A New Approach to Forecast Intermittent Demand and Stock-Keeping-Unit Level Optimization for Spare Parts Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and State of the Art in Spare Parts Demand Forecasting

1.2. Objectives and Structure of the Article

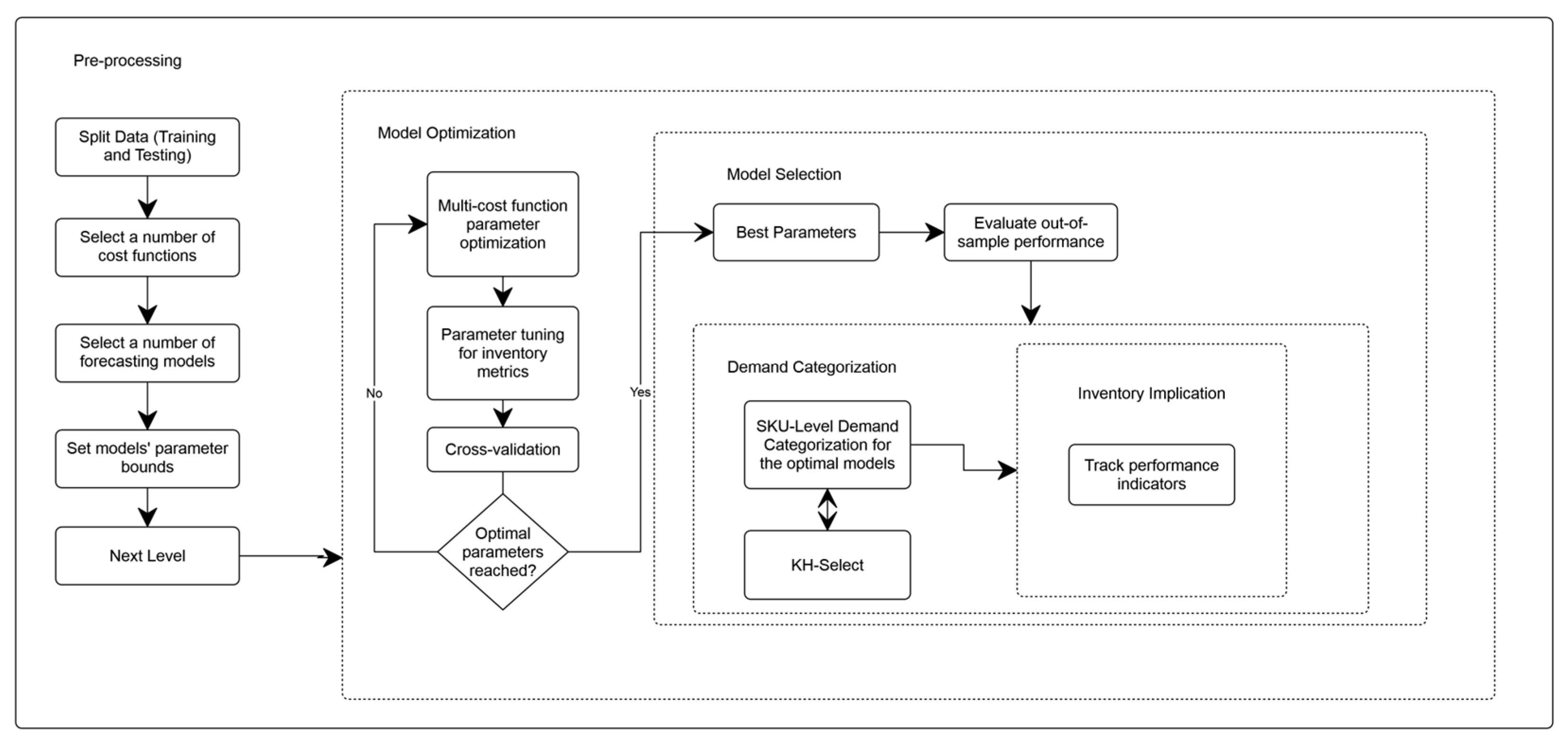

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context, Data, and Preprocessing

2.2. Forecasting Models: Scope, Comparators, and Proposed Methods

- Croston-type models: Croston decomposes demand into a non-zero demand size and an inter-demand interval, each updated by exponential smoothing; the per-period forecast is the ratio of these components [4]. Its positive bias motivated the Syntetos–Boylan Approximation (SBA), which reduces overestimation under intermittence [6];

- Probability-of-occurrence models: Teunter–Syntetos–Babai (TSB) replaces inter-demand intervals with a demand-occurrence probability updated every period, while the demand-size component is updated only when non-zero demand occurs, thereby accommodating obsolescence and declining usage [8];

- Modified Croston variants: mSBA updates the inter-demand interval during zero-demand runs by comparing observed and estimated spacing; mTSB analogously updates the occurrence probability during zero-demand periods [33].

- Sfiris–Koulouriotis (SK): Retains TSB’s probability-of-occurrence concept but estimates occurrence non-parametrically as the ratio of non-zero to zero occurrences within an online window, reducing free parameters and enabling responsive updates;

- SK–SSA: Applies a Singular Spectrum Analysis–inspired stabilization to highly lumpy sequences prior to the SK updating scheme to improve robustness.

