1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of e-commerce and on-demand logistics has renewed interest in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) delivery systems as a promising solution for last-mile distribution [

1]. UAVs can reduce delivery time and operating costs and provide access to congested or remote locations, but their practical deployment is challenged by limited payload and endurance, strict time-slot requirements, and highly dynamic customer behavior. In particular, delivery operators must plan strategic depot locations and UAV fleet sizes while coping with daily stochastic demand fluctuations and probabilistic same-day slot modifications (e.g., requests moved to other time slots), which couple strategic and operational decisions under uncertainty.

Despite extensive research on UAV logistics, prior studies often address strategic depot location, fleet sizing, or operational UAV assignment separately, leaving a gap in frameworks that integrate both levels under stochastic daily demand and probabilistic same-day modifications [

2,

3,

4], as summarized in

Section 2. To fill this gap, this paper develops a unified two-stage modeling and solution framework for UAV-based last-mile delivery that simultaneously optimizes depot locations, fleet sizes, and operational assignments while capturing stochastic demand fluctuations and same-day modifications.

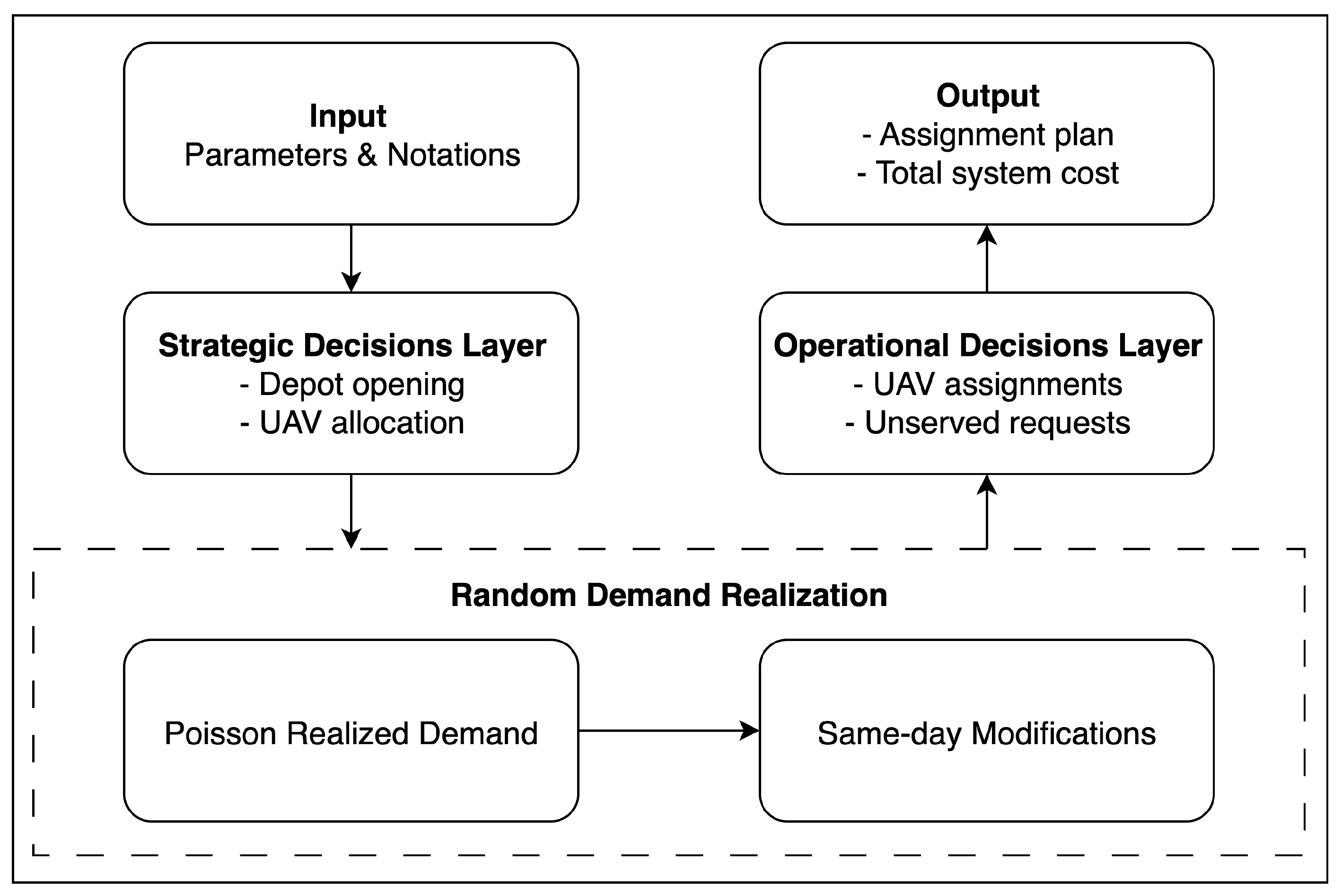

The two-stage decision framework integrates strategic depot location and UAV fleet allocation (first stage) with operational assignment and timing decisions (second stage). First-stage decisions, including which depots to open and how many UAVs to allocate, are made prior to observing realized daily demand. In the second stage, UAV trips are assigned to actual customer requests in discrete time slots, accounting for UAV capacity limits and delivery distance restrictions. Our modeling choices are motivated by practical operational considerations: the day is discretized into T atomic time slots, UAVs perform depot–customer–depot trips, and daily nominal requests follow a Poisson-like count process. Same-day modifications are allowed to reassign the entire realized demand of a slot to any other slot or remove it altogether for the day.

We consider three strategic models that reflect different attitudes toward demand uncertainty. In the deterministic model, total cost is minimized using the nominal demand as the realized demand. The stochastic model, solved via Sample Average Approximation (SAA), minimizes expected total cost across sampled demand scenarios representing demand uncertainty. The robust model minimizes the sum of strategic costs and the maximum operational cost under admissible demand deviations and slot modifications, constrained by uncertainty budgets and . Across all three models, the common objective is to minimize the total system cost, which includes depot opening costs, per-UAV procurement costs, and operational costs, where service costs are proportional to the UAV travel distance and unserved requests incur penalty costs. The performance of the three models is validated through simulation experiments under stochastic demand realizations.

From an algorithmic perspective, the deterministic and SAA formulations can be solved directly as integer programming models using a commercial solver. In contrast, the robust formulation leads to a computationally challenging max–min structure, where for a given strategic decision, an adversarial agent seeks adverse demand realizations that maximize the operational cost. To tackle this, we develop a logic-based Benders decomposition (LBBD) framework. In all three models, depot fleet sizes are inherently integer quantities. For the robust model, these integer decisions are further decomposed into binary components to facilitate the construction of Benders cuts, linking strategic allocation decisions to evaluated adverse operational costs. To avoid repeatedly solving the computationally intensive adversarial problem, a set of candidate adverse scenarios is precomputed using heuristic procedures. Evaluated costs are incorporated as lazy optimality cuts, while previously assessed assignment patterns are recorded to avoid redundant evaluations. In addition, a nominal deterministic lower bound is computed at the outset to tighten the master problem, ensuring convergence and computational efficiency.

The main contributions of this paper are threefold. First, we propose a unified two-stage modeling framework for UAV-based delivery that integrates strategic depot location, UAV allocation, and operational assignment while explicitly capturing both Poisson-like daily demand fluctuations and same-day slot modifications. Second, we develop a computational strategy for the robust min–max problem based on LBBD, incorporating an adversarial problem, binary decomposition of fleet variables, and a practical multi-heuristic adversarial scenario generator. Finally, we provide an open implementation and conduct extensive simulation-based experiments to evaluate the deterministic, stochastic, and robust models, thereby illustrating the trade-offs between nominal efficiency and robustness.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 introduces the deterministic, SAA, and robust models.

Section 4 describes the robust reformulation and the LBBD framework.

Section 5 reports computational and simulation-based results, and

Section 6 concludes with key insights and directions for future research.

2. Related Work

The UAV-based last-mile delivery problem has received significant attention due to the rapid growth of e-commerce and the need for timely deliveries [

4,

5]. As e-commerce continues to expand, customer expectations for fast and reliable delivery have placed increasing pressure on logistics systems, motivating the study of UAVs as a complementary or alternative delivery mode. Prior research relevant to this paper can be broadly categorized into three areas: (i) facility location and fleet sizing, (ii) routing and scheduling, and (iii) planning under demand uncertainty. Each of these areas addresses different aspects of UAV-based logistics, ranging from long-term strategic planning to operational decisions [

6].

Strategic decisions on depot placement and fleet sizing are critical for efficient UAV-based logistics systems. Several studies have formulated facility location problems under deterministic or stochastic demand to identify optimal depot locations and determine fleet sizes that balance cost and service quality. Dukkanci et al. [

3] conducted a comprehensive literature review on UAV facility location, covering both UAV-only delivery networks and hybrid systems that coordinate UAVs with other transportation modes. Due to the computational complexity of these problems, heuristic and metaheuristic approaches have been widely proposed [

7,

8]. Hybrid and UAV-only delivery systems have been examined under various constraints to enhance delivery efficiency [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Despite these contributions, the interaction between strategic depot placement and operational UAV assignment under discrete stochastic demand remains insufficiently explored, which constitutes a core motivation of this study.

Routing and scheduling for UAVs have also been extensively studied [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Early works generally assumed deterministic settings, where UAVs serve customers with known demands and travel times. Subsequent research incorporated additional operational constraints, including time windows, speed variation, payload and battery limitations, as well as dynamic or stochastic operational factors [

17,

18,

19,

20]. In some delivery applications, UAVs can carry only one customer order per time slot due to payload restrictions [

7], a setting that is also adopted in this paper. In addition, we consider a demand modification constraint, which allows customers to adjust their delivery time windows to accommodate periods when they are unavailable or unable to receive a delivery.

Uncertainty in daily demand is a central challenge in UAV logistics, affecting both strategic and operational decisions. While various studies have attempted to address this challenge, many still rely on deterministic assumptions or simplified stochastic settings, limiting their applicability in highly dynamic, demand-uncertain environments. To address this, both stochastic and robust optimization frameworks have been widely applied. Stochastic programming approaches, such as SAA, have been used to optimize fleet sizing and assignment [

20], while robust optimization models consider worst-case demand realizations [

21,

22]. Scenario generation and decomposition techniques have been introduced to improve computational efficiency and solution quality. In particular, LBBD and heuristic methods have proven effective for solving complex problems under uncertainty [

23,

24]. However, few studies systematically compare approaches to modeling uncertainty or integrate them into multi-stage UAV planning frameworks. In this paper, our computational strategy adapts LBBD to the single-customer-per-slot structure and incorporates a multi-heuristic scenario generator, enabling robust and practical planning for UAV delivery.

