A Hybrid Model Combining Signal Decomposition and Inverted Transformer for Accurate Power Transformer Load Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental Algorithm

2.1. Variational Mode Decomposition

2.1.1. Formulation of the Variational Problem

2.1.2. Solution to the Variational Problem

- (1)

- Initialize the mode functions , and ;

- (2)

- Update and in the positive frequency domain:

- (3)

- In the positive frequency domain, the Lagrange multiplier is updated as follows:where denotes the update step size parameter.

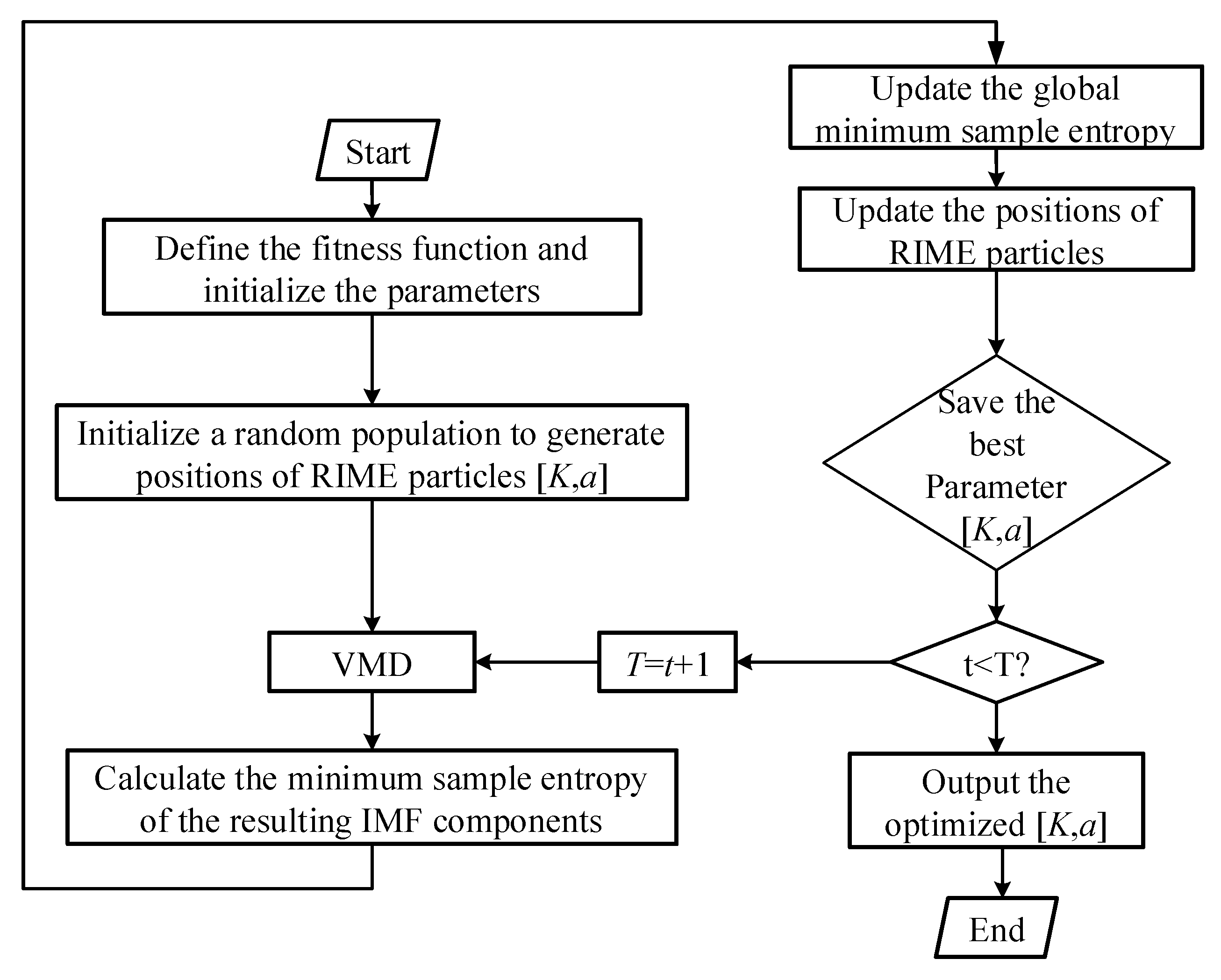

2.2. RIME

2.2.1. Soft Rime Search Mechanism

