Abstract

The composition elements of the earthwork allocation system (excavation project, filling project, transfer yard, waste disposal yard, and material yard) and the relationship between material flow were analyzed. Based on the construction of calculation models for soil and water conservation fees, landscape restoration fees, and road transportation intensity, a joint optimization model was constructed with the objectives of minimizing the total allocation cost and minimizing the peak transportation intensity of the road. By dynamically adjusting the volatility, setting penalty factors, and vectorizing NumPy arrays, the ant colony algorithm is improved and the optimization model is solved. Case analysis shows that considering the intensity of road transportation, the peak transportation intensity significantly decreases, and the proportion of directly filled earthwork increases to over 88% without exceeding the capacity of the intermediate transfer site. The total cost only increases by 0.91%, and the allocation plan is more in line with actual construction needs.

1. Introduction

The optimization research of the earthwork allocation system has undergone decades of development, gradually shifting from a single objective to multi-factor collaborative analysis. Early research focused on balancing cost and efficiency, such as Mayer’s [1] linear programming model, which optimized allocation schemes by minimizing transportation distance; Moreb [2] further introduces road slope variables to refine cost accounting; Zheng et al. [3] used the simplex method to construct a dynamic allocation model, achieving real-time adjustment during the construction process; Hu et al. [4] introduced GIS visualization technology to statically process dynamic problems, combined with a simple method for solving, and successfully applied it to earthwork engineering. Henderson et al. [5] used a simulated annealing algorithm to optimize transportation routes and reduce congestion risks during peak hours; Lim et al. [6] combined taboo search with simulated annealing to solve the local optimal problem; Wang et al. [7] introduced the Monte Carlo tree search algorithm to improve the reliability of dynamic allocation. With the increasing awareness of environmental protection, scholars have begun to pay attention to ecological impacts: Jiao et al. [8] mainly quantified the soil erosion cost of waste disposal sites but did not link it with road transportation intensity for optimization; Carmichael et al. [9] and Burdett et al. [10] focused on carbon emissions and fuel consumption but did not systematically incorporate soil and water conservation and landscape restoration costs into the objective function; and Shen et al. [11] considered transportation intensity, but their environmental cost model was relatively simplified. Existing research often analyzes soil and water conservation fees, landscape restoration fees, or road transportation intensity in isolation, and has not yet established a complete framework for the collaborative optimization of the three. Therefore, this article constructs a comprehensive cost optimization model that includes soil and water conservation fees, landscape restoration fees, and road transportation intensity.

This study selects the ant colony algorithm as the solution method, primarily for the following reasons: Firstly, the earthwork allocation problem is essentially a problem of finding the optimal combination of paths for materials from ‘sources’ (excavation projects) to ‘sinks’ (filling projects, transfer yards, etc.), which highly aligns with the path optimization problems that the ant colony algorithm excels at solving. Secondly, compared to linear programming or the simplex method, heuristic algorithms like the ant colony algorithm can more flexibly handle the nonlinear constraints and discrete decision variables present in our model, such as the dynamic balance of transfer yard capacity and path selection. Furthermore, compared to simulated annealing or genetic algorithms, the ant colony algorithm, through the positive feedback mechanism of pheromones, often demonstrates better convergence and stability when solving complex, dynamic earthwork allocation schemes, and has been widely applied in the field of earthwork allocation in recent years. Marzouk and Moselhi [12] were the first to combine genetic algorithms with ant colony thinking to solve multi-objective optimization problems; Huang et al. [13] used an improved ant colony algorithm to generate economically feasible allocation plans, and combined GIS technology to achieve visualization; Zhao [14] used a three-dimensional ant colony model to reduce deployment errors and improve operational efficiency; Miao [15] solved the discrete domain optimization problem of large space in earthwork allocation through longitudinal section optimization research based on ant colony algorithm; Sun [16] combined GIS with ant colony algorithm to dynamically display the adjustment results in real-time; Li et al. [17] introduced a penalty factor to handle capacity overruns and enhance the robustness of the algorithm. However, traditional ant colony algorithms have significant limitations. Firstly, the pheromone update mechanism is rigid and prone to becoming stuck in local optima. The second is to ignore dynamic constraints, such as fluctuations in transition capacity, which makes it difficult to adapt to multi-stage construction needs. Therefore, this article improves the ant colony algorithm by dynamically adjusting the volatility, setting penalty factors, and vectorizing NumPy arrays.

In summary, the main contributions and innovations of this research are as follows:

- Constructed a joint optimization model for earthwork allocation that simultaneously integrates soil and water conservation fees, landscape restoration fees, and road transportation intensity, filling the gap in existing research for a multi-factor collaborative optimization framework.

- Proposed an improved ant colony algorithm that effectively enhances solution efficiency and robustness by dynamically adjusting volatility, introducing penalty factors, and incorporating NumPy vectorized computation.

- Verified the effectiveness of the model and algorithm through a case study, showing that considering transportation intensity can significantly reduce the peak road load and increase the proportion of direct filling with only a small increase in total cost, making the allocation plan more aligned with actual construction needs.

