1. Introduction

The human hand is central to precise motor tasks and social interaction, and its constant use makes it highly susceptible to traumatic injury with substantial personal and socioeconomic consequences [

1]. Upper-limb amputations—of which finger losses constitute a large share—are a growing public health concern; the index, ring, and middle fingers are most often affected, while the thumb, though less frequently lost, is crucial for hand function. Globally, millions live with limb loss, most commonly due to occupational and traffic accidents [

2,

3].

To address the functional and psychological impact of finger loss, prosthetic devices play an important role. Hand prostheses are generally classified as functional (limited movement) or cosmetic (appearance-focused) [

4]. Cosmetic finger prostheses, typically silicone-based, are designed to match skin color, texture, and shape. Although they do not restore active motion, they improve self-image and confidence and are particularly helpful after partial finger amputations by supporting everyday interactions, protecting sensitive tissue, and enabling basic stabilization or simple gripping [

5].

Cosmetic finger prostheses may also form part of full or partial hand prostheses. In more extensive losses, multiple fingers can be integrated on a shared base or glove, restoring appearance and limited function. These custom systems match the user’s anatomy and skin tone, protect residual tissue, and provide a more complete solution than separate finger prostheses [

6].

Despite clear benefits, cosmetic prostheses are costly, posing particular challenges in pediatric care. Full hand prostheses require frequent replacement to match growth; poor fit over time can cause discomfort, postural imbalance, and reduced use. Many young users also report devices as heavy, uncomfortable, unreliable, or esthetically unsatisfying, limiting long-term adherence. Although individual finger prostheses also need periodic updates, they are typically replaced with the full system to maintain anatomical consistency; regular adjustments support appearance, posture, and overall development [

7].

Additive Manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing, has emerged as a promising method for the production of prosthetic devices, particularly in the context of personalized and time-sensitive applications. One of its main advantages is the ability to rapidly fabricate a prosthesis directly from a digital model, significantly shortening the time between patient measurement and final production [

8]. The overall cost is relatively low compared to conventional techniques, and the digital workflow allows for easy design modifications prior to fabrication, without the need for specialized tooling to produce prostheses even outside specialized prosthetic laboratories [

9]. In addition, many AM technologies support a high degree of automation—from 3D scanning of the residual limb, through anatomically tailored computer-aided design, to direct manufacturing—enabling a streamlined and repeatable process.

Most additive manufacturing techniques currently applied in prosthetic fabrication rely on rigid or semi-rigid polymer materials, such as PLA, ABS, PET-G, or various photopolymers used in stereolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP). These materials are well-suited for structural components, frames, or mechanical housings due to their dimensional stability and strength. However, in the context of cosmetic hand prostheses—particularly finger restorations—these rigid materials fall short of replicating the tactile and mechanical properties of human soft tissue. The natural appearance and flexibility expected from a cosmetic prosthesis require materials that can simulate soft skin-like behavior, with a low Young’s modulus, high elasticity, and resistance to fatigue under cyclic loading [

10].

Traditional cosmetic finger prostheses are most commonly fabricated from medical-grade silicone elastomers, which provide a favorable combination of flexibility, biocompatibility, and visual realism. In everyday use, cosmetic hand prostheses are not only passive devices but may also be subjected to incidental functional loads [

11,

12]. A typical scenario involves the user resting the prosthetic hand on a surface for balance or support. Although users are generally advised not to apply full body weight through cosmetic prostheses—such as when rising from a chair—situations involving moderate loading are common. During light contact with a surface, such as resting the hand on a table, prosthetic fingers typically experience loads of 10–20 N, requiring them to flex and recover repeatedly without failure. However, when an adult supports their upper body weight by leaning on their hands, the forces exerted on the prosthesis can exceed 150–200 N, demanding significantly greater strength and durability. This necessitates not only sufficient material elasticity but also durability under repeated stress within the elastic range [

13].

The development and adoption of AM materials that can match the performance of silicone in this context remain limited but are gradually evolving. Several additive manufacturing methods support the processing of flexible materials, though each offers different capabilities and limitations in terms of mechanical performance and resolution. In material extrusion techniques such as Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) or Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF)—collectively referred to as MEX (Material Extrusion)—thermoplastic elastomers like TPU and TPE are commonly used [

14]. These materials are available in various Shore hardness grades and can provide sufficient flexibility for non-load-bearing cosmetic components. However, the layer-by-layer nature of FDM often results in limited surface quality and mechanical anisotropy, especially in thin-walled, compliant structures such as fingers [

15].

PolyJet technology, which involves jetting photopolymers and curing them with UV light, enables the printing of highly detailed, multi-material parts with tunable flexibility. Flexible resins in PolyJet can simulate soft tissues with good surface finish and controlled mechanical response, making the method particularly attractive for cosmetic applications—although the equipment and materials are relatively costly [

16].

