Signal Preprocessing, Decomposition and Feature Extraction Methods in EEG-Based BCIs

Abstract

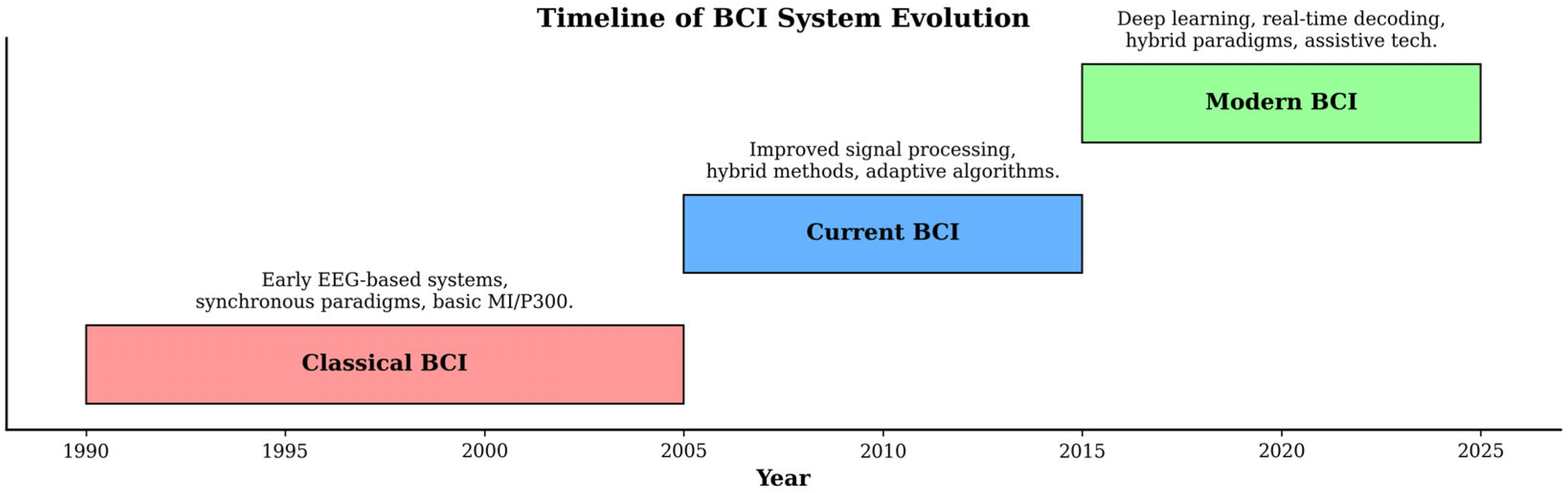

1. Introduction

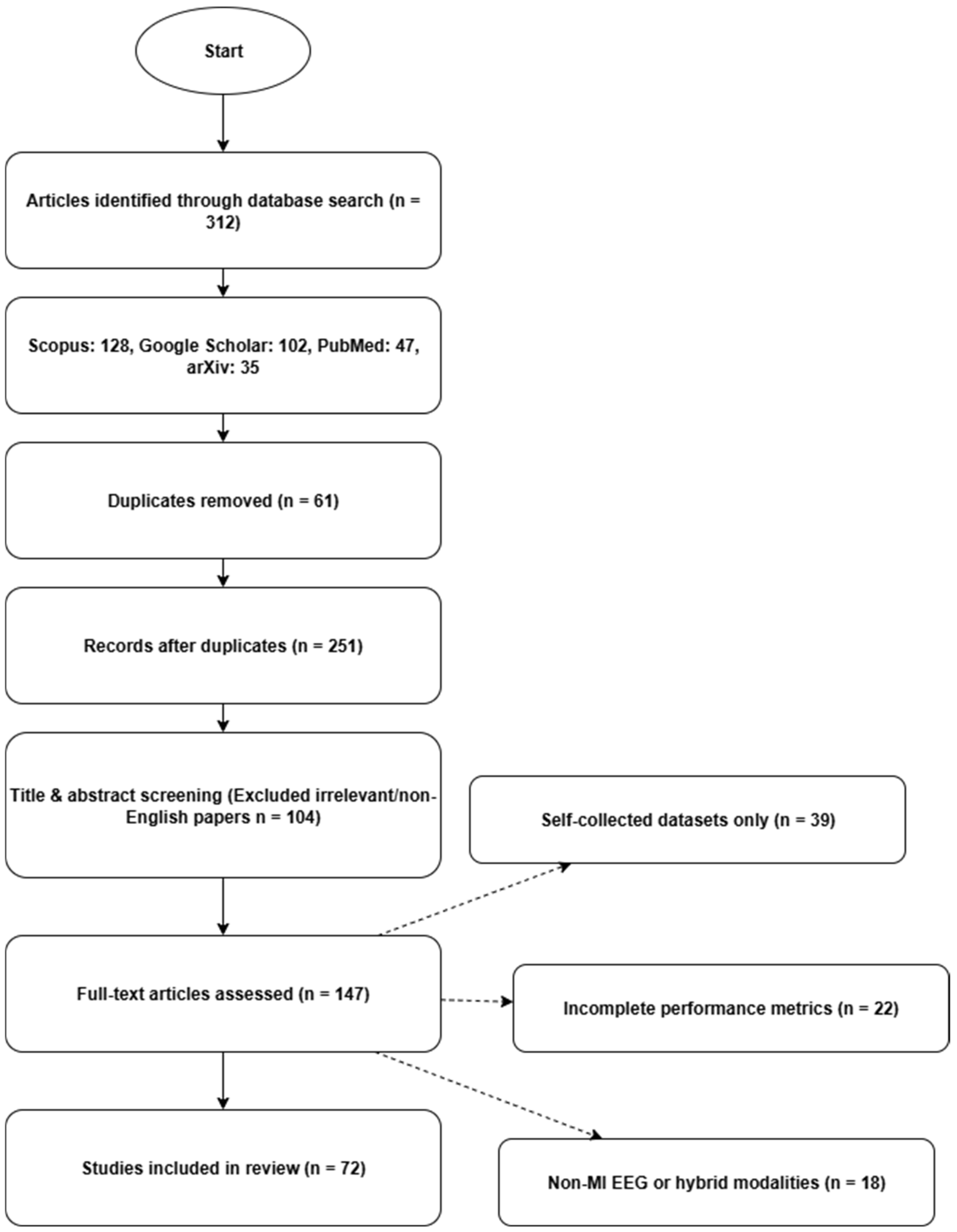

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Survey

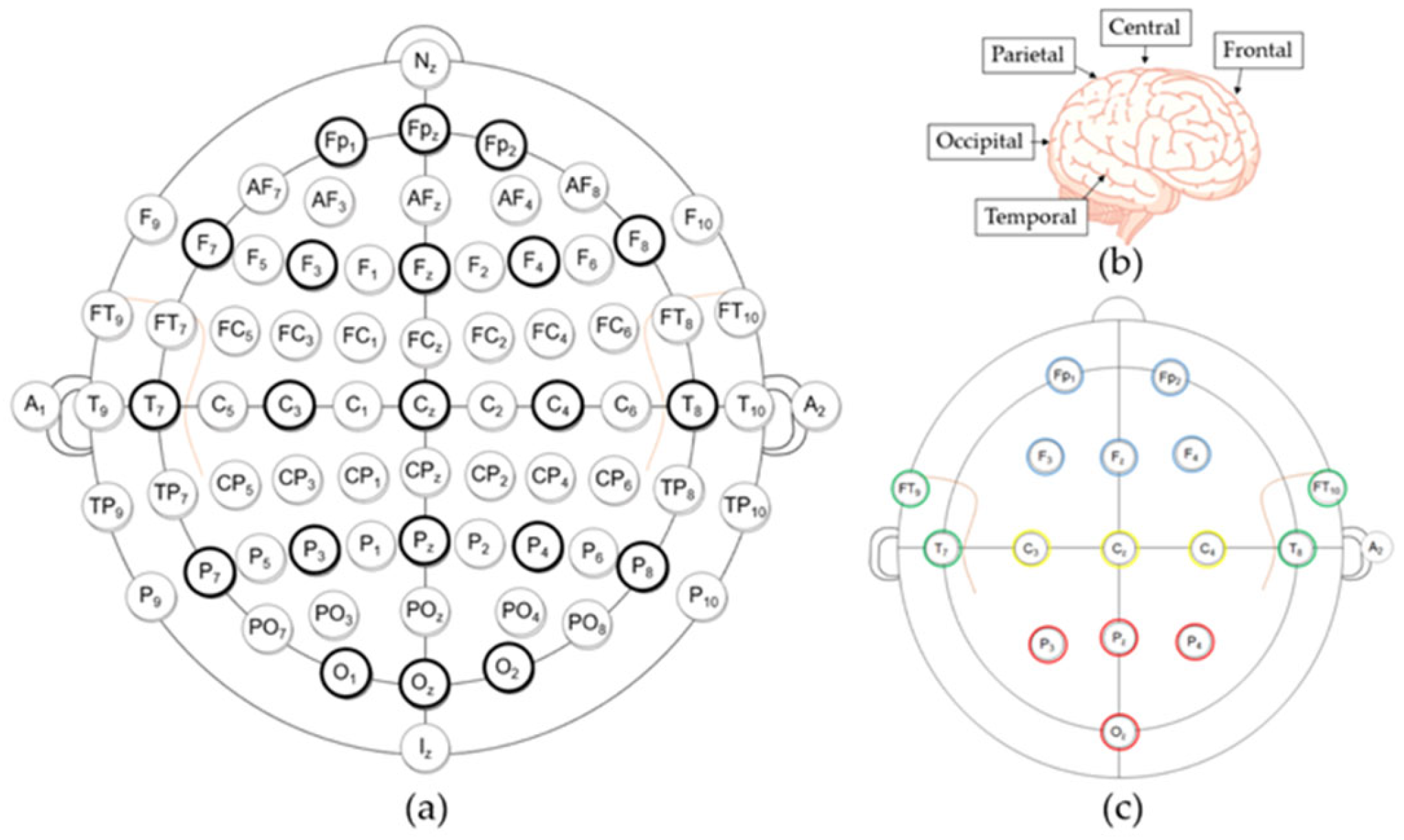

2.1.1. BCI Datasets

2.1.2. Dataset Description (Data Acquisition Details)

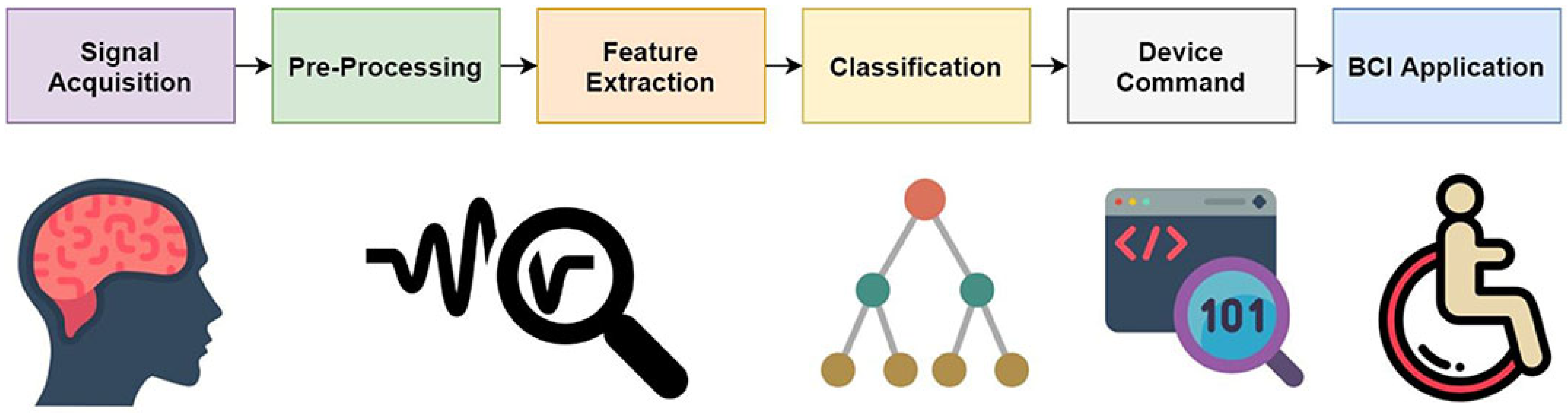

2.2. EEG Data Processing Pipeline for BCI Systems

2.2.1. Preprocessing and Decomposition

- is the recorded raw EEG signal.

- is the impulse response of the filter.

- , the filtered signal output, is only the frequencies of interest.

- is the input signal (with noise);

