1. Introduction

The location under study is the city of Zrenjanin, Serbia, which has been facing water supply issues for decades, particularly regarding specific parameters in raw water, primarily high levels of color, organic matter, and arsenic. Numerous tests have been conducted over the past 20–30 years, but none have resulted in an adequate solution to this problem, especially concerning the arsenic content in the water. Zrenjanin is supplied with water from two linear systems of drilled tubular wells, located to the north of the city. The first well line, closer to the city, was established between 1965 and 1970 with 8 drilled wells, each approximately 126 m deep. The wells draw groundwater from the primary aquifer complex at depths of 50–77 m and 90–122 m. The second well line, situated about 1300 m north of the first line, began development in 1978 with the construction of four drilled wells, each approximately 137 m deep. Currently, 34 wells are active at the source, from which the extracted groundwater is sent to the Water Treatment Plant (WTP) [

1].

The city of Zrenjanin has faced a ban on the use of drinking water from the municipal supply for more than three decades due to the presence of elevated concentrations of arsenic, natural organic matter, color, sodium, and other critical parameters. Despite numerous initiatives and technical interventions over the years, a sustainable and reliable solution to this highly challenging problem has not yet been achieved. Various approaches have been proposed and tested by domestic and international experts, reflecting the complexity of treating groundwater of such unique composition. This long-standing issue highlights the need for innovative treatment strategies that go beyond conventional approaches and take into account the specific characteristics of raw water quality.

After more than three decades of restrictions on drinking water use, the first groundwater treatment plant, with a capacity of 200 L/s, was finally constructed in 2018, marking a significant step toward addressing this long-standing challenge. The treatment plant is composed of several process units, beginning with chemical pretreatment, which includes oxidation, coagulation, flocculation, and pH adjustment. This is followed by ultrafiltration (UF), reverse osmosis (RO) applied to approximately 50% of the incoming flow, ion exchange (IE) for the UF permeate, disinfection of the treated water using chlorine, and sludge management. The first unit in the treatment process is the pretreatment facility (aeration basin), where raw well water is oxidized using sodium hypochlorite, which oxidizes iron, arsenic, and manganese present in the groundwater and removes ammonia through oxidation at the breakthrough point. The plant with this groundwater treatment concept was unable to achieve continuous production of drinking water in accordance with the Regulation on the Hygienic Safety of Drinking Water [

2]. Subsequent analyses revealed that the plant lacked an adequate pretreatment process for raw water, which resulted in insufficient removal of arsenic, color, and organic matter. This led to excessive strain on the membrane filtration system, causing operational difficulties, more frequent membrane cleaning, as well as methane gas intrusion into the system.

Subsequently, the Water Treatment Plant (WTP) was taken over by a new investor “Metito Utility Limited” (hereinafter referred to as the Metito) who, in collaboration with the Water Institute Jaroslav Cerni (hereinafter referred to as the JCWI) contributed to the development of a suitable pre-treatment solution tailored to the specific characteristics of this case. The testing process for pre-treatment was initially carried out under controlled laboratory conditions and subsequently validated through on-site trials at the plant.

Pretreatment is a crucial step in water treatment processes aimed at reducing contaminants such as color, arsenic, and organic matter before further purification stages. Different pretreatment technologies are selected based on the specific pollutants and their concentrations, water matrix, and treatment goals.

Color in water often originates from natural organic matter (NOM), industrial dyes, or humic substances. Common pretreatment methods include coagulation-flocculation with addition of coagulants (e.g., aluminum sulfate, ferric chloride) causes NOM and color-causing compounds to aggregate and settle, activated Carbon Adsorption: Granular or powdered activated carbon effectively adsorbs colored organic molecules and oxidation processes such as chemical oxidants like chlorine, ozone, or advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) degrade colored compounds [

3]. Arsenic removal is critical due to its toxicity and prevalence in groundwater. Pretreatment methods include coagulation and Filtration, ferric-based coagulants bind arsenic species, allowing removal by filtration [

4]. Adsorption with materials such as activated alumina and iron oxides adsorb arsenic effectively [

5]. Organic matter contributes to water color, odor, and formation of disinfection by-products. Pretreatment options include coagulation-Flocculation Effective for particulate and some dissolved organic matter [

6].

Biofilters and activated sludge systems biodegrade organic contaminants. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs): Generate hydroxyl radicals to mineralize organic compounds [

7].

The comparative efficiency of pretreatment methods applied during jar testing is summarized in

Table 1.

Pretreatment processes aimed at the removal of color, arsenic, and organic matter are essential for improving the efficiency of subsequent water treatment stages. Various methods such as coagulation-flocculation, adsorption, ion exchange, biological treatment, and advanced oxidation processes are widely used depending on the specific contaminant and water matrix [

4].

Among these technologies, Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF) has emerged as a highly effective pretreatment technique, particularly suitable for the removal of low-density particles, hydrophobic substances, and colloidal matter, which are often challenging to eliminate by conventional sedimentation or filtration methods [

8]. DAF operates by introducing microbubbles into the water stream, which adhere to suspended particles including color-causing organic matter, arsenic-associated particulates, and organic colloids. This flotation mechanism facilitates their separation and removal, thereby reducing the pollutant load before downstream treatments [

9]. For instance, DAF has proven particularly effective in improving the removal of natural organic matter and industrial dyes responsible for water color, outperforming traditional settling processes [

3]. In arsenic removal, DAF complements adsorption or ion exchange by eliminating iron precipitates and particulate-bound arsenic, thus enhancing overall treatment efficiency [

5]. Furthermore, when combined with coagulation-flocculation, DAF significantly reduces organic matter content, which is critical for minimizing the formation of disinfection by-products and protecting biological treatment units [

6]. In summary, integrating DAF into pretreatment schemes offers operational flexibility, improved contaminant removal, and reduced sludge volumes, which are advantageous for both municipal and industrial water treatment applications.

Based on available scientific literature, there is currently no knowledge or evidence suggesting that DAF system has been applied to groundwater of such complex quality as is the case with surface waters. Most studies focus on the treatment of surface waters, such as eutrophic lakes, industrial wastewater, or municipal wastewater.

For example, a study conducted in Harare demonstrated that DAF is highly effective in removing algae and reducing chlorophyll-a concentrations in water from Lake Chivero, achieving reductions of up to 95% [

10]. Similarly, research at the Midvaal Water Company in South Africa investigated the recycling of wastewater containing residuals from the DAF process within a drinking water treatment plant and confirmed that treatment efficiency for turbidity, chlorophyll, and suspended solids remained within acceptable limits [

11].

