Condition Assessment of Road Markings in Denmark, Norway and Sweden—A Comparison Between Retroreflectivity, Visibility and Preview Time

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim

2. Materials and Methods

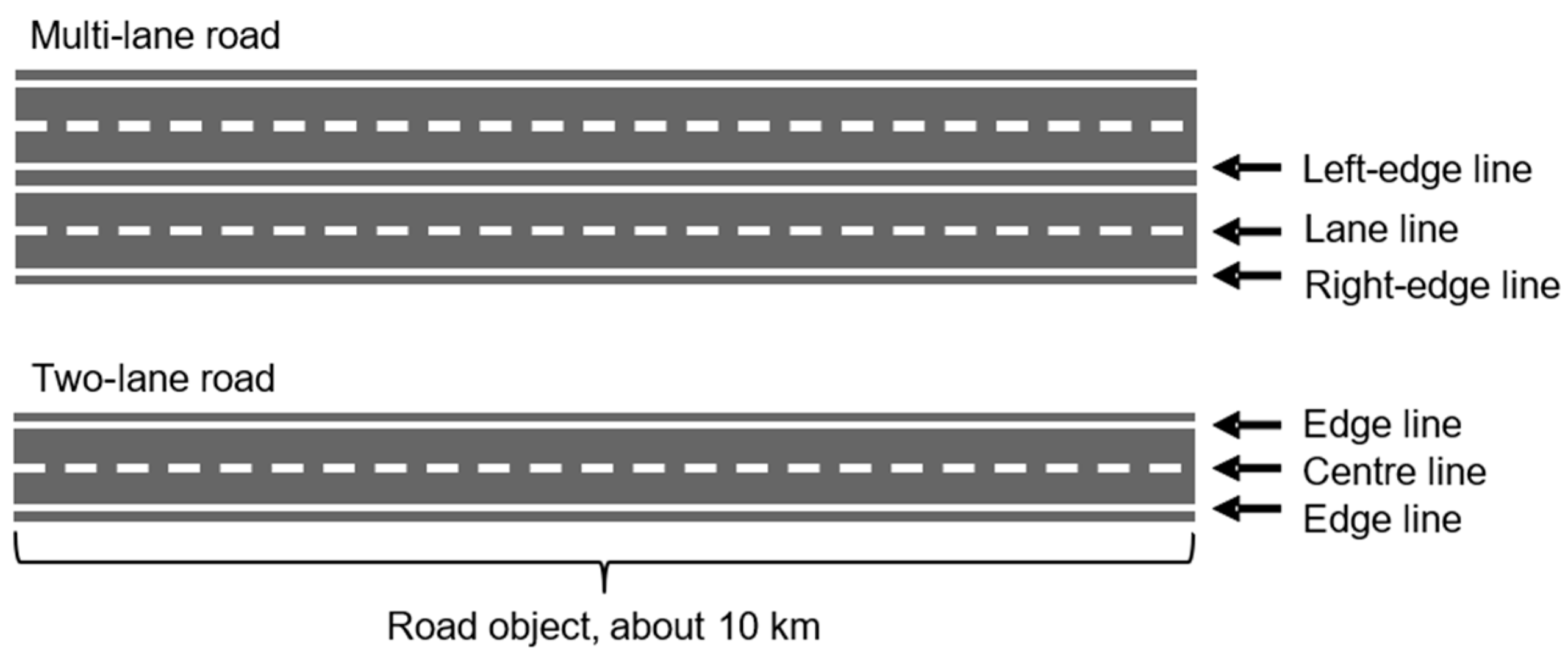

2.1. Measured Objects

2.2. Measurements and Data

- Denmark: 15 April–1 October.

- Sweden: 15 May (starting in the south)–1 October.

- Norway: 15 June (starting in the south)–1 October.

