Numerical Analysis of Seepage Damage and Saturation Variation in Surrounding Soil Induced by Municipal Pipeline Leakage

Abstract

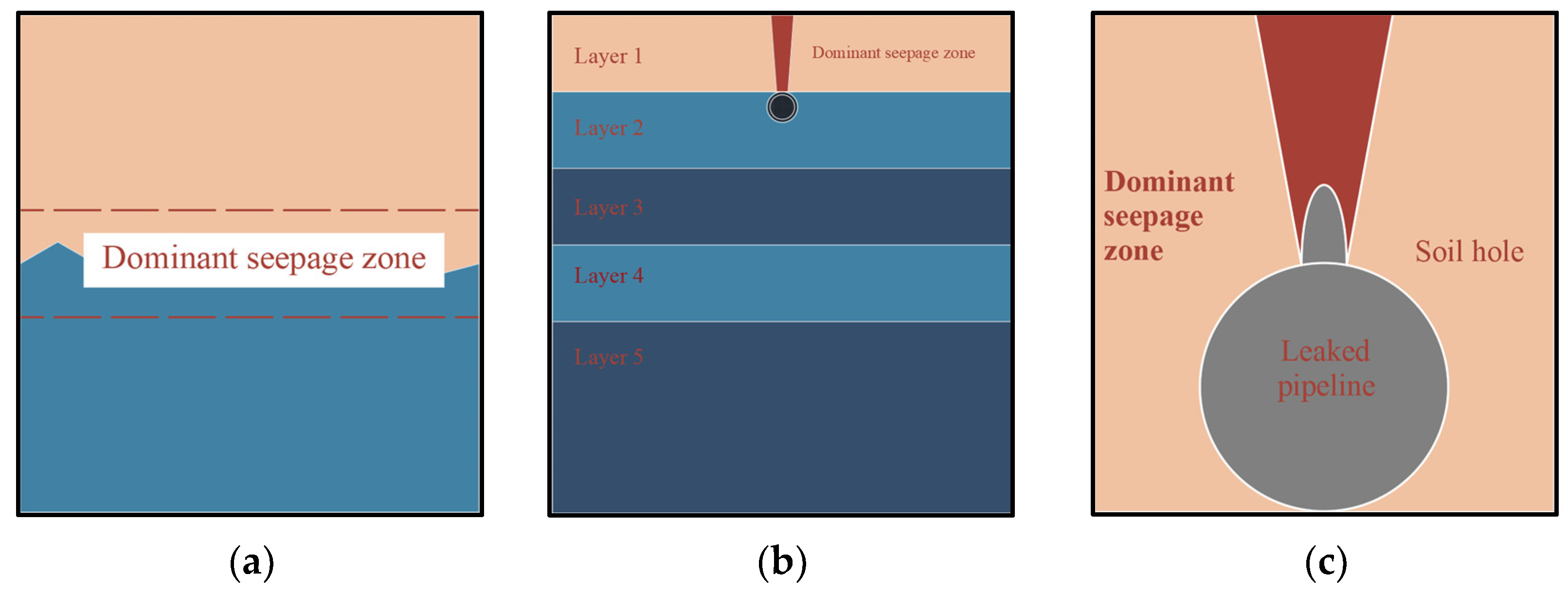

1. Introduction

2. Establishment of the Numerical Model

