1. Introduction

In many cases, large-scale photovoltaic (PV) power plants are installed far from load centers, and the power transmission lines are typically 161 kV underground cables with lengths ranging from several kilometers to several tens of kilometers. At night, when PV systems do not generate electricity, they may inject reactive power back into the grid, leading to voltage instability at the interconnection point. When the reactive power in the regional grid is insufficient, the voltage tends to decrease. Conversely, excess reactive power can increase system voltage. To ensure voltage stability in such areas, utility companies often require PV plant operators to refrain from supplying reactive power to a grid.

Various voltage regulation strategies for PVs have been studied, including constant power control, voltage regulation using energy storage systems (ESSs), and the installation of reactive power compensation devices. Reference [

1] proposed using an ESS to suppress voltage fluctuations in the grid; however, this approach requires additional ESS installations, thereby increasing the capital investment. In [

2], both static and dynamic reactive power compensation devices were employed to enhance the voltage stability in PV power plants; however, large-scale deployment entails higher investment costs. As analyzed in [

3], when the PV penetration level exceeds 30%, the voltage regulation capability of inverters can effectively replace static reactive power compensation devices.

Inverter-based systems inherently generate reactive power during active power production, and fulfilling the utility requirements for reactive power support during power generation is generally not an issue. However, when reactive power compensation is required during nongenerating periods, the economic dispatch of inverters within PV plants to maintain voltage stability is a critical challenge, particularly under cost constraints. In recent years, several studies have proposed the concept of using photovoltaic systems as STATCOMs, referred to as PV-STATCOMs, with the primary objective of enhancing the voltage stability [

4,

5].

Significant progress has been made in the study of nighttime reactive power compensation in photovoltaic (PV) systems. In a 2022 study by Lavi et al., the feasibility of using PV inverters to provide reactive power at night was explored to reduce grid operational costs. These results demonstrate the potential for economic and technical advantages [

6]. Additionally, Rezende et al. proposed a reactive power optimization strategy for power systems involving PV plants using a GA. Their approach effectively improved the voltage profiles and ensured compliance with the standard requirements [

7]. However, these studies primarily focused on theoretical analysis and simulation validation and lacked field-test data from large-scale PV plants. Further research is required to verify the practical effectiveness and reliability of these methods. As noted in [

8], the IEEE 1547-2018 standard [

9] requires distributed energy resources (DERs) to support voltage regulation, including the implementation of volt–var control. In this multitasking mode, inverters must adjust their reactive power output in response to voltage variations, which may increase the thermal stress on devices and ultimately affect their lifespan.

To address the issue of voltage instability potentially caused by a reactive power backfeed, this study employed a GA to optimize the placement and quantity of inverters. In addition to minimizing line losses, the proposed approach considers inverter thermal stress and aging risks. This design aims to enhance the operational efficiency of the inverter and extend the equipment lifespan.

The GA is an efficient technique for rapidly obtaining near-optimal solutions and is particularly suitable for identifying the optimal placement and number of multitask inverters in large-scale PV power plants. Following GA-based optimization, a DT framework was employed to perform hourly rolling updates, dynamically adjusting the number of active inverters to mitigate the residual reactive power caused by nighttime voltage fluctuations. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, DT-based simulations were conducted on a 120 MW large-scale photovoltaic power plant.

The primary objective of this study is to determine the optimal number and allocation of inverters for nighttime reactive power absorption and to demonstrate that integrating GA with DTs can effectively suppress residual reactive power and stabilize the grid voltage.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the genetic algorithm (GA) and its formulation for reactive power optimization.

Section 3 presents the digital twin (DT) framework and its implementation details.

Section 4 describes the simulation study, including the 120 MW PV plant and SCADA data. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