- is the output (filtered EEG);

- is the notch frequency;

- is the sampling rate;

- , are the feedback coefficients used to shape the EEG signal.

- is the learned filter;

- is the learning rate;

- is the error between the desired clean signal and the current output;

- is the current input signal (with noise).

2.2.2. Decomposition

2.3. Feature Extraction and Spatial Enhancement

Hjorth Parameters

2.4. Machine Learning in the EEG-Based BCI

2.4.1. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)

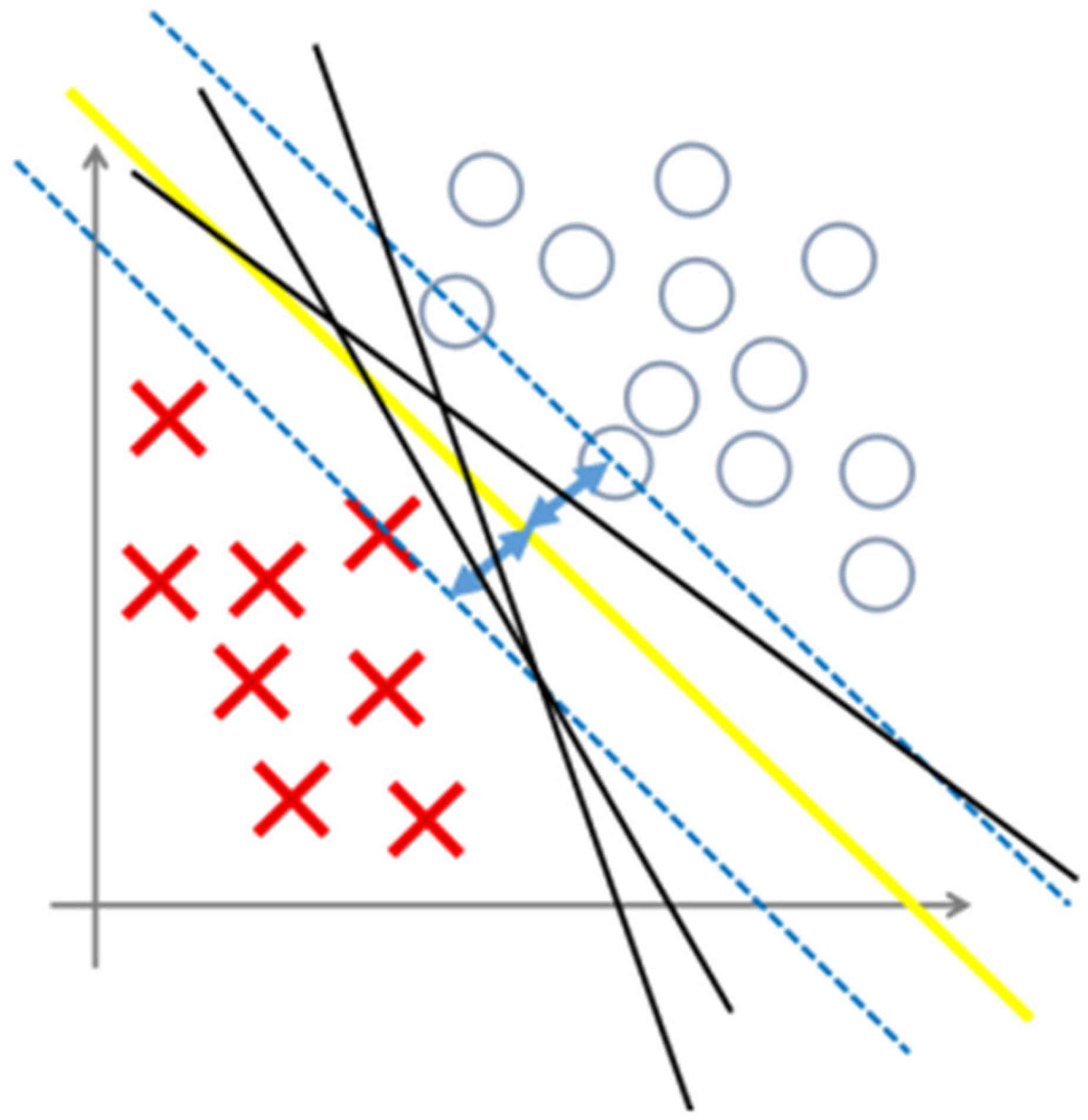

2.4.2. Support Vector Machine

2.4.3. K-Nearest Neighbors K-NN

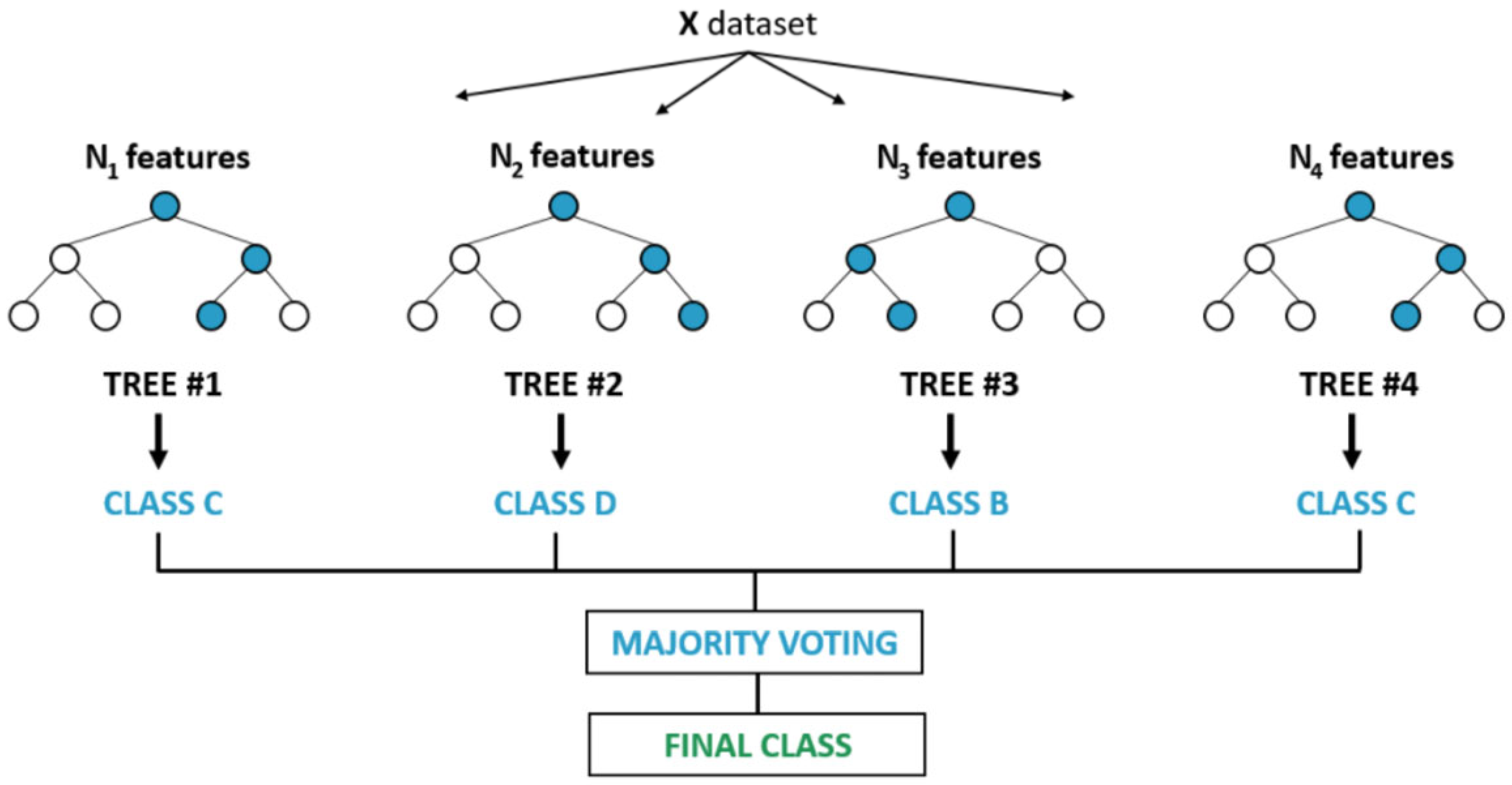

- is the prediction of the j-th decision tree.