However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have evaluated the implementation of the DAF process for the treatment of groundwater with such complex chemical compositions, which highlights the novelty of this research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Existing Condition of the WTP

The previous system was designed according to the raw water quality analysis and the required standards for drinking water. It includes chemical pretreatment involving oxidation, coagulation and flocculation, as well as pH adjustment. Following this, ultrafiltration is applied, with the permeate being split into two streams: one directed to reverse osmosis and the other to ion exchange. The concentrate from the ultrafiltration unit is sent to sludge treatment. Approximately 50% of the influent flow undergoes reverse osmosis, with the concentrate from this process discharged into the sewage system. Ion exchange treatment is applied to part of the ultrafiltration permeate, operating either in parallel with reverse osmosis or sequentially after it, depending on the raw water quality. Wastewater from resin washing and regeneration is also discharged into the sewage system. The treated water was disinfected with sodium hypochlorite before distribution. Finally, sludge treatment involves directing the ultrafiltration concentrate to a lamella clarifier, where the clarified water is recycled back to the beginning of the treatment line, while the conditioned sludge, treated with polyelectrolyte, undergoes dewatering before being transported and disposed of at a sanitary landfill.

2.2. Water Quality

The raw groundwater used in this study was sampled from the Zrenjanin area, Serbia. The quality of the water exhibits considerable variation in physical, chemical, and microbiological parameters, which are typical for complex groundwater matrices. Parameters such as color, turbidity, pH, total dissolved solids, and specific ions were monitored to evaluate the suitability of the water for treatment by the DAF process. Raw water also contains specific elements such as arsenic and metals that require careful attention during pretreatment.

The raw water quality parameters are summarized in

Table 2, showing the measured values, observed ranges, and the maximum allowable concentrations (MAC) according to the Serbian Regulation on the Hygienic Safety of Drinking Water [

2].

The analysis of raw groundwater quality reveals several important characteristics relevant for drinking water treatment. The water exhibits a high color value of 60 °Pt-Co, substantially exceeding the regulatory limit of 5 °Pt-Co, which indicates the presence of dissolved organic matter and other color-causing compounds. Total organic carbon (TOC) was measured at 11 mg/L, reflecting a moderate organic load that may influence disinfection and overall treatment efficiency [

12]. Turbidity levels were low (0.65 NTU), and the pH of 7.72, along with a temperature of 17 °C, indicate conditions favorable for standard treatment processes.

Most inorganic constituents, including iron, manganese, calcium, magnesium, and various trace elements, were within or below their respective maximum allowable concentrations. However, several parameters exceeded regulatory limits, notably sodium (291 mg/L), ammonia (1.5 mg/L), KMnO4 consumption (40 mg/L), and arsenic (0.083 mg/L), highlighting key challenges for treatment. Dissolved oxygen was below 0.5 mg/l, consistent with the anaerobic nature of the groundwater, while nitrate and nitrite concentrations were negligible. Hydrogen sulfide was detected at low levels (0.015 mg/L), without a defined maximum limit.

Overall, these results indicate that the raw groundwater requires a multi-stage treatment approach capable of addressing both chemical and physical contaminants, with particular attention to the removal of color, ammonia, sodium, organic matter, and especially arsenic, to ensure safe and compliant drinking water production [

12].

2.3. Material and Methods

During 2022, an extensive series of laboratory experiments was conducted at the JCWI laboratory to evaluate and optimize the pretreatment of raw groundwater prior to the ultrafiltration process. The primary objectives were to investigate the removal of arsenic, color, and total organic carbon (TOC), and to provide practical guidelines for upgrading the existing water treatment process. Multiple combinations of coagulants and oxidants, including poly-aluminum chloride (PAC), ferric chloride (FeCl3), poly-electrolyte (PE), and sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), were applied at various dosages and timing intervals to determine their effectiveness under controlled laboratory conditions. Ferric chloride (FeCl3) was supplied by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Polyaluminum chloride coagulants BOPAC M4 and M5 were obtained from BOPAC, Belgrade, Serbia. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. The polyelectrolyte (PE) was supplied by Kemira, Helsinki, Finland.These experiments aimed to assess the impact of chemical type, dosage, and sequence of addition on the overall treatment efficiency and to identify optimal operational conditions for each reagent.

Given the complex composition of the raw groundwater, each adjustment and test series represented a unique challenge in achieving desired water quality improvements. Laboratory tests were complemented by additional experiments at the full-scale water treatment plant to verify and refine the laboratory findings. These efforts allowed the researchers to evaluate how the tested chemicals interact with the specific raw water matrix, providing insights into floc formation, growth, settling behavior, and overall process performance.

Jar testing, a widely applied laboratory technique, was employed to simulate coagulation and flocculation processes under controlled conditions. This method involves dosing parallel water samples in jars or beakers with selected chemicals, followed by rapid and slow mixing to promote floc formation and growth, and subsequent settling. By replicating actual treatment conditions, jar tests enable determination of the most effective coagulant types, dosages, and operational procedures before implementation at full scale. This approach also allows detailed observation of floc stability, sedimentation characteristics, and the influence of additional process parameters such as air injection [

13].

For this study, a selection of test series was conducted and is presented herein to illustrate the optimization of raw water treatment in terms of arsenic, color, and TOC removal. The experiments provided a foundation for constructing a more effective pretreatment process, including recommendations for dosing strategies, chemical combinations, and potential enhancements of DAF system.

2.3.1. Raw Water Sampling

In line with the sampling program, raw water was collected at the Zrenjanin intake on two occasions, representing peak and low flow conditions. During peak flow, a total of 70 L was obtained (30 L from Line 1 and 40 L from Line 2), while under low flow conditions 70 L was again collected (20 L from Line 1 and 50 L from Line 2). In both cases, composite samples of 15 L were prepared in the laboratory, proportionally reflecting the flow distribution between the two lines.

The collected raw water samples were obtained under well-defined hydraulic conditions at the Zrenjanin intake, ensuring that both flow and pressure variations were systematically documented for each distribution line. Composite sample volumes were prepared in accordance with the proportional flow contribution from each line in order to provide a representative characterization of the intake water. For Sample 1 (1 August 2022, 20:20), corresponding to peak flow conditions, Line 1 (DN 500 mm) operated at 119 L/s with a pressure of 2.5 bar, contributing 5.5 L to the composite sample, whereas Line 2 (DN 600 mm) carried 210 L/s at 2.8 bar, contributing 9.5 L. For Sample 2 (2 August 2022, 03:20), representing low flow conditions, Line 1 exhibited a reduced flow of 38 L/s at 2.5 bar, contributing 4.1 L, while Line 2 transported 98 L/s at 2.9 bar, contributing 10.9 L. In both cases, a composite volume of 15 L was obtained, proportionally reflecting the operational distribution of the two intake lines. All samples were collected in pre-cleaned containers, preserved and transported under controlled conditions to the JCWI Laboratory in Belgrade. This procedure ensured that the physicochemical integrity of the raw water was maintained prior to experimental jar testing and subsequent analytical determinations.

2.3.2. Jar Testing and Analysis

Applied Procedure

Upon delivery of the raw water samples to the JCWI laboratory (2 × 50 L), the JCWI expert team performed the required main sets of jar testing and analysis, consisting of 28 individual samples, along with two additional series to explore further variations in coagulant combinations and air injection effects. The experimental design aimed to systematically evaluate the performance of different chemical treatment strategies for arsenic, color, and TOC removal in raw water with varying characteristics.

