The Influence of Hitting Locations on Shot Outcomes in Professional Men’s Padel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Into-Play Shots Comparisons Between Hitting Locations

3.2. Winner Shots Comparisons Between Hitting Locations

3.3. Forced-Errors Shots Comparisons Between Hitting Locations

3.4. Unforced-Errors Shots Comparisons Between Hitting Locations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Courel Ibáñez, J.; Javier Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez, B.; García Benítez, S.; Echegaray, M. Evolution of Padel in Spain According to Practitioners’ Gender and Age. Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2017, 12, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, J.B. Historia del pádel. In Materiales para la Historia del Deporte; No 11; Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez, B.J.; Cañas, J. Game performance and length of rally in professional padel players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 55, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courel-Ibanez, J.; Sánchez-Alcaraz Martinez, B.J.; Muñoz Marín, D. Exploring Game Dynamics in Padel: Implications for Assessment and Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1971–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellado-Arbelo, O.; Baiget, E. Activity profile and physiological demand of padel match play: A systematic review. Kinesiology 2022, 54, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priego, J.I.; Melis, J.O.; Llana-Belloch, S.; Pérezsoriano, P.; García, J.C.G.; Almenara, M.S. Padel: A Quantitative study of the shots and movements in the high-performance. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2013, 8, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampuero, R.; Mellado-Arbelo, O.; Fuentes-García, J.P.; Baiget, E. Game sides technical-tactical differences between professional male padel players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 19, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Muñoz, D.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Sequential Mapping of Game Patterns in Men and Women Professional Padel Players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2024, 19, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J. Game patterns in padel: A sequential analysis of elite men players. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2021, 21, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Vaquer Castillo, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Ramón-Llin, J.; Muñoz, D. Analysis of the return in professional men’s and women’s padel. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 19, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, B.J.S.A.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Muñoz, D.; Infantes-Córdoba, P.; de Zumarán, F.S.; Sánchez-Pay, A. Analysis of attacking actions in professional men’s padel. Apunts. Educ. Fis. Deportes 2020, 142, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado-Arbelo, Ó.; Baiget Vidal, E.; Usón, M.V. Analysis of Game Actions in Professional Male Padel. 2019. Available online: https://repositorio.ucam.edu/handle/10952/6023?locale-attribute=en (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Amieba, C.; Salinero, J.J. Overview of paddle competition and its physiological demands. AGON Int. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 3, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.D.; Pérez, F.J.G.; Gil, M.C.R.; Mariño, M.M.; Marín, D.M. Estudio de la carga interna en pádel amateur mediante la frecuencia cardíaca. Instituto Nacional de Educacion Fisica de Cataluna. Apunts. Educ. Física Deportes 2017, 127, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Quintero, M. Análisis de los Parámetros de Carga Externa e Interna en Pádel. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326689807 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Castillo-Rodríguez, A.; Alvero-Cruz, J.R.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; Fernández-García, J.C. Physical and physiological responses in Paddle Tennis competition. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2014, 14, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeco, A.; de Sire, A.; Marotta, N.; Spanò, R.; Lippi, L.; Palumbo, A.; Iona, T.; Gramigna, V.; Palermi, S.; Leigheb, M.; et al. Match Analysis, Physical Training, Risk of Injury and Rehabilitation in Padel: Overview of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Giménez, A.; Pradas de la Fuente, F.; Castellar Otín, C.; Carrasco Páez, L. Performance Outcome Measures in Padel: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Álvarez, C.; Colomar, J.; Baiget, E.; Villafaina, S.; Fuentes-García, J.P. Effects of 4 Weeks of Variability of Practice Training in Padel Double Right Wall: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mot. Control 2022, 26, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Miguel, I.; Muñoz Marín, D.; Javier Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.; Piedra Blesa, D.; Barriocanal, I.; Sánchez Pay, A. Análisis de los golpes ganadores y errores en pádel profesional. Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte 2022, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A.N.; Lupo, C.; Contardo, M.; Brustio, P.R. Decoding the decade: Analyzing the evolution of technical and tactical performance in elite padel tennis (2011–2021). Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 19, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cádiz Gallardo, M.P.; Pradas de la Fuente, F.; Moreno-Azze, A.; Carrasco Páez, L. Physiological demands of racket sports: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1149295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.; Reid, M.; Beale, C.; Girard, O. A Comparison of Match Load Between Padel and Singles and Doubles Tennis. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2023, 18, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Llin, J.; Guzmán, J.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Stroke analysis in padel according to match outcome and game side on court. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Cañas, J. Effectiveness at the net as a predictor of final match outcome in professional padel players. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2015, 15, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Escudero-Tena, A. Analysis and prediction of unforced errors in men’s and women’s professional padel. Biol. Sport 2024, 41, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudero-tena, A.; Fernández-cortes, J.; García-rubio, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Use and efficacy of the lob to achieve the offensive position in women’s professional padel. Analysis of the 2018 wpt finals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon-Llin, J.; Sanchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Sanchez-Pay, A.; Guzman, J.F.; Vuckovic, G.; Martínez-Gallego, R. Exploring offensive players’ collective movements and positioning dynamics in high-performance padel matches using tracking technology. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2021, 21, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Gómez-Ruano, M.Á.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Muñoz, D. Importance of Maintaining Net Position in Men’s and Women’s Professional Padel. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2023, 130, 2210–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Jiménez, V.; Muñoz, D.; Ramón-Llin, J. Effectiveness and distribution of attack strokes to finish the point in professional padel. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Fis. Deporte 2022, 22, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Martín-Miguel, I.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á.; Llanos-García, M.B.; García-Sánchez, J.M.; Escudero-Tena, A. Bridging the gap: A sex-based examination of shot types and effectiveness in professional padel. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2025, 20, 2540–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; García-Rubio, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Analysis of Errors and Winners in Men’s and Women’s Professional Padel. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguel, I.; Almonacid, B.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Game Dynamics in Professional Padel: Shots Per Point, Point Pace and Technical Actions. Sports 2024, 12, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sampieri, R. Metodología de la Investigación. 2014. Available online: https://apiperiodico.jalisco.gob.mx/api/sites/periodicooficial.jalisco.gob.mx/files/metodologia_de_la_investigacion_-_roberto_hernandez_sampieri.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Soto, A.; Camerino, O.; Iglesias, X.; Anguera, M.T.; Castañer, M. LINCE PLUS: Research Software for Behavior Video Analysis. Apunt. Educ. Física Esports 2019, 137, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol. Bull. 1968, 70, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Perez-Puche, D.T.; Pradas, F.; Ramón-Llín, J.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Muñoz, D. Analysis of performance parameters of the smash in male and female professional padel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CRITERIA | CATEGORIES | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| FH | Forehand | |