2.2.2. Hard Rime Search Mechanism

2.2.3. Proactive Greedy Selection Mechanism

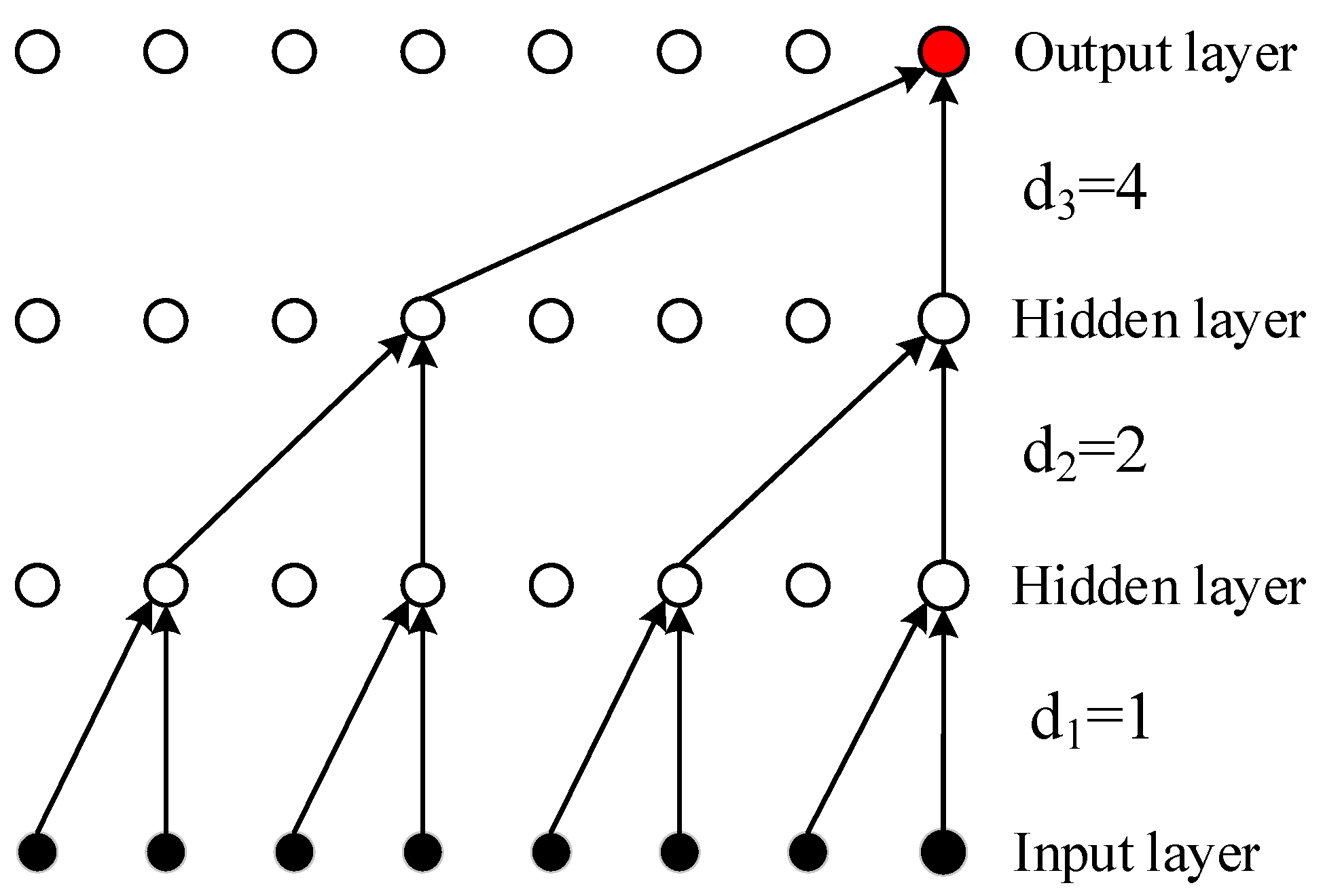

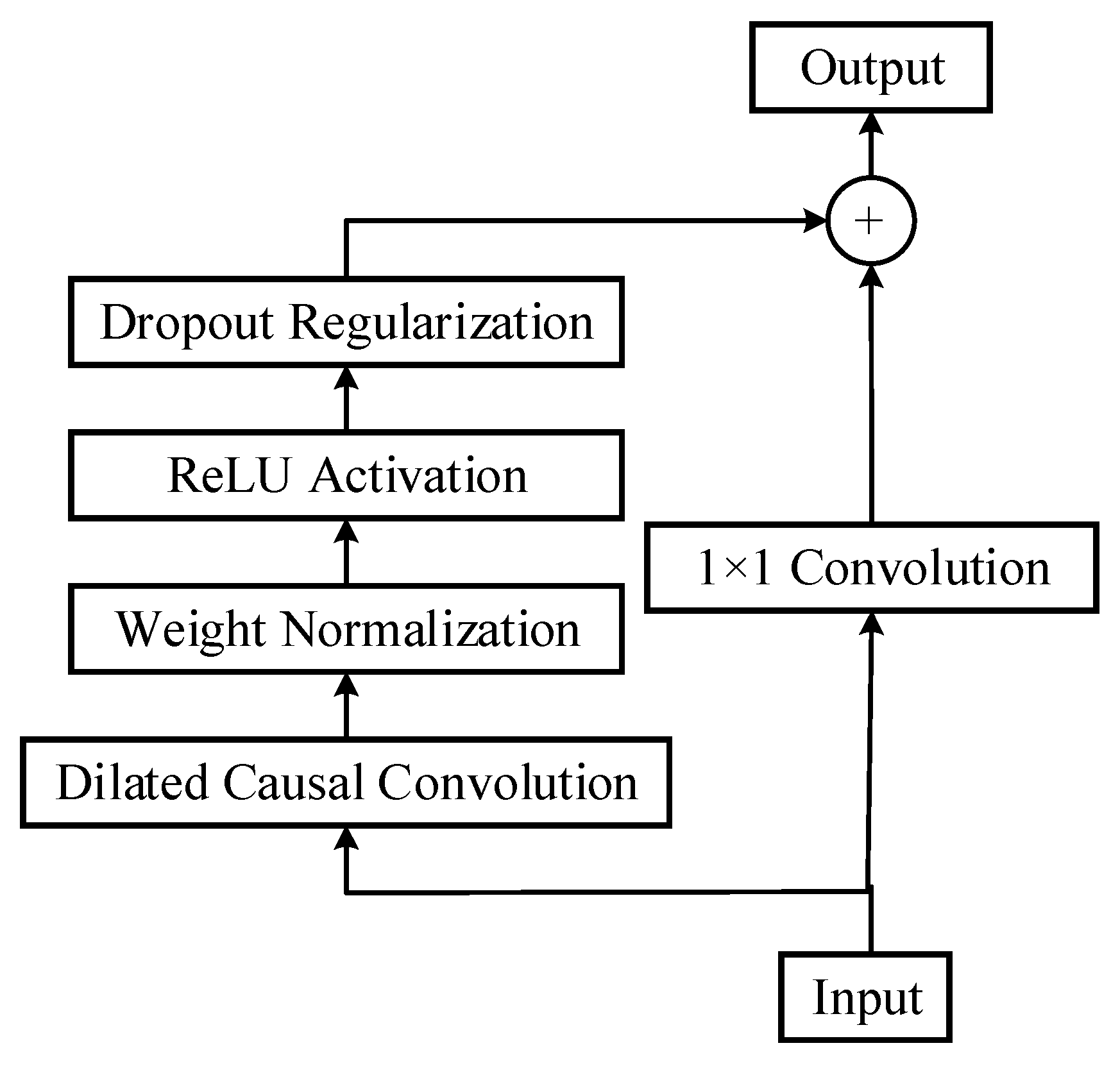

2.3. Temporal Convolutional Network Model

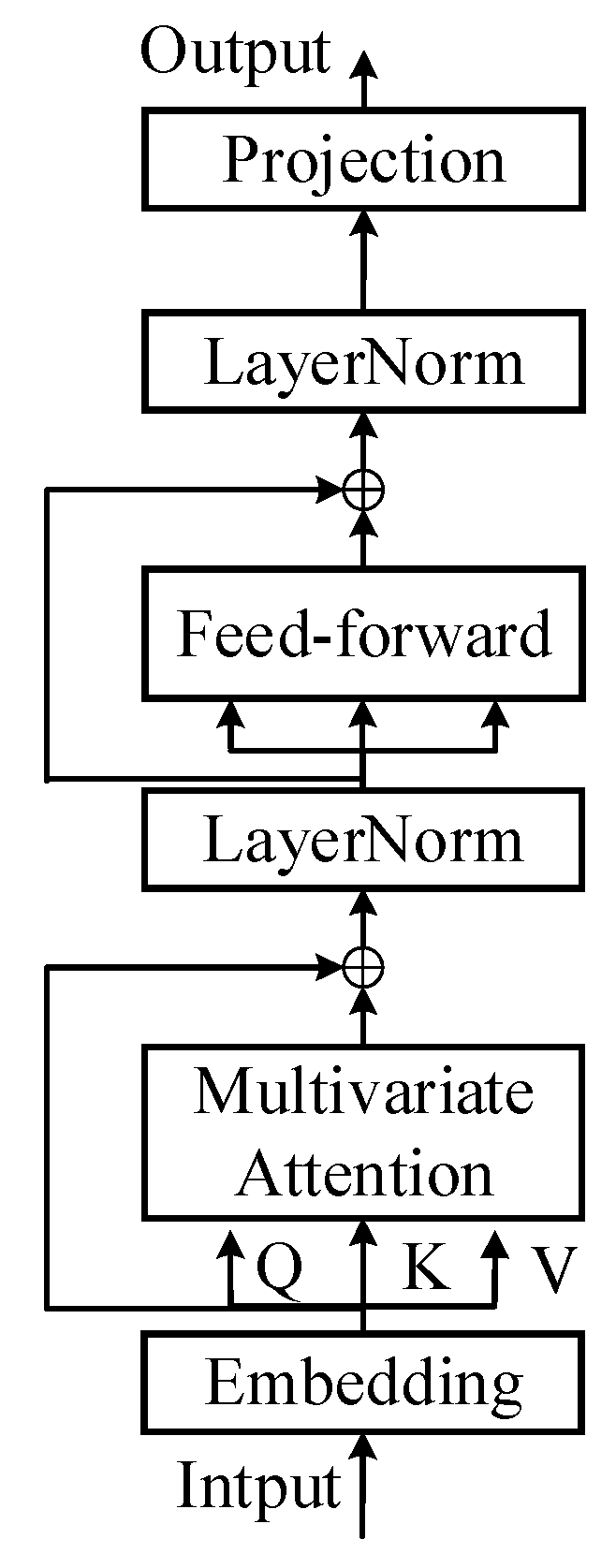

2.4. iTransformer Model

2.4.1. Embedding Layer