2. Genetic Algorithm

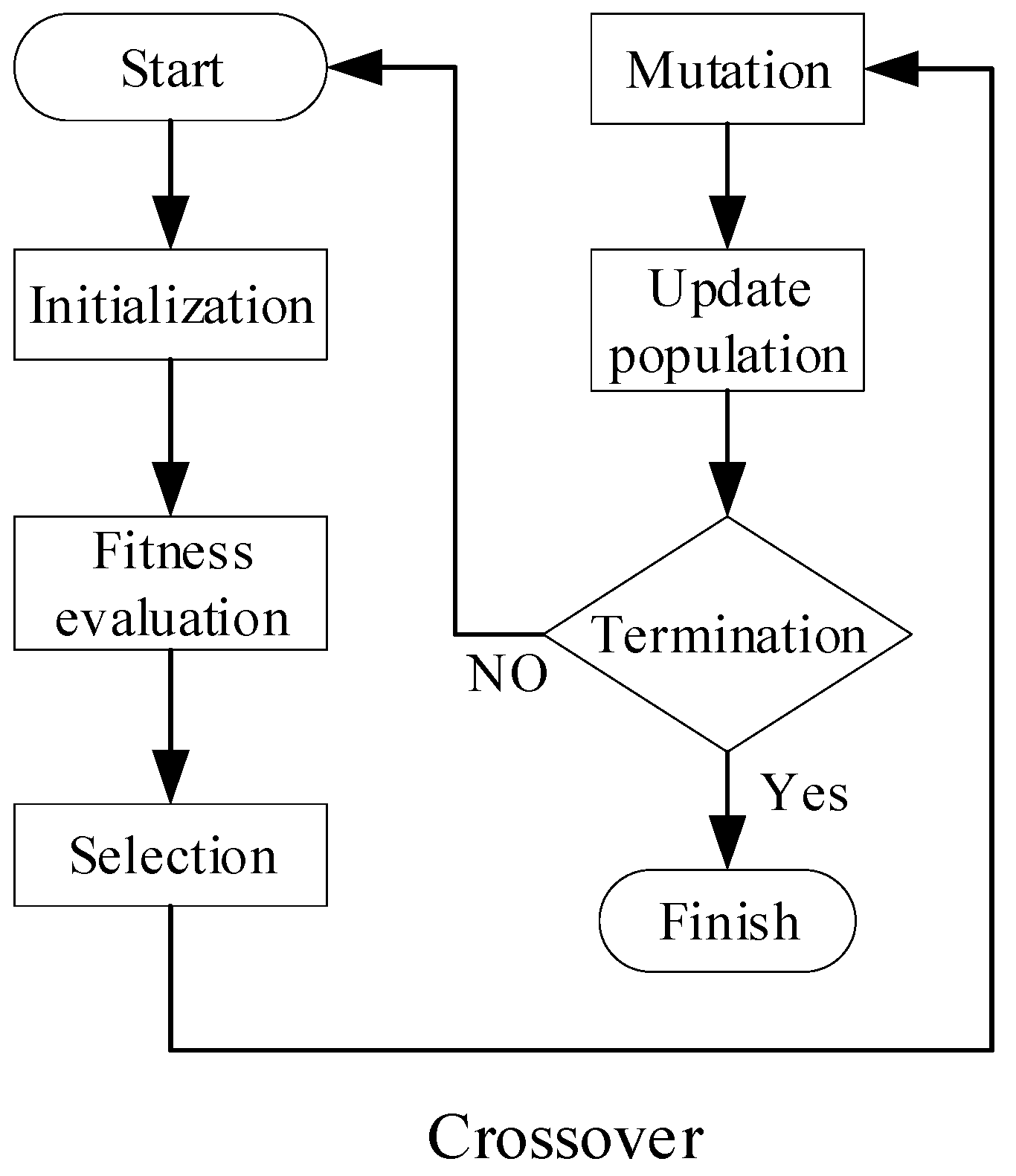

GA is a stochastic search algorithm inspired by the natural evolutionary processes observed in biological systems. It mimics mechanisms, such as selection, crossover, and mutation, which drive species evolution in nature. In each generation, the algorithm retains individuals with a higher fitness and applies genetic operators to generate a new population that gradually approaches the global optimum. Because the GA does not rely on gradient information and exhibits strong global search capabilities, it is particularly suitable for solving optimization problems that are nonlinear, multi-objective, or involve discrete variables. The fundamental steps of GA are outlined as follows:

Initialization: A set of candidate solutions known as the initial population is randomly generated. In this study, the population size was set at 1000.

Fitness Evaluation: Each candidate solution is evaluated based on the objective function and constraint conditions to determine its fitness value.

Selection: Based on the fitness values, a subset of high-performance candidate solutions was selected to serve as parents for the next generation.

Crossover: Selected parent solutions are combined to produce new candidate solutions. In this study, 90% of the new individuals in each generation were generated through crossover operations, whereas the remaining 10% were generated through mutations.

Mutation: Candidate solutions are randomly modified to increase the population diversity and prevent premature convergence.

Population Update: The current population is replaced with newly generated candidate solutions, and the process is repeated for multiple generations. In this study, the elitism size was set to 50, meaning that the top 50 individuals with the highest fitness were directly carried over to the next generation without undergoing crossover or mutation. This mechanism ensures that the best solutions obtained thus far are not lost in the subsequent generations.

Termination condition: The GA stops when a predefined termination condition is satisfied, such as reaching the maximum number of generations or finding a solution that satisfies the desired performance criterion.

In this study, the population size is set to 1000, and the crossover/mutation rates are configured as 0.9/0.1, respectively. These values were determined based on preliminary experiments that aimed to strike a balance between convergence speed and solution diversity. Additionally, a limited sensitivity analysis was conducted. The results indicate that when the population size falls below 500, inverter placement outcomes tend to be suboptimal. Moreover, increasing the mutation rate beyond 0.2 led to unstable convergence behavior during the evolutionary process. The complete execution procedure of the GA, including initialization, fitness evaluation, selection, crossover, mutation, population update, and termination, is illustrated in

Figure 1 which illustrates the overall workflow of the GA-based optimization.

The primary objective of this study is to determine the number of inverters to be dispatched and to identify which regions’ inverters should participate in reactive power absorption by solving an optimization problem. The objective function is defined as follows:

Constraints are defined as

where

: Reactive power supplied by underground cables.

: Reactive power absorbed by underground cables and distribution transformers during nighttime operation.

: Total reactive power absorbed by inverters during nighttime operation.

: The line losses resulting from the participation of multi-task inverters.

: Number of inverters participating in reactive power compensation.

,: are the weights

( in this study).

: is the amount of reactive power compensated for by inverter i.

In this study, the Constraint Tolerance for the GA optimization process was set to constraint Tolerance = 1 × 10−5, which represents a strict constraint setting. This ensures that all candidate solutions closely satisfy the equality condition of total reactive power absorption. Under these conditions, the minimized objective value obtained can be considered highly reliable, However, it was only used as a numerical convergence criterion during the simulation stage; in SCADA-driven practical DT operations, the tolerance is appropriately relaxed according to the measurement resolution to ensure real-time feasibility.

