Effects of a History of Adductor-Related Groin Pain on Kicking Biomechanics and HAGOS Subscales in Male Soccer Players: A Comprehensive Analysis Using 1D-SPM

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

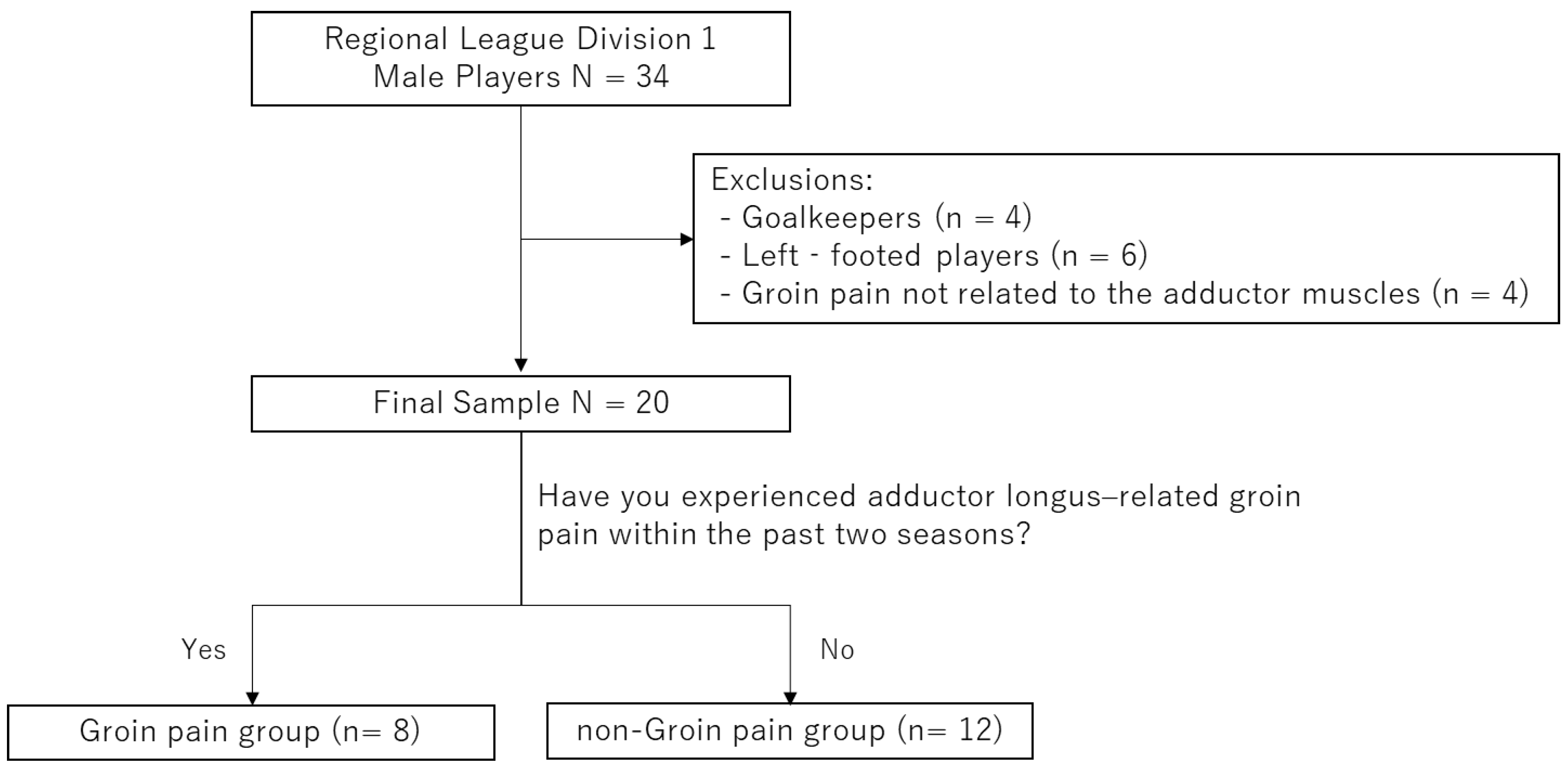

2.1. Participants

2.2. Subjective Assessment Using HAGOS

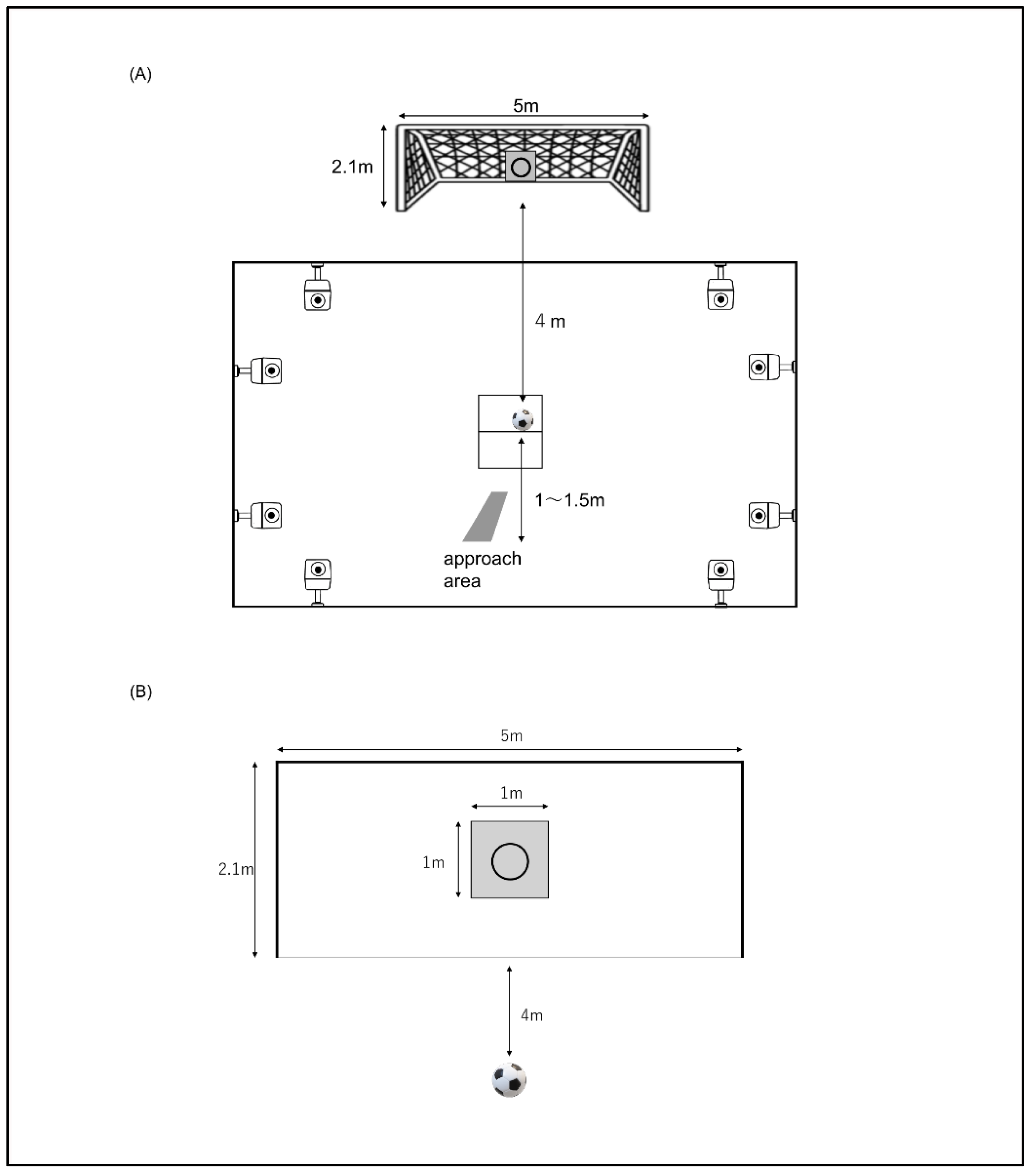

2.3. Experimental Protocol