The experimental series are summarized in

Table 3, which provides an overview of the sample series, applied chemicals, concentration ranges, and any special procedures, including air injection where relevant. The table enables a clear understanding of the experimental layout and highlights the systematic approach used to assess the efficiency of different chemical dosing strategies.

The jar testing procedure involved filling 1000 mL transparent jars with well-mixed raw water, which were then placed on a gang stirrer with identical paddle settings to ensure uniform mixing conditions. Chemicals were applied according to the specifications with NaOCl dosed 5 min prior to coagulants in relevant samples to allow sufficient oxidation. Rapid mixing was performed at 120–150 rpm for 5 min to promote uniform chemical distribution, followed by slow mixing at 45–60 rpm for an additional 5 min to facilitate floc formation. Samples were subsequently allowed to settle undisturbed for 30–40 min, after which the clarified water was carefully decanted into clean beakers without disturbing the settled sludge. The decanted water was then filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane to remove residual particles, and the filtrate was analyzed for arsenic, color, TOC, and other relevant parameters. In selected samples, such as S4, S5, S12, and S13, air was introduced for 5 min post-settling using air injection equipment, simulating flotation effects on the formed flocs and assessing the influence of aeration on floc stability and sedimentation behavior. The results from these experiments were subsequently interpreted to evaluate the effectiveness of different coagulants, identify optimal dosage ranges, and assess the potential benefits of air injection in enhancing the flocculation and settling processes [

13,

14,

15]. Jar testing provided a controlled environment to systematically study the interactions of raw water constituents with treatment chemicals. By summarizing the experimental series and chemical dosages in

Table 3, the design of the study is clear and reproducible, facilitating the identification of the most effective treatment conditions for full-scale pre-treatment processes such as DAF [

13].

All jar tests were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and minimize measurement uncertainty. The standard deviation for color, arsenic, and TOC results remained within ±5% of the mean values.

Series 1—JAR 1

Jar tests and analysis were performed for the second series of samples, referred to as JAR 2, using varying dosages of FeCl3 (40–120 mg/L), PAC (BOPAC M4, 20–30 mg/L), and chlorine (10–20 mg/L) for selected samples. The tests were conducted on the 4th of August in the JCWI Laboratory using the required chemicals and equipment.

The first series of jar tests (JAR 1) was conducted to evaluate the influence of FeCl

3, PAC (BOPAC M4), and NaOCl on coagulation and flocculation efficiency. Various dosage combinations were applied to determine the most effective treatment configuration for color, arsenic, and TOC reduction. FeCl

3 was dosed at concentrations ranging from 10 to 50 mg/L, PAC from 20 to 30 mg/L, and chlorine between 10 and 20 mg/, presented in

Table 4.

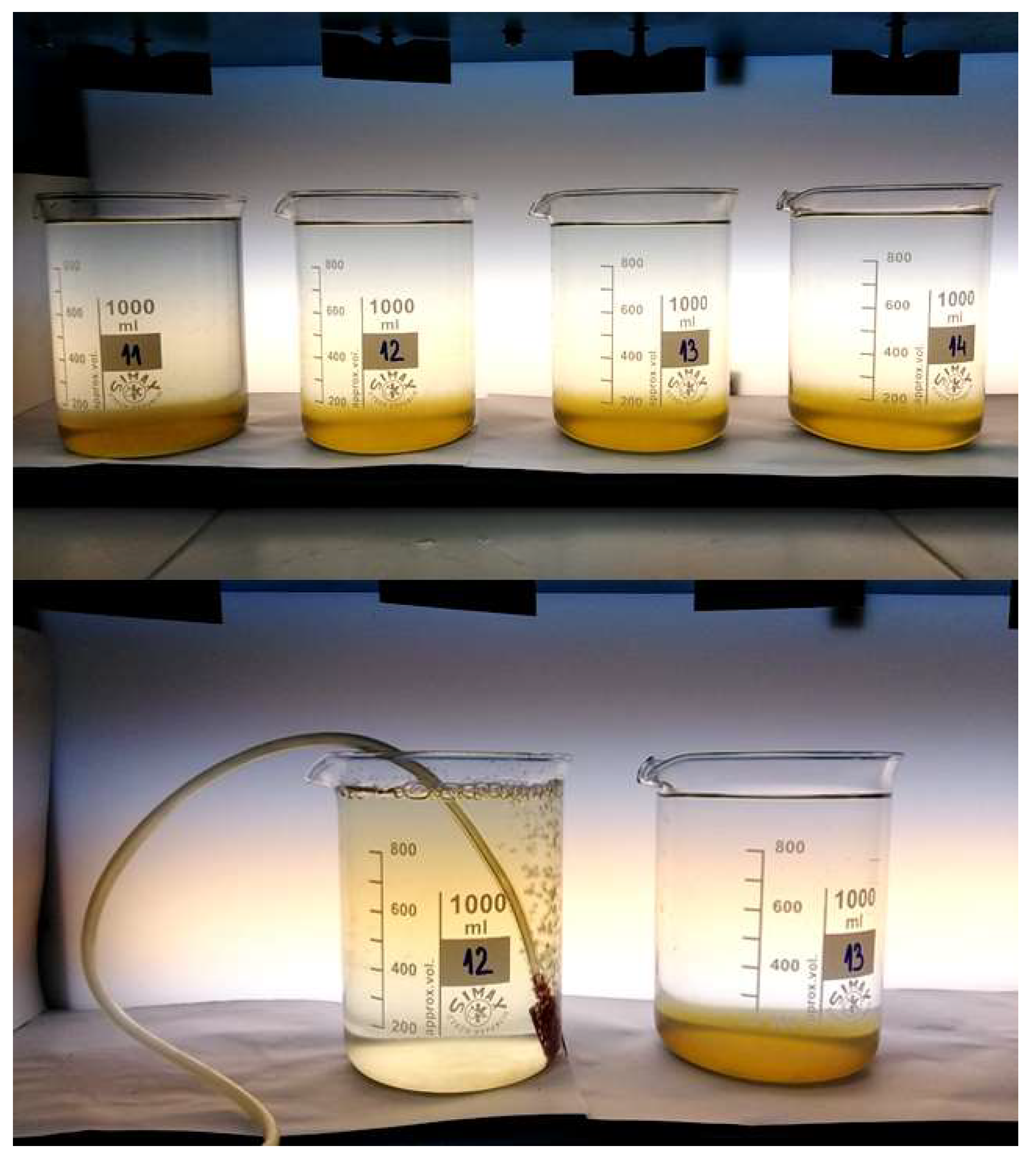

The visual appearance of the floc formation process is shown in

Figure 1, which depicts the mixing stage after coagulant addition.