2. Composition of Earthwork Allocation System

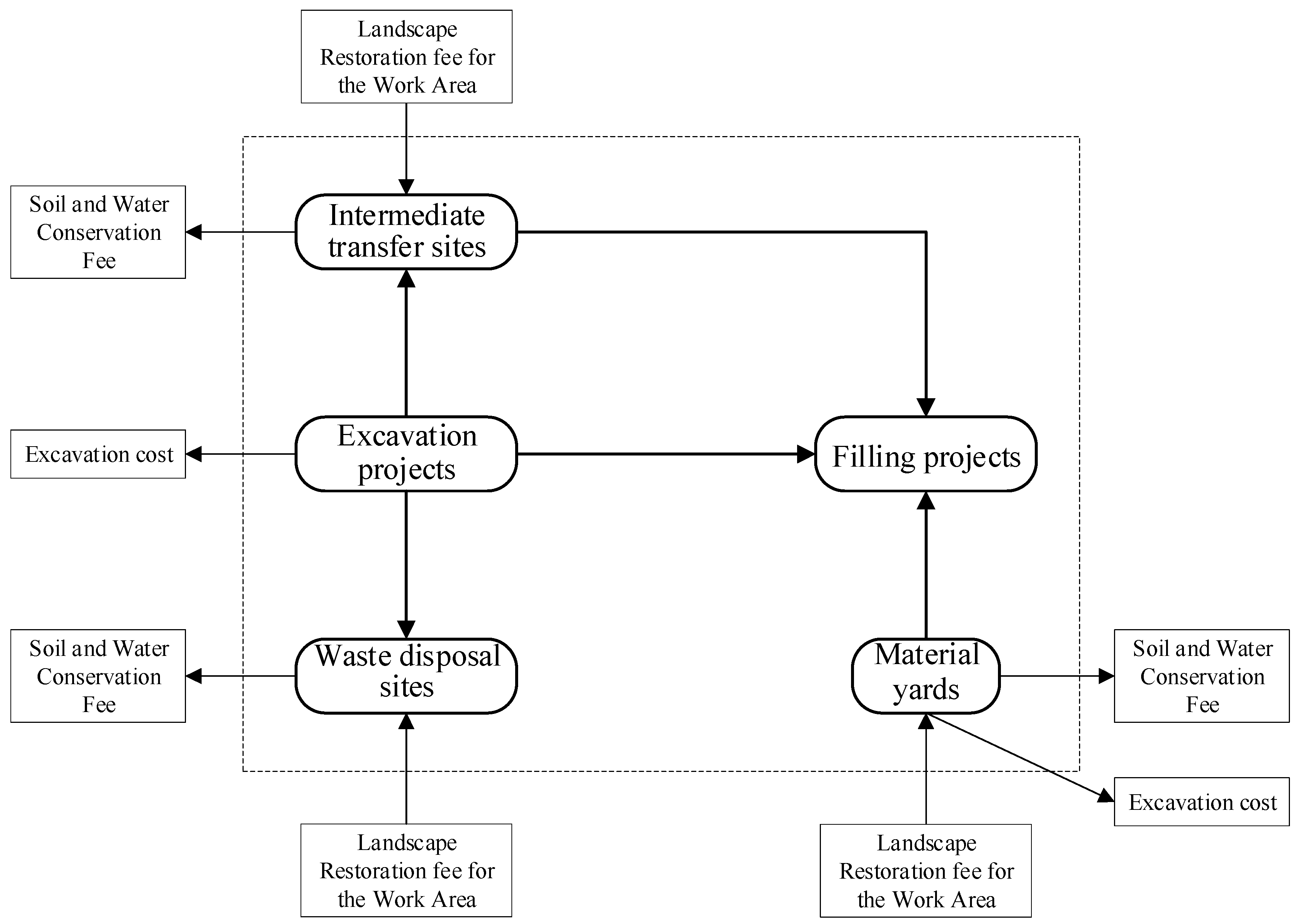

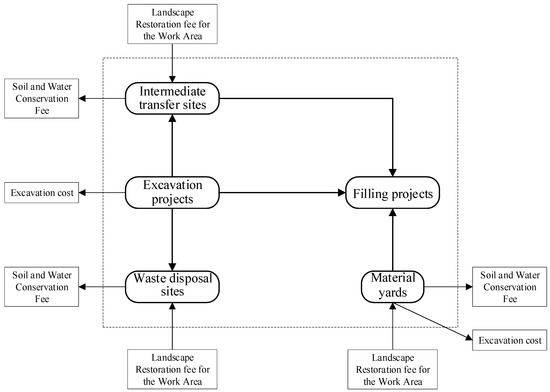

The earthwork allocation system consists of excavation projects, filling projects, transfer yards, waste disposal yards, and material yards [18,19]. Excavation project refers to a specific work area where soil or rock excavation is carried out to meet the needs of engineering construction. A filling project refers to the construction area where excavated or mined soil and stone materials are filled to designated locations to form a structure with design strength and stability. Transfer site refers to a temporary storage area for excavated materials that meet the design specifications. Waste disposal site refers to a specific area where soil and rock materials that do not meet design requirements and cannot be directly used for filling or other purposes are centrally processed. Material yard refers to a dedicated mining area set up to meet the needs of engineering filling. The material flow relationships of earthwork are shown in Figure 1, mainly including excavation projects to filling projects, excavation projects to transfer yards, excavation projects to waste disposal yards, transfer yards to filling projects/waste disposal yards, and material yards to filling projects.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of earthwork allocation system composition and material flow.

3. Optimization Model for Earthwork Allocation Considering Road Transportation Intensity

3.1. Soil and Water Conservation Fee

During the process of earthwork allocation, excavation, filling, and other construction activities can damage surface vegetation, reduce soil erosion resistance, and alter topography, resulting in the loss of soil and water conservation functions. The combination of natural factors such as climate conditions (such as rainfall, and strong winds), terrain slopes, and soil types with construction disturbances further increases the amount of soil erosion. A large amount of soil erosion has increased construction costs. This article mainly considers the calculation of soil and water conservation fees for waste disposal sites and intermediate transfer sites.

- Soil erosion equation:

In the formula, SL represents the amount of newly added soil erosion during the prediction period, unit: t; MS represents the average annual soil erosion per unit area, unit: t/(hm2·a), where hm2 represents hectare, and a represents year; MS0 represents the current soil erosion intensity, unit: t/(hm2·a); represents the correction coefficient, unit:/m, with a value range of (0, 1); DL represents the amount of soil and rock in the abandoned or intermediate transfer site, unit: cubic meters; and T represents the predicted period of soil erosion, unit: a [20]. If water and soil protection measures are taken before the construction of the project, the median of P and C factors in the calculation process is taken as 1. Detailed descriptions of the symbols are provided in Appendix A.

- 2.

- Soil and water conservation fee for waste disposal site:

In the formula, the construction period Gt has a value range of t = 1, 2, 3, …, T.

- 3.

- Water and soil conservation fee for the transition site:

3.2. Landscape Restoration Fee for the Work Area

The earthwork allocation activities will seriously damage the surface vegetation of the work area landscape, forming a loose accumulation of bare land landscape, leading to the deterioration of vegetation living conditions and further affecting the surrounding ecological environment. After construction, measures such as vegetation reconstruction and terrain reshaping will be taken to restore the damaged ecosystem in the work area and eliminate geological safety hazards. The calculation of landscape restoration costs for the waste disposal site and the transition site is as follows:

- 1.

- Cost of landscape restoration in the waste disposal area:

- 2.