Our work is closely related to the literature on two-stage optimization frameworks for strategic and operational planning [

25]. In these frameworks, first-stage decisions, such as depot locations and fleet sizes, are made before observing demand, while second-stage decisions, including UAV assignments and routing, adapt to the realized demand. For example, Park et al. [

26] studied UAV deployment in emergency medical services, employing robust optimization with a tailored branch-and-bound algorithm. Zhang et al. [

27] proposed a two-stage model for fleet sizing and real-time task allocation in emergency missions, determining the optimal number of UAVs strategically and assigning tasks tactically. Similarly, Bruni et al. [

2] integrated location, fleet planning, and operational allocation into a unified two-stage framework. While these studies provide valuable methodological insights, they typically assume fixed demand distributions or neglect flexible customer-side modifications. Our approach extends this line of research by explicitly modeling (i) Poisson-like stochastic demand patterns and (ii) same-day slot modifications, thereby bridging strategic and operational levels under realistic uncertainty in UAV logistics.

As shown in

Table 1, existing studies typically consider strategic or operational decisions separately, or they neglect stochastic demand with same-day modifications. Few studies integrate (i) strategic depot location and fleet allocation, (ii) operational UAV assignment under discrete time slots, and (iii) stochastic daily demand with same-day modifications. To address this gap, this paper develops a unified two-stage framework that combines deterministic, stochastic, and robust models for last-mile UAV delivery while reflecting practical operational requirements and ensuring computational tractability.

3. Problem Description and Mathematical Models

3.1. Problem Description

We consider a UAV-based parcel delivery system with a set of candidate depots and a set of potential customers . The planning horizon is divided into T equal-length time slots, . Decisions are made at two interconnected layers: at the strategic layer, binary variables indicate whether depot i is opened, and integer variables specify the number of UAVs allocated to depot i, subject to depot capacity and total fleet size R; at the operational layer, integer variables denote the number of UAVs from depot i serving customer j in time slot t, and slack variables indicate unserved requests.

The system faces two sources of randomness. First, the daily demand for customer j at slot t follows a Poisson distribution, resulting in stochastic realized demand . Second, each realized request may be modified on the same day with a given probability, transferring the demand to another time slot; the final demand after same-day modifications is denoted by . These two factors capture both the stochastic number and spatial distribution of customer requests and the probabilistic same-day modifications.

Each UAV can serve at most one customer per trip and must return to its depot before the next trip. Operational scheduling thus reduces to a capacity-constrained assignment problem with simple depot–customer–depot trips. The objective is to minimize the total system cost, which includes fixed depot opening costs , UAV procurement costs , and operational costs composed of serving costs and penalties for unserved requests, under the constraints of depot capacities and UAV fleet size.

Before presenting the model, we summarize and justify the main assumptions underlying the proposed formulation: (1) customer demand

follows independent Poisson distributions across customers and time slots, a widely adopted assumption in parcel delivery research [

17,

19,

31]; (2) each realized demand may be modified within the same day with a given probability, transferring to another time slot to reflect short-term rescheduling behavior; (3) each UAV can serve at most one customer per trip. This simplification, also adopted in several related studies [

7,

10,

11,

21], transforms the operational problem into a tractable assignment model while maintaining the focus on depot location and UAV allocation decisions; (4) each depot

i has a maximum UAV capacity

, and the total fleet size is limited to

R; and (5) decision-making is carried out in two layers: depot opening and UAV allocation at the strategic level, followed by assignment decisions at the operational level.

These assumptions intentionally simplify operational details such as multi-customer routing, UAV heterogeneity, and contextual factors such as weather conditions and order priority, allowing the model to remain tractable and focused on the integration of strategic and operational decisions.

All notations used in the mathematical model are summarized in

Table 2.

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the UAV allocation and operational scheduling process consists of strategic decisions, stochastic demand realization, and operational assignments.

3.2. Uncertainty Sets

3.2.1. Demand Deviation Uncertainty (Cardinality-Constrained)

Let

denote the nominal demand, which represents the expected number of UAV requests from customer

j in time slot

t. The realized demand before same-day modifications, denoted by

, may deviate from

, but the total deviation is bounded by the uncertainty budget

. Following Bertsimas and Sim [

32], we define the following:

3.2.2. Same-Day Modification Uncertainty

In addition, same-day operations may shift requests across time slots. For each , the entire realized demand is either kept at t, reassigned to another slot , or canceled. To model such moves, we introduce binary indicators:

: equals 1 if demand originally at is reassigned to slot , with meaning no change,

: equals 1 if slot is modified,

: number of UAVs reassigned from to slot .

These variables are subject to the following constraints:

Constraints (

2)–(

4), together with the total modification budget, define the set of admissible modifications, denoted as follows:

3.3. First-Stage (Strategic) Models

The first-stage problem determines which depots to open () and the number of UAVs to allocate to each depot () before observing the realized customer demand. The objective is to minimize the total system cost, which includes depot opening costs, UAV procurement costs, and the operational cost to serve customer requests. The decisions are subject to a total UAV fleet limit R and per-depot capacity .

Deterministic model: Assuming that customer demand is known and equal to the nominal forecast

, the first-stage problem is as follows:

SAA model: Given a set of sampled scenarios

, where each scenario is equally likely, the first-stage problem minimizes the expected total cost approximated by the average over all sampled scenarios:

Robust model: To hedge against adverse demand realizations, first-stage decisions are optimized over two types of uncertainty: daily demand deviations (

with budget

) and same-day modifications (

with budget

):

3.4. Second-Stage (Operational) Model

Given first-stage decisions

, the second-stage operational cost

is obtained by a capacity-constrained assignment problem allocating UAVs to customer requests. Let

denote the number of UAV trips from depot

i to customer

j in time slot

t, and let

denote unserved requests. The general formulation is as follows:

The realized demand depends on the modeling context:

Deterministic nominal: , i.e., using the nominal demand forecast for all customers and time slots.

Stochastic (SAA): Given a set of sampled scenarios with equal probability, each scenario s has a realized demand after applying sampled same-day modifications. Corresponding assignment variables and are defined for each scenario.

Robust: corresponds to an adverse demand and modification scenario within the uncertainty sets and .

Constraint (

15) ensures that each request is either served or counted as a failure, and constraint (

16) enforces depot capacity limits. Deterministic and SAA models can be solved exactly as MIPs, whereas robust models cannot be solved directly; reformulation and decomposition techniques are introduced in

Section 4.

4. Robust Model Reformulation

This subsection presents a reformulation of the robust model, employing an LBBD approach to achieve an efficient solution.

4.1. Two-Stage Min–Max Framework via LBBD

The robust model aims to determine first-stage decisions

that minimize the operational cost under the most adverse demand realizations considered within predefined uncertainty sets

and

. For a given first-stage solution

, the adversarial model selects demand deviations and slot modifications to maximize the second-stage cost. This yields a two-stage min–max problem:

In our solution approach, we employ an LBBD strategy:

Master problem: Optimizes first-stage decisions subject to Benders cuts generated by previous adversarial solutions.

Adversarial subproblem: For a given , solves a MILP to identify adverse demand realizations that maximize the second-stage cost.

Benders iteration: The adversarial subproblem returns the evaluated adverse operational cost (optimality cut), which is then used to refine the master problem.

This iterative process continues until convergence, i.e., when no further cuts can improve the first-stage solution, yielding a robust optimal solution.

4.2. Adversarial MILP Formulation

For a given first-stage decision

, the adversarial MILP chooses demand deviations and slot modifications to maximize the second-stage cost, subject to constraints (

2)–(

4) and budgets

,

. The inner maximization problem can be formulated as the following MILP:

Constraints (

20)–(

21) enforce feasibility of assignment decisions, (

22)–(

25) define effective demand after modifications, and (

26)–(

27) implement the budgets on demand deviations and modifications. The full robust model is thus a bilevel problem: the outer level optimizes

, and the inner adversarial MILP seeks adverse demand realizations that maximize the operational cost.

While the above MILP accurately represents the adversarial problem, solving it to optimality at every LBBD iteration is computationally prohibitive. To address this challenge, we approximate the inner maximization by generating candidate worst-case scenarios via a multi-heuristic procedure that strictly satisfies the uncertainty budgets . This approach does not aim to identify the exact worst-case realization but rather a representative set of highly adverse scenarios sufficient to ensure robustness of the first-stage decisions.

4.3. Heuristic Scenario Generation Within the LBBD Framework

Due to the computational difficulty of solving the adversarial MILP at each iteration, we generate candidate worst-case scenarios using a multi-heuristic procedure. Specifically, five distinct heuristics are employed to construct feasible realizations that satisfy the uncertainty budgets and : (i) a concentration heuristic transfers demand deviations from multiple sources to a targeted customer–time pair; (ii) a spread heuristic distributes deviations broadly across customers and time periods; (iii) a random perturbation heuristic applies stochastic adjustments to randomly selected customer–time pairs; (iv) a peak-time heuristic focuses deviations on randomly chosen peak periods; and (v) a mixed heuristic probabilistically combines concentration and random allocation. Each heuristic generates multiple scenarios, which are then ranked by temporal concentration, and only the top-ranked scenarios are retained as candidates. This multi-heuristic generation provides a diverse set of challenging demand realizations that guide the master problem toward robust first-stage decisions without requiring exact bilevel optimization at every iteration.

