Effectively Obtaining Acoustic, Visual, and Textual Data from Videos

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. State of the Art

- A

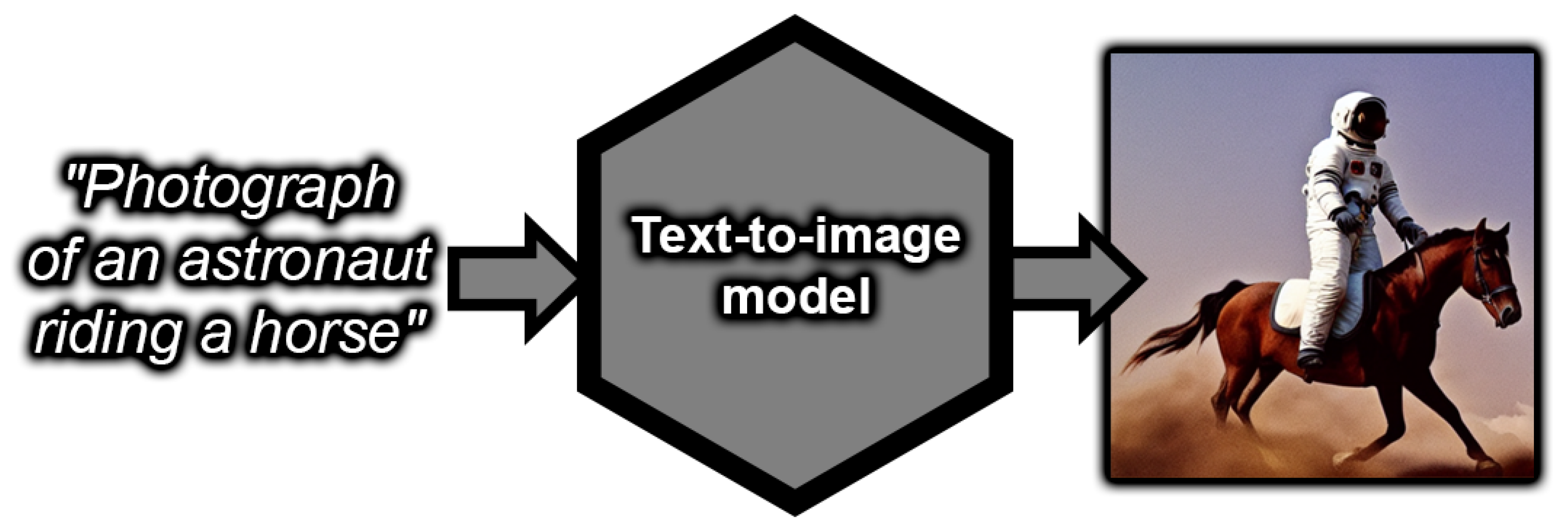

- Word limit in current models: currently, the problem of increasing the token window (i.e., words and characters) of text-to-image and audio-to-text models is open. For example, Stable Diffusion (an open-source neural network model that generates images based on text and/or image [19]) has a context window of 75 tokens [91].

- B

- Compatibility between text–image and audio–text models: Even if a capacity of hundreds of thousands of tokens is reached to describe any audio (as can be seen analogously in certain current text generation models [92,93,94,95]), the syntax of the text obtained with such an audio–text model must match that used by the respective text–image model with which it is to be combined in order to maximize communication between the two [19,76,90,96].

- C

- Noise incorporation (see [97] for a brief classical exploration of the definition of the term): In addition to the above, it has repeatedly been shown that transforming one modality to another is prone to incorporating noise or failing (to some extent) due to the noise that the data contain beforehand [47,98,99,100]. As a result, the more transformations we make, the more noise we risk adding in the process.

- D

- Incorporation of biases: Finally, it is pertinent to highlight that, influenced both by the data and their training architectures and configurations, models tend to prioritize and specialize in certain types of audio and have their own preferences for describing them [101,102,103,104]. For example, typical cases of this can be seen in the underestimation/distortion of the order of events [90,96] or in the omission of details considered irrelevant [96,105].