| BH | Backhand | |

| VL | Volley | |

| Type of | TR | Tray |

| Shot | LO | Lob |

| SM | Smash | |

| FS | Fake smash | |

| Shot | IP | Into play |

| outcome | W | Winner |

| UNF | Unforced error | |

| FE | Forced error | |

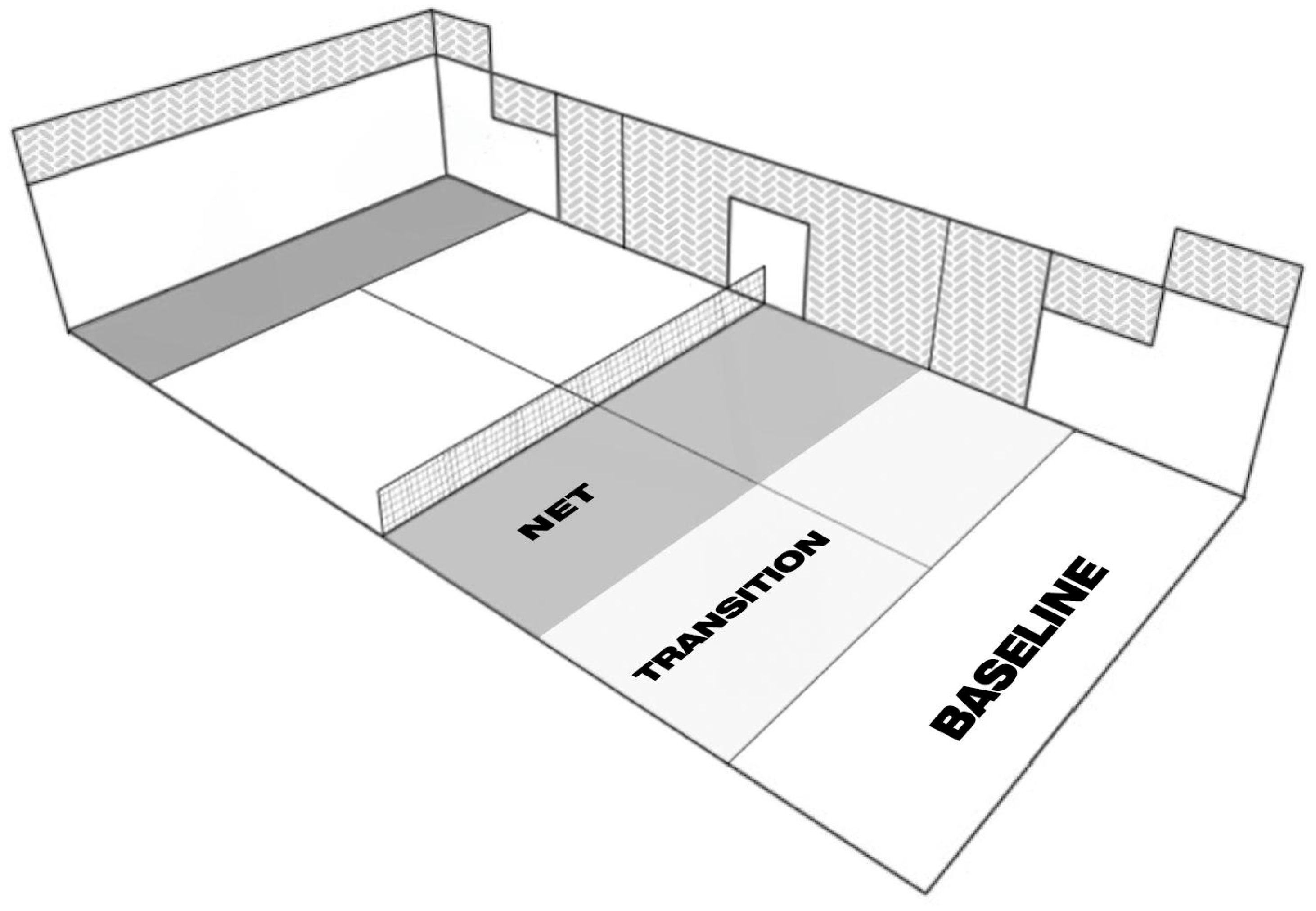

| Hitting | BL | Baseline |

| zone | TRA | Transition |

| N | Net |

| Baseline | Transition | Net | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of stroke | IP | W | FE | UNF | IP | W | FE | UNF | IP | W | FE | UNF | ||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Forehand | 568 | 5.5 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 0.1 | 29 | 0.3 | 230 | 2.2 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0.1 | 12 | 0.1 | 126 | 1.2 | 7 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.1 | 3 | 0 |

| Backhand | 591 | 5.7 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 32 | 0.3 | 193 | 1.9 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.1 | 89 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.1 | 3 | 0 |

| Volleys | 36 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 321 | 3.1 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 0.1 | 19 | 0.2 | 2569 | 25 | 144 | 1.4 | 52 | 0.5 | 116 | 1.1 |

| Trays | 510 | 4.9 | 6 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 23 | 0.2 | 1117 | 10.8 | 21 | 0.2 | 1 | 0 | 35 | 0.3 | 27 | 0.3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lobs | 1962 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 