Some Improvements of Behavioral Malware Detection Method Using Graph Neural Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- the use of symmetric normalization, which better preserves feature balance and spectral smoothness in directed behavioral graphs;

- (ii)

- the investigation of multi-layer architectures, allowing deeper propagation of contextual information while studying over-smoothing effects; and

- (iii)

- a parallel dual-normalization model, designed to capture bidirectional dependencies between API call sequences.

- API—Application Programming Interface;

- CFG—Control Flow Graph;

- GAT—Graph Attention Network;

- GCN—Graph Convolutional Network;

- GED—Graph Edit Distance;

- GML—Graph Machine Learning;

- GNN—Graph Neural Network.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Graph Convolutional Networks and Graph Attention Networks: Short Overview

2.2. A Short Review of Malware Detection Methods Using GNNs

2.3. Improvement of Malware Detection Method Using Graph Neural Networks

2.3.1. Goals

2.3.2. Detailed Description of the Method Being Improved

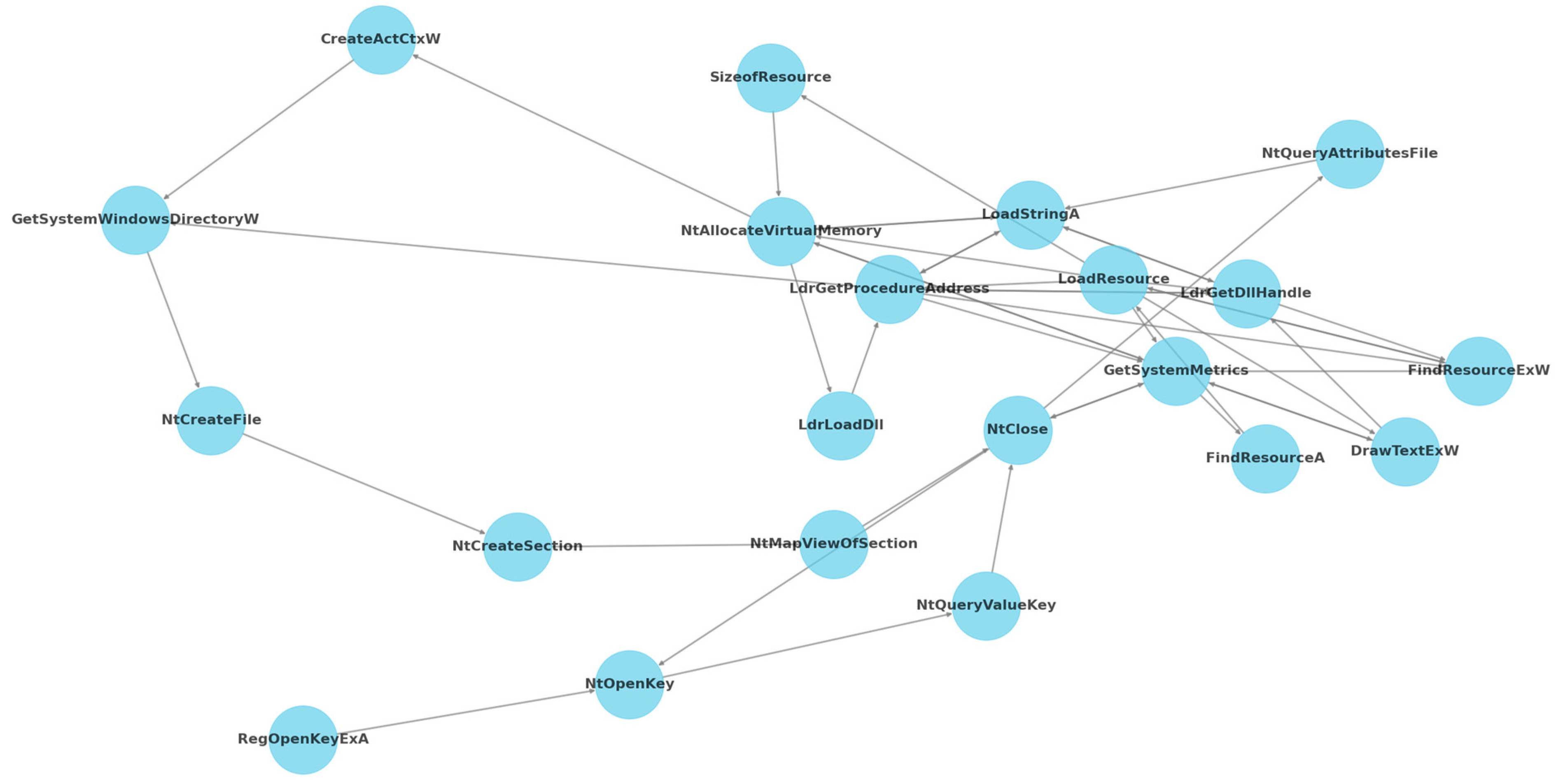

2.3.3. Description of Research Methodology

- : normalized adjacency matrix;

- adjacency matrix with self-loops;

- inverse matrix of the degree matrix of vertices.

- : the degree matrix D raised to the power of .

- : number of layers;

- : normalized matrix to the power of ;

- : feature vector;

- : weight vector.

- : activation function;

- : feature transmission weight from vertex to ;

- : linear attention operation;

- : weights vector;

- : feature vectors for vertices and .

