Control Modality and Accuracy on the Trust and Acceptance of Construction Robots

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Characteristics of Construction Industry

1.2. Cobots in Construction Industry

2. Methods

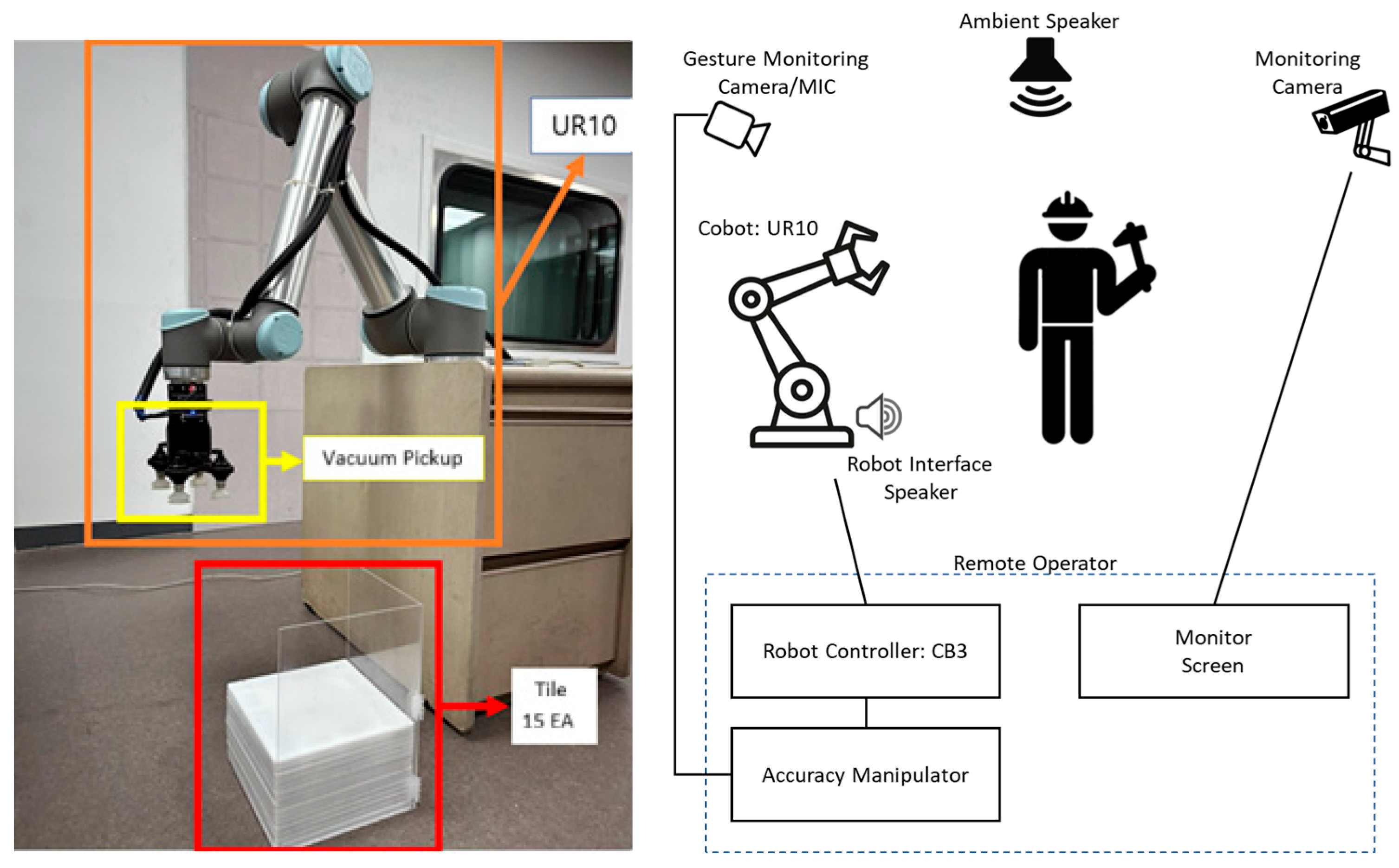

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Independent Variable Manipulations

