Unraveling the Dynamics of Digital Inclusion: Exploring the Third-Level Digital Divide Among Older Adults in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Objectives of the Third-Level Digital Divide: The Relationship Between Older Adults and Digital Inclusion

2.2. Photography and Visual Narrative: From Youth Exuberance to Older Adults’ Empowerment

2.3. Social Identity and Digital Inclusion: A Dual Bridge Between Emotions and Behavior

2.4. Research Gaps and Theoretical Positioning: The Equalizing Role of the Photographic Medium

3. Research Methods

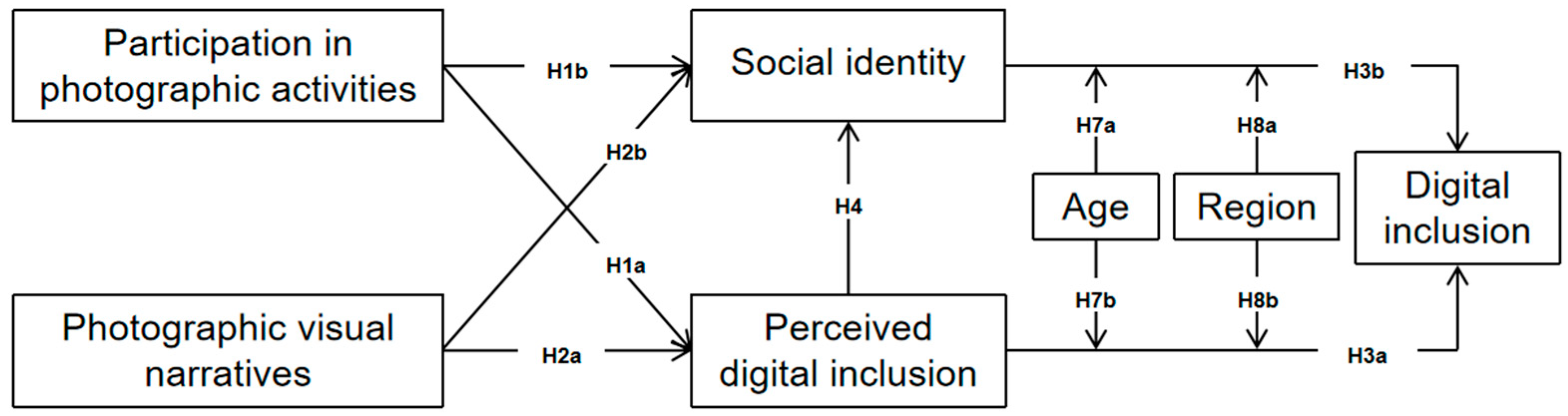

3.1. Models and Scales

3.2. Acquisition and Processing of the Sample Data

3.3. Research Objects

3.4. Data Cleaning and Sample Description

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2.1. Reliability Analysis

4.2.2. Validity Analysis

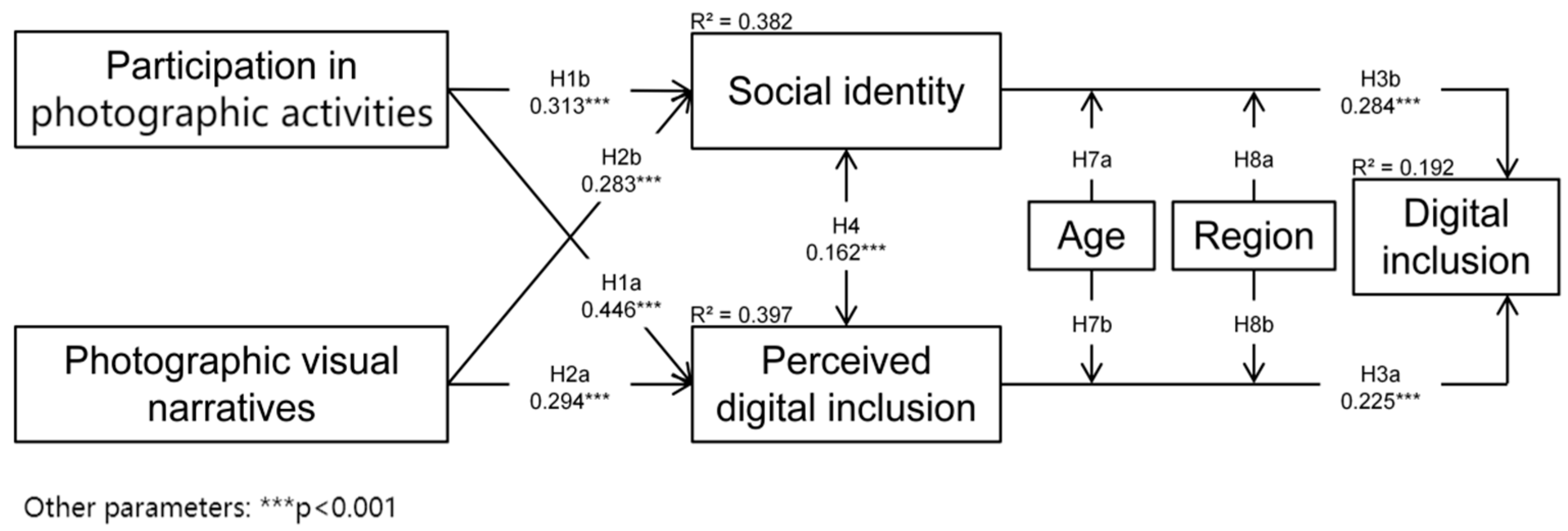

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing (H1–H8)

4.3.1. Common Method Variance

4.3.2. Structural Equation Model Analysis

4.3.3. Mediating Effect Analysis

4.3.4. Modulation Effect Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Contributions

6.1.1. Theoretical Advances in Media Specificity: From Generic “IT Use” to an “Image-Recognition” Micro-Loop

6.1.2. Directional Restatement of Process Mechanisms: Defining “Perceived Digital Inclusion” as the Affective Substrate of Social Identity

6.1.3. The “Equalizer” Proposition and Cross-Group Robustness: From Demographic Differences to a Practice-Centered Universal Pathway