2.4.2. Multi-Head Attention Mechanism

2.4.3. Feed-Forward Network

2.4.4. Layer Normalization

2.4.5. Projection Layer

3. RIME-VMD-TCN-iTransformer Hybrid Model

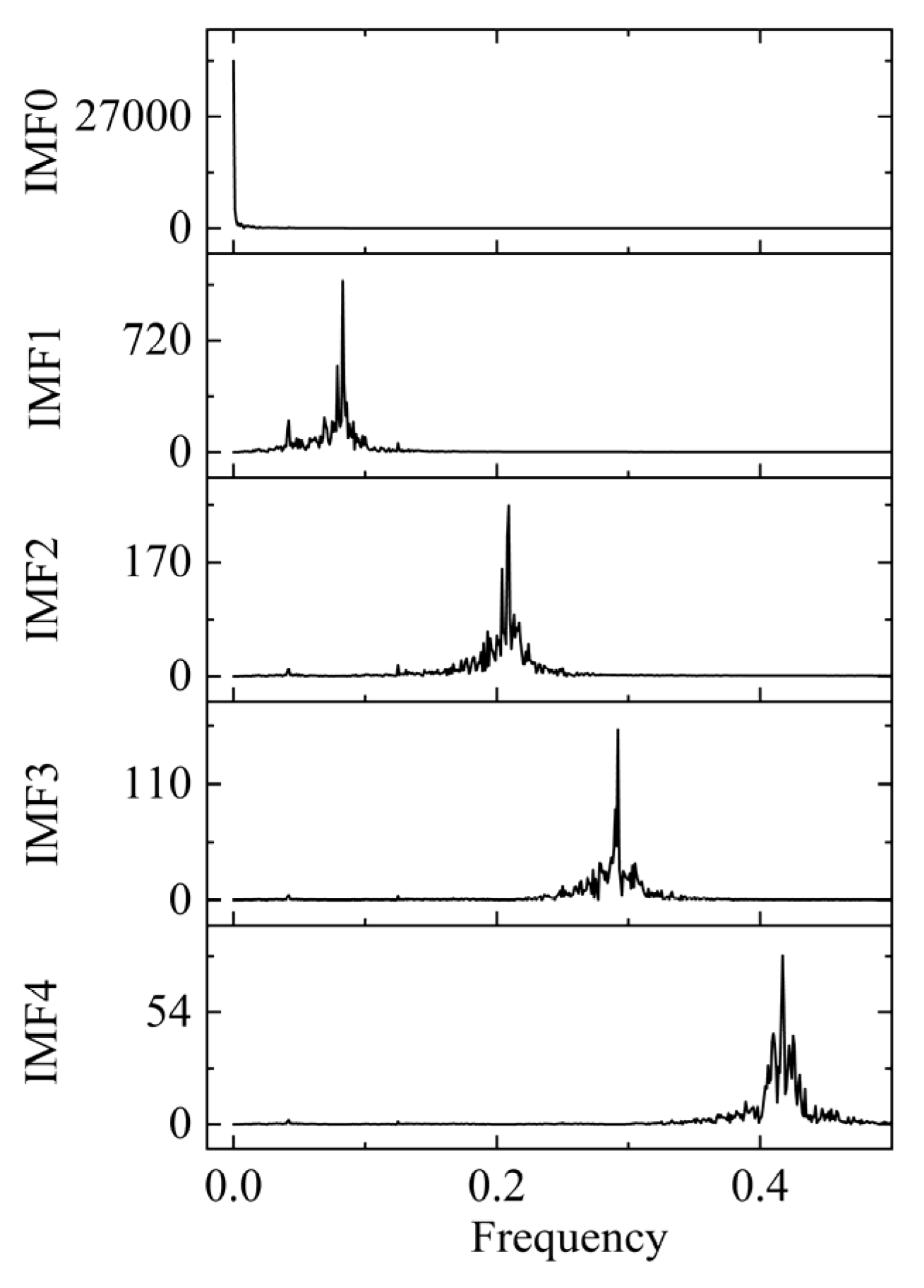

3.1. VMD Optimized by RIME

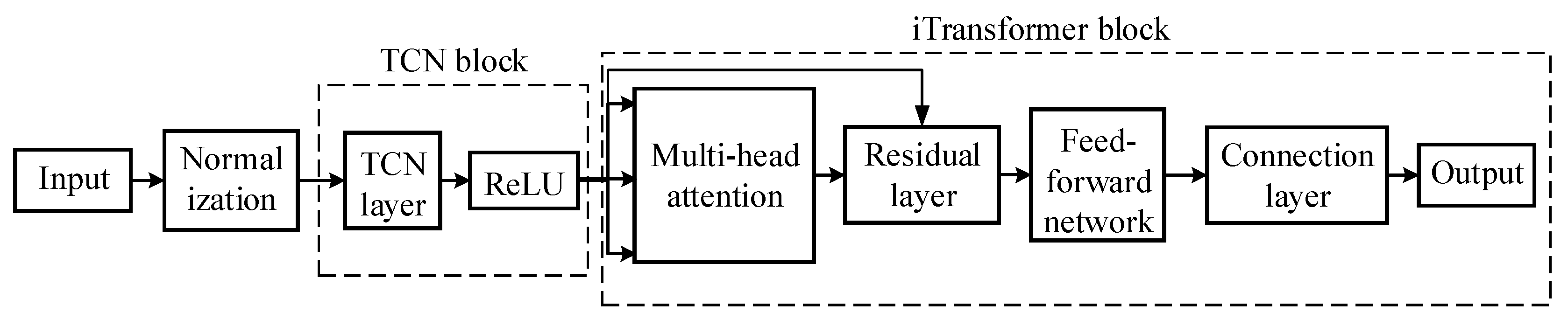

3.2. TCN-iTransformer Prediction Model

