2.1. Existing Models and the Methodological Basis for the Component-Oriented One

The design of a complex technical product is based on a component-oriented approach, which allows for detailed consideration of the multi-level component architecture of the product being created. For project risk assessment, this study proposes determining the degree of novelty of the components of the high-tech product being developed. To achieve this, the components of the synthesized product structure are divided into the following groups: “old” components (proven technical solutions), which can serve as reusable components (RCs), and new components that undergo a full cycle of design work and are being implemented for the first time within this high-tech sample, as well as the elements of “old” and “new” components located at a lower level of system decomposition [

7]. In some cases, “old” components may require adaptation if such a solution is deemed appropriate. In turn, “new” components ensure the innovative nature of the designed product.

In this study, project risk is understood as the probability that, during the execution of design work for the creation of a new high-tech product, the result will not meet the requirements of the technical specifications.

When assessing risks, it is important to consider difficulties in formalization and quantification of certain types of risks, e.g., operational ones, due to the presence of the “human” factor. Therefore, to assess project risk, it is necessary to quantitatively or qualitatively evaluate the components’ degree of novelty in the developed high-tech system.

One of the most comprehensive methods used to analyze and evaluate various factors in many industries is risk assessment [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. These methods are widely used in construction, energy, economics, and other industries to assess the reliability of systems under the influence of various factors [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

In assessment of the project risk when designing a high-tech system considering the novelty degree of its components, it is advantageous to apply a fuzzy set approach for qualitative evaluations, incorporating expert information (expert assessments) [

20,

21]. Fuzzy set theory (fuzzy logic) allows for the use of both quantitative and qualitative characteristics in assessments, and it enables the analysis of heterogeneous and insufficiently large data samples, which can be helpful when available information is limited or costly [

22].

The paper [

23] introduces an integrated risk assessment model combining Pythagorean Fuzzy Dimensional Analysis (PFDA) and Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA), with a machined detail as a case study. The study [

24] proposes a multi-criteria decision-making method combining AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) and TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to the Ideal Solution) to prioritize project risks at the activity level, addressing limitations of traditional risk assessments. Applied to Global Furniture Ltd., the hybrid AHP-TOPSIS model enables quantitative risk analysis, enhancing project time, quality, and cost management.

Another direction of risk assessment is the theory of qualimetry. Scientific publications [

25,

26] present the methodology of risk assessment of the quality of technological processes. The methodology for assessing the quality risks of socio-economic systems is presented in scientific publications [

27,

28,

29,

30], which is characterized by the use of function-dependent statistics. These methodologies have not been tested in assessing the risks of project works.

Although a wide range of risk assessment methods has been developed, including FMEA, PFDA, AHP–TOPSIS hybrid approaches, and qualimetric models, they have several important limitations when applied at the early design stage of a high-tech product, especially UAVs.

First of all, most existing models do not account for component-level novelty. They consider a product as a uniform system and do not distinguish between reusable, adapted, and newly developed components. As a result, these methods cannot adequately reflect the innovation-driven risks that arise when integrating new components into a complex architecture.

Secondly, the traditional approaches poorly handle the inherent fuzziness and uncertainty typical for early design phases. At this stage, quantitative data are usually unavailable, while expert information is often incomplete or subjective. Consequently, the methods relying on precise numerical inputs lose accuracy or applicability.

Thirdly, existing models are primarily activity-oriented rather than component-oriented. For example, FMEA–PFDA or AHP–TOPSIS hybrids prioritize project activities or process-level risks but do not provide a means to link risk assessment directly to individual components within a multi-level system decomposition.

And finally, most traditional methods are static, and cannot dynamically adjust risk levels when the degree of novelty of components changes due to iterative design processes or architecture updates.

To overcome these limitations, the present study proposes a component-oriented model for risk assessment that incorporates fuzzy set theory and explicitly accounts for the degree of component novelty. This enabled both qualitative and quantitative evaluation of risks under uncertainty and provided more accurate decision support at the conceptual and preliminary design stages of complex high-tech systems like UAVs.