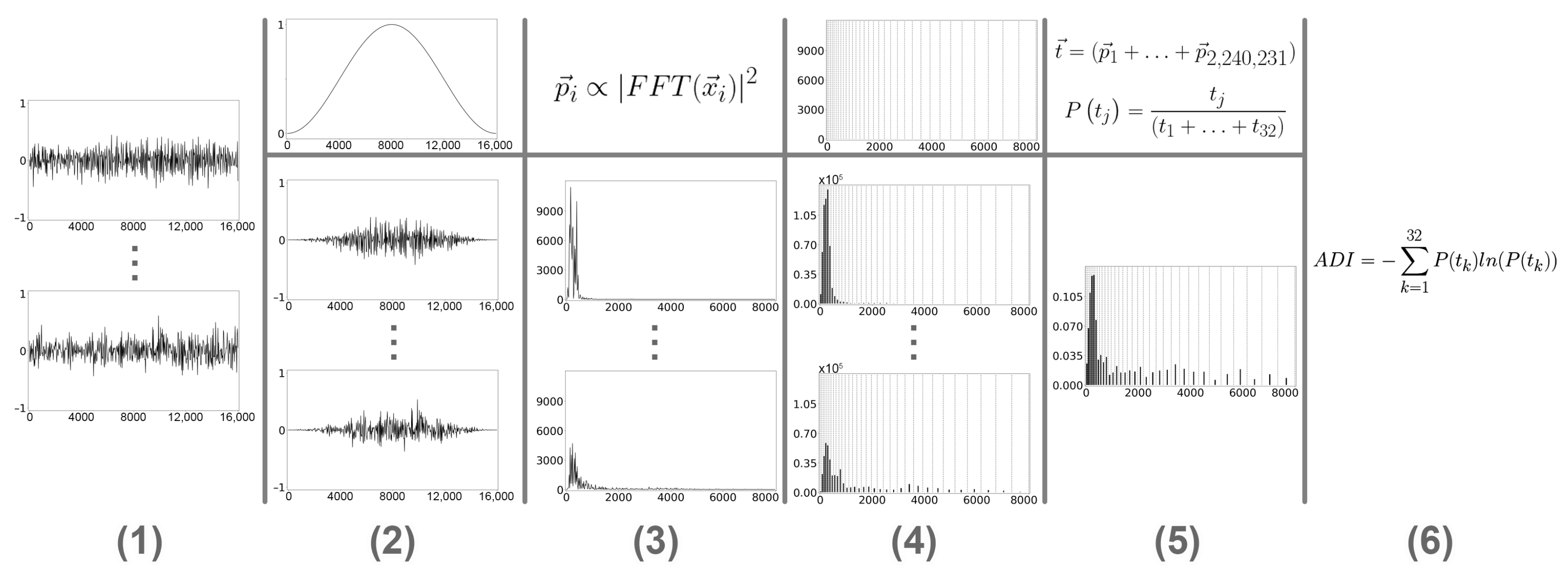

4. Materials and Methods

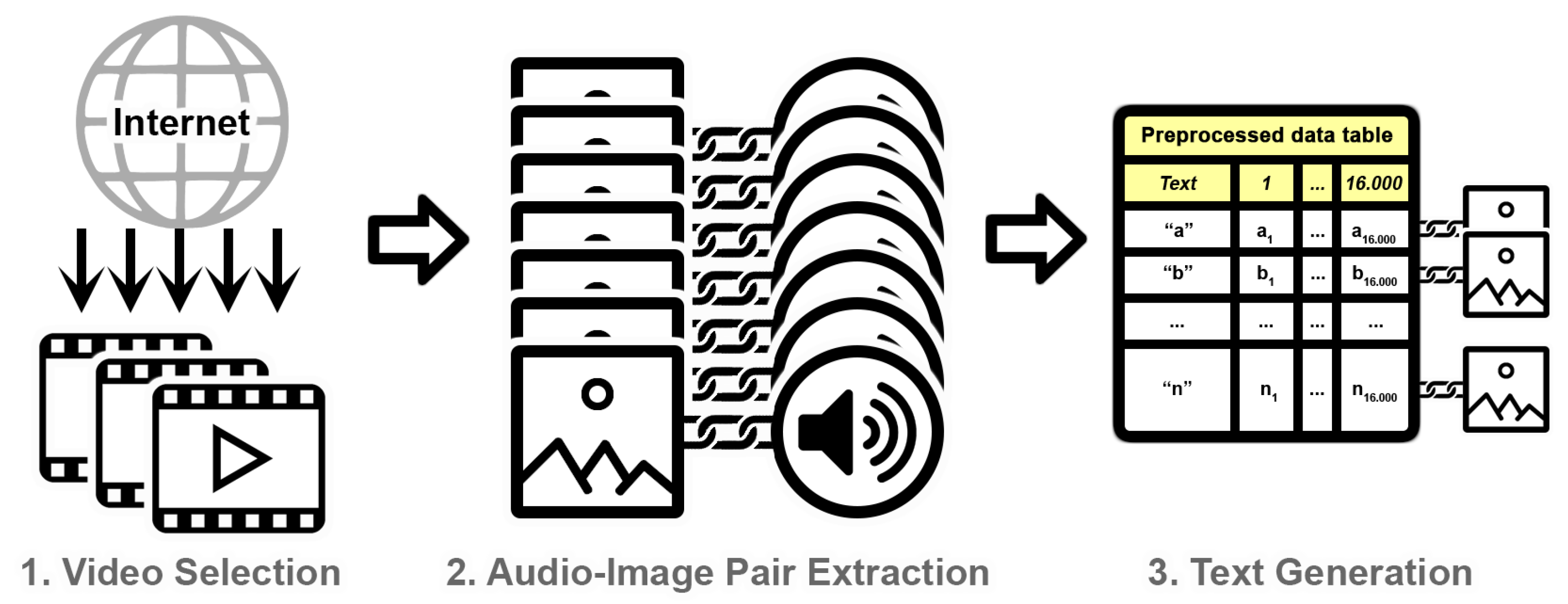

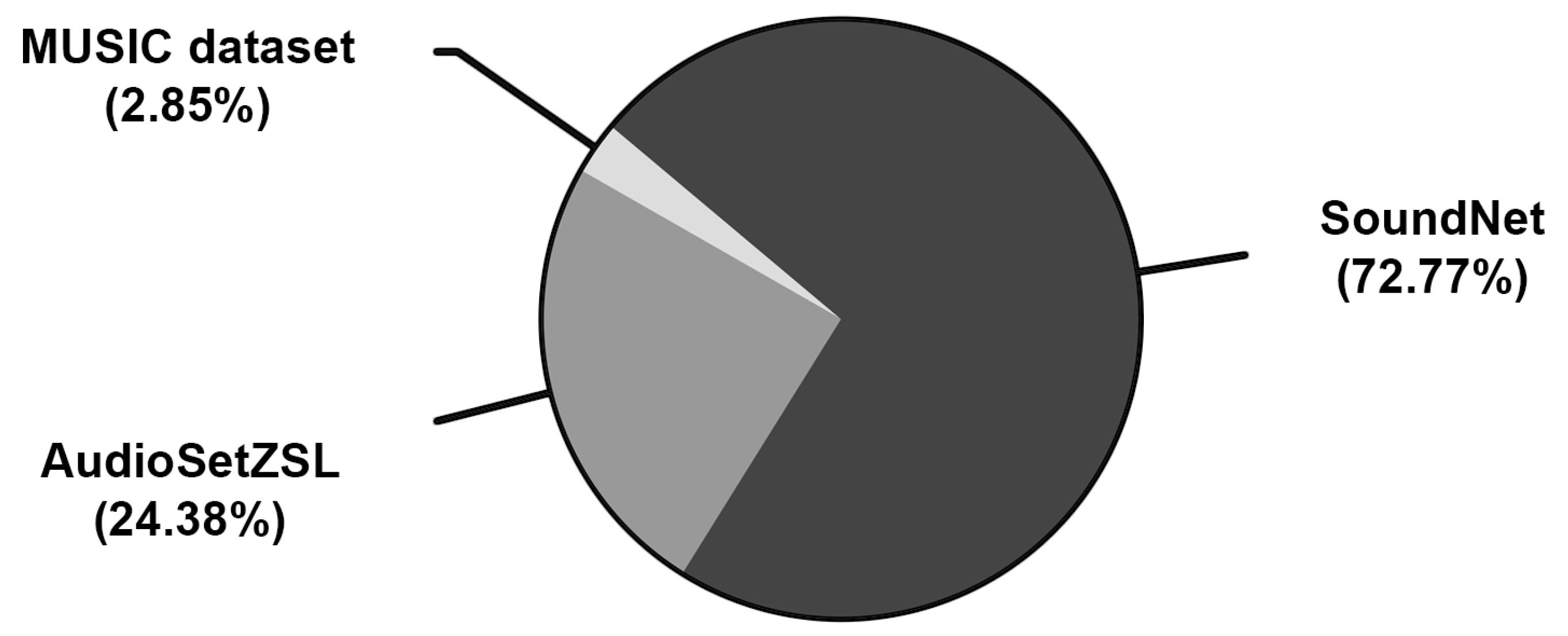

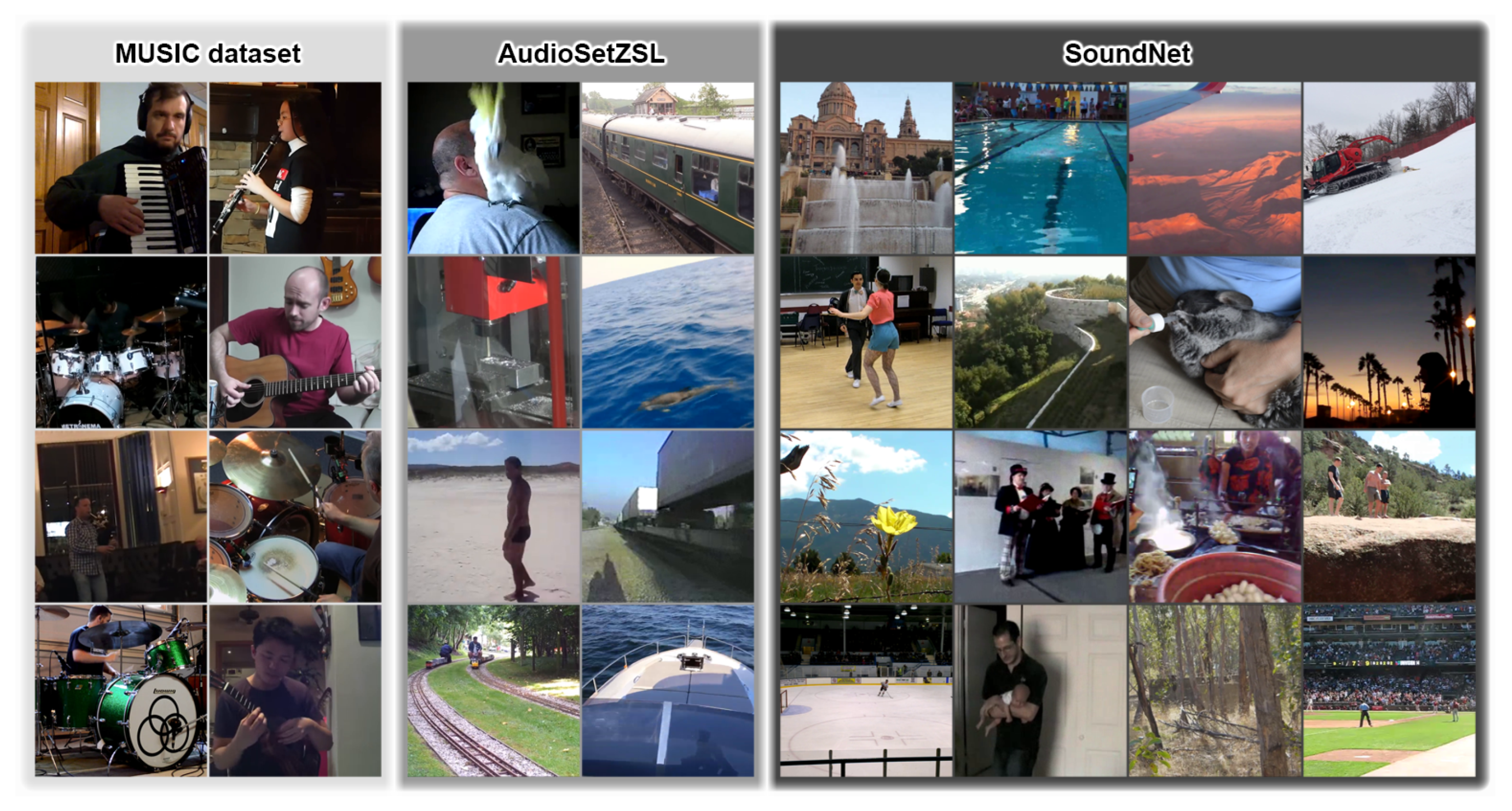

4.1. Video Selection

4.2. Audio–Image Pair Extraction

- Inspect each video, evaluating if it has black borders. If so, these must be cropped to only consider relevant information in the final images. This can be accomplished by taking a frame in the middle and verifying if each first and last column/row does not have a pixel with value higher than a certain threshold in any of its channels (we use a threshold of 15 for this). In that situation, that column/row should be deleted, and the step is repeated until all of the black borders have been erased (similar to what is done in [116]).

- To ensure that no drastic/unnatural changes are present in any audio, go through each video frame by frame. If an abrupt change is detected (for example, if the average of the squared differences of pixels between two consecutive frames is greater than a threshold of 90), then proceed to divide the footage into two and, for all purposes, treat them as distinct videos going forward. This is known as shot boundary detection [117], particularly of the pixel-based approach kind (there is no well-extended threshold for this, so it is up to the architect of the respective dataset to find an appropriate value; we empirically found that the aforementioned 90 for the average of the squared differences of pixels between two consecutive frames works for our interests, but it may be different in other cases). It should be remarked that the videos with fade transitions could present some problem with this approach and, to compensate it, more future frames could be used in the comparison.

- For each resulting video fragment, extract consecutive audios of one second, along with the frame that is approximately in the middle of that time interval to form the respective pairs. Please note that this is known as middle frame extraction, and it is a well-extended heuristic to select a representative frame of a video fragment, which should have better odds to properly match semantically with the respective audio [118,119,120,121]. If the final part does not reach one second, it must be ignored.

