Predicting the Strength of Fly Ash–Slag–Gypsum-Based Backfill Materials Using Interpretable Machine Learning Modeling

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Model Introduction

2.2.1. Random Forest

2.2.2. Gradient Boosting

2.2.3. LightGBM

2.2.4. CNN

2.3. Algorithm Introduction

2.3.1. Bayesian Optimization

2.3.2. Gray Wolf Algorithm

2.3.3. Whale Optimization Algorithm

2.3.4. Particle Swarm Algorithm

2.3.5. Recursive Feature Elimination

3. Results and Discussion

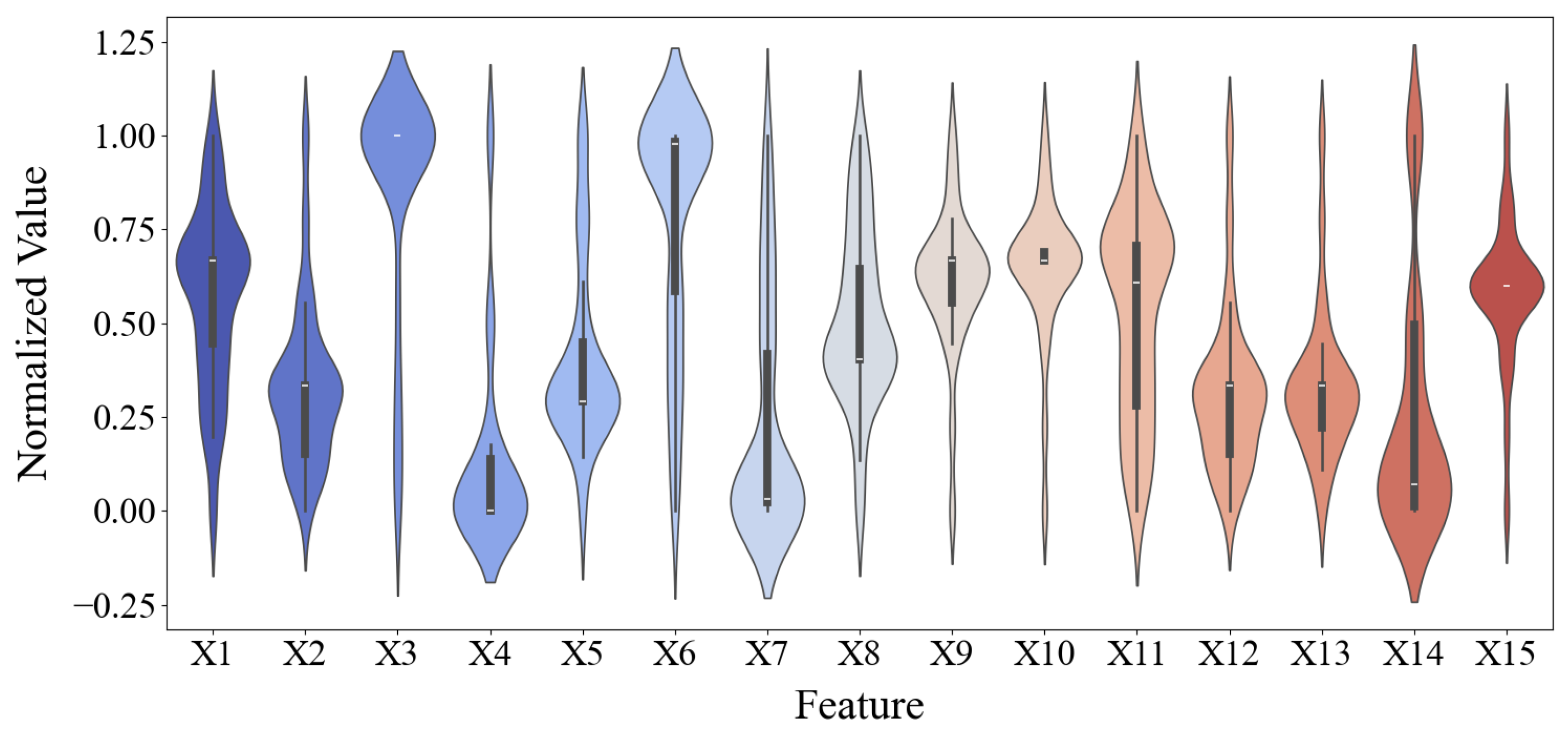

3.1. Results of Feature Parameter Selection

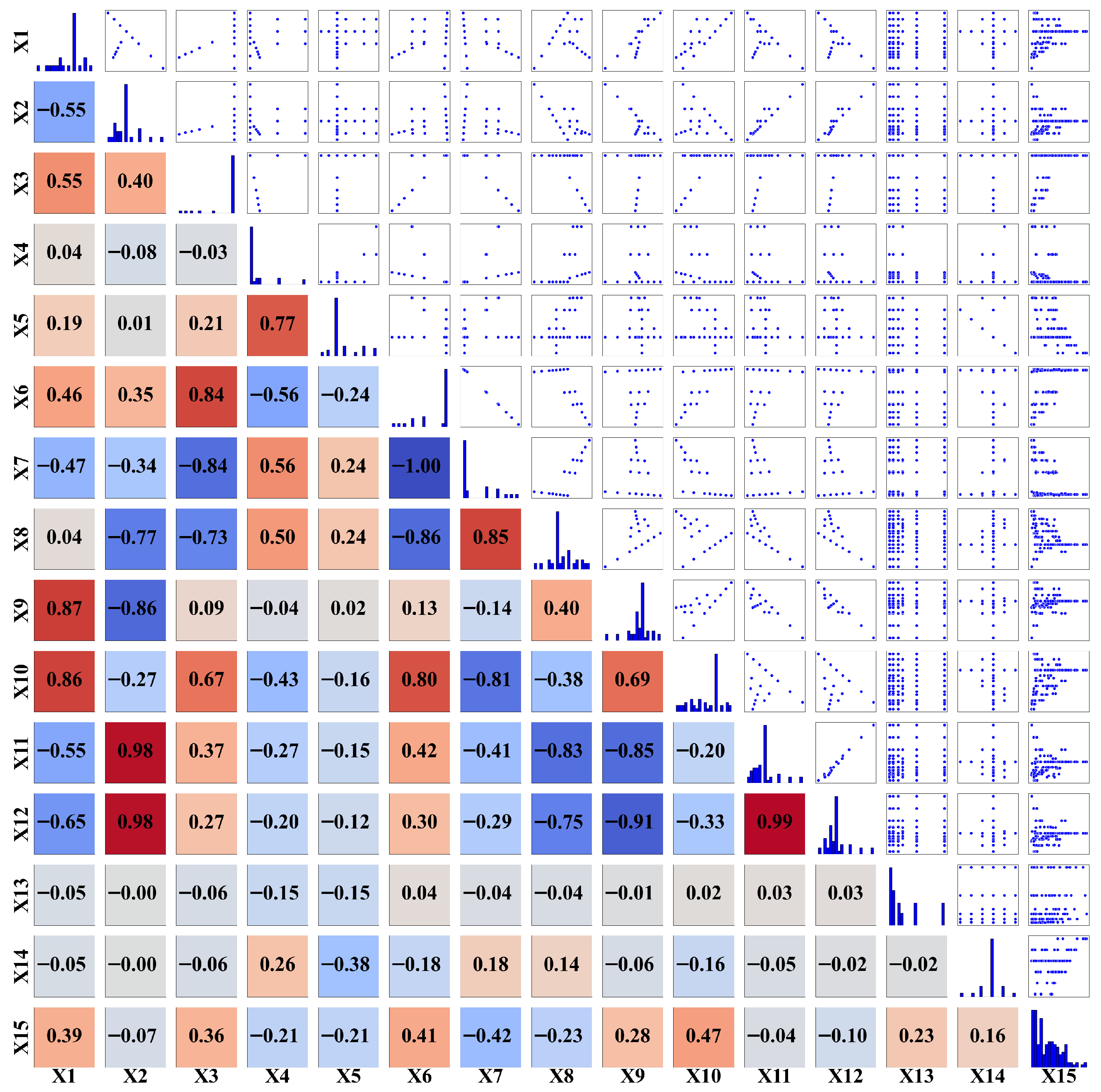

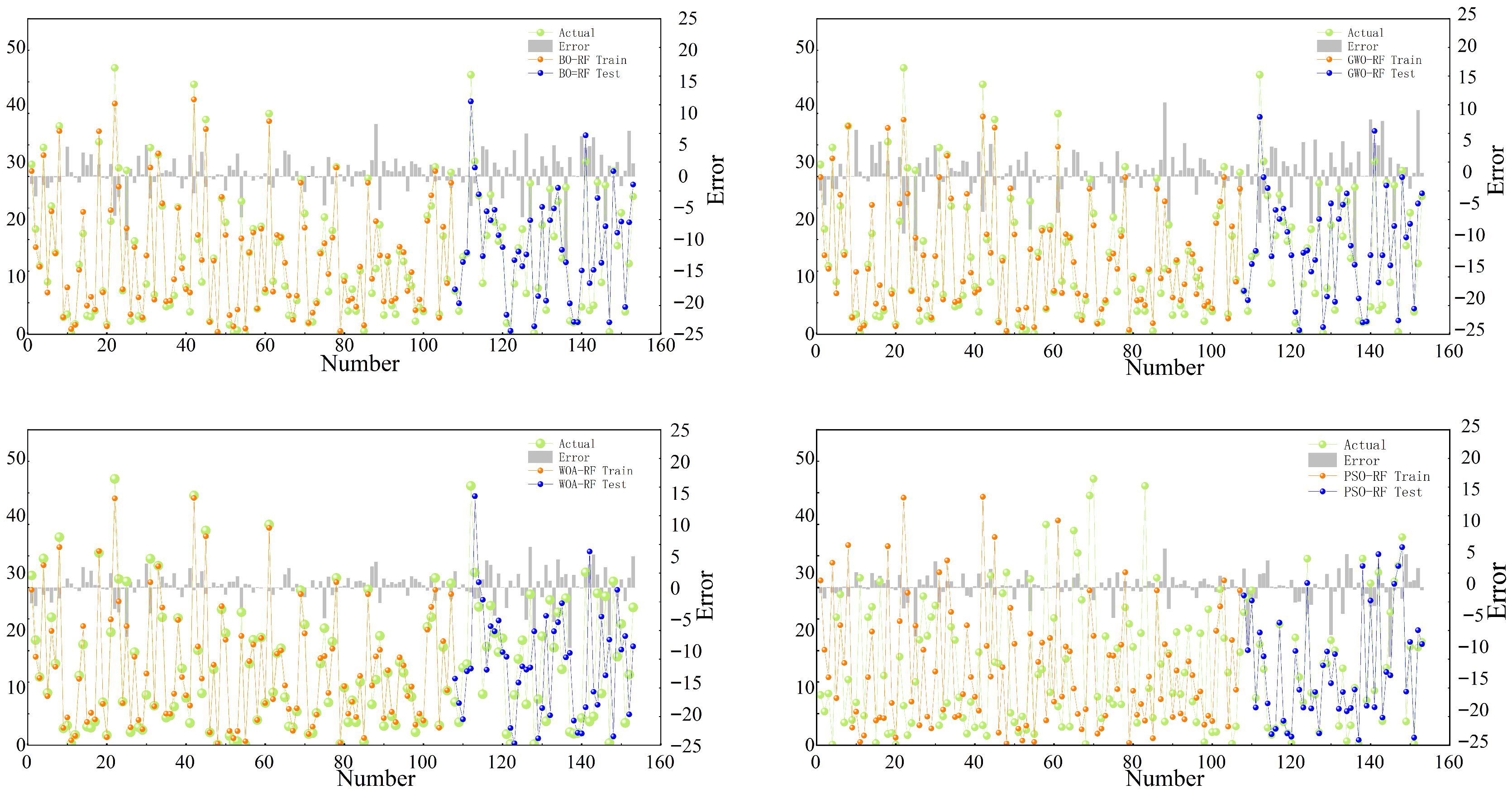

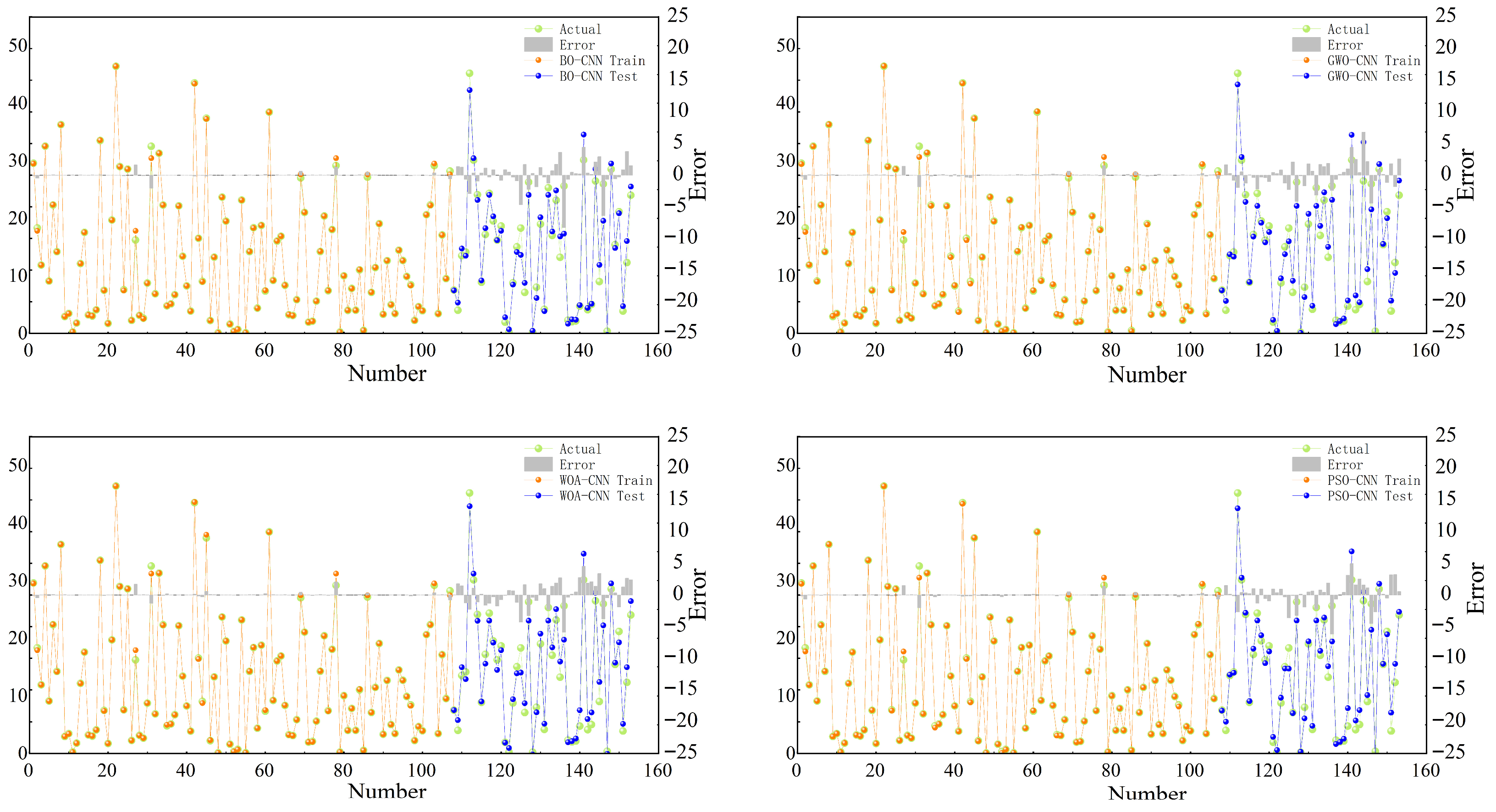

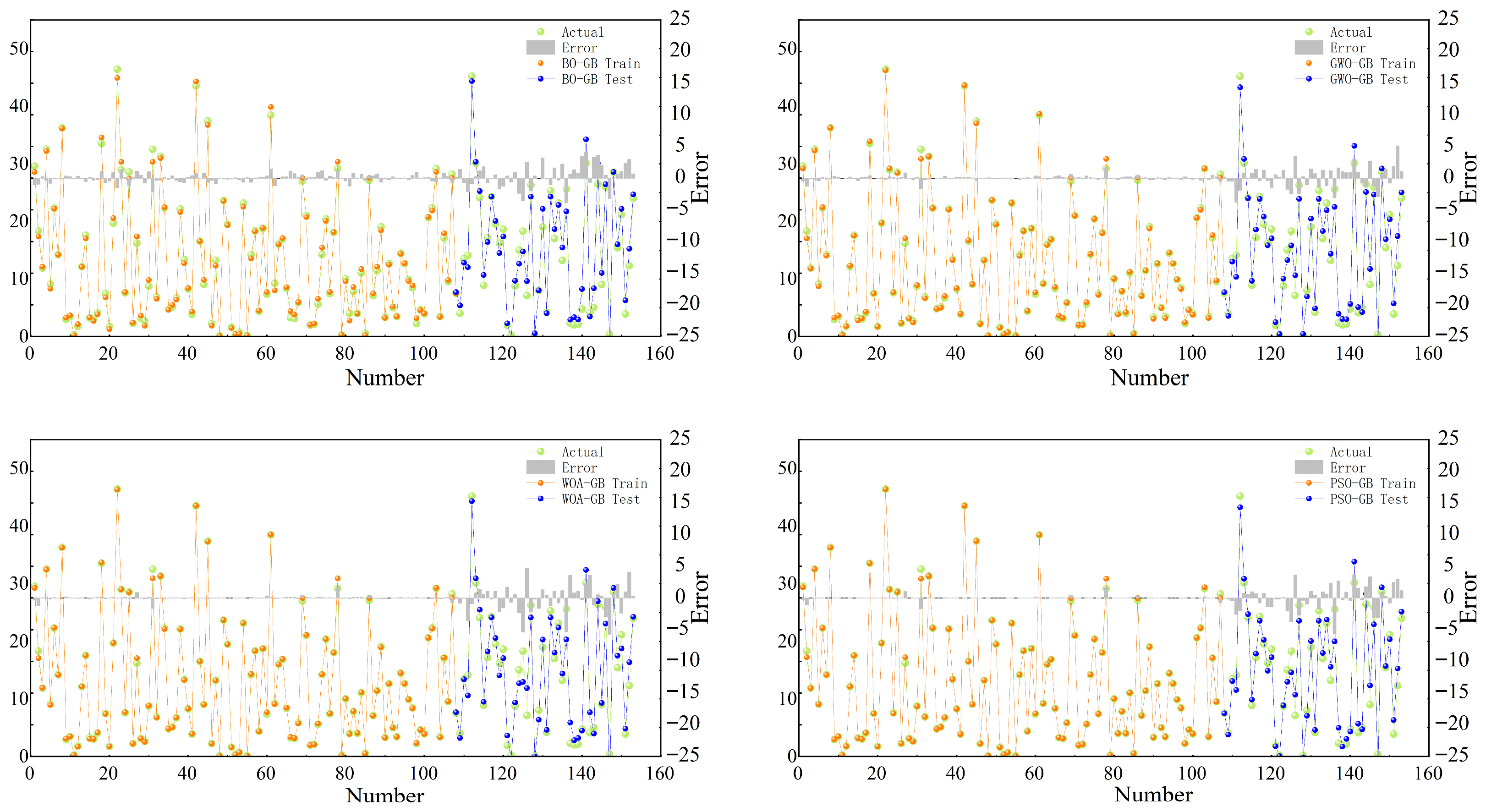

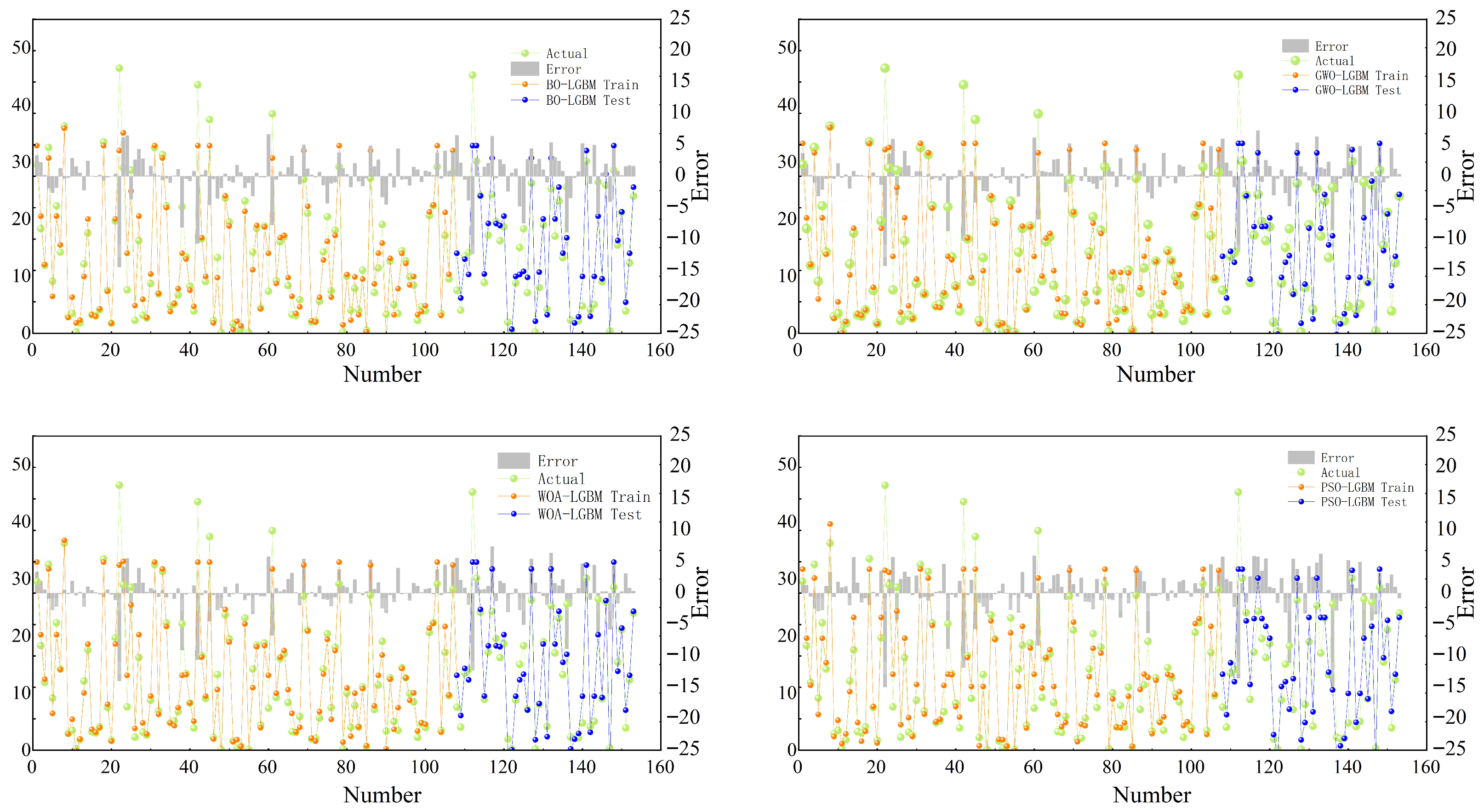

3.2. Model Evaluation Results

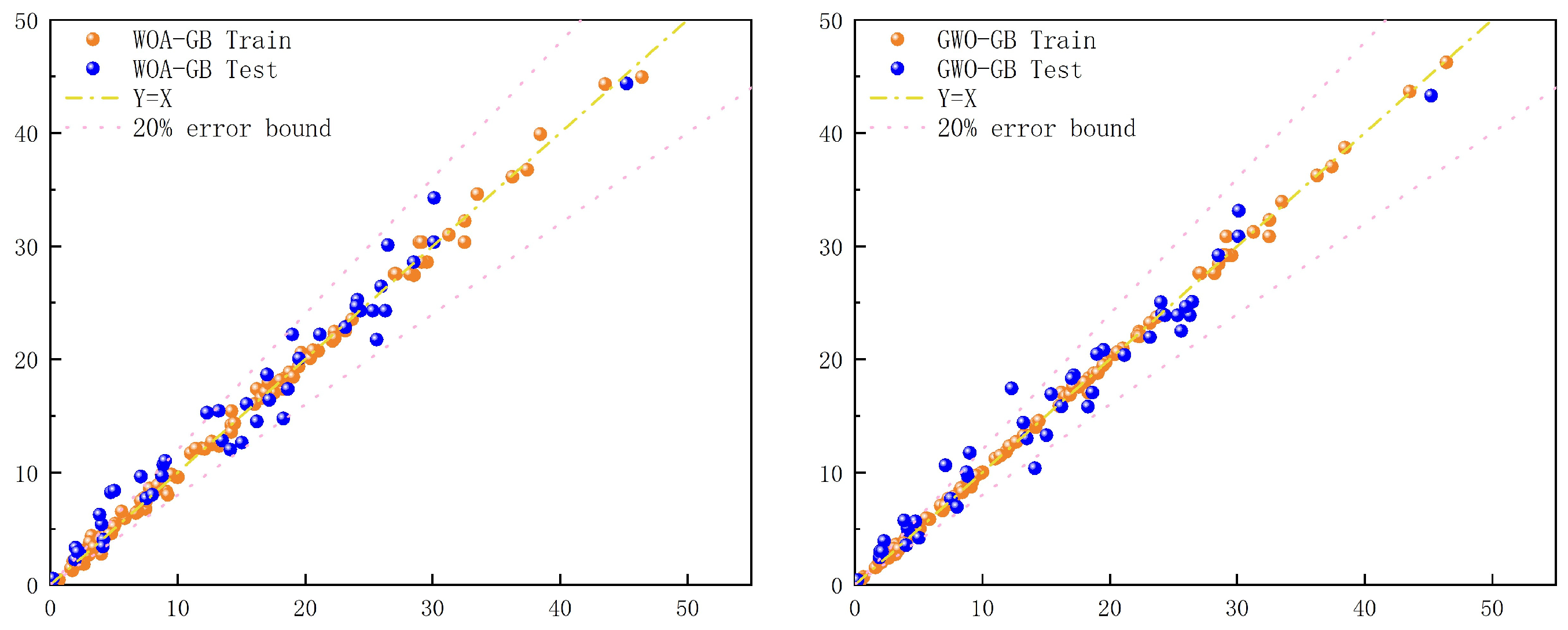

3.3. Validation

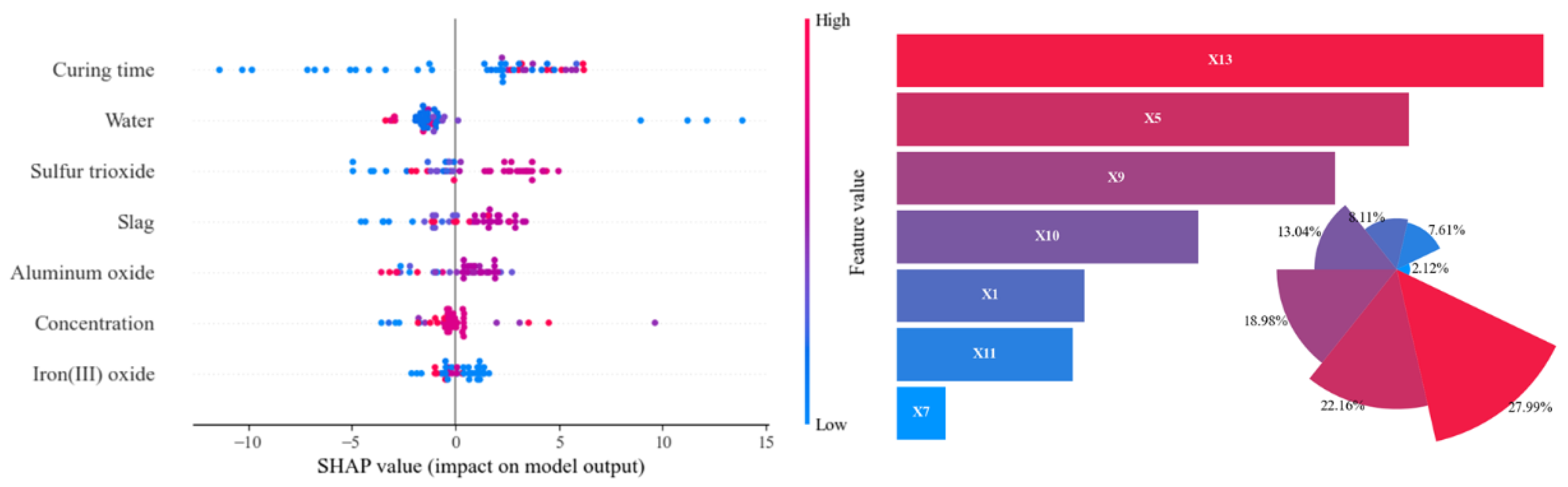

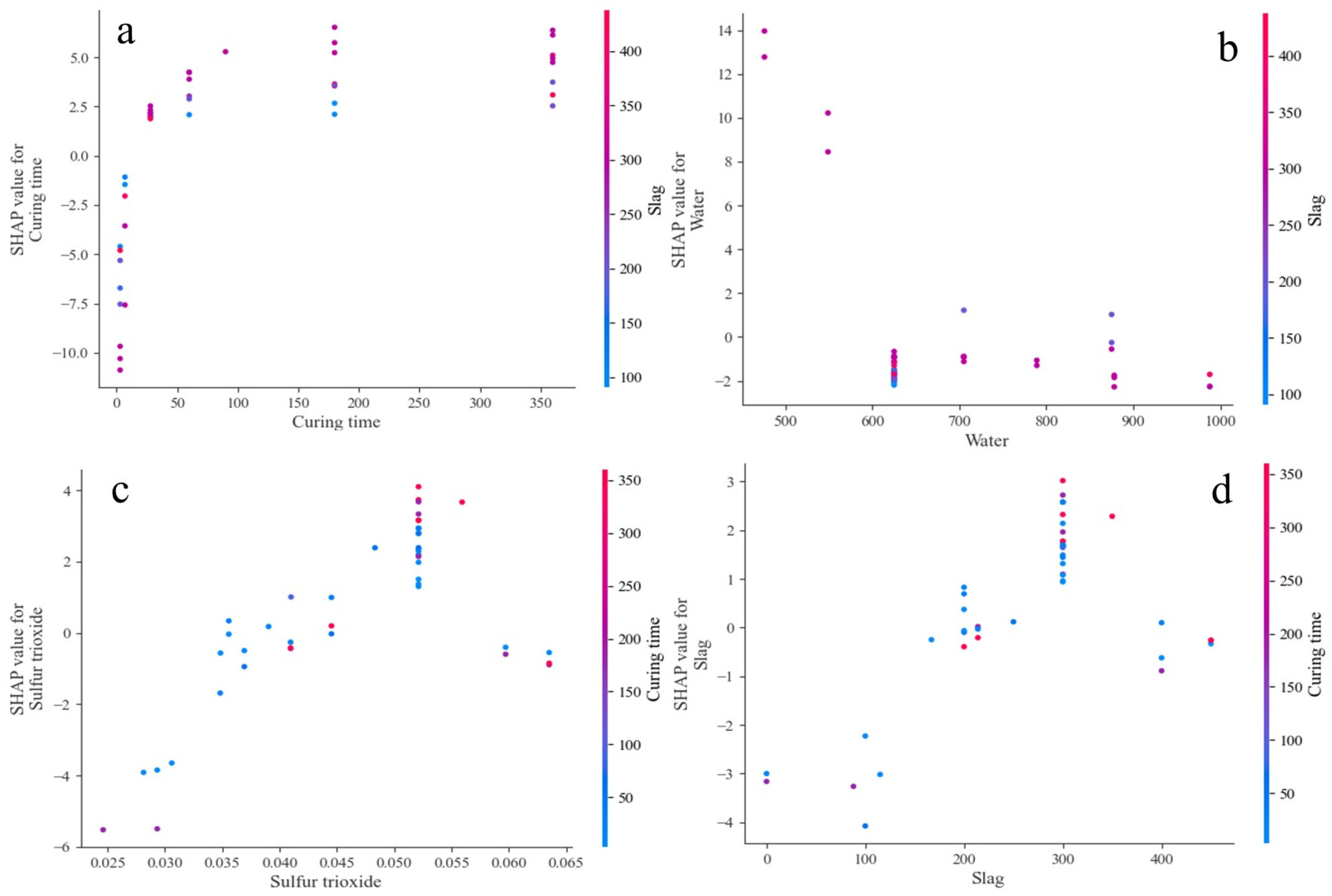

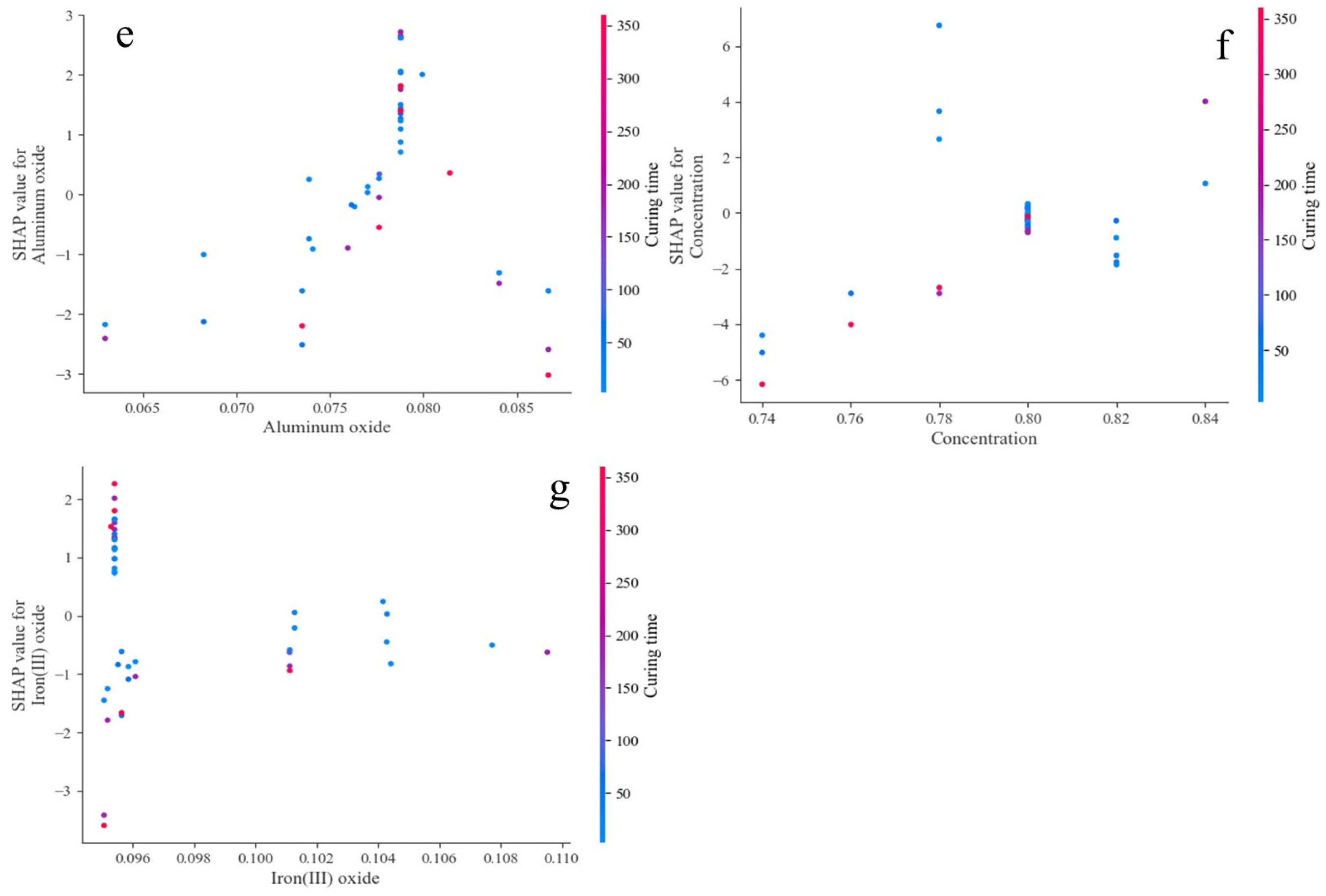

3.4. Optimal Model Interpretation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niu, Y.; Wen, L.; Guo, X.; Hui, S. Co-disposal and reutilization of municipal solid waste and its hazardous incineration fly ash. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alidoust, P.; Keramati, M.; Hamidian, P.; Amlashi, A.T.; Gharehveran, M.M.; Behnood, A. Prediction of the shear modulus of municipal solid waste (MSW): An application of machine learning techniques. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 127053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalchian, M.M.; Arabani, M.; Farshi, M.; Ranjbar, P.Z.; Khajeh, A.; Payan, M. Sustainable Construction Materials: Application of Chitosan Biopolymer, Rice Husk Biochar, and Hemp Fibers in Geo-Structures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaldar, A.; Asadi, P.; Salimi, M.; Payan, M.; Ranjbar, P.Z.; Arabani, M.; Ahmadi, H. Application of Natural and Synthetic Fibers in Bio-Based Earthen Composites: A State-of-the-Art Review. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, M.H.; Arabani, M.; Payan, M.; Ranjbar, P.Z. The Influence of Volcanic Ash (VA) on the Mechanical Properties and Freeze-Thaw Durability of Lime Kiln Dust (LKD)-Stabilized Kaolin Clayey Soil. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Záleská, M.; Pavlík, Z.; Pavlíková, M.; Pivák, A.; Reiterman, P.; Lauermannová, A.-M.; Jiříčková, A.; Průša, F.; Jankovský, O. Towards immobilization of heavy metals in low-carbon composites based on magnesium potassium phosphate cement, diatomite, and fly ash from municipal solid waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 470, 140621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ramírez, J.D.; Bedoya-Henao, C.A.; Cabrera-Poloche, F.D.; Taborda-Llano, I.; Viana-Casas, G.A.; Restrepo-Baena, O.J.; Tobón, J.I. Exploring sustainable construction: A case study on the potential of municipal solid waste incineration ashes as building materials in San Andrés island. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, X.; Wan, M.; Fan, L.; Hu, J.; Liang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xing, F. Optimization of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash geopolymer with granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS): Microstructural development and heavy metal solidification mechanism. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, C.; Xiao, B.; Chen, G. Development of slag-based filling cementitious materials and their application in ultrafine tailing sand filling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 452, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Payan, M.; Hosseinpour, I.; Arabani, M.; Ranjbar, P.Z. Effect of Glass Fiber (GF) on the Mechanical Properties and Freeze-Thaw (F-T) Durability of Lime-Nanoclay (NC)-Stabilized Marl Clayey Soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.L.; Najafi, E.K.; Ranjbar, P.Z.; Payan, M.; Chenari, R.J.; Fatahi, B. Recycling Industrial Alkaline Solutions for Soil Stabilization by Low-Concentrated Fly Ash-Based Alkali Cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 132083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yao, Q.; Ding, J.; Ma, B.; Lu, S. Utilization of mechanochemically pretreated municipal solid waste incineration fly ash for supplementary cementitious material. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, M.; Salimi, M.; Payan, M.; Noorzad, A.; Hassanvandian, M. Development of High-Strength Rammed Earth Walls with Alkali-Activated Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBFS) and Waste Tire Textile Fiber (WTTF) as a Step towards Low-Carbon Building Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 394, 132180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, R.; Jia, Y.; Yong, M.; Li, G. Preparation and Properties of Expansive Backfill Material Based on Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash and Coal Gangue. Minerals 2024, 14, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, K.; Huang, X.; Ni, W.; Zhang, S. Leaching characteristics of Cr in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash solidified/stabilized using blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 7457–7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fu, P.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, C.; Ni, W. Development of hydration potential in CFBC bottom ash activated by MSWI fly ash: Depolymerization and repolymerization during long-term reactions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Wu, S.; Yu, F.