Success from the Spot: Insights into Penalty Performance in Elite Women’s Football

Abstract

1. Introduction

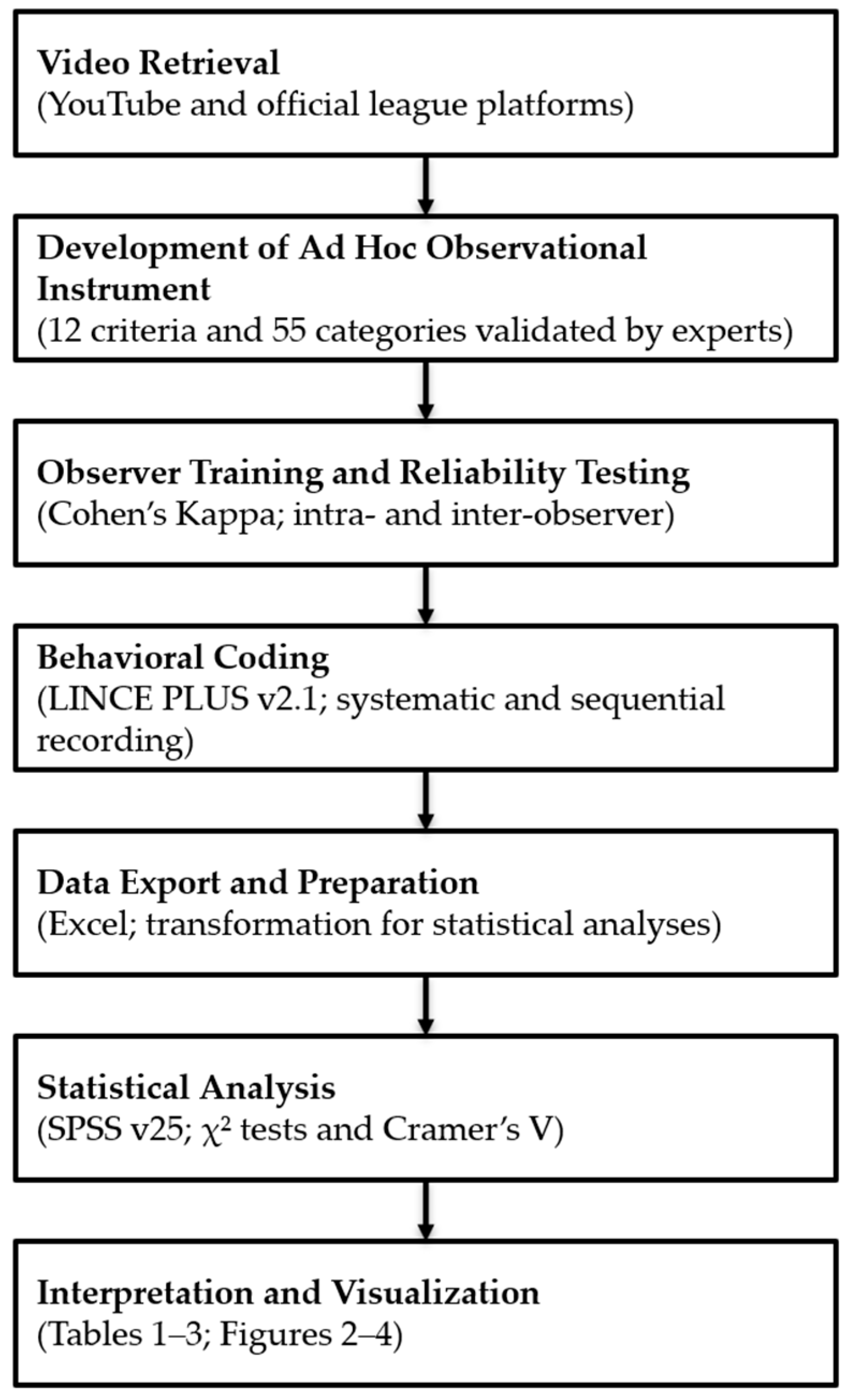

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

| Criteria | Description | n | % | SR | χ2 GOF | χ2 Independence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| League | Liga F | 156 | 65 | 80.1 | χ2 =21.600 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 0.024; p = 0.878; V = 0.01 |

