1. Introduction

Frost heave, a pervasive geotechnical phenomenon in cold regions, induces severe deformation and instability in subgrade and foundation structures, posing critical challenges to infrastructure durability. Foundational studies [

1,

2,

3] established that water migration toward the freezing front occurs under combined thermal and hydraulic gradients, promoting ice lens formation. Subsequent mechanical analyses introduced stress-related considerations, where Hopke [

4] proposed that frost heave initiates once ice pressure exceeds overburden pressure, while Lai et al. [

5] and Ming et al. [

6] demonstrated that new ice lenses form when neutral stress surpasses the sum of overburden and tensile stresses. Experimental validation by Tian and Liu [

7] confirmed that external static and dynamic loads effectively suppress frost heave in fine-grained soils. Similarly, the PCHeave model proposed by Sheng et al. [

8] elucidated that overburden pressure mitigates frost heave by thickening the frozen fringe and inhibiting ice lens propagation.

As research advanced, attention shifted from fine- to coarse-grained soils due to their relevance in modern railway and highway subgrades. Wang et al. [

9] identified moisture content as the dominant factor influencing the frost heave of graded crushed rock, while Wang et al. [

10] developed a multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS) model to predict the frost susceptibility of gravelly soils, integrating fines content, compaction degree, and stress level. At the microscale, Zhang et al. [

11] revealed a previously unrecognized water migration mechanism independent of ice segregation, demonstrating that even non-frost-susceptible soils can exhibit water accumulation near the freezing front. In parallel, Guo et al. [

12] established a micro frost heave model for porous rocks using Discontinuous Deformation Analysis (DDA), emphasizing the influence of pore structure and water saturation on ice crystallization and mechanical degradation.

Further progress in constitutive and numerical modeling has enhanced the ability to simulate frost-induced deformation under field conditions. Liu et al. [

13] developed a thermo–hydro–mechanical (THM) coupled model for unsaturated frozen soils capable of capturing both frost heave and thaw settlement processes in permafrost subgrades. Zhang et al. [

14] introduced a frost heave pressure evolution model for fractured rocks under cyclic freeze–thaw conditions, highlighting the roles of fracture geometry and material deterioration. Moreover, Zhang et al. [

15] investigated slab track deformation subjected to uneven frost heave and thermal gradients, concluding that short-wavelength frost heave, combined with temperature differentials, accelerates stiffness degradation and interlayer debonding. Field analyses by Wu et al. [

16] further revealed that frost heave is most pronounced in intermountain basins and predicted that the antifreeze layers in railway subgrades could become increasingly frost-sensitive over the next three decades. Additionally, Hao et al. [

17] demonstrated that hydraulic pressure significantly exacerbates frost heave in coarse-grained soils by amplifying pore water pressure gradients, underscoring the necessity of hydraulic regulation in subgrade design.

Concurrently, research on material innovation has sought to enhance sustainability and mechanical resilience in cold-region engineering. Lu et al. [

18] introduced a sisal fiber–geopolymer stabilized silty clay (FGSS), which not only strengthened soil and reduced frost deformation after freeze–thaw cycles but also lowered carbon emissions, providing a green and effective alternative for frost mitigation. Xia et al. [

19] complemented this by exploring the nonuniform frost heave of saturated rocks under cyclic freezing, finding that temperature gradients induce irreversible plastic deformation—a critical factor for evaluating slope stability and underground structure safety.

Although extensive studies have examined frost heave and freezing characteristics of fine-grained soils, research on coarse-grained materials—especially those used in high-speed railway (HSR) subgrades—remains limited. Existing studies on coarse-grained soils typically focus on static loading or closed-system freezing conditions, and therefore cannot fully capture the coupled hydraulic–mechanical behavior that occurs under realistic field environments. In particular, previous work seldom considered the presence of external water supply, which is common in seasonally frozen regions due to infiltration, groundwater rise, or thaw–freeze cycling. As a result, the combined effects of dynamic train loading and contrasting hydraulic boundary conditions (open versus closed systems) on the development of frozen depth, frost heave, and internal water redistribution are still not well understood.

To address these gaps, this study systematically investigated the freeze–thaw behavior of a representative coarse-grained Group A subgrade soil under controlled static and dynamic loading while comparing open and closed water-supply systems. The experimental program integrates deformation monitoring, thermal profiling, and post-test water-content measurements to provide a comprehensive characterization of the coupled hydro–thermal–mechanical processes. The novelty of this work lies in (i) quantifying the interplay between cyclic dynamic loading and frost heave development in coarse-grained HSR subgrade soils, (ii) explicitly contrasting open- and closed-system freezing to reveal the role of external water supply on freezing front evolution, frozen depth, and water migration, and (iii) providing mechanistic insights into how loading regime and hydraulic boundary conditions jointly influence frost susceptibility. These contributions fill an important gap in the literature and provide experimental evidence relevant to the design and performance evaluation of coarse-grained subgrades in seasonally frozen regions.

It should be noted that although the cooling and heating boundaries were designed to approximate a one-dimensional thermal condition, minor lateral heat losses through the sidewalls are unavoidable. Therefore, the one-dimensional assumption used in this study represents an idealized dominant heat-transfer mode rather than a strict boundary condition. This clarification is important when interpreting the transition stage of freezing and the stabilization of frost heave.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Properties

The coarse-grained soil used in this study was collected from a subgrade section of the Shenyang–Dandong High-Speed Railway, located in Benxi City, Liaoning Province, northeastern China. This region is characterized by a continental monsoon climate in the northern temperate zone, with an annual mean temperature of 7.4 °C and an average annual precipitation of 821 mm. Winter typically lasts from November to March, and the fifty-year average minimum temperature is −10.3 °C.

Coarse-grained soils with low fines content are widely adopted as anti-frost filling materials in cold-region railway subgrades. These materials include graded crushed rock for the surface layer and Group A, B, and C soils for the lower layers, as specified in the Code for Design of the Newly 200–250 km/h Dedicated Passenger Railway Line in China. The definitions and gradation characteristics of these soil groups are summarized in

Table 1.

The soil used in this study, consisted primarily of well-graded medium to coarse sand and fine to coarse gravel with a fines content below 5%. The particle-size distribution curve is shown in

Figure 1, and a typical photograph of the soil sample is presented in

Figure 2. According to the Code for Designs of the Newly 200–250 km Dedicated Passenger Railway Line in China, the soil is classified as Group A soil.

To eliminate ambiguity and ensure consistency with the design specification, it is clarified that all laboratory specimens in this study were prepared with a controlled fines content of 8%. Although the natural Group A material collected from the field contained fines slightly below 5%, the Chinese railway design specification (

Table 1) permits fines contents in the range of 5–15% for well-graded Group A coarse-grained soil. Accordingly, silty clay fines extracted from the original subgrade material were reintroduced into the mixture to achieve a representative fines content of 8%. This value falls within the specification-defined range for Group A soil and reflects realistic in-service conditions, where fines may accumulate due to construction disturbance or particle breakage.. The physical parameters of the fine fraction are provided in

Table 2.

The fine fraction (particle size < 0.075 mm) used in the frost-heave tests consisted of silty clay with a liquid limit of 29 % and a plastic limit of 21.2 %, corresponding to a material with strong frost-susceptibility. These fines were extracted from the original subgrade filling and re-introduced into the soil samples during specimen preparation to simulate field conditions.

2.2. Test Apparatus

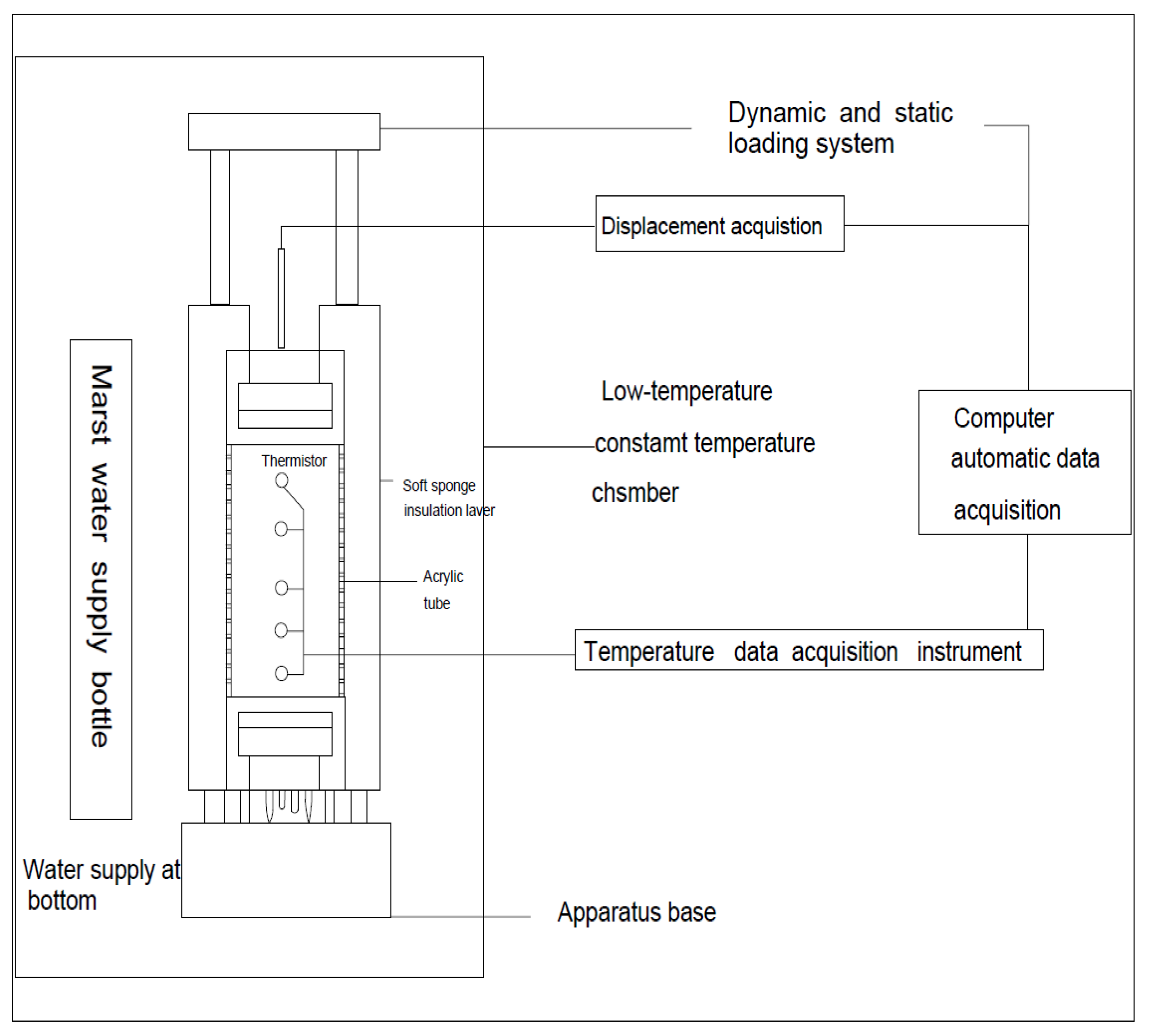

The frost heave testing apparatus used in this study was designed to simulate one-dimensional freezing conditions under controlled thermal and mechanical environments. As shown in

Figure 3, the experimental system mainly consisted of a cylindrical sample cell, a loading system, a displacement measurement system, and temperature control units.

The sample cell was fabricated from an acrylic tube with an inner diameter of 15 cm and a height of 15 cm, ensuring adequate confinement and uniform heat transfer. The upper plate of the cell was connected to a servo-controlled loading system, capable of applying both static and dynamic loads to the soil specimen. The magnitude and frequency of the dynamic load were precisely controlled by a computer through a servo valve. The cooling plate temperature was maintained at −5.5 °C with a stability of ±0.1 °C; the bottom plate temperature was controlled at +3.0 °C with fluctuations within ±0.1 °C; and room ambient temperature varied within 18–20 °C during testing.

