European Approach to Fire Safety in Rolling Stock

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Requirements for Flammability and Smoke Properties

- Smoke obscuring visibility and containing toxic components;

- High temperature.

- Failure of cooling devices in the brake chamber;

- Leakage current in the rear clutch system;

- Earth fault in the last car of the train;

- Electric motor defect;

- Short circuit in an external electrical wire;

- Contact broken by an external factor in the header assembly;

- Unintentional or deliberate arson;

- Ground fault in the cable between the fuse and the battery;

- Dap changer stuck in the transition position between the switched taps;

- Operation of the locomotive with low or no oil level in the tap changer or transformer;

- Heating of the smoothing reactor to high temperatures caused by a short circuit;

- Accidental or deliberate arson;

- Sabotage/terrorist attacks;

- Collisions and derailments where the fire is a secondary event, caused by, for example, ruptured diesel fuel tanks in railcars or short circuits in electrical systems.

- The total amount of hydrogen to be stored;

- The operational period (in the railway sector, the operational period of vehicles is significantly longer than in the automotive sector);

- Different pressure cycle characteristics compared to automotive applications;

- Different vibration characteristics and accident loads;

- Higher refueling frequency.

3. Fire Safety Requirements in the Area of Railway Interoperability

- Fire Prevention Measures

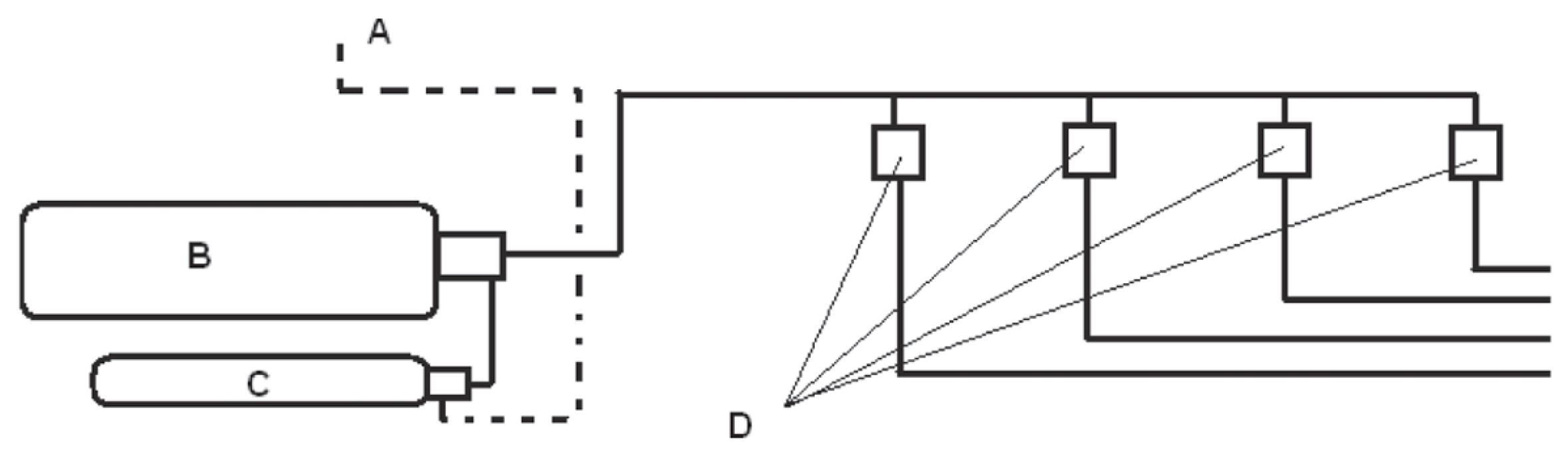

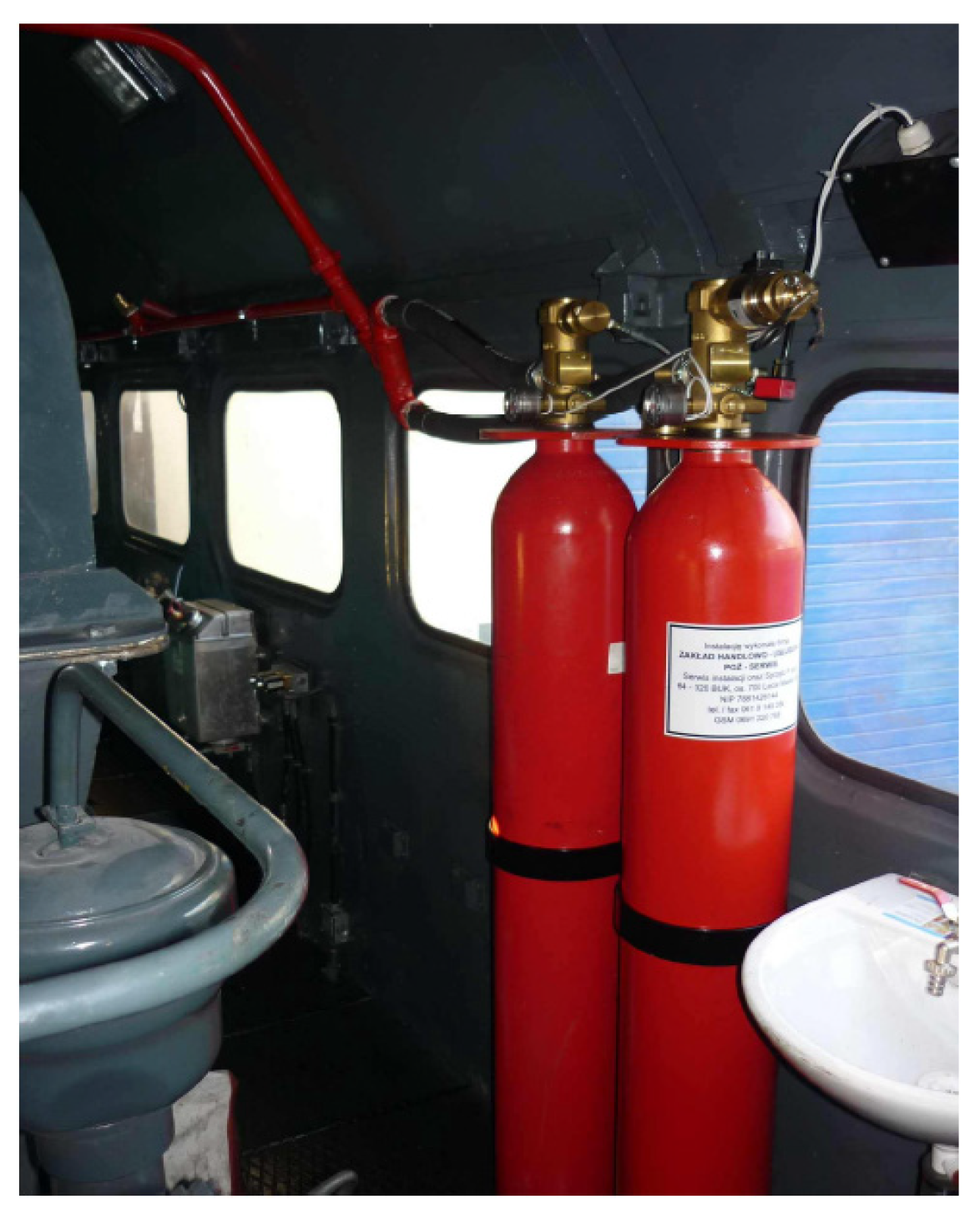

- Fire detection and extinguishing measuresThe next section of the LOC&PAS TSI [27] concerns requirements for the following:

- -

- Portable fire extinguishers;

- -

- Fire detection systems;

- -

- Automatic fire suppression systems for diesel-powered freight railway vehicles;

- -

- Fire control and containment systems for passenger rolling stock;

- -

- Fire prevention measures for freight locomotives and self-propelled freight railway vehicles.

- Emergency requirementsThis section covers requirements in the following areas:

- -

- Emergency lighting;

- -

- Smoke control;

- -

- Passenger alarm and communication;

- -

- Capability to navigate with a fire on board.

- Evacuation requirementsThis section specifies requirements for the following:

- -

- Passenger emergency exits;

- -

- Driver’s cab emergency exits.