2.3.4. Assumptions

3. Results

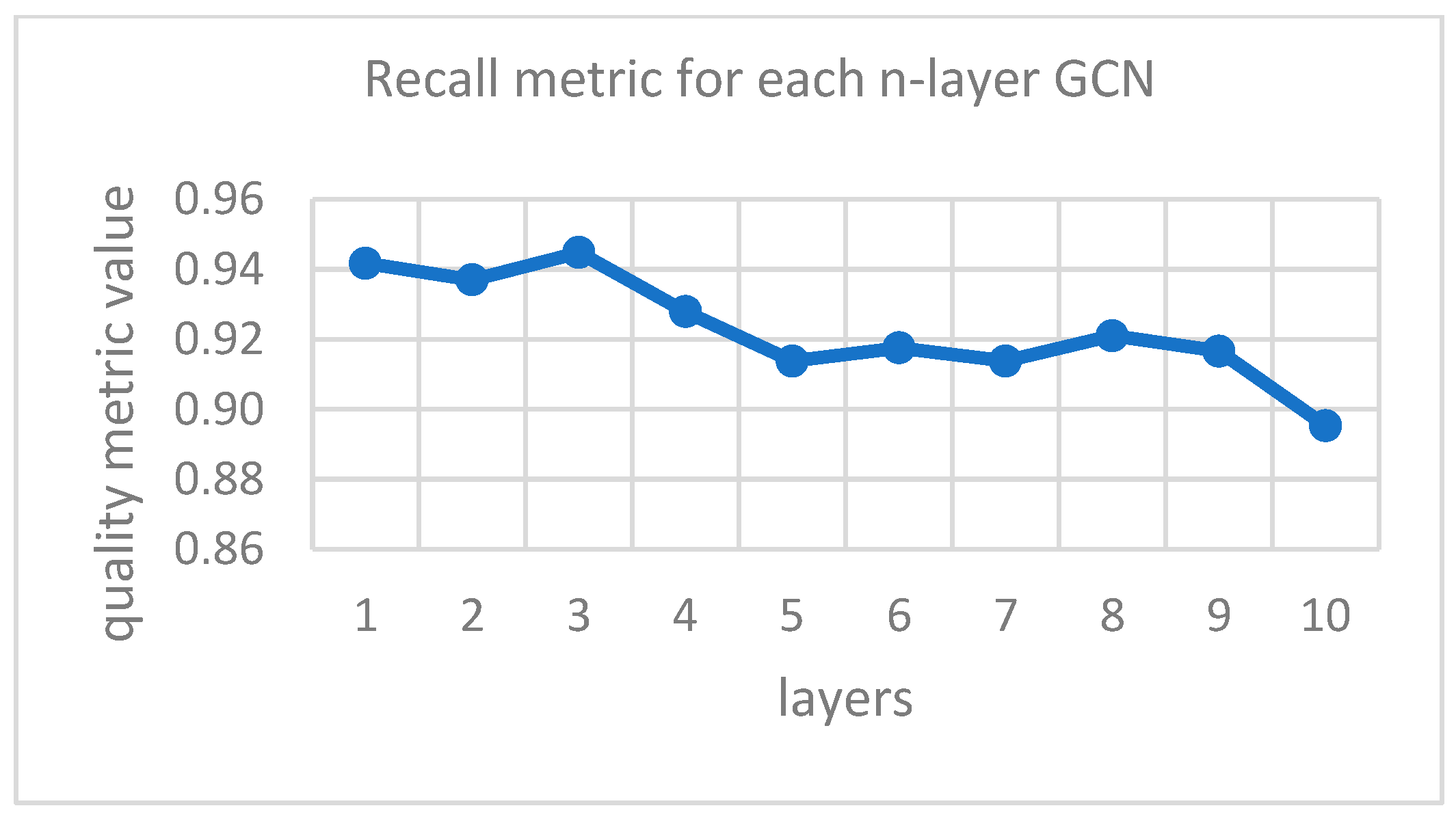

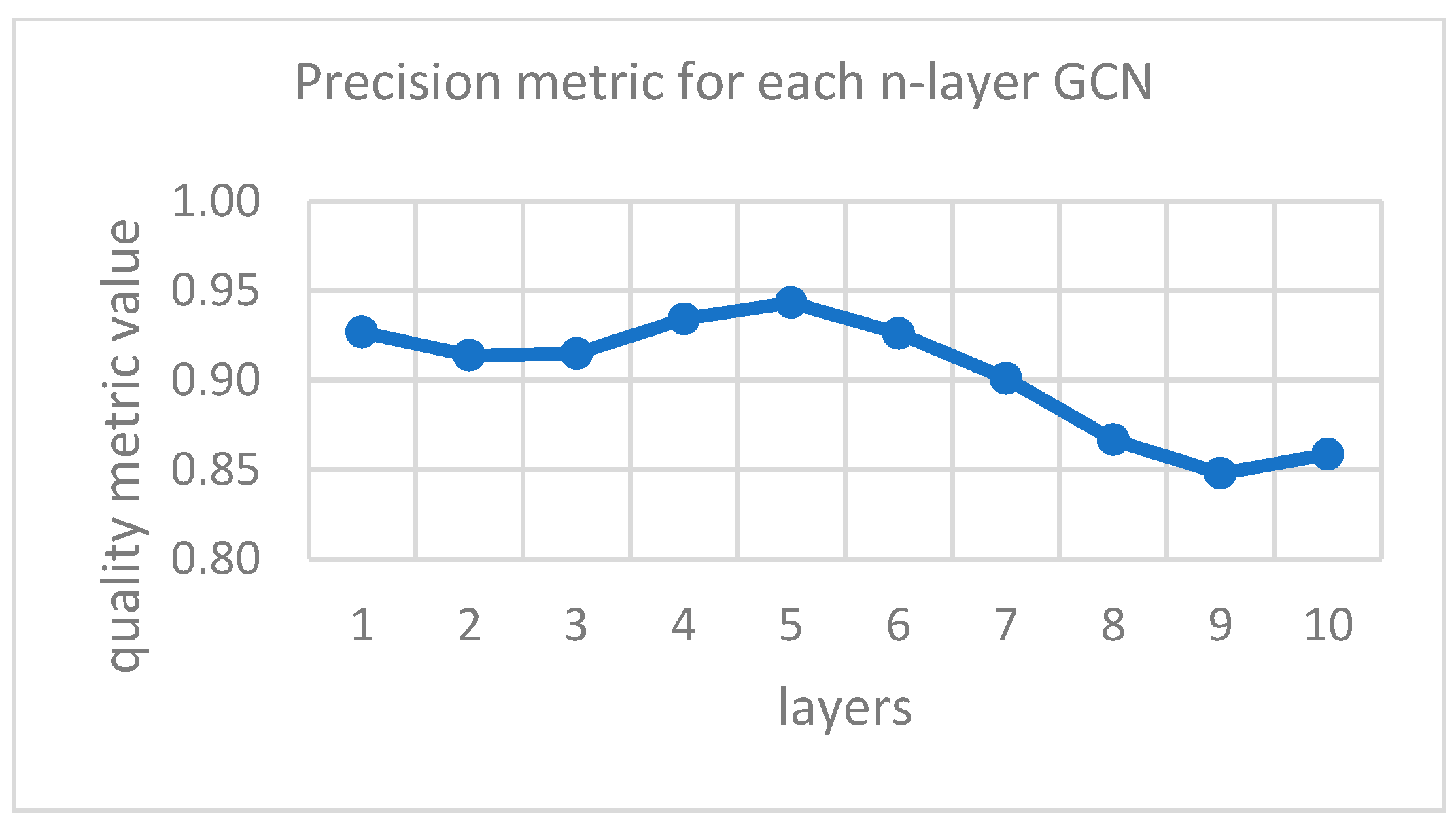

- The best results were achieved by the single-layer GCN model—modification 1. It has the highest values for each metric, except for precision and sensitivity, which are still quite high for this model. The five-layer model of the same improvement stands out with the highest precision, and the three-layer GCN with highest sensitivity.

