Research on Anti-Underride Design of Height-Optimized Class A W-Beam Guardrail

Abstract

1. Introduction

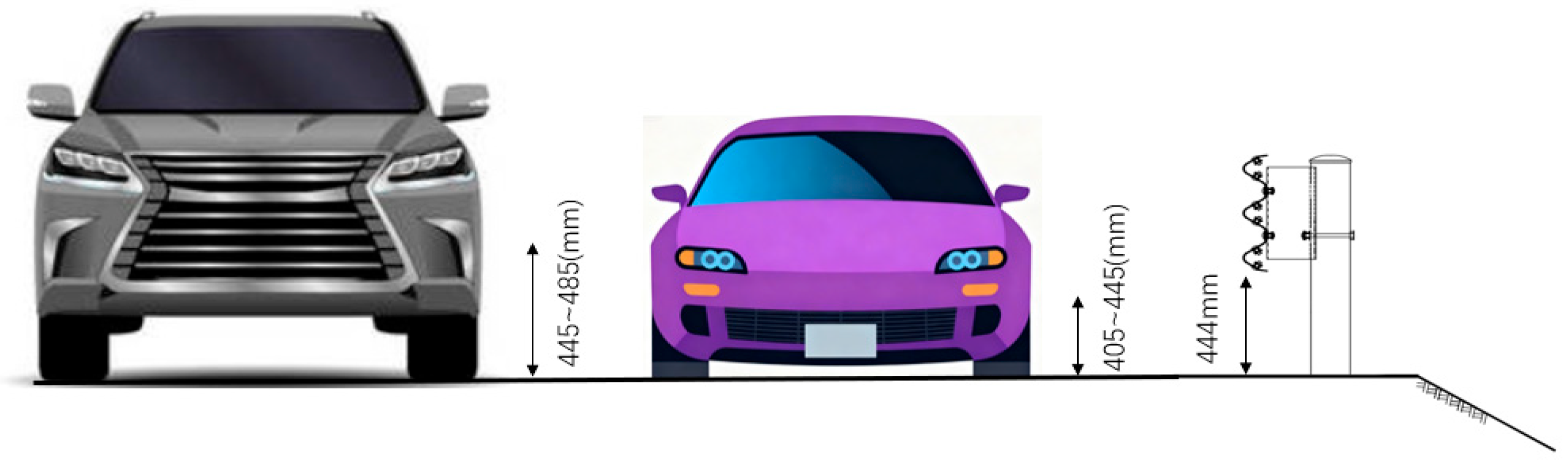

2. Collision Risk Analysis of Triple-W-Beam Guardrail

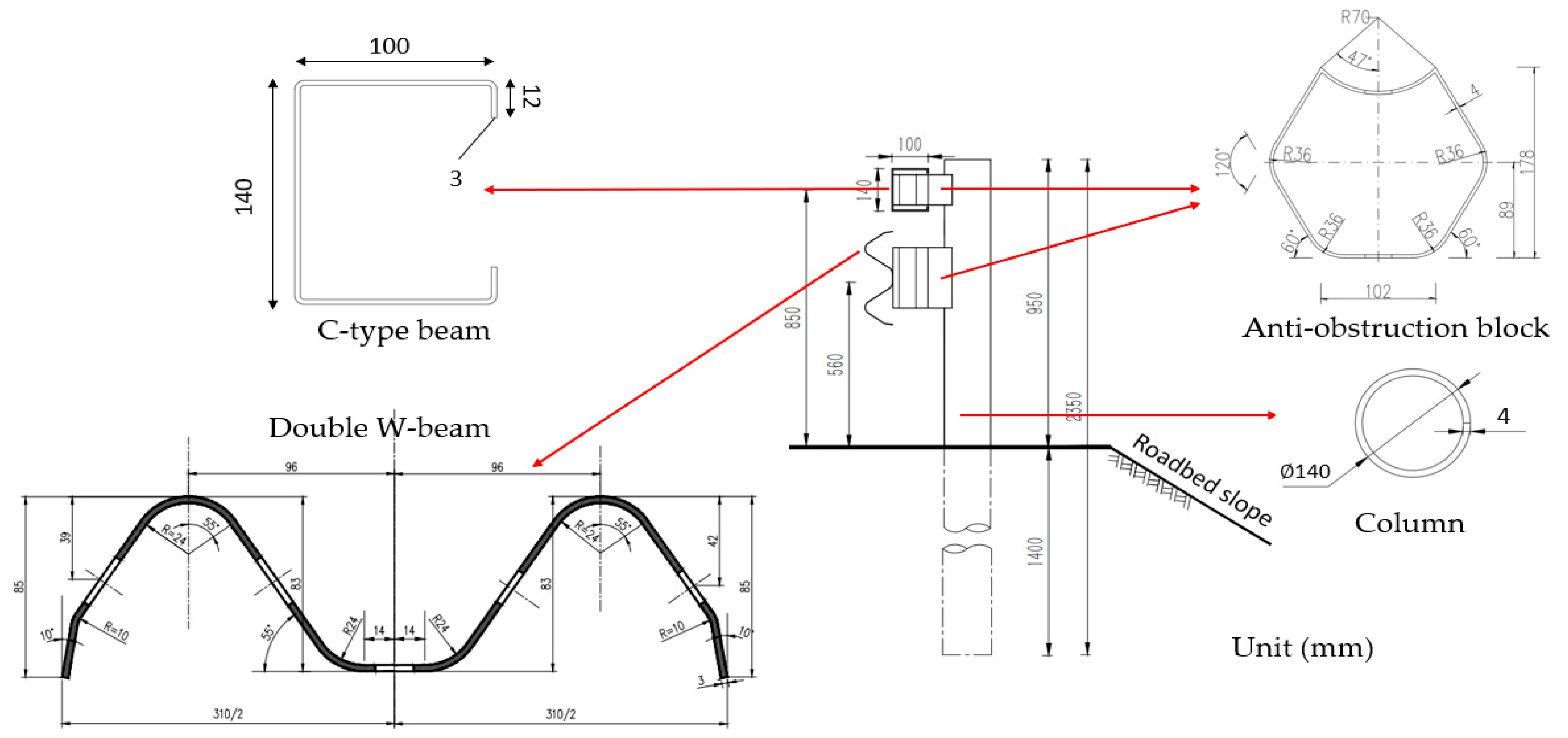

3. Improvement Schemes for W-Beam Guardrail Structure

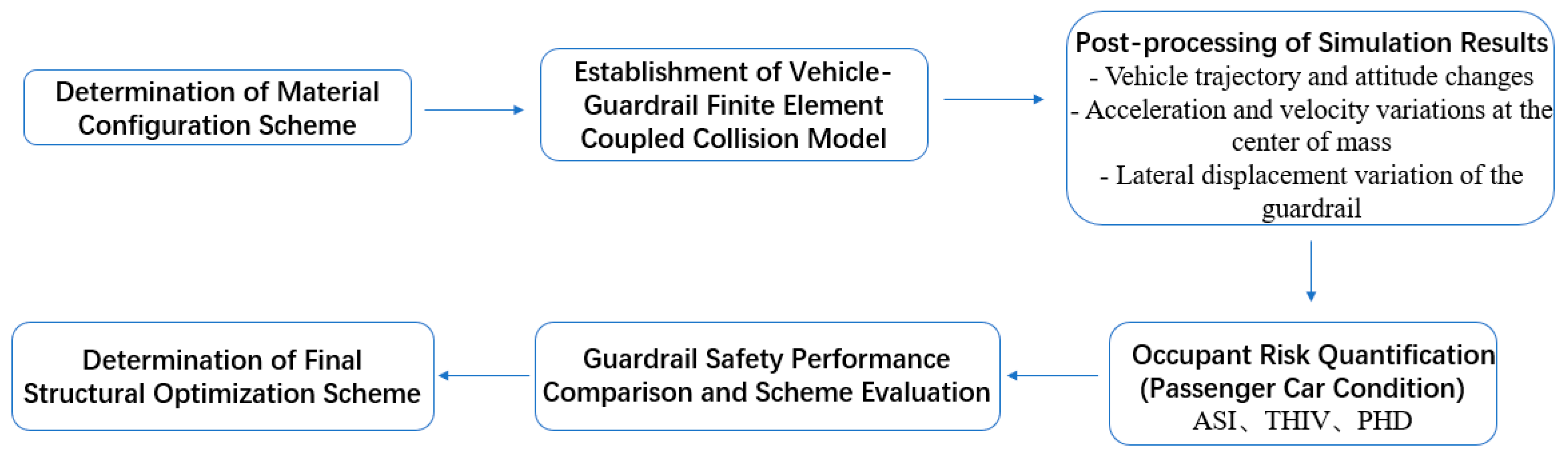

4. Design of Simulation Experiments

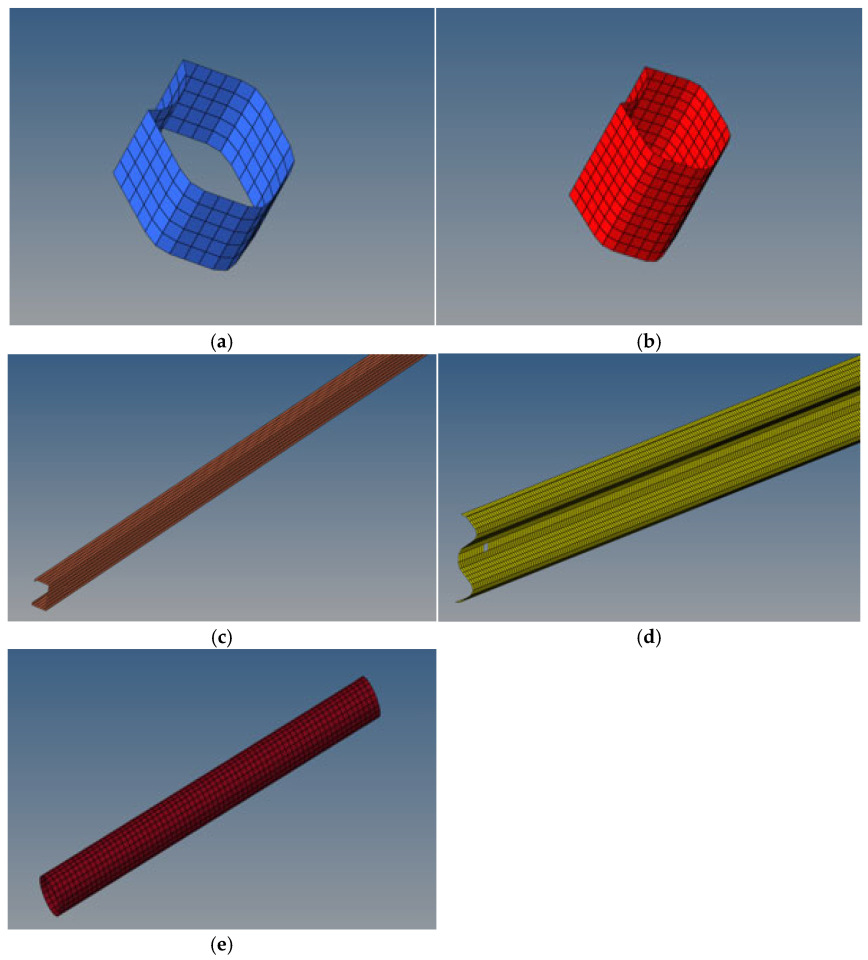

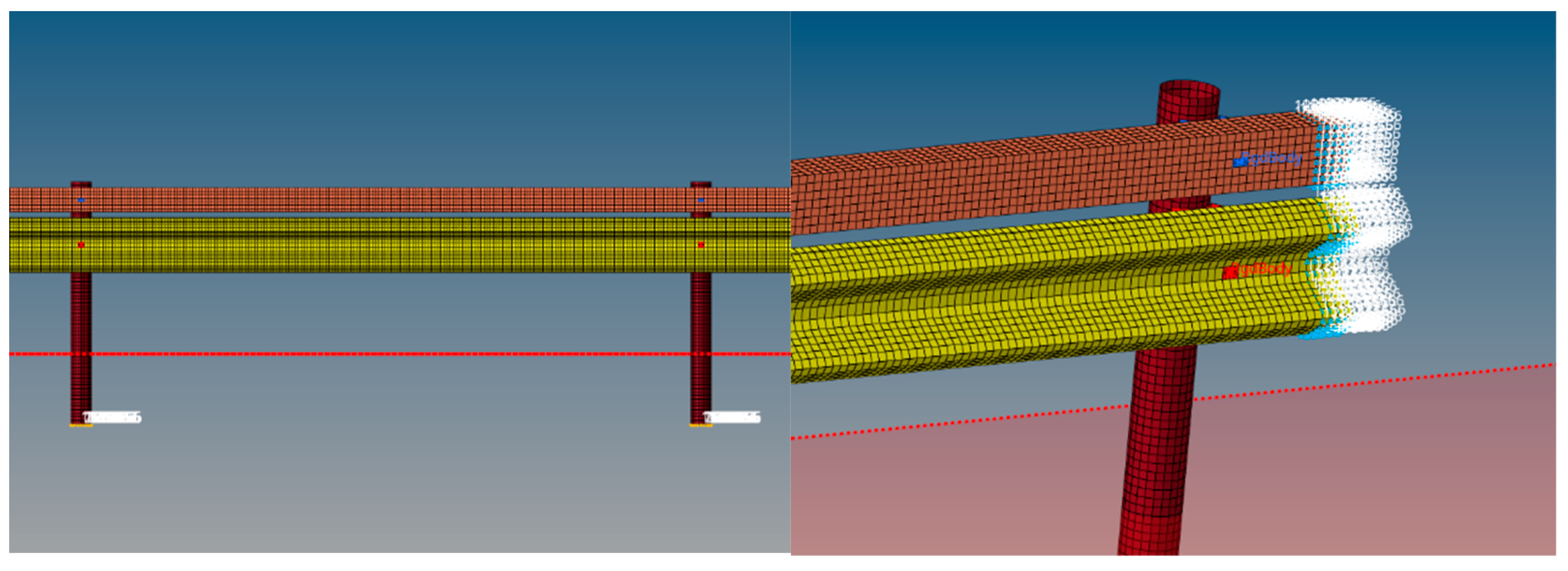

4.1. Finite Element Model of Guardrail

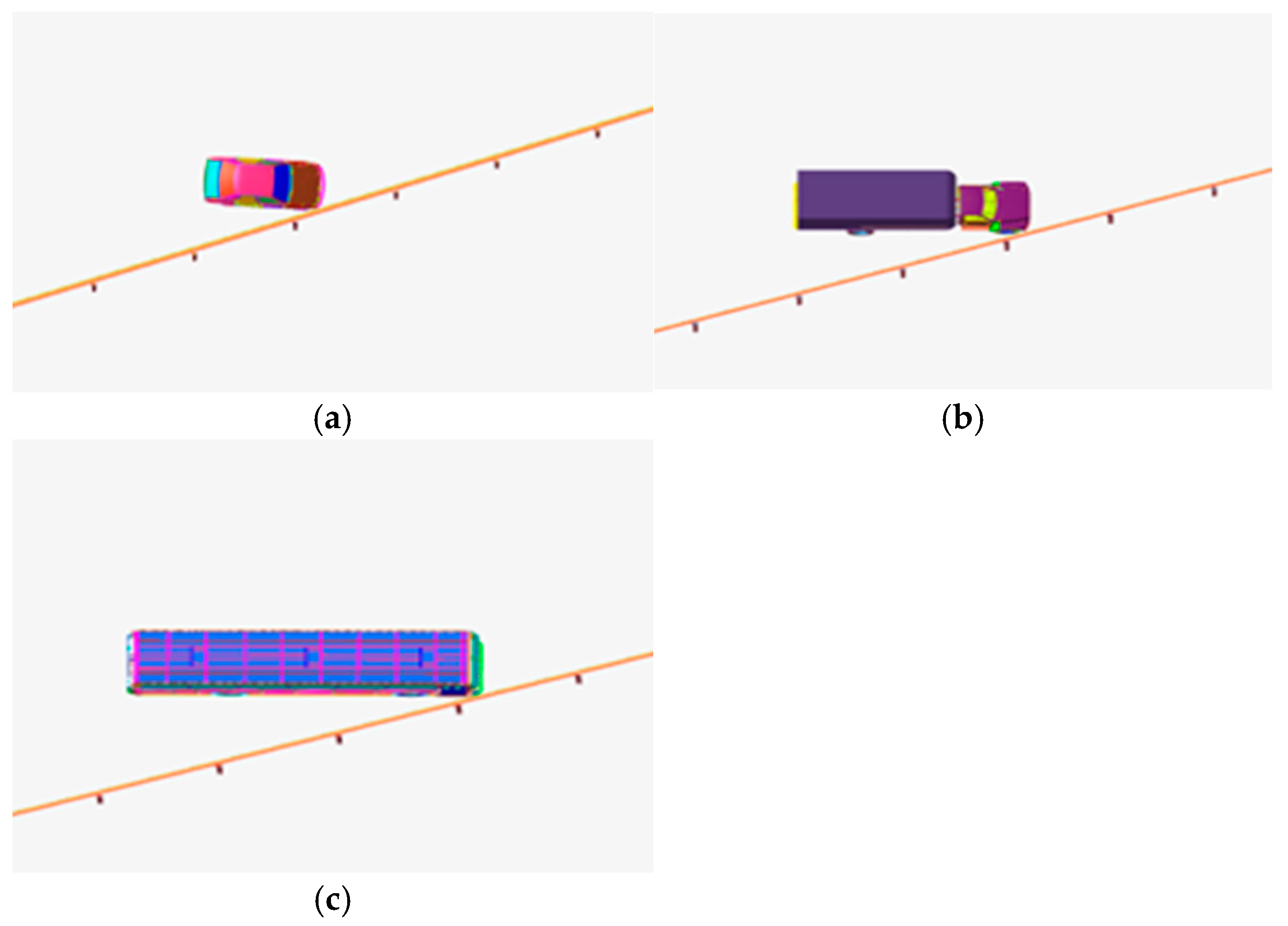

4.2. Vehicle–Guardrail Collision Coupling System

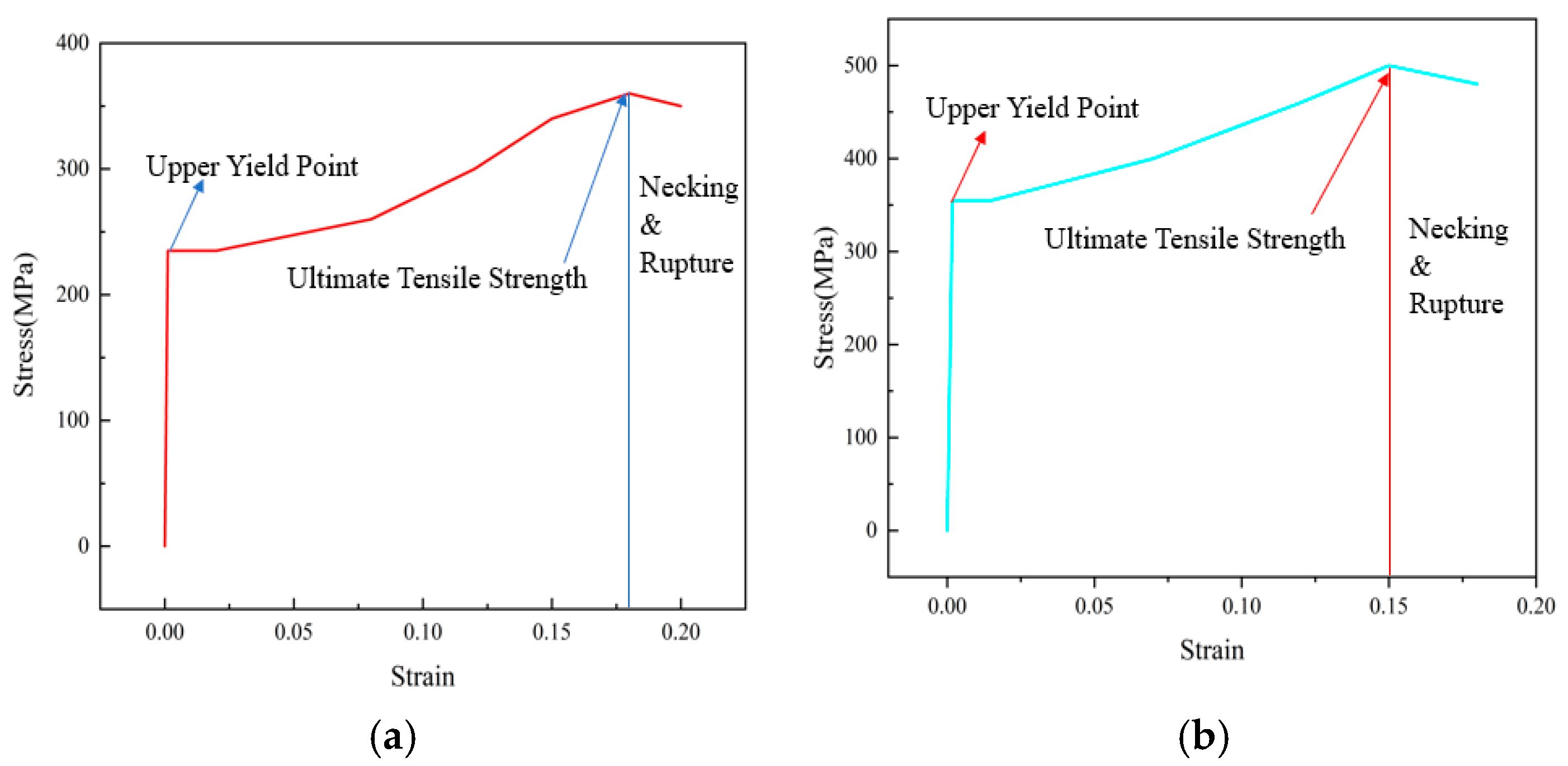

4.3. Material Properties

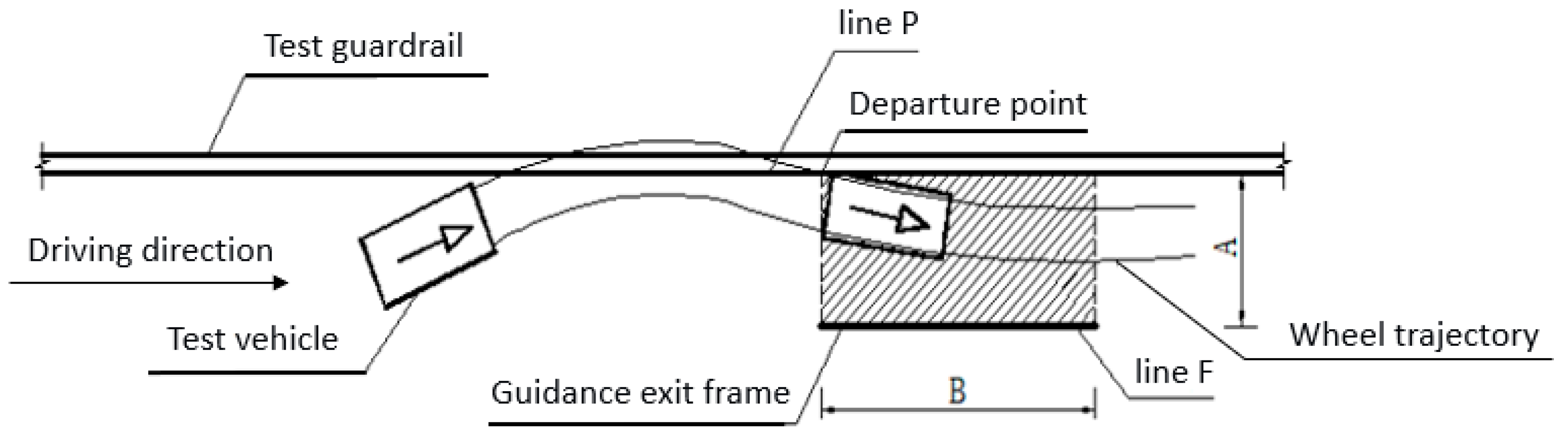

4.4. Protection Performance Evaluation Index

4.5. Quantitative Indicators of Occupant Risk

5. Analysis of Vehicle Crash Process

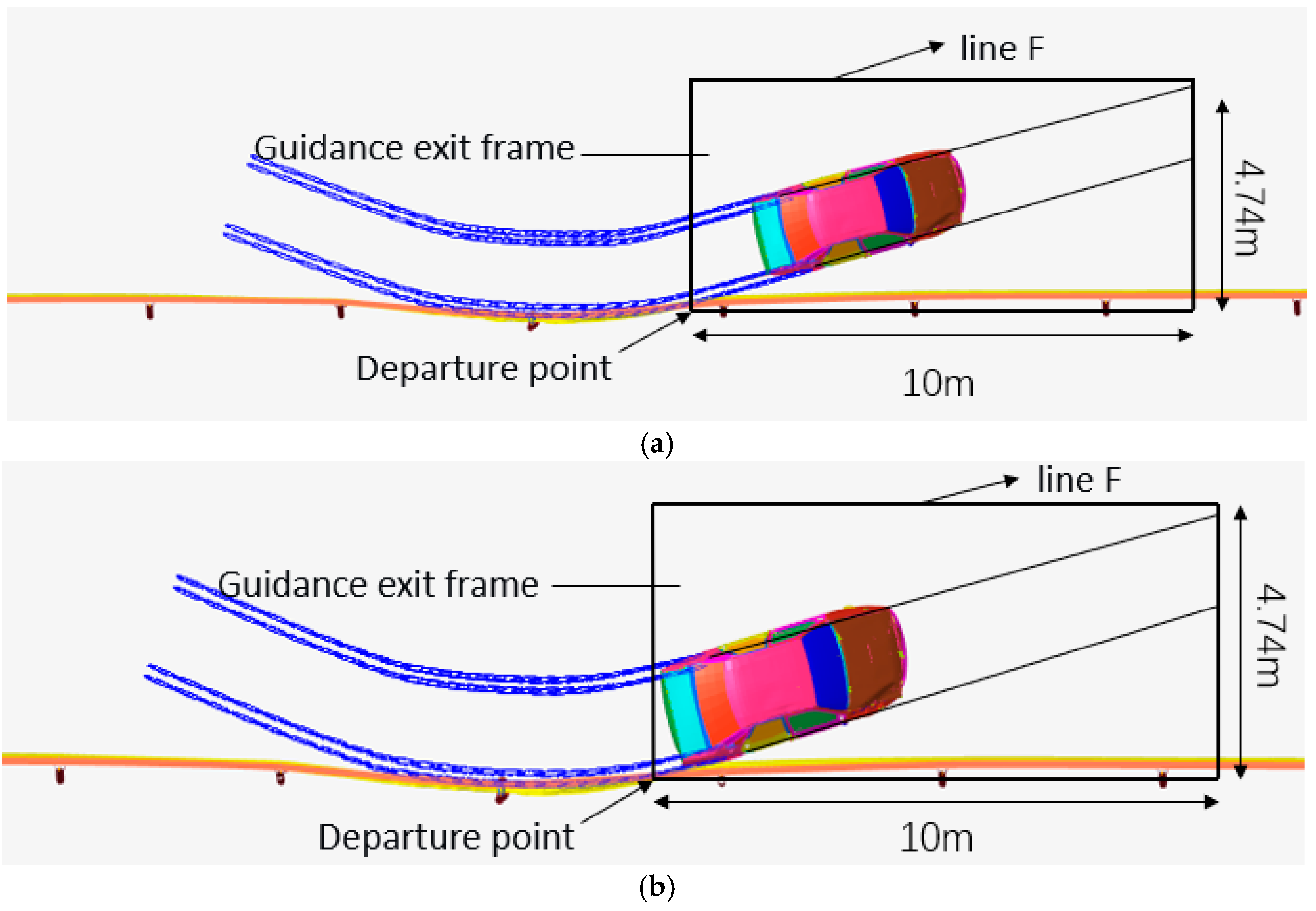

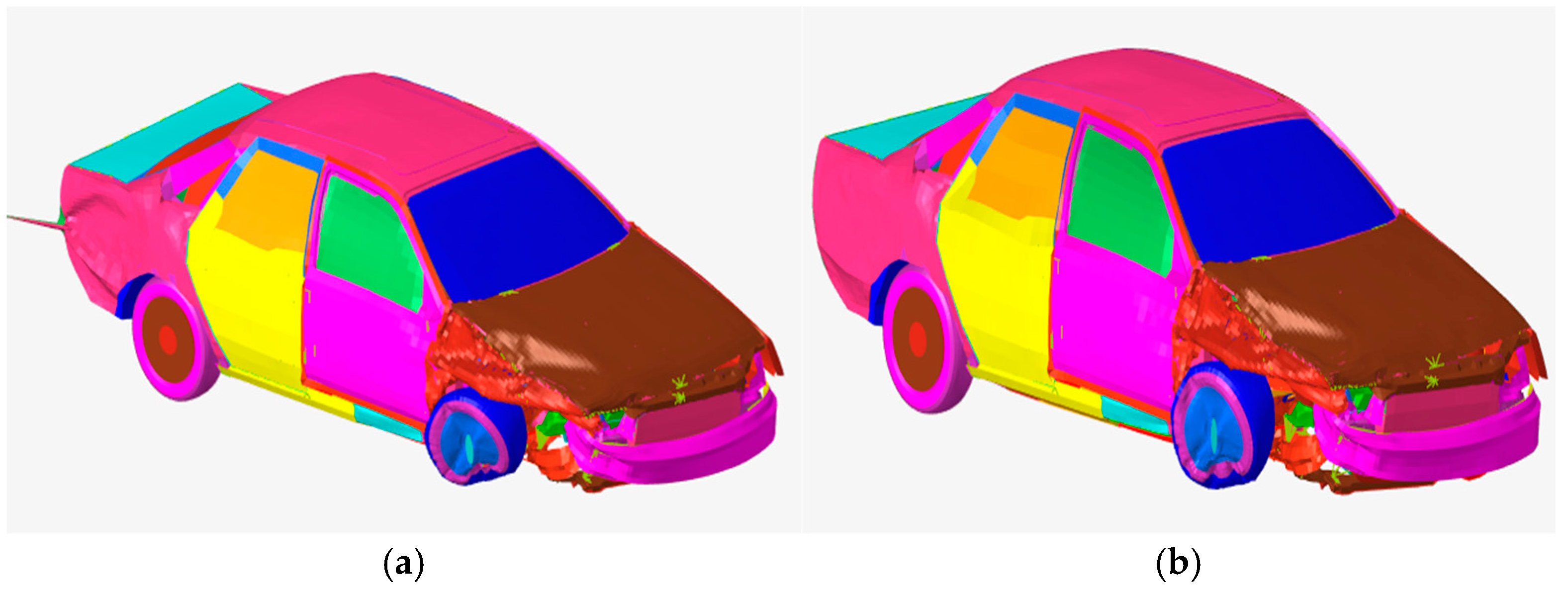

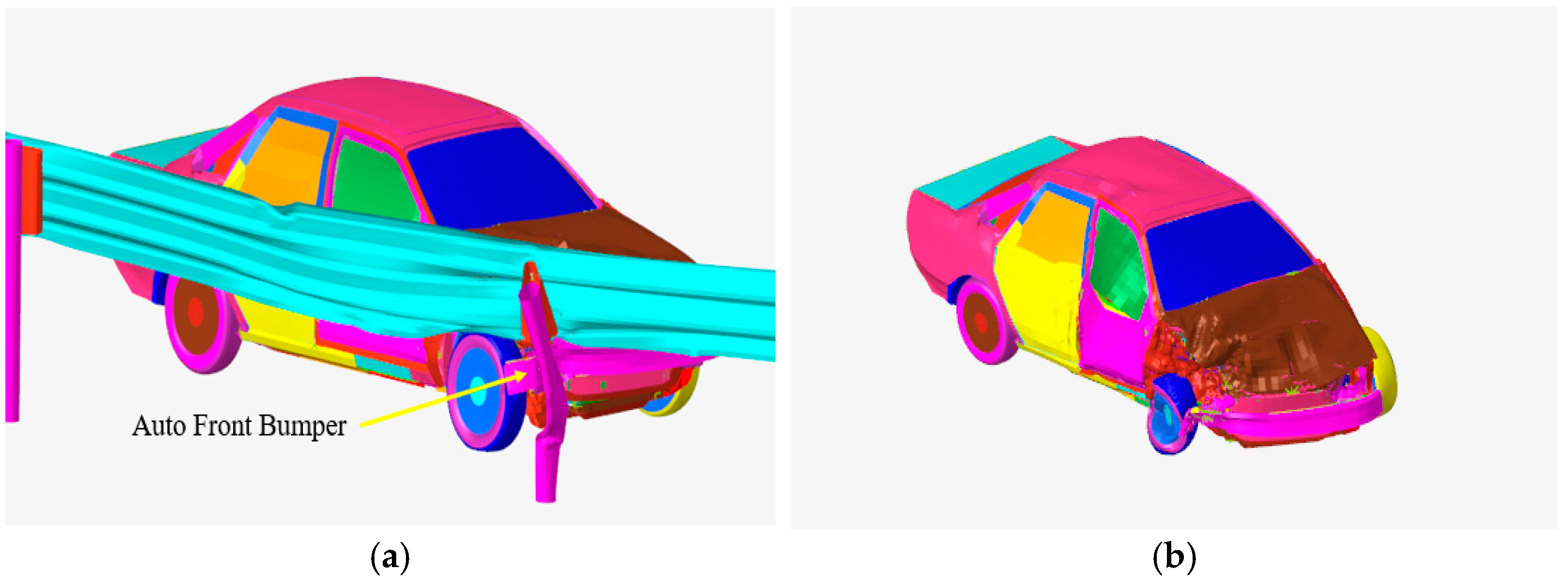

5.1. Analysis of Small Passenger Vehicle Crash

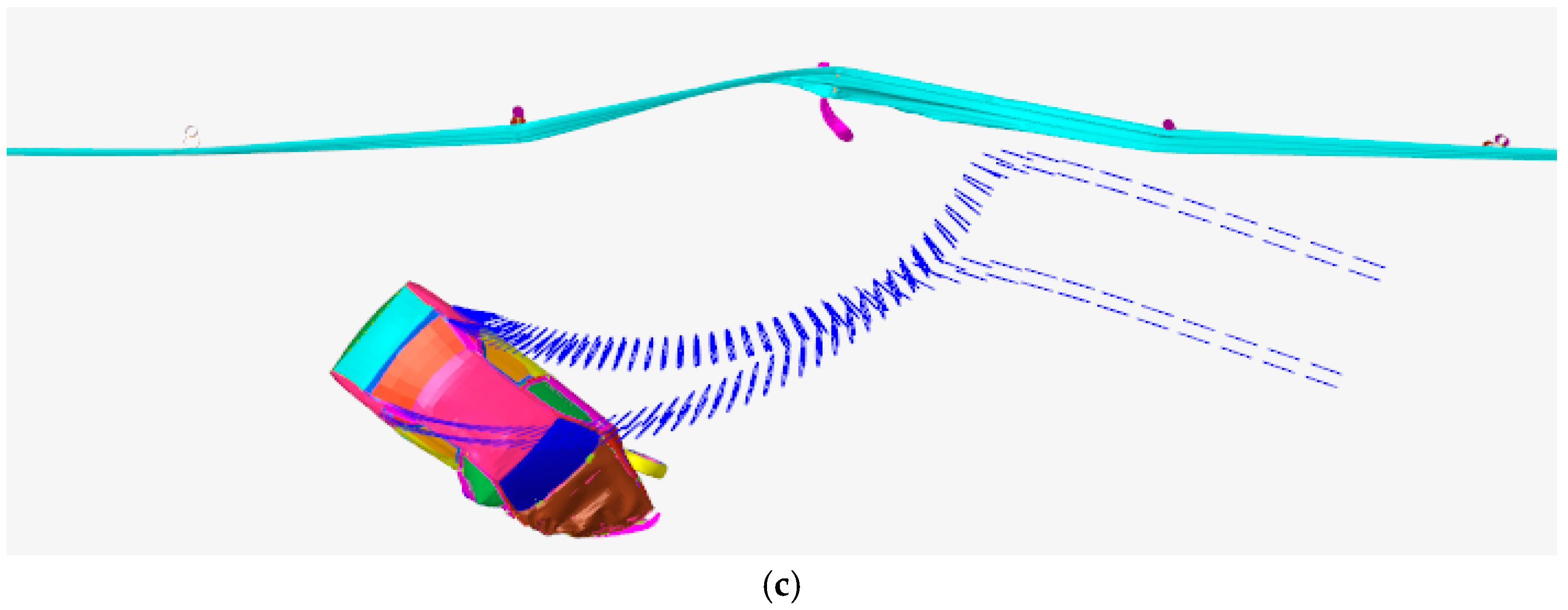

