1. Introduction

Automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems are widely used to convert spoken language into text, but in multi-speaker settings, such as physician-patient consultations or interviewer–interviewee dialogues, accurate speaker diarization is required to associate transcribed segments with the correct speaker. Overlapping speech and rapid turn-taking make diarization particularly challenging in these scenarios. There are two main approaches to the diarization problem. The first method analyzes speech recorded with a single microphone and performs diarization using extracted speech features that are specific to each speaker. This approach is not robust to cases in which the voices of both speakers are similar or the tone of the speaker’s voice changes. The second method utilizes the fact that signals from each speaker arrive at a sensor from different directions. The drawback of the spatial approach is that a multi-microphone setup must be used to record speech. The algorithm presented in this paper is based on the latter approach.

Traditional approaches to speaker diarization have relied on statistical methods, such as Gaussian Mixture Models and Hidden Markov Models [

1,

2]. These methods were complex, and their accuracy was limited. Recent advancements in deep learning-based solutions shifted the focus to end-to-end neural speaker diarization (EEND) frameworks, leveraging neural networks to directly optimize diarization tasks without the need for separate modules for feature extraction and clustering [

3,

4,

5]. Transformer-based models have also been introduced to capture long-term dependencies in audio data, significantly improving performance in scenarios with overlapping speech [

6,

7,

8]. Neural diarization is particularly useful in challenging real-world scenarios, where acoustic noise, overlapping speech, and an unknown number of speakers are common [

3,

9]. Speaker diarization is an important part of modern ASR systems and their applications, such as audio indexing, transcription, and speaker identification [

10,

11,

12].

From a methodological perspective, diarization techniques can be categorized into software-based, hardware-based, and hybrid approaches. Software-based approaches predominantly rely on algorithmic advancements and computational models. For instance, x-vector embeddings combined with Probabilistic Linear Discriminant Analysis (PLDA) have become a standard pipeline for speaker segmentation and clustering [

13]. Hardware-based solutions involve the use of multi-microphone arrays or beamforming techniques to spatially separate speakers based on their physical location. Time Difference of Arrival (TDOA) analysis is often employed in such systems to enhance diarization accuracy by exploiting spatial cues [

14,

15,

16]. Hybrid approaches integrate both software and hardware components; for example, combining microphone array processing with neural network-based segmentation has shown significant improvements in noisy environments [

15,

17]. Target-speaker voice activity detection was created for multi-speaker diarization in a dinner party scenario [

18]. Neural diarization algorithms operating on multi-channel signals [

19,

20,

21] and on virtual microphone arrays [

22] were also proposed. Some methods utilize spatial cues from multiple speakers for multi-channel diarization [

23,

24]. Other approaches combine speaker embeddings with TDOA values from microphone sensor arrays [

25,

26].

Despite these advancements, several challenges persist. Handling overlapping speech remains one of the most significant obstacles, particularly in multi-party conversations. The DIHARD Challenge series (2018–2021) established benchmark datasets specifically designed to evaluate diarization performance in challenging real-world scenarios with varying acoustic conditions, unknown numbers of speakers, and substantial overlapping speech [

27,

28]. Recent work has explored overlap-aware diarization models that explicitly predict overlapping segments using multi-label classification frameworks [

7]. Data augmentation techniques, such as adding synthetic noise or reverberation during training, have been widely adopted [

13,

29]. Additionally, self-supervised learning has recently gained traction to leverage large amounts of unlabeled audio data to improve diarization performance [

30]. Systems that adapt to dynamically changing numbers of speakers are another active area of research. Online diarization methods that update speaker models in real time have shown promise but require further refinement [

6,

30].

While recent diarization systems achieve high accuracy in multi-speaker meetings, they typically ignore spatial cues available in compact sensors. Acoustic Vector Sensors (AVS) are small multi-microphone setups that can provide information on the direction of arrival (DOA) of the sound waves [

31]. Therefore, they can be useful in spatial separation of speakers [

32,

33] and in diarization algorithms based on spatial data [

34]. Estimation of the speaker’s DOA may be based on the time-frequency bin selection [

35], the inter-sensor data ratio model [

36], or the inter-sensor data ratio model in the time-frequency domain [

37]. There are also multi-speaker DOA estimation systems based on neural networks, operating on AVS signals [

38,

39]. In contrast to neural or microphone-array diarization approaches, the advantages of employing an AVS include low-cost hardware, small size of the sensor, interpretability, and better overlap detection thanks to utilizing DOA information.

The current (as of late 2025) State-of-the-Art diarization system is Pyannote.audio [

40]. This neural diarization model is often the first choice for speech processing applications, such as the WhisperX ASR system [

41]. The authors of this paper evaluated both systems for speech recognition in a physician-patient interview scenario, and they found two main issues limiting speaker diarization accuracy. First, Pyannote operates on speech features extracted from the signal; it does not utilize spatial information, which can be clearly established in this scenario. As a result, diarization errors related to speaker confusion were frequently observed. Second, Pyannote does not recognize more than one speaker in the overlapping speech segments, which also decreases diarization accuracy.

