Automated Weld Defect Classification Enhanced by Synthetic Data Augmentation in Industrial Ultrasonic Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

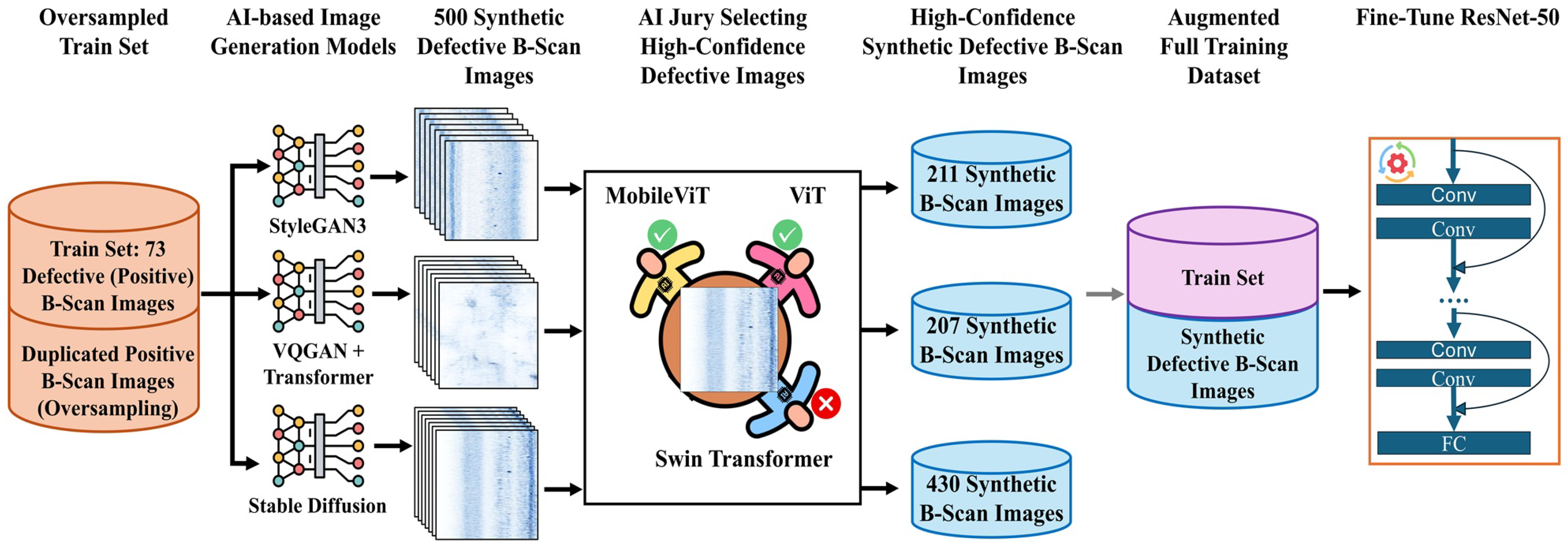

- State-of-the-art generative models, including StyleGAN3, VQGAN with an unconditional transformer, and Stable Diffusion, are fine-tuned to synthesize realistic B-scan images of LOF defects under limited data conditions.

- High-confidence synthetic defect images are selected through a filtering process using fine-tuned Transformer-based classifiers.

