Dynamic Characteristics and Parametric Sensitivity Analysis of Underground Powerhouse in Pumped Storage Power Stations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Basic Information and Computational Model of the Underground Powerhouse

3. Theoretical Foundations of Finite Element Analysis

3.1. Theoretical Background of Modal Analysis

3.2. Theoretical Background of Dynamic Response Analysis

4. Dynamic Characteristics of the Underground Powerhouse

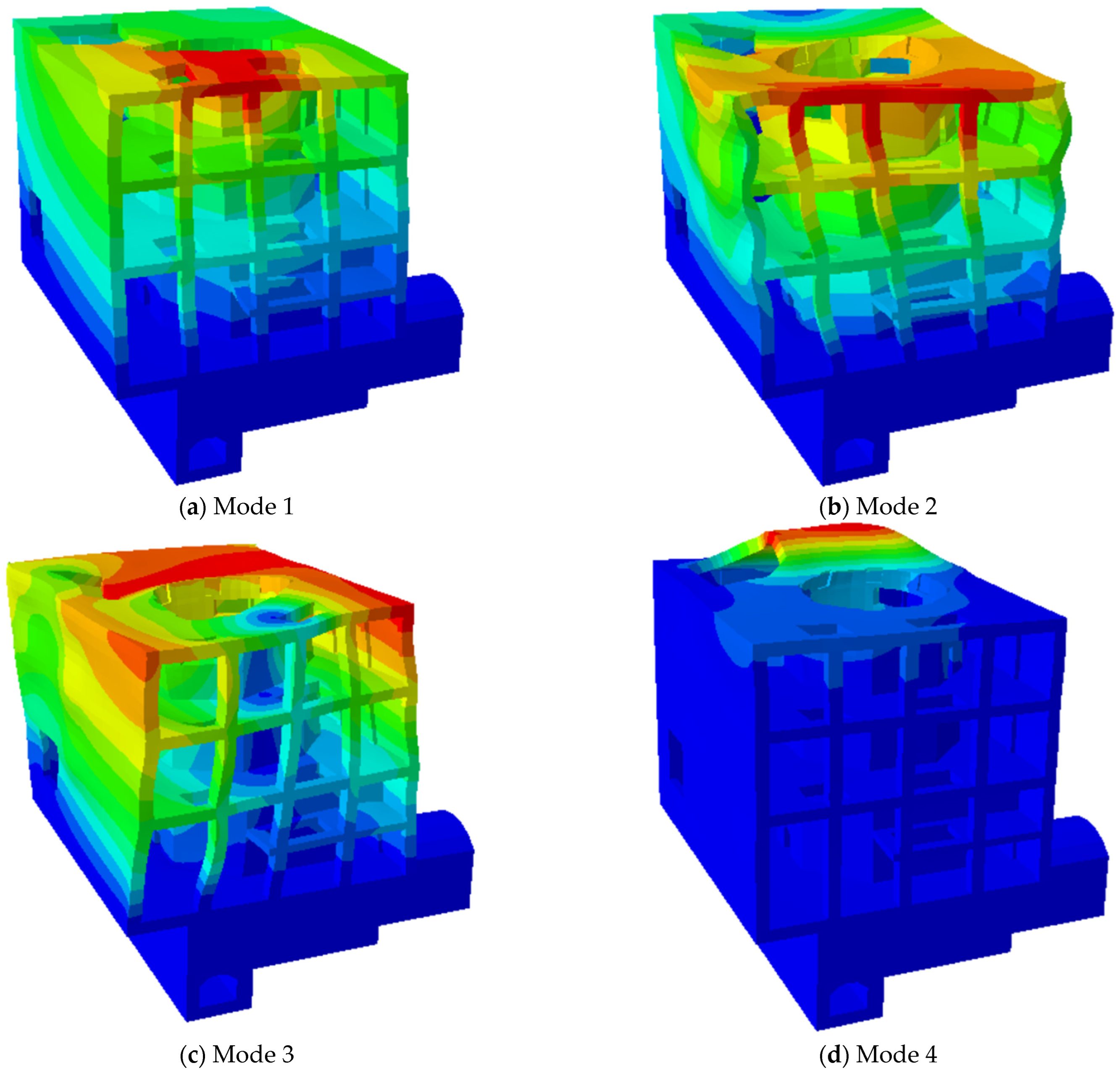

4.1. Natural Vibration Characteristics and Resonance Assessment of the Powerhouse Structure

4.2. Dynamic Response Analysis of the Underground Powerhouse Structure

5. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Dynamic Characteristics of the Underground Powerhouse Structure

