The original raw files obtained from CT scanning were 16-bit gray-scale 3D Raw files with a voxel resolution of 3400 × 3400 × 2600, and the size of the Raw file is approximately 60 GB for each sample. Directly processing the original files resulted in extremely low computational efficiency, and the VRAM required for calculating the PNM network exceeded the total VRAM of the hardware platform. To increase data processing efficiency and successfully calculate the PNM, as shown in

Figure 5, we extracted sub-volumes (the yellow dashed line part) from the central part of the samples. The size of the sub-volume is around 2.5GB. It can be seen that the CT scan results of the three samples with different permeability are similar to the SEM scan results. The low-permeability sample C1 (1.96 mD) has higher cementation of inter-gravel matrix, with only a small amount of intergranular fractures observable on the surface (as shown in

Figure 5a). In contrast, the higher permeability samples C2 (11.22 mD) and C3 (59.5 mD) show certain intergranular pores on the surface (as shown in

Figure 5b,c).

3.3.1. Two-Dimensional Slice Analysis of Pore Structure Variation

We selected specific slices from the three samples where pore changes before and after water flooding were noticeable as examples to analyze the specific pore changes. The example slice for sample C1 is shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6 shows the 375th slice along the z-axis from the sample C1 dataset, which comprises a total of 650 slices in the Z-direction.

Figure 6a displays pore structures before water flooding, and

Figure 6b shows the same region after water flooding. Sample C1, with a permeability of 1.96 mD, has the lowest permeability among the three samples. The slice reveals that pore types are primarily intergranular micro-fractures, intergranular matrix pores, and a limited number of intragranular dissolution pores. Locations with significant changes after water flooding are highlighted with yellow and red dashed lines. Positions 1 and 2, which contained well-developed gravel-edge fractures before flooding, exhibited almost complete fracture closure after water flooding. At Position 3, intergranular pores were present before water flooding, with debris visible at the arrow-marked location. After flooding, the debris had disappeared, indicating particle migration. Fracture closure and particle migration are two key mechanisms contributing to permeability sensitivity. Notably, not all porous regions were affected by water flooding. For example, the gravel-edge fracture in the lower-right section of the slice showed no significant change in morphology or aperture. The areal porosity of the C1 sample slice decreased from 4.376% before flooding to 3.686% afterward.

Figure 7 displays a representative slice (the 611th slice along the z-axis) from the sample C2 dataset. With a permeability of 11.22 mD, sample C2 exhibits a greater abundance of matrix pores and intergranular pores compared to sample C1, along with observable intraparticle pores. The areal porosity of the C2 slice was 14.551% before flooding and 14.127% after flooding. Additionally, the gravel particles in sample C2 are smaller than those in C1. Significant changes in pore structure can be observed in the slice. As indicated by position 1 in

Figure 7a, an intraparticle fracture connected to the intergranular matrix below shows reduced connectivity on the right side after water flooding. Fracture apertures at positions 2–6 clearly contracted but did not completely close, unlike what was observed in sample C1. In contrast, the intergranular pore at position 8 in the upper-right region, the matrix-supported intergranular fracture at position 9, and the intergranular pore at position 10 remained largely unaffected.

Figure 8 displays the 594th slice along the z-axis of the sample C3 data volume. Compared to samples C1 and C2, C3 exhibits a higher proportion of intergranular pores. The areal porosity was 17.9% before water flooding and 17.7% afterward. Apart from the closure of the intergranular fracture within the yellow frame at Position 1, only minor changes were observed in the intergranular fractures, intergranular pores, and intragranular pores at Positions 2 to 4.

From these slice examples, it can be concluded that samples across the three permeability ranges all undergo certain structural alterations after water flooding. These are manifested as the narrowing or closure of intergranular fractures, the reduction in aperture of dissolution pores within the matrix, and the migration of debris inside some pores. It is noteworthy, however, that even in low-permeability samples, some pores remain largely unaffected by the flooding process.

