DFT-Computation-Assisted EPR Study on Oxalate Anion-Radicals, Generated in γ-Irradiated Polycrystallites of H2C2O4·2H2O, Cs2C2O4, and K2C2O4·H2O

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

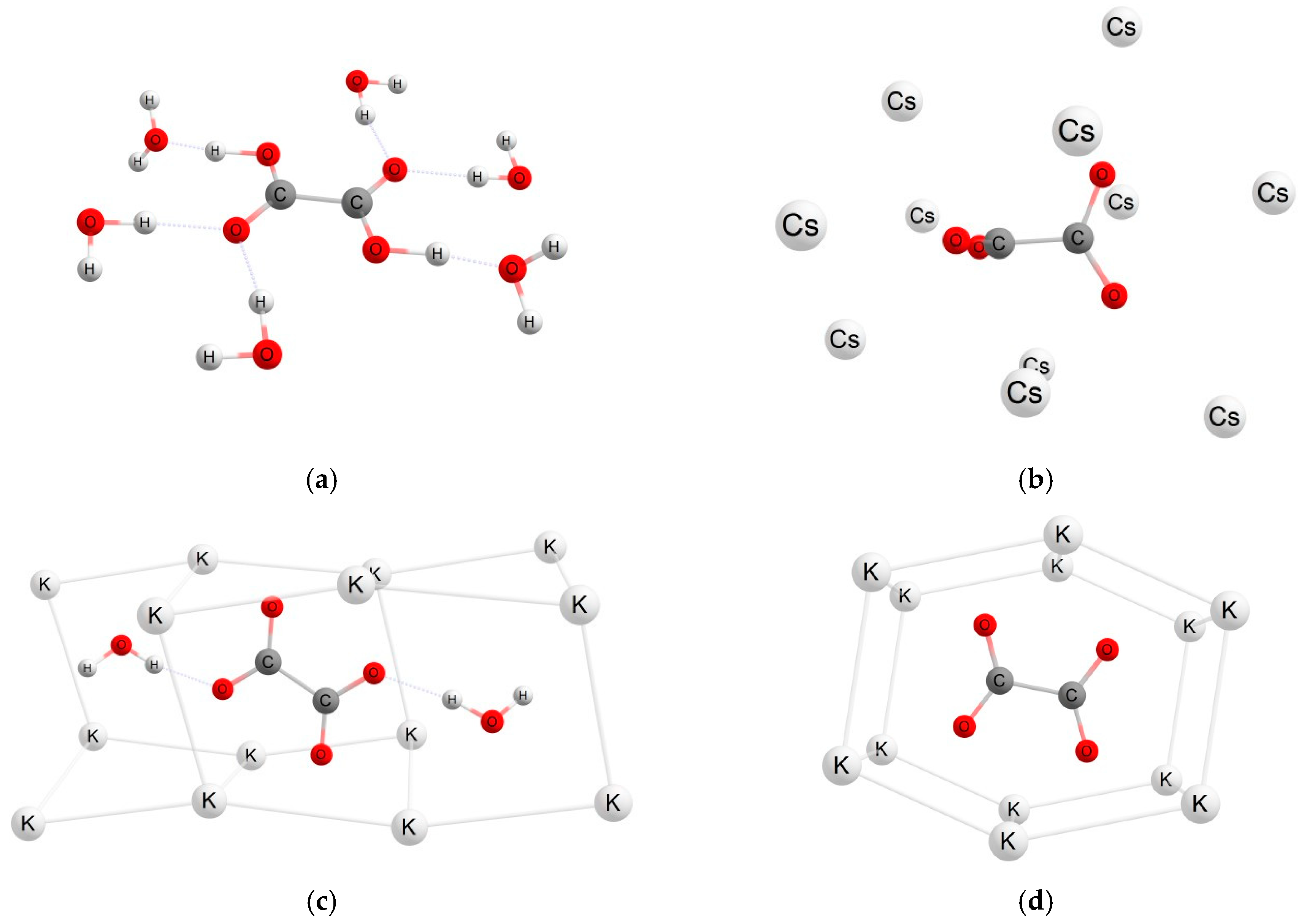

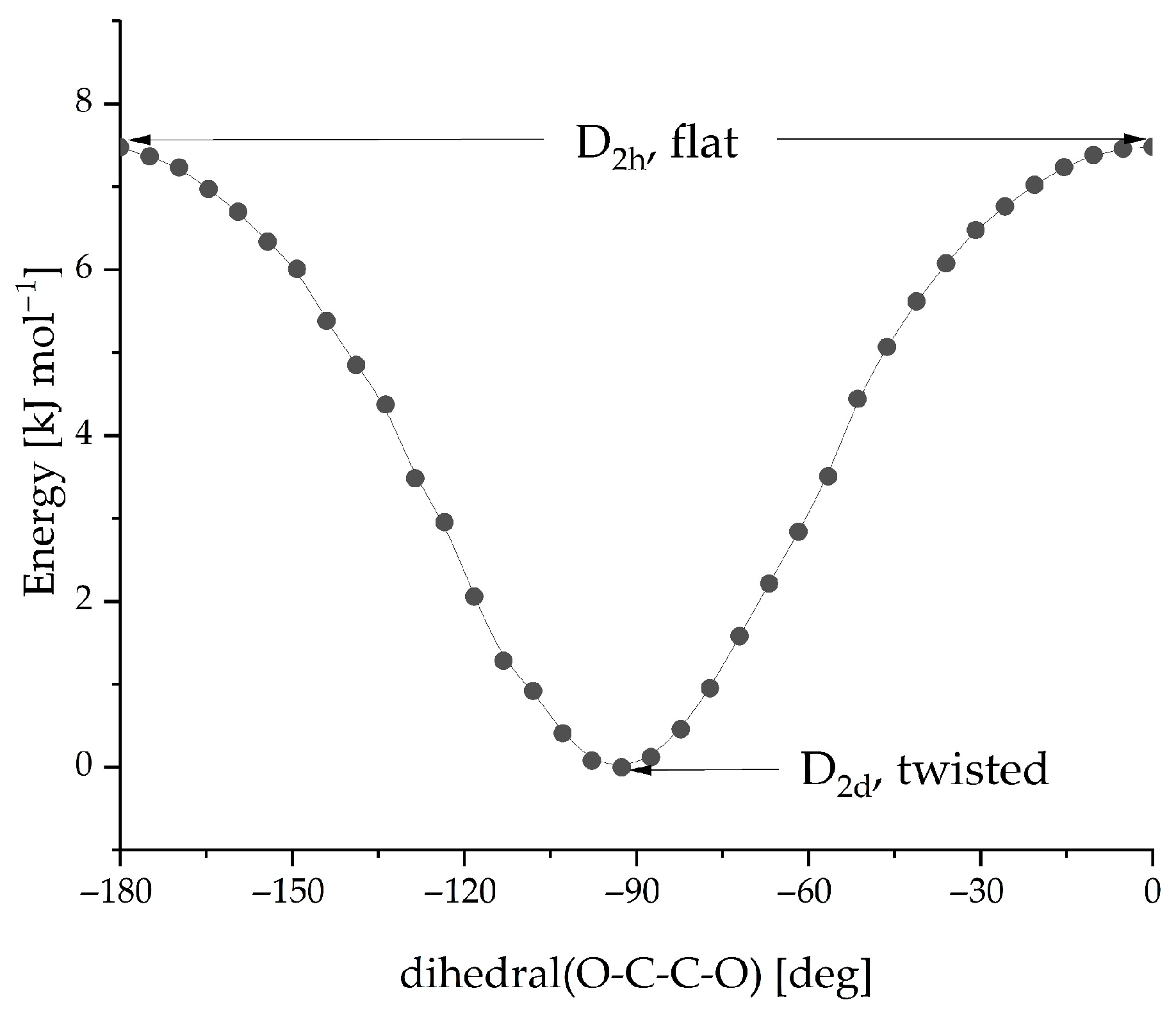

3.1. Validation of DFT Calculations

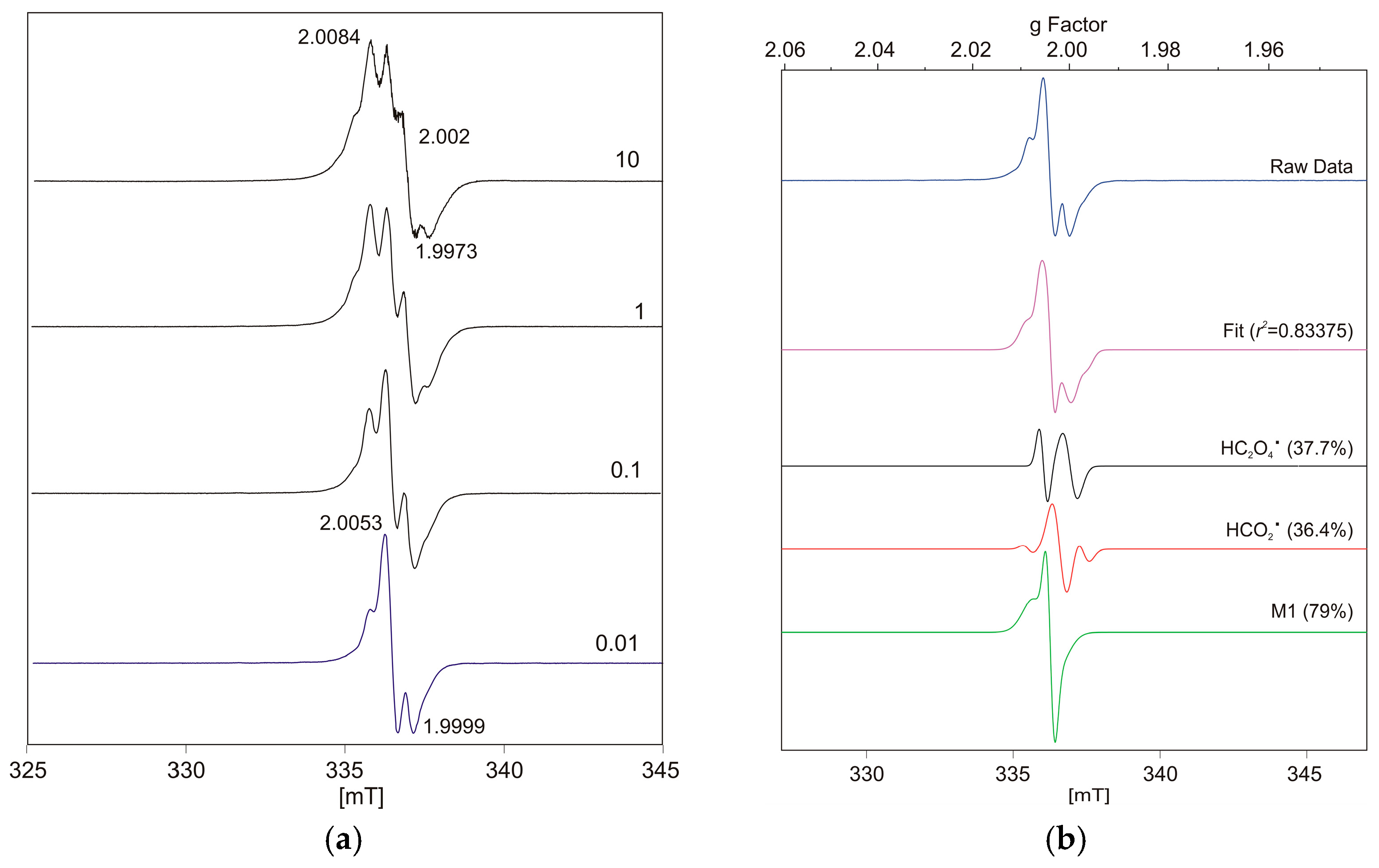

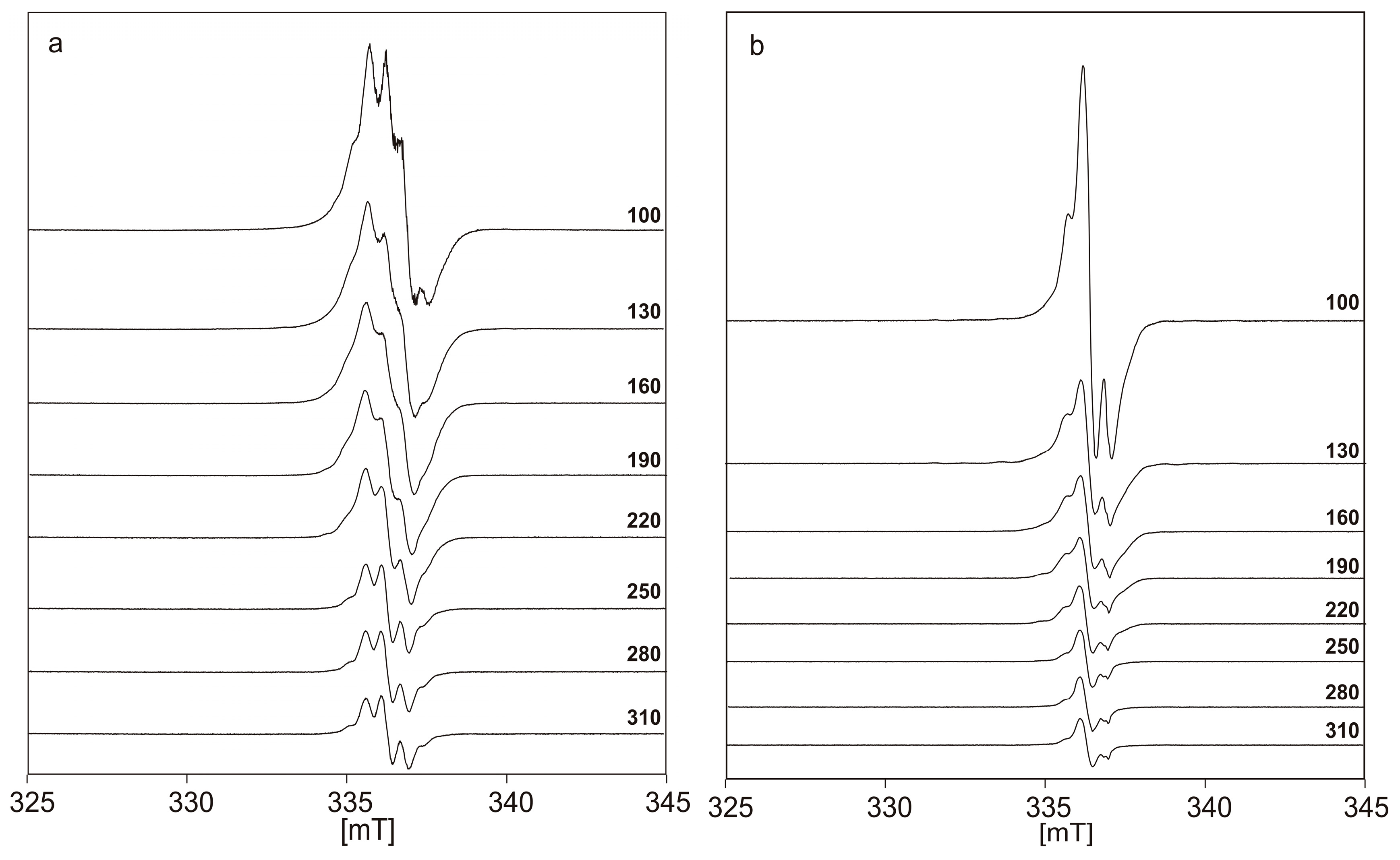

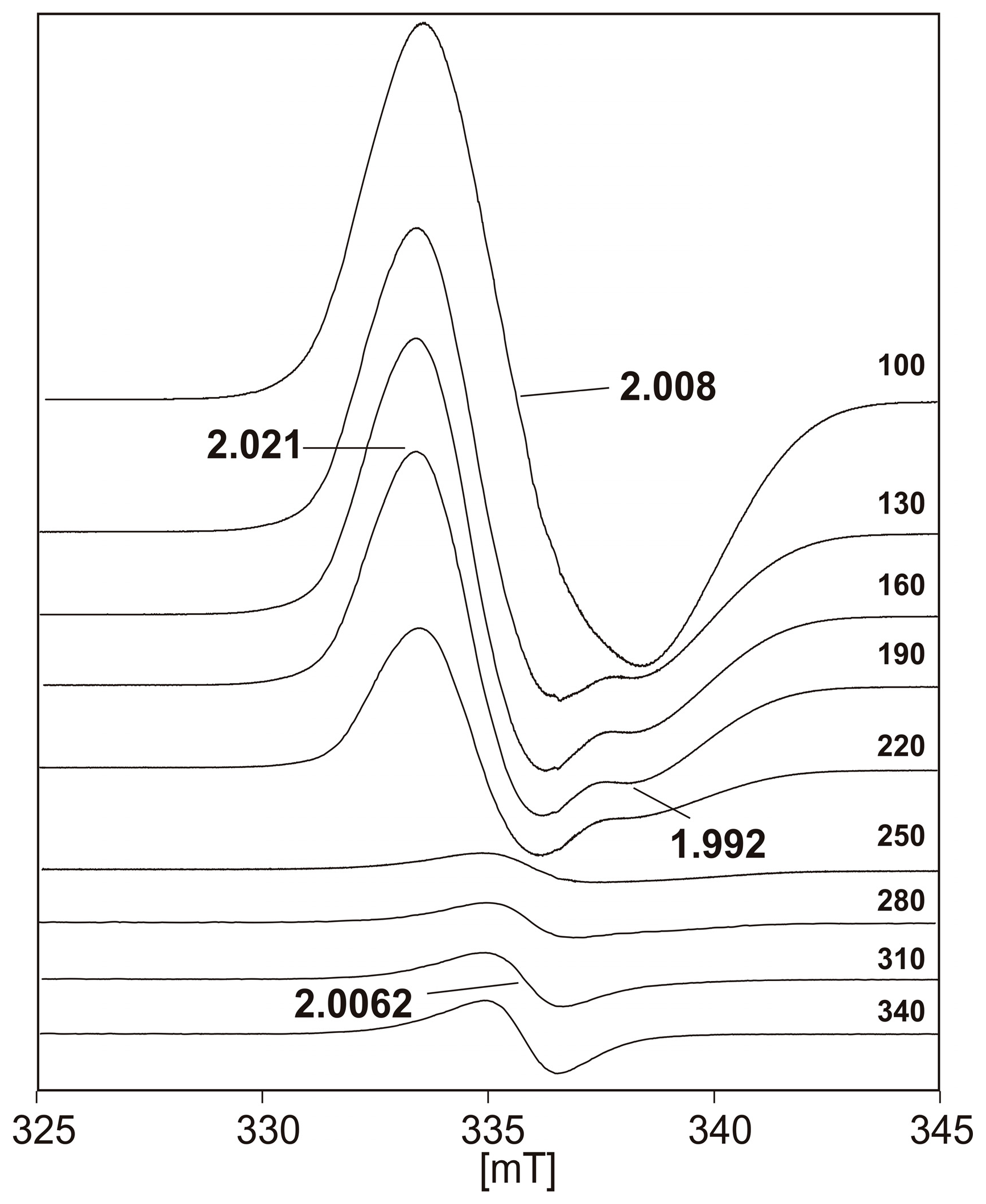

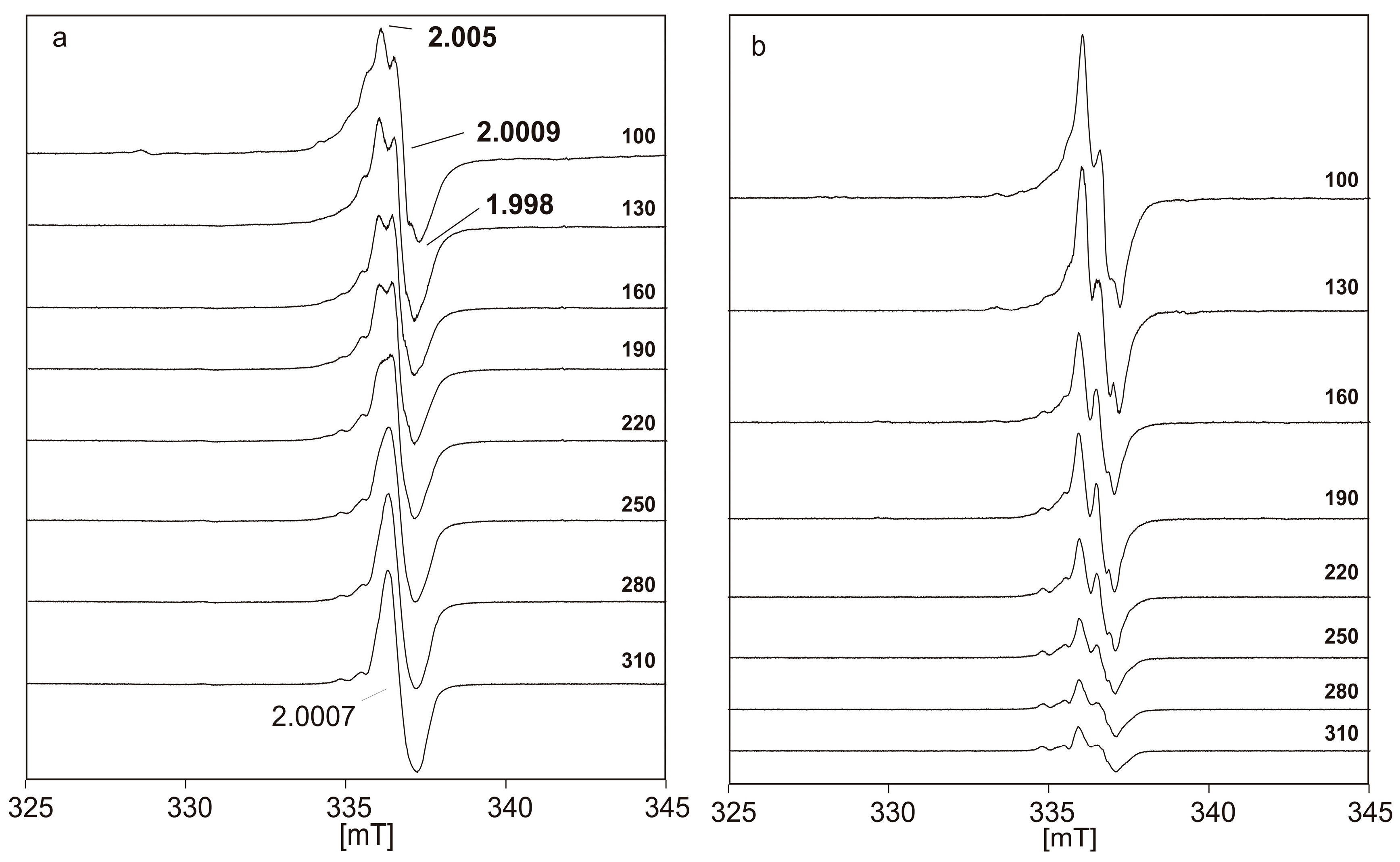