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

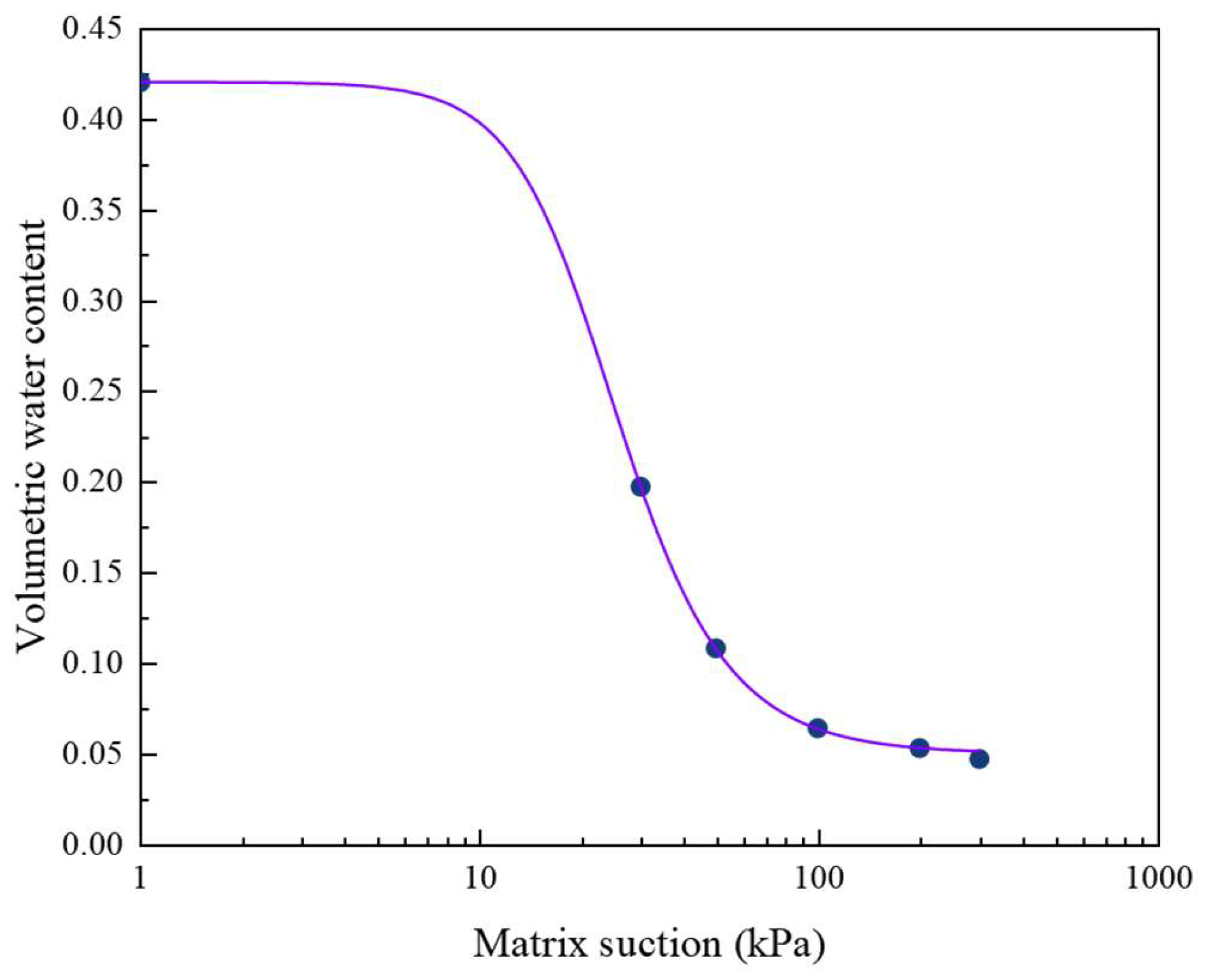

2.2. Parameter Determination

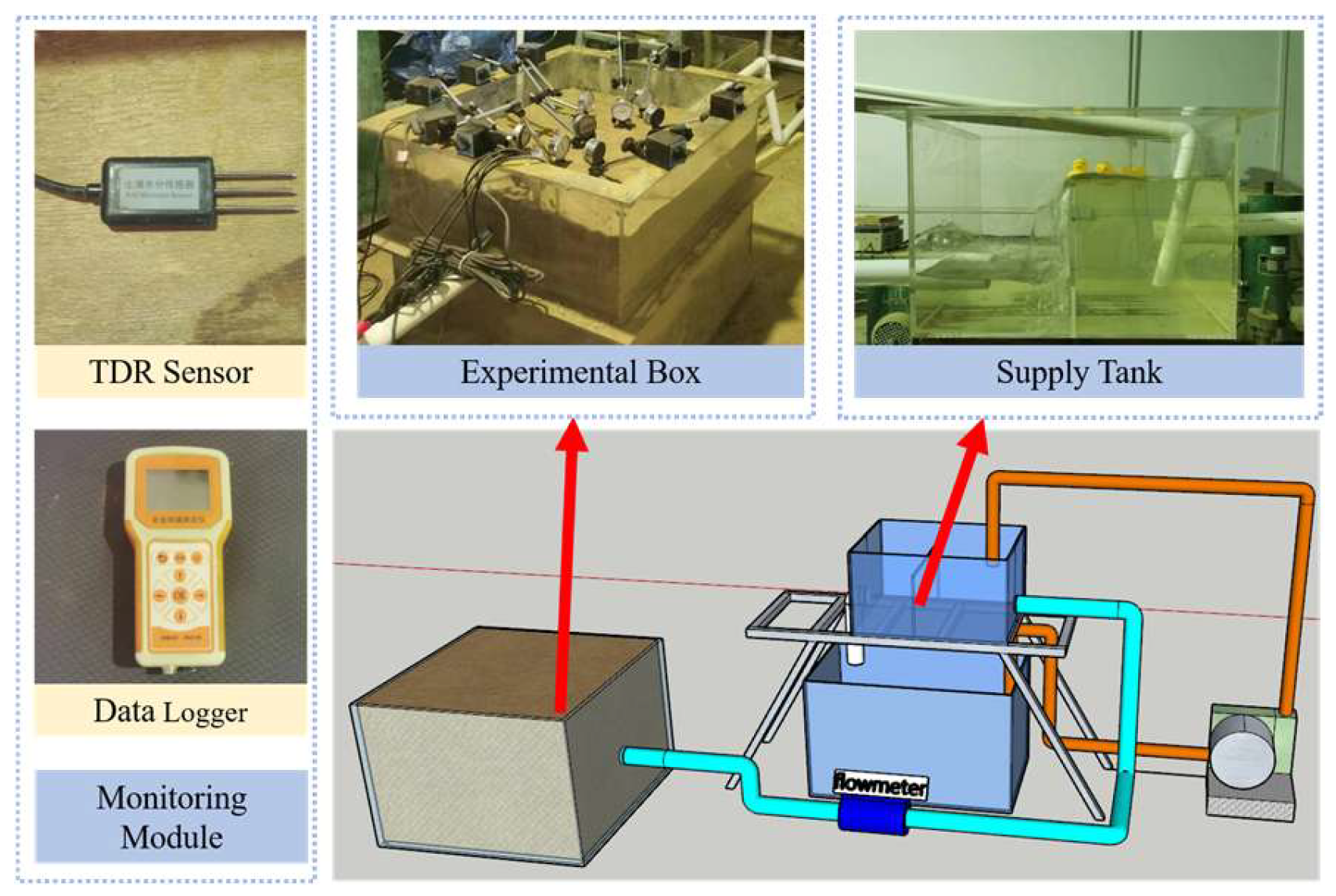

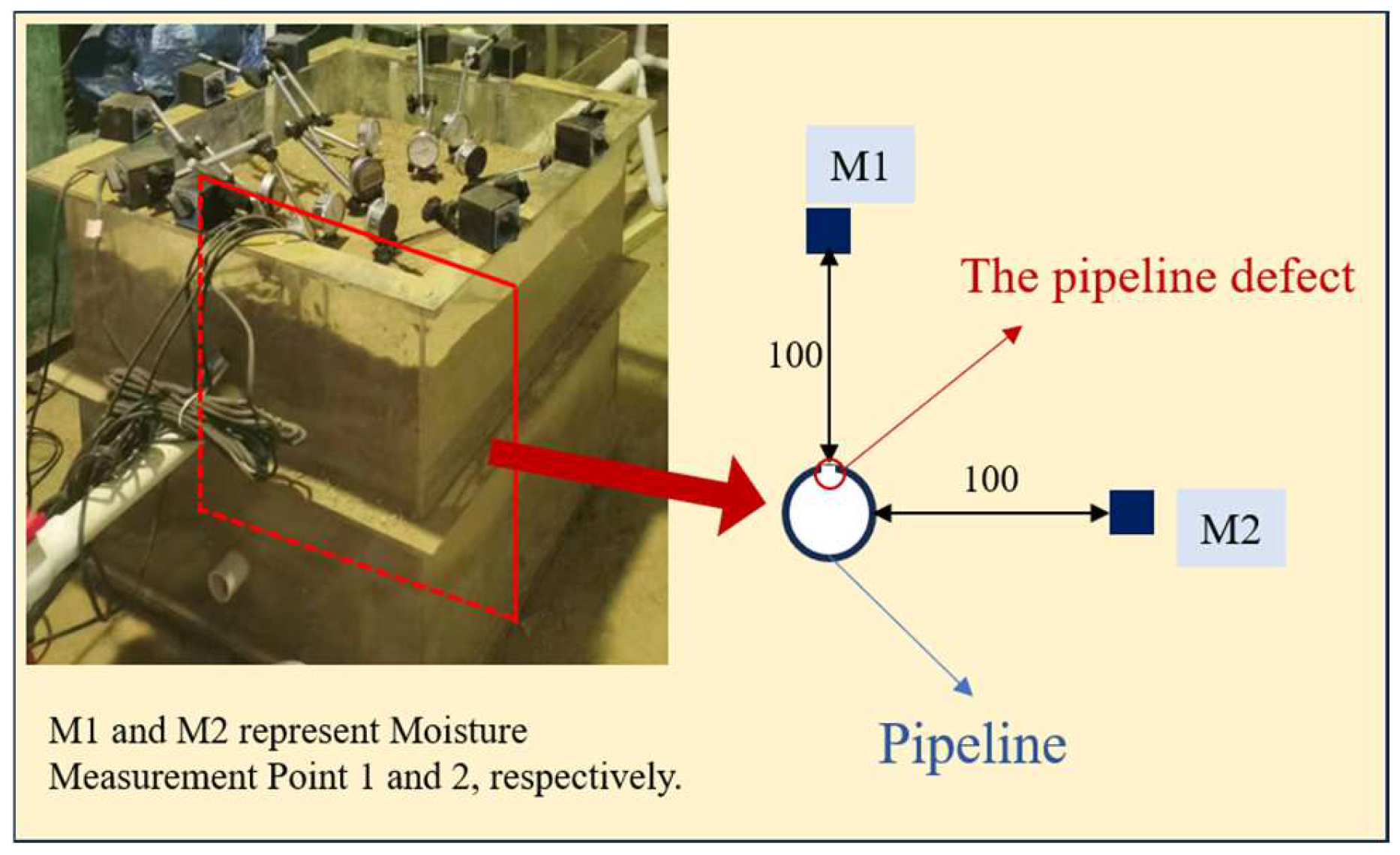

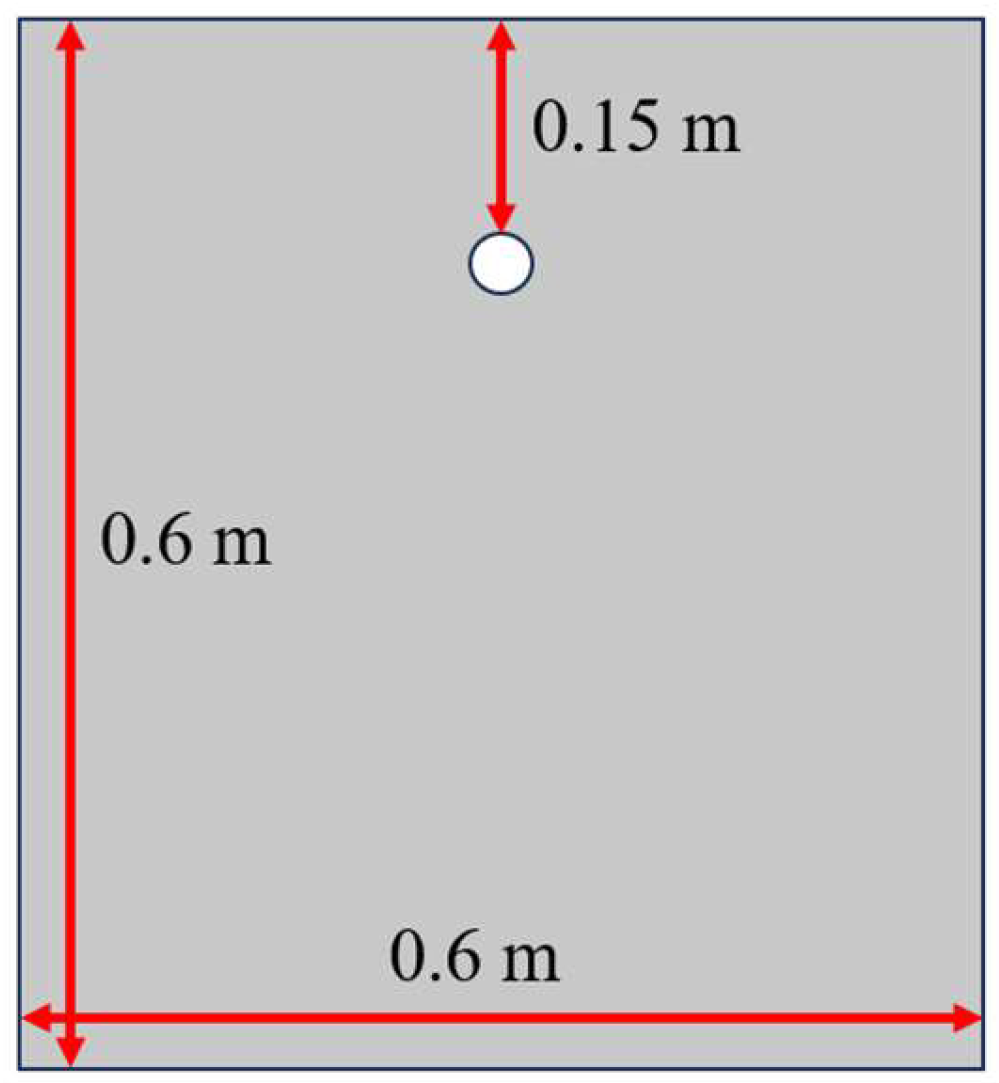

