Control System for an Open-Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Fed by a Four-Leg Inverter

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

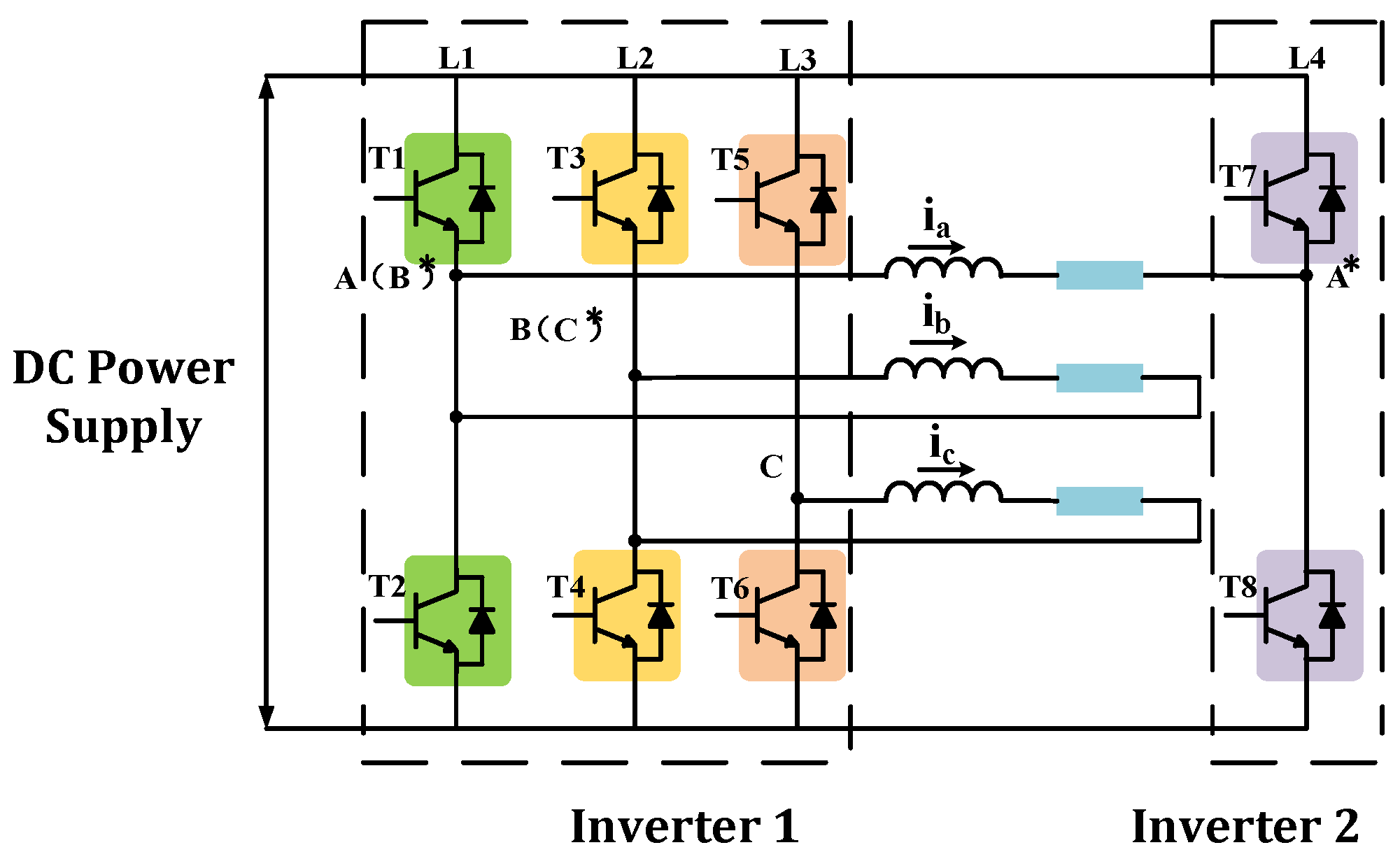

2. Four-Leg Inverter Open-Winding Motor Control System