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, X.; Liang, B. Utilizing municipal solid waste incineration fly ash for mine goaf filling: Preparation, optimization, and heavy metal leaching study. Environ. Res. 2025, 266, 120594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Wu, M.B. Effect of MSWI fly ash and incineration residues on cement performances. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2010, 25, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, C.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Y. Study on strength prediction and strength change of Phosphogypsum-based composite cementitious backfill based on BP neural network. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Li, S.; Wu, S.; Liang, B.; Zhang, X. Preparation and heavy metal solidification mechanism of physically activated municipal solid waste incineration fly ash base geopolymer backfill. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 201, 107522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Ni, W. The effects and solidification characteristics of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash-slag-tailing based backfill blocks in underground mine condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 420, 135508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Gan, M.; Ji, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Sun, Z.; Huang, X.; Fan, Y. Recent progress on the thermal treatment and resource utilization technologies of municipal waste incineration fly ash: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 159, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Meng, Y.; Ju, T.; Chen, Z.; Du, Y.; Deng, Y.; Song, M.; Han, S.; Jiang, J. Synthesis and application of geopolymers from municipal waste incineration fly ash (MSWI FA) as raw ingredient—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, L.; Yan, J. Synergistic recycling of MSWI fly ash and incinerated sewage sludge ash into low-carbon binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 445, 137930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodkari, N.; Hamidian, P.; Khodkari, H.; Payan, M.; Behnood, A. Predicting the small strain shear modulus of sands and sand-fines binary mixtures using machine learning algorithms. Transp. Geotech. 2024, 44, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Pan, K.; Xiu, W.; Li, M.; He, Z.; Wang, L. Research on Attack Detection for Traffic Signal Systems Based on Game Theory and Generative Adversarial Networks. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidian, P.; Alidoust, P.; Mohammadi Golafshani, E.; Pourrostami Niavol, K.; Behnood, A. Introduction of a novel evolutionary neural network for evaluating the compressive strength of concretes: A case of Rice Husk Ash concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 61, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, A.R.; Abbaslou, H.; Amlashi, A.T.; Alidoust, P. Modeling of bentonite/sepiolite plastic concrete compressive strength using artificial neural network and support vector machine. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2019, 13, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arachchilage, C.B.; Fan, C.; Zhao, J.; Arachchilage, C.B.; Fan, C.; Zhao, J.; Huang, G.; Liu, W.V. A machine learning model to predict unconfined compressive strength of alkali-activated slag-based cemented paste backfill. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 15, 2803–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Hu, J.; Hu, C.; Deng, F. Strength prediction of paste filling material based on convolutional neural network. Comput. Intell. 2021, 37, 1355–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Zheng, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, Q.; Wu, M. Application of deep neural network in the strength prediction of cemented paste backfill based on a global dataset. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 391, 131827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, K.; Chen, D.; Han, B.; Hu, Y.; Liu, B. Exploration of the use of superfine tailings and ternary solid waste-based binder to prepare environmentally friendly backfilling materials: Hydration mechanisms and machine learning modeling. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, K.; Han, B. Distribution characterization and strength prediction of backfill in underhand drift stopes based on sparrow search algorithm-extreme learning machine and field experiments. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Li, J.; Xiong, X.; Zhou, K. Application of a Multi-Algorithm-Optimized CatBoost Model in Predicting the Strength of Multi-Source Solid Waste Backfilling Materials. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xu, D.; Li, K.; Ni, W. Study on the Solidification Mechanism of Cr in Ettringite and Friedel’s Salt. Metals 2022, 12, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, K.; Huang, X.; Ni, W.; Zhang, S. Preparation of backfill materials by solidifying municipal solid waste incineration fly ash with slag-based cementitious materials. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 2745–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wang, D.; Yu, H.; Gong, Z.; He, Y.; Guo, J. Application of machine learning to predict the fluoride removal capability of MgO. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, S.; Wang, M. Comparative prediction performance of the strength of a new type of Ti tailings cemented backfilling body using PSO-RF, SSA-RF, and WOA-RF models. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yu, H.; He, Y.; Guo, J.; Min, G.; Wang, J. Optimization and interpretability analysis of machine learning methods for ZnO colloid particle size prediction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 2682–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Onyelowe, K.C.; Mahmood, M.S.; Qureshi, M.Z.; Ben Kahla, N.; Rezzoug, A.; Deifalla, A. Advanced and hybrid machine learning techniques for predicting compressive strength in palm oil fuel ash-modified concrete with SHAP analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Guan, T.; Chen, P.; Ren, B.; Guo, Z. Intelligent prediction of compressive strength of concrete based on CNN-BiLSTM-MA. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jayathilakage, R.; Liu, Y.; Hajimohammadi, A. Intelligent compressive strength prediction of sustainable rubberised concrete using an optimised interpretable deep CNN-LSTM model with attention mechanism. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 185, 113993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xia, P.; Chen, K.; Gong, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, W. Prediction and optimization model of sustainable concrete properties using machine learning, deep learning and swarm intelligence: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, M.; Gamage, K.A.A.; Kamran, M.; Rasheed, M.B. Hyperparameter Optimization of Bayesian Neural Network Using Bayesian Optimization and Intelligent Feature Engineering for Load Forecasting. Sensors 2022, 22, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabar, M.E.; Katlav, M.; Turk, K. Explainable ensemble algorithms with grey wolf optimization for estimation of the tensile performance of polyethylene fiber-reinforced engineered cementitious composite. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 44, 112028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadkhodaei, M.H.; Ghasemi, E. Interpretable real-time monitoring of short-term rockbursts in underground spaces based on microseismic activities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 14, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saneep, K.; Sundareswaran, K.; Nayak, P.S.R.; Puthusserry, G.V. State of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries using PSO optimized random forest algorithm and performance analysis. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114 Pt B, 115879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshdel Sangdeh, M.; Salimi, M.; Hakimi Khansar, H.; Dokaneh, M.; Zanganeh Ranjbar, P.; Payan, M.; Arabani, M. Predicting the precipitated calcium carbonate and unconfined compressive strength of bio-mediated sands through robust hybrid optimization algorithms. Transp. Geotech. 2024, 46, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Oh, S. Hybrid-Recursive Feature Elimination for Efficient Feature Selection. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sen, S.; Sinha, S.; Kumar, B.; Nidhi, C. Prediction of compressive strength of concrete doped with waste plastic using machine learning-based advanced regularized regression models. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 26, 1723–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliappan, J.; Srinivasan, K.; Qaisar, S.M.; Sundararajan, K.; Chang, C.-Y.; Suganthan, C. Performance Evaluation of Regression Models for the Prediction of the COVID-19 Reproduction Rate. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 729795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, J.; Guo, B.; Zhong, T.; Guan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Niu, D. Explainable machine learning model for predicting compressive strength of CO2-cured concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.; Wilhelm, P.V.B.; Amancio, D.R. Machine learning and economic forecasting: The role of international trade networks. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2024, 649, 129977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; As’Arry, A.; Hassan, M.K.; Hairuddin, A.A.; Mohamad, H. Review of the grey wolf optimization algorithm: Variants and applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajulu, V.S. AI-Driven Mission-Critical Software Optimization for Small Satellites: Integrating an Automated Testing Framework. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.; Khan, K.A.; Ahmad, T.; Alam, M.; Bashir, M.T. Influence of accelerated curing on the compressive strength of polymer-modified concrete. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2022, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.-H.; Huang, R.; Wu, Y.-H.; Tsai, C.-J.; Lai, H.-W. Influence of sulfur trioxide on volume change and compressive strength of eco-mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 114, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.M.; Rahman, M.R.; Phing, C.Y.W.; Chie, A.W.M.; Bakri, M.K.B. The curing times effect on the strength of ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 120622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, H.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, C. Reaction kinetics, mechanical properties, and microstructure of nano-modified recycled concrete fine powder/slag based geopolymers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 372, 133715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, J. Research on Slurry Flowability and Mechanical Properties of Cemented Paste Backfill: Effects of Cement-to-Tailings Mass Ratio and Mass Concentration. Materials 2024, 17, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | CaO | Cl | SiO2 | MgO | SO3 | Na2O | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | K2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fly ash | 39.85 | 22.45 | 4.32 | 3.93 | 10.28 | 5.99 | 1.59 | 2.03 | 5.96 |