The vertical deformation was measured by a displacement sensor with an accuracy of 0.001 mm, and the applied load was monitored by a load cell with an accuracy of ±0.1 kPa. The temperature sensors had an accuracy of ±0.1 °C, and the gravimetric water content measurements had an accuracy of approximately ±0.1%. The upper and lower ends of the specimen were connected to two constant-temperature cold baths, which provided the desired cooling and heating boundary conditions. The top cooling plate was adjusted to a target subzero temperature, while the bottom plate was maintained at +3 °C, forming a stable temperature gradient and enabling one-dimensional freezing.

During the test, the data acquisition system automatically recorded displacement, load, and temperature in real-time. The frost-heave deformation of the soil sample was determined by comparing the displacement of the loading plate at different time intervals with its initial position prior to freezing.

In this study, a closed system refers to a freezing condition where no external water is allowed to enter the specimen; the soil contains only its initial pore water and all boundaries are sealed. In contrast, an open system allows external water to be supplied through a constant-head device connected to the base of the specimen, enabling upward water migration toward the freezing front. In the open-system tests, external water was supplied to the specimen through a constant-head Mariotte bottle. The outlet of the bottle was connected to the bottom of the soil column, and the hydraulic head was maintained at 2 cm above the specimen base, providing a stable and low-pressure inflow. The inflow water was tap water with negligible salinity, and the temperature was controlled at +3 °C, consistent with the warm-end boundary to avoid introducing additional temperature gradients. Water entered the specimen through a perforated porous stone at the base, ensuring uniform upward supply. An overflow port located at the top of the sample cell allowed excess water to drain freely, preventing pore-water overpressure or unintended saturation during freezing. This setup ensured a continuous yet controlled water supply throughout the freezing process, making the open-system condition directly comparable to the closed system except for the availability of external water.

2.3. Test Process

Each frost-heave test consisted of two main stages: an isothermal pre-freezing stage and a freezing stage. The soil specimens were compacted into cylindrical molds with dimensions of 15 cm in height and 15 cm in diameter to achieve the desired density and water content.

During the isothermal stage, both the upper and lower constant-temperature baths were maintained at +3 °C for approximately 8 h to ensure uniform temperature distribution and thermal equilibrium throughout the sample. Once the internal temperature of the soil stabilized at +3 °C, the freezing stage was initiated.

In the freezing stage, the upper cold plate was adjusted to the target subzero temperature (−3 °C, −5.5 °C, or −7.5 °C) to create a one-dimensional freezing condition, while the lower plate remained at +3 °C. The loading system was activated simultaneously to apply the predetermined static or dynamic load, and the water supply system was opened or closed depending on whether the test was conducted under an open or closed system condition.

Throughout the freezing process, which lasted approximately 72 h, the temperature, load, and vertical displacement of the specimen were continuously recorded by the data acquisition system. The frost-heave deformation was determined by comparing the displacement of the loading plate at different times with its initial position before freezing. After completion of the freezing stage, the specimen was carefully dismantled to measure the frozen depth and final water content distribution.

After the freezing stage, the soil column was carefully extruded from the acrylic cylinder and immediately sectioned vertically into layers with a thickness of 3 cm (from the warm end to the cold end). Each layer was quickly placed into a pre-weighed, airtight aluminum box to minimize moisture loss. The wet mass of each box was measured using an electronic balance with an accuracy of ±0.01 g. The samples were then oven-dried at 105 ± 2 °C for at least 24 h to ensure complete drying. After cooling in a desiccator, the dry mass was recorded and the gravimetric water content of each layer was calculated from the difference between wet and dry masses. Because the samples were fully thawed during the drying process, residual ice was completely melted and evaporated, and no additional correction was required.

2.4. Test Program

A series of one-dimensional frost heave tests were conducted to investigate the effects of load form, load magnitude, load frequency, upper plate freezing temperature, and water supply condition on the frost heave behavior of coarse-grained soil. All specimens were prepared with identical initial water content, fines content, and degree of compaction to ensure comparability among different test conditions.

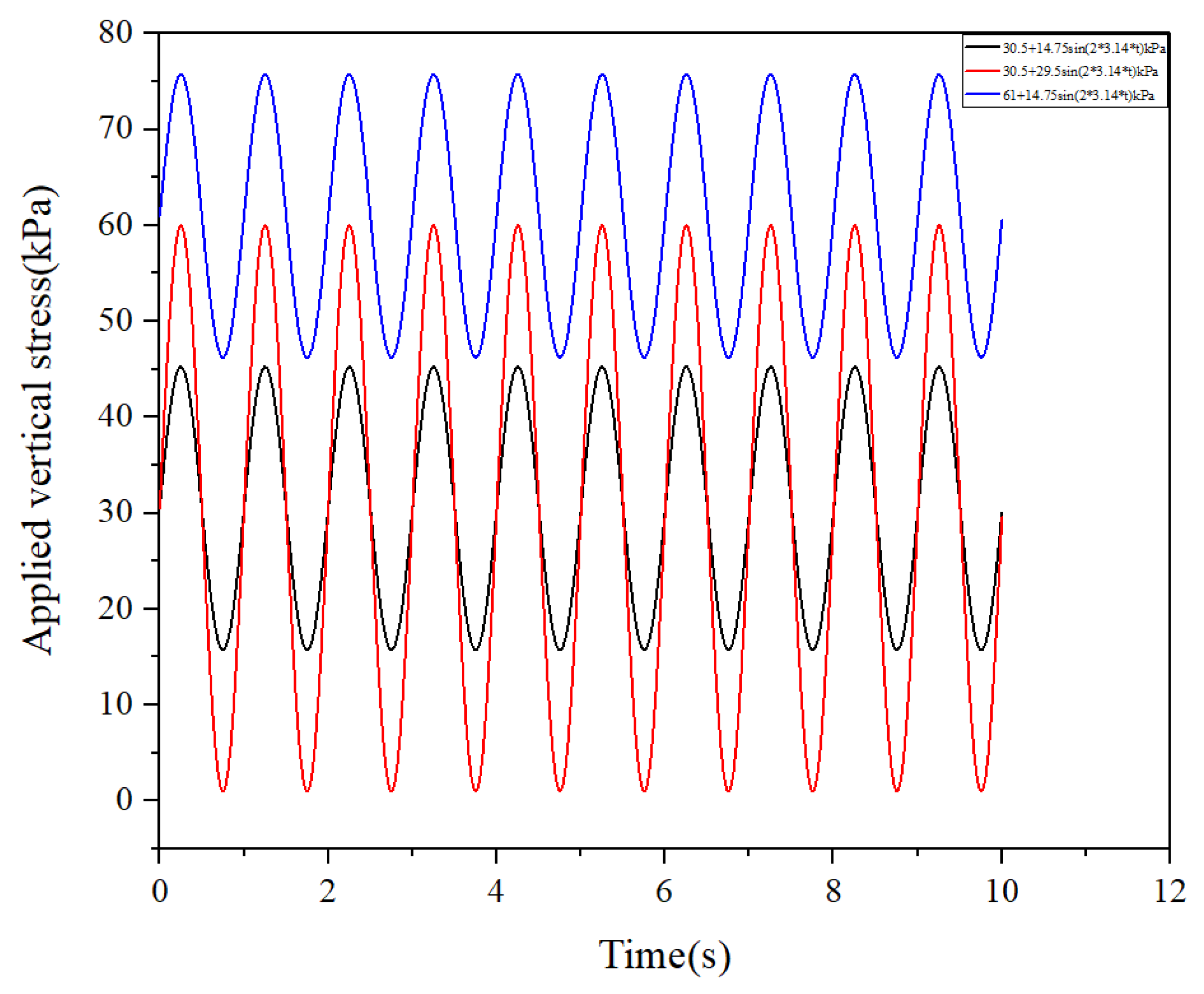

Dynamic loads were applied as sinusoidal vertical stresses of the form

where

is the applied vertical stress (kPa),

is the mean stress,

is the stress amplitude,

is the loading frequency (Hz), and

is time in seconds.

In the field, the vertical stress acting on the frost-susceptible subgrade layer beneath a high-speed railway is governed by the self-weight of the overlying embankment and structural layers, together with the cyclic stress induced by train loads. For Chinese HSR lines, EMU trainsets are designed with axle loads not greater than approximately 17 t per axle, and the resulting peak dynamic vertical stress at the top of the ballast track subgrade is typically on the order of 20–100 kPa. The static overburden stress within the upper 1–3 m of the subgrade is of a similar magnitude (approximately 20–60 kPa) for unit weights of 18–20 kN/m

3; and common embankment heights. Accordingly, the nominal vertical stresses of 14.75, 30.5, and 61 kPa adopted in this study were selected to span a representative range of in situ subgrade stresses under seasonal frost conditions. The lowest level (14.75 kPa) corresponds to shallow overburden and relatively light traffic loading, the intermediate level (30.5 kPa) represents a typical combined stress due to embankment self-weight and high-speed train loading, and the highest level (61 kPa) reflects an upper-bound confinement associated with thicker embankments or higher axle loads. In the dynamic tests, sinusoidal loads were applied around these mean values (e.g., 30.5 + 29.5 sin(2πft) kPa and 61 + 14.75 sin(2πft) kPa), such that the peak stresses fell within the range reported for high-speed railway subgrade surfaces. Thus, in this study, three dynamic loading conditions were used, as shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 4. For a test duration of 72 h (259,200 s), the total number of loading cycles were 129,600, 259,200, and 777,600 for 0.5, 1.0, and 3.0 Hz, respectively.

The complete experimental matrix is summarized in

Table 3, which lists all combinations of loading parameters and thermal conditions. Each test lasted approximately 72 h, during which the internal temperature, frost front position, frost-heave deformation, and final water content distribution were continuously monitored and recorded. This table provides a unified overview of all thermal, hydraulic, and mechanical boundary conditions used in the test matrix, enabling consistent comparison across loading and water-supply scenarios.

In the closed system, the specimen base, sidewall, and instrumentation ports were sealed, and no external water source was connected, ensuring that the only water available during freezing was the initial pore water. In the open system, a constant-head Mariotte bottle was connected to the base of the specimen, supplying +3 °C water through a porous stone. An overflow port at the top allowed excess water to escape, preventing internal pressurization. These changes make the operational differences between the two systems more explicit.

The dynamic and static loads were applied using a servo-hydraulic actuator controller manufactured by Zhejiang Tomos Company (Wenzhou, China), model T-2019SH, as shown in

Figure 4 when the f=1 Hz. The vertical stress at the top of the specimen was measured by a load cell with an accuracy of ±0.1 kPa. Prior to the test series, both the actuator and load cell were calibrated against a standard proving ring. The measured stress histories were compared with the programmed sinusoidal waveforms, and the discrepancies in mean and peak stresses were within ±2%.