5.1. Sensitivity Analysis of the Model Boundary Extent

5.1.1. Effect of Zone of Surrounding Rock on Natural Vibration Characteristics of the Powerhouse Structure

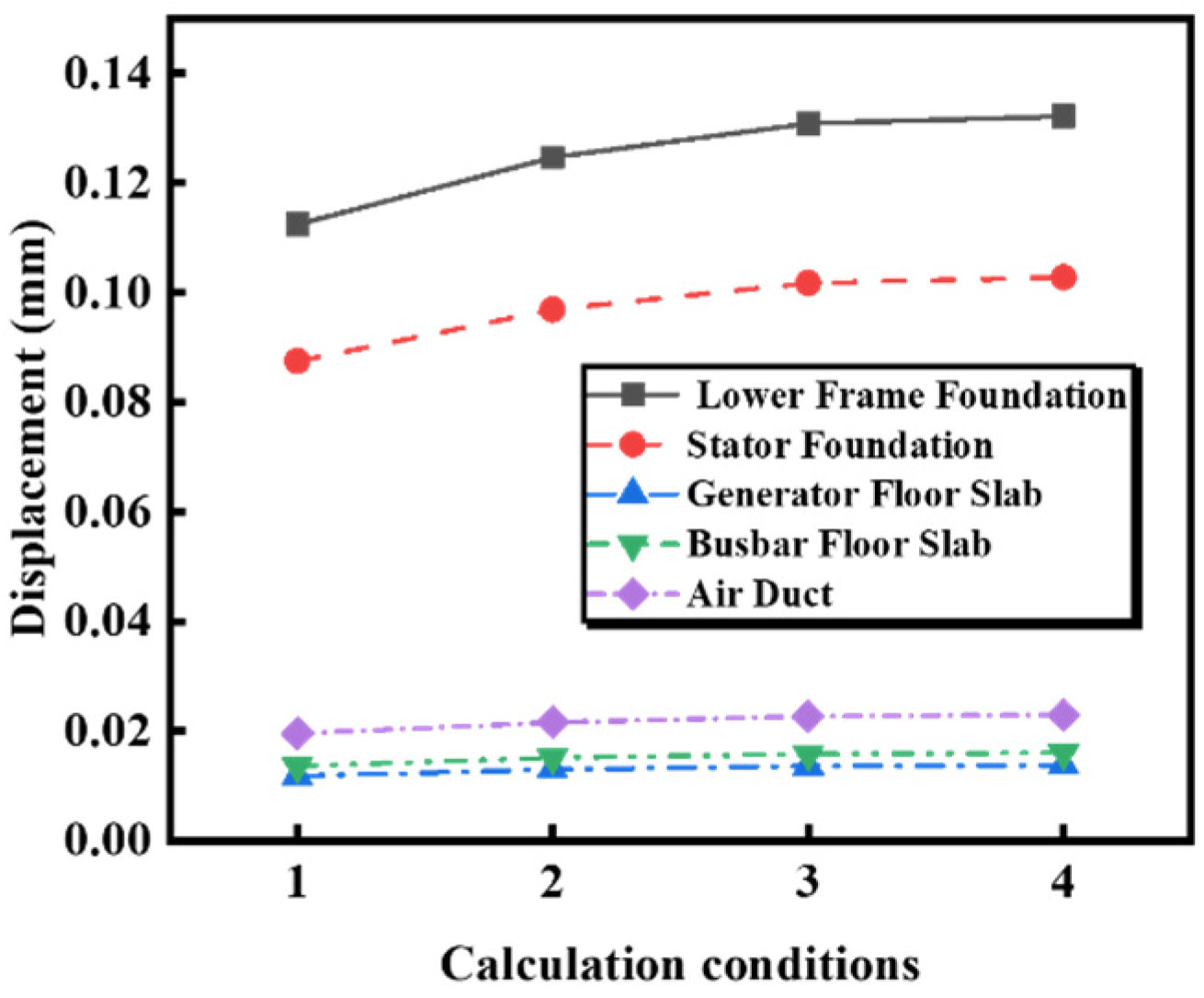