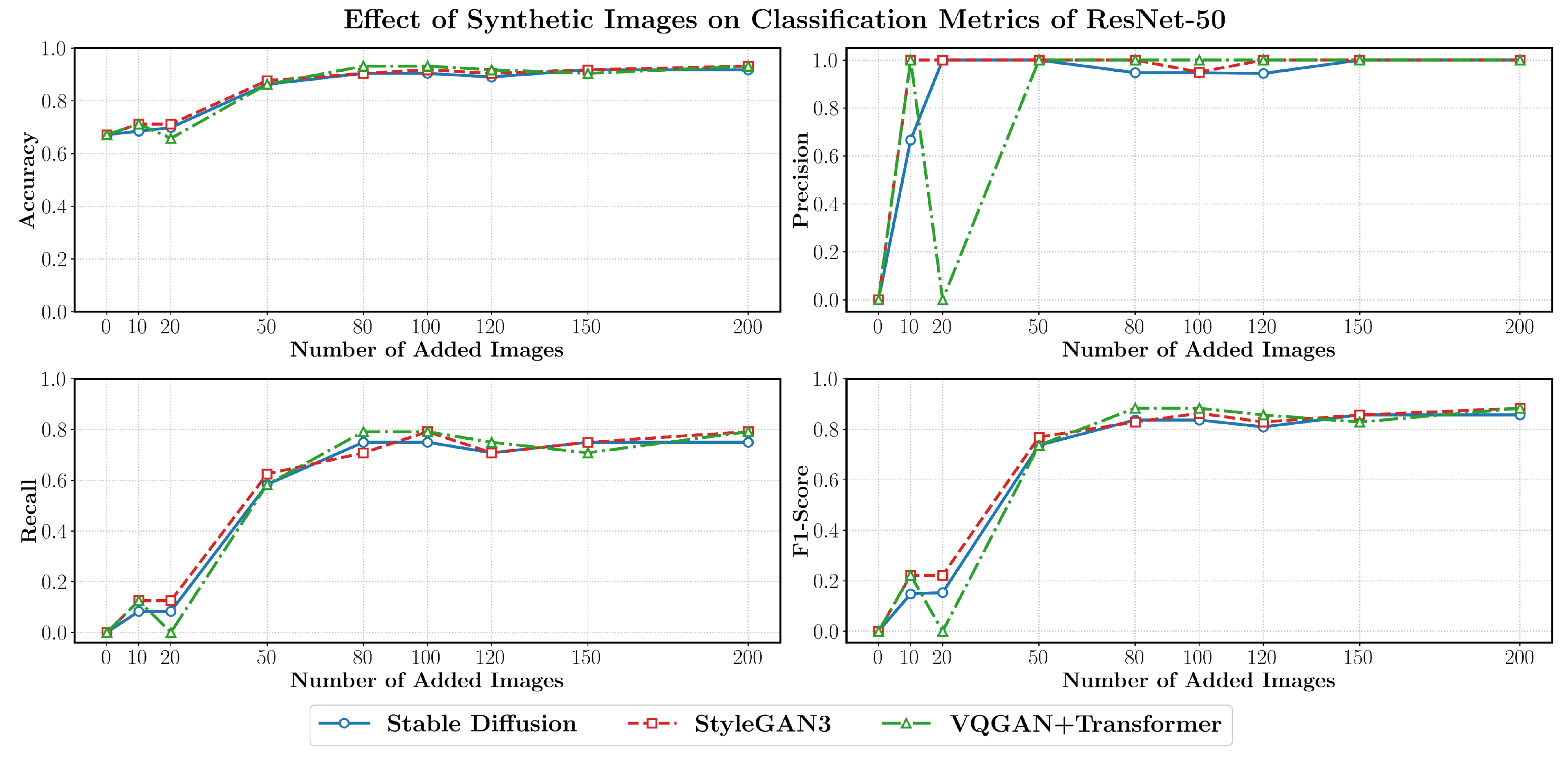

- The impact of synthetic augmentation on ResNet-50 is demonstrated, showing substantial performance improvement where the baseline model fails.

- A comparison between synthetic augmentation and knowledge distillation is provided, demonstrating that synthetic data yields greater performance gains for this task.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lack of Fusion (LOF) Detection via Ultrasonic B-Scan

2.2. Synthetic Image Generation

2.2.1. StyleGAN3

2.2.2. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs)

2.2.3. VQGAN with an Unconditional Transformer

2.3. Deep Learning Architectures for Image Classification

2.3.1. ResNet-50

2.3.2. Vision Transformers

2.4. Knowledge Distillation

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

3. Experimental Setup

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Experiments Implementation Details

3.2.1. Fine-Tuning Procedures for Synthetic Image Generation Models

- VQGAN With An Unconditional Transformer: For the VQGAN with an unconditional transformer model, the instructions and default configurations from the main repository (https://github.com/CompVis/taming-transformers, accessed on 10 May 2025) are followed. This involves a two-stage fine-tuning process. First, the VQGAN model is fine-tuned on the positive B-scan images for 30 epochs using pre-trained ImageNet weights, with a batch size of 8. The model with the lowest validation loss, which occurred at epoch 24, is selected. Subsequently, an unconditional transformer model, architecturally similar to GPT-2 [33] and configured with the following parameters: vocab_size of 1024, block_size of 512, 24 layers, 16 heads, and an embedding size of 1024, is trained for 20 epochs with a batch size of 32. The best-performing model (based on validation loss), selected from epoch 16, is used for subsequent analysis.

