Integration and Innovation in Digital Implantology–Part II: Emerging Technologies and Converging Workflows: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Narrative Synthesis Structure

3. Technologies That Disrupt and Deepen Integration

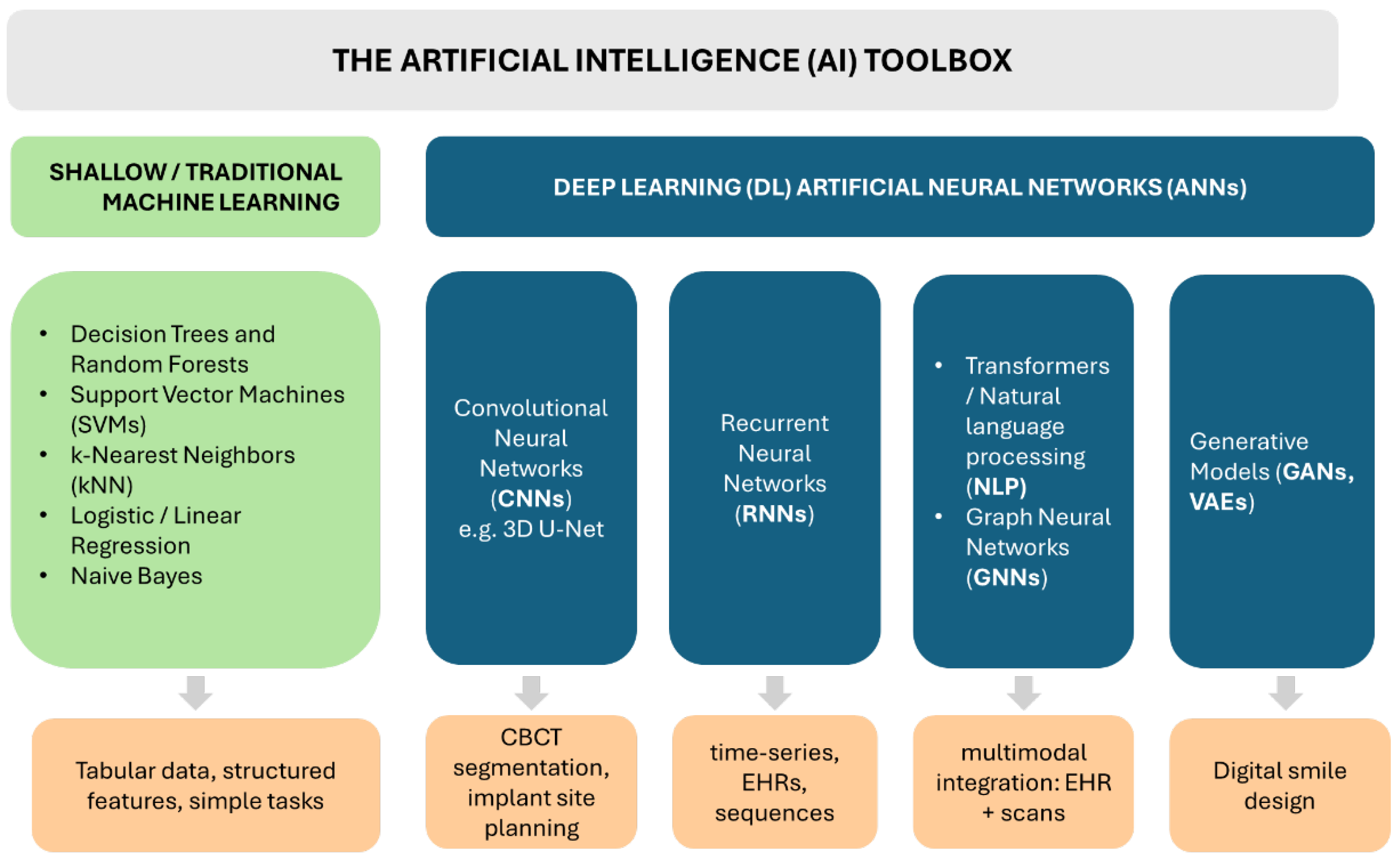

3.1. The Artificial Intelligence Toolkit–Types of AI Models and Their General Capabilities

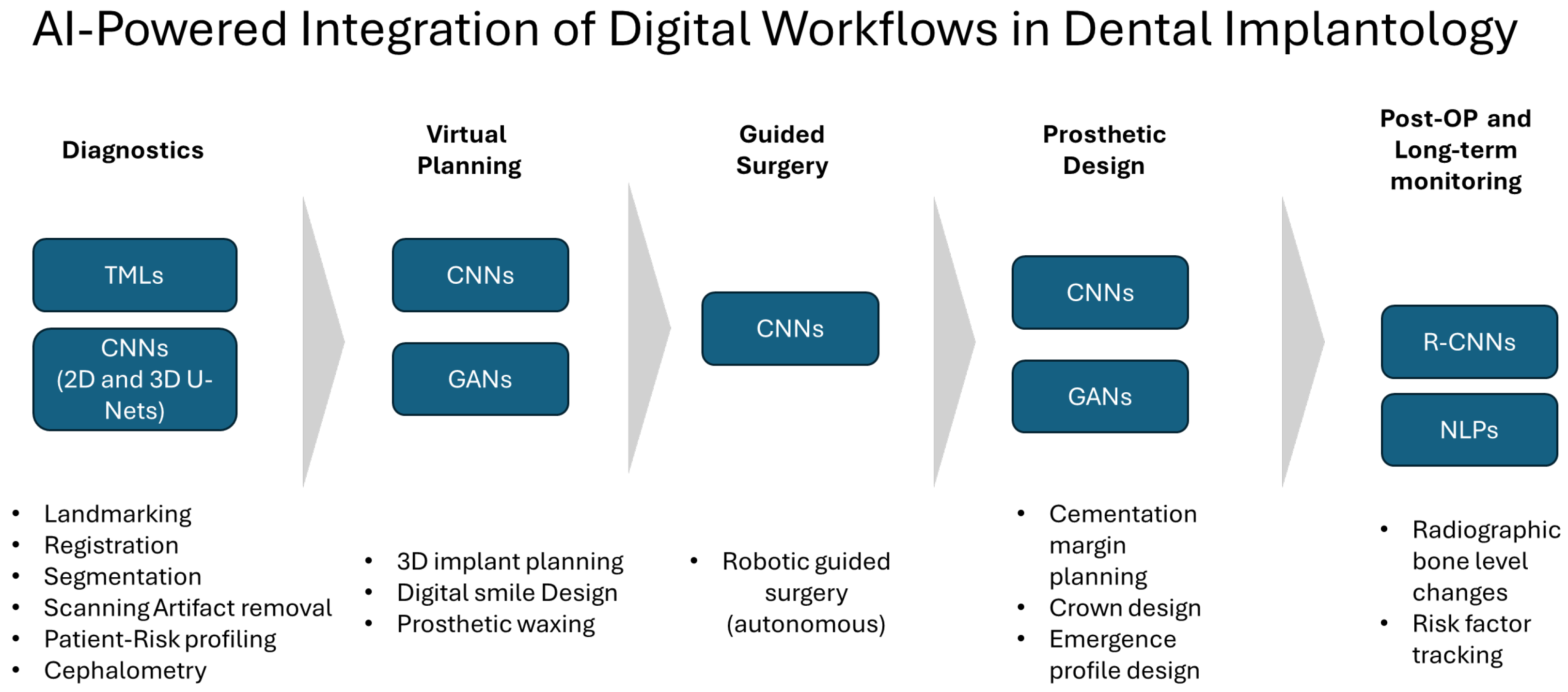

3.2. AI-Powered Integration of Digital Workflows in Dental Implantology

3.2.1. AI in Patient Virtual Model Building, Dataset Registration, and Segmentation

3.2.2. Implant Planning

3.2.3. Prosthetic Design

3.2.4. Digital Smile Design

3.2.5. Robotics and Smart Surgery

| Robotic System | Manufacturer | Level of Autonomy | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yomi [126,131] | Neocis Inc. (USA) | Surgeon-guided (passive) | FDA 510(k) cleared (2017, expanded indications 2020–2023) |

| Dcarer [126] | Dcarer Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China | Surgeon-guided (passive) | NMPA-approved (China) |

| Remebot [132] | Baihui Weikang Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China | Collaborative (semi-active) | NMPA-approved since 2021 (China) |

| Theta [126] | Hangzhou Jianjia robot Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China | Collaborative (semi-active) | NMPA-approved (China) |

| Cobot [126] | Langyue dental surgery robot, Shecheng Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China | Collaborative (semi-active) | NMPA-approved (China) |

| YekeBot [126] | Yakebot Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China | Fully autonomous claimed (active robot) | NMPA-approved (China) |

3.2.6. Implant Maintenance

4. Conclusions

4.1. Current State of AI and Robotics in Digital Implantology

4.2. Practical Implications for Clinicians

4.3. Future Outlook and Emerging Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| kNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| CAIS | Computer-Assisted Implant Surgery |

| S-CAIS | Static Computer-Assisted Implant Surgery |

| D-CAIS | Dynamic Computer-Assisted Implant Surgery |

| R-CAIS | Robot-Assisted Computer-Assisted Implant Surgery |

| FH | Freehand (implant placement) |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CAM | Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| IOS | Intraoral Scanner/Intraoral Scan |

| DSD | Digital Smile Design |

| VA | Virtual Articulator |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| HD95 | 95th Percentile Hausdorff Distance |

| U-Net | Convolutional Neural Network Architecture for Segmentation |

| DCNN | Deep Convolutional Neural Network |

| R-CNN | Region-based Convolutional Neural Network |

| OPG | Orthopantomogram (panoramic radiograph) |

| YOLO | “You Only Look Once” Object Detection Model |

| SaaS | Software-as-a-Service |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| NMPA | National Medical Products Administration (China) |