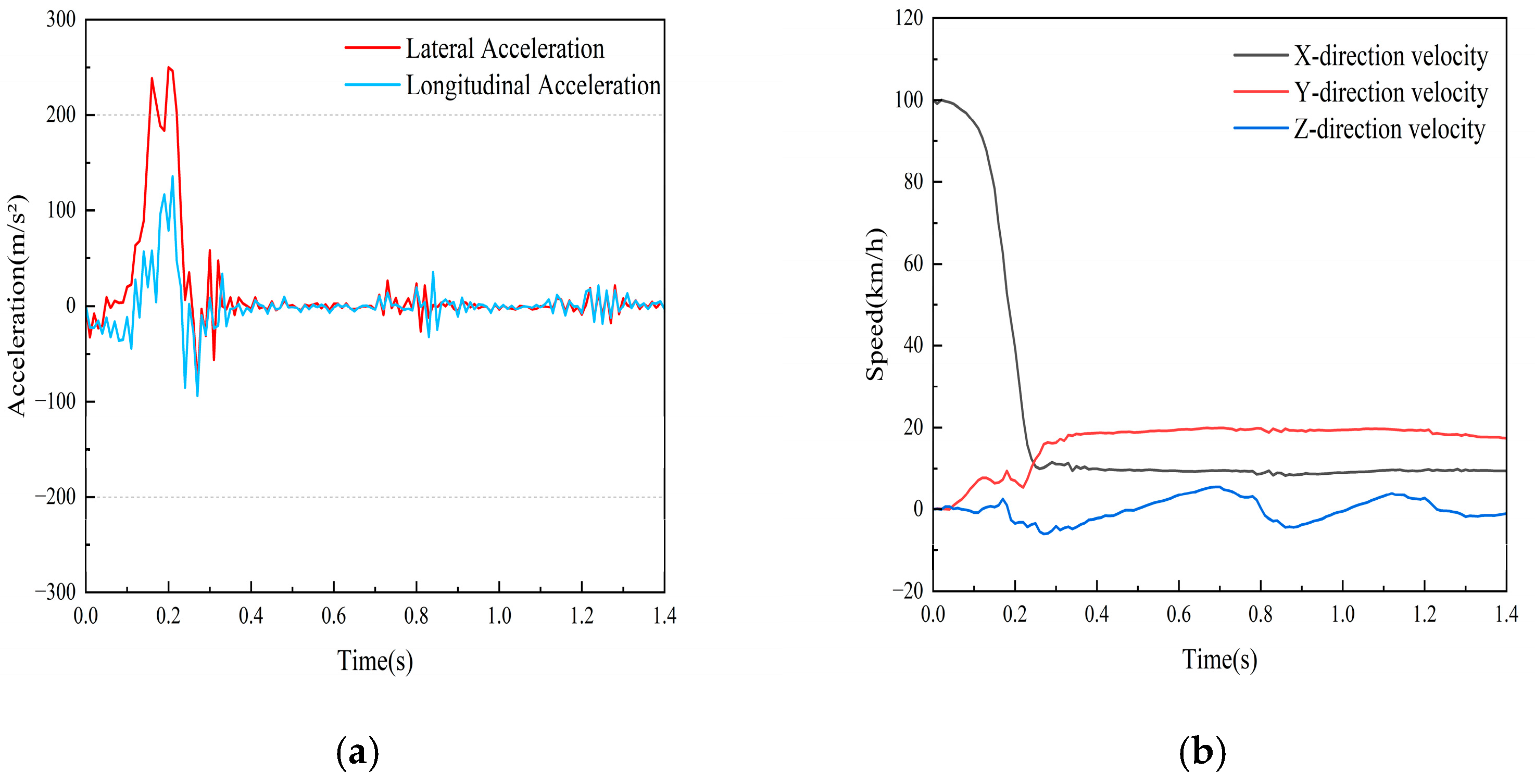

5.2. Analysis of Medium Truck Crash

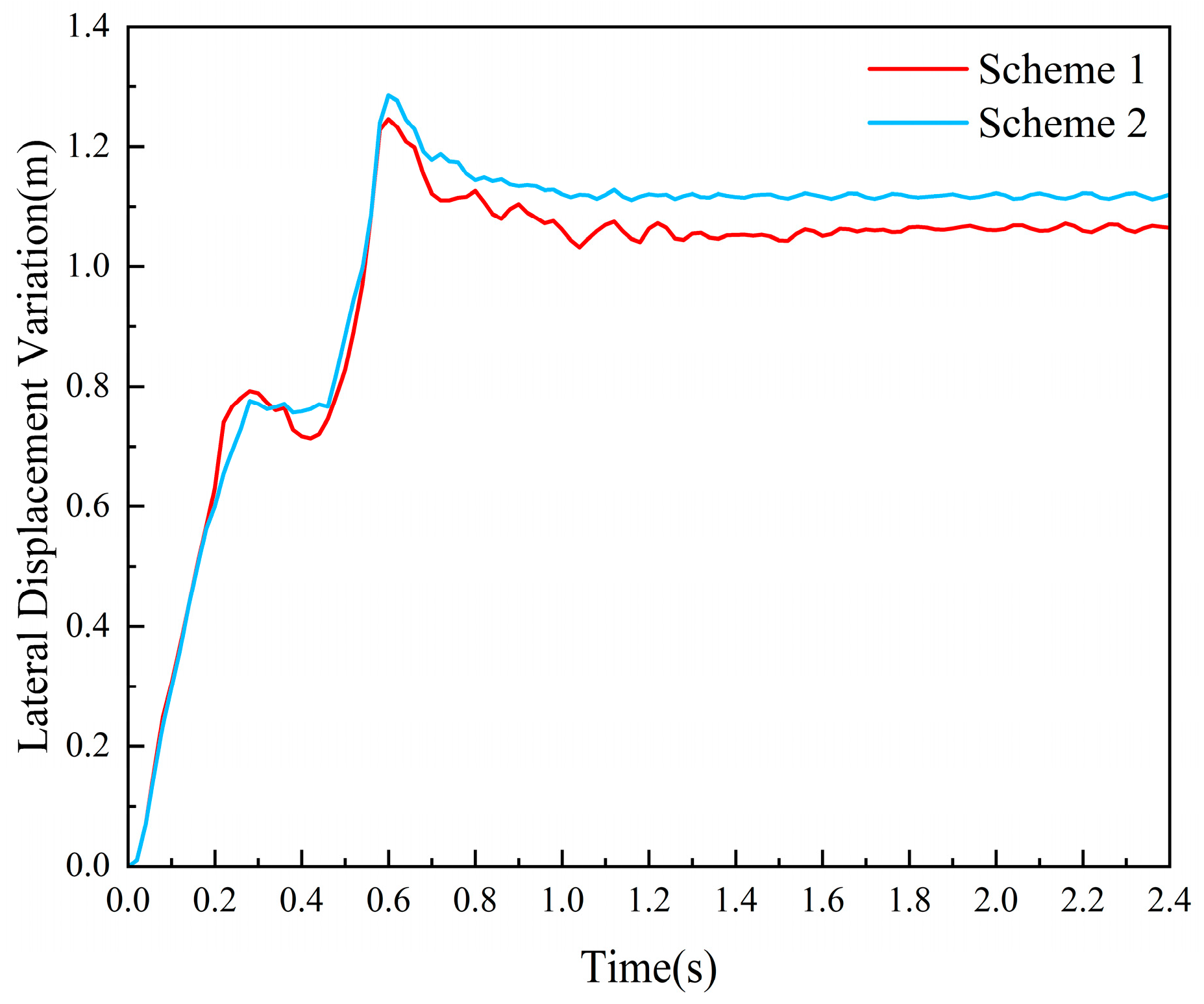

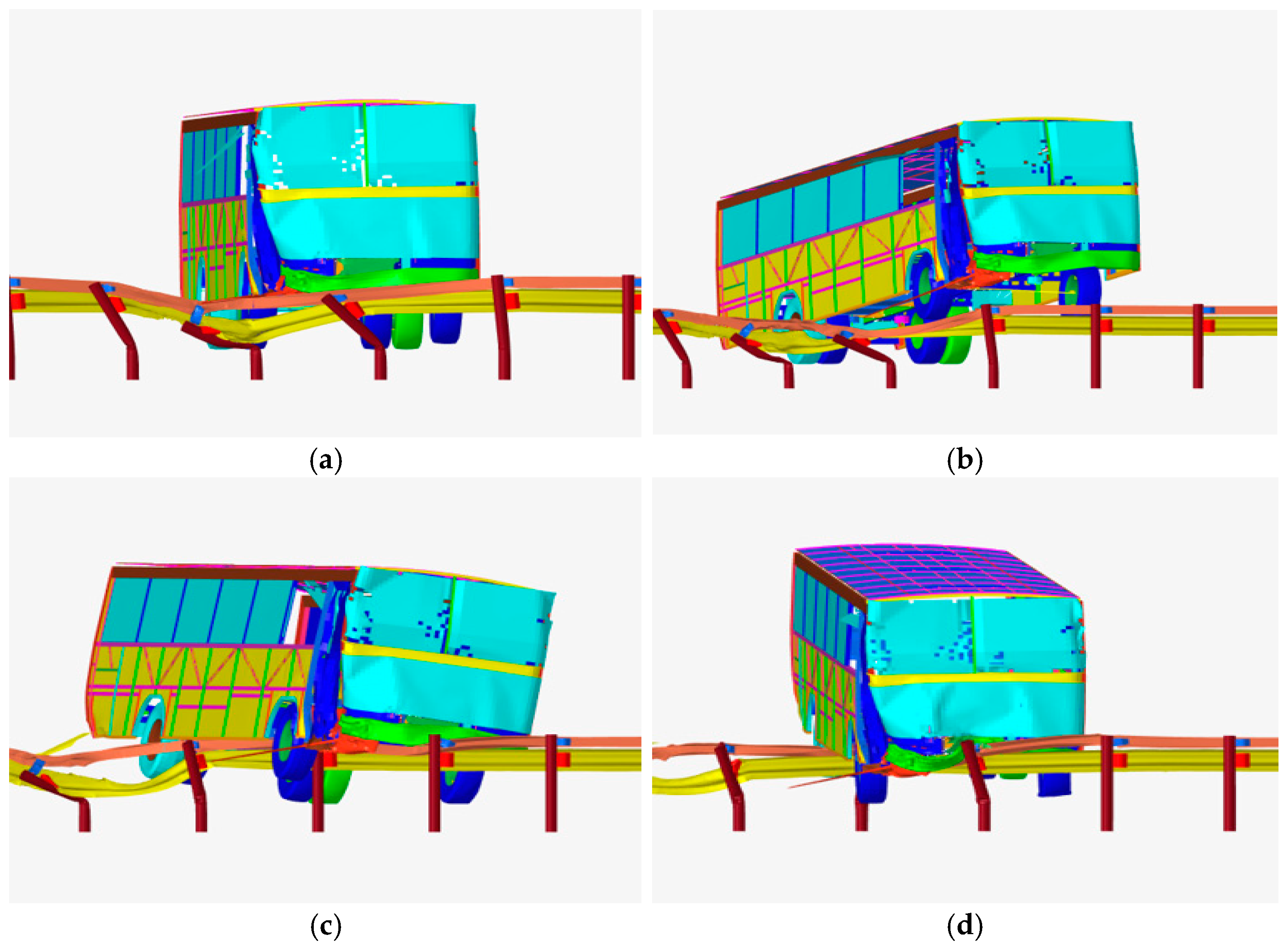

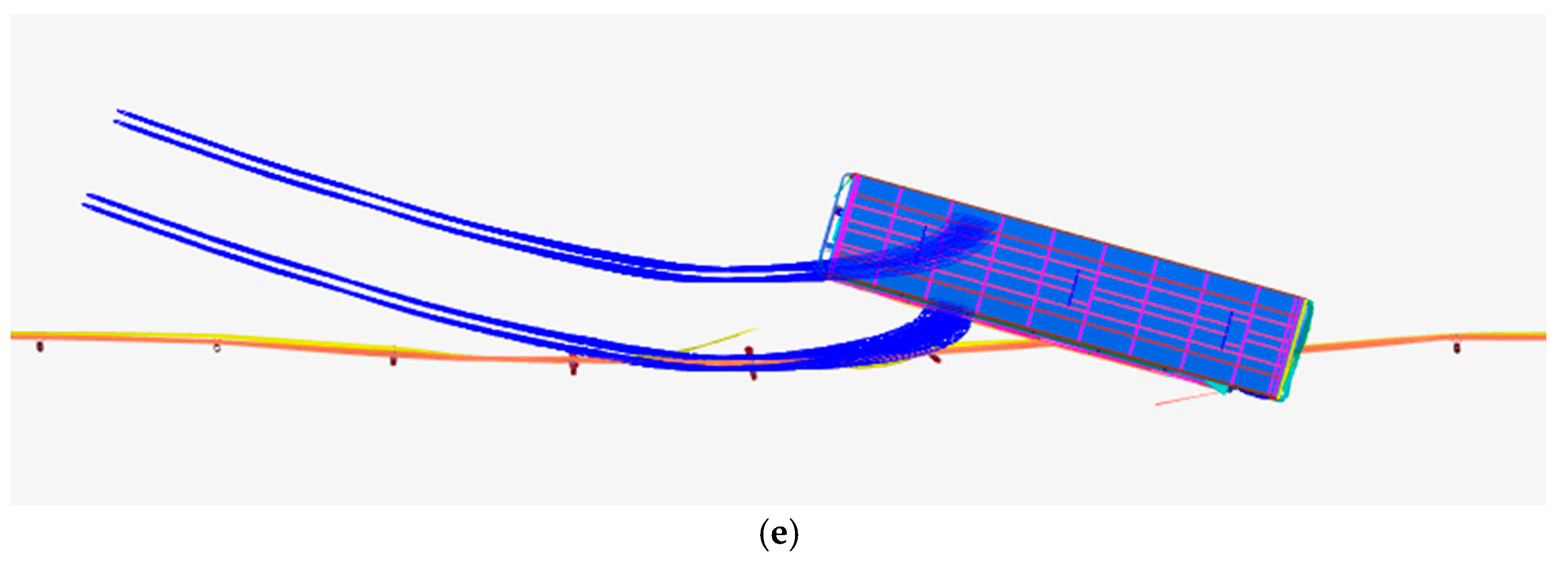

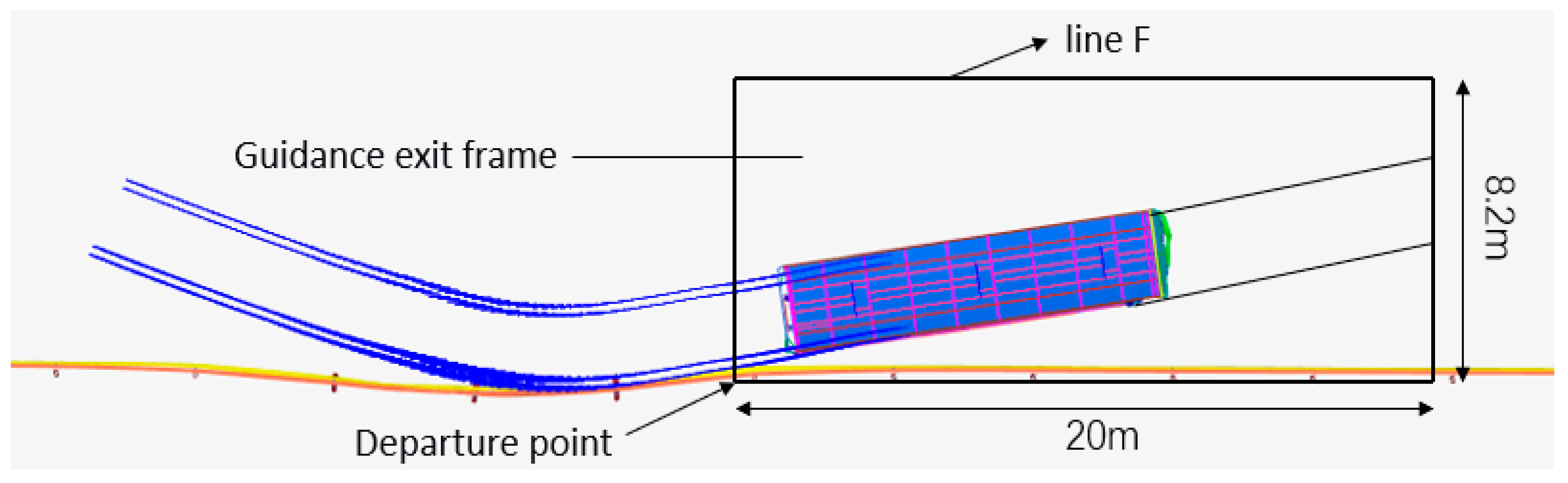

5.3. Analysis of Medium Bus Crash

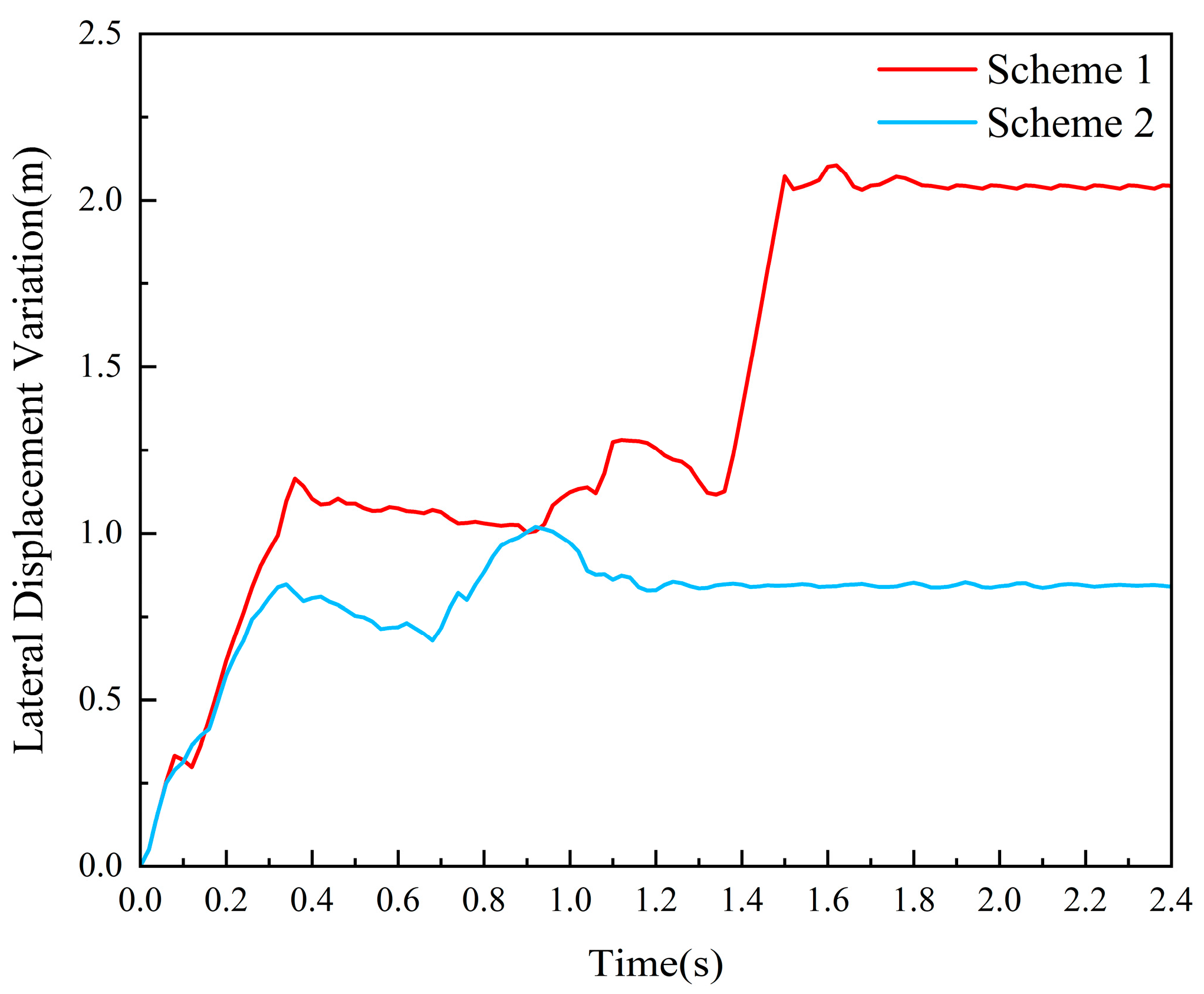

5.4. Analysis of Simulation Results

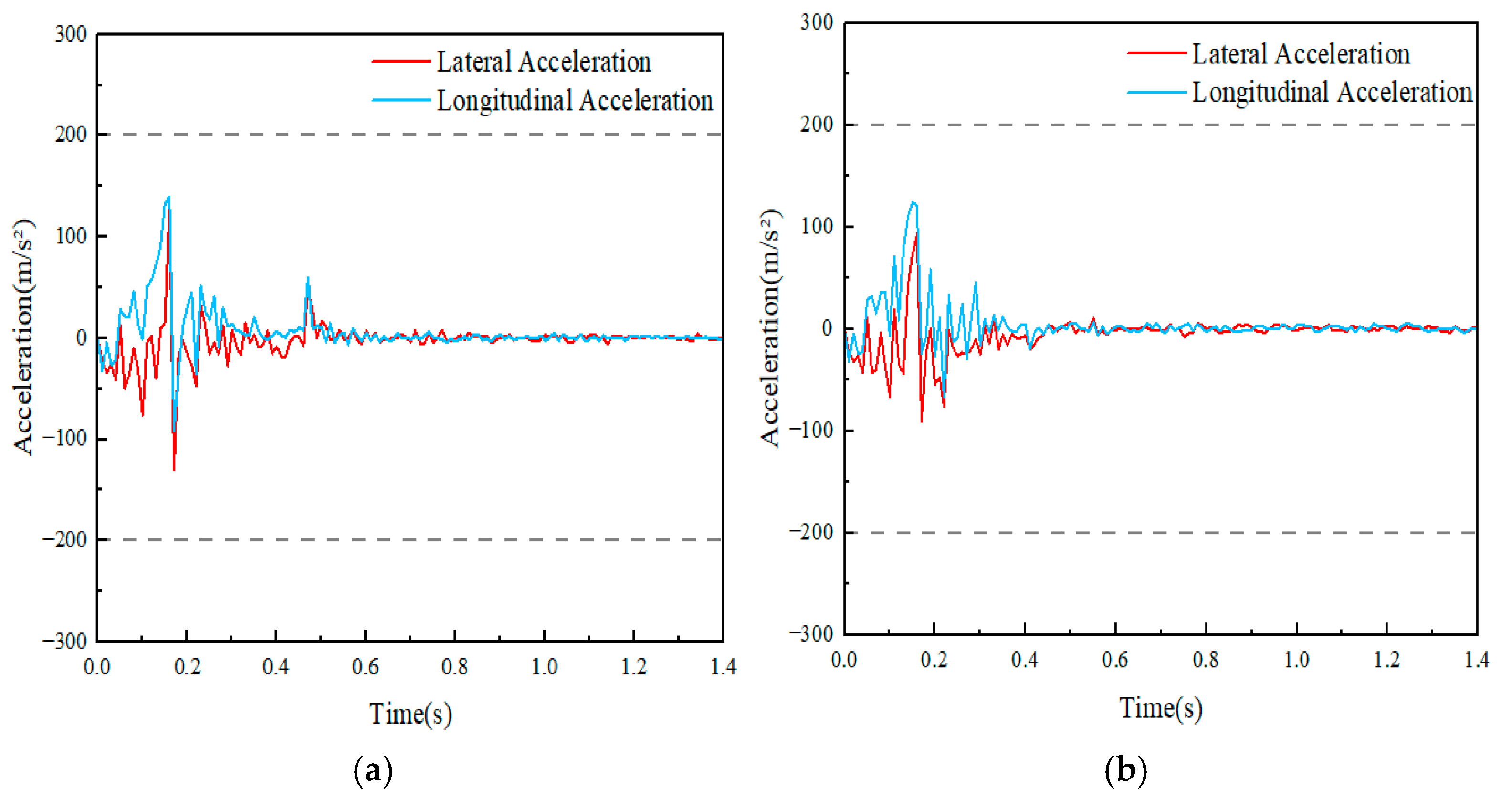

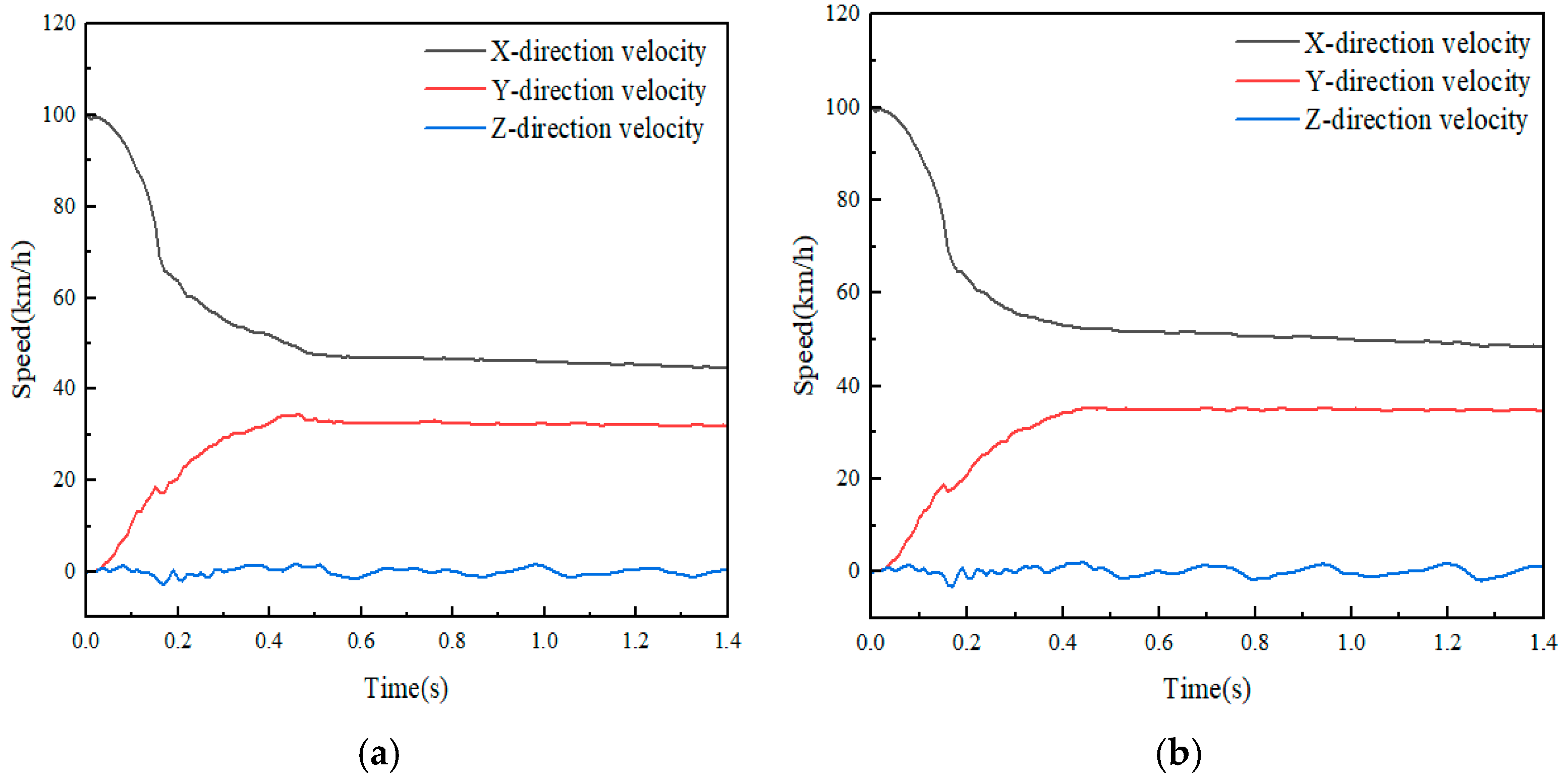

5.5. Analysis of Collision Between Small Passenger Cars and Class A W-Beam Guardrail

5.6. Occupant Risk Assessment

5.7. Guardrail Manufacturing Cost Comparison

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Comprehensive Results Based on Finite Element Simulation

- (2)

- Through comprehensive analysis of small passenger car collision posture, bumper structural characteristics, and guardrail restraint mechanisms, this study systematically revealed the root cause of the “underride” phenomenon: the installation height of the front bumper on some small passenger cars is lower than the lower edge height of the wave beams