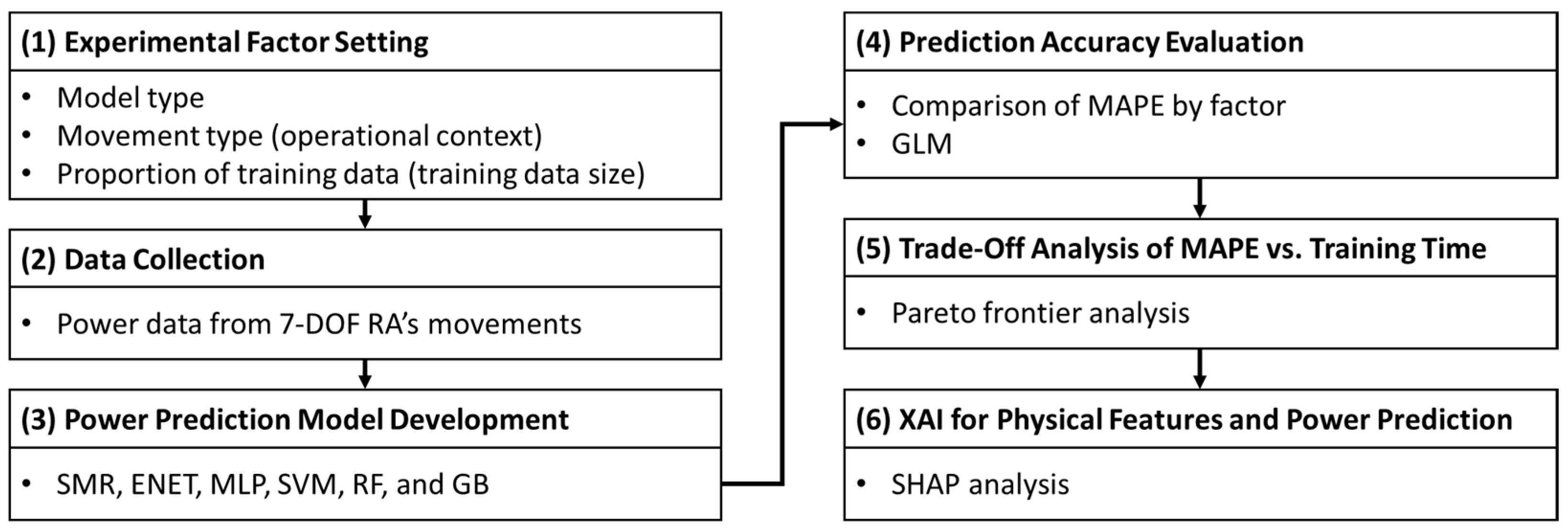

This section presents the results of a multi-stage analysis for RA power prediction model evaluation, from a broad performance overview to a deep XAI investigation. First, we begin with a foundational analysis of predictive accuracy in

Section 4.1. Here, we examine the influence of our three key factors (i.e., model type, movement type, and proportion of training data) to provide a general overview of predictive performance. Building on this finding,

Section 4.2 introduces the practical constraint of training time, employing Pareto frontier analysis to identify models that are both accurate and fast to train. Finally, in

Section 4.3, we conduct XAI analysis to explain how the predictions of best and worst performing models are linked to the RA’s physical dynamics.

4.1. Prediction Accuracy Evaluation

We make 162 power prediction models for each factor and level (6 model types × 3 movement types × 9 proportions of training data) and train each model with the collected data.

Table 8 lists the top ten models with the best predictive performance (i.e., the models with the lowest MAPE). In this table, only three of the six model types—ENET, SVM, and SMR—appear. Among the top ten ranks, three (first, eighth, and tenth) are from 3D movement, while the others are from 2D movement. Furthermore, predicting performance tends to show good results with a 40% or higher proportion of training data.

MAPE by model type is summarized with descriptive statistics in

Table 9 and the boxplot in

Figure 3. The ranking of model types by mean MAPE, from lowest to highest, is RF, SMR, GB, SVM, ENET, and MLP. In particular, MLP performs significantly worse compared to the other model types.

