Industrial Metaverse and Technical Diagnosis of Electric Drive Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

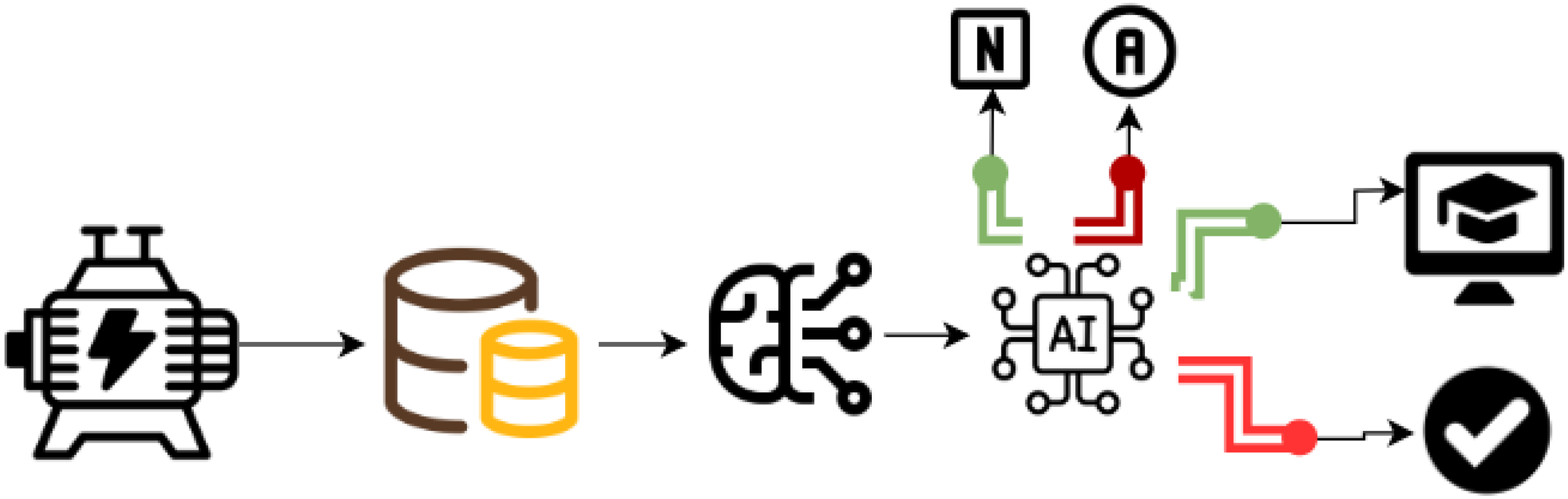

2. Materials and Methods

3. Experiments

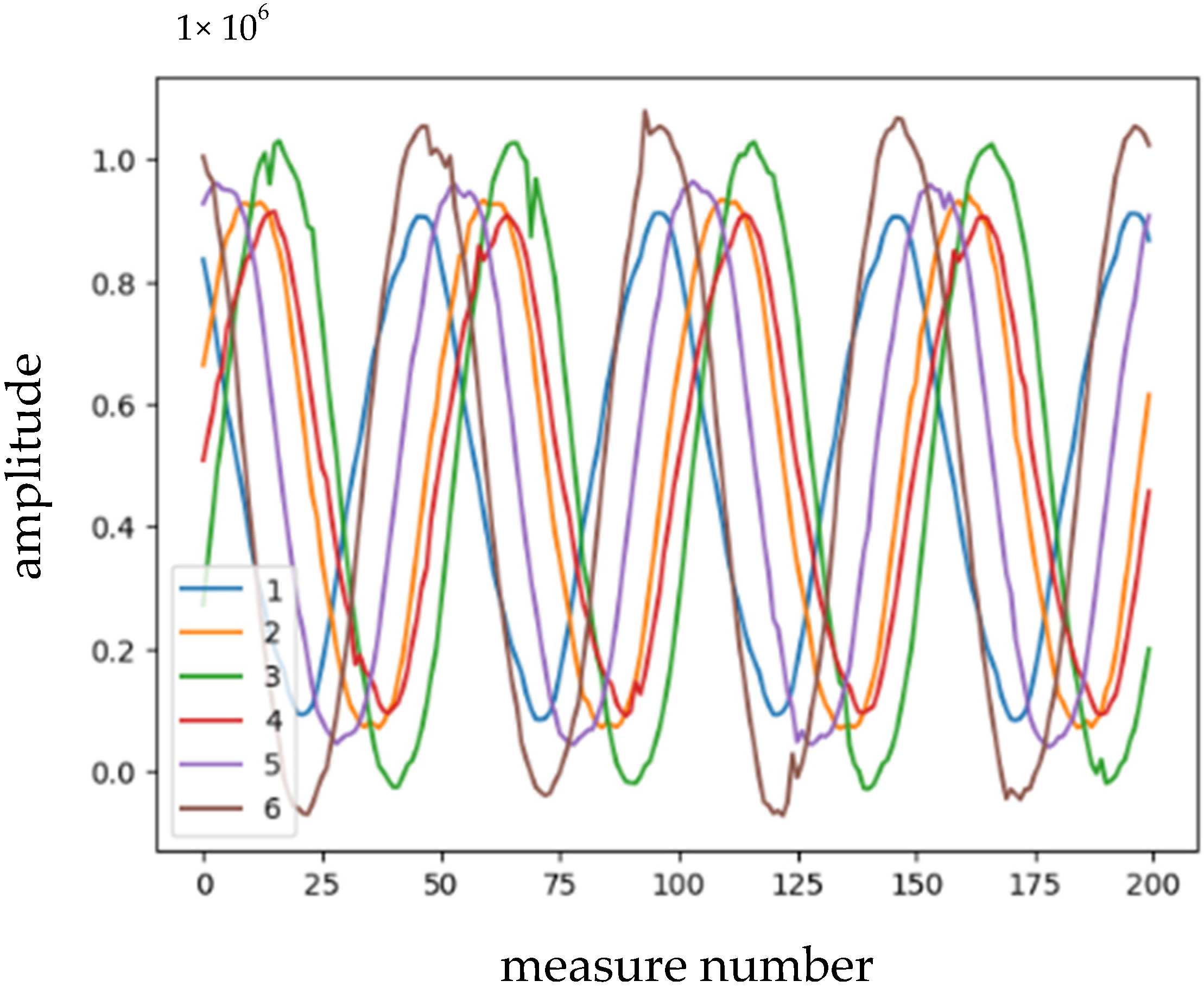

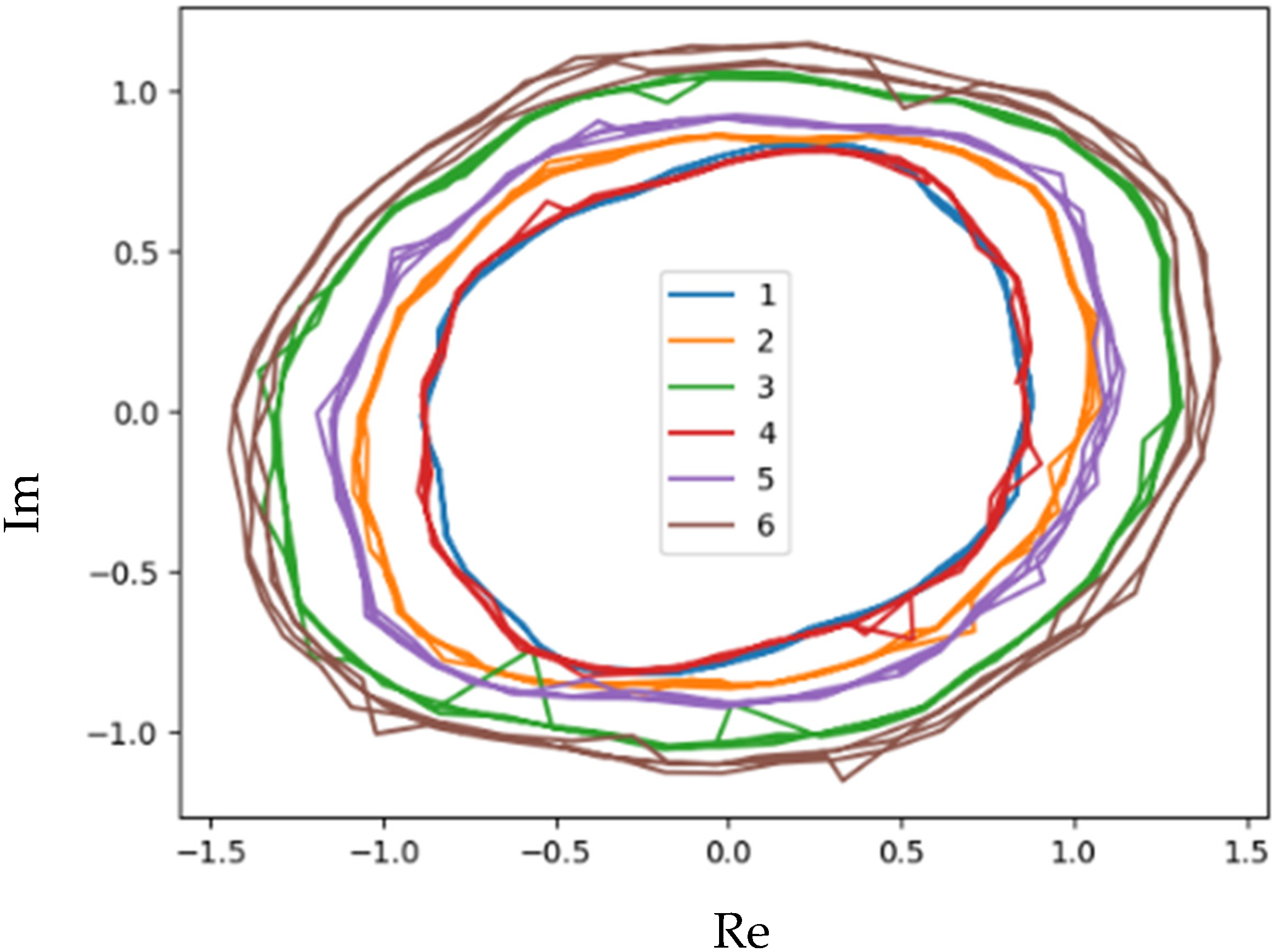

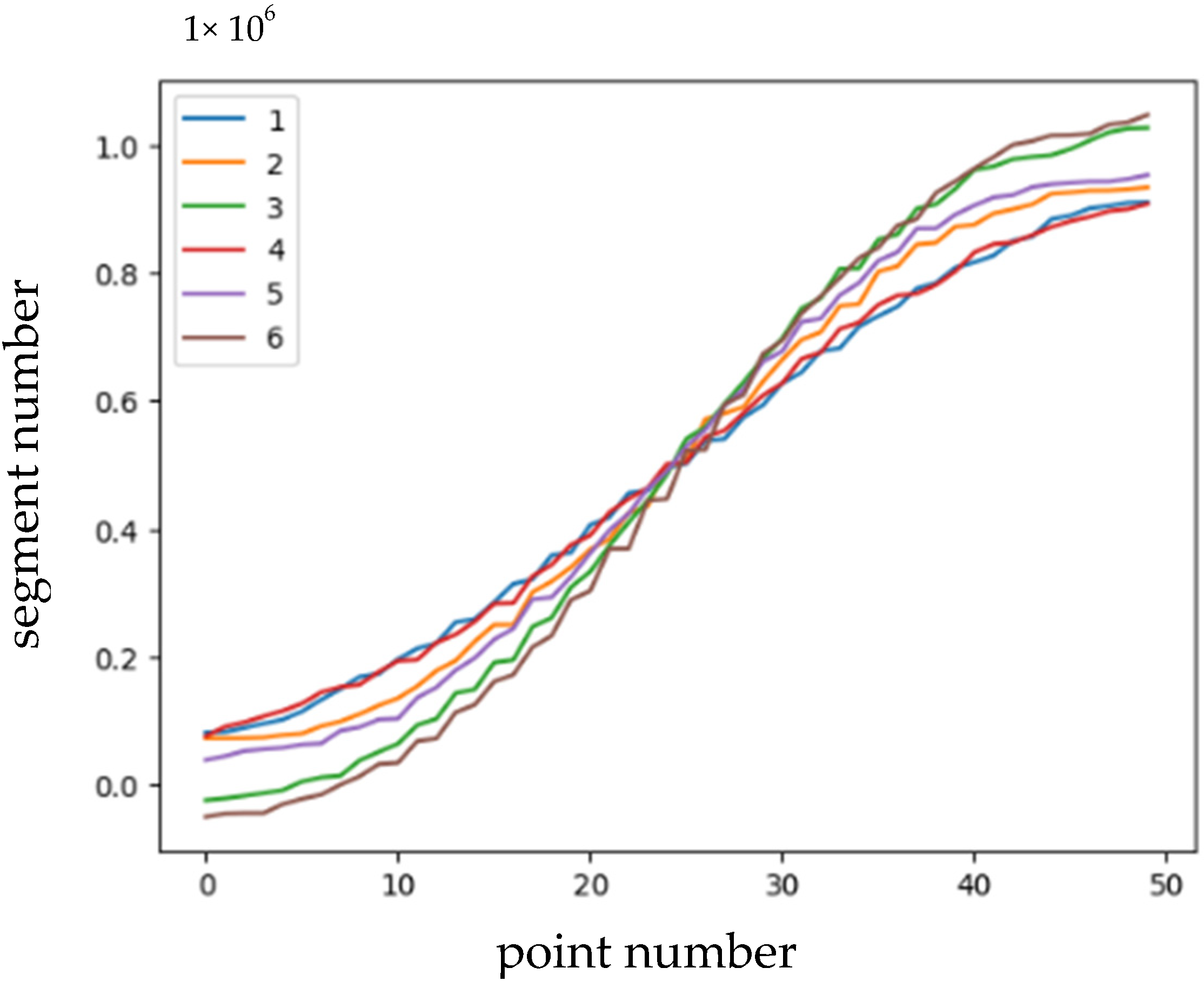

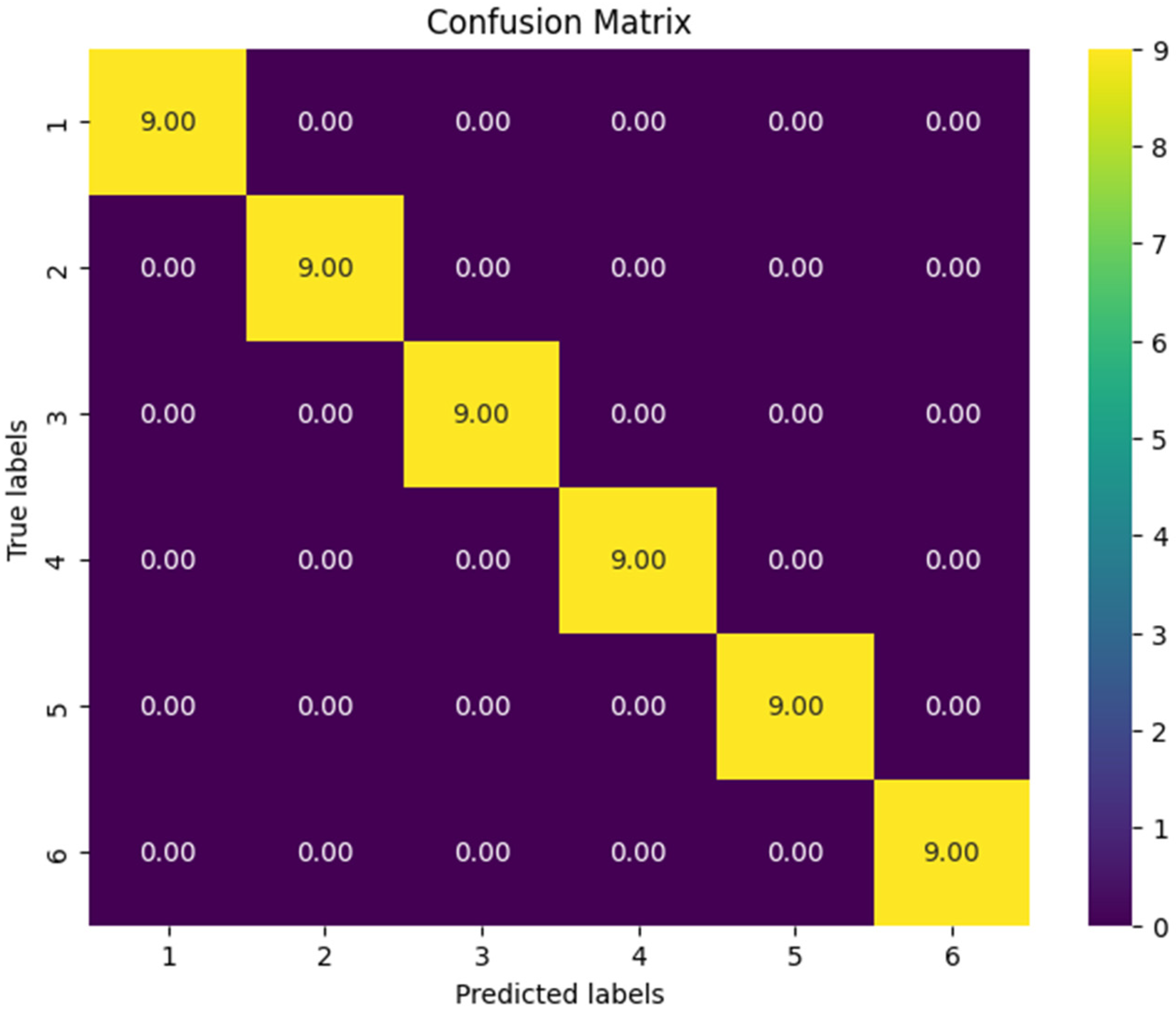

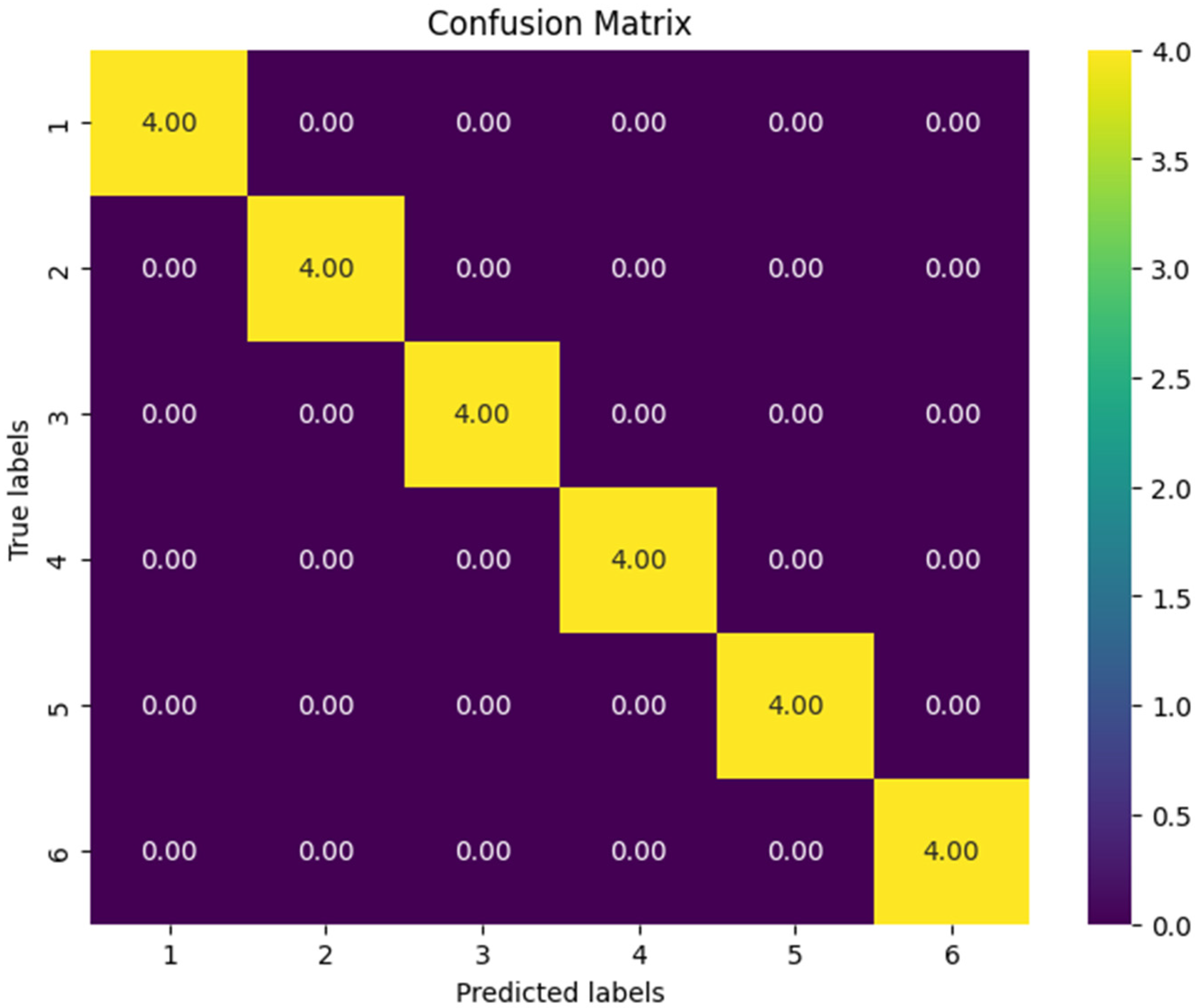

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yurievich, V.B.; Nguyen, T.H. Stochastic Pulse-Width Modulation and Modification of Direct Torque Control Based on a Three-Level Neutral-Point Clamped Inverter. Energies 2024, 23, 6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.S.; Sabry, A.H.; Hameed, H.K.; Uğurenver, A. Impact of pulse-width modulation techniques on inverter efficiency and motor current quality in permanent-magnet synchronous motor drives: A simulation study. Measurement 2025, 258, 119107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skamyin, A.N. Method for determining the harmonic contribution of consumer installations based on the application of passive filters. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 2464–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukovskiy, Y.L.; Buldysko, A.D.; Revin, I.I. Induction Motor Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on Singular Value Decomposition of the Stator Current. Energies 2023, 16, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandakumar, S.; Gunasekaran, S. Investigating inter-turn insulation fault detection and classification in adjustable motor drives using novel hybrid machine learning approach. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Smadi, T.; Gaeid, K.S.; Mahmood, A.T.; Hussein, R.J.; Al-Husban, Y. State space modeling and control of power plant electrical faults with neural networks for diagnosis. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowacz, A. Thermographic fault diagnosis of electrical faults of commutator and induction motors. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 121, 105962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulik, S.; Konar, P.; Chattopadhyay, P. Strategic fusion of horizontal frame vibration with stator current for improved fault diagnosis of variable frequency drive. Measurement 2025, 258, 119322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Han, L.; Shen, Y.; Yuan, W. Application of Fast High-Order Symmetric Difference Analytic Energy Spectrum Kurtosis for Wind Power Drive Chain Fault Localization. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 169, 105708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T.; Yang, M. Influence of motor rotor bending on vibration characteristics of electric drive system. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 236, 113009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Peng, Y.; Shang, W.; Kong, D. Open-circuit fault diagnosis in voltage source inverter for motor drive by using deep neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 120, 105866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacha, A.; El Idrissi, R.; Janati Idrissi, K.; Lmai, F. Comprehensive dataset for fault detection and diagnosis in inverter-driven permanent magnet synchronous motor systems. Data Brief 2025, 58, 111286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Kim, J.; Jang, K.; Yun, S.-H.; Lim, D.; Jin, M.; Park, Y.-H. Vibration, current, torque, RPM dataset for multiple fault conditions in industrial-scale electric motors under randomized speed and load variations. Data Brief 2025, 62, 111954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengbo, Z.; Renxiang, C.; Xiangyang, X.; Lixia, Y.; Mengyu, R. Recent progress and prospective evaluation of fault diagnosis strategies for electrified drive powertrains: A comprehensive review. Measurement 2023, 222, 113711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertargin, M.; Orhan, A.; Yildirim, O.; Gurgenc, T. Automated fault classification of asynchronous motor using mobile phone accelerometer Parallel Residual, CNN-GRU. Measurement 2025, 253, 117539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksek, G. Fault detection and classification in synchronous motors with a novel optimized CNN-GRU framework. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2026, 252, 112430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Zhao, T.; Wei, B.; Peng, B.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X. Mechanical fault diagnosis of on-load tap changers using time–frequency vibration analysis and a lightweight YOLO model. Measurement 2025, 256, 118441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Chen, X. A diagnosis method based on graph neural networks embedded with multirelationships of intrinsic mode functions for multiple mechanical faults. Def. Technol. 2025, 50, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukovskii, Y.L.; Suslikov, P.K. Identification and classification of electrical loads in mining enterprises based on signal decomposition methods. J. Min. Inst. 2025, 275, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, A.; Eller, R.; Peters, M. Creating competitiveness in incumbent small- and medium-sized enterprises: A revised perspective on digital transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 186, 115028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Zhang, Q. Leveraging the metaverse ecosystem: How institutional factors, adoption of metaverse-related technologies, and absorptive capacity drive performance in high-tech small and medium-sized enterprises. Inf. Manag. 