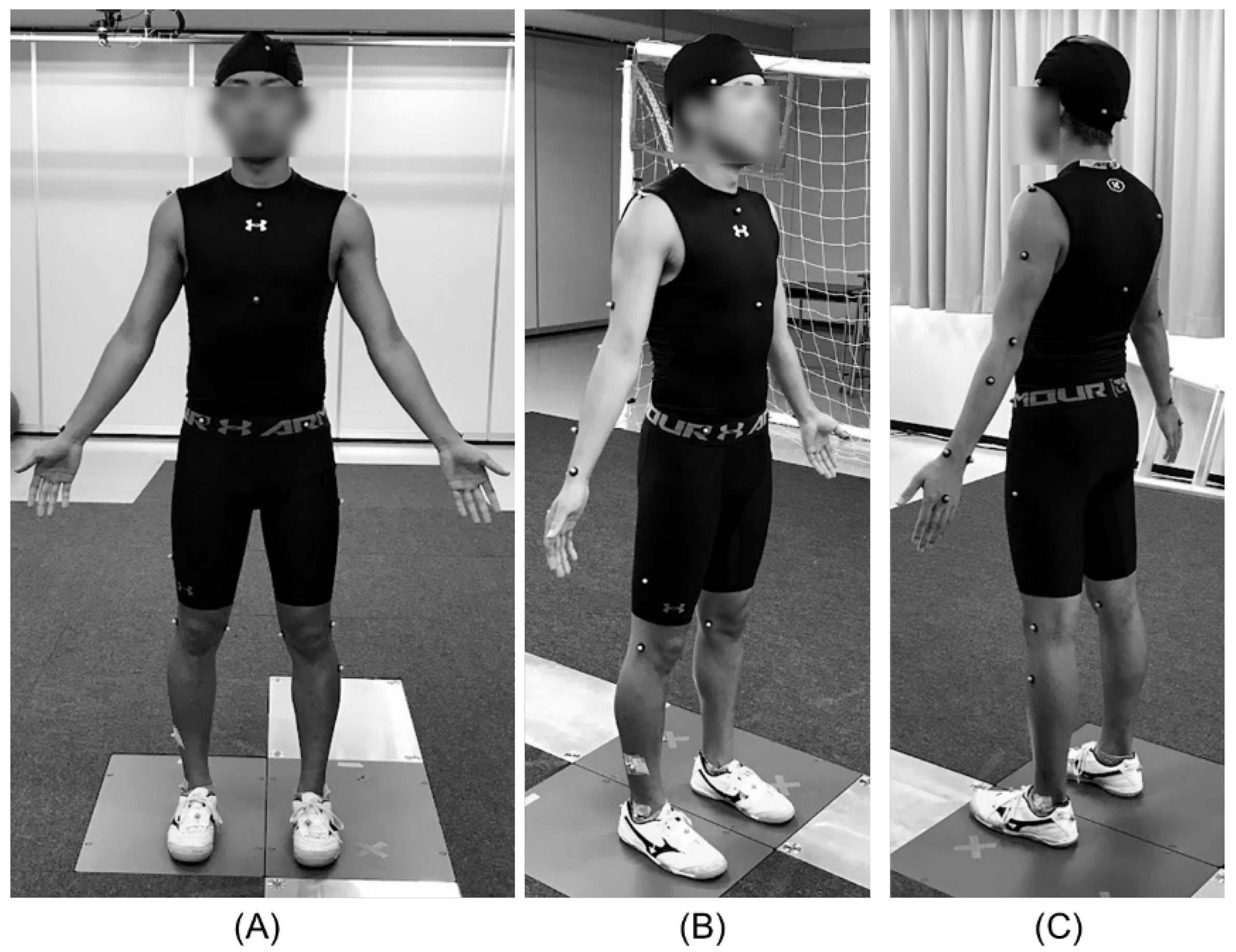

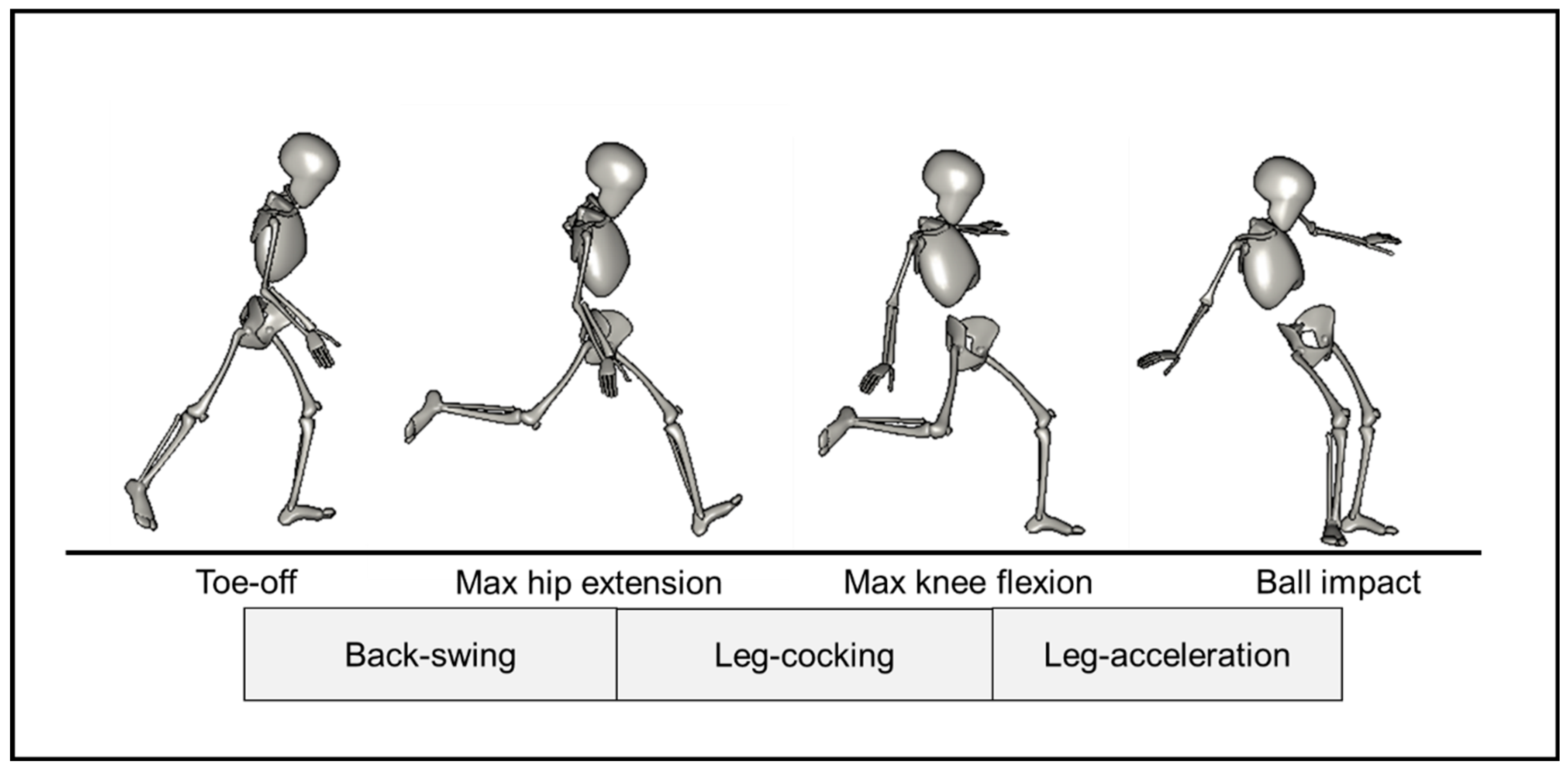

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Sample Size Estimation and Justification

