Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm of the Pancreas: EUS Features and Diagnostic Accuracy of EUS-Guided Fine Needle Biopsy Using a 22-Gauge Fork-Tip Needle in a High Volume Center

Abstract

1. Backgrounds and Aims

2. Patients and Methods

- -

- EUS-guided FNB performed at another hospital;

- -

- Absence of EUS-guided FNB;

- -

- Performance of EUS-guided FNA;

- -

- Absence of an available contrast-enhanced imaging procedure (contrast-enhanced CT scan and/or contrast-enhanced MRI scan) performed before the EUS-guided FNB;

- -

- Lack of a surgical specimen with definitive confirmation of the diagnosis of SPN.

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

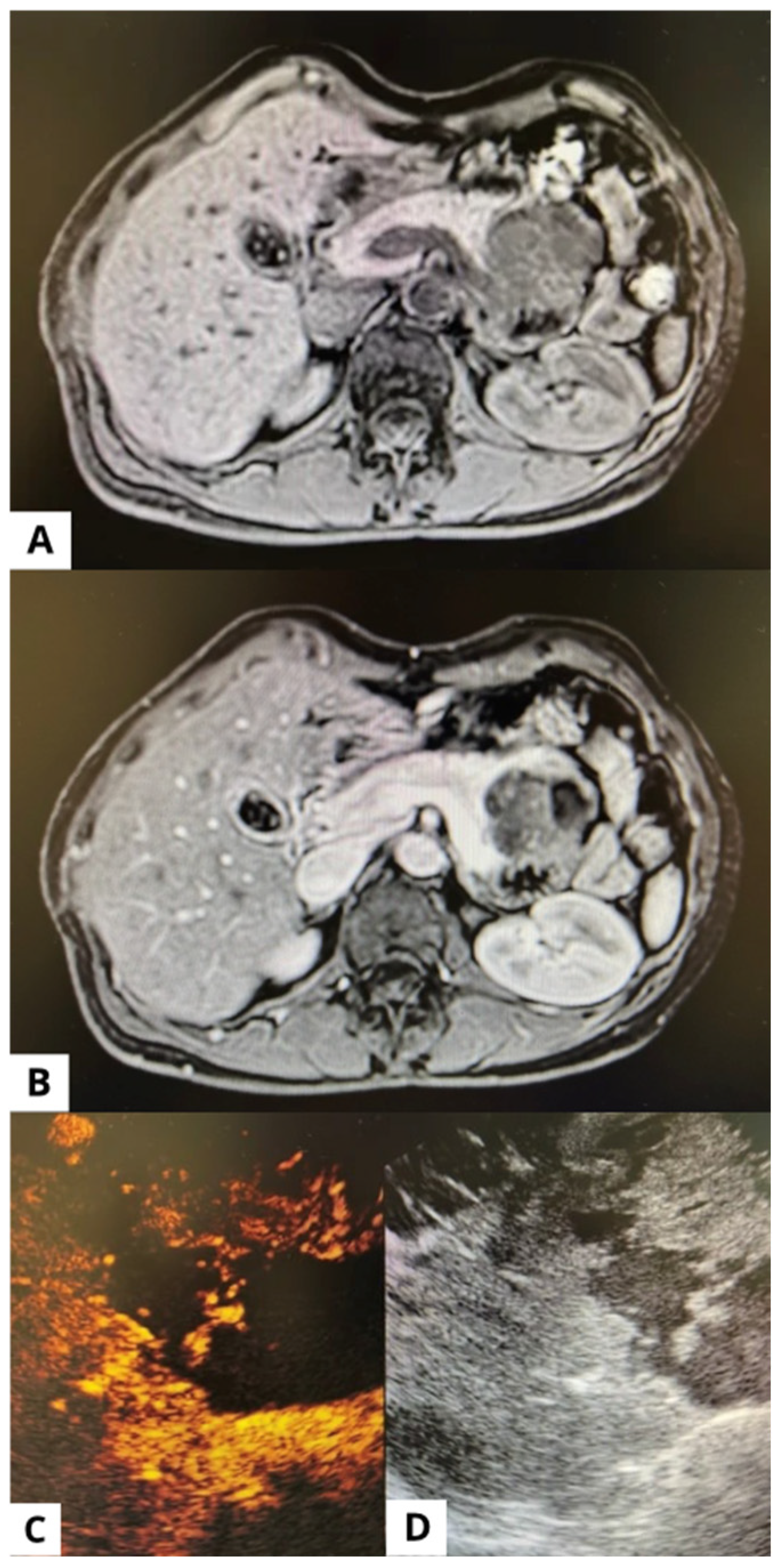

3.1. Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)