- EN 45545 Part 1 [29]

- EN 45545 Part 2 [31]

- EN 45545 Part 3 [32]

- EN 45545 Part 4 [33]

- EN 45545 Part 5 [34]

- EN 45545 Part 6 [35]

- EN 45545 Part 7 [36]

- Complex electrical equipment that previously did not require fire safety testing according to national standards;

- Components requiring use due to the need to meet functional parameters (according to point 4.7 of the EN 45545-2 standard [31]);

- Applications of FCCS systems other than fire barriers;

- Alternative power supply systems.

4. Passive Safety Measures

- Samples for the requirement set R21-30 (upholstery of passenger seats);

- Samples for the requirement set R18-20 (complete passenger seats);

- Samples for the requirement set R1-40 (polyester–glass laminates);

- Samples for the requirement set R7-30 (paint coatings with filler).

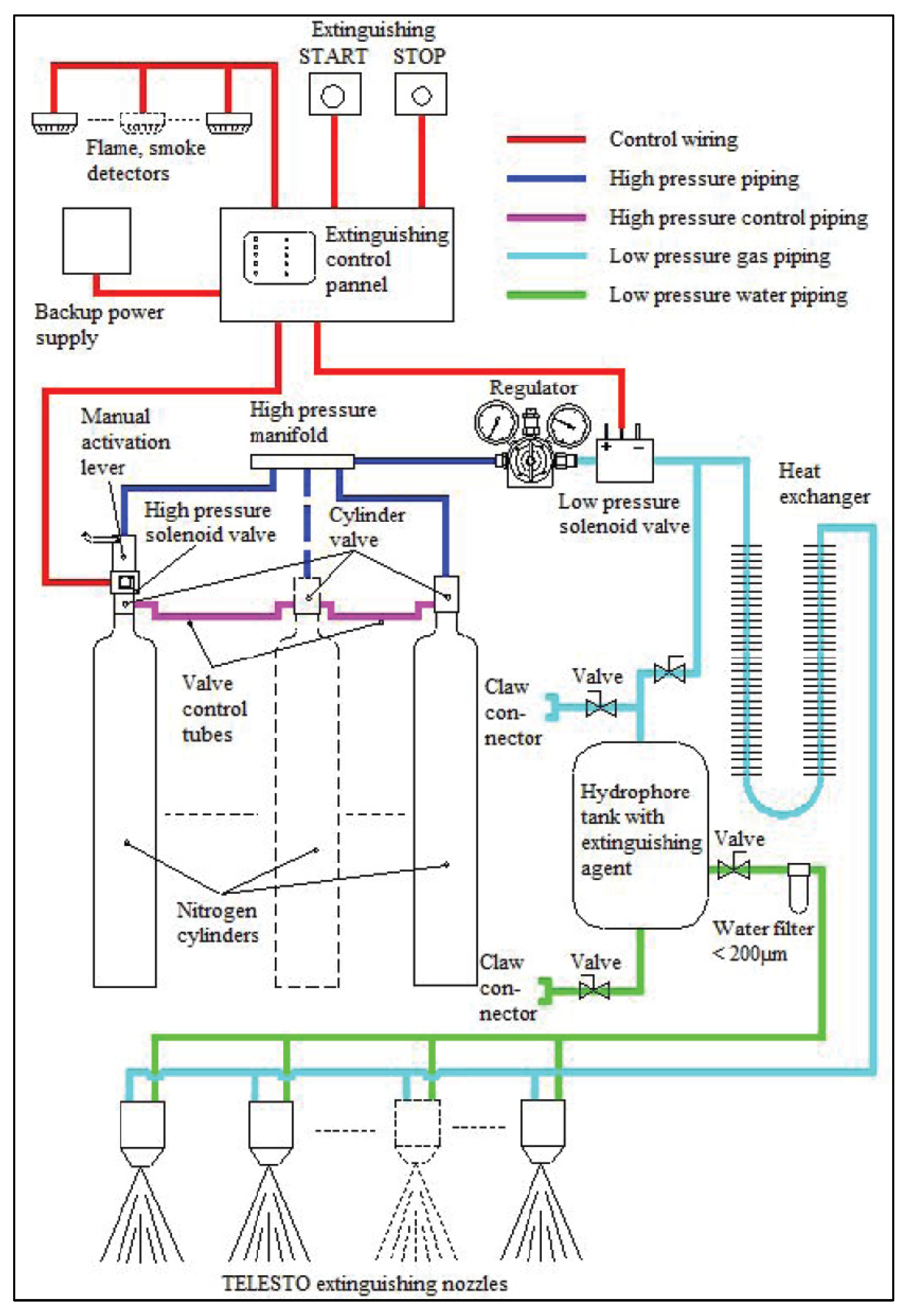

5. Active Safety Measures

6. The Use of Risk Assessment and RAMS Standards in Rail Transport in the Area of Fire Safety

- EN 50553:2012 [40] standard, which can be used for risk assessment both for investment purposes and for making strategic decisions during the operational phase;

- “(1) failure in the passenger alarm system leading to the impossibility for a passenger to initiate the activation of brake in order to stop the train when train departs from a platform”;

- “(2) failure in the passenger alarm system leading to no information given to the driver in case of activation of a passenger alarm”.

- Codes of practice;

- Reference systems;

- Explicit risk assessment, where explicit risk assessment can be carried out as a qualitative or quantitative assessment.

- Assessing the feasibility of operating transport services using rolling stock with a lower fire rating or without a defined fire rating using railway tunnels, or

- Assessing the need and scale of the need to adapt such rolling stock to these needs, or

- Assessing the need and scale of the need for potential retrofitting or reconstruction of tunnels.

7. Conformity Verification According to PN-EN 50553:2012

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guillaume, E.; Camillo, A.; Sainrat, A. Application of fire safety engineering to rolling stock. Probl. Kolejnictwa 2013, 160, 51–75. [Google Scholar]

- Radziszewska-Wolińska, J. Passenger train fire in a tunnel. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference Long Road and Rail Tunnels, Hong Kong, 9–11 May 2002; Tunnel Management International Ltd.: Kempston, UK, 2002; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Gierski, E. Problemy Działań Ratowniczo-Gaśniczych w Tunelach Kolejowych; Szkoła Aspirantów Państwowej Straży Pożarnej: Kraków, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hoj, N.P. Zagrożenia w tunelach. In Fire Protection and Safety Measures in Rail, Road and Metro Tunnels; FEiTR: Warszawa, Poland, 2006; pp. 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiński, A.; Gierski, E. Taktyka Działań Ratowniczo—Gaśniczych w Warszawskim Metrze; FIREX: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wenhui, J.; Zhongyuan, Y.; Yanping, Y. Pyrolysis, combustion, and fire spread characteristics of the railway train carriages: A review of development. Energy Built Environ. 2023, 4, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinmore, N. Train Fires: Understanding the Risks and Controlling Them. Available online: https://www.globalrailwayreview.com/article/122673/train-fires-risks-controlling/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Davis, J. How Do Trains Cause Wildfires? 