in existing Class A triple W-beam guardrails, preventing effective initial contact between the vehicle and the beams and allowing intrusion beneath them. Based on this mechanism, this paper proposes a combined protective structure consisting of a double W-beam and a C-type beam. While maintaining the total guardrail height, the double W-beam installation height was adjusted to 560 mm, and a C-type beam with a central height of 850 mm was added, creating a more rational protective gradient. This design significantly reduces the probability of small passenger car underride.

- (3)

- The synergistic optimization of materials and structure significantly enhances the safety performance of the guardrail. A comparative analysis of two schemes using Q235 carbon steel and Q355 high-strength low-alloy steel was conducted based on finite element simulation. The simulation results demonstrate that the structurally optimized scheme employing Q355 steel exhibits superior safety performance. This scheme shows improved cushioning characteristics in small passenger car collisions and also demonstrates stronger impact resistance and blocking capability in medium truck and bus scenarios. Key evaluation metrics for all three tested vehicle types meet the requirements of the “Standard for Safety Performance Evaluation of Highway Barriers,” verifying the reliability of this structural scheme.

- (4)

- The structural and material optimization delivers substantial economic benefits. Compared to the existing triple W-beam guardrail, the proposed guardrail scheme achieves significant economic advantages while meeting protective performance requirements. The combined structure reduces mass by approximately 1.4 tons per kilometer, with material costs reduced by about 10,000 RMB per kilometer.

- (5)

- Quantitative risk assessment verifies that structural optimization significantly reduces occupant injury. Based on the accident severity evaluation systems of EN 1317 and MASH, this study calculated three occupant injury indicators: ASI, THIV, and PHD. The results indicate that when a small passenger car collides with the