6.2. Future Development Directions

6.2.1. Enhancing Sensitivity to Time and Context

6.2.2. Refining the “Spectrum of Photographic Activity” and Testing Shallow-to-Deep Transfer

6.2.3. Strengthening External Generalizability and Robustness of Evidence

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohan, R.; Saleem, F.; Voderhobli, K.; Sheikh-Akbari, A. Ensuring Sustainable Digital Inclusion among the Elderly: A Comprehensive Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzi, S.; Orton, L.; Buckner, S.; Bruce, N.; Pope, D. How Is Respect and Social Inclusion Conceptualised by Older Adults in an Aspiring Age-Friendly City? A Photovoice Study in the North-West of England. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, E.; Parnell Johnson, S.; Higgs, P.; Martin, W.; Morgan-Trimmer, S.; Burton, A.; Poppe, M.; Cooper, C. Nature As a “Lifeline”: The Power of Photography When Exploring the Experiences of Older Adults Living with Memory Loss and Memory Concerns. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossio, D.; McCosker, A. Reluctant Selfies: Older People, Social Media Sharing and Digital Inclusion. Continuum 2021, 35, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokeit, H.; Blochwitz, D. Neuro-aesthetics and the Iconography in Photography. PsyCh J. 2020, 9, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamprese, J.A. Adult Learning and Education in Digital Environments: Learning from Global Efforts to Promote Digital Literacy and Basic Skills of Vulnerable Populations. Adult Learn. 2024, 35, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, F.; Suomi, R. Elderly Forgotten? Digital Exclusion in the Information Age and the Rising Grey Digital Divide. Inquiry 2022, 59, 00469580221096272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddick, C.; Enriquez, R.; Harris, R.; Flores, J. Understanding the Levels of Digital Inequality within the City: An Analysis of a Survey. Cities 2024, 148, 104844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, Ł.; Kielar, I. Empowering the Elderly in the Information Society: Redefining Digital Education for Polish Seniors in the Age of Rapid Technological Change. Educ. Gerontol. 2024, 51, 2439908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, A.; Ide, K.; Kondo, K. Predictors of Shifts in Internet Use and Frequency among Older Adults in Japan before and in Later Stages of COVID-19: A Longitudinal Panel Study. New Media Soc. 2025, 27, 4975–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.R.O.; Boersma, P.; Ettema, T.P.; Planting, C.H.M.; Clark, S.; Gobbens, R.J.J.; Dröes, R.-M. The Effects of Psychosocial Interventions Using Generic Photos on Social Interaction, Mood and Quality of Life of Persons with Dementia: A Systematic Review. BMC Geriatr 2023, 23, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katey, D.; Chivers, S. Navigating the Digital Divide: Exploring the Drivers, Drawbacks, and Prospects of Social Interaction Technologies′ Adoption and Usage Among Older Adults During COVID-19. J. Aging Res. 2025, 2025, 7625097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). The 47th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. Available online: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2022/0401/c88-1125.html (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Luo, T.; Chen, W.; Liao, Y. Social Media Use in China before and during COVID-19: Preliminary Results from an Online Retrospective Survey. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 140, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana, M.G.; Mascia, M.L.; Tomczyk, Ł.; Penna, M.P. The Digital Divide and the Elderly: How Urban and Rural Realities Shape Well-Being and Social Inclusion in the Sardinian Context. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Gao, S.; Jiang, Y. Digital Divide as a Determinant of Health in the U.S. Older Adults: Prevalence, Trends, and Risk Factors. BMC Geriatr 2024, 24, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzi, S.; Pope, D.; Orton, L.; Bruce, N. Using Photovoice Methods to Explore Older People’s Perceptions of Respect and Social Inclusion in Cities: Opportunities, Challenges and Solutions. SSM-Popul. Health 2016, 2, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, D.; Mahmood, A.; Seetharaman, K.; Miller, W.C.; Mortenson, W.B. Creating Inclusive and Healthy Communities for All: A Photovoice Approach with Adults with Mobility Limitations. SSM-Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.B. Bridging the Family Care Gap: If Not Now, When? Gerontologist 2022, 62, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.S.; Ozolins, L.-L.; Holst, H.; Galvin, K. Digital Engagement of Older Adults: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e40192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, D.B.; Crawford, R.A. Digital Divide: Computers and Our Children’s Future; TV Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Hargittai, E.; Neuman, W.R.; Robinson, J.P. Social Implications of the Internet. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 307–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, J.; Hacker, K. The Digital Divide as a Complex and Dynamic Phenomenon. Inf. Soc. 2003, 19, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia-Keating, M.; Santacrose, D.; Liu, S. Photography and Social Media Use in Community-Based Participatory Research with Youth: Ethical Considerations. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2017, 60, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, E.Y.; Fu, W.Q.; Li, J. On the Fairness of Online Education Development. China Educ. Technol. 2021, 3, 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Jan, A.; van Dijk, G.M. The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 200; 240p, ISBN 141290403X (Paperback). Mass Commun. Soc. 2008, 11, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, R. Addressing the Digital Divide. Online Inf. Rev. 2001, 25, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Liang, S. Digital Inclusion in Public Services for Vulnerable Groups: A Systematic Review for Research Themes and Goal-Action Framework from the Lens of Public Service Ecosystem Theory. Gov. Inf. Q. 2025, 42, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, J.M.; Hernández-Serrano, M.J.; Tabernero, C. Digital Identity Levels in Older Learners: A New Focus for Sustainable Lifelong Education and Inclusion. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Kostka, G. Navigating the Digital Age: The Gray Digital Divide and Digital Inclusion in China. Media Cult. Soc. 2024, 46, 1181–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, B.B.; Waycott, J.; Malta, S. Old and Afraid of New Communication Technologies? Reconceptualising and Contesting the ‘Age-Based Digital Divide’. J. Sociol. 2018, 54, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wu, F.; Tong, H.; Hao, C.; Xie, T. The Digital Divide and Active Aging in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleti, T.; Figueiredo, B.; Martin, D.M.; Reid, M. Digital Inclusion in Later Life: Older Adults’ Socialisation Processes in Learning and Using Technology. Australas. Mark. J. 2024, 32, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, A.; Best, P.; Maddock, A. ‘It’s Just One Big Vicious Circle’: Young People’s Experiences of Highly Visual Social Media and Their Mental Health. Health Educ. Res. 2022, 37, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorea, M. Becoming Your “Authentic” Self: How Social Media Influences Youth’s Visual Transitions. Soc. Media + Soc. 2021, 7, 20563051211047875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Taghizadeh Larsson, A. Communication Officers in Local Authorities Meeting Social Media: On the Production of Social Media Photos of Older Adults. J. Aging Stud. 2021, 58, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.; Chau, A.K.C.; Woo, J.; Lai, E.T. The Age-Based Digital Divide in an Increasingly Digital World: A Focus Group Investigation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 115, 105225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Pan, T.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H. Studies on the Digital Inclusion Among Older Adults and the Quality of Life—A Nanjing Example in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 811959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlatte, O.; Karmann, J.; Gariépy, G.; Frohlich, K.L.; Moullec, G.; Lemieux, V.; Hébert, R. Virtual Photovoice with Older Adults: Methodological Reflections during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221095656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, C.A.; Winters, M.; Sims-Gould, J. “I’m New to This”: Navigating Digitally Mediated Photovoice Methods to Enhance Research with Older Adults. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231199910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, O.E.; Malka, M.; Huss, E.; Hillel Lavian, R. Defying Loneliness: A Phenomenological Study of Older Adults’ Participation in an Online-Based Photovoice Group during COVID-19. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stargatt, J.; Bhar, S.; Bhowmik, J.; Al Mahmud, A. Digital Storytelling for Health-Related Outcomes in Older Adults: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e28113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, D.J.; Smaira, D.; Staeheli, L.A. Intergenerational Place-Based Digital Storytelling: A More-than-Visual Research Method. Child. Geogr. 2022, 20, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M. Cultural Psychology: A Once and Future Discipline; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Novek, S.; Morris-Oswald, T.; Menec, V. Using Photovoice with Older Adults: Some Methodological Strengths and Issues. Ageing Soc. 2012, 32, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Zhu, X.; Wan, K.; Xiang, Z.; Shi, Z.; An, J.; Huang, W. Older Adults’ Self-Perception, Technology Anxiety, and Intention to Use Digital Public Services. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.X.; Ng, J.C.K.; Wu, W.C.H. Social Axiom and Group Identity Explain Participation in a Societal Event in Hong Kong. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.; Gates, J.R.; Vijaykumar, S.; Morgan, D.J. Understanding Older Adults’ Use of Social Technology and the Factors Influencing Use. Ageing Soc. 2023, 43, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforova, A.; Tseng, H.-L.; Azmat Butt, S.; Draheim, D.; Liu, L.-C. Sociotechnical Transformation in the Decade of Healthy Ageing to Empower the Silver Economy: Bridging the Silver Divide through Social and Digital Inclusion. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Taipei, Taiwan, 11 June 2024; pp. 977–980. [Google Scholar]