2.3. Error Metrics, Cost Functions, and Optimization Objective

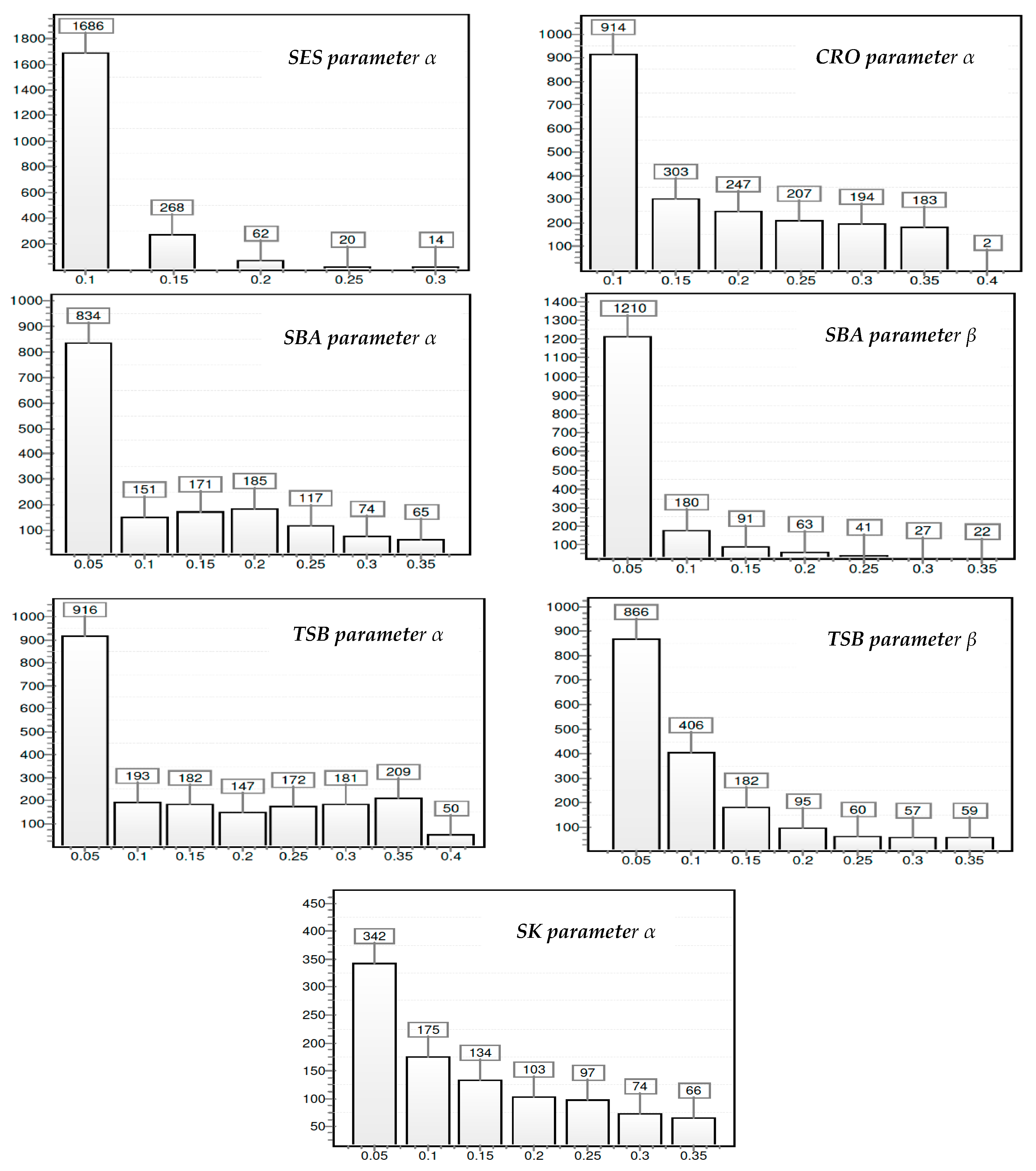

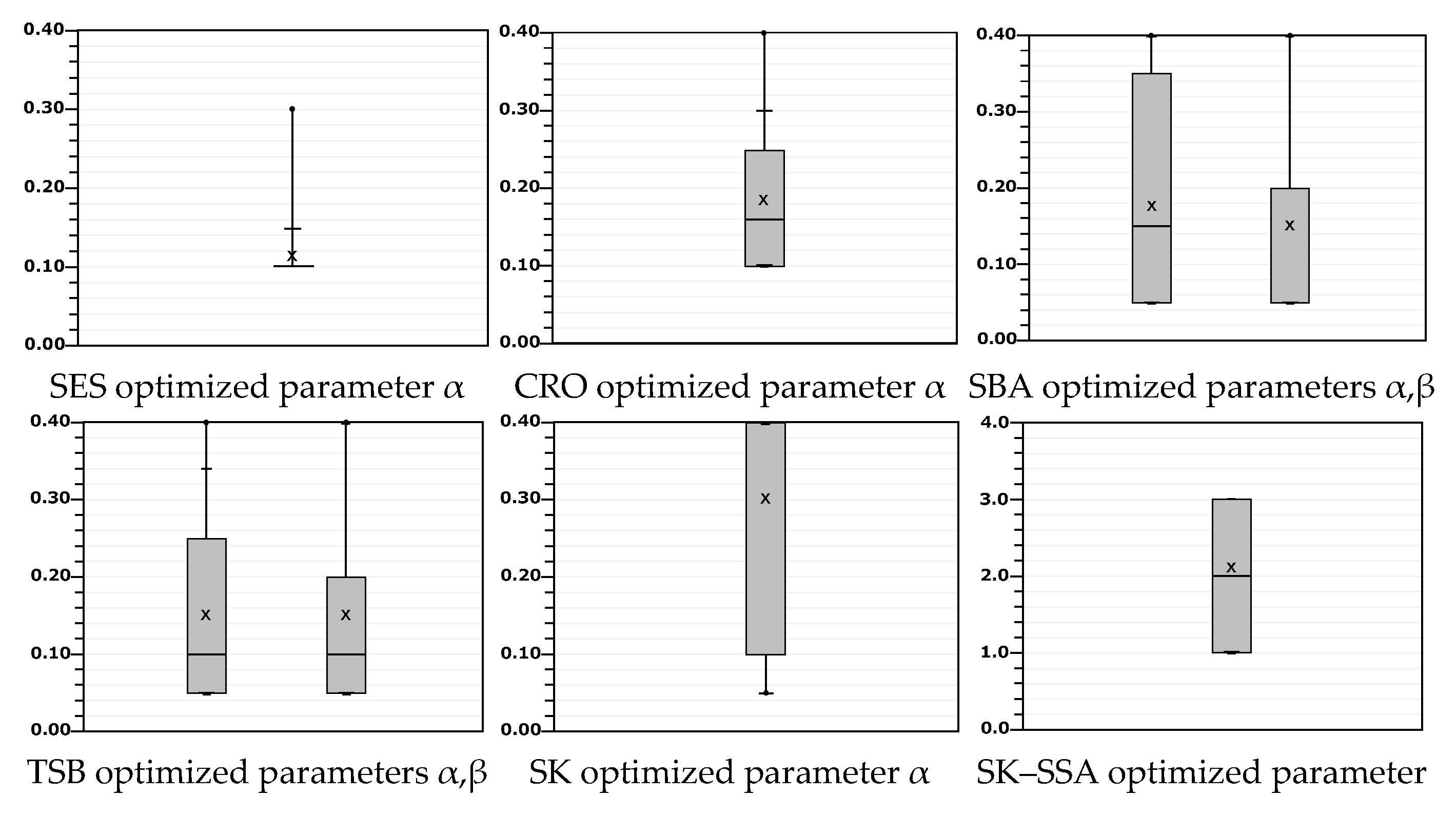

2.4. Optimization Framework, Training Protocol, and Computing Setup

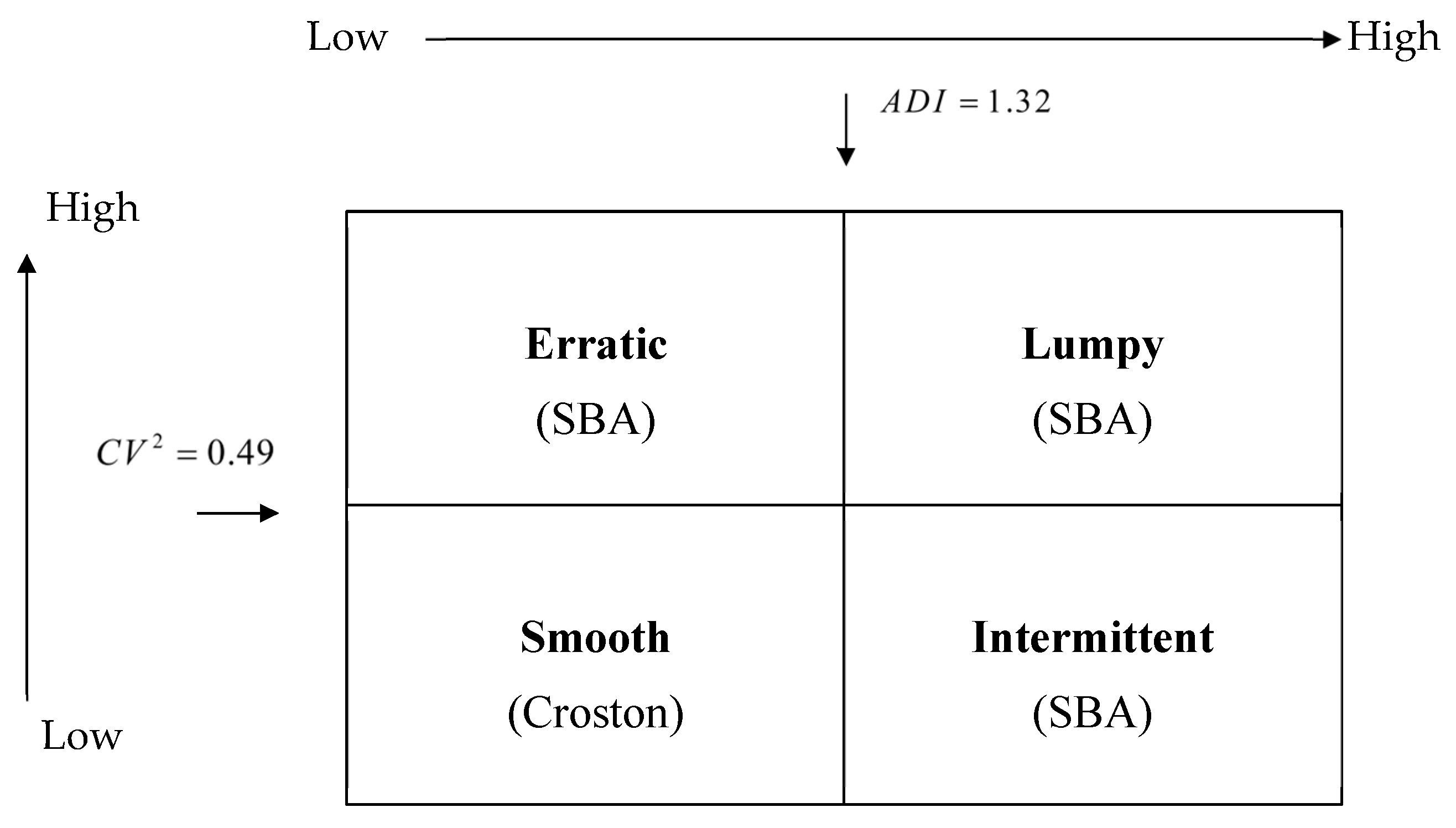

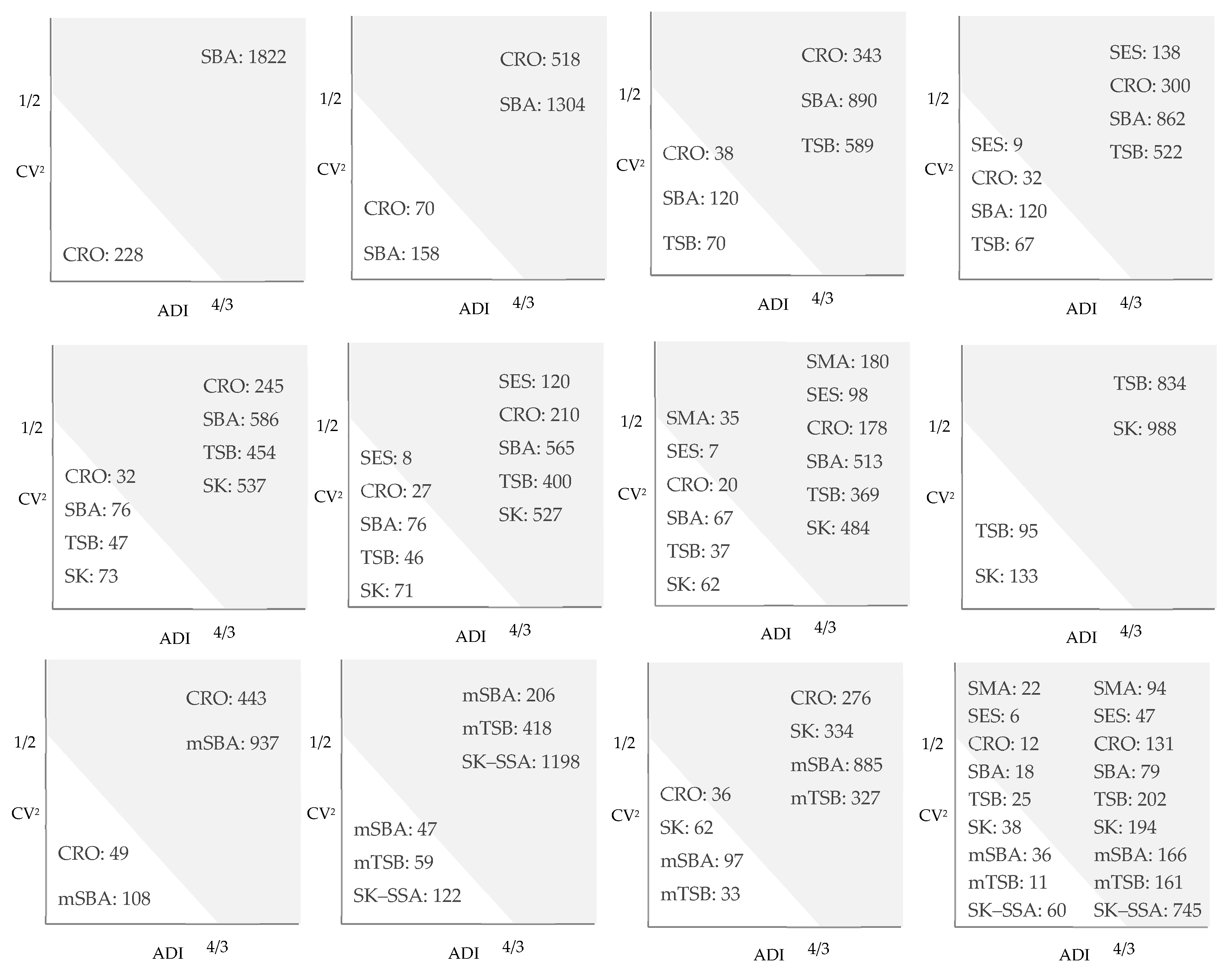

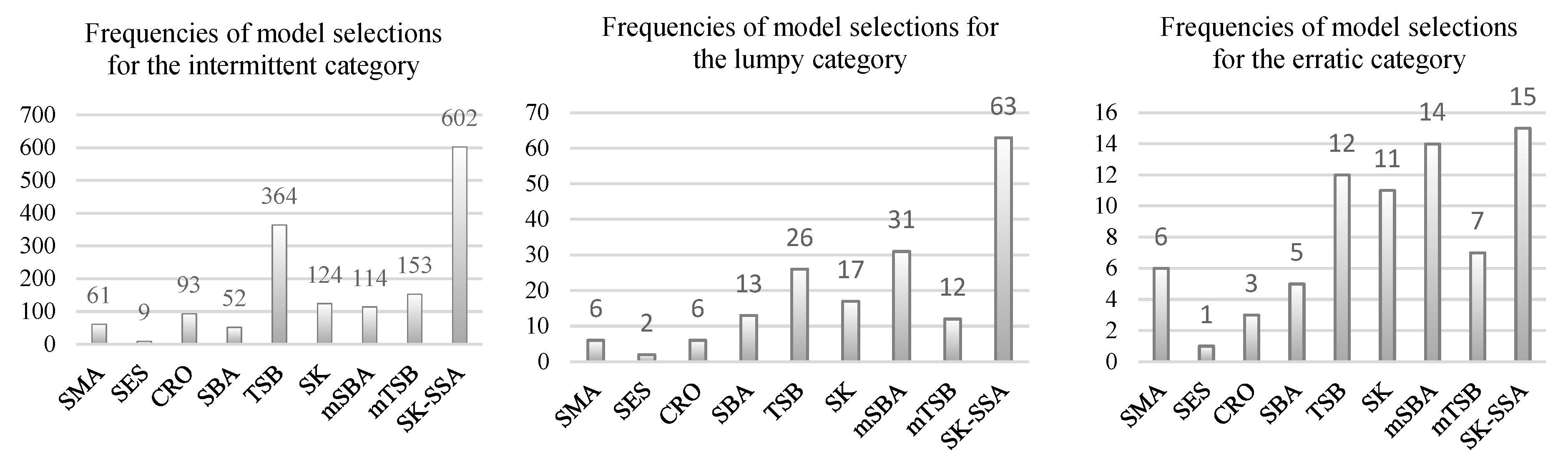

2.5. Demand Pattern Classification and Methods Grouping

- Smooth: and ; typically fast-moving items.

- Intermittent: and ; sparse arrivals with relatively stable non-zero sizes.

- Erratic: and ; frequent demand with volatile size.

- Lumpy: and ; long zero runs and highly variable non-zero sizes.