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Retroreflectivity

2.3.2. Visibility

- Driver age: 60 years;

- Vehicle type: passenger car;

- Vehicle light distribution: low-beam, 75th percentile of the revised light distribution;

- Retroreflectivity of the road surface: 15 mcd/m2/lx;

- Position of road marking: 1.75 m to the right of the vehicle’s center line;

- No veiling luminance or other light sources;

- Visibility level (VL): 6.5.

2.3.3. Preview Time

2.4. Statistical Analyses

- αi = country (Denmark, Norway, Sweden);

- βj = year (2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021);

- θk = road class (2 L low, 2 L high, MW low, MW high).

3. Results

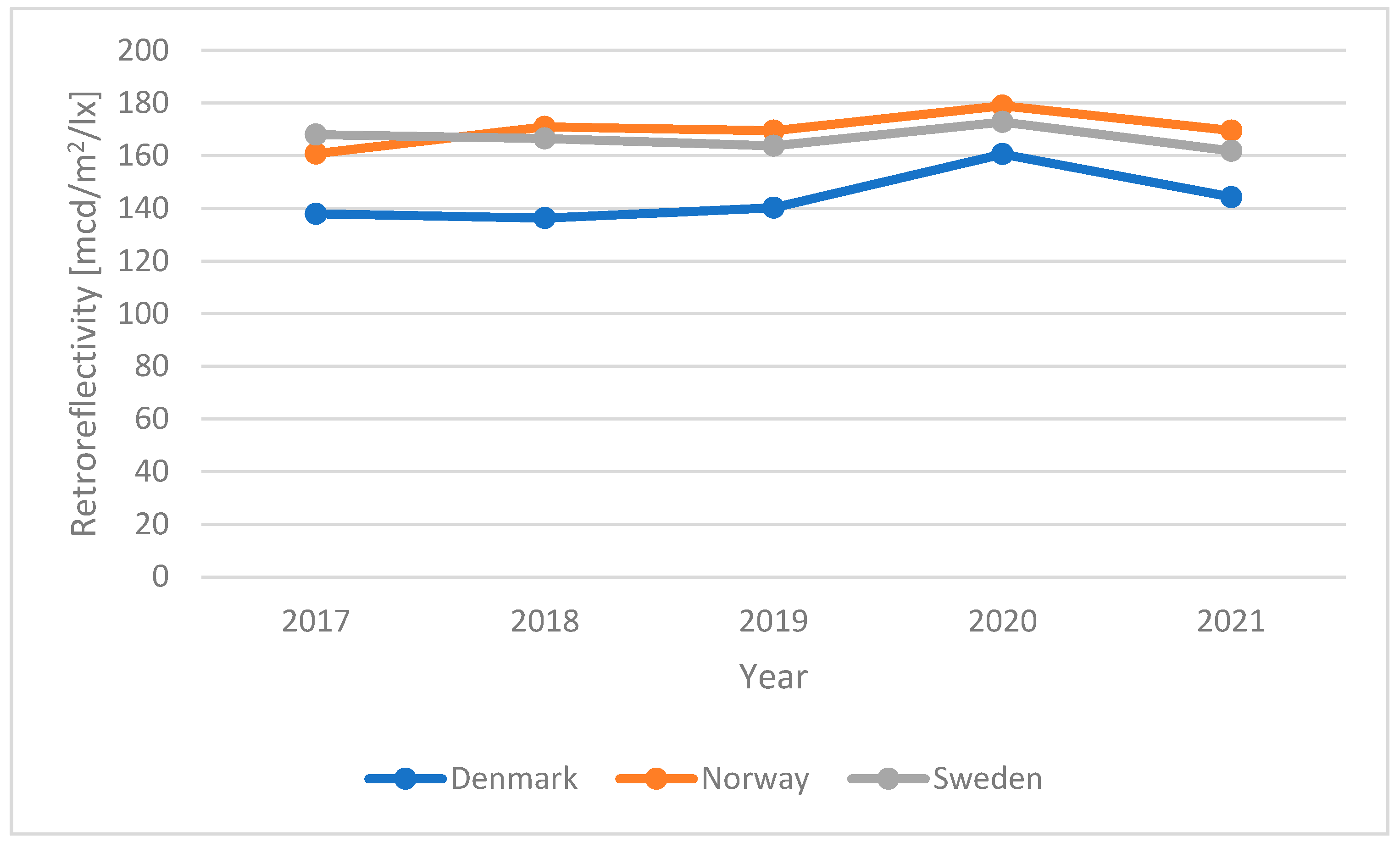

3.1. Mean Performance per Country, Year and Road Class

3.2. Mean Performance per Country and Road Class

3.3. Mean Performance on the TEN-T Network

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Comparison | Retroreflectivity (mcd/m2/lx) | Visibility (m) | Preview Time (s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference | CI (95%) | Mean Difference | CI (95%) | Mean Difference | CI (95%) | ||

| Denmark | MV high—MV low | −17.8 | (−39.3, 3.8) | 1.8 | (−5.0, 8.6) | −0.3 | (−0.6, 0.01) |

| MV high—2L high | −9.8 | (−28.4, 8.8) | 19.8 * | (13.9, 25.6) | −1.2 * | (−1.5, −0.9) | |

| MV high—2L low | −30.6 * | (−49.3, −12.0) | 8.9 * | (3.1, 14.8) | −1.6 * | (−1.9, −1.4) | |

| MV low—2L high | 8.0 | (−10.7, 26.7) | 18.0 * | (12.1, 23.9) | −0.9 * | (−1.1, −0.6) | |