- StyleGAN3: The StyleGAN3 model is fine-tuned using the stylegan3-transform configuration and the checkpoint (stylegan3-t-ffhqu-256x256.pkl) pre-trained on the FFHQ-U 256 × 256 dataset, adhering to the default settings provided in the official repository (https://github.com/NVlabs/stylegan3, accessed on 17 May 2025). Training is carried out for 100,000 iterations with a batch size of 32.

- Stable Diffusion: The fine-tuning procedure for Stable Diffusion follows the guidelines outlined in the open-source repository (https://github.com/kohya-ss/sd-scripts, accessed on 3 May 2025). The sd-v1-5-pruned-noema-fp16 checkpoint (https://huggingface.co/hollowstrawberry/stable-diffusion-guide/blob/main/models/sd-v1-5-pruned-noema-fp16.safetensors, accessed on 3 May 2025) is used as the base model for fine-tuning on the positive B-scan images. DreamBooth fine-tuning, a technique designed to teach a new concept to a diffusion model with fewer iterations and without overwriting its extensive prior knowledge, is applied. For this purpose, 200 regularization images generated using the prompt “background defected” are placed alongside the positive images from the dataset’s training set, which are associated with the prompt “skt background defected” (where “skt” serves as a token identifier without semantic meaning). A parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) approach, specifically LoRA (LoRA-c3Lier), is employed following the configuration of an extended LoRA variant that adapts both linear layers and convolutional layers. In this setup, LoRA adapters are applied to the linear and 1 × 1 convolution projection layers with a rank (network_dim) of 32 and an alpha value of 16. In addition, 3 × 3 convolution layers are also adapted using convolutional LoRA components configured with rank (conv_dim) 4 and alpha 1. Training is conducted for 25 epochs with a learning rate set to and a batch size of 256. Figure 4 presents positive sample B-scan images from the training set alongside images generated by each different method.