In masked stereolithography (MSLA), flexible or elastic resins can also be used, though they typically exhibit lower elongation at break and limited tear resistance compared to silicones. While MSLA allows for fine surface detail and complex geometries, its suitability for repeated mechanical loading is still under investigation [

17]. Among presented additive manufacturing methods, MSLA offers high resolution/detail; however, its mechanical strength properties are generally inferior [

18]. A recent study fabricated flexible stochastic Voronoi lattices in MSLA and experimentally characterized their cyclic compression response. The lattices exhibited foam-like mechanics—buckling, plateau, and densification regimes—with pronounced energy dissipation and elastic shape recovery, underscoring MSLA’s potential for lightweight, flexible, energy-absorbing designs [

19].

Importantly, beyond mechanical and esthetic considerations, the biocompatibility of the printed materials remains a critical factor. Not all flexible polymers used in AM are certified for prolonged skin contact, especially in sensitive areas such as the residual limb. The use of these materials in commercially available prosthetic devices is subject to regulatory and must comply with relevant medical device standards. Therefore, even when a material demonstrates promising mechanical behavior, its clinical use may be restricted unless it meets both safety and legal requirements for biomedical applications [

20,

21].

Fewer studies examine how specific AM methods and parameter choices translate into the mechanical response of prosthetic fingers. Here, we address this gap by using the finger geometry, selecting process settings to promote comparable stiffness, and applying mechanical test protocols, with parameters reported for reproducibility.

The authors evaluate pass/fail esthetic conformity under standardized viewing and handling, quantify quasi-static mechanical response via adapted three-point bending and cyclic compression while clarifying limits to cross-study comparability, and compare build time and material usage as practical proxies for cost and throughput. The study does not include human-subject testing or clinical outcomes, and biocompatibility certification is outside its remit; findings are restricted to manufacturing factors, mechanical properties, and economic metrics.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on the authors’ experience and a review of relevant literature, ten experimental series of samples were defined, each consisting of upper limb prosthetic fingers. Each sample series was fabricated using a different manufacturing method or distinct process parameters. However, all samples were produced in the same laboratory, under controlled environmental conditions (22 °C and approximately 50% relative humidity), and tested within 24 h of fabrication. Only basic post-processing operations were applied, tailored to the specific manufacturing method used. These operations were deliberately limited so as not to significantly alter the physicochemical characteristics of the raw parts as they emerged from the machine’s build chamber. This constraint was critical for the subsequent esthetic evaluation of the samples.

The esthetic assessment was subjective and based on a binary classification system: each sample was evaluated as either suitable for use or unsuitable for use. In this study, the assessment served as a pass/fail conformity check to flag gross manufacturing defects rather than a measure of esthetic quality; non-conformities were defined a priori (e.g., pronounced layer separation, voids/ruptures, severe warping or distortion, incomplete curing/bonding, or surface artifacts likely to impair function or safety). Evaluations were performed under consistent ambient lighting at normal viewing distance, with samples inspected in the as-printed state after routine cleaning and without cosmetic rework. The evaluation was performed by a group of four experts: two specialists in additive manufacturing, one biomedical engineer, and one prosthetist. The authors assume that the production process for individualized prosthetic devices should strive for maximum automation. Manual interventions—such as esthetic refinements performed by an artisan or craftsman—should be minimized or eliminated from the manufacturing workflow in order to reduce costs and improve accessibility to orthopedic equipment.

The digital geometry of the finger model used to fabricate the test samples (

Figure 1) was generated using a proprietary software application for designing hand prostheses. This geometry was based on a three-dimensional scan of an adult human hand. The generated finger had an approximate volume of 15.5 cm

3 and a surface area of approximately 4100 mm

2, with overall dimensions of 19 × 64 × 46 mm. The scan data was not modified, as it served as the basis for producing a monolithic cosmetic hand prosthesis. In cases where the fingers were intended to function as components of a more complex prosthetic system, the geometry could be segmented into smaller parts or augmented with additional structural features, depending on the type and function of the target prosthesis. It should be noted that the prosthetic fingers, which are components of a hand prosthesis, do not maintain permanent contact with the human body. The issue of medical biocompatibility is not a central concern in the present study.

To evaluate the mechanical strength of the prosthetic fingers, a universal testing machine—Sunpock WDW-5D-HS (Guizhou Sunpoc Tech Industry Co., Ltd., Guiyang, China)—was used. Two types of strength tests were performed: static three-point bending and dynamic compression. These loading conditions, either individually or in combination, most frequently occur during typical use of cosmetic prosthetic fingers. As there are no dedicated standards for testing prosthetic fingers, the authors referred to ISO 178 [

22], which is the standard governing three-point bending tests, and ISO 604 [

23], which specifies the procedures for determining the compressive properties of plastics.