3.3.2. Statistical Analysis of Pore Structure Network

Using 2D slice samples, specific instances of pore structure alterations in the three samples were analyzed before and after water flooding, clarifying the types of pore changes that occurred. However, to assess how the overall pore parameters of the core evolve, further statistical analysis integrated with PNM is required. The specific results are presented in

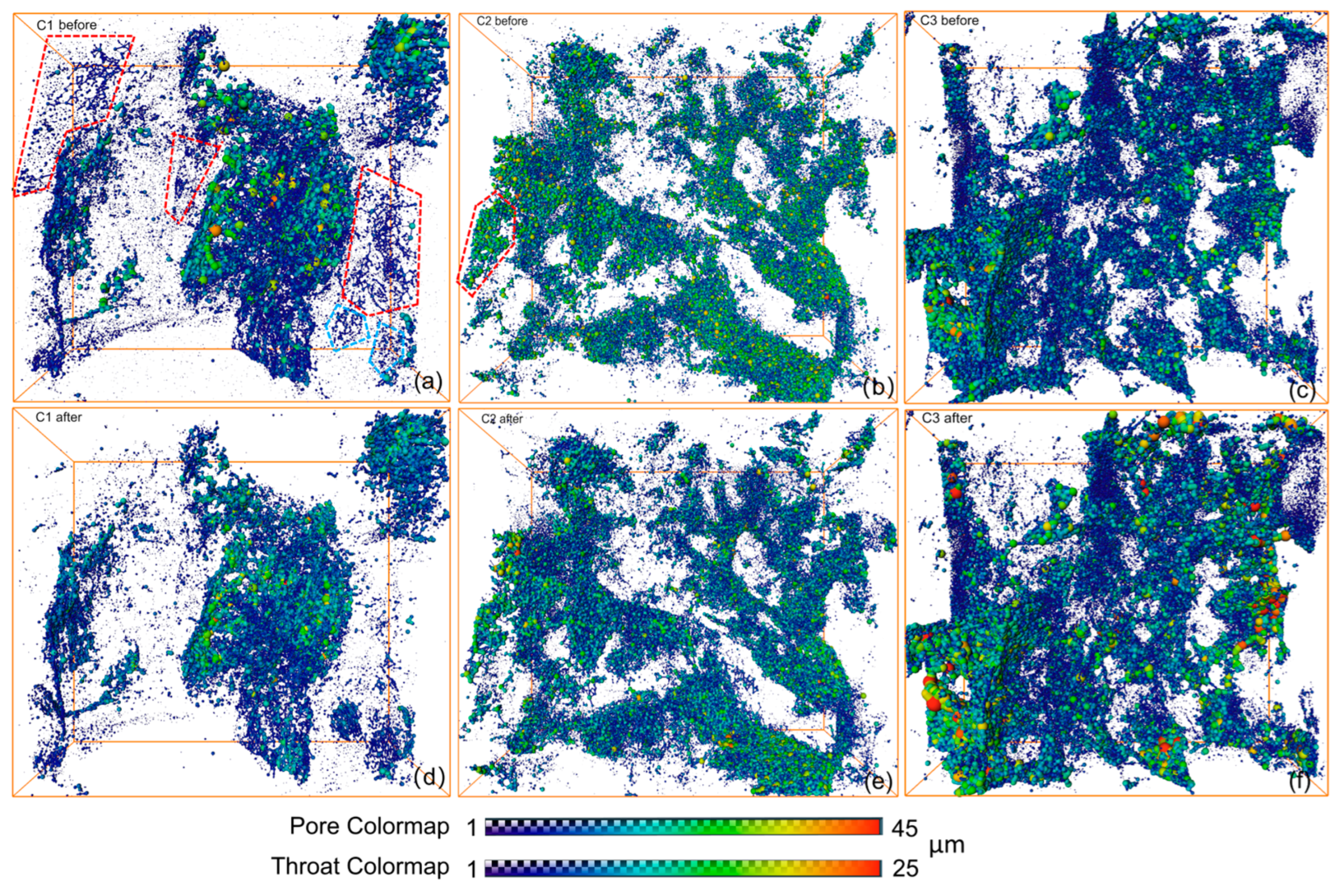

Figure 9, with pore and throat sizes represented by color mapping.

Comparison of the PNM before and after water flooding reveals that in sample C1, large sections of the pore network closed or disappeared after flooding (as indicated by the red dashed box in

Figure 9a,d. The overall pore network also became sparser, indicating a significant reduction in the total number of pores. In sample C2, partial closure occurred in the local pore network on the left side (within the red dashed box in

Figure 9b,e, and the number of pores decreased moderately in certain regions after flooding. In contrast, sample C3 exhibited no significant pore closure or disappearance after water flooding.