Figure 2 illustrates the removal efficiency for color, arsenic, and TOC, respectively. The results clearly demonstrate that the combined application of coagulant and oxidant significantly enhances contaminant removal, with the most pronounced improvement observed in samples treated with optimized FeCl

3 and PAC dosages.

The settling and air-injection behavior of JAR 1 samples is presented in

Figure 3. Sequential visual observations of samples 11–14 after settling and samples 12 and 13 during and after air injection clearly demonstrate the influence of air introduction on floc stability and sedimentation behavior.

The removal efficiencies of color, TOC, and arsenic in the JAR 1 samples are summarized in

Table 5. The table presents the initial values measured in raw water, the range of values observed in the samples after pre-treatment, the best achieved values during the treatment series, and the corresponding percentage reductions. This overview highlights the effectiveness of the treatment process in improving water quality.

Table 5 summarizes the removal efficiencies of color, total organic carbon (TOC), and arsenic in the JAR 1 samples, showing initial values, final value ranges, best achieved values, and percentage reductions. The results highlight that the addition of PAC (S11–S14) significantly improved floc formation and stability, leading to the lowest observed values (Best column). Tests with FeCl

3 only (S2–S7) produced small, unstable flocs and limited water quality improvement. Aeration (S12, S13) temporarily dispersed flocs, which re-aggregated upon cessation, forming clearer supernatant layers. Overall, the combination of FeCl

3 and PAC provided the most effective removal of color, TOC, and arsenic, as reflected in the Final Value ranges and Best values.

Series 2—JAR 2

Jar tests and analysis were performed for the second series of samples, referred to as JAR 2, with specific chemical dosages and combinations. The tests involved varying doses of coagulant FeCl

3 (40–120 mg/L) and PAC (BOPAC M4, 20–30 mg/L), along with chlorine dosing (10–20 mg/L) for selected samples. The jar testing was carried out in the JCWI Laboratory using the required chemicals and equipment. The chemical dosages applied to each sample are summarized in

Table 6.

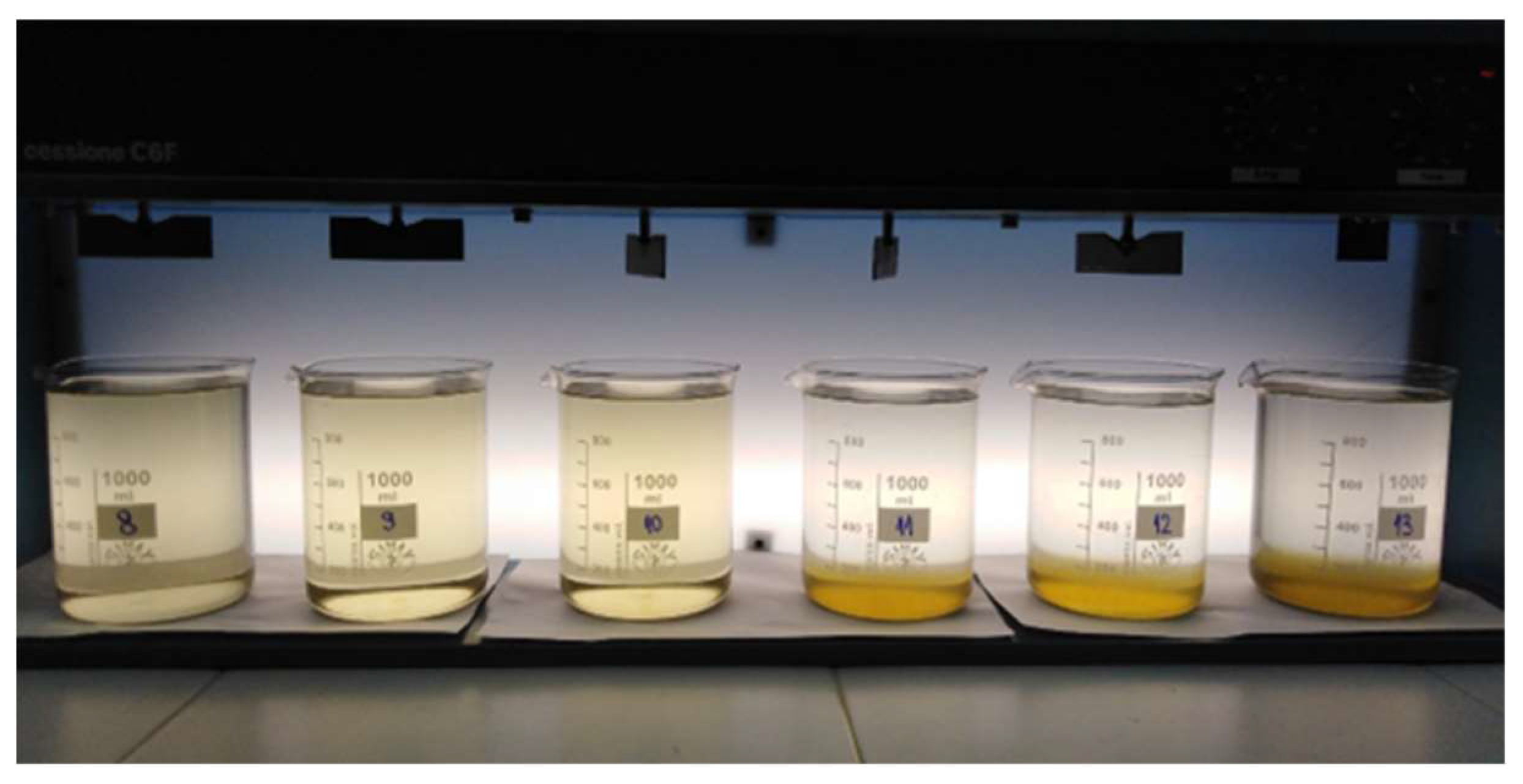

In

Figure 4, samples S8–S13 after settling show the differences in floc formation depending on the chemical dosages applied. Samples containing only FeCl

3 exhibit smaller and less stable flocs, while samples with PAC (S11–S13) form dense and rapidly settling flocs.