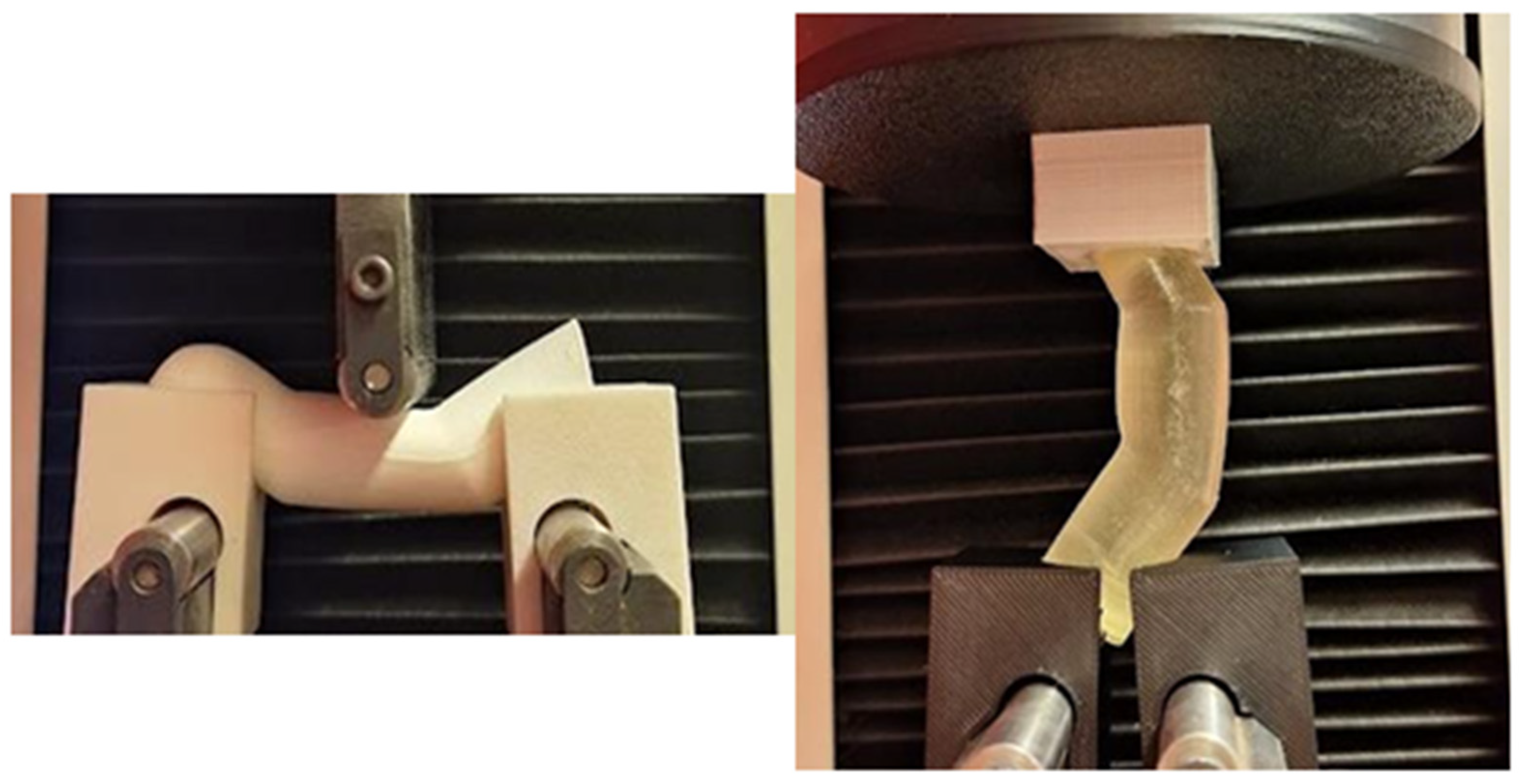

Due to the non-standard geometry of the test samples, it was necessary to design and fabricate custom auxiliary fixtures to prevent displacement or misalignment of the specimens during testing (

Figure 2). These fixtures were designed and additively manufactured using FFF method with ABS material.

The conducted tests were not fatigue tests and were not intended to induce failure of the specimens. However, by subjecting each sample to cyclic compressive loading, it was possible to assess whether the stress applied during the initial cycle had caused any internal damage. Such damage would manifest as variations in the mechanical response during subsequent loading cycles. The number of loading cycles was limited to 20. Each cycle lasted 20 s, with equal time allocated for achieving a 10 mm displacement and returning to the initial position.

In the evaluation of the functional quality of a hand prosthesis, the total mass of the device is an important parameter from the patient’s perspective. Likewise, the amount of material consumed is a key factor in the assessment of production costs. The mass of each sample was measured, after post-processing, using a WTC 200 laboratory balance (RADWAG, Toruń, Poland).

The manufacturing time for each sample within a given experimental series was determined based on the actual production duration, excluding preparation and post-processing times. These auxiliary times vary between different machines and additive manufacturing methods. Moreover, certain preparatory operations are performed only once for multiple production cycles. These differences will be discussed in the following sections, but are not included in the tabular data summary.