2025, 62, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.Z.; Au, K.M.; Storey, V.C.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y. Shaping innovation pathways: Metaverse application configurations in high-technology small- and medium-sized enterprises. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 187, 114336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Leng, J.; Zhao, J.L.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, Y.; Lu, Y.; Mourtzis, D.; Qi, Q.; Huang, S.; Song, X.; et al. Industrial metaverse towards Industry 5.0: Connotation, architecture, enablers, and challenges. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 76, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Fridenfalk, M. Digital twins for building industrial metaverse. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 66, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gutiérrez, A.; Díez-González, J.; Perez, H.; Araújo, M. Towards industry 5.0 through metaverse. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 89, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, D.A.; Ivens, B.S. Conceptualizing the Industrial Metaverse: From Technological Layers to Business Value. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2025, 131, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xie, H.-L.; Zheng, P.; Wang, L. Industrial Metaverse: A proactive human-robot collaboration perspective. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 76, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanjung, T.; Ghazali, I.; Mahmood, W.H.W.; Herawan, S.G. Drivers and barriers to Industrial Revolution 5.0 readiness: A comprehensive review of key factors. Green Technol. Sustain. 2025, 3, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccarozzi, M.; Silvestri, C.; Fici, L.; Silvestri, L. Metaverse: A possible sustainability enabler in the transition from Industry 4.0 to 5.0. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 1839–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latino, M.E. A maturity model for assessing the implementation of Industry 5.0 in manufacturing SMEs: Learning from theory and practice. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 214, 124045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzis, D.; Wang, L. 3-Industry 50: Perspectives concepts technologies. In Manufacturing from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0; Mourtzis, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhlov, S.; Abiev, Z.; Makkoev, V. The Choice of Optical Flame Detectors for Automatic Explosion Containment Systems Based on the Results of Explosion Radiation Analysis of Methane- and Dust-Air Mixtures. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochneva, A.A.; Zaytseva, E.V.; Katuntsov, E.V. Reducing redundancy of laser scanning data for building digital terrain models. Model. Optim. Inf. Technol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romashev, A.O.; Nikolaeva, N.V.; Gatiatullin, B.L. Adaptive approach formation using machine vision technology to determine the parameters of enrichment products deposition. J. Min. Inst. 2022, 256, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykov, A.V.; Payor, V.A. Machine vision system for monitoring the process of levitation melting of non-ferrous metals. Tsvetnye Met. 2023, 4, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryabin, S.A.; Temkin, I.O. Ontological modeling and management of digital transformation of mining enterprises architecture. J. Min. Inst. 2025, 275, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Litvinenko, V.S. Digital Economy as a Factor in the Technological Development of the Mineral Sector. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, K.; Aromaa, S. Industrial metaverse–company perspectives. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergei, V. Khokhlov Application of digital simulation methods for predicting parameters of blasted rock muckpile. J. Min. Inst. 2025, 275, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.; Park, J.; Yoo, J.; Kim, S.; Park, H. A study on Gen-AI technology development trends to enhance small-medium sized enterprise digital competence and management quality. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2025, 17, 1193–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enamorado-Díaz, E.; García-García, J.A.; Escalona-Cuaresma, M.J.; Lizcano-Casas, D. Metaverse Applications: Challenges, Limitations and Opportunities-A Systematic Literature Review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2025, 182, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torayev, A.; Martínez-Arellano, G.; Chaplin, J.C.; Sanderson, D.; Ratchev, S. Towards Modular and Plug-and-Produce Manufacturing Apps. Procedia CIRP 2022, 107, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprov, P.; Starly, B. Industrial metaverse meets IIoT: Low-code platforms for machine-to-machine