Dynamic Covalent Bonds in 3D-Printed Polymers: Strategies, Principles, and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism of 3D Printing Technique

2.1. Three-Dimensional Printing Technique Based on Light Irradiation

2.1.1. Stereolithography (SLA)

2.1.2. Liquid Crystal Display (LCD)

2.1.3. Digital Light Processing (DLP)

2.2. Three-Dimensional Printing Technique Based on the Temperature

2.2.1. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)

2.2.2. Direct Ink Writing (DIW)

2.2.3. Selective Laser Sintering (SLS)

3. Reversible Dynamic Covalent Bonding in 3D Printing

3.1. Mechanism of Dynamic Covalent Bonds and Their Influence in 3D Printing

3.2. The Introduction of Dynamic Covalent Bonds in Light-Based 3D Printing

3.2.1. Imine Covalent Bonds

3.2.2. Disulfide

3.2.3. Diel–Alders

3.2.4. Boronate Ester

3.2.5. Alkoxyamine

3.3. The Introduction of Dynamic Covalent Bonds in Thermal 3D Printing

3.3.1. Diel–Alders

3.3.2. Hindered Urea

3.3.3. Transesterification

3.3.4. Imine Bonds

3.3.5. Boronate–Ester Bonds

4. Application

4.1. Cell Culturing

4.2. Wound Dressing

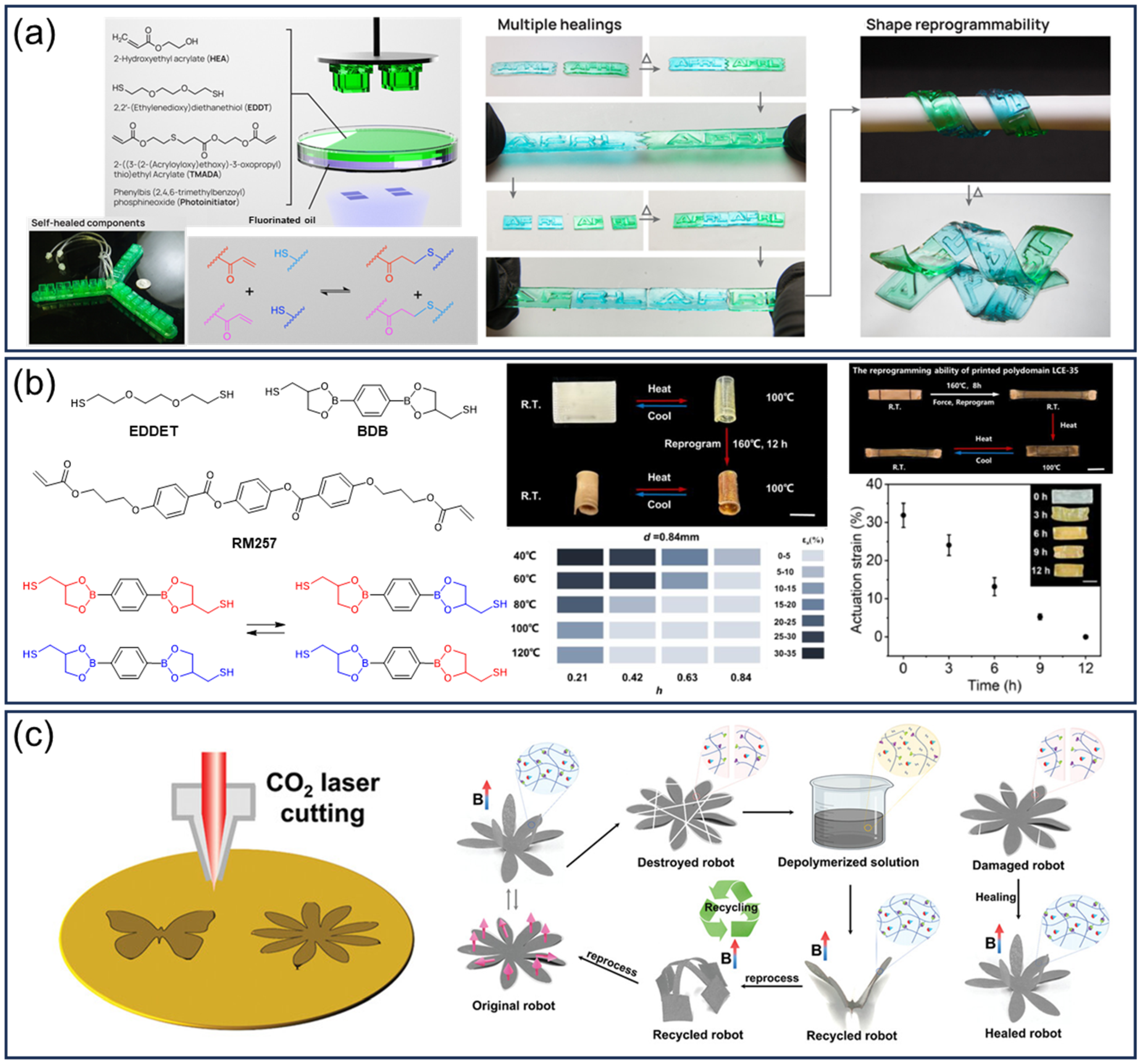

4.3. Soft Robotics

4.4. Tactile Sensor

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kodama, H. Automatic method for fabricating a three-dimensional plastic model with photo-hardening polymer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1981, 52, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. Selective laser sintering: A qualitative and objective approach. JOM 2003, 55, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagac, M.; Hajnys, J.; Ma, Q.-P.; Jancar, L.; Jansa, J.; Stefek, P.; Mesicek, J. A Review of Vat Photopolymerization Technology: Materials, Applications, Challenges, and Future Trends of 3D Printing. Polymers 2021, 13, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladani, L.; Sadeghilaridjani, M. Review of Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing for Metals. Metals 2021, 11, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaee, M.; Crane, N.B. Binder jetting: A review of process, materials, and methods. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkaseer, A.; Chen, K.J.; Janhsen, J.C.; Refle, O.; Hagenmeyer, V.; Scholz, S.G. Material jetting for advanced applications: A state-of-the-art review, gaps and future directions. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 60, 103270. [Google Scholar]