- Discard pairs whose audio has at least a given amount of continuous silence, as they will probably not contain enough information to be useful (we looked for continuous intervals of 0.5 s where none of their samples had an absolute value higher than 100) (keep in mind that we are considering samples of 16 bits, implying that the values they take go from −32,768 up to 32,767; once again, there is no well-extended threshold for this task, and the value we chose was found empirically). This, in turn, can be combined with a discount of pairs where the mean of all pixels in the image does not surpass a given threshold (we suggest a threshold of 10). The latter should further ensure that no frames that are too dark are included.

- To increase diversity in the data (and thus not skew the research), also consider skipping a given number of pairs from each video fragment (we just kept one pair from every three).

- To preserve the dimensions, crop each frame according to the smaller dimension and around the center of the image, and rescale to 512 × 512 pixels. In addition, make sure to use the correct configuration for both saved files.

4.3. Text Generation

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mukhamediev, R.I.; Symagulov, A.; Kuchin, Y.; Yakunin, K.; Yelis, M. From Classical Machine Learning to Deep Neural Networks: A Simplified Scientometric Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Kweon, I.S. Text-to-image Diffusion Models in Generative AI: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.07909. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschelli, G.; Musolesi, M. Creativity and Machine Learning: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2104.02726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, S.; Guo, J.; Liu, J.J.; Tripathi, S.; Kurup, U.; Shah, M. A Survey of On-Device Machine Learning: An Algorithms and Learning Theory Perspective. ACM Trans. Internet Things 2021, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models from Natural Language Supervision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. BLIP: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training for Unified Vision-Language Understanding and Generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.12086. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.12597. [Google Scholar]

- Podell, D.; English, Z.; Lacey, K.; Blattmann, A.; Dockhorn, T.; Müller, J.; Penna, J.; Rombach, R. SDXL: Improving Latent Diffusion Models for High-Resolution Image Synthesis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.01952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imagen-Team-Google; Baldridge, J.; Bauer, J.; Bhutani, M.; Brichtova, N.; Bunner, A.; Castrejon, L.; Chan, K.; Chen, Y.; Dieleman, S.; et al. Imagen 3. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.07009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labs, B.F. FLUX. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/black-forest-labs/flux (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Bertalmío, M.; Sapiro, G.; Caselles, V.; Ballester, C. Image inpainting. In Proceedings of the 27th Internationl Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–28 July 2000; pp. 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Aggarwal, N.; Jain, U.; Jaiswal, H. Outpainting Images and Videos using GANs. Int. J. Comput. Trends Technol. 2020, 68, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Lin, J.; Qin, T.; Chen, Z. Image-to-Image Translation: Methods and Applications. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 24, 3859–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Teli, M.N. Comparison and Analysis of Image-to-Image Generative Adversarial Networks: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2112.12625. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann, C.; Beaumont, R.; Vencu, R.; Gordon, C.; Wightman, R.; Cherti, M.; Coombes, T.; Katta, A.; Mullis, C.; Wortsman, M.; et al. LAION-5B: An open large-scale dataset for training next generation image-text models. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, online, 6–14 December 2022; pp. 25278–25294. [Google Scholar]

- Changpinyo, S.; Sharma, P.K.; Ding, N.; Soricut, R. Conceptual 12M: Pushing Web-Scale Image-Text Pre-Training To Recognize Long-Tail Visual Concepts. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 3557–3567. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Luo, P.; Qiu, S.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. DeepFashion: Powering Robust Clothes Recognition and Retrieval with Rich Annotations. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1096–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2112.10752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, P.; Kulal, S.; Blattmann, A.; Entezari, R.; Müller, J.; Saini, H.; Levi, Y.; Lorenz, D.; Sauer, A.; Boesel, F.; et al. Scaling Rectified Flow Transformers for High-Resolution Image Synthesis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.03206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. Stable Diffusion. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/CompVis/stable-diffusion (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Ramesh, A.; Pavlov, M.; Goh, G.; Gray, S.; Voss, C.; Radford, A.; Chen, M.; Sutskever, I. Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.12092. [Google Scholar]

- Betker, J.; Goh, G.; Jing, L.; Brooks, T.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Ouyang, L.; Zhuang, J.; Lee, J.; Guo, Y.; et al. Improving Image Generation with Better Captions. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/papers/dall-e-3.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- OpenAI. DALL·E 3 System Card. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/papers/DALL_E_3_System_Card.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Saharia, C.; Chan, W.; Saxena, S.; Li, L.; Whang, J.; Denton, E.; Ghasemipour, S.K.S.; Ayan, B.K.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Gontijo-Lopes, R.; et al. Photorealistic Text-to-Image Diffusion Models with Deep Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2024; pp. 36479–36494. [Google Scholar]

- Birhane, A.; Prabhu, V. Large image datasets: A pyrrhic win for computer vision? In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021; pp. 1536–1546. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijngaard, G.; Formisano, E.; Esposito, M.; Dumontier, M. Audio-Language Datasets of Scenes and Events: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.06947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żelaszczyk, M.; Mańdziuk, J. Audio-to-Image Cross-Modal Generation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.13354. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Khademi, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Bansal, M. CoDi-2: In-Context, Interleaved, and Interactive Any-to-Any Generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.18775. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M.; Bansal, M. Any-to-any generation via composable diffusion. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; pp. 16083–16099. [Google Scholar]

- Lab, S.A. BindDiffusion: One Diffusion Model to Bind Them All. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/sail-sg/BindDiffusion (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Zheng, Z.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X.; Lu, X. Remote Sensing Image Generation From Audio. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, Z.; Watson, G.; Janeja, V.P. Audio deepfakes: A survey. Front. Big Data 2023, 5, 1001063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Luo, M.D.; Wang, R.; Zheng, A.H.; He, R. Deep Audio-visual Learning: A Survey. Int. J. Autom. Comput. 2021, 18, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z. A Survey on Audio Synthesis and Audio-Visual Multimodal Processing. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.00443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffer, R.; Adi, Y. I Hear Your True Colors: Image Guided Audio Generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2211.03089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; et al. Neural Codec Language Models are Zero-Shot Text to Speech Synthesizers. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.02111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, K.-w.; Chung, H.L.; Liu, A.H.; Li, H.-y. Towards audio language modeling—An overview. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13236. [Google Scholar]