Figure 2 shows a single-line diagram of the actual photovoltaic (PV) power plant used in the GA implementation. The total installed capacity of the plant was approximately 120 MW, comprising 24 step-up substations and 1292 inverters, each rated at 100 kW. A SCADA system was installed across all critical nodes from the DC side to the AC side for real-time monitoring and data logging. The specifications of the distribution transformers, conductor types, and impedance data within the plant are detailed in

Table 1, which serves as the basis for the subsequent DT simulation and parameter modeling.

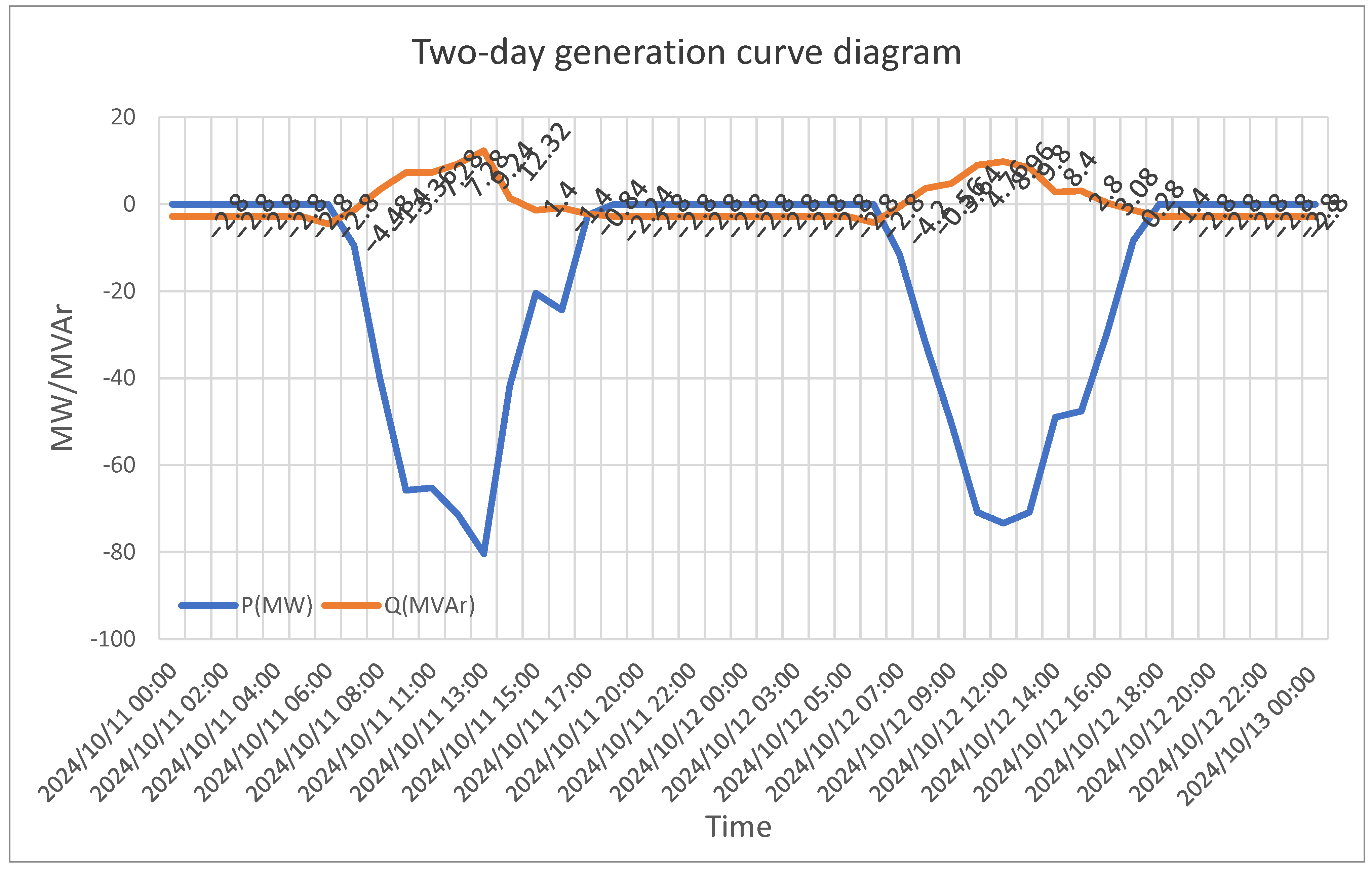

The PV plant under study was integrated into the power system in October 2024. However, at night, it injects approximately 2.8 MVAr of reactive power into the grid. The symbol “—” indicates power flowing into the grid.

Figure 3 shows the two-day active power generation and night-time reactive power backfeed.