0.1 | 62 | 0.6 | 513 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 0.2 | 162 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Smash | 9 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 169 | 1.6 | 127 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0.2 | 45 | 0.4 | 139 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Fake smash | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 59 | 0.6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0.1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Variable | IP-BL Median (IQR) | IP-TRA Median (IQR) | IP-N Median (IQR) | Within Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Contrast | Pairwise Comparison | ||||

| Forehand | 78 (55) | 32.50 (19.75) | 16.50 (9.25) | <0.001 | 16 | IP-N < IP-BL = <0.001 (r = 0.71) |

| Backhand | 74.50 (51.50) | 21 (20.75) | 11.50 (10.50) | <0.001 | 15.55 | IP-N < IP-BL = <0.001 (r = 0.68) |

| Volley | 4.50 (2.50) | 38.50 (24.75) | 295.50 (189.25) | <0.001 | 16 | IP-BL < IP-N = <0.001 (r = 0.71) |

| Tray | 64.50 (60.50) | 172 (144.25) | 4 (4.25) | <0.001 | 16 | IP-N < IP-TRA = <0.001 (r = 0.71) |

| Lob | 262 (228.25) | 77 (62.50) | 23.50 (19.25) | <0.001 | 16 | IP-N < IP-BL = <0.001 (r = 0.71) |

| Smash | 1 (1.75) | 19.50 (11.25) | 5 (2.50) | <0.001 | 16 | IP-BL < IP-TRA = <0.001 (r = 0.71) |

| Fake smash | 0 (0.75) | 6.50 (8.75) | 1 (2.75) | 0.001 | 13.86 | IP-BL < IP-TRA = 0.002 (r = 0.60) IP-N < IP-TRA = 0.026 (r = 0.46) |

