Predicting the Cooling Rate in Steel-Part Heat Treatment via Random Forests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Random Forest

2.1. Bootstrap Sample

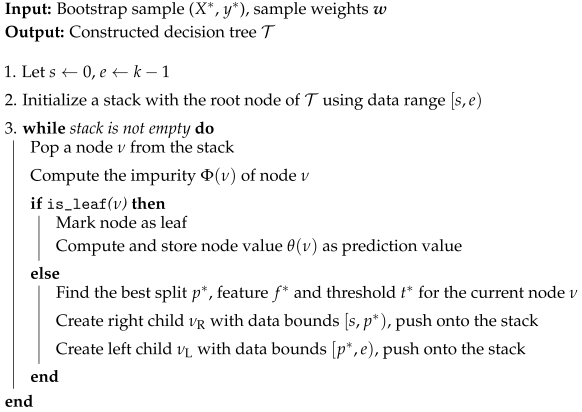

2.2. Tree Construction

| Algorithm 1: Binary decision tree construction. |

|

2.3. Prediction

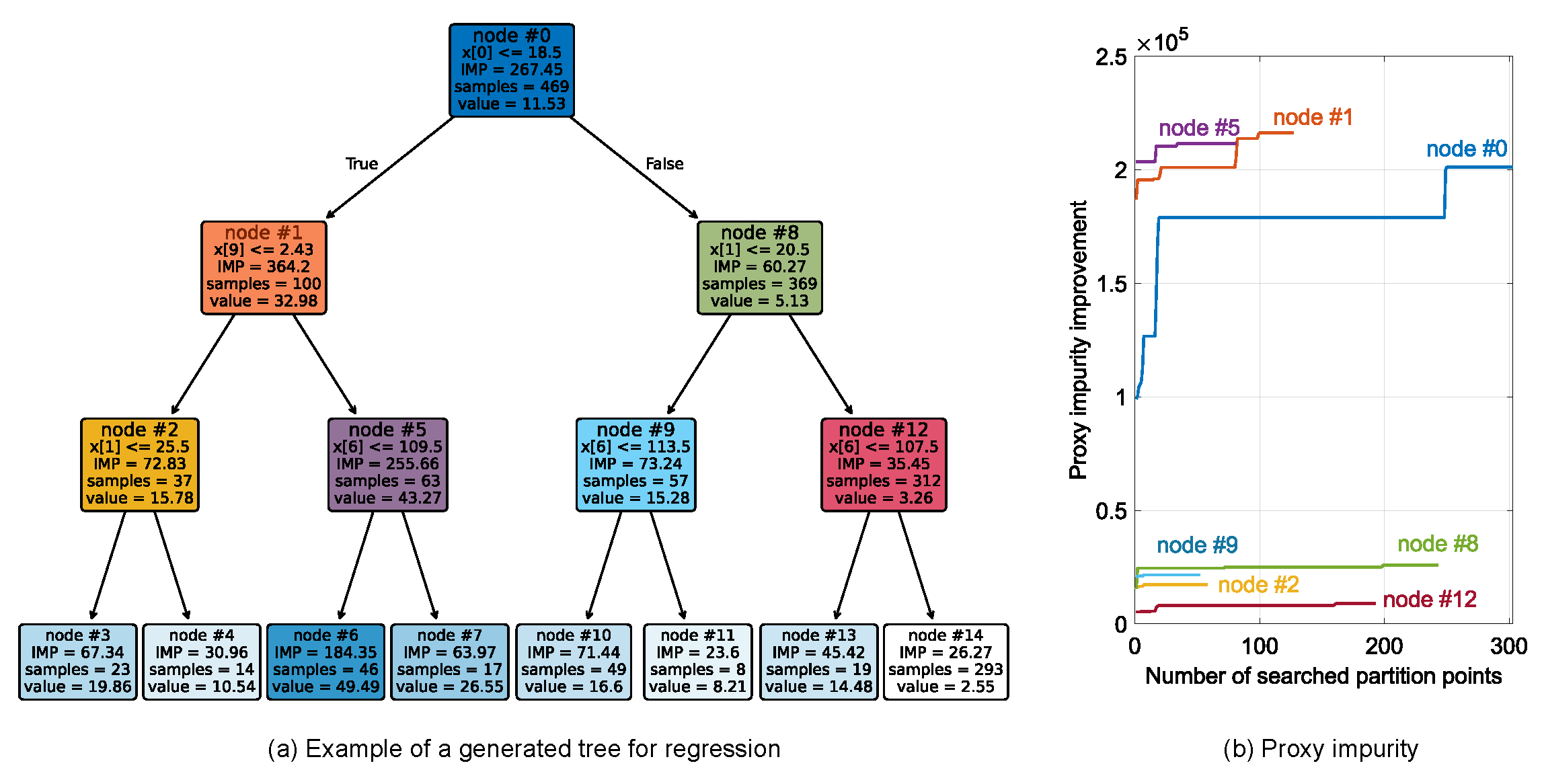

2.4. Best-First Mechanism

2.5. Classification Problems

3. Computational Experiments

3.1. Dataset

| Chemical Composition | The percentage of elements contained in a steel part is expressed as nine items: carbon (C), silicon (Si), manganese (Mn), phosphorus (P), sulfur (S), nickel (Ni), chromium (Cr), molybdenum (Mo), and copper (Cu). During heat treatment, these elements affect the treatment results in different ways, with carbon and chromium being particularly influential. The microstructural properties of metal alloys are influenced by both cooling rates and chemical composition [16,17,18,19]. Gao et al. [18] found an exponential relationship between the critical cooling rate in U75V rail steel and its chemical composition, specifically carbon (C), manganese (Mn), silicon (Si), and vanadium (V). Afflerbach et al. [22] used features of constituent elements, such as Al, Cu, Ni, Fe, B, Zr, Si, Co, Mg, and Ti, to predict the critical cooling rate for glass formation. Schultz et al. [23] utilized calculated features derived from chemical elements and molecular properties to predict the critical cooling rate of metallic glasses. |