2.2.1. Modality

2.2.2. Accuracy

2.3. Dependent Variables and Measurements

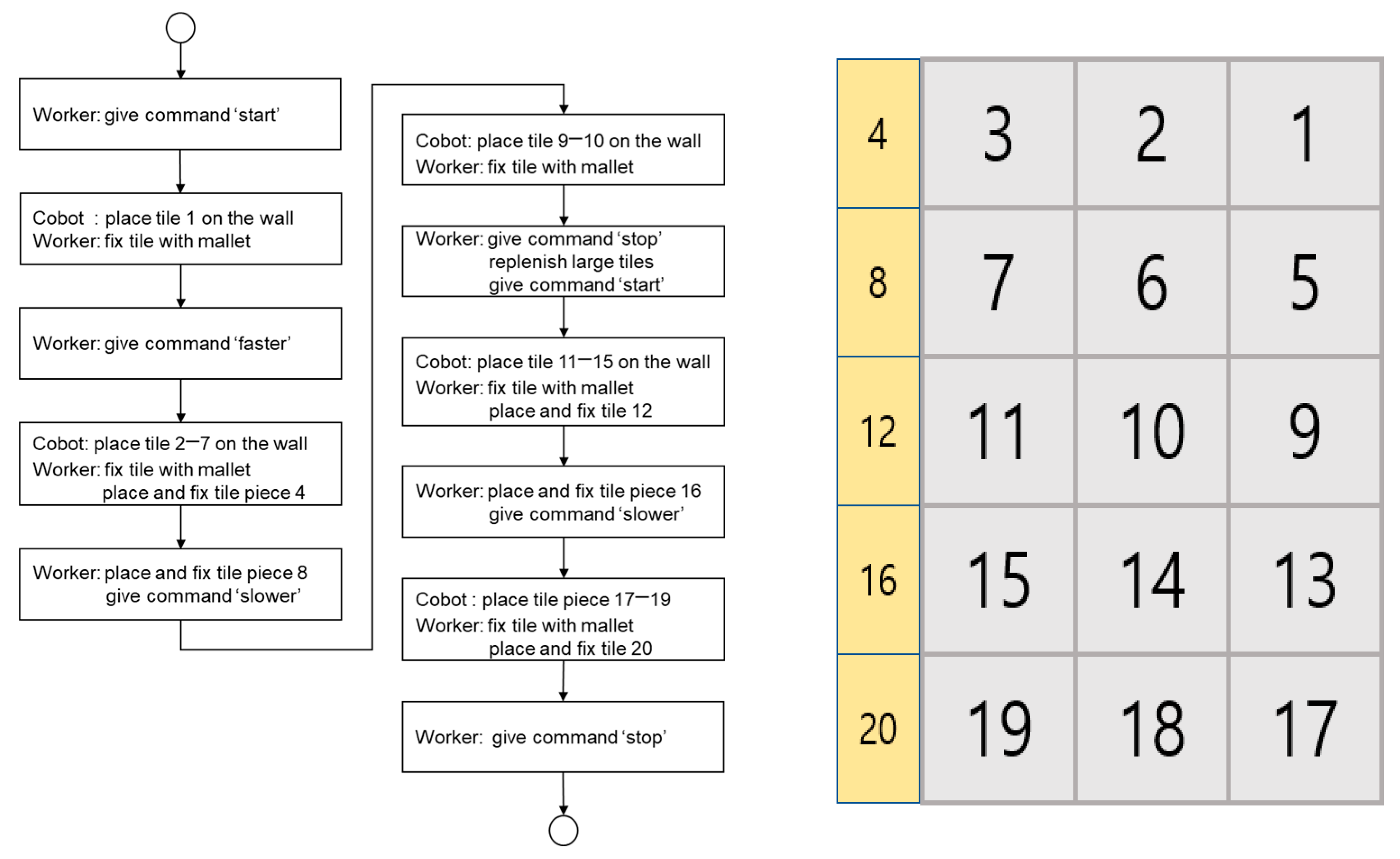

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Procedures

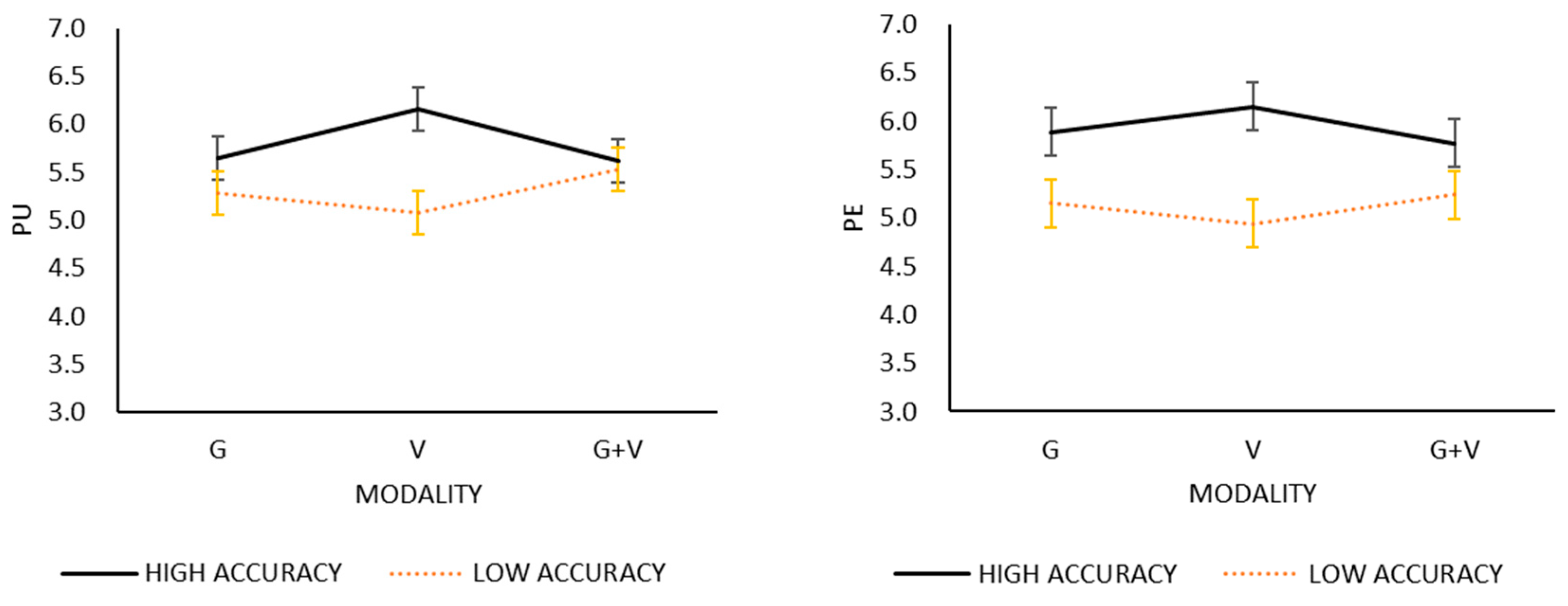

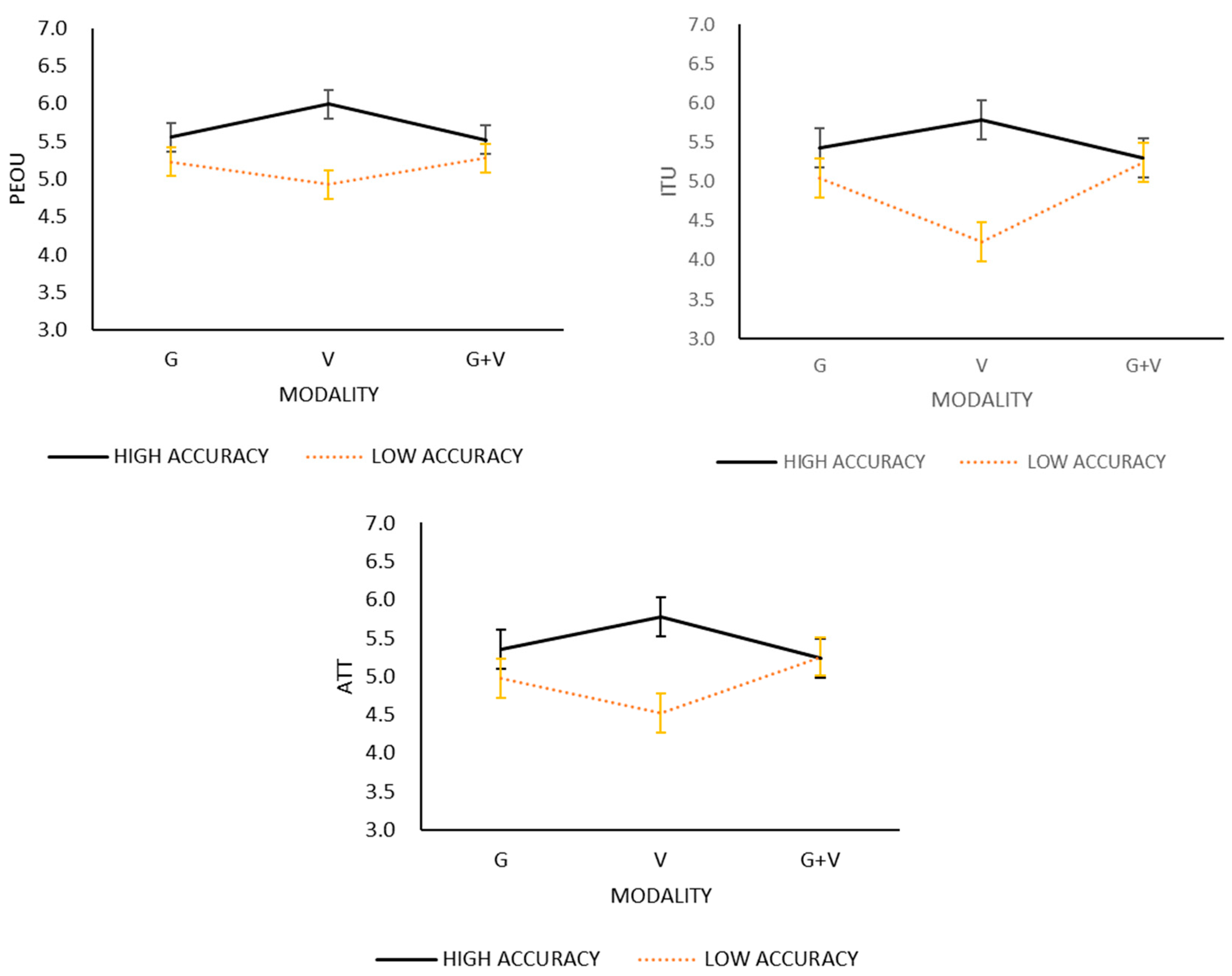

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Inferential Statistics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, D.; Lee, S.; Ku, N.; Lim, C.; Lee, K.-W.; Kim, T.-W.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.H. Development of a mobile robotic system for working in the double-hulled structure of a ship. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2010, 26, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurman, P.R.; D’Andrea, R.; Mountz, M. Coordinating hundreds of cooperative, autonomous vehicles in warehouses. AI Mag. 2008, 29, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, J.; Lien, T.K.; Verl, A. Cooperation of human and machines in assembly lines. CIRP Ann. 2009, 58, 628–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accorsi, R.; Tufano, A.; Gallo, A.; Galizia, F.G.; Cocchi, G.; Ronzoni, M.; Abbate, A.; Manzini, R. An application of collaborative robots in a food production facility. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 38, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geersing, T.H.; Franssen, E.J.F.; Pilesi, F.; Crul, M. Microbiological performance of a robotic system for aseptic compounding of cytostatic drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 130, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.M.D.; Oyedele, L.; Ajayi, A.; Akanbi, L.; Akinade, O.; Bilal, M.; Owolabi, H. Robotics and automated systems in construction: Understanding industry-specific challenges for adoption. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.; Cao, H.-L.; Imrith, E.; Roshandel, N.; Firouzipouyaei, H.; Burkiewicz, A.; Amighi, M.; Menet, S.; Sisavath, D.W.; Paolillo, A.; et al. Sensor-Enabled Safety Systems for Human–Robot Collaboration: A Review. IEEE Sensors J. 2024, 25, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.