Investigation on Seakeeping of WTIVs Considering the Effect of Leg-Spudcan Well

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Seakeeping Test Methods for the WTIV

2.1. Coordinate System and Wave Direction Definition

- ➢

- Head Wave: Angle between wave direction and ship heading is between ±165° and ±180°.

- ➢

- Following Wave: Angle between wave direction and ship heading is between ±0° and ±15°.

- ➢

- Beam Wave: Angle between wave direction and ship heading is between ±75° and ±105°.

- ➢

- Bow Quartering Wave: Angle between wave direction and ship heading is between ±105° and ±165°.

- ➢

- Stern Quartering Wave: Angle between wave direction and ship heading is between ±15° and ±75°.

2.2. Test Content and Procedure

- (1)

- Free Roll Decay Tests in Calm Water

- (2)

- Zero-Speed White Noise Wave Model Tests

- (3)

- Irregular Wave Model Tests in Operational Sea States

- (1)

- Wave absorbers at the tank end and sides, which demonstrated effective wave absorption performance.

- (2)

- A locally adjustable false bottom, allowing the water depth to be varied from 0 to 5 m.

- (3)

- A towing carriage with a maximum speed of 9 m/s.

- (4)

- A data acquisition and real-time analysis system.

- (1)

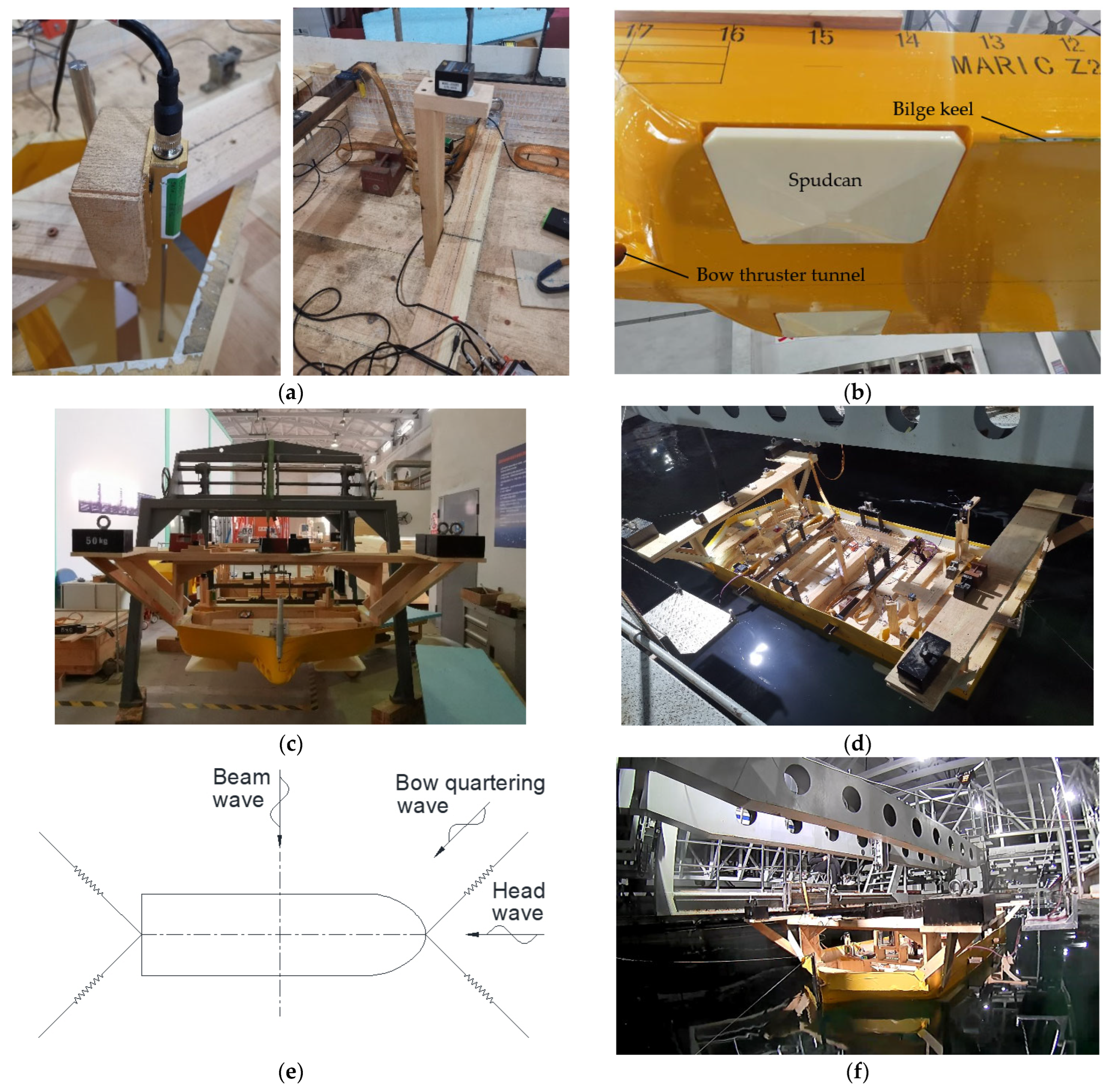

- A non-contact optical 6-DOF motion measurement system, used to measure the ship model’s six-degree-of-freedom motions, with an uncertainty of <0.1° in rotation and <1 mm in displacement.

