1. Introduction

The demand for energy-efficient and environmentally sustainable electrical machines has increased rapidly in recent years. In particular, the household appliance industry—including washing machines, refrigerators, and air-conditioning systems—has placed strong emphasis on motor technologies that deliver high efficiency, low noise, and cost-effectiveness [

1,

2]. Electric motors account for a significant share of total energy consumption in modern appliances; therefore, improvements in motor design directly contribute to energy savings, reduced operating costs, and compliance with international energy efficiency regulations such as the International Electrotechnical Commission and ENERGY STAR standards [

3,

4]. These trends underscore the importance of developing new motor topologies that reduce material dependence—particularly on rare-earth magnets—while maintaining or enhancing performance.

Permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs) are widely utilized due to their high efficiency and power density [

5,

6,

7]. Surface-mounted PMSMs are particularly appealing owing to their structural simplicity; however, their torque density is limited because they rely solely on magnet torque. By contrast, interior PMSMs can generate both magnetic and reluctance torques, making them suitable for high-performance applications [

8]. Nevertheless, most high-efficiency PMSMs remain highly dependent on rare-earth permanent magnets such as neodymium–iron–boron (NdFeB), which are associated with high costs, limited availability, and supply risks arising from geopolitical issues [

9,

10]. The volatility of rare-earth material prices continues to pose challenges for motor manufacturers, prompting intensive research into magnet-saving motor designs [

11].

Consequent-pole permanent magnet (CPM) motors have emerged as a promising alternative to address these issues [

12,

13]. In this configuration, permanent magnets of the same polarity are grouped together, while alternating poles are formed using iron cores, thus forming consequent poles. This arrangement effectively reduces magnet usage by up to 50%, thereby lowering material costs and mitigating supply chain risks. Moreover, CPM motors exhibit strong potential for high-speed operation owing to the inherent field-weakening capability of the consequent-pole configuration [

14]. Despite these benefits, CPM motors suffer from inherent drawbacks—asymmetry in the rotor flux distribution leads to distorted back electromotive force (back-EMF) waveforms and increased harmonic components—which result in higher torque ripple, acoustic noise, and reduced efficiency [

15,

16]. These limitations restrict their applicability in household appliances, where smooth and quiet operation is critical.

To overcome these limitations, various rotor modification strategies have been investigated. Previous studies have explored bridge designs to enhance mechanical integrity at high speeds, flux barriers to control magnetic saturation, and optimized magnet arrangements to improve flux utilization [

17,

18]. Although these approaches have yielded partial improvements, the tradeoffs among efficiency, torque ripple, and material reduction remain unresolved. More recently, a flared-type CPM (flared-CPM) topology has been introduced, in which ferrite magnets are arranged in a flared configuration within the rotor [

19,

20]. This design enhances flux concentration within a constrained volume and compensates for the relatively low residual flux density of ferrite magnets compared with rare-earth magnets. The use of ferrite is particularly advantageous for household appliances, as it ensures cost stability and material availability while maintaining compliance with efficiency requirements [

21].

Nevertheless, several challenges remain in the optimization of CPM motors. The inherent asymmetry of flux distribution continues to cause waveform distortion, while structural features such as rotor bridges tend to exacerbate cogging torque and torque ripple [

22,

23]. Furthermore, performance sensitivity to geometric parameters—including the pole-arc ratio, air-gap length, and rotor opening dimensions—necessitates systematic optimization to achieve practical and measurable performance improvements.

As discussed in previous studies, the importance of reducing permanent magnet usage across various permanent magnet machine topologies has been widely recognized. However, several studies have proposed structural modifications without incorporating optimization into the design process. For example, a consequent-pole flux-reversal permanent-magnet (FRPM) machine that reduces permanent magnet material consumption by half compared with a conventional FRPM design was proposed in [

24]. Although optimization was not performed, finite element analysis revealed strong nonlinear interactions among multiple design variables, indicating that advanced multi-objective optimization methods will be essential in future research to further improve performance and magnet utilization efficiency. Similarly, a consequent-pole transverse-flux machine was investigated in [

25], focusing on its structural configuration and electromagnetic characteristics. Further research involving multi-objective optimization and parameter sensitivity analysis was recommended to fully exploit nonlinear interactions among the magnet volume, torque density, and cogging torque. Moreover, an intersect-consequent-pole axial-flux permanent-magnet machine was introduced in [

26], where additional studies incorporating parametric optimization and detailed torque–efficiency evaluations were identified as necessary to quantitatively capture the nonlinear interactions among design parameters and to balance magnet reduction with performance stability. Therefore, these non-optimized design approaches remain inadequate for capturing the complex nonlinear interactions among key variables, highlighting the growing need to employ advanced optimization methodologies to achieve effective performance enhancement in electric machines.

In this study, we address these challenges by integrating structural modifications and numerical optimization to improve the performance of a flared-CPM motor. First, structural modifications—including bridge removal and an asymmetric air-gap design—were introduced to improve flux symmetry and reduce cogging torque. Next, three critical design parameters—polar angle, asymmetric air-gap length, and rotor opening length—were systematically optimized using Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) [

27,

28] combined with an evolutionary algorithm (EA) [

29,

30]. Finite element method (FEM) analyses were performed under both no-load and rated-load conditions to evaluate motor characteristics. The proposed approach achieved substantial improvements—torque ripple was reduced by up to 77.8%, cogging torque was reduced by 43.4%, and efficiency increased by approximately 0.5%—compared with the basic model. These results confirm that combining structural modifications with numerical optimization provides an effective pathway for designing cost-efficient, high-performance flared-CPM motors. Additionally, stress analysis according to high-speed rotation was added, and it was confirmed that there was a 5.5× safety margin at four times the rated speed. a safety margin.

2. Basic Model of Flared-CPM Motors

2.1. Basic Model of the Flared-CPM Motor

The basic model employed in this study features a flared-type rotor configuration. In this design, multiple ferrite magnets are arranged in a flared pattern within the rotor, with each pole composed of four or more magnets. This flared arrangement helps concentrate magnetic flux toward the central axis, thereby enhancing flux utilization within the limited rotor volume. An additional advantage of this configuration is the ease of adjusting the polar angle, which enables flexible control of the air-gap flux distribution.

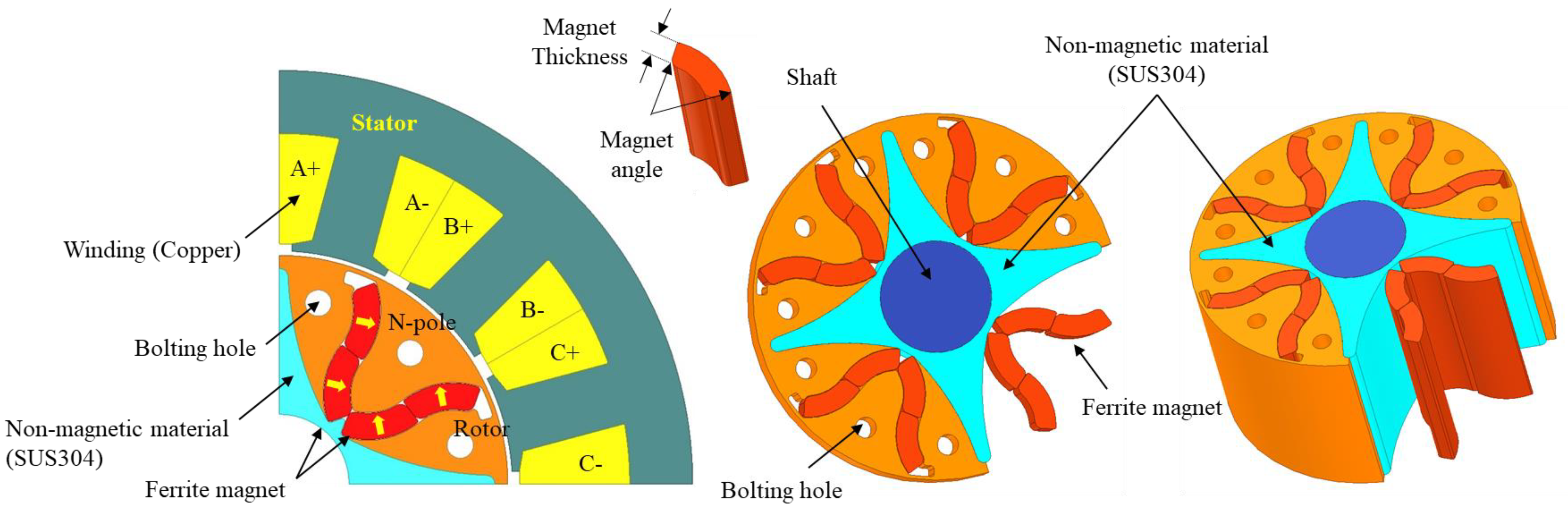

The proposed model employs a consequent-pole rotor structure combined with a flared-magnet arrangement as the basic model. As shown in

Figure 1, four ferrite magnets are used to form a single north pole. Compared with a conventional flared-type permanent magnet rotor, one south pole is replaced with a consequent pole composed of magnetic material. To reduce the computational preprocessing time, a periodic model representing one-quarter of the entire structure is utilized. The materials and primary specifications of the basic flared-CPM motor are listed in

Table 1.

