5.1. Model Construction and Performance

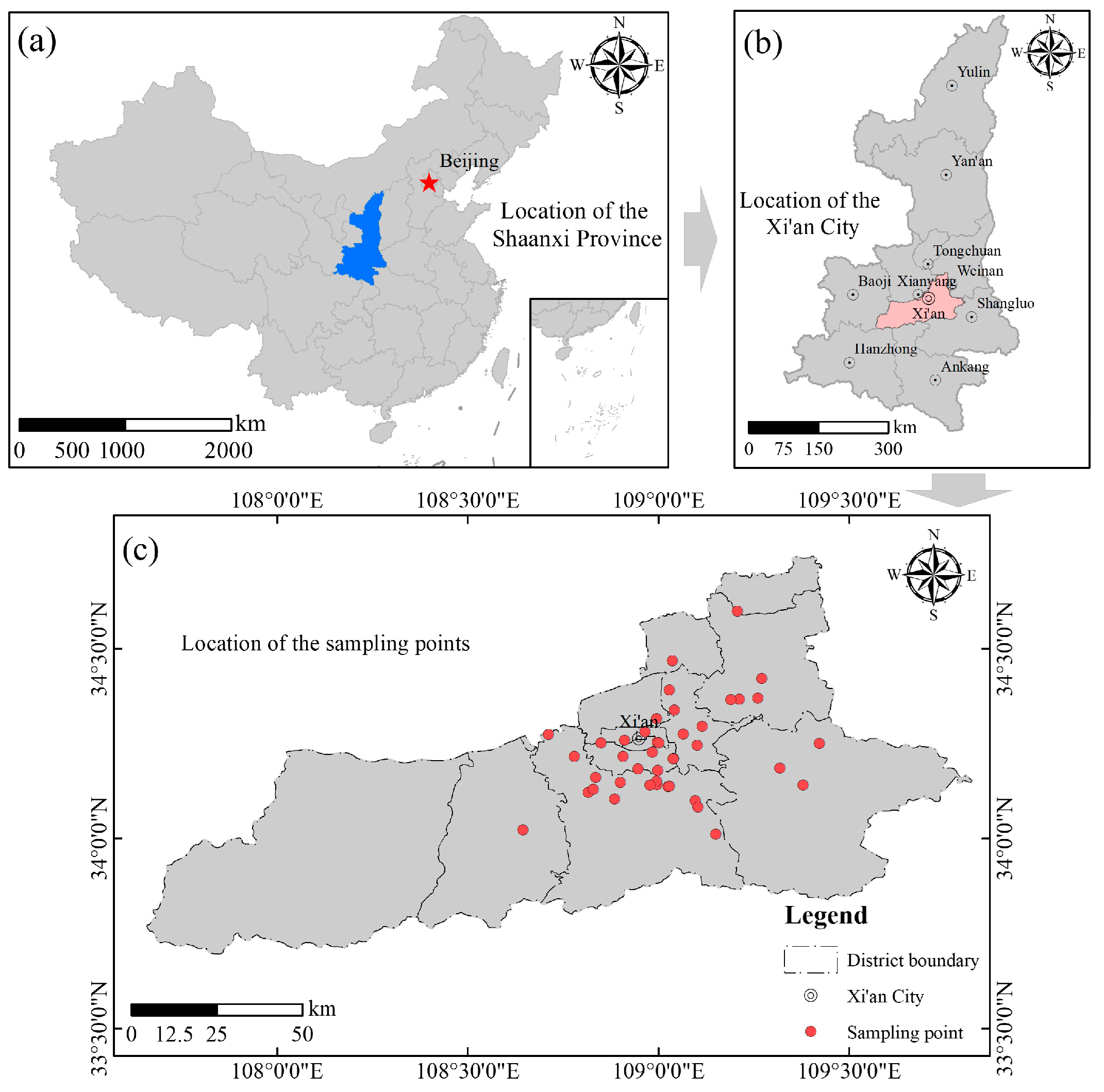

In engineering projects in the Xi’an region, the collapsibility of loess must be carefully considered, as inaccurate assessment can result in severe geological hazards [