- (2)

- Resistance-type wave probes, used to measure wave height and relative wave elevation at the legs, as shown in Figure 2a, with a measurement uncertainty of <0.1%.

- (3)

- Tri-axial accelerometers were installed at the center of gravity, legs, crane, helideck, and other critical locations, as shown in Figure 2a, with a measurement uncertainty of <0.5%.

- (4)

- Cameras and photographic equipment, used to document the testing process and support motion trajectory verification.

2.3. Test Model Construction

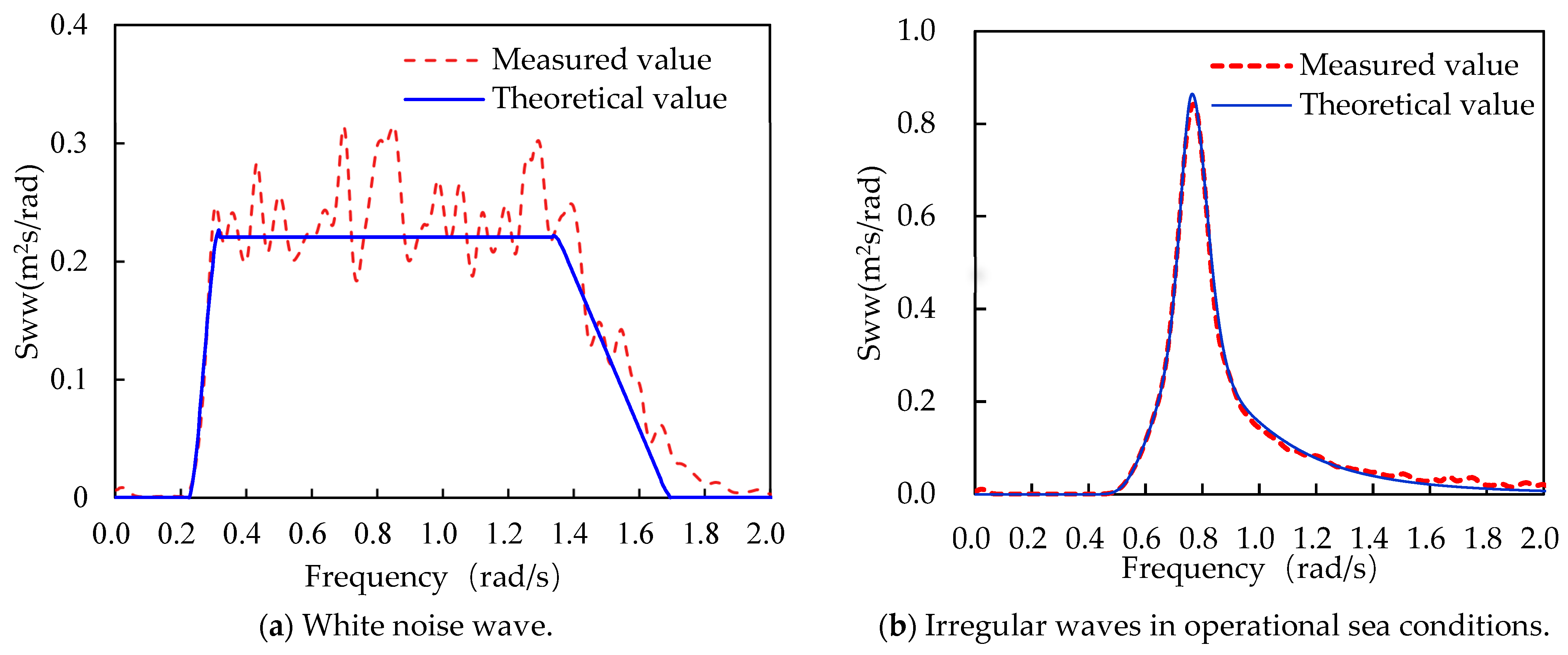

2.4. Wave Simulation

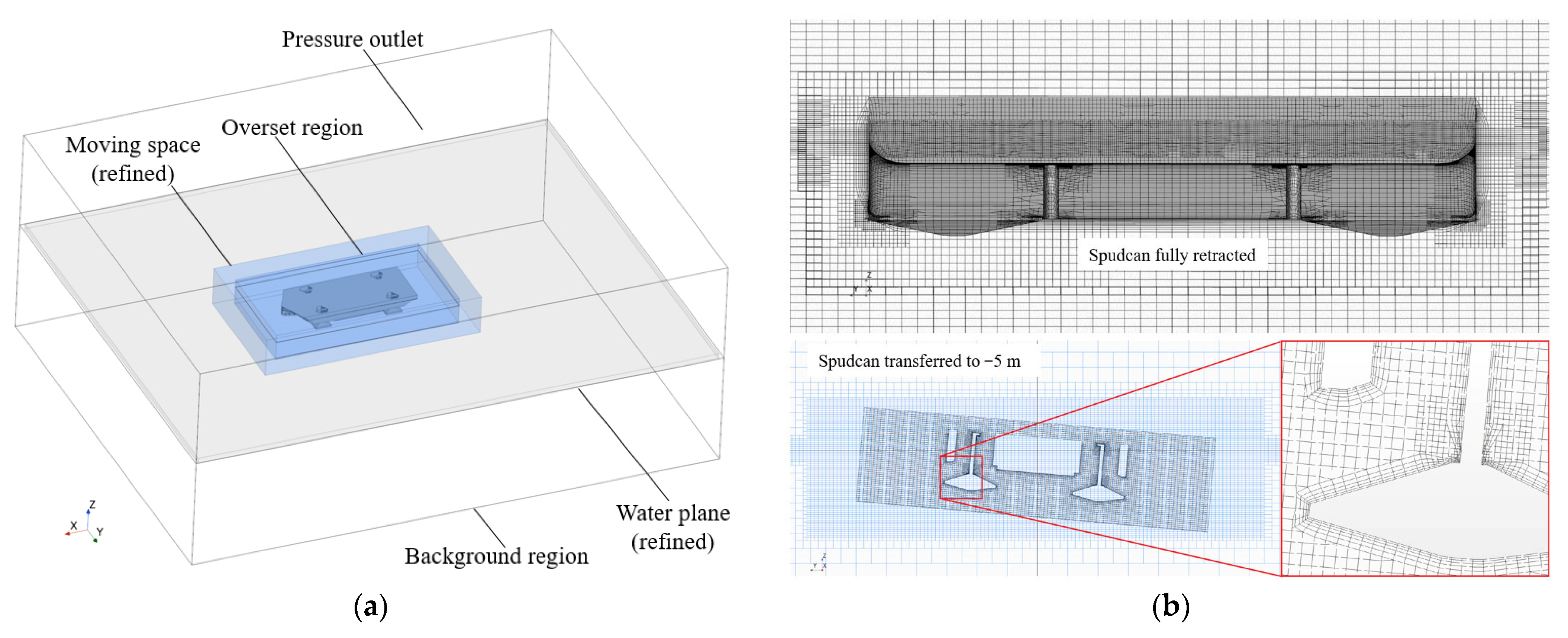

3. 3D Numerical Towing Tank Simulation Method Based on CFD

3.1. Numerical Wave Generation Theory

3.2. Numerical Wave Absorption Method

3.3. Free Motion Governing Equations

3.4. Static Water Roll Damping Calculation Model

3.5. Motion Response Calculation Model

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Roll Damping Characteristics Analysis of WTIV

4.1.1. Benchmark Condition Validation

- (1)