- is the total number of trees in the forest.

- is the indicator function (1 if true, 0 if false).

2.5. Deep Learning Models in the EEG-BCI Pipeline

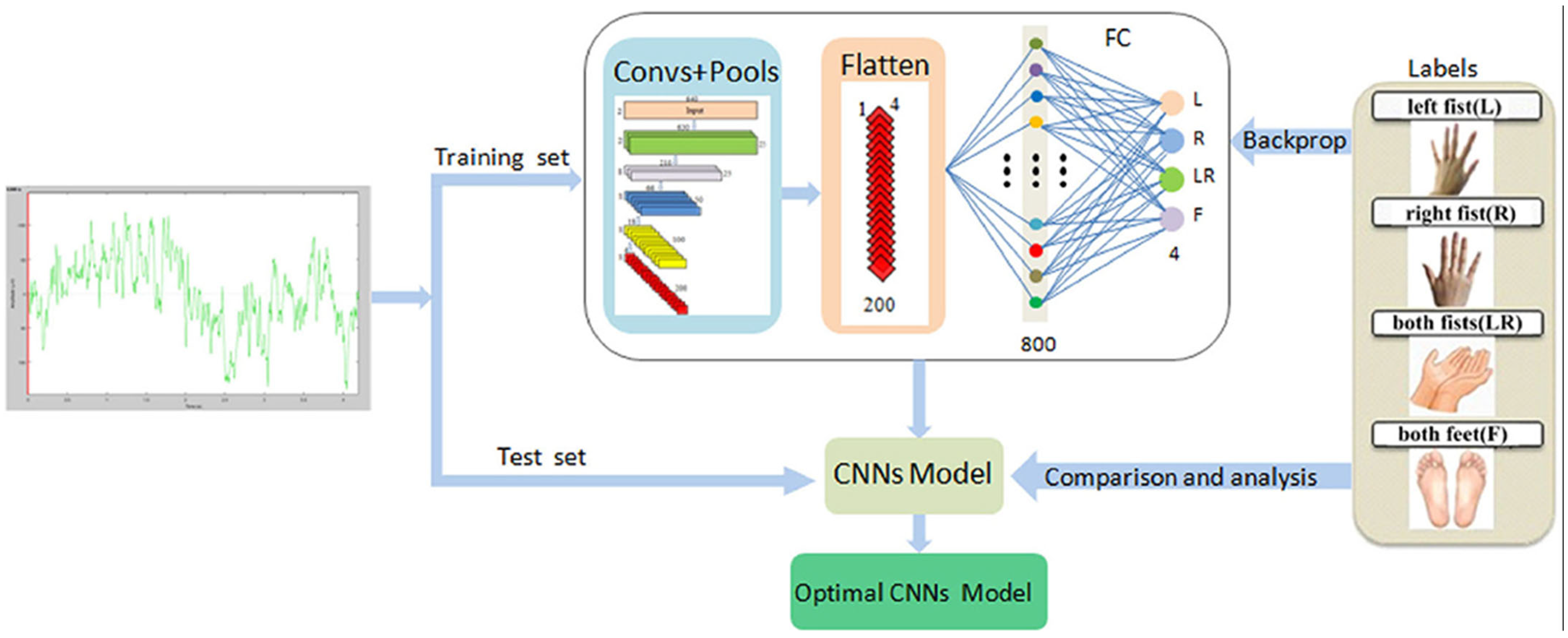

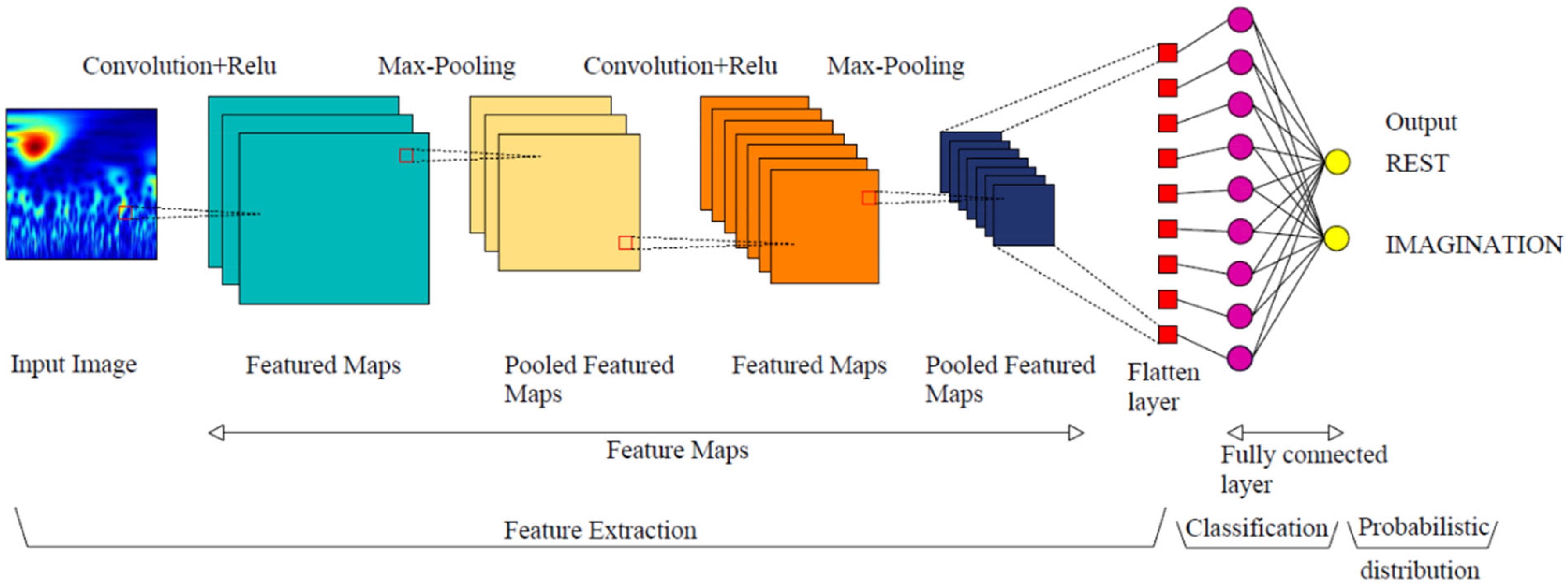

2.5.1. Convolutional Neural Network

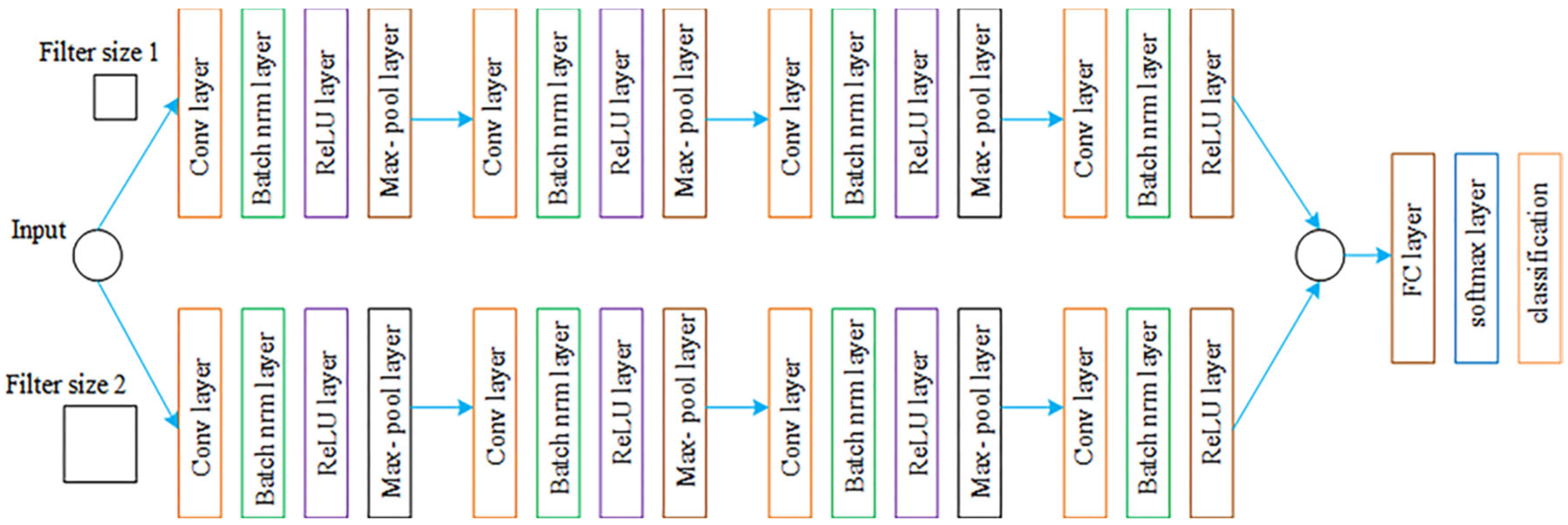

2.5.2. Parallel Convolutional Neural Network