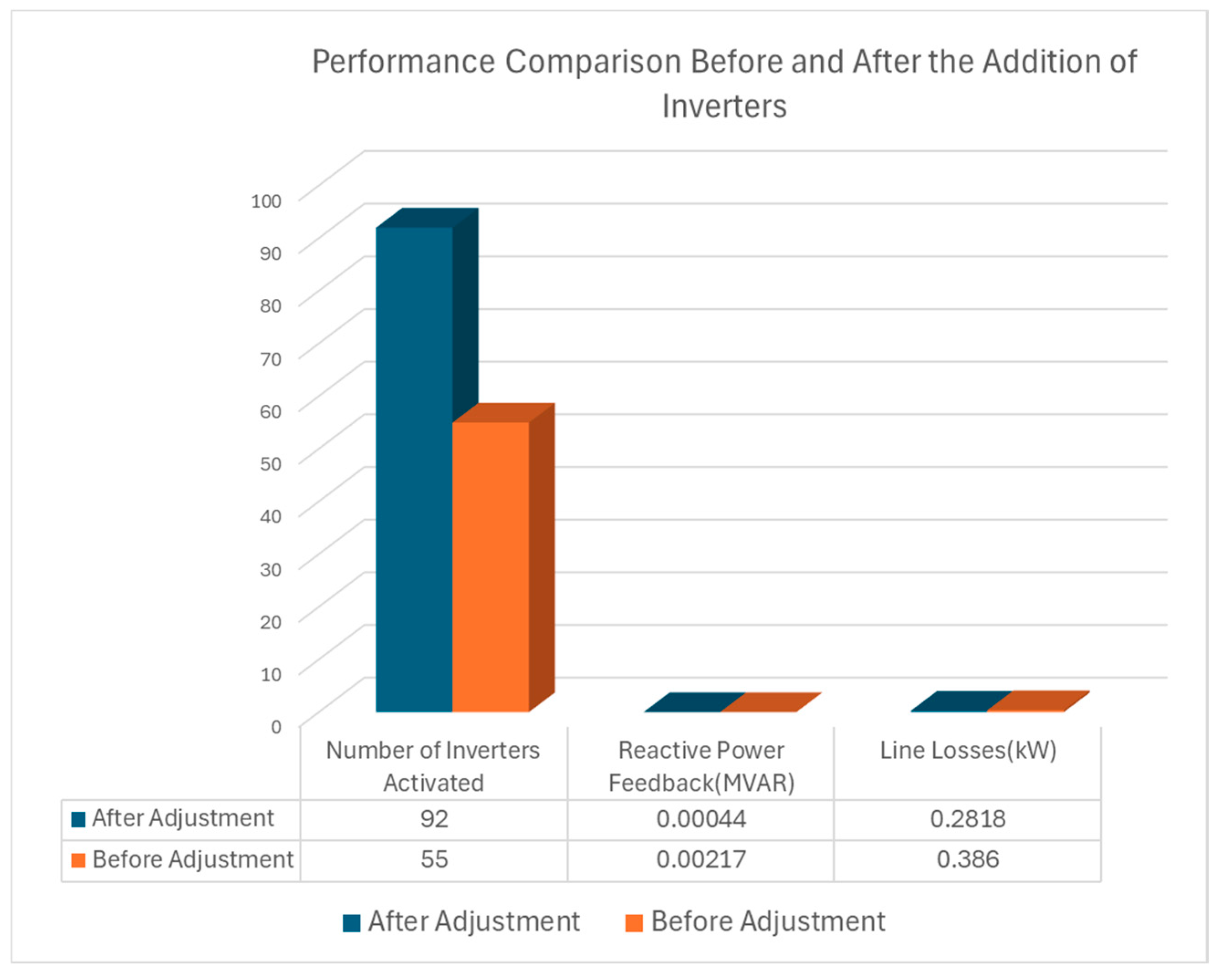

In the figure, the symbol indicates the direction of power flow into the grid. To address the issue of nighttime reactive power backfeed, the proposed GA-based method was applied to identify the optimal locations and select 55 inverters to operate in the multitask mode. Under normal system voltage conditions (1.0 pu), the reactive power backfeed was effectively reduced from 2.8 MVAr to 0.00217 MVAr, with an associated line loss of approximately 0.386 kW.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the improvements achieved by using the proposed strategy.

This study extends the GA framework established in [

10] by incorporating its optimization structure and objective formulation as the basis for the proposed DT-based real-time dispatch mechanism.

However, several multitask inverters may experience thermal stress during nighttime reactive power absorption. Rezvani et al. [

11] reported that multifunctional PV inverters injected with reactive power are subject to increased thermal loading, which can accelerate the lifetime degradation. To mitigate this issue, the reactive power output per inverter was reduced from 50 to 30 kVAr and GA-based optimization was executed again to determine a new set of optimal locations and inverter quantities. Consequently, the number of active inverters increases from 55 to 92, effectively alleviating the thermal degradation problem. Furthermore, the line losses were reduced from 0.386 kW to 0.2818 kW, representing an 18.6% reduction.

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the system performance after this adjustment.

Figure 7 shows the rapid convergence of the GA, with the optimization stabilizing within 5–10 generations. This occurs because as more inverters are dispatched, the residual reactive power decreases sharply, whereas line losses decrease initially and then level off, producing a clear trade-off with few local optima. In addition, grouping inverters by feeder length reduces the search space, allowing the GA to identify high-quality solutions at an early stage and to converge quickly.

3. Digital Twins (DTs)

The concept of DTs was initially introduced in the manufacturing domain with the aim of enhancing system operation and decision-making through cyber-physical integration and improved monitoring. DTs enable the integration of multiple simulation and analysis tools supported by continuous data exchange and feedback mechanisms to achieve dynamic system adjustments and predictive capabilities [

12]. DTs are considered to be a relatively new technology in power systems. With accurate modeling, a self-adaptive virtual replica of the physical system can be constructed to support the monitoring, testing, and control tasks. A key distinction between DT models and conventional mathematical models lies in the DT’s ability to autonomously adjust its parameters in real time, thereby reflecting the actual system behavior more effectively [

13].

Considering that the nighttime voltage in power systems may fluctuate owing to varying load conditions, residual reactive power may arise in the PV plant. A one-time static optimization of the inverter deployment cannot effectively respond to such voltage variations, which may lead to reverse reactive power issues, such as over-absorption or backfeeding. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce a self-adaptive Digital Twin (DT) model to enable the rolling control. In this context, the present study incorporates DT technology to achieve real-time inverter dispatch to mitigate the reactive power backfeed through dynamic hour-by-hour adjustments.