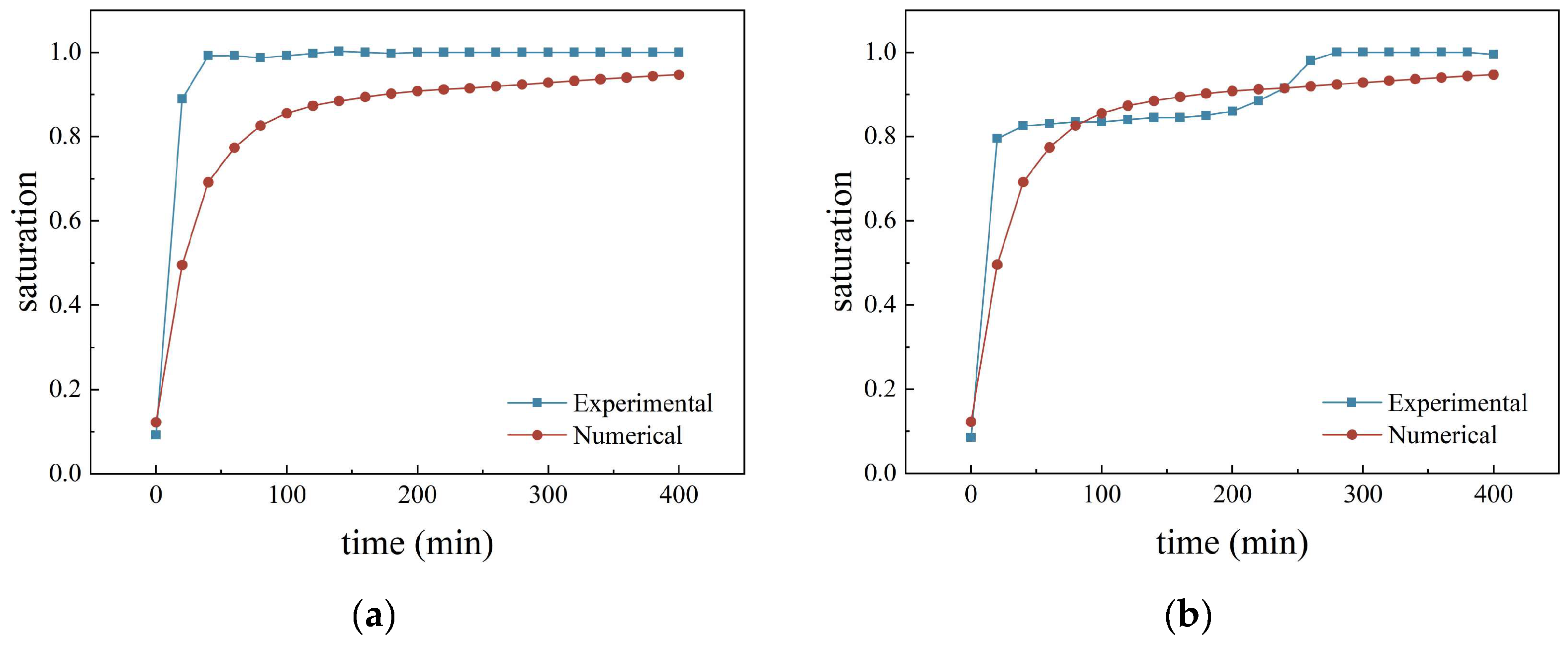

2.3. Model Validation

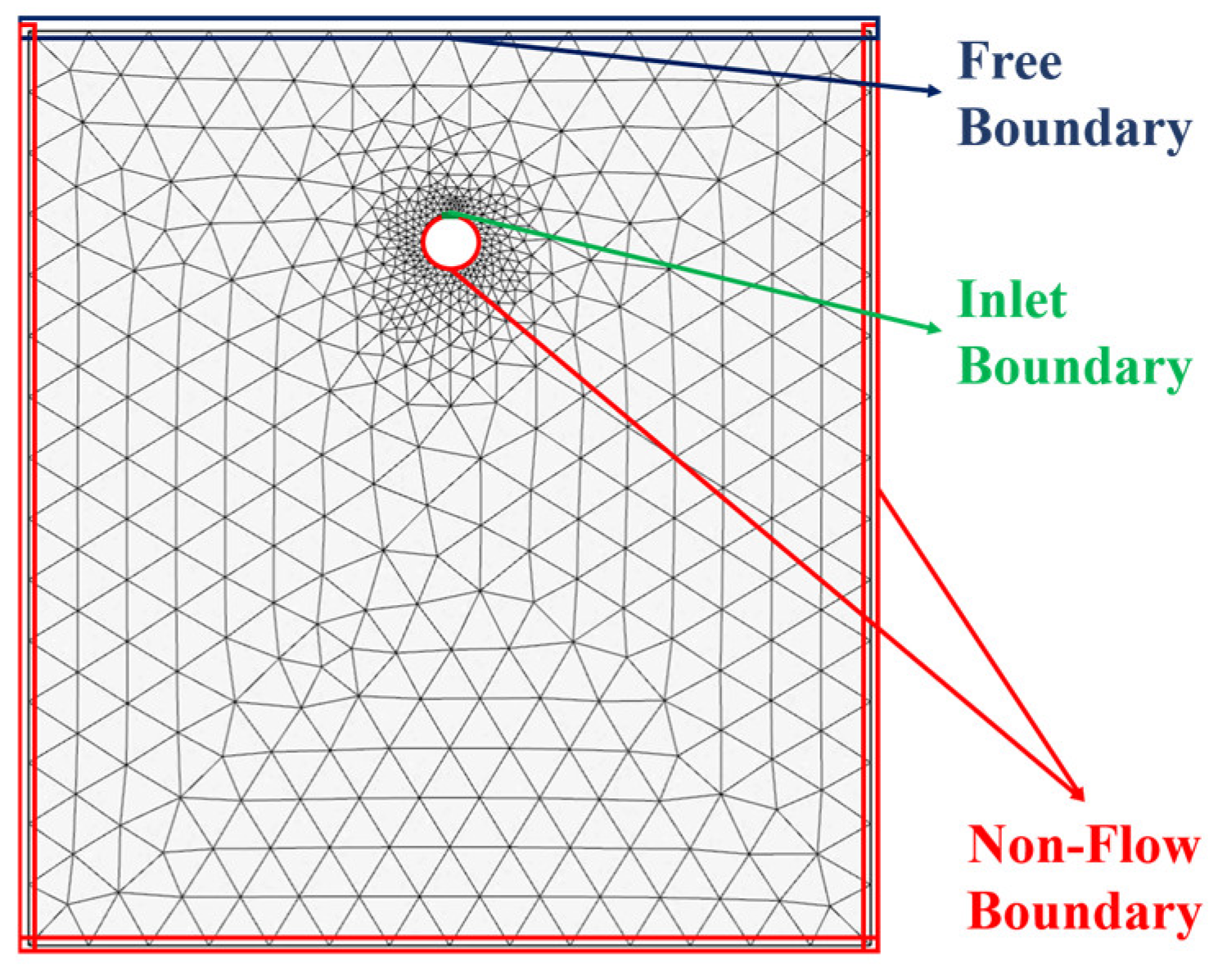

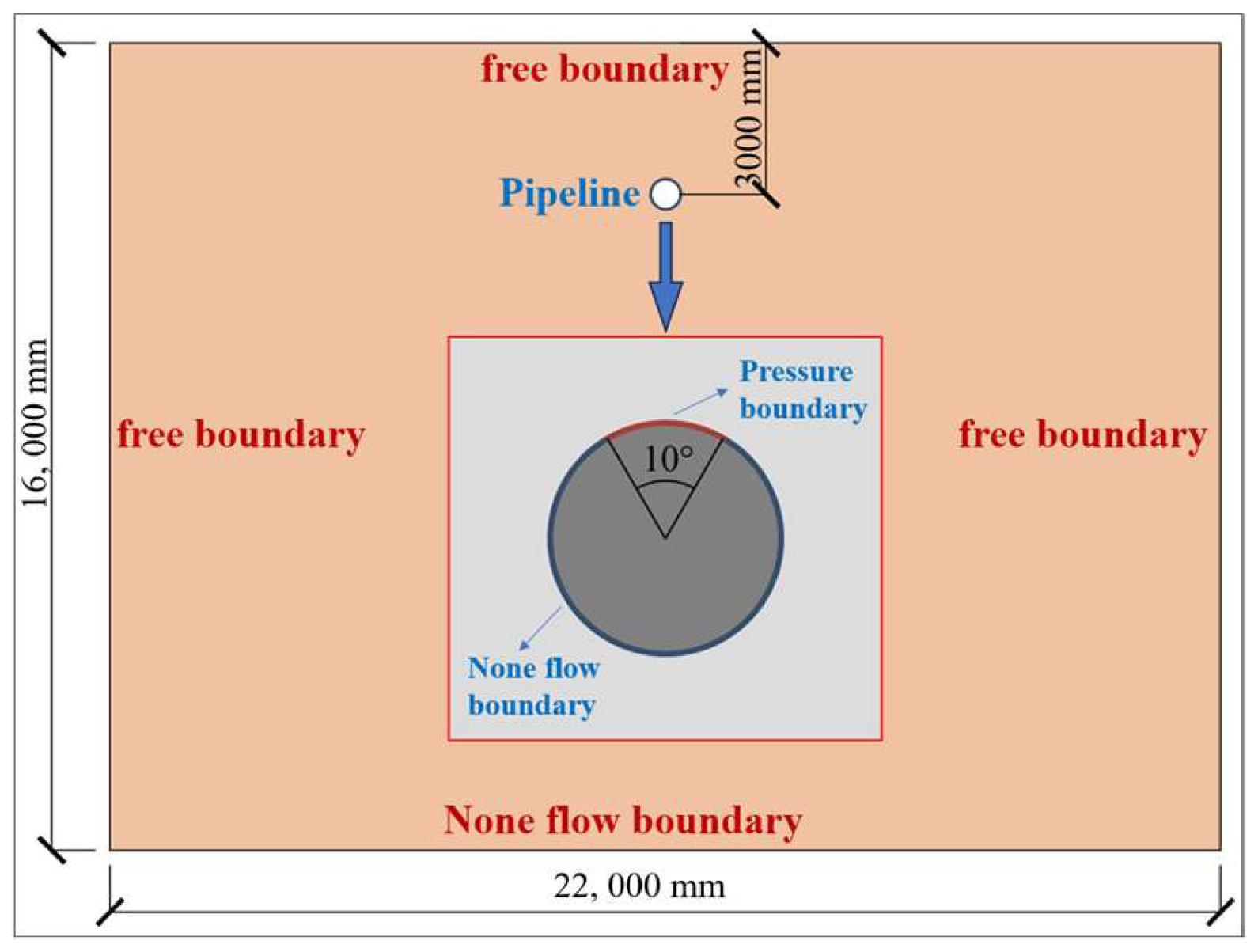

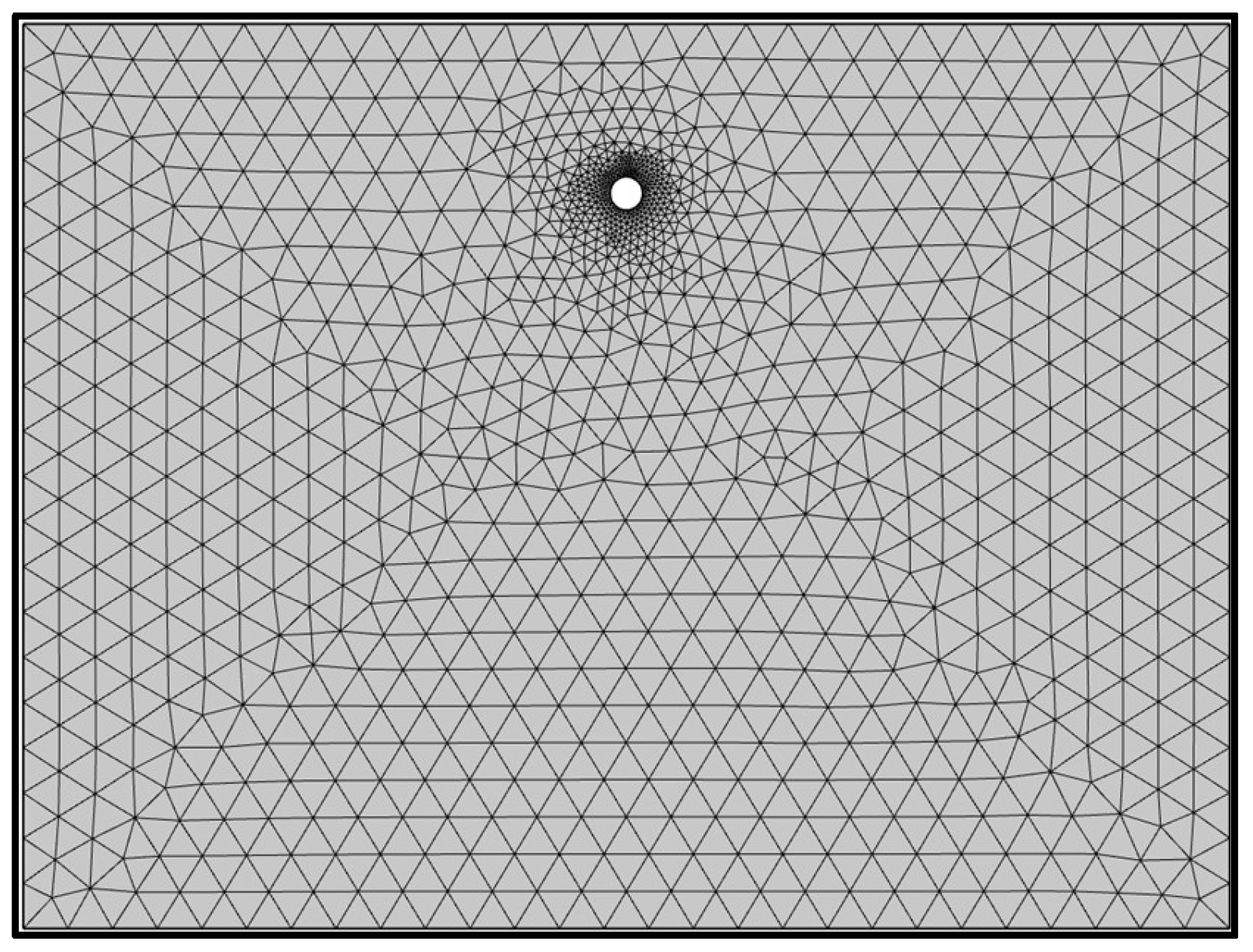

2.4. Boundary Conditions and Initial Conditions

