Seismic Data Enhancement for Tunnel Advanced Prediction Based on TSISTA-Net

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Introducing a reflection padding technique to effectively suppress boundary artifacts and improve the reconstruction quality of edge information;

- (2)

- Embedding a multi-scale dilated convolution module to expand the receptive field and enhance the capability to capture long-range correlated features in seismic signals;

- (3)

- Adopting lightweight and block-based processing strategies to enhance computational efficiency while ensuring reconstruction accuracy, thereby satisfying the demands of practical engineering applications.

2. Theory

2.1. Iterative Shrinkage Threshold Algorithm

2.2. Tunnel Seismic Iterative Shrinkage Threshold Algorithm Net

2.2.1. Iterative Shrinkage Threshold Algorithm Net

2.2.2. Dilated Convolution

2.2.3. Padding

2.3. Loss Function

3. Experiment

3.1. Model Construction

3.2. Dataset Construction

3.3. Evaluation Indicators

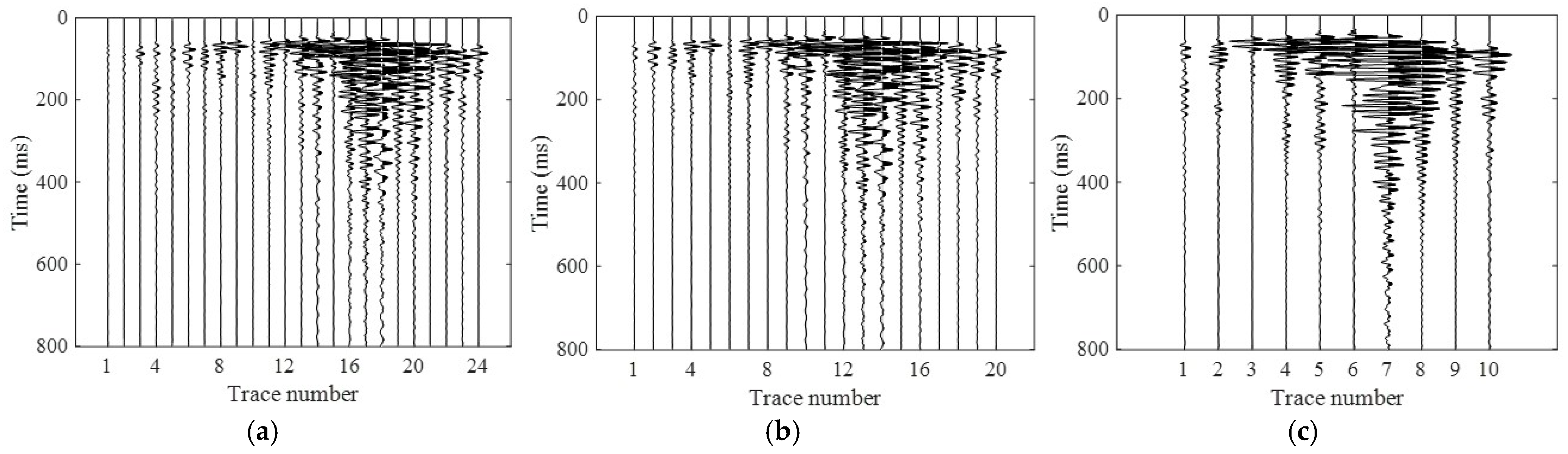

3.4. Synthetic Data Experiment

3.5. Real Data Experiment

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Existing Studies

4.2. Limitation

4.3. Future Work

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- A deep unfolding network architecture that incorporates reflection padding and multi-scale dilated convolution is proposed. The reflection padding operation effectively mitigates boundary artifacts, while the multi-scale dilated convolution substantially expands the receptive field, thereby enhancing the capability to model long-range dependencies and capture multi-scale seismic features. This design directly addresses the lack of global information modeling inherent in conventional networks such as U-Net.

- (2)

- High-precision and efficient tunnel seismic data reconstruction is achieved. TSISTA-Net significantly outperforms comparative methods in PSNR, SSIM and LCCC, particularly excelling in the restoration of high-frequency details and waveform continuity. Furthermore, its lightweight architecture and block-wise processing ensure low computational overhead, meeting practical efficiency requirements in engineering applications.