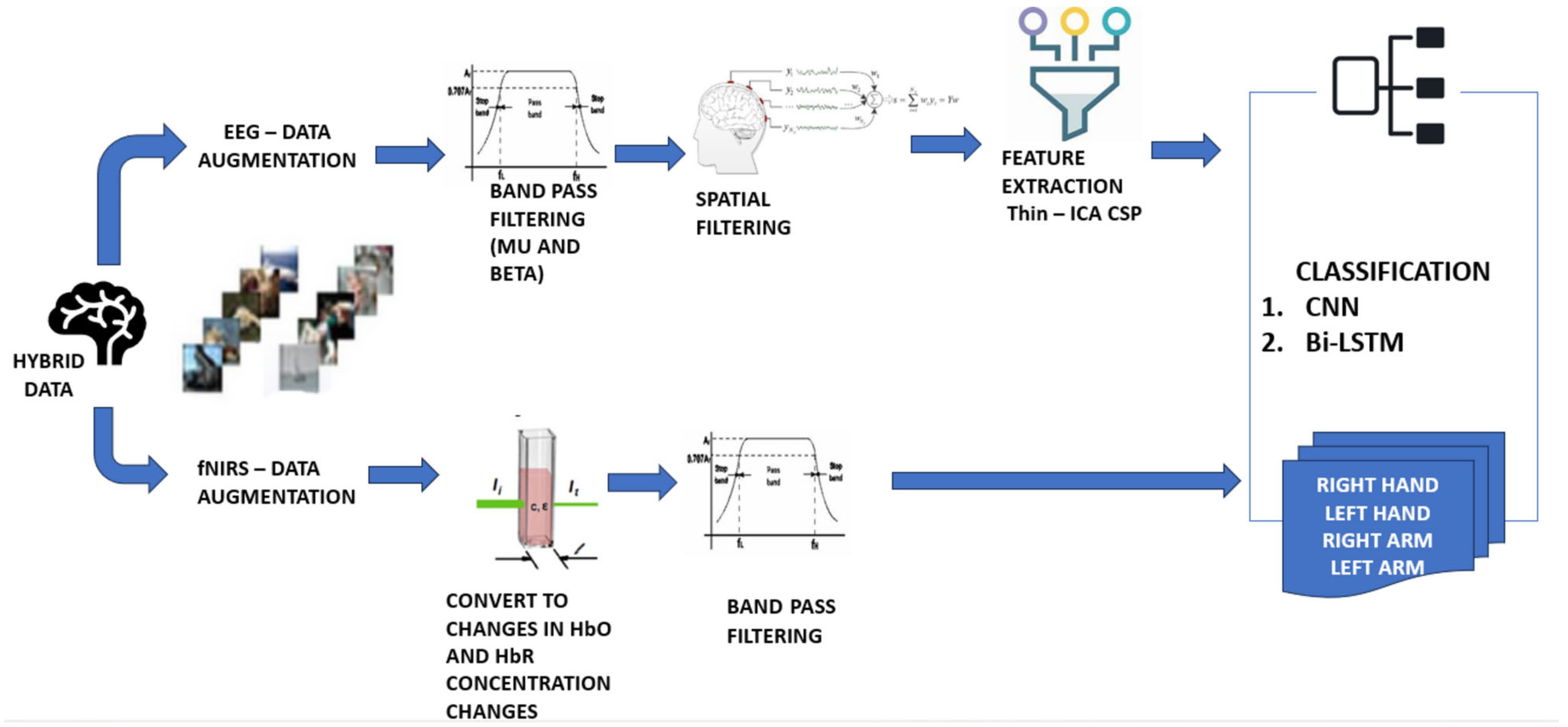

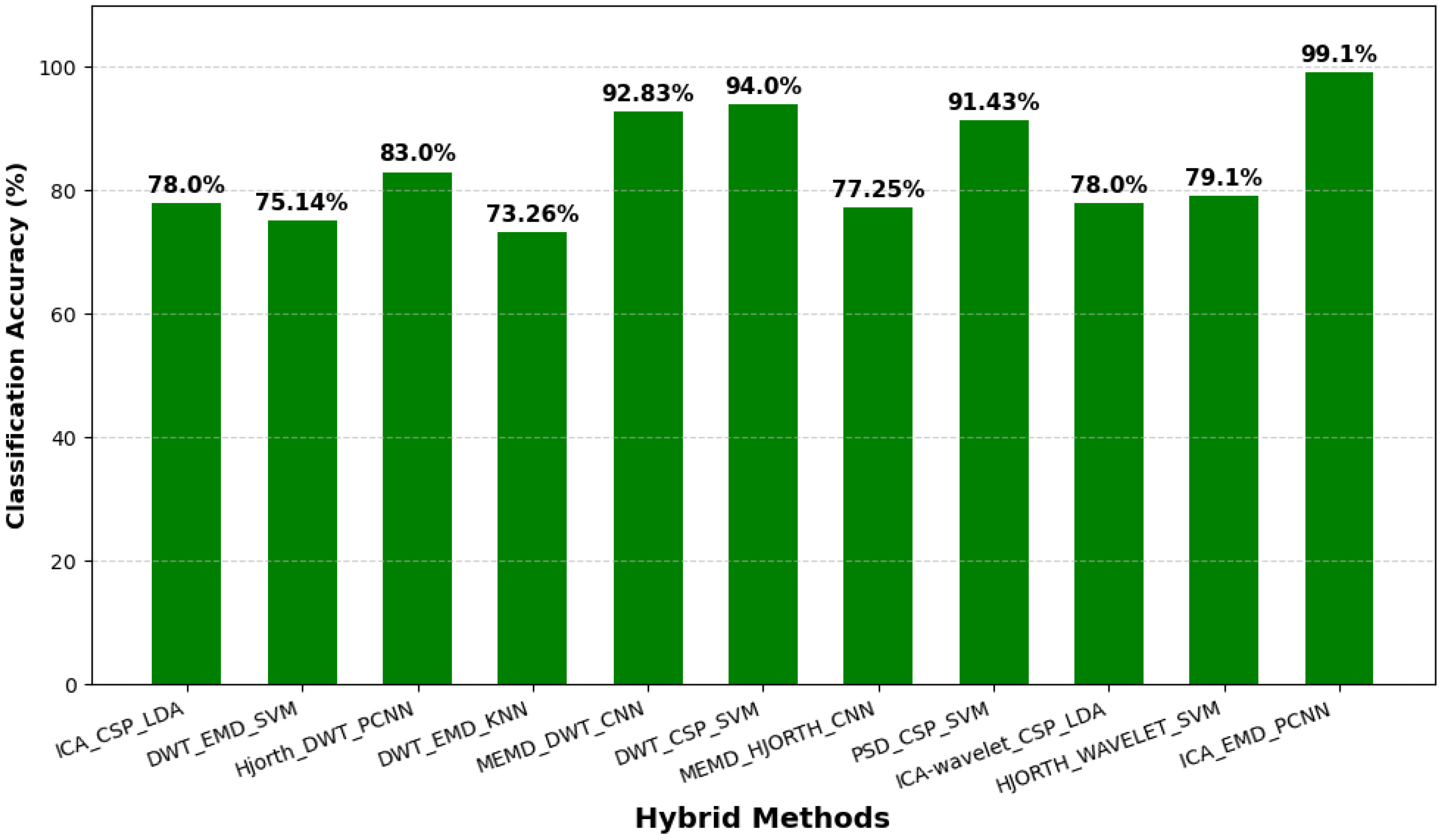

2.6. Hybrid Approaches in EEG-Based BCI Systems

3. Results

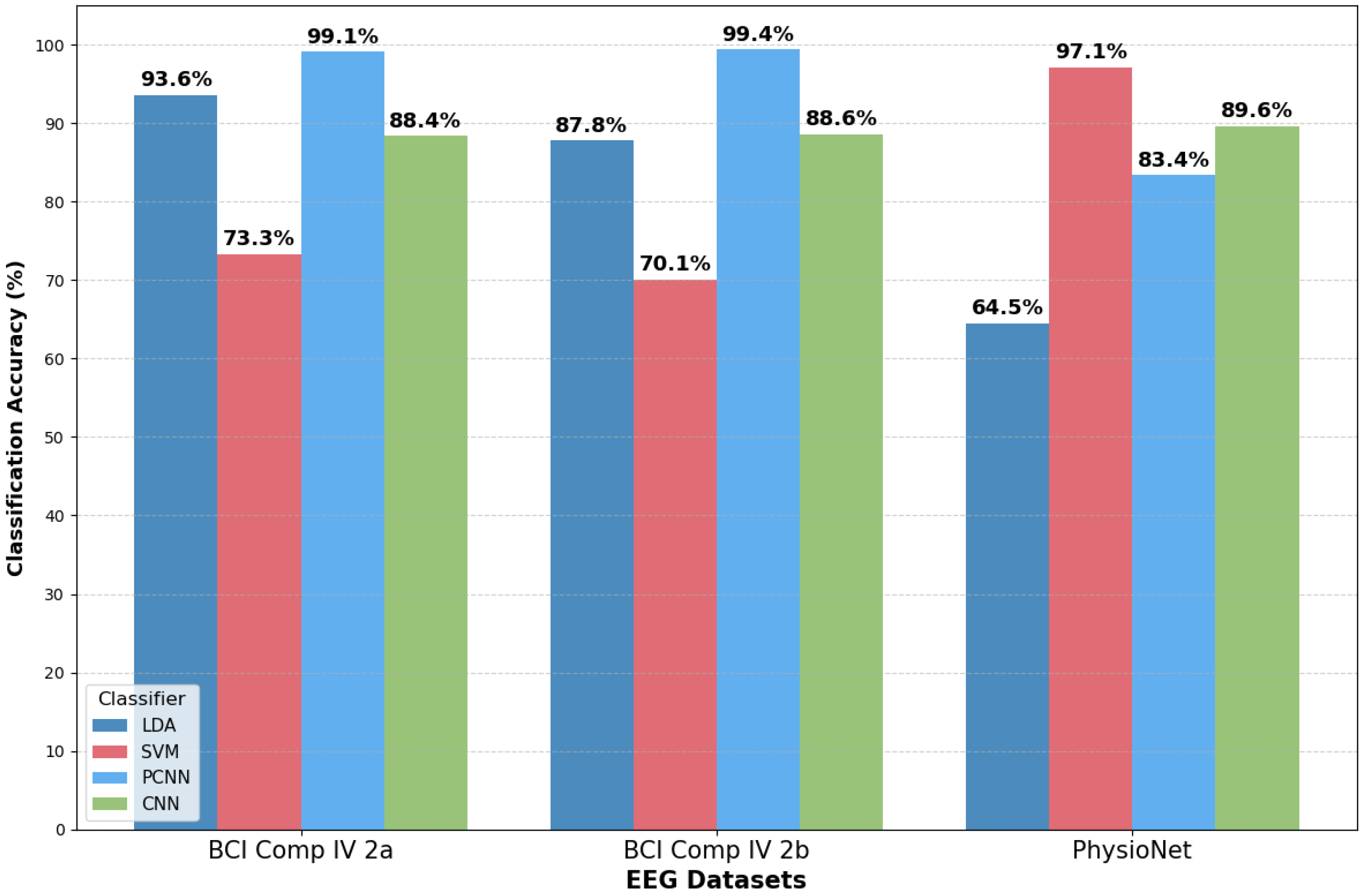

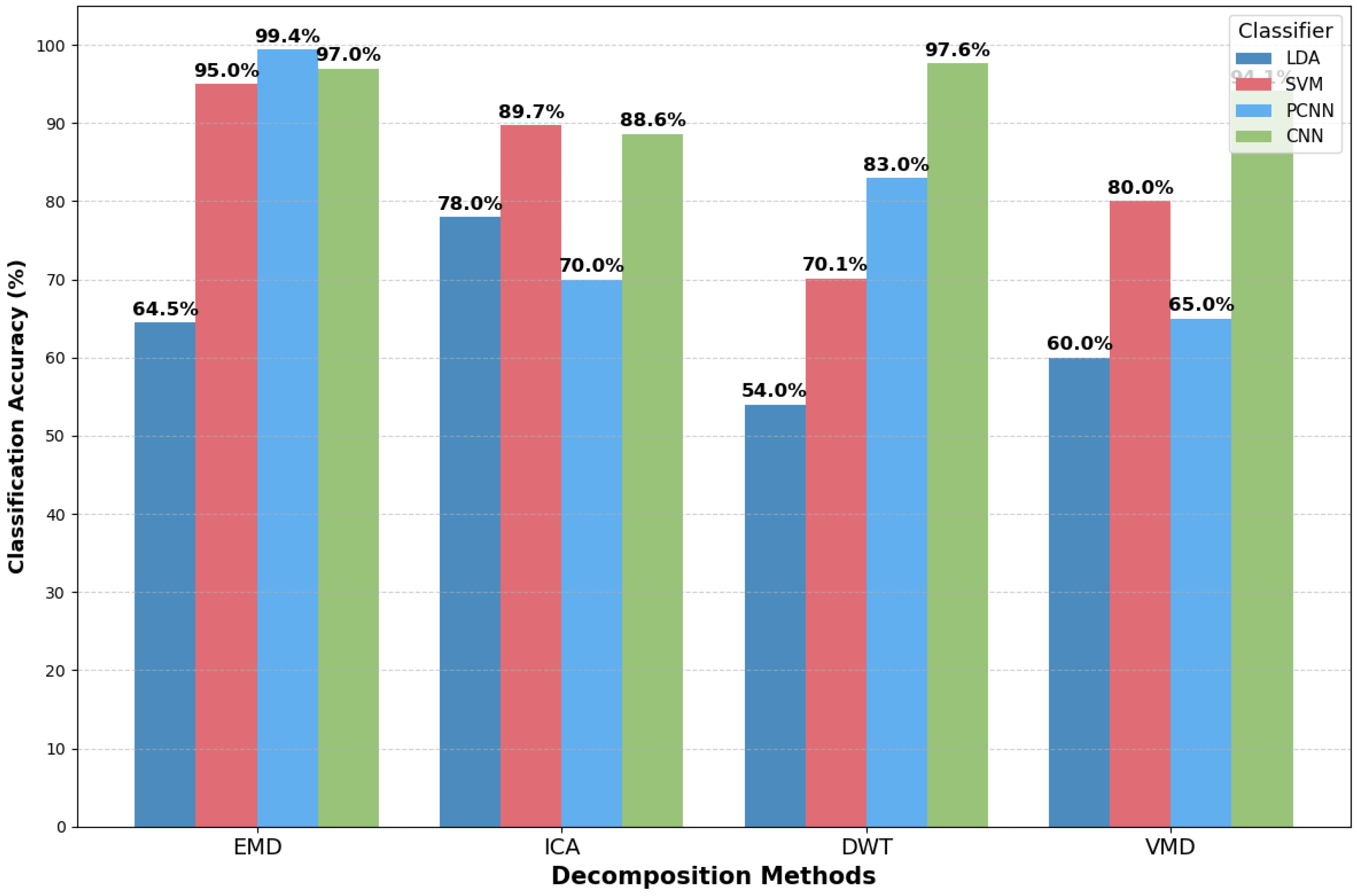

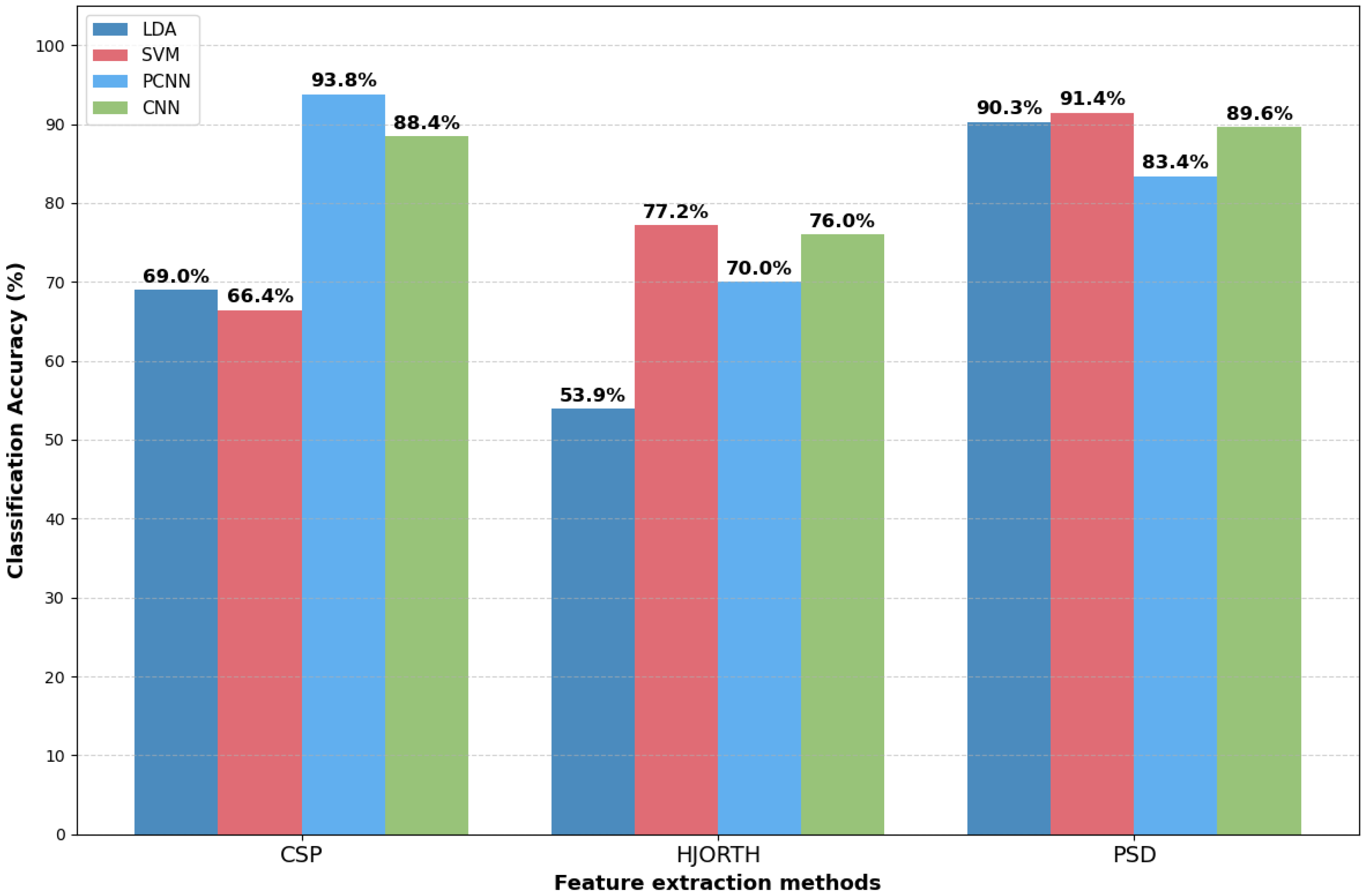

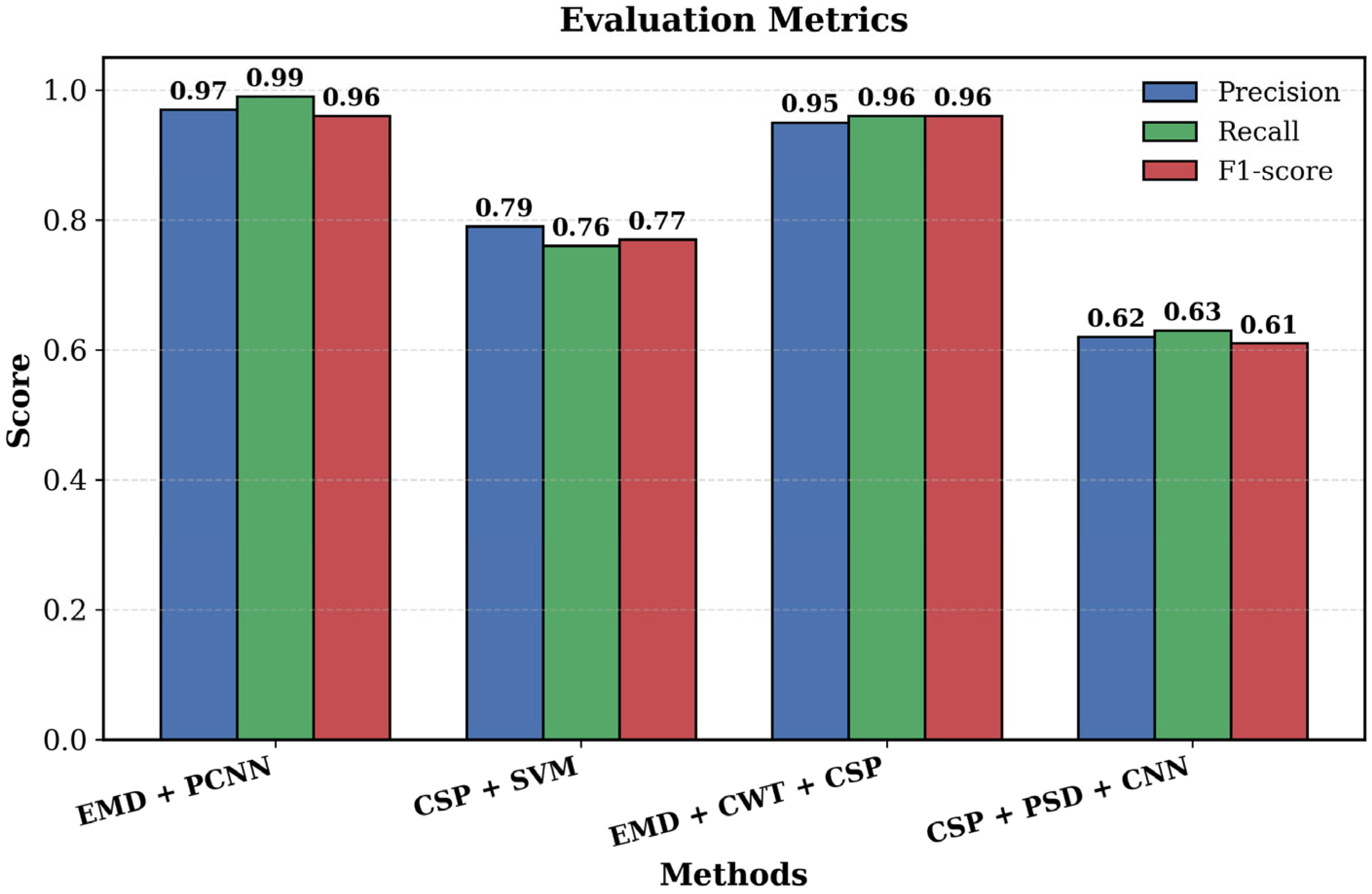

3.1. Performance of MI Classification Methods

3.2. Dataset Overview