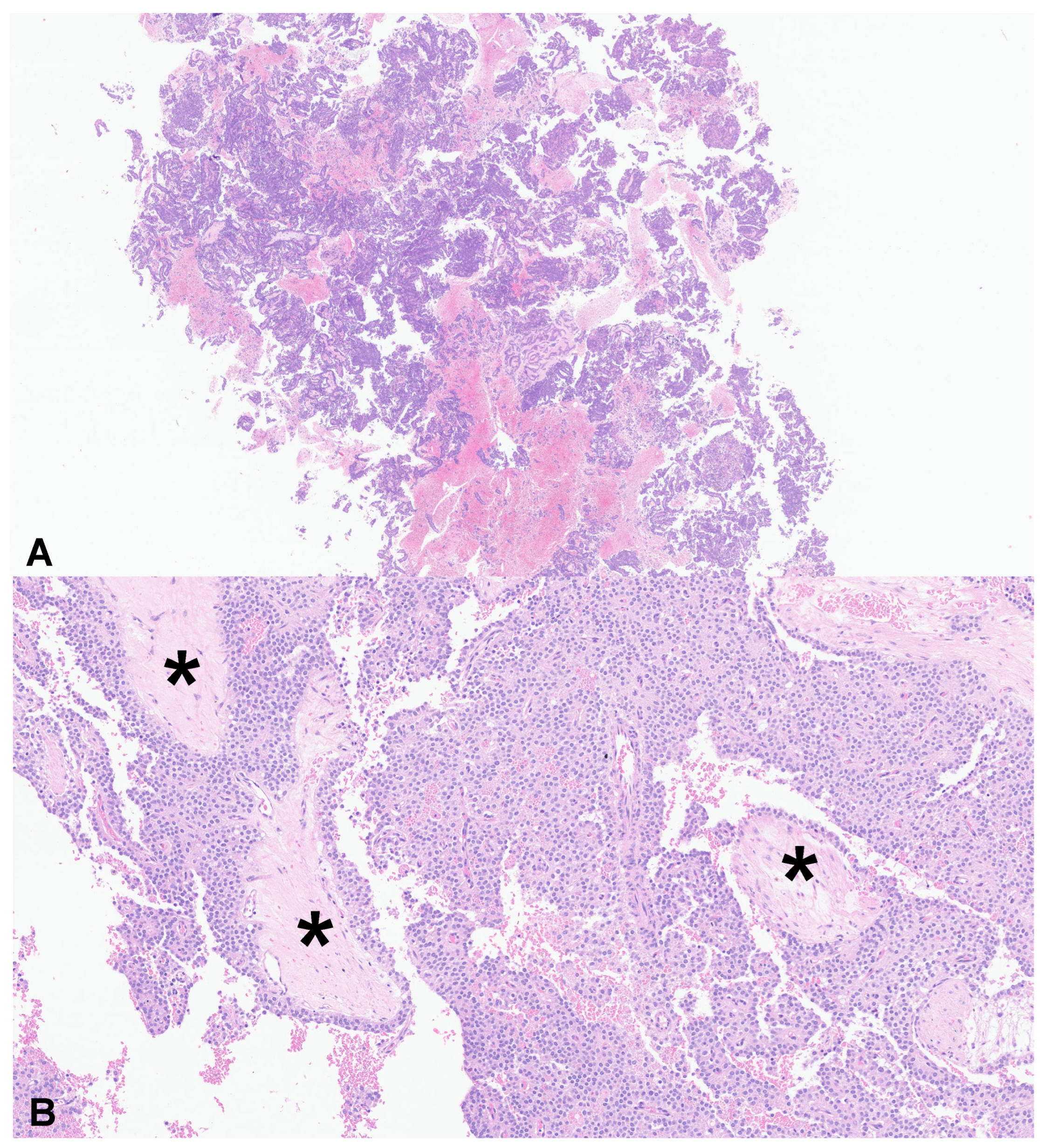

3.2. EUS-Guided FNB

3.3. Radiology

3.4. Long-Term Follow-Up

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Law, J.K.; Ahmed, A.; Singh, V.K.; Akshintala, V.S.; Olson, M.T.; Raman, S.P.; Ali, S.Z.; Fishman, E.K.; Kamel, I.; Canto, M.I.; et al. A systematic review of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms: Are these rare lesions? Pancreas 2014, 43, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papavramidis, T.; Papavramidis, S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: Review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2005, 200, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.F.; Hu, Z.H.; Wang, X.B.; Guo, J.M.; Cheng, X.D.; Zhang, Y.L.; Xu, Q. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: A review of 553 cases in Chinese literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimstra, D.S.; Hruban, R.H.; Sigel, C.S.; Klöppel, G. Tumors of the Pancreas; American Registry of Pathology: Arlington, VI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Digestive System Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2019; Available online: https://publications.iarc.who.int/Book-And-Report-Series/Iac-Iarc-Who-Cytopathology-Reporting-Systems/WHO-Reporting-System-For-Pancreaticobiliary-Cytopathology-2022 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Marchegiani, G.; Andrianello, S.; Massignani, M.; Malleo, G.; Maggino, L.; Paiella, S.; Ferrone, C.R.; Luchini, C.; Scarpa, A.; Capelli, P.; et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: Specific pathological features predict the likelihood of postoperative recurrence. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 114, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, E.; Mafficini, A.; Hirabayashi, K.; Lawlor, R.T.; Fassan, M.; Vicentini, C.; Barbi, S.; Delfino, P.; Sikora, K.; Rusev, B.; et al. Molecular alterations associated with metastases of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J. Pathol. 2019, 247, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- La Rosa, S.; Bongiovanni, M. Pancreatic Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm: Key Pathologic and Genetic Features. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2020, 144, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samad, A.; Shah, A.A.; Stelow, E.B.; Alsharif, M.; Cameron, S.E.; Pambuccian, S.E. Cercariform cells: Another cytologic feature distinguishing solid pseudopapillary neoplasms from pancreatic endocrine neoplasms and acinar cell carcinomas in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspirates. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013, 121, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Lai, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, L.; Liu, L.; Ma, K.; Li, J.; Deng, Q. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas (SPNs): Diagnostic accuracy of CT and CT imaging features. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 22, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crinò, S.F.; Di Mitri, R.