Recently, research in the domains of modular product architectures and fuzzy-logic risk assessment has advanced significantly. For example, Xuan et al. developed a fuzzy Petri-net-based model to evaluate risk and vulnerability in complex engineering projects [

31]. Mansor & Flayyih applied fuzzy synthetic evaluation to assess the risks of modular (prefabricated) construction systems [

32]. Similarly, quality risk in prefabricated steel components was addressed using a fuzzy Bayesian-network approach [

33].

While these studies contribute important advances, they often focus either on modularization decisions or on fuzzy risk evaluation in isolation. By contrast, the model proposed in this paper integrates component-level novelty (reuse, adaptation, new development) within a modularized product architecture and applies a fuzzy linguistic evaluation framework to capture the early-stage uncertainty typical of high-tech design. This coupling of modular component categorization with fuzzy risk modeling, at the early design phase, represents a distinctive incremental contribution to the state of the art.

2.2. The Component-Oriented Model for Risk Assessment

For project risk analysis, i.e., determining the level of risk, the novelty degree of the components of the new high-tech product and the concept of the impact of risk-generating factors are used, which can be represented as linguistic variables [

34]. The values of each of these linguistic variables must be converted into respective fuzzy values. For this purpose, a triangular membership function is commonly used.

The proposed component-oriented model for project risk assessment in the early stages of developing a technical system includes the following steps:

Step 1. Risk identification and identification of risk-generating factors.

In the design of an HTP, it is necessary to distinguish between basic groups of risks and the intra-group risk factors that contribute to the occurrence of specific types of risks and relate to the basic risk group x1, x2, …, xn, j = 1…n.

Step 2. Formation of the scope of project work for the creation of the HTP.

The project work includes tasks related to the adaptation of reusable components, acquisition of reusable components, and development of new components. Acquiring ready-made components for the creation of the HTP from available markets helps reduce the development costs.