This study proposes a low-complexity, interpretable diarization algorithm that leverages an AVS to obtain DOA cues from sound intensity. The proposed method exploits DOA information to distinguish speakers and handle overlapping speech without the need for neural training. By moving diarization to a pre-processing stage and using tunable parameters, the method aims to (1) reduce speaker confusion, (2) detect overlapping speech, and (3) remain robust across different voice timbres without requiring training data. The proposed approach was validated on a custom AVS-recorded interview dataset and compared to the Pyannote.audio baseline using multiple DER variants. The details of the proposed algorithm, evaluation of the proposed method, comparison of the obtained results with Pyannote, and discussion of the results are presented in the subsequent sections of the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

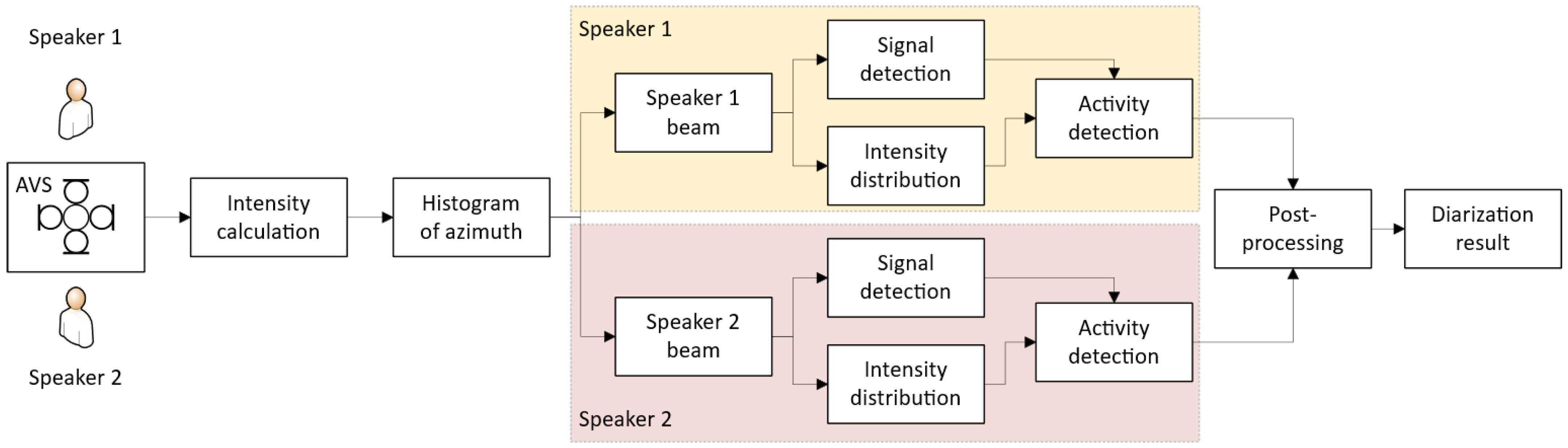

The algorithm for speaker diarization, presented in

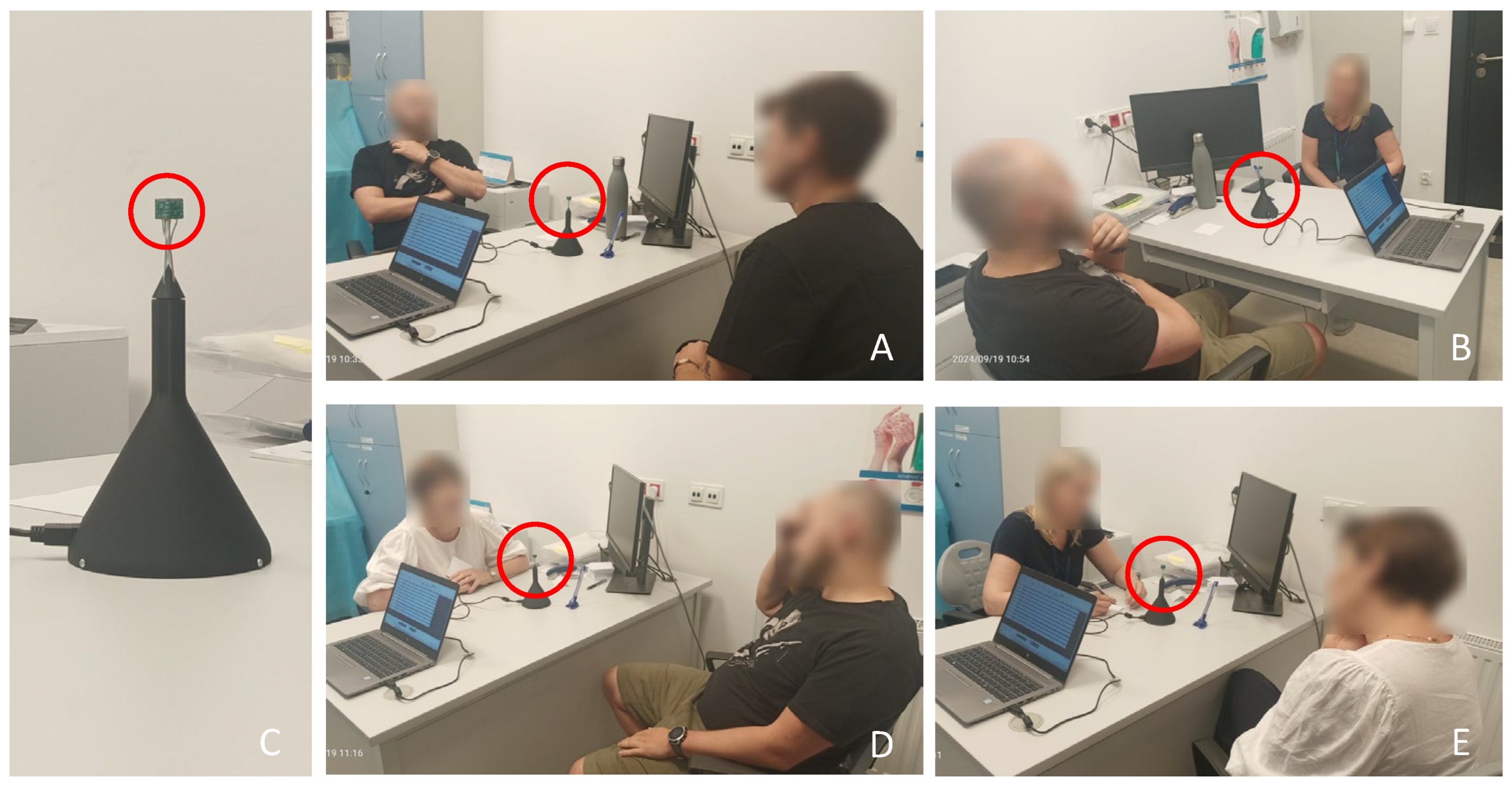

Figure 1, was designed for the following scenario. Two speakers are seated opposite each other in a reverberant room. An AVS is positioned between the speakers. The two speakers conduct an interview, during which they mostly speak in turns (question/answer), but there are also fragments of overlapping speech (both speakers active at the same time). Using the signal recorded with the AVS, the task of the algorithm is to detect signal fragments in which each speaker was active, and to provide a list of indices marking each detected segment together with the speaker label. The proposed diarization algorithm consists of three stages: (1) estimation of dominant DOAs from AVS-derived sound intensity histograms, (2) construction of directional beams centered at the detected azimuths, and (3) per-beam activity detection that classifies blocks as noise, single-speaker, or overlapping speech. The following subsections describe sound intensity computation, DOA estimation, and block-level activity detection.