Flared-CPM motors are widely applied in household appliances and automotive air-conditioning drive systems. Current design trends in this domain emphasize high efficiency, superior performance, miniaturization, environmental sustainability, and cost-effectiveness. By reducing the use of permanent magnets by nearly half, flared-CPM motors provide a significant cost advantage over conventional designs, particularly those using NdFeB magnets.

However, motors used in household and automotive air-conditioning systems are often susceptible to noise and vibration issues, depending on their mounting location. To address these challenges, this study investigated an asymmetric air-gap structure aimed at reducing noise and vibration while maintaining cost benefits. The primary objective was to validate the effectiveness of the proposed model through systematic optimization.

2.2. Proposed Model Without the Bridge Structure

In conventional interior permanent magnet motors, a bridge structure is incorporated into the rotor to secure the embedded magnets. The thickness of this bridge is typically determined by the rotational speed, as excessive stress at high speeds may cause mechanical failure if the yield strength of the steel is exceeded. In addition to providing mechanical integrity, the bridge establishes an internal flux path within the rotor. Although this flux path ensures magnet retention, it can reduce the effective flux linkage with stator windings, thereby limiting torque generation.

This study investigated whether eliminating the bridge structure can improve electromagnetic performance. FEM analysis was conducted to compare motor characteristics before and after bridge removal to quantify the resulting performance changes.

In the basic model, a bridge is necessary to prevent rotor scattering and maintain rigidity. However, this structural element introduces a leakage path for magnetic flux within the rotor, which distorts the flux distribution at the north and south poles. Therefore, in a consequent-pole rotor configuration, the effects of the bridge must be carefully analyzed.

Figure 2 illustrates the rotor geometry before and after bridge removal.

With the bridge structure removed, the rotor can be divided into three separate pieces, as shown in

Figure 2. The overall structural integrity is maintained using a bolted assembly. To prevent detachment of the joints and permanent magnets, mechanical rigidity can be reinforced by injecting plastic resin, applying bonding agents, or inserting additional nonmagnetic materials. In this study, rigidity was enhanced using a combination of nonmagnetic materials and bonding, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