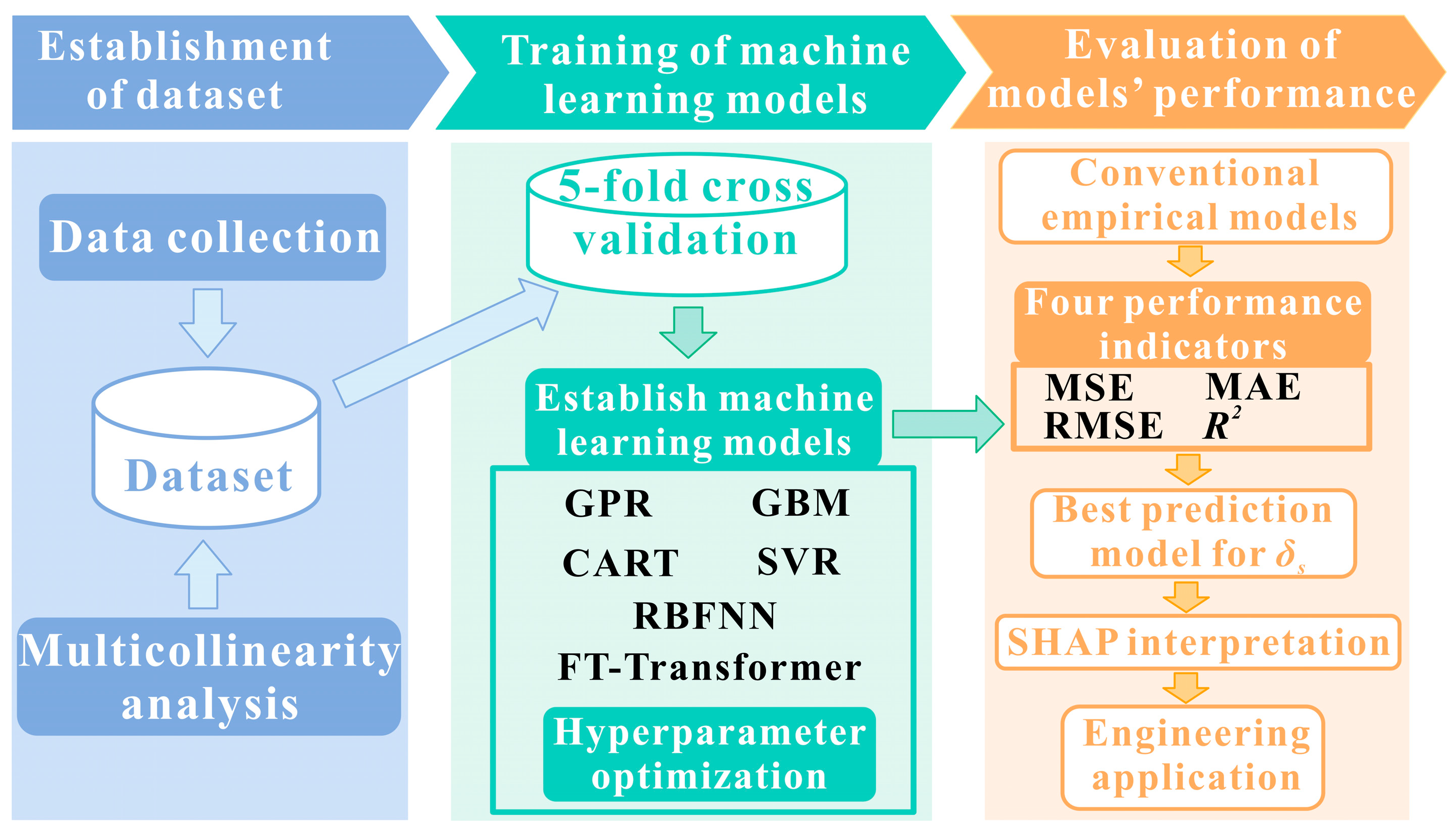

49]. In this study, multicollinearity analysis was conducted to identify suitable physical indices for machine learning modeling [

50,

51]. The results indicated that the variance inflation factors (VIFs) of natural density (

ρ), dry density (

ρd), initial void ratio (

e0) and liquid limit (

wL) were relatively high. From a geotechnical perspective, liquid limit (

wL), as a key indicator reflecting soil plasticity and fine particle content, exhibits intrinsic functional relationships with plastic limit (

wP) and plasticity index (

IP). Similarly, the significant multicollinearity observed among natural density (

ρ), dry density (

ρd), and initial void ratio (

e0) is physically reasonable. Specifically, dry density (

ρd) can be derived from natural density (

ρ) and water content (

w), while initial void ratio (

e0) is closely related to dry density (

ρd) and can be calculated from dry density and particle specific gravity. Consequently, these three variables essentially describe the same aspects of soil pore structure, resulting in strong redundancy and elevated VIF values. From a modeling standpoint, strongly correlated variables should be avoided to reduce redundant information and improve model stability.

To validate the rationality of the multicollinearity analysis, this study employed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for comparison. PCA extracted three principal components, denoted as

Y1,

Y2, and

Y3. The results are summarized in

Table 9, where all soil physical properties were standardized prior to analysis. The cumulative variance contribution of the three principal components reached 0.82. First, the data were subjected to PCA for dimensionality reduction, and GPR and FT-Transformer models were subsequently established. The results are presented in

Table 10. Comparing

Table 10 with

Table 3, it is evident that using multicollinearity analysis to select variables achieves better model performance than PCA-based dimensionality reduction. Therefore, this study employed multicollinearity analysis for variable selection.