- Cost of landscape restoration in the transit area:

3.3. Road Transportation Intensity

Define the road route map G = {V, E}, V represents the set of all road intersections, V = {v1, v2, v3, …, vz}, where z is the number of road intersections; E represents the set of roads, E = {e1, e2, e3, …, en}, where n is the number of roads. The excavation project Wi has a value range of i = 1, 2, 3, …, nW, the filling project Tj has a value range of j = 1, 2, 3, …, nT, the transfer yard Zk has a value range of k = 1, 2, 3, …, nZ, the waste disposal yard Ql has a value range of l = 1, 2, 3, …, nQ, and the material yard Cm has a value range of m = 1, 2, 3, …, nC.

Let the intersection point v between the starting point i and the ending point j be represented by Vij as the set of intersection points v between the starting point i and the ending point j, that is, Vij = {vij1, vij2, …, viju, …, vijz−1, vijz}, where z is the number of intersection points. Let both the starting point i and the ending point j be intersection points, with the starting point being vij1 and the ending point being vijz. Then, the route Eij between the starting point i and the ending point j is:

In the formula, the starting point is the first layer q1, the set of intersection points immediately after the starting point is the second layer q2, and the set of intersection points immediately after the y−1 layer is the y layer qy. Therefore, is the road segment from the first layer intersection q1 to the second layer intersection q2, and is the road segment from the y−1 layer intersection qy−1 to the y layer intersection qy. To simplify the symbolic expression, the intersection point

is simplified to v1, the intersection point is simplified to v2, then the intersection point is simplified to vy−1, then the road segment is simplified to e1, the road segment is simplified to e2, and further the road segment is simplified to ey−1. There is no connection between the intersection points of each layer, q1 = m1 = 1, q2 = 1, 2, …, m2, qy = 1, 2, …, my, qp−1 = 1, 2, …, mp−1, qp = mp = 1. m1 is the number of intersections in the starting layer q1, mp is the number of intersections in the endpoint layer qp, and my is the number of intersections in the y-th layer qy, where m1 + m2 + …+ my + …+ mp−1+ mp = z.

Taking the route planning with excavation project Wi as the starting point and filling project Tj as the ending point as an example, the road route planning map is shown in Figure 1. The starting excavation project Wi is the first layer q1, and its immediately posterior intersection point {v1} is the second layer q2. Then, is (Wi, v1), and is the section e2. The intersection points {v2, v3} immediately behind the second layer q2 represent the third layer q3. Then, are (v1, v2) and (v1, v3), and are the sections e3 and e4, which are divided into two different routes: and . Repeat the above steps, and when is the endpoint for filling project Tj, the route planning is completed. It can be concluded that there are two routes from excavation project Wi to filling project Tj, namely Eij1 = {e2, e3, e5} and Eij2 = {e2, e4, e7}.

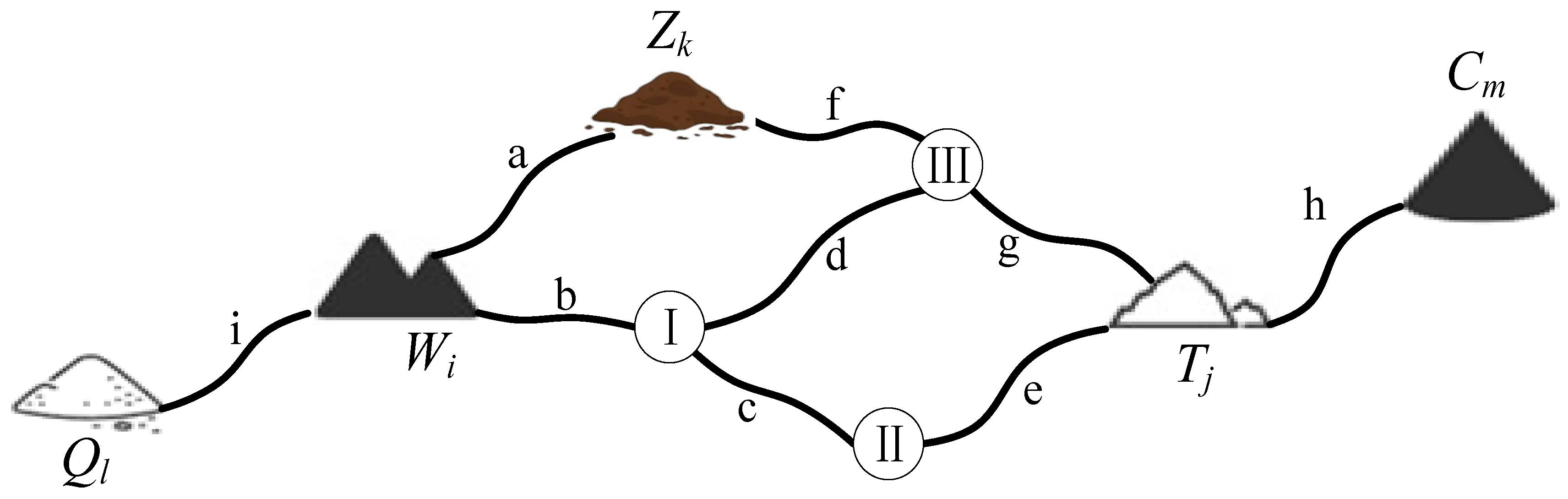

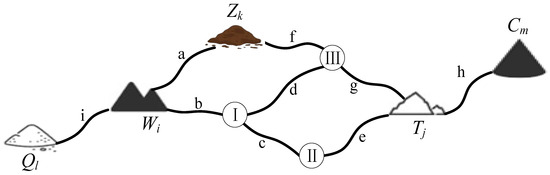

Taking the route planning with excavation project Wi as the starting point and filling project Tj as the ending point as an example, the road route planning map is shown in Figure 2. In the figure, Ⅰ, Ⅱ, and Ⅲ represent road intersections, and the letters a to i represent roads. The starting excavation project Wi is the first layer q1, and its immediately posterior intersection point {I} is the second layer q2, then v1 is (Wi, I), e1 is road segment b, the immediately posterior intersection points {II, III} of the second layer q2 are the third layer q3, then v2 are (I, II) and (I, III), e2 are road segments c and d, divided into two different routes Eij1 = {b, c, …, ey, …, ep} and Eij2 = {b, d, …, ey, …, ep}. Repeat the above steps, when vp is the ending filling project Tj, the route planning is completed, and it can be obtained that there are two routes from excavation project Wi to filling project Tj, namely Eij1 = {b, c, e} and Eij2 = {b, d, g}.