We perform a Wilcoxon rank-sum test to check whether there is a significant difference in performance between the model types themselves, without distinguishing the factors of movement type and the proportion of training data. In the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, a

p-value smaller than 0.05 indicates that there is a significant difference between the data values of the two groups [

70]. As shown in

Table 10, except for the MLP, all other model types do not show a significant difference in prediction performance. This result statistically confirms that MLP performs significantly worse than the other model types. Furthermore, this finding indicates that most model types, except MLP, can compete at a similar level of predictive performance, implying that other criteria need to be considered for selecting a better power prediction model.

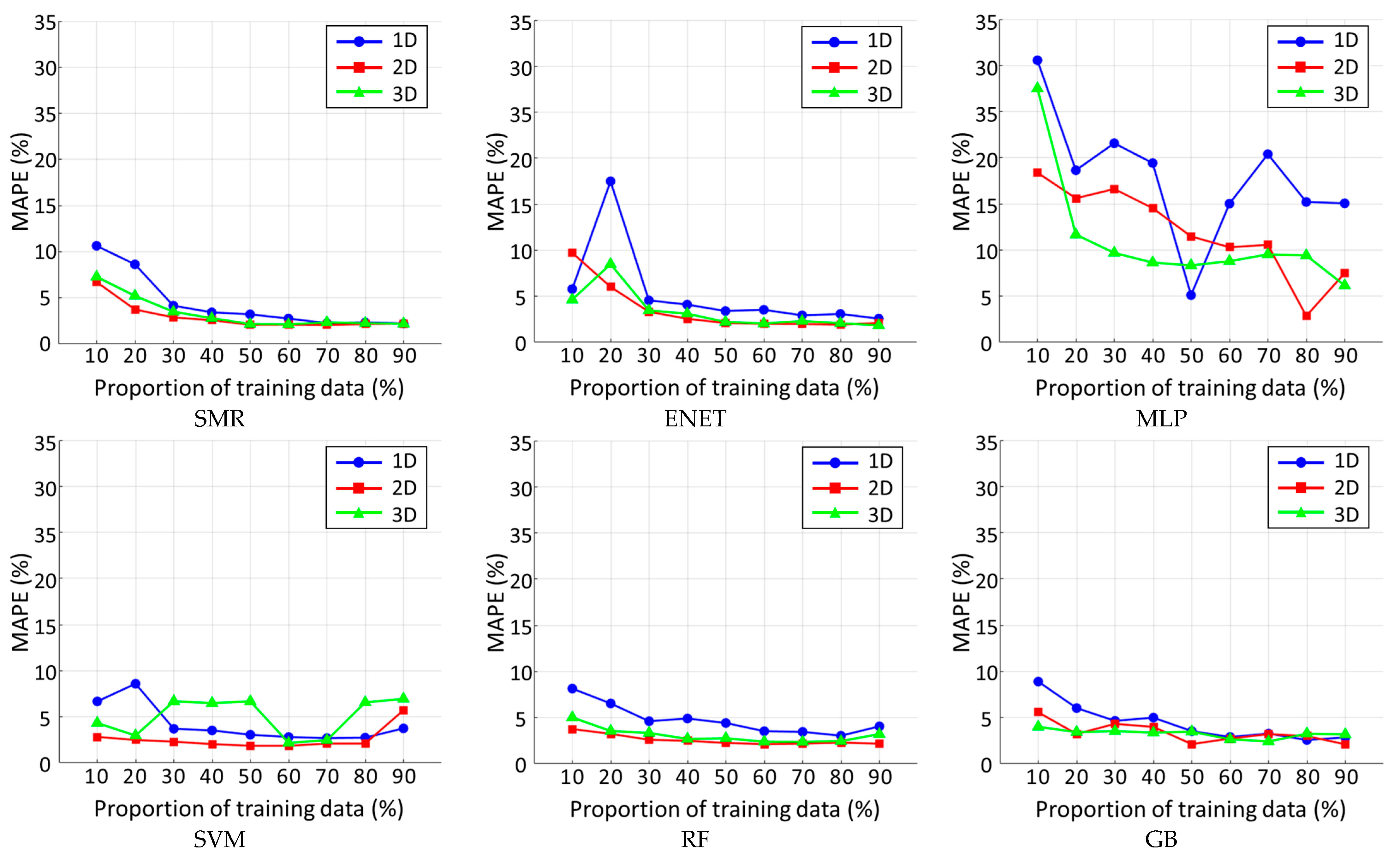

Figure 4 shows charts of MAPE for each movement type and the proportion of training data, categorized by six model types. In most cases, a higher proportion of training data tends to lead to improved prediction performance. However, in certain cases (e.g., 1D movement of SVM, RF, and GB, 2D movement of ENET, MLP, and SVM, and 3D movement of SVM and RF), MAPE increases when the proportion of training data reaches 90%. This phenomenon provides the insight that an increase in the amount of training data does not necessarily lead to improved prediction performance. Moreover, the variation in MAPE by various proportions of training data can serve as a basis for optimizing the cost and effort of data collection in practical applications. In addition, six model types show a common trend; MAPE for 1D movement is typically higher than those for 2D and 3D movements.

To statistically validate these findings and understand their underlying causes, we perform an ANOVA and a GLM analysis. The ANOVA results, summarized in

Table 11, confirm that the model type, movement type, and proportion of training data all have a statistically significant effect on MAPE (

p-value = 0.000).

In addition, the GLM estimation results provide a more detailed confirmation of our initial observations (

Table 12). For model types, there is no statistically significant difference in performance between SVM and all other model types, except for MLP. The large, positive, and highly significant coefficient for MLP (coefficient = 9.716 and

p-value = 0.000) indicates poorer performance compared to other model types. In other words, relative to SVM, MLP increases expected MAPE by about 9.716 percentage points. Similarly, 1D movement is significantly more challenging to predict (coefficient = 1.959,

p-value = 0.000), increasing expected MAPE (i.e., prediction error) by about 1.959 percentage points relative to the 3D movement. Conversely, there is no significant performance difference between 2D and 3D movements (