- Some of the implemented models achieved better results than the original model. It should be noted, however, that the result values for the original model were obtained from a local compilation of this model, which is why they differ from the accuracy values given by the authors in [4]. The important thing to note as well is that both the original model and the n-layer GCN improvements were trained on the same set of hyperparameters (dropout = 0.1, max epochs = 20, batch size = 32, weights matrix size = 31). The fact that training conditions remained the same for all GCNs implies that the improvement is a result of changes in models’ architecture. The set chosen for n-layer GCN improvements was also utilized by us in an original GCN model (from [4]) to check, if possible, improvements could be attributed to architectural changes. It is worth mentioning that in the research conducted in [4], the authors used pre-selected hyperparameter values equal to 32—the batch size, 30—the number of epochs, and 0.6—the dropout. Models of GAT and concurrent, single-layer GCNs were built using separately chosen sets of hyperparameters because of substantial differences between them and GCN models.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Song, L. Heterogeneous Graph Neural Networks for Malicious Account Detection. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Torino, Italy, 22–26 October 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 2077–2085. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wen, R.; Wu, C.; Huang, Y.; Xiong, J. FdGars: Fraudster Detection via Graph Convolutional Networks in Online App Review System. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Schranko De Oliveira, A.; Sassi, R.J. Behavioral Malware Detection Using Deep Graph Convolutional Neural Networks. TechRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gayar, M.M.; Abouhawwash, M.; Askar, S.S.; Sweidan, S. A Novel Approach for Detecting Deep Fake Videos Using Graph Neural Network. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sun, L.; Deng, Y.; Peng, H.; Yu, P.S. Enhancing Graph Neural Network-Based Fraud Detectors against Camouflaged Fraudsters. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual, 19–23 October 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Dou, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Deng, Y.; Peng, H. Alleviating the Inconsistency Problem of Applying Graph Neural Network to Fraud Detection. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 25–30 July 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1569–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Sun, X.; Bo, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, B. BGNN4VD: Constructing Bidirectional Graph Neural-Network for Vulnerability Detection. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 136, 106576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, H.; Hua, J.; Xu, G.; Sui, Y. DeepWukong: Statically Detecting Software Vulnerabilities Using Deep Graph Neural Network. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2021, 30, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Siow, J.; Du, X.; Liu, Y. Devign: Effective Vulnerability Identification by Learning Comprehensive Program Semantics via Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.03496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yin, H.; Liu, C.; Song, D. DeepMem: Learning Graph Neural Network Models for Fast and Robust Memory Forensic Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–19 October 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 606–618. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, O.; Maurya, P.; Nagarkar, P.; Islam, K.M.; Crushev, C. A Survey on Locality Sensitive Hashing Algorithms and Their Applications. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.08942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, C.; Dullien, T.; Vinyals, O.; Kohli, P. Graph Matching Networks for Learning the Similarity of Graph Structured Objects. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.12787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Feng, Q.; Yin, H.; Song, L.; Song, D. Neural Network-Based Graph Embedding for Cross-Platform Binary Code Similarity Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Mary, A.; Edison, A. Deep Fake Detection Using Deep Learning Techniques: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Control, Communication and Computing (ICCC), Thiruvananthapuram, India, 19–21 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, M.S.; Nobi, M.N.; Murali, B.; Sung, A.H. Deepfake Detection: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 25494–25513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, M.; Chan, P. Scalable Function Call Graph-Based Malware Classification. In Proceedings of the Seventh ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 22–24 March 2017; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Chiueh, T.; Shin, K. Large-Scale Malware Indexing Using Function-Call Graphs. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security 2009, Chicago, IL, USA, 9–13 November 2009; pp. 611–620. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Xiao, B.; Tao, D.; Li, X. A Survey of Graph Edit Distance. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2010, 13, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wu, L.; Xi, S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y.; Zheng, N. A Similarity Metric Method of Obfuscated Malware Using Function-Call Graph. J. Comput. Virol. Hacking Tech. 2013, 9, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, S.; Polenakis, I. A Graph-Based Model for Malware Detection and Classification Using System-Call Groups. J. Comput. Virol. Hacking Tech. 2017, 13, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Turki, T.; Wang, J. Malware Detection Using Deep Learning and Graph Embedding. In Proceedings of the 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Orlando, FL, USA, 17–20 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, A.; Leskovec, J. Node2vec: Scalable Feature Learning for Networks. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 855–864. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, J.; Kocheturov, A.; Tresp, V.; Seidl, T. NF-GNN: Network Flow Graph Neural Networks for Malware Detection and Classification. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Scientific and Statistical Database Management, Tampa, FL, USA, 6–7 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Lang, B.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Song, Y. Android Malware Detection Method Based on Graph Attention Networks and Deep Fusion of Multimodal Features. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, S.D.; Polenakis, I. Behavior-Based Detection and Classification of Malicious Software Utilizing Structural Characteristics of Group Sequence Graphs. J. Comput. Virol. Hack. Tech. 2022, 18, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokouhinejad, H.; Higgins, G.; Razavi-Far, R.; Mohammadian, H.; Ghorbani, A.A. On the Consistency of GNN Explanations for Malware Detection. Inf. Sci. 2025, 721, 122603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, P.; Zeng, D.; Sun, C. DeepCatra: Learning Flow- and Graph-Based Behaviours for Android Malware Detection. IET Inf. Secur. 2023, 17, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Dong, H. Malware Detection with Dynamic Evolving Graph Convolutional Networks. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 7261–7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Tian, D.; Fu, X.; Hu, C. A Novel Malware Detection Method Based on Audit Logs and Graph Neural Network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 152, 110524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Yue, T.; You, Y.; Lv, Z.; Tang, X.; Hu, J.; Yin, H. A Resilience Recovery Method for Complex Traffic Network Security Based on Trend Forecasting. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2025, 2025, 3715086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, T.; de Souza, A.H., Jr.; Fifty, C.; Yu, T.; Weinberger, K.Q. Simplifying Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.07153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A. Malware Analysis Datasets: API Call Sequences. TechRxiv 2019. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ang3loliveira/malware-analysis-datasets-api-call-sequences (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Li, Q.; Han, Z.; Wu, X.-M. Deeper Insights into Graph Convolutional Networks for Semi-Supervised Learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.07606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oono, K.; Suzuki, T. Graph Neural Networks Exponentially Lose Expressive Power for Node Classification. arXiv 2021, arXiv:1905.10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameter | Improvement 1 (Extended GCN Model) | Improvement 2 (GAT Model) | Improvement 3 (Parallel GCN Model) |