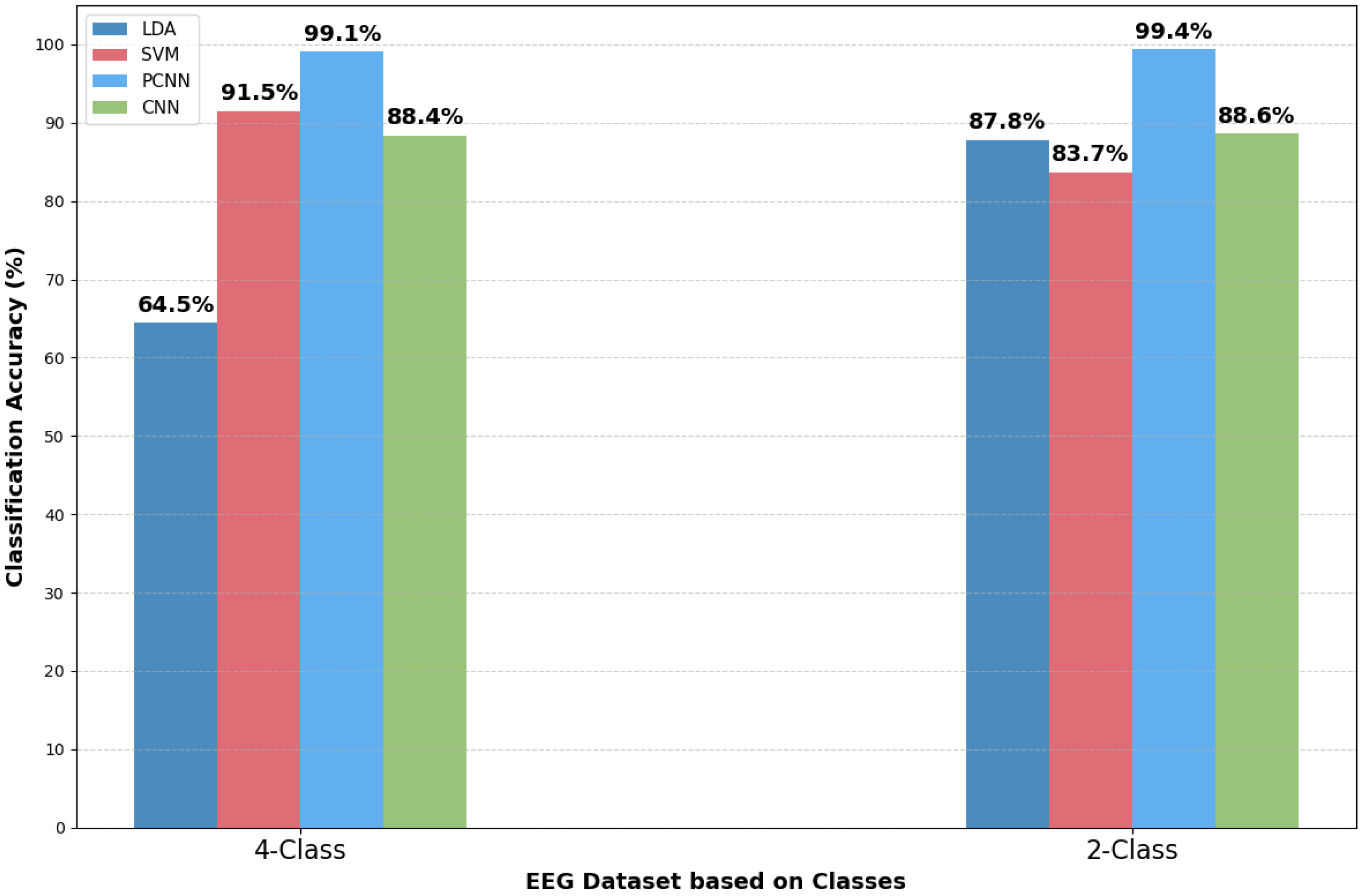

Class-Based Performance (Two-Class vs. Four-Class)

3.3. Performance Evaluation Based on BCI Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| BCI | Brain–Computer Interface |

| PCNN | Parallel Convolutional Neural Network |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| EMD | Empirical Mode Decomposition |

| ICA | Independent Component Analysis |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| CSP | Common Spatial Pattern |

| AMICA | Adaptive Mixture Independent Component Analysis |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| DNN | Deep Neural Networks |

| NN | Neural Networks |

| IDR | Intention Detection Rate |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ML | Machine Learning |