- Melechovsky, J.; Guo, Z.; Ghosal, D.; Majumder, N.; Herremans, D.; Poria, S. Mustango: Toward Controllable Text-to-Music Generation. In Proceedings of the 2024 North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Mexico City, Mexico, 16–21 June 2024; pp. 8293–8316. [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal, P.; Jun, H.; Payne, C.; Kim, J.W.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I. Jukebox: A Generative Model for Music. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.00341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, R.; Badlani, R.; Kong, Z.; Lee, S.-g.; Goel, A.; Kim, S.; Santos, J.F.; Dai, S.; Gururani, S.; AIJa’fari, A.; et al. Fugatto 1—Foundational Generative Audio Transformer Opus 1. 2024. Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=B2Fqu7Y2cd (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Kreuk, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Polyak, A.; Singer, U.; Défossez, A.; Copet, J.; Parikh, D.; Taigman, Y.; Adi, Y. AudioGen: Textually Guided Audio Generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2209.15352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Mei, X.; Liu, X.; Mandic, D.; Wang, W.; Plumbley, M.D. AudioLDM: Text-to-Audio Generation with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 21450–21474. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, F.; Yu, Y.; Wu, R.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S.; Liu, L.; Kortylewski, A.; Theobalt, C.; Xing, E. Multimodal Image Synthesis and Editing: The Generative AI Era. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2112.13592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhu, X.; Clifton, D.A. Multimodal Learning with Transformers: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 12113–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Gupta, R.; Singh, U.; Shaikh, F. Transcripter-Generation of the transcript from audio to text using Deep Learning. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 28492–28518. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Shi, D.; Plumbley, M.; Gan, W.S.; Chen, J. AudioSetCaps: An Enriched Audio-Caption Dataset using Automated Generation Pipeline with Large Audio and Language Models. In Proceedings of the Audio Imagination: NeurIPS 2024 Workshop AI-Driven Speech, Music, and Sound Generation, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzendörfer, L.A.; Pinkl, C.; Perraudin, N.; Wattenhofer, R. BLAP: Bootstrapping Language-Audio Pre-training for Music Captioning. In Proceedings of the Audio Imagination: NeurIPS 2024 Workshop AI-Driven Speech, Music, and Sound Generation, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, P.; Xie, Z.; Wu, M.; Zhu, K.Q. BLAT: Bootstrapping Language-Audio Pre-training based on AudioSet Tag-guided Synthetic Data. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 2756–2764. [Google Scholar]

- Yariv, G.; Gat, I.; Wolf, L.; Adi, Y.; Schwartz, I. AudioToken: Adaptation of Text-Conditioned Diffusion Models for Audio-to-Image Generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.13050. [Google Scholar]

- Jonason, N.; Sturm, B.L.T. TimbreCLIP: Connecting Timbre to Text and Images. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.11225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Yan, Z.; Gao, C.; Chen, R.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.; Gao, J.; et al. Sora: A Review on Background, Technology, Limitations, and Opportunities of Large Vision Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.17177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Video Generation Models as World Simulators. 2024. Available online: https://openai.com/index/video-generation-models-as-world-simulators/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- DeepMind, G. Veo. 2024. Available online: https://deepmind.google/technologies/veo/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Runway. Introducing Gen-3 Alpha: A New Frontier for Video Generation. 2024. Available online: https://runwayml.com/research/introducing-gen-3-alpha (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- The Movie Gen Team. Movie Gen: A Cast of Media Foundation Models. 2024. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/static-resource/movie-gen-research-paper (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Cao, H.; Tan, C.; Gao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chen, G.; Heng, P.A.; Li, S.Z. A Survey on Generative Diffusion Models. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 2814–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Matsuo, Y. A survey of multimodal deep generative models. Adv. Robot. 2022, 36, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Fei, H.; Qu, L.; Ji, W.; Chua, T.S. NExT-GPT: Any-to-Any Multimodal LLM. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2309.05519. [Google Scholar]

- Girdhar, R.; El-Nouby, A.; Liu, Z.; Singh, M.; Alwala, K.V.; Joulin, A.; Misra, I. ImageBind: One Embedding Space To Bind Them All. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.05665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmann, C.; Vencu, R.; Beaumont, R.; Kaczmarczyk, R.; Mullis, C.; Katta, A.; Coombes, T.; Jitsev, J.; Komatsuzaki, A. LAION-400M: Open Dataset of CLIP-Filtered 400 Million Image-Text Pairs. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.02114. [Google Scholar]

- Gemmeke, J.F.; Ellis, D.P.W.; Freedman, D.; Jansen, A.; Lawrence, W.; Moore, R.C.; Plakal, M.; Ritter, M. Audio Set: An ontology and human-labeled dataset for audio events. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–9 March 2017; pp. 776–780. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.D.; Kim, B.; Lee, H.; Kim, G. AudioCaps: Generating Captions for Audios in The Wild. In Proceedings of the 2019 North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, New Minneapolis, MN, USA, 3–5 June 2019; pp. 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Aytar, Y.; Vondrick, C.; Torralba, A. SoundNet: Learning Sound Representations from Unlabeled Video. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Changsha, China, 20–23 November 2016; pp. 892–900. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, M.; Nagrani, A.; Varol, G.; Zisserman, A. Frozen in Time: A Joint Video and Image Encoder for End-to-End Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 1708–1718. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H.; Hang, T.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, H.; Fu, J.; Guo, B. Advancing High-Resolution Video-Language Representation with Large-Scale Video Transcriptions. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5026–5035. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Lichtenberg, S.P.; Xiao, J. SUN RGB-D: A RGB-D scene understanding benchmark suite. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 567–576. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, M.; Tang, W.; Zhou, W. LLVIP: A Visible-infrared Paired Dataset for Low-light Vision. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3489–3497. [Google Scholar]