2.1. Sound Intensity

The proposed algorithm is based on sound intensity analysis, using signals recorded with an AVS, which measures particle velocity along the three axes of a Cartesian coordinate system (X-Y-Z), and sound pressure at the center point of the sensor. Particle velocity is approximated with a pressure gradient, measured with pairs of identical, omnidirectional microphones placed on each axis, at the same distance from the sensor center point. Pressure

px(

t) and particle velocity

ux(

t) on the X axis can be calculated from the signals

px1(

t) and

px2(

t) measured with two microphones placed on this axis (

t denotes time):

Pressure and particle velocity for the Y and Z axes can be calculated using the same approach. Pressure signals obtained for all three axes are averaged to provide a single pressure signal

p(

t).

The pressure and velocity signals are processed in the digital domain. Signal samples are partitioned into fixed-size blocks. Each block is transformed using a Discrete Fourier Transform to obtain frequency-domain spectra. The cross-spectrum between pressure and particle velocity yields the axis-specific sound intensity [

42]. Sound intensity

IX(ω) for the X axis can be computed as:

where ω is the angular frequency,

P(ω) and

UX(ω) are the spectra of the pressure and particle velocity signals, respectively, and the asterisk denotes complex conjugation. Sound intensity in the Y and Z axes is computed the same way. Total sound intensity

I(ω), expressing the amount of acoustic energy measured with the AVS regardless of direction, is calculated as:

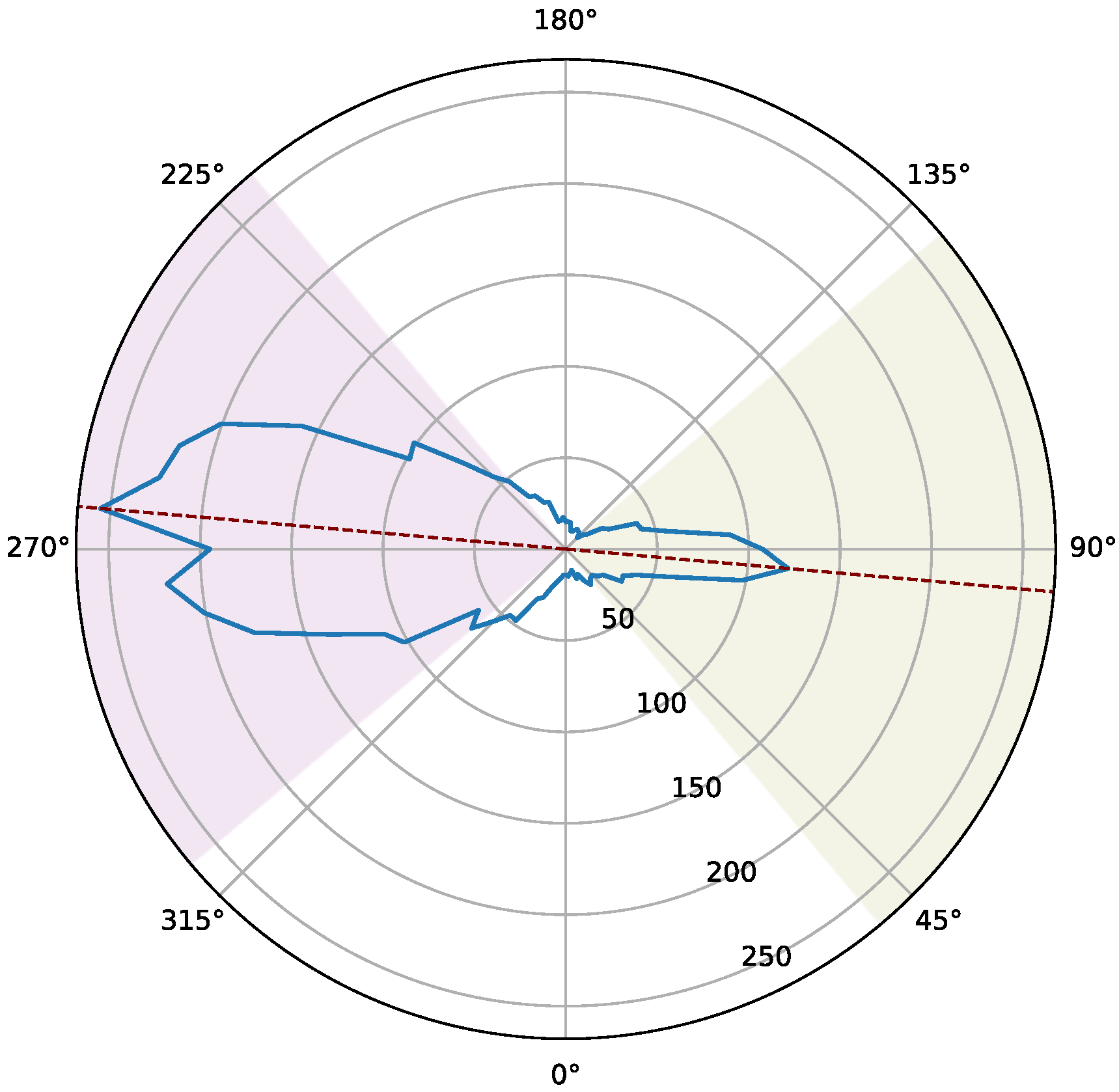

2.2. Detection of Speaker Direction

Sound intensity (calculated with Equations (3) and (4)) is determined for each frequency component of the signal. The DOA of each component in the horizontal plane (X-Y) may be obtained using the equation:

The dominant directions of sound sources within the analyzed block may be found by calculating a histogram of the azimuth

φ(ω) weighted by the total intensity

I(ω). The histogram is calculated by dividing the whole azimuth range 0°–360° into bins of equal width, e.g., 5°. To improve the analysis accuracy, block histograms are averaged within a moving window of size 2

L + 1 blocks. For each histogram bin representing azimuth values (

φmin,

φmax), the bin value

bn is calculated as:

were

n is the current block index,

kmin and

kmax define the frequency range (the spectral bin indices) used for the histogram calculation. In the algorithm described here, the analyzed frequencies are limited to the 93.75–7992 Hz range to focus on speech-dominated content.

The algorithm assumes that the speaker’s position remains approximately constant during the entire recording (small variations are handled by the algorithm). Therefore, histograms calculated for all signal blocks are averaged to form a single histogram for the whole recording. Then, the azimuth of each dominant sound source (each speaker) can be found by extracting local maxima from the histogram. In the algorithm proposed here, the azimuth related to each local maximum becomes the center of a beam: the azimuth range representing a given speaker. The width of the beam may be adjusted according to the distance between each speaker and the sensor, the angular distance between the speakers, etc. In the scenario presented in this paper, the speakers were positioned opposite each other, so that their radial distance was close to 180°. The optimal beam range for this case, found during the experiments, was ±45°. In other scenarios (e.g., multiple speakers), the beam ranges may be determined automatically.

The proposed speaker detection method requires that the histogram peaks related to sound sources (speakers) are clearly distinguishable from the noise. As long as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is sufficient for speech to be audible, the algorithm is able to identify the speakers’ positions.

2.3. Speaker Activity Detection

The final stage of the diarization algorithm analyzes total intensity within the two non-overlapping beams (φlow, φhigh), defined for each speaker, to decide if the block contains no speech, one active speaker, or overlapping speakers. The azimuth ranges (φlow, φhigh) for each beam are determined from the histogram calculated using the procedure described earlier. In the presented experiments, local maxima of the histogram related to the speakers were used as the beam centers, and the ranges were set to ±45° around the center azimuth. It is also possible to find the optimal azimuth ranges instead of using fixed-width beams, using the calculated azimuth histogram.