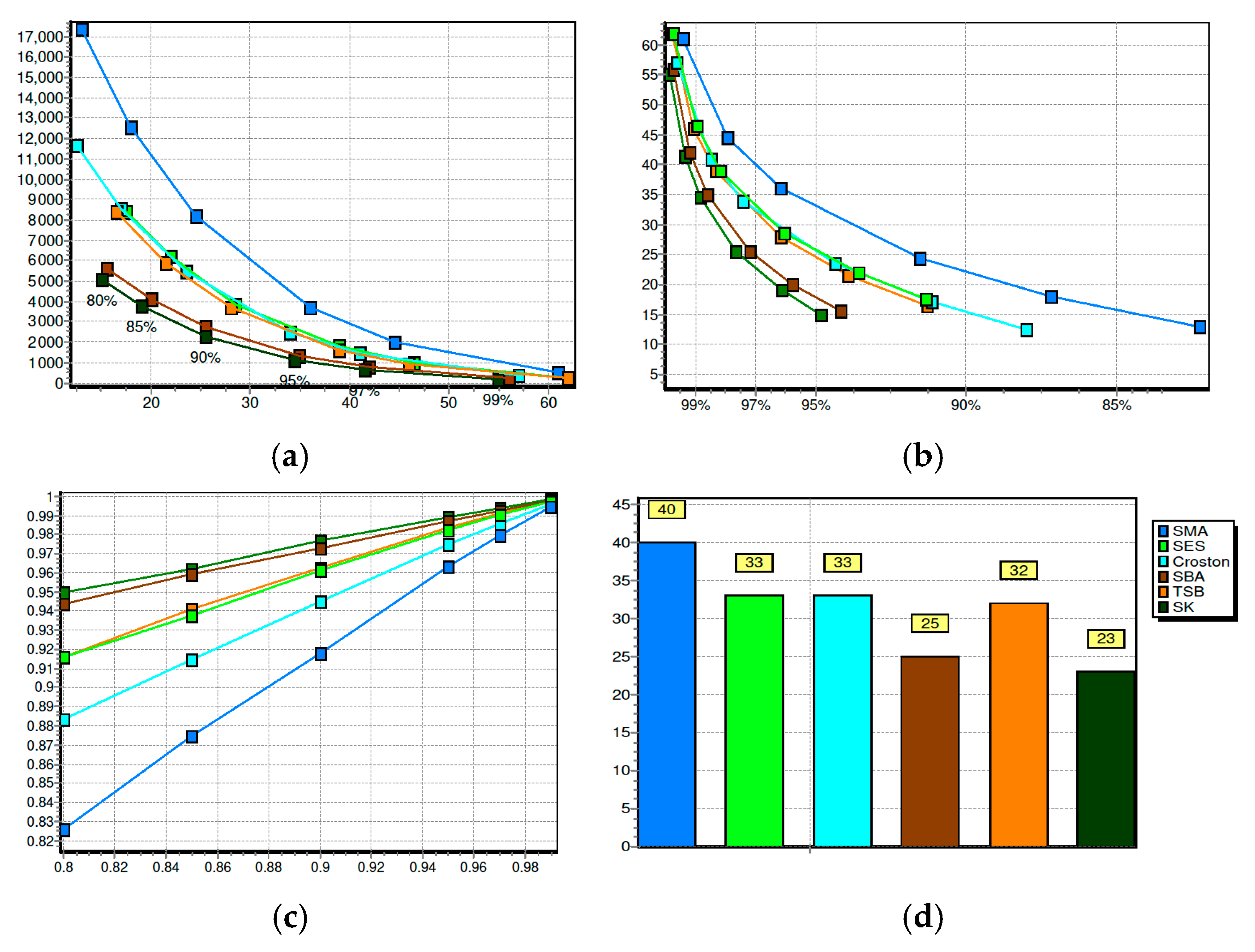

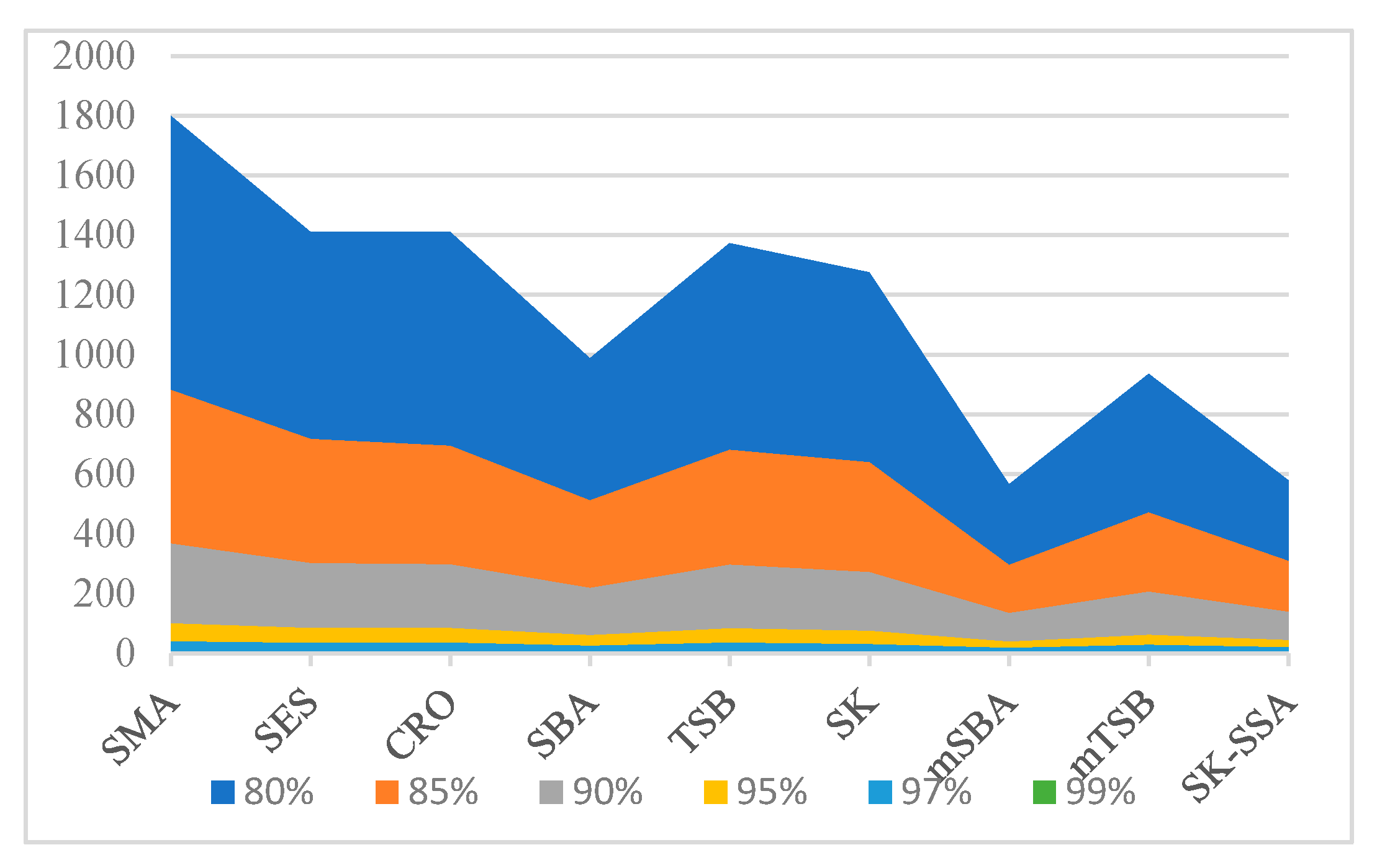

2.6. Inventory Control Model and Lead-Time Demand Specification

2.7. Statistical Testing, Robustness Analysis, and Addressed Research Gaps

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Objective selection matters. Choosing an inventory-aligned cost (sSPEC) for parameter tuning leads to materially different and better inventory outcomes than traditional errors alone;

- Method diversity pays. Maintaining a small, interpretable pool (CRO, SBA, TSB, modified variants, SK, SK–SSA) and selecting per SKU via MCOST improves both accuracy and stockholding/backorder trade-offs;

- Policy robustness. Using NBB for LTD within an (R,Q) policy yields stable reorder points and safety stock across service-level targets, with clear trade-offs (Figure 7) that support policy communication.

- Forecasting

- -

- Enlarge the candidate pool with additional intermittent-aware models.

- -

- Develop hybrid SK variants that combine probability updates with regime detection.

- -

- Investigate joint tuning with SSA windowing.

- Objectives

- -

- Compare sSPEC with alternative cost-to-serve surrogates.

- -

- Explore dynamic weighting between opportunity and stock-keeping costs.

- -

- Extend MCOST to multi-horizon settings or service-level-constrained tuning.

- Inventory

- -

- Generalize LTD to composite models with stochastic lead time.

- -

- Integrate maintenance signals or condition-based triggers (e.g., advance demand information, semi-Markov maintenance coupling) for anticipatory planning.

- -

- Evaluate deterioration-risk-aware replenishment policies for items subject to obsolescence or shelf-life constraints.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Algorithmic and Methodological Details

| Algorithm A1. Sfiris–Koulouriotis (SK) forecasting: exponential smoothing of non-zero size and non-parametric estimation of occurrence probability. |

Input:

if else 0 // Size update (Equation (7), only on non-zero periods): if : else: // unchanged through zero runs // Occurrence estimate (Equations (8)–(12)): // cumulative form: // Equation (9) gives stable start; tends to as grows // windowed (optional): If using window : update : add ; drop when If option A (plain window): If option B (light Laplace for window): // stabilizes early windows If blend (Equation (12), optional): else (no blend): else (no window provided): // Clip to avoid degeneracy: // Section 2.2 safeguard // One-step-ahead forecast (Equation (6)): Output: // O(1) per period; O(T) per series with constant memory |

| Algorithm A2. SK–SSA: SSA-stabilized non-zero size used within the SK update; occurrence remains non-parametric. |

Input:

if else 0. // Size update (SSA-stabilized; Equation (15)): if : else: Enforce // Occurrence update (non-parametric, as in Algorithm A1) Update as in Algorithm A1 (cumulative, windowed, or blended non-parametric estimator), with clipping to // Forecast (Equation (6)): Output: Notes: SSA is applied only to sizes (not to the zero/non-zero occurrence process). |

| Algorithm A3. Per-SKU MCOST selection with within-bounds success weighting and out-of-sample evaluation. This procedure implements the cost-first design (choose objective → tune) and the success-weighted case adjustment exactly as in Equations (27)–(30). |

Input:

For each SKU i = 1..N: For each method m ∈ M and objective c ∈ C:

For each j ∈ M and i ∈ C:

Preferred cost // Phase III—Final per-SKU selection under preferred costs (per SKU): For SKU i:

Feed the selected forecast for SKU i into the NBB LTD model to set (R,Q), compute safety stock, and evaluate service/backorders as in Section 2.6. Output: Best method/parameters per SKU; NBB policy metrics |

| Step | Operation | Input(s) | Output(s) | Purpose/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Preparation | Construct per-SKU weekly demand series (length = 104 periods) | Raw demand transactions | Cleaned, zero-padded weekly series | Align time frames, remove invalid entries |

| 2. Define Model Pool | Select forecasting methods: SMA, SES, CRO, SBA, TSB, SK, mSBA, mTSB, SK–SSA | – | Model set M = {9 methods} | Includes all Croston-family and new SK variants |

| 3. Define Objective Pool | Select optimization criteria: MSE, MAE, PIS, MAR, MSR, SPEC | – | Objective set C = {6 costs} | Covers level-based, rate-based, and inventory-linked losses |

| 4. Rolling-Origin Evaluation | For each (method, cost) pair, forecast one step ahead using expanding-window rolling origins | M, C, historical demand | Forecasts and in-sample loss trajectories | Captures evolving dynamics and parameter adaptation |

| 5. Parameter Optimization | Minimize chosen cost function within method’s parameter bounds | Loss per (method, cost) | Optimal parameter vector θ* | Retain best parameters per SKU and cost |

| 6. Boundary Check | Identify parameter solutions hitting limits of search grid | θ*, parameter bounds | Success indicator (1 = within bounds) | Used later for adjusted rankings |

| 7. Compute Out-of-Sample Performance | Evaluate each (method, cost) on reserved test window | Optimized θ* | Out-of-sample loss (e.g., sSPEC, MASE) | Enables cross-method comparison |

| 8. Adjusted Ranking Matrix (Equation (30)) | Combine within-bounds average loss and overall loss weighted by success rate | All per-SKU results | Adjusted R ranking matrix | Prevents overranking boundary-dominated cases |

| 9. Preferred Cost per Method | For each method, identify the cost objective yielding lowest adjusted average loss | R | Best objective per method | Implements “cost-first” optimization philosophy |

| 10. Final Per-SKU Selection | Among all methods optimized under their preferred cost, select method with lowest test loss | Per-SKU results | Chosen model–cost–parameter triple | Final MCOST-optimized forecast per SKU |

| 11. Inventory Evaluation | Map forecasts to continuous-review (R,Q) policy with NBB LTD | Forecasts, lead time | Scaled safety stock, backlog metrics | Quantifies operational outcomes |

Appendix B. Symbols and Notation

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Observed demand in period (zero or non-zero) | |

| Indicator of non-zero demand in period | |

| Cumulative count of non-zero periods | |

| Non-zero demand size observed at (only when ) | |

| Non-zero demand size forecast (smoothed estimate) at | |

| Inter-demand interval observed at | |

| Inter-demand interval forecast (smoothed estimate) at | |

| Forecast of demand steps ahead made at | |

| Demand rate in period (in-sample values) | |

| Number of in-sample periods | |

| Forecast horizon (look-ahead) | |

| Smoothing parameters (method-dependent) | |

| Occurrence probability in period | |

| Estimated occurrence probability at | |

| Window length and available window () | |

| Blend weight between windowed and cumulative estimators | |

| Laplace correction parameters | |

| ε | Small positive lower bound (size floor) applied to prevent numerical underflow in non-zero size updates (typical value ε = 10−6). |

| δ | Probability clipping constant to keep the occurrence estimate within (δ, 1 − δ) during cumulative/windowed/blended updates (typical value δ = 10−6). |

| SSA window (embedding) length used to form the trajectory matrix for size-series reconstruction in SK–SSA. | |

| k | Number of leading SSA components retained in the reconstruction (controls smoothing strength) in SK–SSA. |

| SSA-smoothed demand series at using window and reconstructed components | |

| SSA-smoothed non-zero demand size at | |

| ADI | Average inter-demand interval (Equation (31)). |

| Squared coefficient of variation of non-zero demand sizes (Equation (32)). | |

| KH-Select | Kourentzes–Hyndman classification |

| MCOST | Multi-cost optimization (per sku and model selection) |

| Sets of forecasting methods | |

| Set of cost/accuracy objectives | |

| Out-of-sample loss for each method () and cost objective . | |

| Adjusted MCOST score (Equation (30)) blending within-bounds success. | |

| LTD | Lead-time demand random variable |

| Safety Stock | |

| (R,Q) continuous-review policy parameters (reorder point, order quantity) | |

| Supplier lead time (days) | |

| NB, Bernoulli | Negative binomial size; Bernoulli occurrence |

| NBB | Negative-binomial-Bernoulli (composite NBB LTD) |

| sSPEC | Scaled stock-keeping-unit-oriented prediction error costs |

| sAPIS | Scaled absolute periods in stock |

| MASE | Mean absolute scaled error |

| MSR, MAR | Mean squared/absolute eate |

| PIS, APIS | Periods in stock/absolute PIS |

Appendix C. Extended Robustness and Sensitivity Analysis

| Method A | Method B | Metric | Median Δ (A − B) 1 | 95% CI of Δ | Adjusted p (Holm) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK–SSA | SBA | sSPEC | −0.024 | [−0.030, −0.018] | <0.001 | Highly significant |