- Grauman, K.; Westbury, A.; Byrne, E.; Cartillier, V.; Chavis, Z.; Furnari, A.; Girdhar, R.; Hamburger, J.; Jiang, H.; Kukreja, D.; et al. Ego4D: Around the World in 3,000 Hours of Egocentric Video. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Ghanem, A.; Zhang, M.; Yao, Z.; Wu, X.; Holmes, C.; Golnari, P.; Clifton, D.A.; et al. RenAIssance: A Survey into AI Text-to-Image Generation in the Era of Large Model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.00810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Biderman, S.; Black, S.; Golding, L.; Hoppe, T.; Foster, C.; Phang, J.; He, H.; Thite, A.; Nabeshima, N.; et al. The Pile: An 800GB Dataset of Diverse Text for Language Modeling. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2101.00027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elasri, M.; Elharrouss, O.; Al-Maadeed, S.; Tairi, H. Image Generation: A Review. Neural Process. Lett. 2022, 54, 4609–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.; Savinov, N.; Teplyashin, D.; Lepikhin, D.; Lillicrap, T.; baptiste Alayrac, J.; Soricut, R.; Lazaridou, A.; Firat, O.; Schrittwieser, J.; et al. Gemini 1.5: Unlocking multimodal understanding across millions of tokens of context. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.05530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Lin, K.; Wang, J.; Lin, C.C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L. The Dawn of LMMs: Preliminary Explorations with GPT-4V(ision). arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.17421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, A.; Denk, T.I.; Borsos, Z.; Engel, J.; Verzetti, M.; Caillon, A.; Huang, Q.; Jansen, A.; Roberts, A.; Tagliasacchi, M.; et al. MusicLM: Generating Music From Text. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.11325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Park, S.; Ro, Y. Intuitive Multilingual Audio-Visual Speech Recognition with a Single-Trained Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 4886–4890. [Google Scholar]

- Trigka, M.; Dritsas, E. A Comprehensive Survey of Deep Learning Approaches in Image Processing. Sensors 2025, 25, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, R.K.; Pandey, R.; Pattnaik, R. Deep Learning For Computer Vision Tasks: A review. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Oerlemans, A.; Lao, S.; Wu, S.; Lew, M.S. Deep learning for visual understanding: A review. Neurocomputing 2016, 187, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulodimos, A.; Doulamis, N.; Doulamis, A.; Protopapadakis, E. Deep Learning for Computer Vision: A Brief Review. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2018, 2018, 7068349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otter, D.W.; Medina, J.R.; Kalita, J.K. A Survey of the Usages of Deep Learning for Natural Language Processing. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 604–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, D.Z. More Than Reading Comprehension: A Survey on Datasets and Metrics of Textual Question Answering. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2109.12264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, K.; Yoo, P.D.; Yeun, C.; Homouz, D.; Taha, A. A comprehensive survey of text classification techniques and their research applications: Observational and experimental insights. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2024, 54, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, M.J.; Gerstoft, P.; Traer, J.; Ozanich, E.; Roch, M.A.; Gannot, S.; Deledalle, C.A. Machine learning in acoustics: Theory and applications. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 146, 3590–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, V.; Farinas, J.; Pinquier, J. Deep neural networks for automatic speech processing: A survey from large corpora to limited data. EURASIP J. Audio Speech Music Process. 2022, 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chang, L.; Yu, X.; Huang, Y.; Tu, X. A Survey on World Models Grounded in Acoustic Physical Information. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.13833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercauteren, G.; Reviers, N. Audio Describing Sound—What Sounds are Described and How?: Results from a Flemish case study. J. Audiov. Transl. 2022, 5, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.H.; Nieto, O.; Bello, J.P.; Salamon, J. Audio-Text Models Do Not Yet Leverage Natural Language. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Rhodos, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Maks-s. Stable Diffusion Akashic Records. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/Maks-s/sd-akashic (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar]

- Mistral AI. Mistral Models. 2024. Available online: https://mistral.ai/technology/#models (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Anthropic. The Claude 3 Model Family: Opus, Sonnet, Haiku. 2024. Available online: https://anthropic.com/claude-3-model-card (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Koo, R.; Lee, M.; Raheja, V.; Park, J.I.; Kim, Z.M.; Kang, D. Benchmarking Cognitive Biases in Large Language Models as Evaluators. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.17012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, J.; Snieder, R. What is noise? Geophysics 1998, 63, 1122–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Long, Y.; Han, J.; Xu, H.; Liang, X.; Xu, C.; Liang, X. NLIP: Noise-Robust Language-Image Pre-training. In Proceedings of the 37th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; pp. 926–934. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Xu, Z.; Wang, K.; You, Y.; Yao, H.; Liu, T.; Xu, M. BiCro: Noisy Correspondence Rectification for Multi-modality Data via Bi-directional Cross-modal Similarity Consistency. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 19883–19892. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W.; Mun, J.; Lee, S.; Roh, B. Noise-Aware Learning from Web-Crawled Image-Text Data for Image Captioning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 2942–2952. [Google Scholar]

- Belém, C.G.; Seshadri, P.; Razeghi, Y.; Singh, S. Are Models Biased on Text without Gender-related Language? In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024.

- Lin, A.; Paes, L.M.; Tanneru, S.H.; Srinivas, S.; Lakkaraju, H. Word-Level Explanations for Analyzing Bias in Text-to-Image Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.05500. [Google Scholar]

- Zieliński, S.; Rumsey, F.; Bech, S. On Some Biases Encountered in Modern Audio Quality Listening Tests—A Review. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 2008, 56, 427–451. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Kembhavi, A. Don’t Just Assume; Look and Answer: Overcoming Priors for Visual Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4971–4980. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, T.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D.; Tao, D. MirrorGAN: Learning Text-To-Image Generation by Redescription. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1505–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Gan, C.; Rouditchenko, A.; Vondrick, C.; McDermott, J.; Torralba, A. The Sound of Pixels. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 587–604. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Rouditchenko, A. MUSIC Dataset from Sound of Pixels. 2018. Available online: https://github.com/roudimit/MUSIC_dataset (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Parida, K.K.; Matiyali, N.; Guha, T.; Sharma, G. Coordinated Joint Multimodal Embeddings for Generalized Audio-Visual Zero-shot Classification and Retrieval of Videos. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Snowmass Village, CO, USA, 1–5 March 2020; pp. 3240–3249. [Google Scholar]