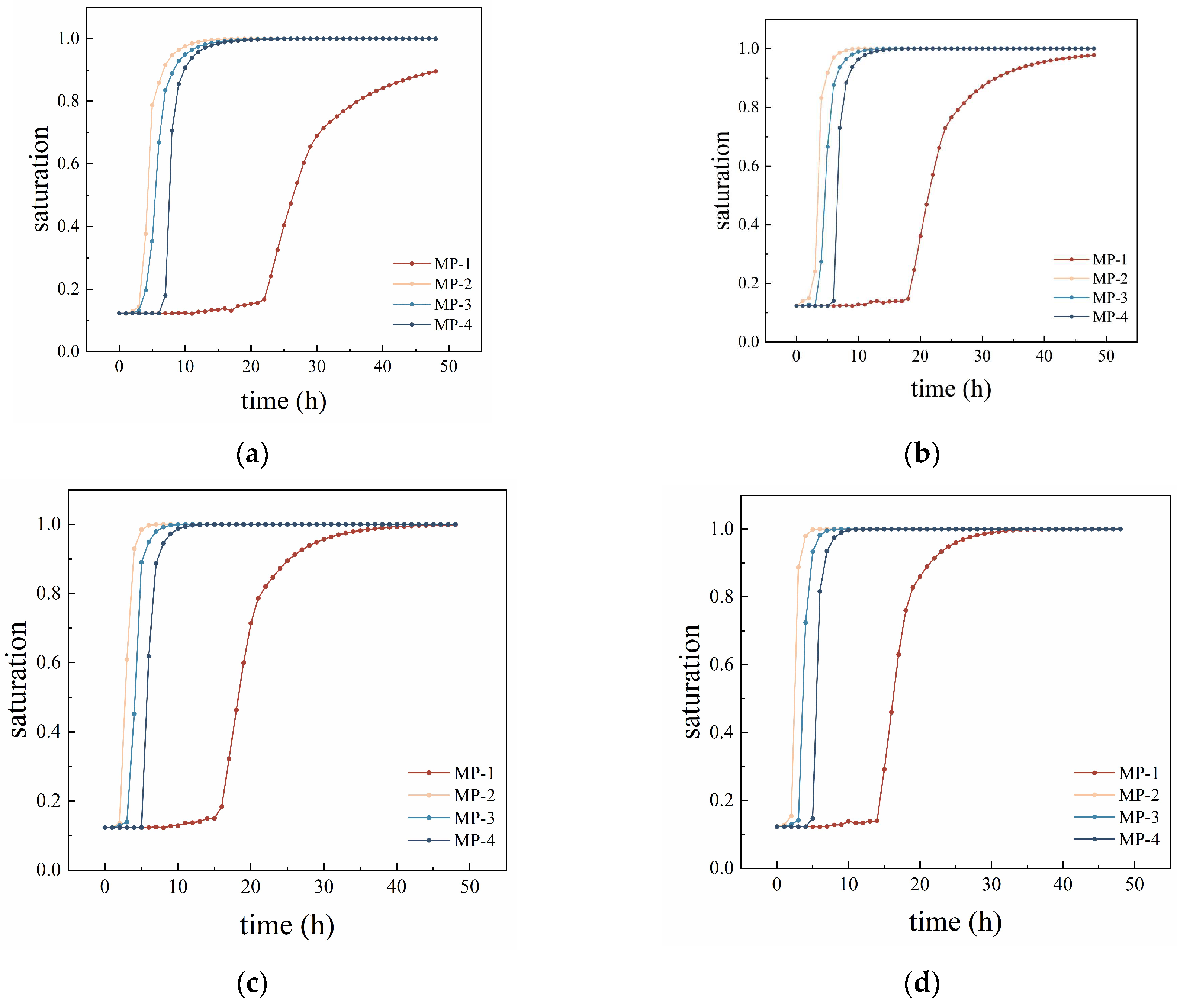

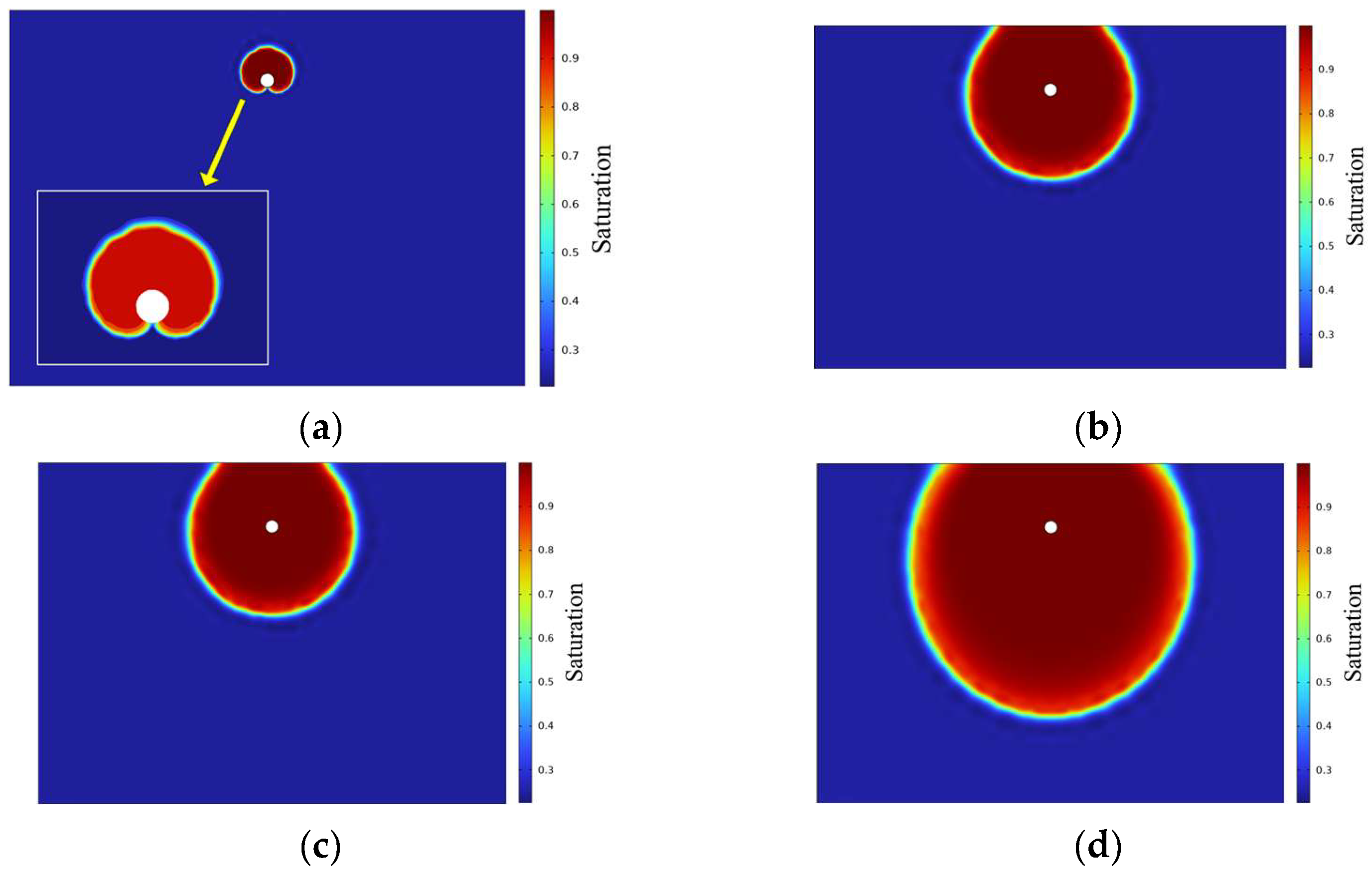

3. Numerical Simulation of Saturation Under Different Pressures

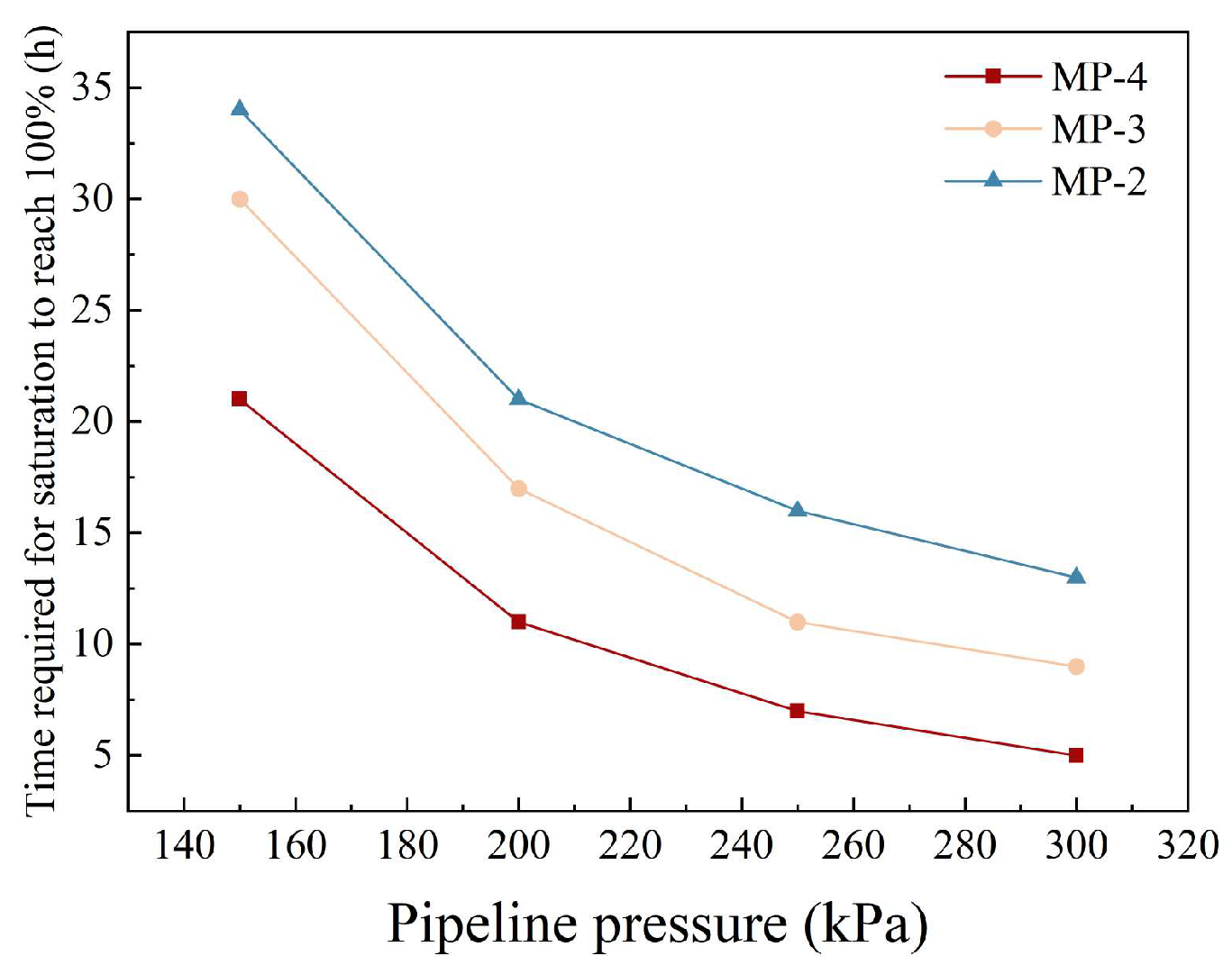

3.1. Patterns of Saturation Change at Measurement Points