3.2. The EPR Experiment and Numerical Correlation with DFT Calculations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSD | The Cambridge Structural Database |

| CCDC | The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/ |

| COD | The Crystallography Open Database, http://www.crystallography.net/ |

| PubChem | The open chemistry database, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| EPR | Electron Paramagnetic Resonance |

References

- Köseoğlu, R.; Köseoğlu, E.; Köksal, F.; Başaran, E.; Demirci, D. EPR of Some Irradiated Renal Stones. Radiat. Meas. 2005, 40, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosulin, I.S.; Lisouskaya, A. Structure and Kinetics of Organic Acid Radicals Formed in Reaction with •OH Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 7558–7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imaram, W.; Saylor, B.T.; Centonze, C.P.; Richards, N.G.; Angerhofer, A. EPR Spin Trapping of an Oxalate-Derived Free Radical in the Oxalate Decarboxylase Reaction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.V.V.S.; Lingam, K.V.; Gundu Rao, T.K. Studies of Radicals in Oxalate Systems. Mol. Phys. 1980, 41, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffan, C.R.; Bakac, A.; Espenson, J.H. Quenching of the Doublet Excited State of Tris(Polypyridine) Chromium(III) Ions by Oxalate Ions: An Example of Irreversible Electron Transfer. Inorg. Chem. 1989, 28, 2992–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulazzani, Q.G.; D’Angelantonio, M.; Venturi, M.; Hoffman, M.Z.; Rodgers, M.A.J. Interaction of Formate and Oxalate Ions with Radiation-Generated Radicals in Aqueous Solution. Methylviologen as a Mechanistic Probe. J. Phys. Chem. 1986, 90, 5347–5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, T.; Zhou, M.; Johnson, S.; Ahn, H.S.; Bard, A.J. Direct Observation of C2O4•− and CO2•− by Oxidation of Oxalate within Nanogap of Scanning Electrochemical Microscope. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16178–16183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billing, R.; Rehorek, D.; Hennig, H. Photoinduced Electron Transfer in Ion Pairs R. In Photoinduced Electron Transfer II; Topics of Current Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; Volume 2, pp. 151–200. ISBN 3-540-52568-X. [Google Scholar]

