Semi-Automatic Extraction and Analysis of Health Equity Covariates in Registered Research Projects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

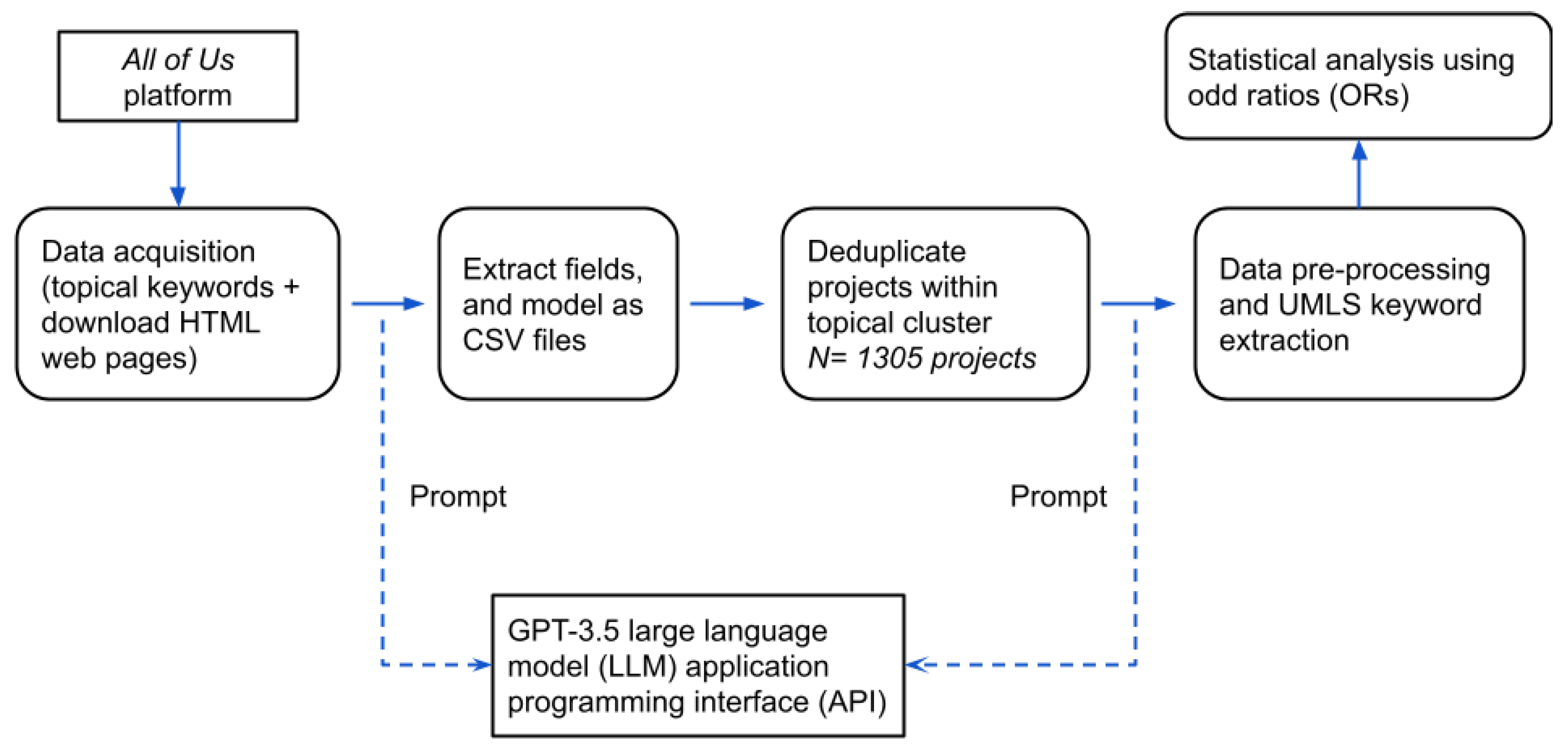