p-value = 0.486). Moreover, for the proportion of training data, the GLM analysis reveals that using small datasets (10% to 30%) significantly increases prediction error. However, the other levels (40% to 80%) show no statistically significant difference in MAPE compared to 90%.

To investigate why the power of 1D movement is more difficult to predict, we compare the variance of the power demand data across movement types using the F-test (

Table 13). The test reveals that the data from 1D movements has significantly larger variance than that from 2D and 3D movements (

p-value = 0.000).

The findings from MAPE comparison and GLM provide a foundational, high-level performance evaluation across all experimental factors, yielding three key insights. First, while the MLP shows the poorest performance at a statistically significant level, the other five model types are not distinguishable based on predictive accuracy alone. This finding underscores that accuracy alone is an insufficient metric for power prediction model selection, necessitating the multi-criteria evaluation. Second, the analyses identify a distinct performance pattern among the movement types. One-dimensional movements yield higher prediction errors compared to both 2D and 3D movements. This finding is explained by the data’s inherent statistical properties, as our analysis shows that the power data from 1D movements exhibit significantly higher variance. Finally, in our dataset, a minimum of 40% training data is sufficient to prevent a significant accuracy drop. However, this finding is limited to our experimental data and should be considered an example. Taken together, the results show that accuracy alone is not a sufficient criterion to choose an RA power prediction model. Thus, in the following subsections, we compare RA power prediction models by incorporating one additional criterion: training time. More specifically, we select the best model that is both accurate and fast to train. Then, we explain the physical reasons behind the power prediction model’s performance. Especially to provide more actionable and context-specific guidance for shop-floor engineers, our subsequent analyses are conducted for each movement type separately.

4.2. Pareto Frontier: Trade-Off Analysis of MAPE vs. Training Time

Alongside the prediction performance of the models, the time required for training is also an important aspect for selecting an appropriate model. Thus, we utilize the Pareto frontier to visualize the trade-off relationship between the performance and training time of RA power prediction models. Specifically, the Pareto frontier is constructed individually for each movement type. Additionally, since the data points are concentrated near zero and therefore difficult to distinguish, we apply a logarithmic scale to the X-axis of the Pareto frontier (training time).

Figure 5a–c display MAPE versus training time for all 54 RA power prediction models for 1D, 2D, and 3D movement, respectively. Each prediction model is displayed with a different marker according to model type, and the Pareto frontier is drawn as a black, solid line.