original Class A triple W-beam guardrail, all three indicators exceed the corresponding acceptable thresholds, suggesting a high risk of occupant injury. After implementing Scheme 2, the ASI value decreased by approximately 36.7%, THIV by approximately 22.1%, and PHD by approximately 44.5%. Among these, THIV and PHD met the safety ranges recommended by EN 1317 (THIV ≤ 33 km/h, PHD ≤ 20 g), and the ASI rating was reduced from Class C to Class B. This demonstrates that the guardrail structural scheme adopted in this study can more effectively distribute impact loads and improve energy absorption efficiency, significantly reducing the injury severity in roadside accidents.

- (6)

- The findings of this study provide important practical implications for the design of road safety facilities. On one hand, the research reveals that the key issue with guardrails is not the conventionally perceived lack of material strength, but rather the “geometric mismatch” between vehicle bumper height and guardrail beam height. Therefore, future guardrail design should place greater emphasis on the coordinated matching of structural height to effectively reduce the underride risk for small vehicles. On the other hand, the study confirms that replacing part of the Q235 steel with Q355 high-strength steel is a feasible approach to achieve guardrail lightweighting and enhance safety performance, reducing material usage and overall mass while ensuring protective capacity. Furthermore, the combined structure of double W-beams and a C-type beam demonstrates superior protective potential compared to traditional single W-beams in terms of guidance continuity, energy transfer stability, and vehicle posture control. Overall, the structural and material optimization strategies proposed in this study not only provide a reference for improving existing guardrail systems but also offer forward-looking technical foundations for the future revision of Chinese guardrail design standards, beam height optimization, promotion of high-strength steel applications in guardrails, and the development of lightweight guardrail technologies.