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Tarantino, I.; de Nucci, G.; Deprez, P.H.; Carrara, S.; Kitano, M.; Shami, V.M.; Fernández-Esparrach, G.; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Biopsy with or Without Rapid On-site Evaluation for Diagnosis of Solid Pancreatic Lesions: A Randomized Controlled Non-Inferiority Trial. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Pretis, N.; Crinò, S.F.; Frulloni, L. The Role of EUS-Guided FNA and FNB in Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.W.; Qin, M.Z.; Jiang, H.X.; Qin, S.Y. Comparison of EUS-FNA and EUS-FNB for diagnosis of solid pancreatic mass lesions: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 59, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, K.M.; Tehami, N.; Maher, B.; Asif, S.; Rawal, K.K.; Balaban, D.V.; Tag-Adeen, M.; Ghalim, F.; Abbas, W.A.; Ghoneem, E.; et al. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the characterization of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 15, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsenti, D.; Caillol, F.; Chaput, U.; Perrot, B.; Koch, S.; Vuitton, L.; Jacques, J.; Valats, J.C.; Poincloux, L.; Subtil, C.; et al. Safety of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration for Pancreatic Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm Before Surgical Resection: A European Multicenter Registry-Based Study on 149 Patients. Pancreas 2020, 49, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.G.; Mani, H.; Wang, Z.Q.; Li, W. Cytological Diagnosis of Pancreatic Solid-Pseudopapillary Neoplasm: A Single-Institution Community Practice Experience. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.F.; Li, Z.; Chen, K.; Liu, M.Q.; Ye, Z.; Chen, X.M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.J.; Xu, X.W.; Ji, S.R. Multimodality imaging differentiation of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and solid pseudopapillary tumors with a nomogram model: A large single-center study. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 970178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nass, K.J.; Zwager, L.W.; van der Vlugt, M.; Dekker, E.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; Ravindran, S.; Thomas-Gibson, S.; Fockens, P. Novel classification for adverse evvents in GI endoscopy: The AGREE classification. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 95, 1078–1085.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Robertis, R.; Marchegiani, G.; Catania, M.; Ambrosetti, M.C.; Capelli, P.; Salvia, R.; D'Onofrio, M. Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasms of the Pancreas: Clinicopathologic and Radiologic Features According to Size. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2019, 213, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, S.P.; Kawamoto, S.; Law, J.K.; Blackford, A.; Lennon, A.M.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Hruban, R.H.; Cameron, J.L.; Fishman, E.K. Institutional experience with solid pseudopapillary neoplasms: Focus on computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, conventional ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound, and predictors of aggressive histology. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2013, 37, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total patients nr. (%) | 37 (100) |