| Material | The metals that serve as raw materials for constituting steel parts are used differently, depending on the application. For each material quality, standard values for the content of the above-mentioned chemical components are established. In the context of our dataset, seven different material qualities were included as categorical data. |

| Weight | The weight of each steel part. During heat treatment, there is a phenomenon called the mass effect, in which the greater the material’s mass, the weaker the heat treatment effect. |

| Shape | Geometry considerations of the steel part. Four visually distinguishable shapes: (1) gear shaft, for rod-shaped parts with gears; (2) washer, for cylindrical parts whose thickness is greater than their height; (3) ring, for cylindrical parts whose height is greater than their thickness, and (4) block, for parts without holes that are nearly three-dimensional |

3.2. Model Settings

- Random forest with default configuration. Here, we used the default parameter settings of the random forest implementation of scikit-learn [27]. The key representative parameters are as follows: the number of estimators, , the maximum allowed depth, , is set at the largest integer that can be represented as a 32-bit signed integer in NumPy (e.g., ), the minimum number of samples required to split a node , the minimum number of samples per leaf , and the minimum weighted count for splits . In the above, the number of estimators, , corresponds to the number of trees in the random forest.

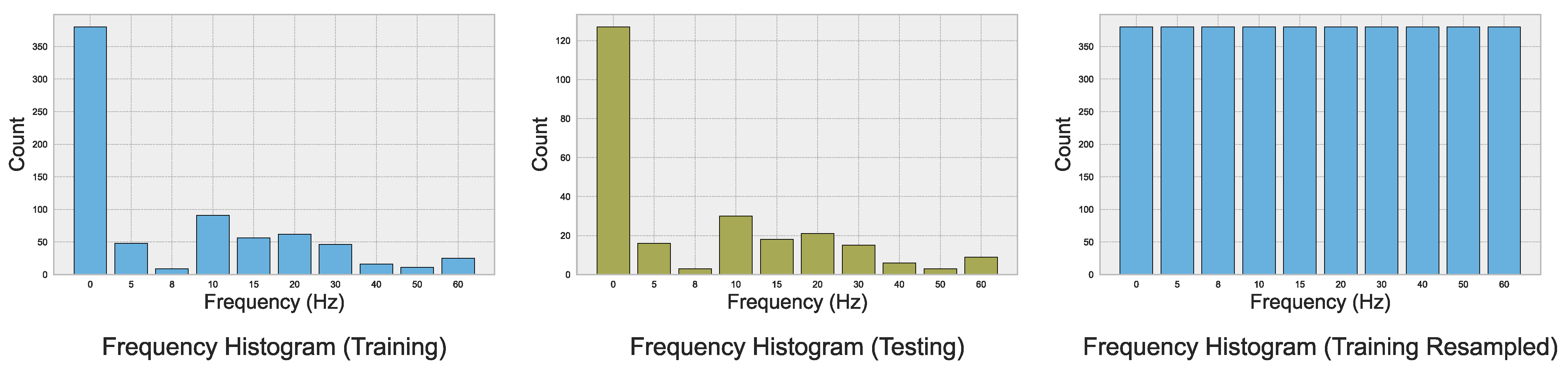

- Random forest with oversampling. Since the acquired real-world data are imbalanced—that is, the distribution of outputs is uneven—we implemented the oversampling technique (RandomOverSampler in [27]) to ensure a more balanced distribution of output classes. Random oversampling randomly duplicates samples from the minority class until all classes are equally distributed. Although alternative techniques for handling imbalanced data exist, such as resampling or class weighting, random oversampling is a straightforward method that avoids the creation of synthetic samples, thereby maintaining alignment with the real-world cooling conditions of steel parts.

- Random forest with hyperparameter tuning. In this configuration, we performed hyperparameter tuning on several key parameters of the random forest. As such, we considered the following parameters and their respective ranges: the number of estimators, , the maximum allowed depth, , the minimum number of samples required to split a node, , the minimum number of samples per leaf, , and the maximum number of features considered when searching for the best split at each node during tree construction, . Here, represents either a function (or fraction) of the total number of features when specified as such or an absolute integer value otherwise. The parameters were selected to balance the trade-off between bias and variance, as extreme values can either increase or decrease the level of randomness, thereby affecting overfitting and underfitting in the model. Due to the computationally expensive nature of the objective function, we used 10-fold cross-validation and Bayesian optimization to efficiently search for optimized parameters using a surrogate-based optimization approach [31].

- Random forests for both regression and classification. Since the real-world observations of cooling conditions for steel parts comprise a discrete set of output values in the range , it is possible to train both classification and regression models and evaluate their corresponding performance. Thus, we trained both classification and regression models for each of the aforementioned random forest configurations. Furthermore, for the regression models, to enable a meaningful comparison with the discrete nature of the observed outputs, we implemented an approach that approximates each continuous prediction by rounding it to the nearest integer. This approach ensures that predictions reflect real-world observations, enhancing interpretability and producing outputs consistent with the expected format, thereby increasing their relevance for decision-making and further analysis.