3. Results

3.1. Internal Temperature

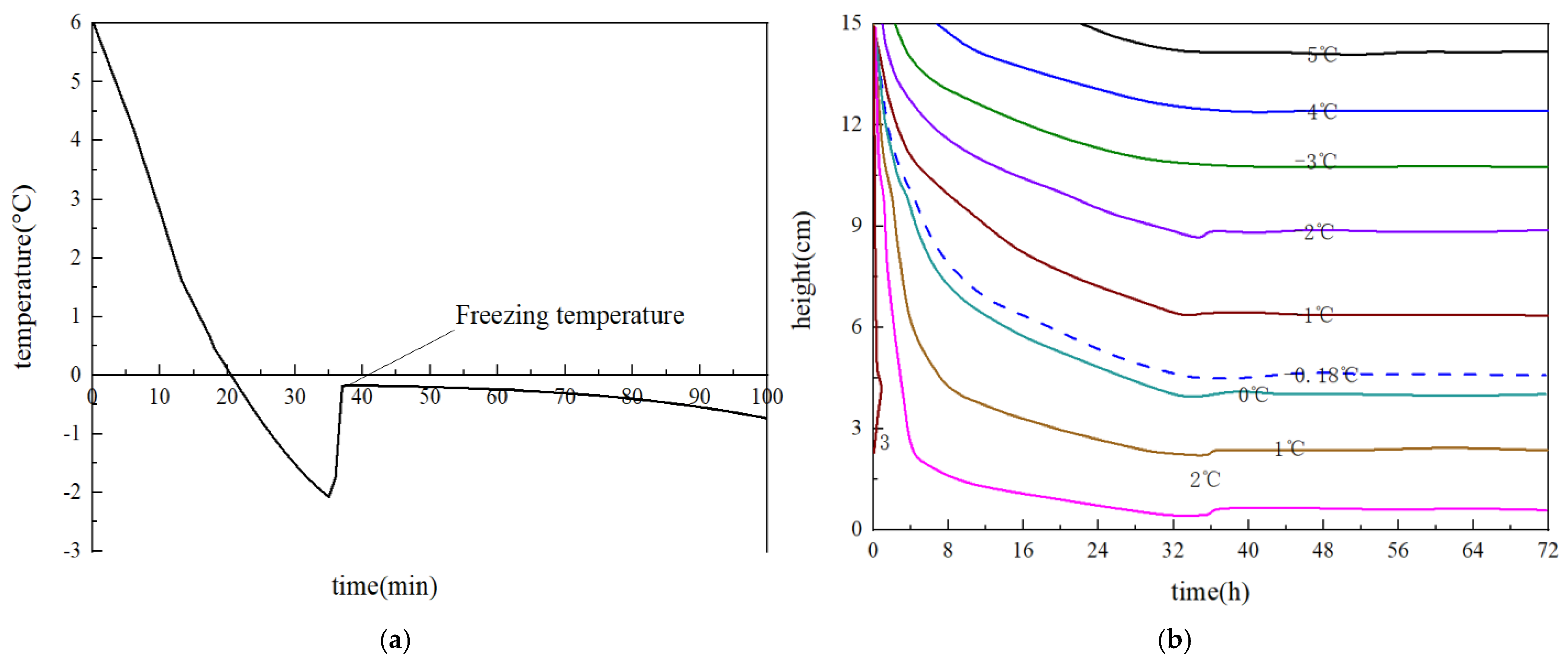

The freezing temperature of Group A soil containing 8% fines was determined from the cooling and freezing curves. As shown in

Figure 5a, the temperature at which the internal temperature of the specimen stabilized was defined as the freezing point, which was approximately −0.18 °C.

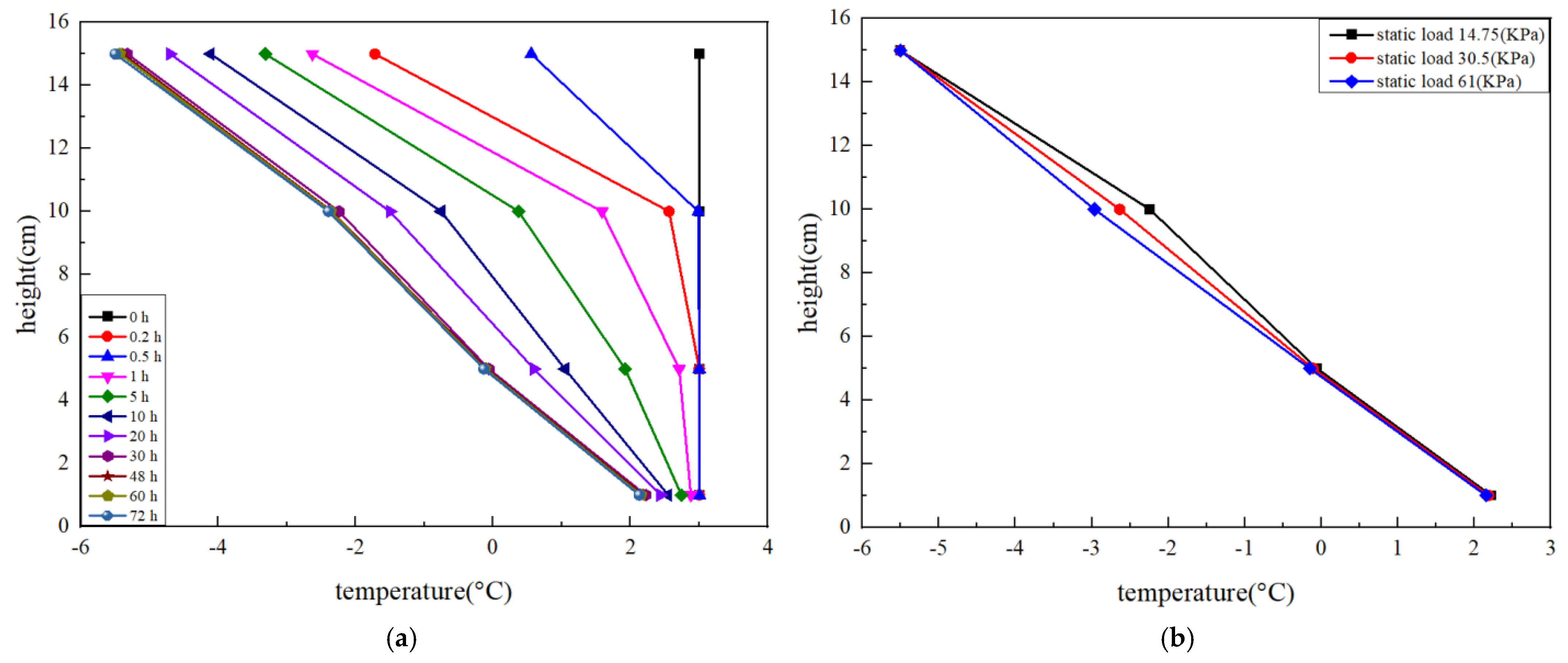

Figure 5b illustrates the internal temperature variation of Group A soil under a static load of 30.5 kPa in the closed system. The depth of 15 cm represents the cold end (upper surface) with a upper plate freezing temperature of −5.5 °C, while 0 cm corresponds to the warm end maintained at +3 °C. During the initial stage of freezing (0–8 h), the temperature gradient changed rapidly, indicating the rapid-freezing zone. As the freezing front approached the phase transition zone (8–30 h), the temperature gradient decreased, and the movement of the freezing front slowed down. Over time, the temperature profile reached a steady state, corresponding to the stationary freezing zone.

Figure 5b shows multiple full temperature profiles (temperature vs. height) at selected times.

Figure 5a shows the temperature at each thermistor over time (temperature vs. time). The freezing process can be divided into three stages based on the temperature profiles and the heave–time response. (i) Rapid cooling stage (0–6 h): The soil column releases most of its sensible heat, and the temperature drops sharply from the warm-end boundary toward the developing freezing front. (ii) Freezing-transition stage (approximately 6–20 h): The progression of the freezing front slows as latent heat consumption becomes dominant. During this stage, temperature gradients decrease progressively and water migration toward the freezing front begins to intensify. (iii) Approach-to-equilibrium stage (after ~20 h): The freezing front advances only marginally as the soil column approaches thermal equilibrium. The thermal gradient becomes relatively small, and both frozen depth and heave deformation gradually stabilize. These observations are consistent with the temporal response shown in

Figure 6, where the heave rate decreases significantly after 20 h. The revised analysis provides a clearer physical interpretation of the freezing-transition period.

Figure 5b compares temperature distributions under different static loads (14.75, 30.5, and 61 kPa) at 72 h. Although minor differences were observed in the early stage of freezing, the final temperature profiles were nearly identical. This indicates that the magnitude of external load had a negligible effect on the internal temperature field of Group A soil.

3.2. Frozen Depth

The soil column could be divided into frozen and unfrozen regions based on the measured temperature distribution. The depth at which the temperature approached the freezing point was identified as the frozen depth.

Figure 7 presents the variations in frozen depth of Group A soil under different loading conditions, upper plate freezing temperatures, and system types.

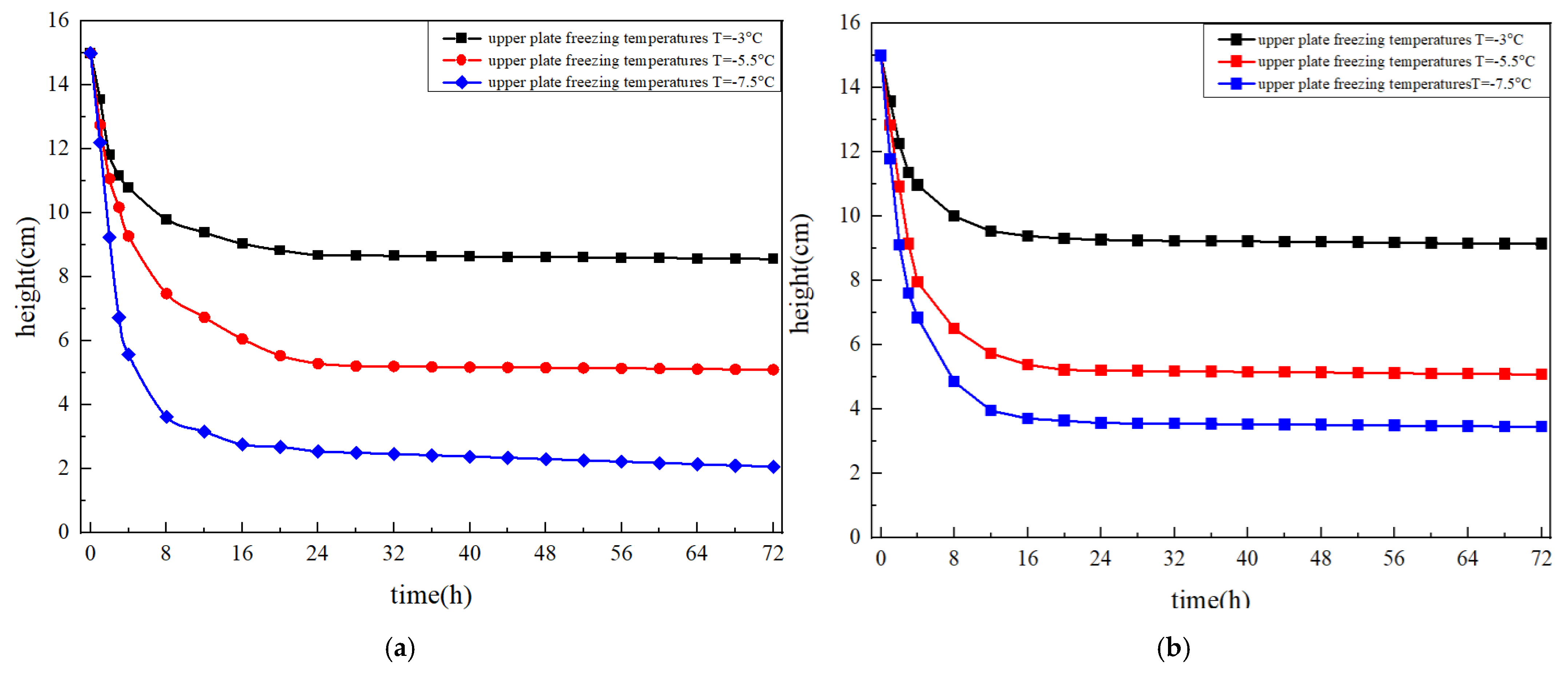

As shown in

Figure 7a,b, the frozen depth increased with decreasing upper plate freezing temperature. When the upper plate freezing temperatures were −3 °C, −5.5 °C, and −7.5 °C, the frozen depths were approximately 6.3 cm, 9.68 cm, and 13.46 cm, respectively, for the closed system under static loading; and 5.85 cm, 9.5 cm, and 11.5 cm, respectively, for the open system under dynamic loading. These results indicate that the frozen depth in the open system was slightly smaller than that in the closed system. This difference occurs because, in the open system, the continuous water supply reduces the thermal gradient by altering the soil water content and thermal conductivity. Consequently, more cooling capacity is consumed by the additional water migration and phase transition, resulting in a smaller frozen depth.