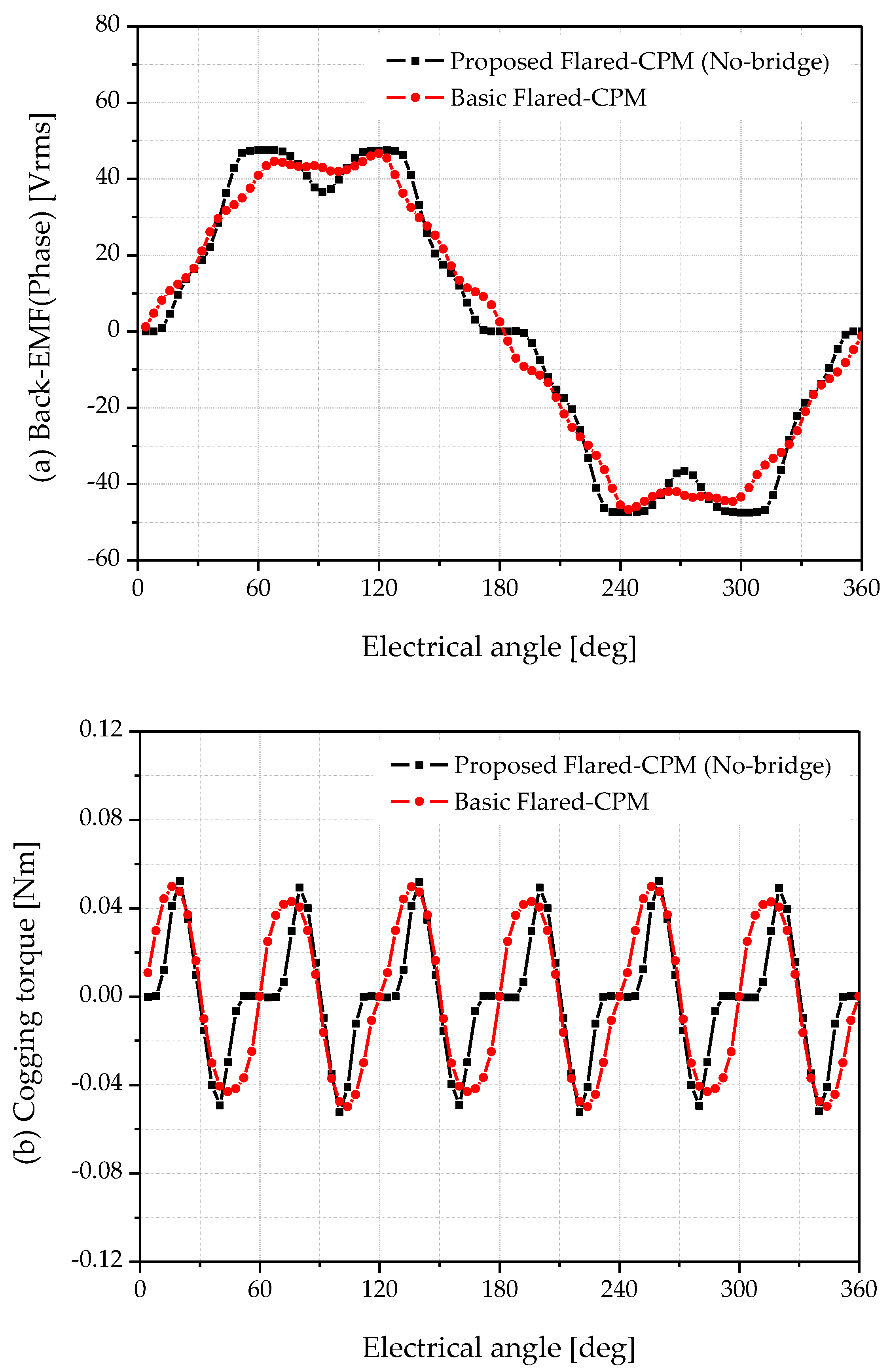

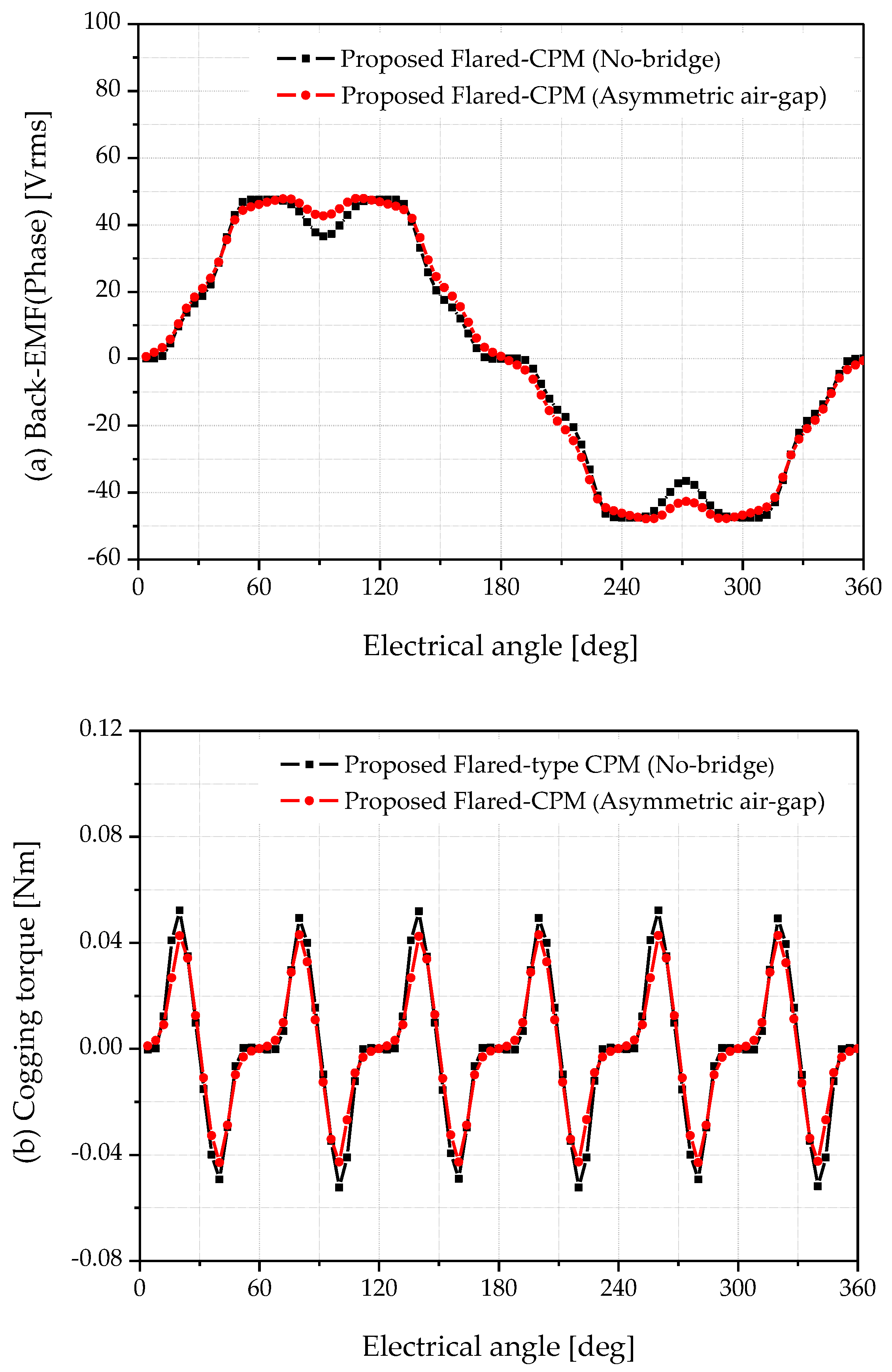

Figure 3 shows a comparison of back-EMF and cogging torque waveforms between the basic model with bridges and the proposed model without bridges. The results indicate that bridge removal clarifies the north- and south-pole flux distribution on the rotor surface, resulting in a more symmetrical back-EMF waveform with increased magnitude.

Table 2 summarizes the no-load analysis results: back-EMF and cogging torque are increased by 4.6% and 4.9%, respectively. The rise in cogging torque is attributed to the higher magnetic flux density in the air gap caused by bridge removal.

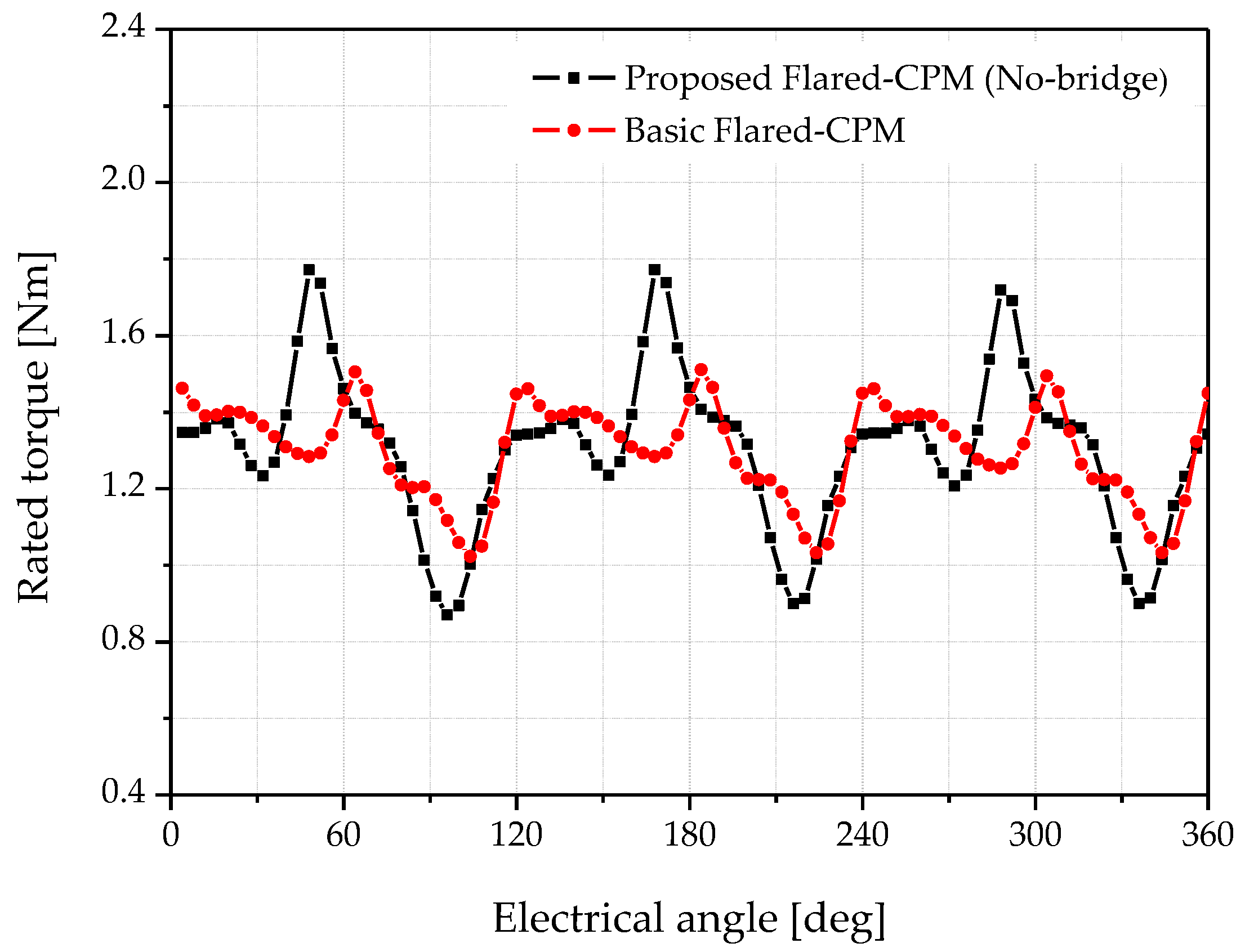

Figure 4 shows the torque waveforms under the rated-load condition, and

Table 3 summarizes the corresponding analysis results. Following bridge removal, the back-EMF increased by 4.6% and exhibited a more symmetrical. However, this structural modification also resulted in a higher cogging torque and a significant increase in torque ripple.

As shown in

Table 3, efficiency improved slightly by 0.3%, whereas torque ripple nearly doubled. This effect can be attributed to the absence of the bridge, which causes the magnetic flux to pass through a narrower rotor surface. The resulting variation in the air-gap flux density was amplified, leading to an increase in torque ripple.

2.3. Reduction in Torque Ripple via the Application of an Asymmetric Air-Gap Structure

As discussed in

Section 2.2, the presence or absence of a bridge structure in a consequent-pole rotor has a significant impact on motor performance. Removing the bridge increases the magnitude of the back-EMF and improves waveform symmetry; however, it also introduces notable distortion.

