microcontroller | Controls trigger pulser and timing. | Firmware development for pulse width control, trigger synchronization, and GPIO timing signals. |

| FPGA—Programmable Logic (PL) | High-speed ADC data capture; deserialization; buffering; hardware-level synchronization. | HDL/Vivado design for ADC interfacing, FIFO management, trigger alignment, and high-speed parallel processing. |

| FPGA—Processing System (PS) | TCP/IP master; data packetization; dual-core task splitting (Core 1: acquisition handling, Core 2: network communication). | C applications for TCP/IP communication, buffer control, and PS–PL interfacing. |

| Raspberry Pi 5 | TCP/IP slave, long-duration data logging to SSD. | C applications for socket communication, storage management. |

| Host PC | Real-time visualization of A/B/C-scan; parameter configuration; pre-inspection calibration, and the data post-processing. | GUI software (C#) for data rendering, peak detection, and configuration interface. |

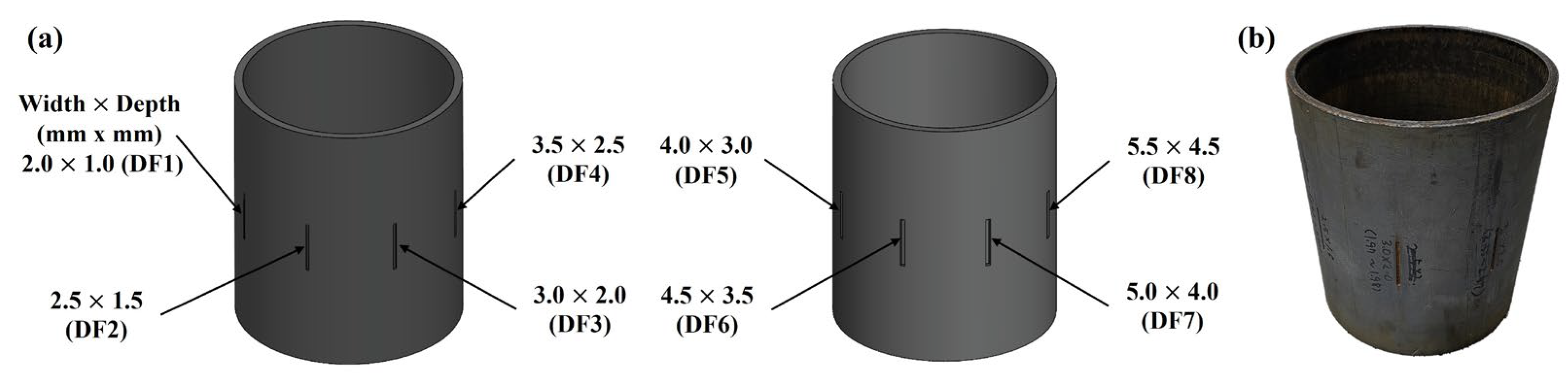

| Defects | Actual Depth (mm) | Measured Depth (mm) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DF1 | 1 | 1.01 | 1.30 |

| DF2 | 1.5 | 1.48 | 1.53 |

| DF3 | 2 | 1.97 | 1.40 |

| DF4 | 2.5 | 2.53 | 1.20 |

| DF5 | 3 | 3.02 | 0.53 |

| DF6 | 3.5 | 3.58 | 2.29 |

| DF7 | 4 | 4.04 | 0.95 |

| DF8 | 4.5 | 4.49 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doan, V.H.M.; Nguyen, T.M.K.; Tran, L.H.; Vu, D.D.; Le, T.D.; Phan, L.K.; Vi, L.T.A.; Nguyen, T.P.; Lim, H.G.; Choi, J.; et al. Development of a Compact Data Acquisition System for Immersive Ultrasonic Inspection of Small-Diameter Pipelines. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12817. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312817

Doan VHM, Nguyen TMK, Tran LH, Vu DD, Le TD, Phan LK, Vi LTA, Nguyen TP, Lim HG, Choi J, et al. Development of a Compact Data Acquisition System for Immersive Ultrasonic Inspection of Small-Diameter Pipelines. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12817. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312817

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoan, Vu Hoang Minh, Tien Minh Khoi Nguyen, Le Hai Tran, Dinh Dat Vu, Thanh Dat Le, Le Khuong Phan, Le The Anh Vi, Thanh Phuoc Nguyen, Hae Gyun Lim, Jaeyeop Choi, and et al. 2025. "Development of a Compact Data Acquisition System for Immersive Ultrasonic Inspection of Small-Diameter Pipelines" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12817. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312817

APA StyleDoan, V. H. M., Nguyen, T. M. K., Tran, L. H., Vu, D. D., Le, T. D., Phan, L. K., Vi, L. T. A., Nguyen, T. P., Lim, H. G., Choi, J., Mondal, S., & Oh, J. (2025). Development of a Compact Data Acquisition System for Immersive Ultrasonic Inspection of Small-Diameter Pipelines. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12817. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312817