Each of the ten experimental series consisted of five identical samples, prepared for each type of mechanical strength test. For the Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) method, a Bambu Lab P1S printer (Bambu Lab, Shenzhen, China) was used in combination with FiberFlex 40D filament (Fiberlogy, Brzezie, Poland). This material is a thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) characterized by a Shore D hardness of 40. It is specifically intended for applications involving repeated bending and compressive forces. FiberFlex 40D does not possess official medical certification for use in medical devices. Nevertheless, TPE is broadly recognized for its safety in human contact applications; is non-toxic, hypoallergenic, and free from harmful substances.

The control codes for the printer were generated using Bambu Studio version 1.9.7.52 (Bambu Lab, Shenzhen, China), employing the default profile for flexible filament provided within the software. Across all sample series, several technological parameters were standardized: the layer height was set to 0.2 mm, and the first four and last four layers were printed with 100% infill. Support structures were generated automatically and printed at a density of 35%. The print speed was limited to a maximum nozzle deposition rate of 40 mm/s, with an additional volumetric speed cap of 3.6 mm3/s. The TPU extrusion temperature was set at 220 °C, with the build plate temperature maintained at 40 °C.

The variable parameters distinguishing individual series involved the degree of internal infill and the spatial orientation of the sample within the build volume, which directly affected the slicing strategy applied to the digital geometry (see

Table 1). Each sample was fabricated in a separate FFF build process. During post-processing, the support structures were manually removed from the samples using basic workshop tools.

To promote commensurate global stiffness across all sample series, infill parameters were determined a priori, informed by previous experience and exploratory trials rather than formal stiffness calibration. FFF samples were limited to 30% infill at a fixed shell thickness, as fully dense FFF parts exhibited substantially greater stiffness than photopolymer counterparts of identical outer geometry. These selections deliberately target functional equivalence in stiffness rather than numerical parity of infill, which is not directly comparable across additive manufacturing methods.

The samples fabricated using MSLA method were produced on a Phrozen Sonic Mini 8K resin printer (Phrozen, Taipei, Taiwan), employing the Engineering LCD Series Flex 63A photopolymer resin (FormFutura, Brzezie, Poland). The material does not possess medical certification; however, in its crosslinked form, it is not expected to pose a hazard to humans upon contact with the skin. The control code for the printer was generated using CHITUBOX software (CBD-Tech, Shenzhen, China), version 1.9.5. The layer thickness was set to 0.05 mm, with an initial exposure time of 60 s for the first layer and four transition layers. For all subsequent layers, the exposure time was reduced to 4 s.

In MSLA technology, the total printing time depends primarily on the number of layers, rather than the number of objects occupying the build platform. Consequently, all samples within a given series were manufactured in a single production run. After removal from the printer, the samples were washed in isopropyl alcohol and subjected to UV post-curing for five minutes.

Only two sample series were fabricated using the PolyJet method. This limitation resulted from the inability of the technology to produce parts with partial infill—PolyJet always generates fully solid components. However, it allows for material differentiation between the outer shell and the internal core. The sample geometry was intentionally simplified, lacking fine structural details. In the context of PolyJet technology, with a layer thickness of 18 μm, this simplification meant that there were no visual or mechanical differences when printing the samples in various orientations within the build chamber. Therefore, a horizontal orientation, as shown on the left side of

Figure 3, was selected to minimize build time.

All test samples within a given series were fabricated in a single production run, as—similar to MSLA—the total production time in PolyJet technology is primarily determined by the number of layers, rather than the number of parts on the build tray. The samples were printed using a J5 MediJet printer (Stratasys, Minnetonka, MN, USA), with control codes prepared in GrabCAD Print software version 1.102.9 (Stratasys, Minnetonka, MN, USA).

The elastic material used for sample fabrication was Elastico Clear (FLX934) (Stratasys, Minnetonka, MN, USA), while the support structures were printed using SUP710 (Stratasys, Minnetonka, MN, USA). Both materials are proprietary to the manufacturer and compatible exclusively with the closed material system of the J5 platform. Despite the Elastico Clear material not possessing medical certification, it is designed for applications involving limited skin contact. For sample series J, a 2 mm-thick outer shell was printed using the elastic material, while the internal volume was filled with the support material. After removal from the printer’s build chamber, the test samples were cleaned using a pressure washer. No additional UV post-curing was performed.

3. Results and Discussion

A total of 100 test samples were fabricated in the described study—50 for three-point bending tests and 50 for compression tests. No technical issues were observed during any of the manufacturing processes, and there was no need to interrupt production or repeat any fabrication runs. The time required to produce a single sample in each series is presented in

Table 2. The reported times are rounded to the nearest full minute and refer exclusively to the operation of the additive manufacturing machine.

For the series in which samples were fabricated sequentially, the production time for each process was identical after rounding—no variation in measured values was observed. Preparation and finishing times were excluded from the analysis.

Each sample was weighed in order to determine its mass, and the results are presented in

Table 3. Across all series, the authors observed good manufacturing repeatability. However, the lowest repeatability—determined based on the standard deviation of the measurement results—was observed for the FFF method. It should be noted that thermoplastic elastomers (TPE) are inherently more difficult to process than the most commonly used materials in FFF, which clearly affects the consistency of the fabrication process.