| Women’s Super League | 84 | 35 | 81 | |||

| Stadium | The team that kicks plays as the home team | 144 | 60 | 85.4 | χ2 = 9.600 p = 0.002 | χ2 = 5.715; p = 0.017 *; V = 0.15 |

| The team that kicks plays as the away team | 96 | 40 | 72.9 | |||

| Time | The penalty is kicked at 0–15 min | 22 | 9.2 | 77.3 | χ2 = 17.650 p = 0.003 | χ2 = 3.797; p = 0.579; V = 0.13 |

| The penalty is kicked at 16–30 min | 32 | 13.3 | 87.5 | |||

| The penalty is kicked at 31–45+ min | 39 | 6.3 | 71.8 | |||

| The penalty is kicked at 46–60 min | 52 | 21.7 | 80.8 | |||

| The penalty is kicked at 61–75 min | 42 | 17.5 | 85.7 | |||

| The penalty is kicked at 76–90+ min | 53 | 22.1 | 79.2 | |||

| Result | The team that kicks the penalty is tying | 104 | 43.3 | 84.6 | χ2 = 11.425 p = 0.003 | χ2 = 7.450; p = 0.024 *; V = 0.18 |

| The team that kicks the penalty is losing | 63 | 26.3 | 85.7 | |||

| The team that kicks the penalty is winning | 73 | 30.4 | 69.9 | |||

| Scoreboard | The team that takes the penalty is tying the match. | 104 | 43.3 | 84.6 | χ2 = 201.233 p < 0.001 | χ2 =12.663; p = 0.049 *; V = 0.23 |

| The team that kicks the penalty is losing by 1 goal. | 41 | 17.1 | 85.4 | |||

| The team that kicks the penalty is losing by 2 goals. | 15 | 6.3 | 86.7 | |||

| The team that kicks the penalty is losing by 3+ goals. | 7 | 2.9 | 85.7 | |||

| The team that kicks the penalty is winning by 1 goal. | 42 | 17.5 | 66.7 | |||

| The team that kicks the penalty is winning by 2 goals. | 23 | 9.6 | 65.2 | |||

| The team that kicks the penalty is winning by 3+ goals. | 8 | 3.3 | 100 | |||

| Laterality | The kicking player is right—footed | 188 | 78.3 | 80.9 | χ2 = 77.067 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 0.104; p = 0.747; V = 0.02 |

| The kicking player is left—footed | 52 | 21.7 | 78.8 | |||

| Run—up to the Kick | The kicker takes fewer than three steps before striking the ball | 22 | 9.2 | 72.7 | χ2 = 343.75 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 5.334; p = 0.069; V = 0.15 |

| The kicker takes three or more steps before striking the ball | 215 | 89.6 | 81.9 | |||

| The kicker clearly pauses during the run—up | 3 | 1.3 | 33.3 | |||

| Goalkeeper actions prior to the kick | Small sideways steps in the center of the goal without combining them with arm movements (legs only) | 12 | 5 | 66.7 | χ2 = 257.000 p < 0.001 | χ2 = 4.879; p = 0.559; V = 0.14 |

| Exaggerated lateral movement to the kicker’s right side. | 9 | 3.8 | 77.8 | |||

| Exaggerated lateral movement to the kicker’s left side. | 9 | 3.8 | 100 | |||

| Goalkeeper remains stationary in the center of the goal without moving. | 110 | 45.8 | 82.7 | |||

| Exaggerated movement of both arms and legs in the center of the goal (without displacement). | 8 | 3.3 | 75 | |||

| Arm movements only in the center of the goal (without displacement). | 33 | 13.8 | 81.8 | |||

| Small jumps in the center of the goal (without displacement). | 59 | 24.6 | 76.3 | |||