Figure 2.

Road route planning map.

Considering the transportation loss rate, the maximum road transportation intensity in the t-th month for all feasible routes from starting point i to endpoint j is as follows:

In the formula, in , ∈(0 ~ 0.15).

3.4. Optimization Model for Earthwork Allocation Cost

The goal of the earthwork allocation system is to minimize the total allocation cost. In the past, the earthwork allocation cost only considered the costs of earthwork excavation, transportation, and filling, ignoring the costs of soil erosion and landscape restoration in the work area, resulting in a significant difference between the actual and estimated earthwork allocation costs. Considering the costs of soil erosion and landscape restoration in the work area, the objective function is as follows, The meanings of the symbols in the formula are shown in Table A1 in Appendix A.

3.5. Optimization Model for Road Transport Intensity

The optimization function Q for road transportation intensity is

3.6. Cost Optimization Model Considering Road Transportation Intensity

- 1.

- Objective function

The optimization of the earthwork allocation system considers the lowest total cost of earthwork material allocation and the lowest peak transportation intensity of roads in the allocation system. In the road transportation network of the entire allocation system, a road peak transportation function is established based on road parameters, and combined with the earthwork allocation cost function for joint optimization, to construct the objective function min{F,Q}.

- 2.

- Constraints

Constraints include the quantities of each excavation project and filling project, the mining output limit of the stock yard, the capacity limit of the transfer yard and the waste disposal yard, and the non-negative constraints.

- 1.

- Equal excavation volume refers to the sum of the excavation volume of a certain excavation project during a certain period being equal to the sum of the transportation volume to all other possible locations during that period. Among them, represents the engineering quantity of the excavation project.

- 2.

- Equal filling amount refers to the sum of the filling amount of a certain filling project during a certain period of time being equal to the sum of all possible transportation volumes to that filling project during that period. Among them, represents the engineering quantity of the filling project.

- 3.

- Mining output limit of the quarry: The allocation volume from the quarry to the filling project cannot exceed the maximum capacity of the quarry. Among them, represents the material storage capacity of the material yard.

- 4.

- Capacity limit of waste disposal site: The amount of waste materials from all excavation projects, materials that cannot be directly used for filling, and other special earth and stone materials cannot exceed the maximum capacity of the waste disposal site. Among them, represents the capacity of the waste disposal site.

- 5.

- Capacity limitation of transfer site: Within the same time period, the difference between the allocation amount from the excavation project to the transfer site and the allocation amount from the transfer site to the filling project is greater than or equal to zero, and less than or equal to the maximum capacity of transfer site. Among them, represents the capacity of the transition field.

- 6.

- Non-negative constraint: Excavation projects, transfer sites, filling projects, waste disposal sites, and material yards all have a corresponding allocation of earthwork.

- 7.

- Facing the intersection V of the road section, prioritize choosing the route with the shortest total mileage of the transportation route.

- 8.

- In the set of intersection points v between starting point i and ending point j, the intersection point of the first layer q1 and the last layer qp should be the starting point i and the ending point j.

4. Model Solving Based on Improved Ant Colony Algorithm

The ant colony algorithm involves decision variables, including NS binary variables (representing whether the t-th step starts from node i) and S continuous variables (representing the transportation volume of the t-th step). The specific implementation of the algorithm is as follows:

- 1.

- Informational modeling: The concentration of pheromones on path (i, j) represents the advantages and disadvantages of historical blending schemes, and the higher the concentration, the greater the probability of the path being selected.

- 2.

- Heuristic information: Introduce the reciprocal of transportation cost as a local guide, prioritizing the path with lower cost.

- 3.

- State transition rule: The probability of ant k selecting the next node j at node i is

In the formula, and represent the weights of control pheromones and heuristic information, respectively.

- 4.

- Dynamic update mechanism: After each iteration, pheromones decay according to their volatility , and excellent paths are enhanced based on the quality of ant paths.

In the equation, Q represents the pheromone intensity constant, and represents the total cost of ant k (including constraint penalty terms).

The improved ant colony algorithm introduces a phased pheromone volatilization and enhancement strategy, and its solution process is divided into the following steps:

- 1.

- Initialization parameters: Set the parameters of the ant colony algorithm, including the maximum number of iterations MaxDT, heuristic factor , pheromone evaporation coefficient , and penalty factor. Simultaneously input relevant information of earthwork nodes, such as node type (excavation, filling, transfer, waste disposal), location, initial earthwork volume, and maximum capacity. Initialize the pheromone matrix and heuristic information matrix , representing the pheromone concentration and heuristic information (such as the reciprocal of transportation costs) on the paths between nodes, respectively. Initialize the number of ants m and randomly place them at the excavation node.

- 2.

- Iterative search: In each iteration, each ant starts from the current node and selects the next node according to the state transition rule. The ant calculates the transition probability from the current node to the unvisited node, which is determined by the pheromone concentration and the heuristic information .

After selecting the next node based on the transition probability, ants will update the information of the node, such as updating the remaining earthwork volume of the node based on the transportation volume, and checking whether the constraints are met, such as the capacity limit of the transition site and the capacity limit of the waste disposal site. If the constraint conditions are violated, the punishment will increase and the fitness of the path will be reduced. Ants will repeat the above steps until all nodes are accessed. Finally, calculate the path cost for each ant, including transportation and penalty costs, and update the optimal path and cost.

- 3.

- Pheromone update: After each iteration, update the pheromone matrix according to the pheromone update rule. The pheromone increment is inversely proportional to the ant path cost . The formula for calculating the increment of pheromones is

In the equation, Q represents a constant.

- 4.

- Termination condition: Determine whether the maximum iteration count MaxDT has been reached or whether a satisfactory optimization solution has been found.

- 5.

- Result output: Output the optimal path and cost, including the transportation volume and construction sequence between each node. At the same time, use data charts to visually display the allocation plan, clearly expressing information such as transportation routes, transportation volume, and construction sequence.

Inspired by Ahmed’s research on adaptive adjustment of pheromone evaporation rate, this paper introduces a dynamic decay factor to balance the algorithm’s exploration and exploitation capabilities [21]. To effectively handle complex constraints such as capacity constraints, this paper draws on the idea of using penalty coefficients to handle constraints in Li et al., and sets penalty factors to discard infeasible solutions [22]. Throughout the process, the ant colony algorithm simulates the foraging behavior of ants, utilizing the positive feedback mechanism of pheromones and the guidance of heuristic information to gradually search for optimized solutions for earthwork allocation. Through continuous iteration, the algorithm can find the construction path and transportation volume allocation that minimizes the total allocation cost, while considering the construction sequence and nonlinear constraints, improving the economic feasibility and practical application value of the allocation plan.