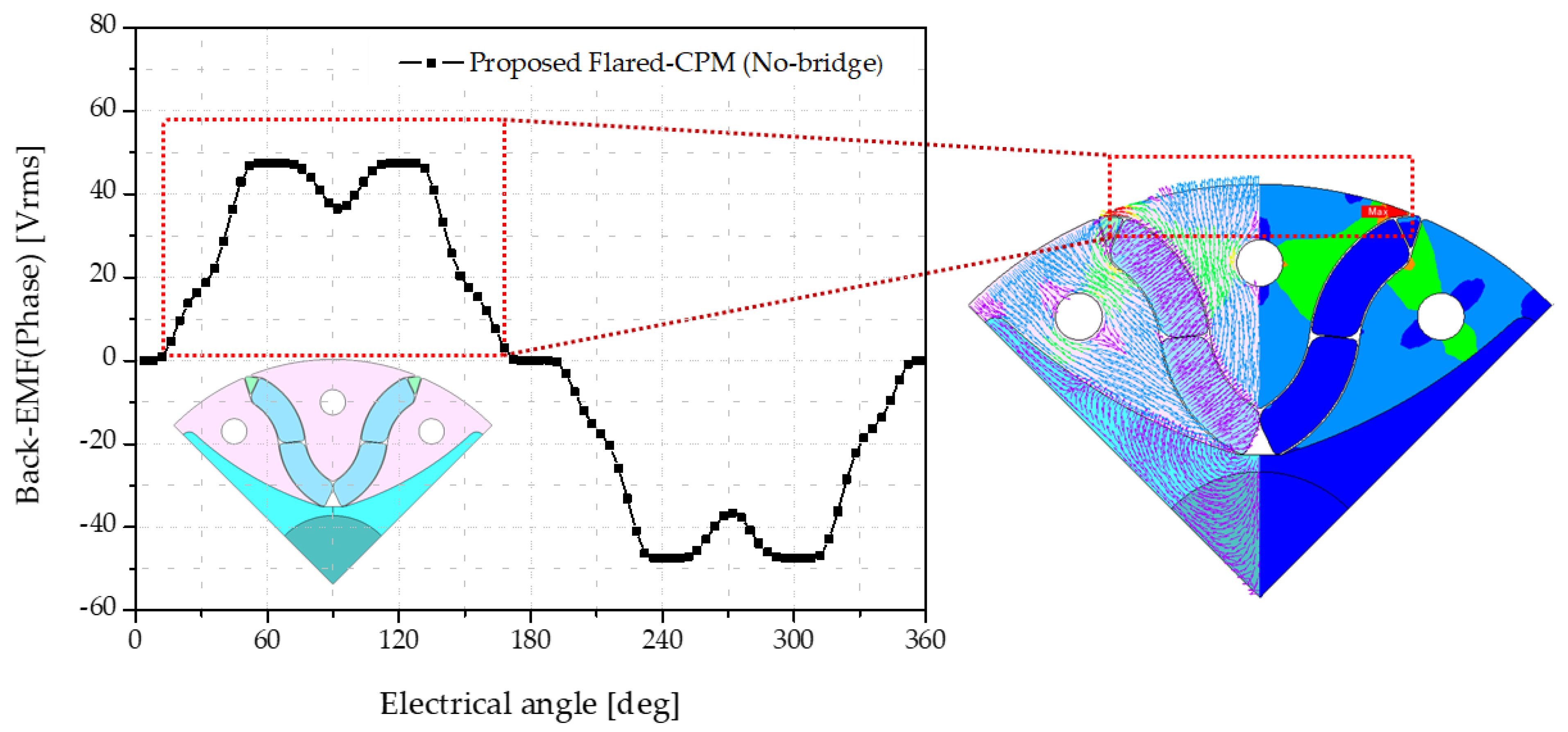

Figure 5 illustrates the back-EMF waveform and the corresponding magnetic flux distribution in the rotor. This pronounced distortion arises from the high rate of flux variation at the center of the rotor, which amplifies torque ripple. This observation highlights the need for an additional design measure to mitigate waveform distortion, specifically through the implementation of an asymmetric air-gap structure.

An increase in back-EMF distortion directly leads to a higher torque ripple. To address this issue, this study investigated the effect of applying an asymmetric airgap structure in

Section 2.3.

Figure 6 shows a comparison of two rotor configurations: the proposed model without a bridge (left) and the bridge-removed model incorporating an asymmetric air gap (right).

The application of an asymmetric air-gap structure reduced the rate of magnetic flux variation near the pole center on both sides of the air gap. Consequently, the Back-EMF waveform became smooth, as indicated by the red dotted line in

Figure 6. In this study, two air-gap radii (26.25 and 26.0 mm) were evaluated based on the position of the inserted nonmagnetic material.

Figure 7 shows a comparison of the back-EMF and cogging-torque waveforms of the bridge-removed rotor with and without the asymmetric air gap.

Figure 7a shows that the back-EMF waveform near the pole center is noticeably improved, whereas

Figure 7b demonstrates a reduction in cogging torque. Quantitative results summarized in

Table 4 indicate that implementing an asymmetric gap decreases cogging torque by 17.8% while simultaneously increasing the back-EMF magnitude by 3.2%.

The performance improvements observed under no-load conditions were further validated through load analysis.

Figure 8 shows a comparison of torque waveforms for the bridge-removed rotor with and without an asymmetric air gap. The results demonstrated that implementing an asymmetric air gap reduced torque ripple and yielded a smoother torque waveform under a rated-load operation.

2.4. Performance Comparison Based on Bridge Removal and Asymmetric Air-Gap Application

As discussed in

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3, both bridge removal and implementation of an asymmetric air gap significantly influence the performance of flared-CPM motors.

Table 5 provides a comprehensive comparison of load analysis results across four configurations: with or without the bridge structure and with either a symmetric or an asymmetric air gap. All results were normalized to the same output power to ensure consistency.

As indicated in

Table 5, bridge removal increased the magnetic flux linkage with the stator windings, thereby enhancing the back-EMF; however, it also resulted in a higher torque ripple. By contrast, applying an asymmetric air gap further increased the back-EMF while simultaneously reducing torque ripple by improving the effective flux distribution across the air gap.

3. Optimal Design of the Flared-CPM Model

Building on the findings reported in

Section 2, this section focuses on optimizing the rotor structure incorporating an asymmetric air gap. The design variables considered were the magnetic polar angle, asymmetric air-gap length, and rotor opening length, which together define a single pole.

Electromagnetic analyses were performed to evaluate the effects of these variables on back-EMF, efficiency, and torque ripple. The performance of the optimized rotor was subsequently compared with that of the basic model using the FEM to validate the effectiveness of the proposed design. JMAG Designer v21.1 was employed for electromagnetic simulations, while PIAnO v2025 was used for the optimization process.

3.1. Setting Design Variables and Objective Functions for Optimization (Step I)

Three design variables were selected for the optimization process: the magnetic pole angle, asymmetric air-gap length, and rotor opening length. Sampling points for these variables were generated using LHS, and electromagnetic field analyses were performed for each case under both no-load and loaded conditions. A total of 18 sampling points were evaluated.

The resulting performance data were then optimized using an EA. The EA is a global optimization technique inspired by natural selection, employing operations such as selection, recombination, and mutation. Unlike conventional methods, it directly handles real-valued design variables without encoding, simplifying calculations and enabling the simultaneous consideration of both continuous and discrete parameters. The optimization process begins with initial individual parameters generated by the optimal LHS, after which new individual parameters are iteratively created and evaluated until convergence is achieved.