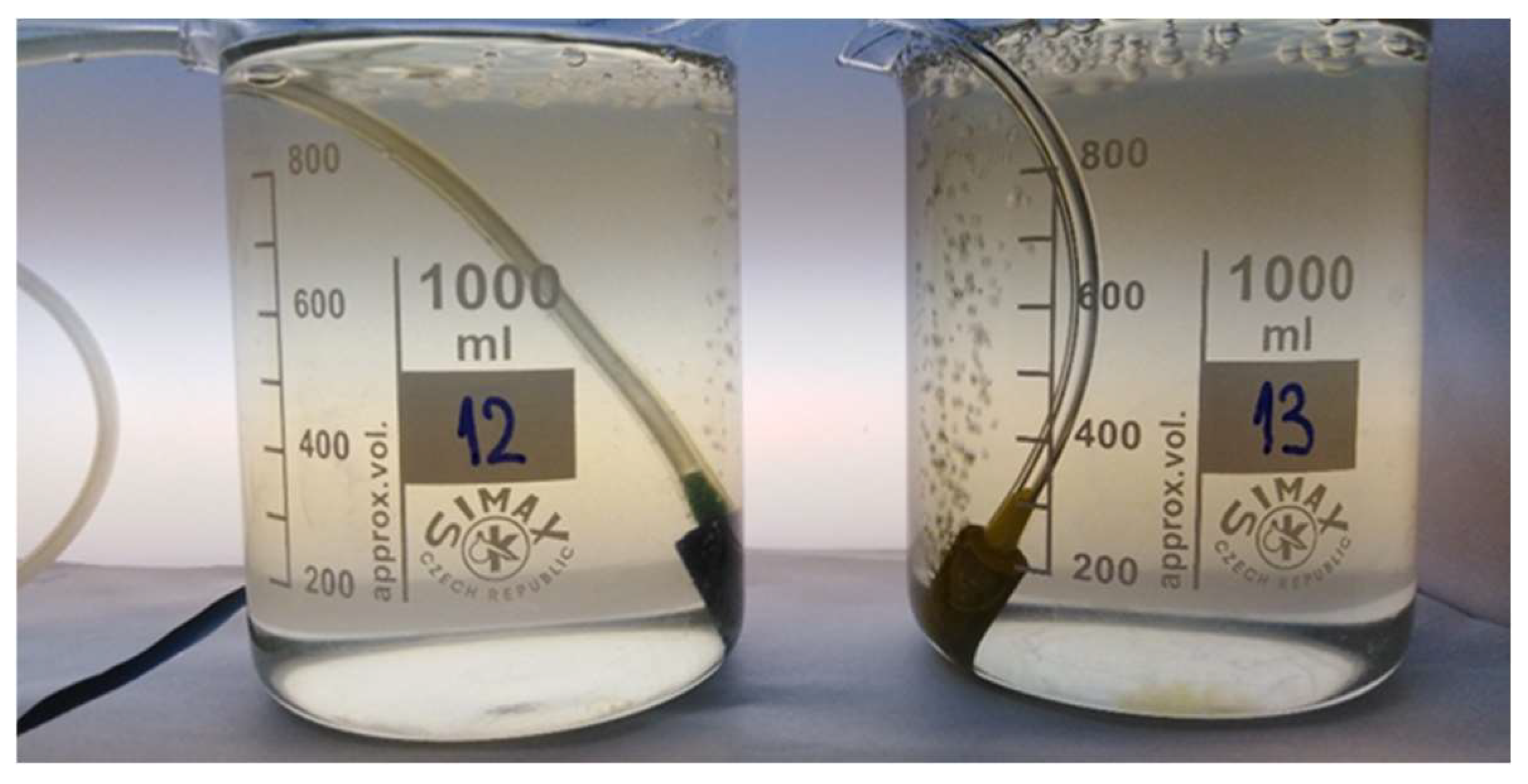

The effect of air injection on PAC-containing samples is shown in

Figure 5. During aeration, the flocs temporarily disperse throughout the water column, illustrating their buoyancy and the transient disruption of floc structure.

Figure 6 shows the behavior of the same samples (S12 and S13) 30 min after stopping aeration. The flocs re-aggregate and settle to the bottom, although the settling process requires slightly more time compared to samples that were not aerated. These observations confirm that PAC is essential for maintaining floc integrity during air-assisted flotation, while samples without PAC do not re-form stable flocs after air injection.