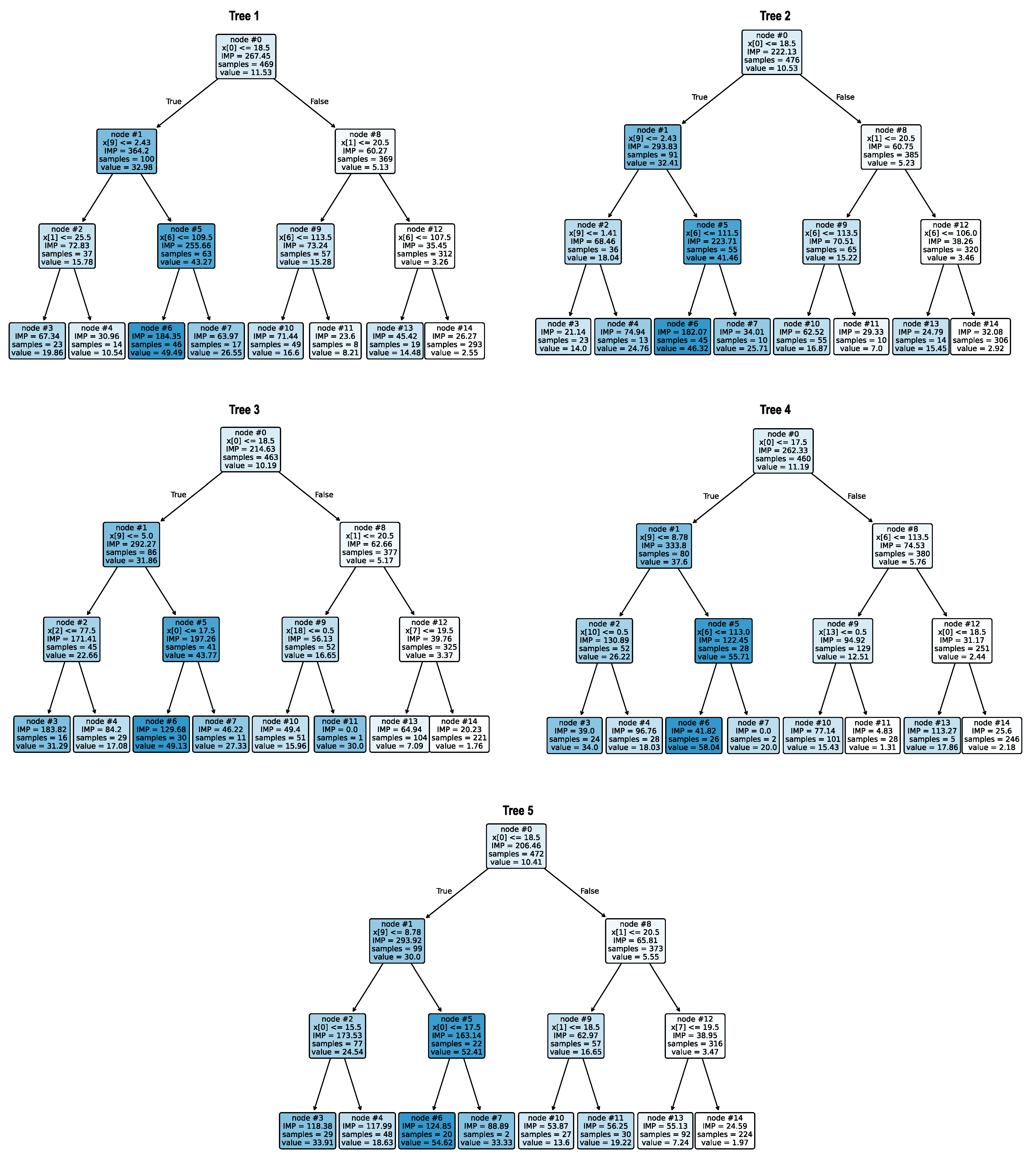

3.3. Example of a Decision Tree for Predicting the Cooling Parameter

3.4. Data Distribution

3.5. Regression with Default Configuration

- Computation time: Random forest quickly learned the suitable fitting, in around 0.19–0.20 s per trial.

- Training Metrics: MSE ranges from 3.17 to 4.41, with high values above 0.98, indicating a strong model fit.

- Testing Metrics: Test MSE varies more widely (11.43 to 33.44) with values between 0.84 and 0.94, showing a reasonable degree of variability in generalization.

- Metrics with Nearest Approximation: MSE and with a nearest approximation closely follow their continuous counterparts, confirming consistency across scales.

- Overall Performance: The model demonstrates a solid training accuracy and generally good testing performance, with some trials showing a decreased test accuracy.

