Extending Light Direction Reconstruction to Outdoor and Surface Datasets

Abstract

1. Introduction

- fr = bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF);

- Li = incident light radiance;

- x = location to be lit;

- ωi/ωo = incident/outgoing light direction;

- Ω = entirety of ωi from the hemisphere above x.

- Improvement of reconstruction error to on reference test data via FCDN architecture.

- Publishment of a labelled outdoor dataset suitable for illumination reconstruction that can be further expanded in the future.

- Demonstration of the presented architecture’s ability to generalise to real scenarios (with rudimentary domain adaptation).

- Investigation on whether multimodal (RGB-D, RGB-N) network architectures have any effect on the reconstruction performance.

2. Related Work

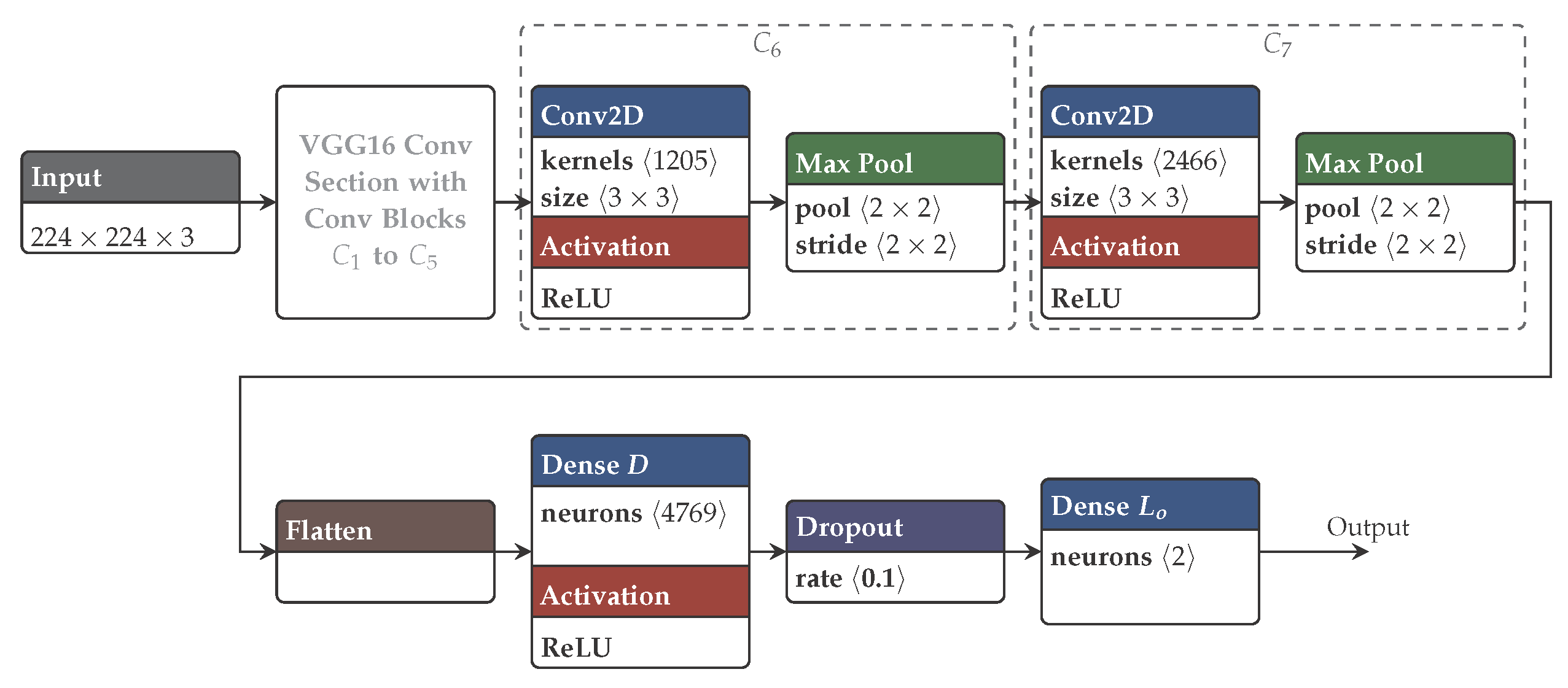

3. FCDN Evaluation on RGB Data