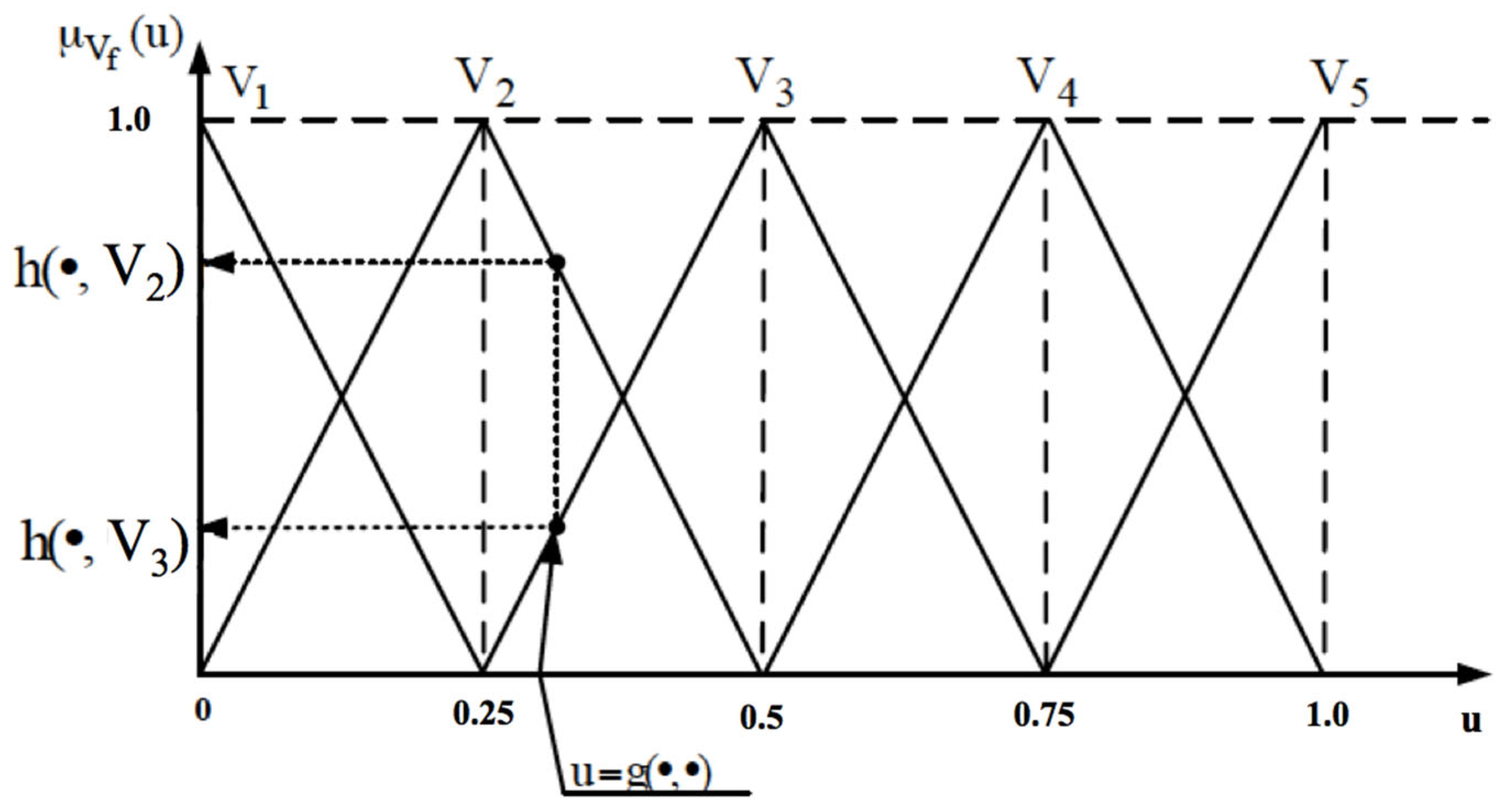

Step 3. In this step, the values of linguistic variables are assigned via a triangular membership function, making it possible to consider the risk factor

r and the indicator of the risk factor importance

s. It is important to note that the membership functions

µVf (

r) and

µVf (

s) take the same form as the general triangular membership function [

35].

At this stage, a scale is constructed to map linguistic variables to fuzzy numbers. This scale facilitates the transformation of qualitative assessments (linguistic descriptions) into corresponding fuzzy values, allowing for a more structured and quantifiable analysis of the risk level and the importance of each risk factor. The scale of relations between linguistic variables and fuzzy numbers is shown in

Table 1.

In

Table 1,

Nrk and

Nsk denote the fuzzy numbers describing the linguistic variables for the importance of the risk factor and the risk level of the risk-generating factor, respectively;

i represents the number of a single linguistic variable value (

i = 1…

k); and

k denotes the number of linguistic variables representing the risk level

r and importance of the risk factor

s.

For example, the number of values of linguistic variables for assessing the risk level and the importance of the risk factor can be equal to 5 (

k = 5):

V1—very low;

V2—low;

V3—medium;

V4—high; and

V5—very high. This number of linguistic variable values was selected because a five-level linguistic scale is widely used in fuzzy risk assessment practice [

36], providing an optimal balance between the accuracy of differentiation and the simplicity of expert judgment. Using fewer levels (e.g., three) would reduce the resolution of evaluations, while a larger number of levels would not significantly improve precision and might increase subjectivity and inconsistency in expert assessments. Thus, it was assumed that

k = 5 ensured both methodological soundness and comparability with other fuzzy evaluation studies.

Linguistic variables are shown in

Table 2, for both risk levels and importance of risk factors.

Next, the linguistic variables of the risk s and r are replaced by the respective fuzzy triangular numbers Ns and Nr.

Step 4. Assessment of the importance of factors sj based on the preliminary classification of project work, considering the novelty degree of the HTP components.