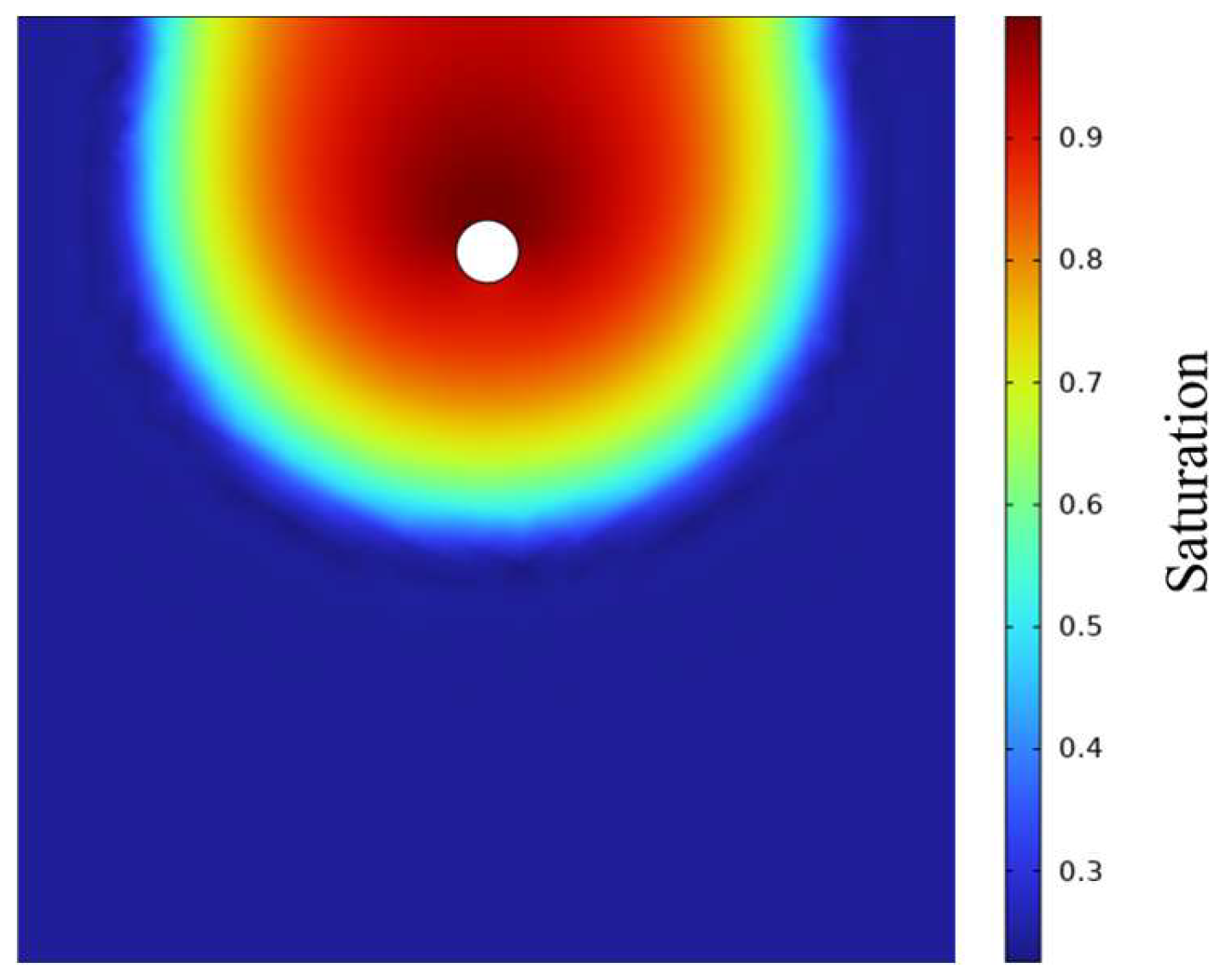

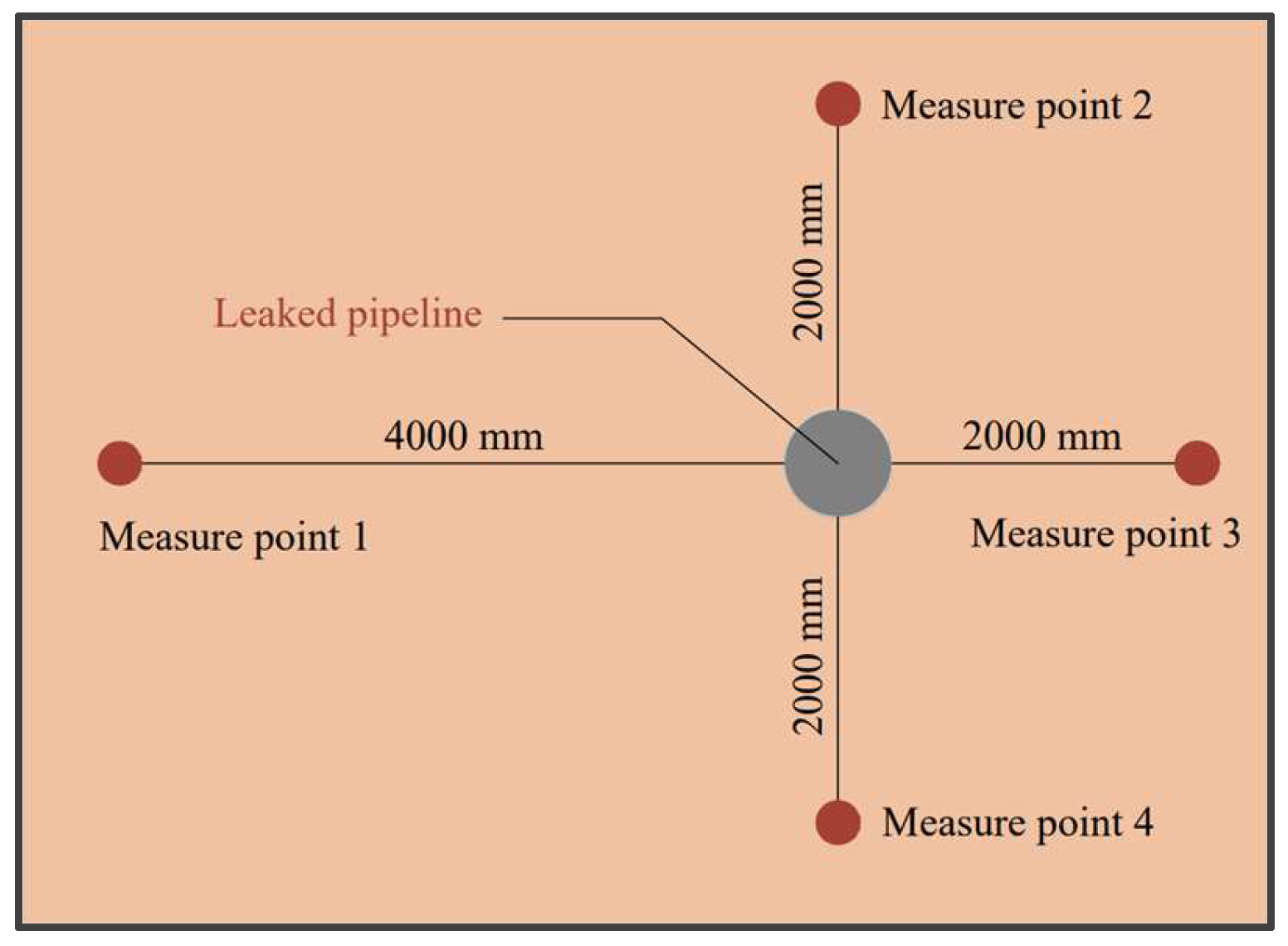

3.2. Diffusion Patterns of the Saturated Area

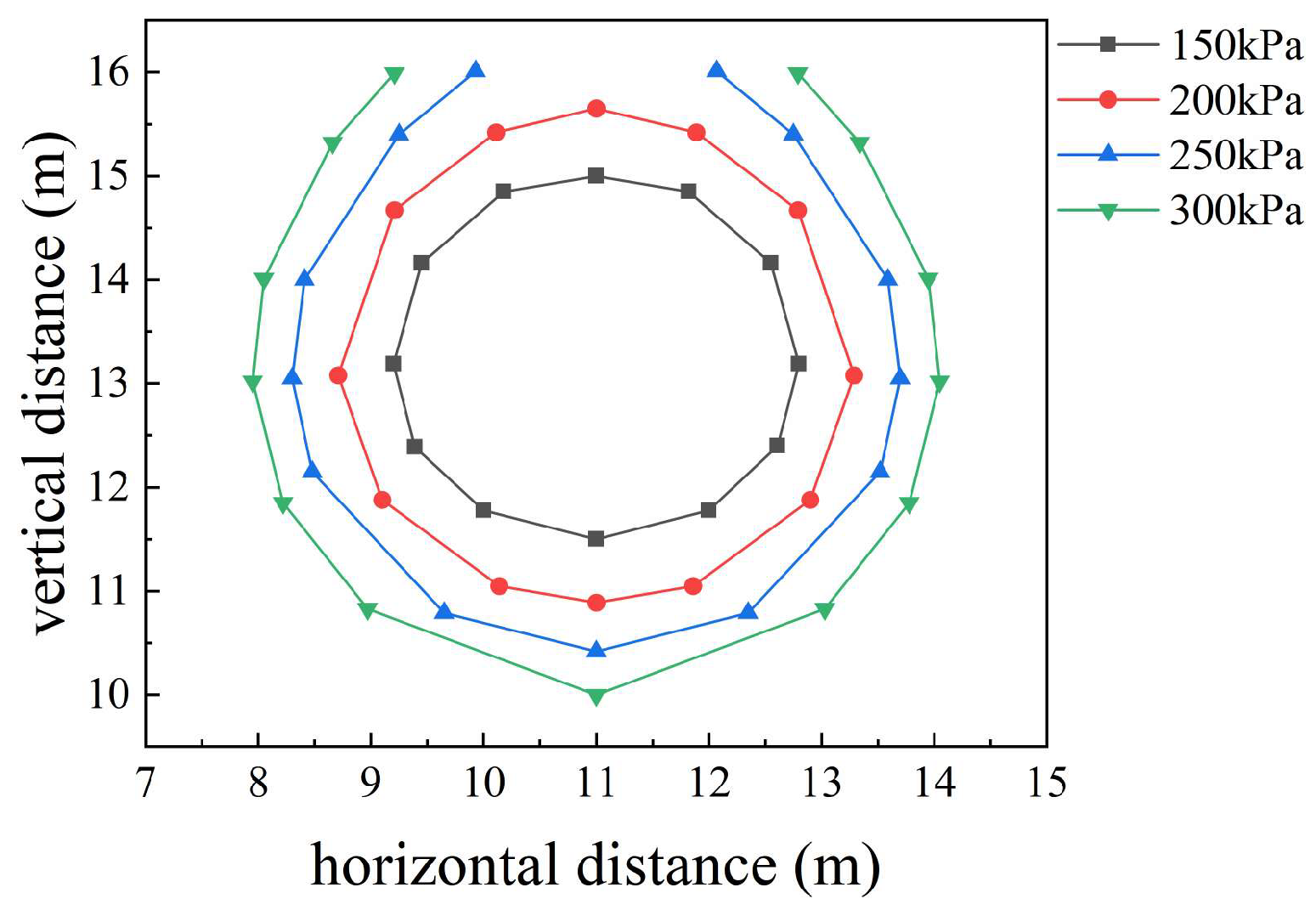

3.3. Influence of Water Pressure on the Diffusion of Saturated Areas

