1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Motivation

Urban wastewater infrastructure represents one of the most critical yet vulnerable components of modern city systems worldwide. With over 4.4 billion people living in urban areas today and this number projected to reach 6.7 billion by 2050 [

1], the sustainable management of sewer networks has become paramount for public health, environmental protection, and economic stability [

2]. These underground lifelines face mounting pressures from aging infrastructure, climate change, and rapid urbanization, leading to deterioration patterns that threaten service continuity and environmental safety [

3,

4]. Contemporary research demonstrates that approximately 56% of wastewater in major river basins leaks without treatment due to infrastructure inadequacy, while sewage overflow events have increased significantly as infrastructure fails to keep pace with demand [

5,

6].

Istanbul exemplifies these challenges at megacity scale, operating an extensive wastewater network of approximately 18,000 km of sewer pipelines, 1220 km of collectors, 201 km of tunnels, and 90 wastewater treatment plants, amounting to nearly 1.37 million individual sewer pipes [

7]. Like metropolitan areas globally, this infrastructure experiences accelerating deterioration due to physical, chemical, and operational stresses that result in structural defects including cracks, breaks, collapses, leaks, and joint displacements, as well as operational issues like roots, collapses, and blockages.

With increasing population density, sewer pipelines are exposed to physical, chemical, and operational stresses that lead to deterioration over time. Factors such as corrosion, soil movement, overloading, and insufficient maintenance result in structural defects including cracks, breaks, collapses, leaks, joint displacements, as well as operational issues like roots, collapses, and blockages [

8,

9,

10,

11]. These failures can reduce hydraulic capacity, cause untreated wastewater to infiltrate surface or groundwater, and ultimately create severe environmental, health, and economic consequences. Moreover, climate change and the rising frequency of extreme rainfall events place additional stress on urban drainage systems, further exacerbating infrastructure failures.

Since the construction and rehabilitation of sewer networks involve high capital investments, proactive inspection and timely maintenance are essential. Conventional inspection practices rely primarily on Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) systems, where remotely operated cameras are deployed into sewer lines to capture video footage for manual assessment [

12]. While widely used, this process is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and highly dependent on the operator’s expertise. In practice, limitations such as high operator workload, insufficient training, overlooked defects, and subjective interpretation reduce the accuracy and reliability of CCTV-based inspections [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Additional challenges include poor image quality due to moisture, deposits, or low lighting, as well as the complexity of detecting multiple defects simultaneously.

In response to these challenges, automated inspection systems leveraging artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL), have emerged as a transformative solution. The application of DL in this domain has evolved through distinct phases, each overcoming previous limitations while introducing new challenges.

1.2. Related Work

The first wave of research focused on adapting established convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures for sewer defect detection. This era was characterized by two parallel tracks: object detection models like Faster R-CNN and YOLO were deployed to localize defects [

17,

18,

19], while semantic segmentation architectures like U-Net and its variants were explored for pixel-level delineation of cracks and other flaws [

20,

21]. This period also saw the emergence of more advanced instance segmentation frameworks, such as Mask R-CNN and custom solutions like PipeSolo, which combined detection and segmentation for finer-grained analysis [

22,

23]. While these studies proved the concept and achieved significant accuracy improvements over manual methods, they were often limited by relatively small, homogenous datasets, focusing on a narrow set of high-prevalence defects.

Driven by the need for higher accuracy and robustness, a second wave of research refined CNN-based detectors with architectural and loss-function improvements tailored to the challenging conditions of sewer CCTV imagery. For example, Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP) and enhanced IoU losses (DIoU/CIoU) were incorporated into YOLOv4-style pipelines to better handle scale variation and stabilize bounding-box regression [

24]. At the same time, single-shot detectors were strengthened by multi-scale receptive-field modules and channel/coordinate attention mechanisms, approaches that improve small-defect sensitivity and suppress background noise [

16]. Other studies combined receptive-field blocks (RFB) with focal or class-balanced losses to mitigate class imbalance and emphasize rare operational defects, while attention modules such as CBAM or ECA were used to highlight defect-related features within cluttered scenes [

25]. These targeted interventions such as multi-scale fusion, attention, and improved loss formulations have produced notable gains in controlled evaluations (several works reporting mAP values exceeding ~80% on focused defect subsets), demonstrating that careful CNN engineering can substantially raise detection performance on real-world sewer data [

24,

26,

27].

The most recent wave in sewer-inspection research is characterized by the adoption of transformer-based and hybrid CNN–transformer architectures, which exploit global attention and improved multi-scale feature extraction to handle complex, cluttered CCTV scenes. For example, DefectTR demonstrated an end-to-end DETR-based pipeline for sewer defects (avoiding anchor design and NMS) and showed competitive localization accuracy on operational footage [

28]. Hybrid models that fuse convolutional encoders with transformer modules (e.g., PipeTransUNet) have been proposed for semantic segmentation and severity quantification, improving pixel-level delineation of defects [

29,

30]. Composite approaches that pair Swin-Transformer backbones with multi-stage detection heads (for example, Cascade R-CNN) have been successfully applied to sewer-defect detection and related small-object tasks, reporting consistent improvements in localization and mean-average-precision over CNN-only baselines [

31,

32].

To address fundamental data limitations, researchers have paired transformer adoption with data-centric strategies: GAN-/StyleGAN-based augmentation pipelines and synthetic image generation have been used to expand defect classes and balance rare categories, while few-shot or mask-guided generation approaches help produce realistic defect samples from limited examples [

33,

34,

35]. At the same time, lightweight real-time transformer variants (e.g., RT-DETR and its enhancements) are being explored to bring transformer performance to practical, live inspection settings [

36].

However, despite this rapid progression and increasing model sophistication, a critical analysis reveals persistent barriers to robust, real-world deployment:

The Data Scarcity Paradox: While large-scale datasets like Sewer-ML exist [

37], their utility is limited by task design. Sewer-ML is restricted to image-level classification and does not provide bounding box annotations, making it unsuitable for training and benchmarking object detection models. Moreover, there is a pronounced focus on a narrow set of structural defects (e.g., cracks, breaks), whereas operational defects with significant maintenance implications such as root intrusions, attached deposits, and hardened deposits, are frequently overlooked or severely underrepresented [

17,

38]. This underscores the need for detection-ready datasets such as the ISWDS, which explicitly address both structural and operational defects.

The Robustness Gap: Performance often drops significantly under real-world conditions not seen in the training data. Challenges like extreme occlusion, water obscuration, variable lighting, and lens distortion remain major obstacles [

39].

The Translation Gap: The field is dominated by frame-by-frame image analysis, with limited research on temporal modeling for video sequences, which could leverage context across frames to improve accuracy and efficiency. Furthermore, the step from a high-performing model to a validated, user-friendly tool integrated into asset management workflows (e.g., GIS systems) is rarely taken [

28,

40].

1.3. Positioning and Contributions

It is against this background of advanced yet contextually limited models that our study is positioned, aiming to bridge dataset diversity, real-time applicability, and integration into operational workflows. To address these limitations, this study proposes a comprehensive deep learning-based framework for automated defect detection in sewer inspection. The contributions of this work are threefold:

Development of the Istanbul Sewer Defect Dataset: a novel dataset comprising 13,491 images covering eight major defect classes (roots, crack, breaks, collapses, joint displacement, displaced joint, settled deposits, leakage and attached deposits). In contrast to Sewer-ML which, while large-scale, is primarily built on European standards and focuses more heavily on structural defects, the Istanbul dataset provides a more balanced coverage of both structural and operational defects. Classes such as settled deposits, leakage and attached deposits, often underrepresented in previous datasets, are included to better reflect the practical challenges faced by sewer operators. Based on the Istanbul Water and Sewage Administration (ISKI)’s geospatial database, these eight categories account for approximately 90% of all reported defects. This makes the dataset both representative and operationally grounded.

Comparative evaluation of state-of-the-art deep learning models: We benchmark models including YOLOv8, YOLOv11, YOLOv12, and the transformer-based RT-DETR-v1 and RT-DETR-v2, on the newly introduced Istanbul Sewer Defect Dataset. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically benchmark YOLO and RT-DETR side by side on real sewer inspection footage, offering comparative insights into their strengths across structural and operational defect types.

Practical integration for automated inspection: We discuss how the proposed models can support real-time decision-making during field operations and reduce operator dependence. On top of that, we integrate the best-performing model into a QGIS 3.34-based graphical user interface, enabling seamless geo-referenced defect logging and providing a user-friendly tool for inspection teams, demonstrating a direct path to field deployment and proactive infrastructure asset management.

While YOLO variants and transformer-based detectors such as RT-DETR have individually been applied in various domains, their systematic benchmarking protocols have not been conducted in the context of sewer defect detection. Our work provides the first comparative analysis, highlighting trade-offs between accuracy and computational efficiency that are essential for practical deployment. This comparison is of high practical relevance: sewer inspection requires both lightweight, real-time models suitable for edge devices and high-accuracy transformer models suitable for server-based processing. By providing the first systematic evaluation of YOLO and RT-DETR in this domain, the study delivers critical insights into model selection strategies for real-world sewer inspection workflows.

In addition, this study contributes to literature in several ways that extend beyond conventional benchmarking. It provides the first systematic comparison of CNN-based (YOLO) and transformer-based (RT-DETR) detectors on real sewer inspection data, a dimension that has not been addressed in previous research. The analysis incorporates class-wise performance metrics together with statistical significance testing, which strengthens the robustness and reproducibility of the findings. The study also outlines practical deployment pathways by demonstrating that YOLO variants are suitable for embedded, on-site inspection devices, whereas RT-DETR achieves higher detection accuracy for centralized, server-based processing. Moreover, to foster transparency and facilitate future research, the trained models have been made publicly available on Hugging Face, enabling independent validation and extension.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. Istanbul Sewer Defect Dataset

The Istanbul Sewer Defect Dataset (ISWDS) is a novel, expert-curated dataset developed to address the need for a comprehensive, region-specific benchmark for automated sewer defect detection. The imagery was collected and annotated according to the principles of EN 13508-2:2003+A1:2011 standard [

41], which provides a systematic coding system for the objective and comparable assessment of sewer infrastructure conditions across European member states.

The dataset comprises CCTV inspection videos from the extensive wastewater network of Istanbul, provided by ISKI. Data was collected between 2021 and 2024 across all 39 districts of the city, ensuring wide geographical and operational diversity. The videos were captured under varying conditions including different times of day, weather, water levels, and lighting using a variety of robotic CCTV systems (

Figure 1). Approximately 95% of the images were acquired using cameras, capable of recording up to 30 FPS in Full HD resolution (1920 × 1080). The raw video footage exhibited a wide range of resolutions and frame rates, reflecting the heterogeneity of real-world inspection equipment.