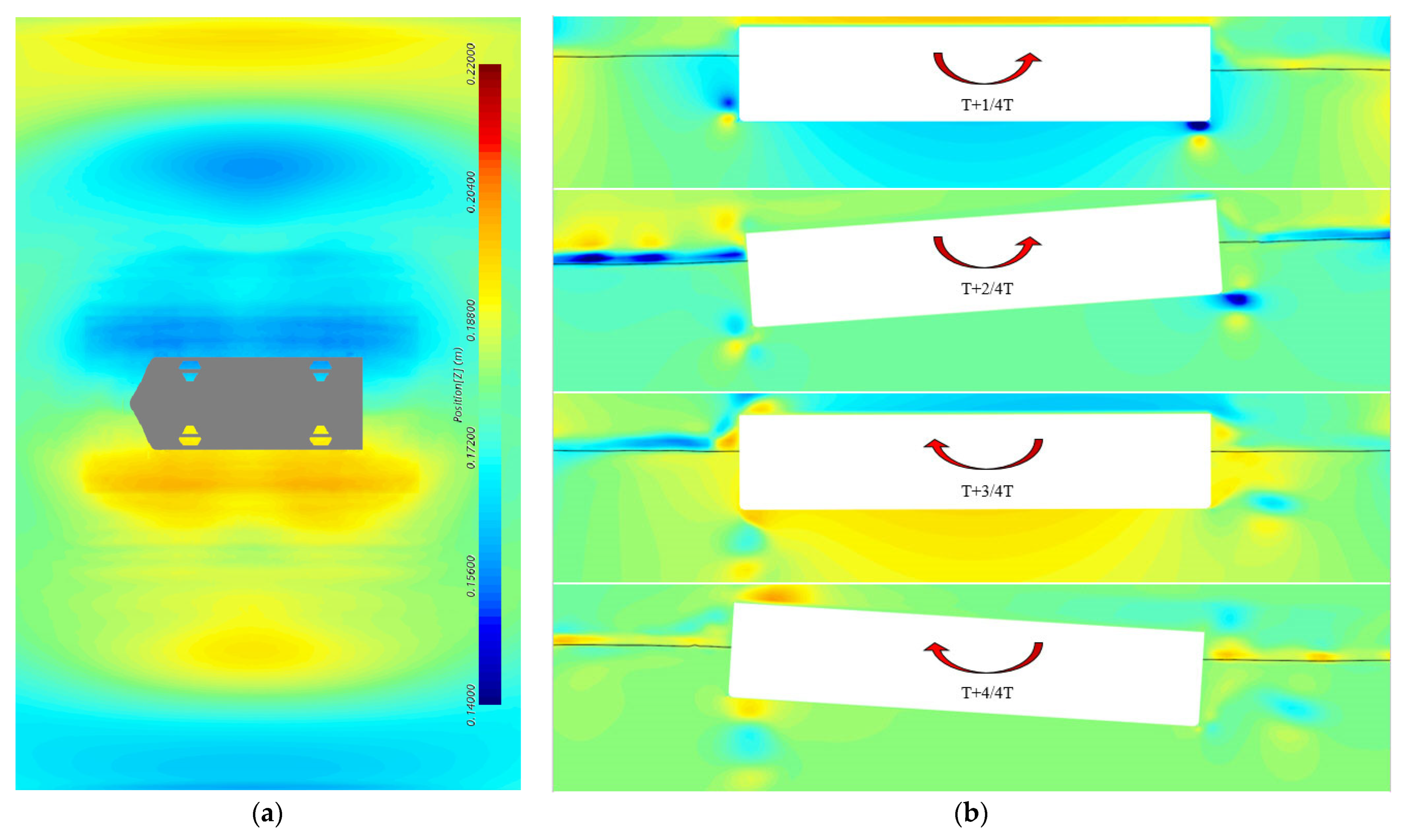

- The wave has been fully dissipated before reaching the boundary, with no signs of reflected waves. The peak spacing (about 3.0 m) is significantly smaller than the theoretical wavelength (about 12.6 m) calculated based on the roll period, indicating that the radiation wave generated by the hydrostatic roll free decay test is a short-term transient wave, rather than a continuous gravity wave. The change in free surface wave height is shown in Figure 5a.

- (2)

- The vortex is generated at the downstream side of the bilge corner, promptly detaches from the hull during the roll process, and develops in the near-field region. Due to the small size of the bilge keel of the ship, the generated vortices are not particularly strong. Figure 5b shows the evolution of the flow field at the hull’s mid-ship section and the bilge keel area during a roll cycle.

- (3)

- The CFD results in the first two cycles are basically consistent with the experimental data. Starting from the third cycle, a phase difference between the CFD and test results gradually emerges. As time progresses, the phase error accumulates, and the amplitude decay rate in the CFD simulation is faster than that of test. The free decay curves of roll in still water are shown in Figure 6. The average decay rates from the CFD predictions and model test results are 0.8972 and 0.9176, respectively, with a difference of 0.0205 (corresponding to approximately 2.23%). The RMSE of the peak points is 1.1194 deg, mainly due to the difference in the initial roll angle.

4.1.2. Leg Laying Down Condition Analysis

- (1)

- In Case_0 (spudcans fully retracted), fluid exchange between the well and the exterior is restricted. This results in a higher liquid level inside the starboard well than the external free surface, with the opposite occurring on the port side. The fluid inside the well generates a counterclockwise restoring moment, which significantly counteracts the port-side rolling tendency. Consequently, the well structure in Case_0 functions similarly to a free-flooding anti-roll tank, shortening the roll period by approximately 7% and increasing the roll damping by about 58%—even exceeding the damping achieved in Case_5, which has a lower center of gravity.

- (2)

- In Case_5 (spudcans lowered 5 m), the opening to the sea is sufficiently large, allowing rapid fluid exchange between the well and the exterior. The free liquid surfaces inside the port and starboard wells remain largely level with the external sea surface. As a result, the anti-rolling effect of the well structure diminishes, and the roll damping becomes significantly lower than in Case_0.

