Agricultural Water–Land Matching and Functional Zoning in Northern Shaanxi

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Matching Coefficient of Agricultural Water and Land Resource

2.3.2. Gini Coefficient

2.3.3. Bivariate Spatial Autocorrelation

2.3.4. Coordination Development Model

2.3.5. Functional Zoning Model of AWLRs

Zoning Index System and the K-means++-AHC Clustering Method

- (a)

- Arbitrarily choose an initial cluster center from X;

- (b)

- Calculate the square Euclidean distance [42] between and the cluster center;

- (c)

- Calculate the probability of data point , which will be taken as a new center:

- (d)

- Repeat step (b) and (c) until the taken k centers are together, which will be set as the initial centers ;

- (e)

- For each , set the cluster Ci to the set points in X that are closer to ci than they are to for all ;

- (f)

- For each , set to be the center of mass of all points in ,

- (g)

- Repeat step (d) and (e) until C no longer changes.

- (a)

- Calculate k clusters of the data points by K-means++;

- (b)

- Set the k clusters as the initial clusters, calculate the Euclidean distance between each pair of clusters and merge the two nearest clusters;

- (c)

- Repeat step (2) until the final Kp (kp ≤ k) clusters are obtained.

Silhouette Coefficient

2.3.6. The NRCA Index

3. Results

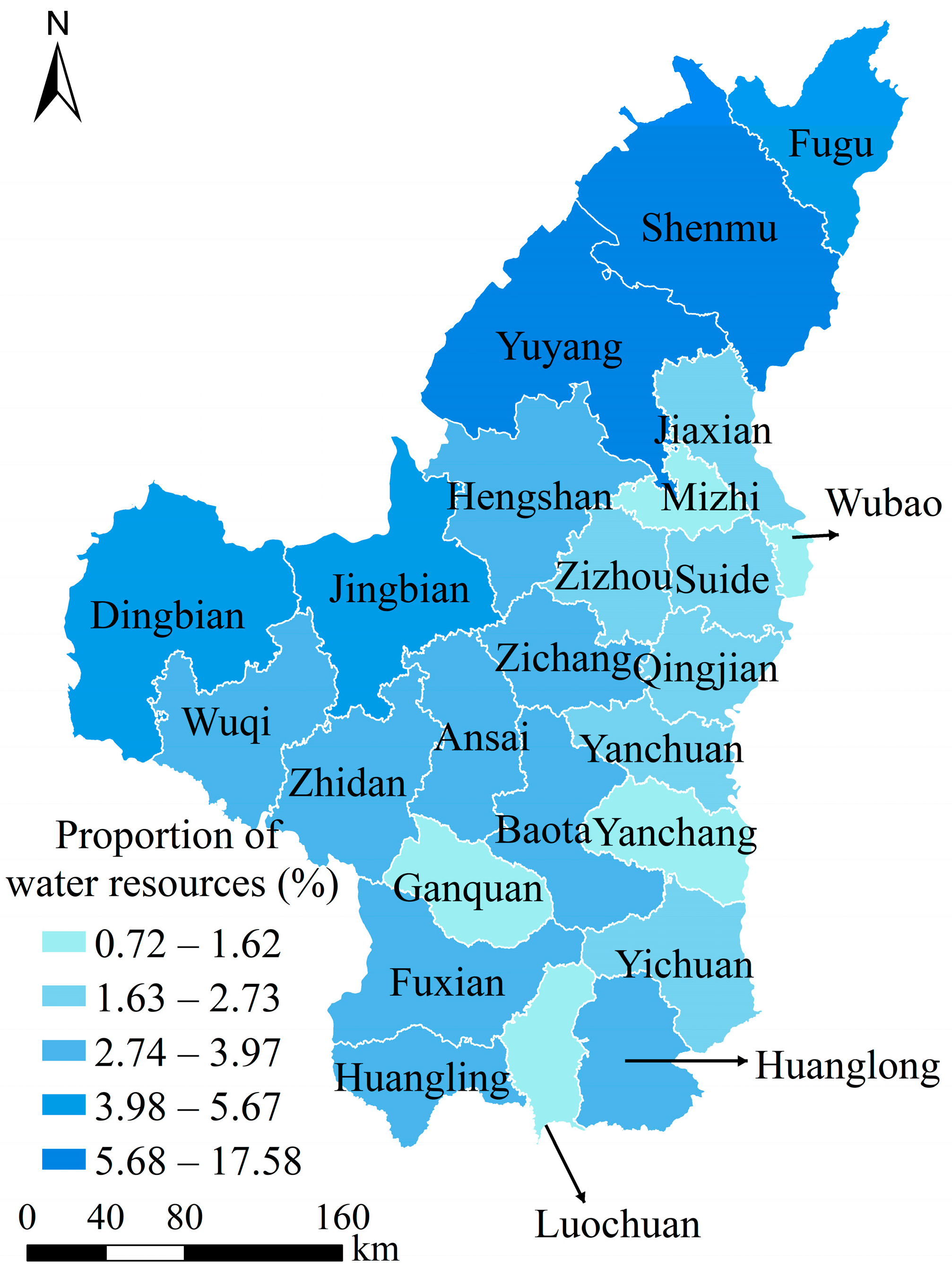

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Water Resources and Land Reclamation Rate