| CE | Conformité Européenne (CE-mark) |

References

- Joda, T.; Zarone, F.; Ferrari, M. The Complete Digital Workflow in Fixed Prosthodontics: A Systematic Review. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, B.; Yu, J.; Lu, J.; Yan, Z. Comparisons between Digital-Guided and Non-Digital Protocol in Implant Planning, Placement, and Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2023, 23, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolozzi, P.; Michelini, F.; Crottaz, C.; Perez, A. Computer-Aided Design and Computer-Aided Modeling (CAD/CAM) for Guiding Dental Implant Surgery: Personal Reflection Based on 10 Years of Real-Life Experience. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romandini, M.; Ruales-Carrera, E.; Sadilina, S.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Sanz, M. Minimal Invasiveness at Dental Implant Placement: A Systematic Review with Meta-analyses on Flapless Fully Guided Surgery. Periodontology 2000 2023, 91, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raico Gallardo, Y.N.; Da Silva-Olivio, I.R.T.; Mukai, E.; Morimoto, S.; Sesma, N.; Cordaro, L. Accuracy Comparison of Guided Surgery for Dental Implants According to the Tissue of Support: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2017, 28, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, A.; Lombardi, T. Integration and Innovation in Digital Implantology—Part I: Capabilities and Limitations of Contemporary Workflows: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmaseb, A.; Wu, V.; Wismeijer, D.; Coucke, W.; Evans, C. The Accuracy of Static Computer-Aided Implant Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Marquardt, P.; Zwahlen, M.; Jung, R.E. A Systematic Review on the Accuracy and the Clinical Outcome of Computer-Guided Template-Based Implant Dentistry. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercruyssen, M.; Laleman, I.; Jacobs, R.; Quirynen, M. Computer-supported Implant Planning and Guided Surgery: A Narrative Review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkenke, E.; Eitner, S.; Radespiel-Tröger, M.; Vairaktaris, E.; Neukam, F.W.; Fenner, M. Patient-centred Outcomes Comparing Transmucosal Implant Placement with an Open Approach in the Maxilla: A Prospective, Non-randomized Pilot Study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2007, 18, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, T.; Bosson, J.L.; Isidori, M.; Blanchet, E. Effect of Flapless Surgery on Pain Experienced in Implant Placement Using an Image-Guided System. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2006, 21, 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gargallo-Albiol, J.; Barootchi, S.; Salomó-Coll, O.; Wang, H. Advantages and Disadvantages of Implant Navigation Surgery. A Systematic Review. Ann. Anat.—Anat. Anz. 2019, 225, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, A.; Arcuri, L.; Moy, P.K. The Smiling Scan Technique: Facially Driven Guided Surgery and Prosthetics. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2018, 62, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobczak, B.; Majewski, P. An Integrated Fully Digital Prosthetic Workflow for the Immediate Full-Arch Restoration of Edentulous Patients—A Case Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariente, L.; Dada, K.; Linder, S.; Dard, M. Immediate Implant Placement in the Esthetic Zone Using a Novel Tapered Implant Design and a Digital Integrated Workflow: A Case Series. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2023, 43, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, B.; Majewski, P.; Egorenkov, E. Survival and Success of 3D-Printed Versus Milled Immediate Provisional Full-Arch Restorations: A Retrospective Analysis. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2025, 27, e13418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelinakis, G.; Apostolakis, D.; Kamposiora, P.; Papavasiliou, G.; Özcan, M. The Direct Digital Workflow in Fixed Implant Prosthodontics: A Narrative Review. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkūnas, V.; Auškalnis, L.; Pletkus, J. Intraoral Scanners in Implant Prosthodontics. A Narrative Review. J. Dent. 2024, 148, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarba, B.M.; Fontenele, R.C.; Tarce, M.; Jacobs, R. Artificial Intelligence Serving Presurgical Digital Implant Planning: A Scoping Review. J. Dent. 2024, 143, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, O.; Schweiger, J.; Stimmelmayr, M.; Nold, E.; Güth, J.-F. Digital Implant Planning and Guided Implant Surgery—Workflow and Reliability. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joda, T.; Gallucci, G.O. The Virtual Patient in Dental Medicine. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 725–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, C.; Luongo, F.; Migliario, M.; Mortellaro, C.; Mangano, F.G. Combining Intraoral Scans, Cone Beam Computed Tomography and Face Scans: The Virtual Patient. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2018, 29, 2241–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coachman, C.; Sesma, N.; Blatz, M.B. The Complete Digital Workflow in Interdisciplinary Dentistry. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2021, 16, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.Y.; Luo, Y.L.; Wu, Y.Y.; Xiang, L.; Yang, X.M.; Qu, Y.L.; Tian, T.R.; Man, Y. Recent Advances in Digital Technology in Implant Dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyridakos, P.; Chen, Y.; Gonzalez-Gusmao, I.; Att, W. Complete Digital Workflow in Prosthesis Prototype Fabrication for Complete-Arch Implant Rehabilitation: A Technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 122, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carosi, P.; Ferrigno, N.; De Renzi, G.; Laureti, M. Digital Workflow to Merge an Intraoral Scan and CBCT of Edentulous Maxilla: A Technical Report. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auduc, C.; Douillard, T.; Nicolas, E.; El Osta, N. Fully Digital Workflow in Full-Arch Implant Rehabilitation: A Descriptive Methodological Review. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, F.; Nogueira-Reis, F.; Stanciu, E.M.; Smolders, A.; Jacobs, R.; Shaheen, E. Validation of Automated Registration of Intraoral Scan onto Cone Beam Computed Tomography for an Efficient Digital Dental Workflow. J. Dent. 2024, 149, 105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Romero, V.; Jorba-Garcia, A.; Camps-Font, O.