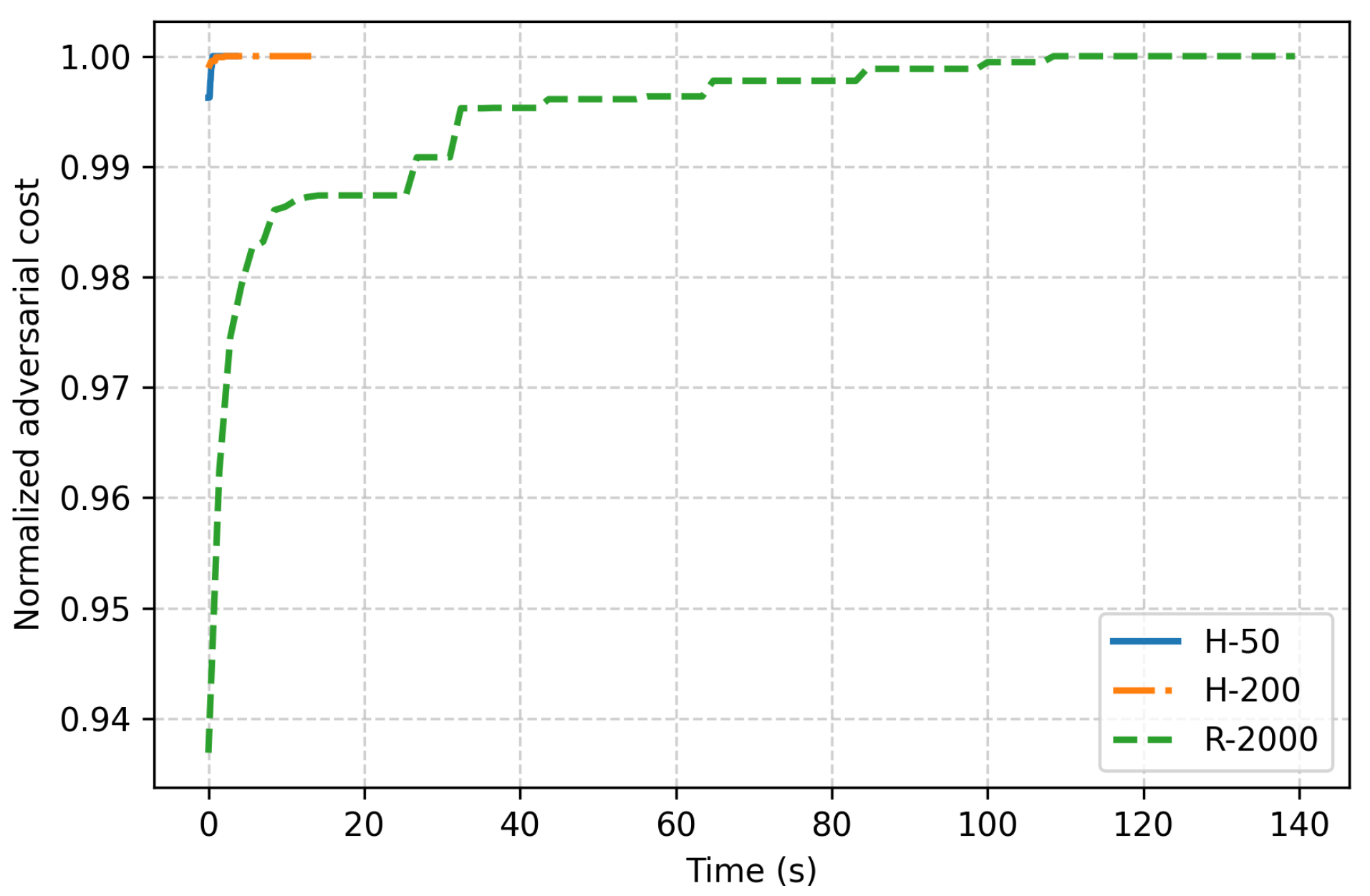

Figure 2 shows the average convergence of the proposed multi-heuristic scenario generation against a random sampling baseline. H-50 and H-200 correspond to heuristic evaluations with up to 50 and 200 generated scenarios, respectively, while R-2000 denotes random generation of 2000 feasible scenarios satisfying the uncertainty budgets. The horizontal axis represents cumulative evaluation time (approximately proportional to the number of tested scenarios), and the vertical axis shows the normalized adversarial cost, i.e., the best value found so far relative to the final one. The heuristic methods (H-50 and H-200) rapidly reach near-saturation with few scenarios, whereas the random baseline (R-2000) converges much more slowly. The minor improvement from H-50 to H-200 further confirms that the heuristic search saturates early, efficiently identifying near-adversarial realizations with much less computational effort.

4.4. Optimality Cut in LBBD Framework

In our LBBD implementation, the optimality cut is constructed based on the observation that the decision

z is fully determined by the assignment vector

u. In other words, if two solutions share the same

u, they will necessarily yield the same

z. This property allows the algorithm to avoid redundant evaluations of the master problem for identical

u values. The set of concentrated scenarios generated by the multi-heuristic procedure is denoted by

. For a given

, the adverse second-stage cost

is obtained as follows:

A key innovation in our formulation is the introduction of binary variables , which decompose each integer into multiple binary components. Without this decomposition, being an integer variable would prevent the direct construction of Benders cuts. By splitting into , we can explicitly identify inactive assignments in the current solution and formulate the cut.

Let

denote the set of indices

such that

in the current solution. To derive the optimality cut, we first note that activating any previously inactive

could potentially reduce the master problem’s objective variable

(representing the evaluated adverse second-stage cost) by an amount up to

per newly activated unit while leaving

bounded from below by

if all inactive assignments remain zero. Based on this observation, an intermediate inequality can be written as follows:

which explicitly accounts for the effect of previously inactive assignments on the lower bound of

.

Rearranging the terms of the above inequality leads to the final form of the Benders optimality cut:

This cut guarantees that

is at least as large as the evaluated adverse second-stage cost

. At the same time, it allows a reduction in

if one or more previously inactive assignments

become active, preserving the flexibility of the master problem to explore improved first-stage solutions.

In the callback, the procedure first retrieves the current values of

z and

u, constructs the binary decomposition

, identifies inactive assignments

, evaluates

over all candidate scenarios, and finally adds the lazy constraint (

29) to the master problem. Each evaluated solution is stored to prevent redundant evaluations in future iterations. This mechanism ensures convergence of the LBBD algorithm while maintaining computational efficiency through reuse of precomputed adverse scenarios.

5. Numerical Experiments

This section presents the numerical experiments designed to evaluate the proposed models, with a focus on cost efficiency, service reliability, and robustness under demand uncertainty. All experiments were implemented in Python 3.10 with CPLEX 22.1.1 and executed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Xeon E5-2695 v4 (2.10 GHz) CPU and 128 GB of RAM. The solver procedures for each model are configured with 4 threads, with a runtime limit of 600 s. All other CPLEX settings remain unchanged.

5.1. Experimental Procedures

This subsection presents the experimental methodology used to evaluate the proposed models, including instance generation, parameter settings, solution configuration, and performance evaluation metrics.

5.1.1. Instance Generation and Parameter Settings

A total of 108 instances were generated under three categories of parameter settings. The base instance set consists of 36 independent geometric instances, with 12 instances for each customer size , used for model comparison. For the sensitivity analyses, 12 instances with were further evaluated by varying the demand intensity , resulting in 36 -sensitivity instances, and by varying the modification probability , resulting in 36 -sensitivity instances.

For all instances, the number of depots was set to 20% of the number of customers, and depot capacities included a redundancy factor of 2.0. The total number of UAVs was set equal to the number of customers multiplied by a scaling factor of 1.0 for the base instances. The cost parameters were set as follows: the unit cost of deploying a UAV was , the penalty for each unit of unmet demand was , and the service cost was proportional to travel distance, calculated as . These parameter values are not based on empirical data but were reasonably assumed to represent realistic cost relationships among investment, service, and penalty components, ensuring a balanced comparison of strategic and operational decisions.

5.1.2. Solution Configuration

Each instance was solved using three models (deterministic, SAA, and robust), resulting in a total of 324 model runs. The deterministic and SAA models were solved directly using CPLEX. For the robust model, the uncertainty budgets and were calibrated using an SAA-based approach, and the resulting robust optimization problem was solved using the proposed LBBD algorithm. This experimental design enables a comprehensive evaluation of model performance under varying problem scales, demand intensities, and demand modification probabilities while explicitly considering cost trade-offs in first-stage investment and second-stage service operations.

Performance indicators recorded include total cost, service rate, and failed demand, with both mean and standard deviation reported across replications. The performance of each solution was evaluated through Monte Carlo simulation. In each run, customer demands were generated according to a Poisson distribution with mean . With probability , demand in a given time slot was set to zero and redistributed to other slots, capturing temporal demand shifts.

Given the first-stage decisions (depot openings and UAV assignments), a dynamic heuristic allocation algorithm was employed to allocate UAVs across depots and customers over multiple time slots. Compared with a simple greedy rule, this algorithm incorporates several enhancements: (i) temporal balancing of UAV availability across time slots, (ii) cost-aware prioritization based on distance and remaining UAV capacity, and (iii) adaptive response to demand modification.

In each time slot, customers are ranked by a dynamic priority index reflecting demand intensity and depot accessibility. UAVs are then assigned iteratively according to a depot score function that jointly considers current UAV availability and service cost. This heuristic provides a computationally efficient yet adaptive approximation of dynamic UAV scheduling, enabling an effective evaluation of service quality under uncertainty. Each configuration was simulated 500 times to capture variability.

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Uncertainty Budgets

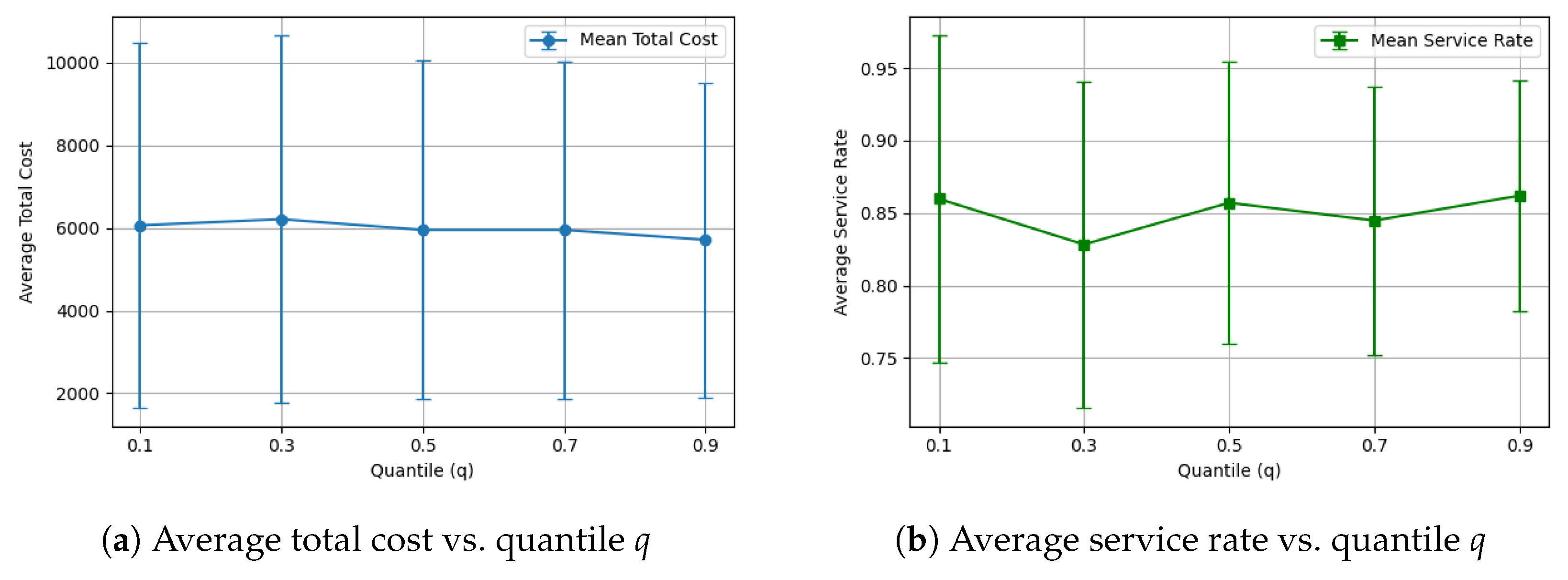

To calibrate the conservatism of the robust model, a sensitivity analysis was performed across quantile levels , where higher q values yield larger uncertainty budgets (, ) and thus stronger protection.