2.5.2. Comparative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics (Table 1)

3.2. Comparison of HAGOSs

3.3. Kinematic and Kinetic Analysis

3.3.1. Overview of 1D-SPM Findings

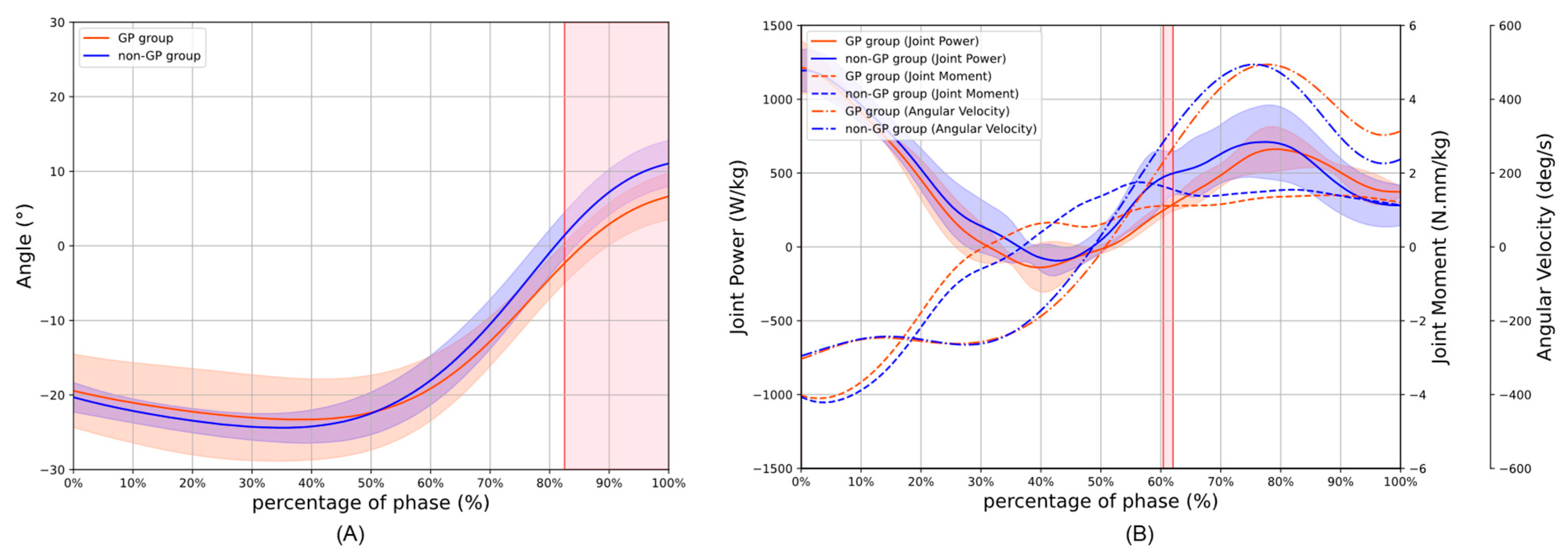

3.3.2. Between-Group Differences in the Inside Kick (Table 3)

3.3.3. Between-Group Differences in the Instep Kick (Table 4)

4. Discussion

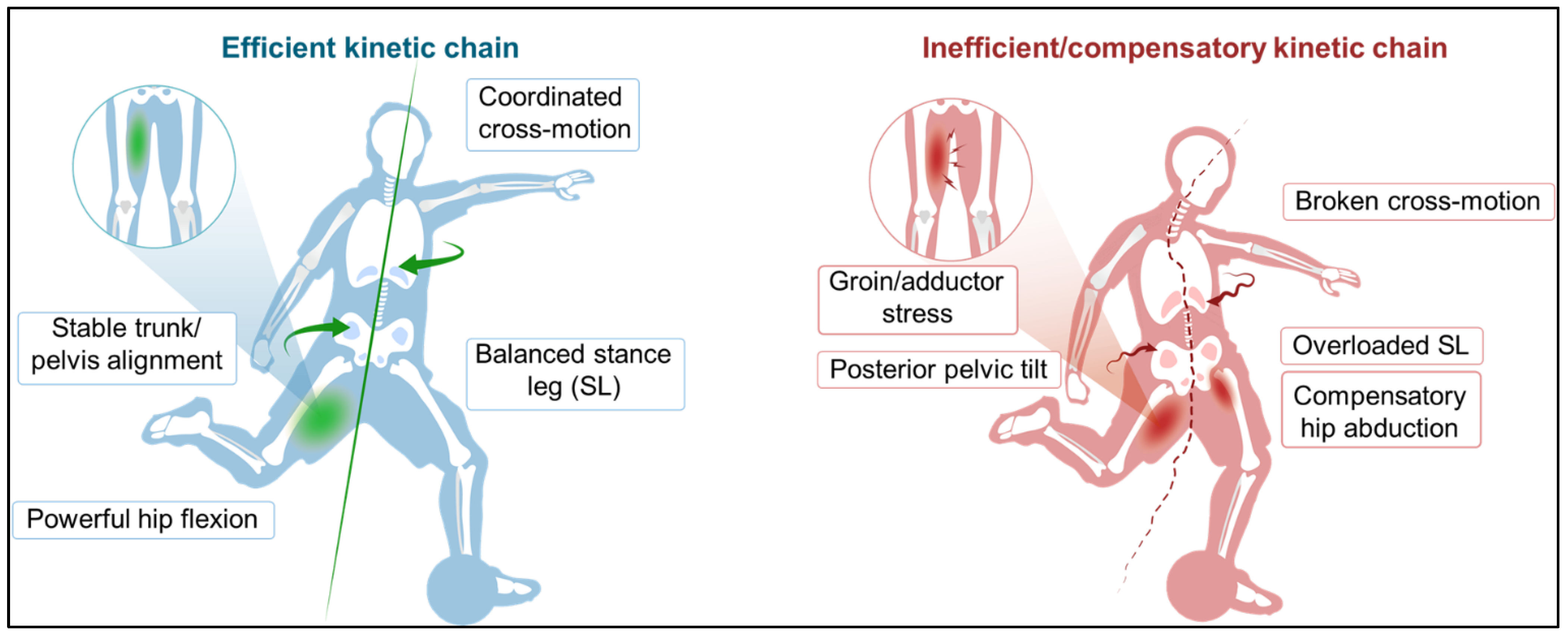

4.1. Inside Kick

4.2. Instep Kick

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGP | Adductor-related Groin Pain |