4. Real-World Generalisation

4.1. Recording Setup

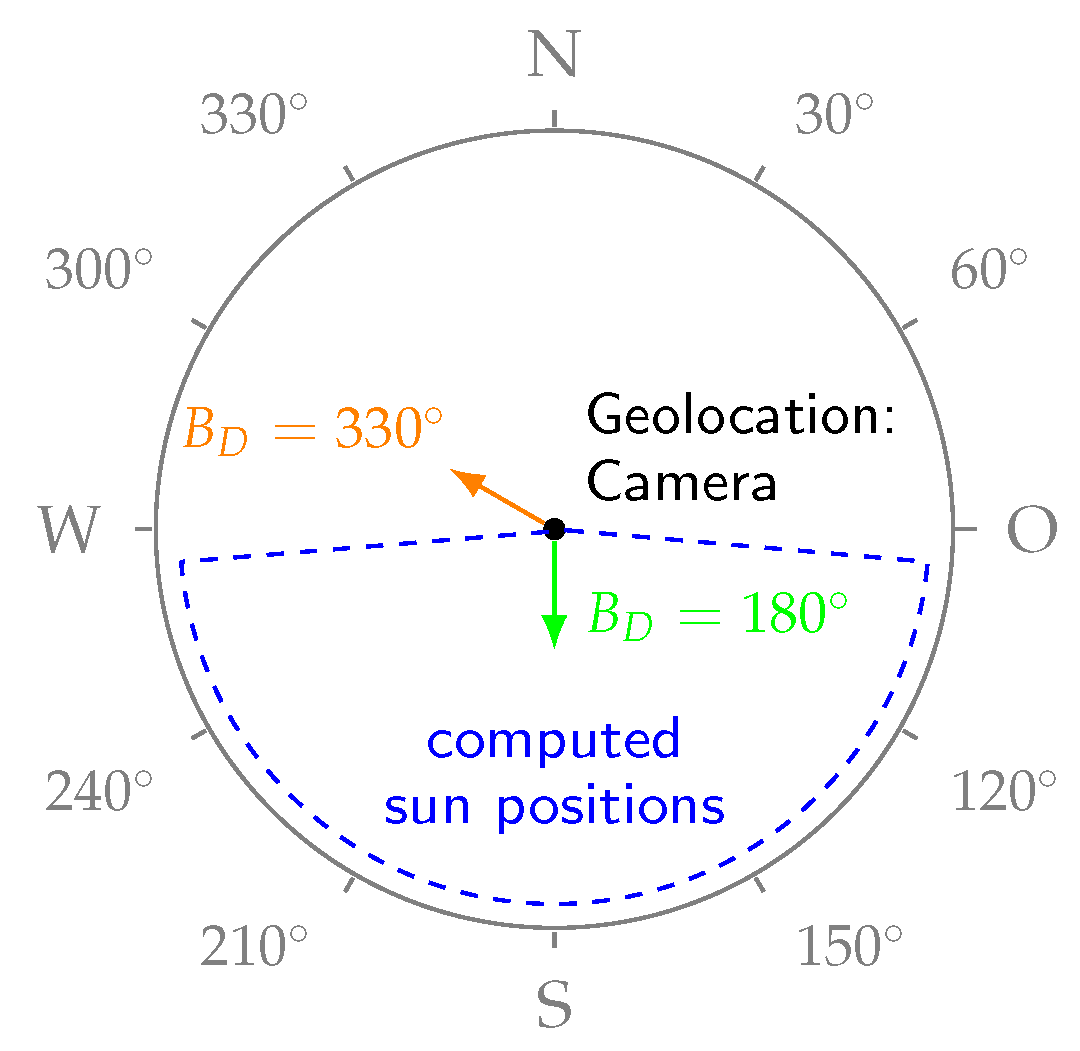

4.2. Labelling Outdoor Photographs

4.3. Evaluation Strategy

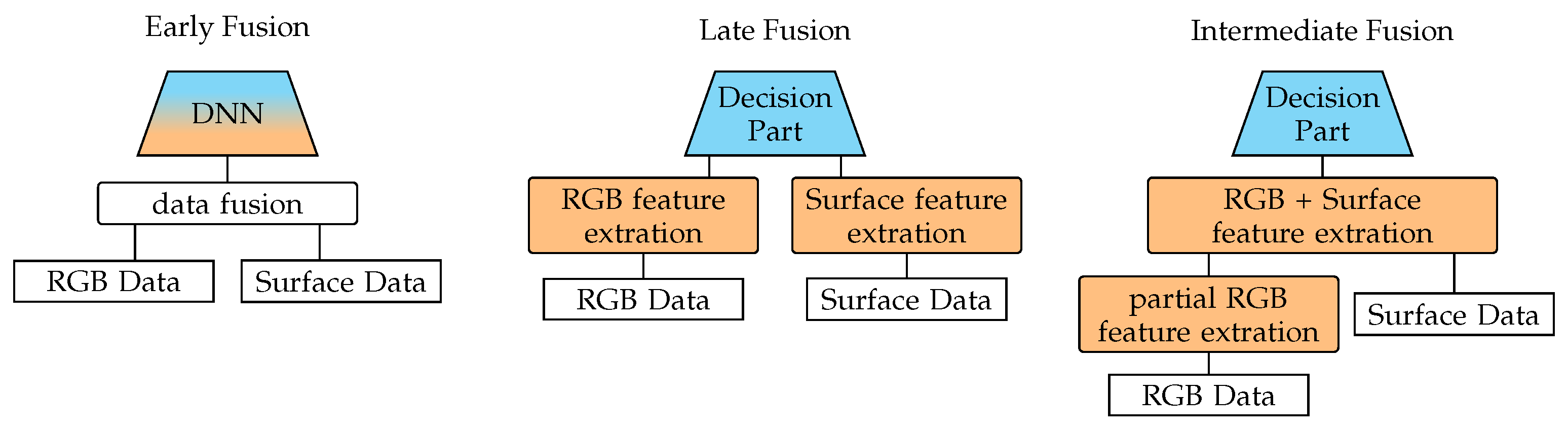

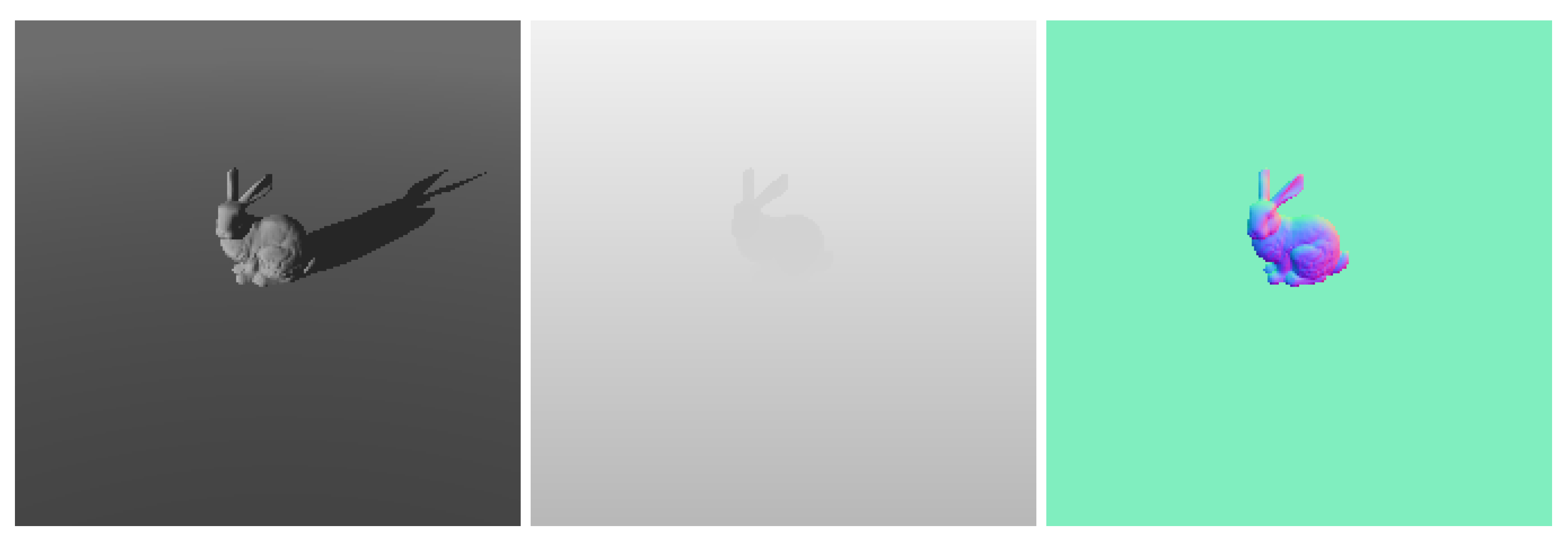

5. Influence of Surface Data

5.1. Fusing Data

5.2. Training with RGB-D and RGB-N

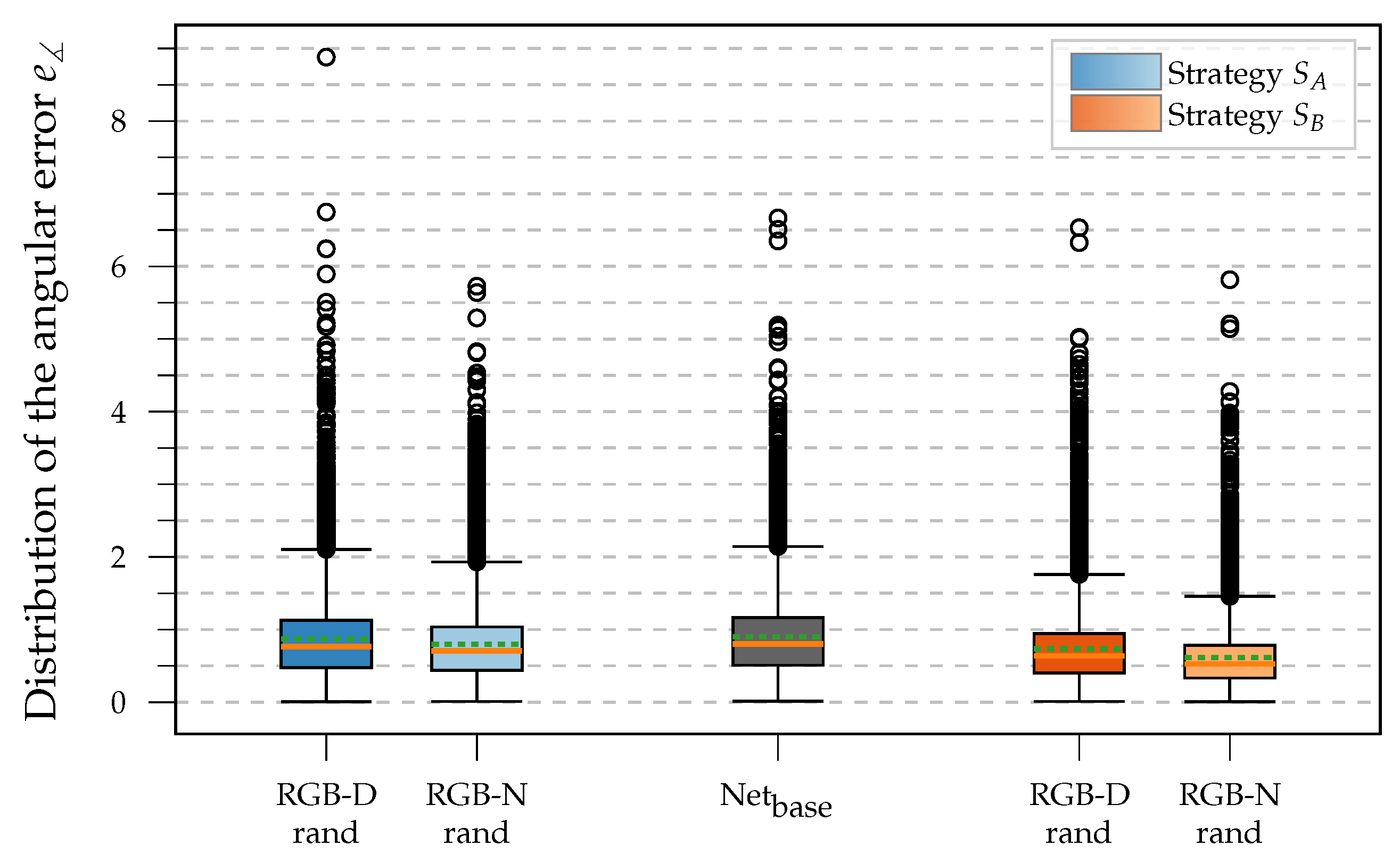

5.3. Statistical Investigation

6. Results

6.1. Results: FCDN Architecture

6.2. Results: Outdoor Data Generalisation

6.3. Results: Effects of Surface Data

7. Discussion

Summary

8. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | augmented reality |

| BRDF | bidirectional reflectance distribution function |

| DNN | deep neural network |

| FCDN | fully convolutional dense network |

| FCN | fully convolutional network |

| GPS | global positioning system |

| IBL | image-based lighting |

| LFAN | linear feature aggregation network |

| NIR | near-infrared |

| ReLU | rectified linear unit |

| RGB | red-green-blue |

| RGB-D | red-green-blue-depth |

| RGB-N | red-green-blue-normal |

| XAI | explainable artificial intelligence |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Reconstruction Performance of Recent Architectures

| DNN | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. | Avg. Time | Avg. | Avg. Time | Avg. | Avg. Time | Avg. | Avg. Time | |