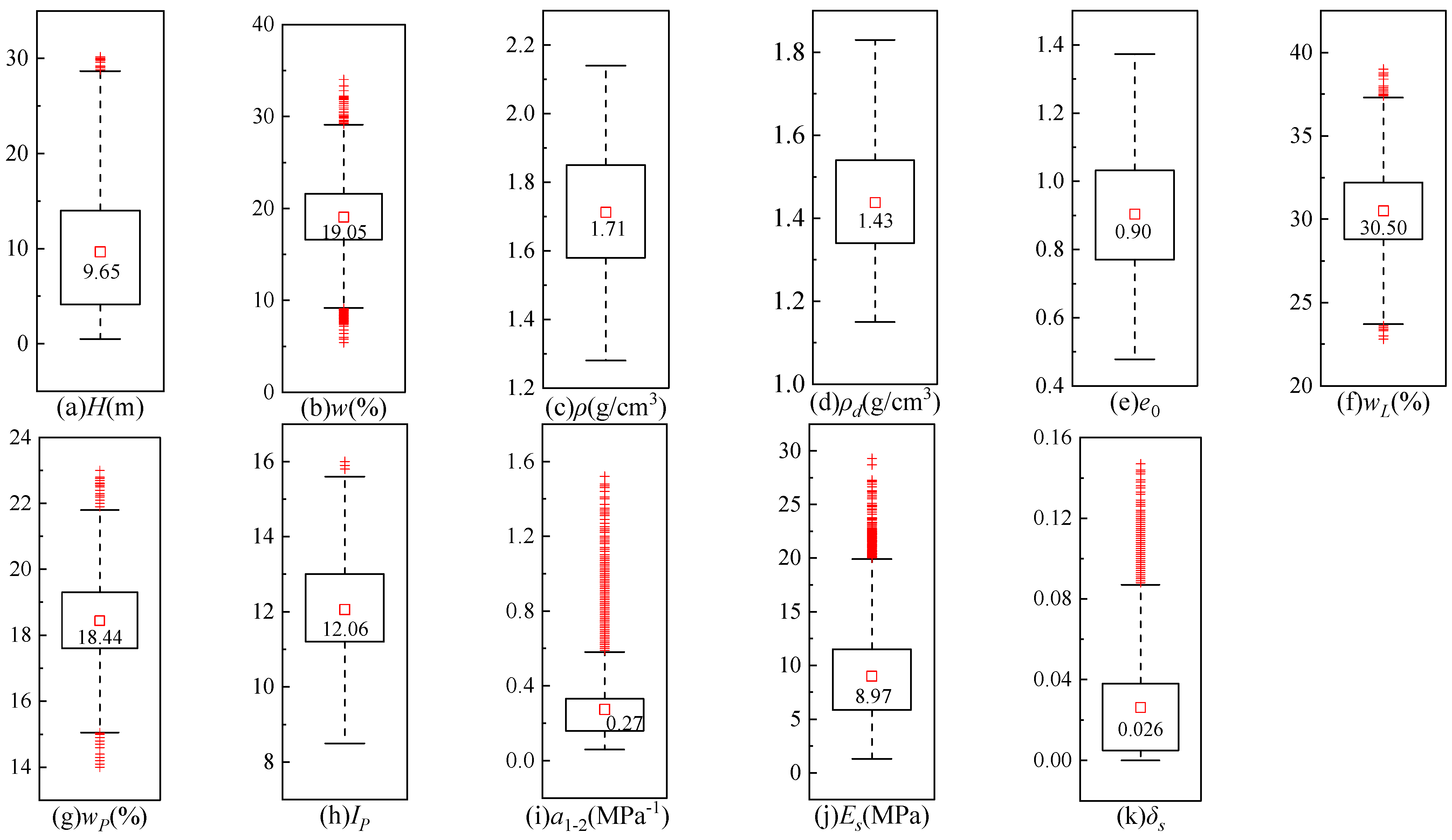

In studies predicting the loess collapsibility coefficient (δs), machine learning approaches should adopt supervised learning methods appropriate for regression tasks. To comprehensively assess predictive performance, this study employed six representative models: GPR, FT-Transformer, GBM, CART, RBFNN, and SVR. These models encompass diverse algorithmic paradigms, with GPR representing a Bayesian non-parametric method, FT-Transformer a deep learning architecture tailored for tabular data, GBM a boosting-based ensemble learning method, CART a decision tree algorithm, RBFNN an artificial neural network, and SVR an extension of support vector machines for regression. By selecting models across these categories, this study enables a systematic comparison of their effectiveness in predicting the loess collapsibility coefficient (δs).