| MV low—2L low | −12.9 | (−31.6, 5.8) | 7.2 * | (1.3, 13.0) | −1.3 * | (−1.6, −1.0) | |

| 2L high—2L low | −20.9 * | (−36.1, −5.7) | −10.8 * | (−15.6, −6.0) | −0.4 * | (−0.6, −0.2) | |

| Norway | MV high—MV low | 1.2 | (−21.5, 23.9) | 2.0 | (−5.1, 9.1) | 0.3 | (−0.04, 0.6) |

| MV high—2L high | −1.3 | (−18.2, 15.6) | 24.2 * | (18.9, 29.5) | −0.7 * | (−0.9, −0.5) | |

| MV high—2L low | −2.6 | (−19.3, 14.1) | 26.0 * | (20.8, 31.3) | −0.04 | (−0.3, 0.2) | |

| MV low—2L high | −2.5 | (−21.2, 16.2) | 22.2 * | (16.3, 28.1) | −1.0 * | (−1.3, −0.7) | |

| MV low—2L low | −3.8 | (−22.3, 14.7) | 24.0 * | (18.2, 29.9) | −0.4 * | (−0.6, −0.1) | |

| 2L high—2L low | −1.3 | (−11.9, 9.4) | 1.9 | (−1.5, 5.2) | 0.7 * | (0.5, 0.8) | |

| Sweden | MV high—MV low | −16.8 * | (−29.3, −4.4) | 4.2 * | (0.3, 8.1) | −0.04 | (−0.2, 0.1) |

| MV high—2L high | −6.7 | (−19.4, 5.9) | 37.5 * | (33.6, 41.5) | 0.1 | (−0.1, 0.3) | |

| MV high—2L low | −33.7 * | (−44.9, −22.4) | 39.2 * | (35.7, 42.7) | 0.3 * | (0.1, 0.4) | |

| MV low—2L high | 10.1 * | (0.3, 20.0) | 33.3 * | (30.2, 36.4) | 0.2 * | (0.01, 0.3) | |

| MV low—2L low | 16.8 * | (24.8, −8.8) | 35.0 * | (32.5, 37.5) | 0.3 * | (0.2, 0.4) | |

| 2L low—2L high | 27.0 * | (18.7, 35.2) | −1.7 | (−4.3, 0.9) | −0.2 * | (−0.3, −0.04) | |

References

- COST 331. Requirements for Horizontal Road Marking. Final Report of the Action; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1999.