| SK–SSA | TSB | sSPEC | −0.021 | [−0.028, −0.014] | <0.001 | Highly significant |

| SK–SSA | mSBA | sSPEC | −0.019 | [−0.027, −0.011] | 0.002 | Significant |

| SK–SSA | mTSB | sSPEC | −0.016 | [−0.024, −0.008] | 0.004 | Significant |

| SK | SBA | sSPEC | −0.012 | [−0.020, −0.004] | 0.018 | Significant |

| SK | TSB | sSPEC | −0.010 | [−0.018, −0.003] | 0.029 | Significant |

| SK | CRO | MASE | −0.005 | [−0.009, −0.002] | 0.042 | Marginal significance |

| SK | SES | MASE | +0.002 | [−0.001, 0.006] | 0.412 | Not significant |

| SBA | TSB | sSPEC | +0.007 | [−0.004, 0.018] | 0.217 | Not significant |

| mSBA | mTSB | sSPEC | −0.004 | [−0.011, 0.003] | 0.385 | Not significant |

| CRO | SES | MASE | +0.001 | [−0.003, 0.004] | 0.761 | Not significant |

| Method A | Comparator | Δ Median 2 | 95% CI [2.5%, 97.5%] | CI Entirely < 0 ? | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK–SSA | CRO | −0.028 | [−0.035, −0.020] | Yes | Strong improvement |

| SK–SSA | SBA | −0.023 | [−0.030, −0.016] | Yes | Strong improvement |

| SK–SSA | TSB | −0.019 | [−0.027, −0.011] | Yes | Significant improvement |

| SK–SSA | mSBA | −0.015 | [−0.024, −0.006] | Yes | Moderate improvement |

| SK–SSA | mTSB | −0.013 | [−0.022, −0.005] | Yes | Moderate improvement |

| SK | CRO | −0.018 | [−0.027, −0.009] | Yes | Improvement |

| SK | SBA | −0.012 | [−0.021, −0.004] | Yes | Significant improvement |

| SK | TSB | −0.010 | [−0.018, −0.002] | Yes | Significant improvement |

| SK | mSBA | −0.006 | [−0.015, +0.002] | No | Borderline/overlapping zero |

| SK | mTSB | −0.005 | [−0.013, +0.004] | No | No significant change |

| Forecasting Method | Demand Class | Objective Tested | % SKUs with Method Unchanged | ΔsSPEC 3 (Median [IQR]) | Within-Bounds Success Rate (%) | Boundary-Hit Share (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRO | All | MAE → SPEC | 83.1 | +0.004 [0.001–0.009] | 97.9 | 2.1 | Stable across objectives; minor drift |

| SBA | Intermittent | MSE → sSPEC | 79.5 | −0.006 [−0.012–0.002] | 96.8 | 3.2 | Slight cost-aligned gain |

| TSB | Lumpy | MAE → sSPEC | 82.7 | −0.008 [−0.015–0.001] | 96.5 | 3.5 | Improved under inventory-aligned tuning |

| mSBA | Lumpy | MSE → MAR | 76.9 | −0.010 [−0.018–0.003] | 95.8 | 4.2 | Sensitive to interval update window |

| mTSB | Erratic | SPEC → sSPEC | 78.3 | −0.007 [−0.013–0.002] | 95.4 | 4.6 | Stable except at long zero runs |

| SK | Intermittent | MAR → sSPEC | 88.6 | −0.012 [−0.019–0.006] | 98.0 | 2.0 | Consistent improvement under cost-based tuning |

| SK–SSA | Lumpy | MAR → sSPEC | 91.4 | −0.015 [−0.024–0.007] | 97.5 | 2.5 | Highest robustness; stable to window/SSA variation |

| Forecasting Method | Median Runtime Per SKU (s) | IQR (s) | % Boundary Hits | Within-Bounds Success Rate (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | 0.004 | [0.003, 0.005] | 0.0 | 100 | Single-parameter, closed form |

| SES | 0.006 | [0.005, 0.007] | 1.2 | 98.8 | Simple exponential smoothing |

| CRO | 0.007 | [0.006, 0.009] | 2.1 | 97.9 | Baseline intermittent model |

| SBA | 0.010 | [0.009, 0.013] | 3.4 | 96.6 | Two-parameter bias-corrected |

| TSB | 0.012 | [0.010, 0.014] | 3.8 | 96.2 | Probability-of-occurrence variant |

| SK | 0.009 | [0.008, 0.011] | 2.0 | 98.0 | Single-parameter non-parametric update |

| mSBA | 0.013 | [0.011, 0.016] | 4.3 | 95.7 | Updates interval during zero runs |

| mTSB | 0.015 | [0.013, 0.018] | 4.7 | 95.3 | Updates probability during zero runs |

| SK–SSA | 0.018 | [0.015, 0.021] | 2.5 | 97.5 | Adds SSA stabilization (low overhead) |

| Demand Class | Baseline | Method | Median ΔsSPEC | IQR | Q1 | Q3 | Whisker Low | Whisker High | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent | TSB | SK | −0.010 | 0.024 | −0.022 | +0.002 | −0.060 | +0.038 | −0.011 |

| SK–SSA | −0.020 | 0.022 | −0.031 | −0.009 | −0.060 | +0.024 | −0.020 | ||

| Lumpy | SBA | SK | −0.015 | 0.030 | −0.030 | 0.000 | −0.075 | +0.045 | −0.016 |

| SK–SSA | −0.030 | 0.028 | −0.044 | −0.016 | −0.080 | +0.026 | −0.029 | ||

| Erratic | TSB | SK | −0.010 | 0.020 | −0.020 | 0.000 | −0.050 | +0.030 | −0.011 |

| SK–SSA | −0.020 | 0.022 | −0.031 | −0.009 | −0.050 | +0.024 | −0.020 |

References

- Johnston, F.R.; Boylan, J.E.; Shale, E.A. An examination of the size of orders from customers, their characterisation and the implications for inventory control of slow moving items. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2003, 54, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louit, D.; Pascual, R.; Banjevic, D.; Jardine, A.K.S. Optimization models for critical spare parts inventories—A reliability approach. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2011, 62, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, J.E.; Syntetos, A.A. Spare parts management: A review of forecasting research and extensions. IMA J. Manag. Math. 2010, 21, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croston, J.D. Forecasting and stock control for intermittent demands. Oper. Res. Q. 1972, 23, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Boylan, J.E. On the bias of intermittent demand estimates. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2001, 71, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Boylan, J.E. The accuracy of intermittent demand estimates. Int. J. Forecast. 2005, 21, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunter, R.; Sani, B. On the bias of Croston’s forecasting method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 54, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunter, R.H.; Syntetos, A.A.; Babai, M.Z. Intermittent demand: Linking forecasting to inventory obsolescence. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 214, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestwich, S.D.; Tarim, S.A.; Rossi, R.; Hnich, B. Forecasting intermittent demand by hyperbolic-exponential smoothing. Int. J. Forecast. 2014, 30, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Boylan, J.E.; Chen, H.; Labib, A. OR in spare parts management: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 266, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinçe, Ç.; Turrini, L.; Meissner, J. Intermittent demand forecasting for spare parts: A critical review. Omega 2021, 105, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, A.; Saccani, N. Spare parts classification and demand forecasting for stock control: Investigating the gap between research and practice. Omega 2012, 40, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeijnders, W.; Teunter, R.; Van Jaarsveld, W. A two-step method for forecasting spare parts demand using information on component repairs. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 220, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, G.; Miceli, V.M. Demand Forecasting and Inventory Management for Spare Parts. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/121291 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Achetoui, Z.; Mabrouki, C.; Mousrij, A. A review of spare parts supply chain management. J. Sist. Manaj. Ind. 2019, 3, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Koehler, A.B. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. Int. J. Forecast. 2006, 22, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaves, A.H.C.; Kingsman, B.G. Forecasting for the ordering and stock-holding of spare parts. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2004, 55, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallström, P.; Segerstedt, A. Evaluation of forecasting error measurements and techniques for intermittent demand. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 128, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourentzes, N. On intermittent demand model optimisation and selection. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 156, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Spitzer, P.; Kühl, N. A new metric for lumpy and intermittent demand forecasts: Stock-keeping-oriented Prediction Error Costs. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Maui, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2020; pp. 974–983. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X.; Yu, Y.; Chen, A. A combined forecasting method for intermittent demand using automotive aftermarket data. Data Sci. Manag. 2022, 5, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.M. Stock control with sporadic and slow-moving demand. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1984, 35, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, F.R.; Boylan, J.E. Forecasting for items with intermittent demand. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1996, 47, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Boylan, J.E.; Croston, J.D. On the categorization of demand patterns. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2005, 56, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, A.V.; Hyndman, R.J. A note on the categorization of demand patterns. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2006, 57, 1256–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinecke, G.; Syntetos, A.A.; Wang, W. Forecasting-based SKU classification. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.P.; Xia, Y.; Xie, M. Intermittent demand forecasting with transformer neural networks. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 326, 767–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Ahmed, N.; Ali, S.M. Improving sporadic demand forecasting using a modified k-nearest neighbor framework. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 129, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Kang, Y.; Petropoulos, F.; Li, F. Feature-based intermittent demand forecast combinations: Accuracy and inventory implications. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 7557–7572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kang, Y.; Petropoulos, F. Combining probabilistic forecasts of intermittent demand. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 315, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, K.; Syntetos, A.A.; Boylan, J.E.; Petropoulos, F.; Assimakopoulos, V. An Aggregate–Disaggregate Intermittent Demand Approach (ADIDA) to forecasting: An empirical proposition and analysis. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2011, 62, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, F.; Kourentzes, N. Forecast combinations for intermittent demand. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2015, 66, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, C.; Lee, S.; Yu, L.; Ma, F. A modified Teunter–Syntetos–Babai method for intermittent demand forecasting. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2021, 6, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golyandina, N.; Nekrutkin, V.; Zhigljavsky, A. Analysis of Time Series Structure: SSA and Related Techniques; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schoellhamer, D. Singular spectrum analysis for time series with missing data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 3187–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, E.S. Exponential smoothing: The state of the art—Part II. Int. J. Forecast. 2006, 22, 637–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, L.; Meissner, J. Spare parts inventory management: New evidence from distribution fitting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Formula | Equation Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Croston | (1) | |