To construct the dataset, frames were meticulously extracted from hours of video. A key challenge addressed during curation was the variable speed of the inspection crawlers. While the scientific maximum recommended speed is 0.25 m/s, operational practices often involve faster speeds (0.35–0.50 m/s), leading to motion blur and reduced image quality. Frames with excessive blur or poor clarity were manually excluded by a team of two expert annotators to ensure the dataset’s quality.

The annotation process was conducted using the open-source AnyLabeling v0.3.3 tool over a period of approximately four months. The experts labeled images across eight critical defect classes, focusing on a single primary defect per image to ensure label clarity. The classes were selected to provide a balanced coverage of both structural and operational defects, as defined by the EN 13508-2 standard, and reflect the most common and critical failure modes in Istanbul’s infrastructure. All annotations were performed in the YOLO format, using bounding boxes to localize each defect instance. The final class distribution is presented in

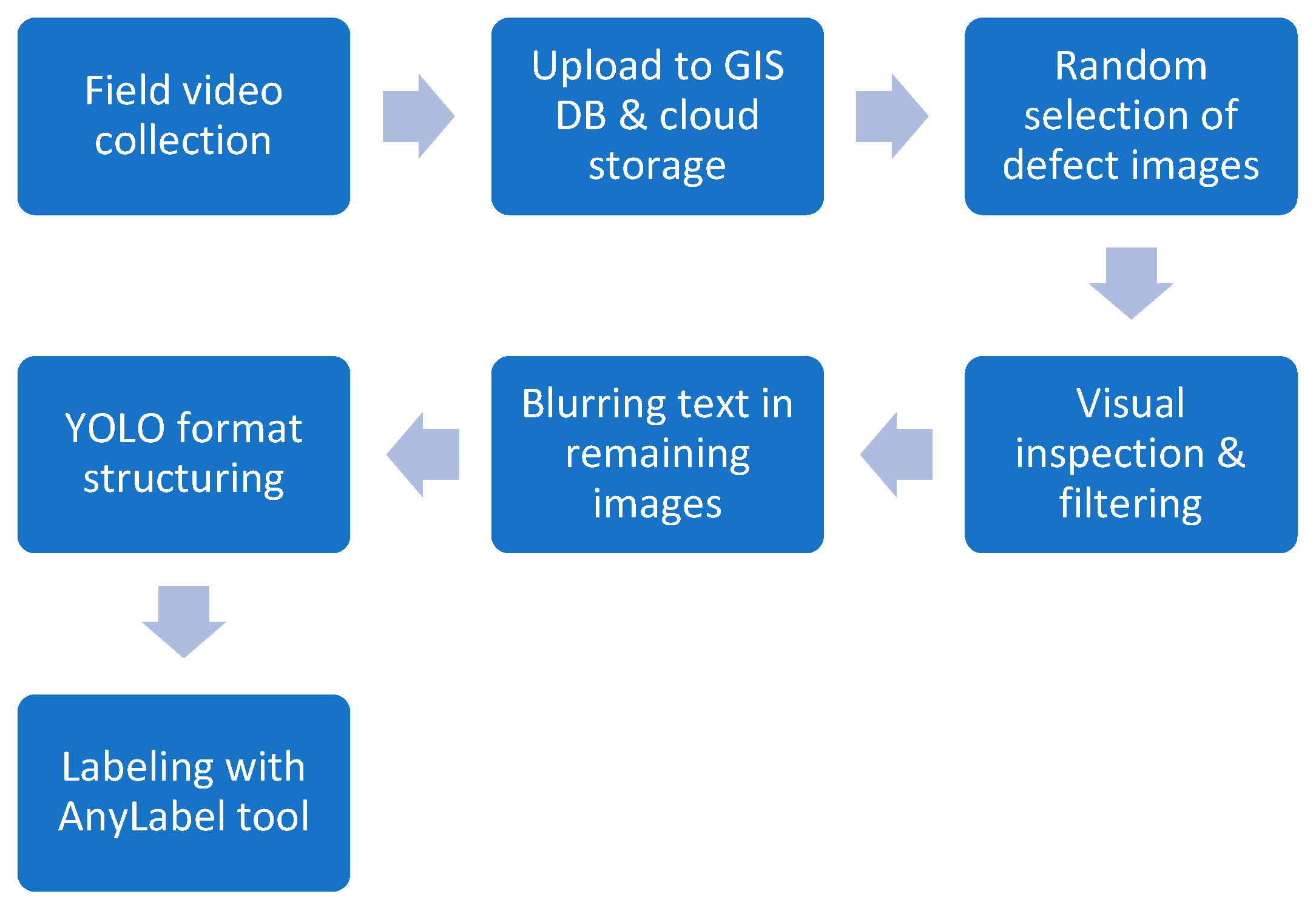

Table 1. The dataset preparation workflow is shown in

Figure 2.

The ISWDS is characterized by its real-world complexity, including challenges such as turbid water, occlusions, lens distortions, and uneven illumination. Unlike Sewer-ML, which is larger but limited to image-level classification and heavily focused on structural defects, ISWDS provides bounding box annotations and a more balanced representation of operational defects such as attached deposits and settled deposits, which are critical in Istanbul’s network. To ensure privacy and comply with data regulations, all text overlays and operator information within the images were automatically detected using the EasyOCR 1.7.1 library (with >95% accuracy) and blurred via a Gaussian filter implemented with OpenCV 4.12.0.88.