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The All of Us Research Hub

3.2. Theoretical Review

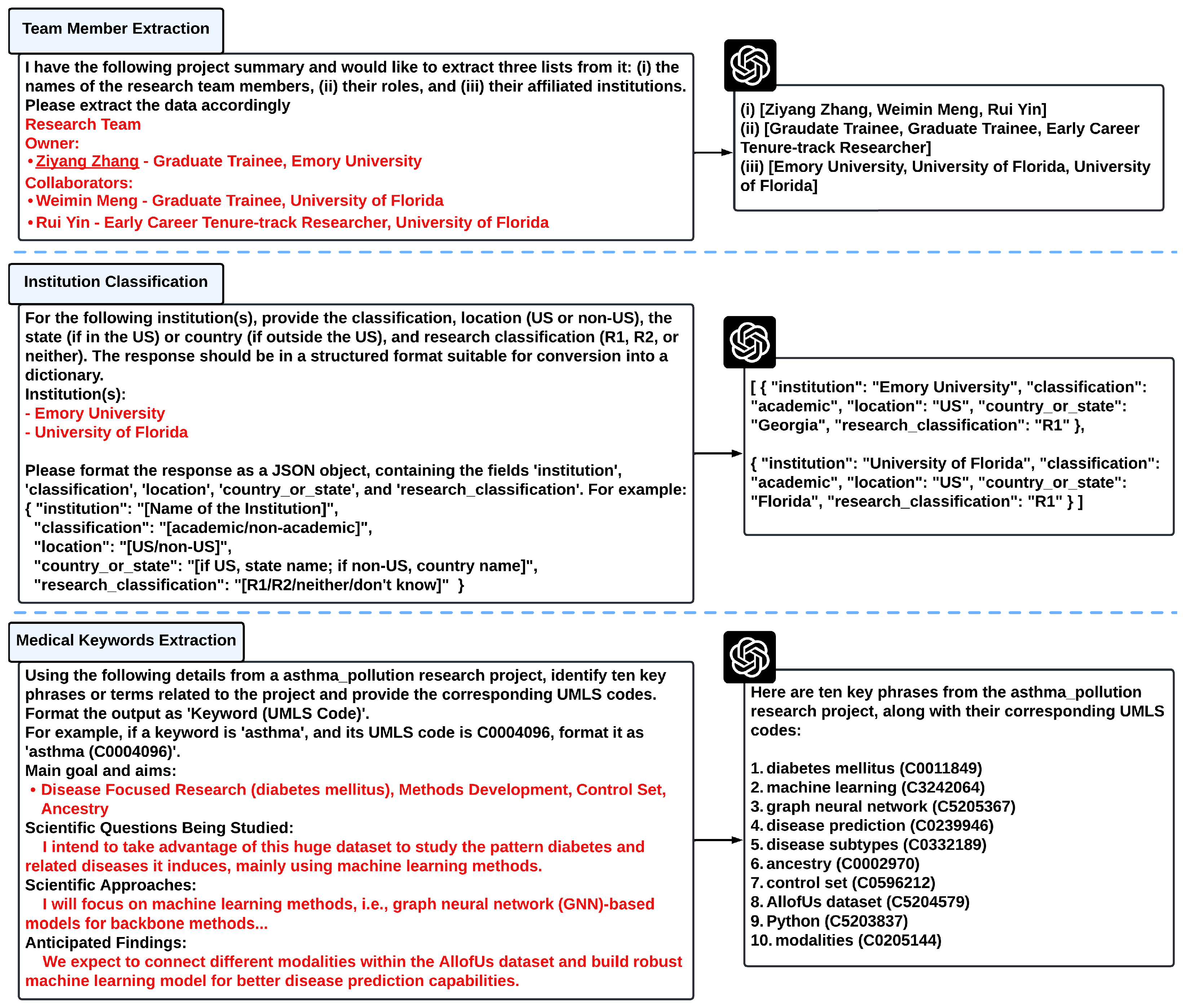

3.3. Data Acquisition and Field Extraction

3.4. Deduplication of Projects