- Babić, D.; Babić, D.; Fiolic, M.; Ferko, M. Road Markings and Signs in Road Safety. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1738–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvik, R.; Vaa, T. The Handbook of Road Safety Measures; Institute of Transport Economics: Oslo, Norway, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Høye, A. (Ed.) Chapter 3.13: Road marking [Vegoppmerking]. In Trafikksikkerhetshåndboken; Transportøkonomisk Institutt: Oslo, Norway, 2024; Available online: https://www.tshandbok.no/del-2/3-trafikkregulering/doc662/ (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Babić, D.; Fiolić, M.; Babić, D.; Gates, T. Road Markings and Their Impact on Driver Behaviour and Road Safety: A Systematic Review of Current Findings. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 7843743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwahlen, H.T.; Schnell, T. Minimum In-Service Retroreflectivity of Pavement Markings. Transp. Res. Rec. 2000, 1715, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deballion, C.; Carlson, P.J.; He, Y.; Schnell, T.; Aktan, F. Updates to Research on Recommended Minimum Levels for Pavement Marking Retroreflectivity to Mee Driver Night Visibility Needs; Final Report FHWA-HRT-07-059; FHWA, U.S. Department of Transportation: McLean, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zwahlen, H.T.; Schnell, T. Visibility of New Centerline and Edge Line Pavement Markings. Transp. Res. Rec. 1997, 1605, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohme, P.J.; Schnell, T. Is Wider Better?: Enhancing Pavement Marking Visibility for Older Drivers. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2001, 45, 1617–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, D.M.; Hodson, N.; Haunschild, D.; May, D. Pavement Marking Photometric Performance and Visibility under Dry, Wet, and Rainy Conditions: Pilot Field Study. Transp. Res. Rec. 2006, 1973, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.B.; Andersen, C.; Hankey, J. Wet Night Visibility of Pavement Markings a Static Experiment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2005, 1911, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, D.; Fiolić, M.; Babić, D.; Burghardt, T.E. Systematic Testing of Road Markings’ Retroreflectivity to Increase Their Sustainability through Improvement of Properties: Croatia Case Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VTI PM 2024:9A; Nordic Certification System for Road Marking Materials. Version 10:2024. The Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute: Linköping, Sweden, 2024.

- Vadeby, A.; Fors, C. ROMA. State Assessment of Road Markings in Denmark, Norway and Sweden—Results from 2021; Nord Fou Report 2022-02; NordFoU: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K. A Successor for the “Visibility” Program for the Visibility Distance to Longitudinal Road Markings. Available online: https://nmfv.dk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/A-successor-for-the-Visibility-program-for-the-calculation-of-visibility-distances-to-longitudinal-road-markings.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- TDOK 2013:0461; Trafikverket. Mobil Kontroll av Vägmarkering (Mobile Inspection of Road Markings). Version 2.0. Trafikverket: Borlänge, Sweden, 2017. (In Swedish)

- SS-EN 1436:2018; Road Marking Materials. Road Marking Performance for Road Users and Test Methods. Swedish Standards Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018.

- Fors, C. Synavstånd för Längsgående Vägmarkering. Validering av den Reviderade COST 331-Modellen (Visibility Distances of Longitudinal Road Markings. Validation of the Updated COST 331 Model); VTI Rapport 1048; The Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute: Linköping, Sweden, 2020; (In Swedish, summary in English). [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Vejdirektoratet. Vejledning til Vejafmærkningsbekendtgørelserne. Afmærkning på Kørebanen. Længdeafmærkning. Færdselregulering, March 2025; Vejdirektoratet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fager, H.; Johansen, T.C. Quality Control of Road Markings in the Nordic Countries. Prerequisites for a Common Regulatory Framework; VTI Rapport; The Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute: Linköping, Sweden, 2023; Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:vti:diva-20063 (accessed on 10 November 2025)(In Swedish, summary in English).