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- JTG/T D81-2017; Detailed Specification for Design of Highway Safety Facilities. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 64–66.

- Hou, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.C. Research on Improving the Crashworthiness of Expressway W-Beam Guardrail. Shanxi Archit. 2023, 49, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 31439.2-2015; Guardrail—Part 2: Corrugated Sheet Steel Thrie-Beams for Road Guardrail. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Eerdunsongbuer; Meng, G.J.; Hou, G.H. Application Research of Green New Materials in Highway Guardrails of Inner Mongolia. Transp. Constr. Managno. 2023, 6, 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- Borovinšek, M.; Vesenjak, M.; Ulbin, M.; Ren, Z. Simulation of Crash Tests for High Containment Levels of Road Safety Barriers. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2007, 14, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.D.; Sicking, D.L.; Faller, R.K.; Pfeifer, B.G. Development of a New Guardrail System. Transp. Res. Rec. 1997, 1599, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Ahn, J.S.; Woo, K.S. Vehicle Impact Analysis of Flexible Barriers Supported by Different Shaped Posts in Sloping Ground. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2014, 6, 705629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzougui, D.; Mohan, P.; Kan, S.; Opiela, K. Evaluation of Rail Height Effects on the Safety Performance of W-Beam Barriers. In Proceedings of the 6th European LSDYNA User’s Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden, 28–30 May 2007; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sicking, D.L.; Reid, J.D.; Rohde, J.R. Development of the mid-west guardrail system. Transp. Res. Rec. 2002, 1797, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesenjak, M.; Ren, Z. Improving the roadside safety with computational simulations. In Proceedings of the 4th European LS-DYNA Users Conference, Ulm, Germany, 22–23 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.P. Optimization Research on Median W-Beam Guardrail to Prevent Vehicle Cross-Over. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahi Pajouh, M.; Julin, R.D.; Stolle, C.S.; Reid, J.D.; Faller, R.K. Rail height effects on safety performance of Midwest Guardrail System. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2017, 19, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Cui, S.; Xing, X.; Liang, G. Study on the Influence of Guardrail Height Variation on Crashworthiness. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2015, 34, 84–86. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.Y. Multi-objective Robust Optimization Design of a New Type of W-Beam Guardrail. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Z. Crash Simulation Research and Optimization of Expressway W-Beam Guardrail. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.C.; Ma, Y.T.; Liu, Z.L.; Yan, S.M. Research on a New Grade-A W-Beam Guardrail Structure. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. (Appl. Technol. Ed.) 2015, 11, 235–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.L.; Wei, Y.K.; Pan, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Peng, D.M.; Gao, C.L. Redesign and Safety Study of W-Beam Guardrail Based on Finite Element and Full-Scale Vehicle Impact Test. Highway 2025, 70, 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.J. Application Analysis of Lightweight W-Beam Guardrail Using High-Strength Steel. North Commun. 2021, NA, 66–68, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, J.; Li, G. Simulation and Redesign of a New W-Beam Guardrail Structure for Highways. J. Guizhou Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 41, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.H.; Chen, Z.Q.; Cao, H.B.; Li, J. Material Selection and Structural Design of Lightweight Highway Guardrail. J. Fujian Univ. Technol. 2024, 22, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1317-2: 2010; Road Restraint Systems—Part 2: Performance Classes, Impact Test Acceptance Criteria and Test Methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- EN 1317-1: 2010; Road Restraint Systems—Part 1: Terminology and General Criteria for Test Methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Manual for Assessing Safety Hardware (MASH); American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO): Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F.K. Correlation Analysis of Occupant Risk Evaluation Indicators Based on Vehicle-Guardrail Collision. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2016, 33, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.J.; Li, Y.; Lei, Z.B.; Zheng, J.L. Highway Roadside Hazard Assessment Based on Acceleration Severity Index. China J. Highw. Transp. 2013, 26, 8. [Google Scholar]

- GB 17354-1998; Front and Rear Protective Devices for Motor Vehicles. State Administration for Quality and Technical Supervision: Beijing, China, 1998.

- Jing, D.F.; Kang, K.X.; Song, C.C. Research on Heightening and Reconstruction Schemes for W-Beam Guardrail. Highw. Eng. 2021, 46, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Thomson, R. A Study of the Interaction between a Guardrail Post and Soil during Quasi-Static and Dynamic Loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2007, 34, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.S. Design and Protective Performance Research of a Land-Saving SBm-Level Guardrail Based on Finite Element Simulation. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- JTG B05-01-2013; Standard for Safety Performance Evaluation of Highway Barriers. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 10–31.

- Xiong, G. Finite Element Simulation of Vehicle Collision with Semi-Rigid Guardrail Based on LS-DYNA. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.T.; Li, H.; Yu, W. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Domestic Q355 Steel after High-Temperature Cooling. Steel Constr. (Chin. Engl.) 2023, 38, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Road Association. Setting Standards and Instructions for Guardrail; Japan Road Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, H.E., Jr.; Sicking, D.; Zimmer, R.A.; Michie, J.D. Recommended Procedures for the Safety Performance Evaluation of Highway Features, NCHRP Report 350; Transportation Research Board, National Research Council: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sicking, D. Manual for Assessing Safety Hardware; America Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Guardrail Beam Type (mm) | Column (mm) | Anti-Obstruction Block (mm) | Beam Installation Height (mm) | Column Depth (mm) | Total Guardrail Height (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-wave beam (310 × 85 × 3) | Φ140 × 4 | 196 × 178 × 200 × 4 | 560 | 1400 | 2350 |

| C-type beam (140 × 100 × 3) | 196 × 178 × 100 × 4 | 850 |

| Guardrail Components | Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Thickness | Material | Thickness | |

| Double-wave beam | Q235 | 3 | Q235 | 3 |

| C-type beam | Q235 | 3 | Q355 | 2.5 |

| Column | Q235 | 4 | Q235 | 4 |

| Anti-obstruction block 1 | Q235 | 4 | Q235 | 3.5 |

| Anti-obstruction block 2 | Q235 | 4 | Q235 | 4 |

| Crash Vehicle Type | Vehicle Weight (t) | Length × Width × Height (m) | Center of Gravity Height (m) | Impact Velocity (km/h) | Impact Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small passenger car | 1.5 | 4.6 × 1.8 × 1.4 | 0.52 | 100 | 20 |

| Medium passenger bus | 10 | 11.2 × 2.5 × 3 | 1.36 | 60 | 20 |

| Medium truck | 10 | 8.6 × 2.5 × 3.3 | 1.41 | 60 | 20 |

| Collision Vehicle Type | A | B |

|---|---|---|

| small passenger car | 2.2 + Vw + 0.16 Vl | 10 |

| Large and medium buses (including extra-large buses) Large and medium trucks | 4.4 + Vw + 0.16 Vl | 20 |

| Value Range | Injury Level | Assessment Description |

|---|---|---|

| ASI ≤ 1.0 | A | Good—favorable to occupant safety, low injury risk |

| 1.0 < ASI ≤ 1.4 | B | Acceptable—acceptable level, no serious injury risk |

| ASI > 1.4 | C | Severe—poses a high injury risk, does not meet safety requirements |

| THIV Threshold | Description |

|---|---|

| THIV ≤ 33 km/h | Good—low risk of occupant head impact |

| THIV > 33 km/h | High risk—may result in head injury |

| Measurement | Small Passenger Car | |

|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 | |

| Whether it passes through the guidance exit frame normally | yes | yes |

| Lateral acceleration at the center of gravity (m/s2) | 132.36 | 93.08 |

| Longitudinal acceleration at the center of gravity(m/s2) | 139.89 | 124.56 |

| Lateral occupant impact velocity(m/s) | 5.08 | 2.15 |

| Longitudinal occupant impact velocity(m/s) | 9.44 | 7.79 |

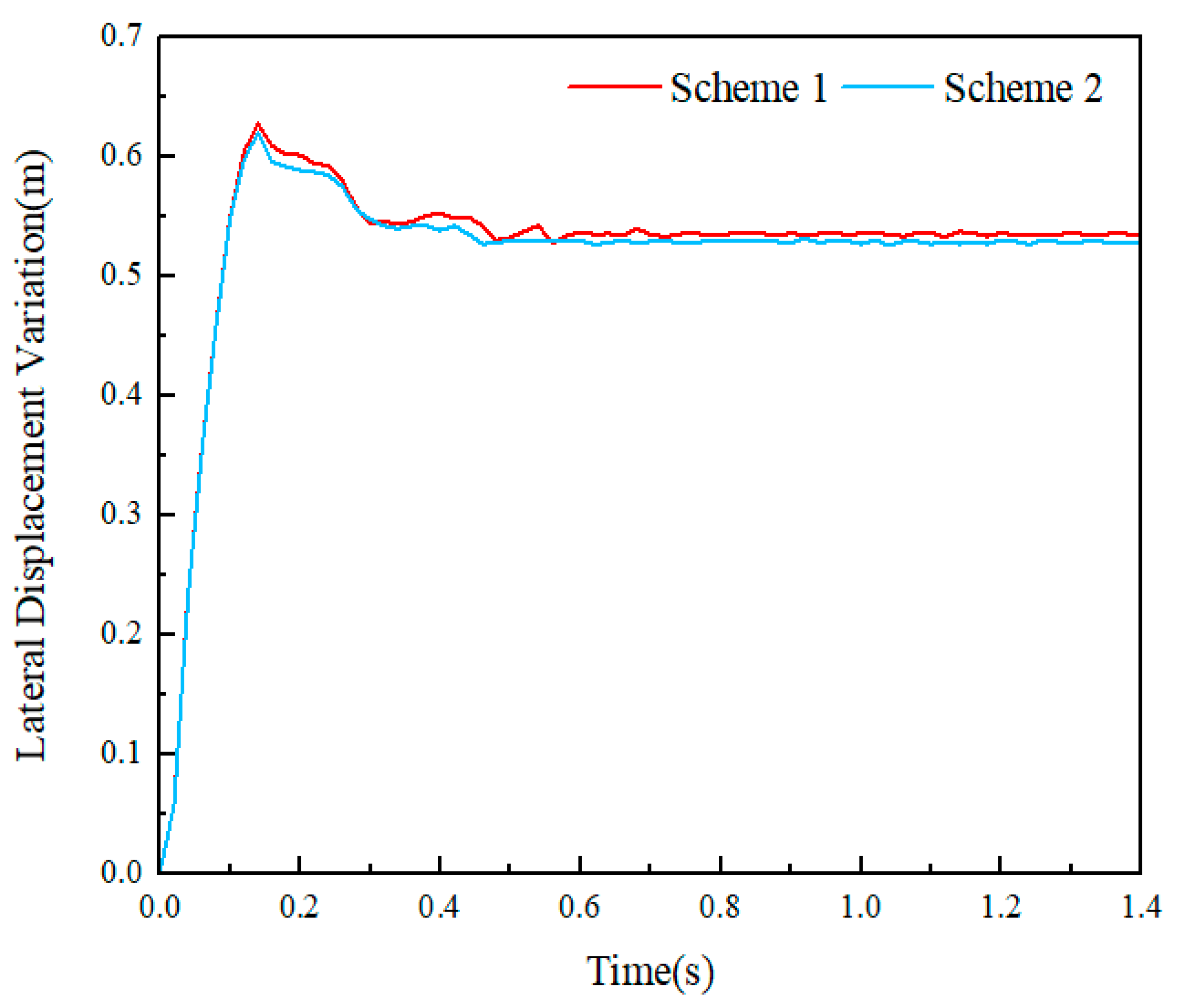

| Maximum lateral dynamic deformation of the guardrail (m) | 0.627 | 0.62 |

| Maximum lateral dynamic displacement extension of the guardrail (m) | 0.913 | 0.869 |

| Measurement | Medium Truck | Medium Bus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 | Scheme 1 | Scheme 2 | |