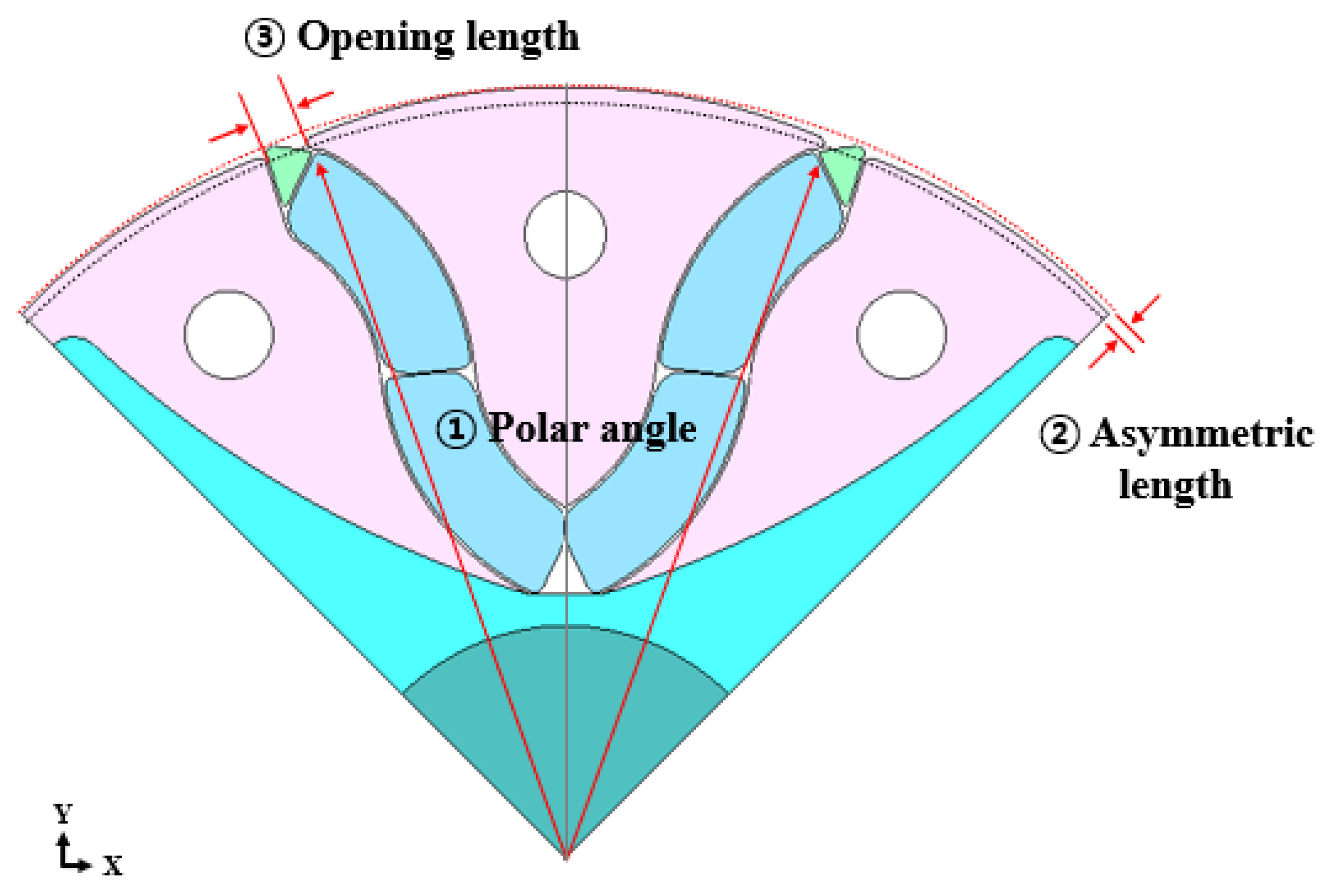

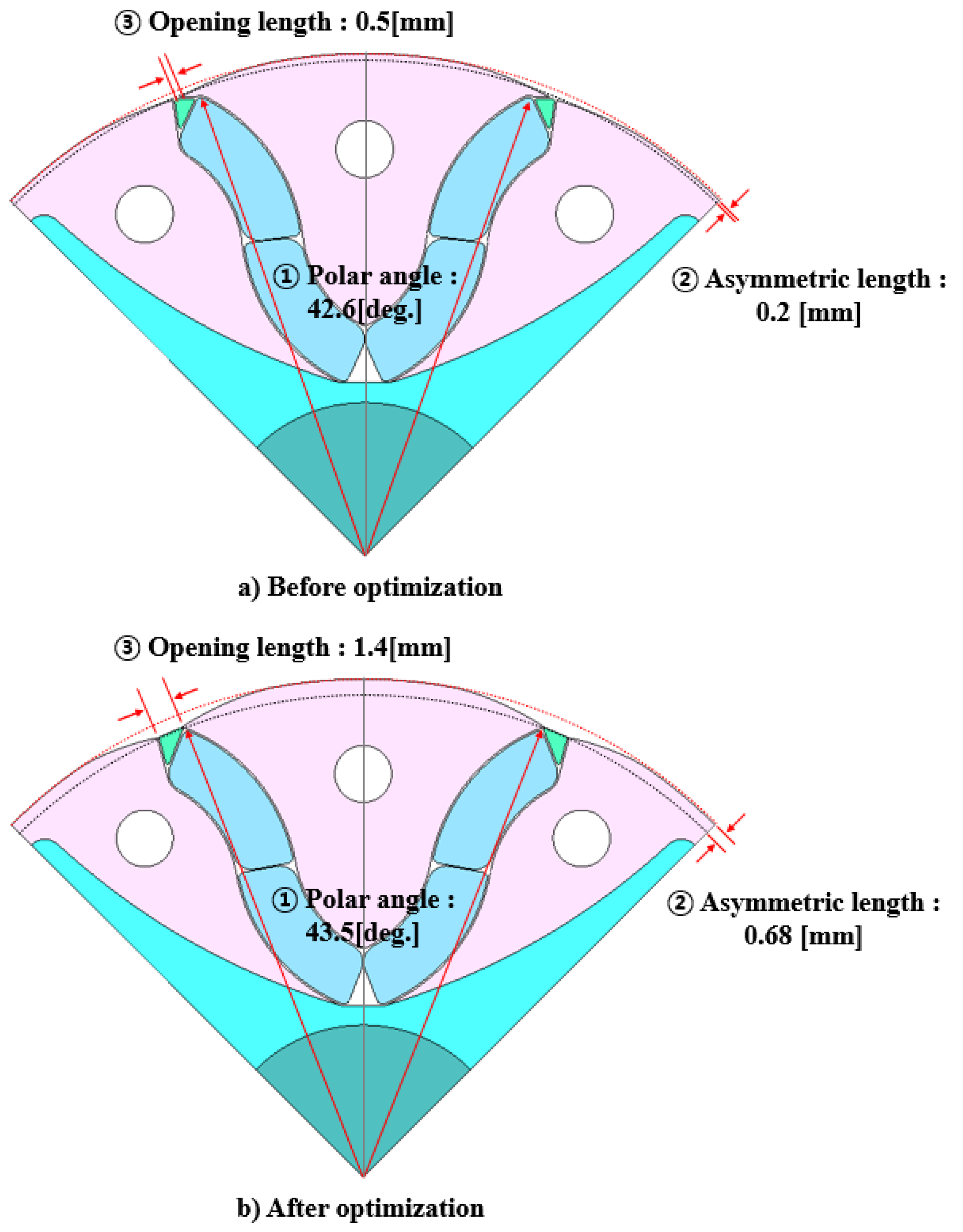

Figure 9 illustrates the three design variables considered in this study, and

Table 6 summarizes their ranges along with the corresponding objective functions. The optimization objectives were defined as maximizing efficiency and minimizing torque ripple under rated-load conditions.

Table 6 lists the design variables and their respective ranges. Two objective functions were defined for the optimization process: maximizing efficiency at the rated load and minimizing torque ripple. As cogging torque under no load ultimately contributes to torque ripple under load, the objective was simplified to minimizing torque ripple. Additionally, improvements in the magnitude and waveform of back-EMF indirectly reduce torque ripple, further justifying this choice.

By contrast, an increase in the back-EMF magnitude under no-load reduces the current required during load operation, thereby lowering copper losses and enhancing efficiency. Consequently, efficiency was selected as the primary objective function.

3.2. Design of the Experiment (DOE) Using LHS (Step II)

To optimize the rotor structure, experimental points were generated using LHS. LHS is a stratified Monte Carlo method that approximates the probability distribution of sampling points by dividing each design variable range into equal-probability intervals. This approach ensures broad and uniform coverage of the design space and is particularly effective for computationally intensive models.

In this study, the two-dimensional (2D) FEM was employed to evaluate the electromagnetic performance of each design point generated by LHS.

Table 7 summarizes the analysis results of all DOE cases.

3.3. Optimal Design of the Proposed Flared-CPM Model Using the EA (Step III)

Th EA was applied to determine the optimal design point that satisfies the defined objective functions and constraints.