As illustrated in

Figure 7c, external loading influenced the freezing process primarily during the initial stage. The applied load compacted the soil, increased its density, and slightly enhanced its thermal conductivity, thereby accelerating the early freezing rate. Consequently, minor differences in frozen depth were observed among tests with no load, static load, and dynamic load during the early freezing phase. However, as freezing progressed, the compaction effect stabilized, and the thermal conductivity became nearly constant. Therefore, the final frozen depth showed little dependence on the form of applied load.

Similarly, as shown in

Figure 7d, the frequency of dynamic load also had a limited effect on the final frozen depth. Although higher frequencies (e.g., 3 Hz) initially promoted faster heat transfer and thus a slightly quicker development of the frozen front, the difference among frequencies (0.5, 1, and 3 Hz) became negligible after approximately 72 h.

Thus, the results demonstrate that upper plate freezing temperature is the dominant factor controlling the frozen depth of coarse-grained soil, while the effects of load form, magnitude, and frequency are relatively minor once thermal equilibrium is reached.

3.3. Frost-Heave Deformation

The frost-heave deformation behavior of Group A coarse-grained soil under various thermal and loading conditions is illustrated in

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

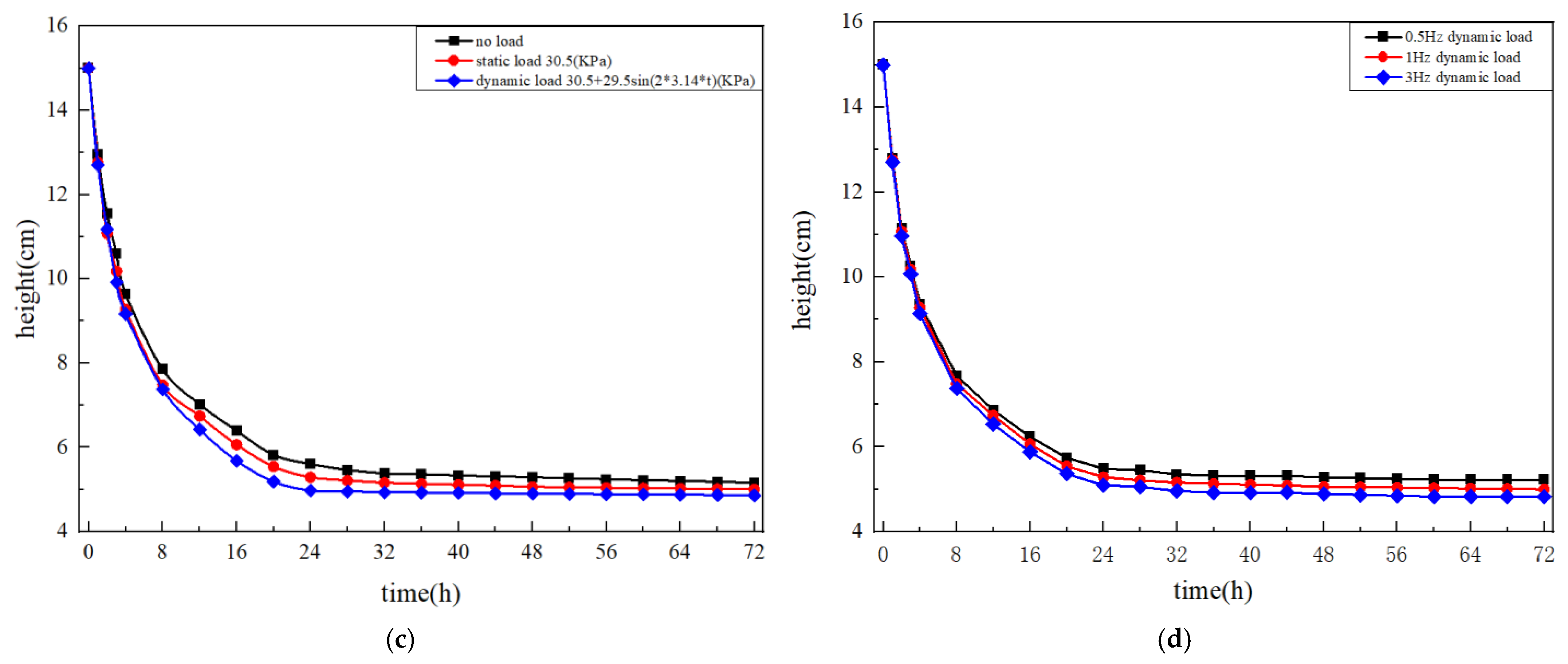

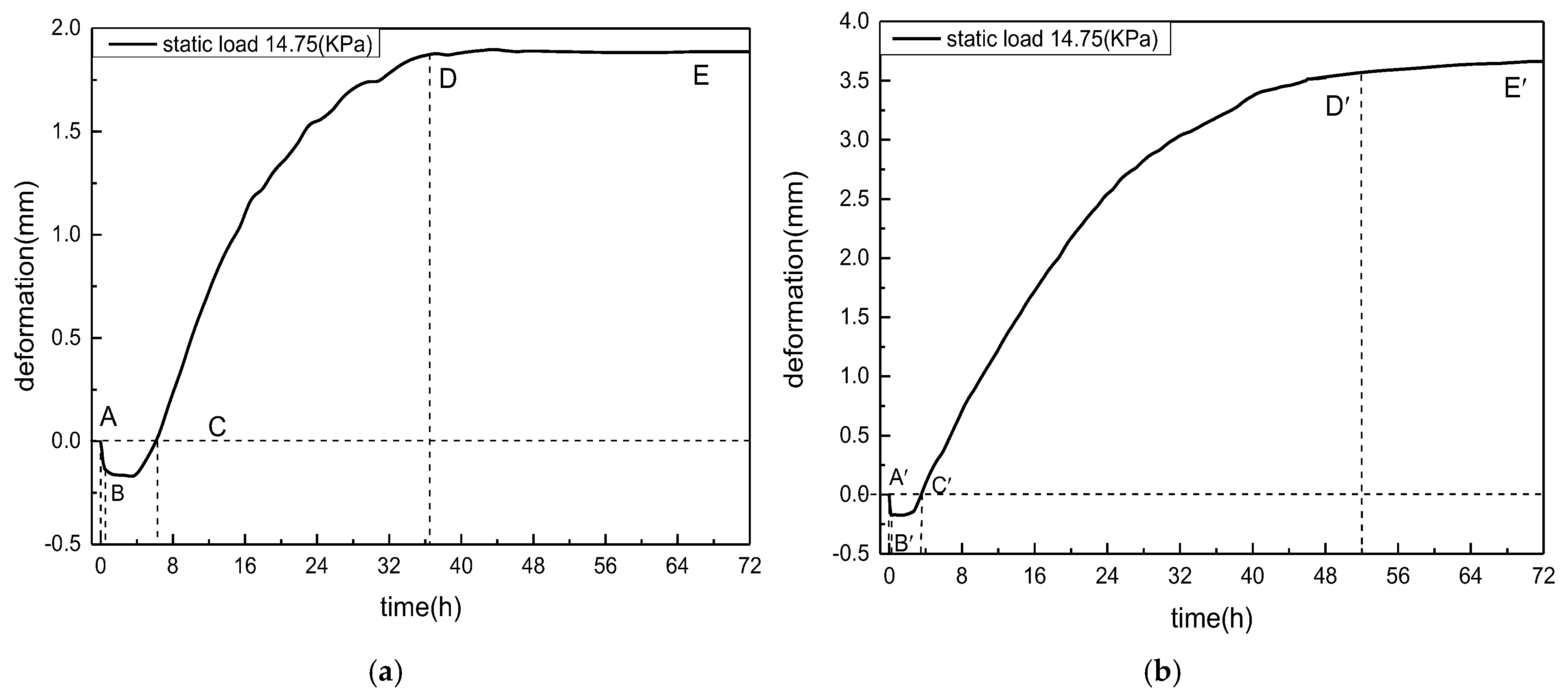

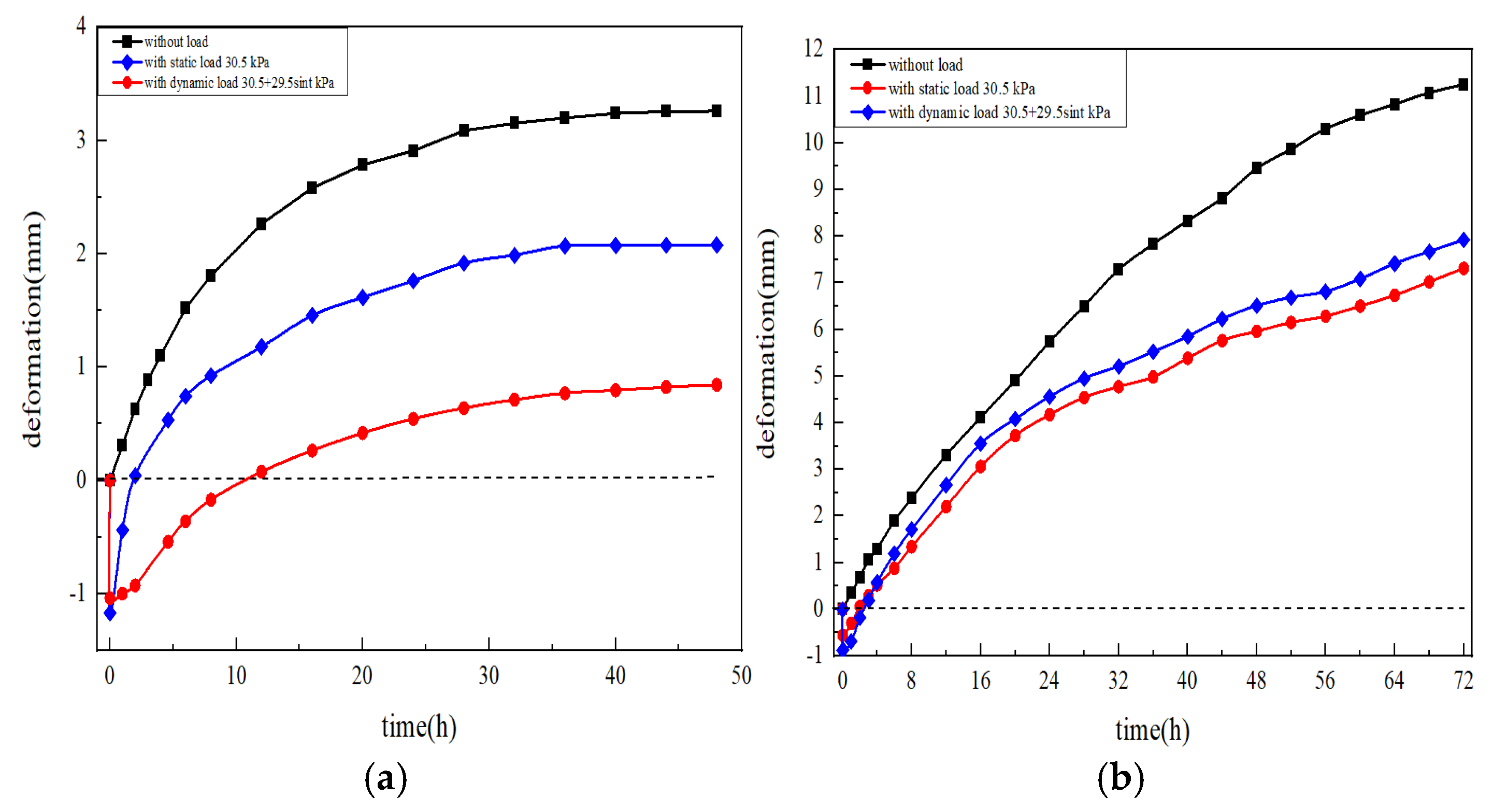

As shown in

Figure 8a, the deformation–time curve in the closed system can be divided into four characteristic stages: Initial compression stage (A–B): The specimen was compressed due to the applied external load at the beginning of freezing; Frost-heave growth stage (B–C): The rate of compression decreased, and frost-heave forces began to develop gradually; Frost-heave development stage (C–D): Once the frost-heave force exceeded the external load, upward displacement occurred and the frost-heave deformation increased rapidly; Stable stage (after D): After approximately 36–40 h, the deformation curve reached a plateau, indicating that the freezing front had stabilized and the heaving process ceased. In the open system (

Figure 8b), the deformation process followed similar stages but exhibited greater total deformation and a shorter frost-heave growth period. At a static load of 14.75 kPa and a upper plate freezing temperature of −5.5 °C, the frost-heave deformation after 72 h was 3.66 mm in the open system and 1.89 mm in the closed system. The larger deformation in the open system resulted from continuous external water supply, which enhanced upward water migration and ice lens development. Early stage compression results from the combined effects of particle rearrangement, load-induced skeleton compression, and pore-pressure dissipation under decreasing temperature. As freezing progresses, the advance of the freezing front generates increasing matric suction and reduces permeability, which drives water migration toward the freezing front. This promotes ice lens growth and thus switches the behavior from compression to net heave.