The novelty of the components in the new product always affects the importance of the factor that generates the risk. This means that components with a higher degree of novelty are likely to have a greater influence on the significance of the associated risk-generating factors

sj:

where

sj1—the linguistic evaluation of the importance of the

j-th factor generating a risk, associated with acquisition of a reusable component;

sj2—the linguistic evaluation of the importance of the

j-th risk-generating factor for the group of work related to the adaptation of RCs; and

sj3—the linguistic evaluation of the importance of the

j-th risk-generating factor for the group of project work related to the creation of new components.

Formula (1) represents a matrix of linguistic evaluations of the importance of each risk-generating factor sj in relation to the groups of project tasks classified by the degree of novelty of the components of the high-tech product. Each row of the matrix corresponds to a particular group of project works: acquisition of reusable components (RCs), adaptation of RCs, and development of new components. Each column represents an individual risk-generating factor. Accordingly, the elements sj1, sj2, and sj3 denote the linguistic values (e.g., very low, low, medium, etc.) expressing the importance of the j-th factor for the corresponding group of project works.

This representation enables the formalization of expert assessments that capture how the novelty of components influences the weight of the specific risk factors. The obtained matrix serves as an initial dataset for further fuzzy processing and defuzzification procedures aimed at determining the aggregated project risk at the early design stage.

Dependent on the novelty of the designed components, the project work is analyzed in three groups, as follows: project work related to the acquisition of RCs, project work for the adaptation of RCs, and project work for the creation of new components. It was assumed that the value describing the importance assessment for all risk-generating factors in the project works related to the acquisition of RCs, which do not require adaptation, will be approximately the same. It should be noted that this group of work is the least exposed to risk-generating factors.

At the same time, in the creation of an HTP, part of the components of the structure of the new technical product may be RCs that require adaptation. The second group of project work is more sensitive to external economic risks. The third group consists of work related to the novelty and uniqueness of the HTP being developed. It is the most vulnerable to the impact of risk-generating factors related to the technical risk.

Step 5. Evaluation of the specific risk-generating factors rj.

For each specific factor, the probability of the risk factor manifesting and its potential impact were assessed. To evaluate the level of each risk-generating factor

rj, a special probability and impact matrix is used. The probability and impact matrix is created based on survey results and expert assessments, establishing a correlation between the probability level and the impact of a single factor [

37,

38]. The matrix allowed for the factors to be prioritized according to the importance of their possible effects on the HTP being developed.

In the points of intersection between the rows and columns in the probability and impact matrix, the risk level values for the factor rj are assigned. The risk levels of the factors rj are determined based on the characteristics of each specific risk-generating factor. For the factor rj, the risk level value depends on the nature of that particular risk-generating factor.