-J.; Wang, X.; Kamat, V.R.; Menassa, C.C. Human–Robot Collaboration in Construction: Classification and Research Trends. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 03121006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, V.; Pini, F.; Leali, F.; Secchi, C. Survey on human–robot collaboration in industrial settings: Safety, intuitive interfaces and applications. Mechatronics 2018, 55, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Xiong, L.; Zhang, W.; Zuo, Z.; He, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, F. Rebar-tying Robot based on machine vision and coverage path planning. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 182, 104826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, R.; Wu, H.; Pan, J.; Luo, X. Human–robot collaboration for on-site construction. Autom. Constr. 2023, 150, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudah, M.; Al-Naji, A.; Chahl, J. Hand gesture recognition based on computer vision: A review of techniques. J. Imaging 2020, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylari, A.; Ferrer, B.R.; Lastra, J.L.M. Hand Gesture-Based On-Line Programming of Industrial Robot Manipulators. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 17th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Helsinki, Finland, 22–25 July 2019; pp. 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, J.N. Robot-by-voice: Experiments on commanding an industrial robot using the human voice. Ind. Robot 2005, 32, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Feng, Z.; Yang, X.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Q. AMCIU: An Adaptive Multimodal Complementary Intent Understanding Method. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, A.; Ghafoori, S.; Bai, X.; Farhadi, M.; Ostadabbas, S.; Abiri, R. STREAMS: An Assistive Multimodal AI Framework for Empowering Biosignal Based Robotic Controls. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Robotics and Control (AIRC), Savannah, GA, USA, 7–9 May 2025; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, P.A.; Billings, D.R.; Schaefer, K.E.; Chen, J.Y.; De Visser, E.J.; Parasuraman, R. A meta-analysis of factors affecting trust in human-robot interaction. Hum. Factors 2011, 53, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; See, K.A. Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Hum. Factors 2004, 46, 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurtua, I.; Fernandez, I.; Tellaeche, A.; Kildal, J.; Susperregi, L.; Ibarguren, A.; Sierra, B. Natural multimodal communication for human–robot collaboration. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, W.; Panasiuk, J.; Borys, S.; Banach, P. Industrial robot control by means of gestures and voice commands in off-line and on-line mode. Sensors 2020, 20, 6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Lu, S. Review of interfaces for industrial human-robot interaction. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2020, 1, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, M.; Bajcsy, P. Fusion of voice, gesture, and human-computer interface controls for remotely operated robot. In Proceedings of the 2005 7th International Conference on Information Fusion, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25–28 July 2005; p. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.-Y.; Bisantz, A.M.; Drury, C.G. Foundations for an empirically determined scale of trust in automated systems. International journal of cognitive ergonomics. Int. J. Cogn. Ergon. 2000, 4, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Del Pobil, A.P. Users’ attitudes toward service robots in South Korea. Ind. Robot 2013, 40, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, S.C.; de Visser, E.J.; Wiese, E.; Lee, Y.-C. Measurement of Trust in Automation: A Narrative Review and Reference Guide. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 604977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarouchi, P.; Makris, S.; Chryssolouris, G. Human–robot interaction review and challenges on task planning and programming. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2016, 29, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Modality ** | Accuracy | Cronbach’s Alpha | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | V | G + V | High | Low | |||

| TRU * | M (SD) | 5.32 (1.08) | 5.20 (1.10) | 5.36 (0.95) | 5.42 (0.85) | 5.16 (1.13) | 0.918 |

| PE | M (SD) | 5.52 (1.33) | 5.55 (1.41) | 5.51 (1.49) | 5.94 (1.11) | 5.11 (1.30) | 0.957 |

| PEOU | M (SD) | 5.39 (1.16) | 5.46 (1.20) | 5.40 (1.16) | 5.69 (0.88) | 5.14 (1.02) | 0.803 |

| PU | M (SD) | 5.46 (1.20) | 5.62 (1.28) | 5.57 (1.33) | 5.81 (1.07) | 5.29 (0.97) | 0.944 |

| ATT | M (SD) | 5.17 (1.47) | 5.15 (1.42) | 5.24 (1.37) | 5.46 (1.10) | 4.92 (1.14) | 0.941 |

| ITU | M (SD) | 5.24 (1.34) | 5.01 (1.52) | 5.27 (1.39) | 5.51 (1.10) | 4.84 (1.10) | 0.940 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, D.; Lee, D.; Jung, J.H.; Park, T. Control Modality and Accuracy on the Trust and Acceptance of Construction Robots. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11827. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111827

Lee D, Lee D, Jung JH, Park T. Control Modality and Accuracy on the Trust and Acceptance of Construction Robots. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11827. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111827

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Daeguk, Donghun Lee, Jae Hyun Jung, and Taezoon Park. 2025. "Control Modality and Accuracy on the Trust and Acceptance of Construction Robots" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11827. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111827

APA StyleLee, D., Lee, D., Jung, J. H., & Park, T. (2025). Control Modality and Accuracy on the Trust and Acceptance of Construction Robots. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11827. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111827