- Girard, J.; Lebouc, L.; Muzet, V. Is the COST 331 software still relevant for characterising the visibility of road markings? In Proceedings of the CIE Midterm Meeting, Vienna, Austria, 4–11 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, T.; Zwahlen, H.T. Driver Preview Distances at Night Based on Driver Eye Scanning Recordings as a Function of Pavement Marking Retroreflectivities. Transp. Res. Rec. 1999, 1692, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfi, T.; Shinar, D. Enhancement of road delineation can reduce safety. J. Saf. Res. 2014, 49, 61.e1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučina, I.; Kosovec, B.; Jezidžić, F.; Ferko, M.; Babić, D. The influence of road marking visibility on lateral vehicle position and driving speed. Acta Polytech. CTU Proc. 2025, 52, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järlskog, I.; Nyberg, E.; Fager, H.; Gustafsson, M.; Blomqvist, G. Microplastic Emissions from Wear of Road Markings: Overview and Assessment for Swedish Conditions; VTI Rapport; Statens väg- och Transportforskningsinstitut: Linköping, Sweden, 2024; Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:vti:diva-20676 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Babic, D.; Babic, D.; Scukanec, A.; Fiolic, M.; Brijs, T.; Polders, E.; Pirdavani, A.; Eichberger, A.; Milhalj, T.; Jeudy, M.; et al. RMSF—Road Markings and Road Signs for the Future. Final Report on the Study on Common Specifications for Road Markings and Road Signs. 2023. European Commission. Available online: https://documentserver.uhasselt.be/bitstream/1942/42574/1/Study%20on%20common%20specifications%20for%20road%20markings%20and%20road%20signs_FINAL%20REPORT.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Nygårdhs, S.; Fors, C.; Nielsen, B.; Felsgård-Hansen, M.; Laugesen, J. Machine-Readability of Road Markings in the Nordic Countries; NordFoU: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023; Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:vti:diva-19906 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Marr, J.; Benjamin, S.; Zhang, A. Implications of Pavement Markings for Machine Vision. Austroads Publication No. AP-R633-20; Sydney, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/77435/dot_77435_DS1.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwikr4O3jKGRAxUbETQIHT8gKUQQFnoECEAQAQ&usg=AOvVaw19u-h1IE7BdH8OD96T2cIf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Babić, D.; Babić, D.; Fiolić, M.; Eichberger, A.; Magosi, Z.F. Impact of road marking retroreflectivity on machine vision in dry conditions: On-road test. Sensors 2022, 22, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, A.M.; Barrette, T.P.; Carlson, P. Evaluation of the Effects of Pavement Marking Characteristics on Detectability by ADAS Machine Vision (Final Report). 2018. Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP20-102-06finalreport.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Fors, C.; Kälvesten, J.; Karim, H. Tillståndsbedömning av Vägmarkering med Fordonsgenererade Data: Etapp 1—Teknisk Utvärdering; VTI Rapport; Statens väg- och Transportforskningsinstitut: Linköping, Sweden, 2025; Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:vti:diva-21887 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Manasreh, D.; Nazzal, M.D.; Abbas, A.R. Feature-Centric Approach for Learning-Based Prediction of Pavement Marking Retroreflectivity from Mobile LiDAR Data. Buildings 2024, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Krine, A.; Redondin, M.; Girard, J.; Heinkele, C.; Stresser, A.; Muzet, V. Does the Condition of the Road Markings Have a Direct Impact on the Performance of Machine Vision during the Day on Dry Roads? Vehicles 2023, 5, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Road Class | Description |

|---|---|

| MW high | Motorway or multi-lane roads, 20,000 < AADT ≤ 50,000 |

| MW low | Motorway or multi-lane roads, AADT ≤ 20,000 |

| 2L high | Two-lane roads, AADT > 5000 |

| 2L low | Two-lane roads, 2000 < AADT ≤ 5000 |

| Country | Year | MW High | MW Low | 2L High | 2L Low | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 2017 | 15 | 14 | 30 | 30 | 89 |