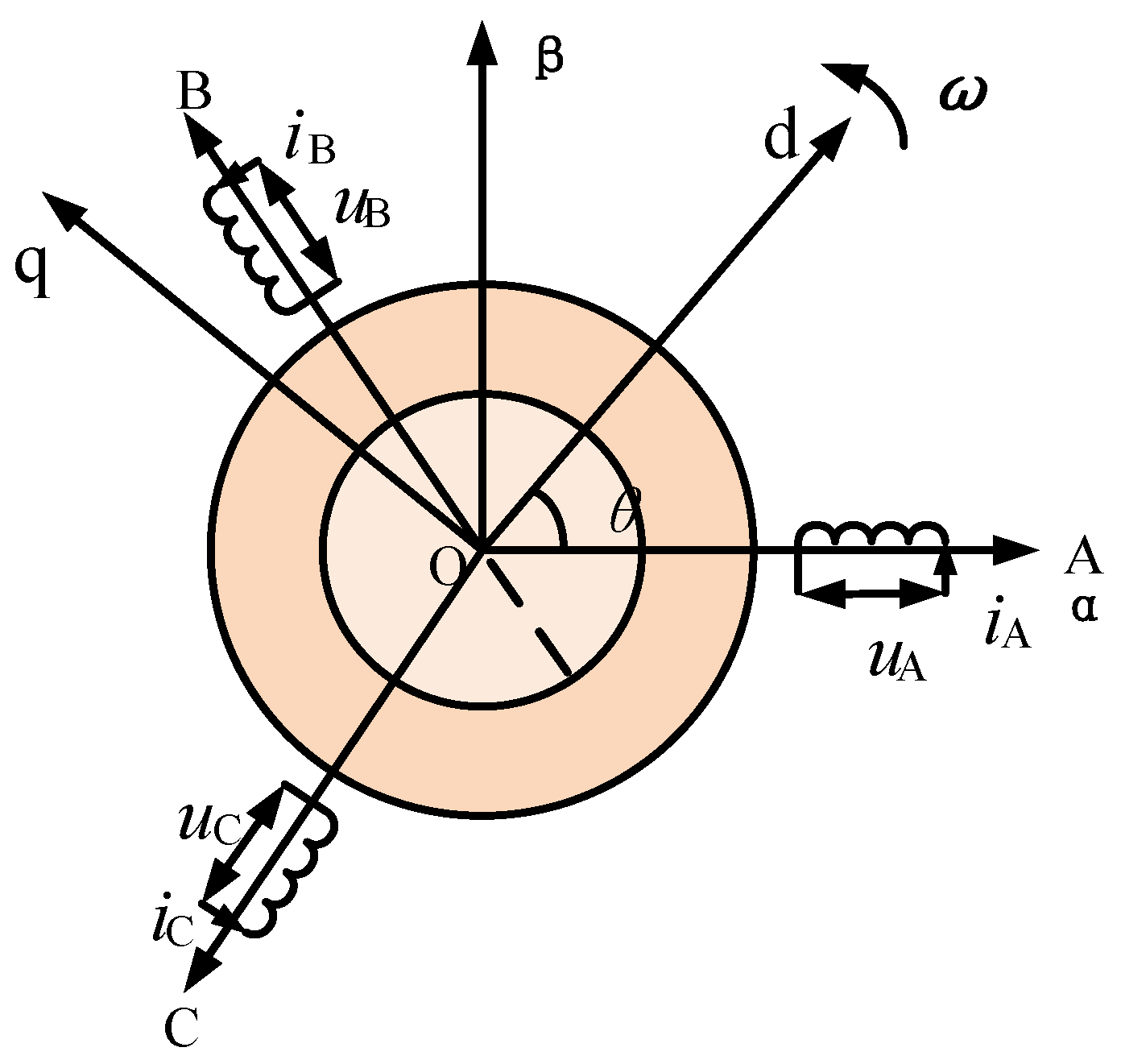

2.1. Open-Winding Motor Mathematical Model

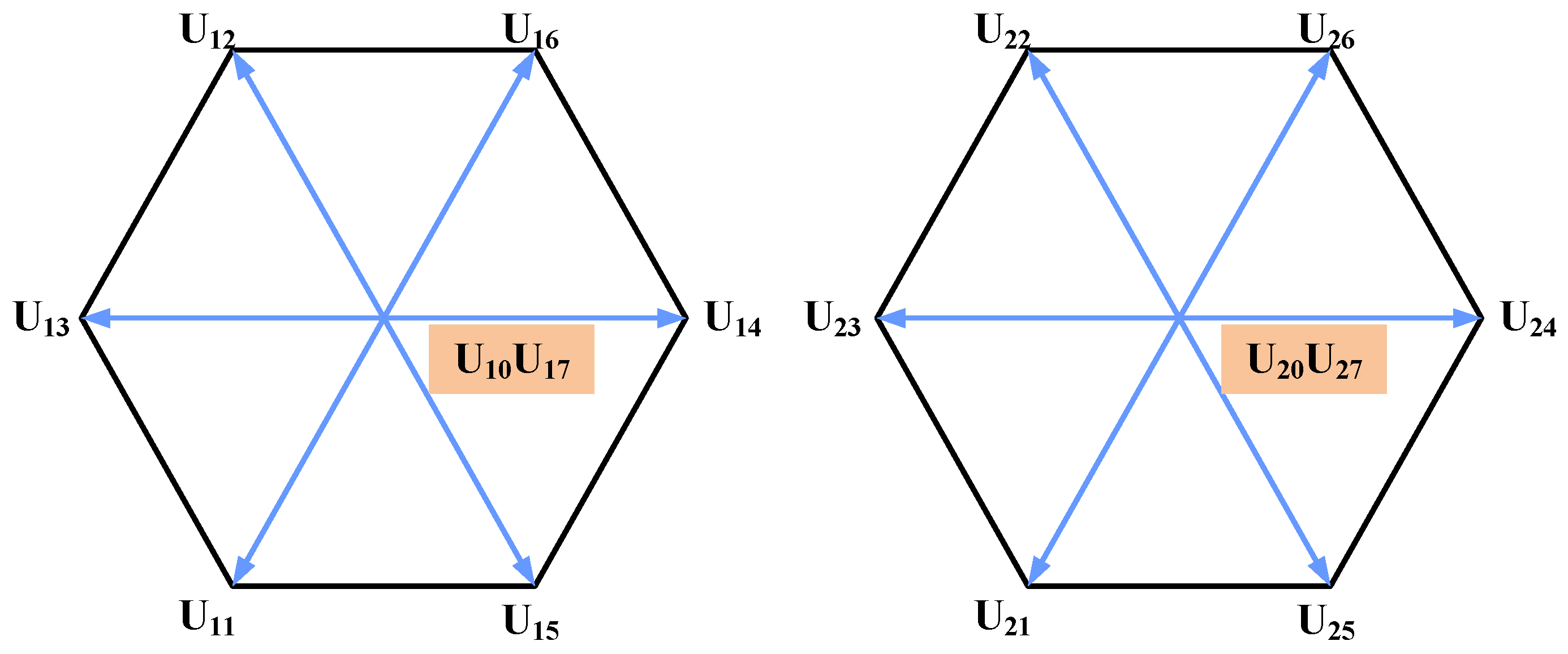

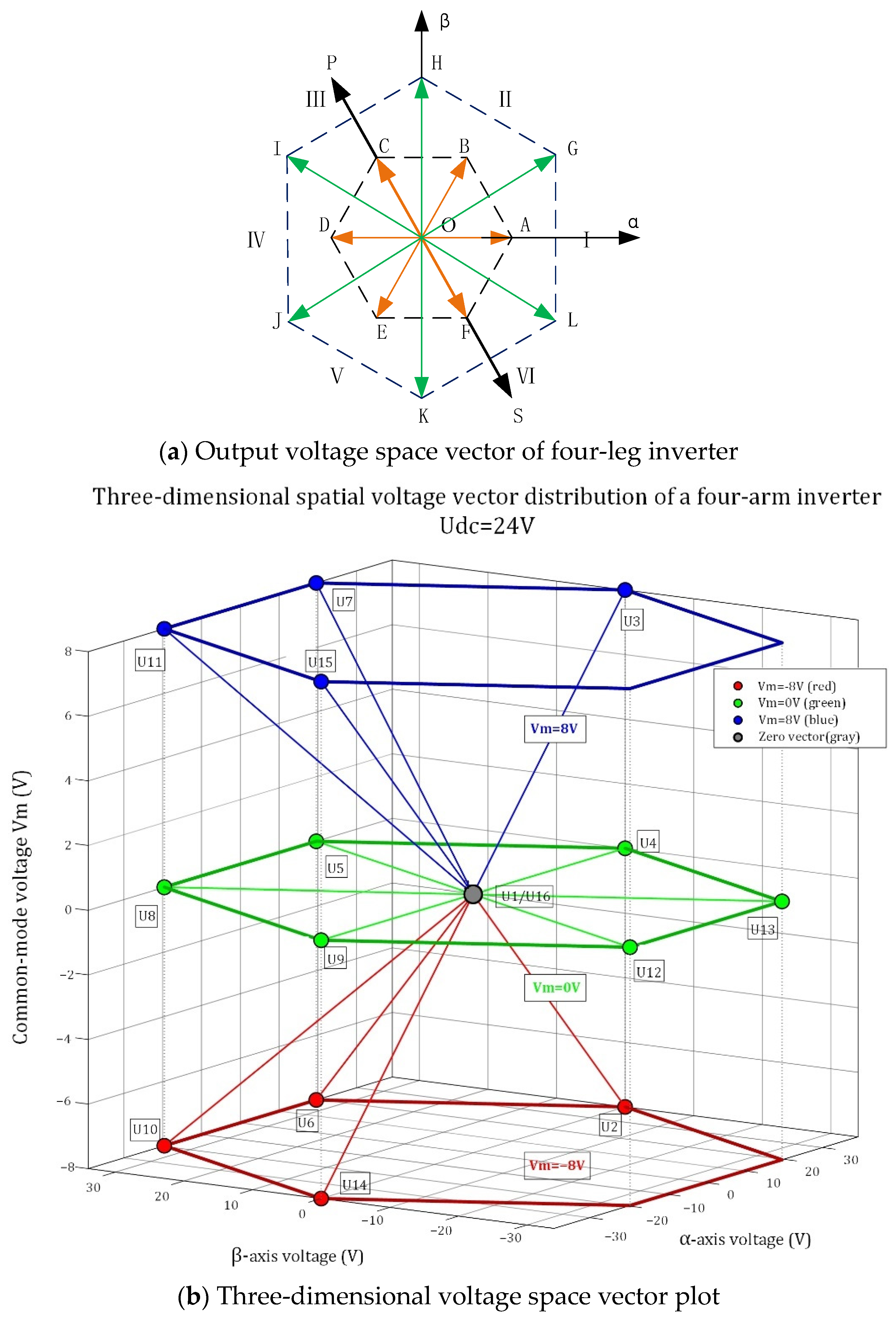

2.2. Four-Leg Inverter Voltage Vector Analysis

3. Improved Hysteresis Current Control Strategy for Four-Leg Inverter