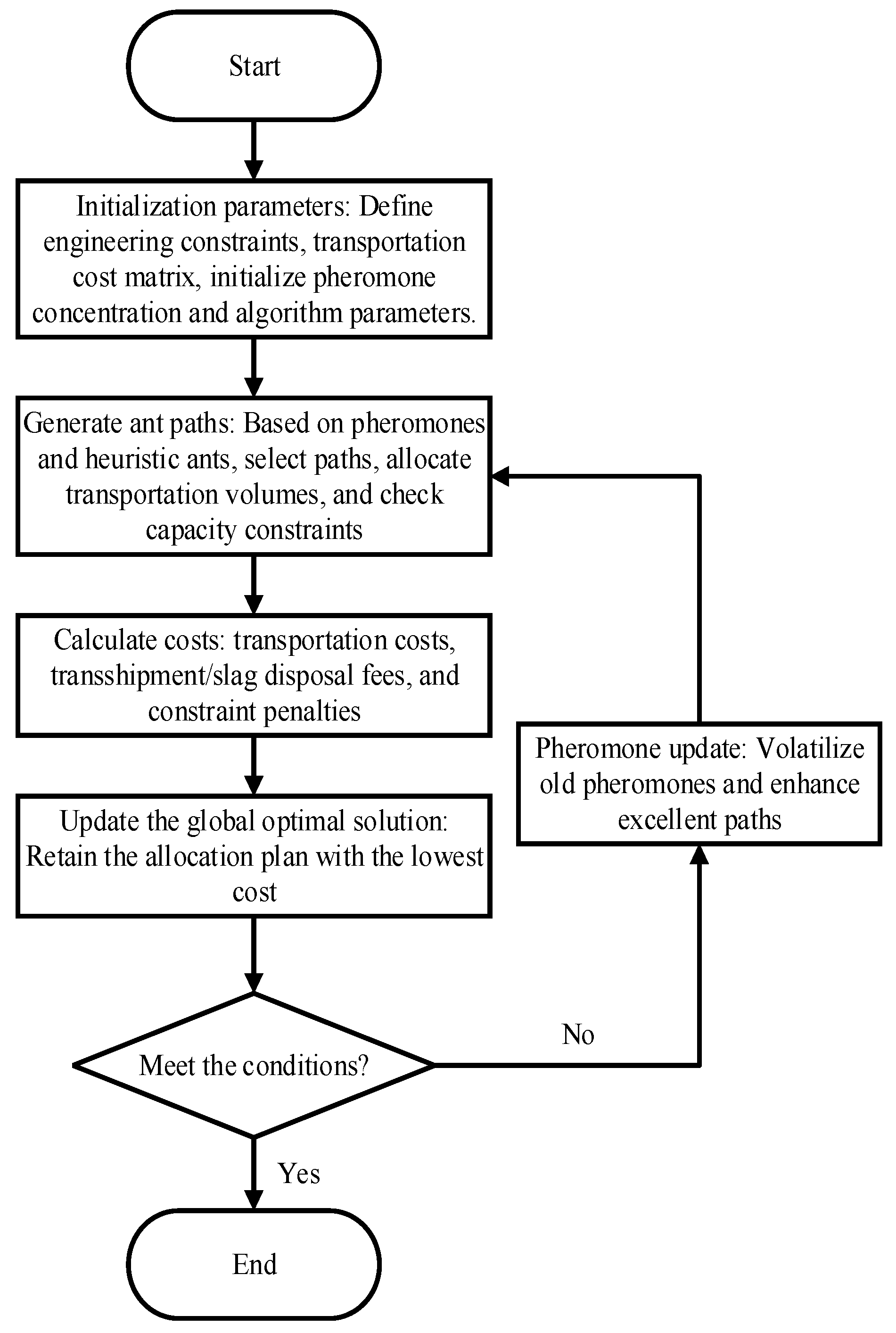

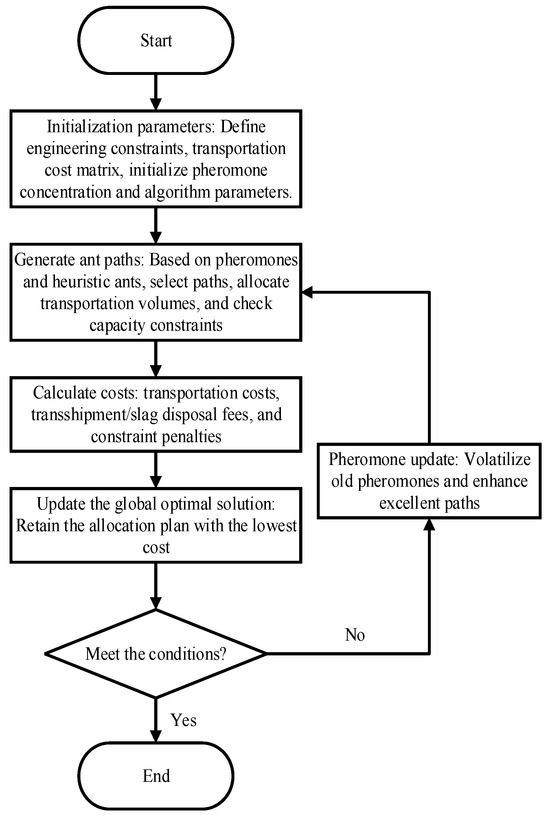

The improved ant colony algorithm in this paper comprehensively uses three strategies: dynamic pheromone update, penalty factors, and NumPy array vectorization. The combination of these three is necessary and has a synergistic effect: the dynamic update mechanism ensures that the algorithm can jump out of local optima and avoid premature convergence; the penalty factors ensure the feasibility of search paths under complex multi-constraint conditions; and NumPy vectorization is the key to achieving efficient computation of the algorithm. In the core steps of the algorithm, such as state transition probability calculation (Equation (19)) and global pheromone update (Equations (20) and (21)), traditional implementation requires writing multiple layers of loops to traverse each ant and each path node, resulting in low computational efficiency. In this study, by constructing a probability matrix and a pheromone increment matrix, the serial computation for a single ant is transformed into a parallel matrix operation for the path selection of the entire ant population. This vectorization processing fully exploits the Single Instruction Multiple Data Stream (SIMD) feature of modern cpus and avoids the overhead caused by the Python 3.12.6 interpreter loop. This combination makes the improved algorithm not only have high solution quality, but also fast computing speed and good scalability, thus being able to deal with the large-scale earthwork allocation problems that may occur in actual engineering. The optimization process diagram of earthwork allocation based on an improved ant colony algorithm is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Optimization flow chart of earth and rock allocation based on improved ant colony algorithm.