| Training | Testing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Time (s) | MSE↓ | MSEn↓ | MSE↓ | MSEn↓ | ||||

| 1 | 0.19 | 4.20 | 0.9816 | 4.42 | 0.9806 | 11.43 | 0.9351 | 13.00 | 0.9262 |

| 2 | 0.19 | 3.69 | 0.9829 | 4.59 | 0.9788 | 16.09 | 0.9249 | 17.68 | 0.9175 |

| 3 | 0.19 | 4.41 | 0.9808 | 4.90 | 0.9787 | 20.14 | 0.8813 | 21.36 | 0.8741 |

| 4 | 0.20 | 3.50 | 0.9836 | 3.95 | 0.9815 | 26.67 | 0.8794 | 27.04 | 0.8777 |

| 5 | 0.19 | 3.87 | 0.9833 | 4.22 | 0.9818 | 19.72 | 0.8804 | 20.10 | 0.8781 |

| 6 | 0.20 | 3.93 | 0.9833 | 4.44 | 0.9811 | 16.47 | 0.8937 | 16.73 | 0.8920 |

| 7 | 0.20 | 4.13 | 0.9816 | 4.25 | 0.9810 | 18.43 | 0.9038 | 20.63 | 0.8923 |

| 8 | 0.20 | 3.79 | 0.9825 | 3.74 | 0.9827 | 13.06 | 0.9387 | 13.67 | 0.9359 |

| 9 | 0.19 | 3.17 | 0.9853 | 3.55 | 0.9836 | 33.44 | 0.8429 | 35.92 | 0.8312 |

| 10 | 0.20 | 3.80 | 0.9812 | 4.19 | 0.9793 | 20.49 | 0.9190 | 22.09 | 0.9126 |

3.6. Regression with Oversampling

- Computation Time: All trials completed rapidly, with times tightly clustered between 0.42 and 0.44 s.

- Training Metrics: Training MSE values are low (0.68 to 1.48), and values are consistently high (0.9961 to 0.9982), indicating an excellent model fit.

- Testing Metrics: Test MSE ranges from 11.25 to 29.19, with values between 0.8685 and 0.9487, reflecting strong but variable generalization.

- Metrics with Nearest Approximation: Normalized MSE and closely track their continuous counterparts, confirming stable performance across different scales.

- Overall Performance: Random oversampling yields robust training accuracy and generally strong testing results, with a number of trials showing a higher test error yet achieving reasonable predictive performance.

| Training | Testing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Time (s) | MSE↓ | MSEn↓ | MSE↓ | MSEn↓ | ||||

| 1 | 0.42 | 1.10 | 0.9971 | 1.26 | 0.9966 | 11.25 | 0.9487 | 12.02 | 0.9452 |

| 2 | 0.44 | 0.99 | 0.9974 | 1.02 | 0.9973 | 21.46 | 0.9005 | 21.19 | 0.9017 |

| 3 | 0.42 | 0.78 | 0.9979 | 0.83 | 0.9978 | 21.59 | 0.9015 | 23.62 | 0.8922 |

| 4 | 0.42 | 0.88 | 0.9977 | 0.91 | 0.9976 | 25.79 | 0.8804 | 27.43 | 0.8728 |

| 5 | 0.42 | 1.03 | 0.9972 | 1.09 | 0.9971 | 18.21 | 0.9180 | 20.42 | 0.9080 |

| 6 | 0.44 | 1.19 | 0.9968 | 1.25 | 0.9967 | 29.19 | 0.8685 | 30.22 | 0.8639 |

| 7 | 0.44 | 0.86 | 0.9977 | 0.95 | 0.9975 | 18.60 | 0.9152 | 18.61 | 0.9151 |

| 8 | 0.43 | 0.76 | 0.9980 | 0.79 | 0.9979 | 11.66 | 0.9459 | 12.02 | 0.9443 |

| 9 | 0.44 | 0.68 | 0.9982 | 0.72 | 0.9981 | 13.29 | 0.9384 | 12.97 | 0.9399 |

| 10 | 0.42 | 1.48 | 0.9961 | 1.57 | 0.9958 | 15.51 | 0.9281 | 15.67 | 0.9274 |

3.7. Regression with Hyperparameter Tuning

- Computation Time: Trials completed relatively fast, with learning time ranging from 0.16 to 2.12 s and an average time of 0.87 s.

- Training Performance: The training MSE is low, at 0.99, with very high values averaging 0.9974.

- Testing Performance: The test MSE averages 18.46, with an of around 0.9173, showing a competitive predictive accuracy compared to training.

- MSE with Nearest Approximation: MSE and values under a nearest approximation to predictive value closely mirror their continuous counterparts, confirming stable model behavior across scales.

- Variability: Standard deviations are moderate for MSE (training: 0.28, testing: 5.52) and very low for coefficients (training: 0.0009, testing: 0.023), indicating consistent performance across trials.

- Computation Time: The models were learned efficiently, with learning times ranging between 0.13 and 2.05 s, averaging 1.10 s.

- Training Performance: The mean training MSE is 0.97 with very high values, around 0.9976, indicating a highly accurate model fit.

- Testing Performance: The test MSE averages 18.85, with an of approximately 0.9156, showing the strong predictive capability when unseen data are used.

- MSE with Nearest Approximation: The normalized MSE and under a nearest-approximation approach closely align with continuous metrics, demonstrating the stable performance across scaling.

- Variability: Moderate standard deviations for MSE (training: 0.25; testing: 5.36) and low variability for (training: 0.0007; testing: 0.022) reflect consistent results across trials.