- Rios Rincon, A.M.; Miguel Cruz, A.; Daum, C.; Neubauer, N.; Comeau, A.; Liu, L. Digital Storytelling in Older Adults with Typical Aging, and with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022, 41, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter-Khan, S.C.; Wongfu, C.; Aein, N.M.P.; Lu, B.; Prina, M.; Suwannaporn, S.; Mayston, R.; Wai, K.M. The Feasibility of Using Photovoice as a Loneliness Intervention with Older Myanmar Migrants. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2025, 1544, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S.K.; Kelly, M.T.; Cooney, E.; Oliffe, J.L. Men’s Accounts of Anxiety: A Photovoice Study. SSM-Qual. Res. Health 2023, 4, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, L.; Sheahan, J.; Figueiredo, B.; Martin, D.; Reid, M.; Aleti, T.; Buschgens, M. Playing with Persona: Highlighting Older Adults’ Lived Experience with the Digital Media. Converg. Int. J. Res. Into New Media Technol. 2025, 31, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; You, J.; Kim, D. Effective but Sustainable? A Case of a Digital Literacy Program for Older Adults. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 13309–13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Alaball, J.; Alarcon Belmonte, I.; Panadés Zafra, R.; Escalé-Besa, A.; Acezat Oliva, J.; Saperas Perez, C. Abordaje de la transformación digital en salud para reducir la brecha digital. Atención Primaria 2023, 55, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Peng, B. Empowering Older Adults: Bridging the Digital Divide in Online Health Information Seeking. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasi-Heikkinen, P.; Doh, M. Older Adults and Digital Inclusion. Educ. Gerontol. 2023, 49, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolazzi, A.; Quaglia, V.; Bongelli, R. Barriers and Facilitators to Health Technology Adoption by Older Adults with Chronic Diseases: An Integrative Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; He, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, L.; Nutakor, J.A.; Zhao, L. Cultural Capital, the Digital Divide, and the Health of Older Adults: A Moderated Mediation Effect Test. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasternak, G. Photographic Digital Heritage in Cultural Conflicts: A Critical Introduction. Photogr. Cult. 2021, 14, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.C.; Swartz, M.C.; Christopherson, U.; Bentley, J.R.; Basen-Engquist, K.M.; Thompson, D.; Volpi, E.; Lyons, E.J. A Photography-Based, Social Media Walking Intervention Targeting Autonomous Motivations for Physical Activity: Semistructured Interviews with Older Women. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e35511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysyuk, Y.; Huisman, M. Photovoice Method with Older Persons: A Review. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 1759–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failli, D.; Arpino, B.; Marino, M.F. A Finite Mixture Approach for the Analysis of Digital Skills in Bulgaria, Finland and Italy: The Role of Socio-Economic Factors. Stat. Methods Appl. 2024, 33, 1483–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishinski, A.; Yadav, A. Self-Evaluation Interventions: Impact on Self-Efficacy and Performance in Introductory Programming. ACM Trans. Comput. Educ. 2021, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, H.L.; Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Akawi, R.L. Rubric-referenced self-assessment and self-efficacy for writing. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 102, 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, S.; Gulliksen, J.; Gustavsson, C. Disability Digital Divide: The Use of the Internet, Smartphones, Computers and Tablets among People with Disabilities in Sweden. Univ. Access. Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, C.; Chattaraman, V. A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words! How Visual Storytelling Transforms the Aesthetic Experience of Novel Designs. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canoro, V.; Picillo, M.; Cuoco, S.; Pellecchia, M.T.; Barone, P.; Erro, R. Development of the Digital Inclusion Questionnaire (DIQUEST) in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). The 55th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. Available online: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2025/0117/c88-11229.html (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Kongsved, S.M.; Basnov, M.; Holm-Christensen, K.; Hjollund, N.H. Response Rate and Completeness of Questionnaires: A Randomized Study of Internet Versus Paper-and-Pencil Versions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2007, 9, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, T.; Dodds, L.; Georgiou, A.; Gewald, H.; Siette, J. Older Adults and New Technology: Mapping Review of the Factors Associated with Older Adults’ Intention to Adopt Digital Technologies. JMIR Aging 2023, 6, e44564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo Müller, A.; Wachtler, B.; Lampert, T. Digital Divide—Soziale Unterschiede in der Nutzung digitaler Gesundheitsangebote. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2020, 63, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, T.; Lin, F. The Digital Divide Is Aging: An Intergenerational Investigation of Social Media Engagement in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; He, R. A Study on Digital Inclusion of Chinese Rural Older Adults from a Life Course Perspective. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 974998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, Y. The Impact of the Digital Divide on Rural Older People’s Mental Quality of Life: A Conditional Process Analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taei, A.; Jönson, H.; Kottorp, A.; Granbom, M. Doing and Belonging: A Photo-Elicitation Study on Place Attachment of Older Adults Living in Depopulated Rural Areas. J. Occup. Sci. 2024, 31, 740–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liang, J.; Xu, Z. Digital Social Media Expression and Social Adaptability of the Older Adult Driven by Artificial Intelligence. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1424898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Maher, M.L. Factors Affecting the Initial Engagement of Older Adults in the Use of Interactive Technology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, S.; Ko, K.-P.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, K.J.; Shin, J.; Kim, C.O.; Ko, M.J.; Kang, S.-J.; et al. Digital Health Technology Use Among Older Adults: Exploring the Impact of Frailty on Utilization, Purpose, and Satisfaction in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuoppamäki, S.; Hänninen, R.; Taipale, S. Enhancing Older Adults’ Digital Inclusion Through Social Support: A Qualitative Interview Study. In Vulnerable People and Digital Inclusion; Tsatsou, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Malka, M.; Edelstein, O.E.; Huss, E.; Hillel Lavian, R. Boosting Resilience: Photovoice as a Tool for Promoting Well-Being, Social Cohesion, and Empowerment Among the Older Adult During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2024, 43, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, R.; Quinton, S.; Baima, G. I Am Who I Am: Sharing Photos on Social Media by Older Consumers and Its Influence on Subjective Well-being. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M.; Benton, N.; Gleissner, L. Older Adults Documenting Purpose and Meaning Through Photovoice and Narratives. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Measurement Items | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital inclusion | DI1 | After taking part in photography activities, are you more willing to use digital devices for other daily activities? | Lishinski et al. (2021) [64] Andrade et al. (2009) [65] |