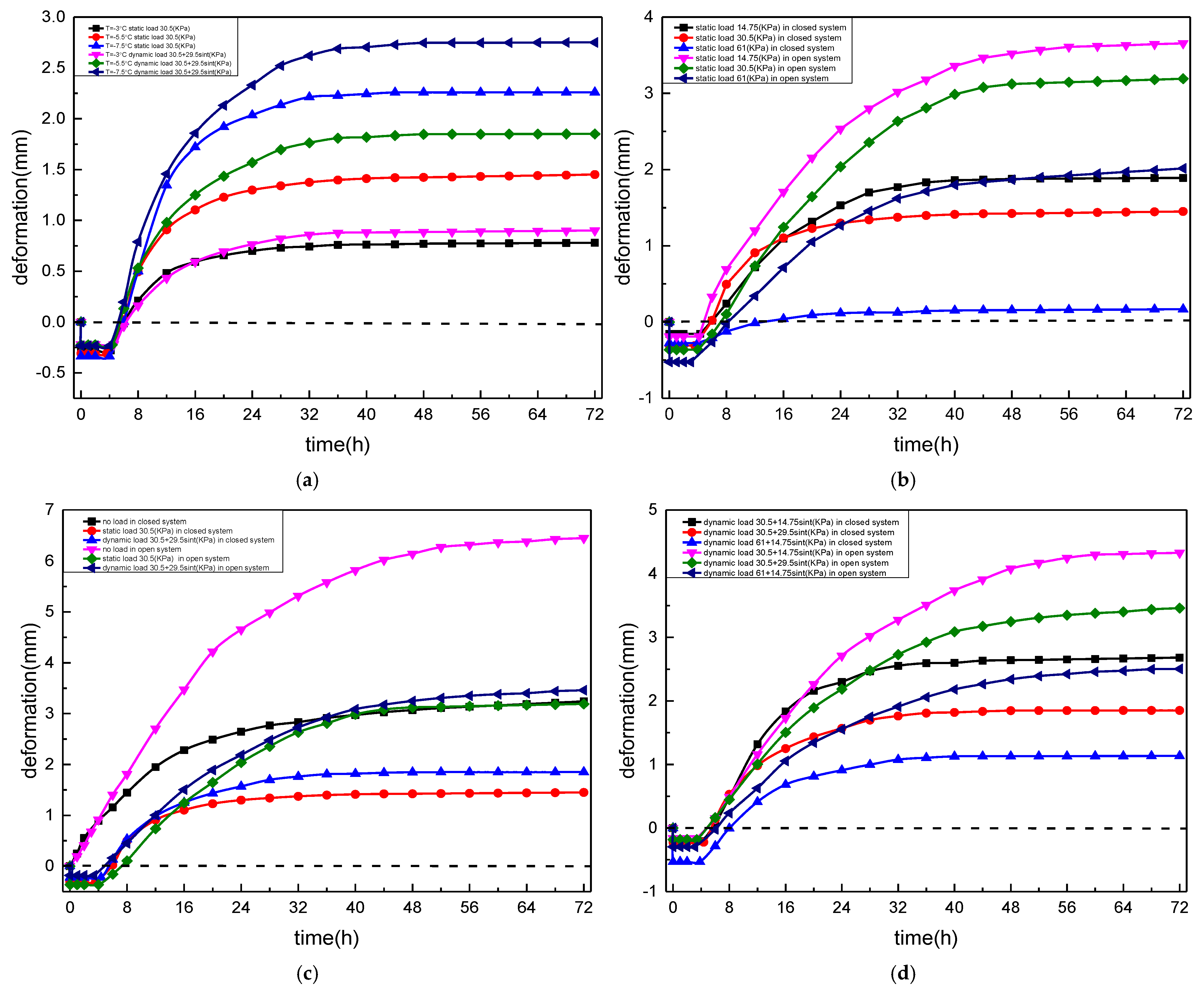

The influence of upper plate freezing temperature on frost-heave deformation under both static and dynamic loading is shown in

Figure 9a. As the upper plate freezing temperature decreased from −3 °C to −7.5 °C, the frost-heave deformation increased from 0.6 mm to 2.66 mm under static loading, and from 1.38 mm to 3.25 mm under dynamic loading. Lower temperatures intensified the freezing rate and promoted ice formation, leading to larger frost-heave deformation. As shown in

Figure 9b, deformation behavior varied with load form. Under identical thermal conditions (−5.5 °C), the magnitude of frost heave followed the order: no load > dynamic load > static load, in both closed and open systems. This demonstrates the inhibitory effect of external loading on frost-heave deformation. Moreover, the open system produced greater frost heave than the closed system due to enhanced water migration from external sources. The influence of load magnitude is presented in

Figure 9c,d. Increasing the static load from 14.75 kPa to 61 kPa led to greater initial compression (0.16–0.53 mm) and significantly reduced the total frost-heave deformation. A similar pattern was observed for dynamic loading: higher amplitude loads (e.g., 61 + 14.75 sin t kPa) produced smaller frost-heave deformation compared with lower amplitude loads.

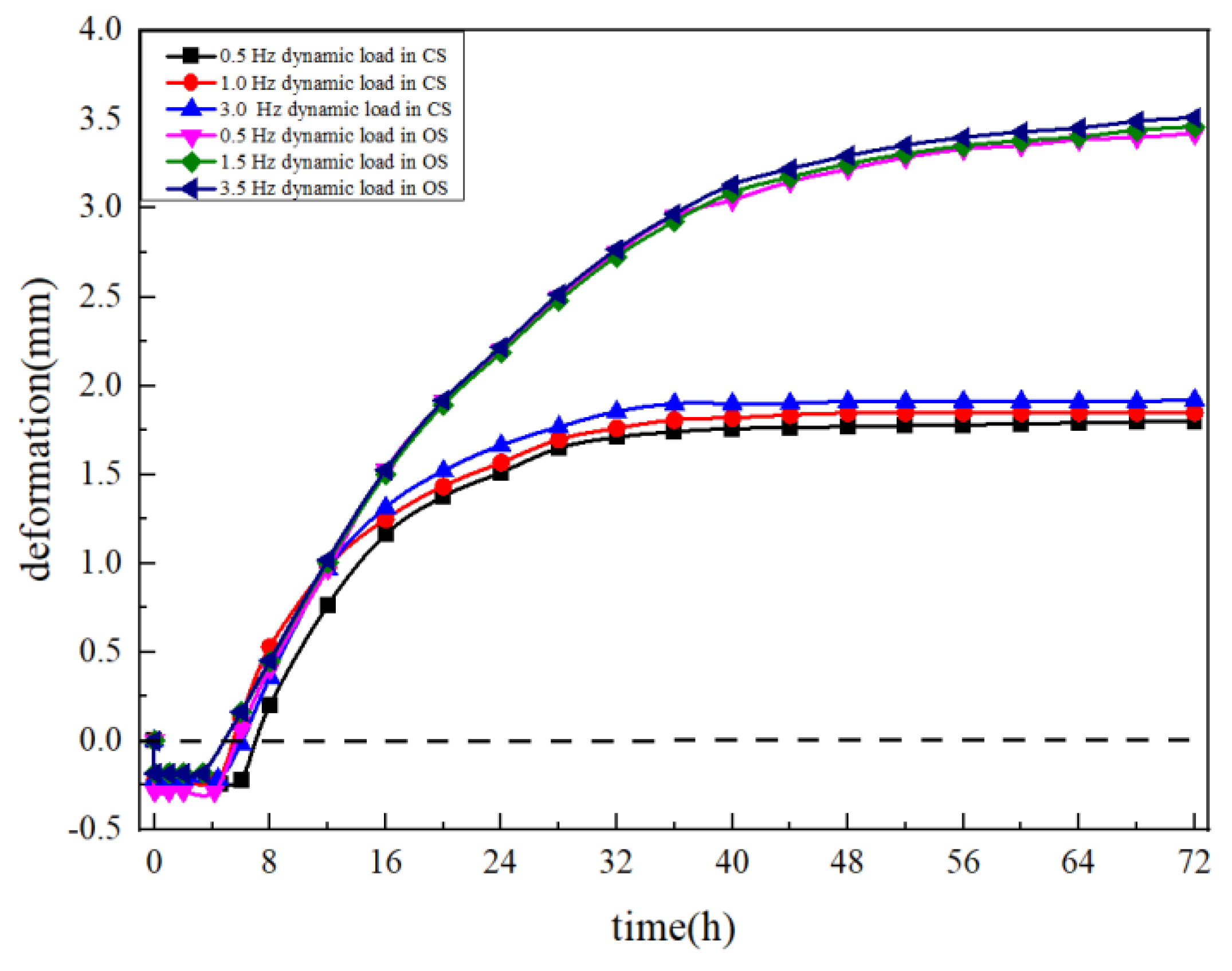

The effect of dynamic load frequency is shown in

Figure 10. Frequencies of 0.5, 1, and 3 Hz resulted in nearly parallel deformation–time curves, indicating that load frequency had minimal influence on frost-heave deformation. Although higher frequencies slightly accelerated early compression, their overall impact on final deformation was negligible. Under the present loading amplitudes and thermal conditions, the characteristic timescale of freezing is much longer than the timescale of mechanical loading. In contrast, the characteristic freezing timescale is on the order of several hours, as the frost front requires tens of thousands of seconds to move through the 15 cm soil column. As a result, the soil essentially “feels” the mean applied stress, and the rapid oscillations average out over the duration of freezing. This explains why frost heave and frozen depth exhibited only minor differences among 0.5, 1, and 3 Hz.

Thus, the upper plate freezing temperature, water supply condition, and load magnitude were the key factors governing frost-heave behavior in coarse-grained soil. External loading reduced frost-heave deformation by increasing soil density and restricting water migration. Under equivalent conditions, the frost-heave deformation followed the consistent order: no load > dynamic load > static load, in both closed and open systems.