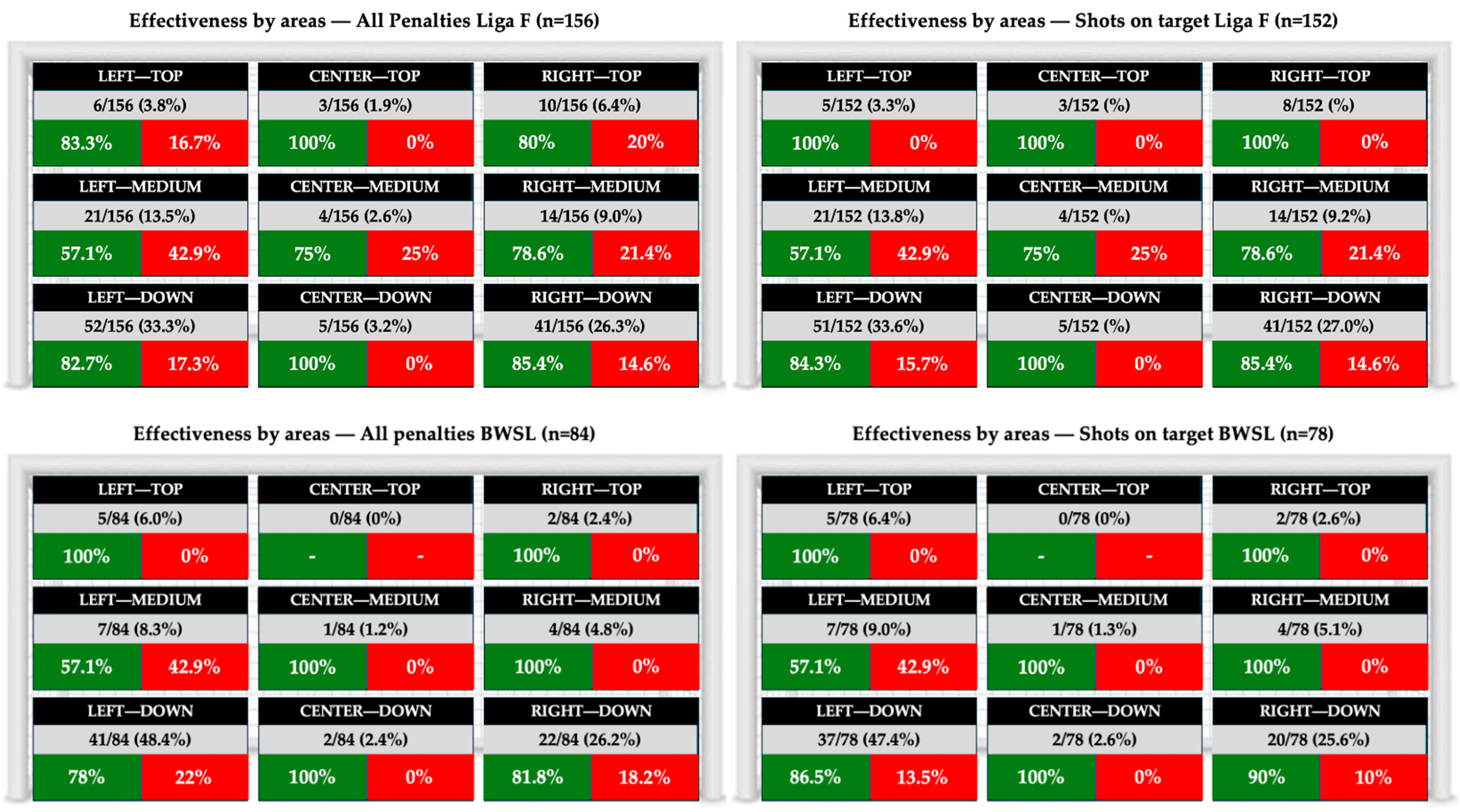

| Direction—goal (depending on the view of the kicker) | Left—Top | 11 | 4,6 | 90.9 | χ2 = 287.775 p < 0.001 | χ2 =13.551; p = 0.094; V = 0.26 |