Figure 3 summarizes the averaged results over 3 representative instances with 50, 100, and 200 customers. As

q (and thus

and

) increases, the mean total cost rises slightly due to increased conservatism, while the service rate remains nearly stable, indicating diminishing returns in reliability. However, smaller instances stabilize at moderate

q levels (

–

), whereas larger ones benefit from higher protection. For computational consistency across experiments,

was adopted as the baseline configuration.

5.3. Pre-Experimental Analysis: SAA Scenario Selection

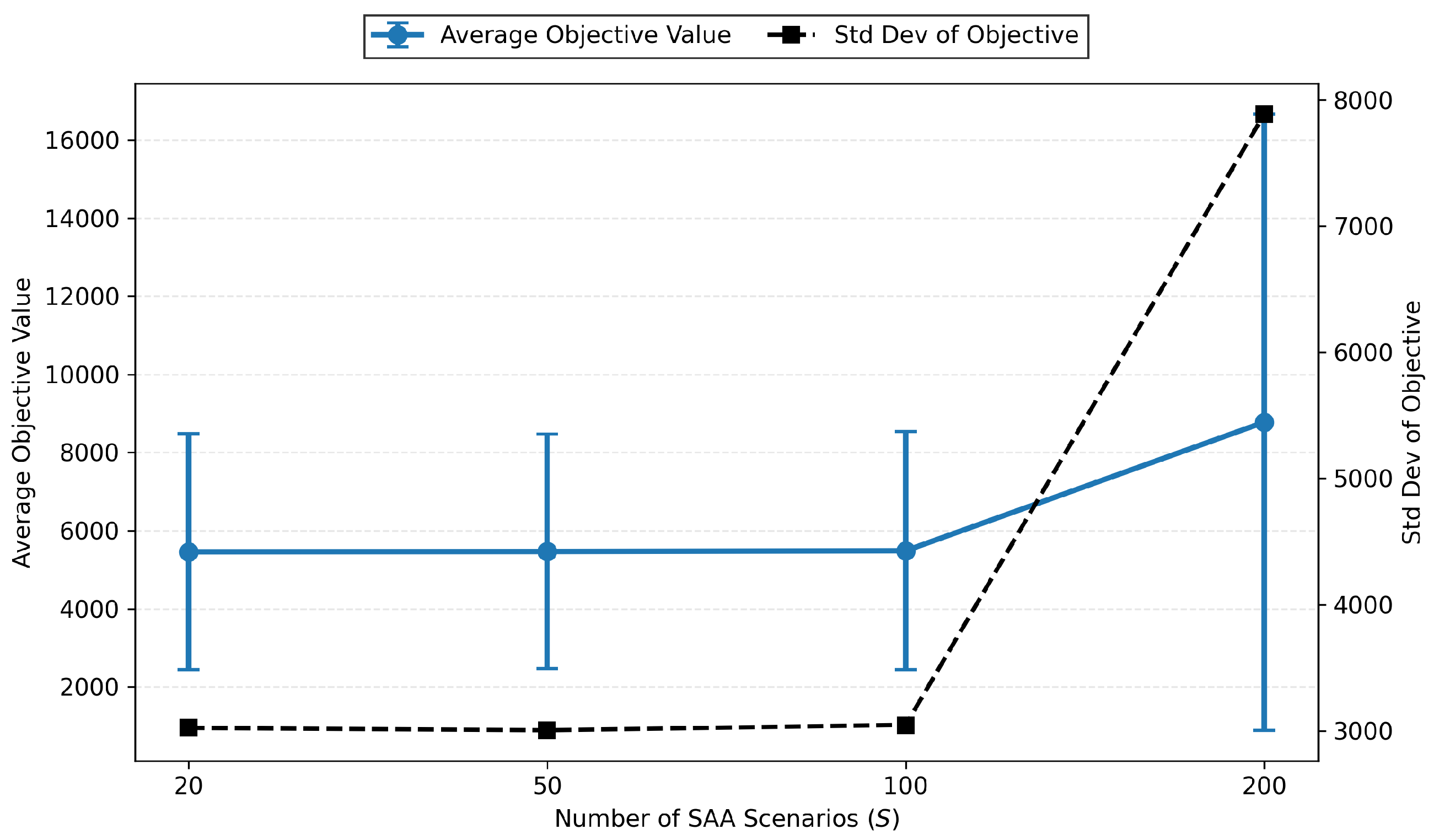

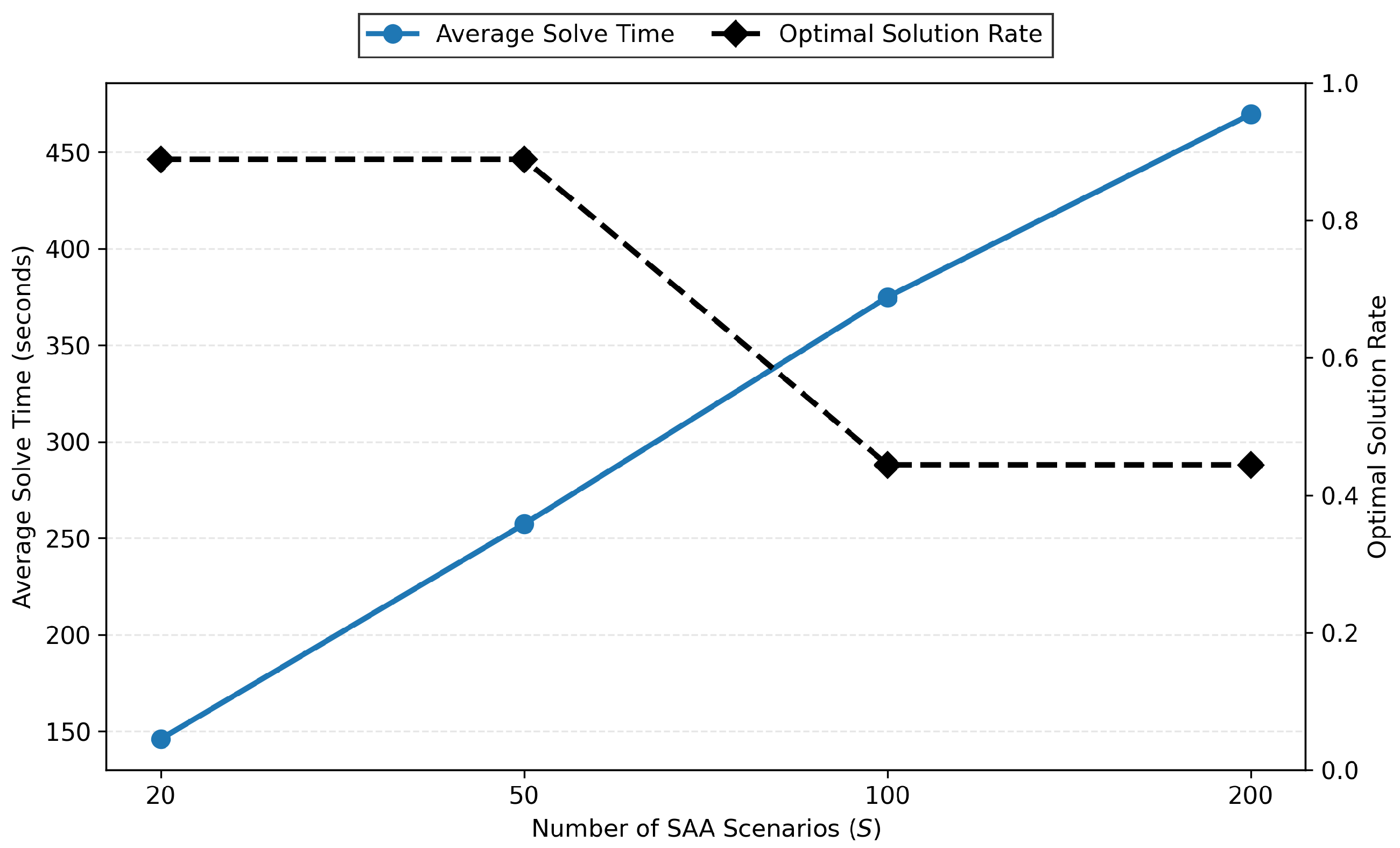

We first conducted a pre-experimental analysis to determine the number of scenarios

S used in the SAA model, as detailed in

Appendix A. Using 36 instances with different problem scales, we evaluated

. The results show that

provides the best trade-off between solution quality, computational efficiency, and solution reliability. Larger values of

S led to increased objective values and reduced reliability, likely due to higher model complexity. Consequently, we fix

for all subsequent experiments.

5.4. Results and Discussion

The numerical results from the 108 instances reveal nuanced insights into the performance of the three models: deterministic, SAA, and robust.