3.4. Water Content

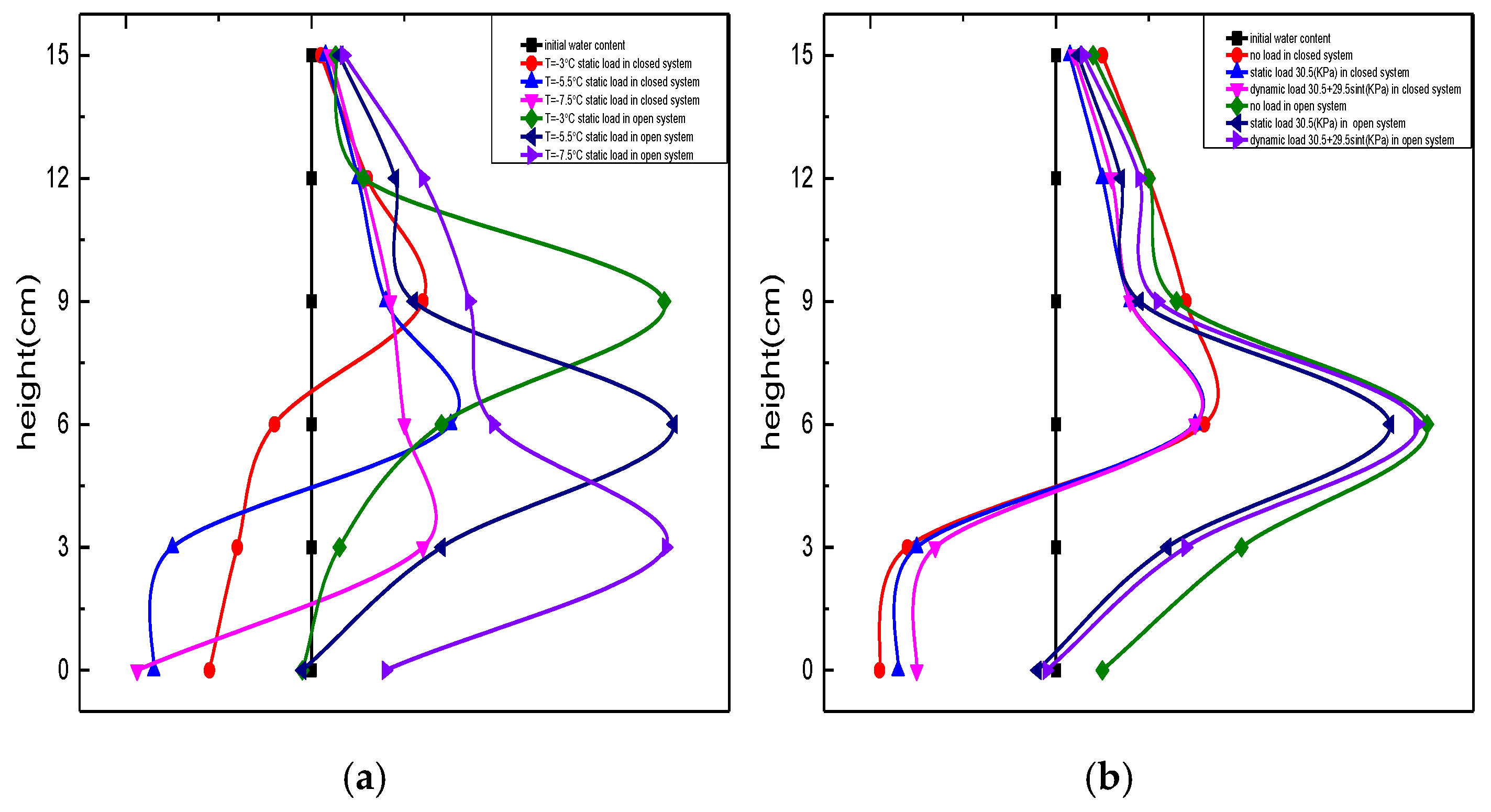

Figure 11 illustrates the water content distribution of Group A soil after freezing under various loading and thermal conditions.

As shown in

Figure 11a, the upper plate freezing temperature had a marked influence on the vertical distribution of water content in both the closed and open systems. The height of the maximum water content decreased with decreasing temperature. Specifically, when the upper plate freezing temperatures were −3 °C, −5.5 °C, and −7.5 °C, the peaks of water content occurred at approximately 9–12 cm, 6–9 cm, and 3–6 cm, respectively. Although the location of the peak shifted downward with lower temperature, the magnitude of the maximum water content varied little, ranging from 13.2–13.5 % in the closed system and 13.4–13.5 % in the open system. The open system exhibited slightly higher overall water contents due to the continuous external water supply, which maintained near-initial water content even near the warm end (0 cm).

Figure 11b,c show the effects of load form and load magnitude. The presence of external loads reduced water content, especially around the frost front. Without loading, the suction velocity at the freezing front exceeded the soil’s drainage capacity, promoting strong upward migration of water and resulting in greater water accumulation. Under higher static or dynamic loads, soil compaction decreased pore connectivity and permeability, leading to smaller increases in water content within the frozen zone. At −5.5 °C, the maximum water contents were 13.5 % under a 30.5 kPa static load and 13.3 % under a 30.5 + 29.5 sin t kPa dynamic load, both appearing around 6 cm height.

Figure 11d presents the effect of dynamic load frequency. The results show that frequency variation (0.5, 1, and 3 Hz) had little influence on water content distribution in both systems. The profiles of water content were nearly identical across different frequencies, confirming that mechanical oscillation did not significantly alter water migration during freezing.

The upper plate freezing temperature and load form were the dominant factors controlling water distribution in coarse-grained soil. Lower temperatures and no-load conditions facilitated greater upward water migration and accumulation near the frost front. In contrast, external loading compacted the soil structure, reduced permeability, and consequently limited water movement.

However, the difference in water content between the frozen and unfrozen portions was less pronounced than that observed in fine-grained soils [

7]. This is because the higher freezing rate in coarse-grained soil causes most pore water to freeze rapidly in situ, limiting long-distance water migration. Consequently, frost-heave deformation mainly results from localized freezing expansion rather than significant upward water flow for coarse-grained soil.

3.5. Frost Heave Ratio

The frost heave ratio is defined as

where

is the final frost-heave deformation,

is the frozen depth.

The frost-heave ratio of Group A soil was calculated, as summarized in

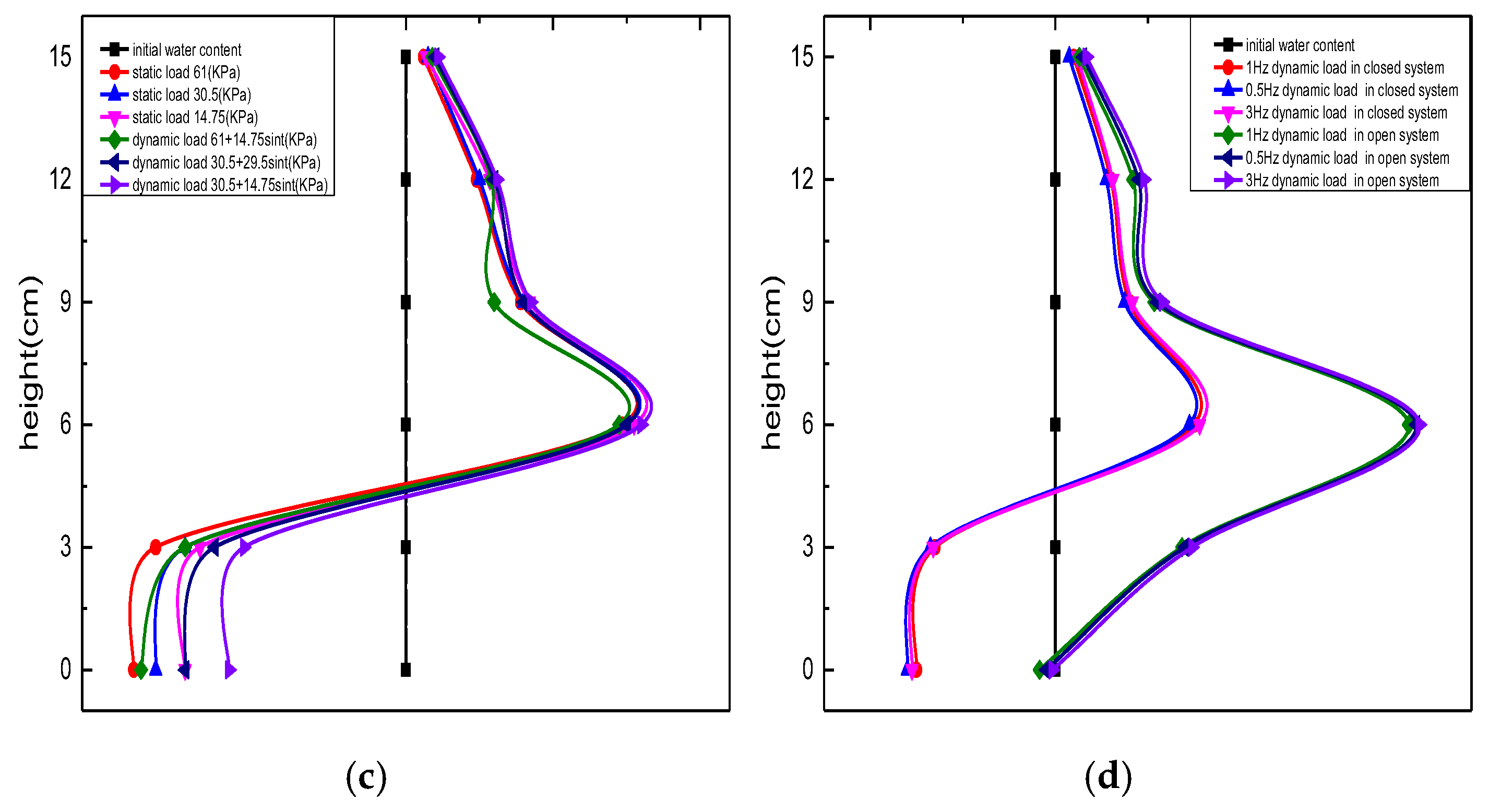

Table 4. In the table, “CS” and “OS” refer to the closed system and open system, respectively.

The results indicate that the frost-heave ratio increased significantly with decreasing upper plate freezing temperature in both systems. For example, under a static load of 30.5 kPa, the frost-heave ratio increased from 1.21 % at −3 °C to 1.68 % at −7.5 °C in the closed system, and from 1.85 % to 2.77 % in the open system. The higher frost-heave ratios in the open system are attributed to continuous external water supply, which promotes upward water migration and ice lens formation. The load magnitude also exhibited a pronounced influence on the frost heave ratio. As the static load increased from 14.75 kPa to 61 kPa, the frost-heave ratio decreased from 1.97 % to 0.17 % in the closed system, and from 3.90 % to 2.06 % in the open system. This confirms that greater external loads effectively suppress frost-heave deformation by increasing soil density and limiting pore water migration.

Figure 12 illustrates the relationship between upper plate freezing temperature and frost-heave ratio, showing a nearly linear increase in frost-heave ratio with decreasing temperature.

Figure 13 presents the effect of load magnitude, demonstrating that the frost heave-ratio decreases with increasing load, under both static and dynamic conditions. Dynamic loads generally resulted in slightly higher frost-heave ratios than static loads, indicating that cyclic stress may enhance pore pressure oscillation and localized water movement during freezing. The upper plate freezing temperature and load magnitude are the dominant factors controlling frost-heave ratio in coarse-grained soils. External loading effectively reduces frost-heave deformation, whereas lower temperatures and open water conditions promote greater frost-heave development.

4. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that vertical stress plays a critical role in regulating frozen depth, water migration, and frost-heave development in coarse-grained subgrade soils. Increasing the applied load leads to particle rearrangement and a reduction in void ratio, which in turn increases soil density. This densification lowers the hydraulic conductivity of the skeleton and restricts the rate at which liquid water can migrate toward the freezing front. According to classical ice-lens theory, the growth of segregated ice lenses requires a continuous supply of unfrozen water; therefore, reduced permeability under higher loads suppresses ice-lens formation and results in smaller heave magnitudes. The present findings agree with this mechanism, as the highest confining stress (61 kPa) produced the smallest heave and shallowest frozen depth in both open- and closed-system conditions.