3.5. Preprocessing and Keyword Extraction

3.6. Analysis

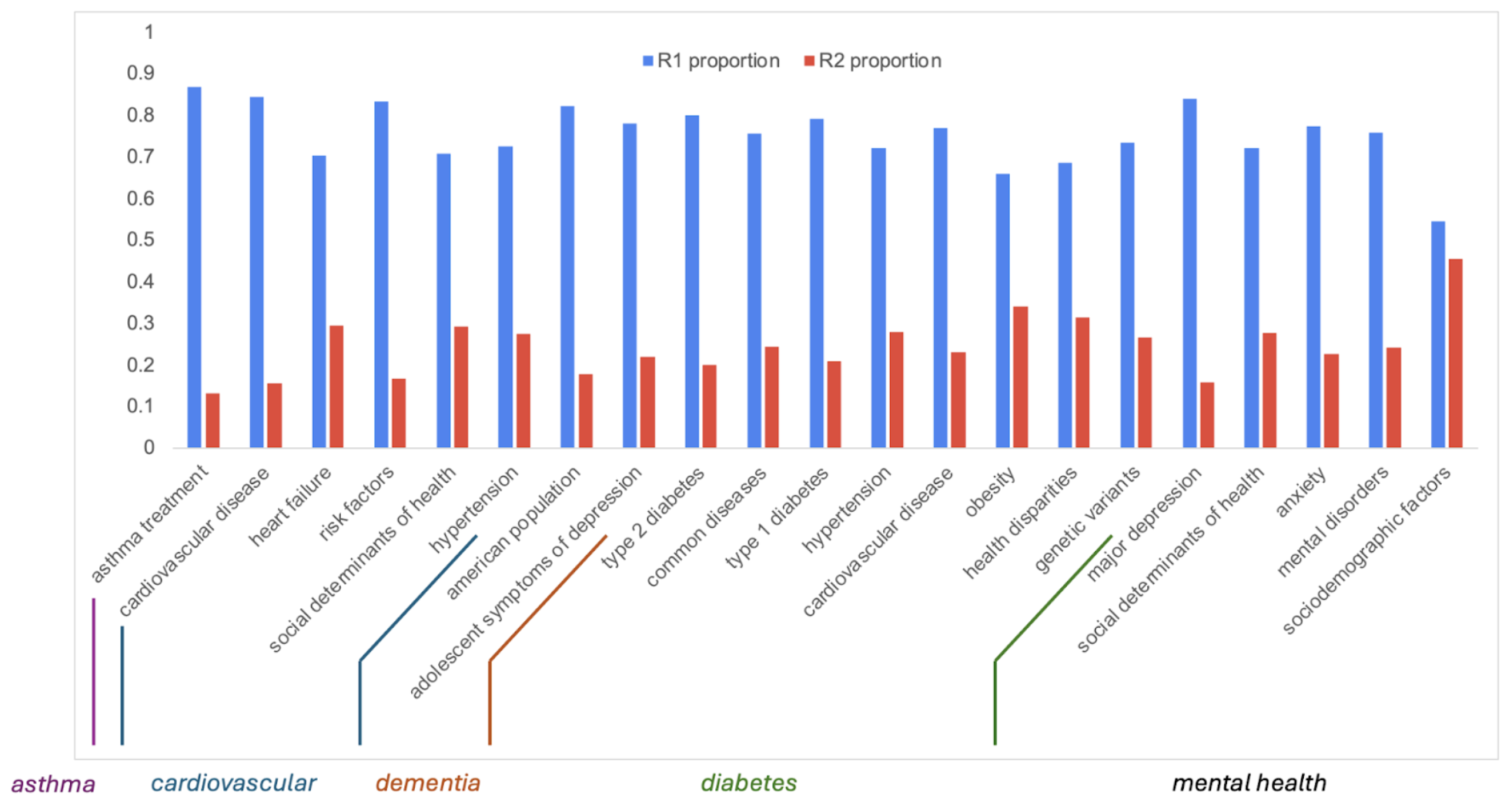

4. Results

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Pipeline Validation and Reproducibility