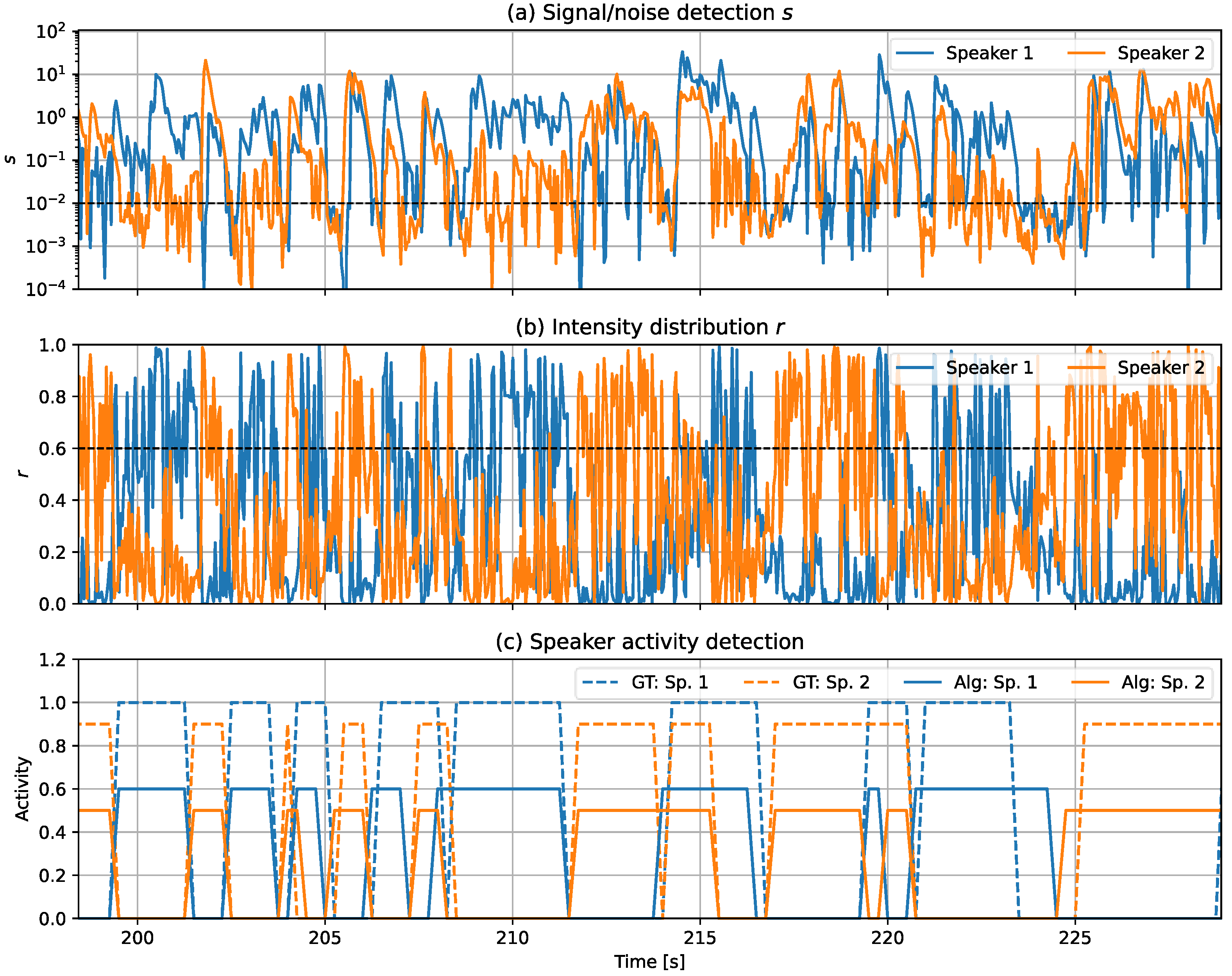

The analyzed signal is segmented the same way as before. In each block, a decision is made whether there is no speaker activity, one speaker is active, or both speakers are active. The decision is made based on two criteria. The first one determines whether a block contains speech or noise, in each beam separately. The second criterion tests sound intensity distribution between the beams for overlapping speech.

For each signal block, a sum of total intensity for all analyzed spectral components having the azimuth within the beam (

φlow,

φhigh) is calculated:

where

n is the block index, and the range (

kmin,

kmax) is defined as before. The calculation is performed for each beam separately. Values of

en are then normalized by the mean value calculated for all blocks that contain sufficient sound intensity, discarding blocks containing only noise. A mask

ξn is calculated:

where

emin is a fixed threshold for the preliminary signal-noise detection. Next, a signal detection metric

sn is calculated:

where

N is the number of analyzed blocks. The

sn values calculated for all blocks are then smoothed using exponential averaging.

The decision whether the analyzed block contains a signal is made using the condition: sn > smin. The threshold values emin and smin should be higher than the noise level observed in the analyzed signal. They may be estimated by applying Equations (7) and (9) to a recording containing only noise. If these thresholds are set too high, the risk of misclassifying blocks containing speech as noise increases.