For 1D movement, the model types of the prediction models on the Pareto frontier are SVM and SMR. In the case of 2D movement, SVM is the only model type found on the Pareto frontier. For 3D movement, the model types on the Pareto frontier are SVM, SMR, and ENET. Overall, power prediction models developed based on the SVM model type consistently appear on the Pareto frontier for all three movement types.

Table 14 presents the comparison factors (movement type, model type, and proportion of training data) corresponding to each point on the Pareto frontier.

Among models on three Pareto frontiers, SVM with a proportion of training data at 60% appears across all three movements. This result indicates that for our specific dataset, using about 60% of the data is sufficient to achieve both low prediction error and short training time. Increasing the training data beyond 60% does not necessarily improve accuracy, while it substantially increases training time. The required minimum number of training data also reflects the absolute number of observations. For 1D and 3D movements, the total sample sizes are smaller than 2D (510 and 590, respectively), and so prediction models with up to 90% training data appear on the Pareto frontier. In contrast, 2D has the largest sample size (1000), and the Pareto frontier includes models with at most 70% training data. This suggests that the trade-off between the power prediction model’s performance and training time is highly influenced by the amount of training data.

All of the most inefficient models (i.e., models located in the upper-right region of the plots in

Figure 5) are based on MLP. That is, models of the MLP type show long training times and low predictive accuracy. In particular, MLP models with training data proportions of 10%, 30%, and 70% consistently fall on solutions dominated by the Pareto frontiers across all three movements. These results highlight that in data-driven regression model building, the balance among training data size, predictive accuracy, and computational cost must be carefully considered.

4.3. SHAP: XAI for Physical Features and Power Prediction

To further investigate the results of the Pareto frontier analysis, we conduct SHAP analysis for two models: SVM (training data 60%) and MLP (training data 10%). The SVM with training data at 60% appears on the Pareto frontier across all three movements, consistently demonstrating good predictive performance with short training time. In contrast, the MLP with training data 10% shows the highest MAPE among the inefficient models, consistently across all three movements. These two contrasting models are therefore selected for SHAP analysis as best-performing and worst-performing models, respectively.