It is worth noting that in sample C1, local enhancements in network connectivity and an increased number of pores were observed in the lower-right region, as marked by the light blue dashed box in

Figure 9a. Additionally, in areas originally characterized by clustered pores and strong connectivity, some pores exhibited enlarged apertures after flooding, manifested as expanded yellow and red regions in the central pore network. However, such changes were not observed in sample C2. The pore distribution in sample C2 was more homogeneous compared to C1, and the overall connectivity of the pore network was better. Instead, a more general reduction in pore throat sizes was observed across the network after flooding, reflected by a noticeable decrease in yellow and red regions. In sample C3, the overall extent and structure of the pore network remained largely unchanged. Nevertheless, a trend of pore enlargement was still discernible, particularly in regions that originally consisted of larger pores. This was evidenced by the significant expansion of yellow and red regions in the pore network after flooding (as shown in

Figure 9c,f).

These changes in PNM suggest that damage to the pore structure during water flooding may be more pronounced in non-main flow channels. In major flow pathways, in contrast, scouring by fluids and the dislodgment of particles may lead to localized enlargement, especially in regions subjected to sustained fluid flow. In sample C2, which exhibits a relatively uniform pore network, pore enlargement due to high-permeability channel flushing is less evident. Instead, the dominant trend is a contraction in pore scales across the network.