| Left—Medium height | 28 | 11.7 | 57.1 | |||

| Left—Down | 93 | 38.8 | 60.6 | |||

| Centre—Top | 3 | 1.3 | 100 | |||

| Centre—Medium height | 5 | 2.1 | 80 | |||

| Centre—Down | 7 | 2.9 | 100 | |||

| Right—Top | 12 | 5.0 | 83.3 | |||

| Right—Medium height | 18 | 7.5 | 83.3 | |||

| Right—Down | 63 | 26.3 | 84.1 | |||

| Direction— laterality (depending on the view of the kicker) | Kicker—Top | 15 | 6.3 | 93.3 | χ2 = 284.700 p < 0.001 | χ2 =11.793; p = 0.161; V = 0.25 |

| Kicker—Medium | 29 | 12.6 | 62.1 | |||

| Kicker—Down | 91 | 37.9 | 84.6 | |||

| Middle—Top | 3 | 1.3 | 100 | |||

| Middle—Medium | 5 | 2.1 | 80 | |||

| Middle—Down | 7 | 2.9 | 100 | |||

| Far—Top | 9 | 3.8 | 77.8 | |||

| Far—Medium | 16 | 6.7 | 81.3 | |||

| Far—Down | 65 | 27.1 | 76.9 | |||

| Penalty Outcome (detailed) | The penalty ends in goal | 193 | 80.4 | - | χ2 = 243.975 p < 0.001 | - |

| The penalty is saved | 37 | 15.4 | - | |||

| The penalty is missed | 10 | 4.2 | - | |||

| Penalty Outcome (binary) | Goal | 193 | 80.4 | - | χ2 = 88.817 p < 0.001 | - |

| Error | 47 | 19.6 | - |

| LIGA F | WSL | Interleague | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Description | n | % | SR | χ2 GOF | χ2 Independence | n | % | SR | χ2 GOF | χ2 Independence | χ2 Independence |

| Stadium | Home team | 90 | 57.7 | 85.6 | χ2 = 3.692 | χ2 = 3.935; p = 0.047 *; V = 0.16 | 54 | 64.3 | 85.2 | χ2 = 6.857 | χ2 = 1.757; p = 0.185; V = 0.14 | χ2 = 0.989; p = 0.320; V = 0.06 |

| Away team | 66 | 42.3 | 72.7 | p = 0.055 | 30 | 35.7 | 73.3 | p = 0.009 | ||||

| Time | 0–15 min | 14 | 9 | 78.6 | χ2 = 10.385 | χ2 = 3.053; p = 0.692; V = 0.14 | 8 | 9.5 | 75 | χ2 = 10.429 | χ2 = 2.049; p = 0.842; V = 0.16 | χ2 = 3.086; p = 0.687; V = 0.11 |

| 16–30 min | 21 | 13.5 | 90.5 | p = 0.065 | 11 | 13.1 | 81.8 | p = 0.064 | ||||

| 31–45+ min | 30 | 19.2 | 73.3 | 9 | 10.7 | 66.7 | ||||||

| 46–60 min | 32 | 20.5 | 81.3 | 20 | 23.8 | 80 | ||||||

| 61–75 min | 26 | 16.7 | 84.6 | 16 | 19.0 | 87.5 | ||||||

| 76–90+ min | 33 | 21.2 | 75.8 | 20 | 23.8 | 85 | ||||||

| Result | Tying | 68 | 43.6 | 83.8 | χ2 = 7.423 | χ2 = 3.230; p = 0.199; V = 0.14 | 36 | 42.9 | 86.1 | χ2 = 4.571 | χ2 = 4.797; p = 0.091; V = 0.24 | χ2 = 0.661; p = 0.718; V = 0.05 |