5. Example Analysis

5.1. Project Overview

The main buildings of the upper reservoir in a pumped storage power station project consist of a dam, reservoir bank protection, and reservoir basin anti-seepage engineering. The dam is a concrete face rockfill dam with a dam crest elevation of 860.00 m, a maximum dam height of 142.00 m (dam axis), a dam crest width of 10.00 m, and a dam crest length of 421.00 m. The slope ratio of the upstream and downstream dam slopes is 1:1.40. The filling materials of the dam body are divided from upstream to downstream into cushion zone, special cushion zone, transition zone, main rock pile zone, downstream rock pile zone, and downstream grid beam slope protection zone.

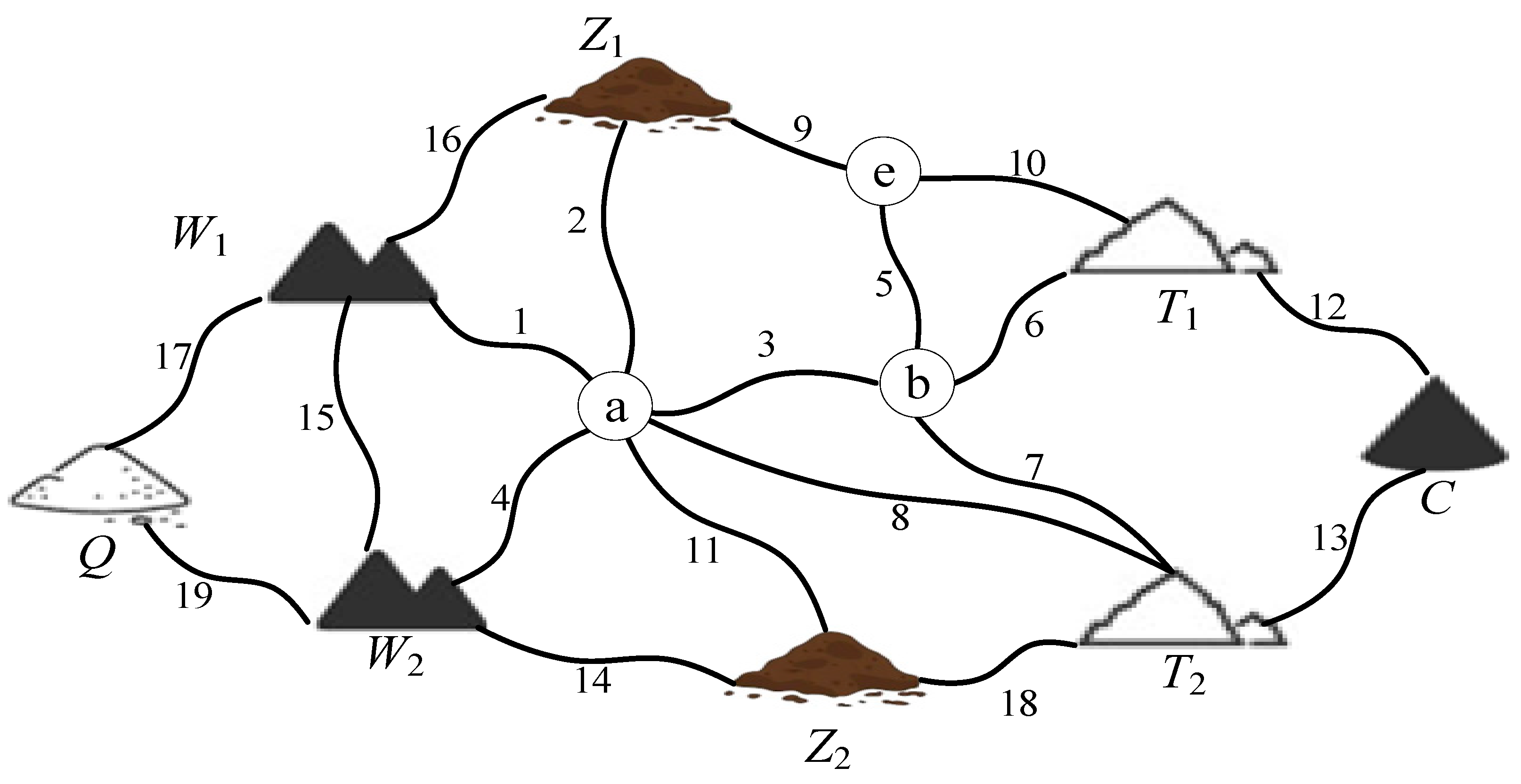

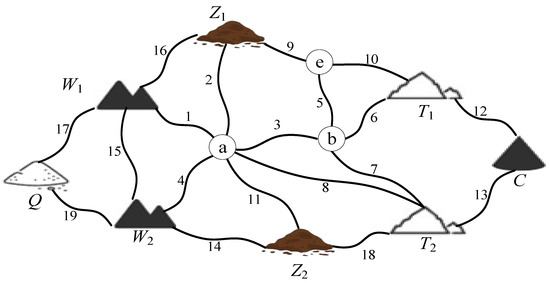

The construction period of this project is 12 months, with two excavation projects, two filling projects, one material yard, two transfer yards, and one waste disposal yard. The transportation road route map is shown in Figure 4, and the construction schedule is shown in Table 1. In the figure, the letters a, b, and e represent road intersections, and the numbers 1 to 19 represent roads. The storage capacity of the material yard, the capacity of the transfer yard and the waste disposal yard are shown in Table 2, and the unit price table between each element is shown in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Transportation road route map.

Table 1.

Construction Schedule.

Table 2.

Storage Capacity of Material Yard, Capacity of Transfer Yard and Waste Disposal Yard.

Table 3.

Unit Price Table between Each Element.