The effect of build orientation on mass was examined under the same manufacturing method and infill level, using two-sided Welch’s t-tests with Holm adjustment (α = 0.05; n = 5 per series). Orientation significantly affected mass in all pairs (adjusted p < 0.001). Mean differences were: A–B +0.373 g (+8.24%), C–D +0.244 g (+3.17%), E–F +0.022 g (+0.22%), and G–H +0.110 g (+0.64%), indicating orientation-dependent material usage despite fixed manufacturing method and infill. The I–J pair—differing in infill build strategy—also showed a statistically significant difference in mass.

All fabricated finger samples were deemed esthetically acceptable. In series A and C, characteristic surface artifacts typical of the FFF method were observed. These included visible distortions and irregularities on surfaces where the outlines of new layers extended beyond the contours of the previous ones, requiring support structures for stabilization (

Figure 4). With this specific build orientation in FFF, it is not possible to entirely eliminate such defects.

In the samples produced via the MSLA method, small pin-point support marks were observed as dots and slight surface protrusions. Although these formed a consistent pattern, they were located exclusively on the side of the finger facing the build platform during fabrication. This indicates that it is possible to orient the finger models in such a way that any visible marks are confined to the inner, less visible side of the finger, thus preserving the overall esthetic coherence of the part. It is also worth noting that cosmetic prosthetic hands are often used in conjunction with silicone cosmetic gloves. As a result, minor surface imperfections do not constitute a functional or visual defect in the context of everyday use. No surface defects or dimensional inaccuracies were observed in the samples produced using the PolyJet method.

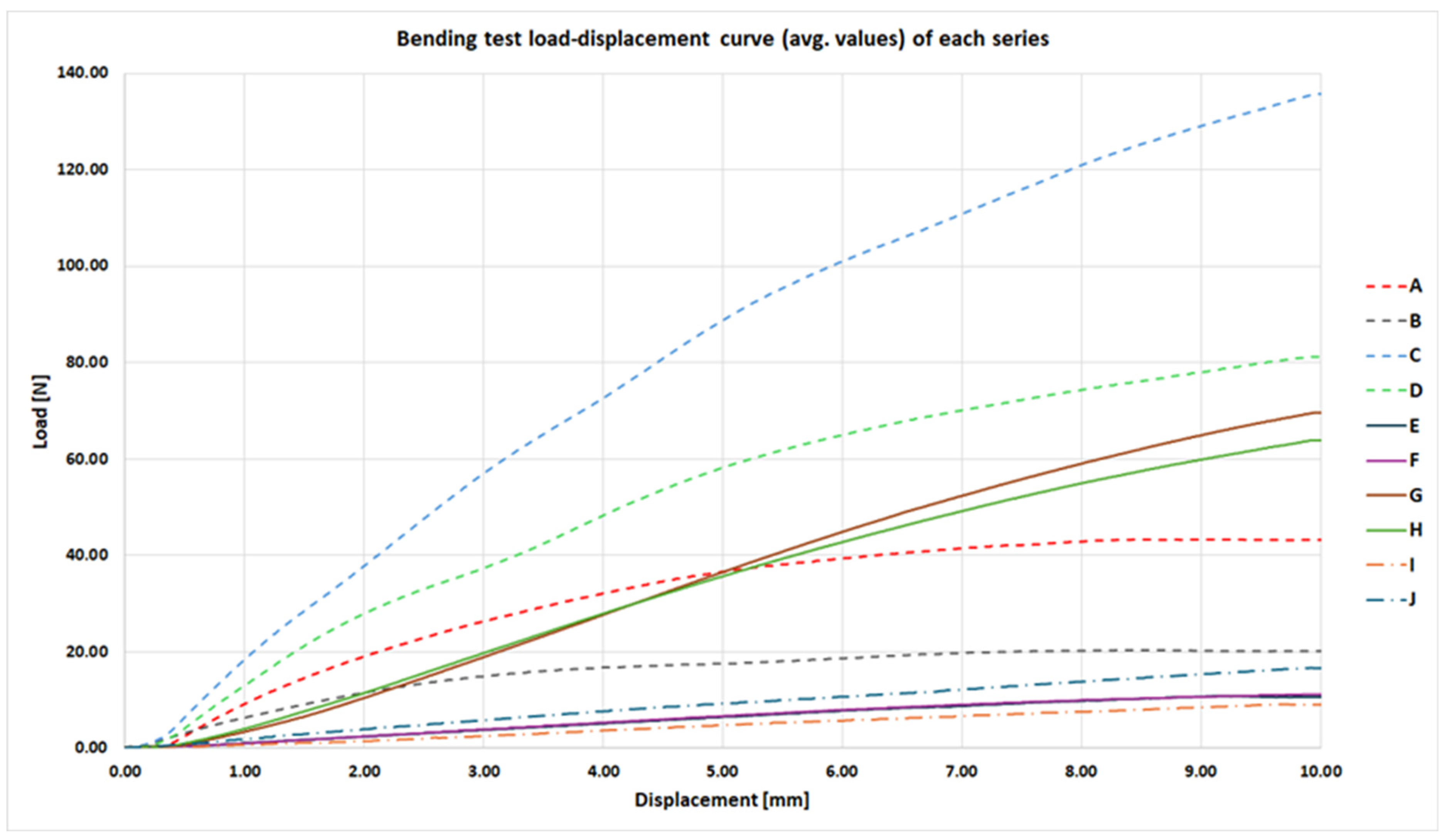

The bending strength tests were conducted at a loading rate of 5 mm/min, until a displacement of 10 mm between the support points was reached. The results, presented as average force–displacement curves, are shown in

Figure 5. None of the tested samples experienced structural failure during the tests.