| Losing | 43 | 27.6 | 83.7 | p = 0.024 | 20 | 23.8 | 90 | p = 0.102 | ||||

| Winning | 45 | 28.8 | 71.1 | 28 | 33.3 | 67.9 | ||||||

| Scoreboard | Tying | 68 | 43.6 | 83.8 | χ2 = 149.667 | χ2 = 8.025; p = 0.236; V = 0.23 | 36 | 42.9 | 86.1 | χ2 = 63.000 | χ2 = 9.114; p = 0.167; V = 0.33 | χ2 = 14.734; p = 0.022 *; V = 0.25 |

| Losing by 1 goal. | 34 | 21.8 | 82.4 | p < 0.001 | 7 | 8.3 | 100 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Losing by 2 goals | 6 | 2.8 | 100 | 9 | 10.7 | 77.8 | ||||||

| Losing by 3+ goals | 3 | 1.9 | 66.7 | 4 | 4.8 | 100 | ||||||

| Winning by 1 goal | 29 | 18.6 | 65.5 | 13 | 15.5 | 69.2 | ||||||

| Winning by 2 goals | 11 | 7.1 | 72.7 | 12 | 14.3 | 58.3 | ||||||

| Winning by 3+ goals | 5 | 3.2 | 100 | 3 | 3.6 | 100 | ||||||

| Laterality | Right—footed | 117 | 75 | 78.6 | χ2 = 39.000 | χ2 = 0.658; p = 0.417; V = 0.07 | 71 | 84.5 | 84.5 | χ2 = 40.048 | χ2 = 3.759; p = 0.053; V = 0.21 | χ2 = 2.918; p = 0.088; V = 0.11 |

| Left—footed | 39 | 25 | 84.6 | p < 0.001 | 13 | 15.5 | 61.5 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Run—up to the Kick | Less three steps | 16 | 10.3 | 62.5 | χ2 = 210.038 | χ2 = 8.066; p = 0.018 *; V = 0.23 | 6 | 7.1 | 100 | χ2 = 61.714 | χ2 = 1.520; p = 0.218; V = 0.14 | χ2 = 2.347; p = 0.309; V = 0.10 |

| Three or more steps | 137 | 87.8 | 83.2 | p < 0.001 | 78 | 92.9 | 79.5 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Pauses during the run—up | 3 | 1.9 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Goalkeeper actions prior to the kick | Side steps center (legs) | 7 | 4.5 | 42.9 | χ2 = 170.487 | χ2 = 15.616; p = 0.016 *; V = 0.32 | 5 | 6.0 | 100 | χ2 = 87.000 | χ2 = 7.326; p = 0.292; V = 0.30 | χ2 = 6.236; p = 0.397; V = 0.16 |

| Move right (exaggerated) | 6 | 3.8 | 100 | p < 0.001 | 3 | 3.6 | 33.3 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Move left (exaggerated) | 9 | 5.8 | 100 | 1 | 1.2 | 100 | ||||||

| Stationary center | 74 | 47.4 | 85.1 | 35 | 41.7 | 77.1 | ||||||

| Arms & legs center | 4 | 2.6 | 50 | 4 | 4.8 | 100 | ||||||

| Arms only center | 23 | 14.7 | 82.6 | 10 | 11.9 | 80 | ||||||

| Jumps center | 33 | 21.2 | 69.7 | 26 | 31.0 | 84.6 | ||||||

| Direction—goal | Left—Top | 6 | 3.8 | 83.3 | χ2 = 144.462 | χ2 = 9.999; p = 0.265; V = 0.29 | 5 | 6.0 | 100 | χ2 = 131.619 | χ2 = 6.103; p = 0.528; V = 0.27 | χ2 = 10.171; p = 0.253; V = 0.21 |