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. Accuracy of Dynamic Computer-Assisted Implant Surgery in Fully Edentulous Patients: An in Vitro Study. J. Dent. 2024, 149, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez Bautista, N.; Meniz-García, C.; López-Carriches, C.; Sánchez-Labrador, L.; Cortés-Bretón Brinkmann, J.; Madrigal Martínez-Pereda, C. Accuracy of Different Systems of Guided Implant Surgery and Methods for Quantification: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biun, J.; Dudhia, R.; Arora, H. The In-vitro Accuracy of Fiducial Marker-based versus Markerless Registration of an Intraoral Scan with a Cone-beam Computed Tomography Scan in the Presence of Restoration Artifact. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2023, 34, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.-W.; Mai, H.-N.; Lee, D.-H. Comparison of the Accuracy of Image Registration Methods for Merging Optical Scan and Radiographic Data in Edentulous Jaws. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Fellows, C.; An, H. Digital Technologies for Restorative Dentistry. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 66, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepidi, L.; Galli, M.; Grammatica, A.; Joda, T.; Wang, H.-L.; Li, J. Indirect Digital Workflow for Virtual Cross-Mounting of Fixed Implant-Supported Prostheses to Create a 3D Virtual Patient. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flügge, T.; Kramer, J.; Nelson, K.; Nahles, S.; Kernen, F. Digital Implantology—A Review of Virtual Planning Software for Guided Implant Surgery. Part II: Prosthetic Setup and Virtual Implant Planning. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernen, F.; Kramer, J.; Wanner, L.; Wismeijer, D.; Nelson, K.; Flügge, T. A Review of Virtual Planning Software for Guided Implant Surgery—Data Import and Visualization, Drill Guide Design and Manufacturing. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P. The Passive Fit Concept- A Review of Methods to Achieve and Evaluate in Multiple Unit Implant Supported Screw Retained Prosthesis. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2021, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Corchado, E.; Pardal-Peláez, B. Computer-Guided Surgery for Dental Implant Placement: A Systematic Review. Prosthesis 2022, 4, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristache, C.M.; Burlibasa, M.; Tudor, I.; Totu, E.E.; Di Francesco, F.; Moraru, L. Accuracy, Labor-Time and Patient-Reported Outcomes with Partially versus Fully Digital Workflow for Flapless Guided Dental Implants Insertion—A Randomized Clinical Trial with One-Year Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadilina, S.; Vietor, K.; Doliveux, R.; Siu, A.; Chen, Z.; Al-Nawas, B.; Mattheos, N.; Pozzi, A. Beyond Accuracy: Clinical Outcomes of Computer Assisted Implant Surgery. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2025, 11, e70129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, T.; Keul, C.; Wismeijer, D.; Güth, J.F. Time and Costs Related to Computer-assisted versus Non-computer-assisted Implant Planning and Surgery. A Systematic Review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2021, 32, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhopte, A.; Bagde, H. Smart Smile: Revolutionizing Dentistry With Artificial Intelligence. Cureus 2023, 15, e41227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirko, J.; Shi, W. Disruptive Innovation Events in Dentistry. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2024, 155, 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aseri, A.A. Exploring the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Dental Implantology: A Scholarly Review. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2025, 17, S102–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, M.; Islam, S. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Restorative Dentistry: Current Trends and Future Prospects. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaranayake, L.; Tuygunov, N.; Schwendicke, F.; Osathanon, T.; Khurshid, Z.; Boymuradov, S.A.; Cahyanto, A. The Transformative Role of Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: A Comprehensive Overview. Part 1: Fundamentals of AI, and Its Contemporary Applications in Dentistry. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, R.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Nikparto, N.; Bahador, A. Robot-Assisted Dental Implant Surgery Procedure: A Literature Review. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, S.; Vu, G.; Gurupur, V.; King, C. Digital Convergence in Dental Informatics: A Structured Narrative Review of Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things, Digital Twins, and Large Language Models with Security, Privacy, and Ethical Perspectives. Electronics 2025, 14, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani, M. Trends and Classification of Artificial Intelligence Models Utilized in Dentistry: A Bibliometric Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e81836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuygunov, N.; Samaranayake, L.; Khurshid, Z.; Rewthamrongsris, P.; Schwendicke, F.; Osathanon, T.; Yahya, N.A. The Transformative Role of Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: A Comprehensive Overview Part 2: The Promise and Perils, and the International Dental Federation Communique. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, R.; Upadhyay, G.; Kalia, D.; Verma, K. Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics: Current Applications and Future Avenues: A Narrative Review. J. Prim. Care Dent. Oral Health 2024, 5, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Karnik, A.P.; Chhajer, H.; Venkatesh, S.B. Transforming Prosthodontics and Oral Implantology Using Robotics and Artificial Intelligence. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5, 1442100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Mohammad Rahimi, H.; Tichy, A. Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 69, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Brägger, U. Time-Efficiency Analysis Comparing Digital and Conventional Workflows for Implant Crowns: A Prospective Clinical Crossover Trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2015, 30, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind 1950, 59, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizenbaum, J. ELIZA—A Computer Program for the Study of Natural Language Communication between Man and Machine. Commun. ACM 1966, 9, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Slomka, P.J.; Leeson, P.; Comaniciu, D.; Shrestha, S.; Sengupta, P.P.; Marwick, T.H. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 1317–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Auckland, New Zealand, 2–6 December 2024; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of Decision Trees. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kabir, T.; Nelson, J.; Sheng, S.; Meng, H.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Walji, M.F.; Jiang, X.; Shams, S. Use of the Deep Learning Approach to Measure Alveolar Bone Level. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, P.-J.; Smolders, A.; Beznik, T.; Meewis, J.; Vandemeulebroucke, A.; Shaheen, E.; Van Gerven, A.; Willems, H.; Politis, C.; Jacobs, R. Layered Deep Learning for Automatic Mandibular Segmentation in Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. J. Dent. 2021, 114, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samek, W.; Wiegand, T.; Müller, K.-R. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Understanding, Visualizing and Interpreting Deep Learning Models. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.08296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallineni, S.K.; Sethi, M.; Punugoti, D.; Kotha, S.B.; Alkhayal, Z.; Mubaraki, S.; Almotawah, F.N.; Kotha, S.L.; Sajja, R.; Nettam, V.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: A Descriptive Review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Samek, W.; Krois, J. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: Chances and Challenges. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurzo, A.; Urbanová, W.; Novák, B.; Czako, L.; Siebert, T.; Stano, P.; Mareková, S.; Fountoulaki, G.; Kosnáčová, H.; Varga, I. Where Is the Artificial Intelligence Applied in Dentistry? Systematic Review and Literature Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarba, B.M.; Ali, S.; Fontenele, R.C.; Meeus, J.; Jacobs, R. An AI-Based Tool for Prosthetic Crown Segmentation Serving Automated Intraoral Scan-to-CBCT Registration in Challenging High Artifact Scenarios. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 134, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarba, B.M.; Fontenele, R.C.; Mangano, F.; Jacobs, R. Novel AI-Based Automated Virtual Implant Placement: Artificial versus Human Intelligence. J. Dent. 2024, 147, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarba, B.M.; Van Aelst, S.; Swaity, A.; Morgan, N.; Shujaat, S.; Jacobs, R. Deep Learning-Based Segmentation of Dental Implants on Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Images: A Validation Study. J. Dent. 2023, 137, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsonbaty, S.; Elgarba, B.M.; Fontenele, R.C.; Swaity, A.; Jacobs, R. Novel AI-Based Tool for Primary Tooth Segmentation on CBCT Using Convolutional Neural Networks: A Validation Study. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2025, 35, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontenele, R.C.; Gerhardt, M.D.N.; Picoli, F.F.; Van Gerven, A.; Nomidis, S.; Willems, H.; Freitas, D.Q.; Jacobs, R. Convolutional Neural Network-based Automated Maxillary Alveolar Bone Segmentation on Cone-beam Computed Tomography Images. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2023, 34, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindanil, T.; Marinho-Vieira, L.E.; de-Azevedo-Vaz, S.L.; Jacobs, R. A Unique Artificial Intelligence-Based Tool for Automated CBCT Segmentation of Mandibular Incisive Canal. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2023, 52, 20230321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira-Reis, F.; Morgan, N.; Suryani, I.R.; Tabchoury, C.P.M.; Jacobs, R. Full Virtual Patient Generated by Artificial Intelligence-Driven Integrated Segmentation of Craniomaxillofacial Structures from CBCT Images. J. Dent. 2024, 141, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Santos, N.; Jacobs, R.; Picoli, F.F.; Lahoud, P.; Niclaes, L.; Groppo, F.C. Automated Segmentation of the Mandibular Canal and Its Anterior Loop by Deep Learning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaity, A.; Elgarba, B.M.; Morgan, N.; Ali, S.; Shujaat, S.; Borsci, E.; Chilvarquer, I.; Jacobs, R. Deep Learning Driven Segmentation of Maxillary Impacted Canine on Cone Beam Computed Tomography Images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Alqahtani, K.A.; Van Den Bogaert, T.; Shujaat, S.; Jacobs, R.; Shaheen, E. Convolutional Neural Network for Automated Tooth Segmentation on Intraoral Scans. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, M.; Alahmari, M.; Almuaddi, A.; Abdelmagyd, H.; Rao, K.; Hamdoon, Z.; Alsaegh, M.; Chaitanya, N.C.S.K.; Shetty, S. Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence-Based Segmentation in Maxillofacial Structures: A Systematic Review. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankert, T.; Lee, H.; Peters, F.; Hölzle, F.; Modabber, A.; Raith, S. Mandible Segmentation from CT Data for Virtual Surgical Planning Using an Augmented Two-Stepped Convolutional Neural Network. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2023, 18, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasya, H.; Jaju, P.P.; Ezhov, M.; Gusarev, M.; Atakan, C.; Sanders, A.; Manulius, D.; Golitskya, M.; Shrivastava, K.; Singh, A.; et al. Development and Validation of an Artificial Intelligence Software for Periodontal Bone Loss in Panoramic Imaging. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Tech. 2024, 34, e22973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhov, M.; Gusarev, M.; Golitsyna, M.; Yates, J.M.; Kushnerev, E.; Tamimi, D.; Aksoy, S.; Shumilov, E.; Sanders, A.; Orhan, K. Clinically Applicable Artificial Intelligence System for Dental Diagnosis with CBCT. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierczak, W.; Kazimierczak, N.; Issa, J.; Wajer, R.; Wajer, A.; Kalka, S.; Serafin, Z. Endodontic Treatment Outcomes in Cone Beam Computed Tomography Images—Assessment of the Diagnostic Accuracy of AI. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt Bayrakdar, S.; Orhan, K.; Bayrakdar, I.S.; Bilgir, E.; Ezhov, M.; Gusarev, M.; Shumilov, E. A Deep Learning Approach for Dental Implant Planning in Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Images. BMC Med. Imaging 2021, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mema, H.; Gaxhja, E.; Alicka, Y.; Gugu, M.; Topi, S.; Giannoni, M.; Pietropaoli, D.; Altamura, S. Application of AI-Driven Software Diagnocat in Managing Diagnostic Imaging in Dentistry: A Retrospective Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, K.; Aktuna Belgin, C.; Manulis, D.; Golitsyna, M.; Bayrak, S.; Aksoy, S.; Sanders, A.; Önder, M.; Ezhov, M.; Shamshiev, M.; et al. Determining the Reliability of Diagnosis and Treatment Using Artificial Intelligence Software with Panoramic Radiographs. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2023, 53, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakirov, A.; Ezhov, M.; Gusarev, M.; Alexandrovsky, V.; Shumilov, E. Dental Pathology Detection in 3D Cone-Beam CT. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asali, M.; Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Al-Sarem, M.; Saeed, F. Deep Learning-Based Approach for 3D Bone Segmentation and Prediction of Missing Tooth Region for Dental Implant Planning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, H.; Hauschild, U.; Sader, R.; Ghanaati, S. Complete-Arch Fixed Reconstruction by Means of Guided Surgery and Immediate Loading: A Retrospective Clinical Study on 12 Patients with 1 Year of Follow-Up. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.-H.; Çakmak, G.; Choi, J.; Lee, D.; Yoon, H.-I.; Yilmaz, B.; Schimmel, M. Deep Learning-Designed Implant-Supported Posterior Crowns: Assessing Time Efficiency, Tooth Morphology, Emergence Profile, Occlusion, and Proximal Contacts. J. Dent. 2024, 147, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, G.; Cho, J.-H.; Choi, J.; Yoon, H.-I.; Yilmaz, B.; Schimmel, M. Can Deep Learning-Designed Anterior Tooth-Borne Crown Fulfill Morphologic, Aesthetic, and Functional Criteria in Clinical Practice? J. Dent. 2024, 150, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.-H.; Çakmak, G.; Jee, E.-B.; Yoon, H.-I.; Yilmaz, B.; Schimmel, M. A Comparison between Commercially Available Artificial Intelligence-Based and Conventional Human Expert-Based Digital Workflows for Designing Anterior Crowns. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlaing, N.H.M.M.; Çakmak, G.; Karasan, D.; Kim, S.-J.; Sailer, I.; Lee, J.-H. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Automated Design of Anterior and Posterior Crowns Under Diverse Occlusal Scenarios. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Cui, Z.; Maghami, E.; Chen, Y.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Pow, E.H.N.; Fok, A.S.L.; Burrow, M.F.; Wang, W.; Tsoi, J.K.H. Morphology and Mechanical Performance of Dental Crown Designed by 3D-DCGAN. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Gali, S.; Augustine, D.; Sv, S. Artificial Intelligence Systems in Dental Shade-Matching: A Systematic Review. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 33, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsin, L.; Alenezi, N.; Rashdan, Y.; Hassan, A.; Alenezi, M.; Alam, M.K.; Noor, N.F.B.M.; Akhter, F. Development of AI-Enhanced Smile Design Software for Ultra-Customized Aesthetic Outcomes. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2025, 17, S1282–S1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceylan, G.; Özel, G.S.; Memişoglu, G.; Emir, F.; Şen, S. Evaluating the Facial Esthetic Outcomes of Digital Smile Designs Generated by Artificial Intelligence and Dental Professionals. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jin, G.; Park, J.-H.; Jung, H.-I.; Kim, J.-E. Evaluation Metric of Smile Classification by Peri-Oral Tissue Segmentation for the Automation of Digital Smile Design. J. Dent. 2024, 145, 104871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.; Cheng, Z.; Ungvijanpunya, N.; Chen, W.; Cao, L.; Gou, Y. Is Automatic Cephalometric Software Using Artificial Intelligence Better than Orthodontist Experts in Landmark Identification? BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.-Y.; Yoon, H.-I.; Yeo, I.-S.; Huh, K.-H.; Han, J.-S. Peri-Implant Bone Loss Measurement Using a Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network on Dental Periapical Radiographs. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, N.-F.; Alexandra, D.-S.; Yun, C.; Palma-Fernández, J.C.; Alejandro, I.-L. Ai-aided volumetric root resorption assessment following personalized forces in orthodontics: Preliminary results of a randomized clinical trial. J. Evid.-Based Dent. Pract. 2025, 25, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-J.; Lee, S.-J.; Yong, T.-H.; Shin, N.-Y.; Jang, B.-G.; Kim, J.-E.; Huh, K.-H.; Lee, S.-S.; Heo, M.-S.; Choi, S.-C.; et al. Deep Learning Hybrid Method to Automatically Diagnose Periodontal Bone Loss and Stage Periodontitis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setzer, F.C.; Shi, K.J.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, H.; Yoon, H.; Mupparapu, M.; Li, J. Artificial Intelligence for the Computer-Aided Detection of Periapical Lesions in Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic Images. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, M.; Inamoto, K.; Shibata, N.; Ariji, Y.; Yanashita, Y.; Kutsuna, S.; Nakata, K.; Katsumata, A.; Fujita, H.; Ariji, E. Evaluation of an Artificial Intelligence System for Detecting Vertical Root Fracture on Panoramic Radiography. Oral Radiol. 2020, 36, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossowska, A.; Kusiak, A.; Świetlik, D. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry—Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaohoen, A.; Powcharoen, W.; Sornsuwan, T.; Chaijareenont, P.; Rungsiyakull, C.; Rungsiyakull, P. Accuracy of Implant Placement with Computer-Aided Static, Dynamic, and Robot-Assisted Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolding, S.L.; Reebye, U.N. Accuracy of Haptic Robotic Guidance of Dental Implant Surgery for Completely Edentulous Arches. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.A.; Hann, S.; Elsheikh, A.K.; Boltchi, F.; Zandinejad, A. A Complete Digital Approach for Facially Generated Full Arch Diagnostic Wax up, Guided Surgery, and Implant-supported Interim Prosthesis by Integrating 3D Facial Scanning, Intraoral Scan and CBCT. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Gallucci, G.O.; Wismeijer, D.; Zitzmann, N.U. Augmented and Virtual Reality in Dental Medicine: A Systematic Review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2019, 108, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntovas, P.; Sirirattanagool, P.; Asavanamuang, P.; Jain, S.; Tavelli, L.; Revilla-León, M.; Galarraga-Vinueza, M.E. Accuracy and Time Efficiency of Artificial Intelligence-Driven Tooth Segmentation on CBCT Images: A Validation Study Using Two Implant Planning Software Programs. Clin. Oral Impl. Res. 2025, 36, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarce, M.; Zhou, Y.; Antonelli, A.; Becker, K. The Application of Artificial Intelligence for Tooth Segmentation in CBCT Images: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarba, B.M.; Fontenele, R.C.; Du, X.; Mureșanu, S.; Tarce, M.; Meeus, J.; Jacobs, R. Artificial Intelligence Versus Human Intelligence in Presurgical Implant Planning: A Preclinical Validation. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2025, 36, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Bi, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Tai, Y.; Luo, E. Machine Learning-Based Decision Support System for Orthognathic Diagnosis and Treatment Planning. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coachman, C.; Georg, R.; Bohner, L.; Rigo, L.C.; Sesma, N. Chairside 3D Digital Design and Trial Restoration Workflow. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 124, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokhshad, R.; Karteva, T.; Chaurasia, A.; Richert, R.; Mörch, C.-M.; Tamimi, F.; Ducret, M. Artificial Intelligence and Smile Design: An e-Delphi Consensus Statement of Ethical Challenges. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 33, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, N.; Sudharson, N.A.; Varghese, K.G. Artificial Intelligence. Br. Dent. J. 2024, 236, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaj, R.E.; Alangari, T.A. Artificial Intelligence Applications in Smile Design Dentistry: A Scoping Review. J. Prosthodont. 2025, 34, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, A.; Leonardi, R. Automatic Cephalometric Landmark Identification with Artificial Intelligence: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. J. Dent. 2024, 146, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Bai, X.; Ding, Y.; Shen, L.; Sun, X.; Cao, R.; Yang, F.; Wang, L. Comparison the Accuracy of a Novel Implant Robot Surgery and Dynamic Navigation System in Dental Implant Surgery: An in Vitro Pilot Study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, B.; Feng, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhuang, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, F.; Wu, Y. Accuracy of Dental Implant Surgery Using Dynamic Navigation and Robotic Systems: An in Vitro Study. J. Dent. 2022, 123, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Li, A.; Unkovskiy, A.; Li, J.; Beuer, F.; Wu, Z.; Li, P. Accuracy of Robotic Computer-Assisted Implant Surgery in Clinical Studies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Xie, R.; Li, Z.; Bai, S.; Zhao, Y. The Evolution of Robotics: Research and Application Progress of Dental Implant Robotic Systems. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigcho López, D.A.; García, I.; Da Silva Salomao, G.; Cruz Laganá, D. Potential Deviation Factors Affecting Stereolithographic Surgical Guides: A Systematic Review. Implant. Dent. 2019, 28, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, M.; Bellardini, M. How Much Does Experience in Guided Implant Surgery Play a Role in Accuracy? A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.S.; Emery, R.W.; Cullum, D.R.; Sheikh, A. Implant Placement Is More Accurate Using Dynamic Navigation. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.-M.; Lee, H.-E.; Lan, T.-H. The Influence of Dental Experience on a Dental Implant Navigation System. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozer, P.S. Accuracy and Deviation Analysis of Static and Robotic Guided Implant Surgery: A Case Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2020, 35, e86–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, J.; Li, A.; Li, P.; Xu, S. Autonomous Robotic Surgery for Immediately Loaded Implant-Supported Maxillary Full-Arch Prosthesis: A Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roccuzzo, M.; Layton, D.M.; Roccuzzo, A.; Heitz-Mayfield, L.J. Clinical Outcomes of Peri-implantitis Treatment and Supportive Care: A Systematic Review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokn, A.; Aslroosta, H.; Akbari, S.; Najafi, H.; Zayeri, F.; Hashemi, K. Prevalence of Peri-implantitis in Patients Not Participating in Well-designed Supportive Periodontal Treatments: A Cross-sectional Study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2017, 28, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, A.; Lombardi, T. Frontiers in the Understanding of Peri-Implant Disease. In Periodontal Frontiers; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Lombardi, T. Treatment of Peri-Implant Disease: Current Knowledge. In Periodontal Frontiers; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Derks, J.; Monje, A.; Wang, H.-L. Peri-Implantitis. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 (Suppl. 1), S267–S290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| # | Study (First Author, Year; Ref #) | Clinical Task | AI Model | Dataset (as Reported/Summarized) | Primary Metric(s) | Main Outcome (Short) | Approx. TRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verhelst et al., 2021; + subsequent Relu-based studies (2021–2025) [68,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] | Automated CBCT segmentation of dentoalveolar structures (mandible, maxilla, teeth, mandibular canal, alveolar bone) and 3D virtual patient generation | Multi-stage 3D U-Net CNN (Relu Creator/Virtual Patient Creator), cloud-based voxel-wise segmentation | Aggregated across studies: ~150–250 CBCTs per structure for training; 20–40 test scans per study; multi-device datasets (NewTom, Morita, Planmeca); includes CBCT-only and CBCT + IOS datasets | Dice/IoU, HD95, surface deviation, segmentation time, inter-run consistency | High-accuracy segmentation (Dice 0.90–0.98 across structures), instant inference (20–60 s), consistent across CBCT devices, 50–100× faster than manual workflows; widely validated across multiple independent clinical studies | 9 (FDA-cleared & CE-marked commercial system; extensively validated; in routine clinical use) |