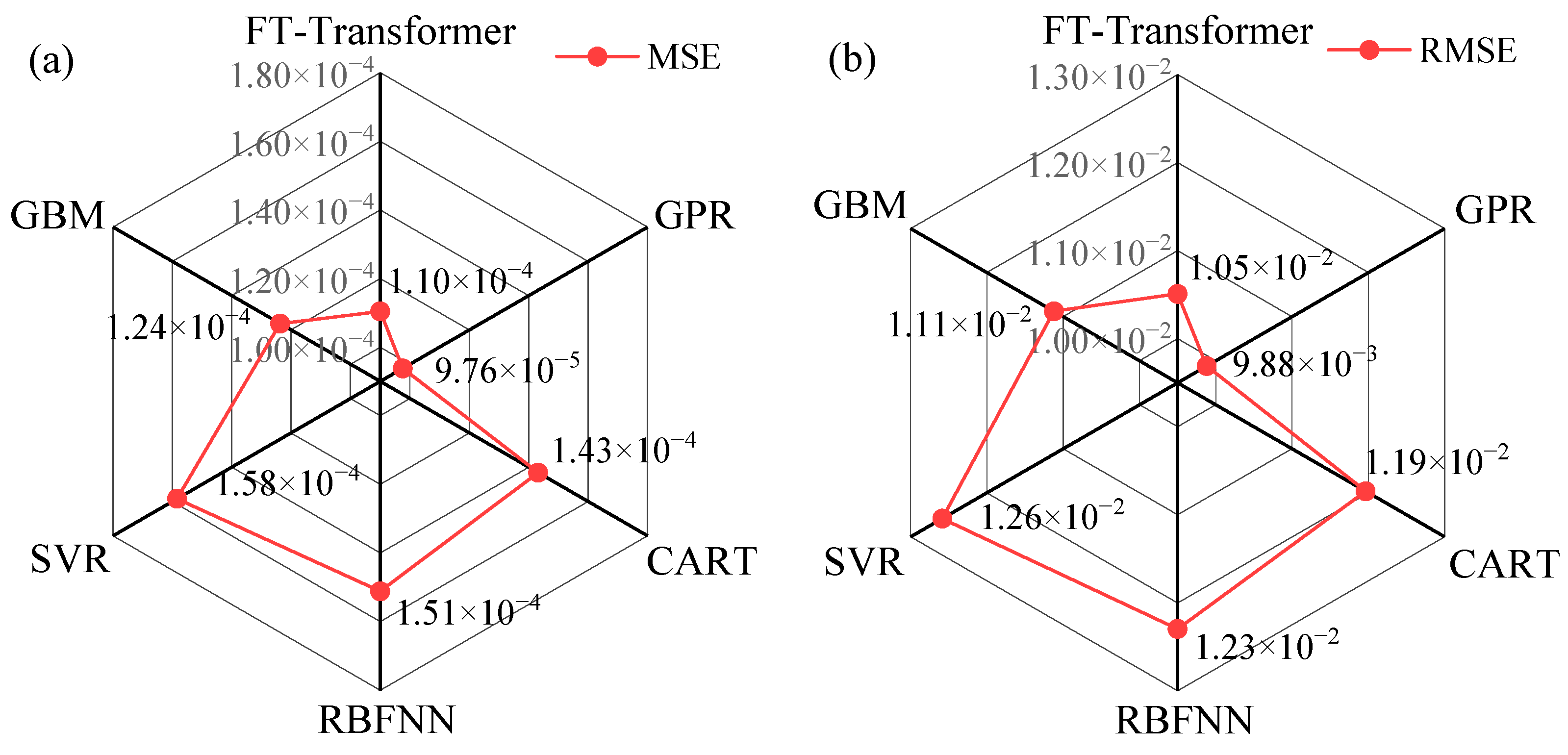

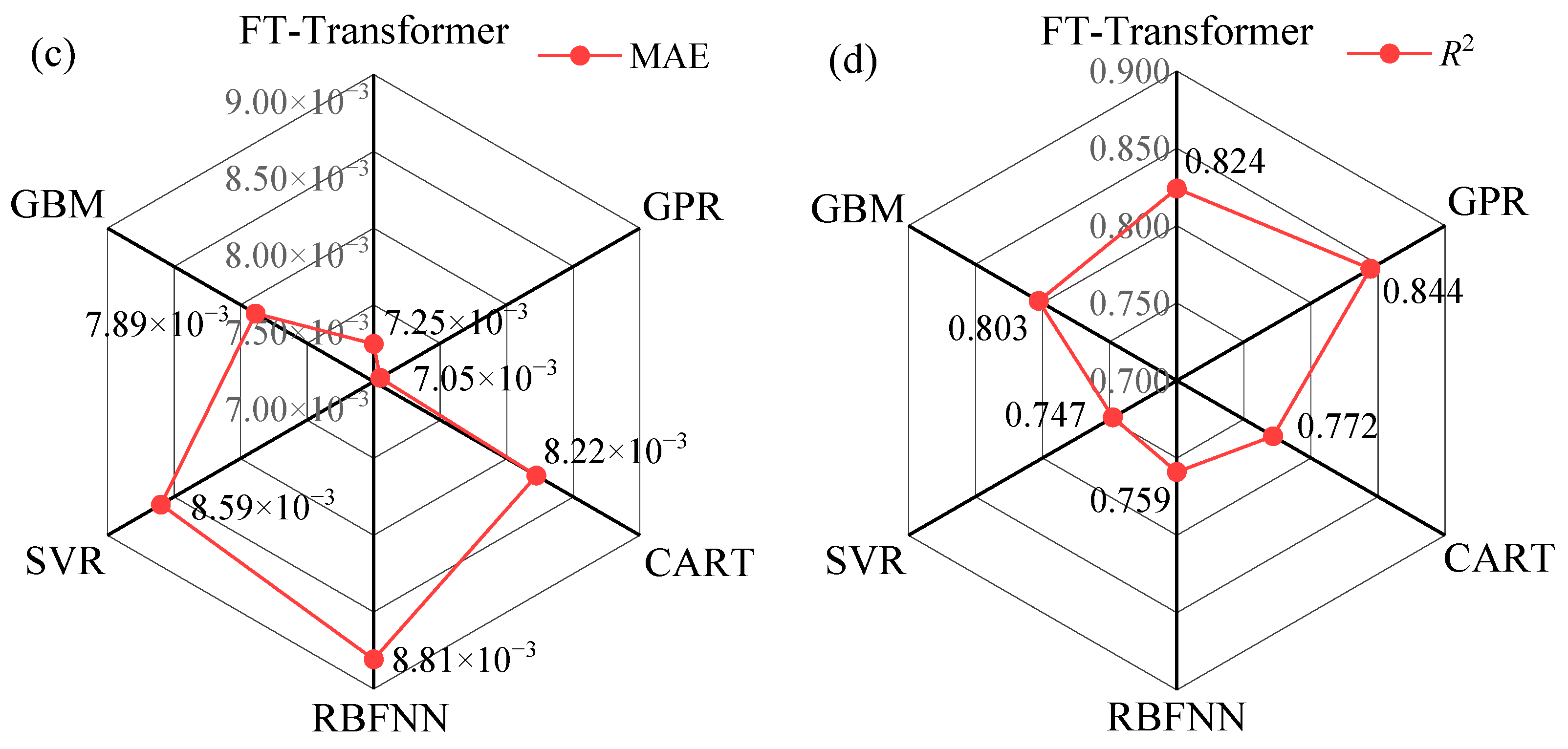

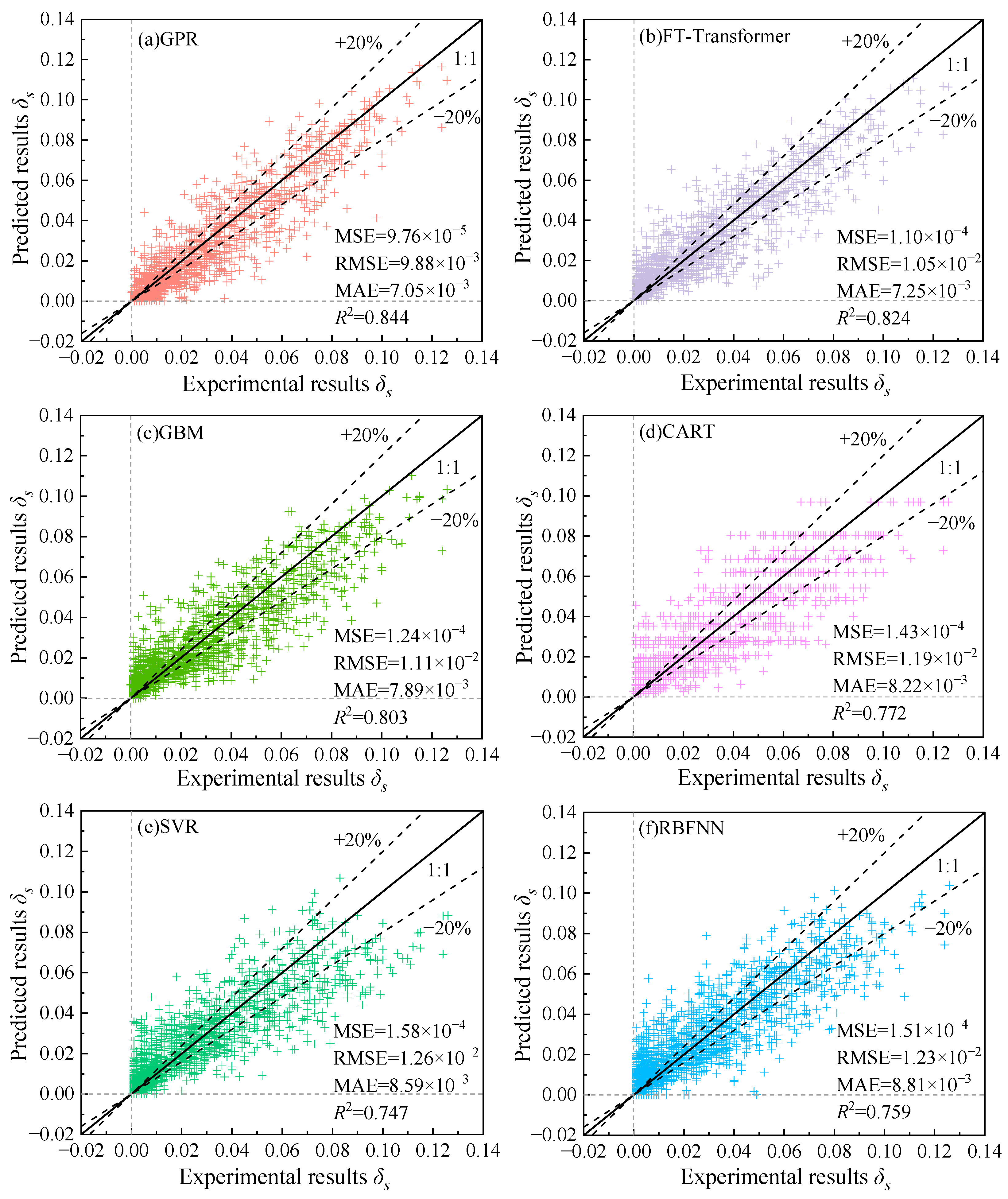

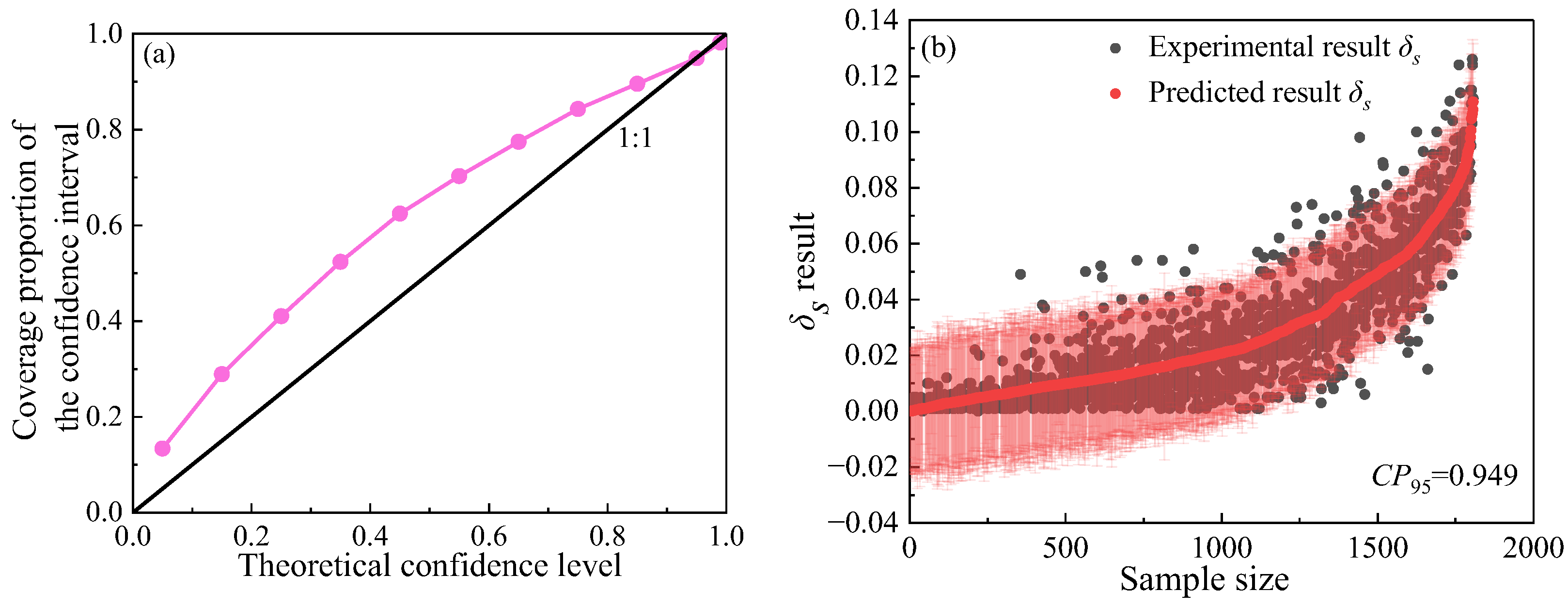

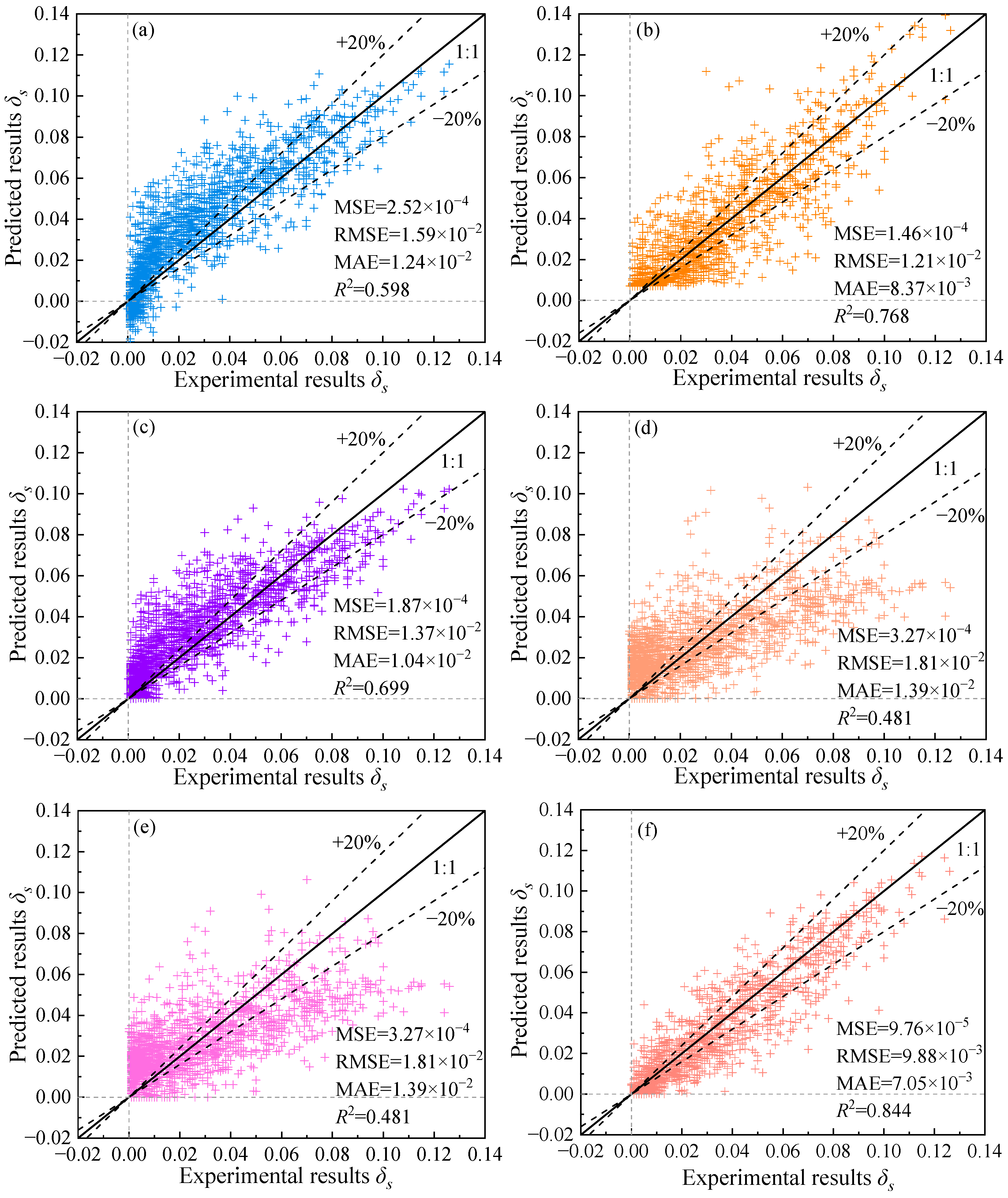

Based on the prediction results, GPR, as a non-parametric learning method, achieved the smallest prediction errors and the highest coefficient of determination (

R2). Additionally, the coverage proportion of the 95% confidence interval (

CP95) reached 0.949. The results indicate that non-parametric approaches are more suitable for predicting the loess collapsibility coefficient (

δs). From the calibration results, the actual coverage rates of the GPR model at various confidence levels are very close to the theoretical values, indicating that its uncertainty estimation is reliable. At lower confidence levels, the actual coverage is slightly higher than the theoretical expectation, suggesting that the model is somewhat conservative and produces slightly wider confidence intervals. This conservatism is beneficial in engineering applications, as it helps prevent the model from underestimating the risk of collapse, thereby improving the safety and reliability of geotechnical designs. This reliable uncertainty quantification can directly enhance safety in engineering design. Since

CP95 = 0.949, the upper bound of the 95% predictive confidence interval can be used as a safety reference in design. This approach is equivalent to adding a safety margin to the GPR model predictions, thereby incorporating model uncertainty into the engineering design’s safety factor. Consequently, it enables more robust risk management and control. The FT-Transformer, although a more complex deep learning architecture, achieved slightly lower accuracy than GPR. GBM, which integrates multiple base learners and iteratively reduces residual error, provided stable results, while CART produced predictions with a more regular distribution (