| Training | Testing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Time (s) | MSE↓ | MSEn↓ | MSE↓ | MSEn↓ | ||||

| 1 | 2.01 | 1.08 | 0.9971 | 1.19 | 0.9968 | 11.13 | 0.9492 | 12.42 | 0.9433 |

| 2 | 2.12 | 0.99 | 0.9974 | 1.04 | 0.9972 | 22.20 | 0.8971 | 22.76 | 0.8945 |

| 3 | 0.17 | 0.79 | 0.9979 | 0.84 | 0.9978 | 23.91 | 0.8909 | 24.99 | 0.8860 |

| 4 | 0.17 | 0.88 | 0.9976 | 0.94 | 0.9975 | 22.56 | 0.8954 | 21.70 | 0.8994 |

| 5 | 0.73 | 1.05 | 0.9972 | 1.10 | 0.9971 | 17.70 | 0.9203 | 19.21 | 0.9135 |

| 6 | 0.18 | 1.15 | 0.9969 | 1.23 | 0.9967 | 26.69 | 0.8798 | 28.58 | 0.8713 |

| 7 | 1.69 | 0.84 | 0.9978 | 0.89 | 0.9976 | 19.01 | 0.9133 | 20.85 | 0.9049 |

| 8 | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.9981 | 0.78 | 0.9979 | 11.15 | 0.9483 | 12.02 | 0.9442 |

| 9 | 0.16 | 0.62 | 0.9984 | 0.71 | 0.9981 | 13.93 | 0.9354 | 14.67 | 0.9320 |

| 10 | 1.25 | 1.47 | 0.9961 | 1.54 | 0.9959 | 15.53 | 0.9280 | 16.27 | 0.9246 |

3.8. Classification with Default Configuration

- Computation Time: The classification models were learned at about 0.13 s. per trial, indicating a fast learning ability.

- Training Performance: The classification models fit the training data with a very low MSE (0.78–2.06) and a high (0.9905–0.9964), showing strong learning from training data.

- Testing Performance: The models achieved higher MSEs (27.14–63.39) and reduced values (0.7061–0.8778), indicating some overfitting and moderate generalization.

- Variability: The classification models achieved low variability in training metrics and moderate variability in testing metrics, implying fluctuations in model generalization across trials.

| Training | Testing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Time (s) | MSE↓ | MSE↓ | ||

| 1 | 0.13 | 2.03 | 0.9905 | 28.21 | 0.8713 |

| 2 | 0.13 | 1.52 | 0.9929 | 52.10 | 0.7584 |

| 3 | 0.13 | 1.32 | 0.9938 | 46.65 | 0.7872 |

| 4 | 0.13 | 2.06 | 0.9905 | 63.39 | 0.7061 |

| 5 | 0.13 | 1.62 | 0.9924 | 27.14 | 0.8778 |

| 6 | 0.13 | 1.76 | 0.9918 | 41.94 | 0.8111 |

| 7 | 0.13 | 1.35 | 0.9937 | 29.60 | 0.8650 |

| 8 | 0.13 | 0.92 | 0.9957 | 50.37 | 0.7664 |

| 9 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.9964 | 42.50 | 0.8029 |

| 10 | 0.13 | 1.39 | 0.9936 | 33.67 | 0.8439 |

3.9. Classification with Oversampling

- Computation Time: Slightly increased compared to default parameters, ranging from 0.20 to 0.21 s. per trial, yet remains consistent and efficient.

- Training Performance: Models achieved low MSEs (0.73–1.96) and high values (0.9948–0.9980), indicating an excellent fit with the training data.

- Testing Performance: The models achieved an improved MSE in some trials compared to the ones with default parameters, with MSEs ranging from 28.57 to 59.56 and values ranging from 0.7238 to 0.8697, showing the moderate generalization and the reduction in overfitting.

- Variability: The models achieved low variability in computation times and training metrics and moderate variability in testing metrics, reflecting fluctuations in model generalization across trials.

| Training | Testing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Time (s) | MSE↓ | MSE↓ | ||

| 1 | 0.21 | 1.42 | 0.9962 | 28.57 | 0.8697 |

| 2 | 0.21 | 1.19 | 0.9968 | 45.69 | 0.7881 |

| 3 | 0.20 | 0.93 | 0.9975 | 47.56 | 0.7830 |

| 4 | 0.21 | 1.42 | 0.9962 | 59.56 | 0.7238 |

| 5 | 0.21 | 1.42 | 0.9962 | 33.58 | 0.8487 |

| 6 | 0.20 | 1.62 | 0.9957 | 44.76 | 0.7984 |

| 7 | 0.20 | 1.14 | 0.9970 | 31.84 | 0.8547 |

| 8 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 0.9980 | 52.08 | 0.7585 |

| 9 | 0.21 | 0.78 | 0.9979 | 34.08 | 0.8420 |

| 10 | 0.20 | 1.96 | 0.9948 | 34.17 | 0.8415 |

3.10. Classification with Hyperparameter Tuning

- Computation Time: The models were learned with more variability compared to previous approaches, with learning times ranging from 0.09 to 1.80 s. per trial, reflecting the increased computational cost of 10-fold cross-validation.

- Training Performance: The models achieved low MSEs (0.73–1.96) and high values (0.9948–0.9980), indicating a strong model fit on training data.

- Testing Performance: The model achieved MSEs on testing ranging from 15.65 to 54.46 and values from 0.7516 to 0.9274, suggesting better generalization and reduced overfitting in certain cases.