If a signal is detected in only one of the beams, this beam is marked as active, and the other one as inactive. If a signal is not detected in any beam, the block is marked as inactive (noise) for both beams. However, if a signal is detected in both beams, an additional condition is checked to decide whether the block contains overlapping speech. For this purpose, intensity distribution between the beams is calculated using the ratio

rn of the beam intensity to the whole range intensity:

The value rn represents normalized sound intensity contained within the beam (0 to 1). This value is compared with the threshold rmin, which should be larger than 0.5 (in the experiments: rmin = 0.6). If the condition rn > rmin is fulfilled for only one beam, this beam is marked as active (most of the sound intensity is concentrated within this beam), and the other one as inactive. If this condition is not met for any beam, which suggests almost equal distribution of sound intensity between two beams containing a signal, both beams are marked as active (overlapping speech).

After the processing, each block is marked as active or inactive for each beam (activity means speech presence). The final step of speaker diarization performs post-processing of the block decisions, merging the sequences of active blocks separated by gaps smaller than the minimum allowed gap, and removing active block sequences that are too short. The obtained result consists of time indices of signal fragments with the detected speaker activity, for each speaker separately.

2.4. Automatic Tuning of Threshold Values

The threshold values

emin,

smin, and

rmin are the tunable parameters of the algorithm, affecting its accuracy. The first two thresholds should be adjusted to the noise level observed in the recordings. In the experiments presented here, threshold values were found empirically, as described in

Section 3.2. For

emin and

smin, initial values can be estimated with a simple statistical analysis of the signal energy, and then the threshold may be tuned manually to improve the algorithm’s performance.

Total signal energy in each signal block can be computed as:

A histogram of

En values obtained from all blocks is calculated using the logarithmic scale. Two distinct peaks should be visible in the histogram: one for speech and another for noise. Next, a cumulative distribution function (cdf) is computed from the histogram. The value at which the cdf reaches 0.95 is selected as the

emin threshold. The choice of the 95th percentile is the standard in noise analysis, related to the 95% confidence interval in statistical analysis. The second threshold

smin can then be calculated using a modified Equation (9):

where

ξn is defined in Equation (8).

The threshold value rmin is related to the energy distribution between the two beams. This value should typically be within the 0.5–0.6 range. The value 0.6 used in the experiments is a sensible default choice. It may be adjusted if significant errors are observed in overlapping speech segments.

4. Discussion

The dataset recorded by the authors was used to evaluate the performance of both the proposed diarization algorithm and the reference system, Pyannote. These two systems utilize different approaches to the speaker diarization problem. The proposed algorithm is based on the spatial distribution of sound intensity originating from different speakers, analyzed in signals recorded with an AVS. Pyannote is a solution based on deep neural networks that extracts speaker features from signals recorded with a single microphone. Performance of both methods was assessed using the DER metric, in four variants of the DER calculation method, differing in the way the overlapping speech fragments are considered. Across all DER variants, the proposed AVS-based method consistently outperformed the Pyannote baseline. Overall DER for the proposed algorithm ranged from 0.10 to 0.19 versus 0.19 to 0.23 for Pyannote; the largest gains were observed in reduced speaker confusion and higher correct-detection rates when spatial information is informative.

In Variant A, in which only the signal fragments not containing overlapping speech were included in DER calculation, the proposed algorithm yielded lower DER scores than the reference system. It was observed that in the absence of overlapping speech, Pyannote tends to detect the wrong speaker much more frequently than the proposed method, which is probably caused by the similarity of speech features of both speakers. The proposed algorithm is based on spatial information, so it is robust to such issues. The evaluated algorithm provided slightly more false detections, resulting mostly from detecting speaker activity slightly outside the speaker segment (sustaining the speaker detection after the speaker activity ended). However, for speech recognition purposes, lower MD values are more important than lower FD values.

Variant B included signal fragments in which both speakers were active at the same time, requiring that at least one speaker be recognized correctly. The overall results are slightly better than for Variant A. The differences between the proposed algorithm and the reference system are consistent with those from Variant A. These results confirm that both methods handle the overlapping speech fragments correctly if only a single speaker (either one) needs to be detected.

Variant C required that both speakers be detected within the overlapping speech fragments. With this approach, the evaluated algorithm produced a higher DER than the previous variants, which was expected. Speaker diarization in the case of overlapping speech is a difficult problem, so there is a large increase in the number of confused speaker errors. However, the obtained DER value is satisfactory for the described scenario, and it is still lower than the DER obtained for the reference system in Variant A (without overlapping speech). The Pyannote system cannot operate in this Variant, because by design, it only detects a single speaker.

Variant D differed from Variant B in that, in the overlapping speech fragments, it required that the detector sustain its decision when an overlapping speech segment begins. Both the proposed algorithm and the reference system exhibited similar differences in results (D vs. B). The experiments performed during the research may indicate that Pyannote’s diarization system operates in the overlapping speech cases using this approach, although it was not confirmed.