4. Analysis of Seepage Damage Risk Based on Numerical Results

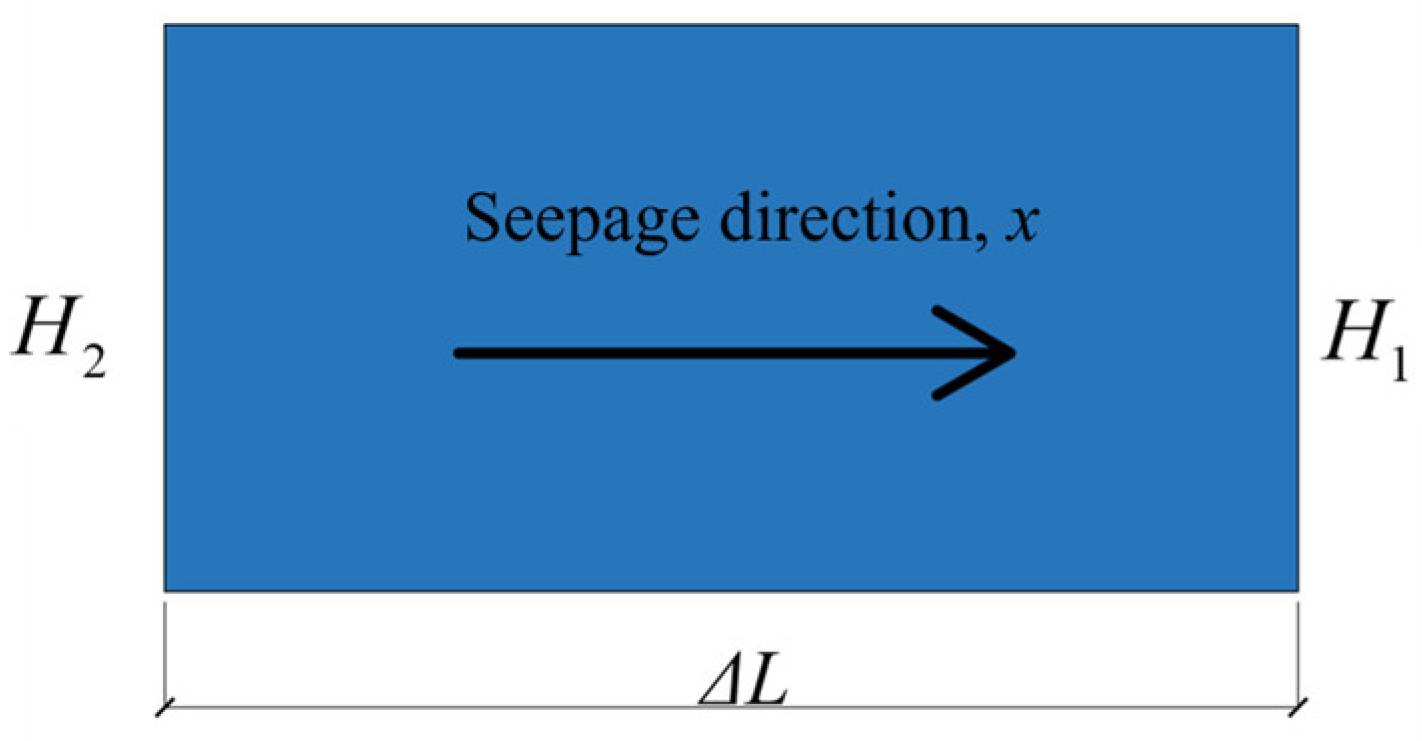

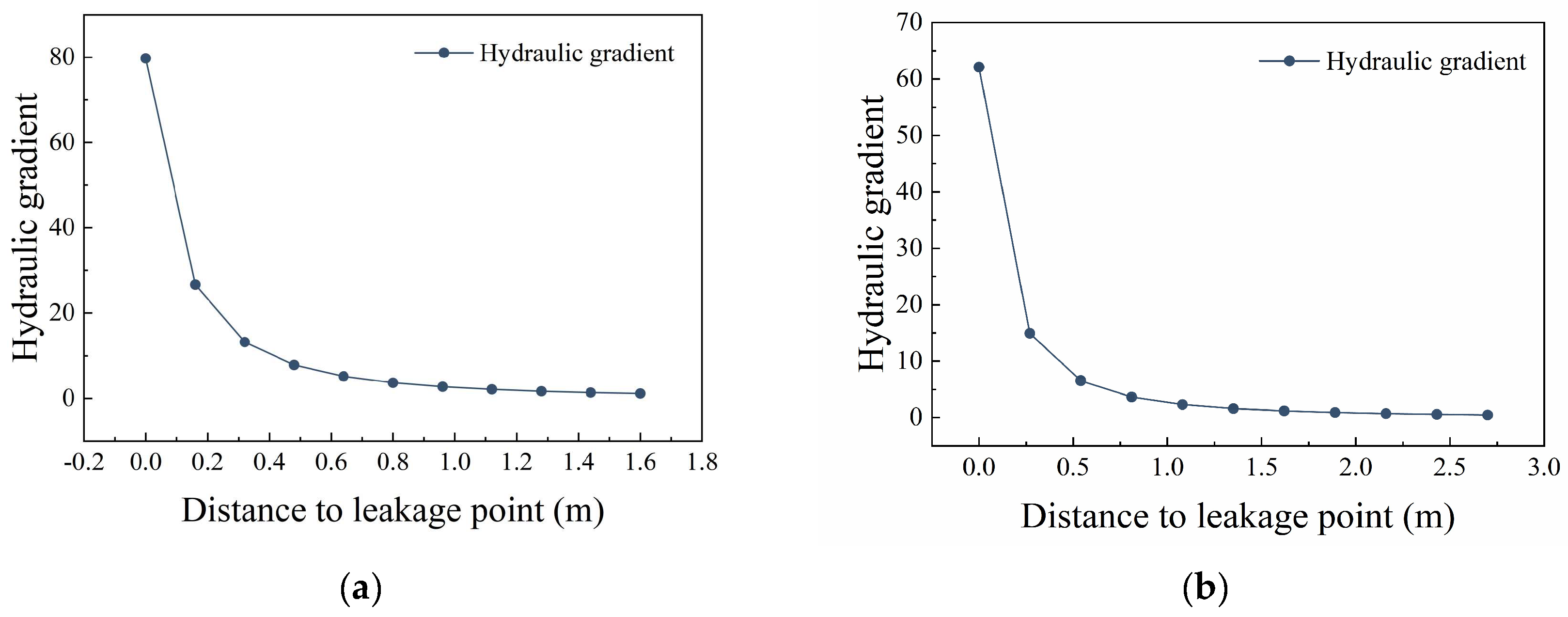

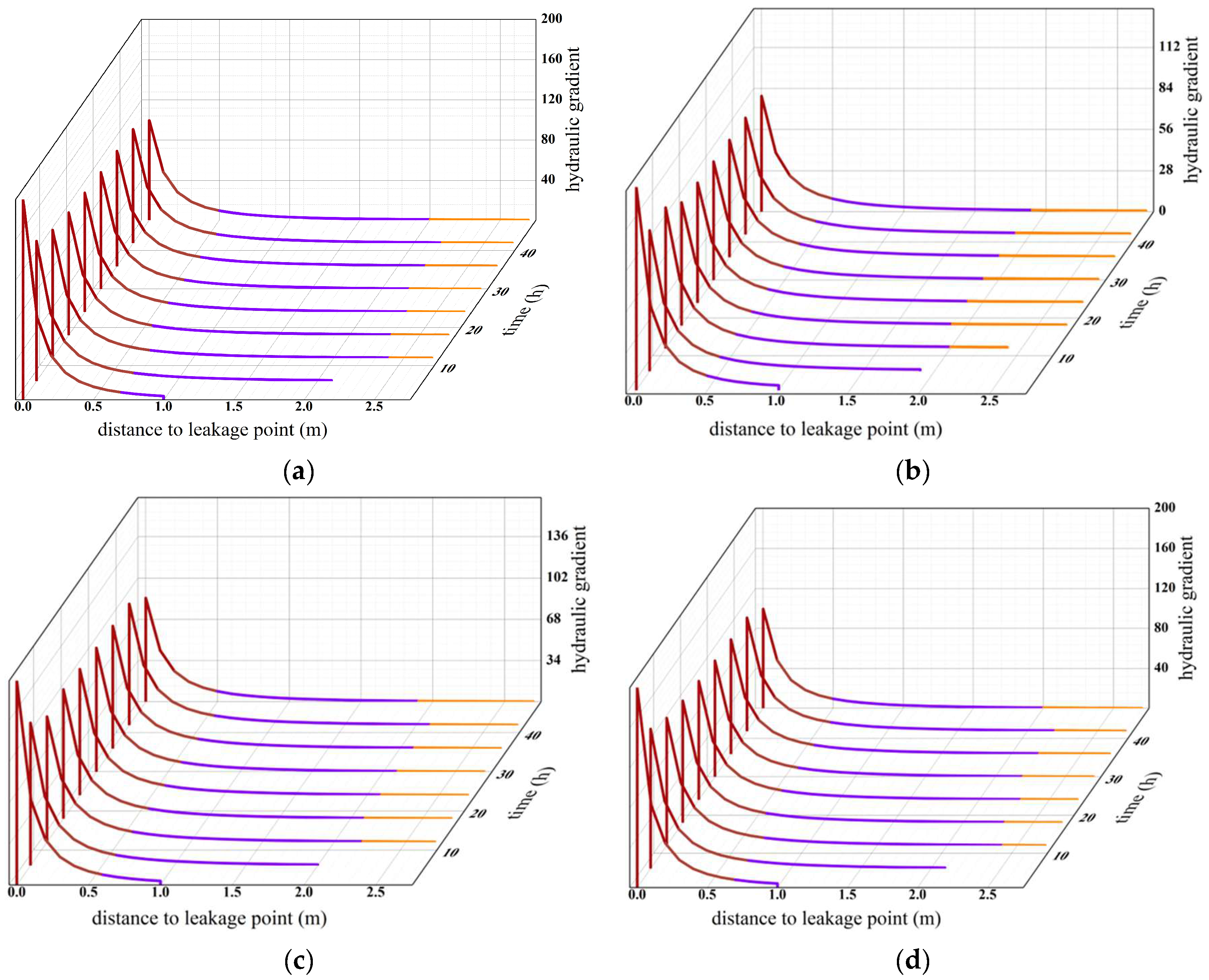

4.1. Calculation Method for Hydraulic Gradient in Seepage Areas

- (a)

- Rational function fit

- (b)

- Polynomial function fit

- (c)

- Exponential function fit

4.2. Calculation of Critical Hydraulic Gradient

4.3. Range of Seepage Damage Caused by Pipeline Leakage

5. Conclusions

- (1)