| COM | Center of Mass |

| COP | Center of Pressure |

| GP | Groin Pain |

| HAGOS | Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score |

| KL | Kicking Leg |

| SL | Stance Leg |

| PRO | Patient-Reported Outcome |

| QOL | Quality of Life |

| SPM | Statistical Parametric Mapping |

| 1D-SPM | One-Dimensional Statistical Parametric Mapping |

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| PA | Participation in Physical Activity |

| GRF | Ground Reaction Force |

References

- FIFA. Professional Football Report 2019; FIFA: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stølen, T.; Chamari, K.; Castagna, C.; Wisløff, U. Physiology of soccer: An update. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 501–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, J.; Hägglund, M.; Waldén, M. Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: The UEFA injury study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, A.; Brukner, P.; Delahunt, E.; Ekstrand, J.; Griffin, D.; Khan, K.M.; Lovell, G.; Meyers, W.C.; Muschaweck, U.; Orchard, J.; et al. Doha agreement meeting on terminology and definitions in groin pain in athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renström, P.; Peterson, L. Groin injuries in athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 1980, 14, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölmich, P. Long-standing groin pain in sportspeople falls into three primary patterns, a “clinical entity” approach: A prospective study of 207 patients. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 247–252; discussion 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, I.; Engelaar, L.; Gouttebarge, V.; Barendrecht, M.; Van den Heuvel, S.; Kerkhoffs, G.; Langhout, R.; Stubbe, J.; Weir, A.; Stubbe, J.; et al. Is lower hip range of motion a risk factor for groin pain in athletes? A systematic review with clinical applications. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 1611–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.F.; Nicholas, S.J.; Campbell, R.J.; McHugh, M.P. The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2001, 29, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J.L.; Small, C.; Maffey, L.; Emery, C.A. Risk factors for groin injury in sport: An updated systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engebretsen, A.H.; Myklebust, G.; Holme, I.; Engebretsen, L.; Bahr, R. Intrinsic risk factors for groin injuries among male soccer players: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010, 38, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brophy, R.H.; Backus, S.I.; Pansy, B.S.; Lyman, S.; Williams, R.J. Lower extremity muscle activation and alignment during the soccer instep and side-foot kicks. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2007, 37, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, T.; Funken, J.; Müller, R.; Mortensen, K.R.L.; Lysdal, F.G.; Braun, M.; Krahl, H.; Potthast, W.; Potthast, W. Does inside passing contribute to the high incidence of groin injuries in soccer? A biomechanical analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, T.; Tryba, J.; Potthast, W. Muscle activity of cutting manoeuvres and soccer inside passing suggests an increased groin injury risk during these movements. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunome, H.; Asai, T.; Ikegami, Y.; Sakurai, S. Three-dimensional kinetic analysis of side-foot and instep soccer kicks. Med. Sci. Sports Exer. 2002, 34, 2028–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunome, H.; Ikegami, Y.; Kozakai, R.; Apriantono, T.; Sano, S. Segmental dynamics of soccer instep kicking with the preferred and non-preferred leg. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnock, B.L.; Lewis, C.; Garrett, W.; Queen, R. Adductor Longus Mechanics During the Maximal Effort Soccer Kick. Sports Biomech. 2009, 8, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisaki, K.; Akasaka, K.; Otsudo, T.; Hattori, H.; Hasebe, Y.; Hall, T. Risk Factors for Groin Pain in Male High School Soccer Players Undergoing an Injury Prevention Program: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Trauma Care 2022, 2, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C.; Robinson, M.A.; Vanrenterghem, J. Vector field statistical analysis of kinematic and force trajectories. J. Biomech. 2013, 46, 2394–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes-Oliver, C.; Harrison, K.; Williams, D.; Queen, R. Statistical Parametric Mapping as a Measure of Differences Between Limbs: Applications to Clinical Populations. J. Appl. Biomech. 2019, 35, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sole, G.; Pataky, T.; Tengman, E.; Häger, C. Analysis of Three-Dimensional Knee Kinematics During Stair Descent Two Decades Post-ACL Rupture—Data Revisited Using Statistical Parametric Mapping. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2016, 32, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bleecker, C.; Vermeulen, S.; De Blaiser, C.; Willems, T.; de Ridder, R.; Roosen, P. Relationship Between Jump-Landing Kinematics and Lower Extremity Overuse Injuries in Physically Active Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1515–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorborg, K.; Hölmich, P.; Christensen, R.; Petersen, J.; Roos, E.M. The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS): Development and validation according to the COSMIN checklist. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörge, H.C.; Anderson, T.B.; Sørensen, H.; Simonsen, E.B. Biomechanical differences in soccer kicking with the preferred and the non-preferred leg. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zago, M.; Motta, A.F.; Mapelli, A.; Annoni, I.; Galvani, C.; Sforza, C. Effect of leg dominance on the center-of-mass kinematics during an inside-of-the-foot kick in amateur soccer players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2014, 42, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, C.W.; Ekstrand, J.; Junge, A.; Andersen, T.E.; Bahr, R.; Dvorak, J.; Hägglund, M.; McCrory, P.; Meeuwisse, W.H.; McCrory, P.; et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants; WMA: Ferney-Voltaire, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R.B.; Õunpuu, S.; Tyburski, D.; Gage, J.R. A gait analysis data collection and reduction technique. Hum. Mov. Sci. 1991, 10, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Komnik, I.; Peters, M.; Funken, J.; Potthast, W. Identification and risk estimation of movement strategies during cutting maneuvers. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, W.T. Space Requirements of the Seated Operator; Geometrical, Kinematic, and Mechanical Aspects of the Body with Special Reference to the Limbs [WADC Technical Report]. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/AD0087892.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Brophy, R.H.; Backus, S.; Kraszewski, A.P.; Steele, B.C.; Ma, Y.; Osei, D.; Williams, R.J. Differences between sexes in lower extremity alignment and muscle activation during soccer kick. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2010, 92, 2050–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C. One-dimensional statistical parametric mapping in Python. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 15, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C.; Robinson, M.A.; Vanrenterghem, J. Region-of-interest analyses of one-dimensional biomechanical trajectories: Bridging 0D and 1D theory, augmenting statistical power. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.A.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Pataky, T.C. Sample size estimation for biomechanical waveforms: Current practice, recommendations and a comparison to discrete power analysis. J. Biomech. 2021, 122, 110451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, J.L.; Lehmann, E.L. Estimates of Location Based on Rank Tests. In Selected Works of E.L. Lehmann; Rojo, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, K.O.; Wong, S.P. A common language effect size statistic. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 111, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 1981, 6, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawilowsky, S.S. New effect size rules of thumb. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Meth. 2009, 8, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorborg, K.; Branci, S.; Stensbirk, F.; Jensen, J.; Hölmich, P. Copenhagen hip and groin outcome score (HAGOS) in male soccer: Reference values for hip and groin injury-free players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harøy, J.; Bache-Mathiesen, L.K.; Andersen, T.E. Lower HAGOS subscale scores associated with a longer duration of groin problems in football players in the subsequent season. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2024, 10, e001812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Taniguchi, K.; Kodesho, T.; Nakao, G.; Yokoyama, Y.; Saito, Y.; Katayose, M. Quantifying the shear modulus of the adductor longus muscle during hip joint motion using shear wave elastography. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhaj, K.; Meftah, S.; Mahir, L.; Lmidmani, F.; Elfatimi, A. Isokinetic imbalance of adductor-abductor hip muscles in professional soccer players with chronic adductor-related groin pain. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaenada-Carrilero, E.; Baraja-Vegas, L.; Blanco-Giménez, P.; Gallego-Estevez, R.; Bautista, I.J.; Vicente-Mampel, J. Association between hip/groin pain and hip ROM and strength in elite female soccer players. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, V.; Peñaranda, M.; Soler, A.; López-Samanes, Á.; Aagaard, P.; Del Coso, J. Effects of whole-season training and match-play on hip adductor and abductor muscle strength in soccer players: A pilot study. Sports Health 2022, 14, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.K.; Jayabalan, P.; Kibler, W.B.; Press, J. The kinetic chain revisited: New concepts on throwing mechanics and injury. PM R 2016, 8 (Suppl. l), S69–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, L.P.; Coyles, G.; Khaiyat, O. Alterations to the kinetic chain sequence after a shoulder injury in throwing athletes. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2024, 12, 23259671241288889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, M.B.; Arbuco, B.; Ryan, A.S.; Shipper, A.G.; Gray, V.L.; Addison, O. Systematic review of the importance of hip muscle strength, activation, and structure in balance and mobility tasks. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1651–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansourizadeh, R.; Letafatkar, A.; Khaleghi-Tazji, M. Does athletic groin pain affect the muscular co-contraction during a change of direction. Gait Posture 2019, 73, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, D.; Graham, J.; Screen, H.; Sinha, A.; Small, C.; Twycross-Lewis, R.; Woledge, R. Coronal plane hip muscle activation in football code athletes with chronic adductor groin strain injury during standing hip flexion. Man. Ther. 2012, 17, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.D.S.; Ocarino, J.M.; Cruz, A.C.; Barsante, L.D.; Teixeira, B.G.; Resende, R.A.; Fonseca, S.T.; Souza, T.R.; Souza, T.R. The trunk is exploited for energy transfers of maximal instep soccer kick: A power flow study. J. Biomech. 2021, 121, 110425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Peek, K.; Sanders, R.H.; Lee, J.; Pang, J.C.Y.; Ekanayake, K.; Fu, A.C.L. The role of upper body motions in stationary ball-kicking motion: A systematic review. J. Sci. Sport Exer. 2024, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, I.M.; Zoga, A.C.; Kavanagh, E.C.; Koulouris, G.; Bergin, D.; Gopez, A.G.; Morrison, W.B.; Meyers, W.C.; Meyers, W.C. Athletic pubalgia and “sports hernia”: Optimal MR imaging technique and findings. RadioGraphics 2008, 28, 1415–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Nunome, H.; Inoue, K.; Iga, T.; Akima, H. Electromyographic analysis of hip adductor muscles in soccer instep and side-foot kicking. Sports Biomech. 2020, 19, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechet, R.; Tisserand, R.; Fradet, L.; Colloud, F. Evidence of invariant lower-limb kinematics in anticipation of ground contact during drop-landing and drop-jumping. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2024, 98, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrdakovic, V.; Ilic, D.B.; Jankovic, N.; Rajkovic, Z.; Stefanovic, D. Pre-activity modulation of lower extremity muscles within different types and heights of deep jump. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2008, 7, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Severin, A.C.; Mellifont, D.B.; Sayers, M.G.L. Influence of previous groin pain on hip and pelvic instep kick kinematics. Sci. Med. Footb. 2017, 1, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, J.C.; McGill, S.M.; Brown, L.E. Anterior and posterior serape. Strength Cond. J. PDF 2015, 37, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullenkamp, A.M.; Campbell, B.M.; Laurent, C.M.; Lane, A.P. The contribution of trunk axial kinematics to poststrike ball velocity during maximal instep soccer kicking. J. Appl. Biomech. 2015, 31, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total (n = 20) | GP Group Mean (SD) n = 8 | Non-GP Group Mean (SD) n = 12 | p-Value | Estimated Difference | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.6 (3.5) | 25.5 (3.4) | 24.0 (3.6) | 0.364 | 1.5 | −1.88–4.88 |