|---|---|---|---|

| W matrix size | [31, 62] | [31, 62] | [31, 62] |

| dropout rate | [0.1, 0.4, 0.6] | [0.1, 0.4, 0.6] | [0.4, 0.6] |

| batch size | [32, 64] | [32, 64] | [32, 64] |

| number of epochs | [20, 30] | [30, 40] | [30, 40] |

| GCN layers/GAT heads | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] | [1, 2] | [1] |

| Type of Model | No. Layers/Attention Heads | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | 95% Confid. Interval for the Mean | Mean | Std | 95% Confid. Interval for the Mean | Mean | Std | 95% Confid. Interval for the Mean | ||

| GCN [4] | 1 | 0.922 | 0.005 | [0.918; 0.925] | 0.935 | 0.006 | [0.930; 0.939] | 0.908 | 0.009 | [0.901; 0.914] |

| Improvement 1. (extended GCN model) | 1 | 0.935 | 0.005 | [0.931; 0.938] | 0.927 | 0.011 | [0.919; 0.934] | 0.942 | 0.005 | [0.938; 0.946] |

| 2 | 0.925 | 0.003 | [0.923; 0.927] | 0.914 | 0.005 | [0.910; 0.918] | 0.937 | 0.004 | [0.934; 0.940] | |

| 3 | 0.929 | 0.003 | [0.927; 0.931] | 0.915 | 0.006 | [0.910; 0.919] | 0.945 | 0.002 | [0.943; 0.946] | |

| 4 | 0.932 | 0.006 | [0.928; 0.937] | 0.934 | 0.012 | [0.926; 0.943] | 0.928 | 0.008 | [0.922; 0.933] | |

| 5 | 0.931 | 0.004 | [0.928; 0.933] | 0.943 | 0.007 | [0.939; 0.948] | 0.914 | 0.005 | [0.910; 0.917] | |

| 6 | 0.923 | 0.004 | [0.920; 0.926] | 0.926 | 0.009 | [0.920; 0.932] | 0.918 | 0.003 | [0.915; 0.920] | |

| 7 | 0.908 | 0.006 | [0.904; 0.912] | 0.901 | 0.011 | [0.893; 0.909] | 0.914 | 0.004 | [0.911; 0.917] | |

| 8 | 0.891 | 0.014 | [0.881; 0.901] | 0.867 | 0.025 | [0.849; 0.884] | 0.921 | 0.006 | [0.917; 0.925] | |

| 9 | 0.877 | 0.018 | [0.864; 0.890] | 0.848 | 0.037 | [0.822; 0.874] | 0.917 | 0.016 | [0.905; 0.928] | |

| 10 | 0.874 | 0.014 | [0.865; 0.884] | 0.859 | 0.036 | [0.833; 0.884] | 0.895 | 0.023 | [0.879; 0.911] | |

| Improvement 2. | 1 | 0.878 | 0.009 | [0.872; 0.885] | 0.865 | 0.015 | [0.854; 0.876] | 0.892 | 0.012 | [0.884; 0.901] |

| (GAT model) | 2 | 0.780 | 0.140 | [0.679; 0.880] | 0.674 | 0.338 | [0.432; 0.916] | 0.679 | 0.344 | [0.432; 0.925] |

| Improvement 3. (parallel GCNs model) | 2 × 1 | 0.913 | 0.011 | [0.905; 0.921] | 0.910 | 0.018 | [0.897; 0.923] | 0.919 | 0.016 | [0.907; 0.930] |

| Type of Model | No. Layers/Attention Heads | F1 | ROC AUC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | 95% Confid. Interval for the Mean | Mean | Std | 95% Confid. Interval for the Mean | ||

| GCN [4] | 1 | 0.921 | 0.005 | [0.917; 0.925] | 0.971 | 0.002 | [0.970; 0.972] |

| Improvement 1. (extended GCN model) | 1 | 0.934 | 0.004 | [0.931; 0.937] | 0.981 | 0.002 | [0.980; 0.982] |