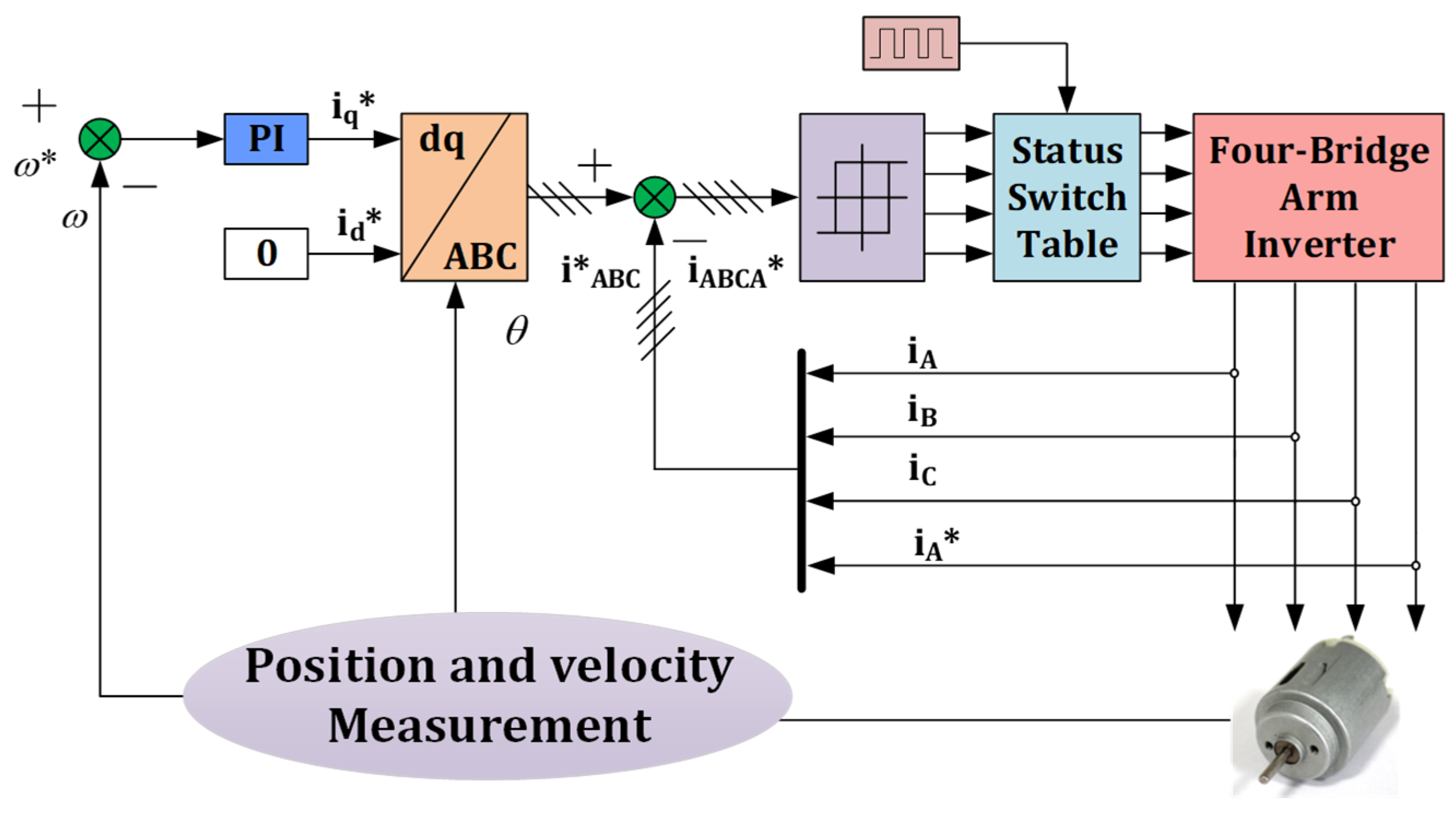

3.1. Open-Winding PMSM Control System Based on Improved Hysteresis Current Control for Four-Leg Inverter

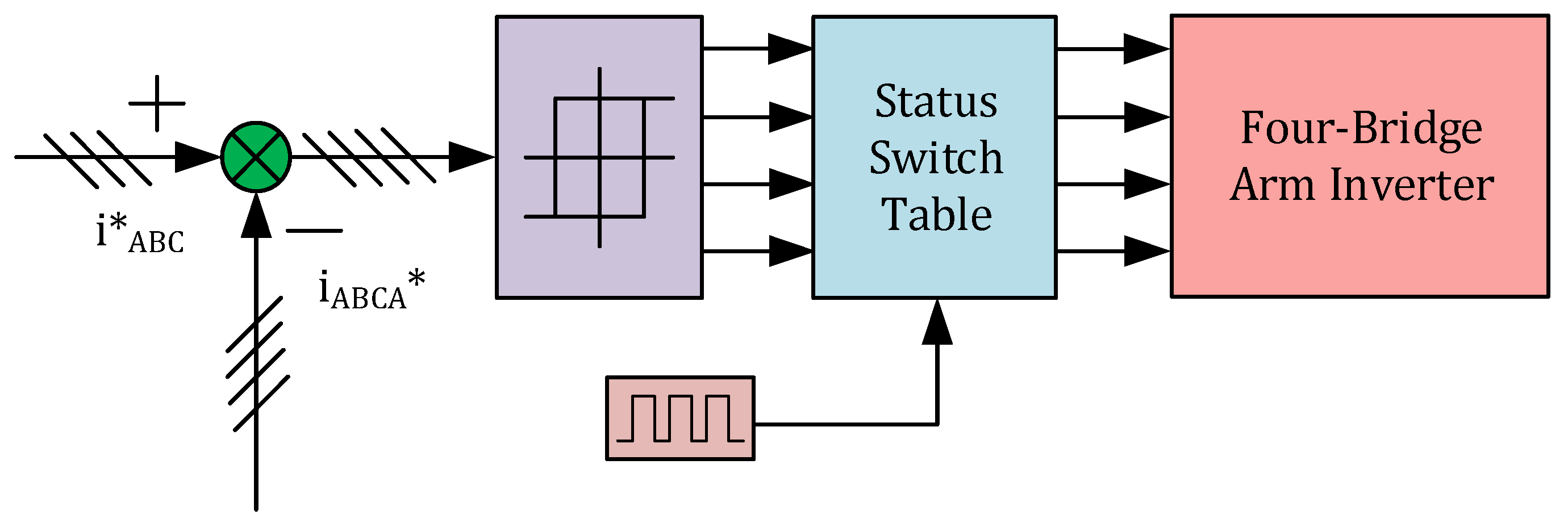

3.2. Operating Principle of Improved Hysteresis Current Control