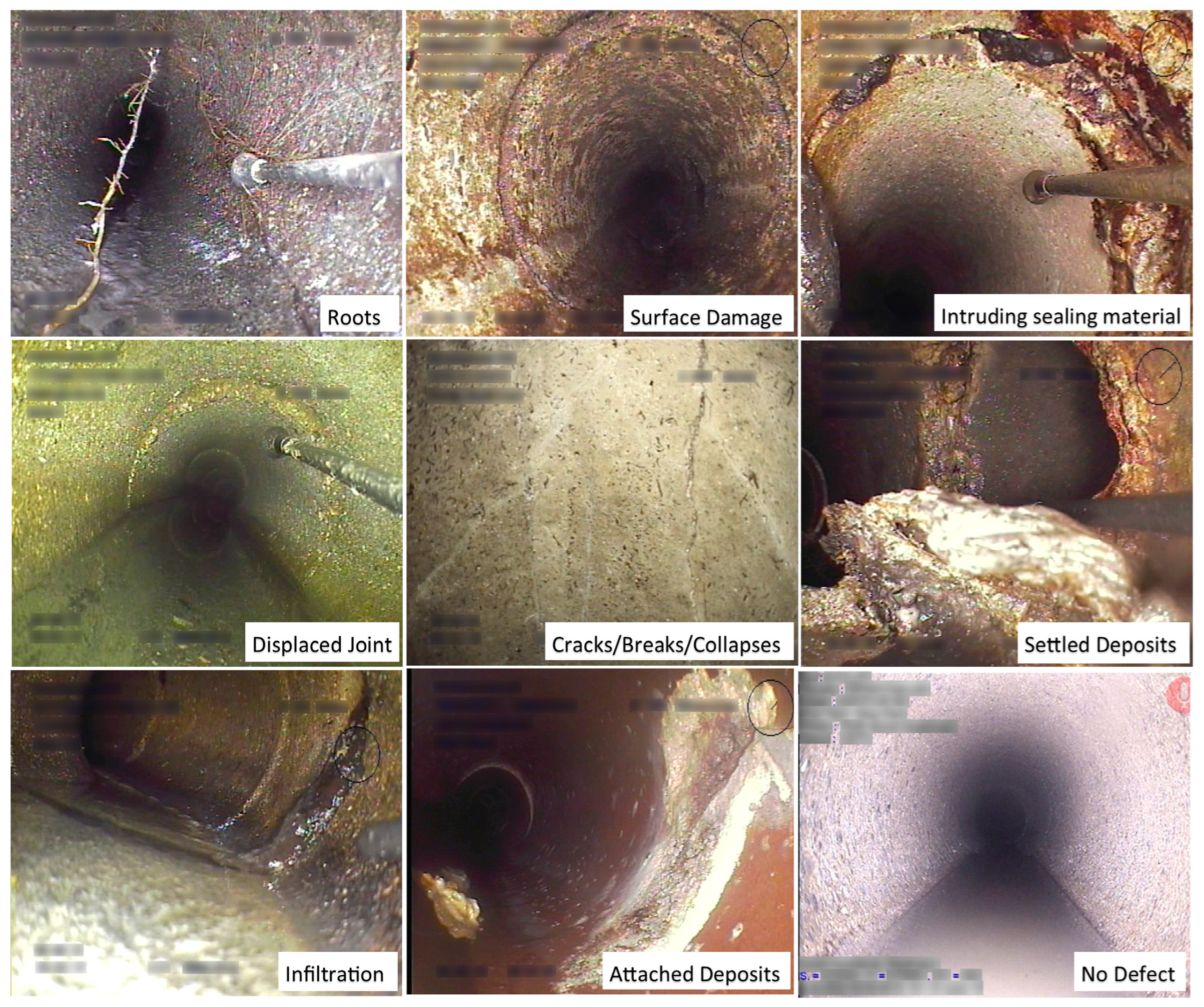

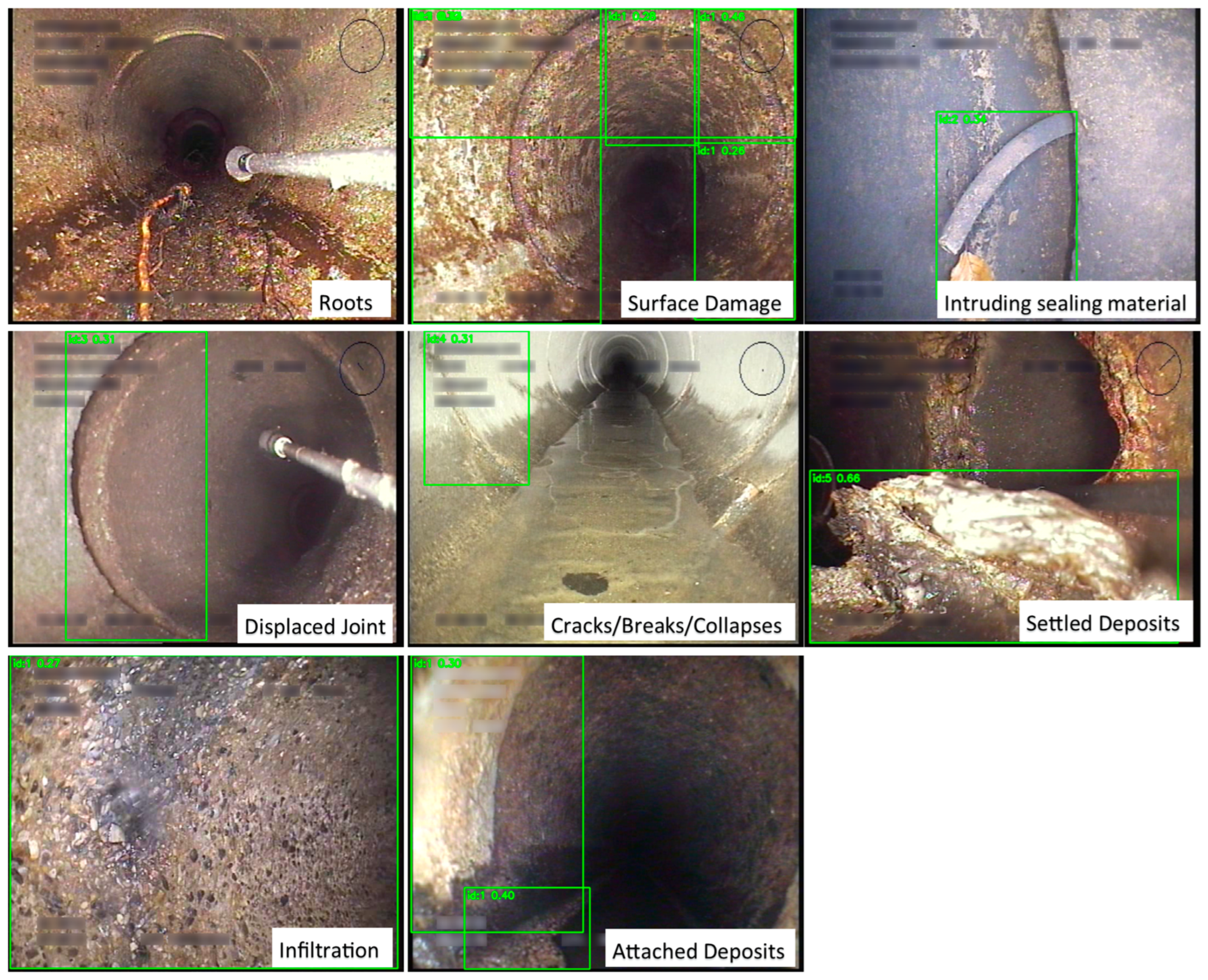

The dataset is not naturally balanced, reflecting the inherent imbalanced distribution of defects in real sewer systems. For instance, cracks and attached deposits are more prevalent than roots or infiltrations. This intentional preservation of class imbalance allows for the development of robust models to real-world operational conditions. The final dataset consists of 13,491 high-quality, annotated images ready for model development. A sample of annotated images from the ISWDS, showcasing the variety of defects and conditions is presented in

Figure 3.

All image data is the property of ISKI, and official permission for its use in this research was obtained. Due to the sensitive nature of public infrastructure data and privacy agreements, the ISWDS is a closed dataset for internal research use and is not publicly distributed.

2.1.2. Comparison with Existing Datasets

Several datasets have been proposed for sewer defect analysis and are summarized in

Table 2, ranging from small-scale collections [

18,

37,

38,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47] to the large-scale Sewer-ML dataset [

37]. As summarized in

Table 2, most existing datasets suffer from either small sample sizes, lack of diverse defect classes, or missing annotations required for object detection. For example, Ye et al. [

42] provided only 1045 defective images across seven classes, while Myrans et al. [

43] reported 2260 samples distributed over 13 classes. Similarly, Chen et al. [

44], Li et al. [

45], Kumar et al. [

18], and Xie et al. [

47] produced datasets with limited class diversity and imbalance, often focusing on structural rather than operational defects.

Sewer-ML [

37], released as a large-scale public dataset, contains more than 1.3 million images (609,479 defective, 690,722 normal) across 17 classes. While it represents the largest benchmark to date and supports multi-label classification, its annotations are restricted to image-level labels without bounding boxes, limiting its suitability for object detection tasks. Furthermore, although Sewer-ML covers 17 defect categories, operational defects of practical significance (e.g., deposits, leakage, root intrusion) remain underrepresented.

In contrast, the Istanbul Sewer Defect Dataset (ISWDS) introduced in this study provides 13,491 images with bounding-box annotations for eight defect classes that collectively represent approximately 90% of real-world failures recorded in Istanbul’s wastewater network. The ISWDS ensures a more balanced representation of both structural and operational defects, offering a practically grounded benchmark for object detection models and real-world deployment.

2.2. Model Training

2.2.1. Deep Learning Architectures

To evaluate the performance of the proposed Istanbul Sewer Defect Dataset (ISWDS), a comprehensive comparative analysis was conducted using three state-of-the-art object detection architectures. The selection criteria prioritized models renowned for their high accuracy, computational efficiency, and relevance to real-time inspection tasks. The chosen models represent the current evolution of deep learning for object detection: the latest iterations of the well-established YOLO family, known for their speed-accuracy trade-off, and a modern real-time transformer-based detector, RT-DETR, which offers an end-to-end approach. The following subsections provide a concise overview of each model’s fundamental architecture and its key innovations.

2.2.2. You Only Look Once (YOLO) Architecture Family

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) family of architecture represents a cornerstone of modern, single-stage (single-forward-pass) object detection, renowned for its exceptional balance between speed and accuracy, making it ideal for real-time applications such as sewer inspection. The core YOLO principle involves dividing an input image into an S × S grid, where each cell simultaneously predicts the probability of an object’s presence and the coordinates of its bounding box. This unified approach to classification and localization reduces computational latency and leverages contextual information more effectively than traditional two-stage detectors.

Architecturally, YOLO models are generally composed of three primary components:

Backbone: A convolutional neural network (e.g., CSPDarknet) responsible for extracting multi-scale feature maps from the input image.

Neck: A module (e.g., PANet, BiFPN) that aggregates and fuses these features from different layers to enhance the representation of objects across scales.

Head: The final component that performs the simultaneous classification of objects and regression of their bounding box coordinates.

This study employs three distinct iterations of YOLO architecture to provide a comprehensive benchmark across different generations of architecture.

YOLOv8. Developed by Ultralytics (Frederick, MD, USA) in 2023, YOLOv8 represents a mature and widely adopted architecture that serves as our baseline model. The architecture introduces several key innovations that distinguish it from previous YOLO versions. The model implements anchor-free detection, which eliminates pre-defined anchor boxes and instead predicts object centers directly while regressing to bounding box dimensions. This approach simplifies the detection pipeline and reduces the need for hyperparameter tuning related to anchor configuration. The backbone utilizes CSPDarknet53, which incorporates Cross Stage Partial connections to improve gradient flow while reducing computational cost compared to traditional darknet architectures. For multi-scale feature fusion, YOLOv8 employs a Path Aggregation Network (PAN) neck that implements bottom-up path augmentation to enhance feature fusion across different scales, enabling better detection of objects at various sizes. The detection head uses a decoupled design that separates classification and regression tasks into distinct head branches, which improves training stability and allows for independent optimization of each task. For bounding box regression, the model employs Complete IoU (CIoU) loss, which incorporates distance, overlap, and aspect ratio considerations to achieve more accurate bounding box predictions compared to traditional IoU-based losses. The model is available in five scales (n, s, m, l, x) with parameter counts ranging from 3.2 M to 68.2 M parameters, allowing for flexible deployment across different computational constraints.

YOLOv11 released in 2024 by Ultralytics, YOLOv11 introduces several architectural refinements over YOLOv8 that enhance both performance and efficiency. The architecture replaces standard C3 modules with C3k2 blocks that incorporate selective kernel mechanisms, allowing for adaptive receptive field adjustment based on input characteristics. This modification enables the network to dynamically adapt its feature extraction capabilities to different object scales and contexts. The model also improves upon the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) module by incorporating additional pooling scales, which provides better multi-scale feature extraction capabilities essential for detecting objects of varying sizes in complex sewer environments. A notable innovation is the integration of C2PSA (C2 Partial Self-Attention) modules that incorporate lightweight self-attention mechanisms in deeper network layers. These attention modules enable the capture of long-range dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency, allowing the model to better understand spatial relationships across the entire image. Additionally, YOLOv11 implements an improved data augmentation pipeline that utilizes MixUp, CutMix, and Mosaic augmentations with adaptive scheduling during training, which enhances the model’s robustness to various imaging conditions commonly encountered in sewer inspection scenarios. The architectural changes result in improved accuracy–efficiency trade-offs, particularly for small object detection, while maintaining similar parameter counts to YOLOv8.

YOLOv12. YOLOv12, released in early 2024, represents an experimental evolution that incorporates more advanced attention mechanisms compared to its predecessors. The architecture implements Efficient Local Attention Networks (ELAN) that provide efficient attention modules designed to balance local and global feature interactions, enabling better contextual understanding while maintaining computational efficiency. The model incorporates RepVGG-style blocks that utilize structural re-parameterization during inference to reduce computational overhead while maintaining training-time expressiveness, allowing for a more efficient inference pipeline without sacrificing the model’s learning capacity during training. Another key innovation is the adaptive feature pyramid that dynamically adjusts feature pyramid weights based on input characteristics, enabling the network to automatically optimize feature fusion for different types of input images. YOLOv12 also includes enhanced augmentation strategies that incorporate advanced photometric and geometric augmentations specifically tuned for complex visual scenarios, which should theoretically improve performance in challenging conditions such as those encountered in sewer inspection environments. However, it is important to note that YOLOv12 showed mixed results in our experiments, with the largest variant (YOLOv12x) underperforming compared to other models in the series, suggesting that the architectural innovations may require further refinement or different training strategies to achieve their full potential.

For this study, all YOLO variants were initialized with pre-trained weights and trained on the same dataset using an identical transfer learning strategy to ensure a fair and objective comparison of their inherent architectural capabilities.

2.2.3. Real Time Detection Transformer (RT-DETR)

RT-DETR, developed by Baidu (Beijing, China) in 2024 [

48], is an optimized variant of the DETR (DEtection TRansformer) architecture, specifically designed for efficient, end-to-end object detection in real-time applications. Its most significant advantage over conventional detectors is the complete elimination of the Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) post-processing step, which reduces computational complexity and inference latency.

RT-DETR v1. RT-DETR v1 consists of four key components:

HGNet-v2 backbone: A hybrid CNN backbone that combines depthwise separable convolutions with residual connections for efficient feature extraction.

Hybrid encoder: Implements both intra-scale and cross-scale attention mechanisms using attention-based Intrascale Feature Interaction (AIFI) and Cross-scale Feature Fusion (CCFF) modules.

Transformer decoder: Uses 6 decoder layers with learnable object queries (300 queries by default) that attend to encoder features.

Prediction heads: Separate classification and regression heads that output final predictions without requiring NMS.

The architecture incorporates several key innovations that distinguish it from traditional detection methods. RT-DETR v1 implements uncertainty-guided query selection that improves query initialization by leveraging prediction uncertainty, allowing the model to focus computational resources on the most informative regions of the image. The model also employs an IoU-aware classification loss function that combines classification confidence with localization quality, ensuring that high classification scores correspond to accurate bounding box predictions. Additionally, the architecture utilizes efficient attention mechanisms that reduce attention complexity through separable attention mechanisms, significantly improving computational efficiency while maintaining the model’s ability to capture long-range spatial dependencies across the entire image.