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braveman, P. Health disparities and health equity: Concepts and measurement. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baciu, A.; Negussie, Y.; Geller, A.; Weinstein, J.N.; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States. The Need to Promote Health Equity. In Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity; National Academies Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. Achieving health equity: From root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet 2007, 370, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrer, L.; Marinetti, C.; Cavaco, Y.; Costongs, C. Advocacy for health equity: A synthesis review. Milbank Q. 2015, 93, 392–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Arkin, E.; Orleans, T.; Proctor, D.; Plough, A. What is health equity? Behav. Sci. Policy 2018, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M. The Concepts and Principles of Equity in Health; WHO, Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 1990.

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. NIMHD Research Framework. 2017. Available online: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/resources/nimhd-research-framework (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- National Institutes of Health. All of Us: About. 2021. Available online: https://allofus.nih.gov/about (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- National Institutes of Health. All of Us: Research Projects Directory. 2024. Available online: https://allofus.nih.gov/protecting-data-and-privacy/research-projects-all-us-data (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Bogard, K.; Murry, V.; Alexander, C. Perspectives on health equity and social determinants of health. In NAM Perspectives; National Academy of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Embrett, M.G.; Randall, G.E. Social determinants of health and health equity policy research: Exploring the use, misuse, and nonuse of policy analysis theory. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 108, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penman-Aguilar, A.; Talih, M.; Huang, D.; Moonesinghe, R.; Bouye, K.; Beckles, G. Measurement of health disparities, health inequities, and social determinants of health to support the advancement of health equity. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2016, 22, S33–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. Classification Methodology: Basic Classification. 2024. Available online: https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/carnegie-classification/classification-methodology/basic-classification/ (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Ostlin, P.; Schrecker, T.; Sadana, R.; Bonnefoy, J.; Gilson, L.; Hertzman, C.; Kelly, M.P.; Kjellstrom, T.; Labonte, R.; Lundberg, O.; et al. Priorities for research to take forward the health equity policy agenda. Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 948–953. [Google Scholar]

- Rasanathan, K.; Diaz, T. Research on health equity in the SDG era: The urgent need for greater focus on implementation. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.B.; Quinn, S.C.; Butler, J.; Fryer, C.S.; Garza, M.A. Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francés, F.; Parra-Casado, D. Participation as a driver of health equity. Gac. Sanit. 2019, 33, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Siiman, L.A.; Rannastu-Avalos, M.; Pöysä-Tarhonen, J.; Häkkinen, P.; Pedaste, M. Opportunities and challenges for AI-assisted qualitative data analysis: An example from collaborative problem-solving discourse data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Technologies and Learning, Porto, Portugal, 28–30 August 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, K.; Shang, R.; Althoff, T.; Wang, C.; Drucker, S.M. How do analysts understand and verify ai-assisted data analyses? In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S.C.; Xiong, A.; Ku, L.W. LLM-in-the-loop: Leveraging large language model for thematic analysis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.15100. [Google Scholar]