| 2018 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 29 | 89 | |

| 2019 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 30 | 90 | |

| 2020 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 30 | 90 | |

| 2021 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 30 | 90 | |

| Total | 75 | 74 | 150 | 149 | 448 | |

| Norway | 2017 | 15 | 11 | 50 | 49 | 125 |

| 2018 | 17 | 12 | 58 | 70 | 157 | |

| 2019 | 16 | 13 | 60 | 72 | 161 | |

| 2020 | 15 | 11 | 61 | 72 | 159 | |

| 2021 | 14 | 13 | 60 | 72 | 159 | |

| Total | 77 | 60 | 289 | 335 | 761 | |

| Sweden | 2017 | 35 | 75 | 54 | 186 | 350 |

| 2018 | 24 | 71 | 79 | 197 | 371 | |

| 2019 | 32 | 80 | 86 | 209 | 407 | |

| 2020 | 36 | 76 | 58 | 198 | 368 | |

| 2021 | 36 | 73 | 72 | 198 | 379 | |

| Total | 163 | 375 | 349 | 988 | 1875 |

| Retroreflectivity, RL (mcd/m2/lx) | Denmark | Norway | Sweden |

|---|---|---|---|

| RL ≤ 80 | 1.8% | 4.7% | 1.4% |

| 80 ≤ RL ≤ 100 | 8.3% | 5.9% | 2.7% |

| 100 ≤ RL ≤ 130 | 28.6% | 11.0% | 14.3% |

| 130 ≤ RL ≤ 150 | 23.2% | 13.0% | 15.6% |

| RL ≥ 150 | 38.2% | 65.3% | 66.0% |

| Independent Variable | Degrees of Freedom | Dependent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroreflectivity p-Value | Visibility p-Value | Preview Time p-Value | ||

| Country | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Year | 4 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.296 |

| Road class | 3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Country*year | 8 | 0.203 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Country*road class | 6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Year*road class | 12 | 0.876 | 0.013 | 0.292 |

| Country | Retroreflectivity | Visibility | Preview Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (mcd/m2/lx) | Standard Error (mcd/m2/lx) | Mean (m) | Standard Error (m) | Mean (s) | Standard Error (s) | |

| Denmark | 143.9 | 2.5 | 128.6 | 0.8 | 4.86 | 0.04 |

| Norway | 170.0 | 2.4 | 129.4 | 0.7 | 5.57 | 0.04 |

| Sweden | 166.6 | 1.4 | 122.0 | 0.4 | 4.70 | 0.02 |

| Comparison | Retroreflectivity Difference (mcd/m2/lx) | Visibility Difference (m) | Preview Time Difference (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark–Norway | −26.1 * | −0.8 | −0.71 * |

| Denmark–Sweden | 22.7 * | 6.6 * | 0.16 * |

| Norway–Sweden | 3.4 | 7.4 * | 0.07 * |

| Year | Retroreflectivity | Visibility | Preview Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (mcd/m2/lx) | Standard Error (mcd/m2/lx) | Mean (m) | Standard Error (m) | Mean (s) | Standard Error (s) | |

| 2017 | 156 | 2.7 | 125 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 0.04 |

| 2018 | 158 | 2.7 | 126 | 0.8 | 5.0 | 0.04 |

| 2019 | 158 | 2.6 | 126 | 0.8 | 5.0 | 0.04 |

| 2020 | 171 | 2.6 | 129 | 0.8 | 5.1 | 0.04 |

| 2021 | 159 | 2.6 | 127 | 0.8 | 5.0 | 0.04 |

| Country | Road Class | Retroreflectivity | Visibility | Preview Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (mcd/m2/lx) | Standard Error (mcd/m2/lx) | Mean (m) | Standard Error (m) | Mean (s) | Standard Error (s) | ||

| Denmark | MW high | 129 | 5.8 | 136 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 0.08 |