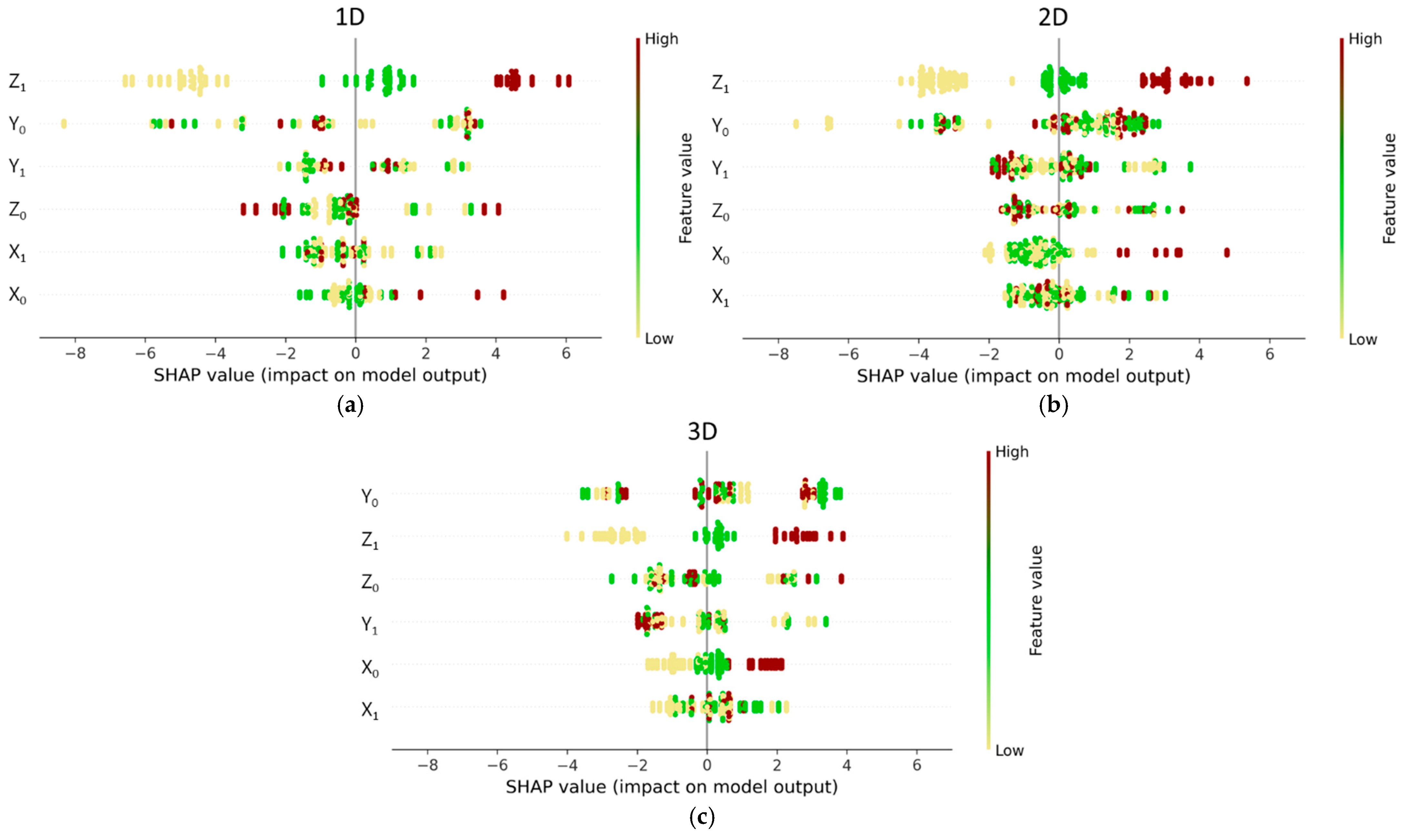

Figure 6 presents the SHAP plots of the SVM model (training data 60%) for power prediction of 1D, 2D, and 3D movements.

For the 1D movement power prediction (

Figure 6a), Z

1 (Z-coordinate of the ending point) is identified as the most influential feature. In the SHAP plot of 2D movement (

Figure 6b), Z

1 emerges again as the most important feature. For 3D movements, unlike in 1D and 2D, Y

0 (Y-coordinate of the starting point) is the most influential feature, followed by Z

1 as the second-most influential feature (

Figure 6c).

According to the physical characteristics of RA movements, when the end effector moves upward (against gravity), joint torque increases and significantly affects power consumption [

14,

71,

72]. In other words, due to the effect of gravity, Z

1 inevitably exerts a meaningful influence on power demand. The SVM model (training data 60%) effectively captures this embedded information in the data, making appropriate use of the features for prediction. For these reasons, Z

1 is identified as the most important feature for 1D and 2D movements and the second-most important for 3D movement. Moreover, the SHAP plots for all three movements in

Figure 6 show a highly linear relationship between the Z

1 feature value and its corresponding SHAP value with clear separation of colors. Specifically, the increase in Z

1 value increases the predicted power value.

In addition, for all movement types, Y

0 and Y

1 (Y-coordinate of the starting and ending points) exhibit higher importance compared to X