| DI2 | Do you feel that participating in photography has noticeably increased your involvement in digital society? | ||

| DI3 | Do photography activities make you feel that the gap between your digital skills and those of younger people has decreased? | ||

| DI4 | Has photography helped increase your confidence in using digital technology in daily life? | ||

| DI5 | Is your main reason for participating in photography activities to improve your own digital skills? | ||

| Perceived digital inclusion | PDI1 | Do you feel that photography makes it possible for you to participate equally in the digital society? | Johansson et al. (2021) [66] |

| PDI2 | Has participating in photography increased your sense of connection with digital technology? | ||

| PDI3 | Do you think photography activities have helped eliminate your sense of distance from digital technology? | ||

| PDI4 | Has participating in photography made you more willing to try out new digital technologies? | ||

| Social identity | SI1 | Has photography made it easier for you to keep in touch with family and friends? | Seifert et al. (2020) [67] |

| SI2 | Do you feel that photography has helped you gain more recognition from others? | ||

| SI3 | Has participating in photography enhanced your sense of Social identity? | ||

| Participation in photographic activity | PPP1 | Do you think participating in photography has made your social life richer? | Neves et al. (2018) [31] |

| PPP2 | Do you think digital photography sparks your interest in learning? | ||

| PPP3 | Do you see participating in photography as a way to improve your quality of life? | ||

| PPP4 | Do you feel that photography is an easy way to record and understand your life? | ||

| PPP5 | Do you think photography is an enjoyable way to express your feelings and stories? | ||

| PPP6 | Are you more willing to record and share important moments with others through photography? | ||

| Photographic visual narratives | PVN1 | Do visual stories make you more interested in learning digital technology? | Canorro et al. (2024) [68] |

| PVN2 | Do you find it easy and simple to operate photographic equipment? | ||

| PVN3 | Do digital photography apps give you clear instructions and guidance on how to use them? | ||

| PVN4 | Do you think digital photography tools are designed to be very user-friendly? | ||

| PVN5 | Does using photographic equipment reduce your anxiety about learning new technology? | ||

| PVN6 | Do you feel more connected to society through photography activities? | ||

| Age Range | N | Percentage (%) | Region | N | Percentage (%) |

| 60–65 | 642 | 39.46 | Eastern | 282 | 17.33 |

| 66–70 | 479 | 29.44 | Central | 315 | 19.36 |

| 71–75 | 341 | 20.96 | Western | 427 | 26.24 |

| 76–80 | 165 | 10.14 | Northern | 231 | 14.2 |

| Southern | 372 | 22.86 | |||

| Age range | Eastern (%) | Central (%) | Western (%) | Northern (%) | Southern (%) |

