Abstract

The paper presents the issue of acquired and secondary auditory processing disorder (APD) in children and adolescents in the Polish population. The authors analyzed a group of individuals with APD and younger children who were at risk based on a detailed interview with parents. A comparison of developmental factors showed several similarities between the risk and diagnosed APD groups, including abnormal muscle tone (64.29% vs. 33.33%), ear diseases (42.86% vs. 57.58%), and complicated delivery (32.14% vs. 39.39%). In terms of school factors, the most significant difficulties were associated with poor concentration (78.57% vs. 54.55%), irregularities in mastering phonology related to writing (67.86% vs. 75.76%), and reading (64.29% vs. 78.79%), as well as problems with understanding speech-in-noise perception (60.71% vs. 57.58%). A comparison of children at risk of APD and those with a confirmed diagnosis revealed multiple similarities. The results were visualized using Pareto charts to highlight the most influential factors. The results indicate the need to disseminate screening that could show the APD risk group. Therefore, the diagnostic process could be performed more quickly in such individuals. Based on recurring developmental factors, the Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ) was developed as a non-clinical screening tool to identify children potentially at risk of APD. The RAQ demonstrated a moderate discriminative potential (AUC = 0.68; sensitivity = 75%; specificity = 68%) and may support early referral for diagnostic evaluation. The results highlight the value of systematic screening to accelerate diagnosis and intervention, especially in populations where access to formal assessment is limited.

1. Introduction

Auditory processing disorder (APD), also known as central auditory processing disorder (CAPD), is associated with abnormalities at higher auditory functions, as discussed in studies from the fields of medicine, speech therapy (speech and language therapy for hearing), and pedagogy [1,2,3,4,5]. Due to the nature of auditory processing and the role of the auditory cortex, it is natural to link its dysfunction to other complex processes, including cognitive functions, as well as the occurrence of auditory processing disorders in children with learning disabilities [6,7,8]. However, Maggu [9] emphasized a significantly weaker relationship between cognitive abilities and auditory processing in adult patients. Both recent and earlier research on APD [1,9,10,11] has highlighted the need to distinguish auditory processing disorders from language impairments of different etiology. This distinction is often challenging due to the necessity of adapting test procedures or incorporating non-linguistic assessments into the diagnostic process [12,13].

In APD, children and adolescents experience a set of auditory processing difficulties that significantly impact their academic performance and daily communication [4,5,6,14,15]. The auditory cortex processes sounds, primarily speech, while minimizing interference with concurrent cognitive and motor tasks. Therefore, efficient auditory processing requires attention, automation, and appropriate cortical synchronization. If this process is impaired, children may present with delayed language acquisition, difficulties in understanding speech in noisy environments, and learning disabilities [16].

APD is not caused by peripheral hearing loss but rather by dysfunction in the central auditory nervous system (CANS). As a result, children with APD often pass standard audiometric tests but continue to struggle with auditory perception and comprehension. These difficulties frequently translate into poor academic achievement, attention deficits, and problems in social interactions [3,4,17].

Research on the etiology of APD identifies three main causes, i.e., developmental, acquired, and secondary APD [3,18]. Developmental APD is associated with neurological immaturity, delayed myelination, and deficits in neuronal connectivity, without a clear external cause. In contrast, acquired APD results from identifiable risk factors such as perinatal complications, prematurity, brain injuries, infections, or exposure to ototoxic agents [5,19]. Additionally, increasing exposure to digitally processed sounds from electronic devices in early childhood has been linked to auditory deprivation and delayed auditory system maturation [20,21].

The symptoms of APD often overlap with other developmental disorders, such as specific learning disorders (SLDs), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and language impairment. Therefore, differential diagnosis is essential and should include standard audiological testing, speech-language assessments, and neuropsychological evaluation. In addition, it should also cover objective tests, including electrophysiological tests, such as frequency following response [13,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. In practice, however, conducting differential diagnosis significantly prolongs the diagnostic process. Although these mechanisms are well described in previous research, they provide the necessary clinical context for the RAQ tool developed in this study.

The aim of this study was to analyze the relationship between developmental and school-related risk factors in Polish children diagnosed with APD and those at risk of developing the disorder. By identifying common characteristics in both groups, this study aimed to improve early identification strategies and highlight the importance of preventive interventions. While APD has been extensively studied internationally, its combined developmental and school-related risk factors remain underexplored in the Polish population. This study addresses this gap by comparing children at risk of APD with those formally diagnosed. We hypothesized that both groups would exhibit similar developmental risk factors, with school-related difficulties more pronounced in the diagnosed group. Based on recurring developmental patterns observed during the study, we developed the Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ) as a preliminary, non-clinical screening tool to support early identification and referral for APD assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study aimed to identify risk factors in two groups: (1) children diagnosed with APD and (2) children at risk of APD. Next, we analyzed the relationship between these factors and both groups.