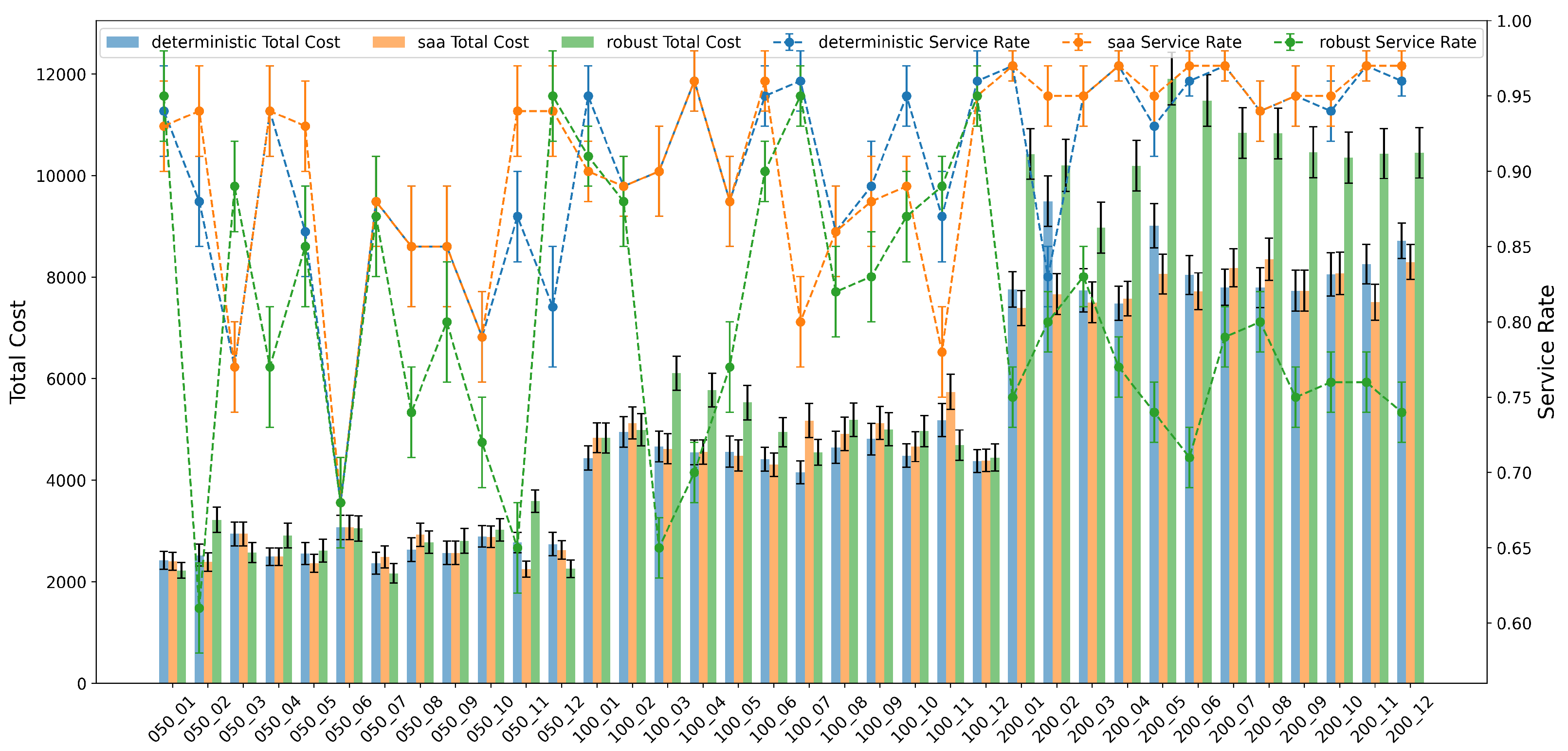

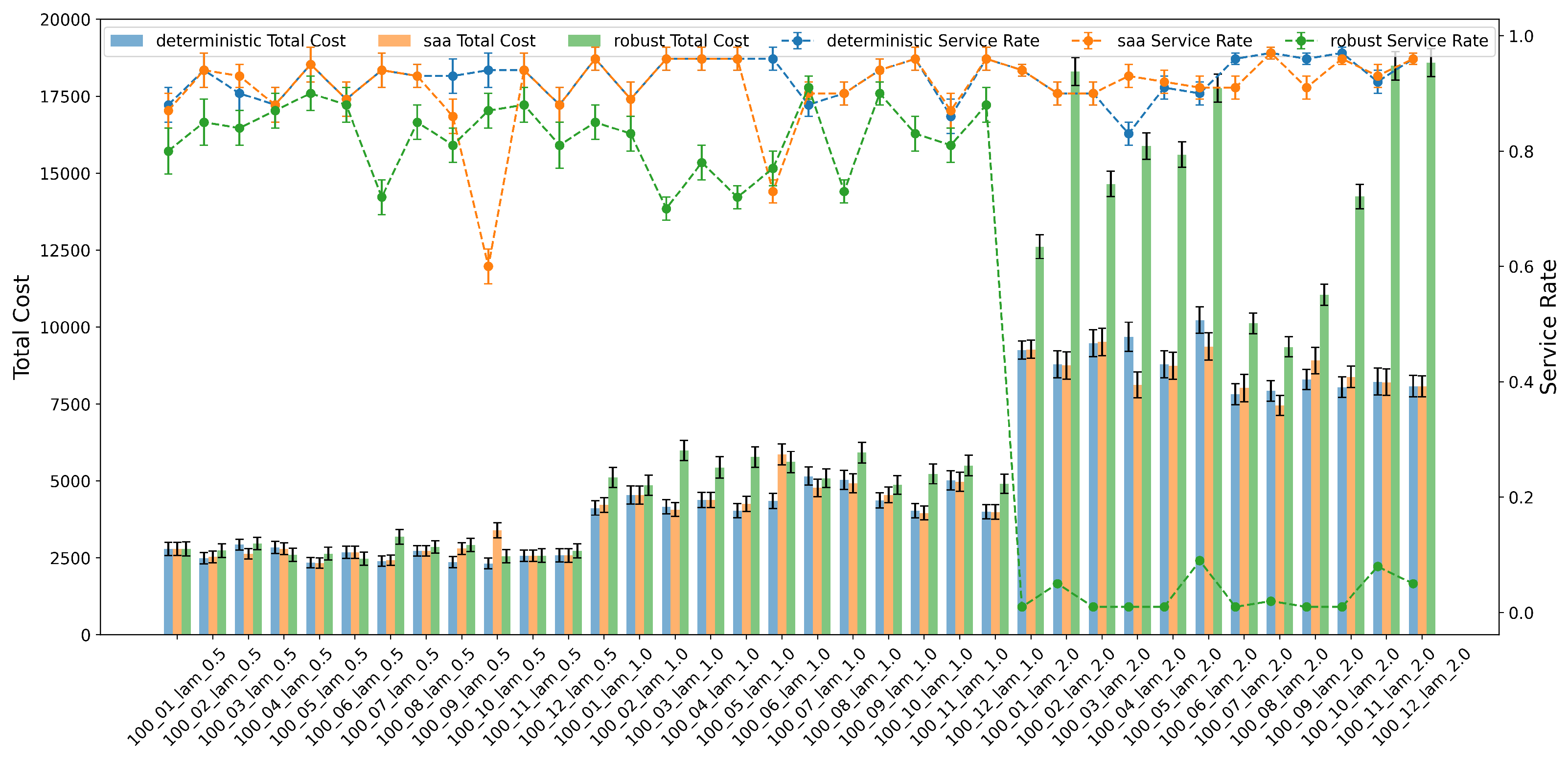

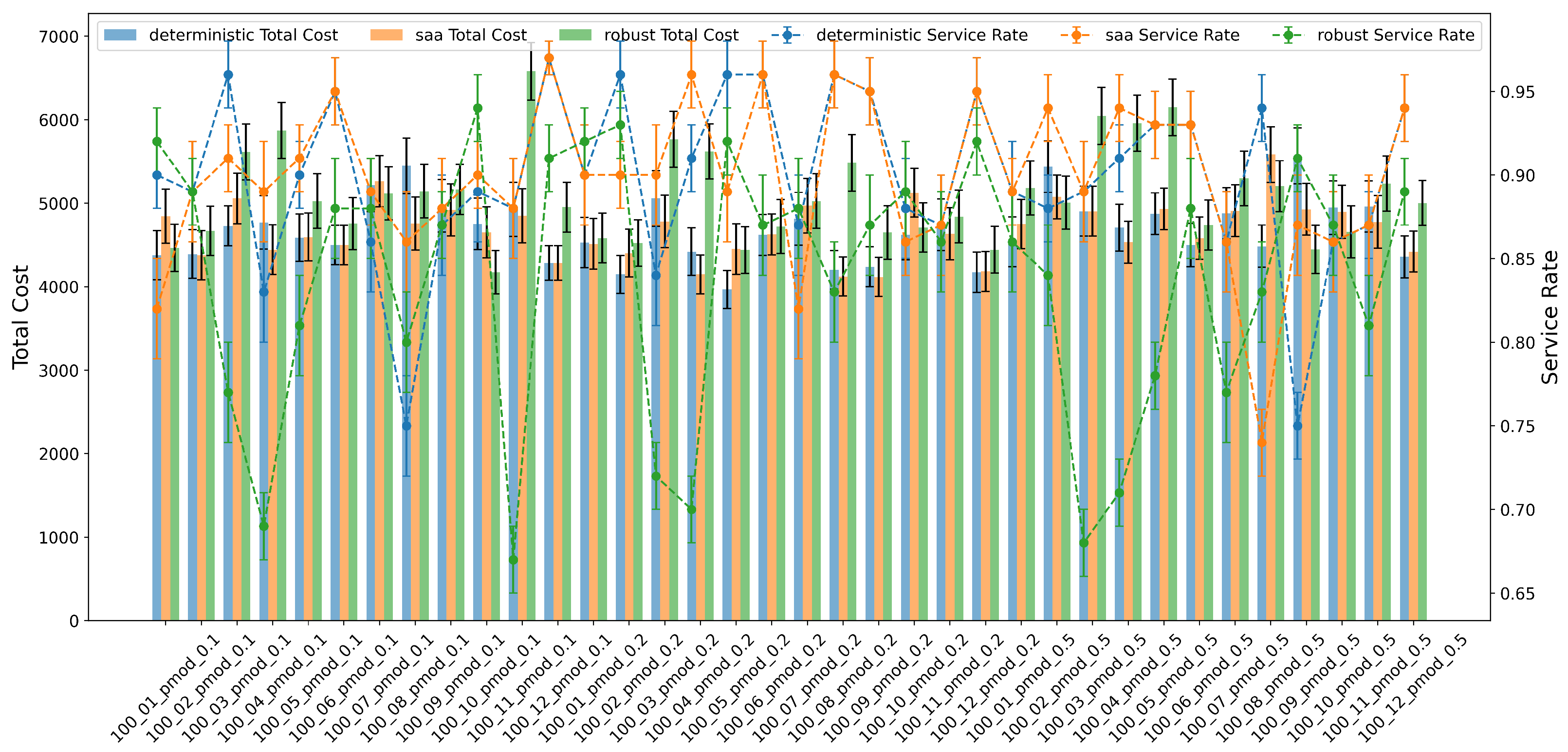

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 visualize aggregated trends across instances, while detailed numerical values for all 108 instances are provided in

Appendix A Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3.

To provide a quick reference for overall model performance,

Table 3 summarizes the average total cost and service rate (± standard deviation) across different instance categories. This allows readers to first grasp the general performance differences before examining detailed trends in the figures.

To gain deeper insights into model performance, we examine the results across different instance categories. First, from

Figure 4, we observe that for small instances (

), the robust model can occasionally achieve slightly lower total cost than deterministic and SAA models (e.g., instance_050_01), although its performance is inconsistent. For medium (

) and large (

) instances, the robust model often incurs higher total costs while only marginally improving service rates or reducing failed demand. This suggests that in practice, the robust solution may be overly conservative and sensitive to instance-specific characteristics. The deterministic model generally achieves lower first-stage cost but suffers from increased failed demand as customer size grows, whereas the SAA model provides moderate cost–service trade-offs.

Looking next at

Figure 5, we see that increasing the demand intensity from 0.5 to 2.0 dramatically raises total cost for the robust model, often exceeding deterministic and SAA solutions by large margins. Service rate stability is not guaranteed: in high-demand instances, the robust model can yield extremely poor service rates, suggesting that the predefined uncertainty budgets may be insufficiently calibrated or overly penalizing. Meanwhile, the SAA model maintains more balanced service rates, albeit at increased total cost, reflecting its reliance on sampled scenarios.