- Variability: The models achieved high variability in computation times and moderate variability in testing metrics, reflecting the effects of cross-validation and parameter tuning on model performance.

| Training | Testing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Time (s) | MSE↓ | MSE↓ | ||

| 1 | 1.66 | 1.42 | 0.9962 | 17.99 | 0.9179 |

| 2 | 0.23 | 1.19 | 0.9968 | 43.62 | 0.7977 |

| 3 | 0.09 | 0.93 | 0.9975 | 54.46 | 0.7516 |

| 4 | 0.41 | 1.42 | 0.9962 | 43.15 | 0.7999 |

| 5 | 0.16 | 1.42 | 0.9962 | 23.39 | 0.8947 |

| 6 | 0.17 | 1.62 | 0.9957 | 36.82 | 0.8342 |

| 7 | 1.08 | 1.14 | 0.9970 | 28.72 | 0.8690 |

| 8 | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.9980 | 33.35 | 0.8454 |

| 9 | 1.58 | 0.78 | 0.9979 | 15.65 | 0.9274 |

| 10 | 1.80 | 1.96 | 0.9948 | 21.84 | 0.8987 |

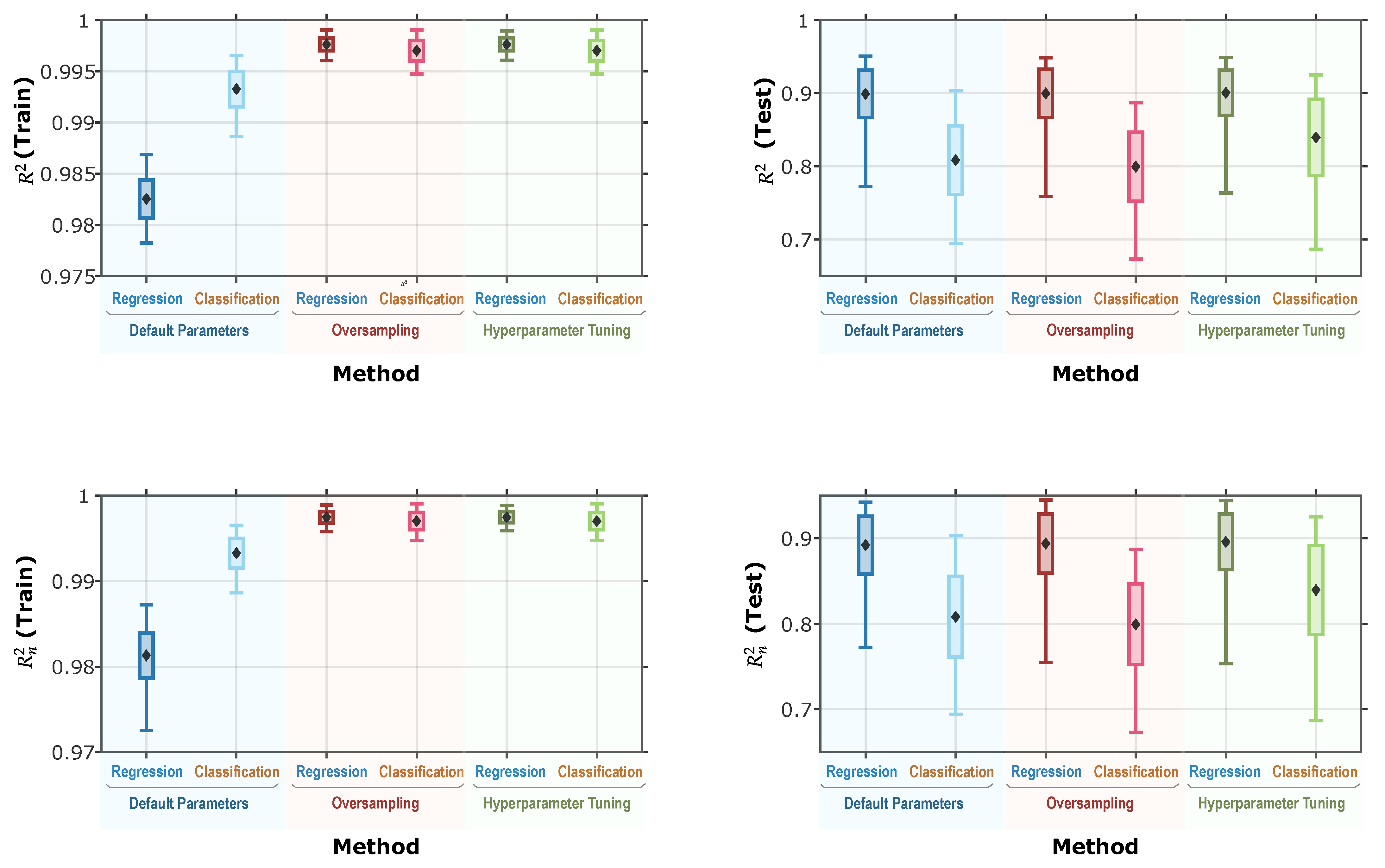

3.11. Overall Comparison

- Random forests utilizing oversampling and hyperparameter tuning outperform the default configuration in both MSE and metrics. However, the difference in performance between oversampling and hyperparameter tuning alone is not substantial. Given that hyperparameter tuning is a relatively computationally intensive process, the oversampling approach provides comparable performance benefits with significantly lower computational costs, making it a more efficient choice in practice.

- Although classification models initially outperformed regression models under default parameter configurations, the performance gap between the two approaches diminished significantly when oversampling and hyperparameter tuning were applied. In fact, regression models consistently outperformed classification models across all instances on the testing dataset. This finding underscores the practical advantages of using regression trees for estimating the cooling conditions of steel parts.