| Left—Medium height | 21 | 13.5 | 57.1 | p < 0.001 | 7 | 8.3 | 57.1 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Left—Down | 52 | 33.3 | 82.7 | 41 | 48.8 | 78 | ||||||

| Centre—Top | 3 | 1.9 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Centre—Medium height | 4 | 2.6 | 75 | 1 | 1.2 | 100 | ||||||

| Centre—Down | 5 | 3.2 | 100 | 2 | 2.4 | 100 | ||||||

| Right—Top | 10 | 6.4 | 80 | 2 | 2.4 | 100 | ||||||

| Right—Medium height | 14 | 9.0 | 78.6 | 4 | 4.8 | 100 | ||||||

| Right—Down | 41 | 26.3 | 85.4 | 22 | 26.2 | 81.8 | ||||||

| Direction— laterality | Kicker—Top | 10 | 6.4 | 90 | χ2 = 149.423 | χ2 = 8.721; p = 0.366; V = 0.27 | 5 | 6.0 | 100 | χ2 = 118.667 | χ2 = 6.664; p = 0.465; V = 0.28 | χ2 = 6.189; p = 0.626; V = 0.16 |

| Kicker—Medium | 22 | 4.1 | 63.6 | p < 0.001 | 7 | 8.3 | 57.1 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Kicker—Down | 53 | 34 | 86.8 | 38 | 45.2 | 81.6 | ||||||

| Middle—Top | 3 | 1.9 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Middle—Medium | 4 | 2.6 | 75 | 1 | 1.2 | 100 | ||||||

| Middle—Down | 5 | 3.2 | 100 | 2 | 2.4 | 100 | ||||||

| Far—Top | 7 | 4.5 | 71.4 | 2 | 2.4 | 100 | ||||||

| Far—Medium | 11 | 7.1 | 72.7 | 5 | 6.0 | 100 | ||||||

| Far—Down | 41 | 26.3 | 78 | 24 | 28.6 | 75 | ||||||

| Penalty Outcome (detailed) | The penalty ends in goal | 125 | 80.1 | — | χ2 = 158.808 | — | 68 | 81.0 | — | χ2 = 86.000 | — | χ2 = 3.786; p = 0.151; V = 0.13 |

| The penalty is saved | 27 | 17.3 | — | p < 0.001 | 10 | 11.9 | — | p < 0.001 | ||||

| The penalty is missed | 4 | 2.6 | — | 6 | 7.1 | — | ||||||

| Penalty Outcome (binary) | Goal | 125 | 80.1 | — | χ2 = 56.641 | — | 68 | 81.0 | — | χ2 = 32.190 | — | χ2 = 0.024; p = 0.878; V = 0.01 |