5.1.2. Effect of Zone of Surrounding Rock on Dynamic Displacement

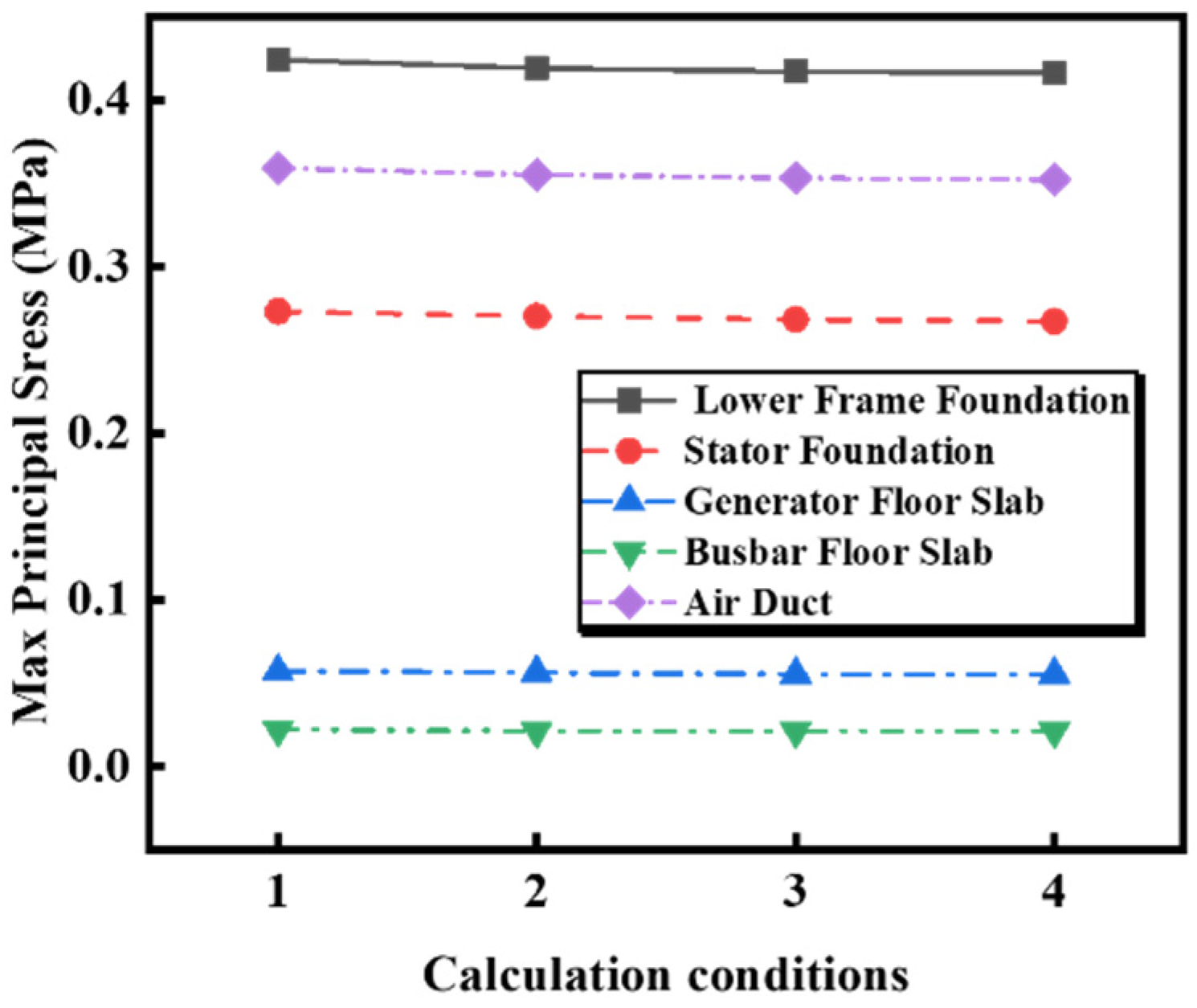

5.1.3. Effect of Zone of Surrounding Rock on Dynamic Stress

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis of the Surrounding Rock Elastic Modulus