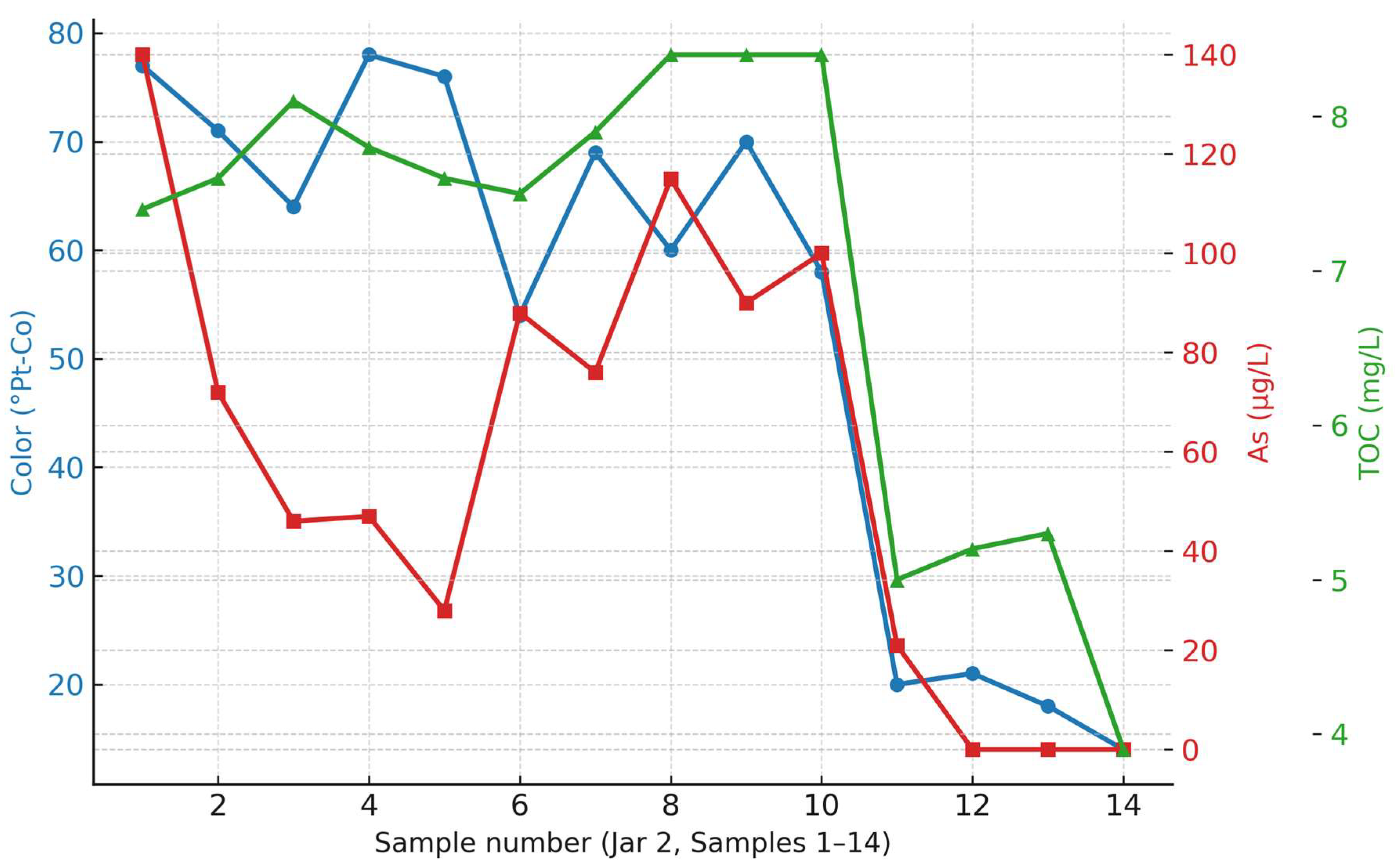

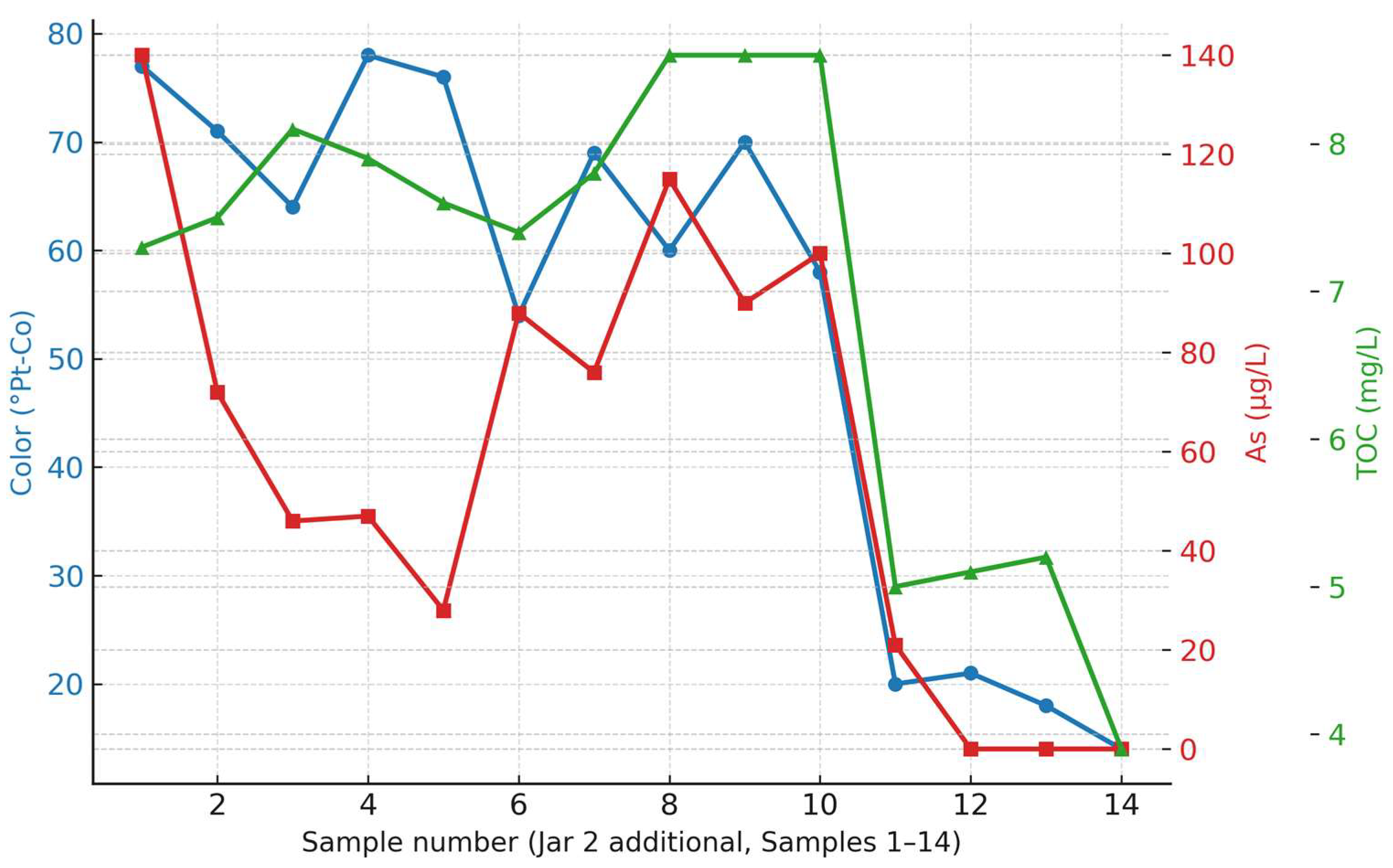

Color, arsenic and TOC removal trends obtained in Jar Test 2 are given in

Figure 7.

Figure 7 illustrates the removal efficiency for color, arsenic, and TOC, respectively for JAR 2 samples.

Similar to the observations in JAR 1, samples without PAC (S2–S10) produced only a few small and unstable flocs, resulting in no significant improvement in water quality. The addition of PAC (BOPAC M4, S11–S14) led to stable floc formation, with rapid settling in 5–8 min. In selected PAC-containing samples, air injection temporarily dispersed the flocs throughout the water column; once aeration ceased, they re-aggregated and settled, although requiring slightly more time. Samples without PAC experienced floc breakdown under air injection, with flocs remaining dispersed and no sedimentation. Higher doses of FeCl

3 alone produced slightly larger flocs, but without substantial changes in settling behavior or pollutant removal. The chemical dosages applied in each sample are summarized in

Table 7.

Series 3—JAR 3–JAR 2 ADDITIONAL

Jar tests and analysis were conducted for an additional series, designated as JAR 2 ADDITIONAL, with the applied chemicals and dosages summarized in

Table 8. The tests involved various combinations of FeCl

3, PAC (BOPAC M4), and PE, in order to further evaluate coagulant efficiency and floc stability under different conditions. The experimental setup and dosing strategy were developed based on the outcomes of previous JAR 2 tests. Testing was carried out in the JCWI Laboratory, using the required chemicals and standard jar testing equipment.