3.3. Prediction Process

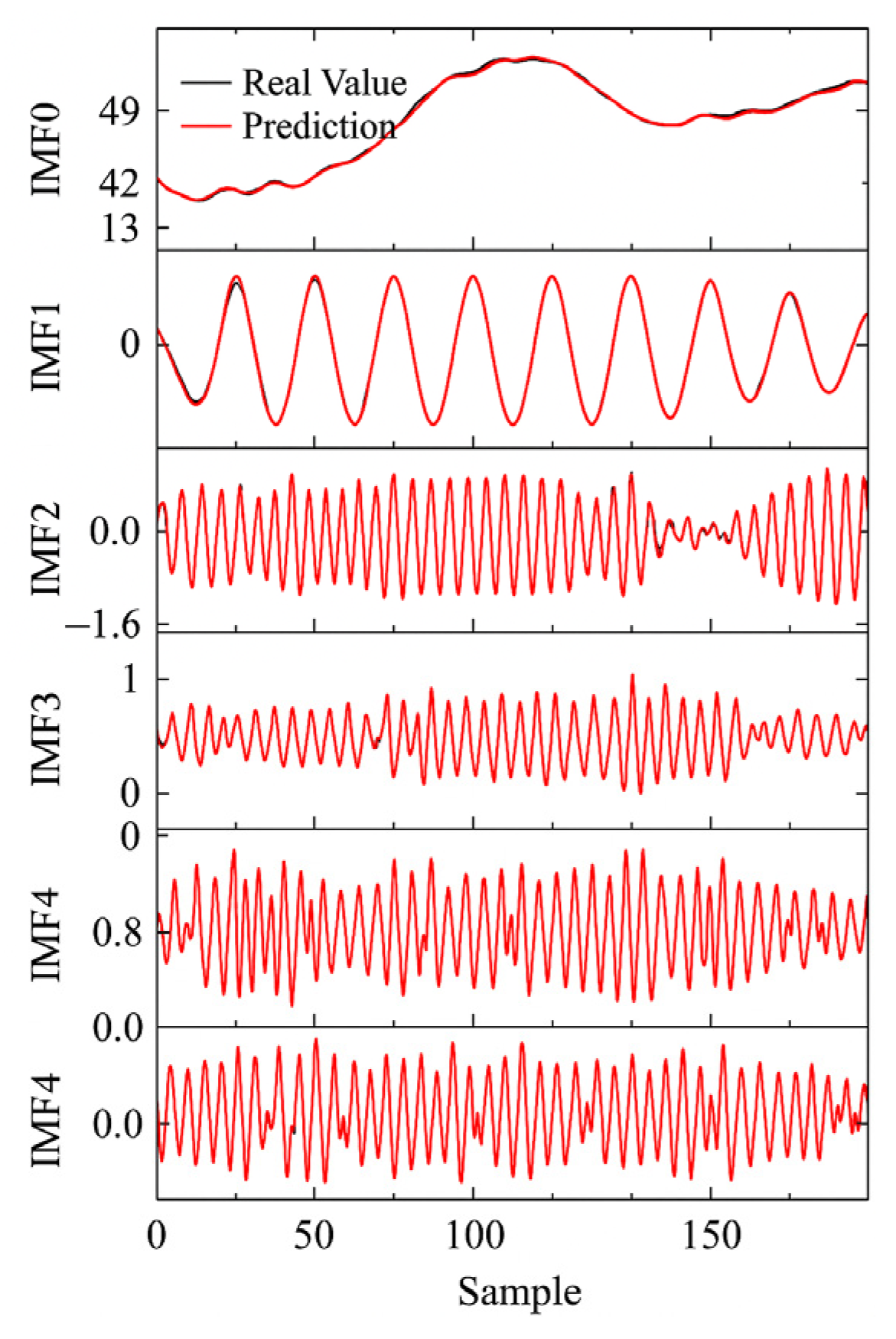

- Obtain IMFs via VMD optimized by RIME;

- Construct separate TCN-iTransformer prediction models for each IMFs, and update the network parameters using the adam optimizer;

- Reconstruct the prediction by aggregating the forecasting results of all IMFs.