- Peasley, D.; Kuplicki, R.; Sen, S.; Paulus, M. Leveraging Large Language Models and Agent-Based Systems for Scientific Data Analysis: Validation Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e68135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.H.; Sulieman, L.; Schlueter, D.J.; Halvorson, A.; Qian, J.; Ratsimbazafy, F.; Loperena, R.; Mayo, K.; Basford, M.; Deflaux, N.; et al. The All of Us Research Program: Data quality, utility, and diversity. Patterns 2022, 3, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The All of Us Research Program Genomics Investigators. Genomic data in the all of us research program. Nature 2024, 627, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.L.; Saseendrakumar, B.R.; Paul, P.; Kim, J.; Bonomi, L.; Kuo, T.T.; Loperena, R.; Ratsimbazafy, F.; Boerwinkle, E.; Cicek, M.; et al. Predictive analytics for glaucoma using data from the all of us research program. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 227, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douville, N.J.; Kertai, M.D.; Sheetz, K.H. Expanding the All of Us Research Platform into the perioperative domain. JAMA Surg. 2025, 160, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.A. Monitoring equity in health and healthcare: A conceptual framework. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2003, 21, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peterson, A.; Charles, V.; Yeung, D.; Coyle, K. The health equity framework: A science-and justice-based model for public health researchers and practitioners. Health Promot. Pract. 2021, 22, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.; Lawrence, K.; Schoenthaler, A.M.; Mann, D. A framework for digital health equity. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Alsentzer, E.; Bates, D.W. Leveraging large language models to foster equity in healthcare. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2024, 31, 2147–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfohl, S.R.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Sayres, R.; Neal, D.; Asiedu, M.; Dieng, A.; Tomasev, N.; Rashid, Q.M.; Azizi, S.; Rostamzadeh, N.; et al. A toolbox for surfacing health equity harms and biases in large language models. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3590–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iloanusi, N.J.; Chun, S.A. AI impact on health equity for marginalized, racial, and ethnic minorities. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Taipei, Taiwan, 11–14 June 2024; pp. 841–848. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltagy, I.; Lo, K.; Cohan, A. SciBERT: A pretrained language model for scientific text. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.10676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Tian, S.; Zhang, J. A PubMedBERT-based classifier with data augmentation strategy for detecting medication mentions in tweets. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.02998. [Google Scholar]

- Groza, T.; Caufield, H.; Gration, D.; Baynam, G.; Haendel, M.A.; Robinson, P.N.; Mungall, C.J.; Reese, J.T. An evaluation of GPT models for phenotype concept recognition. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhizadeh, H.; Yazdani, A.; Zhang, B.; Alvarez, D.V.; Hüser, M.; Vanobberghen, A.; Yang, R.; Li, I.; Walter, A.; Teodoro, D. Large language models struggle to encode medical concepts—A multilingual benchmarking and comparative analysis. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Sun, H.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ran, T.; Jin, X.; Xiao, X.; Lin, Z.; Chen, H.; Niu, Z. An extensive benchmark study on biomedical text generation and mining with ChatGPT. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Hu, Y.; Peng, X.; Xie, Q.; Jin, Q.; Gilson, A.; Singer, M.B.; Ai, X.; Lai, P.T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Benchmarking large language models for biomedical natural language processing applications and recommendations. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Welcome to the OpenAI Developer Platform. 2024. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/overview (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Lewis, S.C.; Zamith, R.; Hermida, A. Content analysis in an era of big data: A hybrid approach to computational and manual methods. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2013, 57, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popping, R. Analyzing open-ended questions by means of text analysis procedures. Bull. Sociol. Methodol./Bull. Méthodol. Sociol. 2015, 128, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Atteveldt, W.; Van der Velden, M.A.; Boukes, M. The validity of sentiment analysis: Comparing manual annotation, crowd-coding, dictionary approaches, and machine learning algorithms. Commun. Methods Meas. 2021, 15, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, N.M.; Chen, M. Rehumanized crowdsourcing: A labeling framework addressing bias and ethics in machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tecimer, K.A.; Aghajani, E.; Bissyandé, T.F.; Klein, J.; Le Traon, Y. Detection and elimination of systematic labeling bias in code reviewer recommendation systems. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Trondheim, Norway, 21–24 June 2021; pp. 222–231. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, L. Beautiful Soup Documentation. 2007. Available online: https://readthedocs.org/projects/beautiful-soup-4/downloads/pdf/latest/ (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Kejriwal, M.; Miranker, D.P. An unsupervised instance matcher for schema-free RDF data. J. Web Semant. 2015, 35, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenreider, O. The unified medical language system (UMLS): Integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D267–D270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, Y. Chord Diagram. 2024. Available online: https://r-graph-gallery.com/chord-diagram.html (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Kohrt, B.A.; Upadhaya, N.; Luitel, N.P.; Maharjan, S.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; MacFarlane, E.K.; Khan, N. Authorship in Global Mental Health Research: Recommendations for Collaborative Approaches to Writing and Publishing. Ann. Glob. Health 2014, 80, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Gordon, S.; Bocking, J.; Ellis, P.; Roper, C.; Liggins, J.; Scholz, B.; Platania-Phung, C. ‘It is always worth the extra effort’: Organizational structures and barriers to collaboration with consumers in mental health research: Perspectives of non-consumer researcher allies. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, R.D.; Parekh, A.; Wainberg, M.L.; Duarte, C.S.; Araya, R.; Oquendo, M.A. Hispanic immigrants in the USA: Social and mental health perspectives. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, F.; Georgakopoulos, P.; Pato, M.T. Challenges and Opportunities to Meet the Mental Health Needs of Underserved and Disenfranchised Populations in the United States. Focus 2020, 18, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearman, A.; Hughes, M.L.; Smith, E.L.; Neupert, S.D. Mental Health Challenges of United States Healthcare Professionals During COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawte, V.; Sheth, A.; Das, A. A survey of hallucination in large foundation models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.05922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jain, S.; Kankanhalli, M. Hallucination is inevitable: An innate limitation of large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. Towards mitigating LLM hallucination via self reflection. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Martino, A.; Iannelli, M.; Truong, C. Knowledge injection to counter large language model (LLM) hallucination. In Proceedings of the European Semantic Web Conference, Crete, Greece, 28 May–1 June 2023; pp. 568–585. [Google Scholar]