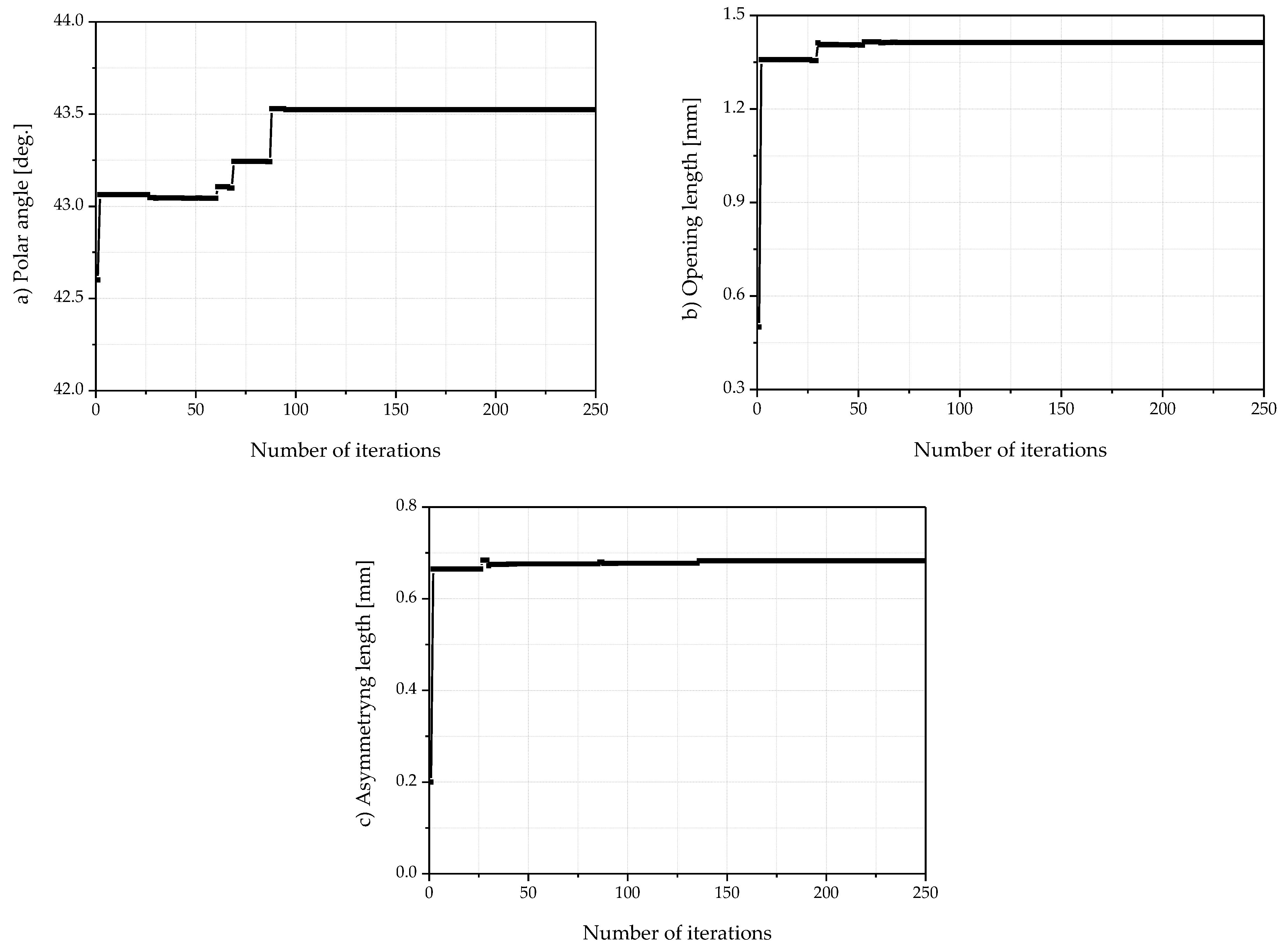

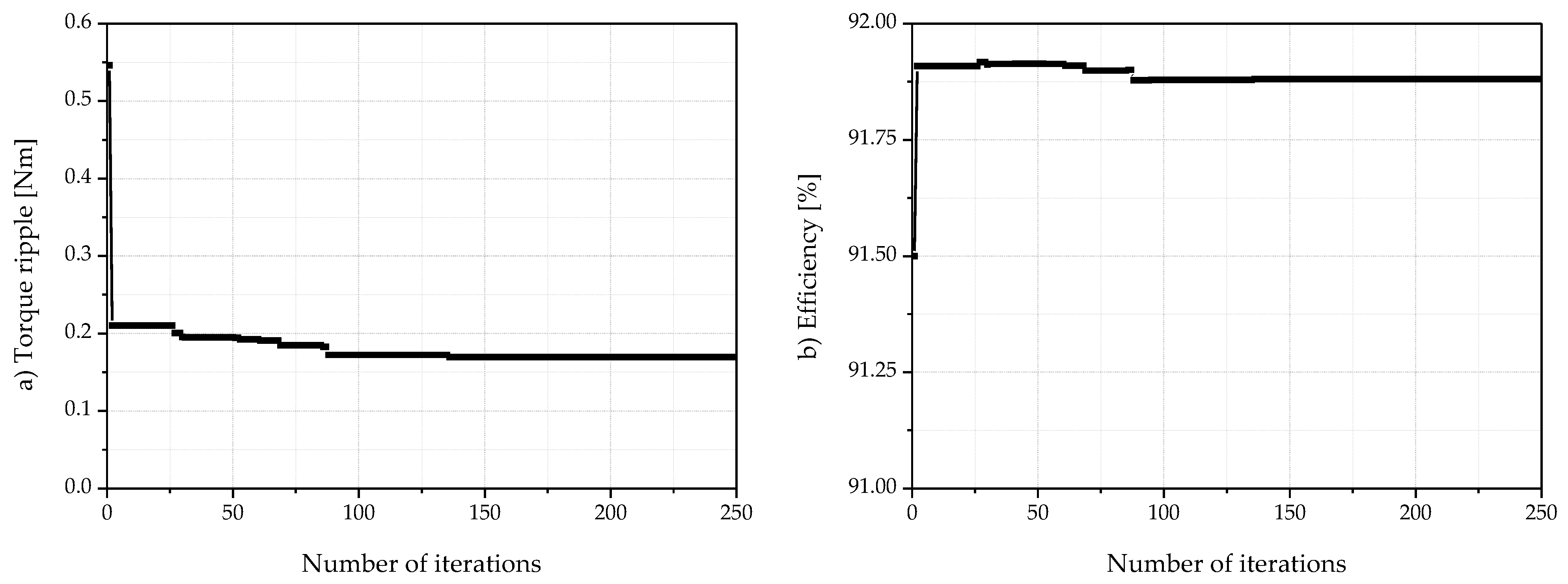

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrate the convergence of design variables and objective functions toward the optimal solution. The maximum number of iterations was set to 250, considering the trade-off between computational cost and design accuracy.

Figure 12 illustrates the rotor geometry after optimization, and

Table 8 lists the optimal values of the design variables obtained. The results showed that all design variables increased relative to their initial values. As shown in

Figure 10a,b, each variable exhibited a noticeable shift from its pre-optimization setting toward the optimized configuration.

3.4. Analysis Results of the Optimal Design (Step IV)

The model converged to an optimal solution using the EA and was subsequently evaluated through FEM analysis to verify its electromagnetic characteristics. Specifically, torque ripple and efficiency under loading conditions were compared with those of the basic model to assess the effectiveness of the optimization method.

Figure 13 illustrates a comparison between the basic and optimized flared-CPM models under no-load conditions. The optimized design, achieved by simultaneously adjusting the three design variables, produced a more sinusoidal flux density distribution in the air gap, which in turn generated an almost sinusoidal back-EMF waveform. This improvement in back-EMF symmetry directly contributed to reduced torque ripple and enhanced efficiency.

Table 9 summarizes the results of the no-load analysis. Compared with the basic model, the optimized model increased back-EMF by 6.9% and reduced cogging torque by 43.4%, clearly demonstrating the advantages of the proposed optimization approach.