The study was conducted as a cross-sectional observational study and included 60 children (aged 6–12 years). The participants were divided into two groups:

- APD-risk group (n = 28): children who presented with symptoms suggestive of APD but had not received a formal diagnosis.

- APD-diagnosed group (n = 32): children with a confirmed APD diagnosis based on audiological and speech-language assessments.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study groups, including the number of children and their mean age in the APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups. The predominance of boys in both groups reflects the fact that APD symptoms are more frequently reported in males than in females, as supported by previous studies [2,3]. Moreover, the clinical recruitment setting may have further influenced the gender distribution in the sample.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the study groups.

All participants were recruited from speech therapy and audiology clinics in the Silesian region, Poland, with parental consent obtained prior to participation. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was based on anonymized, retrospective clinical interview data and did not involve experimental intervention. The Committee on Ethics of Research Involving Human Participants at the Silesian University of Technology issued a positive opinion, Resolution No. 5/2025, dated 26 September 2025, confirming that the study meets ethical standards.

The participants were eligible for inclusion if they had normal peripheral hearing (confirmed by pure-tone audiometry), were aged 6–12 years, and had no history of intellectual disability or neurological disorders. Children in the APD-risk group were included based on clinical suspicion of APD, whereas children in the APD-diagnosed group had a confirmed diagnosis.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: sensorineural or conductive hearing loss, neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., autism, ADHD, dyslexia) without coexisting APD, and a history of severe neurological diseases such as epilepsy, cerebral palsy, or traumatic brain injury.

Children were referred for diagnosis due to difficulties in acquiring school skills based on auditory-related activities. According to the standardized Polish diagnostic procedures, Wechsler intelligence tests were conducted to assess cognitive abilities [3]. Subsequently, physiological hearing tests were performed, including impedance audiometry and pure-tone audiometry, confirming normal hearing thresholds. Additionally, speech-language and pedagogical assessments were conducted.

Higher auditory functions were evaluated using standardized tests, including the Duration Pattern Test (DPT), the Frequency Pattern Test (FPT), and the Dichotic Digit Test (DDT) [3,30,31]. The final diagnosis of APD was established by a specialist in audiology and phoniatrics based on the findings.

The diagnosis and management of APD vary across countries, with differences in diagnostic criteria and the availability of standardized tests. In Poland, there is an increasing need for early screening tools that can help identify children at risk of APD before significant school-related difficulties occur. This tool aims to facilitate early intervention and support educational planning for children at risk.

2.2. Data Collection

The structured parental interviews were conducted by the authors as part of routine clinical procedures. The thematic scope of the interview was informed by existing literature on developmental and medical risk factors [3,32]. The interview included questions about prenatal and perinatal history, such as pregnancy complications and birth conditions, as well as medical history, including recurrent ear infections, respiratory diseases, and allergies. Additionally, parents provided information on developmental milestones, including speech and language development and motor skills. The interview also addressed school performance, focusing on reading, writing, concentration, and the ability to understand speech in noise. The interviews were conducted by two specialists (a neurologist and a speech-language therapist specializing in hearing disorders).

2.3. Developmental Factors

Developmental risk factors are given in Table 2 based on the clinical expertise of the study team and previous research [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. These indicators are consistent with functional impairment observed in children with auditory processing issues and were used to create the RAQ.

Table 2.

Prevalence of developmental risk factors in APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups.

2.4. School-Related Factors

School difficulties were identified based on clinical APD profiles [29,32,41] and expert assessment. The analyzed factors are included in Table 3.

Table 3.

School-related difficulties in children with APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups.

2.5. Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ): Construction and Preliminary Validation

The RAQ consists of 9 binary (yes/no) items, each assigned a weight of 1 or 2 points based on their frequency in the clinical sample and their relevance as reported in the literature (e.g., abnormal muscle tone, middle ear disease, recurrent infections) [33,34,36,37,39,40,42]. The maximum total score is 14 points. One item concerning habitual mouth breathing was included based on clinical observations, due to its association with other factors. A complete mapping of RAQ items to developmental risk categories is given in Appendix B.

To evaluate its initial utility, the RAQ was administered to parents of the original 60 participants after structured interviews (APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups). A reference group of 30 children without diagnosed APD confirmed by the Frequency Pattern Test (FPT), the Duration Pattern Test (DPT), and the Dichotic Digit Test (DDT) was later added exclusively for comparative analysis. The aim was to assess internal consistency and the tool’s screening potential. Performance metrics, including the ROC curve, sensitivity, specificity, and the Youden Index, are given in Section 3.4.

The Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ) was not part of the original study design. It emerged as an exploratory outcome from the statistical analysis of developmental risk indicators in children diagnosed with APD and those identified as at risk. The repeated presence of specific developmental factors suggested the potential for a simple screening checklist to support early identification of such cases.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis identified significant relationships between children at risk and those diagnosed with APD, considering developmental and school factors. Statistical significance levels are marked as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. We verified the normality of data distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which showed a deviation from the normal distribution. Then, we employed a Pareto chart to identify key development and school factors. Kendall rank correlation coefficient and the Chi-square test (with Cramér’s V as the effect size measure) were used to assess and confirm the relationship between factors in each group. The analyses were performed in the JASP computing environment [43]. Additionally, RAQ scores were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test and post hoc Mann–Whitney tests to examine differences across diagnostic groups. Effect sizes were reported as epsilon-squared (ε2) for Kruskal–Wallis tests and r for Mann–Whitney tests.

3. Results

The statistical analysis showed several similarities between the APD-risk group and APD-diagnosed group in terms of developmental and school-related factors. The results are presented in tabular and graphical forms using Pareto charts, which illustrate the most significant contributing factors.

3.1. Developmental Factors

The frequency of developmental factors in both groups is shown in Table 4. The most commonly reported risk factors among APD-risk group children were abnormal muscle tone (64.29%), ear diseases (42.86%), recurrent upper respiratory tract infections (35.71%), and high-risk childbirth (32.14%). In the APD-diagnosed group, the most frequent factors included ear diseases (57.58%), high-risk childbirth (39.39%), abnormal muscle tone (33.33%), and allergy or asthma (24.24%).

Table 4.

Frequency of developmental factors in APD-risk group and APD-diagnosed group.

The differences in developmental factors between the two groups suggest that while many children at risk of APD share early-life vulnerabilities with those formally diagnosed, these factors appear to exert a greater impact in the latter group. The high prevalence of recurrent ear infections (57.58%) and perinatal complications (39.39%) in the diagnosed group supports the existing evidence that early auditory disruptions may interfere with central auditory pathway maturation. This highlights the importance of proactive monitoring in at-risk children, even before a formal diagnosis.

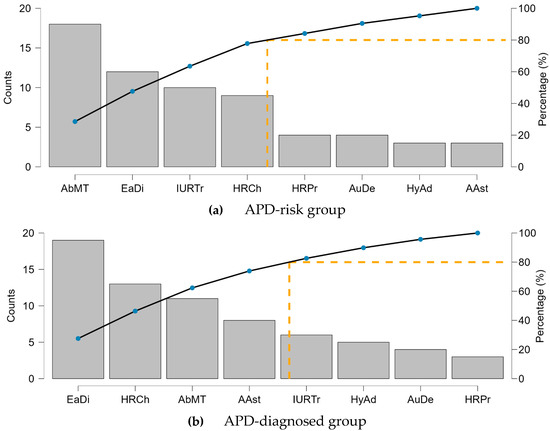

The Pareto charts in Figure 1 illustrate the cumulative impact of these developmental factors in both groups. In the APD-risk group, the steepest slopes were observed for abnormal muscle tone, ear diseases, and upper respiratory tract infections. In the APD-diagnosed group, the dominant risk factors included ear diseases, high-risk childbirth, and abnormal muscle tone.

Figure 1.

Pareto charts of developmental factors for the APD-risk group (a) and (b) APD-diagnosed group (b).

3.2. School-Related Factors

The occurrence of school difficulties in both groups is summarized in Table 5. Among APD-risk group children, the most significant school-related problems were poor concentration (78.57%), phonological abnormalities in writing (67.86%) and reading (64.29%), and difficulties understanding speech in noise (60.71%). Similarly, in the APD-diagnosed group, the most frequent school-related issues included phonological abnormalities in reading (78.79%) and writing (75.76%), understanding speech in noise (57.58%), and concentration difficulties (54.55%).

Table 5.

Frequency of school-related difficulties in APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups.

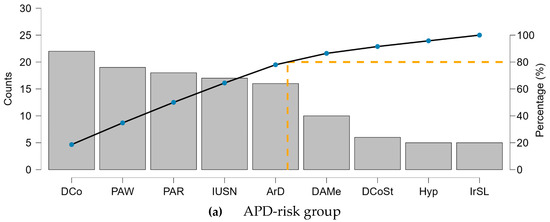

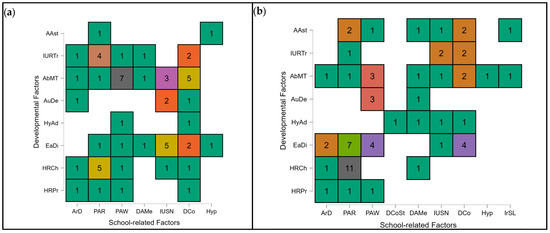

The Pareto charts in Figure 2 demonstrate that phonological processing difficulties (reading and writing) were the most prevalent school-related issues in both groups.