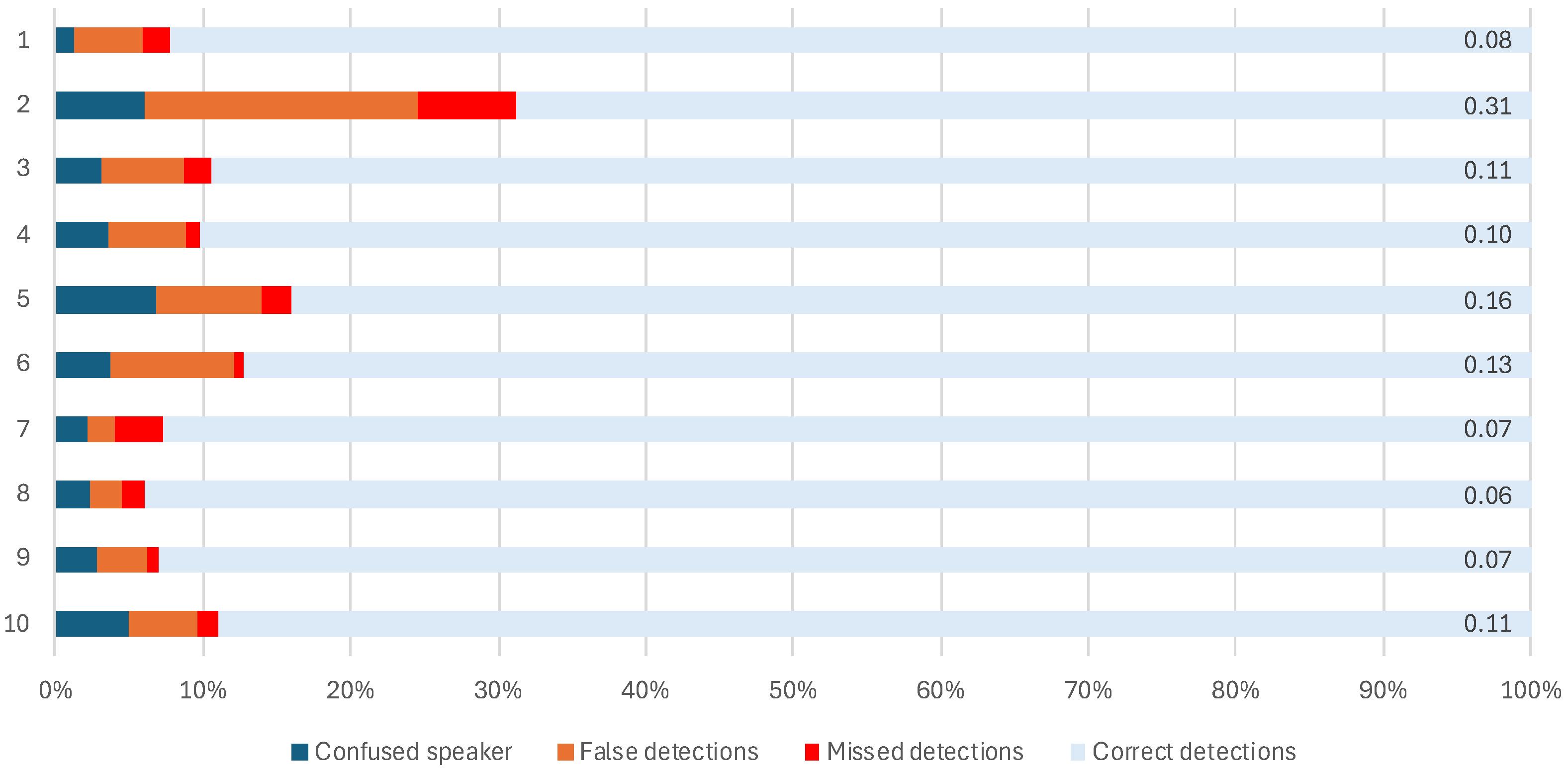

Comparison of the results obtained for the individual recordings (

Figure 5) indicates that the distribution of results is similar in most of the recordings. As expected, there is no correlation between the persons participating in the recording (male/female voices,

Table 1) and the obtained results. The recording #2 produced a significantly higher DER (0.31) than the other ones. This was the only recording in which one of the speakers was located further from the sensor (more than 2 m away). This resulted in a lower signal-to-noise ratio for this speaker, and consequently, a higher percentage of false detections (19%). However, the FD errors (noise detected as speech) are less critical for speech recognition than the other types of errors, although they increase the risk of hallucinations from the ASR model. The algorithm accuracy in cases like this may be improved by better selection of the threshold values. Automatic calculation of the optimal algorithm parameters is left for future research.

The results of the experiments may be summarized as follows. The proposed algorithm for speaker diarization using AVS and sound intensity analysis provides a satisfactory accuracy of speaker diarization, both without and with overlapping speech fragments. It outperformed Pyannote in the interview scenario with two speakers seated opposite each other, as confirmed with lower DER scores across all analyzed variants. These improvements stem from leveraging DOA cues that disambiguate similar voice timbres and help sustain speaker decisions during rapid turn-taking or partial overlaps. In contrast, single-channel neural models rely mainly on spectral features and require source-separation modules or overlap-aware architectures to fully resolve concurrent speakers.