Figure 5d). However, this regularity reflects the limitations of its binary tree structure, which restricts generalization ability. For SVR and RBFNN, unmodified models can inevitably produce negative predictions. By constraining the output of the SVR model (Equations (3) and (4)) and applying the ReLU activation function to the output layer of RBFNN (Equation (5)), the occurrence of negative predictions was effectively suppressed. However, the overall predictive performance of these models remained suboptimal, resulting in inferior performance compared with the other models.

As the only deep learning model in this study, the FT-Transformer was further evaluated for its rationality by comparing it with a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). The main hyperparameters of the MLP included the hidden layer size, activation function, dropout rate, and learning rate. Through grid search optimization, these hyperparameters were determined to be (32, 16), ReLU, 0.1, and 0.01, respectively. The hyperparameter tuning was also conducted using five-fold cross-validation. The prediction results of the MLP are summarized in

Table 11.

By comparing

Table 11 with

Table 3, it can be observed that the FT-Transformer achieves lower error metrics (MSE, RMSE, MAE) and a higher

R2 value, indicating that its predictive performance for the loess collapsibility coefficient (

δs) surpasses that of the MLP. The collapsibility of loess is influenced by multiple interacting variables. The MLP relies on fixed hidden-layer connections for feature aggregation, which limits its ability to capture dynamic feature interactions effectively. In contrast, the FT-Transformer employs a self-attention mechanism that adaptively models complex and nonlinear relationships among features. This mechanism allows the model to automatically identify and emphasize the features that contribute most to