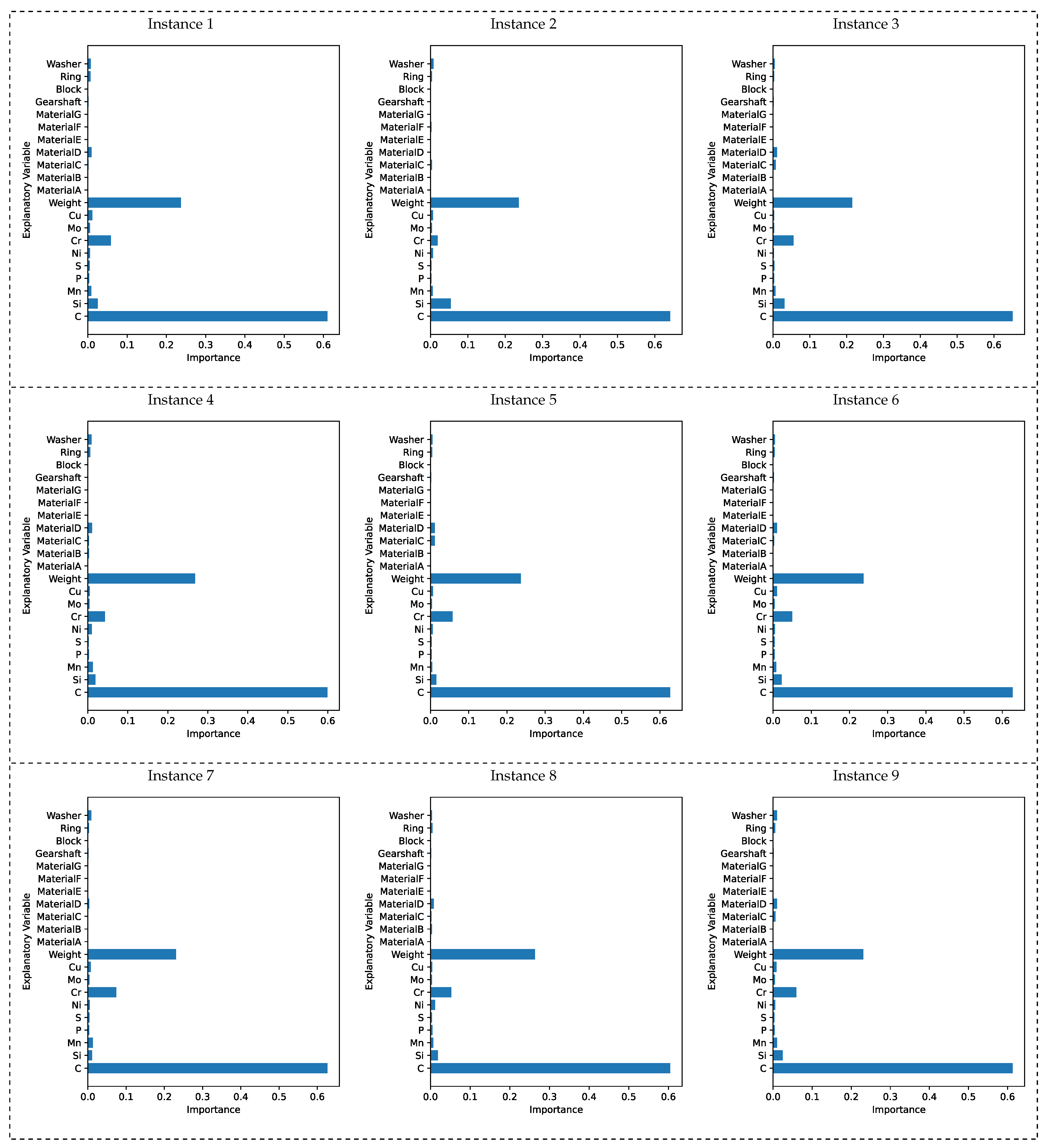

3.12. Feature Importance

- Chemical Composition: Carbon and chromium were found to play significant roles in determining the cooling conditions of steel parts. In heat treatment, carbon is widely recognized as the most influential element, as it directly affects wear resistance, hardness, and strength. The microstructural properties of metals are influenced by both cooling rates and chemical composition [16,17,18,19]. Under air cooling, increasing the carbon content induces an increase in hardness and brittleness [32]. Our results showed that carbon was the most important feature when decision trees were constructed to predict the cooling parameters of steel parts. Furthermore, chromium, which is also considered important in heat treatment due to its effect on hardenability and corrosion resistance, exhibited relatively high importance values in our analysis.

- Material: No consistent pattern was observed regarding the importance of the seven materials in model development. While some materials contributed more than others, there were no notable commonalities among them. Overall, this suggests that material type is not a significant factor in determining the cooling conditions of steel parts.

- Weight: After carbon, the weight of each steel part emerged as the second most important factor in building decision trees for estimating cooling parameters. This can be attributed to the well-known mass effect in steel-part annealing: heavier parts are less likely to be quenched thoroughly to the center, whereas smaller parts cool more quickly and uniformly, making complete quenching easier. Thus, differences in mass directly influence the efficiency of heat transfer and cooling, establishing weight as a crucial factor in determining optimal cooling conditions.