and human-to-machine integration. Manuf. Lett. 2025, 44, 1254–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.; Salim, S.S.; Anthony, B.W. Learning through development of a digital manufacturing system in a learning factory using low-code/no-code platforms. Manuf. Lett. 2025, 46, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, D.; Guimarães, T.; Abelha, A.; Santos, M.F. Low Code Approach for Business Analytics. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 231, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour Eldin, A.; Baudot, J.; Dalmas, B.; Gaaloul, W. Low-code solutions for business process dataflows: From modeling to execution. Inf. Syst. 2025, 135, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.; Moll, P.; Brocke, L.; Coutandin, S.; Fleischer, J. Model for Web-Application based Configuration of Modular Production Plants with automated PLC Line Control Code Generation. Procedia CIRP 2019, 83, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, J.; Núñez, F. Design of an IoT-PLC: A containerized programmable logical controller for the industry 4.0. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 25, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koteleva, N.; Korolev, N. A Diagnostic Curve for Online Fault Detection in AC Drives. Energies 2024, 17, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.G.; Staveland, L.E. Development of NASA-TLX(Task Load Index): Results of Empirical Theoretical Research. In Advances in Psychology; Hancock, P.A., Meshkati, N., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 139–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, E.; Dingler, T.; Tag, B.; Velloso, E. Should we use the NASA-TLX in HCI? A review of theoretical and methodological issues around Mental Workload Measurement. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2025, 201, 103515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Function Design | Function Name | Features of Application | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Engine | Engine technical data: P—power, kW; Uн—supply voltage, V; n—rated speed, rpm; p—number of pole pairs; J—moment of inertia, kg·m2 η—efficiency factor; cosφ—power factor; Km—overload capacity; Kp—starting torque multiple; Ki—starting current multiple. Equivalent circuit parameters: Ls—stator inductance, H; Lr—rotor inductance, H; Lm—mutual inductance, H; Rs—stator resistance, Ω; Rr—rotor resistance, Ω. | Represents user’s interaction with real engine; for correct operation, it is necessary to set technical parameters used for calculations and ensure operation of other connected functions |