Figure 2.

Pareto charts of school factors for the APD-risk group (a) and the APD-diagnosed group (b).

3.3. Association Between Developmental and School Difficulties

The Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficient showed (Table 6) no significant relationship between developmental and school-related factors in the APD-risk group (tau-b = 0.043, p = 0.677). However, a statistically significant correlation was found in the APD-diagnosed group (tau-b = 0.417, p < 0.001).

Table 6.

The relationship between developmental and school factors based on Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient.

The Chi-square test did not show significant differences between the two groups (Χ2 = 7.656; df = 7; p = 0.364; Cramér’s V = 0.14), suggesting that developmental risk factors were similarly distributed. These findings indicate that while developmental factors were present in both groups, their impact on school-related difficulties was more pronounced in children with a confirmed APD diagnosis. The multidimensional relationships between developmental and school-related factors are visualized in Appendix C, where heatmaps show their co-occurrence patterns across the APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups.

3.4. Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ)

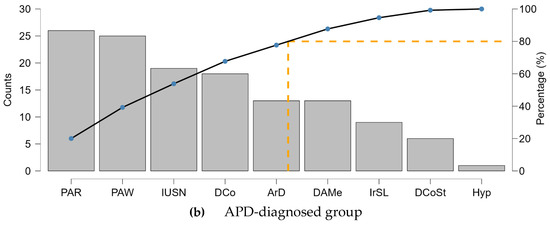

RAQ scores significantly differed across the three groups (APD-risk, APD-diagnosed, reference) (Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.0019, ε2 = 0.117). Post hoc Mann–Whitney analysis revealed significant differences between the reference group and both APD groups, but not between the APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups (r for APD-diagnosed vs. APD-risk: 0.131; r for APD-diagnosed vs. reference: 0.319; r for APD-risk vs. reference: 0.435). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis yielded an AUC of 0.68, with a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 68% at an optimal cut-off score of 4 points (Youden Index). These findings are illustrated in Figure 3, which presents (a) the ROC curve demonstrating the discriminative ability of the RAQ, and (b) the distribution of RAQ scores across diagnostic groups, with detailed descriptive statistics provided in Table 7.

Figure 3.

(a) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve showing the discriminative ability of the RAQ to differentiate children with APD diagnosis from the reference group. (b) Distribution of RAQ scores across diagnostic groups (APD-risk, APD-diagnosed, and reference group).

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics for total RAQ scores in children diagnosed with APD, at risk of APD, and in the reference group.

While these values suggest moderate discriminative ability, the RAQ is not intended for diagnostic use. Instead, it is a preliminary screening tool to support early referral and observation. Given that development and evaluation were performed on overlapping samples, the results should be interpreted with caution and validated in future research using independent cohorts.

4. Discussion

The study demonstrated that both the APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups shared several developmental risk factors, including abnormal muscle tone, recurrent ear infections, and high-risk childbirth. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the negative impact of neuromuscular and middle-ear conditions on central auditory processing [3,4,5,32,39]. Notably, middle ear diseases were the most prevalent in the APD-diagnosed group (57.58%), reinforcing the hypothesis that early auditory disruptions may contribute to long-term processing deficits. Similar observations have been reported in other populations, including studies from the United States and the UK [2,3]. Environmental factors such as excessive exposure to digitally processed sounds were also noted (14.29% in the risk group), indicating a potential modern contributor to auditory deprivation—an area that warrants further research.

Although developmental risk factors were similarly distributed, their impact on school-related functioning was more pronounced in the APD-diagnosed group. This supports the hypothesis that early vulnerabilities may not manifest fully until later stages of cognitive and auditory development. In both groups, children struggled with phonological processing, especially in reading and writing, as well as with concentration and understanding speech in noise. These challenges align with prior findings linking APD to literacy difficulties, attention deficits, and impaired auditory discrimination [6,24,32].

The high rate of concentration difficulties (78.57% in the risk group, 54.55% in the diagnosed group) suggests overlap between APD and attentional disorders such as ADHD, though these conditions remain distinct. Difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments, reported by over half of both groups, highlights the need for educational accommodations such as classroom FM systems, background noise reduction, and structured auditory training.

These findings emphasize the importance of early screening and intervention, even in children who have not yet received a formal APD diagnosis. A multidisciplinary approach involving audiologists, speech-language therapists, and educators is essential. Intervention programs should focus on phonological awareness, auditory memory, and noise-reduction strategies. While many affected children may benefit from such support, individualized intervention plans remain critical for effective outcomes.

The Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ), developed in response to recurring developmental patterns, offers a potential early screening tool for identifying children at risk of APD. However, as it was developed post hoc and validated on overlapping samples, its screening performance must be confirmed in future research using larger and independent cohorts. The RAQ should be seen as a support tool for early referral, not as a diagnostic instrument.

Overall, the study underscores the significance of early developmental risk factors in APD and the need for systematic school-based support. Further research should continue to explore how these factors evolve and interact over time, ideally through longitudinal and cross-cultural studies using validated tools like the RAQ.

Future work should evaluate the combined use of the RAQ with electrophysiological and neuroimaging measures, such as auditory brainstem response (ABR), frequency-following response (FFR), and, where feasible, fMRI, to improve diagnostic accuracy. It should be noted that such advanced procedures are not part of the standard surdologopedic diagnostic protocol in Poland. The present dataset was derived from routine medical documentation, which included only the basic audiological and higher auditory function tests used for APD diagnosis and referral to therapy. These methods remain beyond standard public diagnostic practice, but will be considered in future, grant-funded studies to better explore the neural mechanisms underlying APD.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides valuable insights, it has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample size (n = 60) was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Larger-scale studies are needed to confirm these results across more diverse populations.

Second, the study relied on parental interviews, which may introduce recall bias regarding early developmental risk factors. The use of objective medical records and standardized diagnostic tools would strengthen data reliability in future research.

Third, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to track the progression of APD symptoms and changes in risk factors over time. Longitudinal studies are essential to understand developmental trajectories and the impact of early interventions.

Another limitation is the lack of control for potential confounding variables, such as parental education, socioeconomic status, and early digital device exposure. These factors may significantly influence both APD development and school-related difficulties and should be considered in future studies.

Additionally, the RAQ was developed post hoc based on the same clinical dataset used for item selection, increasing the risk of overfitting. Its screening validity should be confirmed through independent samples and larger-scale validation studies.

While the study analyzed developmental and school-related factors, their potential interactions and causal relationships remain underexplored. Future research should examine these links in more depth and assess the predictive value of specific risk indicators.

Finally, cross-cultural comparisons could determine whether similar APD patterns occur in other populations, supporting the broader applicability of findings and tools like the RAQ.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that developmental risk factors such as abnormal muscle tone, recurrent ear infections, and high-risk childbirth are common in both the APD-risk group and the APD-diagnosed group children. However, their impact on academic performance, phonological processing, and attention difficulties becomes more pronounced in children with confirmed APD.

The results emphasize the importance of early identification and preventive interventions, particularly in children with a history of frequent ear infections, speech delays, or learning difficulties. Given the significant overlap between APD and school-related challenges, a multidisciplinary approach involving audiologists, speech therapists, and educators is essential to support affected children.

Future research should focus on longitudinal tracking of APD risk factors, neuroimaging studies, which could provide further insight into the structural and functional differences in auditory processing in children with APD, and comparative analyses with other neurodevelopmental disorders to refine diagnostic and intervention strategies.

The results of this study confirm our initial hypothesis, i.e., developmental risk factors are similarly distributed in both groups, but their impact on school-related difficulties is significantly greater in children with APD. This emphasizes the need for early intervention, even in children who have not received a formal diagnosis yet. Future research should include longitudinal studies to determine whether early intervention in at-risk children can prevent or mitigate school-related difficulties in APD, improving long-term educational outcomes. The findings of this study emphasize the importance of early screening for APD risk factors. The Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ) offers a structured, non-clinical method for identifying children at increased risk of auditory processing difficulties. Further studies are needed to validate its screening performance and determine its potential role within broader APD assessment frameworks.

Since the tool was developed post hoc based on the observed patterns in the same clinical dataset, and then tested on that dataset along with an additional reference group of 30 healthy children, there is a potential risk of overfitting. The control group was recruited after the initial data analysis, specifically to evaluate the questionnaire’s preliminary screening utility. While this design allowed for the identification of relevant risk indicators and initial performance testing, it does not provide an independent validation.

Given the exploratory nature of the RAQ, these results should be considered preliminary. Future research should involve larger, independent cohorts to verify the screening accuracy and generalizability of the questionnaire in broader populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.; methodology, N.M. and M.K.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, N.M. and M.K.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, N.M., M.K. and A.B.; supervision, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant number 2024/08/X/HS2/01396, and co-financed by statutory research of the Silesian University of Technology, number 07/010/BK_25/1047. The APC was funded by the Silesian University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Silesian University of Technology (Resolution No. 5/2025, approved on 26 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent for participation was provided by the participants’ parents or legal guardians.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The research was conducted in cooperation with Strefa Dobrej Mowy i Muzyki sp. z o.o., Rataja 8/17, Katowice, Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Risk Assessment Questionnaire (14 Points)

The Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ) for developmental factors is designed to identify children who may be at increased risk of future school-related difficulties. The questions were developed based on research findings and caregiver observations of developmental irregularities, including prenatal, perinatal, and early childhood factors. Persistent abnormalities in the reception and processing of auditory information during the critical period when a child acquires speech and language skills are likely to hinder the proper development of higher auditory functions. This, in turn, may lead to learning difficulties. The diagnosis of higher auditory function disorders, including auditory processing disorder (APD), is often preceded by persistent academic challenges.