- (3)

- A novel approach for intelligent seismic data processing in tunnel engineering is established. This study confirms the effectiveness of integrating physics-informed algorithms with deep learning. TSISTA-Net not only offers strong interpretability but also demonstrates robust generalization performance, showing considerable promise for improving the reliability and practicality of tunnel advanced forecasting systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeng, Z. Tunnel Seismic Reflection Method for Advance Forecasting. Chin. J. Geophys. 1994, 37, 267–270. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Liu, B.; Sun, H.; Nie, L.; Zhong, S.; Su, M.; Li, X.; Xu, Z. Current Status and Development Trends in Advance Geological Forecasting for Tunnel Construction. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2001, 33, 1090–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Tan, Y. Application of Integrated Detection Technology in Advance Geological Forecasting for Tunnels. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2021, 48, 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Quan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z. Key Technology of TBM Excavation in Soft and Broken Surrounding Rock. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Massimino, M.R. Parametric analysis of the seismic response of coupled tunnel–soil–aboveground building systems by numerical modelling. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 15, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleska, T.; Beben, D.; Vaslestad, J.; Sukuvara, D.S. Application of EPS Geofoam below Soil–Steel Composite Bridge Subjected to Seismic Excitations. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2024, 150, 04024115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Jing, H.; Yang, X.; Rong, X.; Chen, W. Research Progress on the Mechanism of Major Water and Mud Inrush Disasters in Deep Long Tunnels and Their Prediction, Early Warning, and Control Theories. China Basic Sci. 2017, 19, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Spitz, S. Seismic trace interpolation in the F-X domain. Geophysics 1991, 56, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, G.; Hao, Z.; Zu, S.; Mi, F.; Chen, X. Multidimensional Seismic Data Reconstruction Using Frequency-Domain Adaptive Prediction-Error Filter. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 2326–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, J. Wave-equation trace interpolation. Geophysics 1987, 52, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomel, S. Seismic reflection data interpolation with differential offset and shot continuation. Geophysics 2003, 68, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, D. Inverse velocity stacking for multiple elimination. J. Can. Soc. Explor. Geophys. 1986, 22, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Duijndam, A.; Schonewile, M. Nonuniform fast Fourier transform. Geophysics 1999, 64, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, F.; Hennenfent, G. Non-parametric seismic data recovery with curvelet frames. Geophys. J. Int. 2008, 173, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oropeza, V.; Sacchi, M. Simultaneous seismic data denoising and reconstruction via multichannel singular spectrum analysis. Geophysics 2011, 76, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z. A Review of Seismic Data Reconstruction Methods. Prog. Geophys. 2013, 28, 1749–1756. [Google Scholar]