3.2.2. Fine-Tuning Procedures for Image Classification Models

4. Results and Discussion

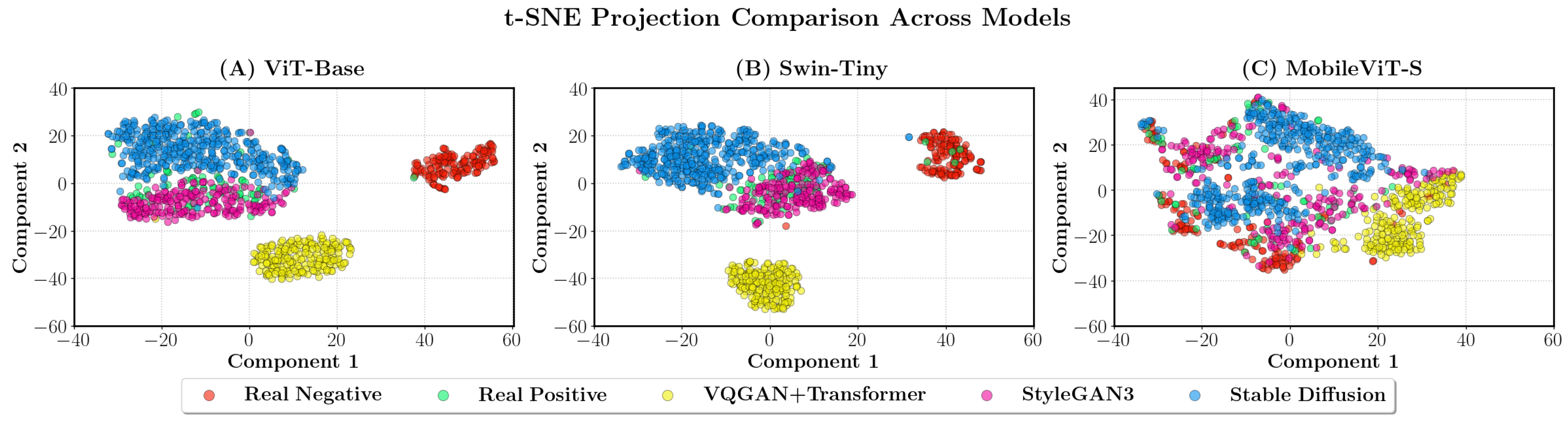

4.1. Qualitative and Feature-Space Analysis of Synthetic Images

4.2. ResNet-50 Baseline Performance vs. Transformer-Based Models

4.3. Improving ResNet-50 for LOF Defect Classification Through Synthetic Data

4.4. Synthetic Data vs. Knowledge Distillation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adegboye, M.A.; Fung, W.-K.; Karnik, A. Recent Advances in Pipeline Monitoring and Oil Leakage Detection Technologies: Principles and Approaches. Sensors 2019, 19, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmi, C.; Zapata, J.; Elferchichi, S.; Laabidi, K. Advanced Faster-RCNN Model for Automated Recognition and Detection of Weld Defects on Limited X-Ray Image Dataset. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2024, 43, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddaf-Sh, M.M.; Naddaf-Sh, S.; Zargarzadeh, H.; Zahiri, S.M.; Dalton, M.; Elpers, G.; Kashani, A.R. 9—Defect Detection and Classification in Welding Using Deep Learning and Digital Radiography. In Fault Diagnosis and Prognosis Techniques for Complex Engineering Systems; Karimi, H., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 327–352. [Google Scholar]

- Naddaf-Sh, S.; Naddaf-Sh, M.M.; Zargarzadeh, H.; Dalton, M.; Ramezani, S.; Elpers, G.; Baburao, V.S.; Kashani, A.R. Real-Time Explainable Multiclass Object Detection for Quality Assessment in 2-Dimensional Radiography Images. Complexity 2022, 2022, 4637939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medak, D.; Posilović, L.; Subašić, M.; Budimir, M.; Lončarić, S. Automated Defect Detection from Ultrasonic Images Using Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2021, 68, 3126–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Ito, S.; Toyama, N. Computerized Ultrasonic Imaging Inspection: From Shallow to Deep Learning. Sensors 2018, 18, 3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, S.K.; Vishwakarma, M.; Soni, A. Advances and Researches on Non Destructive Testing: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 3690–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swornowski, P.J. Scanning of the Internal Structure Part with Laser Ultrasonic in Aviation Industry. Scanning 2011, 33, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.L.; Zhang, J.; Gambaruto, A.M.; Wilcox, P.D. A Framework for Computing Directivities for Ultrasonic Sources in Generally Anisotropic, Multi-Layered Media. Wave Motion 2024, 128, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvano, G.; Agostino, A.; De Magistris, G.; Graziano, A.; Veneri, G. Controllable Image Synthesis of Industrial Data Using Stable Diffusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 5354–5363. [Google Scholar]

- Capogrosso, L.; Girella, F.; Taioli, F.; Dalla Chiara, M.; Aqeel, M.; Fummi, F.; Setti, F.; Cristani, M. Diffusion-Based Image Generation for In-Distribution Data Augmentation in Surface Defect Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.00501. [Google Scholar]