The highest force required to reach the 10 mm deflection was recorded for series C, which consisted of samples produced using the FFF method with 30% infill, printed in a horizontal orientation within the build chamber. The remaining maximum values—calculated as the mean force across all samples within each series—are presented numerically in

Table 4. Across all series, differences in maximum bending load associated with the varied parameters were statistically significant, as verified using two-sided Welch’s t-tests with Holm adjustment (α = 0.05; n = 5 per series).

It is worth noting that the curves corresponding to series E and F are nearly identical. This indicates that the build orientation of MSLA-fabricated samples with 5% internal infill had no measurable effect on the evaluated mechanical parameter. Similarly, for MSLA samples with solid (monolithic) infill—series G and H—the force–displacement curves were highly comparable.

The performance advantage of MSLA samples fabricated in a horizontal orientation only began to manifest midway through the total measured displacement range and became more pronounced with increasing displacement. Both series produced using the PolyJet method, which were fabricated as fully solid parts, demonstrated a mechanical response comparable to the MSLA samples with 5% internal infill.

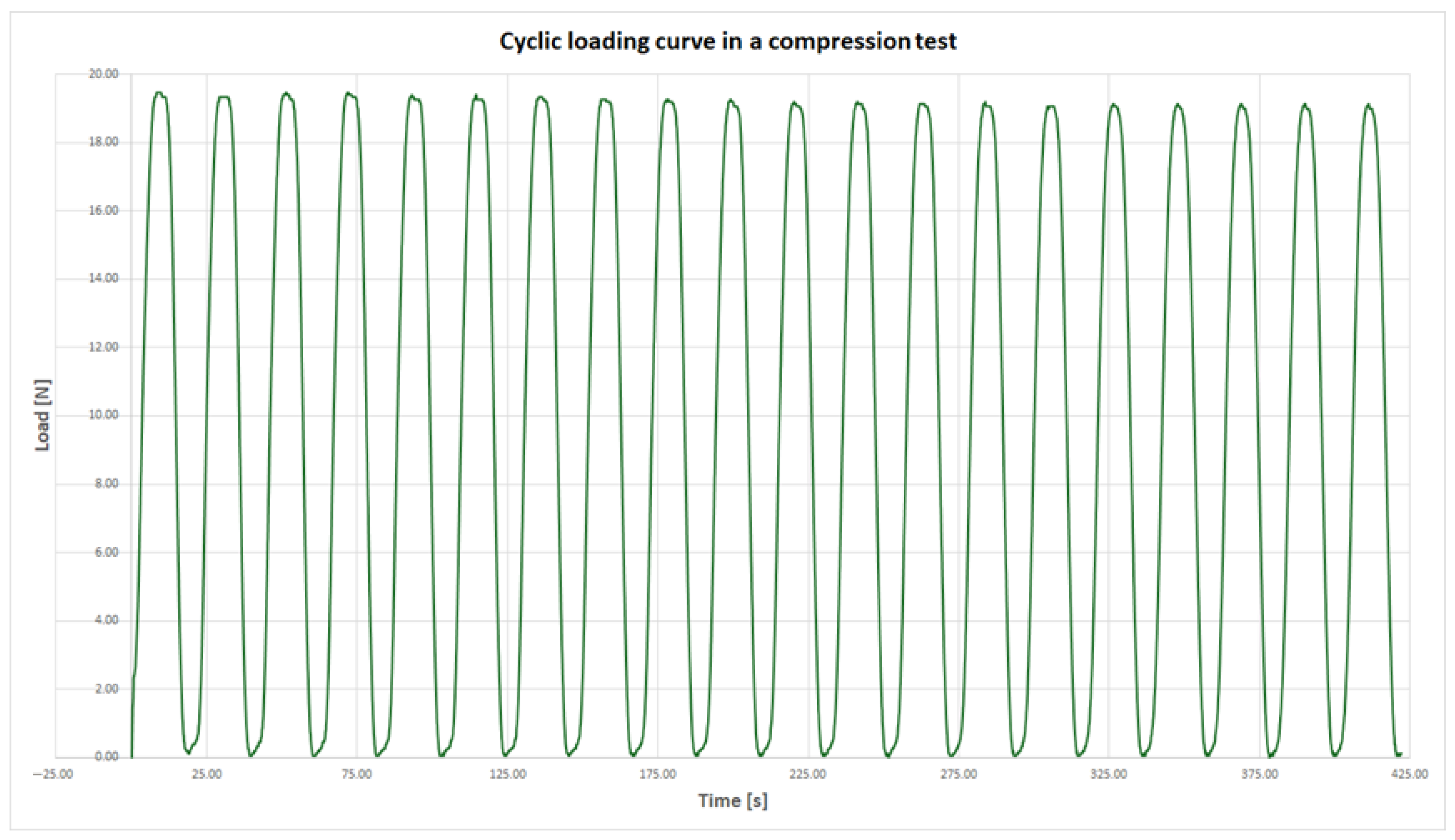

The compression strength tests were dynamic in nature and conducted at a displacement rate of 1 mm/s. None of the samples failed during testing; however, two distinct types of mechanical response were observed.

The first response type, exhibited by the majority of the experimental series, was characterized by a highly consistent maximum compressive force across all 20 loading cycles. The difference between the highest recorded force and the average force across all cycles was less than 5%. Notably, the peak value did not necessarily occur during the first cycle. An example of this behavior, based on results from series F, is presented in

Figure 6.

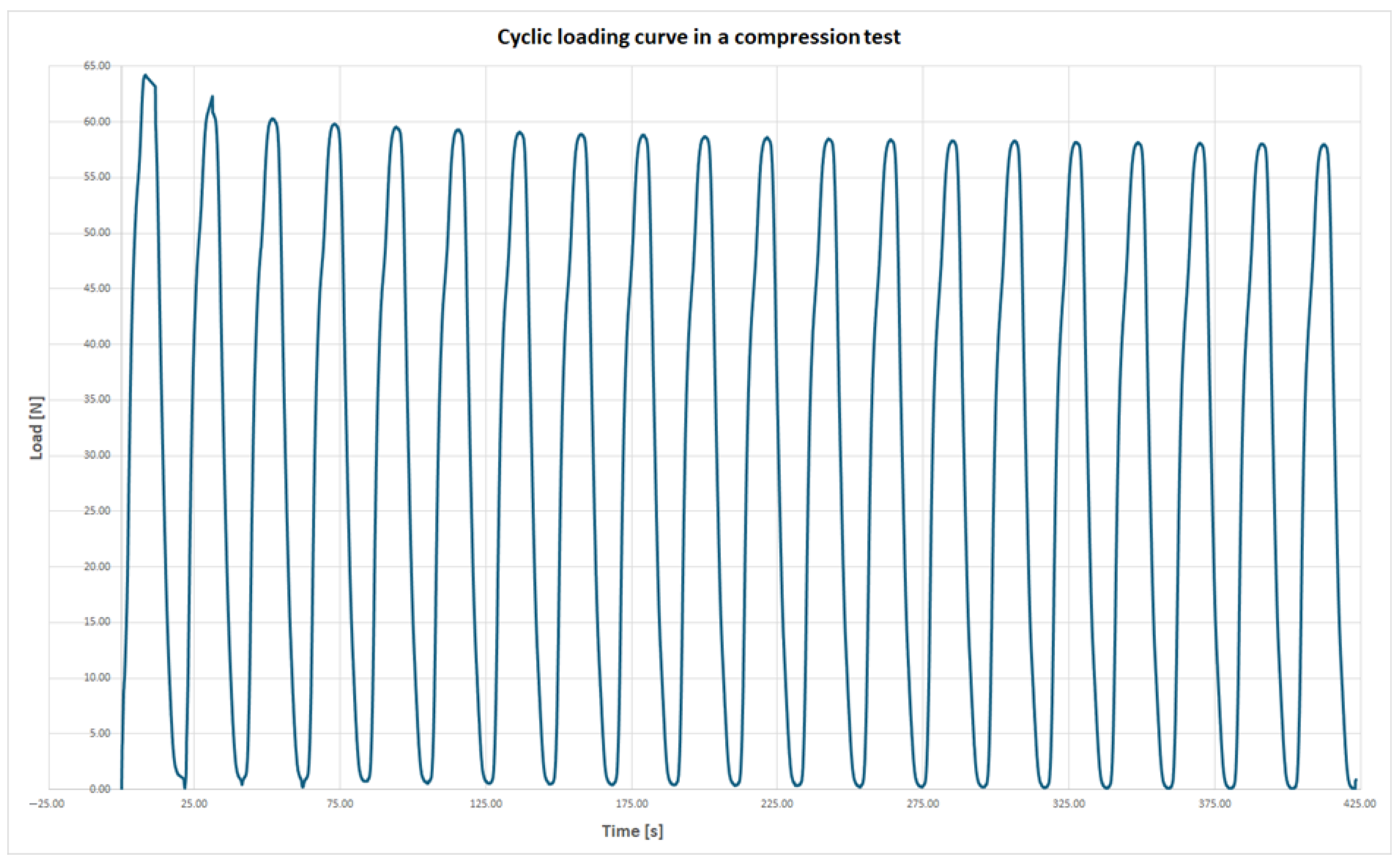

The second type of mechanical response under compressive loading was characterized by the highest force being recorded during the first cycle, followed by a progressive reduction in maximum force in subsequent cycles. This decline was most pronounced during the initial few cycles. This response type was observed in the following series: A, B, C, D, and J. An example of this behavior, based on the average force values from series A, is presented in

Figure 7.