- Candes, E.J.; Tao, T. Near-optimal signal recovery from random projections: Universal encoding strategies. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2006, 52, 5406–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubechies, I.; Defrise, M.; De Mol, C. An iterative thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems with a sparsity constraint. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 2004, 57, 1413–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tao, C.; Chen, S.; Wu, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhou, J.; Qiu, L.; Shen, H.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y. High-precision seismic data reconstruction with multi-domain sparsity constraints based on curvelet and high-resolution Radon transforms. J. Appl. Geophys. 2019, 162, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Teboulle, M. A Fast Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm for Linear Inverse Problems. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2009, 2, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fu, L.; Zhang, M. Deep-seismic-prior-based reconstruction of seismic data using convolutional neural networks. Geophysics 2021, 86, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Tang, G.; Wang, S.; Lin, K.; Peng, R. Deep learning for irregularly and regularly missing 3-D data reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 6244–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Wu, B.; Zhu, X. Seismic data consecutively missing trace interpolation based on multistage neural network training process. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, J. Simultaneous denoising and interpolation of seismic data via the deep learning method. Earthq. Res. China 2019, 33, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Li, K. A Review of Deep Learning Methods for Seismic Data Reconstruction. Prog. Geophys. 2023, 38, 361–381. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ghanem, B. ISTA-Net: Interpretable optimization-inspired deep network for image compressive sensing. In Proceedings of the IEEE CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1828–1837. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xia, S.; Cui, H.; Wan, X. GSISTA-Net: Generalized structure ISTA networks for image compressed sensing based on optimized unrolling algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 6, 80373–80387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabi, R.R.; Monti, G. Genetic Algorithm-Based Model Updating in a Real-Time Digital Twin for Steel Bridge Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabi, R.R. Shear capacity assessment of hollow-core RC piers via machine learning. Structures 2025, 76, 108961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, J.S.; Dagommer, M.; Guo, J. Deep learning-based MRI reconstruction with Artificial Fourier Transform Network. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 192, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Hou, J.; Wang, T.; Guo, Q.; Li, D.; Pan, X. Efficient urban flood surface reconstruction: Integrating deep learning with hydraulic principles for sparse observations. J. Hydrol. 2025, 664, 134439. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.; Yang, S. Classification of seed maize using deep learning and transfer learning based on times series spectral feature reconstruction of remote sensing. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Luan, S.; Sun, H. Self-adaptive physics-driven deep learning for seismic wave modeling in complex topography. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Fan, C.; Xing, Y. Seismic data reconstruction based on low dimensional manifold model. Pet. Sci. 2021, 19, 518–533. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Ma, J. Can learning from natural image denoising be used for seismic data interpolation? Geophysics 2020, 85, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, S. A projection-onto-convex-sets network for 3D seismic data interpolation. Geophysics 2023, 88, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, D.; Gao, W. Group-based Sparse Representation for image restoration. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2014, 23, 3336–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Zi, J.; Chen, Y.; Jia, C.; Sun, Q. Real-time tunnel risk forecasting based on rock drill signals during construction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 166, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Ren, W.; Ye, H.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X.; Peng, Q. Simultaneous reconstruction and denoising of seismic data based on rank reduction and sparsity constraints. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2024, 48, 478–488. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Cao, J.; Yin, H.; Zhao, J.; Gao, K. Seismic Data Reconstruction based on Attention U-net and Transfer Learning. J. Appl. Geophys. 2023, 219, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Wang, C.; Geng, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Jia, J. Seismic data reconstruction via an adaptive feature fusion network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Das, A. Limitations of Mw and M Scales: Compelling Evidence Advocating for the Das Magnitude Scale (Mwg)—A Critical Review and Analysis. Indian Geotech. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Sharma, M.L. A seismic Moment Magnitude Scale. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2019, 109, 1542–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input: Observation data: b; Initial value: x(0) = 0; Observation Matrix: A; Regularization parameter: λ; Step: t; Number of iterations: Niter |

| For k = 1: Nite |

| End |

| Output: x(k+1) |

| Stratum Classification | Stratum-Related Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Wave Velocity vp (m/s) | S-Wave Velocity vs (m/s) | Density p (kg/m3) | Thickness Along the Tunnel Axis (m) | |

| Tunnel cavity | 340 | 0 | 1.29 | 50 |

| Tunnel surrounding rock | 3300~3700 | 1900~2150 | 2300~2400 | / |

| Karst cave | 1000~1400 | 600~900 | 1750~1900 | 2~4 |

| Fracture zone | 1800~2200 | 1000~1350 | 2000~2150 | 8~12 |

| Stratum | 3900~4300 | 2250~2400 | 2450~2510 | / |

| Method | Per-Sample Training Time | Per-Sample Inference Time | Memory Usage (GPU/CPU) | PSNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block | 0.088 s | 0.0015 s | 23.44 MB/ 1142.81 MB | 34.79 dB |