| ≈6 ms | ≈2 ms | ≈2.5 ms | ≈3.5 ms | |||||

| ≈17 ms | ≈6 ms | ≈7 ms | ≈9.5 ms | |||||

| ≈33.1 ms | ≈12.1 ms | ≈14.2 ms | ≈18 ms | |||||

| ≈54.6 ms | ≈22.5 ms | ≈25.5 ms | ≈32.6 ms | |||||

Appendix A.1.1. ResNet50sx,sy Details

Appendix A.1.2. ConvNeXt-Tsx,sy Details

Appendix A.1.3. ConvNeXt-Bsx,sy Details

Appendix A.1.4. Comparison Conclusion

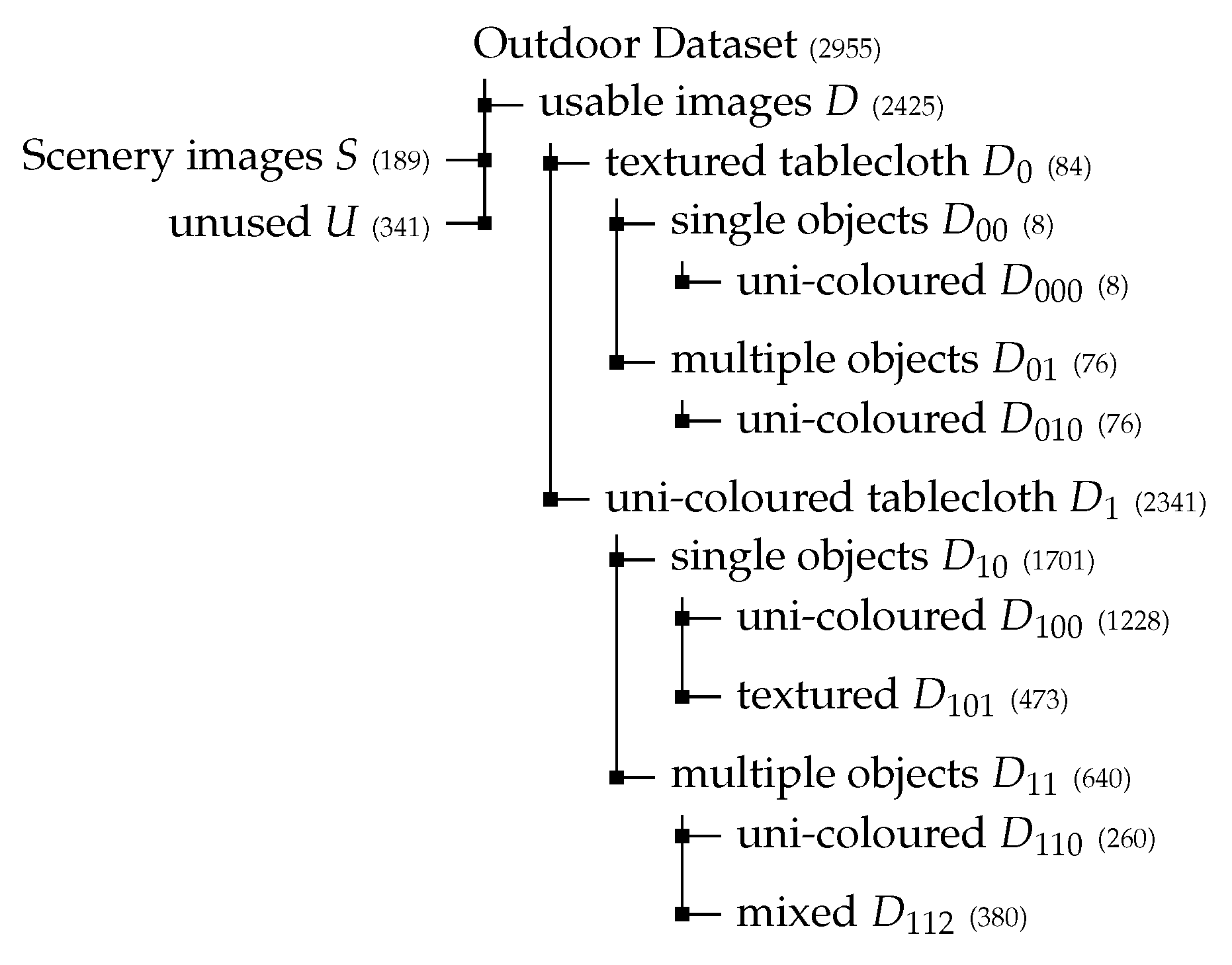

Appendix A.2. Outdoor Dataset Material

Appendix A.2.1. Computation of Bearing

Appendix A.2.2. Ground Truth Error Estimation

Appendix A.2.3. Dataset Organisation

Appendix A.3. Supplementary Math

Appendix A.3.1. Azimuth Label Adjustment

Appendix A.3.2. Packing Operation for Normals

Appendix A.3.3. Effect Size Classification

| small | |

| medium | |

| large |

Appendix A.4. Supplementary Results

FCDN Architecture Results

| Synthetic Contribution | Base Weights | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ImageNet | |||