- Girella, F.; Liu, Z.; Fummi, F.; Setti, F.; Cristani, M.; Capogrosso, L. Leveraging Latent Diffusion Models for Training-Free In-Distribution Data Augmentation for Surface Defect Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Content-Based Multimedia Indexing (CBMI), Reims, France, 4–6 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Virkkunen, I.; Koskinen, T.; Jessen-Juhler, O.; Rinta-Aho, J. Augmented Ultrasonic Data for Machine Learning. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2021, 40, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posilović, L.; Medak, D.; Subašić, M.; Budimir, M.; Lončarić, S. Generative Adversarial Network with Object Detector Discriminator for Enhanced Defect Detection on Ultrasonic B-Scans. Neurocomputing 2021, 459, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Tian, K.; Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Yang, K.; Luo, L.; Gao, X.; Peng, J. DiffUT: Diffusion-Based Augmentation for Limited Ultrasonic Testing Defects in High-Speed Rail. NDT E Int. 2025, 154, 103388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddaf-Sh, A.M.; Baburao, V.S.; Zargarzadeh, H. Automated Weld Defect Detection in Industrial Ultrasonic B-Scan Images Using Deep Learning. NDT 2024, 2, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddaf-Sh, A.M.; Baburao, V.S.; Zargarzadeh, H. Leveraging Segment Anything Model (SAM) for Weld Defect Detection in Industrial Ultrasonic B-Scan Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krautkrämer, J.; Krautkrämer, H. Ultrasonic Testing of Materials; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Laine, S.; Härkönen, E.; Hellsten, J.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Alias-Free Generative Adversarial Networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 852–863. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, N.; Li, Y.; Jampani, V.; Pritch, Y.; Rubinstein, M.; Aberman, K. DreamBooth: Fine Tuning Text-to-Image Diffusion Models for Subject-Driven Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 22500–22510. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2022, Online, 25–29 April 2022; Volume 1, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, P.; Rombach, R.; Ommer, B. Taming Transformers for High-Resolution Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 12873–12883. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16×16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. MobileViT: Light-Weight, General-Purpose, and Mobile-Friendly Vision Transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.02178. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, G.; Kaleem, S.M.; Rouf, T.; Lall, B. A Comprehensive Review of Knowledge Distillation in Computer Vision. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.00936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddaf Shargh, A. Deep Learning Methods for Defect Analysis in Industrial Ultrasonic Images. Ph.D. Thesis, Lamar University, Beaumont, TX, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/2f717dbb11a339f3c9747c35937880cc/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 31 October 2025).

| Type of Image | Train | Validation | Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 155 | 39 | 49 |

| Positive | 73 | 19 | 24 |

| Total | 228 | 58 | 73 |

| Model | Params | AUC | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 | 25.6 M | 0.500 | 0.671 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ViT-Base | 86.6 M | 0.886 | 0.904 | 0.870 | 0.833 |

| Swin-Tiny | 28.3 M | 0.866 | 0.877 | 0.800 | 0.833 |

| MobileViT-S | 5.6 M | 0.969 | 0.918 | 0.875 | 0.875 |

| Method | # Images | AUC | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VQGAN + Transformer | 80 | 0.896 | 0.932 | 1.000 | 0.792 | 0.884 |

| StyleGAN3 | 200 | 0.896 | 0.932 | 1.000 | 0.792 | 0.884 |

| Stable Diffusion | 150 | 0.875 | 0.918 | 1.000 | 0.750 | 0.857 |

| Model | ViT-Base | Swin-Tiny | MobileViT-S | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPD | CHA | MPD | CHA | MPD | CHA | |

| VQGAN + Transformer | 9.95 | 569.53 | 8.42 | 266.25 | 15.49 | 905.52 |

| Stable Diffusion | 12.32 | 862.94 | 10.59 | 495.74 | 17.89 | 1307.95 |

| StyleGAN3 | 13.60 | 488.90 | 11.07 | 536.71 | 24.82 | 2074.90 |

| Teacher | AUC | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ViT-Base | 0.856 | 0.836 | 0.688 | 0.917 | 0.786 |

| Swin-Tiny | 0.854 | 0.904 | 1.000 | 0.708 | 0.829 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naddaf-Sh, A.-M.; Baburao, V.S.; Ben-Miled, Z.; Zargarzadeh, H. Automated Weld Defect Classification Enhanced by Synthetic Data Augmentation in Industrial Ultrasonic Images. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12811. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312811

Naddaf-Sh A-M, Baburao VS, Ben-Miled Z, Zargarzadeh H. Automated Weld Defect Classification Enhanced by Synthetic Data Augmentation in Industrial Ultrasonic Images. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12811. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312811

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaddaf-Sh, Amir-M., Vinay S. Baburao, Zina Ben-Miled, and Hassan Zargarzadeh. 2025. "Automated Weld Defect Classification Enhanced by Synthetic Data Augmentation in Industrial Ultrasonic Images" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12811. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312811

APA StyleNaddaf-Sh, A.-M., Baburao, V. S., Ben-Miled, Z., & Zargarzadeh, H. (2025). Automated Weld Defect Classification Enhanced by Synthetic Data Augmentation in Industrial Ultrasonic Images. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12811. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312811