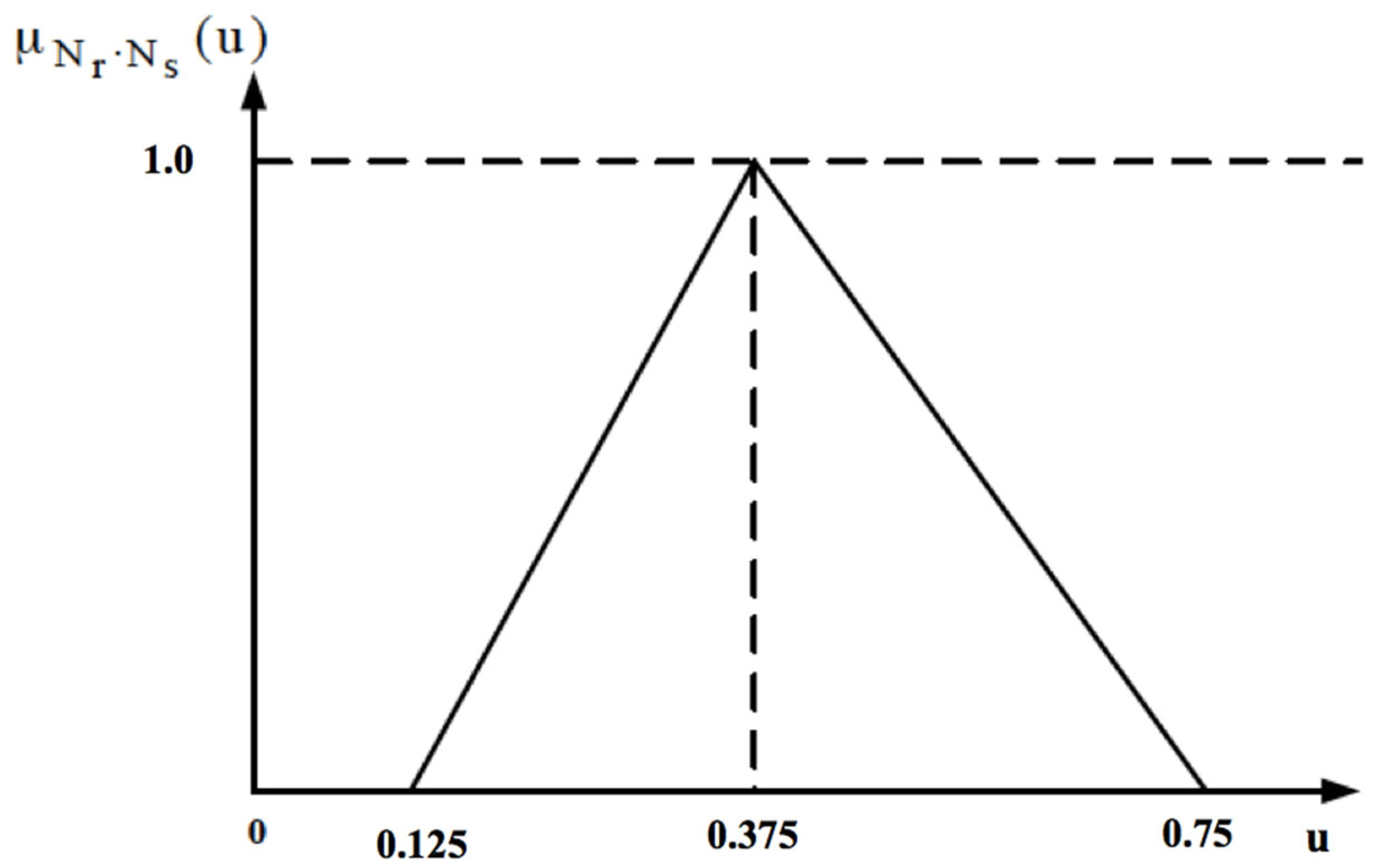

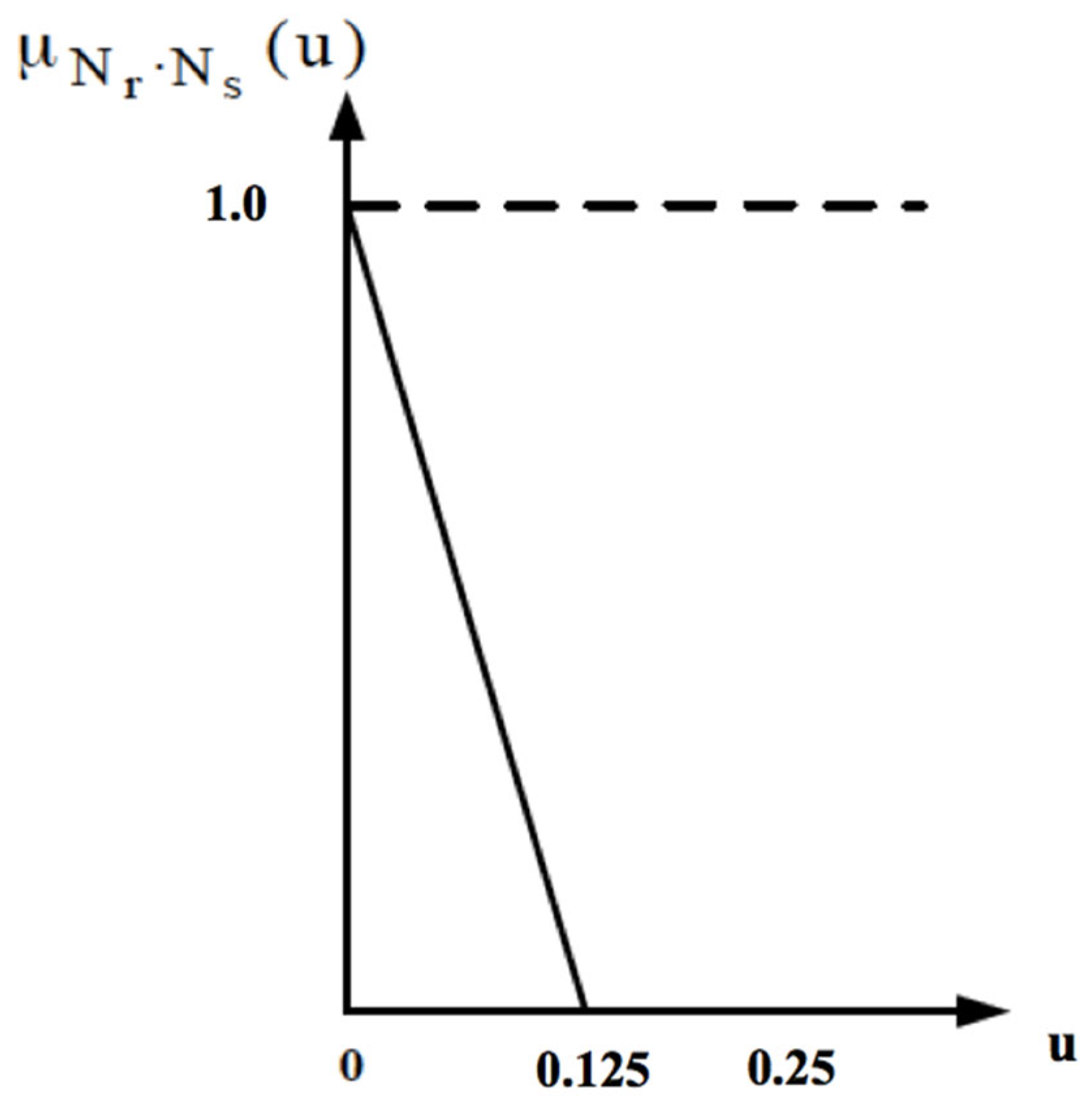

Step 6. Since rj and sjt (where t is the number of the project work group based on the novelty degree of the parts of the system, t = 1…3) are represented as linguistic variable values by fuzzy numbers, a defuzzification procedure, i.e., elimination of fuzziness, is necessary.

To assess project risk at the initial stages of system development, a matrix must be created, with project works as rows and risk-generating factors as columns. At the intersection of the matrix’s rows and columns, the values gjtw (rj, sjt) are indicated, representing the risk level of each factor rj, taking into account its importance sjt, depending on the work grouped by the degree of novelty of the components of the HTP. Here, refers to the number of the project task. And w is the number of the project work.

Operations with triangular numbers are reduced to operations with the abscissas of the vertices of the membership functions, as follows:

where (

a1,

b1,

c1)—the first fuzzy triangular number; and (

a2,

b2,

c2)—the second fuzzy triangular number.

Calculations for defuzzification are performed using the centroid method of defuzzification [

39]. Finally, a matrix of values

gjtw (

rj,

sjt) can be built.

A matrix for all values of g(r, s) containing all intersections of the values for each rj and sj can be predefined in order to simplify calculations.

Step 7. Determining the fuzzy matrix H of intersections, considering importance and the membership functions of the triangular numbers for each project task wit. As a result, produced pairs of values provide the bounds of the confidence interval.