3.3. Mathematical Model of the Improved Hysteresis Current Control

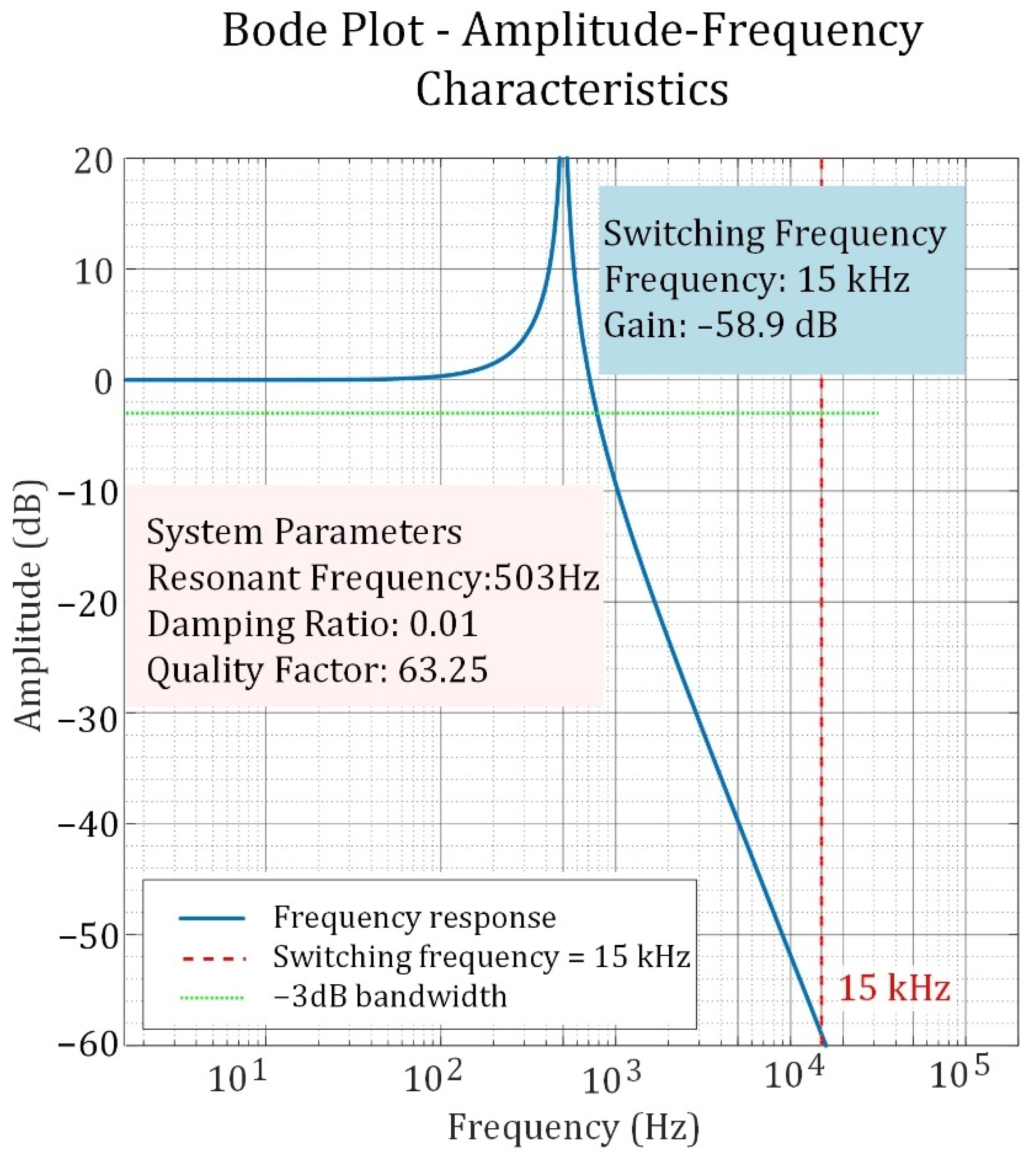

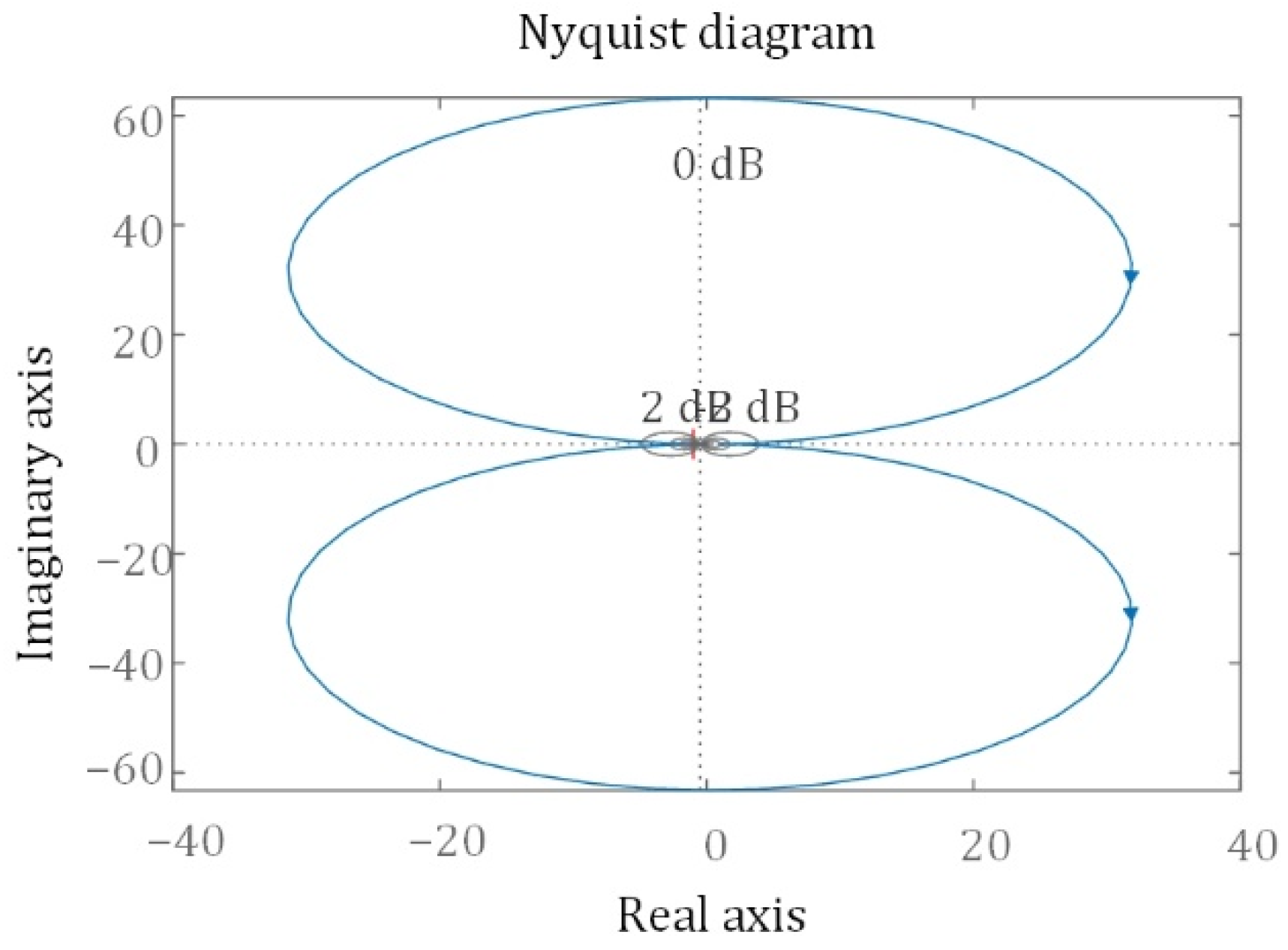

3.4. Stability Analysis of the Improved Hysteresis Current Control

4. Experimental Analysis

- (1)

- Speed Regulation Test: To evaluate the speed control capability, the initial reference speed of the open-winding motor was set to 500 r/min with an initial load of 2 N·m. After motor startup, the reference speed was increased to 800 r/min to test the acceleration performance of the system. The reference speed was then returned to 500 r/min to examine the deceleration performance. Variations in key parameters were observed throughout the speed regulation process. The experimental results are shown in Figure 10.

- (2)