2024. Available online: https://beta.cottagelife.com/outdoors/cottage-qa-how-do-trains-cause-wildfires/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Hubskyi, P.; Pawlik, M.; Kaźmierczak, A. Risk Assessment Regarding Use of Hydrogen in Railway Transport. In Proceedings of the 28th International Scientific Conference, Transport Means, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2–4 October 2024; Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1EPL8v_zIHysYNvW1w4tWAzt19HaMJlrW/view (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Dempsey, M. Houston Chronicle. Available online: https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Train-explosion-leads-to-chemical-release-in-11095738.php (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Radziszewska-Wolińska, J. Fire Hazard in Rail Vehicles with Alternative Power Sources. In Modren Trends in Fire Procection of Railway Rolling Stock; Instytut Kolejnictwa: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; pp. 130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, M. Battery Safety in Rail Transportation. Locomotives. 2025. Available online: https://www.railwayage.com/mechanical/locomotives/battery-safety-in-rail-transportation/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Eurostat. Railway Safety Statistics in the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Railway_safety_statistics_in_the_EU (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Railway Safety Statistics in the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20241030-1 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Global News. German High Speed Train Catches Fire. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/video/4541801/german-high-speed-train-catches-fire (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Rail Market News. Passenger Train Hits Truck in Wollsdorf, Austria, Four People Injured. Available online: https://railmarket.com/news/passenger-rail/33773-passenger-train-hits-truck-in-wollsdorf-austria-four-people-injured (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Rynek Kolejowy. The Burned-Out Koleje Mazowieckie Train Will Be Back on the Tracks (Original Title: Spalony Pociąg Kolei Mazowieckich Wróci na Tory). Available online: https://www.rynek-kolejowy.pl/wiadomosci/spalony-pociag-kolei-mazowieckich-wroci-na-tory-81342.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Obserwator Logistyczny. Railcar Fire near Warsaw! The Carriage Was Completely Destroyed! (Original Title: Pożar Szynobusu Nieopodal Warszawy! Wagon Całkowicie Spłonął!). Available online: https://obserwatorlogistyczny.pl/2024/01/16/pozar-szynobusu-nieopodal-warszawy-wagon-calkowicie-splonal/#google_vignette (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Eyewitnes News. Train Goes Up in Flames near Philadelphia. Available online: https://abc7.com/post/septa-train-fire-philadelphia-wilmington-ridley-park-delaware-county-350-passengers-evacuated/15874695/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Rail Tech. Berlin Passenger Train Bursts into Flames, Cause Unclear. Available online: https://www.railtech.com/all/2024/11/04/berlin-passenger-train-bursts-into-flames-cause-unclear/?gdpr=deny (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- PN-K-02500:1984; Tabor Kolejowy Pasażerski. Wymagania i badania materiałów pod względem ochrony przeciwpożarowej, Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Poland, 1984.