- Parida, K.K. AudioSetZSL. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/krantiparida/AudioSetZSL (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Thomee, B.; Shamma, D.A.; Friedland, G.; Elizalde, B.; Ni, K.; Poland, D.; Borth, D.; Li, L.J. YFCC100M: The new data in multimedia research. Commun. ACM 2016, 59, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.K. Audio-to-Visual Cross-Modal Generation of Birds. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 27719–27729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Asketorp, J.; Feng, D. Awesome-Video-Datasets. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/xiaobai1217/Awesome-Video-Datasets (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Wang, J.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, H. AlignNet: A Unifying Approach to Audio-Visual Alignment. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Snowmass Village, CO, USA, 1–5 March 2020; pp. 3298–3306. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Deng, L.; Afouras, T.; Owens, A.; Davis, A. Eventfulness for Interactive Video Alignment. ACM Trans. Graphs 2023, 42, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Oh, T.H.; Grauman, K.; Torresani, L. Listen to Look: Action Recognition by Previewing Audio. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1912.04487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, B.; Ma, T.; Liu, L.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Zhou, S.; He, Q.; et al. Phantom-Data: Towards a General Subject-Consistent Video Generation Dataset. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.18851. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulhussain, S.H.; Ramli, A.R.; Saripan, M.I.; Mahmmod, B.M.; Al-Haddad, S.A.R.; Jassim, W.A. Methods and Challenges in Shot Boundary Detection: A Review. Entropy 2018, 20, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, G. A Comparison Between KeyFrame Extraction Methods for Clothing Recognition. 2023. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-507294 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Hou, J.; Su, L.; Zhao, Y. Key Frame Selection for Temporal Graph Optimization of Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Park, J.S.; Yadav, T.; Kusupati, A.; Krishna, R.; Choi, Y.; Hajishirzi, H.; Farhadi, A. ActionAtlas: A VideoQA Benchmark for Domain-specialized Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; Volume 37, pp. 137372–137402. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tokmakov, P.; Hebert, M.; Schmid, C. A Structured Model for Action Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9967–9976. [Google Scholar]

- Waheed, S.; An, N.M. Image Embedding Sampling Method for Diverse Captioning. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Suzhou, China, 5–9 November 2025; pp. 3141–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Xie, Y.; Grundlingh, N.; Chawan, V.R.; Wang, C. Assessing Image-Captioning Models: A Novel Framework Integrating Statistical Analysis and Metric Patterns. In Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on e-eommerce and NLP, Torino, Italy, 21 May 2024; pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xu, M.; Zhan, Y.; Mu, S.; Li, J.; Cheng, K.; Chen, Y.; Chen, T.; Ye, M.; Wang, J.; et al. OpenHumanVid: A Large-Scale High-Quality Dataset for Enhancing Human-Centric Video Generation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 7752–7762. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, L.; Schmid, C.; Varol, G. Learning Text-to-Video Retrieval from Image Captioning. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 133, 1834–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, T.; He, H.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. UltraVideo: High-Quality UHD Video Dataset with Comprehensive Captions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.13691. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.H.; Seetharaman, P.; Kumar, K.; Bello, J.P. Wav2CLIP: Learning Robust Audio Representations from Clip. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Singapore, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 4563–4567. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; de Las Casas, D.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2024; pp. 30016–30030. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L. Revisiting Sample Size and Number of Parameter Estimates: Some Support for the N:q Hypothesis. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2003, 10, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Raj, G.; Choudhury, T. Blur image detection using Laplacian operator and Open-CV. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference System Modeling & Advancement in Research Trends, Moradabad, India, 25–27 November 2016; pp. 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- León, J.E. AVT Multimodal Dataset. 2024. Available online: https://jorvan758.github.io/AVT-Multimodal-Dataset/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Prasad, R. Does mixing of speech signals comply with central limit theorem? Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2008, 62, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehay, D.; Leskow, J.; Napolitano, A. Central Limit Theorem in the Functional Approach. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2013, 61, 4025–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, G.; Zeidan, J.; Goossens, M.M.; Moreira, C. Normality Testing Methods and the Importance of Skewness and Kurtosis in Statistical Analysis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, J.M.; Van der Merwe, S. An empirical study of the behaviour of the sample kurtosis in samples from symmetric stable distributions. S. Afr. Stat. J. 2020, 54, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, J.; De Leon, P. Speech separation by kurtosis maximization. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Seattle, WA, USA, 15 May 1998; Volume 2, pp. 1029–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Yang, D.; Wu, Y. Soundscape diversity: Evaluation indices of the sound environment in urban green spaces—Effectiveness, role, and interpretation. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfer-Lawrence, T.; Desjonqueres, C.; Eldridge, A.; Johnston, A.; Metcalf, O. Using acoustic indices in ecology: Guidance on study design, analyses and interpretation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 2192–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijanowski, B.C.; Villanueva-Rivera, L.J.; Dumyahn, S.L.; Farina, A.; Krause, B.L.; Napoletano, B.M.; Gage, S.H.; Pieretti, N. Soundscape Ecology: The Science of Sound in the Landscape. BioScience 2011, 61, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfer-Lawrence, T.; Duthie, B.; Abrahams, C.; Adam, M.; Barnett, R.J.; Beeston, A.; Darby, J.; Dell, B.; Gardner, N.; Gasc, A.; et al. The Acoustic Index User’s Guide: A practical manual for defining, generating and understanding current and future acoustic indices. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2025, 16, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, R.B.; Tukey, J.W. The measurement of power spectra from the point of view of communications engineering—Part I. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1958, 37, 185–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, D. Speech Communications: Human and Machine; Wiley-IEEE Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 2, p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Bagher Zadeh, A.; Liang, P.P.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal Language Analysis in the Wild: CMU-MOSEI Dataset and Interpretable Dynamic Fusion Graph. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 2236–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, B.A.; Wang, L.; Cervantes, C.M.; Caicedo, J.C.; Hockenmaier, J.; Lazebnik, S. Flickr30k Entities: Collecting Region-to-Phrase Correspondences for Richer Image-to-Sentence Models. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 2641–2649. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Yu, J.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. InternVid: A Large-scale Video-Text Dataset for Multimodal Understanding and Generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2307.06942. [Google Scholar]