| Topic | Search Keyword(s) | # Registered Projects (Deduplicated) | # of Unique Individuals Listed as Team-Members | Average Number of Individuals per Team | % Projects Using Demographic Categories for Study | # of Unique Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | “mental health” | 244 | 365 | 1.82 | 63.52% | 140 |

| Dementia and Alzheimer’s | “dementias;” “alzheimers”, “dementia” | 174 | 246 | 1.80 | 43.68% | 88 |

| Cardiovascular disease | “cardiovascular” | 388 | 588 | 1.86 | 50.00% | 153 |

| Asthma and Pollution | “asthma”, “pollution” | 92 | 128 | 1.67 | 45.65% | 60 |

| Diabetes | “diabetes” | 407 | 600 | 1.91 | 51.84% | 176 |

| Topic | Multi-Institutional Team | Demographic Variable Use | At Least one R2 University |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | 2.173 * (0.935, 5.050) | 3.635 *** (2.086, 6.337) | 1.296 (0.674, 2.493) |

| Dementia and Alzheimer’s | 1.481 (0.449, 4.894) | 1.729 (0.791, 3.778) | 0.564 (0.181, 1.776) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.883 (0.448, 1.743) | 6.846 *** (4.076, 11.498) | 1.746 * (0.983, 3.102) |

| Asthma and Pollution | 0 | 5.500 *** (1.926, 15.706) | 1.735 (0.292, 10.301) |

| Diabetes | 1.495 (0.862, 2.591) | 3.606 *** (2.309, 5.631) | 1.886 ** (1.154, 3.092) |

| Mantel–Haenszel pooled OR | 1.377 (0.821, 2.307) | 4.069 (2.719, 6.087) | 1.522 (0.979, 2.366) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nananukul, N.; Kejriwal, M. Semi-Automatic Extraction and Analysis of Health Equity Covariates in Registered Research Projects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11853. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211853

Nananukul N, Kejriwal M. Semi-Automatic Extraction and Analysis of Health Equity Covariates in Registered Research Projects. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11853. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211853

Chicago/Turabian StyleNananukul, Navapat, and Mayank Kejriwal. 2025. "Semi-Automatic Extraction and Analysis of Health Equity Covariates in Registered Research Projects" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11853. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211853

APA StyleNananukul, N., & Kejriwal, M. (2025). Semi-Automatic Extraction and Analysis of Health Equity Covariates in Registered Research Projects. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11853. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211853