| SBA | is a smoothing constant for demand intervals, further refining the original forecast. | (2) |

| TSB | (3) | |

| mSBA | (4) | |

| mTSB | (5) |

| Method | Purpose | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Croston | Forecasts intermittent demand by separating non-zero demand sizes and inter-demand intervals. | Foundational method but tends to introduce positive bias. |

| SBA | Improves Croston’s method by correcting the bias in demand estimation. | Reduces overestimation bias present in Croston’s method. |

| TSB | Addresses obsolescence issues by incorporating demand occurrence probabilities. | Better accounts for periods with zero demand, especially for end-of-lifecycle products. |

| mSBA | Further improves SBA by incorporating updates during zero-demand periods. | Updates inter-demand intervals during zero-demand periods. |

| mTSB | Enhances TSB by refining updates during zero-demand periods. | Combines benefits of mSBA and TSB. |

| SK | Simplifies probability-of-occurrence estimation using a non-parametric ratio, combined with exponentially smoothed non-zero size. | Parameter-light, interpretable updates that track intermittence without an extra smoothing parameter for occurrence. |

| SK–SSA | Applies SSA to stabilize non-zero size updates prior to the SK probability–size combination, targeting highly lumpy series. | Improved robustness on volatile, lumpy demand by reducing size-estimate variance while retaining SK’s simplicity. |

| Error Metric | Formula | Key Citation | Equation Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Error | Standard | (16) | |

| Mean Absolute Error | Standard | (17) | |

| Mean Squared Rate | Kourentzes, 2014 [19] | (18) | |

| Mean Absolute Rate | Kourentzes, 2014 [19] | (19) | |

| Period In Stock | Wallstrom and Segerstedt, 2010 [18] | (20) | |

| Absolute Period In Stock | Wallstrom and Segerstedt, 2010 [18] | (21) | |

| Stock-Keeping-Oriented Prediction Error Costs | Martin et al., 2020 [20] | ||

| (22) | |||

| The constants define the opportunity and stock-keeping costs, respectively | |||

| Absolute Scaled Error | Hyndman and Koehler, 2006 [16] | (23) | |

| Mean Absolute Scaled Error | Hyndman and Koehler, 2006 [16] | (24) | |

| Scaled Absolute Period In Stock | Kourentzes, 2014 [19] | (25) | |

| Scaled Stock-Keeping-Oriented Prediction Error Costs | This Paper | ||

| (26) | |||

| Study | Method | Application | Research Gap and Open Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Croston, 1972 [4] | Croston’s Method | Intermittent slow-moving items | Foundational approach; known positive bias and no explicit handling of zero-demand stretches. |

| Syntetos and Boylan, 2001 [5] | Bias analysis/early correction | Intermittent-demand items across sectors | Showed CRO’s systematic positive bias for intermittent series and derived an adjustment to reduce that bias (foundation of SBA). |

| Johnston et al., 2003 [1] | Traditional spare-parts forecasting | General spare parts demand | Highlighted challenges of intermittent demand in slow-moving spare parts; did not focus on optimization strategies tailored to distinct demand profiles. |

| Syntetos et al., 2005 [6] | SBA | Intermittent/lumpy demand | Applied a closed-form bias correction to CRO (multiplicative factor on size/interval ratio) to reduce overestimation under intermittence. |

| Syntetos et al., 2005 [6] | Demand categorization | Intermittent demand | Provided a practical taxonomy; mapping categories to broader method sets and policy impacts invited further work. |

| Wallström and Segerstedt, 2010 [18] | PIS/APIS metrics | Inventory-linked errors | Connected error to stock behavior; further handling of long zero runs and high lumpiness encouraged. |

| Boylan and Syntetos, 2010 [3] | Review | Spare parts management | Called for stronger forecasting–inventory integration, comparative benchmarks on real industrial datasets, better treatment of obsolescence and non-stationarity, and practical guidance on method selection and parameterization for short, sparse histories. |

| Louit et al., 2011 [2] | Horizontal stock control | Spare parts inventory | Underscored the value of classification; opened space for methods that link categorization to forecasting and policy. |

| Teunter et al., 2011 [8] | TSB | Obsolescence, slow-moving items | Reduced bias relative to Croston; scope to extend toward more complex patterns. |

| Bacchetti and Saccani, 2012 [12] | Reviews | Manufacturing spare parts | Synthesized practice–research gap; encouraged empirical testing of alternative models and metrics. |

| Romeijnders et al., 2012 [13] | Croston-based models | Intermittent spare-parts demand | Discussed bias and pattern sensitivity; further extensions to declining/obsolescent demand remained to be explored broadly. |

| Prestwich et al., 2014 [9] | HES | Slow-moving and obsolete parts | Addressed decay; applications beyond specific contexts suggested. |

| Kourentzes, 2014 [19] | MSR/MAR, sAPIS, global cost optimization | Intermittent demand accuracy | Advanced rate-based/objective-first tuning; integration with inventory policies and highly lumpy cases remained an open direction. |

| Hu et al., 2018 [10] | Review | Spare-parts inventory | Comprehensive overview; called for new empirical models for highly volatile demand. |

| Turrini and Meissner, 2019 [37] | NB/Bernoulli distributions | Spare-parts demand fitting | Supported NB and Bernoulli for sizes/arrivals; combining them operationally for LTD and policy tuning offered scope. |

| Martin et al., 2020 [20] | SPEC metric | Lumpy demand in inventory systems | Reframed evaluation in cost terms; scaling/normalization for cross-SKU comparability was a natural next step. |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [27] | Transformer-based ML | Sparse/irregular demand | Demonstrated potential; real-world deployment can face data and computational constraints. |

| Hasan et al., 2024 [28] | Modified k-NN | Intermittent demand | Showed ML gains; highlighted training-data and implementation considerations. |

| Wang et al., 2024 [30] | Probabilistic combinations | Dynamic intermittent demand | Advanced combinations; ERP integration and computational efficiency remain important considerations. |

| This study | MCOST with SK/SK–SSA; sSPEC; NBB LTD within (R,Q) | Automotive spare parts (intermittent/lumpy) | Contributes a per-SKU, objective-first selection aligned with inventory costs (sSPEC), introduces a non-parametric occurrence estimator (SK) and an SSA-stabilized variant (SK–SSA), and links forecasts to policy via NBB LTD, with CPU-only implementation suitable for ERP environments. |

| 2050 SKUs | Demand Intervals | Demand Size | Demand Per Period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | St. Deviation | Mean | St. Deviation | Mean | St. Deviation | |

| Min | 1.1 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| 25%ile | 1.6 | 0.9 | 16.6 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 3.0 |

| Mean | 2.2 | 1.6 | 34.9 | 16.0 | 18.9 | 18.1 |

| 75%ile | 2.8 | 2.1 | 49.7 | 22.5 | 25.8 | 22.2 |

| Max | 6.4 | 7.0 | 165.5 | 146.5 | 101.2 | 227.9 |

| Forecast Method | Parameters to Optimize | First Parameter Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Second Parameter Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | 1 | 10 | 30 | - | - |

| SES | 1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | - | - |

| CRO | 1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | - | - |

| SBA | 2 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| TSB | 2 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.4 |

| SK | 1 | 0.05 | 0.4 | - | - |

| mSBA | 2 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| mTSB | 2 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.4 |

| SK–SSA | 2 | 0.05 | 0.4 | 1 | 3 |

| ALL SKUS AV. SSPEC | SMA | SES | CRO | SBA | TSB | SK | MSBA | MTSB | SK–SSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MSE | 0.797 | 0.767 | 0.779 | 0.831 | 0.779 | 0.799 | 0.928 | 0.803 | 0.889 |