| Variable | W-BL Median (IQR) | W-TRA Median (IQR) | W-N Median (IQR) | Within Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Contrast | Pairwise Comparison | ||||

| Forehand | 0 (0.75) | 0 (0.75) | 1 (1.00) | 0.440 | 1.62 | - |

| Backhand | 0 (0.75) | 0 (0.75) | 0.50 (1.00) | 0.305 | 2.37 | - |

| Volley | 0 (0) | 0 (1.75) | 17.50 (7.00) | 0.001 | 14.89 | W-BL < W-N = 0.002 (r = 0.60) W-TRA < W-N = 0.026 (r = 0.46) |

| Tray | 0 (1.50) | 2.50 (2.50) | 0 (1.00) | 0.002 | 12.78 | W-BL < W-TRA = 0.026 (r = 0.46) W-N < W-TRA = 0.026 (r = 0.46) |

| Lob | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.368 | 2 | - |

| Smash | 1 (1.50) | 15 (15.00) | 17 (11.25) | 0.002 | 12 | W-BL < W-TRA = 0.008 (r = 0.53) W-BL < W-N = 0.008 (r = 0.53) |

| Fake smash | 0 (0) | 0 (0.75) | 0 (0.75) | 0.264 | 2.67 | - |

| Variable | FE-BL Median (IQR) | FE-TRA Median (IQR) | FE-N Median (IQR) | Within Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Contrast | Pairwise Comparison | ||||

| Forehand | 2 (1.75) | 1 (1.00) | 1 (2.00) | 0.130 | 4 | - |

| Backhand | 0.50 (1.00) | 1 (0.75) | 0.50 (1.00) | 0.589 | 1.06 | - |

| Volley | 0 (0) | 0.50 (2.75) | 6.50 (3.75) | 0.001 | 14.86 | FE-BL < FE-N = 0.001 (r = 0.62) FE-TRA < FE-N = 0.037 (r = 0.44) |

| Tray | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.607 | 1 | - |

| Lob | 1.50 (1.75) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.75) | 0.032 | 6.91 | FE-BL < FE-TRA = 0.046 (r = 0.28) |

| Smash | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 | - |

| Fake smash | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 | - |

| Variable | UNF-BL Median (IQR) | UNF-TRA Median (IQR) | UNF-N Median (IQR) | Within Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Contrast | Pairwise Comparison | ||||

| Forehand | 4 (3.25) | 1 (1.00) | 0 (1.00) | 0.002 | 12.29 | UNF-N < UNF-BL = 0.003 (r = 0.57) |

| Backhand | 4 (1.75) | 0.50 (2.75) | 0 (0.75) | 0.001 | 13.86 | UNF-TRA < UNF-BL = 0.026 (r = 0.46) UNF-N < UNF-BL = 0.002 (r = 0.60) |

| Volley | 0 (0) | 2 (1.00) | 14 (8.00) | 0.001 | 16 | UNF-BL < UNF-N = < 0.001(r = 0.71) |

| Tray | 3 (3.00) | 3.50 (5.50) | 0 (0) | 0.002 | 12.50 | UNF-N < UNF-BL = 0.037 (r = 0.44) UNF-N < UNF-TRA = 0.005 (r = 0.55) |

| Lob | 7 (5.00) | 2 (2.50) | 0 (1.00) | 0.002 | 12.62 | UNF-N < UNF-BL = 0.002 (r = 0.60) |

| Smash | 0 (1.00) | 2 (0.75) | 0 (1.00) | 0.005 | 10.57 | UNF-BL < UNF-TRA = 0.018 (r = 0.49) UNF-N < UNF-TRA = 0.037 (r = 0.44) |

| Fake smash | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.75) | 0.223 | 3 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ampuero, R.; Fuentes-García, J.P.; Baiget, E. The Influence of Hitting Locations on Shot Outcomes in Professional Men’s Padel. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12806. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312806

Ampuero R, Fuentes-García JP, Baiget E. The Influence of Hitting Locations on Shot Outcomes in Professional Men’s Padel. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12806. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312806

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmpuero, Rodrigo, Juan Pedro Fuentes-García, and Ernest Baiget. 2025. "The Influence of Hitting Locations on Shot Outcomes in Professional Men’s Padel" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12806. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312806

APA StyleAmpuero, R., Fuentes-García, J. P., & Baiget, E. (2025). The Influence of Hitting Locations on Shot Outcomes in Professional Men’s Padel. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12806. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312806