3.4. Evaluation Parameters

4. Case Study

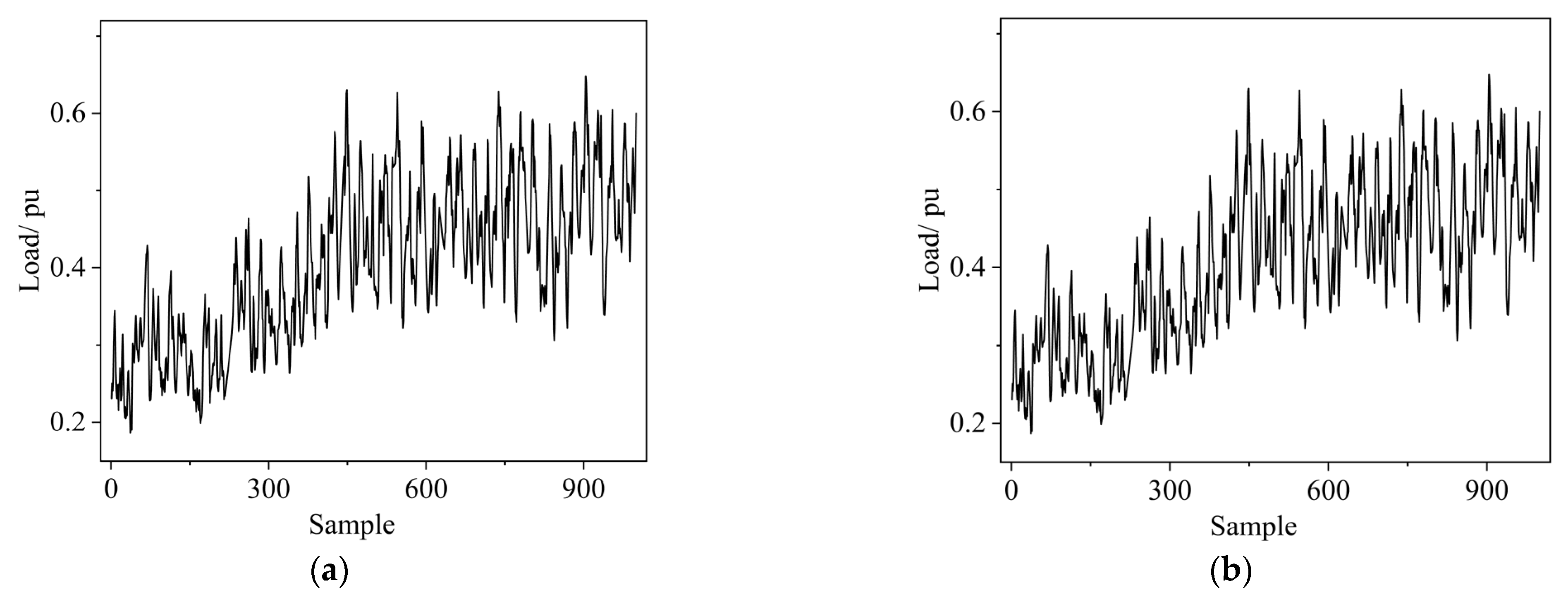

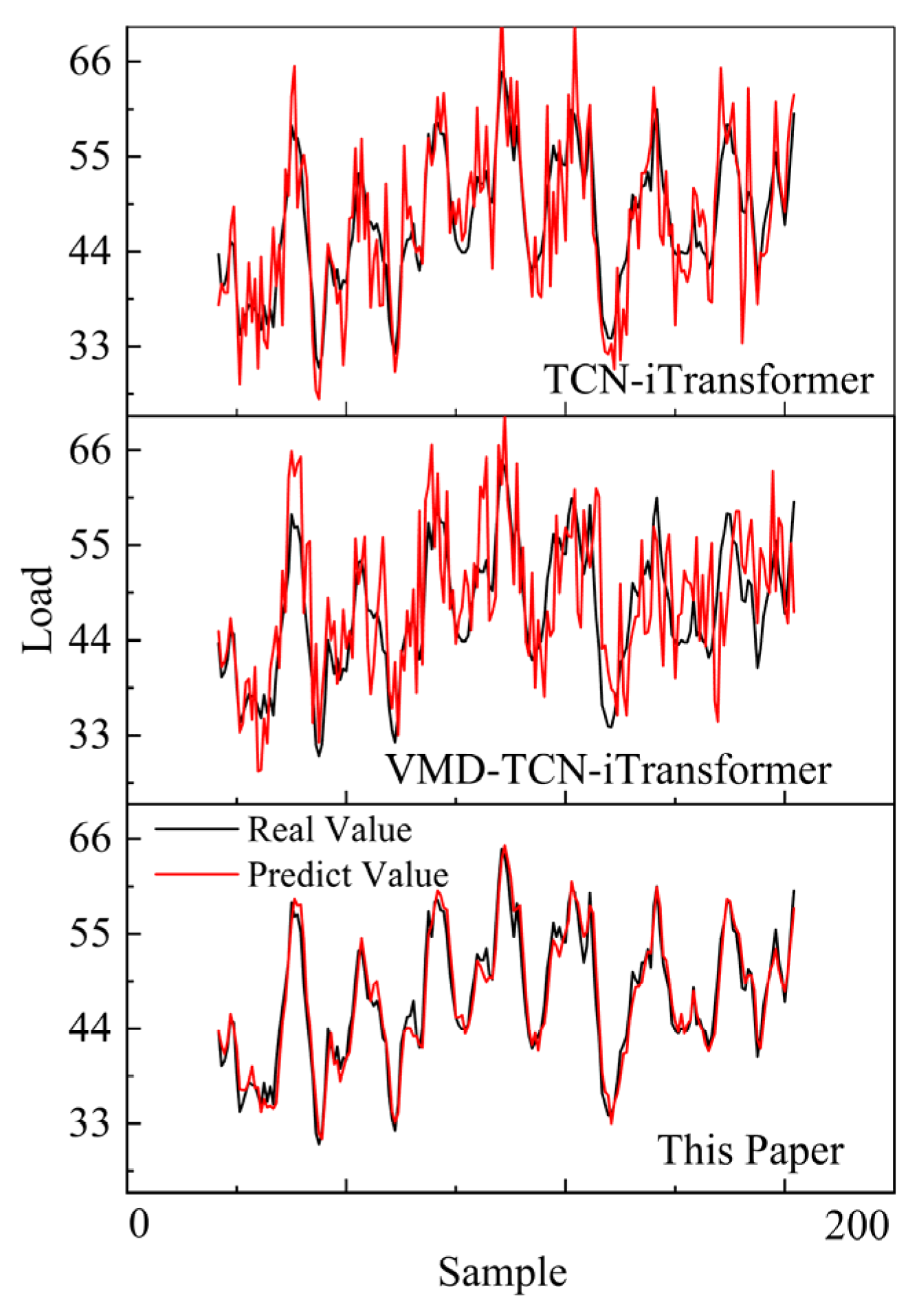

4.1. Prediction Results of the RIME-VMD-TCN-iTransformer Model

4.2. Generalization Ability Analysis

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Methodological Contribution: By integrating variational mode decomposition (VMD) with the randomized improved marine predators algorithm (RIME), the proposed framework effectively eliminates spectral aliasing and enhances the orderliness of intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). This improves the interpretability of decomposed components for load forecasting tasks.

- (2)

- Model Performance: The hybrid TCN-iTransformer model combines the advantages of convolutional layers for capturing short-term local dependencies and the inverted Transformer for modeling long-term global correlations. Experimental results on 1000 kV transformer datasets demonstrate that our model achieves superior accuracy compared with benchmark methods, with significantly reduced MAPE and RMSE values.

- (3)

- Practical Implications: The proposed model provides a reliable tool for predicting both abrupt fluctuations and long-term load trends, enabling power utilities to optimize transformer operation, reduce the risk of overload, and prevent potential failures. This is significant for ensuring the safety and stability of large-scale power systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Symbol/Abbreviation | Definition/Full Form | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Original time series | T: length of sequence | |

| D | Embedding dimension | |

| Q, K, V | Query, Key, Value matrices | Attention mechanism |

| W, b | Weight matrix and bias term | |

| Nonlinear activation function | e.g., GeLU | |

| K | Number of modes in VMD | |

| a | Penalty factor in VMD | |

| IMFk | k-th intrinsic mode function | |

| m | Embedding dimension for entropy | |

| r | Tolerance (threshold) | Sample entropy |

| Distance function | ||

| Matching degree | ||

| SEn | Sample entropy | |

| True/predicted load | ||

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error | |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error | |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination | |

| VMD | Variational Mode Decomposition | |

| RIME | Randomized Improved Marine Predators Algorithm | Optimization |

| TCN | Temporal Convolutional Network | |

| IMF | Intrinsic Mode Function | |

| DGA | Dissolved Gas Analysis | If mentioned |

| SGCC | State Grid Corporation of China |

References

- IEEE Std C57.91-2011; IEEE Guide for Loading Mineral-Oil-Immersed Transformers and Step-Voltage Regulators. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011.