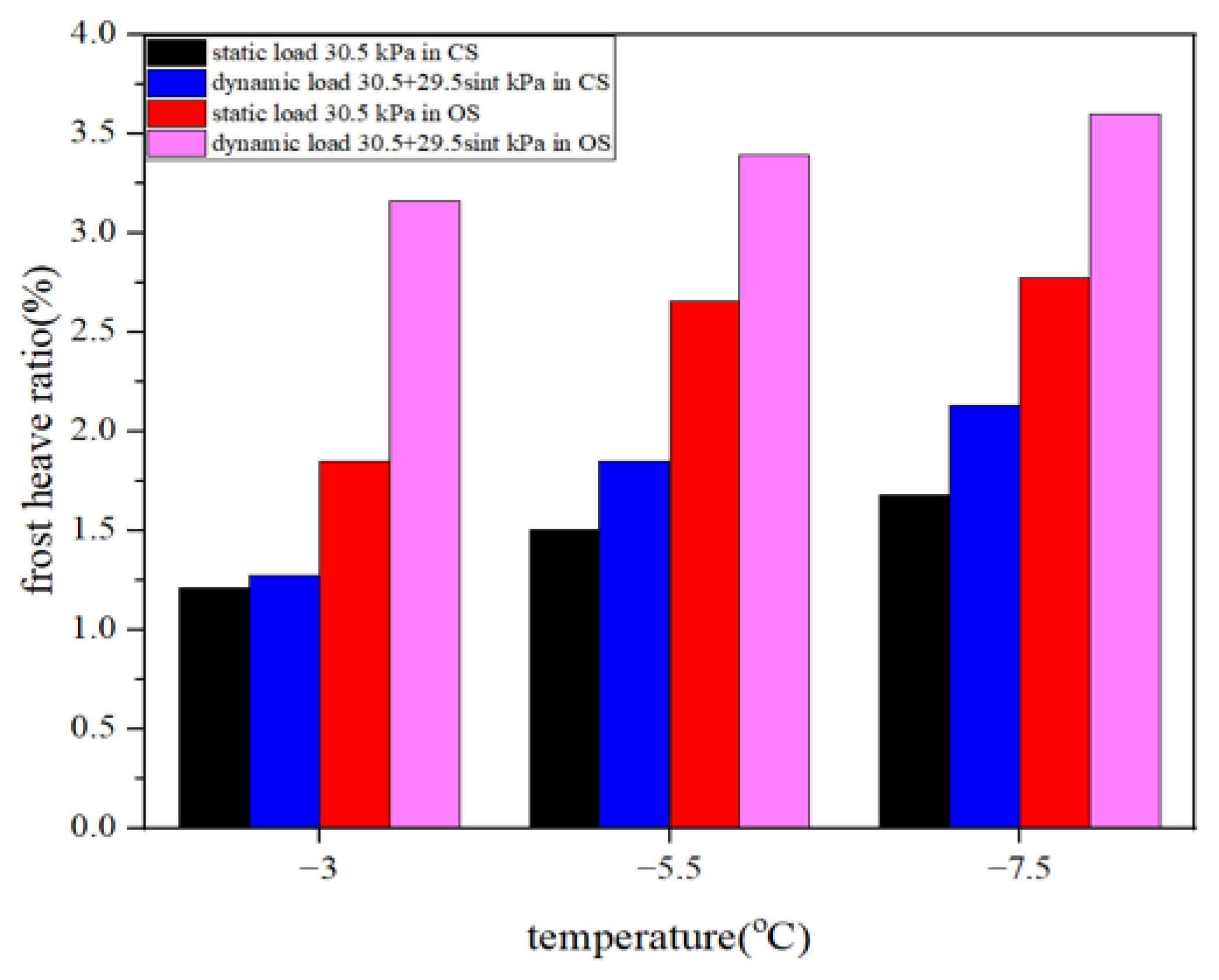

The frost-heave mechanisms observed in the present coarse-grained Group A soil differ fundamentally from those typically reported for fine-grained silts and clays. The deformation behavior of fine-grained [

7] and coarse-grained soils (

Figure 9) under loading conditions is compared in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

As shown in

Figure 14, both soil types exhibited comparable overall deformation trends during the freezing process. In both closed and open systems, the specimens first underwent compressive deformation caused by external loads at the onset of freezing, followed by upward frost heave once the frost-heave force exceeded the applied stress. Furthermore, for both soil types, frost-heave deformation in the unloaded condition was greater than that under static or dynamic loads, confirming the suppressive effect of external loading on frost-heave development. Despite these similar trends, clear quantitative differences were observed between the two soils. The fine-grained soil exhibited larger compressive deformation and greater frost-heave amplitude, while the coarse-grained soil experienced a longer compression period and smaller total deformation. Specifically, the compression phase of coarse-grained soil lasted approximately 4–5 h in the closed system and 3–4 h in the open system before frost heave commenced. This extended compression period is attributed to its larger particle size and lower fines content, which restrict water migration and delay the initiation of ice-lens formation.

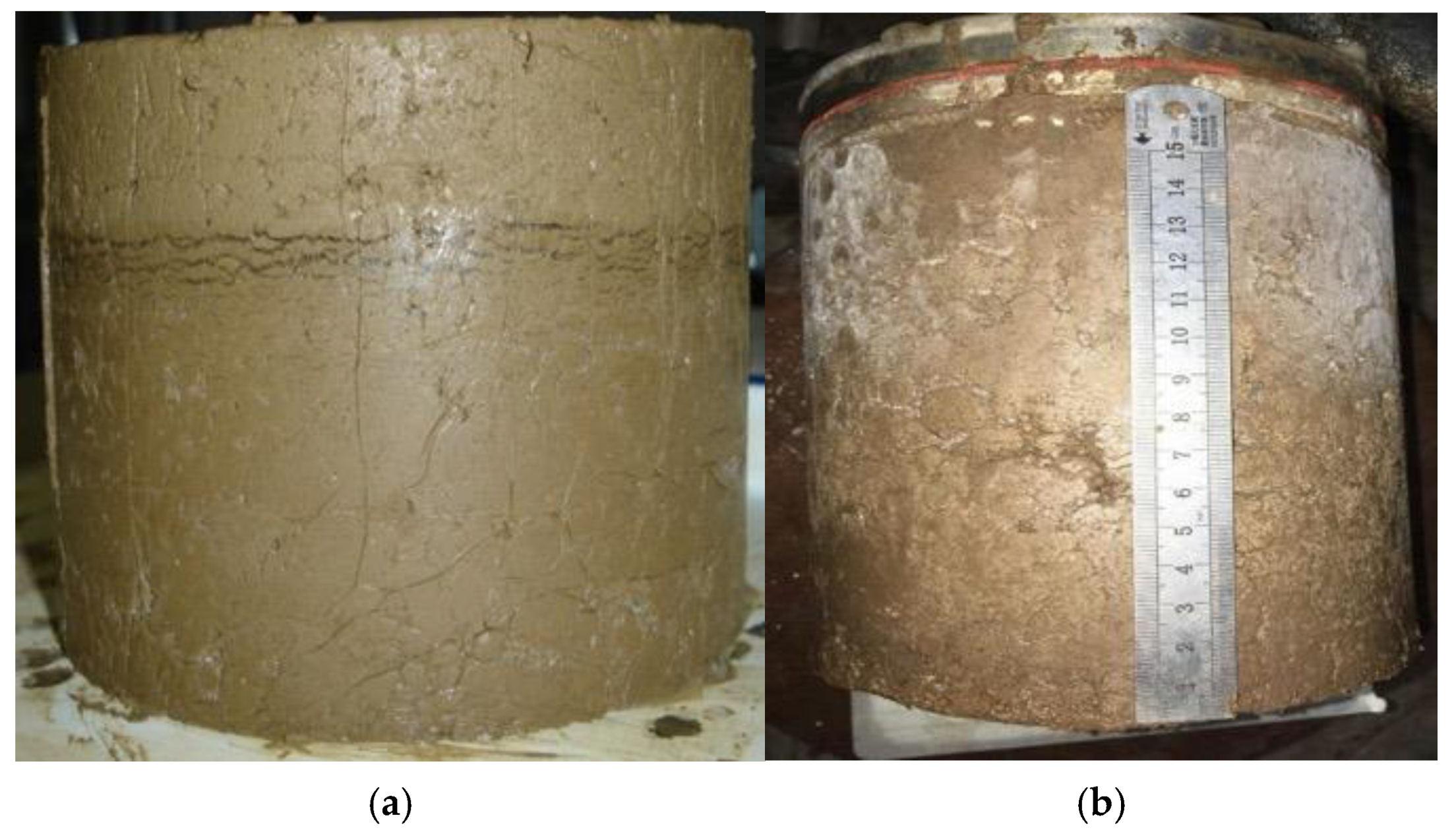

Figure 15 shows the post-freezing surface conditions of both soil types. Irregular cracks were observed around the frost front in each case. These cracks formed due to differential shrinkage induced by temperature gradients between the cold and warm ends, and by the tensile stress that developed when frost-heave forces exceeded the soil’s tensile strength. However, the cracks in fine-grained soil were more extensive and pronounced than those in coarse-grained soil. This difference results from the higher frost susceptibility of fine-grained soil: its finer pore structure and higher water content facilitate upward water migration and continuous ice-lens growth. In coarse-grained soil, larger particles and lower fines content limit both water transport and crack propagation. The fine-grained soil demonstrated greater frost-heave deformation and cracking susceptibility, whereas coarse-grained soil exhibited superior structural stability and weaker frost sensitivity. These results confirm that coarse-grained soil is more suitable as a frost-resistant subgrade material for railway and infrastructure construction in cold-region environments.

Fine-grained soils exhibit strong capillarity, high suction potential, and a well-connected micropore network that enables sustained water migration and repeated ice-lens formation. In contrast, coarse-grained soils have limited capillary rise, weaker suction, and a discontinuous water film at subzero temperatures. As a result, frost heave in coarse materials is more strongly governed by (i) the availability of external water sources, (ii) the macro-permeability of the skeleton, and (iii) the imposed thermal gradient. These differences explain why the coarse-grained soil in this study exhibited modest frost heave in the closed system but became significantly more frost-susceptible in the open system where additional water was supplied.

The difference in frozen depth between the open and closed systems can be understood through an energy-budget analysis. During the freezing process, the total heat extracted from the soil–water system can be partitioned into three components:

where

is the sensible heat removed during cooling,

is the latent heat associated with the phase change of the initial pore water, and

represents the additional latent heat required to freeze externally supplied water in the open system.

The sensible-heat component can be estimated as:

where

and

are the masses of soil solids and initial pore water,

and

are their specific heat capacities, and

is the temperature decrease experienced by the soil column. The latent heat consumed by the freezing of the initial pore water is:

where

is the latent heat of fusion of water

In the open system, however, additional water migrates toward the freezing front and subsequently freezes, consuming extra latent heat given by:

where

is the mass of inflow water that freezes during the test. Order-of-magnitude estimates indicate that

is not negligible compared with

. This means that a substantial portion of the available cooling capacity is consumed by freezing newly supplied water rather than driving the downward advancement of the freezing front.

As a result, the open system exhibits a shallower frozen depth than the closed system, despite identical thermal boundary conditions at the upper and lower plates. The additional latent-heat sink introduced by the inflow water effectively reduces the net cooling energy available for frost penetration. This energy-budget interpretation is consistent with the observed temperature profiles and supports the conclusion that external water supply fundamentally alters the thermodynamic pathway of the soil–water–ice system during freezing.

The results provide several implications for the construction and maintenance of coarse-grained subgrades in seasonally frozen regions. First, higher overburden or structural load helps reduce frost-related deformation by compacting the soil matrix and limiting water migration, suggesting that deeper subgrade layers or reinforced sections may be less vulnerable to freeze–thaw deterioration. Second, the pronounced sensitivity of the open system underscores the importance of drainage and water-control measures—such as lateral drainage layers, capillary breaks, and maintaining low groundwater tables—to prevent external water from feeding the freezing front. Third, while dynamic loading representative of high-speed train traffic does influence the early compression phase, its overall impact on frozen depth and heave is smaller than the influence of hydraulic boundary conditions. This observation highlights the need to prioritize water-management strategies in frost-prone railway foundations.

5. Conclusions

Although the laboratory tests idealize one-dimensional THM conditions and cannot fully represent field-scale heat transfer or long-term freeze–thaw cycling, this study investigated the frost-heave behavior of a coarse-grained Group A subgrade soil under static and dynamic loading in both open- and closed-system freezing. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Hydraulic conditions governed frost susceptibility. Open-system freezing increased frozen depth from 9–13 cm to 12–16 cm and frost heave from 1–2 mm to 2–4.5 mm due to sustained external water supply, enhanced water migration, and more continuous ice-lens formation.

(2) Vertical stress mainly affected the early compression stage but had limited impact on internal temperature profiles after the freezing-transition stage. Nevertheless, load significantly suppressed frost heave: increasing stress from 14.75 to 61 kPa reduced heave by 40–60% and decreased frozen depth by 2–4 cm due to lower permeability and restricted water migration. Under identical conditions, deformation followed: no load > dynamic load > static load, and the dynamic frequency (0.5–3 Hz) altered deformation by <10%, indicating that coarse soils respond primarily to the mean stress rather than cyclic components.