References

- Peksa, J.; Mamchur, D. State-of-the-art on brain-computer interface technology. Sensors 2023, 23, 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brophy, E.; Redmond, P.; Fleury, A.; De Vos, M.; Boylan, G.; Ward, T. Denoising EEG signals for real-world BCI applications using GANs. Front. Neuroergonomics 2022, 2, 805573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vavoulis, A.; Figueiredo, P.; Vourvopoulos, A. A review of online classification performance in motor imagery-based brain–computer interfaces for stroke neurorehabilitation. Signals 2023, 4, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotte, F.; Bougrain, L.; Cichocki, A.; Clerc, M.; Congedo, M.; Rakotomamonjy, A.; Yger, F. A review of classification algorithms for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces: A 10 year update. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Mamun, K.A.; Ahmed, K.; Mostafa, R.; Naik, G.R.; Darvishi, S.; Khandoker, A.H.; Baumert, M. Progress in brain computer interface: Challenges and opportunities. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 578875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, S.F.; Fatimah, S.; Amin, A. Artificial intelligence in motor imagery-based bci systems: A narrative. Asian J. Med. Technol. 2022, 2, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novičić, M.; Djordjević, O.; Miler-Jerković, V.; Konstantinović, L.; Savić, A.M. Improving the Performance of Electrotactile Brain–Computer Interface Using Machine Learning Methods on Multi-Channel Features of Somatosensory Event-Related Potentials. Sensors 2024, 24, 8048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Hassan, S.A.; Haider, W.; Sun, Y.; Yu, X. A Frequency-Shifting Variational Mode Decomposition-Based Approach to MI-EEG Signal Classification for BCIs. Sensors 2025, 25, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, M.; Md Shafayet, H.; Muhammad EH, C. MLMRS-Net Electroencephalography (EEG) motion artifacts removal using a multi-layer multi-resolution spatially pooled 1D signal reconstruction network. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 8371–8388. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Lam, H.K.; Ling, S.H. Multi-classification for EEG motor imagery signals using data evaluation-based auto-selected regularized FBCSP and convolutional neural network. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 12001–12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, Y.; Hua, J.; Yi, W.; Yin, H.; Hu, R.; Wang, S. A review on signal processing approaches to reduce calibration time in EEG-based brain–computer interface. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 733546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Juhasz, Z. GPU Implementation of the Improved CEEMDAN Algorithm for Fast and Efficient EEG Time–Frequency Analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Xing, Z.; Wei, X.; Yue, C.; Dong, E.; Du, S.; Sun, Z.; Solé-Casals, J.; Caiafa, C.F. Towards improving motor imagery brain–computer interface using multimodal speech imagery. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2023, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Wu, Q.; Chi, R.; Guo, Z. Time-Frequency Double-Dimensional Multi-Scale CNN with Attention Mechanism for Motor Imagery EEG Signal Classification. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2025, 132, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.F.; Jusas, V. Advancing Fractal Dimension Techniques to Enhance Motor Imagery Tasks Using EEG for Brain–Computer Interface Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yan, G.; Chang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y. EEG-based classification combining Bayesian convolutional neural networks with recurrence plot for motor movement/imagery. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 144, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Dang, W.; Wang, X.; Hong, X.; Hou, L.; Ma, K.; Perc, M. Complex networks and deep learning for EEG signal analysis. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2021, 15, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Dhule, C.; Shukla, G.; Singh, S.; Agrawal, U.; Alsubaie, N.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Abbas, M.; Soufiene, B.O. Design of EEG based thought identification system using EMD & deep neural network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Geng, X.; Yue, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Feature extraction of motor imagery EEG signals based on PSD CSP fusion. In Intelligent Computing Technology and Automation; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Antony, M.J.; Sankaralingam, B.P.; Mahendran, R.K.; Gardezi, A.A.; Shafiq, M.; Choi, J.-G.; Hamam, H. Classification of EEG using adaptive SVM classifier with CSP and online recursive independent component analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehla, V.K.; Singhal, A.; Singh, P. EMD-based discrimination of mental arithmetic tasks from EEG signals. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 17th India Council International Conference (INDICON), New Delhi, India, 11–13 December 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Pu, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P. Learning optimal time-frequency-spatial features by the cissa-csp method for motor imagery eeg classification. Sensors 2022, 22, 8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghab Torbati, M.; Zandbagleh, A.; Daliri, M.R.; Ahmadi, A.; Rostami, R.; Kazemi, R. Explainable AI for Bipolar Disorder Diagnosis Using Hjorth Parameters. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Hu, W.; Yin, H.; Zhang, K. Spatial-Frequency Feature Learning and Classification of Motor Imagery EEG Based on Deep Convolution Neural Network. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2020, 2020, 1981728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, H.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Fang, X. Recognition of EEG signal motor imagery intention based on deep multi-view feature learning. Sensors 2020, 20, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwon, D.; Won, K.; Song, M.; Nam, C.S.; Jun, S.C.; Ahn, M. Review of public motor imagery and execution datasets in brain-computer interfaces. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1134869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- KC, S. Parallel convolutional neural network and empirical mode decomposition for high accuracy in motor imagery EEG signal classification. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0311942. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, P.; Pachori, R.B.; Wang, H.; Prasad, G. An empirical mode decomposition based filtering method for classification of motor-imagery EEG signals for enhancing brain-computer interface. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Killarney, UK, 12–17 July 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Kim, Y.-K.; Eskandarian, A. EEG-inception: An accurate and robust end-to-end neural network for EEG-based motor imagery classification. J. Neural Eng. 2021, 18, 046014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Dai, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, Q.; Hu, R.; Li, M. Motor imagery electroencephalogram classification algorithm based on joint features in the spatial and frequency domains and instance transfer. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1175399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.R.; Muhammad, Y.; Adeel, U. Enhancing cross-subject motor imagery classification in EEG-based brain–computer interfaces by using multi-branch CNN. Sensors 2023, 23, 7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Chang, W.; Yan, G.; Sadiq, M.T.; Nie, W.; Zheng, L. Enhanced classification of motor imagery EEG signals using spatio-temporal representations. Inf. Sci. 2025, 714, 122221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, M.H.; Samaha, A.; AlKamha, K. Automated classification of L/R hand movement EEG signals using advanced feature extraction and machine learning. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibrewal, N.; Leeuwis, N.; Alimardani, M. Classification of motor imagery EEG using deep learning increases performance in inefficient BCI users. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Baek, H.J. Drowsiness detection based on intelligent systems with nonlinear features for optimal placement of encephalogram electrodes on the cerebral area. Sensors 2021, 21, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawala-Sterniuk, A.; Browarska, N.; Al-Bakri, A.; Pelc, M.; Zygarlicki, J.; Sidikova, M.; Martinek, R.; Gorzelanczyk, E.J. Summary of over fifty years with brain-computer interfaces—A review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z. A review of artificial intelligence for EEG-based brain− computer interfaces and applications. Brain Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Krishnan, S. Trends in EEG signal feature extraction applications. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 1072801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Sulaiman, N.; PP Abdul Majeed, A.; Musa, R.M.; Ab Nasir, A.F.; Bari, B.S.; Khatun, S. Current status, challenges, and possible solutions of EEG-based brain-computer interface: A comprehensive review. Front. Neurorobot. 2020, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, A.; Wu, Y.; Kateb, R.; Bouridane, A. Electroencephalography signal processing: A comprehensive review and analysis of methods and techniques. Sensors 2023, 23, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Mou, C. Survey on the research direction of EEG-based signal processing. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1203059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiel, I.; Kurasz, Z.; Kurasz, R.; Duch, K. The influence of filters on EEG-ERP testing: Analysis of motor cortex in healthy subjects. Sensors 2021, 21, 7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasei, T.; Saber, M.A.; Nahvy, A.; Navabi, Z. An Efficient RTL Design for a Wearable Brain–Computer Interface. IET Comput. Digit. Tech. 2024, 2024, 5596468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; K Stylios, G. Comparison of motion artefact reduction methods and the implementation of adaptive motion artefact reduction in wearable electrocardiogram monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, A.; Onojima, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kitajo, K. Real-time implementation of EEG oscillatory phase-informed visual stimulation using a least mean square-based AR model. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturki, F.A.; AlSharabi, K.; Abdurraqeeb, A.M.; Aljalal, M. EEG signal analysis for diagnosing neurological disorders using discrete wavelet transform and intelligent techniques. Sensors 2020, 20, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klug, M.; Berg, T.; Gramann, K. Optimizing EEG ICA decomposition with data cleaning in stationary and mobile experiments. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, G.; Li, Y. Protocol for semi-automatic EEG preprocessing incorporating independent component analysis and principal component analysis. STAR Protoc. 2025, 6, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, S.; Kujala, J.; Salmelin, R. Removing ocular artifacts from magnetoencephalographic data on naturalistic reading of continuous texts. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 974162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Filippin, L.; Buiatti, M.; Parise, E. WTools: A MATLAB-based toolbox for time-frequency analysis. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raveendran, S.; Kenchaiah, R.; Kumar, S.; Sahoo, J.; Farsana, M.; Chowdary Mundlamuri, R.; Bansal, S.; Binu, V.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Ramakrishnan, S. Variational mode decomposition-based EEG analysis for the classification of disorders of consciousness. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1340528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, X.; Ling, B.W.-K.; Liao, G. Empirical mode decomposition based multi-modal activity recognition. Sensors 2020, 20, 6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaipriya, D.; Sriharipriya, K. A comparative analysis of masking empirical mode decomposition and a neural network with feed-forward and back propagation along with masking empirical mode decomposition to improve the classification performance for a reliable brain-computer interface. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1010770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Hou, J.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Hybrid MVMD-ICA Framework for EOG Artifacts Removal from Few-Channel EEG Signals. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Bio-engineering for Smart Technologies (BioSMART), Paris, France, 14–16 May 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q.; Li, M.; Li, Y. Single-channel EEG signal extraction based on DWT, CEEMDAN, and ICA method. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1010760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwata-Velu, T.; Navarro Rodríguez, A.; Mfuni-Tshimanga, Y.; Mavuela-Maniansa, R.; Martínez Castro, J.A.; Ruiz-Pinales, J.; Avina-Cervantes, J.G. EEG-BCI Features Discrimination between Executed and Imagined Movements Based on FastICA, Hjorth Parameters, and SVM. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawee, W.H.; Basem, A.; Al-Haddad, L.A. Advancing biomedical engineering: Leveraging Hjorth features for electroencephalography signal analysis. J. Electr. Bioimpedance 2023, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Chugh, N. Signal processing techniques for motor imagery brain computer interface: A review. Array 2019, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. Challenges and Future Development of Neural Signal Decoding and Brain-Computer Interface Technology. J. Med. Life Sci. 2025, 1, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, M.; Torres, A.M.; Blasco-Segura, P.; Mateo, J. Application of the Random Forest Algorithm for Accurate Bipolar Disorder Classification. Life 2025, 15, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Bhadra, K.; Giraud, A.-L.; Marchesotti, S. Adaptive LDA classifier enhances real-time control of an EEG brain–computer interface for decoding imagined syllables. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, H.A.; Al-Faiz, M.Z. Offline linear discriminant analysis classfication of two class eeg signals. Iraqi J. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2019, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, X.; Yan, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Z.J. Classification of EEG signals using a multiple kernel learning support vector machine. Sensors 2014, 14, 12784–12802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Z. The development and application of support vector machine. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1748, 052006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Melek, M.; Gökrem, L. A Safe and Efficient Brain–Computer Interface Using Moving Object Trajectories and LED-Controlled Activation. Micromachines 2025, 16, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamhi, S.; Zhang, S.; Ait Amou, M.; Mouhafid, M.; Javaid, I.; Ahmad, I.S.; Abd El Kader, I.; Kulsum, U. Multi-classification of motor imagery EEG signals using Bayesian optimization-based average ensemble approach. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, E.; Bozios, P.; Christou, V.; Tzimourta, K.D.; Kalafatakis, K.; G Tsipouras, M.; Giannakeas, N.; Tzallas, A.T. EEG-based eye movement recognition using brain–computer interface and random forests. Sensors 2021, 21, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, K.M.; Islam, M.A.; Hossain, S.; Nijholt, A.; Ahad, M.A.R. Status of deep learning for EEG-based brain–computer interface applications. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1006763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakhmatulin, I.; Dao, M.-S.; Nassibi, A.; Mandic, D. Exploring convolutional neural network architectures for EEG feature extraction. Sensors 2024, 24, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lun, X.; Yu, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, F.; Hou, Y. A simplified CNN classification method for MI-EEG via the electrode pairs signals. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, C.; Gong, X. Deep convolutional neural network for decoding motor imagery based brain computer interface. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC), Xiamen, China, 22–25 October 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, S.G.; Yilmaz, B. Distinguishing Resting State From Motor Imagery Swallowing Using EEG and Deep Learning Models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 178375–178389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Niu, Y.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Fu, B.; Shi, G.; Dong, M. A parallel multiscale filter bank convolutional neural networks for motor imagery EEG classification. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Chen, T.; Ma, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J. CLTNet: A Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Motor Imagery Classification. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelishiyah, R.; Thiyam, D.B.; Margaret, M.J.; Banu, N.M. A hybrid CNN model for classification of motor tasks obtained from hybrid BCI system. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ji, H.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; Liu, L.; Bai, Z.; Ye, C. Subject-independent EEG classification based on a hybrid neural network. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1124089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhan, N.; Dokur, Z.; Olmez, T. Motor imagery based EEG classification by using common spatial patterns and convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Scientific Meeting on Electrical-Electronics & Biomedical Engineering and Computer Science (EBBT), Istanbul, Turkey, 24–26 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.F.; Jusas, V. Developing innovative feature extraction techniques from the emotion recognition field on motor imagery using brain–computer interface EEG signals. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Lee, T. Multivariate empirical mode decomposition of EEG for mental state detection at localized brain lobes. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, UK, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 3694–3697. [Google Scholar]