RT-DETR v2. RT-DETR v2, released later in 2023, introduces several improvements over v1:

Enhanced backbone options: Supports both HGNet-v2 and ResNet backbones with optimized feature extraction

Dynamic query selection: Implements learnable query initialization that adapts based on input image characteristics

Improved multi-scale fusion: Uses deformable attention mechanisms in the encoder for better feature alignment

Optimized training strategy: Incorporates knowledge distillation and progressive resizing during training

Here is the RT-DETR comparison and performance characteristics section rewritten as continuous prose without bullet points:

The key differences between RT-DETR v1 and v2 center on several architectural and training improvements. RT-DETR v2 uses more sophisticated query selection mechanisms that better adapt to input characteristics, while also incorporating enhanced multi-scale attention in the encoder that provides improved feature alignment across different scales. The newer version also benefits from improved training protocols that result in better convergence properties, though this comes at the cost of slightly higher computational requirements while delivering improved accuracy. Both RT-DETR variants eliminate the need for anchor generation and NMS post-processing, making them truly end-to-end trainable and deployable for real-time applications.

RT-DETR architectures offer several distinct advantages over traditional detection methods. The models provide end-to-end optimization that allows direct optimization of final detection metrics without requiring intermediate processing steps, which simplifies the training pipeline and reduces potential sources of error. They also offer flexible inference speed capabilities, as the number of object queries can be adjusted at inference time to balance speed versus accuracy according to application requirements. The global attention mechanisms inherent in the transformer architecture enable better handling of crowded scenes by helping to detect overlapping objects that might be missed by local feature-based methods. Additionally, RT-DETR models demonstrate consistent performance and are less sensitive to hyperparameter tuning compared to anchor-based methods, making them more robust across different deployment scenarios.

However, the transformer-based architecture also introduces certain limitations that must be considered. The attention mechanisms require higher memory requirements during training, which may limit deployment of resource-constrained hardware. RT-DETR models typically require longer training times as transformer architectures generally need more epochs to converge compared to convolutional networks. Furthermore, there are currently limited pre-trained models available for RT-DETR variants compared to the extensive ecosystem of YOLO checkpoints, which may impact transfer learning capabilities for specialized applications.

This study utilizes RT-DETR-v1 and RT-DETR-v2, which builds upon these core efficient design principles. All models, including RT-DETR, were initialized with weights pre-trained on the COCO dataset and fine-tuned on the sewer defect dataset to ensure a fair comparison and leverage the benefits of transfer learning.

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of all trained models was rigorously evaluated on a held-out test set using a comprehensive suite of standard object detection metrics. These metrics were calculated for each defect class individually and averaged across all classes to provide a holistic view of model performance, highlighting specific strengths and weaknesses.

The primary metrics used for comparison are defined as follows:

Precision (P) measures the model’s ability to avoid false positives, representing the proportion of correctly identified defects among all predicted defects.

Recall (R), or True Positive Rate, measures the model’s ability to find all true defects, representing the proportion of actual defects that were correctly detected.

F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances the trade-off between these two values. It is particularly valuable for evaluating performance on imbalanced datasets.

Average Precision (AP) is calculated for each class as the area under the precision-recall curve, integrating performance across all confidence thresholds. mean Average Precision (mAP) is the primary metric for overall model accuracy. We report two variants:

mAP@0.5: The mean AP calculated at a single Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5. This is a common benchmark but represents a loose localization criterion.

mAP@0.5:0.95: The mean AP averaged over multiple IoU thresholds, from 0.5 to 0.95 in steps of 0.05. This is a stricter, more comprehensive metric that heavily penalizes inaccurate bounding box predictions, making it the gold standard for object detection challenges like COCO.

Inference Speed is measured in Frames Per Second (FPS) to assess the model’s suitability for real-time sewer inspection video processing applications. Model Size is reported in terms of the number of parameters and file size (MB), which is critical for evaluating deployment feasibility on hardware with limited computational resources.

For a complete picture of the training process, auxiliary metrics such as training and validation losses (box loss, classification loss, distribution focal loss) were also monitored to diagnose potential overfitting and ensure convergence.

Furthermore, for all IoU-based metrics, a detection was considered correct if the predicted bounding box overlapped with the ground truth by at least 0.5 IoU. To better assess localization performance for small-scale defects such as cracks or partial pipe damage, higher IoU thresholds were also analyzed, highlighting the model’s precision in localizing fine-grained defects.

3. Results

This section details the experimental setup and reports the results obtained from YOLO-family models and RE-DETR on the ISWDS dataset. The results are analyzed using the evaluation metrics described earlier, with particular attention to differences across defect categories and model families.

3.1. Experimental Setup

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison, all models were trained and evaluated under a consistent experimental framework. This subsection details the implementation environment, training configurations, dataset handling, and loss functions used, establishing the foundation for the subsequent performance analysis.

All models were implemented using the PyTorch deep learning framework (v2.0.1) within the Ultralytics YOLO ecosystem for YOLO variants and the PaddlePaddle framework for RT-DETR. The choice of separate ecosystems reflects the respective maturity and optimized implementations available for each architecture. Experiments were conducted on a system running Ubuntu 22.04 with CUDA 11.7 and cuDNN 8.5.0. The hardware consisted of an Intel i9 processor, 32 GB of RAM (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 Ti GPU (8 GB VRAM; NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The core hyperparameters for training are summarized in

Table 3. All models were trained from pre-trained weights on the MS COCO dataset to leverage transfer learning. The input image size was standardized to 640 × 640 pixels for all architectures. The batch size was adjusted for each model within a range of 7 to 16 to maximize GPU memory utilization without causing out-of-memory errors. While the AdamW optimizer was used for all models in this study, YOLOv12 was trained with SGD to align with its recommended default configuration. A cosine annealing learning rate scheduler was used, starting from an initial learning rate (lr0) of 0.01 for YOLO models and 0.0001 for RT-DETR models, and decaying to a final learning rate (lrf) of 0.01.

The Istanbul Sewer Defect Dataset (ISWDS) was randomly split into training (70%), validation (20%), and test (10%) sets. Importantly, this split was performed at the video level rather than the frame level to prevent data leakage. Since the dataset was constructed from video recordings, individual frames were extracted and used as images. Typically, only a single representative frame was selected from each video for a given defect type in order to avoid redundancy. This strategy ensured that no frames originating from the same video appeared across different subsets, thereby preserving the independence of training, validation, and testing data.

A comprehensive set of data augmentation techniques was applied in real-time during training to improve model robustness and mitigate overfitting. These augmentations simulate the wide variability in real-world sewer inspection conditions, ranging from lighting inconsistencies to occlusions. Specifically:

Geometric transformations: Horizontal flipping (probability = 0.5), rotation (±10°), and translation

Photometric transformations: Adjustments to brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue (color jitter).

Advanced techniques: Mosaic augmentation (stitching four images together) and CutOut (randomly masking out rectangular sections of the image).

The YOLO models utilized a composite loss function consisting of bounding box regression loss (CIoU), objectness loss, and classification loss. The RT-DETR model employed a set prediction loss, which uses the Hungarian algorithm for optimal bipartite matching between predictions and ground truth. This loss combines Focal Loss for classification and a combination of L1 and Generalized IoU (GIoU) loss for bounding box regression.

3.2. Quantitative Results and Performance Benchmarking

To enable a fair comparison across architectures, we report standard detection metrics (precision, recall, F1-score, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95) for all trained models on the ISWDS test set. The overall performance metrics for all models are summarized in

Table 4. The results reveal a clear performance–efficiency trade-off among the architectures and their scales.

A fundamental trade-off between recall and precision was observed. RT-DETR models consistently achieved the highest recall values (v1: 0.807, v2: 0.811), indicating superior detection of true defects and fewer missed detections (false negatives). In contrast, YOLO models generally achieved higher precision (e.g., YOLOv11m: 0.796), meaning their positive predictions were more reliable but potentially missed some defects.

The F1-Score, which balances precision and recall, identifies RT-DETR v2 (0.790) as the best overall model, followed by RT-DETR v1 (0.764). Among the YOLO family, YOLOv12l achieved the highest F1-Score (0.754). This suggests that for a task where both avoiding false alarms and missing defects are important, RT-DETR provides a more balanced and superior solution.

The mAP@0.5:0.95 metric, which requires precise localization, shows that YOLOv11l (0.566) and RT-DETR v2 (0.565) achieved the highest scores, indicating they are the most accurate models when strict bounding box alignment is required. The performance across YOLO versions (v8, v11, v12) was largely comparable, with no single version dominating the others.

Computational efficiency is a critical consideration for practical deployment, particularly in real-time or resource-constrained scenarios.

Table 5 summarizes key training parameters and model sizes, including the number of epochs, batch sizes, ONNX file sizes, and total training time. Despite comparable runtimes, RT-DETR’s transformer-based design incurred slightly higher computational overhead, whereas YOLO variants benefited from their streamlined convolutional backbones.

From the table, it is evident that larger models such as YOLOv12x and YOLOv8x require substantially longer training times and smaller batch sizes due to GPU memory constraints. In contrast, the nano and small variants of YOLO train much faster and can utilize larger batch sizes, making them suitable for rapid prototyping or deployment on edge devices. Some models, including YOLOv8x, YOLOv11m, and YOLOv12n, reached convergence before completing the maximum number of epochs, demonstrating that early stopping can reduce total training time while maintaining competitive performance. The RT-DETR models, while highly accurate, require longer training times of approximately 10 h and moderate batch sizes, reflecting the increased computational demand of transformer-based architecture.