The aim of the authors in developing the questionnaire is to enable early preventive interventions, including timely initiation of audiological-speech therapy. Such therapy is intended to mitigate the effects of the identified developmental risk factors, stimulate auditory functions, and prevent auditory deprivation of verbal sounds from early childhood. Each “YES” response is assigned a specific number of points according to the weighting of the corresponding question.

Interpretation: A total score of 4 points or more may indicate an increased risk of auditory processing difficulties and should prompt further observation or referral for specialist assessment.

- Has the child been diagnosed with or has there been a suspicion of abnormal muscle tone distribution (e.g., hypotonia, hypertonia, postural abnormalities, sensory integration disorders)? (2 points)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

- Has the child experienced middle ear infections at least twice within a single year (or once per year, but recurring across multiple years)? (2 points)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

- Has the child had frequent upper respiratory tract infections (five or more per year) during a period when they were unable to blow their nose independently? (2 points)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

- Does the child predominantly breathe through the mouth during the day and/or night? (2 points)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

- Were there any pregnancy-related complications (e.g., medications taken during pregnancy, high-risk pregnancy, premature birth)? (1 point)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

- Were there any birth-related complications (e.g., prolonged labor, umbilical cord wrapping, non-standard delivery method, post-term birth with oligohydramnios or meconium-stained amniotic fluid)? (2 points)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

- Has the child been diagnosed with adenoid hypertrophy? (1 point)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

- Has the child been diagnosed with allergic rhinitis or asthma? (1 point)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

- Does the child frequently (more than 2 h per day in total) use sound-producing toys or listen to stories/music via smartphone, tablet, or TV either actively or as background noise? (1 point)

- □

- YES

- □

- NO

Appendix B

The table below presents the mapping of each item in the Risk Assessment Questionnaire (RAQ) to the corresponding developmental risk factor identified in the literature and clinical practice. This structure reflects the rationale behind item selection and scoring in the RAQ. Some items, such as mouth breathing, overlap with multiple categories and were included based on their observed clinical relevance.

Table A1.

Mapping of RAQ items to developmental risk factors.

Table A1.

Mapping of RAQ items to developmental risk factors.

| RAQ Item No. | Corresponding Risk Factor | Code |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abnormal muscle tone | AbMT |

| 2 | Middle and inner ear diseases | EaDi |

| 3 | Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections | IURTr |

| 4 | Mouth breathing (linked to AbMT and IURTr) | — |

| 5 | High-risk pregnancy HRPr | HRPr |

| 6 | High-risk childbirth | HRCh |

| 7 | Hypertrophy of adenoids | HyAd |

| 8 | Allergy or asthma | AAst |

| 9 | Auditory deprivation | AuDe |

Appendix C

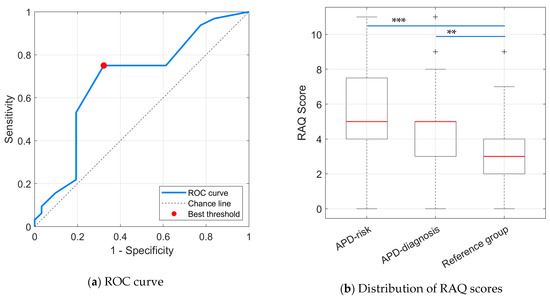

The following heatmaps illustrate the co-occurrence patterns between developmental and school-related risk factors in children from the APD-risk and APD-diagnosed groups (Figure A1). Each cell represents the number of children exhibiting both developmental and school-related risk factors. Color intensity reflects the strength of co-occurrence, with warmer colors indicating higher frequencies. The visualization shows that middle ear diseases (EaDi), high-risk childbirth (HRCh), and abnormal muscle tone (AbMT) most frequently co-occur with phonological deficits in reading (PAR) and writing (PAW), as well as concentration difficulties (DCo).

Figure A1.

Heatmap illustrating the co-occurrence between developmental and school-related factors in children diagnosed with auditory processing disorder (APD). APD-risk group (a) and the APD-diagnosed group (b).