- Kassab, H.; Mahmoud, A.; Bahaa, M.; Mohamed, A.; Hamdi, A. MMIS: Multimodal Dataset for Interior Scene Visual Generation and Recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.05980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaglia, P.; Verbelen, T.; Dhoedt, B.; Courville, A.; Rajeswar, S. GenRL: Multimodal-foundation world models for generalization in embodied agents. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.18043. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.; Xie, W.; Zisserman, A. Temporal Alignment Networks for Long-term Video. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.02968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viertola, I.; Iashin, V.; Rahtu, E. Temporally Aligned Audio for Video with Autoregression. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

| Task | Description | Nuances |

|---|---|---|

| Image-to-audio | Based on an image, an audio is generated that conveys the same semantic information as the input image. | Advances have been made in the generation of audios that mimic the possible soundscape for a given image [31,37]. In a similar fashion, audios can also be generated from videos, which are nothing more than an ordered collection of images [35,36]. |

| Text-to-audio | Based on a text, an audio is generated that conveys the same semantic information as the input text. | Some models are able to resemble a human voice reading the text given as input (subtask usually referred to as text-to-speech [34,36,38,39]). Moreover, some even make music [40] and generate lyrics based on text input [41], or they generate sounds that accommodate a given description [31,42,43,44]. |

| Audio-to-image | Based on an audio, an image is generated that conveys the same semantic information as the input audio. | Voice recordings can be used to condition the modification of human faces so their mouths adapt to the corresponding sounds (i.e., lip sync [34,45]), and even the whole face can be created from scratch with the aforementioned recordings [36]. In addition, some models are capable of representing scenarios where a specific audio is produced [31,35]. |

| Audio-to-text | Based on an audio, a text is generated that conveys the same semantic information as the input audio. | The most popular subtask here is probably speech transcription (or recognition) [34,46,47,48]. However, models that remarkably generate text description (or captions) from audios in general have begun to arise in recent years [31,49,50,51]. |

| #1 people: | 15.67% | #16 white: | 3.84% | #31 train: | 2.55% | #46 red: | 1.56% |

| #2 man: | 15.58% | #17 road: | 3.68% | #32 sky: | 2.48% | #47 beach: | 1.55% |

| #3 person: | 9.31% | #18 words: | 3.44% | #33 building: | 2.39% | #48 tree: | 1.51% |

| #4 group: | 9.14% | #19 two: | 3.35% | #34 floor: | 2.32% | #49 bird: | 1.4% |

| #5 car: | 8.93% | #20 driving: | 3.21% | #35 dog: | 2.24% | #50 guitar: | 1.38% |

| #6 playing: | 7.66% | #21 table: | 3.18% | #36 middle: | 2.01% | #51 shirt: | 1.36% |

| #7 sitting: | 7.65% | #22 crowd: | 3.14% | #37 cars: | 1.94% | #52 boat: | 1.35% |

| #8 room: | 7.25% | #23 suit: | 3.13% | #38 holding: | 1.77% | #53 parking: | 1.35% |

| #9 street: | 6.83% | #24 field: | 2.99% | #39 child: | 1.7% | #54 little: | 1.27% |

| #10 background: | 6.6% | #25 water: | 2.97% | #40 trees: | 1.69% | #55 band: | 1.27% |

| #11 down: | 5.8% | #26 front: | 2.96% | #41 riding: | 1.67% | #56 girl: | 1.25% |

| #12 standing: | 4.68% | #27 city: | 2.93% | #42 cat: | 1.67% | #57 truck: | 1.25% |

| #13 woman: | 4.58% | #28 tie: | 2.87% | #43 laying: | 1.66% | #58 bed: | 1.23% |

| #14 walking: | 4.44% | #29 parked: | 2.73% | #44 black: | 1.61% | #59 chair: | 1.19% |

| #15 baby: | 3.93% | #30 stage: | 2.66% | #45 night: | 1.56% | #60 wall: | 1.16% |

| Name of the Dataset | A | I | T | V | # of Samples | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AudioCaps [65] | ✔ | ✔ | >45.5K | Alarms, various objects and animals, natural phenomena, and different everyday environments. | ||

| AudioSet [64] | ✔ | ✔ | >2.0M | 632 audio event classes, including musical instruments, various objects and animals, and different everyday environments. | ||

| CMU-MOSEI [144] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | >3.2K | People speaking directly to a camera in monolog form, intended for sentiment analysis. | |

| Ego4D [71] | ✔ | ✔ | >5.8K | Egocentric video footage of different everyday situations, with portions of the videos accompanied by audio and/or 3D meshes of the environment. | ||

| Flickr30k Entities [145] | ✔ | ✔ | >31.7K | Diverse environments, objects, animals, and activities, with the addition to bounding boxes to the image–text pairs. | ||

| Freesound 500K [31] | ✔ | ✔ | K | Diverse situations, sampled from the Freesound website and accompanied by tags and descriptions. | ||

| HD-VILA-100M [68] | ✔ | ✔ | >100.0M | A wide range of categories, including tutorials, vlogs, sports, events, animals, and films. | ||

| InternVid [146] | ✔ | ✔ | >233.0M | Diverse environments, objects, animals, activities, and everyday situations. | ||

| LAION-400M [63] | ✔ | ✔ | M | Everyday scenes, animals, activities, art, scientific imagery, and various objects. | ||

| LLVIP [70] | ✔ | >16.8K | Street environments, where each visible-light image is paired with an infrared one of the same scene. | |||

| MMIS [147] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | >150.0K | A wide range of interior spaces, capturing various styles, layouts, and furnishings. | |

| MosIT [61] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | K | Diverse environments, objects, animals, artistic elements, activities, and conversations. |

| SUN RGB-D [69] | ✔ | >10.0K | Everyday environments, where each image has the depth information of the various objects in it. | |||

| SoundNet [66] | ✔ | ✔ | >2.1M | Videos without professional edition, depicting natural environments, everyday situations, and various objects and animals. | ||

| WebVid-10M [67] | ✔ | ✔ | >10.0M | Natural environments, everyday situations, and various objects and animals. | ||

| AVT Multimodal Dataset (Ours) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | >2.2M | Musical instruments, various objects and animals, and different everyday environments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

León, J.E.; Carrasco, M. Effectively Obtaining Acoustic, Visual, and Textual Data from Videos. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12654. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312654

León JE, Carrasco M. Effectively Obtaining Acoustic, Visual, and Textual Data from Videos. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12654. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312654

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeón, Jorge E., and Miguel Carrasco. 2025. "Effectively Obtaining Acoustic, Visual, and Textual Data from Videos" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12654. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312654

APA StyleLeón, J. E., & Carrasco, M. (2025). Effectively Obtaining Acoustic, Visual, and Textual Data from Videos. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12654. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312654