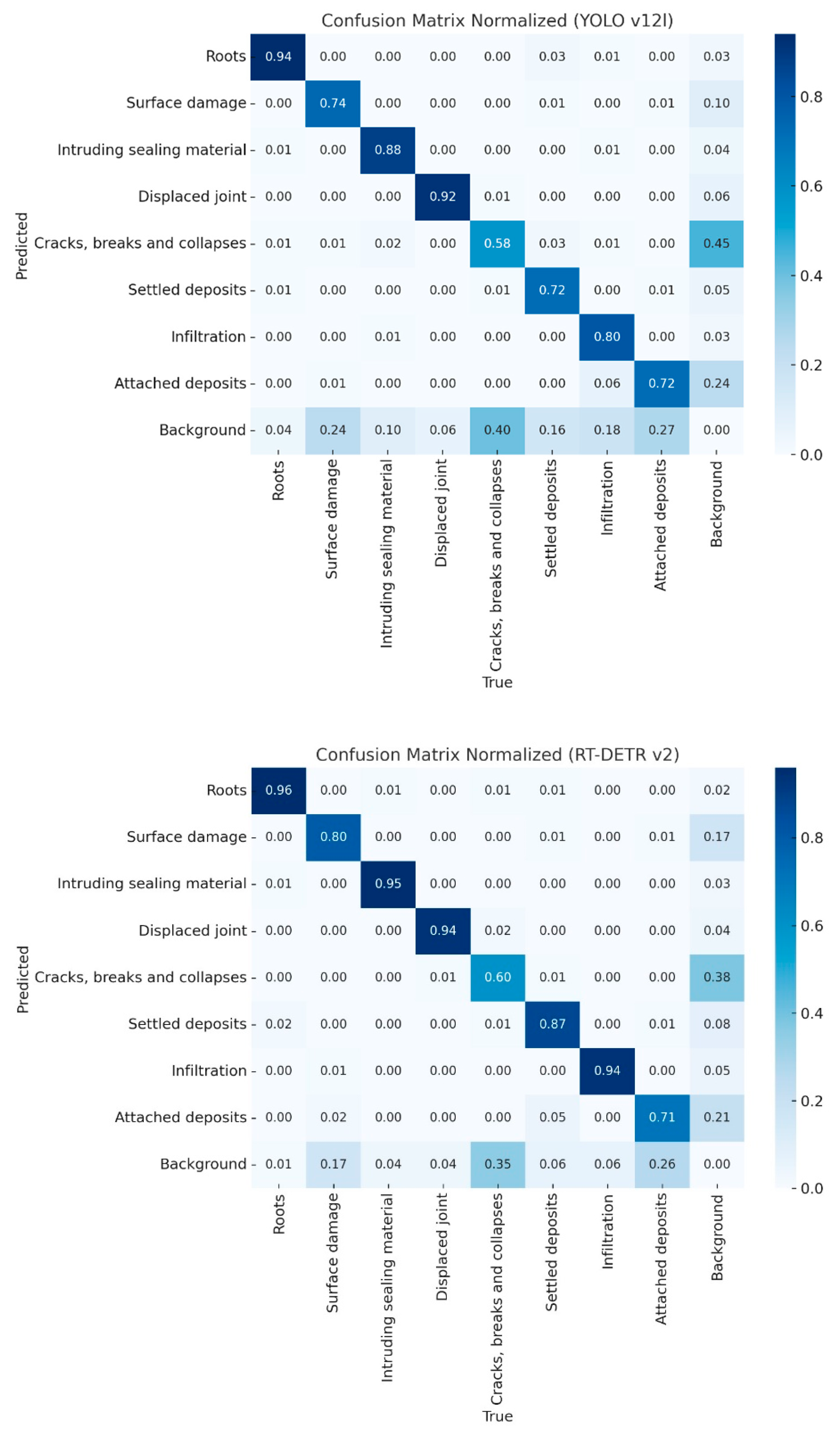

A critical analysis was performed to understand model performance for each of the eight defect classes for the best performing YOLO and RT-DETR model in terms of F1-Score (

Table 6). This evaluation provides insights into how different architectures handle the diverse visual characteristics of operational and structural defects.

The analysis shows that RT-DETR v2 consistently outperforms YOLOv12l across all defect classes, demonstrating the transformer-based architecture’s superior ability to model complex spatial dependencies and contextual information in terms of F1-Scores. Its advantage is particularly pronounced for operational defects such as Roots and Displaced joint, where F1-Scores exceed 90%, indicating highly reliable detection.

Crack/breaks and collapses remain the most challenging class, with both models yielding the lowest F1-Scores (YOLOv12l: 54.91%, RT-DETR v2: 63.17%), highlighting the difficulty in detecting thin, irregular, and low-contrast features. This challenge is further reflected in low mAP@0.5:0.95 values for both models, suggesting that precise localization of such defects remains a limitation.

3.3. Results with Statistical Analysis

To strengthen the reliability of the reported findings, we incorporated standard deviations, confidence intervals, and statistical significance tests in addition to the conventional evaluation metrics. Without retraining, measurement uncertainty was estimated via bootstrap resampling with B = 2000 resamples (sampling with replacement) over the test set. For each resample, precision, recall, F1-score, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 were recomputed, results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (sd). In line with common practice in the object detection literature, per-image metrics (precision, recall, and F1-score) are reported with sd, whereas dataset-level summary metrics (mAP) are additionally accompanied by 95% percentile confidence intervals (CI) (

Table 7). The detection score threshold was set to 0.50 when computing per-image precision/recall/F1 metrics, whereas AP values were obtained in the standard threshold-free manner. To ensure reproducibility, the random seed was fixed at 42 during bootstrap resampling. The 95% confidence intervals for mAP values were relatively narrow (±1.5–1.7), reflecting the stability of model performance across the large validation set (N = 2495 images). This suggests that the reported improvements are unlikely to be due to sampling variability and can be considered statistically robust.

In addition, paired permutation tests with Holm correction (to adjust for multiple comparisons) were conducted to assess the significance of differences between the models. The results indicated: Precision: No statistically significant difference was observed (p = 0.115). Recall: RT-DETR v2 achieved significantly higher recall compared to YOLOv12l (p = 0.0001). F1-score: RT-DETR v2 also significantly outperformed YOLOv12l in F1-score (p = 0.0001). Although the per-image metric distributions were symmetric and yielded median differences close to zero, permutation tests still revealed statistically significant differences in the distributions of recall and F1-score. This means that, even if the central tendency appeared identical, RT-DETR v2 consistently provided more reliable detection outcomes across images. The incorporation of confidence intervals and distributional tests thus reinforces the robustness of the reported performance and ensures that the observed improvements are not only quantitatively meaningful but also statistically robust.

3.4. Qualitative Results and Error Analysis

Beyond quantitative metrics, a qualitative analysis was conducted on sample images from the test set to visually assess the detection capabilities, strengths, and failure modes of the top-performing models: YOLOv12l (best YOLO variant by F1-Score) and RT-DETR v2 (overall best model). A confidence threshold of 0.25 was used for both models to ensure a comprehensive comparison of their predictions.