δs, thereby enhancing both its representational capacity and generalization performance.

The results of this study were compared with the previous researchers and with regression equations fitted using the same dataset. The results demonstrate that the GPR model achieved the highest predictive performance. A simple linear combination of soil physical indices often produced large deviations from experimental values, as the relationships between loess indices and the collapsibility coefficient (

δs) are inherently nonlinear. Consequently, the models shown in

Figure 9d,e performed poorly. In contrast,

Figure 9f shows that the predictions of GPR aligned more closely with the experimental values, while the results of the five polynomial regression models were markedly more scattered. This advantage arises because GPR, as a non-parametric regression method based on Gaussian process priors, effectively captures nonlinear dependencies between loess properties and

δs through kernel functions. Conventional polynomial regression, however, relies on a predefined functional form and adjusts only weights and bias terms, limiting its ability to represent complex nonlinear relationships. Paired t-test results revealed significant differences between the GPR model and the polynomial regression models, indicating that GPR possesses superior capability in capturing nonlinear relationships and quantifying predictive uncertainty, both of which are critical in geotechnical engineering applications. Based on the above analysis, the GPR model demonstrates a distinct advantage in evaluating the loess collapsibility coefficient (

δs), providing an effective and reliable approach with high predictive accuracy. Moreover, the comparison between polynomial regression and machine learning models underscores the potential of artificial intelligence techniques for investigating and characterizing the collapsibility of loess in the Xi’an region.