References

- Kanbara, M.; Yokoya, N. Geometric and photometric registration for real-time augmented reality. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, Darmstadt, Germany, 1 October 2002; pp. 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kán, P.; Kaufmann, H. DeepLight: Light Source Estimation for Augmented Reality using Deep Learning. Vis. Comput. 2019, 35, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Nischwitz, A.; Westermann, R. Deep Light Direction Reconstruction from single RGB images. In Proceedings of the 29 International Conference in Central Europe on Computer Graphics, Visualization and Computer Vision: Full Papers Proceedings, Plzen, Czech Republic, 17–21 May 2021; Computer Science Research Notes. pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015: Conference Track Proceedings, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Ronczka, S.; Nischwitz, A.; Westermann, R. Light Direction Reconstruction Analysis and Improvement using XAI and CG. Comput. Sci. Res. Notes 2022, 3201, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiya, J.T. The Rendering Equation. SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph. 1986, 20, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandram, D.; Taylor, G.W. Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2017, 34, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11966–11976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.A.; Sunkavalli, K.; Yumer, E.; Shen, X.; Gambaretto, E.; Gagné, C.; Lalonde, J.F. Learning to Predict Indoor Illumination from a Single Image. ACM Trans. Graph. 2017, 36, 176:1–176:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, M.; Sunkavalli, K.; Hadap, S.; Carr, N.; Lalonde, J. Fast Spatially-Varying Indoor Lighting Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 6901–6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.A.; Hold-Geoffroy, Y.; Sunkavalli, K.; Gagné, C.; Lalonde, J.F. Deep Parametric Indoor Lighting Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7174–7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hold-Geoffroy, Y.; Sunkavalli, K.; Hadap, S.; Gambaretto, E.; Lalonde, J. Deep outdoor illumination estimation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hold-Geoffroy, Y.; Athawale, A.; Lalonde, J.F. Deep Sky Modeling for Single Image Outdoor Lighting Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 6920–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeGendre, C.; Ma, W.C.; Fyffe, G.; Flynn, J.; Charbonnel, L.; Busch, J.; Debevec, P. DeepLight: Learning illumination for unconstrained mobile mixed reality. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2019, Talks, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 28 July–1 August 2019. SIGGRAPH 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, A.; Schwanecke, U.; Schömer, E. Real-time Light Estimation and Neural Soft Shadows for AR Indoor Scenarios. J. WSCG 2023, 31, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, M.; Nayar, S.K. Generalization of Lambert’s Reflectance Model. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 19–23 July 1994; SIGGRAPH ’94. pp. 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.L.; Torrance, K.E. A Reflectance Model for Computer Graphics. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Dallas, TX, USA, 3–7 August 1981; SIGGRAPH ’81. pp. 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boksansky, J.; Wimmer, M.; Bittner, J. Ray Traced Shadows: Maintaining Real-Time Frame Rates. In Ray Tracing Gems: High-Quality and Real-Time Rendering with DXR and Other APIs; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keras Tuner, Version 1.4.7. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/keras-team/keras-tuner (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Uchiyama, H.; Nagahara, H.; Taniguchi, R.I. Estimating Surface Normals with Depth Image Gradients for Fast and Accurate Registration. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on 3D Vision, Lyon, France, 19–22 October 2015; pp. 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Fu, L.; Majeed, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, R.; Cui, Y. Improved Kiwifruit Detection Using Pre-Trained VGG16 with RGB and NIR Information Fusion. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Notes on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Origin | Test | Training/Validation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ↦ | (701) | (1000) | |

| ↦ | (195) | (278) | |

| ↦ | (506) | (722) | |

| ↦ | (200) | (440) | |

| ↦ | (80) | (180) | |

| ↦ | (120) | (260) |

| on | Base Weights | |

|---|---|---|

| ImageNet | ||

| LFAN | ||

| FCN | ||

| ImageNet | ||

| DNN | S | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

| RGB-D | < | |||

| RGB-N | < | |||

| RGB-D | < | |||

| RGB-N | < |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miller, M.; Arzt, J.; Nischwitz, A.; Westermann, R. Extending Light Direction Reconstruction to Outdoor and Surface Datasets. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12779. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312779

Miller M, Arzt J, Nischwitz A, Westermann R. Extending Light Direction Reconstruction to Outdoor and Surface Datasets. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12779. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312779

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiller, Markus, Johannes Arzt, Alfred Nischwitz, and Rüdiger Westermann. 2025. "Extending Light Direction Reconstruction to Outdoor and Surface Datasets" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12779. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312779

APA StyleMiller, M., Arzt, J., Nischwitz, A., & Westermann, R. (2025). Extending Light Direction Reconstruction to Outdoor and Surface Datasets. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12779. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312779