0 and X

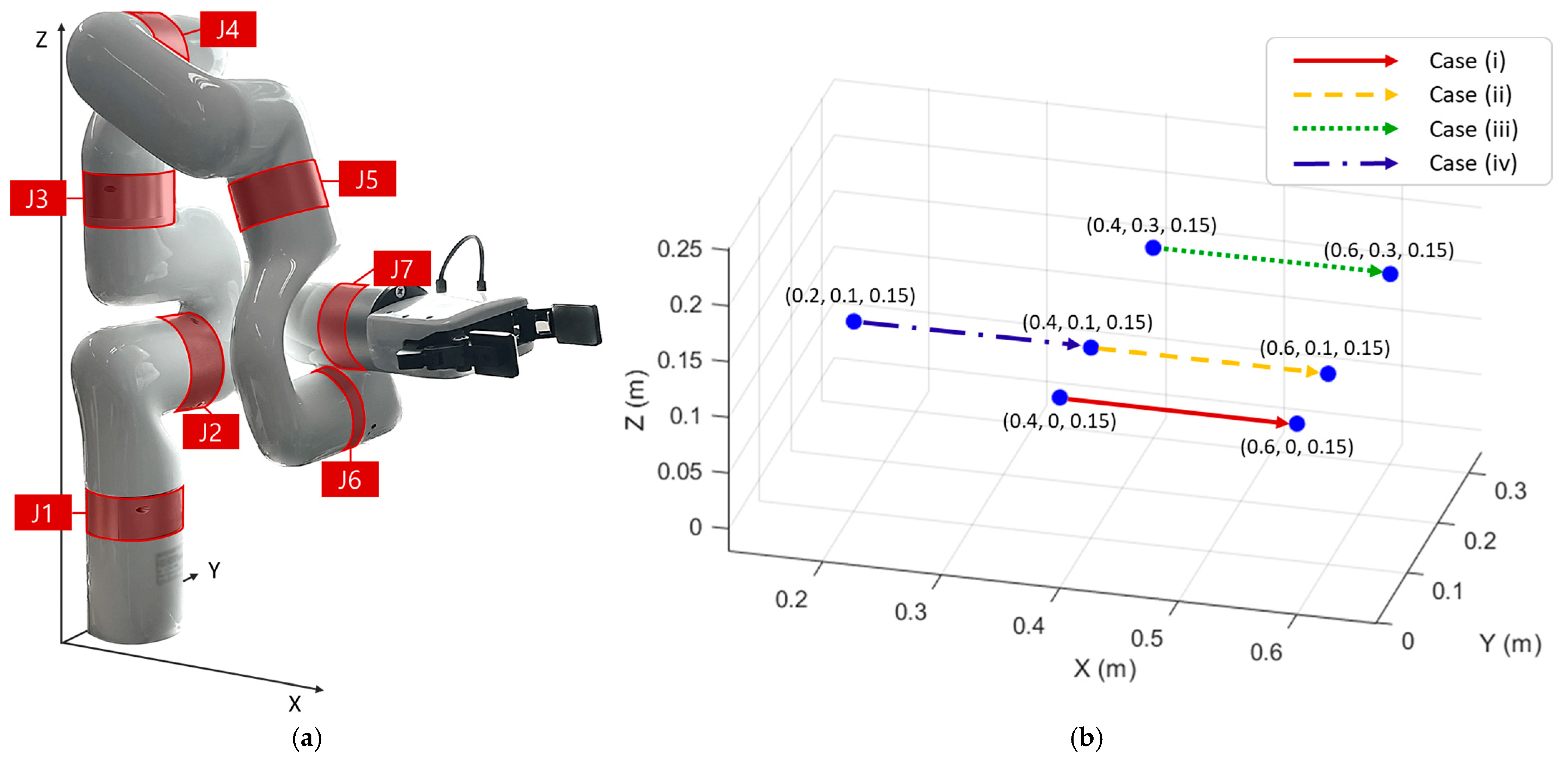

1 (X-coordinate of the starting and ending points). This aligns with the physical observation that lateral displacement (Y-axis) induces larger variations in joint trajectories than forward-backward displacement along the X-axis. To examine the influence of X- and Y-coordinates on seven joints (J1 to J7 as in

Figure 7a) of the RA, we present experimental observations across four movement cases as shown in