5.2. Optimization of Earthwork Allocation Considering Road Transportation Intensity

- Optimization results of deployment

The relevant parameters of the improved ant colony algorithm are shown in Table 4. The optimization calculation results of earthwork allocation without considering road transportation intensity are shown in Table 5, and the optimization calculation results of earthwork allocation considering road transportation intensity are shown in Table 6.

Table 4.

Related Parameters of Improved Ant Colony Algorithm.

Table 5.

Optimization Calculation Results of Earthwork Allocation without Considering Road Transportation Intensity.

Table 6.

Optimization Calculation Results of Earthwork Allocation Considering Road Transportation Intensity.

- 2.

- Optimization result analysis

By comparing and analyzing the blending results in Table 5 and Table 6, the following conclusions can be made:

- In the optimization calculation results of earthwork allocation without considering road usage, the maximum transportation intensity during the peak transportation period is 268,000 m3/month from excavation project W1 to filling project T1 in the fourth month, and 104,000 m3/month from excavation project W2 to filling project T2 in the fifth month. When considering road usage, according to Formula (7), the maximum transportation intensity limit Q0 during the peak transportation period from excavation project W1 to filling project T1 in the fourth month is 262,000 m3/month, and the route is W1→1→3→6→T1. The maximum transportation intensity limit Q0 during the peak transportation period from excavation project W2 to filling project T2 in the fifth month is 99,000 m3/month, and the route is W2→4→8→T2.

After considering the intensity of road transportation, the allocation of excavation project W1 to filling project T1 in the fourth month has been reduced from the original 268,000 m3/month to 262,000 m3/month. The allocation of excavation project W1 to transfer project Z1 in the fourth month has increased from 12,000 m3/month to 18,000 m3/month. The allocation of excavation project W2 to filling project T2 in the fifth month has been reduced from 104,000 m3/month to 99,000 m3/month. The allocation of excavation project W2 to intermediate transfer site Z2 has increased from 178,000 m3/month to 183,000 m3/month now. In order to meet the schedule of filling project W1 and filling project T2 in April, an additional allocation route will be added, Z1→9→e→10→T1, with an allocation volume of 6000 m3/month. In May, an additional allocation route will be added, Z2→18→T2, with an allocation volume of 5000 m3/month.

- 2.

- The proportion of earthwork directly used for filling in excavation projects W1 and W2 reached 92.1% and 88.4%, respectively. For example, the unit price of earthwork allocation from excavation project W2 to filling project T2 is 12 CNY/m3, and the unit prices of earthwork allocation from intermediate transfer site to filling project T1 and filling project T2 are 20 CNY/m3 and 18 CNY/m3, respectively. This reduces the transportation costs from the intermediate transfer site and material yard to the filling project, as well as the earthwork management costs of the intermediate transfer site and material yard.

- 3.

- (i) Pre-deployment stage. At the initial stage of construction, when the filling demand is zero from January to February, the accumulated excavation volume of 582,000 m3 for excavation project W1 will be temporarily stored in the transfer site Z1 to avoid waste disposal costs and reserve resources for subsequent filling. (ii) Peak period for filling. The storage capacity of the transition site during the construction period from July to December meets the peak demand for filling, such as the allocation of 1.564 million m3 from transition site Z1 to filling project T1 from July to December, prioritizing the high-priority demand (filling project T1 accounts for 67% of the entire filling demand). (iii) End of deployment. In December, 106,000 cubic meters were directly filled from excavation project W2 to filling project T2, combined with flexible supplementation from the borrow site, to balance the dynamic differences between excavation and filling, and to improve construction continuity by 15%.

- 4.

- (i) Nonlinear constraint processing, directly incorporating soil erosion rate (0.05) and landscape restoration rate (0.1), improves optimization accuracy by 14% compared to traditional linear programming. Multi-objective collaborative optimization: (ii) Generate multiple sets of approximate optimal solutions (such as prioritizing the use of transition Z1 or transition Z2), support dynamic decision-making (such as excavating project W2 to transition Z2 or borrowing site to filling project T2 in May), and increase scheme diversity by 22%. (iii) Real-time status synchronization, through a dynamic pheromone update mechanism, provides real-time feedback on transition capacity (such as 674,000 cubic meters of inventory in transition 1 in September), avoiding the risk of capacity conflicts in static planning and significantly enhancing engineering adaptability. After 4000 iterations of the ant colony optimization algorithm, the minimum cost of earthwork allocation optimization considering road transportation intensity (Table 6) was CNY 15.679 million. Compared with the minimum cost of earthwork allocation optimization without considering road transportation intensity (Table 5), which was CNY 15.658 million, the allocation cost increased by CNY 21,000, an increase of 0.91%. From the perspective of earthwork allocation in actual engineering, considering road transportation intensity, the allocation cost increased, and the proportion of earthwork directly entering the dam increased. The maximum capacity limit of the waste disposal site and intermediate transfer site was not exceeded, and the transportation route was more reasonable. The results of allocation optimization were more in line with the actual construction situation.

To verify the effectiveness of the improved ant colony algorithm (IACO) in this paper, it is compared with the standard genetic algorithm (GA) and the standard particle swarm optimization algorithm (PSO).

Analysis of Table 7 shows that in terms of solution quality, the IACO in this paper obtains the lowest average cost and the smallest standard deviation, indicating that it has the highest solution accuracy and the best stability. In terms of computational efficiency, PSO has the shortest time consumption due to its simple structure, but its solution quality is inferior to IACO; the running time of IACO is between that of PSO and GA, but its significant advantage in solution quality makes its comprehensive performance the best. This proves that the improvement strategy combining dynamic update, penalty factors, and vectorization adopted in this paper is effective.

Table 7.

Performance Comparison of Different Optimization Algorithms.

6. Conclusions

This article elaborates on the composition of the earthwork allocation system and the relationship between material flow direction. We have developed a calculation model for soil and water conservation fees, which can protect surface vegetation, improve soil erosion resistance, and ensure the sustainability of soil and water conservation functions. A calculation model for the cost of landscape restoration in the work area has been constructed, and measures such as vegetation reconstruction and soil and water conservation have been taken to restore the damaged ecosystem in the work area and eliminate geological safety hazards. We have researched the method of road transportation route planning, constructed a road transportation intensity calculation model considering transportation loss rate, and reduced the monthly peak transportation load of the road network during the construction period, thereby providing a basis for avoiding traffic congestion at the planning level. A joint optimization model was constructed with the objectives of minimizing total allocation costs and minimizing peak transportation intensity on roads, taking into account the coordinated optimization of soil and water conservation fees, work area landscape restoration fees, and road transportation intensity. By organically combining dynamic volatility adjustment, penalty factor setting, and NumPy array vectorization, both the computational efficiency and robustness of the ant colony algorithm have been significantly enhanced. This research provides theoretical support and practical reference for the efficient allocation and transportation system optimization of earthwork resources in complex engineering.