- Load Variation Test: To evaluate the load disturbance rejection capability, the open-winding motor’s reference speed was set to 800 r/min, and the reference torque was set to 0 N·m. After the motor reached steady-state operation, a load disturbance was applied, and the variations in motor parameters were observed. The load was then removed to restore no-load conditions, and the parameter changes were monitored again. The experimental results are shown in Figure 11.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, J.; Yan, L.; Jin, Z. Modeling and Analysis of Winding Open Circuit Fault in Asymmetrical Multi-phase Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2025, 20, 3247–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Jia, Y.; Luo, M.; Zhang, S. Three-level control for open winding permanent magnet synchronous motors. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2849, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Phan, D.Q.; Nguyen, T.D. Decentralized Multilevel Inverters Based on SVPWM for Five-Phase Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2024, 20, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becheikh, M.; Hassain, S. Co-Simulation of permanent magnet synchronous motor with demagnetized fault fed by PWM inverter. Prz. Elektrotech. 2024, 2024, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, X. Research on efficiency optimization control strategy of permanent magnet synchronous motor. Electron. Des. Eng. 2023, 31, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D. Effect of DC bus voltage on efficiency of permanent magnet synchronous motor. Micro Mot. 2023, 51, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Yin, W.; Guo, Y. Hybrid mechanism-data-driven iron loss modelling for permanent magnet synchronous motors considering multiphysics coupling effects. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2024, 18, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadalizadeh, A.; Amirahmadi, M.; Tolou Askari, M.; Babaeinik, M. A New Approach for Improvement of the Efficiency and Torque Ripple of the High-Speed Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 2024, 48, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, Y. Research on inter-turn short circuit detection of stator non-excitation phase winding of AC motor based on open transformer method. J. Electr. Mach. Control 2024, 28, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar, K.R.; Srinivas, S. Discontinuous Decoupled PWMs for Reduced Current Ripple in a Dual Two-Level Inverter Fed Open-End Winding Induction Motor Drive. Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 2493–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Z. Evaluation of model-free predictive current control in three-phase permanent magnet synchronous motor drives fed by three-level neutral-point-clamped inverters. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2022, 50, 3968–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.L.; Ho, D.L.; Beum, K.L. Differential mode voltage reduction in dual inverters used to drive open-end winding interior permanent magnet synchronous motors. J. Power Electron. 2023, 23, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, A.; Jin, D. Simplified model prediction current control strategy for permanent magnet synchronous motor. J. Power Electron. 2022, 22, 1860–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.W. Interturn Short Fault Diagnosis Using Magnitude and Phase of Currents in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. Sensors 2022, 22, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.; Jin, W.L. Inverter average input power estimation algorithm in low-frequency modulation index operation of permanent magnet synchronous motors. J. Power Electron. 2022, 23, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Won, C.Y. Space Vector Modulation (SVM)-Based Common-Mode Current (CMC) Reduction Method of H8 Inverter for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM) Drives. Energies 2021, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A. Comparative Study of BLDC Motor Drives with Different Approaches: FCS-Model Predictive Control and Hysteresis Current Control. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanane, L.; Mouna, G.; Kheireddine, C. BBO-Based State Optimization for PMSM Machines. Vietnam. J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 9, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Su, J.; Qin, H.; Zhao, C. Simplified multi-step predictive control for surface permanent magnet synchronous motor. Energy Rep. 2020, 6 (Suppl. S9), 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanayem, H.; Alathamneh, M.; Nelms, R.M. PMSM Field-Oriented Control with Independent Speed and Flux Controllers for Continuous Operation under Open-Circuit Fault at Light Load Conditions. Energies 2024, 17, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Peng, J.; Sun, X. Model predictive flux control of six-phase permanent magnet synchronous motor with novel virtual voltage vectors. Electr. Eng. 2022, 104, 2835–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ding, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Three-vector-based low-complexity model predictive current control with reduced steady-state current error for permanent magnet synchronous motor. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2020, 14, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Diao, C.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, W. Unity power factor control of permanent magnet synchronous motor by using open winding configuration. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2020, 64, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, S.B.; Vimlesh, V. A New Stator Resistance Estimation Technique for Vector-Controlled PMSM Drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 6536–6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Lin, B.; Yu, J. Research on Common Mode Voltage Suppression Method for Open Winding Motor Control System. J. Mech. Electr. Eng. 2013, 30, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Hanke, S.; Wallscheid, O.; Böcker, J. A direct model predictive torque control approach to meet torque and loss objectives simultaneously in permanent magnet synchronous motor applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Predictive Control of Electrical Drives and Power Electronics (PRECEDE), Pilsen, Czech Republic, 4–6 September 2017; pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, K.; Dong, X.; Liu, L.; Hu, W.; Nian, H. A Unified Modulation Strategy for Open—Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors under Phase—Open Fault Considering Zero—Sequence Current Suppression. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2020, 35, 2387–2395. [Google Scholar]

- Nian, H.; Zeng, H.; Zhou, Y. Zero-sequence current suppression strategy for common DC bus open-winding permanent magnet synchronous motor. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2015, 30, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- An, Q.; Yao, F.; Sun, L.; Sun, L. SVPWM Modulation Strategy and Zero-sequence Voltage Suppression Method for Dual Inverter. Proc. CSEE 2016, 36, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L.; Jin, S.; Cao, W.; Wang, D.; Kirtley, J.L. Developing a New SVPWM Control Strategy for Open-Winding Brushless Doubly Fed Reluctance Generators. IEEE Trans. Ind. 2015, 51, 4567–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Huang, W.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X. Lack of Phase Compatibility Fault Direct Torque Control of Common Bus Open Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2020, 35, 5065–5074. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Sun, D.; Wang, M. Research on Fault-tolerant Control Strategy for Model Predictive Control of Open-winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor under Phase Fault Fault. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2021, 36, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Sun, F.; Ma, W.; Wang, J. Research on control strategy of three-phase four-bridge arm inverter. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2020, 57, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J. Three-dimensional Vector Pulse Width Modulation Strategy for Z-Source Three-phase Four-Bridge Arm Inverter. Electr. Mach. Control Appl. 2019, 46, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||

| 0 | −1 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||

| 0 | −1 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Rated Voltage (V) | 24 |

| Rated Current (A) | 2 |

| Rated Power (W) | 60 |

| Rated Speed (r/min) | 3000 |

| Number of Pole Pairs | 4 |

| Stator Flux Linkage (Wb) | 0.175 |

| D-Q Inductance (mH) | 8.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, H.; Cheng, S.; Jing, Z.; Liu, W. Control System for an Open-Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Fed by a Four-Leg Inverter. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12582. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312582

Lin H, Cheng S, Jing Z, Liu W. Control System for an Open-Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Fed by a Four-Leg Inverter. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12582. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312582

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Hai, Siyi Cheng, Zhixin Jing, and Weiyu Liu. 2025. "Control System for an Open-Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Fed by a Four-Leg Inverter" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12582. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312582

APA StyleLin, H., Cheng, S., Jing, Z., & Liu, W. (2025). Control System for an Open-Winding Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Fed by a Four-Leg Inverter. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12582. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312582