| 60–65 | 116 (18.07%) | 118 (18.38%) | 163 (25.39%) | 92 (14.33%) | 153 (23.83%) |

| 66–70 | 87 (18.16%) | 83 (17.33%) | 132 (27.56%) | 68 (14.20%) | 109 (22.76%) |

| 71–75 | 50 (14.66%) | 74 (21.70%) | 97 (28.45%) | 49 (14.37%) | 71 (20.82%) |

| 76–80 | 29 (17.58%) | 40 (24.24%) | 35 (21.21%) | 22 (13.33%) | 39 (23.64%) |

| Variable | Number of Items | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|

| Digital inclusion | 5 | 0.825 |

| Perceived digital inclusion | 4 | 0.847 |

| Social identity | 3 | 0.779 |

| Participation in photographic activities | 6 | 0.891 |

| Photographic visual narratives | 6 | 0.874 |

| Category | Factor Loadings | Common Factor Variance (Extracted) | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained (%) | CR | AVE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||||

| Digital inclusion | 1 | 0.766 | 0.591 | 3.000 | 12.500 | 0.825 | 0.486 | ||||

| 2 | 0.748 | 0.600 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.747 | 0.587 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.746 | 0.557 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.727 | 0.617 | |||||||||

| Perceived digital inclusion | 1 | 0.727 | 0.688 | 2.686 | 11.191 | 0.847 | 0.581 | ||||

| 2 | 0.770 | 0.694 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.768 | 0.685 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.761 | 0.680 | |||||||||

| Social identity | 1 | 0.780 | 0.678 | 2.031 | 8.461 | 0.779 | 0.541 | ||||

| 2 | 0.780 | 0.704 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.756 | 0.704 | |||||||||

| Participation in photographic activities | 1 | 0.777 | 0.650 | 3.916 | 16.316 | 0.891 | 0.577 | ||||

| 2 | 0.768 | 0.656 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.765 | 0.642 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.758 | 0.666 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.756 | 0.647 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.740 | 0.632 | |||||||||

| Photographic visual narratives | 1 | 0.760 | 0.618 | 3.739 | 15.579 | 0.874 | 0.536 | ||||

| 2 | 0.756 | 0.606 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.756 | 0.634 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.750 | 0.625 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.746 | 0.609 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.735 | 0.602 | |||||||||

| Statistical Testing | Absolute Fitness Indices | Value-Added Adaptation Indices | Parsimonious Fitness Indices | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | RMSEA | GFI | NFI | IFI | CFI | PNFI | PCFI | PGFI | |

| Adaptation standard Parameter | <3 | ≤0.05 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.50 | >0.50 | >0.50 |

| 1.038 | 0.005 | 0.987 | 0.985 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.871 | 0.884 | 0.803 | |

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | AVE > MSV | Digital Inclusion | Perceived Digital Inclusion | Social Identity | Participation in Photographic Activities | Photographic Visual Narratives | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital inclusion | 0.825 | 0.486 | 0.359 | 0.825 | TRUE | 0.697 | ||||

| Perceived digital inclusion | 0.847 | 0.581 | 0.359 | 0.847 | TRUE | 0.599 *** | 0.762 | |||

| Social identity | 0.779 | 0.541 | 0.323 | 0.779 | TRUE | 0.525 *** | 0.568 *** | 0.736 | ||

| Participation in photographic activities | 0.891 | 0.577 | 0.358 | 0.891 | TRUE | 0.539 *** | 0.598 *** | 0.518 *** | 0.760 | |

| Photographic visual narratives | 0.874 | 0.536 | 0.317 | 0.874 | TRUE | 0.488 *** | 0.563 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.427 *** | 0.732 |

| Hypothesis Path | Std Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a. Participation in photographic activities → Perceived digital inclusion | 0.446 | 0.03 | 14.853 | *** | Supported |

| H1b. Participation in photographic activities → Social identity | 0.313 | 0.03 | 8.972 | *** | Supported |