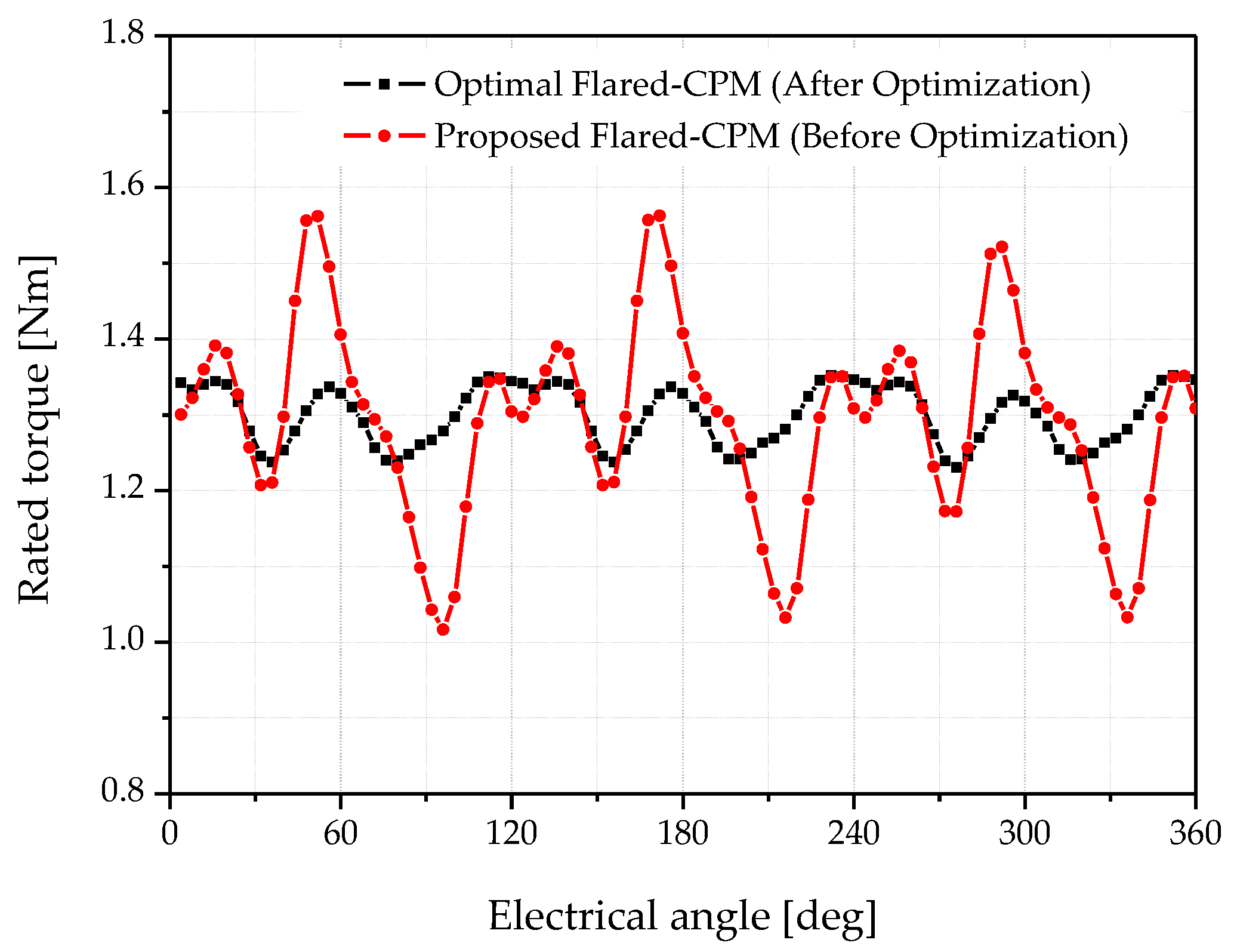

Figure 14 illustrates the torque waveform under rated load, and

Table 10 summarizes the 2D-FEM analysis results for the optimized and basic flared-CPM models. The optimization significantly reduced torque ripple by 77.8% and improved efficiency by 0.5%. These results confirm that the combined application of bridge removal, asymmetric air-gap design, and parameter optimization provides a highly effective approach for enhancing both the performance stability and energy efficiency of Flared CPM motors.

Figure 15 illustrates the comparison of flux density distributions under rated-load conditions. After optimization, the rotor flux density reached approximately 1.2 T, indicating that magnetic saturation was not a concern. The most notable benefit of optimization is the substantial reduction in torque ripple. Compared with the initial design, torque ripple decreased by 77.8%, leading to a substantial improvement in vibration performance. Additionally, efficiency increased by 0.5% due to reduced iron losses. As illustrated in

Figure 13a, the formation of a more sinusoidal back-EMF waveform reflects a reduction in harmonic components, which further mitigates iron loss in the rotor structure.

4. Structural Analysis of the Optimal Flared-CPM Motor

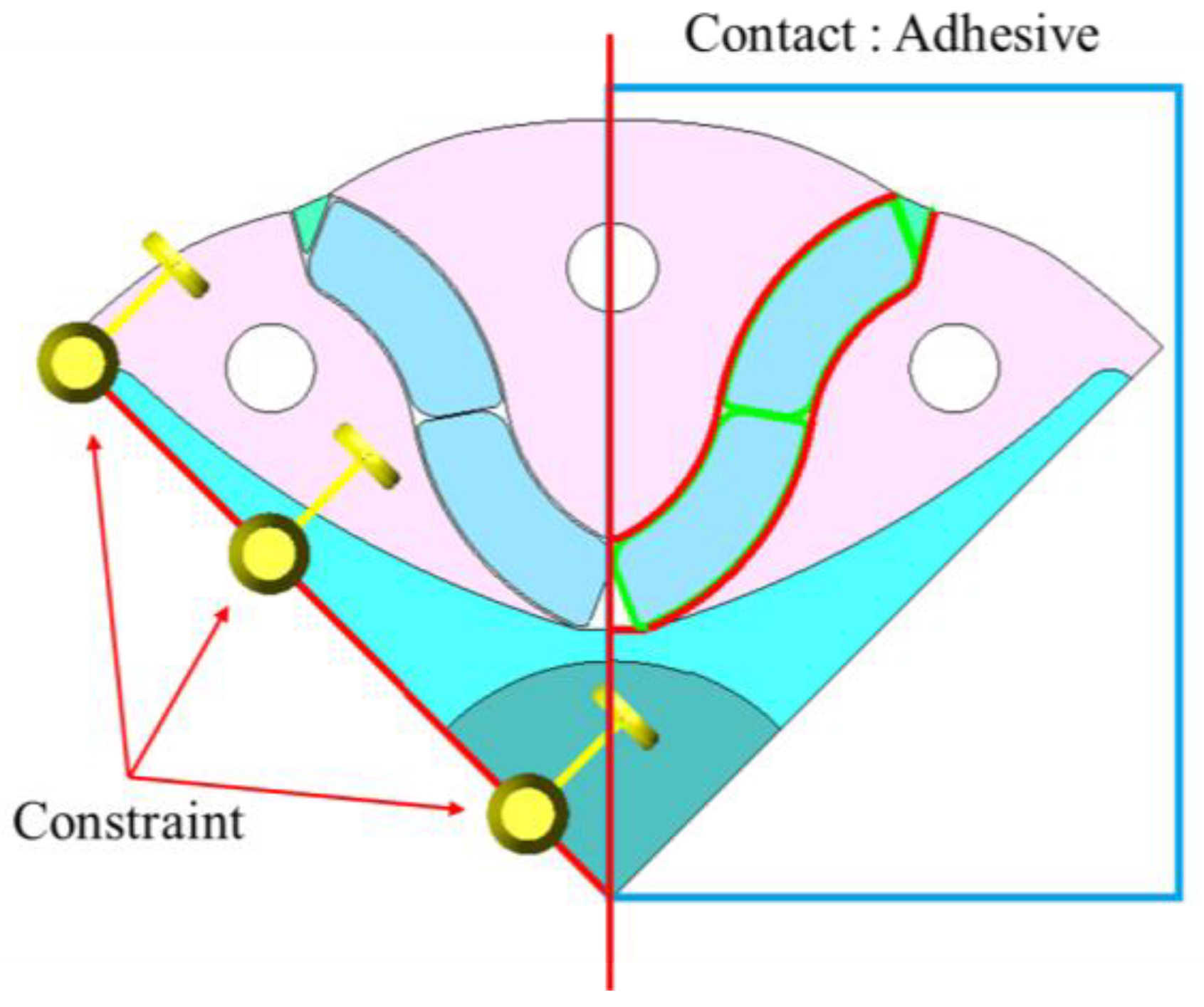

The optimized flared-CPM motor comprises a rotor core, permanent magnets, nonmagnetic materials, and a shaft, as shown in

Figure 12. Accordingly, the rotor was assembled using various fastening forces.