- DIN 5510-2:1991-04; Preventive Fire Protection in Railway Vehicles; Part 2: Fire Behaviour and Fire Side Effects of Materials and Parts, Classification, Requirement and Test Methods. Deutsches Institut für Normung: Berlin, Germany, 1991.

- NF F 16-101:1988; Rolling Stock. Fire Behaviour. Materials Choosing. Bureau de Normalisation des Chemins de Fer: Paris, France, 1988.

- NF F 16-102:1992; Railway Rolling Stock. Fire Behaviour. Materials Choosing, Application for Electric Equipment. Bureau de Normalisation des Chemins de Fer: Paris, France, 1992.

- UNI CEI 11170-1 1993; Railway and Tramway Vehicles—Guidelines for Fire Protection of Railway, Tramway and Guided Path Vehicles—General Principles. Instituto Italiano di Normazione: Roma, Italy, 1992.

- BS 6853:1999; Code of Practice for Fire Precautions in the Design and Construction of Passenger Carrying Train. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 1999.

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 1302/2014 of 18 November 2014 Concerning a Technical Specification for Interoperability Relating to the Rolling Stock—Locomotives and Passenger Rolling Stock Subsystem of the Rail System in the European Union—As Amended. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/1302/oj/eng (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 1303/2014 of 18 November 2014 Concerning the Technical Specification for Interoperability Relating to ‘Safety in Railway Tunnels’ of the Rail System of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/1303/oj/eng (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- EN 45545-1:2013; Railway Applications—Fire Protection on Railway Vehicles—Part 1: General. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- ISO/IEC 17025; Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- EN 45545-2:2013; Railway Applications—Fire Protection on Railway Vehicles—Part 2: Requirements for Fire Behaviour of Materials and Components. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- EN 45545-3:2024; Railway Applications—Fire Protection on Railway Vehicles. Fire Resistance Requirements for Fire Barriers. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- EN 45545-4:2024; Railway Applications—Fire Protection on Railway Vehicles. Fire Safety Requirements for Rolling Stock Design European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- EN 45545-5:2013; Railway Applications—Fire Protection on Railway Vehicles—Part 5: Fire Safety Requirements for Electrical Equipment Including That of Trolley Buses, Track Guided Buses and Magnetic Levitation Vehicles. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- EN 45545-6:2024; Railway Applications—Fire Protection on Railway Vehicles—Part 6: Fire Control and Management System. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- EN 45545-7:2013; Railway Applications—Fire Protection on Railway Vehicles—Part 7: Fire Safety Requirements for Flammable Liquid and Flammable Gas Installations. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- prTR FCCS:2019; Railway Applications—Fire Protection on Railway Vehicles—Assessment of Fire Containment and Control Systems for Railway Vehicles. Comité européen de normalization: Brussels. Belgium, 2019.