| Females nr. (%) | 32 (86.5) |

| Mean age years (SD) | 35.8 (15.8) |

| Symptoms nr. (%) | 22 (59.5) |

| Abdominal pain nr. (%) | 15 (40.5) |

| Acute pancreatitis nr. (%) | 2 (5.4) |

| Weight loss nr. (%) | 1 (2.7) |

| Vomiting nr. (%) | 1 (2.7) |

| Itching nr. (%) | 1 (2.7) |

| Family history with pancreatic disease nr. (%) | 1 (2.7) |

| Ca19.9 > 37 U/mL nr. (%) | 1 (2.7) |

| Diabetes nr. (%) | 3 (8.1) |

| Imaging | EUS | p | |

| Size, median (SD) mm | 41.4 (15.1) | 35.8 (15.8) | 0.12 |

| Contrast enhancement | |||

| Hypo-enhancing nr. (%) | 19 (51.4) | 9 (24.3) | |

| Iso-enhancing nr. (%) | 10 (27.0) | 9 (24.3) | 0.01 |

| Hyper-enhancing nr. (%) | 8 (21.6) | 19 (51.4) | |

| Cystic appearance nr. (%) | 6 (16.2) | 15 (40.5) | 0.03 |

| Dilation of CBD nr. (%) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) | >0.99 |

| Dilation of MPD nr. (%) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (13.5) | >0.99 |

| Calcifications nr. (%) | 8 (21.6) | 6 (16.2) | 0.77 |

| Pseudocapsule nr. (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.99 |

| Correct | Not-Correct | p | |

| Total nr. (%) | 20 (54.1) | 17 (45.9) | / |

| Females nr. (%) | 19 (95.0) | 13 (76.5) | 0.159 |

| Mean age years (SD) | 26.7 (11.2) | 43.9 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| Location | |||

| Head nr (%) | 5 (25.0) | 3 (17.7) | 0.006 |

| Body nr (%) | 12 (60.0) | 3 (17.7) | |

| Tail nr (%) | 3 (15.0) | 11 (64.7) | |

| Size mm (SD) | 46.4 (26.9) | 36.7 (21.1) | 0.08 |

| Main cystic aspect nr. (%) | 3 (15.0) | 3 (17.6) | >0.99 |

| Enhancement | |||

| Hypo nr. (%) | 10 (50.0) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Iso nr. (%) | 6 (30.0) | 4 (23.5) | >0.99 |

| Hyper nr. (%) | 4 (20.0) | 5 (29.44) | |

| Dilation of MPD nr. (%) | 5 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0.05 |

| Dilation of CBD nr. (%) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) | 0.012 |

| Location | ||

| Head | 1 # | |

| Body | 8.99 (0.58–139.31) | 0.116 |

| Tail | 0.31 (0.03–3.78) | 0.358 |

| Size | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.053 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Pretis, N.; Mastella, P.; Baldan, R.; Martinelli, L.; Mantovani, W.; Caldart, F.; Crucillà, S.; Luchini, C.; Mattiolo, P.; Scarpa, A.; et al. Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm of the Pancreas: EUS Features and Diagnostic Accuracy of EUS-Guided Fine Needle Biopsy Using a 22-Gauge Fork-Tip Needle in a High Volume Center. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12313. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212313

de Pretis N, Mastella P, Baldan R, Martinelli L, Mantovani W, Caldart F, Crucillà S, Luchini C, Mattiolo P, Scarpa A, et al. Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm of the Pancreas: EUS Features and Diagnostic Accuracy of EUS-Guided Fine Needle Biopsy Using a 22-Gauge Fork-Tip Needle in a High Volume Center. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12313. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212313

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Pretis, Nicolò, Pietro Mastella, Roberto Baldan, Luigi Martinelli, William Mantovani, Federico Caldart, Salvatore Crucillà, Claudio Luchini, Paola Mattiolo, Aldo Scarpa, and et al. 2025. "Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm of the Pancreas: EUS Features and Diagnostic Accuracy of EUS-Guided Fine Needle Biopsy Using a 22-Gauge Fork-Tip Needle in a High Volume Center" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12313. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212313

APA Stylede Pretis, N., Mastella, P., Baldan, R., Martinelli, L., Mantovani, W., Caldart, F., Crucillà, S., Luchini, C., Mattiolo, P., Scarpa, A., Crinò, S. F., Conti Bellocchi, M. C., De Robertis, R., Paiella, S., Pea, A., Amodio, A., De Marchi, G., & Frulloni, L. (2025). Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm of the Pancreas: EUS Features and Diagnostic Accuracy of EUS-Guided Fine Needle Biopsy Using a 22-Gauge Fork-Tip Needle in a High Volume Center. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12313. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212313