- Babiker, A.; Faye, I. A Hybrid EMD-Wavelet EEG Feature Extraction Method for the Classification of Students’ Interest in the Mathematics Classroom. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 6617462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Tang, H.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, Z. A study of motor imagery EEG classification based on feature fusion and attentional mechanisms. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1611229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liesaputra, V.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z. An in-depth survey on deep learning-based motor imagery electroencephalogram (EEG) classification. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 147, 102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Situ, Z.; Peng, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y. Multi-Class Classification Methods for EEG Signals of Lower-Limb Rehabilitation Movements. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degirmenci, M.; Yuce, Y.K.; Perc, M.; Isler, Y. Statistically significant features improve binary and multiple Motor Imagery task predictions from EEGs. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1223307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, K.; Xu, M.; Yi, W.; Xu, F.; Ming, D. Transformed common spatial pattern for motor imagery-based brain-computer interfaces. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1116721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postepski, F.; Wojcik, G.M.; Wrobel, K.; Kawiak, A.; Zemla, K.; Sedek, G. Recurrent and convolutional neural networks in classification of EEG signal for guided imagery and mental workload detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Singh, S.; Kim, J.; Ahanger, T.A.; Pise, A.A. Enhanced EEG signal classification in brain computer interfaces using hybrid deep learning models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchane, M.; Guo, W.; Yang, S. Hybrid CNN-GRU models for improved EEG motor imagery classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Y.; Wei, Z.; An, G.; Chen, H. Combining data augmentation and deep learning for improved epilepsy detection. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1378076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwaidi, J.; Ghanem, M.C. Motor Imagery EEG Signal Classification Using Minimally Random Convolutional Kernel Transform and Hybrid Deep Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.16179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampel, N.; Kiefer, C.M.; Shah, N.J.; Neuner, I.; Dammers, J. Neural fingerprinting on MEG time series using MiniRocket. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1229371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, D.; Laufer, I.; Zuckerman, I. Comparative analysis of ROCKET-driven and classic EEG features in predicting attachment styles. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.A.; Parupudi, T.; Thalengala, A.; Nayak, S.G. A comprehensive review of deep learning models for denoising EEG signals: Challenges, advances, and future directions. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionakis, E.; Karampidis, K.; Papadourakis, G. Current trends, challenges, and future research directions of hybrid and deep learning techniques for motor imagery brain–computer interface. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwaidi, J.F.; Chen, T.M. Classification of motor imagery EEG signals based on deep autoencoder and convolutional neural network approach. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 48071–48081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Authors | Datasets | Methods | Performance | Study Limitation | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | W. Huang et al. [16] | Physio Net and GigaDB | RP-BCNNs | 91% | Possibility of spatial information loss. | Suitable for learning nonlinear dynamic features |

| 2024 | R. Agrawal et al. [18] | Self-generated | CSP + EMD + DNN | 97% | Computational complexity and noise susceptibility | Lab and real-time deployment analysis |

| 2024 | W. Hu et al. [19] | BCI IV-1a | PSD + CSP + SVM | 91.43% | Cross-subject variability Not fully explored | Improved binary MI accuracy |

| 2022 | M.J. Antony [20] | BCI IV-2a | Adaptive SVM Adaptive LDA | 91% 86% | Limited to online analysis, no real-world validation | Optimized classification accuracy |

| 2020 | V.K. Mehla et al. [21] | - | EMD + SVM | 95% | Subject-to-subject variation | Strong pattern recognition |

| 2022 | Hai Hu et al. [22] | BCI IV-1a and III | CiSSA + CSP | 96% | High-dimensional feature space, leads to overfitting | Highly effective feature extraction |

| 2025 | M.S. Sagahab [23] | Self-generated | Hjorth parameters | 92.05% | Small sample size, generalization limited | Interpretable neural features |

| 2020 | Miao M et al. [24] | BCI III-4, private | CSP + CNN | 90% | Limited subject data | Automatic spatial frequency feature learning |

| 2020 | Xu et al. [25] | BCI IV-2a | FBCSP + SVM | 78.50% | Intra-subject variability | High-accuracy multi-view fusion |

| Datasets | Subject | Channels | Age and Sex (F or M) | Sampling Rate | Class | Study Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCI Competition IV 2a and 2b [27] | 9 | 22 | - | 250 | 2 Class | Inter-subject variation, possibility of overfitting, and high computation |

| 4 Class | ||||||

| BCI Competition IV 2a and 2b [28] | 9 | 22 | - | 250 | 2 Class | Limited generalization beyond BCI datasets and subjects |

| BCI Competition IV 2a and 2b [29] | 9 | 22 | - | 250 | 2 Class | High model complexity, generalization validated |

| 4 Class | ||||||

| BCI Competition IV 2a and 2b [30] | 9 | 22 | - | 250 | 2 Class | Sensitive to low SNR and session-to-session variation, with limited real-world validation |

| 4 Class | ||||||

| Physio Net [31] | 109 | 64 | - | 160 | 2 Class (E*) | Low SNR and session variability may reduce generalization |

| 4 Class (I*) | ||||||

| Physio Net [32] | 10 and 30 | - | - | 160 | 2 Class | Accuracy drops in multi-class tasks, inter-session variability |

| 4 Class | ||||||

| Physio Net [33] | - | - | - | - | 2 Class | Limited to offline analysis |

| Physio Net [34] | 57 | 22 | - | 250 | 2 Class | Model performance may vary across different user groups; real-world applicability was not fully validated. |

| Datasets | Subjects | Classes * | Recording Duration | Trails per Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCI Competition IV 2a | 9 | 4 (LH, RH, F, T) | ~288 trials per subject | 72/class |

| BCI Competition IV 2b | 9 | 2 (LH, RH) | ~160 trials per subject | 80/class |

| PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery | 109 | 2 (LH, RH) + variants | ~150 trials per subject | 75/class |

| Or 4 (LH, RH, F, T) |

| Dataset | Preprocessing | Feature Extraction | Classifier | Accuracy (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCI Competition IV 2a [27] | Bandpass + Notch filter | EMD | PCNN | 99.1% (2-class) | Strong robustness via IMF decomposition |

| BCI Competition IV 2b [27] | Bandpass + Notch filter | EMD | PCNN | 99.39% (4-class) | Effective multiclass separation |

| BCI Competition IV 2a [28] | Bandpass + Notch filter | Band-power + Hjorth | LDA | 93.6% (2-class) | Good spectral + temporal fusion |

| BCI Competition IV 2b [28] | Bandpass + Notch filter | Band-power + Hjorth | LDA | 87.8% (2-class) | Drop in generalization across sessions |

| BCI Competition IV 2a [29] | - | Raw EEG (Conv Input) | CNN | 88.4% (2-class) | CNN learns hierarchical features |

| BCI Competition IV 2b [29] | - | Raw EEG (Conv Input) | CNN | 88.6% (4-class) | Small improvement despite higher class count |

| BCI Competition IV 2a [30] | Bandpass + Notch filter | CSP | SVM | 73.2% (2-class) | Margin-based separation but low robustness |

| BCI Competition IV 2b [30] | Bandpass + Notch filter | CSP | SVM | 70.1% (4-class) | Multi-class setting stresses CSP |

| Physio Net [31] | - | CNN (Executed MI) | CNN | 89.6% (2-class) | Executed tasks give stronger discriminative patterns |

| Physio Net [31] | - | CNN (imagined MI) | CNN | 87.8% (2-class) | Imagined tasks are harder to classify |

| Physio Net [32] | Butterworth + sliding window | - | PCNN | 99.73% (2-class) | Very high binary accuracy |

| Physio Net [32] | Butterworth + sliding window | - | PCNN | 83.37% (4-class) | Accuracy drops with increased complexity |

| Physio Net [33] | - | CSP | SVM | 97.1% (2-class) | Strong linear separation under controlled setup |

| Physio Net [34] | - | CSP | LDA | 64.45% (2-class) | Performance is limited by electrode coverage |

| Method | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| FIR/IIR Filters | Simple, fast, and effective for removing line noise and band-limiting EEG | Limited to fixed frequency bands, cannot adapt to nonstationary signals |

| ICA | Separate sources and remove eye blinks/muscle artifacts effectively | Performance depends on channel count and noise, and is unstable across subjects. |

| CNN/Parallel CNN | Learns spatial–temporal patterns directly, achieves high accuracies (95–99%) | Requires large datasets, may overfit if the data are limited. |

| Autoencoders | Unsupervised denoising compresses features efficiently | Reconstruction may lose subtle EEG features and requires fine-tuning. |

| GANs | Can generate a realistic synthetic EEG to balance training sets. | Prone to instability in training, risk of mode collapse. |

| RNN/LSTM/GRU | Captures temporal dependencies across long EEG sequences | Training is slow, high computational demand, sensitive to vanishing gradients. |

| Transformers | Excellent for capturing global dependencies, promising in EEG-BCI. | Requires massive datasets, still relatively unexplored for BCI |

| Hybrid (EMD + CNN, CSP + LSTM) | Combines feature decomposition with deep learning, achieving state-of-the-art accuracies (>99%) | Increased computational cost, risk of overfitting on small datasets. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mdluli, B.; Khumalo, P.; Maswanganyi, R.C. Signal Preprocessing, Decomposition and Feature Extraction Methods in EEG-Based BCIs. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212075

Mdluli B, Khumalo P, Maswanganyi RC. Signal Preprocessing, Decomposition and Feature Extraction Methods in EEG-Based BCIs. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212075

Chicago/Turabian StyleMdluli, Bandile, Philani Khumalo, and Rito Clifford Maswanganyi. 2025. "Signal Preprocessing, Decomposition and Feature Extraction Methods in EEG-Based BCIs" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212075

APA StyleMdluli, B., Khumalo, P., & Maswanganyi, R. C. (2025). Signal Preprocessing, Decomposition and Feature Extraction Methods in EEG-Based BCIs. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212075