5.2.1. Effect of Surrounding Rock Elastic Modulus on Natural Vibration Characteristics of the Powerhouse Structure

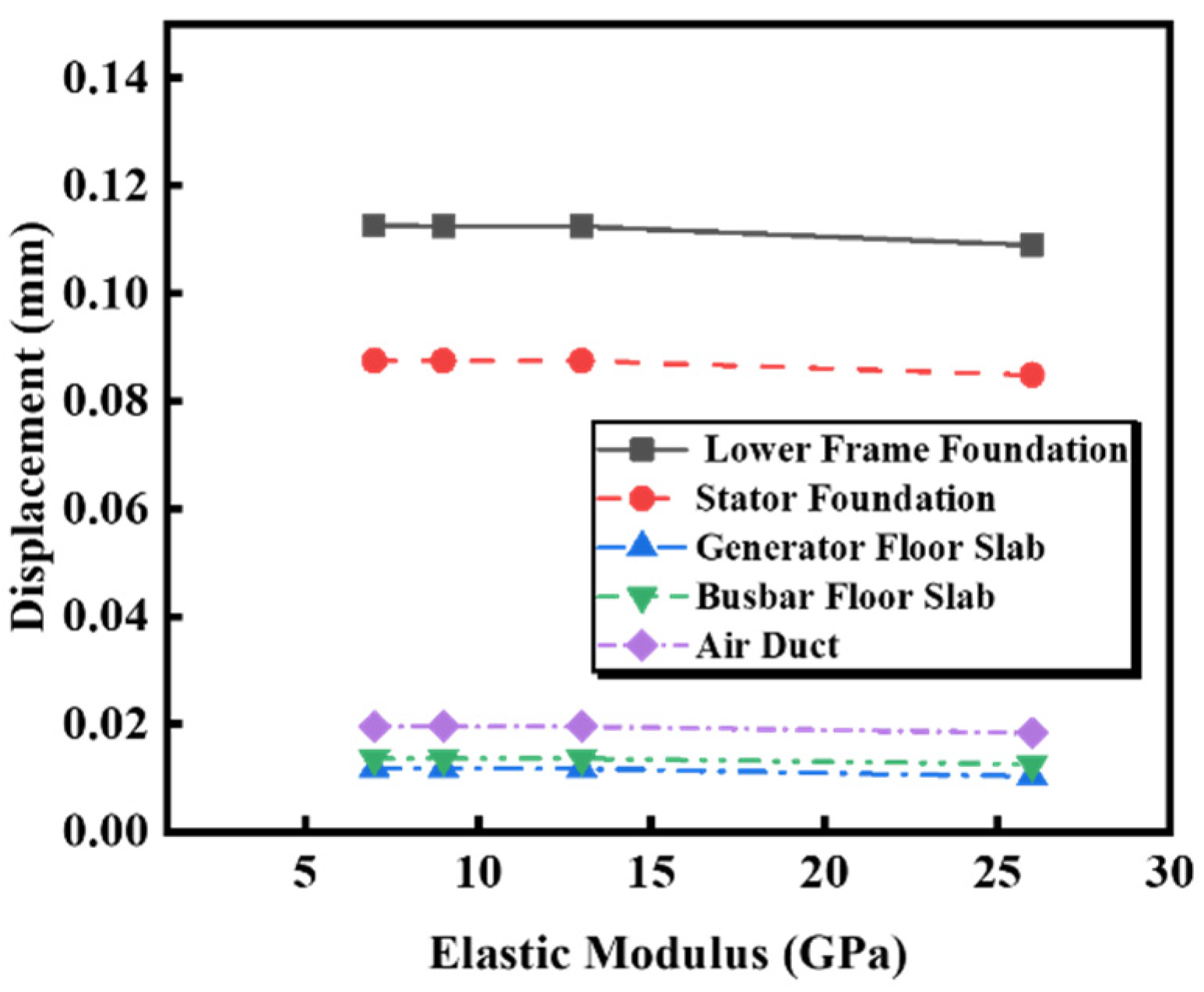

5.2.2. Effect of Surrounding Rock Elastic Modulus on Dynamic Displacement

5.2.3. Effect of Surrounding Rock Elastic Modulus on Dynamic Stress

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis of the Dynamic Elastic Modulus of Concrete