References

- Dillon, H.; Cameron, S. Separating the Causes of Listening Difficulties in Children. Ear Hear. 2021, 42, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadou, V.V.; Chermak, G.D.; Bamiou, D.E.; Musiek, F.E. Gold Standard, Evidence-Based Approach to Diagnosing APD. Hear. J. 2019, 72, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majak, J.; Senderski, A.; Wiskirska-Woźnica, B.; Śliwińska-Kowalska, M. Auditory Processing Disorders in Children—Diagnosis and Management. Pol. Przegląd Otorynolaryngologiczny 2023, 12, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczylas, A.; Cieśla, K.; Kurkowski, Z.M.; Czajka, N.; Skarżyński, H. Diagnosis and Therapy of Individuals with Central Auditory Processing Disorders in Poland (PL: Diagnoza i terapia osób z centralnymi zaburzeniami przetwarzania słuchowego w Polsce). Nowa Audiofonologia 2012, 1, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczylas, A.; Lewandowska, M.; Pluta, A.; Kurkowski, Z.M.; Skarżyński, H. Central Auditory Disorders—Diagnostic Guidelines and Therapy Proposals (PL: Ośrodkowe zaburzenia słuchu—Wskazówki diagnostyczne i propozycje terapii). Nowa Audiofonologia 2012, 1, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenneman, L.; Cash, E.; Chermak, G.D.; Guenette, L.; Masters, G.; Musiek, F.E.; Brown, M.; Ceruti, J.; Fitzegerald, K.; Geissler, K.; et al. The Relationship between Central Auditory Processing, Language, and Cognition in Children Being Evaluated for Central Auditory Processing Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2017, 28, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, P.; Monteiro de Castro Silva, I.; Neiva, E.R.; Tristão, R.M. Auditory Processing Disorder Evaluations and Cognitive Profiles of Children with Specific Learning Disorder. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 2019, 4, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Kothari, S.; Rohith, V.S.; Kumar, H.S.; Jain, C. The Relationship between Auditory and Cognitive Processing Abilities in Children with Specific Learning Disorders. Am. J. Audiol. 2024, 33, 824–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggu, A.R.; Sharma, B. Relationship between Cognitive Abilities and Basic Auditory Processing in Young Adults. Am. J. Audiol. 2024, 33, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, P.; Bishop, D. Auditory Processing Disorder in Relation to Developmental Disorders of Language, Communication and Attention: A Review and Critique. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2009, 44, 440–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismen, K.; Emanuel, D.C. Auditory Processing Disorder: Protocols and Controversy. Am. J. Audiol. 2023, 32, 614–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmed, A.U.; Ahmmed, A.A.; Bath, J.R.; Ferguson, M.A.; Plack, C.J.; Moore, D.R. Assessment of Children with Suspected Auditory Processing Disorder: A Factor Analysis Study. Ear Hear. 2014, 35, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidvar, S.; Duquette-Laplante, F.; Bursch, C.; Jutras, B.; Koravand, A. Assessing Auditory Processing in Children with Listening Difficulties: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Central Auditory Processing Disorders: The Role of Audiologist; ASHA: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Senderski, A. Diagnosis and Management of Auditory Processing Disorders in Children (PL: Rozpoznawanie i postępowanie w zaburzeniach przetwarzania słuchowego u dzieci). Otorynolaryngologia 2014, 13, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, S.; Mealings, K.T.; Chong-White, N.; Young, T.; Dillon, H. The Development of the Listening in Spatialized Noise–Universal Test (LiSN-U) and Preliminary Evaluation in English-Speaking Listeners. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 59, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristidou, I.L.; Hohman, M.H. Central Auditory Processing Disorder; StatPearls: Petersburg, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- British Society of Audiology. Position Statement and Practice Guidance: Auditory Processing Disorder (APD); British Society of Audiology: Reading, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.thebsa.org.uk/resources/position-statement-and-practice-guidance-apd-2018/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Tomlin, D.; Rance, G. Maturation of the Central Auditory Nervous System in Children with Auditory Processing Disorder. Semin. Hear. 2016, 37, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard Blythe, S. Genius of Natural Childhood (Early Years); Hawthorn Press: Gloucestershire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk, I.; Olempska-Wysocka, M. Sensory Difficulties and the Role of a Student: A Case Study of Children with Special Educational Needs (PL: Trudności sensoryczne a pełnienie roli ucznia na przykładzie dzieci ze specjalnymi potrzebami edukacyjnymi). Forum Pedagog. 2017, 2, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, A.T.; Enayati, Z. Lack of a Coherent Theory Limits the Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of the (Central) Auditory Processing Disorder: A Theoretical and Clinical Perspective. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 30, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, A.; McPherson, B. Central Auditory Processing: A Brief Introduction to the Processes Involved and the Non-Verbal Behavioural Test That Can Be Used with Polish-Speaking Patients. Otolaryngologia 2007, 6, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gitto, M.; Motta, N.; Aldè, M.; Zanetti, D.; Di Berardino, F. Auditory Processing Disorders: Navigating the Diagnostic Maze of Central Hearing Losses. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggu, A.R.; Overath, T. An Objective Approach toward Understanding Auditory Processing Disorder. Am. J. Audiol. 2021, 30, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polewczyk, I. Auditory Perception—Subject of Research and Diagnostic Tools (PL: Percepcja słuchowa—Przedmiot badań i narzędzia diagnozy). In Profilaktyka Logopedyczna w Praktyce Edukacyjnej; Węsierska, K., Moćko, N., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 161–186. [Google Scholar]