| 2. MAE | 0.794 | 0.757 | 0.783 | 0.870 | 0.793 | 0.828 | 0.961 | 0.838 | 1.084 |

| 3. PIS | 0.795 | 0.786 | 0.777 | 0.818 | 0.730 | 0.794 | 0.926 | 0.811 | 0.821 |

| 4. MSR | 0.797 | 0.767 | 0.780 | 0.813 | 0.776 | 0.796 | 0.928 | 0.801 | 0.802 |

| 5. MAR | 0.797 | 0.769 | 0.781 | 0.808 | 0.780 | 0.797 | 0.927 | 0.802 | 0.799 |

| 6. SPEC | 0.797 | 0.792 | 0.776 | 0.817 | 0.729 | 0.795 | 0.926 | 0.811 | 0.804 |

| MCOST | 0.797 | 0.767 | 0.750 | 0.742 | 0.672 | 0.748 | 0.869 | 0.732 | 0.711 |

| %OPTIMIZED | |||||||||

| 1. MSE | 64.15% | 99.71% | 96.49% | 86.24% | 65.80% | 72.73% | 81.95% | 66.49% | 41.32% |

| 2. MAE | 74.93% | 86.15% | 90.34% | 86.29% | 84.44% | 86.10% | 83.61% | 83.95% | 11.12% |

| 3. PIS | 84.77% | 2.23% | 83.62% | 74.00% | 24.92% | 34.29% | 43.79% | 30.72% | 42.13% |

| 4. MSR | 6.12% | 100.00% | 98.47% | 94.58% | 62.78% | 96.75% | 95.73% | 63.61% | 96.75% |

| 5. MAR | 5.61% | 100.00% | 99.87% | 97.07% | 72.21% | 98.79% | 95.60% | 73.61% | 98.79% |

| 6. SPEC | 93.44% | 0.00% | 81.58% | 52.39% | 15.11% | 33.78% | 37.79% | 21.67% | 36.65% |

| MCOST | 97.45% | 100.00% | 98.47% | 98.77% | 91.46% | 99.64% | 98.85% | 96.65% | 99.69% |

| ADJUSTED SSPEC OF OPTIMIZED | |||||||||

| 1. MSE | 0.980 | 0.769 | 0.799 | 0.901 | 0.883 | 0.924 | 1.047 | 0.901 | 1.104 |

| 2. MAE | 0.943 | 0.848 | 0.844 | 0.967 | 0.893 | 0.923 | 1.091 | 0.944 | 1.186 |

| 3. PIS | 0.896 | 0.794 | 0.877 | 0.959 | 0.851 | 0.952 | 1.154 | 0.947 | 1.021 |

| 4. MSR | 0.838 | 0.767 | 0.786 | 0.849 | 0.893 | 0.769 | 0.954 | 0.907 | 0.777 |

| 5. MAR | 0.833 | 0.769 | 0.782 | 0.825 | 0.878 | 0.779 | 0.953 | 0.896 | 0.781 |

| 6. SPEC | 0.843 | 0.792 | 0.890 | 1.020 | 0.822 | 0.963 | 1.138 | 0.932 | 0.989 |

| MCOST | 0.814 | 0.767 | 0.759 | 0.737 | 0.696 | 0.734 | 0.855 | 0.709 | 0.711 |

| RANK | |||||||||

| 1 | MAR | MSR | MAR | MAR | SPEC | MSR | MAR | MAR | MSR |

| 2 | MSR | MAR | MSR | MSR | PIS | MAR | MSR | MSE | MAR |

| 3 | SPEC | MSE | MSE | MSE | MAR | MAE | MSE | MSR | SPEC |

| 4 | PIS | SPEC | MAE | PIS | MSE | MSE | MAE | SPEC | PIS |

| 5 | MAE | PIS | PIS | MAE | MSR | PIS | SPEC | MAE | MSE |

| 6 | MSE | MAE | SPEC | SPEC | MAE | SPEC | PIS | PIS | MAE |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 13 | 13 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 4 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 |

| 14 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 |

| 5 | 10 | 4 | 13 | 0 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 |

| 2 | 15 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 |

| 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 72 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 |

| 6 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6 |

| 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 91 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 101 |

| 7 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| 102 | 103 | 104 | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Forecast Method | Number of Parameters Optimized | First Parameter Name/Best Value | Second Parameter Name/Best Value | Parameter Meaning/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | 1 | Window|11 | - | MA window length |

| SES | 1 | α (level)|0.15 | - | Level smoothing |

| CRO | 1 | α|0.25 | - | Croston: smooths size and interval |

| SBA | 2 | α (size)|0.30 | β (interval)|0.40 | Bias-corrected Croston |

| TSB | 2 | α (size)|0.30 | β (interval)|0.30 | Size and probability of occurrence |

| SK | 2 | α (size)|0.40 | - | Size smoothing; occurrence is non-parametric |

| mSBA | 2 | α (size)|0.05 | β (interval)|0.40 | Interval updates during zeros |

| mTSB | 2 | α (size)|0.40 | β (interval)|0.40 | Occurrence updates during zeros |

| SK–SSA | 2 | α (size)|0.40 | k|1 | SSA-stabilized size and reconstructed components |

| Metric | SMA (11) | SES (0.15) | CRO (0.25) | SBA (0.30, 0.40) | TSB (0.30, 0.30) | SK (0.40) | mSBA (0.05, 0.4) | mTSB (0.40, 0.40) | SK–SSA (0.40, 1, 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MASE | 0.556 | 0.544 | 0.626 | 0.518 | 0.434 | 0.508 | 0.461 | 0.568 | 0.400 |

| sAPIS | 3.194 | 1.466 | 1.886 | 0.510 | 0.478 | 0.504 | 0.467 | 0.545 | 0.460 |

| sSPEC | 0.329 | 0.181 | 0.191 | 0.169 | 0.166 | 0.167 | 0.167 | 0.186 | 0.163 |

| Error | MASE | sSPEC | sAPIS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t + 1 | t + 3 | t + 5 | t + 1 | t + 3 | t + 5 | t + 1 | t + 3 | t + 5 | |

| Scenario 1: SES, CRO, SBA | |||||||||

| MSE | 0.951 | 0.940 | 0.929 | 0.616 | 0.850 | 1.158 | 1.187 | 2.661 | 4.448 |

| MAE | 0.966 | 0.952 | 0.943 | 0.644 | 0.906 | 1.284 | 1.208 | 2.730 | 4.611 |

| MSR | 0.910 | 0.900 | 0.892 | 0.589 | 0.814 | 1.114 | 1.138 | 2.553 | 4.276 |

| MAR | 0.896 | 0.887 | 0.878 | 0.579 | 0.802 | 1.092 | 1.122 | 2.519 | 4.203 |

| PIS | 1.022 | 1.010 | 0.998 | 0.659 | 0.897 | 1.198 | 1.273 | 2.840 | 4.641 |

| SPEC | 1.055 | 1.048 | 1.034 | 0.682 | 0.950 | 1.254 | 1.320 | 2.966 | 4.808 |

| MCOST | 0.851 | 0.875 | 0.873 | 0.569 | 0.742 | 1.068 | 1.070 | 2.345 | 3.784 |

| Scenario 2: SES, CRO, SBA | |||||||||

| MSE | 0.951 | 0.940 | 0.929 | 0.616 | 0.850 | 1.158 | 1.187 | 2.661 | 4.448 |

| MAE | 0.966 | 0.952 | 0.943 | 0.644 | 0.906 | 1.284 | 1.208 | 2.730 | 4.611 |

| MSR | 0.910 | 0.900 | 0.892 | 0.589 | 0.814 | 1.114 | 1.138 | 2.553 | 4.276 |

| MAR | 0.896 | 0.887 | 0.878 | 0.579 | 0.802 | 1.092 | 1.122 | 2.519 | 4.203 |

| PIS | 1.022 | 1.010 | 0.998 | 0.659 | 0.897 | 1.198 | 1.273 | 2.840 | 4.641 |

| SPEC | 1.055 | 1.048 | 1.034 | 0.682 | 0.950 | 1.254 | 1.320 | 2.966 | 4.808 |

| MCOST | 0.851 | 0.875 | 0.873 | 0.569 | 0.742 | 1.068 | 1.070 | 2.345 | 3.784 |

| Scenario 3: SES, CRO, SBA, TSB, SK | |||||||||

| MSE | 1.018 | 1.003 | 0.988 | 0.649 | 0.880 | 1.200 | 1.249 | 2.769 | 4.606 |

| MAE | 0.971 | 0.961 | 0.952 | 0.649 | 0.915 | 1.281 | 1.216 | 2.743 | 4.590 |

| MSR | 0.957 | 0.951 | 0.940 | 0.604 | 0.829 | 1.144 | 1.172 | 2.627 | 4.376 |

| MAR | 0.940 | 0.934 | 0.924 | 0.596 | 0.824 | 1.122 | 1.157 | 2.599 | 4.308 |

| PIS | 1.051 | 1.049 | 1.036 | 0.667 | 0.912 | 1.196 | 1.297 | 2.881 | 4.619 |

| SPEC | 1.058 | 1.053 | 1.041 | 0.682 | 0.934 | 1.209 | 1.319 | 2.918 | 4.631 |

| MCOST | 0.833 | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.559 | 0.699 | 1.055 | 1.042 | 2.155 | 3.325 |

| Scenario 4: SES, CRO, SBA, TSB, SK, mSBA, mTSB, SK–SSA | |||||||||

| MSE | 1.051 | 1.035 | 1.022 | 0.696 | 0.969 | 1.342 | 1.309 | 2.939 | 4.908 |

| MAE | 0.950 | 0.937 | 0.930 | 0.673 | 1.017 | 1.530 | 1.186 | 2.802 | 4.789 |

| MSR | 0.940 | 0.935 | 0.925 | 0.594 | 0.827 | 1.157 | 1.145 | 2.587 | 4.329 |

| MAR | 0.930 | 0.923 | 0.913 | 0.593 | 0.828 | 1.140 | 1.141 | 2.575 | 4.283 |

| PIS | 1.067 | 1.060 | 1.049 | 0.690 | 0.974 | 1.313 | 1.311 | 2.947 | 4.809 |

| SPEC | 1.059 | 1.051 | 1.042 | 0.691 | 0.964 | 1.293 | 1.314 | 2.944 | 4.757 |

| MCOST | 0.761 | 0.803 | 0.811 | 0.539 | 0.686 | 1.048 | 0.949 | 2.007 | 3.169 |

| Pool of Models | MASE | sSPEC | sAPIS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t + 1 | t + 3 | t + 5 | t + 1 | t + 3 | t + 5 | t + 1 | t + 3 | t + 5 | |

| CRO (single model) | 0.848 | 0.860 | 0.856 | 0.542 | 0.743 | 0.901 | 1.065 | 2.355 | 3.879 |

| SBA (single model) | 0.782 | 0.816 | 0.817 | 0.528 | 0.728 | 0.885 | 0.978 | 2.152 | 3.524 |

| CRO, SBA | 0.758 | 0.805 | 0.811 | 0.507 | 0.686 | 0.839 | 0.950 | 2.057 | 3.318 |

| SES, CRO, SBA | 0.741 | 0.796 | 0.803 | 0.497 | 0.667 | 0.805 | 0.927 | 1.987 | 3.171 |

| TSB (single model) | 0.805 | 0.832 | 0.841 | 0.516 | 0.712 | 0.863 | 0.965 | 2.175 | 3.533 |