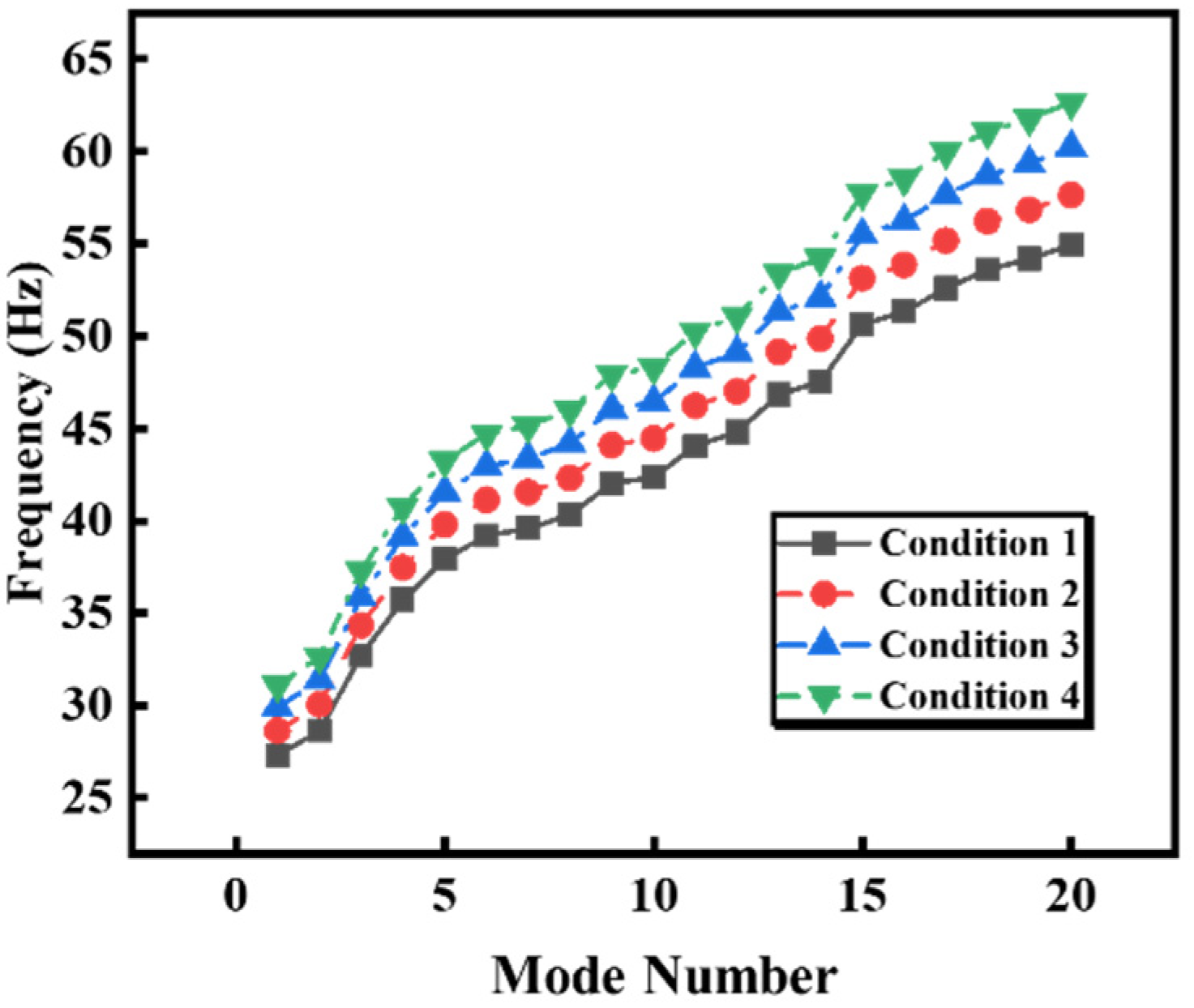

5.3.1. Effect of Dynamic Elastic Modulus on Natural Vibration Characteristics of the Powerhouse Structure

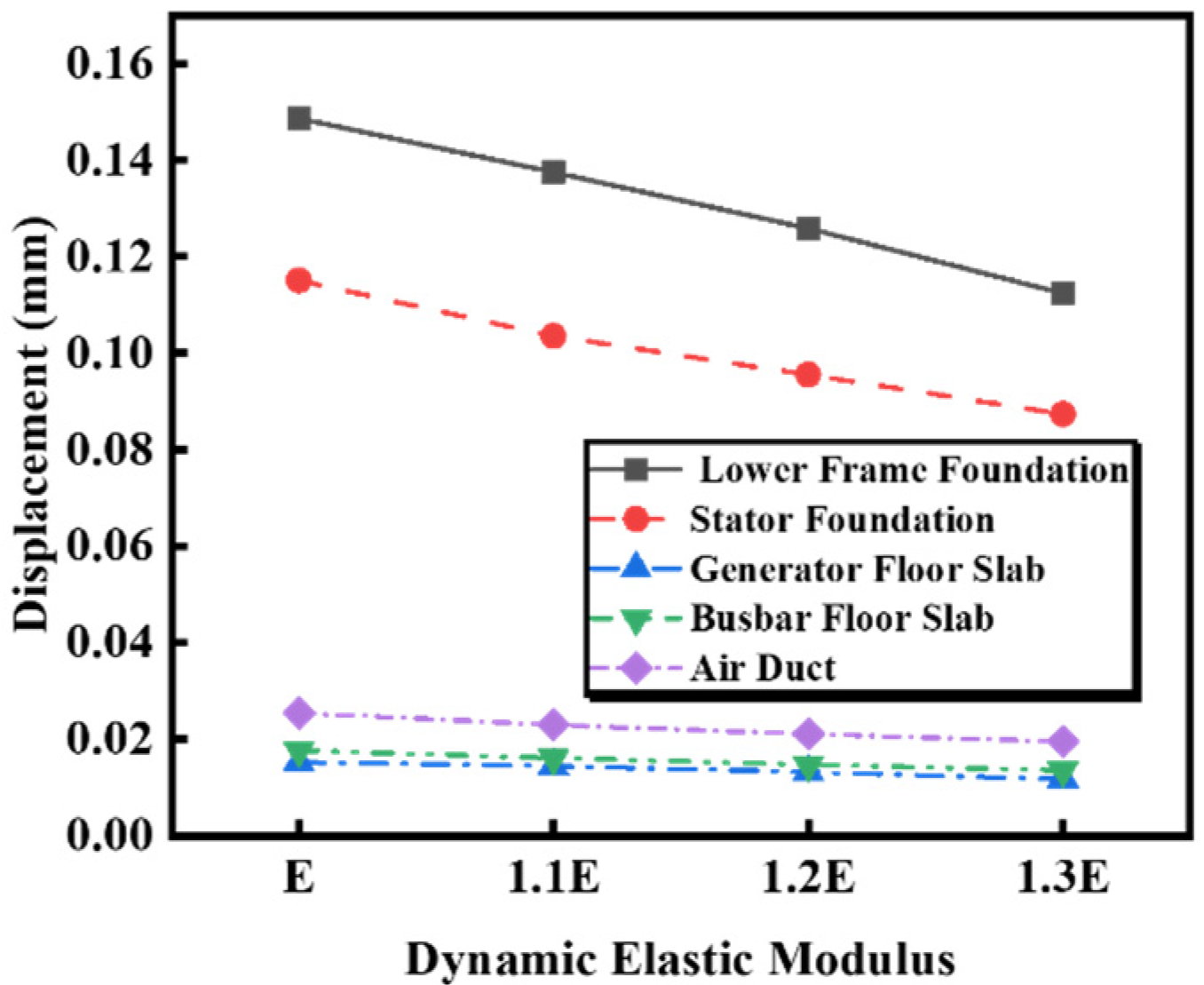

5.3.2. Effect of Dynamic Elastic Modulus on Dynamic Displacement

5.3.3. Effect of Dynamic Elastic Modulus on Dynamic Stress

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis of the Damping Ratio

5.4.1. Effect of Damping Ratio on Natural Vibration Characteristics of the Powerhouse Structure

5.4.2. Effect of Damping Ratio on Dynamic Displacement

5.4.3. Effect of Damping Ratio on Dynamic Stress

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Expanding the model boundary reduces the natural frequency but increases the dynamic displacement of the structure. The effects saturate beyond a boundary extent of twice the unit span, which is recommended as the optimal zone for balancing computational accuracy and efficiency.

- (2)

- An increase in the elastic modulus of the surrounding rock raises the structure’s natural frequency and slightly reduces dynamic displacement. Its influence on dynamic stress is limited, causing a slight decrease in the upper structure and a minor increase or stability in the lower structure.

- (3)

- The natural frequency of the structure exhibits a square-root relationship with the dynamic elastic modulus of concrete, while the dynamic displacement is inversely proportional to it. The parameter has a negligible influence on dynamic stress, with the increment below 4%.

- (4)