- Huie, R.E.; Clifton, C.L. Kinetics of the Reaction of the Sulfate Radical with the Oxalate Anion. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1996, 28, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Andrews, L. Infrared Spectra of the C2O4+ Cation and C2O4− Anion Isolated in Solid Neon. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6820–6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, X.; Yan, Y.; Chen, G.; Sun, L.; Wang, L.; Wen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Recent Advances of Oxalate Decarboxylase: Biochemical Characteristics, Catalysis Mechanisms, and Gene Expression and Regulation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 10163–10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, P.; Luque, R. (Eds.) Introduction to Nanocatalysts. In Nanoparticle Design and Characterization for Catalytic Applications in Sustainable Chemistry; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–36. ISBN 978-1-78801-490-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Clavaguéra, C.; Hu, C.; Denisov, S.A.; Shen, S.; Hu, F.; Ma, J.; Mostafavi, M. Direct Time-Resolved Observation of Surface-Bound Carbon Dioxide Radical Anions on Metallic Nanocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, M.R.; Vyas, S. Role of Explicit Solvation and Level of Theory in Predicting the Aqueous Reduction Potential of Carbonate Radical Anion by DFT. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 6867–6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Volpe, C.; Giustiniano, M. The Multiple Facets of Oxalate Dianion in Photochemistry. ChemPhotoChem 2025, 9, e202400407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wasgestian, F. Photocatalytic Reduction of Nitrate Ions on TiO2 by Oxalic Acid. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 1998, 112, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P. Photocatalytic Decomposition of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) by TiO2 in the Presence of Oxalic Acid. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, J.-M.; Mozzanega, M.-N.; Pichat, P. Oxidation of Oxalic Acid in Aqueous Suspensions of Semiconductors Illuminated with UV or Visible Light. J. Photochem. 1983, 22, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, P.; Zhao, H. Adsorption and Oxidation of Oxalic Acid on Anatase TiO2 (001) Surface: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 454, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, N.T.; Hanna, K.; Boily, J.-F. Water Film-Mediated Photocatalytic Oxidation of Oxalate on TiO2. J. Catal. 2024, 432, 115425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, R.C.; Franklin, J.; Berger, U.; Conder, J.M.; Cousins, I.T.; de Voogt, P.; Jensen, A.A.; Kannan, K.; Mabury, S.A.; van Leeuwen, S.P. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment: Terminology, Classification, and Origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2011, 7, 513–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlewicz, G.; Richard, A.M.; Williams, A.J.; Grulke, C.M.; Sams, R.; Lambert, J.; Noyes, P.D.; DeVito, M.J.; Hines, R.N.; Strynar, M.; et al. A Chemical Category-Based Prioritization Approach for Selecting 75 Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) for Tiered Toxicity and Toxicokinetic Testing. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisała, J.; Goclon, J.; Pogocki, D. Reductive Dehalogenation—Challenges of Perfluorinated Organics. J. Photocat. 2021, 2, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogocki, D.; Kisała, J.; Bankiewicz, B.; Goclon, J.; Kolek, P.; Szreder, T. Reduction Potentials of Perfluorinated Organic Acids in Alkaline Polar Solvents. Computational Thermodynamic Insight into the Electron-Attachment Induced Defluorination. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 397, 123929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.; Von Ragué Schleyer, P. Conformational Preferences of 34 Valence Electron A2X4 Molecules: An Ab Initio Study of B2F4, B2Cl4, N2O4, and C2O. J. Comp. Chem. 1981, 2, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M.J.S.; Zheng, Y.-J. Structure of the Oxalate Ion. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 1990, 209, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beagley, B.; Small, R.W.H. The Structure of Lithium Oxalate. Acta Crystallogr. 1964, 17, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, D.A.; Olmstead, M.M. Sodium Oxalate Structure Refinement. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1981, 37, 938–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jestilä, J.S.; Denton, J.K.; Perez, E.H.; Khuu, T.; Aprà, E.; Xantheas, S.S.; Johnson, M.A.; Uggerud, E. Characterization of the Alkali Metal Oxalates (MC2O4−) and Their Formation by CO2 Reduction via the Alkali Metal Carbonites (MCO2−). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 7460–7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molt, R.W., Jr.; Lecher, A.M.; Clark, T.; Bartlett, R.J.; Richards, N.G.J. Facile Csp2–Csp2 Bond Cleavage in Oxalic Acid-Derived Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3248–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, P.A.W. The Oxalate Dianion, C2O42−: Planar or Nonplanar? J. Chem. Educ. 2012, 89, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.I.; Pullman, D.P. Determining the Structure of Oxalate Anion Using Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy Coupled with Gaussian Calculations. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93, 1130–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longetti, L.; Barillot, T.R.; Puppin, M.; Ojeda, J.; Poletto, L.; van Mourik, F.; Arrell, C.A.; Chergui, M. Ultrafast Photoelectron Spectroscopy of Photoexcited Aqueous Ferrioxalate. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 25308–25316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnebier, R.E.; Vensky, S.; Panthöfer, M.; Jansen, M. Crystal and Molecular Structures of Alkali Oxalates: First Proof of a Staggered Oxalate Anion in the Solid State. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echigo, T.; Kimata, M. The Common Role of Water Molecule and Lone Electron Pair as a Bond-Valence Mediator in Oxalate Complexes: The Crystal Structures of Rb2(C2O4) H2O and Tl2(C2O4). Z. Krist.-Cryst. Mater. 2006, 221, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, J.A.; Bolton, J.R. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Elementary Theory and Practical Applications; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-471-75496-1. [Google Scholar]