The Digital Twin framework includes the following simulation modules:

Reactive power demand variation (based on real-time data);

Point of Common Coupling (PCC) voltage estimation (considering reactive power–voltage sensitivity)

Residual reactive power calculation and assessment.

The Digital Twin (DT) dynamically evaluates the system status on an hourly basis by reassessing the reactive power backfeed and the deviations in the PCC voltage. Based on the updated system conditions, DT adjusts the activation states of the inverters according to the following decision logic:

If the voltage exceeds the specified threshold or the residual reactive power is positive (indicating a reverse flow to the grid), the number of active inverters is increased appropriately.

If the voltage falls below the specified threshold or the residual reactive power is negative (indicating overabsorption), a portion of the inverter is deactivated selectively.

The relationship between the reactive power variation and number of inverters is described as follows:

where

: Reactive power variation in the underground transmission cable caused by PCC voltage fluctuations.

: Reactive power generated by the cable during nighttime.

: Total reactive power in the reverse-fed system.

: Reactive power absorbed by each inverter.

: Inverter Count for Reactive Power Backfeed Mitigation.

The details of the DT-based inverter dispatch strategy in response to system voltage variations are illustrated in

Figure 9.

In this study, the SCADA architecture within a PV power plant was regarded as the data source for the DT system. It provides hourly measurements of critical parameters such as the PCC voltage, residual reactive power, and inverter activation status. Because nighttime voltage variations in utility-scale PV plants are typically gradual rather than abrupt, an hourly supervisory cadence is both practical and computationally efficient and is aligned with the hourly resolution of SCADA measurements. These real-time data are fed into the DT model, enabling dynamic updates of the reactive power demand and system parameters, such as the voltage and reactive power sensitivity, based on voltage fluctuations. Although the DT mechanism is not physically deployed on-site, the use of data-driven simulation allows for realistic emulation of the system behavior under various loading and voltage conditions. This approach effectively demonstrates the feasibility and potential of the DT model for rolling inverter dispatch and mitigation of the nighttime reactive power backfeed.

4. Simulation Study

This section presents simulations for two operating conditions: one where the system voltage falls below the nominal value of 1.0 pu and another where the voltage exceeds this nominal level.

4.1. Scenario with Undervoltage Conditions

In this scenario, it is assumed that between 18:00 and 00:00, the increased load demand causes the system voltage to drop to 0.95 pu. The relationship between the reactive power in the underground cable and the system voltage is expressed as follows:

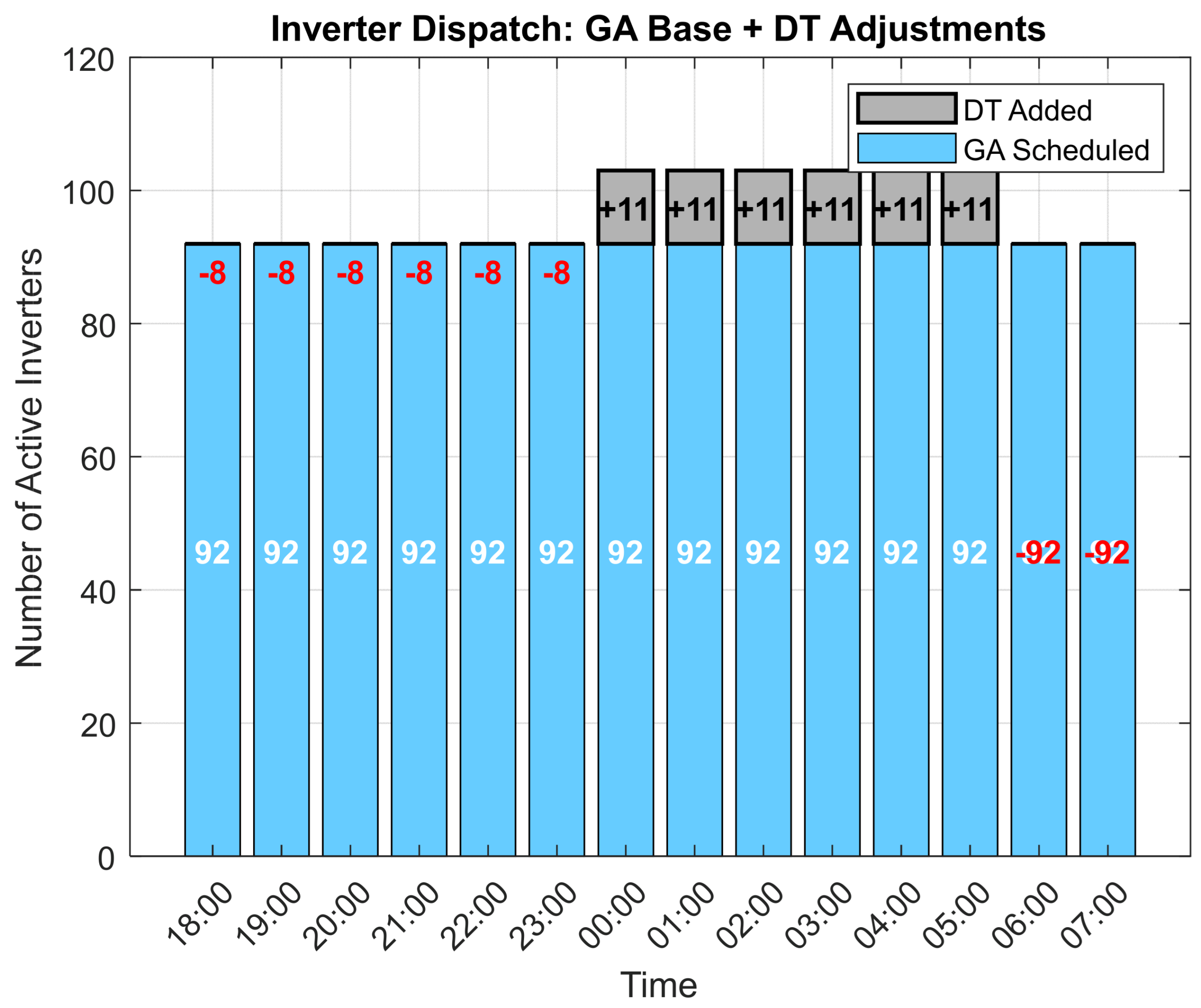

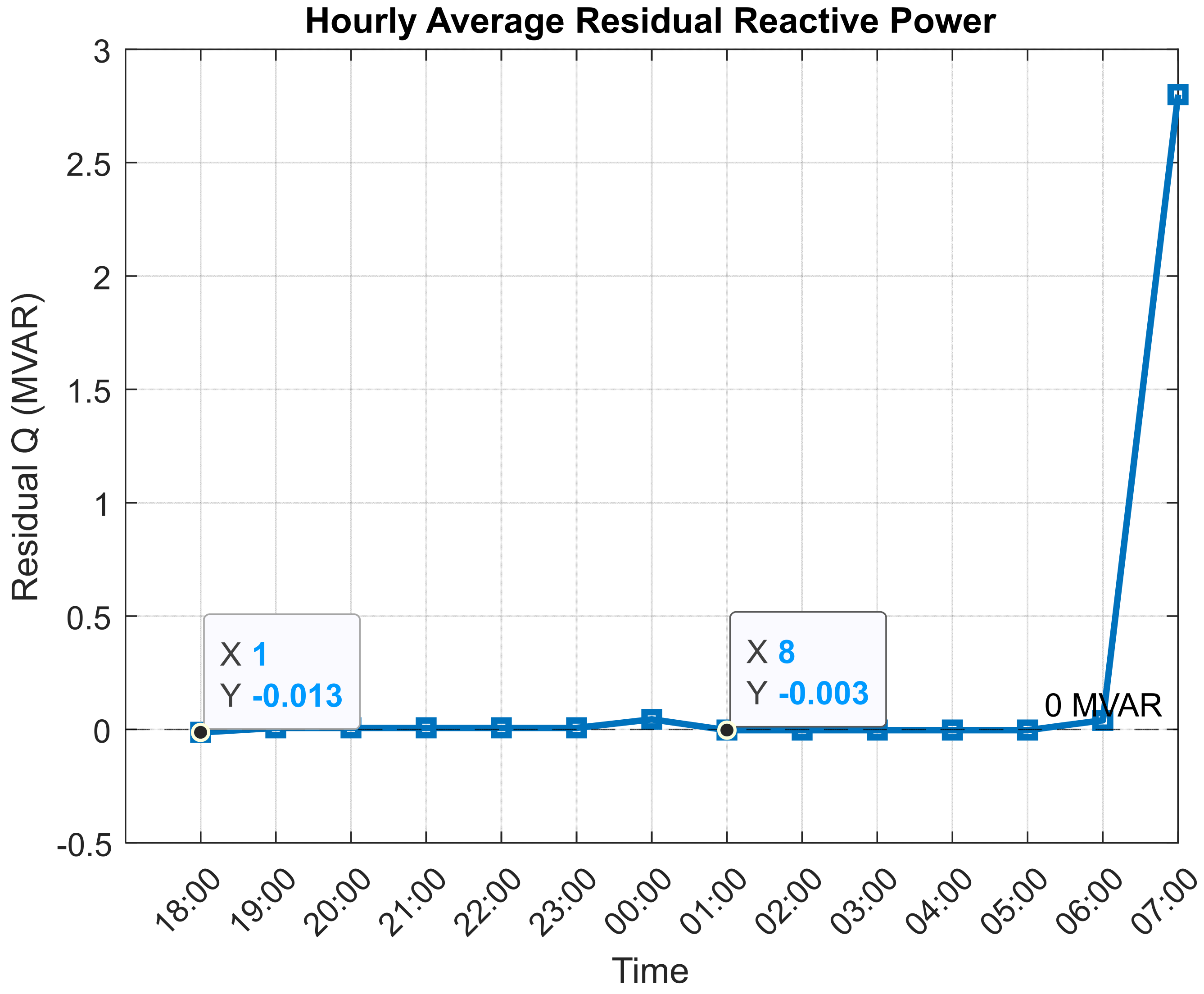

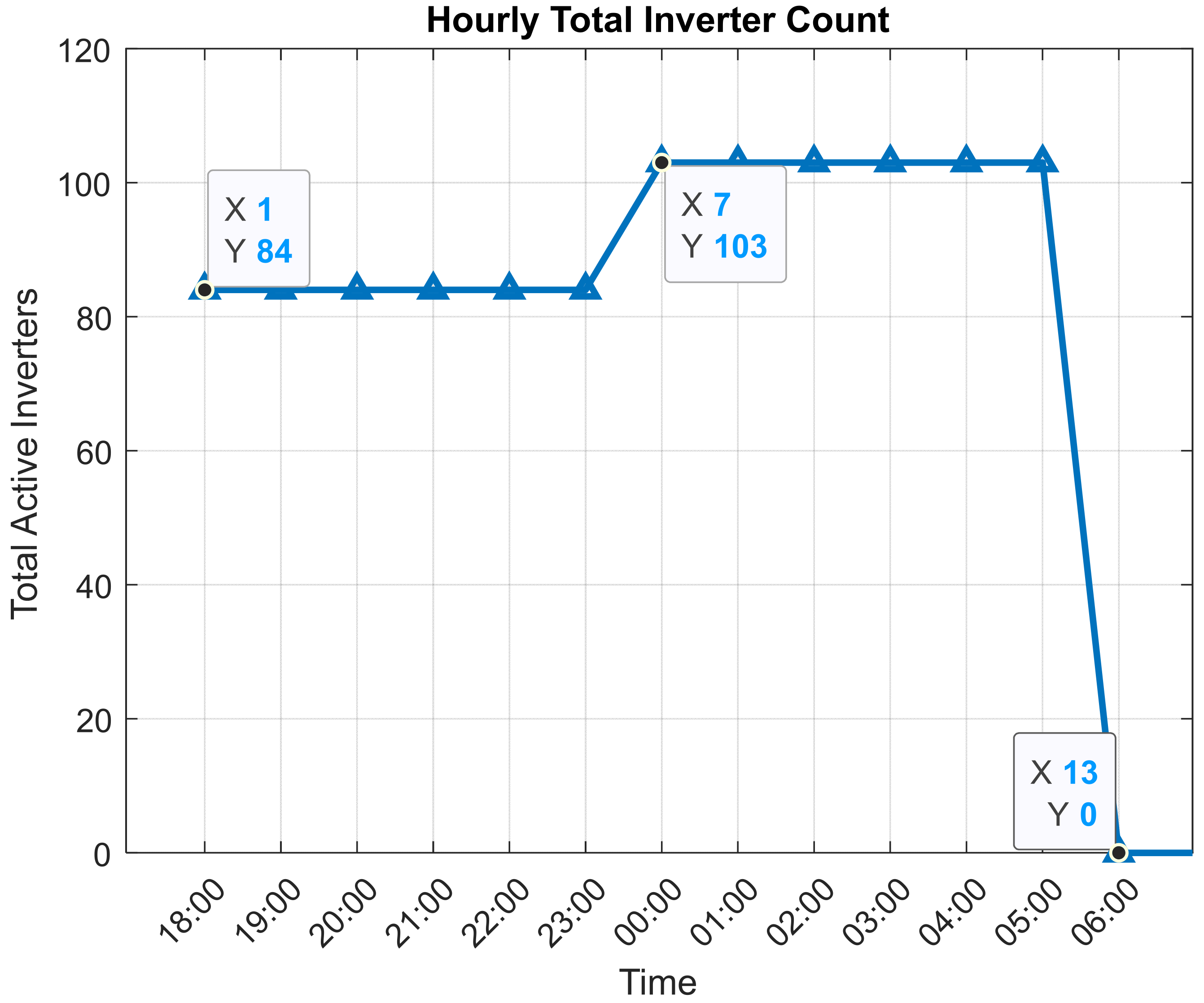

Owing to the voltage drop, the underground transmission cable generated approximately 2.527 MVAr of reactive power, which is lower than that 2.8 MVAr observed at a nominal voltage of 1.0 pu. Upon the detection of the reduced residual reactive power and voltage deviation, the DT model promptly deactivates the eight inverters to avoid overcompensation. The left half of

Figure 10 illustrates the undervoltage conditions that occurred at the PCC between 18:00 and 00:00. Correspondingly, the left half of

Figure 11 shows how the DT model deactivates the selected inverters during this period, to prevent excessive reactive power absorption.

The left half of

Figure 12 shows that after the real-time adjustment of the number of active inverters using the DT model, the residual reactive power was effectively reduced to 0.013 MVAr.

The simulation results conducted in MATLAB (2024b Update 5(24.2.0.2863752) 64-bit(win64)) demonstrated that DT exhibits strong self-adaptive capabilities. It can accurately detect variations in the residual reactive power caused by system voltage fluctuations and promptly execute inverter dispatch decisions. This highlights the high sensitivity and adaptability of the DT model, which enables real-time correction of the reactive power distribution and voltage deviations during multitask inverter operation, thereby achieving closed-loop control objectives.

4.2. Scenario Under Overvoltage Conditions

In this scenario, it is assumed that between 00:00 and 06:00, a decrease in the load demand causes the system voltage to rise to 1.05 pu. The right half of

Figure 10 shows the overvoltage condition at the PCC during this period, which returned to normal daytime conditions after 06:00. The right half of

Figure 11 indicates that the DT model detects an increase in the reactive power backfeed to 3.087 MVAr owing to the voltage rise. To prevent insufficient reactive power compensation, the DT dispatches 11 additional inverters in addition to the existing 92 inverters, resulting in a total of 103 activated inverters. After 06:00, the DT fully deactivates the multi-task inverter mode. The right half of

Figure 12 shows that under the overvoltage condition, the DT successfully controls the reactive power backfeed to as low as 0.003 MVAr, demonstrating its capability for real-time reactive power regulation.

Figure 13 illustrates the inverter dispatch curve governed by the DT model, which clearly shows the variation in the number of active inverters during the voltage fluctuation period between 18:00 and 06:00. After 06:00, the system exits the multitask inverter operation mode and returns to normal daytime generation, marking the end of the nighttime real-time reactive power compensation using the proposed hybrid GA–DT strategy for large-scale PV plants.