- Shape: Although it was initially thought that the ease of heat conduction due to part shape might have a significant impact, overall, none of the shapes emerged as particularly important factors. However, the washer and ring shapes showed relatively higher importance. This is likely because both shapes have a hollow center, which facilitates more efficient cooling compared to other shapes.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yi, Q.; Wu, X.; Zhuo, J.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Cao, H. An incremental data-driven approach for carbon emission prediction and optimization of heat treatment processes. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 72, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudda, S.; Hegde, A.; Sharma, S.; Gurumurthy, B. Optimization of various heat treatment parameters for superior combination of hardness and impact energy of AISI 1040 steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 38, 3900–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Su, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xia, L.; Shen, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, M. Influence of cooling rate during the heat treatment process on the precipitates and ductility behavior of inconel 718 superalloy fabricated by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 902, 146603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Gui, Y.; Han, Z.; Fu, H. The Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Powder Metallurgy Ti-48Al Alloy. Metals 2024, 14, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütjering, G. Influence of processing on microstructure and mechanical properties of (α + β) titanium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1998, 243, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hu, R.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Gao, Z. Grain refinement of 1 at.% Ta-containing cast TiAl-based alloy by cyclic air-cooling heat treatment. Mater. Lett. 2020, 274, 127940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wang, W.; Qi, X.; Lv, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, T.; Chen, J. Effects of heat treatment cooling methods on precipitated phase and mechanical properties of CoCrFeMnNi–Mo5C0.5 high entropy alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkovic, S.; Sabirov, I.; LLorca, J. Effect of the cooling rate on microstructure and hardness of MAR-M247 Ni-based superalloy. Mater. Lett. 2012, 73, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.A.; Ghara, T.; Das, B.; Kulkarni, D.M. Influence of cooling rate on microstructure, dislocation density, and associated hardness of laser direct energy deposited Inconel 718. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 495, 131575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.O. The Deformation and Ageing of Mild Steel: III Discussion of Results. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. B 1951, 64, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petch, N.J. The Cleavage Strength of Polycrystals. J. Iron Steel Inst. 1953, 174, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, B.H.; Park, J.; Jeon, J.; Heo, S.B.; Chung, W. Effect of cooling rate after heat treatment on pitting corrosion of super duplex stainless steel UNS S 32750. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2018, 65, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulkina, N.; Ivanov, O.; Deanisov, N.; Chekis, V. Cooling rate upon in air heat treatment and magnetic properties of amorphous soft magnetic alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 470, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Savvakin, D.G.; Ivasishin, O.M.; Pereloma, E.V. The effect of cooling rates on the microstructure and mechanical properties of thermo-mechanically processed Ti–Al–Mo–V–Cr–Fe alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 576, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, W.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, X.; Du, Z. Influence of cooling rate following heat treatment on microstructure and phase transformation for a two-phase alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 688, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Hu, F.; Zhou, W.; Ke, R.; Zhang, G.; Wu, K.; Qiao, W. Influences of Alloying Elements on Continuous Cooling Phase Transformation and Microstructures of Extremely Fine Pearlite. Metals 2019, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, I.; Ghosh, S.K.; Saha, R. Effects of cooling rate and strain rate on phase transformation, microstructure and mechanical behaviour of thermomechanically processed pearlitic steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 2685–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Song, H. Effect of Alloying Elements on Pearlite Critical Cooling Rate of U75V Rail-steel. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2023, 76, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, A.; Hossein Nedjad, S.; Hamed Zargari, H.; Saboori, A.; Yildiz, M. Predictive tools for the cooling rate-dependent microstructure evolution of AISI 316L stainless steel in additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 5530–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Xue, C.; Miao, Y.; Hou, Q.; Meng, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, X. Quantifying the effects of cooling rates on Fe-rich intermetallics in recycled Al-Si-Cu alloys by machine learning. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1014, 178718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Mao, X.; Wu, H.H.; Wang, S.; Xue, W.; Zhang, G.; Ullah, A.; Wang, H. A hybrid machine learning model for predicting continuous cooling transformation diagrams in welding heat-affected zone of low alloy steels. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 107, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afflerbach, B.T.; Francis, C.; Schultz, L.E.; Spethson, J.; Meschke, V.; Strand, E.; Ward, L.; Perepezko, J.H.; Thoma, D.; Voyles, P.M.; et al. Machine Learning Prediction of the Critical Cooling Rate for Metallic Glasses from Expanded Datasets and Elemental Features. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 2945–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, L.E.; Afflerbach, B.; Voyles, P.M.; Morgan, D. Machine learning metallic glass critical cooling rates through elemental and molecular simulation based featurization. J. Mater. 2025, 11, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akif Koç, M.; Ahlatci, H.; Esen, İ.; Eroğlu, M. Prediction of accelerated cooling rates in H-section steels using artificial neural networks. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 74, 106939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Liu, F.; Zhao, S.; Ren, R.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, T.; Liu, J. Prediction of critical cooling rate under rapid heating rate and short holding time for pearlitic rail steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 6534–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python, Version 1.7.2. 2025. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequential Model-Based Optimization in Python, Version 0.8.1. 2025. Available online: https://scikit-optimize.github.io/stable/index.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wei, S.; Zuo, L.; Mao, F. Effect of Carbon Content on Abrasive Impact Wear Behavior of Cr-Si-Mn Low Alloy Wear Resistant Cast Steels. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbale, A.M.; Ramesh, M.; Petru, J.; Chandramouli, T.; Srinath, M.; Shetty, R.K. A microstructural study and high-temperature oxidation behaviour of plasma sprayed NiCrAlY based composite coatings. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakatsukasa, I.; Parque, V.; Ito, Y.; Nakano, K. Predicting the Cooling Rate in Steel-Part Heat Treatment via Random Forests. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11676. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111676

Nakatsukasa I, Parque V, Ito Y, Nakano K. Predicting the Cooling Rate in Steel-Part Heat Treatment via Random Forests. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11676. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111676

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakatsukasa, Ikuto, Victor Parque, Yasuaki Ito, and Koji Nakano. 2025. "Predicting the Cooling Rate in Steel-Part Heat Treatment via Random Forests" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11676. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111676

APA StyleNakatsukasa, I., Parque, V., Ito, Y., & Nakano, K. (2025). Predicting the Cooling Rate in Steel-Part Heat Treatment via Random Forests. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11676. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111676