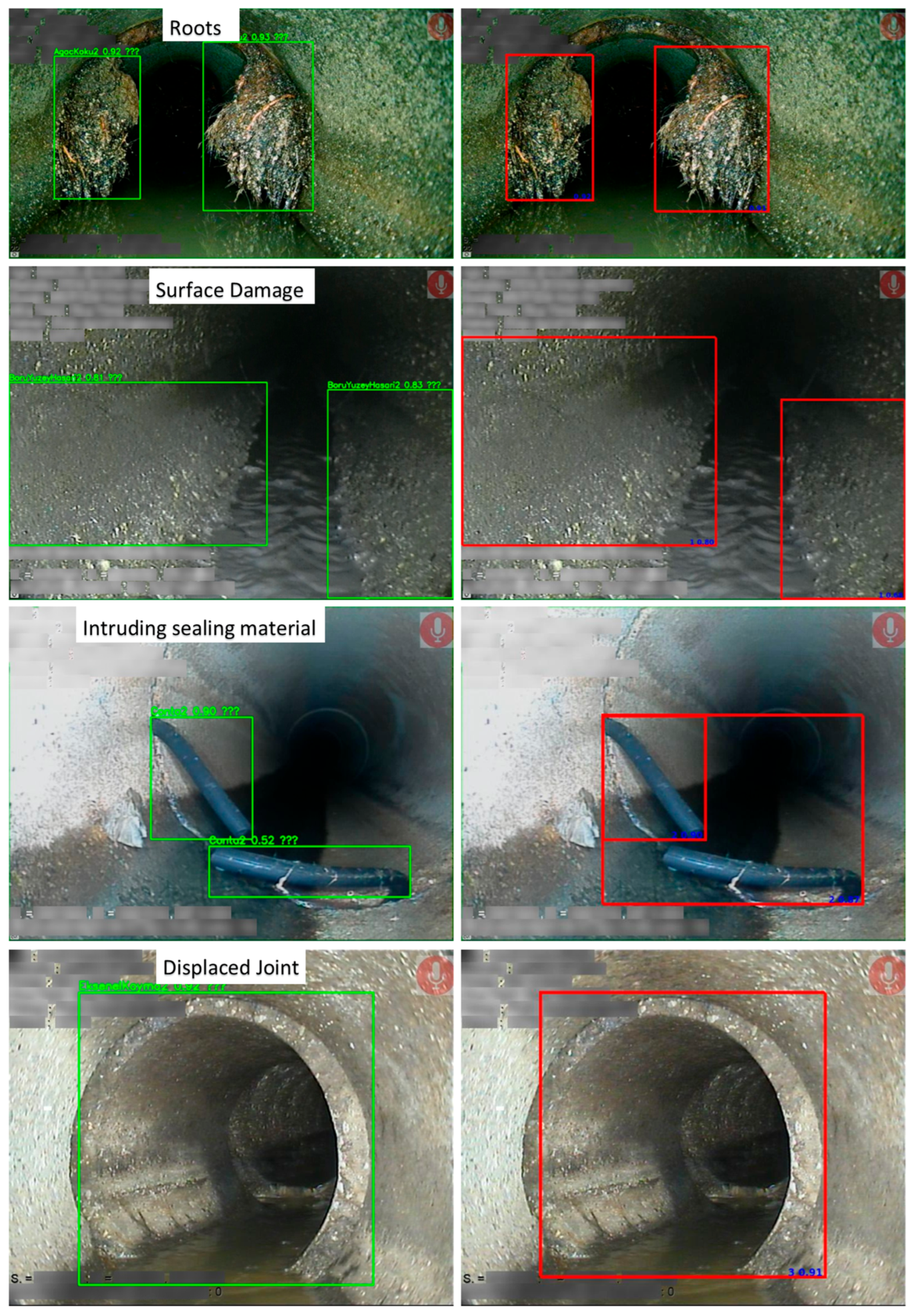

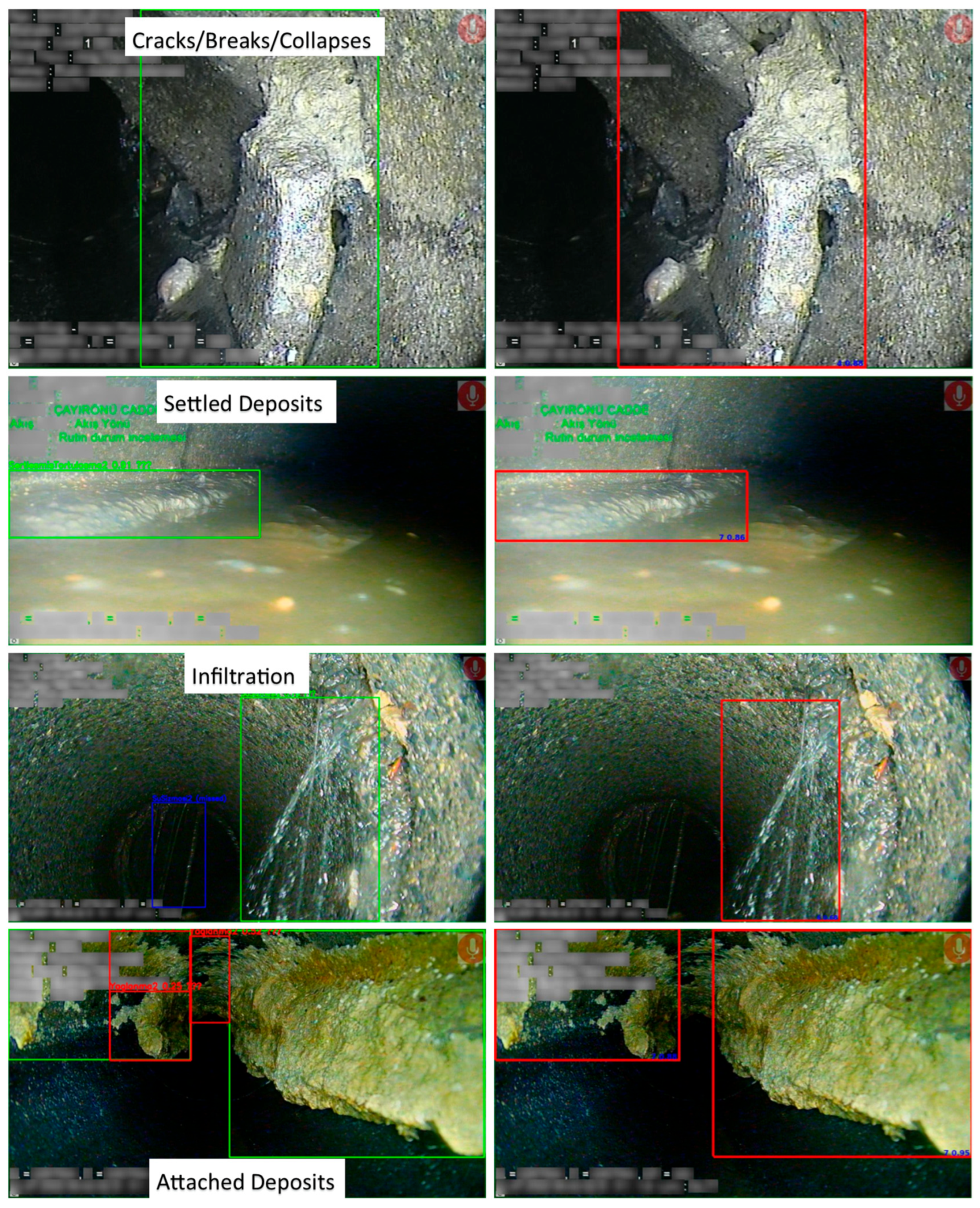

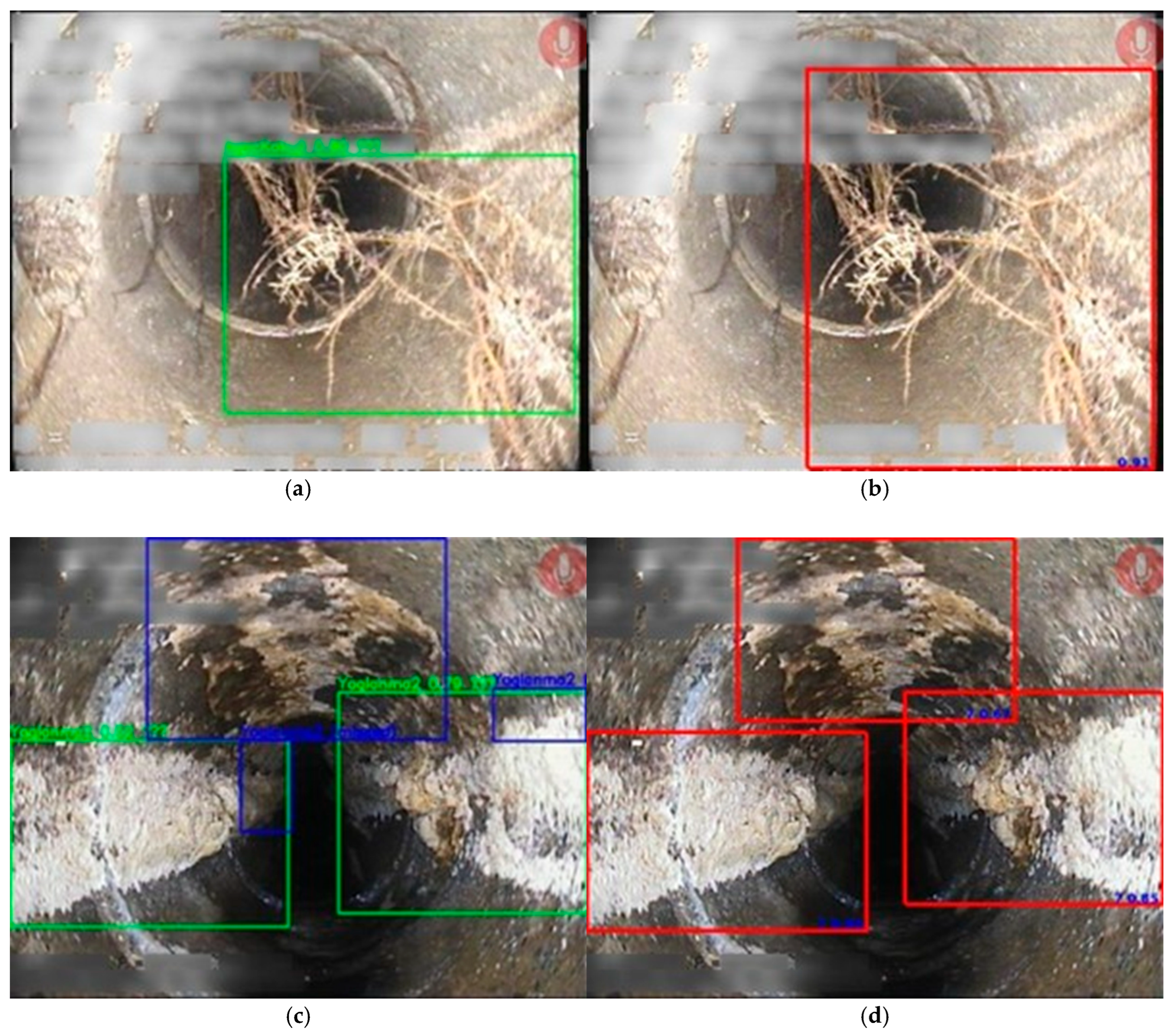

Figure 4 presents example result images for all classes. The left column shows inference results obtained with YOLOv12l, whereas the right column presents the corresponding results produced by RT-DETR v2.

Both models demonstrated proficient detection capabilities across various defect types. However, key differences in their approach were observed:

As shown in

Figure 5, both models correctly identified roots. RT-DETR v2 consistently produced larger and more precise bounding boxes that more completely encapsulated the entire defect structure, reflecting its superior localization accuracy (

Figure 5b).

Figure 5 also highlights the critical strength of transformer architecture. RT-DETR v2 successfully detected attached deposits that were occluded or only partially visible along the pipe crown (

Figure 5d). In contrast, YOLOv12l failed to detect these instances (

Figure 5c), indicating RT-DETR’s enhanced ability to leverage global contextual information within the image to identify challenging, low-contrast defects.

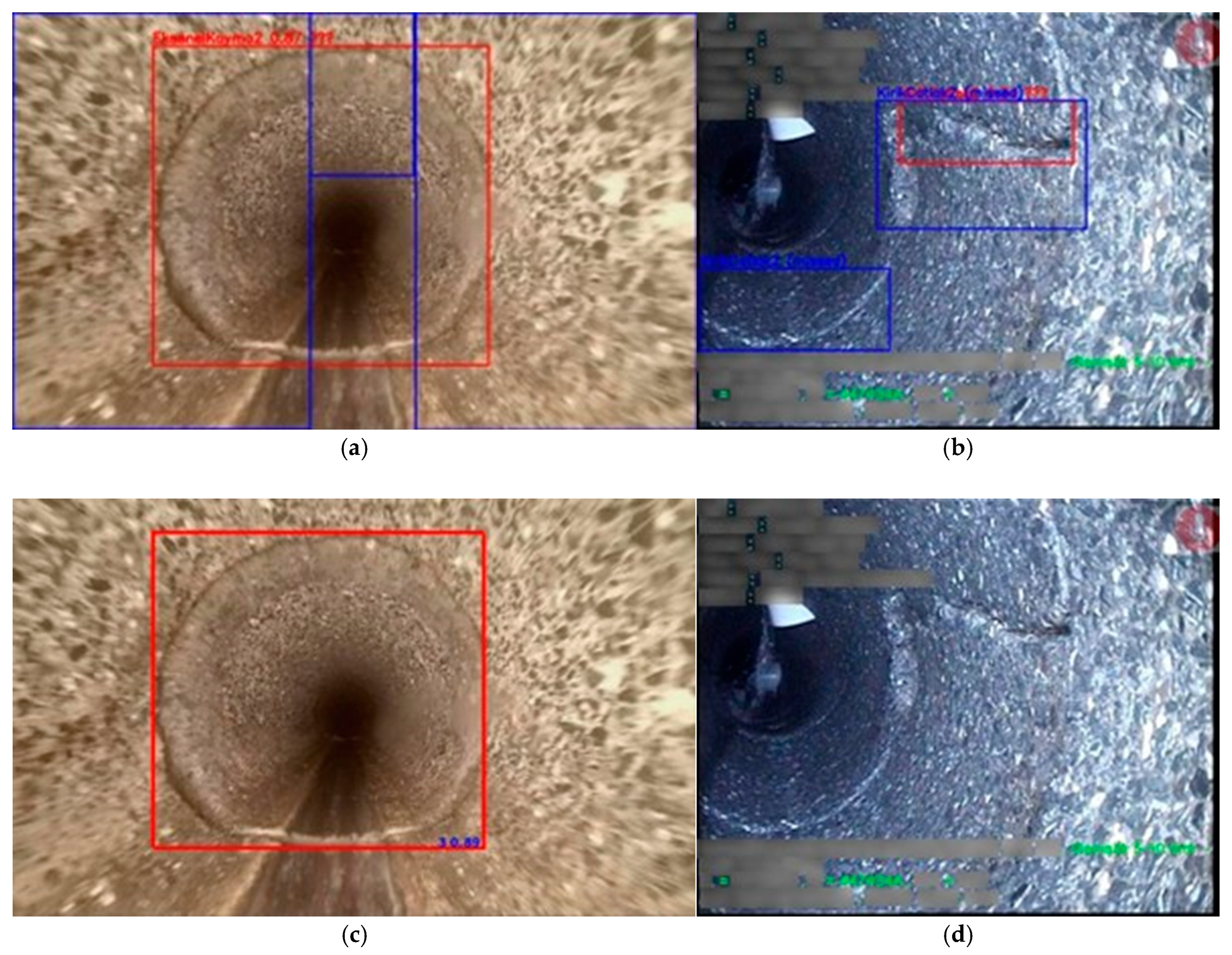

The analysis also revealed common and model-specific failure modes, providing insight into the remaining challenges of automated sewer defect detection. A recurring error involved misclassifying Pipe Surface Damage as Displaced joint by YOLOv12l (

Figure 6a). This suggests the model’s reliance on similar visual patterns (e.g., linear features, shadows) for both classes, indicating a potential need for more discriminative training examples or architectural adjustments to better separate these classes. The “Crack/Breaks/Collapses” class proved to be the most challenging, with both models occasionally failing to detect fine, thin cracks entirely (

Figure 6c,d).