4.2. Motion Response Characteristics of WTIV

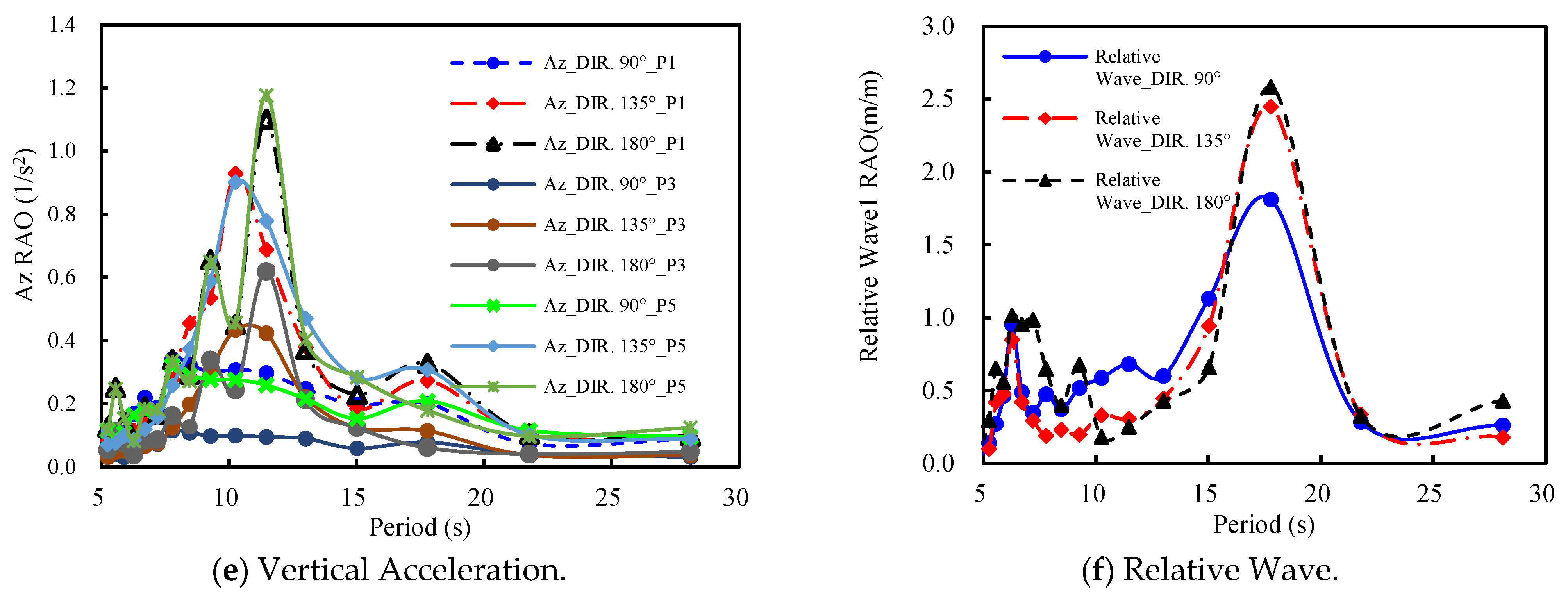

4.2.1. Characteristics of RAO

4.2.2. Irregular Wave Response Validation

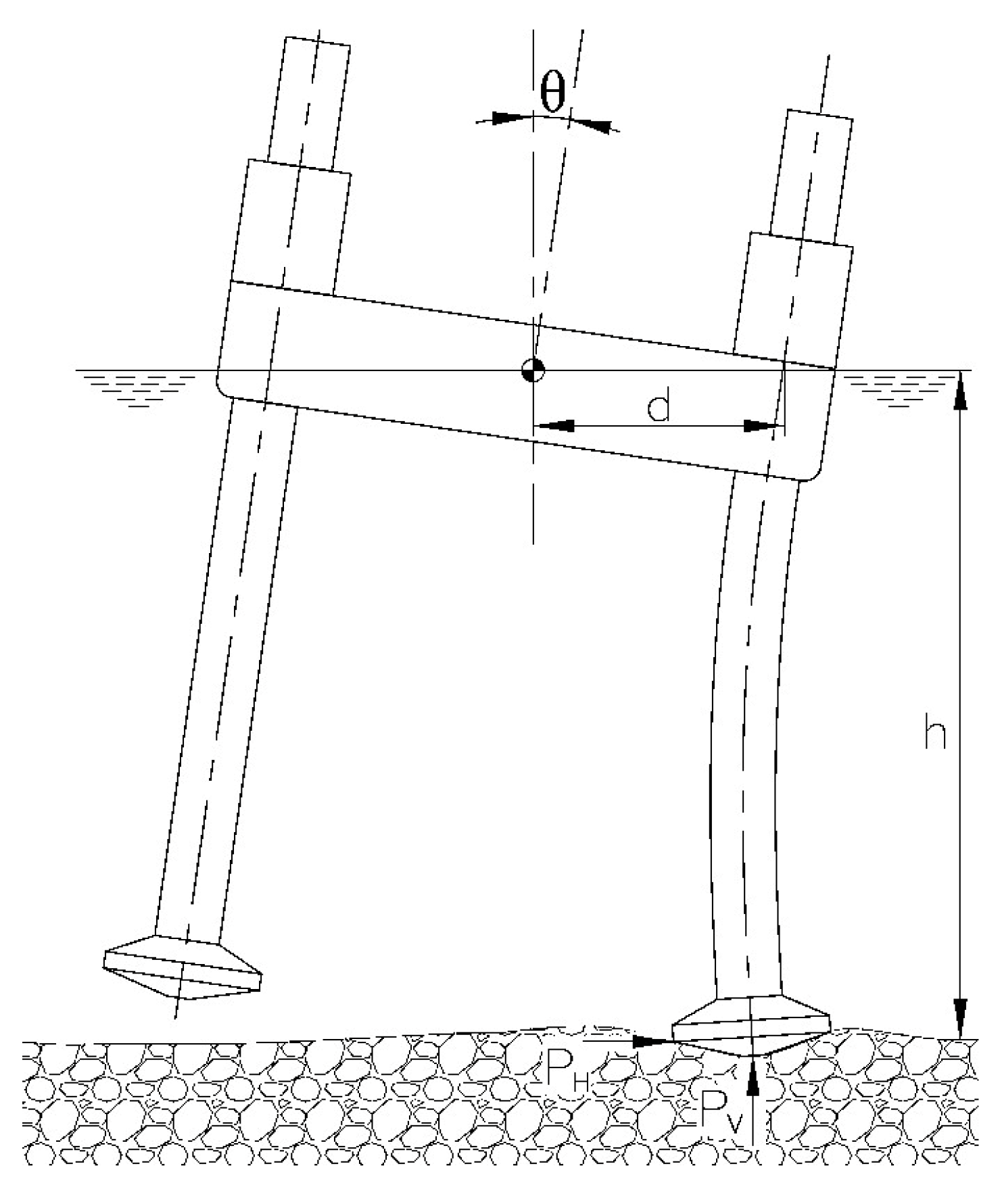

- (a)

- Only a single leg is in contact with the seabed;

- (b)

- All impact energy is absorbed by a single spudcan-leg-jacking system;

- (c)

- The instantaneous motion of the spudcan is arrested, and the seabed is considered an infinitely rigid body (i.e., the actual geological characteristics of rock, sand, or clay are ignored).

4.2.3. Seakeeping Evaluation and Operational Implications for WTIV

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The damping coefficient and natural roll period are fundamental parameters for WTIV motion analysis. This study, by fully accounting for fluid viscosity effects, quantifies for the first time the linear relationship between leg lowering depth and roll damping: the damping coefficient increases with a gradient of 0.04% per meter of lowering depth. Concurrently, as the leg is lowered and the hull’s center of gravity is reduced, the natural roll period exhibits an increasing trend.

- (2)

- In addition to fluid viscosity effects, the nonlinear characteristics of roll motion are determined by the WTIV’s cross-sectional shape, spudcan volume, and well structure. Through model tests and collaborative CFD verification, this study reveals the dual-mode effect of the additional moment of inertia () from the fluid in the spudcan well area on damping characteristics. When the leg is fully retracted, damping is enhanced by approximately 58%, and the roll period is shortened by about 7%.

- (3)

- A six-degree-of-freedom Response Amplitude Operator (RAO) frequency response model based on viscous flow theory was established. The prediction error for the extreme acceleration values at key positions is less than 10%, surpassing the accuracy limits of traditional potential flow theory. Specifically, while the potential-flow-theory-based RAO linear method is suitable for predicting motion and loads in small to moderate waves, its accuracy decreases under extreme sea states (characterized by high wave heights and large steepness) that induce large-amplitude ship motions and significant nonlinear effects (e.g., green water on deck and slamming). Under these conditions, the fully nonlinear time-domain approach considering fluid viscous effects, as presented in this study, becomes necessary for reliable simulation and analysis.

- (4)