Finally,

Figure 6 illustrates that higher demand modification probabilities (

) generally increase total costs and failed demand across all models. The robust model handles small to moderate modifications more effectively than the deterministic model, but its performance deteriorates sharply for larger

values. In a few instances, the robust approach achieves higher service rates than SAA and deterministic models, highlighting potential gains if uncertainty budgets are more finely tuned.

Overall, the robust model exhibits high variance in performance. In some instances, it provides better service reliability with moderate costs, but in most cases, it is conservative, resulting in higher total costs and occasionally poor service rates. This may be attributed to the stochastic budget configuration within the robust model and limitations in the heuristic approach during the solving process. The SAA model generally offers balanced performance, whereas the deterministic model minimizes upfront cost at the expense of service reliability. These findings emphasize the trade-off between conservatism and cost-efficiency in practical UAV deployment under demand uncertainty.

The variability of the robust model primarily stems from the calibration of its uncertainty budgets

, which determine the level of conservatism. As confirmed by the sensitivity results (

Section 5.2), enlarging the uncertainty set through higher quantile levels

q increases protection but also inflates total costs, with diminishing improvement in service reliability. This explains the inconsistent performance observed across different instance scales, as smaller problems stabilize at moderate protection levels, while larger ones benefit from higher budgets due to accumulated demand uncertainty.

5.5. Implications for Practice and Research

This study provides implications for both methodological development in uncertainty-based optimization and the practical design of UAV delivery systems.

From a methodological standpoint, the results demonstrate the importance of integrating strategic and operational decisions when modeling logistics systems under uncertainty. The comparison among deterministic, stochastic (SAA), and robust formulations reveals that no single approach dominates across all conditions, underscoring the need to align model selection with the nature and variability of the decision environment. The proposed LBBD framework, combined with tailored Benders cuts, illustrates how decomposition-based algorithms can effectively handle complex two-stage decision structures while maintaining solution interpretability. In addition, the quantile-based calibration of the uncertainty budgets in the robust model offers a systematic and transparent way to control conservatism through a single quantile parameter q, enabling practical adjustment of robustness without excessive model complexity.

From a practical perspective, the findings suggest that decision makers can tune the uncertainty budgets to balance reliability and cost depending on their operational context and risk preferences. Conservative settings () are suited for mission-critical or emergency delivery operations where reliability is essential, whereas moderate protection levels (–) are sufficient for routine or cost-sensitive logistics. This flexibility allows the unified framework to support diverse reliability requirements and to serve as a decision-support tool for UAV-based delivery planning under demand uncertainty.

6. Conclusions

This study develops a unified two-stage framework for UAV-based delivery, integrating strategic depot location and UAV fleet allocation with operational assignment under stochastic, dynamically modified demand. Three mathematic models—deterministic, SAA, and robust—are formulated to reflect different risk attitudes. The deterministic and SAA models are solved via standard MIP formulations, while the robust model is solved using LBBD combined with a multi-heuristic adversarial scenario generator.

Computational experiments were conducted on 108 instances, combined with simulations to reveal trade-offs among cost-effectiveness, service success rate, and robustness. Results indicate that the deterministic model achieves satisfactory solutions at low computational cost when random fluctuations are insignificant; the robust model performs best in some instances but less consistently overall, attributed to limitations in the designed robust approach and the calibration of uncertainty budgets; whereas the SAA model achieves balanced performance at moderate computational cost, demonstrating overall superiority.

Overall, the proposed framework offers methodological contributions and practical guidance for designing resilient UAV delivery systems. The findings emphasize the value of jointly integrating strategic and operational decisions and provide managerial insights for balancing cost efficiency and service reliability in uncertain delivery environments.

Future research could further enhance the framework by relaxing simplifying assumptions and enriching operational realism. Incorporating multi-customer routing, heterogeneous UAV fleets, and multimodal coordination with ground vehicles would improve efficiency and applicability. Considering contextual factors such as weather, cargo characteristics, and service priorities could yield more realistic modeling of UAV logistics. Finally, adaptive or data-driven calibration of uncertainty budgets based on instance scale and variability may further enhance model flexibility and robustness.

Author Contributions

X.Z.: conceptualization, methodology, software, writing, supervision, funding acquisition. S.Q.: methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing. Y.Z.: formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing, supervision, project administration. J.H.: conceptualization, investigation, resources, supervision, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 12371310] and the Sino-German Mobility Program [grant number M-0310].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the

Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Pre-Experimental Analysis of SAA Scenario Sizes

To determine the appropriate number of scenarios S for the SAA method, we conducted a pre-experimental analysis using 36 test instances. Four scenario sizes were evaluated: . All SAA models were solved using CPLEX 22.1.1 with a time limit of 600 s and 4 threads. The analysis ensures that our choice of S is data-driven, reproducible, and justified by both solution quality and computational reliability.

Appendix A.1. Instance Generation and Scenario Pool Construction

We generated 36 test instances with varying problem scales (number of customers: 50, 100, 200). For each instance, a scenario pool of demand scenarios was generated to ensure statistical richness. Each scenario was constructed as follows:

Nominal demand: For each customer and time slot, demand was sampled from a Poisson distribution with parameter , reflecting stochastic customer requests.

Demand modification: To model demand uncertainty and temporal shifts, we applied a modification process: with probability , a customer’s demand in a time slot was set to zero, and this demand was randomly reallocated to other time slots.

Appendix A.2. Training and Evaluation Data Split

For each instance and each SAA configuration (), we performed the following data split:

Training scenarios: S scenarios were randomly sampled from the 500-scenario pool to form the SAA training set used in the optimization model.

Evaluation scenarios: An independent set of 100 scenarios (disjoint from training) was used for out-of-sample evaluation to assess solution robustness.

This ensures that the training and evaluation sets are independent, preventing overfitting and enabling reliable performance assessment.

Appendix A.3. Results and Final Selection

Figure A1 and

Figure A2 summarize the pre-experimental results, which provide visual summaries of the convergence and reliability analysis. The results show that

yields the lowest average objective value (9815.52), while larger

S values lead to higher objective values—increasing to 18,568.15 at

. This counterintuitive result is attributed to increased model complexity, which hinders the solver from finding high-quality feasible solutions within the time limit. Additionally, the optimal solution rate drops from 66.7% at

and

to only 33.3% at

and

, indicating reduced solution reliability for larger

S values.

The results show that achieves a low average objective value of 5457.40, with further increases in S leading to only marginal improvements—reaching 5464.51 at and 5484.00 at . However, when S increases to 200, the objective value rises sharply to 8775.50, indicating a significant degradation in solution quality. This deterioration is likely due to increased model complexity, which hampers the solver’s ability to converge to high-quality solutions within the time limit.

Moreover, the rate of obtaining optimal solutions remains high at 88.9% for both and , but it drops sharply to 44.4% for and , reflecting a notable decline in solution reliability as the sample size grows.

Based on these findings, we selected for all main experiments, as it provides the best balance of solution quality, computational efficiency, and solution reliability.

Figure A1.

Average objective value and its standard deviation across different SAA scenario sizes.

Figure A1.

Average objective value and its standard deviation across different SAA scenario sizes.

Figure A2.

Average solve time and optimal solution rate for different scenario sizes.

Figure A2.

Average solve time and optimal solution rate for different scenario sizes.

Appendix B. Detailed Numerical Results

Appendix B.1. Effect of Number of Customers

Table A1.

Detailed results for varying numbers of customers.

Table A1.

Detailed results for varying numbers of customers.

| Instance | Det. Cost | Det. SR | Det. FD | SAA Cost | SAA SR | SAA FD | Robust Cost | Robust SR | Robust FD |

|---|

| instance_050_01 | 2424.17 | 0.94 | 25.47 | 2403.80 | 0.93 | 27.45 | 2226.18 | 0.95 | 19.50 |

| instance_050_02 | 2524.35 | 0.88 | 49.20 | 2390.02 | 0.94 | 25.39 | 3220.39 | 0.61 | 152.02 |

| instance_050_03 | 2944.45 | 0.77 | 91.73 | 2944.45 | 0.77 | 91.73 | 2574.50 | 0.89 | 45.23 |

| instance_050_04 | 2493.95 | 0.94 | 22.24 | 2493.95 | 0.94 | 22.24 | 2912.83 | 0.77 | 89.82 |

| instance_050_05 | 2556.30 | 0.86 | 58.07 | 2364.38 | 0.93 | 26.88 | 2611.73 | 0.85 | 62.42 |

| instance_050_06 | 3072.09 | 0.68 | 129.51 | 3072.09 | 0.68 | 129.51 | 3049.34 | 0.68 | 128.25 |

| instance_050_07 | 2366.75 | 0.88 | 48.41 | 2490.32 | 0.88 | 48.33 | 2167.06 | 0.87 | 39.90 |

| instance_050_08 | 2633.20 | 0.85 | 61.31 | 2927.57 | 0.85 | 61.96 | 2781.12 | 0.74 | 92.88 |

| instance_050_09 | 2570.40 | 0.85 | 61.29 | 2570.40 | 0.85 | 61.29 | 2809.04 | 0.80 | 82.49 |

| instance_050_10 | 2892.58 | 0.79 | 81.37 | 2885.08 | 0.79 | 84.40 | 3024.35 | 0.72 | 106.23 |

| instance_050_11 | 2773.08 | 0.87 | 50.23 | 2248.77 | 0.94 | 20.46 | 3589.88 | 0.65 | 139.55 |

| instance_050_12 | 2743.91 | 0.81 | 75.64 | 2624.18 | 0.94 | 24.85 | 2258.71 | 0.95 | 18.37 |

| instance_100_01 | 4437.32 | 0.95 | 36.95 | 4839.22 | 0.90 | 83.03 | 4832.96 | 0.91 | 74.82 |

| instance_100_02 | 4951.24 | 0.89 | 91.80 | 5127.96 | 0.89 | 89.01 | 4994.71 | 0.88 | 94.10 |

| instance_100_03 | 4665.92 | 0.90 | 80.19 | 4619.72 | 0.90 | 80.56 | 6109.46 | 0.65 | 279.70 |

| instance_100_04 | 4548.65 | 0.96 | 33.50 | 4555.88 | 0.96 | 34.04 | 5772.92 | 0.70 | 239.72 |

| instance_100_05 | 4564.35 | 0.88 | 93.34 | 4488.16 | 0.88 | 93.37 | 5529.85 | 0.77 | 183.93 |

| instance_100_06 | 4413.37 | 0.95 | 37.34 | 4305.86 | 0.96 | 34.45 | 4946.49 | 0.90 | 79.50 |

| instance_100_07 | 4155.72 | 0.96 | 33.24 | 5174.72 | 0.80 | 160.40 | 4551.76 | 0.95 | 41.81 |