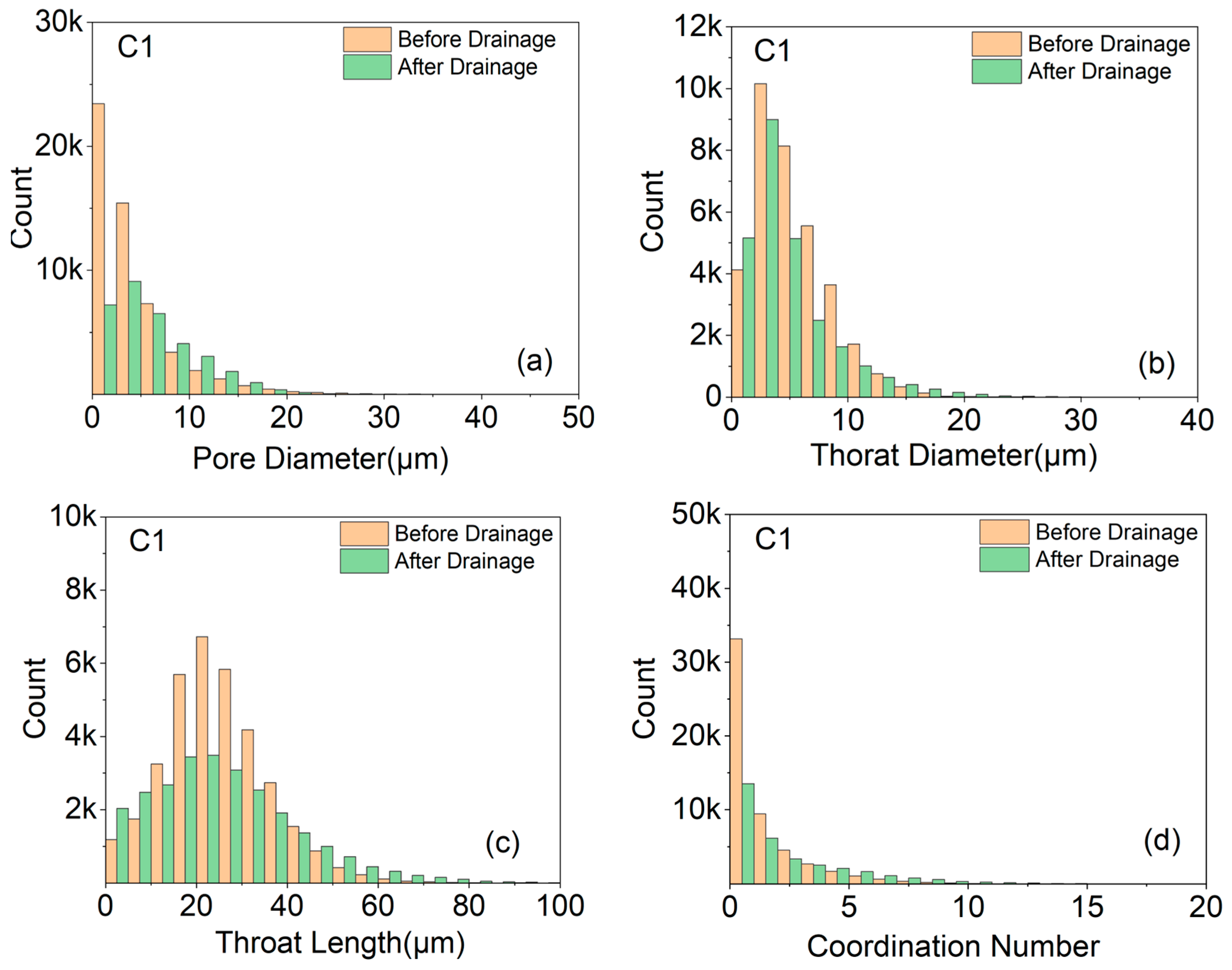

To further refine the changes in pore network parameters of the three samples before and after water flooding, the pore size, throat size, coordination number, and throat length of the PNM networks were statistically analyzed. The results of sample C1 are shown in

Figure 10.

As shown in

Figure 10a, the total number of pores in sample C1 decreased significantly after water flooding. Pores smaller than 7 μm showed a notable reduction, especially those under 2 μm, which decreased by more than 50%. In contrast, the number of pores larger than 7 μm increased slightly, though the overall growth was limited. As illustrated in

Figure 10b, the number of throat diameters larger than 3 μm decreased markedly after water flooding, while throats smaller than 3 μm exhibited a slight increase in count. Regarding throat length, as shown in

Figure 10c, the overall trend post-flooding showed a decline in the number of throats with lengths between 13 and 47 μm, with a particularly significant reduction in those measuring 18–33 μm. In comparison, shorter throats (<8 μm) and longer throats (>48 μm) increased in number. Notably, throats longer than 56 μm more than doubled, though they account for a very small proportion of the total throat population. In terms of coordination number, as shown in

Figure 10d, the number of pores with coordination numbers below 4 decreased significantly, with a reduction of over 50% for pores having coordination numbers under 2. Pores with coordination numbers above 6 experienced a modest increase.