- TR 50718:2025; Technical Report—Guidelines for the Use of EN 45545-2 for Ni-Cd Batteries on Board Rolling Stock. European Committee for Elektrotechnical Standarization: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- TR 50750:2025; Technical Report—Report on the Use of EN 45545-2 and EN 45545-5 for Electronic Equipment. Comité Européen de Normalisation Électrotechnique: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- EN 50553:2012/A2:2020; Railway Applications—Requirements for Running Capability in Case of Fire on Board of Rolling Stock. European Committee for Elektrotechnical Standarization: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- ARGE Guideline—Part 2 “Fire Fighting in Railway Vehicles” Functional Assessment for the Efficiency of Fire Suppression and Extinguishing Systems in Passenger and Staff Areas, Electric Cabinets and in Areas with Combustion Engines. Available online: https://www.tuvsud.com/th-th/-/media/global/pdf-files/brochures-and-infosheets/rail/tuvsud-argeguidelinepart2firefightinginrailwayvehiclesv41.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Kaźmierczak, A. Role of Active Fire Protection Systems in Ensuring an Acceptable Level of Safety of Rolling Stock. Probl. Kolejnictwa 2021, 193, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargali, M. Rolling Stock and Fire Protection—An Overview of Aspects, Solutions and Requirements. Master’s Thesis, Mechanical Engineering, Sesto Fiorentino, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Directive (EU) 2016/797 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 on the Interoperability of the Rail System Within the European Union (Recast). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016L0797 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- PN-EN 50126-1:2018-02; Railway Applications—The Specification and Demonstration of Reliability, Availability, Maintainability and Safety (RAMS)—Part 1: Generic RAMS. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny:: Warszawa, Poland, 2018.

- PN-EN 50126-2:2018-02; Railway Applications—The Specification and Demonstration of Reliability, Availability, Maintainability and Safety (RAMS)—Part 2: Systems Approach to Safety. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Poland, 2018.

- PN-EN 50128:2011; Railway Applications. Communication, Signalling and Processing Systems. Software for Railway Control and Protection Systems. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Poland, 2011.

- PN-EN 50129:2019-01; Railway Applications—Communication, Signalling and Processing Systems—Safety Related Electronic Systems for Signalling. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Poland, 2011.

- PN-EN 50159:2011; Railway Applications—Communication, Signalling and Processing Systems—Safety-Related Communication in Transmission Systems. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 402/2013 of 30 April 2013 on the Common Safety Method for Risk Evaluation and Assessment and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 352/2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R0402 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Pawlik, M.; Radziszewska-Wolińska, J. Risk Assesment in Rail Vehicle Fire Safety—Legal and Standardisation Requirements. In Modern Trends in Fire Procection of Railway Rolling Stock; Instytut Kolejnictwa: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; pp. 40–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Shu, Y.; Qi, X.; Jiang, C. Simulation of fire emergency evacuation in a large-passenger-flow subway station based on the on-site measured data of Shenzhen Metro. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2024, 6, tdad006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, A. The Planning, Conduct and Evaluation of Emergency Exercises in Rail Transport. In Modern Trends in Fire Procection of Railway Rolling Stock; Instytut Kolejnictwa: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; pp. 101–115. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radziszewska-Wolińska, J.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Milczarek, D. European Approach to Fire Safety in Rolling Stock. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12671. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312671

Radziszewska-Wolińska J, Kaźmierczak A, Milczarek D. European Approach to Fire Safety in Rolling Stock. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12671. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312671

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadziszewska-Wolińska, Jolanta, Adrian Kaźmierczak, and Danuta Milczarek. 2025. "European Approach to Fire Safety in Rolling Stock" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12671. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312671

APA StyleRadziszewska-Wolińska, J., Kaźmierczak, A., & Milczarek, D. (2025). European Approach to Fire Safety in Rolling Stock. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12671. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312671