| 2 |  | Real data/real data recorder | Reading real data from equipment/writing real data (user setting—the name of table to write to the database; if the value is default, the table name is assigned by the system). | Links real equipment and databases used in the system |

| 3 |  | Digital twin/engine model | Engine Technical data: P—power, kW; Uн—supply voltage, V; n—rated speed, rpm; p—number of pole pairs; J—moment of inertia, kg·m2 η—efficiency factor; cosφ—power factor; Km—overload capacity; Kp—starting torque multiple; Ki—starting current multiple. Equivalent circuit parameters: Ls—stator inductance, H; Lr—rotor inductance, H; Lm—mutual inductance, H; Rs—stator resistance, Ω; Rr—rotor resistance, Ω. | Provides interaction with the model used as a digital twin; allows user to configure digital twin and specify features and boundary conditions used in simulation |

| 4 |  | Synthetic data/synthetic data recorder | Reading/writing data generated by a digital model (digital twin) (user setting—the name of table to write to the database; if the value is default, the table name is assigned by the system). | Links synthesized objects and databases and separates real data from generated data |

| 5 |  | Broadcasting system output to wearable devices (augmented-reality glasses) | The user sets the device’s IP address, permissions, and settings related to the system’s information security. | Allows the user to customize interaction method and connection parameters with wearable devices |

| 6 |  | Visualization block | The user sets the types of visual data representations and the period (number of display points). Three modes can be enabled: graph mode, Park vector, and diagnostic curve. | Provides selection and setup methods for visualizing data from engine |