It is important to note that within each affected series, all samples exhibited the same behavior. This consistency suggests that the phenomenon is related to the manufacturing method rather than to random individual defects or gross production errors.

In the case of series J, the internal core of the samples was made from the support material SUP710, which initially sustained higher loads but underwent plastic deformation and damage. As a result, the core could not carry the same loads in subsequent cycles. The difference between the force recorded in the first cycle and the average force across all cycles exceeded 20%, making it the most significant variation among all tested series.

Samples from series I, composed entirely of FLX934 material, maintained consistent mechanical performance across all loading cycles. For series A–D, the internal filament arrangement of the printed structures likely contributed to this phenomenon. Weaker inter-layer or intra-filament bonds failed during the initial loading phase, resulting in first-cycle forces exceeding the overall average by approximately 5% to 9%.

This behavior highlights an important consideration in the design of geometrically complex components: a structure may meet strength requirements under a single loading event but fail if subjected to an identical subsequent load. Therefore, attention must be paid to cumulative or repeated stress conditions in design validation.

Table 5 presents the results of the maximum force recorded during the dynamic compression test, as well as the average of the maximum values obtained across all loading cycles. For each series, the reported values were calculated as the mean of the corresponding responses from all individual samples, evaluated at identical points on the test timeline.

Only for the FFF method at 30% infill (series C and D) did build orientation not yield a statistically significant difference in compressive strength (Holm adjusted p = 0.591). All other comparisons were significant under the same test. This suggests that, at higher infill in FFF, the internal architecture and shell contribution may render compressive performance relatively orientation-insensitive—implying that orientation for such builds can be chosen based on other criteria.

In industrial practice, aside from product-related technical performance indicators and delivery lead time, the cost of production is a crucial factor. The proposed manufacturing methods differ significantly in terms of equipment acquisition costs, operational and maintenance expenses, and the cost of the processed materials used to produce the final part.

Since unit production costs fluctuate over time—being influenced by factors such as currency exchange rates, electricity prices, and labor costs—the authors decided to present only the relative cost ratio of manufacturing a single sample from each series. The cost estimation, summarized in

Table 6, includes equipment depreciation, electricity consumption, labor related to machine operation, and material usage.

It should be noted that in the case of resin-based methods (MSLA and PolyJet), the higher the utilization of the build platform per layer, the more favorable the cost ratio becomes for equipment amortization and energy consumption compared to the FFF method.

4. Conclusions

The results presented in this study demonstrate that various additive manufacturing methods can produce cosmetically acceptable upper limb prosthetic fingers with significantly different characteristics. Quantitatively, maximum bending loads ranged from 9 to 136 N (CV ≈ 0.5–3.1%), maximum compressive loads from 12 to 158 N (CV ≈ 2.2–6.2%), and sample mass from 4 to 22 g (CV ≈ 0.01–0.40%) across configurations; no specimen fractured under the applied bending or compression protocols. When designing a specific prosthesis, it is therefore essential to define clear requirements related to its mass and mechanical properties. For instance, pediatric prostheses must balance the missing limb’s weight to prevent uneven spinal loading. Fingers for purely cosmetic prostheses have minimal strength needs, while those bearing body weight demand high strength. Prosthetic fingers for grasping require durability combined with fine motor control.

Despite the identification of certain esthetic imperfections, all of the evaluated additive manufacturing techniques are applicable to the production of individualized cosmetic upper limb prostheses. Although resin-based methods such as MSLA and PolyJet enable the fabrication of components with higher surface precision, they are generally less attractive in terms of production time and cost compared to the FFF method. Furthermore, FFF technology offers greater flexibility in tailoring prosthetic properties through the adjustment of process parameters. FFF machines also typically feature larger build volumes, allowing for the fabrication of complete hand or forearm prostheses in a single build, without the need for part segmentation.

The absence of clearly defined standards and testing protocols for cosmetic prostheses complicates the objective evaluation and comparison of different technical solutions or their individual components. The authors recognize that this issue contributes to the fragmented nature of current research and the limited comparability of results across different products and manufacturing methods. Nevertheless, they believe that the data presented herein can support the evaluation of prosthetic designs as complete systems and assist in defining practical requirements for the additive manufacturing of cosmetic upper limb prostheses tailored to different patient groups and levels of activity.

As a continuation of this research, future studies should incorporate dedicated fatigue testing involving a high number of loading cycles to assess the long-term durability of prosthetic components under repeated stress conditions, which was not addressed in the present study. Additionally, further investigation could explore alternative additive manufacturing techniques not included in this work—such as Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) or emerging silicone-based printing methods—to broaden the comparative analysis and better understand their potential for producing flexible, skin-like prosthetic elements.