| MW low | 147 | 5.8 | 134 | 1.8 | 4.4 | 0.09 | |

| 2L high | 139 | 4.1 | 116 | 1.3 | 5.3 | 0.06 | |

| 2L low | 160 | 4.1 | 127 | 1.3 | 5.7 | 0.06 | |

| Norway | MW high | 170 | 5.7 | 143 | 1.8 | 5.5 | 0.08 |

| MW low | 168 | 6.4 | 140 | 2.0 | 5.1 | 0.10 | |

| 2L high | 171 | 2.9 | 118 | 0.9 | 6.2 | 0.04 | |

| 2L low | 171 | 2.7 | 116 | 0.9 | 5.5 | 0.04 | |

| Sweden | MW high | 153 | 3.9 | 142 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 0.06 |

| MW low | 169 | 2.6 | 138 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.04 | |

| 2L high | 159 | 2.7 | 105 | 0.8 | 4.7 | 0.04 | |

| 2L low | 186 | 1.6 | 103 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 0.02 | |

| Road Class | Denmark | Norway | Sweden | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (m2) | Mean Speed Limit (km/h) | Area (m2) | Mean Speed Limit (km/h) | Area (m2) | Mean Speed Limit (km/h) | |

| MW high | 17.0 | 121.5 | 14.6 | 95.8 | 16.7 | 107.5 |

| MW low | 14.2 | 110.8 | 14.4 | 97.0 | 13.4 | 103.3 |

| 2L high | 7.8 | 79.6 | 6.5 | 70.2 | 5.0 | 81.7 |

| 2L low | 10.0 | 80.7 | 6.0 | 76.7 | 3.5 | 82.8 |

| All road classes | 11.1 | 92.1 | 7.7 | 77.8 | 6.9 | 88.8 |

| Country | Share of TEN-T Roads (%) |

|---|---|

| Denmark | 53.2% |

| Norway | 45.7% |

| Sweden | 40.7% |

| All | 43.8% |

| Independent Variable | Degrees of Freedom | Dependent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroreflectivity p-Value | Visibility p-Value | Preview Time p-Value | ||

| Country | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TEN-T | 1 | 0.484 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Country*TEN-T | 2 | 0.015 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Country | TEN-T (Yes/No) | Retroreflectivity | Visibility | Preview Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (mcd/m2/lx) | Standard Error (mcd/m2/lx) | Mean (m) | Standard Error (m) | Mean (s) | Standard Error (s) | ||

| Denmark | Yes | 146.2 | 3.7 | 135.0 | 1.3 | 4.6 | 0.06 |

| No | 145.3 | 3.2 | 119.9 | 1.1 | 5.4 | 0.05 | |

| Norway | Yes | 173.2 | 3.0 | 130.6 | 1.0 | 5.6 | 0.05 |

| No | 169.9 | 2.3 | 116.3 | 0.8 | 5.8 | 0.04 | |

| Sweden | Yes | 168.3 | 2.1 | 133.3 | 0.7 | 4.7 | 0.03 |

| No | 177.2 | 1.4 | 104.9 | 0.5 | 4.6 | 0.02 | |

| TEN-T | Denmark | Norway | Sweden | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (m2) | Mean Speed Limit (km/h) | Area (m2) | Mean Speed Limit (km/h) | Area (m2) | Mean Speed Limit (km/h) | |

| Yes | 14.6 | 113 | 10.4 | 89 | 12.8 | 105 |

| No | 8.6 | 81 | 6.1 | 74 | 4.3 | 84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vadeby, A.; Fors, C. Condition Assessment of Road Markings in Denmark, Norway and Sweden—A Comparison Between Retroreflectivity, Visibility and Preview Time. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12788. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312788

Vadeby A, Fors C. Condition Assessment of Road Markings in Denmark, Norway and Sweden—A Comparison Between Retroreflectivity, Visibility and Preview Time. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12788. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312788

Chicago/Turabian StyleVadeby, Anna, and Carina Fors. 2025. "Condition Assessment of Road Markings in Denmark, Norway and Sweden—A Comparison Between Retroreflectivity, Visibility and Preview Time" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12788. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312788

APA StyleVadeby, A., & Fors, C. (2025). Condition Assessment of Road Markings in Denmark, Norway and Sweden—A Comparison Between Retroreflectivity, Visibility and Preview Time. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12788. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312788