| instance_100_08 | 4644.09 | 0.86 | 114.70 | 4914.55 | 0.86 | 114.64 | 5190.25 | 0.82 | 144.98 |

| instance_100_09 | 4812.28 | 0.89 | 87.63 | 5127.46 | 0.88 | 94.54 | 5006.06 | 0.83 | 137.07 |

| instance_100_10 | 4486.10 | 0.95 | 39.63 | 4660.00 | 0.89 | 91.15 | 4968.03 | 0.87 | 101.71 |

| instance_100_11 | 5181.94 | 0.87 | 101.10 | 5740.78 | 0.78 | 176.16 | 4694.00 | 0.89 | 88.97 |

| instance_100_12 | 4378.29 | 0.96 | 35.96 | 4393.25 | 0.95 | 36.85 | 4447.59 | 0.95 | 43.78 |

| instance_200_01 | 7757.95 | 0.97 | 52.89 | 7390.47 | 0.97 | 48.59 | 10,424.40 | 0.75 | 407.24 |

| instance_200_02 | 9496.96 | 0.83 | 271.90 | 7661.46 | 0.95 | 87.72 | 10,201.23 | 0.80 | 319.30 |

| instance_200_03 | 7742.01 | 0.95 | 80.33 | 7503.64 | 0.95 | 79.19 | 8974.46 | 0.83 | 279.49 |

| instance_200_04 | 7486.06 | 0.97 | 48.25 | 7577.84 | 0.97 | 47.74 | 10,195.11 | 0.77 | 375.24 |

| instance_200_05 | 9010.26 | 0.93 | 114.02 | 8060.77 | 0.95 | 77.06 | 11,909.81 | 0.74 | 423.24 |

| instance_200_06 | 8043.09 | 0.96 | 58.79 | 7719.56 | 0.97 | 48.29 | 11,475.78 | 0.71 | 471.24 |

| instance_200_07 | 7799.97 | 0.97 | 48.41 | 8182.15 | 0.97 | 48.91 | 10,839.66 | 0.79 | 343.46 |

| instance_200_08 | 7795.50 | 0.94 | 93.63 | 8351.31 | 0.94 | 93.56 | 10,828.59 | 0.80 | 327.55 |

| instance_200_09 | 7733.55 | 0.95 | 86.73 | 7733.55 | 0.95 | 86.73 | 10,459.32 | 0.75 | 399.24 |

| instance_200_10 | 8202.80 | 0.92 | 112.35 | 7817.03 | 0.93 | 90.20 | 11,342.73 | 0.73 | 441.55 |

| instance_200_11 | 8409.57 | 0.90 | 132.17 | 7821.72 | 0.91 | 112.26 | 11,412.91 | 0.72 | 451.30 |

| instance_200_12 | 8127.52 | 0.92 | 108.38 | 7891.63 | 0.92 | 101.84 | 11,195.73 | 0.74 | 389.18 |

Appendix B.2. Effect of Demand Intensity (λ)

Table A2.

Detailed results for varying demand intensity .

Table A2.

Detailed results for varying demand intensity .

| Instance | | Det. Cost | Det. SR | Det. FD | SAA Cost | SAA SR | SAA FD | Robust Cost | Robust SR | Robust FD |

|---|

| instance_100_01 | 0.5 | 2787.38 | 0.88 | 49.66 | 2790.78 | 0.87 | 51.08 | 2788.77 | 0.80 | 82.54 |

| instance_100_01 | 1.0 | 4117.77 | 0.96 | 33.81 | 4220.48 | 0.96 | 34.02 | 5108.24 | 0.85 | 122.17 |

| instance_100_01 | 2.0 | 9252.09 | 0.94 | 96.81 | 9276.41 | 0.94 | 96.59 | 12,610.15 | 0.01 | 1032.61 |

| instance_100_02 | 0.5 | 2487.34 | 0.94 | 24.36 | 2533.82 | 0.94 | 24.16 | 2732.41 | 0.85 | 60.98 |

| instance_100_02 | 1.0 | 4543.61 | 0.89 | 87.48 | 4533.08 | 0.89 | 87.55 | 4857.95 | 0.83 | 137.04 |

| instance_100_02 | 2.0 | 8788.47 | 0.90 | 162.16 | 8751.62 | 0.90 | 161.49 | 18,299.14 | 0.05 | 1473.62 |

| instance_100_03 | 0.5 | 2931.45 | 0.90 | 40.33 | 2626.99 | 0.93 | 27.95 | 2962.54 | 0.84 | 63.42 |

| instance_100_03 | 1.0 | 4161.76 | 0.96 | 32.15 | 4069.25 | 0.96 | 32.30 | 5987.23 | 0.70 | 239.72 |

| instance_100_03 | 2.0 | 9473.57 | 0.90 | 156.19 | 9515.68 | 0.90 | 163.17 | 14,648.36 | 0.01 | 1209.76 |

| instance_100_04 | 0.5 | 2838.53 | 0.88 | 48.25 | 2794.53 | 0.88 | 49.24 | 2593.47 | 0.87 | 54.33 |

| instance_100_04 | 1.0 | 4374.60 | 0.96 | 35.01 | 4374.60 | 0.96 | 35.01 | 5439.12 | 0.78 | 176.09 |

| instance_100_04 | 2.0 | 9685.95 | 0.83 | 266.94 | 8117.60 | 0.93 | 114.55 | 15,882.56 | 0.01 | 1296.98 |

| instance_100_05 | 0.5 | 2340.17 | 0.95 | 21.51 | 2330.47 | 0.95 | 21.66 | 2635.25 | 0.90 | 41.70 |

| instance_100_05 | 1.0 | 4031.51 | 0.96 | 33.44 | 4249.77 | 0.96 | 33.16 | 5776.37 | 0.72 | 223.74 |

| instance_100_05 | 2.0 | 8789.66 | 0.91 | 141.99 | 8743.01 | 0.92 | 135.60 | 15,598.49 | 0.01 | 1288.68 |

| instance_100_06 | 0.5 | 2682.50 | 0.89 | 46.01 | 2682.50 | 0.89 | 46.01 | 2470.16 | 0.88 | 49.07 |

| instance_100_06 | 1.0 | 4347.19 | 0.96 | 35.91 | 5863.28 | 0.73 | 215.79 | 5613.99 | 0.77 | 183.92 |

| instance_100_06 | 2.0 | 10221.49 | 0.90 | 166.37 | 9369.21 | 0.91 | 143.42 | 17,756.32 | 0.09 | 1409.24 |

| instance_100_07 | 0.5 | 2396.34 | 0.94 | 25.11 | 2421.58 | 0.94 | 25.31 | 3185.91 | 0.72 | 112.77 |

| instance_100_07 | 1.0 | 5152.36 | 0.88 | 98.88 | 4772.92 | 0.90 | 75.15 | 5083.69 | 0.91 | 73.77 |

| instance_100_07 | 2.0 | 7816.78 | 0.96 | 58.47 | 8015.37 | 0.91 | 145.58 | 10,119.79 | 0.01 | 825.05 |

| instance_100_08 | 0.5 | 2727.65 | 0.93 | 29.37 | 2727.65 | 0.93 | 29.37 | 2850.21 | 0.85 | 60.31 |

| instance_100_08 | 1.0 | 5029.95 | 0.90 | 81.96 | 4923.07 | 0.90 | 81.84 | 5917.31 | 0.73 | 215.77 |

| instance_100_08 | 2.0 | 7923.98 | 0.97 | 55.88 | 7455.20 | 0.97 | 52.69 | 9353.53 | 0.02 | 753.05 |

| instance_100_09 | 0.5 | 2362.67 | 0.93 | 27.73 | 2804.92 | 0.86 | 54.58 | 2921.71 | 0.81 | 75.98 |

| instance_100_09 | 1.0 | 4368.69 | 0.94 | 44.43 | 4543.27 | 0.94 | 45.25 | 4870.42 | 0.90 | 82.02 |

| instance_100_09 | 2.0 | 8294.42 | 0.96 | 63.14 | 8916.74 | 0.91 | 152.62 | 11,050.26 | 0.01 | 903.95 |

| instance_100_10 | 0.5 | 2316.70 | 0.94 | 23.30 | 3394.14 | 0.60 | 160.29 | 2554.46 | 0.87 | 54.46 |

| instance_100_10 | 1.0 | 4032.30 | 0.96 | 33.18 | 3956.43 | 0.96 | 33.21 | 5225.42 | 0.83 | 133.51 |

| instance_100_10 | 2.0 | 8044.48 | 0.97 | 56.14 | 8381.84 | 0.96 | 57.55 | 14,237.15 | 0.01 | 1176.54 |

| instance_100_11 | 0.5 | 2562.55 | 0.94 | 23.57 | 2562.55 | 0.94 | 23.57 | 2573.39 | 0.88 | 48.29 |

| instance_100_11 | 1.0 | 5014.05 | 0.86 | 109.51 | 4975.61 | 0.87 | 102.83 | 5496.68 | 0.81 | 152.84 |

| instance_100_11 | 2.0 | 8225.76 | 0.92 | 121.40 | 8209.05 | 0.93 | 119.86 | 18,487.40 | 0.08 | 1465.29 |

| instance_100_12 | 0.5 | 2579.76 | 0.88 | 48.62 | 2573.99 | 0.88 | 48.60 | 2729.68 | 0.81 | 75.01 |

| instance_100_12 | 1.0 | 3994.75 | 0.96 | 34.47 | 3991.04 | 0.96 | 34.44 | 4905.57 | 0.88 | 100.47 |

| instance_100_12 | 2.0 | 8078.93 | 0.96 | 63.12 | 8070.58 | 0.96 | 59.93 | 18,593.56 | 0.05 | 1505.32 |

Appendix B.3. Effect of Demand Modification Probability (pmod)

Table A3.

Detailed results for varying demand modification probability .

Table A3.