| CRO, SBA, TSB | 0.703 | 0.777 | 0.789 | 0.477 | 0.639 | 0.758 | 0.879 | 1.875 | 2.927 |

| SES, CRO, SBA, TSB | 0.699 | 0.776 | 0.787 | 0.474 | 0.631 | 0.747 | 0.875 | 1.856 | 2.890 |

| mSBA (single model) | 0.779 | 0.800 | 0.807 | 0.569 | 0.841 | 1.106 | 0.968 | 2.206 | 3.724 |

| CRO, mSBA | 0.693 | 0.765 | 0.777 | 0.491 | 0.673 | 0.823 | 0.864 | 1.848 | 2.943 |

| CRO, mSBA, mTSB | 0.655 | 0.753 | 0.768 | 0.474 | 0.637 | 0.781 | 0.835 | 1.783 | 2.825 |

| SES, CRO, mSBA, mTSB | 0.651 | 0.747 | 0.763 | 0.468 | 0.635 | 0.769 | 0.827 | 1.758 | 2.766 |

| mTSB (single model) | 0.801 | 0.827 | 0.834 | 0.539 | 0.757 | 0.938 | 1.009 | 2.166 | 3.691 |

| SK (single model) | 0.793 | 0.826 | 0.830 | 0.521 | 0.722 | 0.859 | 0.951 | 2.139 | 3.528 |

| TSB, SK | 0.725 | 0.791 | 0.799 | 0.489 | 0.654 | 0.775 | 0.908 | 1.937 | 3.026 |

| SES, CRO, SBA, TSB, SK | 0.635 | 0.782 | 0.783 | 0.460 | 0.612 | 0.719 | 0.845 | 1.785 | 2.756 |

| SMA, SES, CRO, SBA, TSB, SK | 0.630 | 0.740 | 0.834 | 0.456 | 0.606 | 0.711 | 0.838 | 1.767 | 2.721 |

| mSBA, mTSB, SK–SSA | 0.589 | 0.710 | 0.732 | 0.433 | 0.628 | 0.746 | 0.752 | 1.627 | 2.557 |

| CRO, SK, SK–SSA | 0.611 | 0.722 | 0.740 | 0.453 | 0.623 | 0.756 | 0.760 | 1.644 | 2.585 |

| SK, mSBA, mTSB | 0.649 | 0.745 | 0.761 | 0.499 | 0.647 | 0.786 | 0.832 | 1.781 | 2.809 |

| SMA, SES, CRO, SBA, TSB, SK, mSBA, mTSB, SK–SSA | 0.539 | 0.689 | 0.715 | 0.395 | 0.529 | 0.612 | 0.702 | 1.481 | 2.259 |

| 176 Lumpy SKUs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demand Intervals | Demand Size | Demand per Period | ||||

| Mean | St. Dev | Mean | St. Dev | Mean | St. Dev | |

| Min | 1.3 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| 25%ile | 1.5 | 0.9 | 7.3 | 5.9 | 4.0 | 4.8 |

| Mean | 1.7 | 1.1 | 38.9 | 33.2 | 24.3 | 36.2 |

| 75%ile | 1.8 | 1.2 | 63.5 | 49.6 | 37.6 | 49.1 |

| Max | 3.2 | 3.1 | 165.5 | 146.5 | 101.2 | 227.9 |

| 1572 Intermittent SKUs | ||||||

| Mean | St. Dev | Mean | St. Dev | Mean | St. Dev | |

| Min | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| 25%ile | 1.8 | 1.2 | 17.2 | 4.9 | 6.8 | 2.4 |

| Mean | 2.5 | 1.8 | 33.5 | 12.6 | 15.4 | 9.6 |

| 75%ile | 3.0 | 2.3 | 44.5 | 17.2 | 18.7 | 11.7 |

| Max | 6.4 | 7.0 | 99.3 | 50.4 | 69.9 | 72.7 |

| 74 Erratic SKUs | ||||||

| Mean | St. Dev | Mean | St. Dev | Mean | St. Dev | |

| Min | 1.1 | 0.3 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 6.4 |

| 25%ile | 1.1 | 0.4 | 14.2 | 11.4 | 12.0 | 24.4 |

| Mean | 1.2 | 0.5 | 35.6 | 27.0 | 30.5 | 64.3 |

| 75%ile | 1.2 | 0.5 | 52.8 | 41.2 | 44.1 | 90.7 |

| Max | 1.3 | 0.7 | 80.4 | 58.2 | 69.6 | 195.3 |

| Intermittent SKUs sSPEC | SMA | SES | CRO | SBA | TSB | SK | mSBA | mTSB | SK–SSA | Optimal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 0.615 | 0.618 | 0.586 | 0.573 | 0.581 | 0.577 | 0.618 | 0.583 | 0.526 | 0.448 |

| Median | 0.286 | 0.297 | 0.277 | 0.245 | 0.252 | 0.243 | 0.199 | 0.248 | 0.141 | 0.130 |

| 75th Percentile | 0.768 | 0.775 | 0.729 | 0.761 | 0.700 | 0.773 | 0.909 | 0.739 | 0.780 | 0.572 |

| 25th Percentile | 0.219 | 0.207 | 0.219 | 0.167 | 0.175 | 0.203 | 0.135 | 0.175 | 0.081 | 0.070 |

| Maximum | 2.089 | 2.171 | 2.044 | 2.115 | 2.120 | 2.037 | 2.267 | 2.161 | 2.067 | 2.007 |

| Minimum | 0.093 | 0.092 | 0.086 | 0.065 | 0.034 | 0.078 | 0.060 | 0.047 | 0.036 | 0.023 |

| Lumpy SKUs sSPEC | SMA | SES | CRO | SBA | TSB | SK | mSBA | mTSB | SK–SSA | Optimal |

| Average | 0.525 | 0.525 | 0.489 | 0.463 | 0.483 | 0.476 | 0.485 | 0.480 | 0.434 | 0.392 |

| Median | 0.229 | 0.240 | 0.223 | 0.190 | 0.220 | 0.208 | 0.162 | 0.200 | 0.127 | 0.112 |

| 75th Percentile | 0.329 | 0.383 | 0.324 | 0.287 | 0.314 | 0.303 | 0.378 | 0.300 | 0.271 | 0.204 |

| 25th Percentile | 0.185 | 0.157 | 0.149 | 0.103 | 0.128 | 0.131 | 0.098 | 0.124 | 0.070 | 0.039 |

| Maximum | 2.173 | 2.147 | 2.081 | 2.189 | 2.138 | 2.049 | 2.250 | 2.066 | 2.074 | 2.062 |

| Minimum | 0.027 | 0.042 | 0.033 | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.025 | 0.010 | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.009 |

| Erratic SKUs sSPEC | SMA | SES | CRO | SBA | TSB | SK | mSBA | mTSB | SK–SSA | Optimal |

| Average | 0.470 | 0.475 | 0.441 | 0.424 | 0.445 | 0.416 | 0.468 | 0.434 | 0.411 | 0.370 |

| Median | 0.231 | 0.210 | 0.193 | 0.174 | 0.204 | 0.211 | 0.194 | 0.189 | 0.169 | 0.147 |

| 75th Percentile | 0.634 | 0.695 | 0.613 | 0.643 | 0.641 | 0.539 | 0.746 | 0.592 | 0.625 | 0.483 |

| 25th Percentile | 0.096 | 0.107 | 0.092 | 0.056 | 0.081 | 0.069 | 0.051 | 0.067 | 0.049 | 0.022 |

| Maximum | 1.593 | 1.690 | 1.701 | 1.692 | 1.677 | 1.656 | 1.826 | 1.689 | 1.676 | 1.537 |

| Minimum | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.014 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.001 |

| Model | Service Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80% | 85% | 90% | 95% | 97% | 99% | |

| SMA | 6.1 (10,980) | 8.7 (7670) | 12.4 (4546) | 18.6 (1851) | 23.2 (925) | 32.9 (192) |

| SES | 6.9 (9730) | 9.5 (6811) | 13.3 (4001) | 19.6 (1644) | 24.2 (834) | 34.0 (185) |

| CRO | 6.8 (9679) | 9.5 (6592) | 13.2 (3917) | 19.4 (1628) | 23.9 (837) | 33.8 (190) |

| SBA | 8.6 (8486) | 11.4 (5823) | 15.5 (3381) | 22.2 (1335) | 27.2 (667) | 37.8 (148) |

| TSB | 7.2 (9887) | 10.0 (6803) | 13.8 (4085) | 20.2 (1674) | 24.9 (870) | 35.1 (193) |

| SK | 7.1 (9052) | 9.76 (6232) | 13.5 (3656) | 19.8 (1478) | 24.5 (728) | 34.3 (152) |

| mSBA | 9.6 (5423) | 12.6 (3719) | 16.8 (2241) | 24.1 (922) | 29.3 (501) | 40.6 (138) |

| mTSB | 6.9 (6453) | 9.6 (4514) | 13.4 (2748) | 19.7 (1204) | 24.3 (679) | 34.2 (189) |

| SK–SSA | 9.3 (5381) | 12.2 (3758) | 16.4 (2267) | 23.4 (1005) | 28.6 (547) | 39.6 (150) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sfiris, D.S.; Koulouriotis, D.E. A New Approach to Forecast Intermittent Demand and Stock-Keeping-Unit Level Optimization for Spare Parts Management. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12030. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212030

Sfiris DS, Koulouriotis DE. A New Approach to Forecast Intermittent Demand and Stock-Keeping-Unit Level Optimization for Spare Parts Management. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12030. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212030

Chicago/Turabian StyleSfiris, Dimitrios S., and Dimitrios E. Koulouriotis. 2025. "A New Approach to Forecast Intermittent Demand and Stock-Keeping-Unit Level Optimization for Spare Parts Management" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12030. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212030

APA StyleSfiris, D. S., & Koulouriotis, D. E. (2025). A New Approach to Forecast Intermittent Demand and Stock-Keeping-Unit Level Optimization for Spare Parts Management. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12030. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212030