- The damping ratio has no effect on the natural vibration characteristics of the structure. Its influence on both dynamic displacement and dynamic stress is negligible within the typical range considered for this type of structure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.W.; Yang, J. Developments and characteristics of pumped storage power station in China. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Beijing, China, 16–19 November 2017; p. 12089. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y.G.; Kong, Z.G.; Liu, Z.Q.; Wei, C.M.; Zhang, J.F.; An, G.C. Pumped storage power stations in China: The past, the present, and the future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.K.; Sheng, X.; Qiao, Z.Y. Development Situation and Relevant Inspiration of Pumped Storage Power Station in the world. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Changchun, China, 21–23 August 2020; p. 12017. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, C.; Xu, X.W.; Zhang, S.X.; Qian, H.; Duan, Z.H. Current situation of small and medium-sized pumped storage power stations in Zhejiang Province. J. Energy Storage 2024, 78, 110070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.P.; Su, C.; Zhang, H.; Cao, E.H.; Yuan, R.Y.; Xu, Y.Q. Analysis of structural characteristics of underground cavern group by simulating all cavern excavation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4610557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.T.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, Y.J. Construction of large underground structures in China. In Rock Mechanics and Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; Volume 5, pp. 181–241. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, J.T.; Xiao, M. Analysis of seismic damage of underground powerhouse structure of hydropower plants based on dynamic contact force method. Shock Vib. 2014, 2014, 859648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Tang, C. Microseismic Monitoring and Stability Analysis of Underground Powerhouse in Pumped Storage Power Station. In Microseismic Monitoring and Stability Analysis of Large Rock Mass Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 315–373. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, K.H.; Bai, Z.L.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Y.L.; Su, Y. Research on seepage control of Jurong pumped storage hydroelectric power station. Water 2022, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhou, Z.F.; Wang, H.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.G. A Comparative Study for Evaluating the Groundwater Inflow and Drainage Effect of Jinzhai Pumped Storage Power Station, China. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiratsuka, A.; Arai, T.; Yoshimura, T. Seawater pumped-storage power plant in Okinawa island, Japan. Eng. Geol. 1993, 35, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Fu, D.; Wu, H.; Liu, X. Seismic Performance of Beam-Column Systems in Pumped Storage Power Station Plants. J. China Rural Water Hydropower 2022, 6, 213–217 + 221. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Liu, J.J. Study on Vibration Response of Structures in Medium- and Low-Head Hydropower Station Plants. J. Northeast Hydroelectr. Power 2021, 39, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, J.J.; Wang, H.Z.; Wang, H.J. Study on vibration transmission among units in underground powerhouse of a hydropower station. Energies 2018, 11, 3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Ding, X.T. Structural Vibration Characteristics and Anti-Seismic Analysis of Huaian San Hydropower Station. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. Hydropower 2016, 36, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Yuan, C.Q.; Li, K.; Li, Y.J. Dynamic Response Analysis of Underground Powerhouse Structures Considering Coupling Effects of Hydraulic Impulse and Dynamic Loads. In Proceedings of the 2012 Second International Conference on Electric Technology and Civil Engineering, Wuhan, China, 18–20 May 2012; pp. 1011–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, B.S.; Guo, D.C.; Zheng, Q.F.; Xu, W.X. Study on Vibration under the Water Pulsation of the High Head Pumped Storage Power Plant. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Hydraulic and Civil Engineering & Smart Water Conservancy and Intelligent Disaster Reduction Forum (ICHCE & SWIDR), Nanjing, China, 6–8 November 2021; pp. 1695–1706. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Chen, J.; Yan, B. Vibration Response Analysis of Large Underground Powerhouses in Pumped Storage Power Stations. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2019, 50, 507–512. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.Q.; Xu, L.H.; Jia, X.; Wei, C.L. Research on Vibration Characteristics of Powerhouse Structure of Variable Speed Unit Section in Fengning Pumped Storage Power Station. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Environmental Science and Civil Engineering (ICESCE 2024), Khulna, Bangladesh, 7–9 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, G.Q.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.H. Numerical Simulation Study on Vibration Response of Large Underground Powerhouses in Pumped Storage Power Stations. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2024, 35, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.X.; Zeng, J.P.; Wu, B.; Gu, J.C. Study on the dynamic response of the powerhouse under the vibration load of the Hydropower Station. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Hydraulic and Civil Engineering & Smart Water Conservancy and Intelligent Disaster Reduction Forum (ICHCE & SWIDR), Nanjing, China, 6–8 November 2021; pp. 1667–1671. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.K.; Hu, X.W.; Xiao, P.X.; Hou, P.; Ma, Z.Y. Analysis of the Influence of Numerical Calculation Models on the Dynamic Characteristics of Underground Powerhouses. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2017, 13, 872–881. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.L.; Li, T.C.; Zhao, L.J.; Qin, H.; Zhu, S.S. Study on Seismic Resistance of Structural Systems in an Underground Powerhouse of a Pumped Storage Power Station. J. Hydropower Energy Sci. 2019, 37, 88–91+151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.J.; Guo, Y.H.; Wang, H.J.; Yang, X.L.; Lian, J.J. Research on Vibration Characteristics of an Underground Powerhouse of Large Pumped-Storage Power Station. Energies 2022, 15, 9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Fang, D.; Wan, X.B.; Li, L.Q. Dynamic Characteristics and Seismic Analysis of Baihetan Underground Powerhouse Structures. J. Hydropower Gener. 2019, 45, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.; Xu, Y.Q.; Hu, S.P.; Ren, Z.M.; Sheng, P.C. Study on the Scope of Dynamic Numerical Simulation Based on Viscoelastic Artificial Boundaries. J. Hydropower Energy Sci. 2018, 36, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhu, W.S.; Li, B.X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, D.F. The application of sensitivity analysis in hydropower based on grey theory. In Proceedings of the 2016 5th International Conference on Civil, Architectural and Hydraulic Engineering (ICCAHE 2016), Zhuhai, China, 30–31 July 2016; pp. 370–377. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.; Dong, Y.J. Construction Simulation and Sensitivity Analysis of Underground Caverns in Fault Region. In Proceedings of the China-Europe Conference on Geotechnical Engineering: Volume 1; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 415–418. [Google Scholar]