| Unblock | 1.8524 s | 0.0415 s | 31.15 MB/ 1725.05 MB | 32.07 dB |

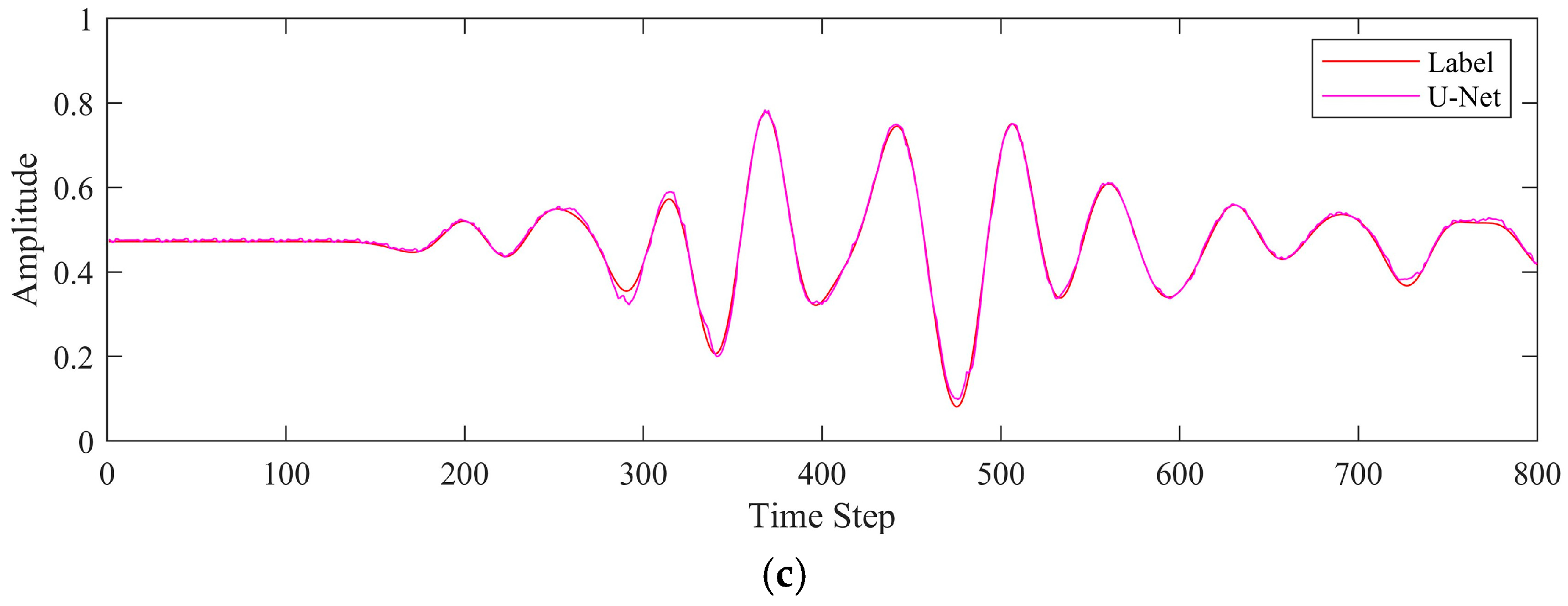

| TSISTA-Net | ISTA-Net | U-Net | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR (dB) | 37.28 | 34.04 | 35.93 |

| SSIM | 0.9667 | 0.9167 | 0.9480 |

| LCCC | 0.9357 | 0.8878 | 0.9087 |

| TSISTA-Net | ISTA-Net | U-Net | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR (dB) | 30.33 | 21.93 | 28.31 |

| SSIM | 0.8893 | 0.8087 | 0.8546 |

| LCCC | 0.8288 | 0.6981 | 0.7386 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, D.; Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Yan, W.; Chen, C.; Tao, X. Seismic Data Enhancement for Tunnel Advanced Prediction Based on TSISTA-Net. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312700

Feng D, Yang M, Wang X, Yan W, Chen C, Tao X. Seismic Data Enhancement for Tunnel Advanced Prediction Based on TSISTA-Net. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312700

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Deshan, Mengchen Yang, Xun Wang, Wenxiu Yan, Chen Chen, and Xiao Tao. 2025. "Seismic Data Enhancement for Tunnel Advanced Prediction Based on TSISTA-Net" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312700

APA StyleFeng, D., Yang, M., Wang, X., Yan, W., Chen, C., & Tao, X. (2025). Seismic Data Enhancement for Tunnel Advanced Prediction Based on TSISTA-Net. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312700