Detailed results for varying demand modification probability .

| Instance | | Det. Cost | Det. SR | Det. FD | SAA Cost | SAA SR | SAA FD | Robust Cost | Robust SR | Robust FD |

|---|

| instance_100_01 | 0.1 | 4378.95 | 0.90 | 80.79 | 4845.14 | 0.82 | 144.97 | 4466.53 | 0.92 | 67.80 |

| instance_100_01 | 0.2 | 4528.54 | 0.90 | 80.95 | 4513.38 | 0.90 | 80.94 | 4583.29 | 0.92 | 68.37 |

| instance_100_01 | 0.5 | 4538.02 | 0.89 | 89.44 | 4750.83 | 0.89 | 91.35 | 5183.61 | 0.86 | 114.32 |

| instance_100_02 | 0.1 | 4392.64 | 0.89 | 87.57 | 4376.96 | 0.89 | 87.75 | 4669.91 | 0.89 | 88.10 |

| instance_100_02 | 0.2 | 4147.89 | 0.96 | 34.32 | 4403.56 | 0.90 | 82.35 | 4524.19 | 0.93 | 57.21 |

| instance_100_02 | 0.5 | 5438.00 | 0.88 | 98.80 | 5075.74 | 0.94 | 49.78 | 5006.83 | 0.84 | 128.19 |

| instance_100_03 | 0.1 | 4727.88 | 0.96 | 32.16 | 5056.80 | 0.91 | 71.34 | 5614.82 | 0.77 | 184.23 |

| instance_100_03 | 0.2 | 5056.36 | 0.84 | 129.95 | 4782.74 | 0.90 | 81.33 | 5765.52 | 0.72 | 207.65 |

| instance_100_03 | 0.5 | 4904.31 | 0.89 | 89.05 | 4904.31 | 0.89 | 89.05 | 6045.68 | 0.68 | 256.12 |

| instance_100_04 | 0.1 | 4769.73 | 0.83 | 137.05 | 4444.74 | 0.89 | 87.25 | 5871.96 | 0.69 | 247.71 |

| instance_100_04 | 0.2 | 4421.09 | 0.91 | 69.38 | 4147.41 | 0.96 | 35.37 | 5622.73 | 0.70 | 239.73 |

| instance_100_04 | 0.5 | 4707.96 | 0.91 | 68.89 | 4533.18 | 0.94 | 47.61 | 5959.13 | 0.71 | 224.63 |

| instance_100_05 | 0.1 | 4587.99 | 0.90 | 78.09 | 4595.60 | 0.91 | 76.31 | 5025.62 | 0.81 | 153.18 |

| instance_100_05 | 0.2 | 3968.49 | 0.96 | 35.09 | 4451.68 | 0.89 | 87.46 | 4439.60 | 0.92 | 62.59 |

| instance_100_05 | 0.5 | 4875.18 | 0.93 | 58.58 | 4933.83 | 0.93 | 58.92 | 6147.75 | 0.78 | 180.17 |

| instance_100_06 | 0.1 | 4499.88 | 0.95 | 40.15 | 4498.83 | 0.95 | 37.96 | 4755.46 | 0.88 | 93.48 |

| instance_100_06 | 0.2 | 4621.96 | 0.96 | 35.52 | 4628.43 | 0.96 | 35.59 | 4722.48 | 0.87 | 107.92 |

| instance_100_06 | 0.5 | 4498.79 | 0.93 | 54.21 | 4580.81 | 0.93 | 53.46 | 4740.30 | 0.88 | 96.29 |

| instance_100_07 | 0.1 | 5219.87 | 0.86 | 109.58 | 5262.91 | 0.89 | 88.92 | 5118.72 | 0.88 | 93.43 |

| instance_100_07 | 0.2 | 4814.91 | 0.87 | 101.19 | 4970.93 | 0.82 | 145.28 | 5026.64 | 0.88 | 94.28 |

| instance_100_07 | 0.5 | 4879.70 | 0.86 | 114.59 | 4910.81 | 0.86 | 114.88 | 5296.54 | 0.77 | 186.00 |

| instance_100_08 | 0.1 | 5448.25 | 0.75 | 199.96 | 4757.16 | 0.86 | 115.06 | 5145.70 | 0.80 | 161.17 |

| instance_100_08 | 0.2 | 4202.15 | 0.96 | 35.52 | 4120.85 | 0.96 | 35.68 | 5482.70 | 0.83 | 139.03 |

| instance_100_08 | 0.5 | 4484.71 | 0.94 | 52.00 | 5583.06 | 0.74 | 209.33 | 5204.53 | 0.83 | 136.40 |

| instance_100_09 | 0.1 | 4969.03 | 0.87 | 101.94 | 4920.88 | 0.88 | 95.00 | 5166.04 | 0.87 | 108.40 |

| instance_100_09 | 0.2 | 4238.73 | 0.95 | 36.91 | 4116.79 | 0.95 | 38.07 | 4649.00 | 0.87 | 107.92 |

| instance_100_09 | 0.5 | 5569.26 | 0.75 | 201.35 | 4928.28 | 0.87 | 101.60 | 4446.93 | 0.91 | 73.02 |

| instance_100_10 | 0.1 | 4752.56 | 0.89 | 87.54 | 4651.47 | 0.90 | 80.67 | 4174.27 | 0.94 | 50.99 |

| instance_100_10 | 0.2 | 4620.20 | 0.88 | 96.87 | 5125.56 | 0.86 | 112.16 | 4710.58 | 0.89 | 88.14 |

| instance_100_10 | 0.5 | 4947.37 | 0.86 | 115.10 | 4897.99 | 0.86 | 108.17 | 4657.58 | 0.87 | 101.57 |

| instance_100_11 | 0.1 | 4926.83 | 0.88 | 100.25 | 4849.24 | 0.88 | 100.31 | 6578.72 | 0.67 | 263.72 |

| instance_100_11 | 0.2 | 4743.72 | 0.87 | 102.11 | 4635.07 | 0.87 | 101.42 | 4841.09 | 0.86 | 115.47 |

| instance_100_11 | 0.5 | 4961.24 | 0.87 | 98.62 | 4777.53 | 0.87 | 108.09 | 5234.81 | 0.81 | 156.03 |

| instance_100_12 | 0.1 | 4285.83 | 0.97 | 20.07 | 4285.83 | 0.97 | 20.07 | 4952.02 | 0.91 | 69.42 |

| instance_100_12 | 0.2 | 4173.52 | 0.95 | 37.28 | 4183.51 | 0.95 | 36.52 | 4441.97 | 0.92 | 65.61 |

| instance_100_12 | 0.5 | 4357.74 | 0.94 | 46.10 | 4422.03 | 0.94 | 50.91 | 5002.94 | 0.89 | 85.80 |

References

- Moradi, N.; Wang, C.; Mafakheri, F. Urban Air Mobility for Last-Mile Transportation: A Review. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1383–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, M.E.; Khodaparasti, S.; Perboli, G. Energy Efficient UAV-Based Last-Mile Delivery: A Tactical-Operational Model With Shared Depots and Non-Linear Energy Consumption. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 18560–18570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukkanci, O.; Campbell, J.F.; Kara, B.Y. Facility location decisions for drone delivery: A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 316, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibu, A.S.; Mahmoud, A.S.; Sheltami, T.R. A Review of Last-Mile Delivery Optimization: Strategies, Technologies, Drone Integration, and Future Trends. Drones 2025, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.C.; Lin, T.H.; Chang, S.H. A Decision System for Routing Problems and Rescheduling Issues Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, S.; Feng, O.; Tian, T.; Huang, Y.; Zhong, G. Research on Demand-Based Scheduling Scheme of Urban Low-Altitude Logistics UAVs. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Figliozzi, M. Maximum coverage capacitated facility location problem with range constrained drones. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 99, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N.; Yilmaz, O.; Deveci, M.; Lv, Z. Heuristics Based Optimization for Multidepot Drone Location and Routing Problem to Detect Post-Earthquake Damages. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulumba, T.; Diabat, A. Optimization of the drone-assisted pickup and delivery problem. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 181, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshref-Javadi, M.; Hemmati, A.; Winkenbach, M. A truck and drones model for last-mile delivery: A mathematical model and heuristic approach. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 80, 290–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouretas, K.; Kepaptsoglou, K. Stochastic Planning of Synergetic Conventional Vehicle and UAV Delivery Operations. Drones 2025, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lv, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Wu, Y. Designing two-level rescue depot location and dynamic rescue policies for unmanned vehicles. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 233, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, H.A.; Aloboud, E.; Alalwan, M.; Alhassan, S.; Alotaibi, E.; Bautista, G.; How, J.P. Autonomous task allocation for multi-UAV systems based on the locust elastic behavior. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 71, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, K.; Ansell, D.; Khan, W.; Yetgin, H. Analysis and Optimization of unmanned Aerial Vechicle in Swarms in Logistics: An Intelligent Delivery Platform. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 15804–15831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.C.; Raj, R. The multiple flying sidekicks traveling salesman problem: Parcel delivery with multiple drones. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 110, 368–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, A.; Sajadi, S.M.; Sadeq, A.M.; Narenji, M.; Eshaghi, M.; Jasemi, M. Enhancing unmanned aerial vehicles logistics for dynamic delivery: A hybrid non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II with Bayesian belief networks. Ann. Oper. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Fan, H.; Fan, H.; Ma, M. Time-dependent electric vehicle-drone routing problem for scheduled deliveries and on-demand pickups considering variable drone speeds and no-fly zones. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 182, 107141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kwak, J.H.; Oh, B.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, D. An Optimal Routing Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Sensors 2021, 21, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hu, C.; Zhu, J.; Wu, M.; Malekian, R. Stochastic Task Scheduling in UAV-Based Intelligent On-Demand Meal Delivery System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 13040–13054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, S.; Sundar, K.; Rathinam, S. A Two-Stage Approach for Routing Multiple Unmanned Aerial Vehicles with Stochastic Fuel Consumption. Sensors 2018, 18, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Boyles, S.D.; Unnikrishnan, A. Two-stage robust facility location problem with drones. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 137, 103563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Bi, X.; Li, G.; Dong, Z.; Xiao, N.; Zhao, A. Robust traveling salesman problem with multiple drones: Parcel delivery under uncertain navigation environments. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 168, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, J.; Ottosson, G. Logic-based Benders decomposition. Math. Program. 2003, 96, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanaei, V.; Luong, C.; Aleman, D.; Urbach, D. Collaborative Operating Room Planning and Scheduling. Informs J. Comput. 2017, 29, 558–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, S.; Lu, J.; Wang, S. Air Route Network Planning Method of Urban Low-Altitude Logistics UAV with Double-Layer Structure. Drones 2025, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, S.; Sung, I.; Nielsen, P.; Moon, I. Facility Location-Allocation Problem for Emergency Medical Service with Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 1465–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Ye, H.; Shi, Z. A Two-Stage Optimization Framework for UAV Fleet Sizing and Task Allocation in Emergency Logistics Using the GWO and CBBA. Drones 2025, 9, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorz, R.; Grzegorz, B.; Bogdan, D.; Zbigniew, B. Reactive Planning-Driven Approach to Online UAVs Mission Rerouting and Rescheduling. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibbotuwawa, A.; Bocewicz, G.; Zbigniew, B.; Nielsen, P. A Solution Approach for UAV Fleet Mission Planning in Changing Weather Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulumba, T.; Najy, W.; Diabat, A. The drone-assisted pickup and delivery problem: An adaptive large neighborhood search metaheuristic. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 161, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavarani, S.M.; Nejad, M.G.; Rismanchian, F.; Izbirak, G. Application of hierarchical facility location problem for optimization of a drone delivery system: A case study of Amazon prime air in the city of San Francisco. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 95, 3141–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Sim, M. The price of robustness. Oper. Res. 2004, 52, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).