- Biçen, Y.; Aras, F.; Kirkici, H. Lifetime estimation and monitoring of power transformer considering annual load factors. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2014, 21, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterakis, N.G.; Pappi, I.N.; Erdinc, O.; Godina, R.; Rodrigues, E.M.G.; Catalao, J.P.S. Consideration of the impacts of a smart neighborhood load on transformer aging. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 7, 2793–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Shao, C.; Dong, M.; Hu, B.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Y.; Xie, K.; Li, W. Modeling the aging-dependent reliability of transformers considering the individualized aging threshold and lifetime. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2022, 37, 4631–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.A.; Zainuddin, H.; Yahaya, M.S.; Azis, N.; Ibrahim, Z. Prerequisites for accelerated aging of transformer oil: A review. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Z.; Yin, F.; Qian, M. Transient-steady state vibration characteristics and influencing factors under no-load closing conditions of converter transformers. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 155, 109497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, F.; Chen, H.; Zhao, X.; Pan, P.; Xin, C.; Jiang, X. Enhancing economic efficiency: Analyzing transformer life-cycle costs in power grids. Energies 2024, 17, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, R.O.; Ibokette, A.I.; Ijiga, O.M.; Enyejo, L.A.; Ebiega, G.I.; Olumubo, O.M. The reliability assessment of power transformers. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 1149–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Qian, T.; Li, W.; Tang, W.; Xu, Z. An individualized adaptive distributed approach for fast energy-carbon coordination in transactive multi-community integrated energy systems considering power transformer loading capacity. Appl. Energy 2024, 375, 124189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Gao, J.; Zhu, C.; Deng, F. Short-term power load forecasting based on spatial-temporal dynamic graph and multi-scale transformer. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2025, 12, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; OTexts: Ontario, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Gong, X. Prediction of dissolved gas content in transformer oil using the improved SVR model. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhou, H.; Ding, X.; Zhang, R. Extreme learning machine for regression and multiclass classification. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. B 2012, 42, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Ren, Y.; Suganthan, P.N.; Amaratunga, G.A.J. Empirical mode decomposition based ensemble deep learning for load demand forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 54, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition: A noise-assisted data analysis method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2009, 1, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, T.; Ma, T.; Wang, H.; Yin, H. Ultra-short-term multi-step wind power forecasting based on ECBO-VMD-WKELM. Power Syst. Technol. 2021, 45, 3070–3080. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICNN, Perth, Australia, 9–12 June 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Huang, K.; Chen, J.; Bao, L.; Zhou, Q. Research on fault diagnosis method of on-load tap changer based on WSO-VMD sample entropy and SSA-SVM. J. Southwest Univ. 2024, 46, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Koltun, V.; Kolter, J.Z. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, P.C.; Minh, N.Q.; Tien, N.D.; Anh, T.T.Q. Short-term electricity load forecasting based on temporal fusion transformer model. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 106296–106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Long, M. iTransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12345. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.; Zhao, D.; Heidari, A.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. RIME: A physics-based optimization. Neurocomputing 2023, 532, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, J.S.; Moorman, J.R. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 278, H2039–H2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | MAPE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCN-iTransformer | 8.302% | 4.897 | 56.71% |

| VMD-TCN-iTransformer | 4.733% | 3.769 | 74.32% |

| This paper | 2.23% | 1.161 | 93.71% |

| Transformer Type | Evaluation Metrics | Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCN-iTransformer | VMD-TCN-iTransformer | This Paper | ||

| 2: 1000 kV | MAPE | 4.917% | 3.431% | 2.917% |

| RMSE | 9.483 | 5.548 | 3.983 | |

| R2 | 0.712 | 0.866 | 0.918 | |

| 1: 500 kV | MAPE | 3.923% | 3.012% | 1.923% |

| RMSE | 9.787 | 6.691 | 3.427 | |

| R2 | 0.698 | 0.612 | 0.927 | |

| 2: 500 kV | MAPE | 3.790% | 2.618% | 1.790% |

| RMSE | 10.237 | 9.326 | 6.237 | |

| R2 | 0.456 | 0.613 | 0.924 | |

| 1: 110 kV | MAPE | 5.191% | 3.789% | 2.291% |

| RMSE | 4.782 | 2.651 | 1.782 | |

| R2 | 0.712 | 0.812 | 0.956 | |

| 2: 110 kV | MAPE | 5.191% | 3.789% | 2.291% |

| RMSE | 4.782 | 2.651 | 1.782 | |

| R2 | 0.671 | 0.752 | 0.913 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, S.; Xiang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Dai, L.; Zhang, T.; Yin, Y. A Hybrid Model Combining Signal Decomposition and Inverted Transformer for Accurate Power Transformer Load Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11241. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011241

Gao S, Xiang C, Zhou Y, Liu H, Dai L, Zhang T, Yin Y. A Hybrid Model Combining Signal Decomposition and Inverted Transformer for Accurate Power Transformer Load Prediction. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11241. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011241

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Shuguo, Chenmeng Xiang, Yanhao Zhou, Haoyu Liu, Lujian Dai, Tianyue Zhang, and Yi Yin. 2025. "A Hybrid Model Combining Signal Decomposition and Inverted Transformer for Accurate Power Transformer Load Prediction" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11241. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011241

APA StyleGao, S., Xiang, C., Zhou, Y., Liu, H., Dai, L., Zhang, T., & Yin, Y. (2025). A Hybrid Model Combining Signal Decomposition and Inverted Transformer for Accurate Power Transformer Load Prediction. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11241. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011241