Figure 16 illustrates the three-step process for assembling the rotor.

As shown in

Figure 16, the rotor was constructed by combining various components and applying three types of structural fastening forces. First, chemical bonding occurs between the rotor and permanent magnets via an adhesive. Second, a physical bonding force is created by the bolting force. Third, injection forming is performed using a plastic resin. Subsequently, the fastening strength of the rotor structure must be verified through structural analysis. Furthermore, the structural deformation that occurs during high-speed rotation must be analyzed to ensure an adequate safety margin compared with the rated speed.

Von Mises stress analysis, a standard method for structural assessment, was employed in this study to predict material yield under complex external stresses. This method also estimates deformation and shear potential under external stresses, making it essential for assessing material safety. Structural analysis was performed on the basic adhesive structure, in which the bonding and resin structures secured only the cores. Permanent magnets were held in place by the adhesive applied between them and the rotor cores. If the adhesive is weak, permanent magnets may be susceptible to damage at high speeds.

Figure 17 illustrates the structural analysis setup. The left side of

Figure 17 shows the applied constraint conditions, while the right side depicts the adhesive layer between the rotor core and the permanent magnets.

The rated speed of the optimized flared-CPM motor was 7500 rpm. To perform stress analysis under high-speed conditions, the rotational speed was increased by two to four times the rated speed. The safety margin was assessed by comparing von Mises stresses and displacements across these speed ranges. In particular, potential rotor dispersal was evaluated by examining the displacement of the adhesive layer between the rotor core and the permanent magnets. The yield strength of the rotor core was assessed by analyzing von Mises stresses within the core.

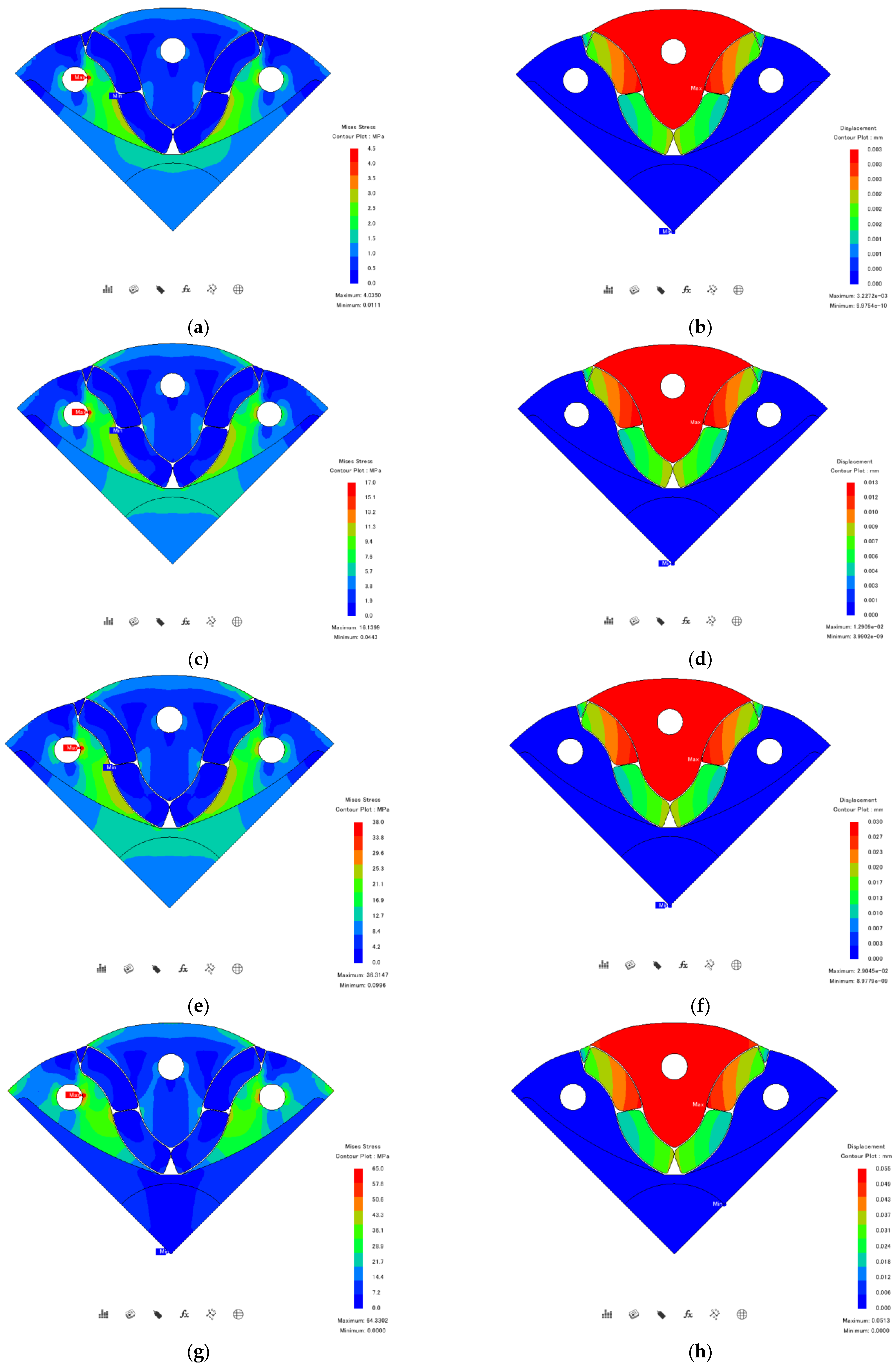

Figure 18 shows the results of stress analysis at various speeds.

As shown in

Figure 18, the point at which the maximum stress occurred was identified as the maximum point. As the speed increased, the centrifugal force increased; therefore, the displacement of the rotor core further increased.

Table 11 summarizes the stress analysis results based on speed. When rotating at a speed of 30 krpm, the maximum stress applied to the rotor core was 64.33 MPa, and the safety margin was 5.5 times. The displacement of the rotor core due to centrifugal forces was calculated to be 0.051 mm. This confirms that the proposed assembly method provides a safety margin for high-speed rotation of the rotor structure.

The analysis results for high-speed stress are based on 2D FEM results. After further review through FEM analysis, prototype fabrication and evaluation will be conducted. In particular, experimental verification will include no-load performance (back EMF, cogging torque, etc.) and load performance (torque pulsation, efficiency, etc.).

Figure 16 shows how the prototype was built and assembled.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated a flared-CPM motor employing ferrite magnets arranged in a flared configuration to enhance flux concentration within a compact rotor. Although CPM structures reduce the use of permanent magnets by nearly 50% compared with conventional PMSMs, they are susceptible to flux asymmetry, leading to distorted back-EMF waveforms and increased torque ripple. To address these issues, a bridge-removal structure and an asymmetric air-gap design were introduced and further optimized.

Optimization was performed using LHS and the EA using three design variables: polar angle, asymmetric air-gap length, and rotor opening length. The FEM analyses under both no-load and rated-load conditions verified the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Compared with the basic model, the optimized design reduced the rated-load torque ripple by 77.8%, decreased cogging torque by 43.4%, and increased efficiency by 0.5%. These findings demonstrate that combining structural modifications with advanced optimization provides a cost-effective and energy-efficient design approach for ferrite-based CPM motors. Beyond household appliances, the proposed methodology shows strong potential for compact drive systems, such as automotive air-conditioner compressors and small e-mobility platforms, where vibration suppression and rare-earth savings are critical.

A structural analysis of the optimized flared-CPM motor was performed to evaluate the effects of centrifugal forces during high-speed rotation. The results indicated a safety margin of 5.5 times, even at four times the rated speed.

However, this study was limited to simulation-based analysis. Future research will focus on prototype fabrication, experimental validation, and mechanical reliability testing of bridge-free rotors under high-speed operating conditions. These efforts will further confirm the practical feasibility of the proposed design and expand its potential for industrial applications.