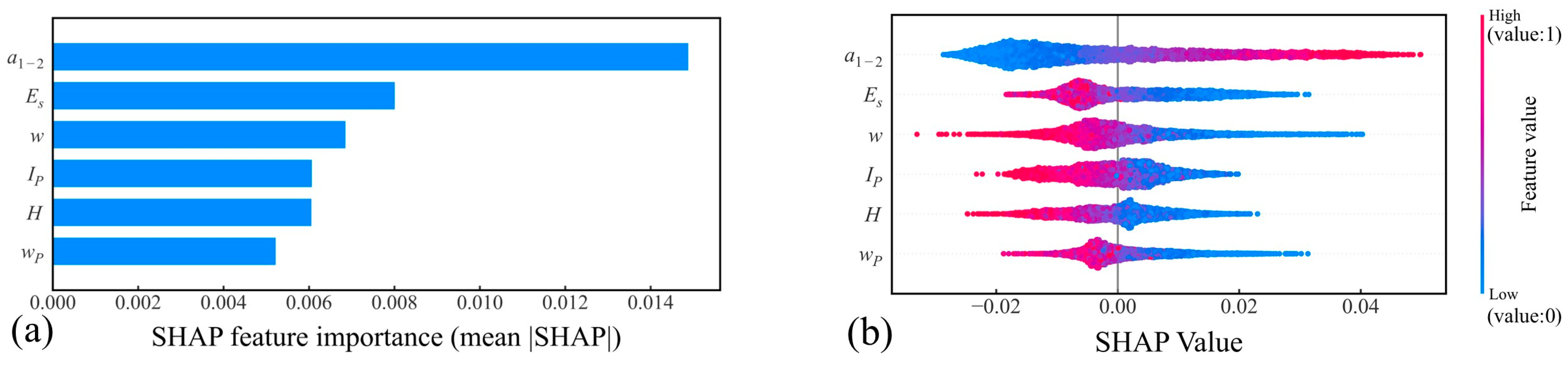

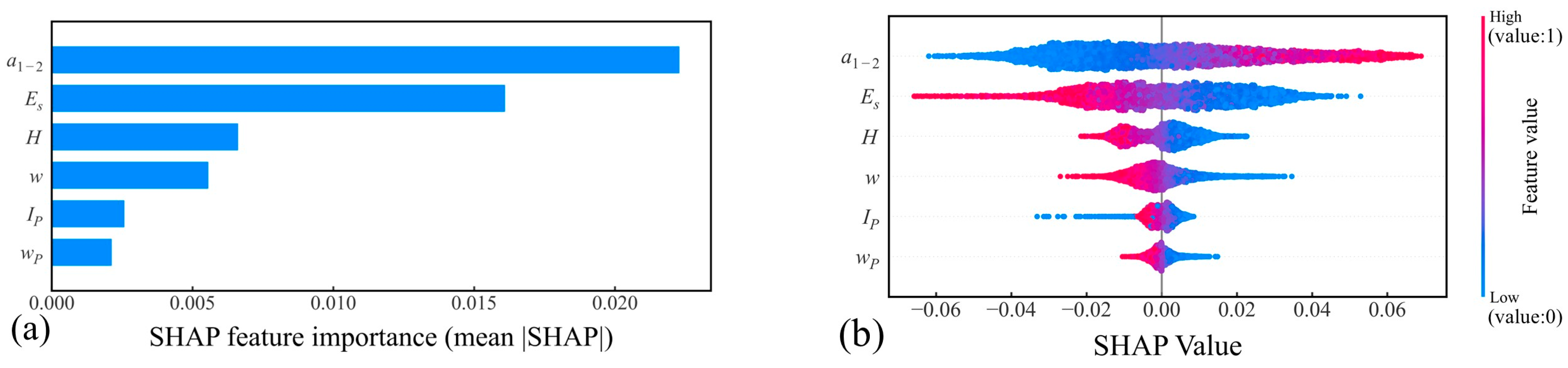

Based on

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the compression coefficient (

a1–2) and compression modulus (

Es) have the most significant influence on the collapsibility coefficient (

δs). Among them, the compression coefficient exerts a strongly positive effect. The compression modulus (

Es), sampling depth (

H), water content (

w), plastic limit (

wP) and plasticity index (

IP) negatively influence the model predictions. The compression coefficient (

a1–2) and compression modulus (

Es) reflect the loess’s resistance to compressive deformation. During the collapsibility deformation stage, cementing materials dissolve and soil particles rearrange, causing structural collapse and increased compressibility. This manifests macroscopically as an increase in the collapsibility coefficient and compression coefficient, and a decrease in the compression modulus. As sampling depth increases, soil density generally rises. Additionally, deeper soils are typically older, resulting in lower collapsibility. Generally, higher water content reduces effective stress due to increased pore water pressure, making soils with higher initial moisture softer and more deformable during the initial loading stage of laboratory tests. Consequently, higher water content is associated with reduced soil porosity, indicating a negative correlation with the collapsibility coefficient. The plasticity index represents the range of soil plasticity. Higher liquid limit and plasticity index indicate a high clay content, small pores, and a dense structure, making the soil less prone to collapsibility upon wetting. Thus, both show a negative correlation with the collapsibility coefficient. By integrating the physical interpretation of each loess property with microstructural analysis, the SHAP results can be well explained.

For both the GPR and FT-Transformer models, the compression coefficient (a1–2) and compression modulus (Es) are the most important variables, whereas the influence of the plastic limit (wP) is relatively minor. This consistency in SHAP-based feature importance indicates that the compression coefficient and compression modulus should be given particular attention when predicting the loess collapsibility coefficient (δs). The importance of water content (w), sampling depth (H), and plasticity index (IP) shows slight differences between the two models. These differences arise from the inherent structural distinctions: GPR is a non-parametric prediction method, whereas FT-Transformer is a deep learning approach. Given their fundamentally different modeling principles, variations in how they capture data patterns are to be expected.