- Dermeik, B.; Travitzky, N. Laminated Object Manufacturing of Ceramic-Based Materials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 2000256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.-G. Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Process: State of the Art. IJPEM-GT 2021, 8, 703–742. [Google Scholar]

- Voet, V.S.D. Closed-Loop Additive Manufacturing: Dynamic Covalent Networks in Vat Photopolymerization. ACS Mater. Au 2023, 3, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Houck, H.A.; Spiegel, C.A.; Selhuber-Unkel, C.; Hou, Y.; Blasco, E. Introducing Dynamic Bonds in Light-based 3D Printing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2300456. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mousawi, A.; Poriel, C.; Dumur, F.; Toufaily, J.; Hamieh, T.; Fouassier, J.P.; Lalevée, J. Zinc Tetraphenylporphyrin as High Performance Visible Light Photoinitiator of Cationic Photosensitive Resins for LED Projector 3D Printing Applications. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lalevée, J.; Zhao, J.; Graff, B.; Stenzel, M.H.; Xiao, P. Dihydroxyanthraquinone derivatives: Natural dyes as blue-light-sensitive versatile photoinitiators of photopolymerization. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 7316–7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, A.; Zanatta, M.; Sans, V.; Roppolo, I. Chemistry in light-induced 3D printing. ChemTexts 2023, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.M.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, S.H. Mass production of 3-D microstructures using projection microstereolithography. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2008, 22, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-W.; Wicker, R.; Lee, S.-H.; Choi, K.-H.; Ha, C.-S.; Chung, I. Fabrication of 3D biocompatible/biodegradable micro-scaffolds using dynamic mask projection microstereolithography. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 5494–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Tang, W.; Li, N.; Yang, J. The recent development of vat photopolymerization: A review. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, A.; Al Rashid, A.; Koç, M. Recent advances in the development of stereolithography-based additive manufacturing processes: A review of applications and challenges. Bioprinting 2024, 43, e00360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H.; Sakthiabirami, K.; Kim, H.-A.; Hosseini Toopghara, S.A.; Jun, M.-J.; Lim, H.-P.; Park, C.; Yun, K.-D.; Park, S.-W. Effects of UV Absorber on Zirconia Fabricated with Digital Light Processing Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2022, 15, 8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, L.M.; Christopher, J.; Watson, B.; Kumar, Y.S.; Copeland, L.; Walker, L.D.; Foylan, S.; Amos, W.B.; Bauer, R.; McConnell, G. Printing, Characterizing, and Assessing Transparent 3D Printed Lenses for Optical Imaging. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2400043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Maier, A.; Mathews, M.; Hu, J.; Zhao, X. Development of open-architecture two-wavelength grayscale digital light processing for advanced vat photopolymerization. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 107, 104818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Naser Shovon, S.M.A.; Chen, X.; Ware, H.O.T. Multi-material vat photopolymerization 3D printing: A review of mechanisms and applications. npj Adv. Manuf. 2024, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, A.; Bom, S.; Martins, A.M.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto, J. Vat-based photopolymerization 3D printing: From materials to topical and transdermal applications. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 19, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturi, M.; Locatelli, E.; Sanz de Leon, A.; Comes Franchini, M.; Molina, S.I. Sustainable approaches in vat photopolymerization: Advancements, limitations, and future opportunities. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 8710–8754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T.; Wu, J. DLP 3D printing of electrically conductive hybrid hydrogels via polymerization-induced phase separation and subsequent in situ assembly of polypyrrole. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 5348–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhand, A.P.; Kirkpatrick, B.E.; Garay-Sarmiento, M.; Nelson, B.R.; Miksch, C.E.; Meurer-Zeman, B.; Zlotnick, H.M.; Mandal, A.; Lee, J.S.; Cione, J.; et al. Digital light processing of photoresponsive and programmable hydrogels. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw9262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Jin, H.; Wu, H.; Jiang, A.; Qiu, B.; Liu, L.; Gao, Q.; Lin, B.; Kong, W.; Chen, S.; et al. Digital light processing printed hydrogel scaffolds with adjustable modulus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.K.; Alahmari, A.; Alkhalefah, H.; Abidi, M.H. Evaluation of zirconia ceramics fabricated through DLP 3d printing process for dental applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Qin, Q.; Wang, J. A Review of Stereolithography: Processes and Systems. Processes 2020, 8, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsari, M.; Chichkov, B.N. Two-photon fabrication. Nat. Photonics 2009, 3, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, K.; Sun, H.-B.; Kawata, S. Improved spatial resolution and surface roughness in photopolymerization-based laser nanowriting. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 071122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.-X.; Tao, X.-T.; Sun, Y.-H.; Xu, G.-B.; Wang, C.-K.; Yang, J.-X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, Y.-Z.; Ren, Y.; Jiang, M.-H. Two new asymmetrical two-photon photopolymerization initiators: Synthesis, characterization and nonlinear optical properties. Opt. Mater. 2005, 27, 1787–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Z.U.; Khalid, M.Y.; Tariq, A.; Hossain, M.; Umer, R. 3D printing of stimuli-responsive hydrogel materials: Literature review and emerging applications. Giant 2024, 17, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kristiansen, P.M.; Islam, A.; Gilchrist, M.; Zhang, N. Advances in precision microfabrication through digital light processing: System development, material and applications. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2023, 18, e2248101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplins, B.W.; Higgins, C.I.; Kolibaba, T.J.; Arp, U.; Miller, C.C.; Poster, D.L.; Zarobila, C.J.; Zong, Y.; Killgore, J.P. Characterizing light engine uniformity and its influence on liquid crystal display based vat photopolymerization printing. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 62, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Borjigin, T.; Schmitt, M.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Xiao, P.; Lalevée, J. High-Performance Photoinitiating Systems for LED-Induced Photopolymerization. Polymers 2023, 15, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Fabbri, P.; Leoni, E.; Mazzanti, F.; Akbari, R.; Antonini, C. Additive manufacturing by digital light processing: A review. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Beluze, L.; Bertsch, A.; Renaud, P. Microstereolithography: A new process to build complex 3D objects. In Design, Test, and Microfabrication of MEMS and MOEMS; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1999; pp. 808–817. [Google Scholar]