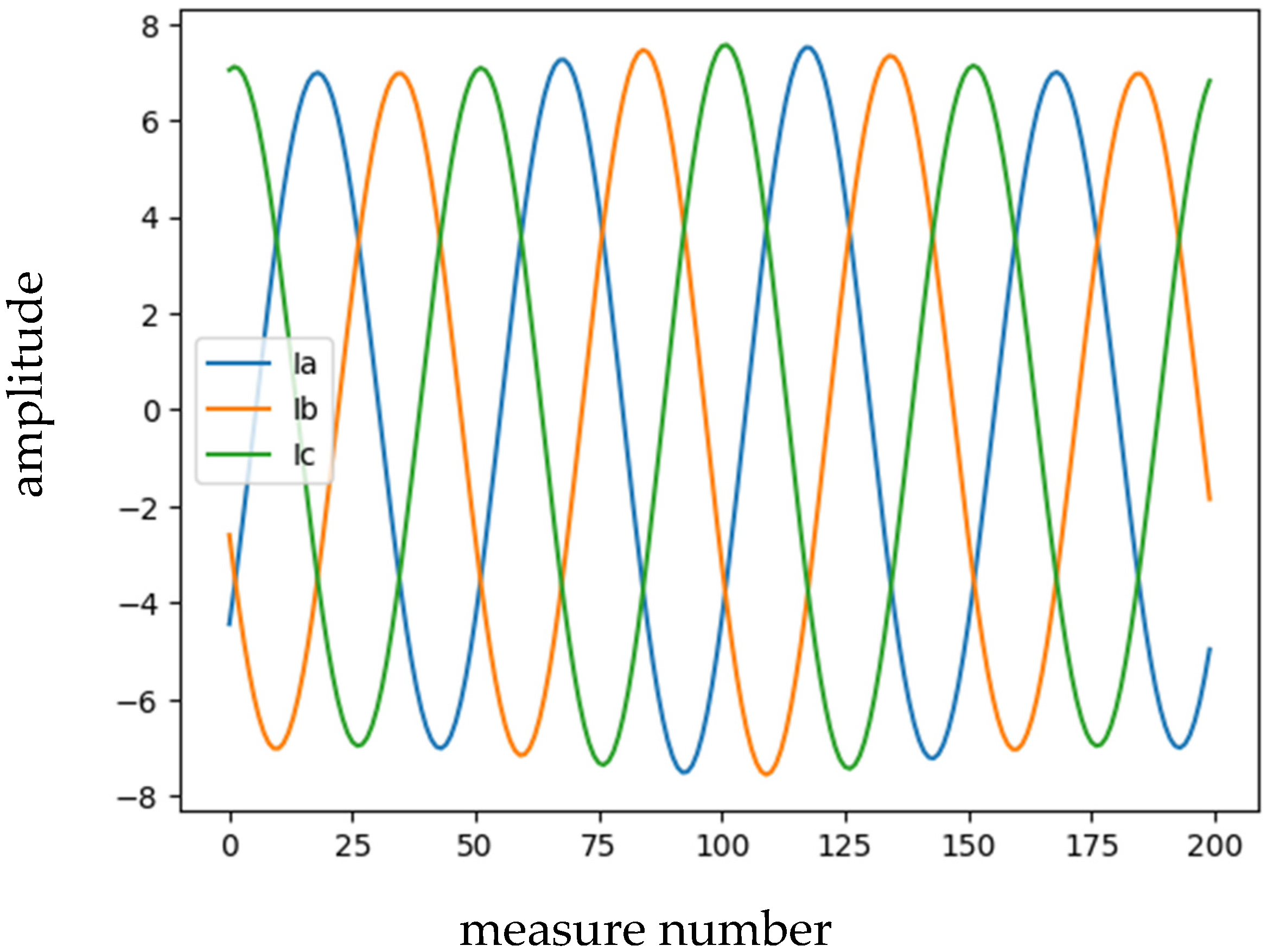

| 7 |  | Graph visualization | The user selects the phase for which data should be displayed. In reality, these are Ia, Ib, and Ic. | Allows user to configure graphical visualization |

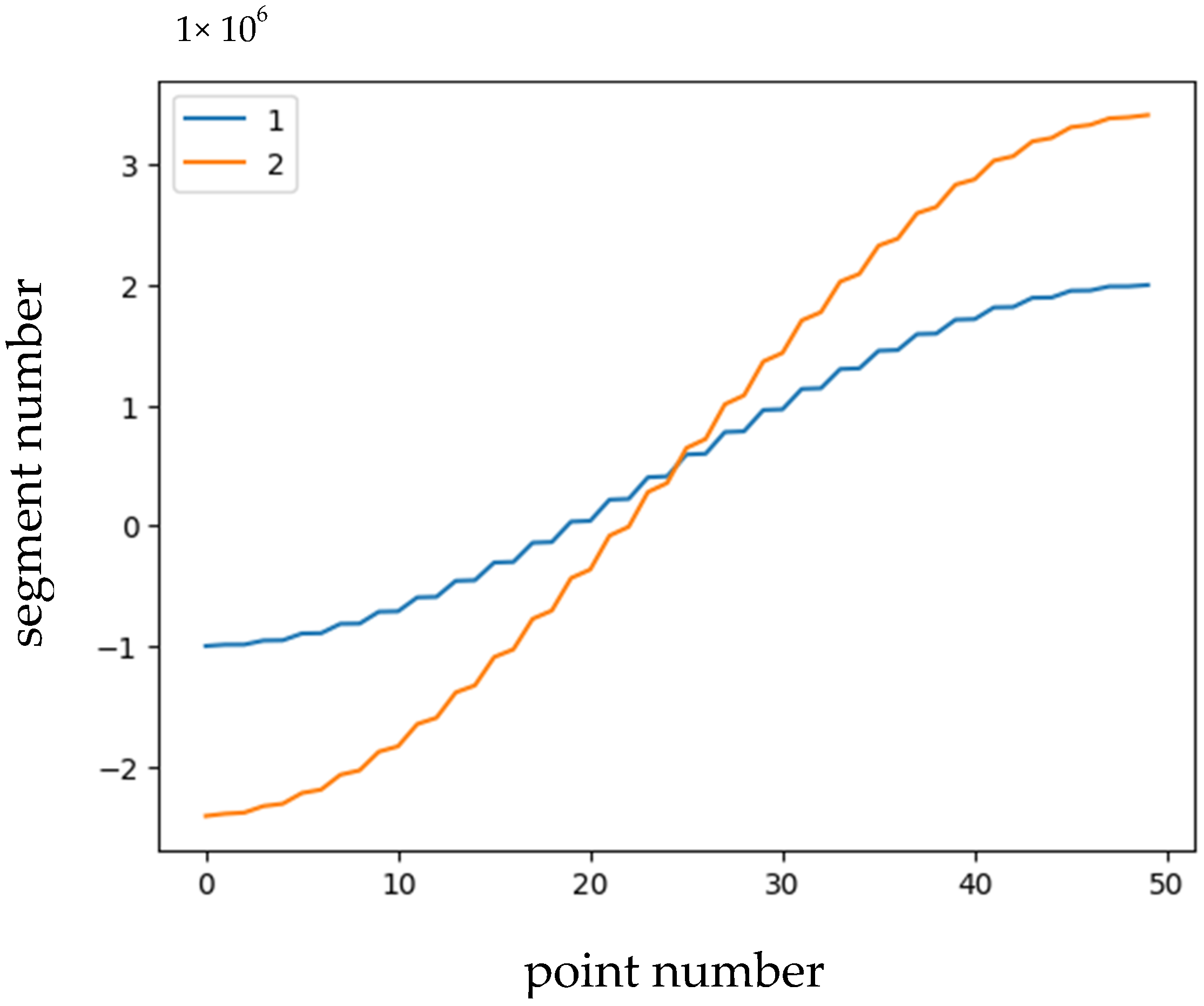

| 8 |  | Diagnostic curve visualization [49] | The user sets the frequency (number of points per period) and number of segments. | Allows user to configure the diagnostic curve |