(3) Lower upper-plate freezing temperatures deepened frozen fronts and increased frost-heave ratios. After freezing, water content increased slightly in the frozen zone and decreased in the unfrozen zone. Both freezing temperature and applied load influenced vertical water redistribution, with higher loads reducing water accumulation near the freezing front.

(4) Relative to fine-grained materials, the coarse-grained soil exhibited a shorter compression stage (3–5 h), smaller overall heave, and weaker ice-lens development due to limited suction and reduced water-migration pathways. This confirms that coarse and fine soils follow fundamentally different frost-heave mechanisms.

(5) These experimental results support the suitability of coarse-grained fills in cold regions, provided that water infiltration is well controlled. Effective surface and subsurface drainage and sufficient confining stress are important in controlling frost deformation in coarse-grained HSR subgrades.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and G.S.; methodology, Q.L.; software, Q.W.; validation, Q.W.; formal analysis, Y.X. and G.S.; investigation, Q.W.; resources, Q.W.; data curation, Q.W.; writing original draft preparation, Q.W.; writing—review and editing, Q.W.; visualization, Q.W.; supervision, Q.W.; project administration, Y.X. and G.S.; funding acquisition, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42473059, 42161026 and 41801046) and the Transportation Science and Technology Project of Qinghai Province, China (No. 2025–02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will supply the relevant data in response to requests.

Acknowledgments

Generative AI tool (ChatGPT) were used only to improve the clarity and language of the manuscript. No content, data analysis, or scientific interpretation was generated by AI. The authors take full responsibility for the originality and accuracy of all scientific content.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yangyang Xie, Gang Song and Qiang Li are employed by the China Communications First Public Bureau Sixth Engineering Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CS | Closed system |

| OS | Open system |

References

- Miller, R.D. Freezing and heaving of saturated and unsaturated soils. Highw. Res. Rec. 1972, 393, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan, R.L. Analysis of coupled heat-fluid transport in partially frozen soil. Water Resour. Res. 1973, 9, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, J.-M.; Morgenstern, N.R. A mechanistic theory of ice lens formation in fine-grained soils. Can. Geotech. J. 1980, 17, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopke, S. A model for frost heave including overburden. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 1980, 3, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Pei, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, J. Study on theory model of hydro-thermal–mechanical interaction process in saturated freezing silty soil. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 78, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, F.; Li, D.-Q. A model of migration potential for moisture migration during soil freezing. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2016, 124, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, J. Experimental study on frost action of fine-grained soils under dynamic and static loads. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2010, 32, 1882–1887. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, D.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J. Assessing frost susceptibility of soils using PCHeave. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2013, 95, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z. The experiment study of frost heave characteristics and gray correlation analysis of graded crushed rock. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2016, 126, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, H.; Liu, J.; Luo, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhan, Y. Assessing frost heave susceptibility of gravelly soils based on multivariate adaptive regression splines model. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 181, 103182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Yang, C.; Ma, W.; Han, D.; Shang, F.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y. Water accumulation unrelated to ice segregation near the freezing front during soil freezing: Implications for frost heave in high-speed railway embankments and ground ice formation. CATENA 2024, 243, 108189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Ma, G.; Chen, G. A micro frost heave model for porous rock considering pore characteristics and water saturation. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 166, 106029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cai, G.; Zhou, C.; Yang, R.; Li, J. Thermo-hydro-mechanical coupled model of unsaturated frozen soil considering frost heave and thaw settlement. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 217, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dai, F. A frost heave pressure model for fractured rocks subjected to repeated freeze-thaw deterioration. Eng. Geol. 2024, 337, 107587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ren, J.; Ye, W.; Li, C.; Xu, G.; Liu, W.; Deng, S. The influence of uneven frost heave and thermal conditions on the deformation and damage of slab track in seasonally frozen regions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 157, 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lin, Z.; Niu, F.; Fan, X.; Liu, M.; Li, C.; Shang, Y. Frost heave evaluation and prediction of high-speed railway subgrade with coarse filler in high altitude seasonal frozen region, northwest China. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 51, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Ma, W.; Feng, W.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, L. The mechanism of hydraulic pressure aggravates coarse-grained soil frost heave: Implication for frost prevention to high-speed railway subgrade. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 52, 101590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Deng, F.; Pei, W.; Wan, X.; You, Z.; Zhang, Z. Corrigendum to “Mitigating frost heave and enhancing mechanical performance of silty clay with sisal fibre and geopolymer” [Constr. Build. Mater. 447 (2024) 138120]. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 471, 140523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Cao, S.; Zhou, S.; Li, X.; Duan, J. Nonuniform frost heave of saturated porous rocks in cold regions during cyclic unidirectional freeze-thaw: Influence of the temperature gradient. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Grain size curve of soil.

Figure 1.

Grain size curve of soil.

Figure 2.

Group A soil taken from HSR.

Figure 2.

Group A soil taken from HSR.

Figure 3.

Frost heave experiment with loading apparatus.

Figure 3.

Frost heave experiment with loading apparatus.

Figure 4.

Dynamic loads when f = 1 Hz.

Figure 4.

Dynamic loads when f = 1 Hz.

Figure 5.

Temperature of Group A soil with load in closed system. (a) cooling and freezing curve. (b) internal temperature.

Figure 5.

Temperature of Group A soil with load in closed system. (a) cooling and freezing curve. (b) internal temperature.

Figure 6.

Temperature profile of Group A Soil with time and loads in closed system. (a) Different time. (b) Different static loads.

Figure 6.

Temperature profile of Group A Soil with time and loads in closed system. (a) Different time. (b) Different static loads.

Figure 7.

Frozen depth of Group A soil with loads. (a) Static load (37.5 kPa) in closed system. (b) Dynamic load (30.5 + 29.5 sin(2·3.14·t)) in open system. (c) Load form. (d) Load frequency with 30.5 + 29.5 sin(2·3.14·f·t).

Figure 7.

Frozen depth of Group A soil with loads. (a) Static load (37.5 kPa) in closed system. (b) Dynamic load (30.5 + 29.5 sin(2·3.14·t)) in open system. (c) Load form. (d) Load frequency with 30.5 + 29.5 sin(2·3.14·f·t).

Figure 8.

Deformation of Group A soil with load in closed and open system. (a) Closed system. (b) Open system.

Figure 8.

Deformation of Group A soil with load in closed and open system. (a) Closed system. (b) Open system.

Figure 9.

Deformation of Group A soil under various thermal and loading conditions. (a) Upper plate freezing temperature. (b) Load form. (c) Static load. (d) Dynamic load.

Figure 9.

Deformation of Group A soil under various thermal and loading conditions. (a) Upper plate freezing temperature. (b) Load form. (c) Static load. (d) Dynamic load.

Figure 10.

Influence of load frequency on deformation of Group A soil.

Figure 10.

Influence of load frequency on deformation of Group A soil.

Figure 11.

Water content distribution of Group A soil with load. (a) temperature. (b) load form. (c) Load magnitude. (d) Load frequency.

Figure 11.

Water content distribution of Group A soil with load. (a) temperature. (b) load form. (c) Load magnitude. (d) Load frequency.

Figure 12.

Influence of temperature on frost-heave ratio of Group A soil with load.

Figure 12.

Influence of temperature on frost-heave ratio of Group A soil with load.

Figure 13.

Influence of load magnitude on frost-heave ratio of Group A soil. (a) static load. (b) dynamic load.

Figure 13.

Influence of load magnitude on frost-heave ratio of Group A soil. (a) static load. (b) dynamic load.

Figure 14.

Deformation of fine fine-grained soil. (a) Closed system. (b) Open system.

Figure 14.

Deformation of fine fine-grained soil. (a) Closed system. (b) Open system.

Figure 15.

Sample of fine and coarse-grained soil after freezing. (a) Fine-grained soil. (b) oarse-grained soil.

Figure 15.

Sample of fine and coarse-grained soil after freezing. (a) Fine-grained soil. (b) oarse-grained soil.

Table 1.

Definition of the Group A, B, C soil.

Table 1.

Definition of the Group A, B, C soil.

| Soil | Soil Type | Gradation | Fine Content |

|---|

| A | medium sand, coarse sand, gravel, fine gravel, coarse gravel | well-graded | <5% |

| well-graded | 5~15% |

| B | gravel, coarse gravel, fine gravel, coarse sand, medium sand, fine sand | well-graded | <5% |

| gravel, coarse gravel, medium sand | well-graded | 5~15% |

| gravel, coarse gravel, fine gravel | / | >15% |

| fine sand | well-graded | <5% |

| / | 5~15% |

| C | gravel, coarse gravel, fine gravel | / | >30% |

| fine soil with low liquid limit | | >50% |

Table 2.

Physical parameters of the tested soil mixture.

Table 2.

Physical parameters of the tested soil mixture.

| Coarse-Grained Soil | D10 | D30 | D60 | Cu | Cc | Liquid Limit (%) | Plastic Limit | Plasticity Index | Optimal Water Content

(%) | Maximum Dry Density

(g/cm3) |

|---|

| Group A soil | 8 | 30 | 1.2 | 0.055 | 0.94 | 29 | 21.2 | 7.8 | 7 | 2.2 |

Table 3.

Test program.

| Test | Load

(kPa) | Frequency

(Hz) | Upper Plate Freezing Temperature (°C) | Water Supply |

|---|

Static

load | 14.75 | - | −5.5 | Closed, Open |

| 30.5 | - | −3 | Closed, Open |

| −5.5 |

| −7.5 |

| 61 | - | −5.5 | Closed |

Dynamic

load | | 1 | −5.5 | Closed |

| 0.5 | −5.5 |

| 1 | −3 | Closed, Open |

| −5.5 |

| −7.5 |

| 3 | −5.5 | Closed |

| 1 | −5.5 |

Table 4.

Result of frost heave of Group A soil with load.

Table 4.

Result of frost heave of Group A soil with load.

| Soil | Temperature

(°C) | Load

(kPa) | Frost-Heave Deformation

(mm) | Frozen Depth

(cm) | Frost-Heave Ratio (%) |

|---|

| CS | OS | CS | OS | CS | OS |

|---|

Group A

soil | −3 | Static load 30.5 | 0.76 | 1.08 | 6.3 | 5.85 | 1.21 | 1.85 |

| −5.5 | Static load 30.5 | 1.45 | 2.52 | 9.68 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 2.65 |

| −7.5 | Static load 30.5 | 2.26 | 3.19 | 13.46 | 11.5 | 1.68 | 2.77 |

| −3 | Dynamic load 30.5 + 29.5 sint | 0.9 | 2.15 | 7.1 | 6.8 | 1.27 | 3.16 |

| −5.5 | Dynamic load 30.5 + 29.5 sint | 1.85 | 3.46 | 10.01 | 10.22 | 1.85 | 3.39 |

| −7.5 | Dynamic load 30.5 + 29.5 sint | 2.75 | 4.5 | 12.89 | 12.5 | 2.13 | 3.6 |

| −5.5 | Static load 14.75 | 1.89 | 3.66 | 9.6 | 9.39 | 1.97 | 3.9 |

| Static load 61 | 0.17 | 1.99 | 9.9 | 9.67 | 0.17 | 2.06 |

| Dynamic load 30.5 + 14.75 sint | 2.68 | 4.33 | 10.69 | 10.46 | 2.51 | 4.14 |

| Dynamic load 61 + 14.75 sint | 1.13 | 2.51 | 10.4 | 10.15 | 1.09 | 2.47 |

| No load | 3.24 | 6.71 | 9.28 | 9.23 | 3.49 | 7.27 |

| 0.5 Hz Dynamic load 30.5 + 29.5 sint | 1.8 | 3.42 | 10.2 | 10.04 | 1.73 | 3.41 |

3 Hz

Dynamic load 30.5 + 29.5 sint | 1.92 | 3.51 | 10.63 | 10.31 | 1.81 | 3.4 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).