5. Discussion

This chapter provides a comprehensive discussion of the proposed GA–DT hybrid strategy for nighttime operation of large-scale photovoltaic (PV) power plants, focusing on its technical implications, scalability, and comparison with existing research. Furthermore, it extends the discussion to recent advancements and emerging trends in the application of Digital Twin (DT) technology within PV systems.

5.1. Comparison with Existing DT-Based PV Applications

In recent years, Digital Twin (DT) technology has gradually expanded from the manufacturing sector to renewable energy systems. Gui et al. [

14] proposed an Automatic Voltage Regulation (AVR) framework for PV inverters in low-voltage distribution networks, utilizing a DT model to achieve coordinated control among multiple inverters, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of virtual–physical correspondence in validating voltage support strategies. Similarly, Ebrahimi et al. [

15] developed an adaptive Volt–VAR control platform based on a DT framework, which enables real-time reactive power adjustment and enhanced voltage quality.

Compared with these studies, the present research extends the role of DT from a mere simulation tool to a rolling decision-making engine by integrating GA optimization results for hourly autonomous dispatch. This closed-loop mechanism, comprising optimization, simulation, and feedback, continuously updates the number of activated inverters using real SCADA data, thereby demonstrating the immediacy and practical feasibility of DT-based voltage-stability management during nighttime operation.

5.2. Role of Digital Twin in Real-Time Dispatch

Compared to traditional static optimization methods, DT can dynamically adjust the number of active inverters in real time under overvoltage (1.05 pu) or undervoltage (0.95 pu) conditions. In this study, the DT re-evaluates the PCC voltage and residual reactive power every hour, determining the inverter activation or deactivation according to Equations (5) and (6). Consequently, the residual reactive power was effectively maintained within the range 0.013–0.003 MVAr. Compared with the Volt/Var coordinated control results of Poore et al. [

16], which utilized a DT-based simulation of high-PV-penetration distribution systems, this study further implemented a rolling self-adjusting dispatch mechanism, achieving a higher temporal resolution and stronger practical applicability under the same conceptual framework.

5.3. Scalability and AIoT Integration Potential

Several recent review studies (e.g., Angelova et al. [

17]) have indicated that the integration of Digital Twin (DT) and Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) technologies represents a major future direction for the smart operation and maintenance of photovoltaic (PV) power plants. This convergence enables the integration of IoT sensing, cloud-based analytics, and edge control to form a comprehensive digital-monitoring ecosystem. The proposed GA–DT framework in this study aligns with this trend, where the Genetic Algorithm (GA) functions as a global optimizer, determining the optimal inverter dispatch and control parameters, while the DT serves as a real-time digital twin simulator that continuously mirrors and updates plant behavior. They established a closed-loop control process for data acquisition, model updating, and feedback regulation in the AIoT environment.

Furthermore, by incorporating LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) or AI Transformer predictive neural network models, a predictive nighttime reactive-power dispatch scheme can be realized. LSTM models effectively capture long-term temporal dependencies, whereas AI Transformer networks leverage an attention mechanism to learn the complex global correlations among multivariate features. When combined with the GA–DT architecture, these models can endow the system with proactive decision-making capabilities, allowing inverter scheduling to be adjusted before voltage deviations or load variations occur, thereby enhancing the intelligence and real-time adaptability of nighttime voltage-stability management.

6. Conclusions

A hybrid strategy that integrates a Genetic Algorithm (GA) with Digital Twin (DT) technology to address nighttime voltage fluctuations caused by reactive power backfeeds from underground cables in large-scale (PV) power plants was proposed in this paper. The proposed method reduces the residual reactive power, dynamically adjusts the inverter dispatch under overvoltage and undervoltage scenarios, and enhances overall voltage stability. By optimizing the reconfiguration of multi-task inverters through the GA, the reactive power backfeed was reduced from 2.8 MVAr to 0.00217 MVAr. In addition, the inverter thermal stress was alleviated, and the line losses were minimized to 0.2818 kW.

The introduction of Digital Twin (DT) technology during nighttime operations further enhances the adaptability of the system. Simulations showed that the DT can detect voltage deviations and residual reactive power fluctuations in real time. Under overvoltage conditions, the DT automatically activates 11 additional inverters to maintain reactive power balance and stabilize the residual reactive power within a minimal range. Conversely, under undervoltage conditions, it deactivates eight inverters to prevent overcompensation, demonstrating a high sensitivity and self-adaptive control capability. Although Teng et al. [

18] focused on SVG-based DT applications, the GA–DT hybrid strategy proposed in this study extends the concept to multitask inverter dispatch in large-scale PV power plants, with a particular emphasis on addressing nighttime overvoltage and undervoltage issues through effective reactive power management. Additionally, the GA–DT strategy proposed in this study, supported by full-hour simulations and SCADA-based field measurements, demonstrated strong adaptability and high feasibility, thereby indicating its potential as an AIoT-enabled solution for scalable applications in intelligent PV power plants.

In contrast to a previous study [

10] that focused solely on optimizing the reactive power equipment investment using a GA, the present study integrated a DT-based real-time dispatch mechanism to dynamically adjust the inverter operation under night-time overvoltage scenarios. The proposed approach was further supported by full-hour simulations and field-measured data. Overall, the GA–DT hybrid strategy effectively reduces line losses and inverter thermal risks while enabling real-time reactive power compensation and closed-loop voltage control in response to nighttime grid dynamics. This method exhibits strong practical scalability and deployment potential, contributing to reliable and cost-effective operation and maintenance of future intelligent PV power plants.

Future work could explore integrating Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)-based voltage forecasting models into the DT framework to proactively schedule inverter groups in anticipation of the grid fluctuations.