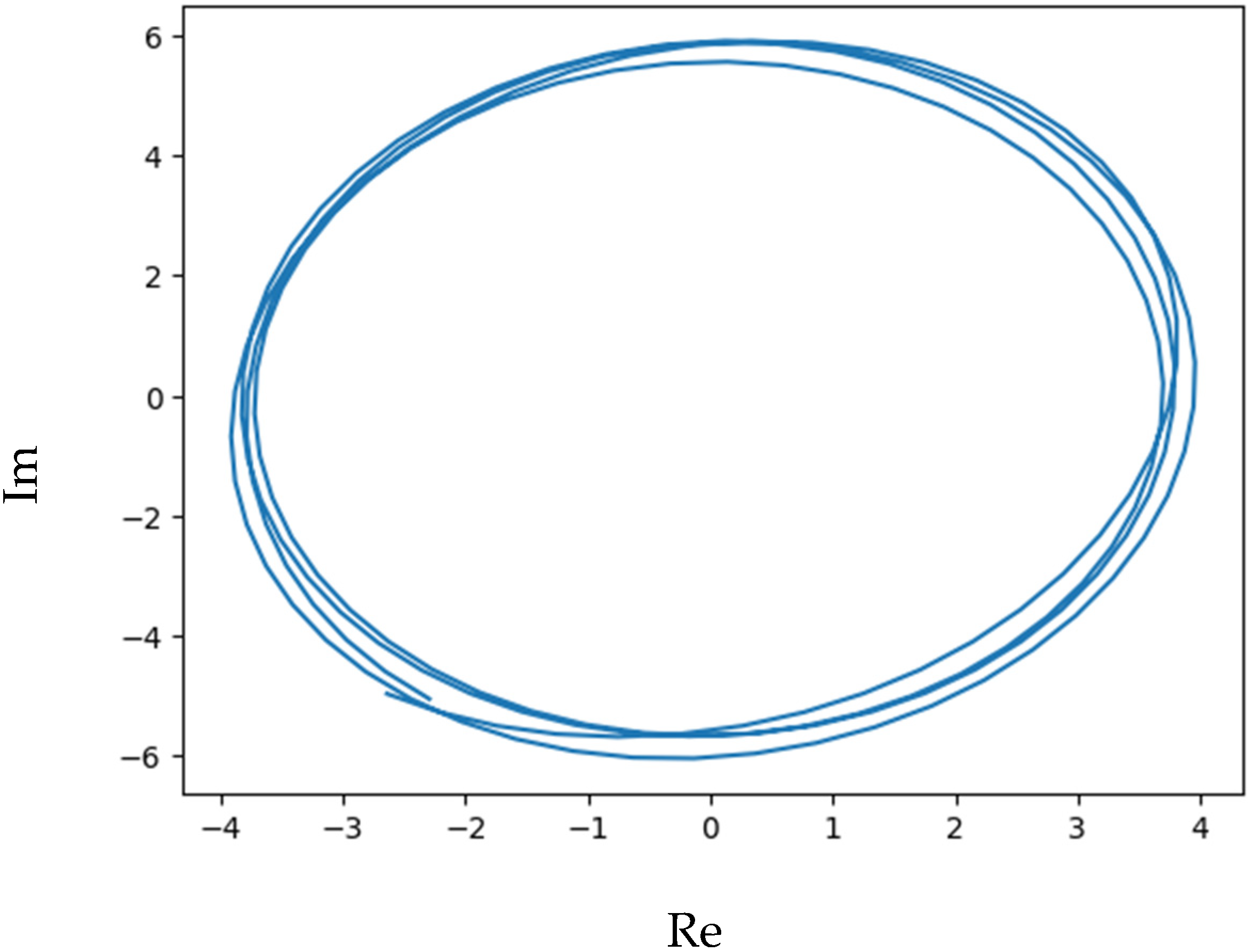

| 9 |  | Park vector visualization | The user sets the frequency (number of points per period). | Allows user to configure Park vector visualization |

| 10 |  | Type of defect simulated by the system | The user sets the type of defect. The configuration of defects depends on the capability of the digital model used as a digital twin. | Enables setup, configuration, and execution of specialized code simulating engine defect |

| 11 |  | Custom program code | The user sets their own code or uses template code. One of the templates is a data preprocessing code. | Allows user to create any custom code and execute it |

| 12 |  | Artificial intelligence block for training the model | The user selects artificial intelligence models and algorithms for training the model and the necessary parameters for training. | Allows user to setup, configure, and launch built-in artificial intelligence models or custom models |

| 13 |  | Class name input block for manual data labeling | The user sets the class name. | Enables user to enter class name values |

| 14 |  | Class name input block for auto data labeling | The user sets the templates for automatic class specification. | Provides ability to customize existing templates and create new templates |

| 15 |  | AI model training block | The user sets the learning target and key learning quality metrics. | Allows user to choose model training methods, various tuning coefficients, and also to add custom training algorithms |

| 16 |  | Block indicating that training process has been completed | This block is informational. The user does not configure it. | Provides visualization of AI model’s training goal achievement |

| 17 |  | Trained AI model connection block | The user sets the path to the saved AI model trained in advance. | Allows user to load pre-trained model |

| 18 |  | Electric motor diagnostic status output block | The user sets state–class data pairs | Provides visualization of current engine state or engine defect if one is detected |

| Class Number | Class Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | engine operation without defect under no load |

| 2 | engine operation without defect under 50% load |

| 3 | engine operation without defect under 100% load |

| 4 | engine operation under no load with misalignment defect |

| 5 | engine operation with misalignment defect under 50% load |

| 6 | engine operation with misalignment defect under 100% load |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koteleva, N.; Korolev, N.; Kovalchuk, M. Industrial Metaverse and Technical Diagnosis of Electric Drive Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312699

Koteleva N, Korolev N, Kovalchuk M. Industrial Metaverse and Technical Diagnosis of Electric Drive Systems. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312699

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoteleva, Natalia, Nikolay Korolev, and Margarita Kovalchuk. 2025. "Industrial Metaverse and Technical Diagnosis of Electric Drive Systems" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312699

APA StyleKoteleva, N., Korolev, N., & Kovalchuk, M. (2025). Industrial Metaverse and Technical Diagnosis of Electric Drive Systems. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12699. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312699