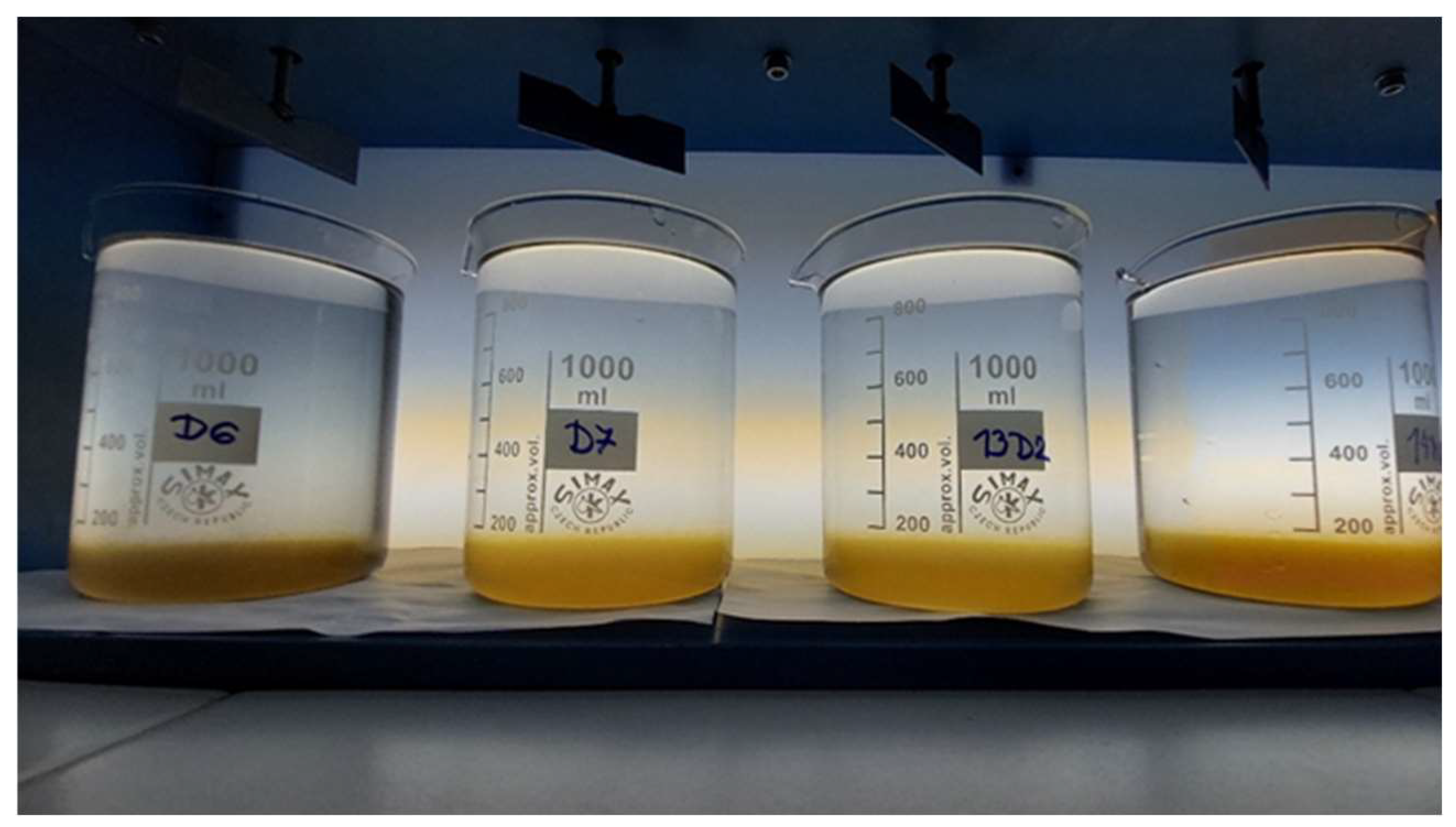

Settling of additional samples (Jar 2: 12D–14D) is presented in

Figure 8.

The comparative behavior of color, arsenic, and TOC removal during the JAR 2–ADDITIONAL series is presented in

Figure 9. The diagram clearly illustrates the influence of different PAC doses on treatment efficiency. A gradual improvement in color and arsenic removal can be observed with increasing PAC concentrations, particularly in samples 12D–14D, where the combined FeCl

3–PAC treatment achieved the highest removal rates. In contrast, the application of PE did not enhance removal efficiency and, in certain cases, resulted in less stable floc formation. TOC reduction followed a similar trend, confirming that the combined coagulant–oxidant dosing produced the most consistent effects.

The obtained results from the JAR 2–ADDITIONAL series confirm that different PAC doses have a significant influence on the treatment efficiency, while the PE dosage did not produce the expected effects, in some cases even leading to lower removal efficiency. As summarized in

Table 9, the highest removal of color, TOC, and arsenic was achieved in samples 12D–14D, which exhibited 70–80% color reduction, 45–55% TOC reduction, and more than 90% arsenic removal.

These findings are consistent with previous test series (JAR 1 and JAR 2), indicating that an approximate FeCl3:PAC dosage ratio ensures optimal coagulation–flocculation performance and stable settling behavior.

Series 4—JAR 3–JAR 2 ADDITIONAL 2

Jar tests and analysis were conducted for an additional series, designated as JAR 2 ADDITIONAL 2, with the applied chemicals and dosages summarized in

Table 10. This series aimed to verify and optimize the coagulant performance observed in previous tests by introducing a different type of PAC (BOPAC M5) in combination with FeCl

3. The selected samples corresponded to those that demonstrated the best removal efficiency in the earlier series, with minor variations in dosages applied for two of them.

The chemical dosages applied in the JAR 2 ADDITIONAL 2 series are summarized in

Table 10.

Settling of the second set of additional Jar 2 samples (D16, D17, 13D2, 14D2) is shown in

Figure 10.

The comparative removal efficiencies in the JAR 2 ADDITIONAL samples (1–14) are shown in

Figure 11.

The tested setups were designed based on the most effective results from previous series, with slight modifications in FeCl3 and PAC ratios to verify their influence on the removal efficiency of color, TOC, and arsenic.

The results of the JAR 2 ADDITIONAL 2 series (

Table 11) confirm that the type of PAC strongly affects treatment efficiency. As shown, BOPAC M5 achieved the highest color removal (≈80–85%) and good TOC reduction (≈70%), while BOPAC M4 provided better arsenic removal (≈75–80%). These results demonstrate that variations in PAC composition influence coagulation behavior and overall removal performance.

2.3.3. DAF System Implementation and Analysis

After conducting a series of laboratory tests involving coagulation, flocculation, and settling experiments with FeCl3, PAC, and other coagulants, it was concluded that significant improvements in water quality could be achieved by implementing DAF system. The tests demonstrated substantial reductions in key parameters such as color, TOC, and arsenic, with DAF treatment proving to be highly effective in removing suspended particles, organic matter, and heavy metals.

Based on these promising results, the decision was made to upgrade the existing treatment plant by constructing a dedicated DAF unit designed to pre-treat raw water before further purification. This upgrade aims to enhance the plant’s capability to manage variations in raw water quality and ensure effective treatment from the initial stages.

This analysis evaluates the performance of the DAF system in treating raw water using defined chemical dosages of NaOCl, FeCl3, and PAC, focusing on the parameters color, arsenic, and TOC. The evaluation is based on data collected on October 31, 2023, comparing results from both raw water and DAF-treated samples (DAF-1.1 and DAF-1.2).

The applied chemical doses and operational conditions during the DAF testing are summarized in

Table 12.

Here, DAF-1.1 refers to the first process line, while DAF-1.2 represents the second, each designed to increase treatment capacity and improve water quality at different stages of the system.

The removal efficiencies of color and KMnO

4 consumption achieved during DAF treatment are presented in

Table 13.

The results suggest that the DAF treatment system is highly effective in improving water quality by significantly reducing both color and KMnO4 consumption. The second line of the DAF system (DAF-1.2) demonstrated better performance in both parameters, indicating that the system’s efficiency improves with subsequent treatment stages. The DAF process proved to be highly successful in removing color-causing compounds and organic matter, contributing to the overall enhancement of water quality. These improvements suggest that the DAF system plays a crucial role in addressing water quality issues, especially in terms of organic contamination and color removal.