- Polewczyk, I. Diagnosing and Stimulating the Development of Auditory Perception in Preschool Children (PL: Diagnozowanie i Stymulowanie Rozwoju Percepcji Słuchowej Dzieci w Wieku Przedszkolnym); ŻAK Wydawnictwo Akademickie: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Senderski, A.; Iwanicka-Pronicka, K.; Majak, J.; Walkowiak, M.; Dajos, K. Normative Values of Screening Tests of Higher Auditory Functions on the APD-Medical Diagnostic-Therapeutic Platform (PL: Wartości normatywne przesiewowych testów wyższych funkcji słuchowych platformy diagnostyczno-terapeutycznej APD-Medical). Otorynolaryngologia 2016, 15, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, M.; Ganc, M.; Włodarczyk, E.; Senderski, A.; McPherson, D.L.; Bednarek, D. Central Auditory Processes Predict Reading Abilities of Children with Developmental Dyslexia. J. Hear. Sci. 2013, 3, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, M.; Milner, R.; Ganc, M.; Włodarczyk, E.; Dołżycka, J.; Skarżyński, H. Development of Central Auditory Processes in Polish Children and Adolescents Aged from 7 to 16 Years. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 1789–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarzynski, P.H.; Czajka, N.; Zdanowicz, R.; Kolodziejak, A.; Bukato, E.; Talarek, M.; Pankowska, Z.; Skarzynski, H. Normative Values for Tests of Central Auditory Processing Disorder in Children Aged from 6 to 12 Years Old. J. Commun. Disord. 2024, 109, 106426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.A. Understanding Auditory Processing Disorder: A Narrative Review. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaman, G.; Poduval, J.D. Impact of Adenoidectomy on Middle Ear Function in Children between 5–12 Years of Age with Chronic Adenoiditis. Int. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 7, 1611–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, W.A. Mouth Breathing and Speech Disorders: A Multidisciplinary Evaluation Based on the Etiology. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2022, 14 (Suppl. S1), S911–S916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, R.X.Y.; Tay, M.J.Y.; Ooi, D.S.Q.; Siah, K.T.H.; Tham, E.H.; Shek, L.P.; Meaney, M.J.; Broekman, B.F.P.; Loo, E.X.L. Understanding the Link between Allergy and Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Current Review of Factors and Mechanisms. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 603571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasunla, A.J.; Ijitola, J.O.; Nwaorgu, O.G. Tympanometric Patterns of Children with Allergic Rhinitis Treated at a Tertiary Health Institution. OTO Open 2017, 1, 2473974X17742648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarghazalani, B.; Farahani, F.; Emadi, M.; Hosseni Dastgerdi, Z. Auditory Processing Abilities in Children with Chronic Otitis Media with Effusion. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2016, 136, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, F.J.; Said, S.M.; Kasho, H.H.; Jamil, B.J. The Effect of Adenoid Size on Tympanometric Finding in Children. Zanco J. Med. Sci. 2016, 20, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.S.; Lima, T.R.C.M.; Sena Junior, L.C.O.; Figueiredo, E.R.P.; Nascimento, C.E.J.; Nascimento, R.S.; Taguchi, C.K. Auditory Function and Central Auditory Processing Screening in Children and Adolescents with Asthma and Rhinitis: Preliminary Study. Res. Soc. Dev. 2025, 14, e0914147908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, K.A.; Naina, P.; Sebastian, S.; Varghese, A.M. A Case-Control Study on the Association between Endoscopic ACE Grade of Adenoid Hypertrophy and Hearing Loss in Children and Its Impact on Speech and Language Development. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 71, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśniok, E.; Ławecka, M. Stimulation of Auditory Functions in Central Auditory Processing Disorders (PL: Stymulacja funkcji słuchowych w zaburzeniach centralnych procesów przetwarzania). Forum Logop. 2016, 24, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kręcichwost, M.; Moćko, N.; Ławecka, M.; Miodońska, Z.; Sage, A.; Badura, P. Exploring Developmental Factors Related to Auditory Processing Disorder in Children. In Information Technology in Biomedicine; ITIB 2022; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Pietka, E., Badura, P., Kawa, J., Wieclawek, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1429, pp. 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.18.3) [Computer software]; JASP Team: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).