- The distribution pattern of the extreme motion responses of the WTIV under different wave directions was revealed: the maximum responses of roll angle and lateral acceleration occur in bow quartering seas, contrary to the beam seas suggested by traditional theory. Combined with the response analysis results, a calculation method for the leg impact load during dynamic positioning (DP) operations is proposed. It is demonstrated that quartering and beam seas are the primary conditions leading to extreme vertical inertial acceleration loads, providing a critical basis for the strength design of key structures such as the leg-spudcan system, crane boom rests, and helideck.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiahou, M.; Yang, D.; Liu, H.; Shi, Y. Investigation on Calm Water Resistance of Wind Turbine Installation Vessels with a Type of T-BOW. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Lian, J. Review of integrated installation technologies for offshore wind turbines: Current progress and future development trends. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 255, 115319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Det Norske Veritas (DNV). DNV-RP-C104 Self-Elevating Units; DNV: Veritasveien, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lucintel. Report on the Current Situation and Future Prospects of China’s Offshore Wind Turbine Installation Vessel Industry (2024–2031); Lucintel: Irving, TX, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Sun, L.P.; Zhao, Z.J.; Zhang, L.J. Motion Response Analysis and Model Test Research of Wind Turbine Installation Vessel. Ship Stand. Eng. 2016, 49, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. Research on Hull Line Optimization and Hydrodynamic Performance of Wind Turbine Installation Vessel. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.D.; Zheng, G.Y.; Chen, C.; Tang, Y.Y. Parametric Roll Analysis of KCS Container Ship Based on Potential Flow Theory. Ship Eng. 2022, 44, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J.L.; Huang, S.X.; Chen, C.H. Seakeeping Prediction of Ship in Short Crested Waves Based on RANS. Shipbuild. China 2020, 61, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Sun, S.Z.; Ren, H.L. Experimental Study on Seakeeping Performance of Large-Scale Ship Model in Coastal Wind Waves. Ship Sci. Technol. 2015, 37, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.F.; Chen, C.H. Hydrodynamic Performance Analysis of Offshore Wind Farm Operation and Maintenance Mother Ship Based on STAR-CCM+. Guangdong Shipbuild. 2024, 43, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Jia, L.; Chen, C. CFD Prediction of Ship Seakeeping Behavior in Bi-Directional Cross Wave Compared with in Uni-Directional Regular Wave. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 104, 102426. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.L.; Huang, Z.Q.; Tong, M.Y. Optimization Design of Bilge Keel for Ocean Squid Fishing Vessel Based on CFD Method. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2024, 19, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J. Research on Drag Reduction Optimization and Seakeeping Performance of Offshore Wind Catamaran Service Operation Vessel Based on CFD. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Ocean University, Dalian, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Irkal, M.A.; Nallayarasu, S.; Bhattacharyya, S. CFD Approach to Roll Damping of Ship with Bilge Keel with Experimental Validation. Appl. Ocean Res. 2016, 55, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianejad, S.; Lee, J.; Liu, Y.; Enshaei, H. Numerical Assessment of Roll Motion Characteristics and Damping Coefficient of a Ship. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devolder, B.; Stempinski, F.; Mol, A.; Rauwoens, P. Roll Damping Simulations of an Offshore Heavy Lift DP3 Installation Vessel Using the CFD Toolbox OpenFOAM. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Houston, TX, USA, 1–5 June 2020; p. V008T08A045. [Google Scholar]

- Ghamari, I.; Mahmoudi, H.R.; Hajivand, A.; Seif, M.S. Ship Roll Analysis Using CFD-Derived Roll Damping: Numerical and Experimental Study. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2022, 21, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, R.B.; Shao, Y.; Walther, J.H. Experimental and CFD Analysis of Roll Damping of a Wind Turbine Installation Vessel. Appl. Ocean Res. 2024, 143, 103857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; He, Z.; Zang, J.; Chen, Q.; Ding, H.; Wang, G. Topographic Effects on Wave Resonance in the Narrow Gap between Fixed Box and Vertical Wall. Ocean Eng. 2019, 180, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Walther, J.H.; Shao, Y. Higher-Order Gap Resonance between Two Identical Fixed Barges: A Study on the Effect of Water Depth. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 052113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Chen, J.; Shao, Y.; Yu, X. CFD-Assisted Linearized Frequency-Domain Analysis of Motion and Structural Loads for Floating Structures with Damping Plates. Ocean Eng. 2023, 281, 114924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.B.; Liu, Y.Z. Ship Theory (Volume 2); Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: Shanghai, China, 2008; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.L. Research on Slamming Load Characteristics of the Seventh Generation Ultra-Deepwater Drilling Platform. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, Zhenjiang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens. Simcenter STAR-CCM+ User Guide, 2022.1; Software User Manual, Siemens Digital Industries Software: Plano, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; He, J.Y. Ship Resistance and Free Motion Prediction Based on RANS Method. Ship Eng. 2019, 41, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Xiahou, M.; Yang, D.; Kang, W.; Chi, J.; Cheng, W. Method for the Operational Weather Window Assessment of Self-Elevating Wind Turbine Installation Vessels. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Ships and Electromechanical System, Guangzhou, China, 27–29 December 2024; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hanlon, J.F.; McCauley, M.E. Motion sickness incidence as function of the frequency and acceleration of vertical sinusoidal motion. Aerosp. Med. 1974, 45, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Items | Full Scale | Test Model |

|---|---|---|

| Length overall Loa, m | 126 | 3.6 |

| Length on water line Lwl, m | 125 | 3.5714 |

| Breadth B, m | 50 | 1.4286 |

| Depth D, m | 10 | 0.2857 |

| Design draught d, m | 6.2 | 0.1771 |

| Block coefficient CB | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Displacement △, t | 32,530 | 0.7403 |

| Center of Gravity LCG, m | 62.5 | 1.7857 |

| Center of Gravity VCG, m | 20.1 | 0.5743 |

| Roll gyration radius Rxx, m | 26.87 | 0.7677 |

| Pitch gyration radius Ryy, m | 43.84 | 1.2526 |

| Yaw gyration radius Rzz, m | 40.25 | 1.15 |

| Measurement Location | Longitudinal Pos., m (from #0) | Transverse Pos., m (from Centerline, +ve Port) | Vertical Pos., m (from Baseline) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center of Gravity | 62.5 | 0 | 20.1 |