The fuzzy matrix is determined by intersecting each value from the matrix created when performing step 6, gjtw (rj, sjt), with the membership functions of the triangular numbers, µvφ(u) and µvφ+1(u); moreover, φ = 1, 2, …, k − 1. Thus, h(gjtw(rj, sjt), Vφ−1) = 1 − h (gjtw(rj, sjt), Vφ), and h(gjtw(rj, sjt), Vf) = 0, for any f, where f ≠ φ and f ≠ φ + 1.

The fuzzy matrix

H is as follows:

where

m represents the number of all project tasks.

The fuzzy matrix of intersections of all possible risk level values for the factors H’ can be pre-evaluated, considering importance g (r, s) and the respective membership functions of the triangular numbers µvφ(u) and µvφ+1(u).

Step 8. Assessment of a fuzzy risk based on the aggregation of the possible risk factors for every project task related to RC adaptation or fabrication of new components for the high-tech product, using the following formula:

where

j is the index of the intra-group risk factor, with

j = 1…

n;

αj = 1/(

n·

d), so, accordingly, 0 ≤

αj ≤ 1;

d is the total number of groups of project tasks related to the adaptation of RCs and fabrication of new components required for the product being created;

n is the number of intra-group risk factors; and

Vf is the membership functions for linguistic variables, with

f = 1…

k.

Step 9. Assessment of a fuzzy risk based on the aggregation of all risk factors for each group of project tasks related to the adaptation of RCs or the fabrication of new components

Rfh, using the following formula:

where the sum is over

w = 1…

L, and

L is the number of project tasks included in the group of tasks for the adaptation (modernization) of RCs or the creation of new components.

Step 10. Assessment of a fuzzy risk based on the aggregation of all risk factors across all project tasks grouped in relation to the adaptation of RCs or the fabrication of new components

Rfpr:

where the sum is over

h = 1…

d;

h refers to the number of the project task group related to the adaptation of RCs and the fabrication of new components.

Step 11.

g(

Vf)—the centroid value of

Vf of the linguistic variable

V:

where [

af, cf]—the limits of the integrals.

The risk assessment for a group of project tasks related to the adaptation (modernization) of RCs or the creation of new components is conducted as follows:

where the sums are over

f = 1…

k.

The risk assessment of the project for creating a new product, related to its novelty, is determined by defuzzifying the fuzzy assessment using the centroid method.

where the sums are over

f = 1…

k;

Rpr is the probability of achieving a non-satisfactory result.

One of the distinguishing features of the proposed component-oriented risk assessment model at the early stages of design is that this model is applicable not only for assessing the overall project risk of the HTP being developed but also for individual groups of project tasks related to the adaptation (modernization) of selected precedent RCs or the creation of new components.

Another feature of the proposed model is that the risk levels of factors rj are determined based on the characteristics of each risk-generating factor using a probability and impact matrix. Thus, the impact of risk on the execution of tasks is defined by two key characteristics: the novelty of the part or subunit in the structure of the HTP being created and the risk level of each factor.