| slag | 40.86 | 0.03 | 29.27 | 9.75 | 1.48 | 0.32 | 14.76 | 1.46 | 0.46 |

| desulfurization gypsum | 50.96 | 0.26 | 3.85 | 1.47 | 40.37 | 1.37 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 50.96 |

| tailings | 16.36 | 0.04 | 50.62 | 8.02 | 1.32 | 7.48 | 11.54 | 2.00 | 16.36 |

| Feature | Feature Name | Mean | Min | Max | Median | Std Dev | Q25% | Q75% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Slag | 255.69 | 0.00 | 450.00 | 300.00 | 106.73 | 200.00 | 300.00 |

| X2 | Fly ash | 148.43 | 0.00 | 450.00 | 150.00 | 97.37 | 68.00 | 150.00 |

| X3 | Desulfurization gypsum | 44.94 | 15.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 10.78 | 50.00 | 50.00 |

| X4 | Tailings | 2247.02 | 2000.00 | 4000.00 | 2000.00 | 518.39 | 2000.00 | 2273.00 |

| X5 | Water | 682.03 | 476.00 | 987.80 | 625.00 | 127.47 | 625.00 | 705.13 |

| X6 | Calcium oxide | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| X7 | Iron oxide | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| X8 | Silicon dioxide | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 0.46 |

| X9 | Aluminum oxide | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| X10 | Sulfur trioxide | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| X11 | Chlorine | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| X12 | Potassium sodium oxide | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| X13 | Curing time | 92.10 | 3.00 | 360.00 | 28.00 | 118.35 | 7.00 | 180.00 |

| X14 | Concentration | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| X15 | Compressive strength | 13.58 | 0.11 | 46.42 | 11.43 | 10.80 | 4.02 | 20.62 |

| Optimization-Model Abbreviation | Parameters | Features |

|---|---|---|

| RF | {‘max_depth’: None (5–30), ‘n_estimators’: 100 (50–500), ‘min_samples_split’: 2 (2–20), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 1 (1–10)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| GBDT | {‘max_depth’: 3 (3–10), ‘n_estimators’: 100 (50–500), ‘min_samples_split’: 2 (2–20), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 1 (1–10), ‘learning_rate’: 0.1 (0.01–0.3)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| LGBM | {‘num_leaves’: 31 (10–128), ‘max_depth’: 6 (5–30), ‘n_estimators’: 100 (50–500), ‘learning_rate’: 0.1 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_child_samples’: 20 (1–50)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| CNN | {‘filters1′: 32 (16–128), ‘filters2′: 32 (16–128), ‘kernel_size’: 3 (2–5), ‘dense_units’: 64 (32–128), ‘dropout_rate’: 0.2 (0.1–0.5), ‘learning_rate’: 0.001 (0.0001–0.01)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| GS-RF | {‘max_depth’: 10 (5–30), ‘n_estimators’: 100 (50–500), ‘min_samples_split’: 2 (2–20), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 1 (1–10)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| GS-GB | {‘max_depth’: 3 (3–10), ‘n_estimators’: 100 (50–500), ‘learning_rate’: 0.1 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_split’: 2 (2–20), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 1 (1–10)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| GS-LGBM | {‘max_depth’: −1 (5–30), ‘n_estimators’: 100 (50–1000), ‘learning_rate’: 0.1 (0.01–0.3), ‘num_leaves’: 31 (10–128), ‘min_child_samples’: 20 (1–50)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-BO-RF | {‘max_depth’: 10 (5–30), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 1 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 6 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 94 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-GWO-RF | {‘max_depth’: 5 (5–30), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 9 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 6 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 158 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-WOA-RF | {‘max_depth’: 5 (5–30), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 7 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 2 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 65 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-PSO-RF | {‘max_depth’: 8 (5–30), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 1 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 5 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 101 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Silicon dioxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-BO-GB | {‘max_depth’: 4 (5–30), ‘learning_rate’: 0.17817087100112233 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 9 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 18 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 148 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Water’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-GWO-GB | {‘max_depth’: 5 (5–30), ‘learning_rate’: 0.17028188992197366 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 4 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 4 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 101 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Water’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-WOA-GB | {‘max_depth’: 8 (5–30), ‘learning_rate’: 0.10333208140151896 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 1 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 15 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 128 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Water’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-PSO-GB | {‘max_depth’: 7 (5–30), ‘learning_rate’: 0.18642056953682531 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 3 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 3 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 64 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Water’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-BO-LGBM | {‘max_depth’: 7 (5–30), ‘learning_rate’: 0.2 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 7 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 16 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 143 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’] |

| RFE-GWO-LGBM | {‘max_depth’: 8 (5–30), ‘learning_rate’: 0.031555063806171034 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 8 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 19 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 50 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’] |

| RFE-WOA-LGBM | {‘max_depth’: 5 (5–30), ‘learning_rate’: 0.17537439537639113 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 8 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 12 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 87 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’] |

| RFE-PSO-LGBM | {‘max_depth’: 4 (5–30), ‘learning_rate’: 0.14414451841810513 (0.01–0.3), ‘min_samples_leaf’: 4 (1–10), ‘min_samples_split’: 2 (2–20), ‘n_estimators’: 172 (100–1000)} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Calcium oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Chlorine’, ‘Potassium sodium oxide’, ‘Curing time’] |

| RFE-BO-CNN | {‘learning_rate’: 0.005577 (0.0001–0.1), ‘batch_size’: 30 (16–256), ‘epochs’: 98, ‘filters1′: 50 (16–256), ‘kernel_size’: 4 (3–7), ‘filters2′: 65, ‘dense_units’: 109 (64–512), ‘validation_MSE’: 9.3207} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Curing stime’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-GWO-CNN | {‘learning_rate’: 0.009306 (0.0001–0.1), ‘batch_size’: 33 (16–256), ‘epochs’: 37, ‘filters1′: 96 (16–256), ‘kernel_size’: 5 (3–7), ‘filters2′: 28, ‘dense_units’: 171 (64–512), ‘validation_MSE’: 22.4184} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-WOA-CNN | {‘learning_rate’: 0.009197 (0.0001–0.1), ‘batch_size’: 109 (16–256), ‘epochs’: 98, ‘filters1′: 126 (16–256), ‘kernel_size’: 5 (3–7), ‘filters2′: 126, ‘dense_units’: 251 (64–512), ‘validation_MSE’: 26.3298} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| RFE-PSO-CNN | {‘learning_rate’: 0.005293 (0.0001–0.1), ‘batch_size’: 20 (16–256), ‘epochs’: 31, ‘filters1′: 109 (16–256), ‘kernel_size’: 4 (3–7), ‘filters2′: 65, ‘dense_units’: 131 (64–512), ‘validation_MSE’: 18.7533} | [‘Slag’, ‘Fly ash’, ‘Desulfurization gypsum’, ‘Tailings’, ‘Water’, ‘Iron(III) oxide’, ‘Aluminum oxide’, ‘Sulfur trioxide’, ‘Curing time’, ‘Concentration’] |