3.2. Matching Features of Agricultural Water and Land Resources

3.2.1. Spatial Matching Pattern of Agricultural Water and Land Resources

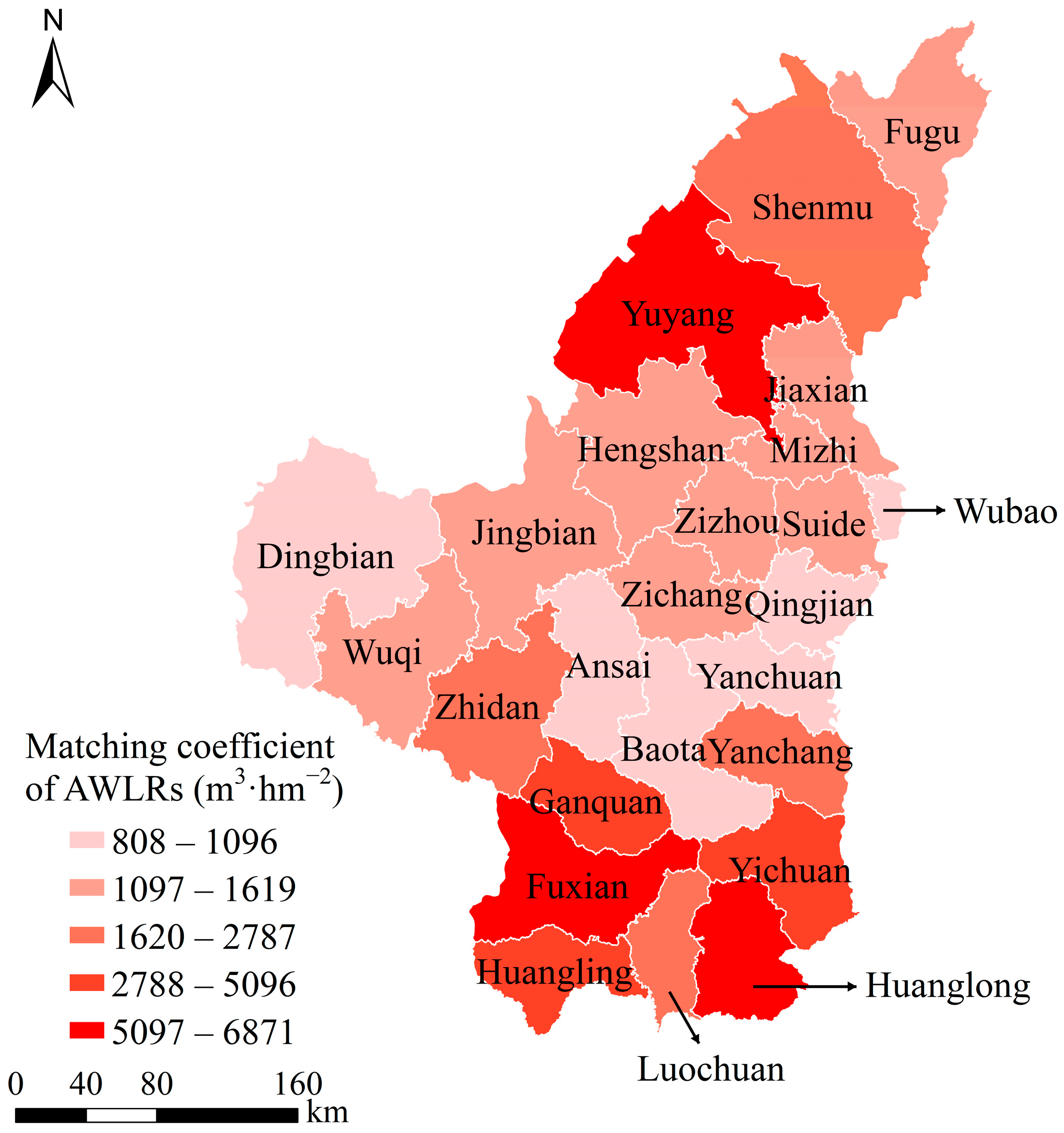

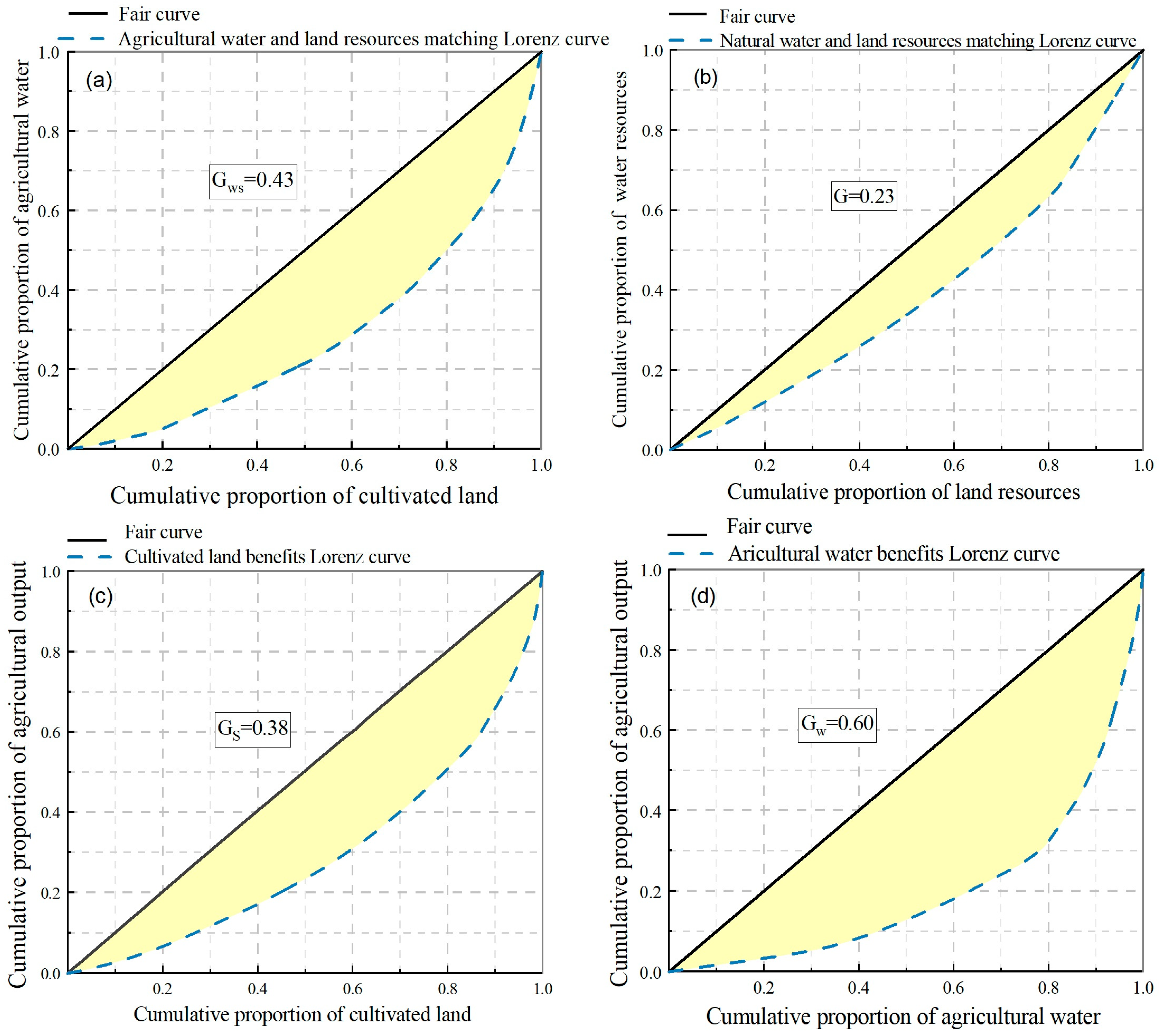

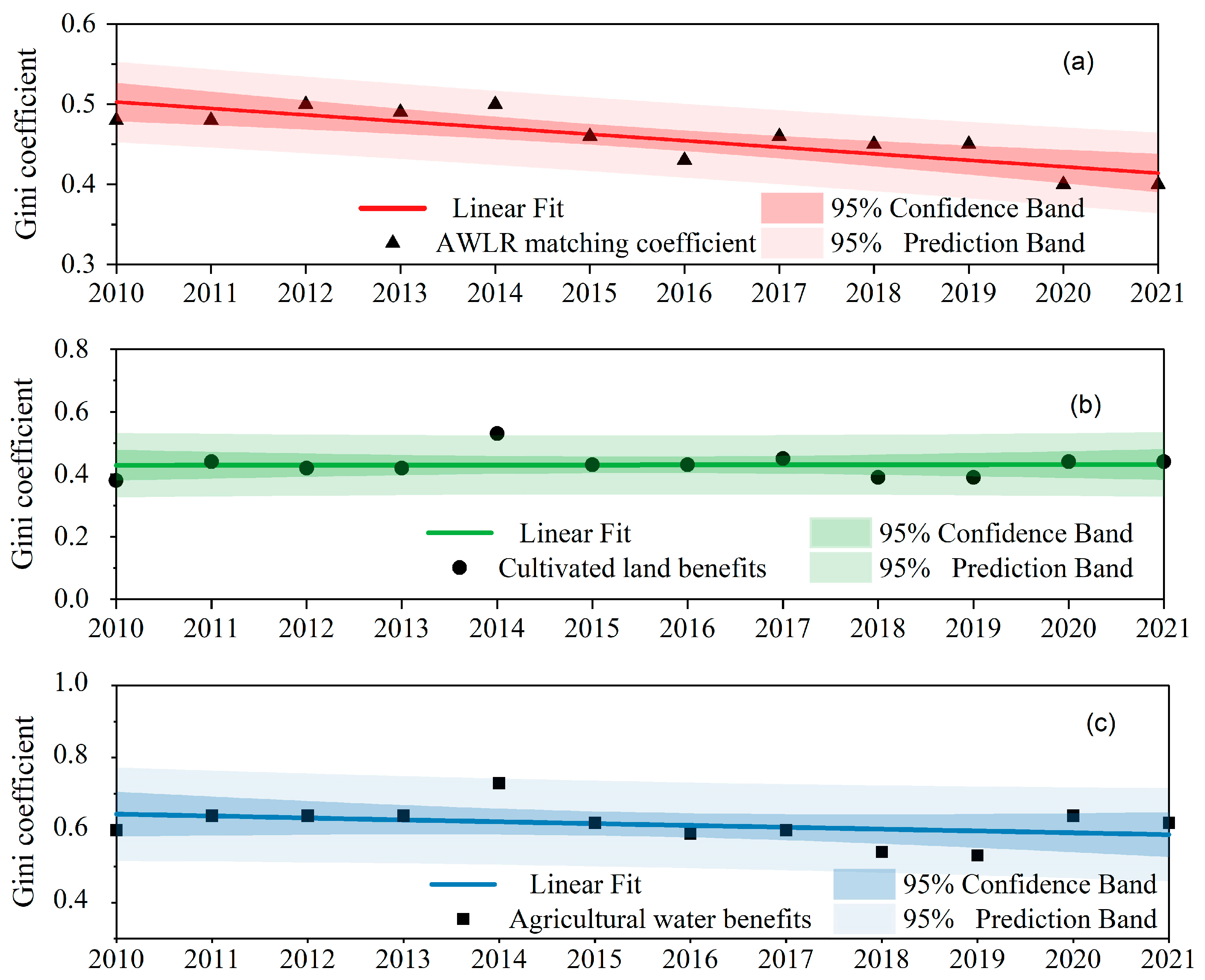

3.2.2. Gini Coefficient of Agricultural Water and Land Resources

3.3. Spatial Autocorrelation Between AWLR Matching and Agricultural Development Level

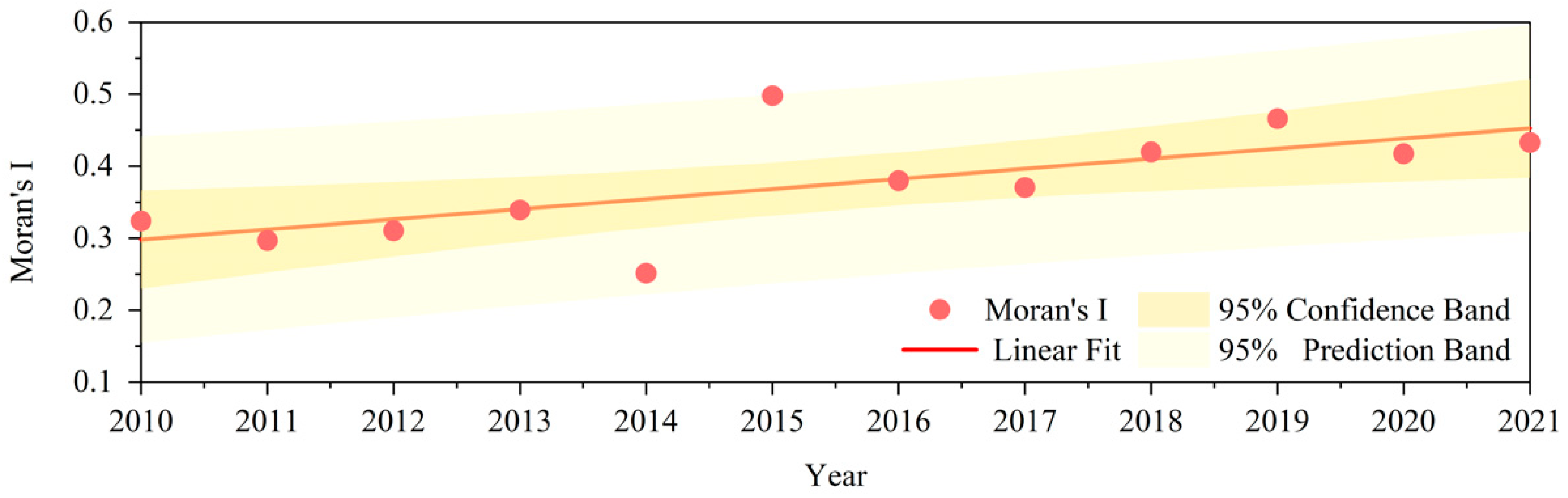

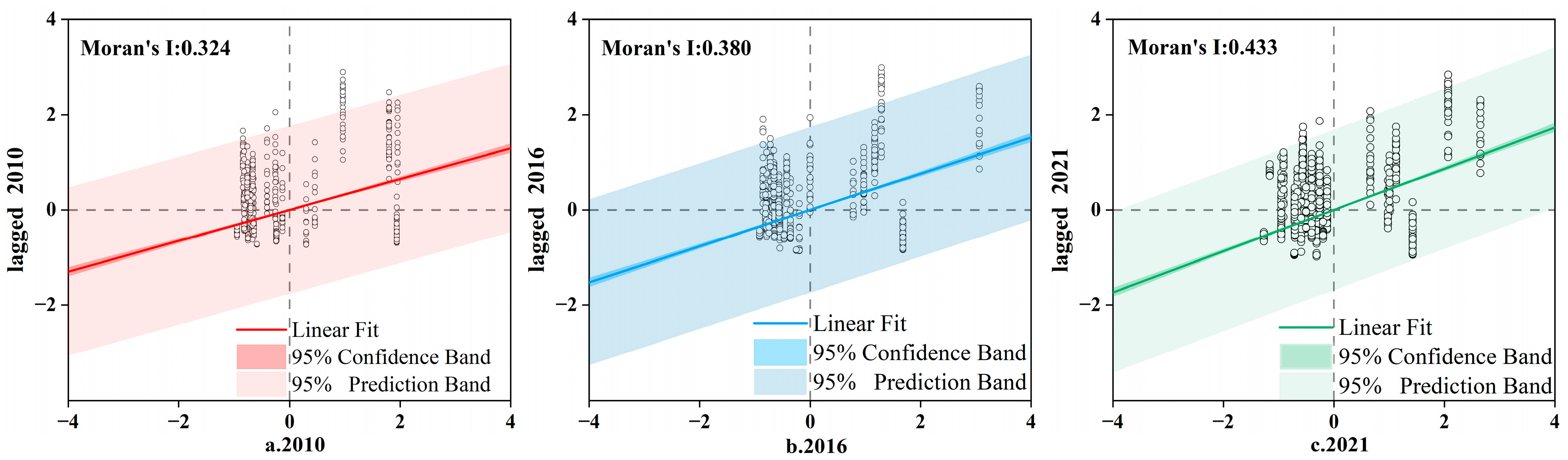

3.3.1. Analysis of Global Spatial Autocorrelation

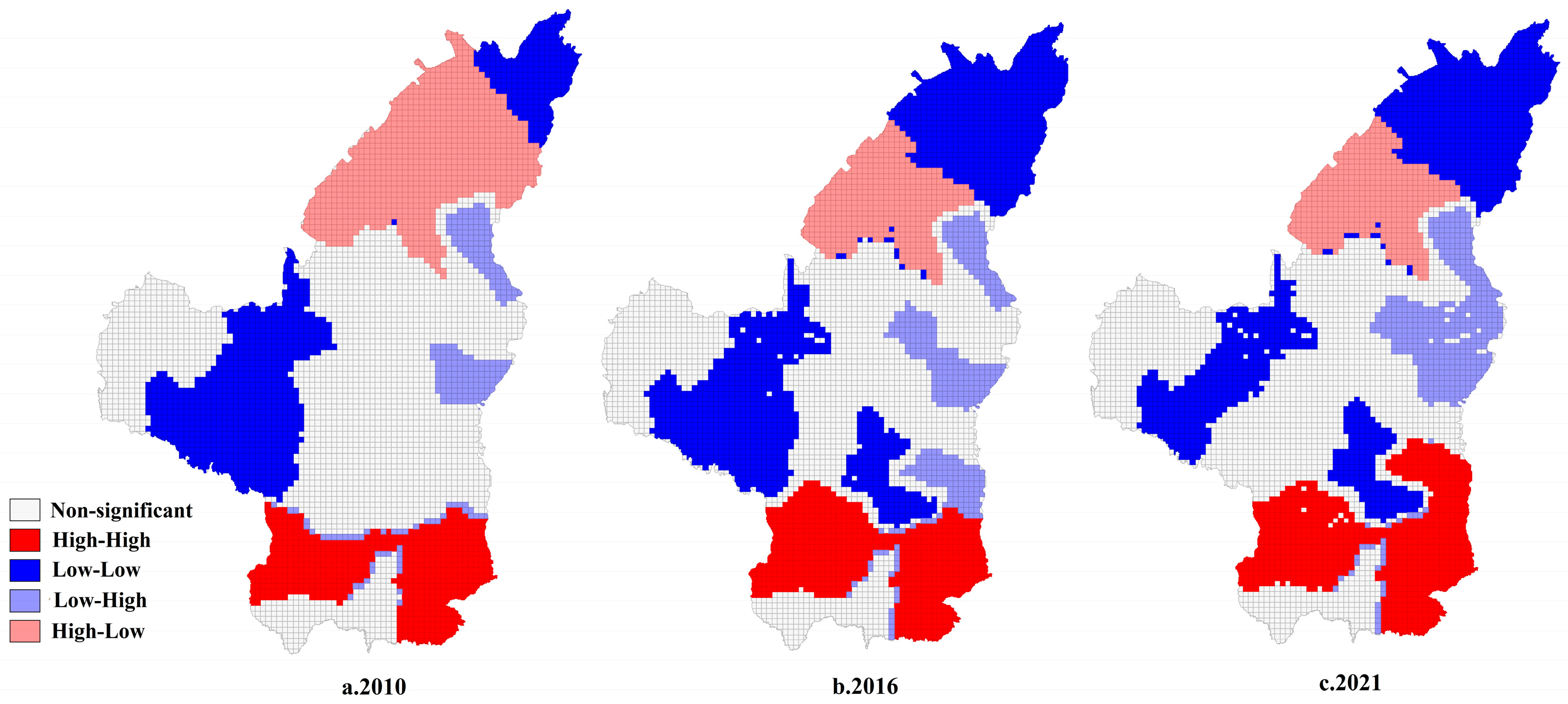

3.3.2. Analysis of Local Spatial Autocorrelation

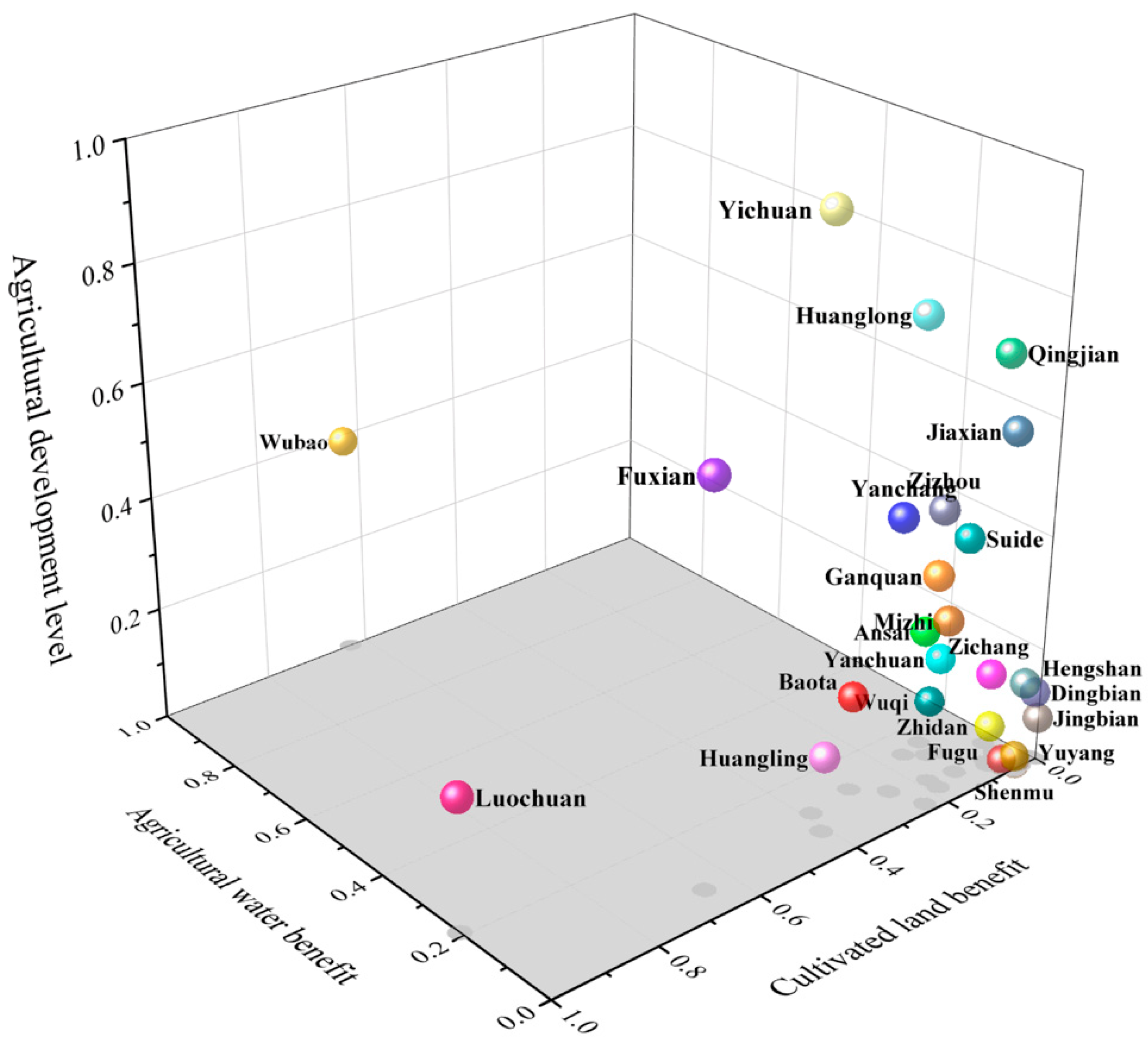

3.4. Analysis of the Coordinated Development Degree Model of Agricultural Development Level and the AWLR Benefit

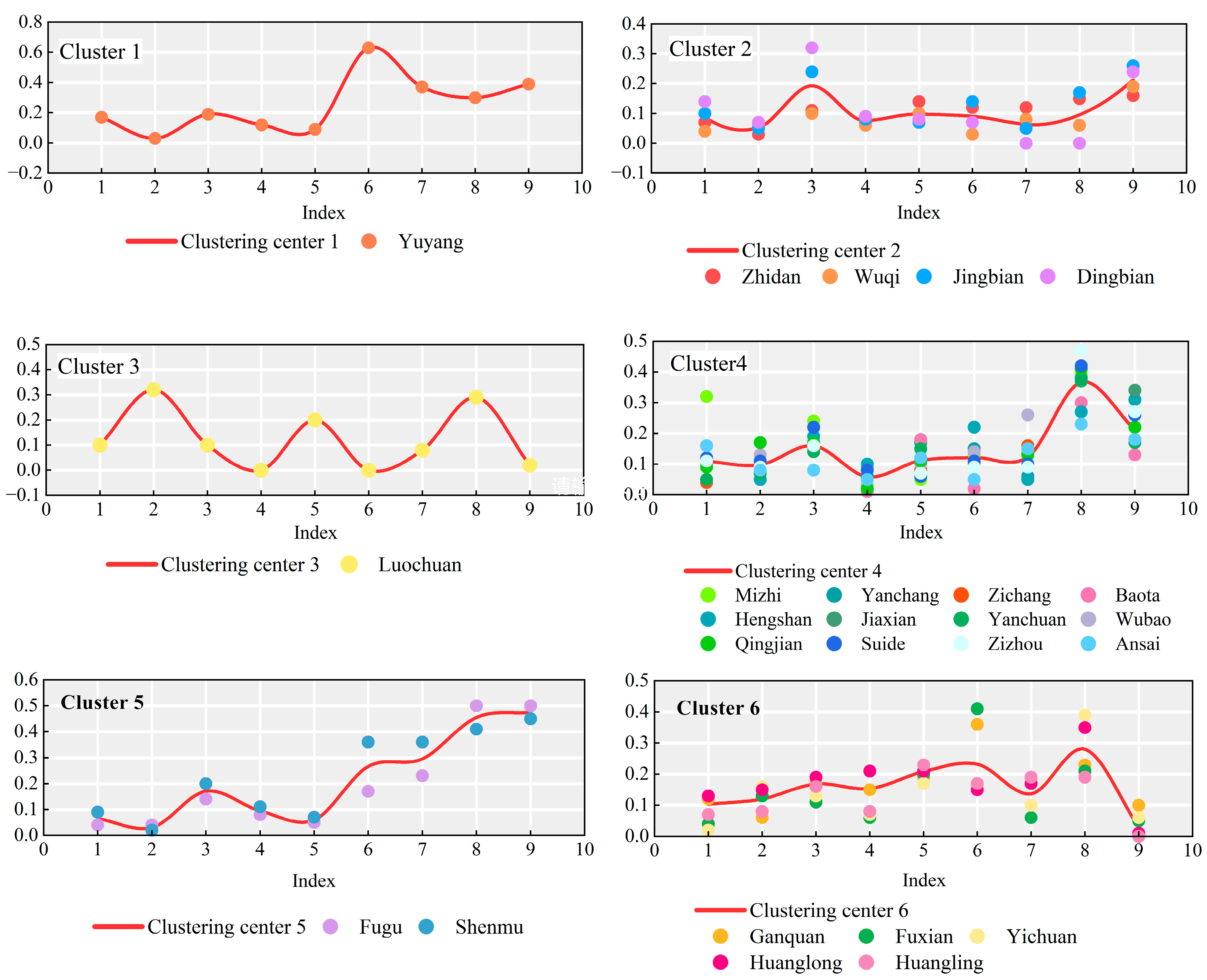

3.5. Functional Zoning Results of AWLRs

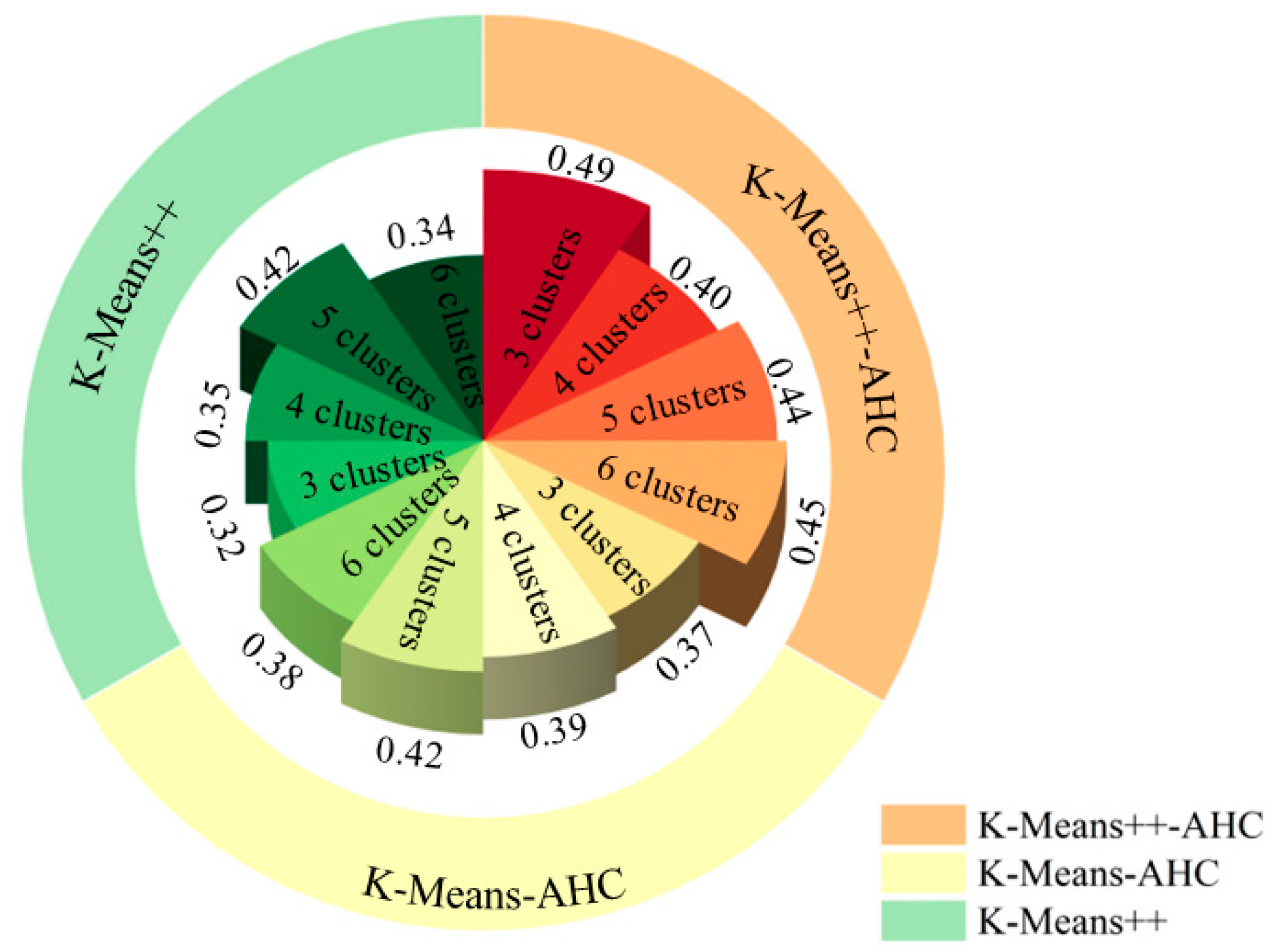

3.6. Comparison of Clustering Algorithms

4. Discussion

4.1. Coupling of Agricultural Water and Land Resources

4.2. Zoning Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WLRs | Water and Land Resources |

| AWLRs | Agricultural Water and Land Resources |

| NS | Northern Shaanxi |

| NRCA | Normalized Revealed Comparative Advantage |

| AHC | Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Liu, T.; Fang, Y.; Huang, F.; Wang, S.; Du, T.; Kang, S. Dynamic evaluation of the matching and utilization of generalized agricultural water and soil resources in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 39, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Boota, M.W.; Soomro, S.E.H.; Memon, A.A.; Soomro, S.A.; Ali, S.; Ali, M.; Khan, M.Z.; Hussain, A.; Bai, Y.; et al. Water strategies and management: Current paths to sustainable water use. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cao, X.; Liu, D.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Shang, R. Sustainable management of agricultural water and land resources under changing climate and socio-economic conditions: A multi-dimensional optimization approach. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 259, 107235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhong, K. Impact of water and land resources matching on agricultural sustainable economic growth: Empirical analysis with spatial spillover effects from Yellow River Basin, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chu, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y. Study on the spatiotemporal matching relationship of agricultural water and land resources in the Tarim River basin. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2024, 41, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Luo, B.; Guo, P.; Wu, H. Agricultural water and land resources management in Hetao Irrigation District based on the regulation of food production safety. J. China Agric. Univ. 2022, 27, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Zhao, X.; Pu, J.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Miao, P.; Wang, Q. Zoning regulation and development model for water and land resources in the Karst Mountainous Region of Southwest China. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R. Study on utilization efficiency and matching features of agricultural soil and water resources in inland river basin of Gansu Province based on Malmquist DEA. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2020, 22, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, X.; Singh, V.; Qi, X.; Zhang, L. Tradeoff for water resources allocation based on updated probabilistic assessment of matching degree between water demand and water availability. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 134923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, J.; Wang, J.; Qin, A.; Liu, Z.; Ning, D.; Zhao, B. Study on utilization potential of agricultural soil and water resources in Northwest Arid Area. J. Nat. Resour. 2017, 32, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Qi, X.; Li, P.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Analysis on spatial-temporal matching characteristics of agricultural water and soil resources in the Yellow River Basin. J. Irrig. Drain. 2021, 40, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Fu, W. Analysis of water and soil resources matching and agricultural economic growth in China from the perspective of water footprint: Taking the Yangtze River economic belt as an example. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2020, 41, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Ma, C.; Liu, B. Agricultural water and soil resources matching patterns and carrying capacity in Yan’an City. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Yao, H.; Yu, G.; Guan, W.; Xu, B.; She, D. Balance between water resources and soil resource in coastal regions of Jiangsu Province and its economic analysis. J. Irrig. Drain. 2023, 42, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Jia, S.; Lu, C.; Lv, A. Spatiotemporal matching between water resources and social economy: A case study in Zhangjiakou. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lei, G.; Zhang, H.; Lin, J. Spatiotemporal dynamics of land and water resources matching of cultivated land use based on micro scale in Naoli River Basin. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Analyses of supply-demand balance of agricultural products in China and its policy implication. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 1573–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, W.; Bao, A.; Lv, Y. Analysis of cultivated land change and water-land matching characteristics in Amu Darya River basin. Water Resour. Prot. 2021, 37, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Jin, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, R.; Cui, Y. Matching of agricultural water and soil resources in Jianghuai Hilly Area based on set pair analysis. Water Resour. Prot. 2023, 39, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Fang, F.; Wu, M.; Cao, X. Assessment of the regional agricultural water-land Nexus in China: A green-blue water perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, D.; Ma, J.; Zhu, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, J. Spatial and temporal matching characteristics of agricultural land and water resources in the Shule River Basin. Arid Land Geogr. 2023, 46, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.; Wu, P.