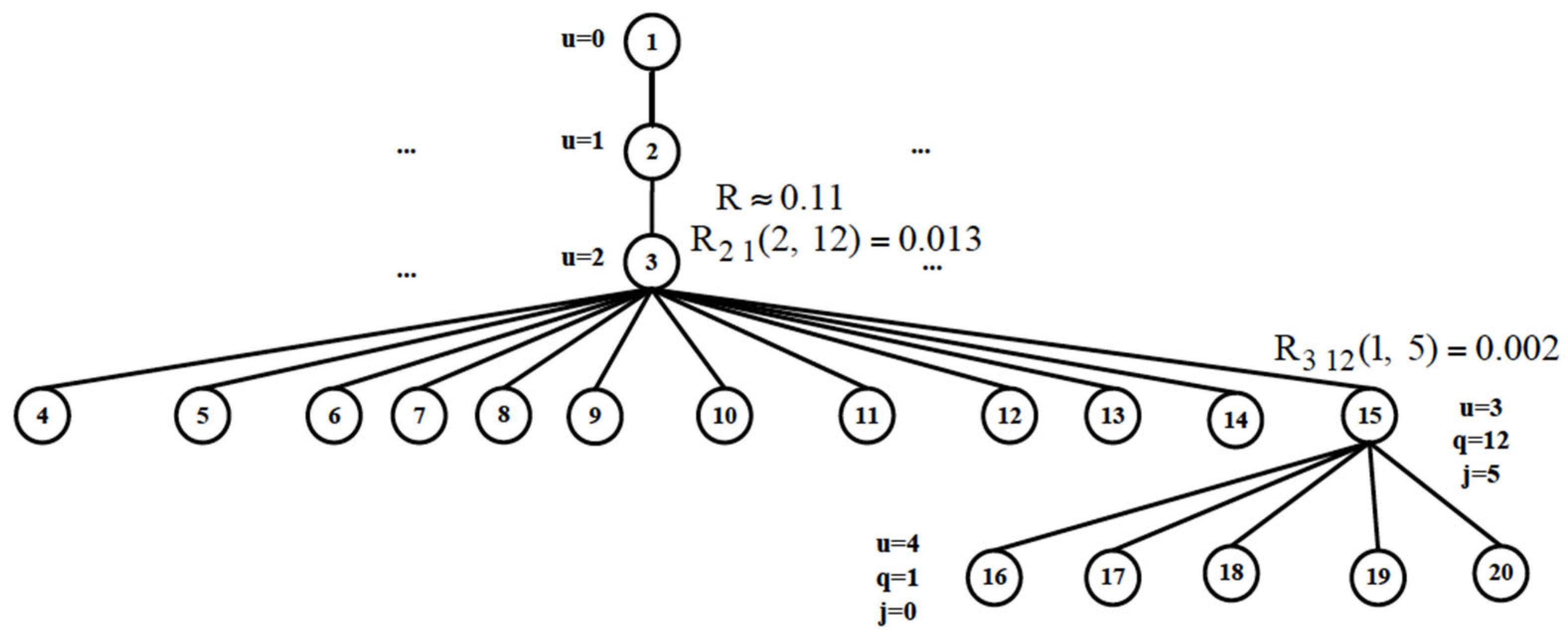

When assessing project risk, in addition to the novelty of the components, the complexity of the structure of the high-tech product is also considered in this study. A multi-level system decomposition is analyzed, including the risk of integrating components at nodes, the complexity of the node, and the number of components (lower-level sub-nodes) in the designed node. Thus, the project risk assessment associated with the complexity and novelty of the product being developed is carried out using the following formula:

where

m is the number of decomposition levels of the high-tech product being designed. Project risk assessment is carried out starting from the lowest level of the product structure (

u =

m − 2) and concludes at the system level as a whole (

u = 0).

Ruq(

i,

j) is the risk of integration for the

q-th node at the

u-th decomposition level of the product, with

i-th complexity and the number of components (sub-nodes at (

u + 1)-th level) in the node

j;

nu represents the number of components at the

u-th decomposition level of the high-tech product.

The proposed component-oriented fuzzy model is conceptually consistent with the general risk management process defined in ISO 31000 [

40] and IEC 31010 [

41] standards, particularly addressing the “risk assessment” phase, which includes the stages of risk identification, analysis, and evaluation. Within the model, risk identification is achieved through decomposition of the high-tech product into components and linking the corresponding risk-generating factors to groups of project works according to the degree of novelty of components. Risk analysis is conducted using fuzzy set theory, which allows for the inclusion of linguistic expert judgments and uncertainty inherent to the early design stage. Risk evaluation is performed through defuzzification and aggregation procedures, enabling the comparison of calculated risk levels with acceptable thresholds.

In contrast to traditional ISO-based approaches that operate mainly at the system or organizational level, the proposed model introduces a component-oriented representation of risk, allowing for detailed assessment of how component novelty and integration complexity affect project outcomes. Consequently, it serves as a methodological extension of existing frameworks by providing a practical tool for component-level and early-stage design risk assessment in high-tech product development.