- Alparslan, C.; Bayraktar, Ş. Advances in Digital Light Processing (DLP) Bioprinting: A Review of Biomaterials and Its Applications, Innovations, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Polymers 2025, 17, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, J.; Kim, M. Advances in materials and technologies for digital light processing 3D printing. Nano Converg. 2024, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paral, S.K.; Lin, D.-Z.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Lin, S.-C.; Jeng, J.-Y. A Review of Critical Issues in High-Speed Vat Photopolymerization. Polymers 2023, 15, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Guo, A.X.Y.; Cao, S.C.; Liu, N. 3D Printing Soft Matters and Applications: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truby, R.L.; Lewis, J.A. Printing soft matter in three dimensions. Nature 2016, 540, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuli, N.T.; Khatun, S.; Rashid, A.B. Unlocking the future of precision manufacturing: A comprehensive exploration of 3D printing with fiber-reinforced composites in aerospace, automotive, medical, and consumer industries. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Shou, W.; Makatura, L.; Matusik, W.; Fu, K. 3D printing of polymer composites: Materials, processes, and applications. Matter 2022, 5, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, C. Correlating the thermomechanical properties of a novel bio-based epoxy vitrimer with its crosslink density. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 29, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Ying, H.; Zhang, Y.; He, H.; Cheng, J. Reconfigurable Poly(urea-urethane) Thermoset Based on Hindered Urea Bonds with Triple-Shape-Memory Performance. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2019, 220, 1900148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.L.; Fortman, D.J.; De Hoe, G.X.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Dichtel, W.R. Reprocessable Acid-Degradable Polycarbonate Vitrimers. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Yu, K.; Kuang, X.; Mu, X.; Dunn, C.K.; Dunn, M.L.; Wang, T.; Qi, H.J. Recyclable 3D printing of vitrimer epoxy. Mater. Horiz. 2017, 4, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, S.; Manalo, A.; Alajarmeh, O.; Sorbello, C.D.; Weerakoon, S.; Ngo, T.D.; Benmokrane, B. Advancing polymer composites in civil infrastructure through 3D printing. Autom. Constr. 2025, 177, 106311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Mu, H.; Lu, R.; Wu, J.; Xie, T. 3D printing of dynamic covalent polymer network with on-demand geometric and mechanical reprogrammability. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zang, T.; Wu, L.; Fei, G.; Cardon, L.; Xia, H. External field induced high speed sintering of dynamically cross-linked polydimethylsiloxane: Mechanical properties and electromagnetic wave absorption. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 109, 104860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.L.; Dearborn, M.A.; Anderberg, T.M.; Vaidya, K.; Jureller, J.E.; Esser-Kahn, A.P.; Squires, A.H. Polymer Patterning by Laser-Induced Multipoint Initiation of Frontal Polymerization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 17973–17980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejia, E.B.; McDougall, L.; Gonsalves, N.; Darby, D.R.; Greenlee, A.J.; Commisso, A.; Johnson, J.A.; Sottos, N.; Appelhans, L.N.; Cook, A.W.; et al. Real-time process monitoring and automated control for direct ink write 3D printing of frontally polymerizing thermosets. npj Adv. Manuf. 2025, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bai, W.; Zhang, X.; Gao, C.; Zhao, X.; He, Y.; Shang, Y.; Shi, B.; Lu, L.; Chu, D. 3D printing of CNTs-modified continuous carbon fiber composites driven by Joule-heat resin curing. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 216, 110048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, S.; Tokita, E.; Neupane, R.; Ghosh, U.; Elder, B.; Wirthlin, D.; Kong, Y.L. 3D printed nanomaterial-based electronic, biomedical, and bioelectronic devices. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 172001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranzo, D.; Larizza, P.; Filippini, D.; Percoco, G. Extrusion-Based 3D Printing of Microfluidic Devices for Chemical and Biomedical Applications: A Topical Review. Micromachines 2018, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuan-Urquizo, E.; Barocio, E.; Tejada-Ortigoza, V.; Pipes, R.B.; Rodriguez, C.A.; Roman-Flores, A. Characterization of the Mechanical Properties of FFF Structures and Materials: A Review on the Experimental, Computational and Theoretical Approaches. Materials 2019, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zeng, Z.; Peng, B.; Yan, S.; Ke, W. Mechanical Properties Optimization of Poly-Ether-Ether-Ketone via Fused Deposition Modeling. Materials 2018, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gramlich, W.M.; Gardner, D.J. Improving the impact strength of Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) in fused layer modeling (FLM). Polymer 2017, 114, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Feng, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L. Direct ink writing of polymer-based materials—A review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2025, 65, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Xie, H.; Qian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wei, F.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z. Recent Progress on the 3D Printing of Dynamically Cross-Linked Polymers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2307279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Lou, J.; You, Z. Degradable and Fully Recyclable Dynamic Thermoset Elastomer for 3D-Printed Wearable Electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Nian, S.; Rau, D.A.; Huang, B.; Zhu, J.; Freychet, G.; Zhernenkov, M.; Cai, L.-H. 3D Printable Modular Soft Elastomers from Physically Cross-linked Homogeneous Associative Polymers. ACS Polym. Au 2024, 4, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, H.; Deng, S.; Sun, J.; Cheng, F.; Jing, J.; Chen, Y. 3D-Printed Carbon-Based Conformal Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Module for Integrated Electronics. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís Pinargote, N.W.; Smirnov, A.; Peretyagin, N.; Seleznev, A.; Peretyagin, P. Direct Ink Writing Technology (3D Printing) of Graphene-Based Ceramic Nanocomposites: A Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadi, M.A.S.R.; Maguire, A.; Pottackal, N.T.; Thakur, M.S.H.; Ikram, M.M.; Hart, A.J.; Ajayan, P.M.; Rahman, M.M. Direct Ink Writing: A 3D Printing Technology for Diverse Materials. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2108855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabriz, A.G.; Kuofie, H.; Scoble, J.; Boulton, S.; Douroumis, D. Selective Laser Sintering for printing pharmaceutical dosage forms. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. 2023, 86, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekurwale, S.; Karanwad, T.; Banerjee, S. Selective laser sintering (SLS) of 3D printlets using a 3D printer comprised of IR/red-diode laser. Ann. 3D Print. Med. 2022, 6, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, P.; Gharde, S.; Kandasubramanian, B. Thermal Effects in 3D Printed Parts. In 3D Printing in Biomedical Engineering; Singh, S., Prakash, C., Singh, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tel, A.; Kornfellner, E.; Molnár, E.; Johannes, S.; Moscato, F.; Robiony, M. Selective laser sintering at the Point-of-Care 3D printing laboratory in hospitals for cranio-maxillo-facial surgery: A further step into industrial additive manufacturing made available to clinicians. Ann. 3D Print. Med. 2024, 16, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, H.M.; Hamada, A.; Sebaey, T.A.; Abd-Elaziem, W. Selective Laser Sintering of Polymers: Process Parameters, Machine Learning Approaches, and Future Directions. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olakanmi, E.O.; Cochrane, R.F.; Dalgarno, K.W. A review on selective laser sintering/melting (SLS/SLM) of aluminium alloy powders: Processing, microstructure, and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 74, 401–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Shen, W.; Lin, X.; Xie, Y.M. Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) Material Affected by Various Processing Parameters. Polymers 2020, 12, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stichel, T.; Frick, T.; Laumer, T.; Tenner, F.; Hausotte, T.; Merklein, M.; Schmidt, M. A Round Robin study for selective laser sintering of polymers: Back tracing of the pore morphology to the process parameters. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 252, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, C.; Pagnotta, L. Additive manufactured parts produced by selective laser sintering technology: Porosity formation mechanisms. J. Polym. Eng. 2023, 43, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, W.; Winne, J.M.; Du Prez, F.E. Vitrimers: Permanent organic networks with glass-like fluidity. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Dufort, B.; Iten, R.; Tibbitt, M.W. Linking Molecular Behavior to Macroscopic Properties in Ideal Dynamic Covalent Networks. JACS 2020, 142, 15371–15385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtecki, R.J.; Meador, M.A.; Rowan, S.J. Using the dynamic bond to access macroscopically responsive structurally dynamic polymers. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elling, B.R.; Dichtel, W.R. Reprocessable Cross-Linked Polymer Networks: Are Associative Exchange Mechanisms Desirable? ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Hernandez Alvarez, E.I.; Chen, C.; Jing, B.B.; Shen, C.; Braun, P.V.; Schleife, A.; Schroeder, C.M.; Evans, C.M. Control of Lithium Salt Partitioning, Coordination, and Solvation in Vitrimer Electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 8039–8049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohdi, N.; Yang, R. Material Anisotropy in Additively Manufactured Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guessasma, S.; Belhabib, S.; Nouri, H.; Ben Hassana, O. Anisotropic damage inferred to 3D printed polymers using fused deposition modelling and subject to severe compression. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 85, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, B.W.; Maestas, S.S.; Hayden, S.C.; Harrigan, D.J.; Grudt, R.O.; Ostraat, M.L.; Horwath, J.C.; Leontsev, S. Dielectric strength heterogeneity associated with printing orientation in additively manufactured polymer materials. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 22, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somireddy, M.; Czekanski, A. Anisotropic material behavior of 3D printed composite structures—Material extrusion additive manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2020, 195, 108953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemelya, C.; De La Rosa, A.; Torrado, A.R.; Yu, K.; Domanowski, J.; Bonacuse, P.J.; Martin, R.E.; Juhasz, M.; Hurwitz, F.; Wicker, R.B.; et al. Anisotropy of thermal conductivity in 3D printed polymer matrix composites for space based cube satellites. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 16, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, A.; Kalita, N.K.; Adamus, G.; Kowalczuk, M.; Focarete, M.L.; Hakkarainen, M. Bio-based ester- and ester-imine resins for digital light processing 3D printing: The role of the chemical structure on reprocessability and susceptibility to biodegradation under simulated industrial composting conditions. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 219, 113384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova-Pérez, A.; De la Flor, S.; Fernández-Francos, X.; Serra, À.; Roig, A. Biobased Imine Vitrimers Obtained by Photo and Thermal Curing Procedures—Promising Materials for 3D Printing. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 3364–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, A.; Oliva, E.; Sangermano, M.; Hakkarainen, M. Digital Light Processing 3D Printing of Isosorbide- and Vanillin-Based Ester and Ester–Imine Thermosets: Structure–Property Recyclability Relationships. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 14601–14613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stouten, J.; Schnelting, G.H.M.; Hul, J.; Sijstermans, N.; Janssen, K.; Darikwa, T.; Ye, C.; Loos, K.; Voet, V.S.D.; Bernaerts, K.V. Biobased Photopolymer Resin for 3D Printing Containing Dynamic Imine Bonds for Fast Reprocessability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 27110–27119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Phan, T.T.T.; Lee, J.S. Fabrication and Characterization of Self-Healable Polydisulfide Network-Based Composites. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazerozohori, M.; Joohari, S.; Karami, B.; Haghighat, N. Fast and Highly Efficient Solid State Oxidation of Thiols. Molecules 2007, 12, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.R.L.; Franco, M.S.; Mendes, L.D.; Araújo, L.A.; Neto, J.S.S.; Frizon, T.E.A.; dos Santos, V.B.; Carasek, E.; Saba, S.; Rafique, J.; et al. KIO3-catalyzed selective oxidation of thiols to disulfides in water under ambient conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 2175–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.N.; Nguyen, T.D.; Han, J.-H.; Lee, J.S. Synthesis of PDMS Chain Structure with Introduced Dynamic Covalent Bonding for High-Performance Rehealable Tactile Sensor Application. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2400163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, S.; Gao, Y.; Sun, F. Reducing volumetric shrinkage of photopolymerizable materials using reversible disulfide-bond reactions. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 16169–16181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Lee, J.S. Dynamic Bonds in Biopolymers: Enhancing Performance and Properties. Polymers 2025, 17, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yin, J.; Huang, W.; Ye, J.; Deng, H.; Huang, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Xiang, H. UV-induced disulfide metathesis: Strengthening interlayer adhesion and rectifying warped 3D printed materials. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Yin, J.; Lin, G.; Liu, X.; Rong, M.; Zhang, M. Photo-crosslinkable, self-healable and reprocessable rubbers. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olikagu, C.; Khoshsorour, S.; Dulam, S.D.; Yu, H.-S.; Graham, N.A.; Kim, K.-J.; Jeong, B.; Hedrick, J.L.; Bunnag-Stoner, A.; Cheng, K.; et al. Photopolymer Resins from Sulfenyl Chloride Commodity Chemicals for Plastic Optics, Photopatterning and 3D-Printing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2418149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, R.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, W. Self-Healing Polyurethane Elastomers Based on a Disulfide Bond by Digital Light Processing 3D Printing. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 1511–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitosa, L.F.; Campos, R.B.; Richter, W.E. Energetics and electronics of polar Diels–Alder reactions at the atomic level: QTAIM and IQA analyses of complete IRC paths. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2023, 118, 108326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lording, W.J.; Fallon, T.; Sherburn, M.S.; Paddon-Row, M.N. The simplest Diels–Alder reactions are not endo-selective. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 11915–11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, S.; Nam, Y.; Nguyen, M.T.N.; Han, J.-H.; Lee, J.S. Dynamic Covalent Bond-Based Polymer Chains Operating Reversibly with Temperature Changes. Molecules 2024, 29, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Grant, J.C.; Lamey, P.; Joshi-Imre, A.; Lund, B.R.; Smaldone, R.A.; Voit, W. Diels–Alder Reversible Thermoset 3D Printing: Isotropic Thermoset Polymers via Fused Filament Fabrication. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1700318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand-Silva, A.; Cortés-Guzmán, K.P.; Johnson, R.M.; Perera, S.D.; Diwakara, S.D.; Smaldone, R.A. Balancing Self-Healing and Shape Stability in Dynamic Covalent Photoresins for Stereolithography 3D Printing. ACS Macro Lett. 2021, 10, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yu, R.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, W. Four-dimensional printing of shape memory polyurethanes with high strength and recyclability based on Diels-Alder chemistry. Polymer 2020, 200, 122532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T.; Garcia, R.V.; Chau, A.L.; Pitenis, A.A.; Huang, S.; Moran, B.D.; Bailey, S.J.; Hawker, C.J.; Read de Alaniz, J. Radical-Free Digital Light Processing 3D Printing of Hydrogels Using a Photo-Caged Cyclopentadiene Diels–Alder Strategy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e14415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teotonico, J.; Mantione, D.; Ballester-Bayarri, L.; Ximenis, M.; Sardon, H.; Ballard, N.; Ruipérez, F. A combined computational and experimental study of metathesis and nucleophile-mediated exchange mechanisms in boronic ester-containing vitrimers. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Tohyama, Y.; Uchikura, T.; Kikuchi, Y.; Fujii, K.; Uekusa, H.; Iwasawa, N. Control of the reversibility during boronic ester formation: Application to the construction of ferrocene dimers and trimers. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 2370–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, J.M.; Jang, W.-D. Fructose-sensitive thermal transition behaviour of boronic ester-bearing telechelic poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline). Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 3343–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, S.V.; Dodo, O.J.; Konkolewicz, D. Dynamic Bonds: Adaptable Timescales for Responsive Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202206938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacini, A.; Saccani, E.; Sciancalepore, C.; Milanese, D.; Drago, G.; Pedrini, A.; Pinalli, R.; Nicolaÿ, R.; Dalcanale, E. Boronate Esters Dynamic Networks for the Reduction of Mechanical Anisotropy in Vat 3D Printed Manufacts. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 2624–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinawehl, L.; Wolff, R.; Koch, T.; Stampfl, J.; Liska, R.; Baudis, S. Photopolymers Based on Boronic Esters for the Enhanced Degradation of 3D-Printed Scaffolds. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 5758–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.L.; Self, J.L.; Fusi, A.D.; Bates, M.W.; Read de Alaniz, J.; Hawker, C.J.; Bates, C.M.; Sample, C.S. Chemical and Mechanical Tunability of 3D-Printed Dynamic Covalent Networks Based on Boronate Esters. ACS Macro Lett. 2021, 10, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Delaittre, G.; Tsotsalas, M. Covalent Adaptable Networks Based on Dynamic Alkoxyamine Bonds. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2022, 307, 2200178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, B.; Tsotsalas, M.; Becker, M.; Studer, A.; De Cola, L. Dynamic Microcrystal Assembly by Nitroxide Exchange Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6881–6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillaneuf, Y.; Gigmes, D.; Marque, S.R.A.; Tordo, P.; Bertin, D. Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate Using an SG1-Based Alkoxyamine: How the Penultimate Effect Could Lead to Uncontrolled and Unliving Polymerization. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2006, 207, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryn’ova, G.; Lin, C.Y.; Coote, M.L. Which side-reactions compromise nitroxide mediated polymerization? Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 3744–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.B.D.; Vazquez-Martel, C.; Catt, S.O.; Jia, Y.; Tsotsalas, M.; Spiegel, C.A.; Blasco, E. 4D Printing of Adaptable “Living” Materials Based on Alkoxyamine Chemistry. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2315238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Spiegel, C.A.; Diehm, J.; Zimmermann, D.; Huber, B.; Mutlu, H.; Franzreb, M.; Wilhelm, M.; Théato, P.; Blasco, E.; et al. Investigating Dynamic Changes in 3D-Printed Covalent Adaptable Polymer Networks. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2024, 309, 2300438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Leuschel, B.; Nam, N.H.; Guillaneuf, Y.; Gigmes, D.; Clément, J.-L.; Spangenberg, A. Surface Modification of 3D-Printed Micro- and Macro-Structures via In Situ Nitroxide-Mediated Radical Photopolymerization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2312211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belqat, M.; Wu, X.; Morris, J.; Mougin, K.; Petithory, T.; Pieuchot, L.; Guillaneuf, Y.; Gigmes, D.; Clément, J.-L.; Spangenberg, A. Customizable and Reconfigurable Surface Properties of Printed Micro-objects by 3D Direct Laser Writing via Nitroxide Mediated Photopolymerization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2211971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gross, B.; Leuschel, B.; Mougin, K.; Dominici, S.; Gree, S.; Belqat, M.; Tkachenko, V.; Cabannes-Boué, B.; Chemtob, A.; et al. On-Demand Editing of Surface Properties of Microstructures Made by 3D Direct Laser Writing via Photo-Mediated RAFT Polymerization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2109446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenhagen, N.P.; Dadmun, M.D. Bimodal molecular weight samples improve the isotropy of 3D printed polymeric samples. Polymer 2017, 122, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, D.J.; Mackay, M.E. Plasticization of a Diels–Alder Covalent Adaptable Network for Fused Filament Fabrication. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 3335–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, H.; Li, X.; Lu, X.; Xia, H. Selective Laser Sintering 4D Printing of Dynamic Cross-linked Polyurethane Containing Diels–Alder Bonds. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 4035–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Gardea, F.; Sang, Z.; Lee, S.; Pharr, M.; Sukhishvili, S.A. A Tailorable Family of Elastomeric-to-Rigid, 3D Printable, Interbonding Polymer Networks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J. Dynamic urea bond for the design of reversible and self-healing polymers. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzbarth, B.; Eelkema, R. Properties and applications of dynamic covalent ureas. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuo, T.-W.; Hou, J.-T.; Liu, Y.-L. Preparation of polymers possessing dynamic N-hindered amide bonds through ketene-based chemistry for repairable anticorrosion coatings. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 3993–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, S.; Yang, B.; Jin, G.; Zhou, X.; Lin, X.; Wang, R.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, L. Novel Three-Dimensional-Printing Strategy Based on Dynamic Urea Bonds for Isotropy and Mechanical Robustness of Large-Scale Printed Products. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 1994–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ouyang, H.; Sun, S.; Wang, J.; Fei, G.; Xia, H. Selective Laser Sintering for Electrically Conductive Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Composites with Self-Healing Lattice Structures. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 2944–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Gao, F.; Ge, Y.; Guo, X.; Shen, L.; Yang, Y.; Gao, X.; Chen, Y. Tailoring dynamic mechanism of covalent adaptable polyurea networks by varying the category of isocyanates. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 207, 112826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gangarapu, S.; Escorihuela, J.; Fei, G.; Zuilhof, H.; Xia, H. Dynamic covalent urea bonds and their potential for development of self-healing polymer materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 15933–15943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Cheng, J. Hydrolyzable Polyureas Bearing Hindered Urea Bonds. JACS 2014, 136, 16974–16977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.G.; Lee, G.S.; Lee, A. Triazabicyclodecene: A versatile catalyst for polymer synthesis. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 42–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifant’ev, I.E.; Shlyakhtin, A.V.; Tavtorkin, A.N.; Kosarev, M.A.; Gavrilov, D.E.; Komarov, P.D.; Ilyin, S.O.; Karchevsky, S.G.; Ivchenko, P.V. Mechanistic study of transesterification in TBD-catalyzed ring-opening polymerization of methyl ethylene phosphate. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 118, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenen, W.; Poilvet, G.; Sekar, A.; Dul, S.; Hervieu, C.; Gaan, S. Reactive extrusion of vitrimers: A short review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 45, e01638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuna, F.I.; Hoppe, C.E.; Williams, R.J.J. Epoxy vitrimers with a covalently bonded tertiary amine as catalyst of the transesterification reaction. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 113, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Kumar, P.; Sonne, C. Synthesis, properties and biomedical perspective on vitrimers—Challenges & opportunities. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2024, 1, 846–867. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, J.; Shin, J.; Choi, Y.-S.; Hwang, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Han, J.; Park, B.; Lee, W.; Park, S.; Kim, Y.S.; et al. A 4D Printable Shape Memory Vitrimer with Repairability and Recyclability through Network Architecture Tailoring from Commercial Poly(ε-caprolactone). Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna Kar, G.; Lin, X.; Terentjev, E.M. Fused Filament Fabrication of a Dynamically Crosslinked Network Derived from Commodity Thermoplastics. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 4364–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Park, B.; Jo, S.; Seo, J.H.; Lee, W.; Kim, D.-G.; Lee, K.B.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, S. Weldable and Reprocessable Shape Memory Epoxy Vitrimer Enabled by Controlled Formulation for Extrusion-Based 4D Printing Applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24, 2101497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lin, Y.; Ding, Y.; Abdullah, A.M.; Lei, Z.; Han, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, W.; Yu, K. Reshapeable, rehealable and recyclable sensor fabricated by direct ink writing of conductive composites based on covalent adaptable network polymers. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 2022, 4, 015301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, A.; Hidalgo, P.; Ramis, X.; De la Flor, S.; Serra, À. Vitrimeric Epoxy-Amine Polyimine Networks Based on a Renewable Vanillin Derivative. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 9341–9350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, M.; Guth, L.; Déjean, S.; Paniagua, C.; Nottelet, B. Dynamic and Degradable Imine-Based Networks for 3D-Printing of Soft Elastomeric Self-Healable Devices. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2300066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Arifuzzaman, M.; Gilmer, D.B.; Li, B.; Wilt, J.K.; Lara-Curzio, E.; Saito, T. Closed-loop additive manufacturing of upcycled commodity plastic through dynamic cross-linking. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Xia, H.; Wu, J.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, X. Dynamic Boronate Ester Chemistry Facilitating 3D Printing Interlayer Adhesion and Modular 4D Printing of Polylactic Acid. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2503682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terriac, L.; Helesbeux, J.-J.; Maugars, Y.; Guicheux, J.; Tibbitt, M.W.; Delplace, V. Boronate Ester Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications: Challenges and Opportunities. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 6674–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.J.R.; Gaspar, V.M.; Lavrador, P.; Mano, J.F. Double network laminarin-boronic/alginate dynamic bioink for 3D bioprinting cell-laden constructs. Biofabrication 2021, 13, 035045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Kalow, J.A. Internal and External Catalysis in Boronic Ester Networks. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Li, D.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Lin, Z.; Cao, X.; Dong, H. Assembling Microgels via Dynamic Cross-Linking Reaction Improves Printability, Microporosity, Tissue-Adhesion, and Self-Healing of Microgel Bioink for Extrusion Bioprinting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 15653–15666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliari, S.R.; Burdick, J.A. A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.K.; Park, D.J.; Skousen, J.L.; Hess-Dunning, A.E.; Tyler, D.J.; Rowan, S.J.; Weder, C.; Capadona, J.R. Mechanically-compliant intracortical implants reduce the neuroinflammatory response. J. Neural Eng. 2014, 11, 056014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A.; Li, H.; Lewittes, D.M.; Dong, B.; Liu, W.; Shu, X.; Sun, C.; Zhang, H.F. Fabricating customized hydrogel contact lens. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, A.; Bennion, D.; Horne, R.; Hansen, M.R.; Guymon, C.A. Photografted Zwitterionic Hydrogel Coating Durability for Reduced Foreign Body Response to Cochlear Implants. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 3124–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, S.M.; Lou, J.; Lindsay, C.D.; Navarro, R.S.; Cai, B.; Brunel, L.G.; Westerfield, A.D.; Xia, Y.; Heilshorn, S.C. 3D bioprinting of dynamic hydrogel bioinks enabled by small molecule modulators. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakoli, S.; Krishnan, N.; Mokhtari, H.; Oommen, O.P.; Varghese, O.P. Fine-tuning Dynamic Cross–linking for Enhanced 3D Bioprinting of Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2307040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-P.; Davis, R.; Wang, T.-C.; Deo, K.A.; Cai, K.X.; Alge, D.L.; Lele, T.P.; Gaharwar, A.K. Dynamically Cross-Linked Granular Hydrogels for 3D Printing and Therapeutic Delivery. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 3683–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, K.; Ji, S.m.; Kummara, M.R.; Han, S.S. Recent Progress on Hyaluronan-Based Products for Wound Healing Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, B.; Papageorgiou, D.G.; Silva, R.; Zehnder, T.; Gul-E-Noor, F.; Bertmer, M.; Kaschta, J.; Chrissafis, K.; Detsch, R.; Boccaccini, A.R. Fabrication of alginate–gelatin crosslinked hydrogel microcapsules and evaluation of the microstructure and physico-chemical properties. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 1470–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, T.; Xu, J. Advances in Functional Hydrogel Wound Dressings: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, B.; An, Z.; Zheng, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, T.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. MMP-Responsive Nanoparticle-Loaded, Injectable, Adhesive, Self-Healing Hydrogel Wound Dressing Based on Dynamic Covalent Bonds. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 5769–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Xie, W.; Cui, Z.; Huang, J.; Cao, H.; Li, Y. 3D printed alginate/gelatin-based porous hydrogel scaffolds to improve diabetic wound healing. Giant 2023, 16, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyazbakhsh, F.; Khayat, M.J.; Leu, M.C. 3D-Printed Gelatin-Alginate Hydrogel Dressings for Burn Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Study. IJB 2022, 8, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A.; Kaur, T.; Joshi, A.; Gugulothu, S.B.; Choudhury, S.; Singh, N. Light-Mediated 3D Printing of Micro-Pyramid-Decorated Tailorable Wound Dressings with Endogenous Growth Factor Sequestration for Improved Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monavari, M.; Homaeigohar, S.; Medhekar, R.; Nawaz, Q.; Monavari, M.; Zheng, K.; Boccaccini, A.R. A 3D-Printed Wound-Healing Material Composed of Alginate Dialdehyde–Gelatin Incorporating Astaxanthin and Borate Bioactive Glass Microparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 50626–50637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonardd, S.; Nandi, M.; Hernández García, J.I.; Maiti, B.; Abramov, A.; Díaz Díaz, D. Self-Healing Polymeric Soft Actuators. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 736–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhang, X. Self-healing polymers for soft actuators and robots. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 3137–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Shi, Q.; Li, H.; Jabour, J.; Yang, H.; Dunn, M.L.; Wang, T.; Qi, H.J. Interfacial welding of dynamic covalent network polymers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2016, 94, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairkkar, S.; Pansare, A.V.; Pansare, S.V.; Chhatre, S.Y.; Sakamoto, J.; Barbezat, M.; Terrasi, G.P.; Patil, V.R.; Nagarkar, A.A.; Naito, M. Adhesive-less bonding of incompatible thermosetting materials. RSC Appl. Polym. 2024, 3, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam-Neeb, A.A.; Kaiser, J.M.; Hubbard, A.M.; Street, D.P.; Dickerson, M.B.; Nepal, D.; Baldwin, L.A. Self-healing and polymer welding of soft and stiff epoxy thermosets via silanolates. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 3068–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liang, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, E.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ji, Y. Rejuvenating liquid crystal elastomers for self-growth. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, Y.; Ji, Y. Locally controllable magnetic soft actuators with reprogrammable contraction-derived motions. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, E.C.; Kotikian, A.; Li, S.; Aizenberg, J.; Lewis, J.A. 3D Printable and Reconfigurable Liquid Crystal Elastomers with Light-Induced Shape Memory via Dynamic Bond Exchange. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1905682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, E.F.; Wanasinghe, S.V.; Flynn, A.E.; Dodo, O.J.; Sparks, J.L.; Baldwin, L.A.; Tabor, C.E.; Durstock, M.F.; Konkolewicz, D.; Thrasher, C.J. 3D-Printed Self-Healing Elastomers for Modular Soft Robotics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 28870–28877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Li, T.; Yuan, L.; Yang, J.; Xiao, R.; Wang, Z. 3D printing of reprogrammable liquid crystal elastomers with exchangeable boronic ester bonds. Giant 2024, 20, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Hou, Y.; Xia, N.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, J.; Jin, D.; Zhang, L. Fully Recyclable, Healable, Soft, and Stretchable Dynamic Polymers for Magnetic Soft Robots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2300888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannsfeld, S.C.B.; Tee, B.C.K.; Stoltenberg, R.M.; Chen, C.V.H.H.; Barman, S.; Muir, B.V.O.; Sokolov, A.N.; Reese, C.; Bao, Z. Highly sensitive flexible pressure sensors with microstructured rubber dielectric layers. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Lee, Y.; Kwon, J.; Kim, S.; Ryu, G.; Yun, S.; Baek, S.; Ko, H.; Jung, S. 3D active-matrix multimodal sensor arrays for independent detection of pressure and temperature. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pei, Z.; Chai, B.; Jiang, P.; Ma, L.; Zhu, L.; Huang, X. Engineering the Dielectric Constants of Polymers: From Molecular to Mesoscopic Scales. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2308670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, C.; Hu, J.; Pan, M.; Qiu, W.; Guo, Y.; Sun, K.; Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Peng, J.; et al. Wide-Range Linear Iontronic Pressure Sensor with Two-Scale Random Microstructured Film for Underwater Detection. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 43923–43933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Jones, J.; Ballinger, N.; Sadaba, N.; Lopez de Pariza, X.; Yao, Y.; Craig, S.L.; Sardon, H.; Nelson, A. 3D printed modular piezoionic sensors using dynamic covalent bonds. RSC Appl. Polym. 2024, 2, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, L. A 3D printable, highly stretchable, self-healing hydrogel-based sensor based on polyvinyl alcohol/sodium tetraborate/sodium alginate for human motion monitoring. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 219, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tao, X.; Yu, R.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, W. Self-healing, mechanically robust, 3D printable ionogel for highly sensitive and long-term reliable ionotronics. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 12005–12015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, M.T.N.; Lee, J.S. Dynamic Covalent Bonds in 3D-Printed Polymers: Strategies, Principles, and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11755. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111755

Nguyen TD, Nguyen MTN, Lee JS. Dynamic Covalent Bonds in 3D-Printed Polymers: Strategies, Principles, and Applications. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11755. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111755

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Trong Danh, My Thi Ngoc Nguyen, and Jun Seop Lee. 2025. "Dynamic Covalent Bonds in 3D-Printed Polymers: Strategies, Principles, and Applications" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11755. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111755

APA StyleNguyen, T. D., Nguyen, M. T. N., & Lee, J. S. (2025). Dynamic Covalent Bonds in 3D-Printed Polymers: Strategies, Principles, and Applications. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11755. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111755