4. Practical Integration and GIS-Based Deployment

The choice between model architectures has direct consequences for real-world deployment, extending beyond mere accuracy metrics to practical considerations of integration and computational efficiency. If the primary goal is to minimize missed defects and ensure the highest possible detection rate across diverse and challenging conditions, RT-DETR v2 is the unequivocal choice. Its stability and high recall make it suitable for offline, server-based processing of inspection data where computational resources are not constrained. If the system must run on embedded hardware such as NVIDIA Jetson or Raspberry Pi (Sony UK Technology Centre, Pencoed, UK) within the inspection vehicle itself, or on standard office computers without specialized GPUs, the YOLO family provides a significant advantage. Their smaller model size, higher frames-per-second throughput, and lower computational demands make them the more practical and deployable option for in-field and desktop applications.

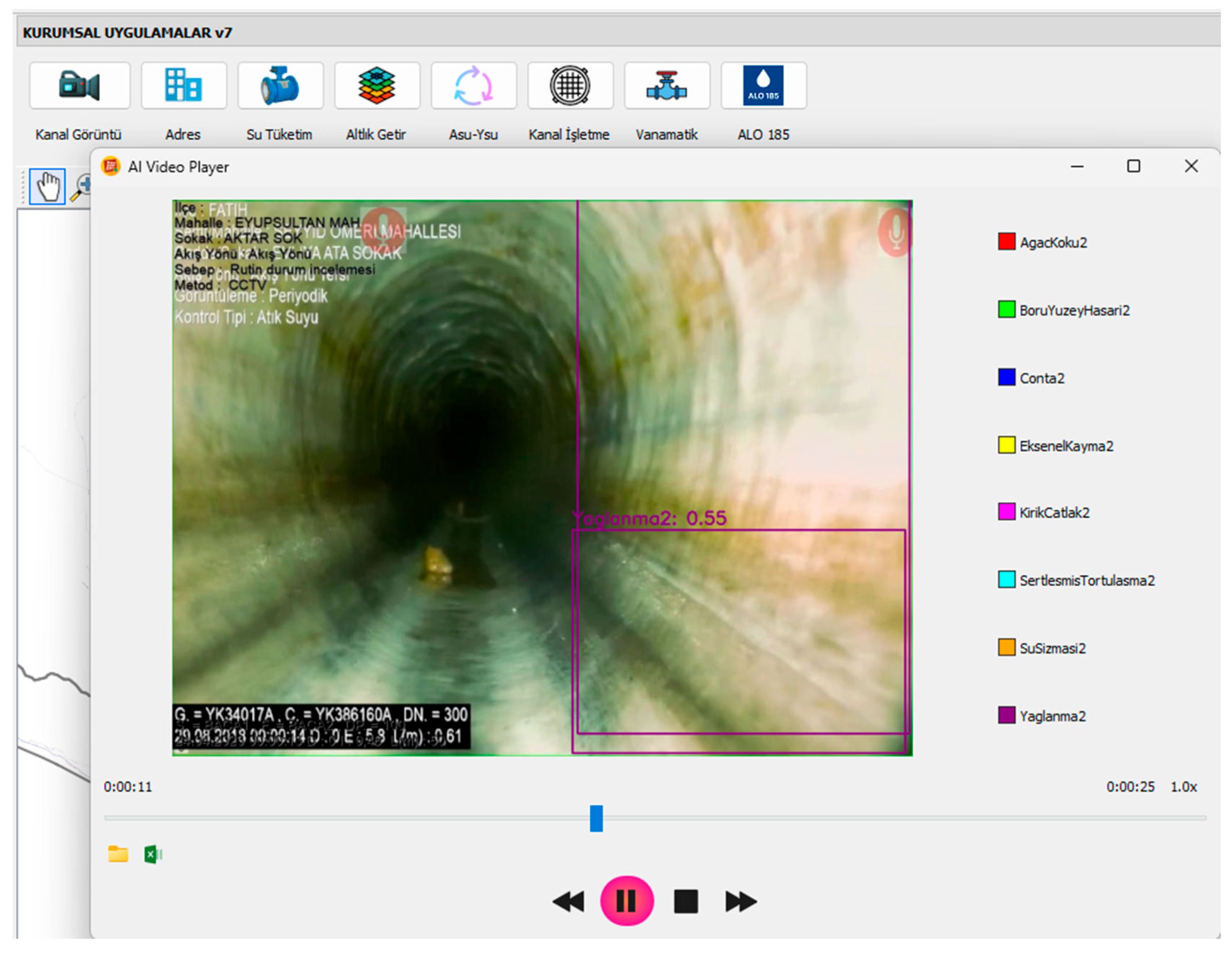

To demonstrate practical integration, a Python 3.12-based application within the QGIS 3.34 environment was developed. This tool bridges the gap between raw video analysis and actionable asset management insights. Inspection videos and their metadata, stored in a PostgreSQL 17.4 database and NextCloud Hub 9 (30.0.8) cloud storage, are queried and retrieved directly within the application. The selected pre-trained model, converted to the standardized ONNX format for framework interoperability, processes the video. Each frame is analyzed using OpenCV 4.11, with defects identified and annotated with colored bounding boxes and labels in real-time.

The application features a custom video player interface that displays the annotated video stream. A legend assigns a unique color to each defect class for easy identification. As the video plays, detection data is automatically compiled and exported to a comprehensive Excel report for further analysis and record-keeping.

Figure 7 shows the graphical user interface of the developed QGIS 3.34 plugin, with real-time defect detection on a video stream supported by a legend and controls.

This system directly addresses key industry challenges. First, computational constraints were validated empirically. While YOLO-n and -s models could run in real-time on a standard Intel i7 CPU, larger models such as YOLO-m/l/x and RT-DETR required a dedicated GPU to process 30 FPS video without lag. This justifies the recommendation of smaller YOLO variants for widespread deployment on municipal hardware. Second, the tool significantly reduces the manual workload for inspectors by automating the process and mitigating human error and fatigue associated with reviewing hours of footage. Third, the application supports the democratization of expertise by providing visual annotations and automated reports, enabling less experienced personnel to conduct thorough and accurate inspections and making expert-level assessments more accessible.

The success of this integrated application is directly proportional to the accuracy of the underlying deep learning model, underscoring the importance of the comparative analysis presented in this study. This work provides a complete pipeline, from novel dataset and model benchmarking to a functional tool ready for end-user adoption, demonstrating a direct path from research to practical infrastructure asset management.

5. Discussion

The comparative analysis of YOLO and RT-DETR models highlights both the progress and the persistent challenges in automating sewer defect detection. This section interprets the results within the broader context of automated infrastructure inspection and discusses the implicit ions for practical deployment. The influence of pipe material on sewer system performance has been widely acknowledged in the literature. While management-oriented guidelines such as the EPA’s CMOM framework emphasize operational and maintenance practices rather than material properties [

49], technical studies have highlighted the critical role of material type in pipe deterioration. Ref. [

8] noted that failures in concrete, clay, and plastic pipes exhibit different modes and rates of deterioration, underlining the importance of material-specific maintenance strategies. More recently, ref. [

50] conducted a state-of-the-art review and concluded that pipe material, along with age, diameter, and length, represents one of the most significant predictors of sewer pipe condition. Their review also revealed that international condition rating systems including the WRC in the United Kingdom, PACP in the United States, NRC in Canada, and WSAA in Australia, incorporate material type as a fundamental input in deterioration models. These findings suggest that including pipe material as a variable in defect detection and condition assessment studies could enhance the robustness of predictive models and provide a more comprehensive discussion of infrastructure performance across different countries.

Building upon these insights from the literature, our experimental findings further demonstrate the comparative strengths of the evaluated models. Our experimental results reveal that although both YOLOv12l and RT-DETR v2 exhibit competitive performance, RT-DETR v2 demonstrates superior outcomes in terms of recall and mAP, underscoring its suitability for reliable defect detection in real-world scenarios. These findings align with recent studies emphasizing the advantages of transformer-based detection models over conventional CNN-based approaches, thereby reinforcing the potential of RT-DETR v2 as a robust framework for practical applications.

5.1. Model Performance and Architecture Comparison

Across all metrics, RT-DETR v2 consistently delivered superior recall and robustness, particularly in complex or visually degraded scenes. Its transformer-based encoder–decoder architecture, equipped with multi-head self-attention, enabled the modeling of global context, allowing the detection of defects that were occluded, poorly lit, or spatially spread across the image. This capability proved especially beneficial for operational defects such as roots and settled deposits, where local feature cues alone are insufficient. In contrast, YOLOv12l, the best-performing CNN-based variant, excelled in well-defined scenarios with clear structural patterns, offering cleaner outputs with fewer false positives. However, its reliance on local receptive fields limited its ability to generalize under challenging conditions, as evidenced by its lower recall rates.

The choice between model architectures has direct consequences for real-world deployment, extending beyond mere accuracy metrics to practical considerations of integration and computational efficiency. If the primary goal is to minimize missed defects and ensure the highest possible detection rate across diverse and challenging conditions, RT-DETR v2 is the unequivocal choice. Its stability and high recall make it suitable for offline, server-based processing of inspection data where computational resources are not constrained. If the system must run on embedded hardware such as NVIDIA Jetson or Raspberry Pi within the inspection vehicle itself, or on standard office computers without specialized GPUs, the YOLO family provides a significant advantage. Their smaller model size, higher frames-per-second throughput, and lower computational demands make them the more practical and deployable option for in-field and desktop applications.

5.2. Persistent Challenges and Limitations

Despite these advances, both model families consistently struggled with the Crack/Breaks/Collapses class. The normalized confusion matrix for YOLOv12l and RT-DETR-v2 revealed an accuracy of only 0.58 and 0.60, respectively, for this category, with cracks frequently misclassified as background (

Figure 8). A similar challenge arose for the Attached deposits class, with a background confusion rate of 0.27 and 0.26 for YOLOv12l and RT-DETR-v2, respectively. These errors are not solely attributable to model deficiencies but instead reflect the inherent difficulty of the task. Fine cracks, attached deposits, and subtle infiltration signatures often share visual characteristics with pipe textures, stains, water streaks, or reflections, making them difficult to distinguish even for human inspectors.

To further evaluate the generalizability of our models, we also conducted experiments using the publicly available Sewer-ML dataset, which represents one of the largest collections of sewer inspection imagery to date. Since the label annotations of the Denmark dataset were not made publicly available, a direct comparison with the benchmark values reported in the study by [

37] could not be performed. However, upon inspection of the dataset, it was observed that several images are of very low resolution. In particular, defects such as cracks and fractures are challenging to detect in low-resolution images. Moreover, it would be beneficial for the Denmark dataset to be reviewed by domain experts and for certain images to be removed. In some cases, defects cannot be identified even by the human eye, or the images suffer from issues such as blurriness. In addition, defects that can only be inferred indirectly, such as infiltration, pose further challenges.