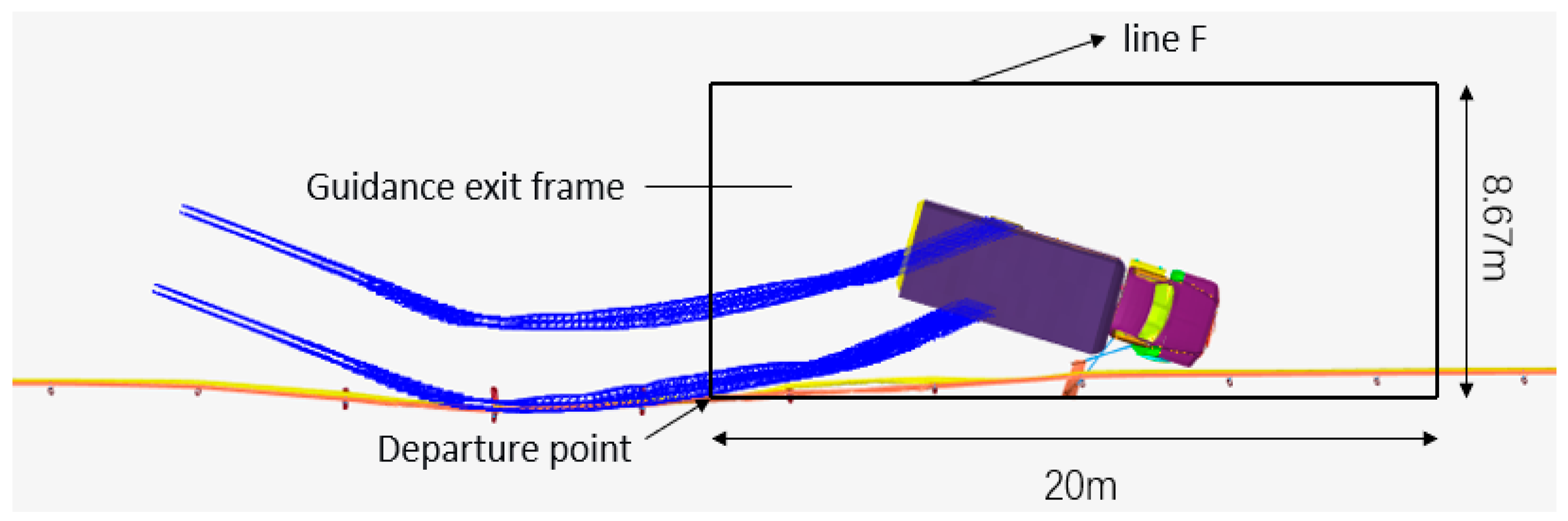

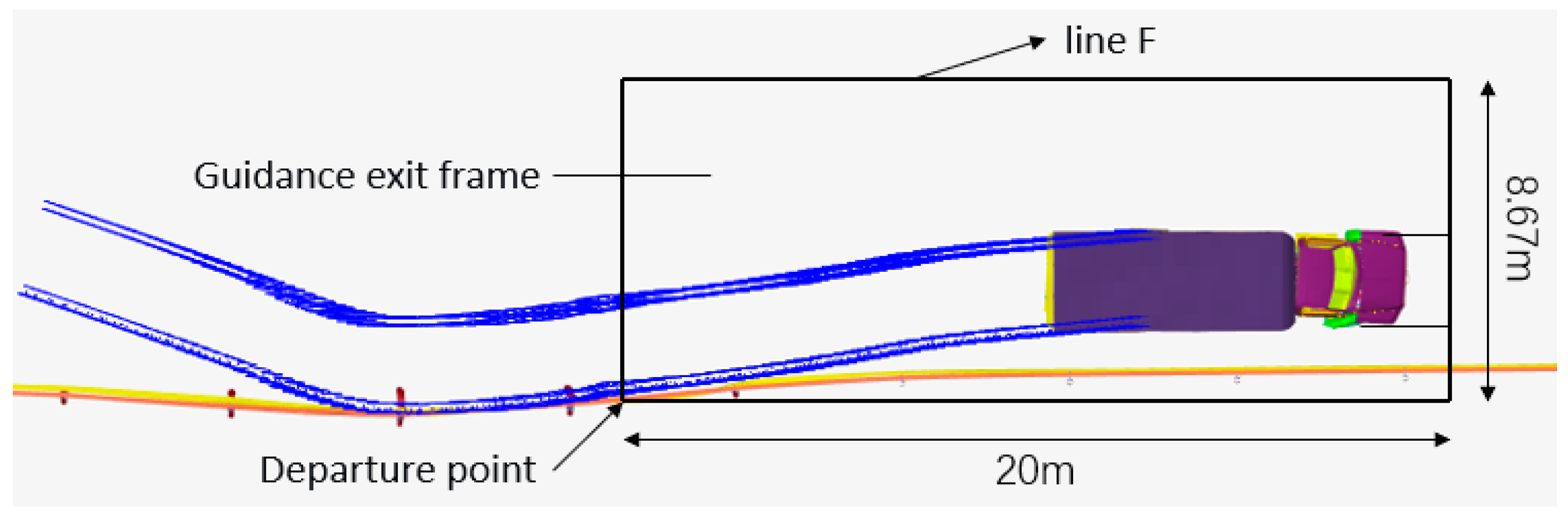

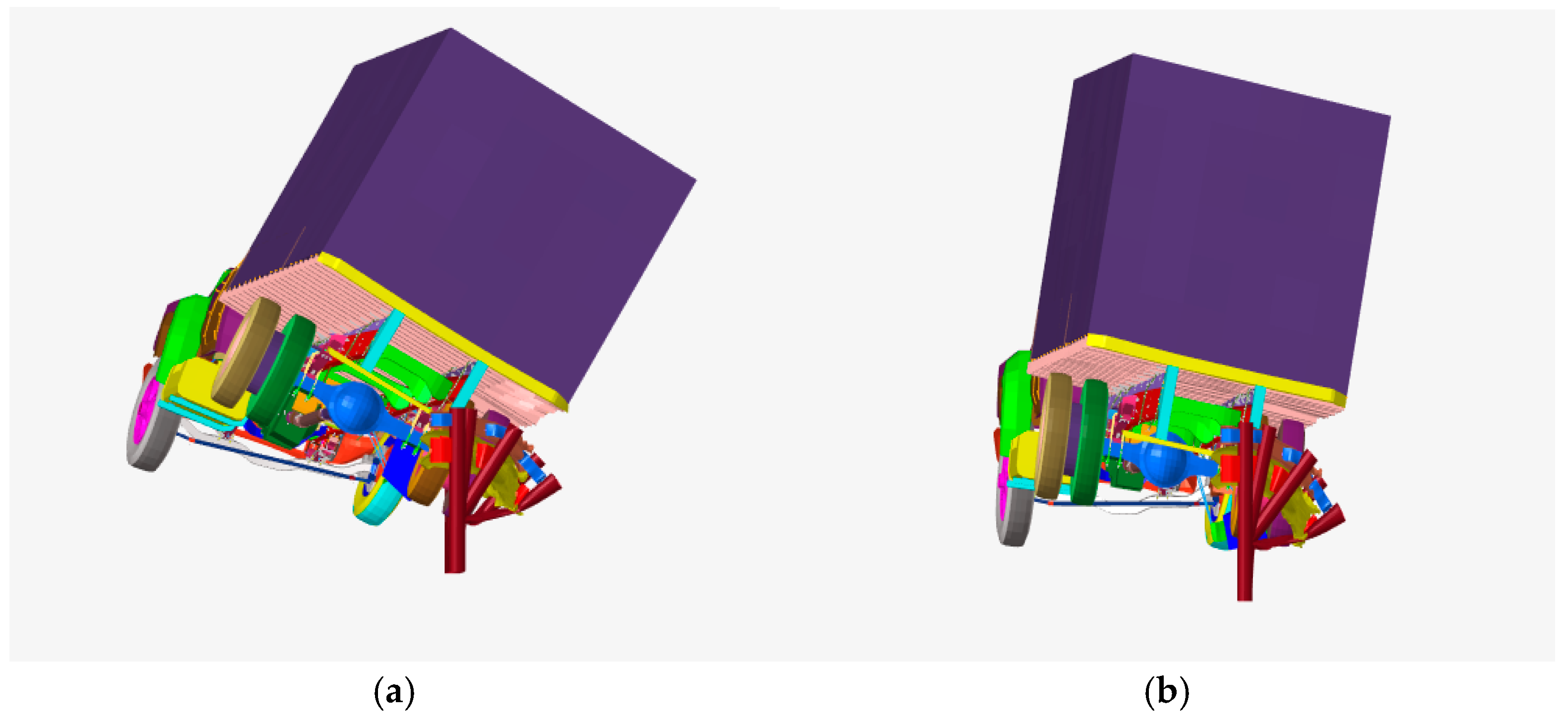

| Whether it passes through the guidance exit frame normally | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Maximum lateral dynamic deformation of the guardrail (m) | 1.246 | 1.285 | 1.019 | |

| Maximum lateral dynamic displacement extension of the guardrail (m) | 1.325 | 1.367 | 1.162 | |

| Maximum dynamic vaulting of the vehicle (m) | 2.103 | 1.642 | 1.412 | |

| Maximum dynamic vaulting equivalent of the vehicle (m) | 2.498 | 1.788 | 1.446 | |

| Occupant Risk Assessment Indicators | Triple-Wave Beam Guardrail | Scheme 2 |

|---|---|---|

| ASI | 2.07 | 1.31 |

| THIV | 35.3 km/h | 27.5 km/h |

| PHD | 28.1 g | 15.6 g |

| Guardrail Structural Type | W-Beam | C-type Beam | Anti-obstruction Block | Column | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 2 | 12,290 | 7143.5 | 1426.5 | 7187 | 28,047 |

| triple-wave beam guardrail | 19,125 | 2233.3 | 8085 | 29,443.3 |

| Category of Indicators | triple-Wave Beam Guardrail | Scheme 2 | Improvement Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASI | 2.07 (Class C) | 1.31 (Class B) | Decreased by 36.7% |

| THIV | 35.3 km/h | 27.5 km/h | Decreased by 22.1% |

| PHD | 28.1 g | 15.6 g | Decreased by 44.5% |

| Key Structural Deformation/Guidance | Pronounced underride/Vehicle instability | Effectively suppresses underride/Vehicle stability | |

| Weight per Kilometer (kg) | 29,443.3 | 28,047 | Decreased by about 1.4 tons |

| Material Cost per Kilometer (RMB) | 117,772 | 107,690 | Decreased by about 10,000 RMB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, X.; Hu, J.; Hu, Q. Research on Anti-Underride Design of Height-Optimized Class A W-Beam Guardrail. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12631. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312631

Feng X, Hu J, Hu Q. Research on Anti-Underride Design of Height-Optimized Class A W-Beam Guardrail. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12631. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312631

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Xitai, Jiangbi Hu, and Qingxin Hu. 2025. "Research on Anti-Underride Design of Height-Optimized Class A W-Beam Guardrail" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12631. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312631

APA StyleFeng, X., Hu, J., & Hu, Q. (2025). Research on Anti-Underride Design of Height-Optimized Class A W-Beam Guardrail. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12631. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312631