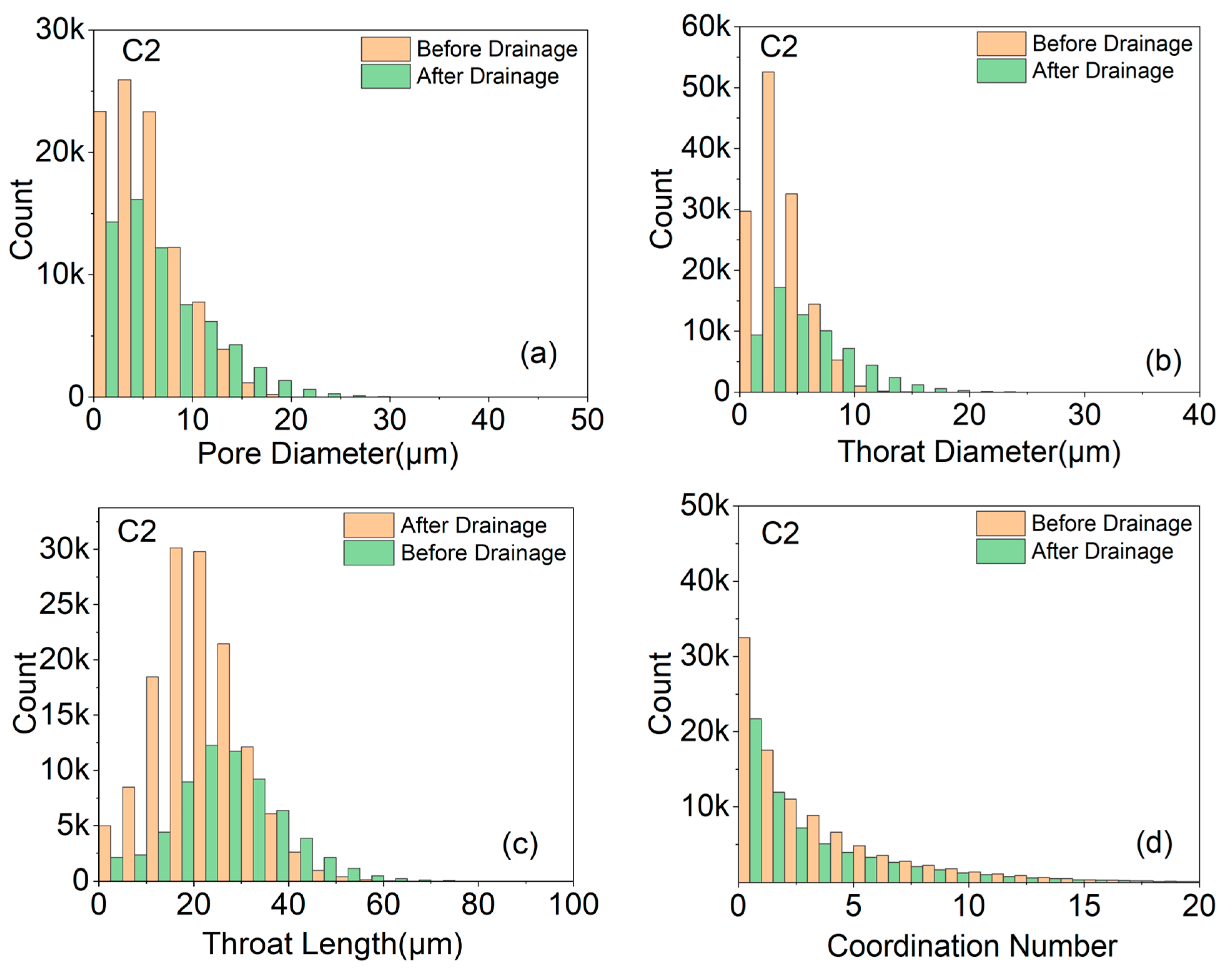

Based on the relationship between permeability and sensitivity discussed in the previous section, sample C2 is classified as a moderately water-sensitive sample. As shown in

Figure 11a, the total number of pores and throats in sample C2 is significantly higher than that in sample C1. In addition, the throat length and average coordination number of sample C2 are considerably better than those of C1. Nevertheless, the overall variation in pore network parameters after water flooding is generally similar between samples C2 and C1. In terms of the total number of pores across different scales,

Figure 11a shows that after water flooding, both samples exhibit a substantial decrease in the number of small pores. Specifically, the total number of pores smaller than 7 μm decreased markedly in sample C1, while the reduction in sample C2 was more pronounced for pores below 10 μm. In contrast, a slight increase was observed in the number of pores larger than 10 μm.

Regarding throat size changes, as shown in

Figure 11b, sample C2 exhibited a significant decrease in the number of throats smaller than 7 μm after flooding, with those around 4 μm decreasing by more than 50%. Conversely, the number of throats larger than 7 μm showed a noticeable increase. Furthermore, the maximum throat size in sample C2 increased from approximately 13 μm before flooding to about 20 μm after flooding. In terms of throat length variation, as shown in

Figure 11c, the changes before and after flooding were also pronounced in sample C2 compared to C1. The variation in C2 was bounded around 40 μm: the number of throats shorter than 40 μm decreased significantly, while those longer than 40 μm increased to some extent. As for the coordination number, as shown in

Figure 11d, almost all pores across different coordination values experienced a certain degree of reduction after flooding. Pores with coordination numbers below 5 decreased relatively significantly, while those with coordination numbers above 5 underwent only minor changes.