| Height (cm) | 176.6 (6.3) | 174.3 (5.0) | 178.2 (6.8) | 0.178 | −3.9 | −9.79–1.96 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.3 (7.0) | 68.8 (4.6) | 71.3 (8.3) | 0.449 | −2.5 | −9.28–4.28 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 22.5 (1.5) | 22.6 (0.6) | 22.4 (1.9) | 0.210 | 0.2 | −1.26–1.68 |

| Soccer Experience (years) | 18.0 (3.6) | 18.1 (3.0) | 17.9 (4.0) | 0.902 | 0.2 | −3.31–3.72 |

| Position a | FW: 6/MF: 5/DF: 9 | FW: 4/MF: 1 /DF: 3 | FW: 2/MF:4 /DF: 6 | 0.189 | - | - |

| Ball Speed | ||||||

| Inside kick (m/s) | 23.7 (1.7) | 23.7 (1.5) | 23.7 (1.9) | 0.991 | 0.0 | −1.74–1.73 |

| In front kick (m/s) | 26.3 (2.2) | 25.9 (2.2) | 26.7 (2.2) | 0.443 | −0.8 | −2.93–1.34 |

| Inside Kick phase point | ||||||

| Max Hip Extension (%) | 45.7 (4.3) | 46.1 (4.6) | 45.5 (4.2) | 0.763 | 0.6 | −3.58–4.80 |

| Max Knee Flexion (%) | 75.4 (1.9) | 75.9 (2.2) | 75.1 (1.8) | 0.384 | 0.7 | −2.25–0.70 |

| Instep Kick phase point | ||||||

| Max Hip Extension (%) | 47.5 (3.5) | 48.6 (2.7) | 46.8 (3.8) | 0.265 | 1.8 | −1.49–5.10 |

| Max Knee Flexion (%) | 74.3 (2.0) | 74.5 (2.4) | 75.1(1.8) | 0.777 | 0.3 | −1.71–2.25 |

| HAGOS Subscale | GP Group Mean (SD) n = 8 | Non-GP Group Mean (SD) n = 12 | p-Value | Hodges-Lehmann Estimate | 95% CI | Effect Size ([CLES]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 93.4 (10.0) | 99.2 (2.9) | 0.047 * | 2.5 | 0.0–15.0 | 0.77 |

| Symptoms | 84.4 (10.3) | 92.9 (7.6) | 0.069 | 7.1 | 0.0–17.9 | 0.75 |

| ADL | 100.0 (0.0) | 99.6 (1.4) | 0.792 | 0.0 | 0.0–0.0 | 0.46 |

| Sport/Rec | 89.8 (15.9) | 97.7 (7.2) | 0.082 | 3.1 | 0.0–18.8 | 0.73 |

| PA | 85.9 (35.0) | 93.8 (10.0) | 0.851 | 0.0 | −12.5–0.0 | 0.47 |

| QOL | 76.3 (26.1) | 98.3 (4.4) | 0.003 ** | 10.0 | 5.0–45.0 | 0.89 |

| Category | Parameter | Side | p-Value | Time Interval(s) of Significant Difference (% of Kick Cycle) | Effect Size (Hedges’ g) | Movement Direction | Group Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle | Hip Flexion/Extension (°) | KL | 0.027 * | 21.34–39.57 | 1.52 | −: Extension | GP > non-GP |

| Hip Abduction/Adduction (°) | KL | <0.001 *** | 14.93–100.00 | 0.83 | −: Abduction | non-GP > GP | |

| SL | <0.001 *** | 14.71–93.51 | −1.79 | −: Abduction | non-GP > GP | ||

| Thorax-Pelvis Lateral Flexion (°) | — | 0.030 * | 86.59–100.00 | −1.63 | +: Right lateral flexion | non-GP > GP | |

| Thorax-Pelvis Rotation (°) | — | 0.019 * | 76.00–96.65 | −1.39 | +: Right Axial Rotation/ −: Left Axial Rotation | non-GP > GP | |

| Angular Velocity | Hip Abduction/Adduction (deg/s) | KL | 0.006 **, 0.043 * | 19.01–30.71, 96.00–100 | −1.68, 1.62 | −: Abduction, + Adduction | non-GP > GP, GP > non-GP |

| SL | <0.001 *** | 3.10–21.43 | −1.72 | −: Abduction | non-GP > GP | ||

| Pelvis Tilt (deg/s) | — | 0.046 * | 96.36–100.00 | −1.60 | −: Posterior Tilt | non-GP > GP | |

| Pelvis Obliquity (deg/s) | — | 0.044 * | 82.15–84.1 | −1.46 | +: Right down/−: Left Down | non-GP > GP | |

| Thorax-Pelvis Lateral Flexion (deg/s) | — | 0.030 * | 91.97–100.00 | −1.53 | −: Left lateral flexion | non-GP > GP | |

| Thorax-Pelvis Rotation (deg/s) | — | 0.005 ** | 47.45–62.40 | −1.93 | +: Right Axial Rotation | non-GP > GP | |

| Angular Acceleration | Hip Abduction/Adduction (deg/s2) | SL | 0.032 *, 0.029 * | 21.21–24.80, 78.38–82.08 | 1.57, 1.70 | +: Positive/−: Negative, +: Positive | GP > non-GP, GP > non-GP |

| Hip Rotation (deg/s2) | KL | 0.002 ** | 42.13–50.63 | 2.17 | +: Positive | GP > non-GP | |