These tests were conducted with a flow capacity of 60 L/s, and after fine-tuning the air injection system, the efficiency achieved closely matched the values observed during the JAR tests when the plant operated at a flow capacity of 200 L/s. This adjustment enabled the DAF system to operate more effectively, maintaining optimal performance even at different flow rates.

3. Discussion

The laboratory tests conducted across four series (JAR 1, JAR 2, JAR 2 ADDITIONAL, and JAR 2 ADDITIONAL 2) provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of different chemical dosages and combinations in improving coagulation, flocculation, and overall water quality. The results confirmed that the DAF process, optimized through FeCl3 and PAC ratios determined in the JAR tests, achieved consistently high removal efficiencies for color, TOC, and arsenic. A strong linear correlation (R2 = 0.98) was observed between color removal and KMnO4 consumption, indicating that the removal of visible and oxidizable organic compounds followed similar kinetics. The small standard deviations obtained across triplicate measurements confirmed the reproducibility and stability of the process.

Comparison with previously published studies [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] revealed that DAF performance in this research was notably higher (arsenic removal up to 90%), primarily due to optimized FeCl

3/PAC ratios and better pH control. During both jar and pilot-scale testing, the air injection system was improvised, providing a practical yet limited representation of full-scale DAF operation. Although the effect of air pressure and temperature on microbubble formation was not quantified in this study, qualitative observations indicated that air dispersion and bubble stability could influence flotation performance. These aspects will be examined in future research focusing on thermodynamic effects and air injection optimization [

23,

24].

Overall, the results highlight the key role of FeCl

3 and PAC in optimizing coagulation and flocculation processes, particularly for the removal of arsenic, organic matter, and color. The findings are consistent with previous studies, which demonstrate that the combined use of PAC and FeCl

3 enhances floc formation, improves contaminant removal, and accelerates settling rates [

11].

The summarized results of all JAR test series are presented in

Table 14, which provides a comparative overview of the best-performing samples and their corresponding removal efficiencies for color, TOC, and arsenic.

3.1. Coagulation Mechanisms with FeCl3 and PAC

In Series 1 (JAR 1), when FeCl

3 was applied without the addition of PAC, coagulation led to the formation of unstable and poorly settled flocs. The main chemical reaction of FeCl

3 in water involves its dissociation into Fe

3+ ions, which neutralize the negative charges on suspended particles, allowing them to aggregate into flocs. However, without PAC, the flocs formed were small and lacked the stability required for effective removal. This mechanism is explained by the following reaction:

Similar behavior was reported by Han and Park [

19] and Gao et al. [

21], who noted that microbubble stability and floc–bubble attachment are highly dependent on both hydrodynamic and thermodynamic conditions within the DAF chamber. This finding is consistent with the mechanisms observed in the present study, especially the enhanced flotation at optimal PAC doses.

As seen in the results, the color reduction was minimal (only a 6.9% reduction, from 58.00 °Pt-Co to 54.00 °Pt-Co), and the arsenic concentration showed a negligible decrease of 5.7% (from 108.7 µg/L to 102.5 µg/L). The inability of the flocs to settle effectively can be attributed to the lack of additional bridging provided by PAC, which is known to stabilize and enhance the flocculation process.

Upon introducing PAC, a different chemical mechanism comes into play. PAC hydrolyzes in water to form aluminum hydroxide species, such as Al

6(OH)

193+, which act as bridges between particles. This promotes the formation of larger, more stable flocs. The resulting flocs are not only larger but also more cohesive, facilitating faster and more efficient settling. The hydrolysis of PAC can be represented by the following reaction:

This mechanism is supported by the experimental results, where the addition of PAC reduced color from 58.00 °Pt-Co to 25.00 °Pt-Co, a 57.5% reduction, and arsenic from 108.7 µg/L to 50.5 µg/L, marking a 53.5% decrease. These results clearly demonstrate that PAC enhances the coagulation process by forming stable flocs, leading to faster settling and improved contaminant removal. This aligns with findings from [

12] who also observed that PAC significantly improves floc stability and settling characteristics, leading to better water quality.

3.2. Impact of Air Injection and DAF Process

The subsequent addition of air in Series 2 (JAR 2) simulates the DAF process, where microbubbles attach to the flocs, facilitating their flotation to the surface for removal. This mechanism is further enhanced by PAC-induced flocs, which are larger and denser, thereby improving their buoyancy. In the air-injection tests, flocs initially dispersed but regrouped and settled over time, mimicking the behavior seen in DAF systems.

This phenomenon demonstrates the synergy between chemical coagulation and physical flotation. As the air bubbles attach to the PAC-enhanced flocs, the larger surface area and greater floc stability provide better flotation characteristics. This behavior is consistent with previous studies, such as [

25], which showed that PAC enhances the flotation efficiency in DAF systems by improving floc stability and flotation dynamics.

3.3. Effect of FeCl3 Dosages and PAC-to-FeCl3 Ratio

In Series 2, the addition of higher doses of FeCl3 (up to 50 mg/L) led to the formation of larger flocs, but these did not result in significant improvements in pollutant removal or settling time, especially for arsenic. This is likely because, even though the flocs were larger, FeCl3 alone cannot achieve the level of floc stability required for optimal removal. This was evidenced by JAR 2 S7 (with 50 mg/L FeCl3), where color was reduced by only 31% (from 58.00 °Pt-Co to 40.00 °Pt-Co) and arsenic was reduced by 19.8% (from 91.5 µg/L to 73.4 µg/L).

In contrast, when PAC was added, the reduction in color and arsenic was significantly greater. For example, in JAR 2 12D (15 mg/L FeCl

3 + 25 mg/L PAC), color decreased from 58.00 °Pt-Co to 20.00 °Pt-Co (a 65.5% reduction) and arsenic was reduced by 90.8% (from 108.7 µg/L to 10.0 µg/L). This confirms the findings of [

11] who found that PAC is essential for improving coagulation and enhancing contaminant removal, especially in cases where FeCl

3 alone does not produce the desired results.

3.4. Comparing Different PAC Types: BOPAC M4 vs. BOPAC M5

In JAR 2 ADDITIONAL 2, a different type of PAC, BOPAC M5, was tested alongside FeCl

3. The results showed that BOPAC M5 was particularly effective for color removal, reducing it from 58.00 °Pt-Co to 14.00 °Pt-Co (a 75.9% reduction). However, its efficiency in removing arsenic was lower compared to BOPAC M4, which achieved a 53.5% reduction in arsenic (from 91.5 µg/L to 50.5 µg/L), while BOPAC M5 achieved a 44.8% reduction. These findings indicate that BOPAC M4 is more effective overall in terms of arsenic removal, whereas BOPAC M5 is more efficient in color removal. This is consistent with the research of [

11] who highlighted that the choice of PAC type can significantly influence the removal of specific contaminants, depending on the chemical structure and polymerization properties of the PAC used.