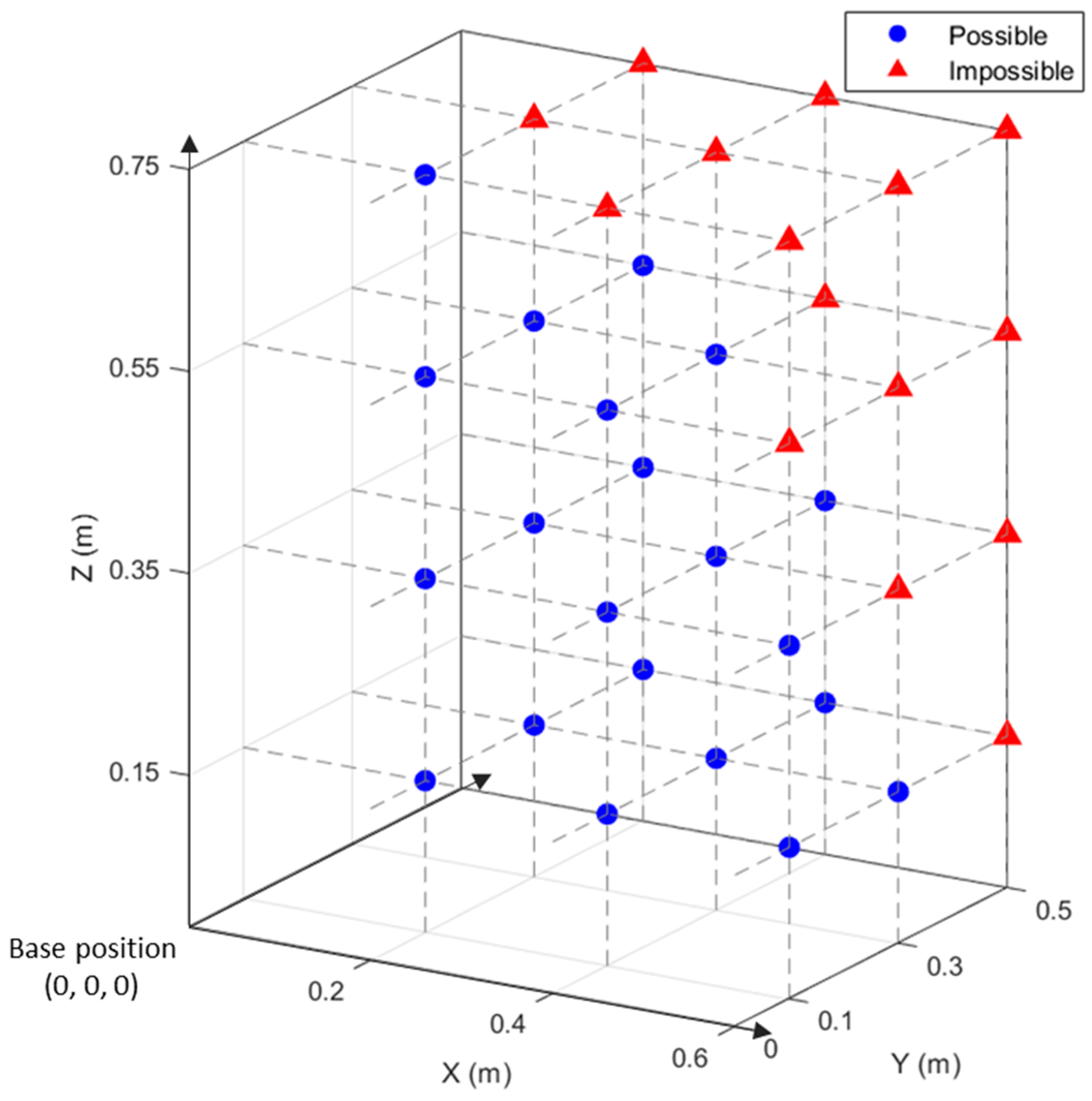

Figure 7b. These cases are selected from the coordinate set used in the power data collection experiment (

Figure 2), so that they represent specific examples within our experimental design.

Table 15 presents the joint angles at the start and end of four movement cases, along with their differences. The comparison of Cases (i), (ii), and (iii) shows that larger Y-coordinate values lead to greater changes in the joint angles. Specifically, the average differences across the seven joints are 13.76, 15.31, and 18.20, respectively. In particular, for J1, J3, J5, and J7, no movement occurs when the Y-coordinate is zero under single-axis motion along the X-direction (Case (i)). In contrast, the comparison of Cases (ii) and (iv) shows that the increase in the X-coordinate does not result in significant differences in joint movement (15.24 and 15.31). These observations indicate that, for the RA employed in this experiment, the Y-coordinate (i.e., lateral displacement from the center) has a stronger influence on joint angle change than the X-coordinate (i.e., forward-backward displacement). Additionally, the SVM model (training data 60%) effectively captures this property from the data, as reflected by the higher importance of Y

0 and Y

1 compared to X

0 and X

1. Moreover, analysis of the color of the SHAP plots in

Figure 6 reveals that, unlike Z

1, the relationships between the feature value of Y

0, Y

1, and their SHAP values are not strictly linear. In other words, in power prediction, the Y-coordinates have substantial interaction effects with other features.

Taken together, the importance of the features utilized by SVM (training data 60%) for power prediction is consistently aligned with physical principles: (i) Z1 is important because it reflects gravitational effects across all movement types, (ii) Y-coordinates have strong influence compared to X-coordinates, reflecting the structural dynamics of the RA, and (iii) interaction effects become more pronounced in higher-dimensional movements. These results explain why SVM (training data 60%) consistently appeared on the Pareto frontiers of all movement types.