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y. A framework of indicator system for zoning of agricultural water and land resources utilization: A case study of Bayan Nur, Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 40, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. A geogrid-based framework of agricultural zoning for planning and management of water & land resources: A case study of northwest arid region of China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 89, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Hao, H.; Ma, N.; Wu, F.; Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Wang, A. Division method and index system of key prevention regions of soil and water loss in Shaanxi Province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2017, 37, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bai, Z.; Dong, X. Land consolidation zoning in Shaanxi Province based on the supply and demand of ecosystem services. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liang, X.; Li, T.; Liu, D.; Xu, J. The spatiotemporal differentiation and functional regionalization of land use functions in the Loess Plateau in Northern Shaanxi Province. J. Northwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 52, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Regional differentiation and comprehensive regionalization scheme of modern agriculture in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Han, J. Characteristics of spatial distribution of cultivated land grade in Shaanxi Province. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 27, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Evaluation of agricultural water demand under future climate change scenarios in the Loess Plateau of Northern Shaanxi, China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 84, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liang, X.; Wei, Z.; Li, H. Spatial-temporal heterogeneity in the influence of landscape patterns on trade-offs/synergies among ecosystem services: A case study of the Loess Plateau of northern Shaanxi. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 6144–6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Han, S.; Li, F.; Li, W.; Zhao, M.; Li, H. Water resource carrying capacity and coordinated development in Yulin City of Shaanxi Province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 43, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W. Matching and carrying capacity of agricultural water and soil resources in Yulin City. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2017, 35, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Bai, S.; Shi, F.; Han, Z. Spatiotemporal changes of sloping farmland resources and its soil erosion effects in Yan’an City. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 29, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, B. Analysis of matching characteristics and scarcity of agricultural water and land resources in Shandong Province based on water footprint. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 4943–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Li, S. Extending Moran’s index for measuring spatiotemporal clustering of geographic events. Geogr. Anal. 2017, 49, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Spatio-temporal analysis of urbanization and land and water resources efficiency of oasis cities in Tarim River Basin. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Guo, Y.; Qian, H.; Xu, P. Comprehensive evaluation and coupling coordination of water resources carrying capacity in Guanzhong region. Ecol. Sci. 2025, 44, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, S.; Qu, F. Research on coupling coordination among cultivated land protection, construction land intensive use and urbanization. J. Nat. Resour. 2017, 32, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kong, W.; Ren, L.; Zhi, D.; Dai, B. Research on misuses and modification of coupling coordination degree model in China. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ji, G.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z. Environmental vulnerability assessment for mainland China based on entropy method. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, S.; Bilga, P.S.; Jatin; Singh, J.; Singh, S.; Scutaru, M.L.; Pruncu, C.I. Revealing the benefits of entropy weights method for multi-objective optimization in machining operations: A critical review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 1471–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Shen, S.; Zhou, A.; Chen, X. Prediction of geological characteristics from shield operational parameters by integrating grid search and K-fold cross validation into stacking classification algorithm. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 1292–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezelbash, R.; Maghsoudi, A.; Shamekhi, M.; Pradhan, B.; Daviran, M. Genetic algorithm to optimize the SVM and K-means algorithms for mapping of mineral prospectivity. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Ching, J.; Phoon, K.K. A spectral algorithm for quasi-regional geotechnical site clustering. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 161, 105624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagirov, A.M.; Aliguliyev, R.M.; Sultanova, N. Finding compact and well-separated clusters: Clustering using silhouette coefficients. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 135, 109144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Cai, J.; Leung, P. The normalized revealed comparative advantage index. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2009, 43, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Ma, R.; Li, X. Optimal clustering number determining algorithm by the new clustering method. J. Softw. 2021, 32, 3085–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Deng, W.; Tan, J.; Lin, L. Restriction of economic development in the Hengduan Mountains Area by land and water resources. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 1996–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xiong, Q.; Liang, P.; Xiao, Q. Potential risk to water resources under eco-restoration policy and global change in the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 094004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X. Geogrid-based framework of agricultural zoning for planning and management of water and land resources in Shaanxi Province. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 29, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistic | 2010 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| AWLR matching coefficient | 2029.02 m3/hm2 | 2390.67 m3/hm2 |