| 2 | 0.925 | 0.003 | [0.923; 0.927] | 0.978 | 0.002 | [0.977; 0.979] | |

| 3 | 0.930 | 0.002 | [0.928; 0.931] | 0.978 | 0.001 | [0.977; 0.978] | |

| 4 | 0.931 | 0.006 | [0.927; 0.935] | 0.973 | 0.002 | [0.972; 0.974] | |

| 5 | 0.928 | 0.004 | [0.925; 0.931] | 0.965 | 0.001 | [0.964; 0.966] | |

| 6 | 0.922 | 0.004 | [0.919; 0.925] | 0.962 | 0.001 | [0.961; 0.963] | |

| 7 | 0.907 | 0.006 | [0.903; 0.911] | 0.951 | 0.002 | [0.950; 0.953] | |

| 8 | 0.893 | 0.012 | [0.884; 0.901] | 0.952 | 0.001 | [0.951; 0.953] | |

| 9 | 0.880 | 0.015 | [0.870; 0.891] | 0.948 | 0.002 | [0.947; 0.950] | |

| 10 | 0.876 | 0.010 | [0.869; 0.882] | 0.943 | 0.002 | [0.942; 0.944] | |

| Improvement 2. | 1 | 0.878 | 0.008 | [0.872; 0.884] | 0.938 | 0.008 | [0.932; 0.943] |

| (GAT model) | 2 | 0.676 | 0.340 | [0.432; 0.919] | 0.836 | 0.170 | [0.714; 0.957] |

| Improvement 3. (parallel GCNs model) | 2 × 1 | 0.914 | 0.011 | [0.906; 0.922] | 0.954 | 0.005 | [0.951; 0.958] |

| Modification/Computational Complexity | Estimated Computational Complexity |

|---|---|

| GCN [4] | |

| Modification 1 (modified GCN model) | |

| Modification 2 (model GAT) | [34] |

| Modification 3 (parallel GCN model) |

| Type of Model | No. Layers/Attention Heads | Initialization | Training | Evaluation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std | Mean | Std | Mean | Std | ||

| GCN [4] | 1 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 17.262 | 1.209 | 0.317 | 0.050 |

| Improvement 1. (extended GCN model) | 1 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 46.543 | 5.514 | 0.846 | 0.147 |

| 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 44.526 | 2.655 | 0.876 | 0.199 | |

| 3 | 0.0002 | 0.0004 | 54.217 | 5.478 | 1.049 | 0.131 | |

| 4 | 0.0017 | 0.0047 | 58.483 | 0.961 | 1.123 | 0.031 | |

| 5 | 0.0017 | 0.0047 | 60.333 | 0.240 | 1.158 | 0.041 | |

| 6 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 61.409 | 0.720 | 1.171 | 0.033 | |

| 7 | 0.0002 | 0.0004 | 61.709 | 3.042 | 1.181 | 0.118 | |

| 8 | 0.0002 | 0.0004 | 51.027 | 2.634 | 1.070 | 0.142 | |

| 9 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 52.283 | 4.048 | 1.019 | 0.121 | |

| 10 | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | 60.504 | 10.117 | 1.252 | 0.250 | |

| Improvement 2. | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 97.060 | 1.101 | 1.344 | 0.078 |

| (GAT model) | 2 | 0.0004 | 0.0005 | 105.626 | 6.163 | 1.523 | 0.093 |

| Improvement 3. (parallel GCNs model) | 2 × 1 | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | 62.273 | 1.235 | 1.202 | 0.038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarapata, Z.; Romańczuk, J. Some Improvements of Behavioral Malware Detection Method Using Graph Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11686. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111686

Tarapata Z, Romańczuk J. Some Improvements of Behavioral Malware Detection Method Using Graph Neural Networks. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11686. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111686

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarapata, Zbigniew, and Jan Romańczuk. 2025. "Some Improvements of Behavioral Malware Detection Method Using Graph Neural Networks" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11686. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111686

APA StyleTarapata, Z., & Romańczuk, J. (2025). Some Improvements of Behavioral Malware Detection Method Using Graph Neural Networks. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11686. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111686