| 2 | Alahamari et al., 2025 systematic review [83] | Radiological segmentation of teeth, jaws, TMJ, mandibular canal | Multiple DL CNNs and TML models | 30 included studies across CBCT/CT modalities | Dice, surface deviation, and other overlap metrics | DL models consistently achieved high overlaps and outperformed TML approaches across most structures | 5–6 (portfolio of mostly prototype/early clinical tools) |

| 3 | Pankert et al., 2023 [84] | Mandible segmentation with metal artifact reduction on CT | Two-step 3D U-Net CNN pipeline | CT datasets with metal restorations/implants | Dice, accuracy vs. manual/semi-automatic, processing time | Artifact-compensated 3D models in ~31 s per scan with higher accuracy and markedly reduced manual workload | 4–5 (advanced proof-of-concept/early clinical validation) |

| 4 | Ezhov et al., 2021; Bayrakdar et al., 2021; plus multiple subsequent Diagnocat evaluations (2021–2025) [85,86,87,88,89,90,91] | AI-assisted diagnostic support and reporting on CBCT, panoramic, and intraoral radiographs; automated multi-pathology detection; implant-site analysis and planning | Hybrid 2D/3D CNN architecture: coarse-to-fine volumetric 3D CNN for CBCT tooth and pathology segmentation; 2D CNN modules for caries, restorations, periodontal bone loss, missing teeth; cloud-based SaaS platform (Diagnocat) | CBCT datasets (100–300 scans per task); panoramic datasets (100–4500 annotated teeth); multimodal datasets (CBCT + OPG + IO) across heterogeneous devices; includes studies on implant planning, airway analysis, caries, periapical pathology, and periodontal disease | Accuracy, sensitivity/specificity, Dice/IoU, AUC, inter-rater agreement (vs. expert panels), diagnostic concordance, time savings | Consistent diagnostic performance on CBCT and OPG; high agreement with expert references for periapical pathology, bone levels, and implant-site metrics; significant time savings in structured reporting; robust performance across imaging modalities | 9 (FDA-cleared, CE-marked, Health Canada–approved commercial system in routine clinical use) |