Both approaches: the algorithmic one, based on spatial information, and the machine learning approach, based on speaker features, have practical advantages and disadvantages. The current State-of-the-Art systems, such as Pyannote, operate on signals obtained with a single microphone, and they provide a complete, end-to-end solution for speech diarization and recognition. However, these systems are unable to handle overlapping speech unless they are supplemented with a source separation model. The source separation problem is complex, and it is outside the scope of this paper. In comparison, the proposed approach performs only the diarization stage (speech recognition is still performed with an external ASR system), and it requires a specific sensor (which, however, is a low-cost and small-sized device). The main advantage of the proposed algorithm is that it is robust to the similarities in speech features from the speakers, as it operates on spatial information obtained from the sound intensity analysis. As long as there is sufficient azimuth difference between the speakers (as is the case in the presented interview scenario), accurate speaker diarization is possible even in the case of overlapping speech. This is evident when comparing the number of CS results: 11.9% for the proposed algorithm with overlapping speech, and 14.9% for the reference system without overlapping speech. The proposed method is independent of speaker features, such as age, gender, manner of speech, spoken language, etc. Another advantage of the proposed method is that the obtained spatial information can be used to perform speaker separation. While this aspect is outside the scope of this paper, the previous publication [

33] has shown that this approach allows for the separation of overlapping speech into streams of individual speakers, with sufficient accuracy. Additionally, the algorithm proposed in this paper contains parameters that can be tuned to improve its accuracy and to adapt the algorithm to acoustic conditions in the room. The reference system is a ‘black box’ approach, without the possibility of altering its function. Lastly, the proposed method is easy to implement, and it does not require a large dataset to train the diarization system.

This paper focuses on an interview scenario with two speakers seated opposite each other, and the sensor placed between them. The dataset presented in this manuscript was created to evaluate this specific scenario. However, other tests performed by the authors indicate that the proposed algorithm can also work correctly in different speaker configurations. In the previous publication [

33], it was shown that in a simulated environment, the algorithm based on AVS can separate sound sources if the azimuth distance between two speakers is at least 15°. Tests performed in real reverberant rooms showed that the required azimuth distance between two speakers is at least 45°. Therefore, the proposed algorithm is expected to work correctly with two speakers at a radial distance of 45° to 180°. Additionally, the speaker detection algorithm can detect more than two peaks in the histogram, so it can also work correctly in a multi-speaker scenario, if the distance between each pair of speakers is at least 45°. The authors performed tests with two speakers seated near each other at the same side of the table, with four speakers seated around a table, etc., and the detection procedure worked as expected. The speaker activity detection algorithm needs to be extended to handle more than two beams. However, these scenarios require different test recordings for their validation. Therefore, the authors decided to focus on a specific scenario in this paper, and other scenarios are left for future publications.

In terms of computational complexity, the proposed algorithm is relatively simple. In the algorithm used for testing, processing each block of 128 samples of a six-channel sensor signal required applying seven digital filters of length 512 each to perform the correction of microphone characteristics [

44], then computing the forward and the inverse Fourier transforms (FFT and IFFT) of length 2048 and computing the histogram; the remaining operations are simple mathematical ones. Unlike the machine learning approaches, such as Pyannote, which require powerful hardware to run, the proposed algorithm can run on low-power hardware, such as a Raspberry Pi.

Limitations of the current study include the assumption of approximately stationary speakers and the interview geometry (opposite seating). Recording #2, where one speaker was >2 m away, illustrates sensitivity to noise; better parameter selection or automatic tuning could mitigate this. The case of a speaker moving during the recording may be handled by performing the speaker detection procedure in shorter segments (e.g., 3 s long) and applying a source tracking procedure. Further evaluation of the algorithm is also needed, including test recordings with a larger number of speakers, varying distance between the speakers and the sensor, speech recorded in varied acoustic environments, with different SNR, various noise types, etc. Future work should address moving speakers, more than two concurrent talkers, improved automatic parameter tuning, integration with source separation to support end-to-end ASR, and testing the algorithm in different acoustic conditions, with different speaker configurations.

5. Conclusions

The results of the experiments performed on the custom dataset indicate that the proposed diarization algorithm based on AVS works as expected, and the obtained DER scores are better than in the reference system. The proposed approach reduced the number of substitution errors observed in the reference system, occurring when two speakers were active concurrently or there was a rapid transition between the speakers. These situations may also lead to transcription errors. The proposed method employs an additional modality (DOA analysis) to improve the diarization accuracy. The presented algorithm does not require training, it is not based on speaker profiles, and it does not depend on the characteristic features of a speaker or a manner of speaking. Additionally, it can be used to detect overlapping speech and to perform speaker separation before the pre-processed signals are passed to an ASR system. Thanks to that, the efficiency of a system for an automatic speech transcription of a dialogue may be improved. This is important for practical applications, such as a speech-to-text system for automatic documentation of medical procedures in a physician-outpatient scenario. Practically, AVS-based diarization is attractive for compact, low-cost hardware that requires interpretable spatial cues and minimal training. By operating as a pre-processing module, it can reduce diarization errors that would otherwise propagate into downstream ASR transcripts.

In this paper, a scenario in which two speakers at constant positions participated in a dialogue was presented. The proposed method may be generalized for a larger number of speakers, who may be active concurrently, and who may change their position. To realize this goal, the algorithm must be supplemented with source tracking and speaker separation algorithms. Additionally, a voice activity detector may be added to discard sounds not related to speech, which may reduce the error rate even further. Moreover, automatic tuning of the algorithm parameters may help reduce diarization errors when there is a large difference in loudness between the speakers. These issues will be the topic of future research.