The MLP model (training data 10%) shows markedly different SHAP patterns. As shown in

Figure 8, Z

0 and Z

1 relatively show low importance across 1D, 2D, and 3D movements, indicating that the model failed to capture the effect of gravity, a fundamental driver of power consumption. Instead, the model assigns abnormally high importance to features such as X

0 and X

1, with absolute SHAP values far exceeding those observed in SVM (training data 60%). This suggests that MLP (training data 10%) overfits to local data patterns, relying excessively on less relevant features and neglecting physically meaningful ones. In other words, MLP fails to capture the critical patterns among features and does not effectively exploit the embedded information in the data. Thus, MLP (training data 10%) shows consistently poor predictive performance and high MAPE, compared with SVM (training data 60%).

Our analysis provides explainable guidance for shop-floor RA energy management. SHAP results indicate that high-performing models, such as SVM, succeed because they not only fit the data but also learn the RA’s physical characteristics embedded in the power data. SVM consistently assigns high importance to Z-axis motion, reflecting gravitational load. SVM also separates the asymmetric effects of lateral (Y-axis) and forward (X-axis) motion: the distinct joint-angle trajectories generate different torque requirements, leading to different power demands. In contrast, MLP does not capture these relationships between physical patterns and the power demand of RA’s movement, resulting in poor accuracy. These findings show that capturing the relevant physics in the data directly drives predictive performance.

The results of our analysis provide critical insights that are not limited to a simple accuracy comparison, directly addressing the need for explainable and practical RA energy management tools on the shop floor. Particularly, the SHAP analysis reveals that the excellence of the well-performing model is not just about predictive accuracy. The accurate power prediction model can successfully learn the underlying physical principles of the RA operation. For instance, SVM (training data 60%) consistently recognizes the importance of Z-axis movement due to gravity. Moreover, SVM (training data 60%) captures the asymmetrical impact of lateral (Y-axis) versus forward (X-axis) movements. As our joint angle analysis shows, these seemingly similar horizontal movements (along X and Y axes) result in vastly different kinematic changes and different power demands of RA. In contrast, the MLP (training data 10%) fails to capture the fundamental physical features and therefore shows poor predictive performance. These results highlight that the RA power prediction model’s ability to capture the physics embedded in the data is an important driver of its predictive success.

The results also highlight the core contribution of our study: energy consumption of RA is highly connected to operational factors in ways that are often counterintuitive. In terms of energy consumption, moving a certain distance along the X-axis might intuitively be considered equivalent to moving the same distance along the Y-axis by a shop-floor engineer. However, our findings show that this intuition is not true. The energy consumption of an RA is deeply dependent on the specific trajectory and how that trajectory determines the RA’s joints to act against physical forces such as gravity and inertia. Therefore, relying on intuition alone for RA energy management is inadequate, and it is important to adopt data-driven, analytical approaches, as we presented. These insights have significant implications for RA task design in manufacturing. For any given task, defined by a starting and ending point, there exists a near-infinite number of feasible trajectories. Thus, finding the energy-efficient path among all possible routes can offer significant potential for energy saving. For example, a simple straight-line path might not be the most energy-efficient if it involves significant lateral movement that strains specific joints. In such cases, a slightly curved path can reduce the high-load movements and result in the same production outcome with substantial energy savings. With the insights offered by our analysis, shop-floor engineers can critically assess the software-generated RA trajectories and select energy-efficient trajectories for performing the required task. The framework and RA power prediction models validated in this study provide the foundational tools necessary to find such energy-efficient RA paths.

Consequently, our findings in this study provide several key contributions for RA energy management. First, the results suggest that an SVM model, trained with an appropriate amount of data, can be a robust recommendation. Furthermore, shop-floor engineers operating RA can readily develop and utilize power prediction models by referring to the detailed information provided in this study, such as hyperparameter settings. Moreover, the XAI analysis reveals a counterintuitive insight: seemingly similar horizontal movements (along X and Y axes) can have different power demands. These findings underscore that relying on intuition is insufficient and that careful, model-driven examination is essential to design RA tasks for energy efficiency.