| Model-Algorithm Combination | Training Set R2 | Training Set MAE | Training Set MSE | Training Set RAE | Testing Set R2 | Testing Set MAE | Testing Set MSE | Testing Set RAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.866 ± 0.003 | 2.765 ± 0.082 | 16.098 ± 0.456 | 0.307 ± 0.005 | 0.824 ± 0.004 | 3.236 ± 0.101 | 18.662 ± 0.582 | 0.373 ± 0.006 |

| GB | 0.869 ± 0.002 | 2.550 ± 0.068 | 15.540 ± 0.389 | 0.284 ± 0.004 | 0.863 ± 0.003 | 2.798 ± 0.089 | 14.484 ± 0.498 | 0.323 ± 0.005 |

| LGBM | 0.759 ± 0.005 | 4.061 ± 0.125 | 30.037 ± 0.872 | 0.450 ± 0.007 | 0.668 ± 0.006 | 4.355 ± 0.142 | 35.156 ± 1.038 | 0.502 ± 0.008 |

| CNN | 0.493 ± 0.007 | 6.468 ± 0.183 | 60.666 ± 1.621 | 0.725 ± 0.009 | 0.335 ± 0.008 | 6.607 ± 0.194 | 70.302 ± 1.745 | 0.762 ± 0.010 |

| GS-RF | 0.867 ± 0.002 | 2.773 ± 0.079 | 16.064 ± 0.421 | 0.308 ± 0.004 | 0.823 ± 0.003 | 3.252 ± 0.097 | 18.708 ± 0.551 | 0.375 ± 0.005 |

| GS-GB | 0.869 ± 0.002 | 2.550 ± 0.067 | 15.540 ± 0.385 | 0.284 ± 0.004 | 0.863 ± 0.003 | 2.798 ± 0.088 | 14.484 ± 0.495 | 0.323 ± 0.005 |

| GS-LGBM | 0.759 ± 0.005 | 4.061 ± 0.123 | 30.037 ± 0.865 | 0.450 ± 0.007 | 0.668 ± 0.006 | 4.355 ± 0.140 | 35.156 ± 1.030 | 0.502 ± 0.008 |

| GS-CNN | 0.517 ± 0.006 | 6.177 ± 0.167 | 57.455 ± 1.512 | 0.690 ± 0.008 | 0.465 ± 0.007 | 5.944 ± 0.176 | 56.573 ± 1.638 | 0.685 ± 0.009 |

| RFE-BO-RF | 0.724 ± 0.004 | 4.569 ± 0.131 | 32.976 ± 0.913 | 0.506 ± 0.006 | 0.564 ± 0.005 | 5.333 ± 0.144 | 46.078 ± 1.281 | 0.615 ± 0.007 |

| RFE-GWO-RF | 0.975 ± 0.001 | 1.173 ± 0.021 | 2.998 ± 0.058 | 0.130 ± 0.002 | 0.884 ± 0.002 | 2.747 ± 0.048 | 12.288 ± 0.132 | 0.317 ± 0.003 |

| RFE-WOA-RF | 0.972 ± 0.001 | 1.276 ± 0.024 | 3.306 ± 0.064 | 0.141 ± 0.002 | 0.849 ± 0.003 | 3.017 ± 0.052 | 15.925 ± 0.145 | 0.348 ± 0.003 |

| RFE-PSO-RF | 0.979 ± 0.001 | 1.052 ± 0.018 | 2.479 ± 0.049 | 0.116 ± 0.002 | 0.871 ± 0.002 | 2.794 ± 0.042 | 13.663 ± 0.121 | 0.322 ± 0.003 |

| RFE-BO-GB | 0.998 ± 0.000 | 0.293 ± 0.003 | 0.186 ± 0.001 | 0.032 ± 0.000 | 0.932 ± 0.001 | 2.180 ± 0.031 | 7.243 ± 0.086 | 0.251 ± 0.001 |

| RFE-GWO-GB | 0.999 ± 0.000 | 0.088 ± 0.001 | 0.083 ± 0.000 | 0.010 ± 0.000 | 0.934 ± 0.001 | 1.937 ± 0.028 | 7.031 ± 0.077 | 0.223 ± 0.001 |

| RFE-WOA-GB | 0.996 ± 0.000 | 0.392 ± 0.004 | 0.434 ± 0.002 | 0.043 ± 0.000 | 0.931 ± 0.001 | 2.023 ± 0.030 | 7.269 ± 0.080 | 0.233 ± 0.001 |

| RFE-PSO-GB | 0.990 ± 0.000 | 0.620 ± 0.005 | 1.242 ± 0.003 | 0.069 ± 0.000 | 0.909 ± 0.001 | 2.368 ± 0.037 | 9.646 ± 0.098 | 0.273 ± 0.001 |

| RFE-BO-LGBM | 0.940 ± 0.001 | 1.554 ± 0.022 | 7.194 ± 0.059 | 0.172 ± 0.002 | 0.871 ± 0.002 | 2.604 ± 0.035 | 13.606 ± 0.096 | 0.300 ± 0.002 |

| RFE-GWO-LGBM | 0.928 ± 0.001 | 1.875 ± 0.026 | 8.625 ± 0.068 | 0.207 ± 0.002 | 0.868 ± 0.002 | 2.827 ± 0.039 | 13.980 ± 0.099 | 0.326 ± 0.002 |

| RFE-WOA-LGBM | 0.927 ± 0.001 | 1.902 ± 0.027 | 8.692 ± 0.070 | 0.210 ± 0.002 | 0.870 ± 0.002 | 2.776 ± 0.038 | 13.783 ± 0.098 | 0.320 ± 0.002 |

| RFE-PSO-LGBM | 0.927 ± 0.001 | 1.902 ± 0.027 | 8.692 ± 0.070 | 0.210 ± 0.002 | 0.870 ± 0.002 | 2.776 ± 0.038 | 13.783 ± 0.098 | 0.320 ± 0.002 |

| RFE-BO-CNN | 0.902 ± 0.001 | 2.621 ± 0.041 | 11.661 ± 0.109 | 0.290 ± 0.003 | 0.804 ± 0.003 | 3.250 ± 0.053 | 20.683 ± 0.141 | 0.375 ± 0.004 |

| RFE-GWO-CNN | 0.937 ± 0.001 | 2.200 ± 0.032 | 7.584 ± 0.088 | 0.244 ± 0.002 | 0.820 ± 0.003 | 3.428 ± 0.046 | 19.072 ± 0.126 | 0.395 ± 0.003 |

| RFE-WOA-CNN | 0.949 ± 0.001 | 1.826 ± 0.028 | 6.115 ± 0.076 | 0.202 ± 0.002 | 0.856 ± 0.003 | 2.842 ± 0.040 | 15.220 ± 0.111 | 0.328 ± 0.003 |

| RFE-PSO-CNN | 0.926 ± 0.001 | 2.274 ± 0.036 | 8.803 ± 0.097 | 0.252 ± 0.002 | 0.839 ± 0.003 | 2.903 ± 0.043 | 16.990 ± 0.129 | 0.335 ± 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, T.; Zhang, S.; Ni, W. Predicting the Strength of Fly Ash–Slag–Gypsum-Based Backfill Materials Using Interpretable Machine Learning Modeling. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212035

Fan T, Zhang S, Ni W. Predicting the Strength of Fly Ash–Slag–Gypsum-Based Backfill Materials Using Interpretable Machine Learning Modeling. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212035

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Tingdi, Siqi Zhang, and Wen Ni. 2025. "Predicting the Strength of Fly Ash–Slag–Gypsum-Based Backfill Materials Using Interpretable Machine Learning Modeling" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212035

APA StyleFan, T., Zhang, S., & Ni, W. (2025). Predicting the Strength of Fly Ash–Slag–Gypsum-Based Backfill Materials Using Interpretable Machine Learning Modeling. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212035