| Power | Hip Abduction/Adduction (W/kg) | SL | 0.048 * | 0.00–1.46 | 2.04 | +: Positive values | GP > non-GP |

| COM-COP distance | Medio-Lateral (mm) | — | 0.049 *, 0.049 * | 60.18–62.38, 83.15–85.10 | −0.86, −0.74 | −: Towards the supporting leg, −: Towards the supporting leg | non-GP > GP, non-GP > GP |

| Category | Parameter | Side | p-Value | Time Interval(s) of Significant Difference (% of Kick Cycle) | Effect Size (Hedges’ g) | Movement Direction | Group Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle | Hip Abduction/Adduction (°) | KL | <0.001 *** | 20.39–100.00 | −3.12 | −: Abduction | non-GP > GP |

| SL | <0.001 ***, 0.027 * | 14.77–67.80, 68.20–85.28 | −1.71, −1.36 | −: Abduction | non-GP > GP | ||

| Thorax-Pelvis Rotation (°) | — | 0.040 * | 82.52–100.00 | −1.36 | +: Right Axial Rotation | non-GP > GP | |

| Angular Velocity | Hip Flexion/Extension (deg/s) | KL | 0.044 * | 83.77–86.89 | 1.47 | +: Flexion | GP > non-GP |

| SL | 0.035 * | 58.65–62.69 | −1.59 | −: Extension | non-GP > GP | ||

| Hip Abduction/Adduction (deg/s) | KL | < 0.001 ***, 0.033 * | 26.10–41.25, 94.57–98.55 | −1.98, 1.64 | −: Abduction | non-GP > GP | |

| SL | 0.013 * | 6.84–16.43 | −1.60 | −: Abduction | non-GP > GP | ||

| Pelvis Tilt (deg/s) | — | 0.029 * | 93.56–100.00 | −2.07 | −: Posterior Tilt | non-GP > GP | |

| Thorax-Pelvis Flexion/Extension (deg/s) | — | < 0.001 *** | 0–21.34 | 2.03 | −: Extension | GP > non-GP | |

| Thorax-Pelvis Lateral Flexion (deg/s) | — | 0.037 * | 93.29–100 | −1.69 | −: Left lateral flexion | non-GP > GP | |

| Thorax-Pelvis Rotation (deg/s) | — | 0.005 ** | 47.45–62.40 | −1.19 | +: Right Axial Rotation | non-GP > GP | |

| Angular Acceleration | Hip Flexion/Extension (deg/s2) | SL | 0.026 * | 67.87–71.53 | 1.67 | −: Negative | GP > non-GP |

| Hip Abduction/Adduction (deg/s2) | KL | 0.040 * | 85.66–87.81 | 1.73 | +: Positive | GP > non-GP | |

| SL | 0.031 * | 77.77–81.35 | 1.71 | +: Positive | GP > non-GP | ||

| Pelvis Obliquity (deg/s2) | — | 0.013 * | 43.73–48.74 | 1.96 | +: Positive/−: Negative | GP > non-GP | |

| Thorax-Pelvis Lateral Flexion (deg/s2) | — | 0.014 * | 78.38–84.96 | −1.90 | −: Negative | non-GP > GP | |

| Moment | Hip Flexion/Extension (N.mm/kg) | KL | 0.048 * | 48.68–49.66 | −1.55 | +: Flexion moment | non-GP > GP |

| SL | 0.043 * | 12.66–15.39 | 1.59 | −: Extension moment | GP > non-GP | ||

| Hip Abduction/Adduction (N.mm/kg) | SL | < 0.001 *** | 41.00–60.33 | 2.37 | +: Adduction moment | GP > non-GP | |

| Power | Hip Flexion/Extension (W/kg) | KL | 0.045 * | 60.43–62.03 | −1.62 | +: Positive values | non-GP > GP |

| SL | 0.045 * | 12.50–14.93 | 1.44 | +: Positive values | GP > non-GP | ||

| Hip Abduction/Adduction (W/kg) | KL | 0.040 * | 44.77–47.20 | −1.57 | −: Negative values | non-GP > GP | |

| SL | 0.025 * | 58.79–64.64 | 1.62 | +: Positive values | GP > non-GP | ||

| COM-COP distance | Medio-Lateral (mm) | — | 0.050 * | 71.95–72.04 | −0.26 | −: Towards the supporting leg | GP > non-GP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sugano, T.; Kuboshita, R.; Hayashi, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hitosugi, M. Effects of a History of Adductor-Related Groin Pain on Kicking Biomechanics and HAGOS Subscales in Male Soccer Players: A Comprehensive Analysis Using 1D-SPM. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212003

Sugano T, Kuboshita R, Hayashi S, Kobayashi Y, Hitosugi M. Effects of a History of Adductor-Related Groin Pain on Kicking Biomechanics and HAGOS Subscales in Male Soccer Players: A Comprehensive Analysis Using 1D-SPM. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSugano, Tomonari, Ryo Kuboshita, Seigaku Hayashi, Yasutaka Kobayashi, and Masahito Hitosugi. 2025. "Effects of a History of Adductor-Related Groin Pain on Kicking Biomechanics and HAGOS Subscales in Male Soccer Players: A Comprehensive Analysis Using 1D-SPM" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212003

APA StyleSugano, T., Kuboshita, R., Hayashi, S., Kobayashi, Y., & Hitosugi, M. (2025). Effects of a History of Adductor-Related Groin Pain on Kicking Biomechanics and HAGOS Subscales in Male Soccer Players: A Comprehensive Analysis Using 1D-SPM. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212003