Author Contributions

B.W.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft. S.N.: methodology, data curation. H.Y. and X.N.: visualization, writing—review and editing, T.F.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research on Digitalization and Intelligentization-Driven Collaborative Governance in the Wen’anwa Flood Storage (2025-85), and the Scientific Research Project of the Power CHINA Northwest Engineering Corporation Limited, the Power CHINA Roadbridge Group Co., Ltd. (DJLQKJ2023), the Power Construction Corporation of China, Ltd. (DJKJ2023), the Training Programme for Young Backbone Teachers of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province (2024GGJS061) and the High-level Talent Research Start-up Project of North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power (202310024).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Symbol Explanation

Due to the large number of symbols involved in the model, some symbols are shown in Table A1.

Table A1.

Meanings of Some Model Parameters.

Table A1.

Meanings of Some Model Parameters.

| Symbol | Meaning | Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wi | Excavation projects | R | Rainfall erosivity factor |

| Tj | Filling projects | K | Erodibility factor of soil and water |

| Zk | Transfer yards | L | Slope length factor |

| Ql | Waste disposal yards | S | Slope gradient factor |

| Cm | Material yards | C | Plant measure factor |

| Gt | Construction period | P | Soil and water conservation measure factor |

| Material allocation amount from the excavation project to the waste disposal site within the t-th month | Material allocation amount from the excavation project to the intermediate transfer site within the t-th month | ||

| Cost of losing 1 m3 of water and soil in the abandoned waste disposal site | Cost of 1 m3 of water and soil loss in the transition field | ||

| Average annual soil erosion of the waste disposal site | Average annual soil erosion of the transition zone | ||

| Current soil erosion intensity per unit area of the waste disposal site | Current soil erosion intensity per unit area of the transition zone | ||

| Cost of restoring the landscape of one square meter of the waste dump work area | Cost of restoring the landscape of one square meter of the transfer yard work area | ||

| Earthwork transportation volume of the m-th section eijm in the Eijk route within the t-th month | Material loss rate from starting point i to endpoint j in the t-th month | ||

| Transportation unit prices from excavation project to filling project | Material allocation quantities on route E from excavation project to filling project | ||

| Transportation unit prices from excavation project to the intermediate transfer site | Material allocation quantities on route E from excavation project to the intermediate transfer site | ||

| Transportation unit prices from excavation project to waste disposal site | Material allocation quantities on route E from excavation project to waste disposal site | ||

| Transportation unit prices from intermediate transfer site to filling project | Material allocation quantities on route E from intermediate transfer site to filling project | ||

| Transportation unit prices from material yard to filling project | Material allocation quantities on route E from material yard to filling project |

References

- Mayer, R.H.; Robert, M.S. Earth moving logistics. J. Constr. Div. 1981, 107, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreb, A.A. Linear programming model for finding optimal roadway grades that minimize earthwork cost. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1996, 93, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.Z.; Lu, F.; Jin, L.H. Dynamic earthwork allocation model based on simple method and its application. Water Resour. Power 2014, 32, 123–125+113. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.S.; Zhong, D.H.; Zhang, J.; Hong, W.; Li, M.C. Study on the model and its visualization for dynamic allocation of earth. Chin. J. Eng. 2003, 12, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, D.; Vaughan, D.E.; Jacobson, S.H.; Wakefield, R.R.; Sewell, E.C. Solving the shortest route cut and fill problem using simulated annealing. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2003, 145, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.; Rodrigues, B.; Zhang, J. Tabu search embedded simulated annealing for the shortest route cut and fill problem. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2005, 56, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.C.; Zhang, P.C.; Xu, Y.M. Earthwork dynamic allocation based on the Monte Carlo tree search algorithm and its verification. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 51, 391–401. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.B.; Zhai, Z.H.; Zhang, W.Y.; Gao, Z. Research on the earth-rock allocation model of rockfill dams based on green construction. China Rural. Water Hydropower 2015, 7, 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, D.G.; Williams, E.H.; Kaboli, A.S. Minimum operational emissions in earthmoving. Constr. Res. Congr. 2012, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar]

- Burdett, R.; Kozan, E.; Kenley, R. Block models for improved earthwork allocation planning in linear infrastructure construction. Eng. Optim. 2015, 47, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.L.; Liu, X.G.; Chen, G.; Cao, S.; Zhu, Y. Model for joint optimization of path transportation intensity and earth-rock work allocation of rockfill dam. Eng. J. Wuhan Univ. 2006, 5, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk, M.; Moselhi, O. Multiobjective optimization of earthmoving operations. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2004, 130, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.H.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, R.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, B. Earthwork allocation method based on ant colony algorithm. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2019, 36, 72–77+84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Study and Application of Earthwork Allocation Method Based on Intelligent Optimization Algorithm. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, K. Swarm Intelligence Algorithms for the 3D Route Location in Highway (Railway) Engineering Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X. The Study and Realize of Highway Earthwork Allocation Based on GIS. Master’s Thesis, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Li, Y.; Yao, B.W.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L. Optimal allocation model of earthwork and its application based on dynamic path planning. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.C.; Zhang, Y.X.; Yang, Y.H. Quantitative analysis of highway engineering construction safety risk based on combinatorial weighted two-dimensional cloud model. Henan Sci. 2024, 42, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Zhang, J.C.; Yang, Y.H.; Li, D.; Wang, B. Dynamic evaluation of highway engineering construction safety risk based on fuzzy dynamic Bayesian network. Henan Sci. 2024, 42, 653–659. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.L. Investigation on hydropower projects soil erosion prediction program. Water Power 2006, 5, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrovouniotis, M.; Yang, S. Ant colony optimization with self-adaptive evaporation rate in dynamic environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Dynamic & Uncertain Environments, IEEE, Orlando, FL, USA, 9–12 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, R.; Cheng, X.; Wu, Z.; Du, X. Improved ant colony optimization for safe path planning of AUV. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).