| Main Crane Rest P1 | 109.9 | 5.85 | 32.5 |

| Aux. Crane Rest P2 | 24 | −27.3 | 28.0 |

| Fwd. jacking case upper guide P3 | 97.7 | −20.8 | 20.4 |

| Aft. jacking case upper guide P4 | 22.5 | 12.15 | 20.4 |

| Helideck P5 | 120 | −20.8 | 29.5 |

| Peak Enhancement Factor γ | Significant Wave Height Hs (m) | Peak Period TP (s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Scale | Model test | Full-Scale | Model test | Full-Scale | Model test |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.80 | 0.051 | 8.21 | 1.39 |

| Mesh Size (mm) | Roll Period, T (s) Compare to Experimental Value (2.87 s) | Critical Damping, μ Compare to Experimental Value 0.0504 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFD Value | Deviation (%) | CFD Value | Deviation (%) | |

| 60.0 | 3.35 | 16.7 | 0.056 | 11.1 |

| 42.5 | 3.11 | 8.36 | 0.053 | 5.16 |

| 30.0 | 2.98 | 3.83 | 0.049 | −2.78 |

| 22.5 | 3.00 | 4.53 | 0.050 | −0.79 |

| Time Step (ms) | Roll Period, T (s) Compare to Experimental Value (2.87 s) | Critical Damping, μ Compare to Experimental Value 0.0504 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFD Value | Deviation (%) | CFD Value | Deviation (%) | |

| 15.0 | 3.33 | 16.03 | 0.047 | −6.75 |

| 11.0 | 3.11 | 8.36 | 0.048 | −4.76 |

| 8.0 | 2.98 | 3.83 | 0.049 | −2.78 |

| 6.0 | 2.99 | 4.18 | 0.048 | −4.76 |

| Item | Model | Full Scale | Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | CFD | Experiment | CFD | ||

| Period (s) | 2.87 | 2.98 | 16.98 | 17.63 | 3.83% |

| Damping Coeff. | 0.0504 | 0.049 | 0.0504 | 0.049 | −2.78% |

| Case | Spudcan Location (m) | VCG (m) | Damping Coefficient, μ | Roll Natural Period T_CFD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case_0 | 0 | 20.1 | 0.049 | 17.630 |

| Case_5 | −5 | 19.2 | 0.033 | 18.789 |

| Case_10 | −10 | 18.2 | 0.035 | 18.627 |

| Case_20 | −20 | 16.4 | 0.039 | 18.418 |

| Wave Dir. | Motion | Significant Value | 1/100th Value | 1/1000th Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | CFD | Experiment | CFD | Experiment | CFD | PFM | ||

| 180° | Heave (m) | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.40 | - |

| Pitch (°) | 0.72 | 0.73 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.19 | 1.19 | - | |

| 135° | Heave (m) | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.43 | - |

| Pitch (°) | 0.81 | 0.95 | 1.49 | 1.48 | 1.72 | 1.63 | - | |

| Roll (°) | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.91 | |

| 90° | Heave (m) | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.88 | - |

| Roll (°) | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.97 | |

| Location | Significant Value | 1/100th Value | 1/1000th Value | Maximum Value | Wave Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center of Gravity | 0.074 | 0.128 | 0.138 | 0.162 | 90° |

| Main Crane Rest P1 | 0.361 | 0.623 | 0.676 | 0.683 | 135° |

| Aux. Crane Rest P2 | 0.285 | 0.467 | 0.515 | 0.561 | 90° |

| Fwd. jacking case upper guide P3 | 0.357 | 0.596 | 0.654 | 0.702 | 135° |

| Aft. jacking case upper guide P4 | 0.344 | 0.573 | 0.631 | 0.695 | 90° |

| Helideck P5 | 0.181 | 0.308 | 0.348 | 0.354 | 135° |

| Description | Ocean Transit | Coastal Transit | DP and Installation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Navy Crew | Light Manual Work | Heavy Manual Work | Demanding Work | |

| VAcc. | 0.275 g | 0.2 g | 0.15 g | MSI 10% * |

| Roll | 6° | 4° | 4° | 3° |

| Pitch | 3° | 2° | 1.5° | 1.5° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiahou, M.; Wei, Y.; Wu, J.; Liu, X.; Lu, W.; Yang, D. Investigation on Seakeeping of WTIVs Considering the Effect of Leg-Spudcan Well. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12701. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312701

Xiahou M, Wei Y, Wu J, Liu X, Lu W, Yang D. Investigation on Seakeeping of WTIVs Considering the Effect of Leg-Spudcan Well. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12701. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312701

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiahou, Mingsheng, Yuefeng Wei, Jinjia Wu, Xueqin Liu, Wei Lu, and Deqing Yang. 2025. "Investigation on Seakeeping of WTIVs Considering the Effect of Leg-Spudcan Well" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12701. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312701

APA StyleXiahou, M., Wei, Y., Wu, J., Liu, X., Lu, W., & Yang, D. (2025). Investigation on Seakeeping of WTIVs Considering the Effect of Leg-Spudcan Well. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12701. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312701