| Error | 31 | 19.9 | — | p < 0.001 | 16 | 19.0 | — | p < 0.001 | ||||

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Effectiveness

4.2. Stadium Factor

4.3. Match Timing

4.4. Match Status

4.5. Laterality

4.6. Shot Placement (Goal Direction)

4.7. Laterality-Related Placement

4.8. Predictive Interpretation

4.9. Practical Applications

4.10. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGarry, T.; Franks, I.M. On Winning the Penalty Shoot-out in Soccer. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordet, G.; Hartman, E.; Visscher, C.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M. Kicks from the Penalty Mark in Soccer: The Roles of Stress, Skill, and Fatigue for Kick Outcomes. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Eli, M.; Azar, O.H. Penalty Kicks in Soccer: An Empirical Analysis of Shooting Strategies and Goalkeepers’ Preferences. Soccer Soc. 2009, 10, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.; Volossovitch, A. Multifactorial Analysis of Football Penalty Kicks in the Portuguese First League: A Replication Study. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 18, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Littman, P.; Beato, M. Investigating Inter-League and Inter-Nation Variations of Key Determinants for Penalty Success across European Football. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2020, 20, 892–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.; Volossovitch, A.; Duarte, R. Penalty Kick Outcomes in UEFA Club Competitions (2010–2015): The Roles of Situational, Individual and Performance Factors. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2016, 16, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, M.; de Waal, S.; Kraak, W. In-Match Penalty Kick Analysis of the 2009/10 to 2018/19 English Premier League Competition. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2020, 21, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Lage, I.; Argibay-González, J.C.; Bezerra, P.; Cidre-Fuentes, P.; Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, X.; Gutiérrez-Santiago, A. Analysis of Penalty Kick Performance in the Spanish Football League: A Longitudinal Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidre-Fuentes, P.; González-Harcevnicow, M.A.; Prieto-Lage, I. Laterality, Shot Direction and Spatial Asymmetry in Decisive Penalty Kicks: Evidence from Elite Men’s Football. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordet, G.; Hartman, E.; Sigmundstad, E. Temporal Links in Penalty Shootouts. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furley, P.; Noël, B.; Memmert, D. Attention towards the Goalkeeper and Distraction during Penalty Shootouts in Association Football: A Retrospective Analysis of Penalty Shootouts from 1984 to 2012. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navia, J.A.; van der Kamp, J.; Avilés, C.; Aceituno, J. Self-Control in Aiming Supports Coping With Psychological Pressure in Soccer Penalty Kicks. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkschulte, M.; Wunderlich, F.; Furley, P.; Memmert, D. The Obligation to Succeed When It Matters the Most–The Influence of Skill and Pressure on the Success in Football Penalty Kicks. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 65, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Eli, M.; Azar, O.H.; Ritov, I.; Keidar-Levin, Y.; Schein, G. Action Bias among Elite Soccer Goalkeepers: The Case of Penalty Kicks. J. Econ. Psychol. 2007, 28, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, M.; Button, C.; Davids, K. Availability of Advance Visual Information Constrains Association-Football Goalkeeping Performance during Penalty Kicks. Perception 2010, 39, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelsbergh, G.J.P.; Williams, A.M.; Van Der Kamp, J.; Ward, P. Visual Search, Anticipation and Expertise in Soccer Goalkeepers. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.R.; Patching, G.R. Goal Side Selection of Penalty Shots in Soccer: A Laboratory Study and Analyses of Men’s World Cup Shoot-Outs. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2021, 128, 2279–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, M.; Memmert, D. Goal-Side Selection in Soccer Penalty Kicking When Viewing Natural Scenes. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Botella, M.; Palao, J.M. Relationship between Laterality of Foot Strike and Shot Zone on Penalty Efficacy in Specialist Penalty Takers. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2007, 7, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palao, J.M.; López-Montero, M.; López-Botella, M. Relación Entre Eficacia, Lateralidad y Zona de Lanzamiento Del Penalti En Función Del Nivel de Competición En Fútbol. (Relationship between Efficacy, Laterality of Foot Strike, and Shot Zone of the Penalty in Relation to Competition Level in Soccer). RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Del Deport. 2010, 6, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappori, P.-A.; Levitt, S.; Groseclose, T. Testing Mixed-Strategy Equilibria When Players Are Heterogeneous: The Case of Penalty Kicks in Soccer. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1138–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Huerta, I. Professionals Play Minimax. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2003, 70, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIFA. FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023TM Technical Report; Fédération Internationale de Football Association: Zurich, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Avugos, S.; Azar, O.H.; Sher, E.; Gavish, N.; Bar-Eli, M. Detecting Patterns in the Behaviour of Goalkeepers and Kickers in the Penalty Shootout: A between-Gender Comparison among Score Situations. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 21, 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, L. Mixed-Strategy Equilibria and Gender Differences:The Soccer Penalty Kick Game. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.M. Gender Differences in the Determinants of Choking under Pressure: Evidence from Penalty Kicks in Soccer. Soc. Sci. Q. 2024, 105, 1296–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, M.T.; Blanco-Villaseñor, A.; Losada, J.L.; Portell, M. Pautas Para Elaborar Trabajos Que Utilizan La Metodología Observacional. Anu. Psicol. 2018, 48, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, M.T.; Blanco-Villaseñor, A.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; Losada-López, J.L. Observational Designs: Their Suitability and Application in Sports Psychology. Cuad. Psicol. Deport. 2011, 11, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Barbero, J.R.; Lapresa, D.; Arana, J.; Anguera, M.T. An Observational Analysis of Kicker–Goalkeeper Interaction in Penalties between National Football Teams in International Competitions. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2023, 23, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Fernández, A.; Camerino, O.; Iglesias, X.; Anguera, M.T.; Castañer, M. LINCE PLUS Software for Systematic Observational Studies in Sports and Health. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 54, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, J.R.; Lapresa Ajamil, D.; Arana, J.; Anguera, M.T. Sequential Analysis of the Interaction between Kicker and Goalkeeper in Penalty Kicks. Cuad. Psicol. Deport. 2024, 24, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iván-Baragaño, I.; Ardá, A.; Anguera, M.T.; Losada, J.L.; Maneiro, R. Future Horizons in the Analysis of Technical-Tactical Performance in Women’s Football: A Mixed Methods Approach to the Analysis of in-Depth Interviews with Professional Coaches and Players. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1128549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Estévez, C.; Prieto-Lage, I.; Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, X.; Rodríguez-Crespo, M.; Gutiérrez-Santiago, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Santiago, A. Analysis and Successful Patterns in One-Possession Games During the Last Minute in the Women’s EuroLeague. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Lage, I.; Paramés-González, A.; Torres-Santos, D.; Argibay-González, J.C.; Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, X.; GutiérrezSantiago, A. Match Analysis and Probability of Winning a Point in Elite Men’s Singles Tennis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Weighted Kappa: Nominal Scale Agreement with Provision for Scaled Disagreement of Partial Credit. Psychol. Bull. 1968, 70, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- van Hemert, R.; van der Kamp, J.; Hartman, E. The Influence of Situational Constraints on In-Game Penalty Kicks in Soccer. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; van der Kamp, J.; Kemperman, K.; de Jong, I.; Caso, S. An Investigation into the Effect of Audiences on the Soccer Penalty Kick. Sci. Med. Footb. 2025, 9, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, A.; Christensen, O.H.; van den Tillaar, R. Effect of Instruction and Target Position on Penalty Kicking Performance in Soccer. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | League | χ2 (Independence) | p | Cramer’s V | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stadium (home vs. away) | Liga F | 3.935 | 0.047 | 0.16 | Small |

| Result (winning/tying/losing) | Both | 7.450 | 0.024 | 0.18 | Small |

| Scoreboard (goal difference) | Both | 12.663 | 0.049 | 0.23 | Small |

| Run-up length (<3 vs. ≥3 steps) | Liga F | 8.066 | 0.018 | 0.23 | Small |

| Goalkeeper actions before the kick | Liga F | 15.616 | 0.016 | 0.32 | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cidre-Fuentes, P.; Gutiérrez-Santiago, A.; Prieto-Lage, I. Success from the Spot: Insights into Penalty Performance in Elite Women’s Football. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11678. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111678

Cidre-Fuentes P, Gutiérrez-Santiago A, Prieto-Lage I. Success from the Spot: Insights into Penalty Performance in Elite Women’s Football. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11678. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111678

Chicago/Turabian StyleCidre-Fuentes, Pablo, Alfonso Gutiérrez-Santiago, and Iván Prieto-Lage. 2025. "Success from the Spot: Insights into Penalty Performance in Elite Women’s Football" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11678. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111678

APA StyleCidre-Fuentes, P., Gutiérrez-Santiago, A., & Prieto-Lage, I. (2025). Success from the Spot: Insights into Penalty Performance in Elite Women’s Football. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11678. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111678