As shown in

Figure 9, YOLO failed to detect root intrusions, whereas RT-DETR correctly identified them. Surface damage was localized as a broader, single area by RT-DETR. Intruding sealing material, settled deposits, and attached deposits were successfully detected by both models. Infiltration, however, was consistently misclassified as surface damage in both cases. For cracks, YOLO detected only the one on the left side of the image, while RT-DETR failed to identify any of them.

5.3. Domain-Specific Challenges

Beyond architecture-specific observations, the study brings attention to domain-specific challenges of sewer inspection imagery. Poor image quality resulting from low-resolution cameras, blur, insufficient lighting, or environmental factors such as mud and condensation directly limit detection accuracy. The complex background of sewer walls where stains, surface irregularities, and deposits overlap with actual defects, makes accurate bounding box generation difficult. Many defects are small or ambiguous, requiring models capable of fine-grained detail extraction. Moreover, the high inter-class similarity, such as between attached deposits and deposits, exacerbates false positives. The imbalanced class distribution in the dataset further compounds these issues, with underrepresented defect types leading to unstable per-class performance.

The quality of labeling also emerged as a significant factor. Operator-level analysis indicated that human annotators achieved only 50–60% detection accuracy, partly due to the volume of video data and the inherent difficulty of distinguishing subtle defects. Mislabeling, class grouping (e.g., cracks, breaks, collapses treated as one class despite their variability), and inconsistent annotation standards reduced the models’ ability to generalize. For example, excessive grouping of defect types contributed to poor Crack/Breaks/Collapses performance, while reflection-induced false detections highlighted the need for stricter imaging protocols, such as limiting robot speed to reduce vibration and blur.

Another limitation concerns computational requirements. While YOLO-n and YOLO-s variants successfully ran in real time on CPU-only systems, larger YOLO models and all RT-DETR variants required GPU acceleration to maintain frame rates compatible with live inspection. This reflects a broader trade-off: the transformer-based models offer superior accuracy but impose higher costs in terms of training time, inference latency, and hardware demands. By contrast, the YOLO family, with its smaller model sizes and efficient inference, remains more deployable for municipalities with limited computing resources. Thus, the choice of models must balance accuracy with practical constraints, and future research should investigate methods such as model compression, quantization, and knowledge distillation to bridge this gap.

5.4. Performance Comparison with State-of-the-Art

To contextualize our results within the broader research landscape, we compared our best-performing models against recent state-of-the-art approaches on sewer defect detection for similar defect classes where AP values are reported. While direct comparisons are limited by dataset differences, several studies provide relevant benchmarks.

Table 8 summarizes reported performances across different geographic locations, model families, and defect types, highlighting the diversity of methods and results in this domain.

The comparative overview in

Table 8 shows several key trends. First, there is considerable variability across reported performances, reflecting differences in datasets, labeling schemes, and evaluation protocols. For example, refs. [

17,

19] both report high AP values above 83% for roots and settled deposits using Faster R-CNN and improved YOLOv3, respectively, though these were tested on datasets from the United States under relatively controlled conditions. More recent work using the Sewer-ML dataset from Denmark [

15,

16,

26,

53,

54] consistently reports strong results above 90% AP for structural defects such as displaced joint and roots, suggesting that the large scale and standardized labeling of Sewer-ML may facilitate higher model performance.

Second, transformer-based architectures have begun to appear in this field, with [

28,

31] demonstrating competitive results using DETR and Swin Transformer variants. While their AP values are lower than the best-performing YOLO-based models, they highlight the potential of attention mechanisms to capture contextual information.

Third, our models’ performances are broadly consistent with reported ranges in the literature, despite being evaluated on the newly introduced ISWDS dataset, which presents more challenging imaging conditions typical of Istanbul’s sewer network. For instance, our YOLOv12l achieved 93.4% AP for roots and 90.8% for displaced joint, aligning with top results from Sewer-ML-based studies, while our RT-DETR v2 excelled in infiltration (80.5%) and attached deposits detection (90.8%), categories that have received comparatively less attention in prior works.

Taken together, these comparisons suggest that our dataset poses a challenging yet realistic benchmark for sewer defect detection. While absolute AP values are slightly lower than those achieved on Sewer-ML, the relative performance of YOLO and RT-DETR aligns with broader trends in the field. This reinforces the value of ISWDS as a complementary dataset to existing benchmarks and underscores the robustness of our findings across defect categories.

5.5. Broader Applicability and Future Directions

While our experimental results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of both YOLOv12l and RT-DETR v2, their integration into real-world sewer inspection practice remains challenging. Fine-grained defects such as cracks, attached deposits, and subtle infiltration signatures proved particularly difficult to detect, primarily due to their strong visual similarity with background textures, stains, and reflections. These challenges are further compounded by the quality of image acquisition and annotation, as operator-level analysis indicated that even human inspectors achieved only 50–60% accuracy in such cases. In addition, the trade-off between accuracy and computational feasibility represents a practical barrier: RT-DETR v2 provides superior recall and robustness under degraded conditions but requires GPU acceleration, whereas YOLO models, despite being less reliable in occluded or poorly lit scenarios, remain more practical for embedded or resource-constrained environments due to their lighter architectures and higher throughput. To overcome these limitations, future research should focus on stricter imaging protocols to reduce noise and blur, domain-specific data augmentation, and improved annotation practices, along with the exploration of lightweight architectures, model compression, quantization, and hybrid human–AI workflows. These measures would not only mitigate current constraints but also enhance the applicability, scalability, and robustness of automated defect detection systems in operational environments.

Beyond model performance, we demonstrate the translational impact of our research by embedding the best-performing model into a QGIS 3.34-based interface. This integration is not only a practical tool but also a methodological contribution, showing how deep learning outputs can be geo-referenced, systematically logged, and incorporated into existing infrastructure management workflows. By validating the model in this operational context, we highlight its potential to reduce operator dependence, enable real-time decision-making, and support proactive asset management. Furthermore, to ensure reproducibility and facilitate future benchmarking, the trained models are openly shared on Hugging Face, providing a replicable framework for subsequent research on infrastructure AI applications.

The broader applicability of these methods extends beyond sewer systems. While the study focused on sewer infrastructure, the challenges encountered—small, ambiguous defects in noisy, low-quality imagery—are not unique to wastewater systems. Similar issues arise in drinking water networks, stormwater drainage pipes, industrial piping, and even underground cabling systems. Deep learning–based defect detection, particularly with transformer-enhanced architectures, therefore holds significant potential for cross-domain transferability. By enabling earlier detection, reducing human workload, and standardizing inspection outputs, these approaches contribute directly to smarter infrastructure management.

The success of the integrated application demonstrates a direct path from research to practical infrastructure asset management. This work provides a complete pipeline, from novel dataset and model benchmarking to a functional tool ready for end-user adoption. However, improving annotation practices, expanding dataset diversity, and introducing sub-classes for nuanced defect categories are essential steps toward closing the gap between model performance and real-world needs.

Future research could explore several promising directions. First, incorporating video-based analysis rather than frame-by-frame detection could improve temporal consistency and reduce false positives. Second, extending the methodology to include multi-task learning that combines detection, segmentation, and classification may yield richer insights into pipeline conditions. Third, conducting large-scale validation with imagery collected from diverse geographical and environmental contexts would enhance the generalizability of the models. Additionally, testing on larger and more balanced datasets is recommended to mitigate class imbalance effects.

6. Conclusions

This study represents one of the first comparative investigations applying YOLO and RT-DETR architectures to sewer inspection imagery using a novel dataset. The analysis evaluated the performance of both models across multiple defect classes, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations. While the models demonstrated strong performance in detecting sewer defects, addressing practical challenges such as fine-grained defect recognition, annotation quality, and computational feasibility remains essential for real-world deployment. By situating the findings within broader infrastructure contexts and outlining concrete directions for future research, this study provides a foundation for advancing automated defect detection from experimental evaluation toward practical, scalable, and cross-domain applications.

This study introduced the Istanbul Sewer Defect Dataset (ISWDS), comprising 13,491 expert-annotated images that capture eight major defect categories representing nearly 90% of reported failures in Istanbul’s wastewater network. Using this dataset, we conducted a comprehensive benchmark of state-of-the-art deep learning architectures, including CNN-based YOLO variants (v8 and v11 series) and transformer-based RT-DETR models (v1 and v2), under identical evaluation protocols.

Experimental results demonstrate that RT-DETR v2 consistently outperformed all other models, achieving an F1-score of 79.03% and a Recall of 81.10%, which significantly surpass the best-performing YOLO variant (YOLOv8l, F1: 74.20%, Recall: 70.72%). The transformer-based architecture proved particularly effective in detecting partially occluded and complex defects, highlighting its robustness in real-world inspection scenarios. In contrast, smaller YOLO variants, while yielding slightly lower accuracy (F1 between 72–74%), offered advantages in inference speed and computational efficiency, making them suitable for resource-constrained environments.

Beyond benchmarking, we developed a QGIS 3.34-based inspection tool that integrates the best-performing models into a real-time video processing and reporting pipeline. This practical contribution bridges the gap between research and operational deployment, enabling sewer authorities to enhance inspection efficiency, reduce manual labor, and improve early detection of infrastructure failures.

Overall, this work provides (i) the first large-scale sewer defect dataset for Istanbul, (ii) a rigorous comparative analysis of transformer and CNN-based detection models, and (iii) an operational GIS-based tool for automated inspection. Together, these contributions advance the state of the art in smart sewer management and support the development of resilient urban infrastructure systems.

YOLO demonstrated clear advantages in terms of inference speed and compatibility with resource-constrained devices, making it suitable for real-time field deployment. In contrast, RT-DETR achieved higher overall accuracy and robustness across most defect categories, albeit at the expense of increased computational cost. These findings emphasize the trade-off between efficiency and precision when selecting models for practical sewer inspection applications.

From a technical perspective, constraints related to dataset size, hardware availability, training duration, augmentation strategies, and the number of defect classes should be carefully addressed. Deploying more powerful GPU resources would also allow experiments with higher-capacity RT-DETR variants. Furthermore, comparative assessments with other advanced architectures, such as DETR derivatives and Faster R-CNN, could provide a broader benchmark. Finally, extending the analysis beyond imagery to include alternative data modalities, such as 3D point clouds captured from sewer environments, offers an exciting avenue for future exploration.

In conclusion, the integration of deep learning into sewer defect detection demonstrates strong potential for automating and enhancing inspection processes. By advancing towards multimodal approaches and leveraging increasingly powerful architectures, the level of automation and reliability in sewer monitoring can be significantly improved. To ensure reproducibility and foster future research, all trained models have been openly shared on Hugging Face.