- Domagała, L.; Sieja, K. Effect of moisture condition of structural lightweight concretes on specified values of static and dynamic modulus of elasticity. Materials 2023, 16, 4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.M.; Al-Amawee, A.H. The ratio between static and dynamic modulusof elasticity in normal and high strength concrete. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2006, 10, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.Q.; Ma, Z.Y.; Yan, X.D.; Qi, J.X.; Du, X.J. Intelligent identification of underground powerhouse of pumped-storage power plant. Acta Mech. Sin. 2005, 21, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Condition | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Frame Foundation | Normal Operating | 752 | ||

| Half of the Poles Short-Circuited | 1050 | |||

| Two-Phase Short-Circuit | ||||

| Stator Foundation | Normal Operating | 374.3 | 94.4 | 472.1 |

| Half of the Poles Short-Circuited | 904.4 | 94.4 | 472.1 | |

| Two-Phase Short-Circuit | 1837.4 | 94.4 | 472.1 | |

| Lower Frame Foundation | Normal Operating | 69 | 137 | 1978 |

| Half of the Poles Short-Circuited | 437 | 873 | 1978 | |

| Two-Phase Short-Circuit |

| Location | Maximum Displacement/ | Max Principal Stress/MPa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | ||

| Generator Floor Slab | 4.35 | 4.30 | 11.65 | 0.057 |

| Busbar Floor Slab | 3.84 | 5.03 | 13.62 | 0.022 |

| Lower Frame Foundation | 16.00 | 17.13 | 112.40 | 0.424 |

| Stator Foundation | 10.35 | 10.87 | 87.38 | 0.273 |

| Air Duct | 10.59 | 11.48 | 19.50 | 0.359 |

| Conditions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone of Surrounding Rock | Without the surrounding rock | Surrounding rock within one unit-span distance | Surrounding rock within two unit-span distances | Surrounding rock within three unit-span distances |

| Conditions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surrounding Rock Elastic Modulus/GPa | 7 | 9 | 13 | 26 |

| Conditions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Elastic Modulus | E | 1.1 E | 1.2 E | 1.3 E |

| Conditions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damping Ratio | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.035 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, J.; Shen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Gan, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Y. Dynamic Characteristics and Parametric Sensitivity Analysis of Underground Powerhouse in Pumped Storage Power Stations. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11464. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111464

Gao J, Shen Z, Sun Y, Gan L, Xu L, Zhang H, Feng Y, Ni Y, Zhang Y, Xiang Y. Dynamic Characteristics and Parametric Sensitivity Analysis of Underground Powerhouse in Pumped Storage Power Stations. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11464. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111464

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Junhao, Zhenzhong Shen, Yiqing Sun, Lei Gan, Liqun Xu, Hongwei Zhang, Yaxin Feng, Yong Ni, Yanhe Zhang, and Yang Xiang. 2025. "Dynamic Characteristics and Parametric Sensitivity Analysis of Underground Powerhouse in Pumped Storage Power Stations" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11464. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111464

APA StyleGao, J., Shen, Z., Sun, Y., Gan, L., Xu, L., Zhang, H., Feng, Y., Ni, Y., Zhang, Y., & Xiang, Y. (2025). Dynamic Characteristics and Parametric Sensitivity Analysis of Underground Powerhouse in Pumped Storage Power Stations. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11464. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111464