| H2a. Photographic visual narratives → Perceived digital inclusion | 0.294 | 0.032 | 10.251 | *** | Supported |

| H2b. Photographic visual narratives → Social identity | 0.283 | 0.031 | 8.725 | *** | Supported |

| H3a. Perceived digital inclusion → Digital inclusion | 0.225 | 0.027 | 6.604 | *** | Supported |

| H3b. Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.284 | 0.034 | 7.916 | *** | Supported |

| H4. Perceived digital inclusion → Social identity | 0.162 | 0.031 | 4.473 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis Path | Std Estimate | Std. Error | Bias-Corrected Confidence Interval (95%) | p-Value | Effect Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| H5a. Participation in photographic activities → Perceived digital inclusion → Digital inclusion | 0.210 | 0.021 | 0.169 | 0.252 | *** | 38.36% |

| H5b. Participation in photographic activities → Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.046 | 0.014 | 0.020 | 0.072 | ** | 8.41% |

| H5c. Photographic visual narratives → Perceived digital inclusion → Digital inclusion | 0.160 | 0.019 | 0.122 | 0.196 | *** | 29.23% |

| H5d. Photographic visual narratives → Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.048 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.078 | ** | 8.77% |

| H6a. Participation in photographic activities → Perceived digital inclusion → Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.037 | 0.010 | 0.019 | 0.055 | ** | 6.76% |

| H6b. Photographic visual narratives → Perceived digital inclusion → Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.038 | 0.009 | 0.020 | 0.055 | ** | 6.94% |

| Total effect | 0.548 | 0.048 | 0.466 | 0.627 | *** | 100% |

| Hypothesis Path | Path Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | Testing Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (60–65) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.006 | 0.041 | 0.154 | 0.878 | Failed |

| Age (66–70) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | −0.043 | 0.044 | −0.978 | 0.328 | Failed |

| Age (71–75) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.042 | 0.051 | 0.821 | 0.412 | Failed |

| Age (76–80) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.004 | 0.062 | 0.068 | 0.946 | Failed |

| Region (Eastern) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | −0.078 | 0.052 | −1.501 | 0.134 | Failed |

| Region (Central) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.021 | 0.053 | 0.405 | 0.686 | Failed |

| Region (Western) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.074 | 0.046 | 1.607 | 0.108 | Failed |

| Region (Northern) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.048 | 0.056 | 0.850 | 0.396 | Failed |

| Region (Southern) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | −0.062 | 0.047 | −1.331 | 0.183 | Failed |

| Age (60–65) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.013 | 0.039 | 0.333 | 0.739 | Failed |

| Age (66–70) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.019 | 0.041 | 0.448 | 0.654 | Failed |

| Age (71–75) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | −0.039 | 0.045 | −0.853 | 0.394 | Failed |

| Age (76–80) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | −0.010 | 0.063 | −0.153 | 0.879 | Failed |

| Region (Eastern) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.013 | 0.050 | 0.264 | 0.792 | Failed |

| Region (Central) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | −0.005 | 0.047 | −0.112 | 0.911 | Failed |

| Region (Western) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | −0.021 | 0.043 | −0.474 | 0.635 | Failed |

| Region (Northern) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | 0.033 | 0.053 | 0.617 | 0.537 | Failed |

| Region (Southern) × Social identity → Digital inclusion | −0.013 | 0.045 | −0.281 | 0.779 | Failed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Q.; Chen, M. Unraveling the Dynamics of Digital Inclusion: Exploring the Third-Level Digital Divide Among Older Adults in China. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11647. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111647

Cheng Q, Chen M. Unraveling the Dynamics of Digital Inclusion: Exploring the Third-Level Digital Divide Among Older Adults in China. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11647. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111647

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Qian, and Maowei Chen. 2025. "Unraveling the Dynamics of Digital Inclusion: Exploring the Third-Level Digital Divide Among Older Adults in China" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11647. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111647

APA StyleCheng, Q., & Chen, M. (2025). Unraveling the Dynamics of Digital Inclusion: Exploring the Third-Level Digital Divide Among Older Adults in China. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11647. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111647