| Gini coefficient of AWLRs | 0.48 | 0.40 |

| Moran’s I | 0.32 | 0.43 |

| Zone | Agricultural Industrial | Economic Benefit | Land Resources | Water Resources | Natural Endowments | Matching Coefficient | Coordinated Development Degree | X | Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | −9.72 | −29.26 | −11.00 | 2.39 | −26.86 | 70.00 | −63.62 | −0.20 | 51.73 |

| II | 6.13 | −3.57 | 24.51 | 7.27 | 4.44 | 2.04 | −33.31 | −36.62 | 20.44 |

| III | 3.90 | 0.53 | −1.31 | −6.03 | −6.16 | −7.76 | −22.61 | 19.17 | 7.72 |

| IV | 10.16 | 15.17 | 14.68 | 16.98 | 8.59 | 37.59 | 77.15 | 23.92 | 17.14 |

| Dataset | Algorithm | Score of Evaluation Indexes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purity | ARI | AMI | NMI | ||

| K-means++ | 0.873 | 0.707 | 0.755 | 0.758 | |

| Iris | K-means-AHC | 0.862 | 0.687 | 0.739 | 0.742 |

| K-means++-AHC | 0.885 | 0.716 | 0.774 | 0.777 | |

| K-means++ | 0.891 | 0.711 | 0.692 | 0.695 | |

| Seeds | K-means-AHC | 0.857 | 0.640 | 0.673 | 0.672 |

| K-means++-AHC | 0.892 | 0.717 | 0.704 | 0.728 | |

| K-means++ | 0.362 | 0.389 | 0.521 | 0. 663 | |

| TEA | K-means-AHC | 0.463 | 0.436 | 0.635 | 0.730 |

| K-means++-AHC | 0.476 | 0.489 | 0.699 | 0.834 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Mu, Y. Agricultural Water–Land Matching and Functional Zoning in Northern Shaanxi. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111306

Li H, Li Y, Zhang H, Mu Y. Agricultural Water–Land Matching and Functional Zoning in Northern Shaanxi. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111306

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hui, Yaxin Li, Hongbo Zhang, and Yingqi Mu. 2025. "Agricultural Water–Land Matching and Functional Zoning in Northern Shaanxi" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111306

APA StyleLi, H., Li, Y., Zhang, H., & Mu, Y. (2025). Agricultural Water–Land Matching and Functional Zoning in Northern Shaanxi. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111306