- Casati, N.; Macchi, P.; Sironi, A. Hydrogen Migration in Oxalic Acid Di-Hydrate at High Pressure? Chem. Commun. 2009, 2679–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidambaram, R.; Sequeira, A.; Sikka, S.K. Neutron-Diffraction Study of the Structure of Potassium Oxalate Monohydrate: Lone-Pair Coordination of the Hydrogen-Bonded Water Molecule in Crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 1964, 41, 3616–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-Functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for h to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward Reliable Density Functional Methods without Adjustable Parameters: The PBE0 Model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical Hybrid Density Functional with Perturbative Second-Order Correlation. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 034108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardirossian, N.; Head-Gordon, M. Survival of the Most Transferable at the Top of Jacob’s Ladder: Defining and Testing the ωB97M(2) Double Hybrid Density Functional. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 241736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.A.; Neese, F. Double-Hybrid Density Functional Theory for g-Tensor Calculations Using Gauge Including Atomic Orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 054105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellweg, A.; Rappoport, D. Development of New Auxiliary Basis Functions of the Karlsruhe Segmented Contracted Basis Sets Including Diffuse Basis Functions (Def2-SVPD, Def2-TZVPPD, and Def2-QVPPD) for RI-MP2 and RI-CC Calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V. Structure, Magnetic Properties and Reactivities of Open-Shell Species from Density Functional and Self-Consistent Hybrid Methods. In Recent Advances in Density Functional Methods, Part I; Chong, D.P., Ed.; World Scientific Publ. Co.: Singapore, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rappoport, D.; Furche, F. Property-Optimized Gaussian Basis Sets for Molecular Response Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 134105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA Program System. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Becker, U.; Riplinger, C. The ORCA Quantum Chemistry Program Package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 224108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System-Version 5.0. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Prediction of Electron Paramagnetic Resonance g Values Using Coupled Perturbed Hartree-Fock and Kohn-Sham Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 11080–11096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. An Improvement of the Resolution of the Identity Approximation for the Formation of the Coulomb Matrix. J. Comp. Chem. 2003, 24, 1740–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmich-Paris, B. A Trust-Region Augmented Hessian Implementation for Restricted and Unrestricted Hartree–Fock and Kohn–Sham Methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 164104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Efficient and Accurate Approximations to the Molecular Spin-Orbit Coupling Operator and Their Use in Molecular g-Tensor Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 034107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Hansen, A.; Becker, U. Efficient, Approximate and Parallel Hartree-Fock and Hybrid DFT Calculations. A “chain-of-Spheres” Algorithm for the Hartree-Fock Exchange. Chem. Phys. 2009, 356, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmich-Paris, B.; de Souza, B.; Neese, F.; Izsák, R. An Improved Chain of Spheres for Exchange Algorithm. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 104109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The SHARK Integral Generation and Digestion System. J. Comp. Chem. 2022, 44, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustolon, M. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: A Practitioner’s Toolkit; John Wiley & Son: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-470-43222-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bhide, M.; Kadam, R.M.; Babu, Y.; Natarajan, V.; Sastry, M. EPR and ENDOR Studies of Self (α) -Irradiation Effects in Pu(VI) Oxalate: Evidence for Participation of 5f Electrons of 239Pu in Chemical Bonding with CO2−. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 332, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunsford, J.H.; Jayne, J.P. Formation of CO2− Radical Ions When CO2 Is Adsorbed on Irradiated Magnesium Oxide. J. Phys. Chem. 1965, 69, 2182–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.R.; Reiher, M. Spin in Density-Functional Theory. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2012, 112, 3661–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debuyst, R.; Dejehet, F.; Idrissi, S. Isotropic CO3 and CO2 Radicals in Gamma Irradiated Monohydrocalcite. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 1993, 47, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroh, J. Elektrony w Chemii Radiacyjnej Układów Skondensowanych. [Electrons in Radiation Chemistry of Condensed Systems]; Ossolineum: Wrocław, Poland, 1980; ISBN 83-04-00222-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, P.L.; Gottschall, W.C. Gamma Radiolysis of Oxalic Acid and Selected Metal Oxalates. Radiat. Res. 1976, 68, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, Y.; Houk, K.N. Benchmarking the Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM) for Aqueous Solvation Free Energies of Neutral and Ionic Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2004, 1, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, C.J.; Mayer, P.M.; Radom, L. An Assessment of Theoretical Procedures for the Calculation of Reliable Radical Stabilization Energies. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1999, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurečka, P.; Šponer, J.; Černý, J.; Hobza, P. Benchmark Database of Accurate (MP2 and CCSD(T) Complete Basis Set Limit) Interaction Energies of Small Model Complexes, DNA Base Pairs, and Amino Acid Pairs. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanon, M.; Rajzmann, M.; Chanon, F. One Electron More, One Electron Less. What Does It Change? Activations Induced by Electron Transfer. The Electron, an Activating Messenger. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 6193–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, A.L.J. Regio-Selectivity and Stereo-Selectivity in Radical Reactions. Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 3073–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossey, J.; Lefort, D.; Sorba, J. Free Radicals in Organic Chemistry; Willey & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