| 5 | Al-Asali et al., 2024 [92] | Fully automated implant planning: bone segmentation + implant position prediction | Two consecutive 3D U-Net models | CBCT datasets with edentulous sites for implant placement | Segmentation accuracy, positional error of proposed implants, planning time | Accurate bone segmentation and near-instant (~10 s) generation of implant proposals with high concordance to expert plans | 4–5 (technically robust, but still research-prototype) |

| 6 | Lerner et al., 2020 [93] | Automated retrieval/design of implant abutments and subgingival margins | AI module embedded in CAD software (feature-based ML/DL) | IOS data and original abutment library | Workflow time, need for manual gingival margin tracing; qualitative fit/aesthetics | Automated realignment of original abutment designs and margin definition, eliminating manual margin tracing and streamlining abutment design | 5–6 (integrated into specialized CAD workflows, limited commercial roll-out) |

| 7 | Cho et al., 2024 [94] | DL-based design of implant-supported posterior crowns | CNN-based DL crown generator | Digital models of posterior implant cases | Design time; occlusal table area; cusp height/angle; proximal contacts; occlusal contact pattern | DL crowns generated in ~83 s vs. 322–371 s for technician-optimized/DL-assisted or conventional CAD, with comparable occlusal and contact parameters | 5–6 (strong technical validation; not yet mainstream clinical product) |

| 8 | Various authors, DL anterior & posterior crown design studies [94,95,96,97,98] | Automated design of tooth-borne and posterior crowns | Various 3D CNNs and 3D-GAN models | IOS/cast scan datasets of anterior and posterior crowns | Morphologic & functional metrics (incisal path, inclination, occlusal relation, marginal fit, contact quality), design time | DL-generated crowns showed clinically acceptable morphology and function, superior time efficiency and posterior crown quality vs. conventional automated CAD; limited human refinement still helpful in complex esthetic cases | 4–5 (advanced research tools; early commercial pilots via Exocad AI, 3Shape Automate, DTX Studio, etc.) |

| 9 | Shetty et al., systematic review [99] | AI-based crown shade matching | Multiple CNN/ML shade-matching algorithms | Collection of in vitro and in vivo shade-matching studies | Shade-matching accuracy vs. visual methods, agreement with reference devices | Review concluded that AI-based shade matching is promising and can improve consistency, but available evidence is still limited and heterogeneous | 3–4 (early-stage; few robust clinical implementations) |

| 10 | Mohsin et al., 2025 [100] | AI-enhanced digital smile design (DSD) with facial feature analysis | Hybrid CNN + GAN architecture | Clinical smile design cases with 2D facial photographs | Patient satisfaction scores; expert aesthetic ratings; design time | AI-enhanced DSD produced higher patient satisfaction and aesthetic ratings and reduced design time by ~40% compared with conventional DSD | 4–5 (pilot software; not yet widely commercialized) |

| 11 | Ceylan et al., 2024 [101] | Comparison of AI-generated vs. conventional DSD layouts | Proprietary AI DSD engine (likely CNN-based) | Clinical cases with symmetric/asymmetric smiles | Subjective aesthetic ratings, usability, design time | AI-generated designs were generally acceptable, especially in symmetric faces, and offered relevant time savings independent of user experience | 4–5 (experimental/early clinical tool) |

| 12 | Lee et al., 2024 [102] | Automatic segmentation and classification of peri-oral tissues and smile types | CNN-based segmentation + classifier | Clinical 2D facial/smile images | Segmentation accuracy; smile-type classification accuracy | Reliable segmentation of lips/teeth and classification of smile types, enabling a key technical step towards fully automated DSD pipelines | 3–4 (technical enabler; not a standalone clinical product yet) |

| 13 | Ye et al., 2023 [103] | Automated cephalometric landmarking for ortho/DSD integration | DL and ML in commercial cephalometric tools (MyOrthoX, Angelalign, Digident) | Lateral cephalograms assessed by software vs. experienced orthodontists | Landmark error vs. expert; analysis time | AI-based cephalometric systems achieved accuracy comparable to orthodontists and reduced analysis time by up to 50%, while still requiring human supervision | 8–9 (commercial software with broad clinical use) |

| 14 | Cha et al., 2022 [104] | Automated measurement of peri-implant bone loss on periapical radiographs | Modified R-CNN deep CNN | Periapical radiographs of implants with serial follow-up | Measurement error vs. human raters; diagnostic agreement indices | R-CNN model measured peri-implant bone loss with performance comparable to dentists, supporting its use as future maintenance/recall aid | 4–5 (pilot stage; not widely commercialized yet) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lombardi, T.; Perez, A. Integration and Innovation in Digital Implantology–Part II: Emerging Technologies and Converging Workflows: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12789. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312789

Lombardi T, Perez A. Integration and Innovation in Digital Implantology–Part II: Emerging Technologies and Converging Workflows: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12789. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312789

Chicago/Turabian StyleLombardi, Tommaso, and Alexandre Perez. 2025. "Integration and Innovation in Digital Implantology–Part II: Emerging Technologies and Converging Workflows: A Narrative Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12789. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312789

APA StyleLombardi, T., & Perez, A. (2025). Integration and Innovation in Digital Implantology–Part II: Emerging Technologies and Converging Workflows: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12789. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312789