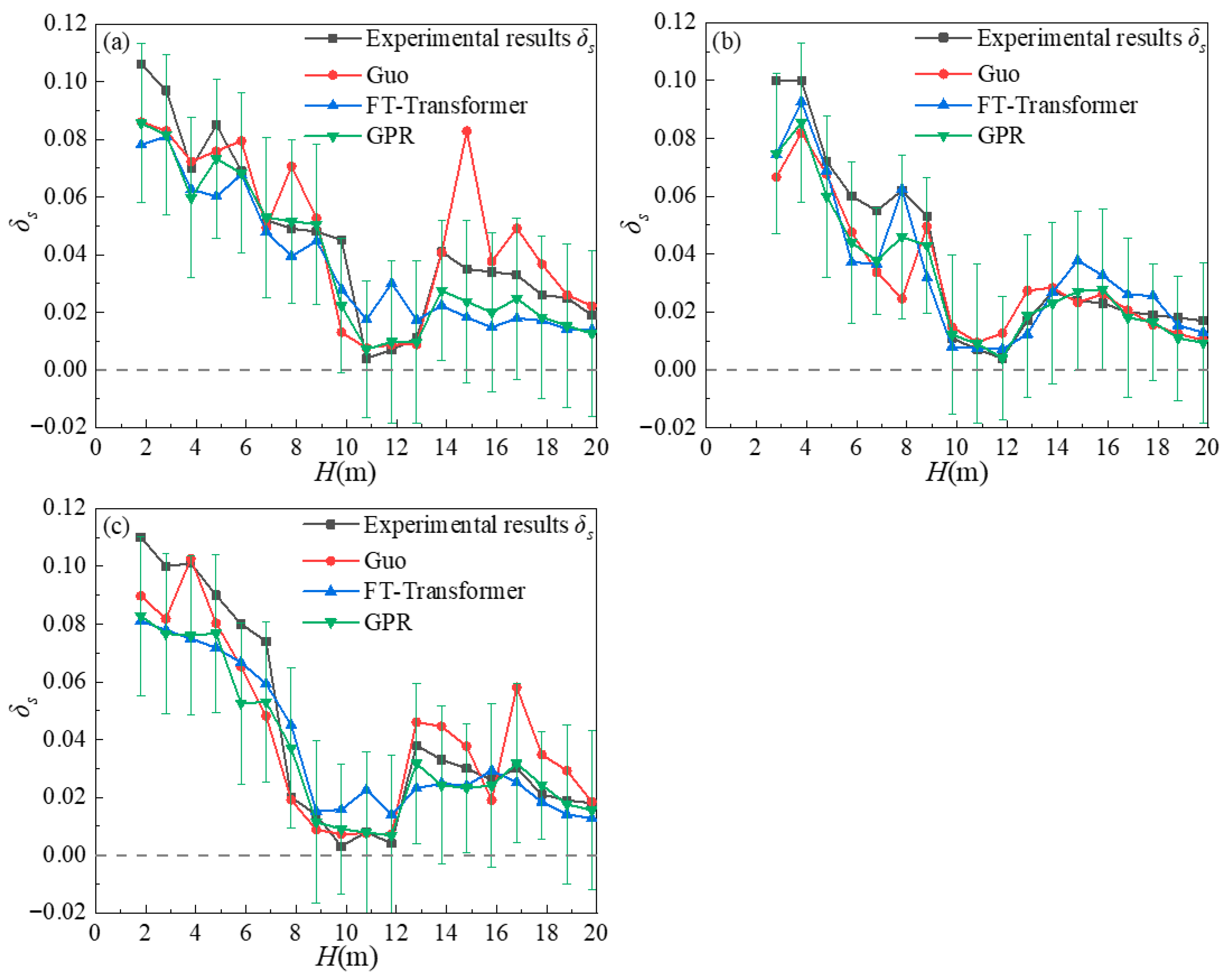

To evaluate the practical applicability of the proposed models, borehole data from a geotechnical project in Xi’an were used to compare the performance of the GPR and FT-Transformer models. In addition, a representative empirical model with relatively good performance was incorporated for comparative analysis. The results show that both GPR and FT-Transformer perform well in practical applications, outperforming the empirical model. As shown in

Figure 10, the collapsibility coefficient of loess generally decreases with increasing sampling depth. A sharp decline occurs around a depth of 12 m, after which the coefficient rises again beyond this depth. With increasing depth, the overburden stress on the soil also increases. At approximately 12 m, the self-weight consolidation of the soil reaches a relatively saturated state, leading to a significant reduction in void ratio. The soil structure becomes denser, and the interparticle bonding strengthens, resulting in a lower collapsibility coefficient. However, when the depth exceeds 12 m, the collapsibility coefficient increases again. This phenomenon can be attributed to the higher content of soluble carbonates in older loess layers, which makes the soil more prone to collapse upon wetting. The trend is consistently captured by all three methods. In terms of predictive performance, both GPR and FT-Transformer achieve better results than the empirical model, with GPR achieving slightly superior metrics overall. In engineering practice, the collapsibility coefficient is a critical parameter for calculating foundation settlement and classifying foundation treatment levels. Prediction bias in machine learning models may lead to inaccurate estimations of soil collapsibility, thereby affecting foundation design decisions. Therefore, the uncertainty of model predictions should be fully considered and transformed into a quantifiable safety margin during foundation design. For example, the design collapsibility coefficient can be determined based on the upper confidence limit derived from the predicted mean and variance. This strategy ensures structural safety while balancing construction cost and risk control, enabling a data-driven and reliable foundation design approach. The GPR model provides a stable 95% confidence interval, which encompasses all experimental

δs values. This demonstrates the higher reliability and robustness of the GPR model. Consequently, the GPR model offers valuable reference potential for practical geotechnical investigations in loess regions.