| Radical System (M Model) | DFT Functional | Basis Set | gavg (Calculated) | gavg (Experiment) | Δg (×103) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC2O4• (M1) | RI-B2PLYP | def2-QZVPP | 2.00361 | 2.0035 | 0.11 |

| (H2C2O4) | PBE0 | def2-TZVPD | 2.00356 | 0.06 | |

| B3LYP | def2-QZVPD | 2.00372 | 0.22 | ||

| C2O4•− (M2) | RI-B2PLYP | def2-QZVPP | 2.00562 | 2.008 | 2.38 |

| (Cs2C2O4) | PBE0 | def2-QZVPD | 2.00694 | 1.06 | |

| B3LYP | def2-QZVPD | 2.0075 | 0.5 | ||

| C2O4•− (M4) | RI-B2PLYP | def2-QZVPP | 2.01179 | 2.0013 | 10.49 |

| (K2C2O4) | PBE0 | def2-TZVP | 2.01505 | 13.75 | |

| B3LYP | def2-TZVP | 2.01821 | 16.91 | ||

| CO2•− (Gas Phase) | RI-B2PLYP | def2-QZVPP | 2.00074 | ||

| PBE0 | def2-QZVPD | 2.00074 | |||

| B3LYP | def2-QZVPD | 2.00074 |

| Dominant Signal | HCO2• Contribution (Orthorhombic, gavg ≈ 2.0026) | HC2O4• Contribution (Axial, gavg ≈ 2.0035) | r2 (Fit Quality) | ν [GHz] | Power (P) [mW] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance | 44.2% | 44.4% | 0.796 | 9.43790 | 10.81 |

| HCO2• | 55.4% | 52.3% | 0.879 | 9.43820 | 1.045 |

| HC2O4• | 21.3% | 51.3% | 0.904 | 9.43783 | 0.1027 |

| HC2O4• (M1) | 36.4% | 37.7% | 0.834 | 9.43786 | 0.01016 * |

| Tmeas [K] | r2 (p ≈ 0.01 mW) | r2 (p ≈ 10.7 mW) |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0.8337 * | 0.7959 |

| 130 | −0.0195 | 0.6978 |

| 160 | −0.9954 | 0.5477 |

| 190 | −2.8536 | 0.2775 |

| 220 | −4.7217 | −0.1297 |

| 250 | −9.6869 | −1.7954 |

| 280 | −10.4314 | −2.5426 |

| 310 | −14.8533 | −3.6690 |

| CO2•− (gavg = 2.0007) | C2O4•− (D2h, gavg = 2.0118) | C2O4•− (D2d, gavg = 2.0056) | r2 (Fit Quality) | p [mW] | Tmeas [K] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42.0% | 0.0% | 58.0% | 0.994 | 10.78 | 100 |

| 28.1% | 0.0% | 71.9% | 0.975 | 10.76 | 130 |

| 0.7% | 72.7% | 26.6% | −1.537 | 10.78 | 250 |

| 10.0% | 26.8% | 63.2% | −0.133 | 10.71 | 310 |

| C2O4•− EXP (gavg ≈ 2.0013) | CO2•− (gavg ≈ 2.0007) | C2O4•− DFT (gavg ≈ 2.0118) | r2 (Fit Quality) | p [mW] | Tmeas [K] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23.6% | 12.4% | 44.6% | 0.5728 | 1.039 | 100 |

| 65.3% | 11.7% | 5.4% | 0.4975 | 1.038 | 130 |

| 21.4% | 8.8% | 53.8% | −0.4097 | 10.71 | 190 |

| 24.1% | 7.7% | 57.3% | −1.1547 | 1.054 | 250 |

| 26.8% | 8.6% | 58.5% | −1.1339 | 10.78 | 310 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sadło, J.; Pogocki, D. DFT-Computation-Assisted EPR Study on Oxalate Anion-Radicals, Generated in γ-Irradiated Polycrystallites of H2C2O4·2H2O, Cs2C2O4, and K2C2O4·H2O. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11898. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211898

Sadło J, Pogocki D. DFT-Computation-Assisted EPR Study on Oxalate Anion-Radicals, Generated in γ-Irradiated Polycrystallites of H2C2O4·2H2O, Cs2C2O4, and K2C2O4·H2O. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11898. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211898

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadło, Jarosław, and Dariusz Pogocki. 2025. "DFT-Computation-Assisted EPR Study on Oxalate Anion-Radicals, Generated in γ-Irradiated Polycrystallites of H2C2O4·2H2O, Cs2C2O4, and K2C2O4·H2O" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11898. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211898

APA StyleSadło, J., & Pogocki, D. (2025). DFT-Computation-Assisted EPR Study on Oxalate Anion-Radicals, Generated in γ-Irradiated Polycrystallites of H2C2O4·2H2O, Cs2C2O4, and K2C2O4·H2O. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11898. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211898