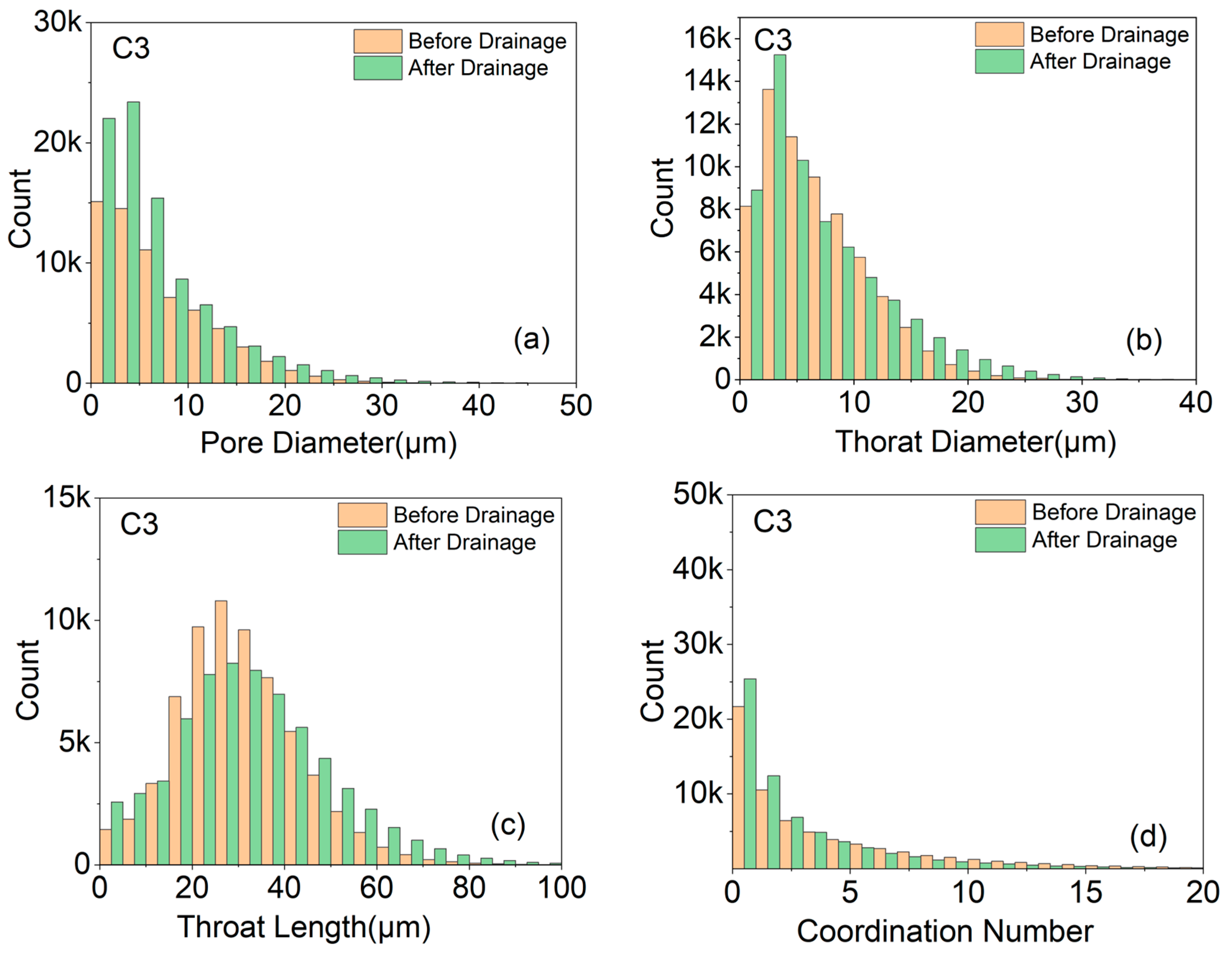

For the weakly water-sensitive sample C3, changes in pore size, throat size, throat length, and coordination number were still observed before and after water flooding, as detailed in

Figure 12. The variation trends are entirely distinct from those of the strongly and moderately water-sensitive samples. After flooding, the weakly water-sensitive sample exhibited an increasing trend in the number of pores below 10 μm, while the quantity of pores larger than 10 μm remained almost unchanged (

Figure 12a). In terms of throat characteristics, as shown in

Figure 12b, the number of throats smaller than 5 μm and larger than 15 μm increased after water flooding, whereas throats within the 5–10 μm range showed a slight decrease. Regarding throat length, as shown in

Figure 12c, the number of throats shorter than 15 μm and longer than 40 μm increased, while a relatively noticeable reduction occurred in throats with lengths between 15 μm and 40 μm.

As for the coordination number, as shown in

Figure 12d, a slight increase was observed in the number of throats with coordination numbers below 3 after water flooding. In contrast, the overall number of pores with coordination numbers above 3 underwent negligible change.