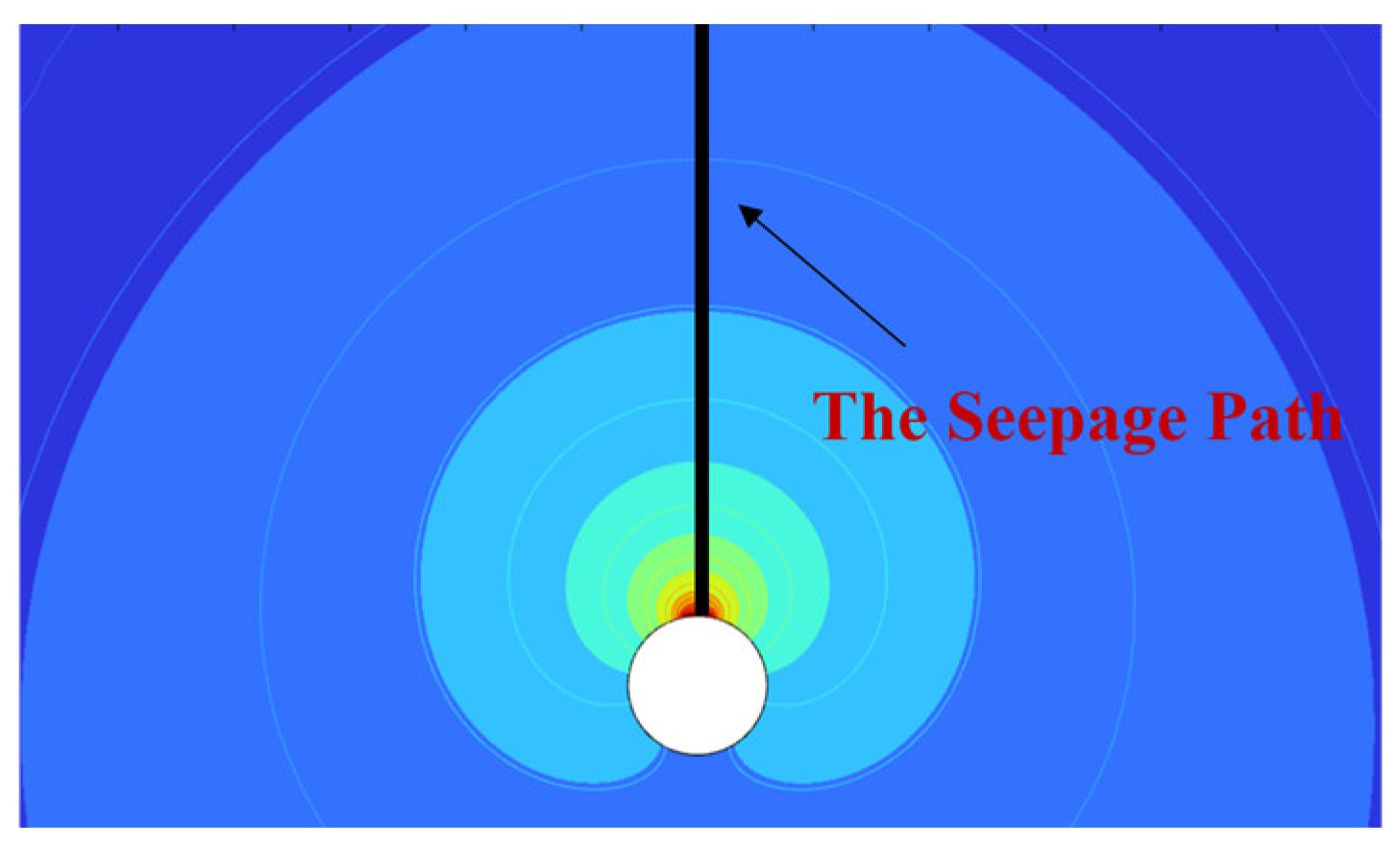

- During pipeline leakage, the moisture content in the soil around the leak point responds progressively from near to far. At the early stage, a preferential seepage path forms vertically above the leak point, and saturation changes first at equidistant measurement points along this path. With continued seepage, the preferential path gradually weakens, and the overall seepage pattern evolves into radial diffusion centered on the leak point under the combined effects of water pressure and gravity.

- (2)

- The diffusion of the saturated zone is strongly influenced by pipeline pressure. Higher pressures promote both larger and faster expansion of the saturated area; however, the relationship is nonlinear. The incremental effect of pressure on diffusion diminishes as the pipeline pressure continues to increase.

- (3)

- The calculated distribution of hydraulic gradients shows that higher pipeline pressures and longer leakage durations enlarge the potential area of seepage damage. Nevertheless, the ultimate extent of the critical zone is not directly dependent on pipeline pressure or leakage duration. Within approximately 5–10 h after leakage initiation, the critical zone becomes fully developed, typically extending to a radius of about 2.3 m around the pipeline.

- (4)

- The study further proposes that potential seepage damage may occur once effective saturation reaches approximately 85%, which corresponds to the air-entry value of loess. At this stage, the soil transitions from the doubly drained phase to the air-entrapment phase. Although a certain amount of air remains in the pores, stable seepage channels have already formed and soil particles are subjected to drag forces from moving water. Using the air-entry value as a threshold provides a conservative and safer criterion for identifying seepage-prone conditions.

- (5)

- The adoption of a two-dimensional model allowed efficient simulation of unsaturated seepage and successfully reproduced the main diffusion patterns observed in laboratory tests. Nevertheless, the isotropic assumption and 2D boundary conditions introduce simplifications, and the results are not directly applicable to layered or heterogeneous soils. In longer-term leakage scenarios, the dominant mechanism may also shift from hydraulic-gradient-induced instability to strength degradation under prolonged high saturation. These aspects highlight the need for future research using fully three-dimensional, coupled hydro-mechanical models.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Q.; Wang, M. Numerical Investigation of Water Migration in a Closed Unsaturated Expansive Clay System. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Diao, Y.; Guo, C.; Li, P.; Du, X.; Pan, Y. Two-Stage Column–Hemispherical Penetration Diffusion Model Considering Porosity Tortuosity and Time-Dependent Viscosity Behavior. Acta Geotech. 2022, 18, 2661–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhu, B.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y. A Model on Assessing Effects of Gas Diffusion in Multifield Coupled Process for Unsaturated Soils. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Madenci, E.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Q. A Coupled Hydro-Mechanical Peridynamic Model for Unsaturated Seepage and Crack Propagation in Unsaturated Expansive Soils Due to Moisture Change. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 6297–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Duan, R.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. A Method for Leak Detection in Buried Pipelines Based on Soil Heat and Moisture. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 135, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ren, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, C. Spherical Permeation Grouting Model of a Power-Law Fluid Considering the Soil Unloading Effect. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 04023266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, K.; Ye, F.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Su, E.; Han, X. Backfill Grouting Diffusion Law of Shield Tunnel Considering Porous Media with Nonuniform Porosity. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 127, 104607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y. Modelling of Permeation Grouting Considering Grout Self-Gravity Effect: Theoretical and Experimental Study. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 7968240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Fan, Z.; Li, Q. A Discrete Element Method for Calculating Saturated and Unsaturated Seepage in Landslide Soils and a Case Study. Landslides 2025, 22, 2379–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, W.; Shi, L. Steady Seepage Analysis in Soil-Rock-Mixture Slope Using the Numerical Manifold Method. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2021, 131, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Qin, C. Stability Analysis of Unsaturated Soil Slopes under Reservoir Drawdown and Rainfall Conditions: Steady and Transient State Analysis. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 142, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, F.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Che, D.; Huang, Z. Numerical Investigation on Pinhole Leakage and Diffusion Characteristics of Medium-Pressure Buried Hydrogen Pipeline. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ren, N.; Shi, W. A Coupled CFD-DEM Simulation of Upward Seepage Flow in Coarse Sands. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2019, 37, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Kuwano, R. Influence of Location of Subsurface Structures on Development of Underground Cavities Induced by Internal Erosion. Soils Found. 2015, 55, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research of Seepage Influence on the Lateral Water-Earth Pressure in Underground Structures|Scientific.Net. Available online: https://www.scientific.net/AMR.838-841.1663 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Xu, Y.-S.; Shen, S.-L.; Chai, J.-C.; Hong, Z.-S. Analysis of Cutoff Effect on Groundwater Seepage of Underground Structures in Aquifers of Shanghai. Int. Conf. Comput. Exp. Eng. Sci. 2011, 20, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Liu, F.; Chen, R.; Wang, S.; Pu, C.; Zhao, X. Effects of Internal Pressure on Urban Water Supply Pipeline Leakage-Induced Soil Subsidence Mechanisms. Geofluids 2024, 2024, 9577375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Tan, W.; Yan, F.; Qi, X.; Li, Q.; Hong, Z. Model Test Analysis of Subsurface Cavity and Ground Collapse Due to Broken Pipe Leakage. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 13017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Bao, T.; Liu, C. Model Tests and Numerical Modeling of the Failure Behavior of Composite Strata Caused by Tunneling under Pipeline Leakage Conditions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 149, 107287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Gui, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, X. Stability Analysis of the Slope around Flood Discharge Tunnel under Inner Water Exosmosis at Yangqu Hydropower Station. Comput. Geotech. 2013, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Feng, D.; Zhang, S.; Lin, R. Support Pressure Assessment of Tunnels in the Vicinity of Leaking Pipeline Using Unified Upper Bound Limit Analysis. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 144, 104662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kang, R.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X. Numerical Simulation and Safety Evaluation of Multi-Source Leakage of Buried Product Oil Pipeline. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2022, 44, 6737–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezaatpour, J.; Fatehifar, E.; Rasoulzadeh, A. CFD Investigation of Natural Gas Leakage and Propagation from Buried Pipeline for Anisotropic and Partially Saturated Multilayer Soil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zuo, Z.; Shi, C.; Hu, X. Feasibility Study for Spatial Distribution of Diesel Oil in Contaminated Soils by Laser Induced Fluorescence. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, H.; Chen, D.; Kou, Y.; Yang, R. Leakage and Diffusion Behavior of a Buried Pipeline of Hydrogen-Blended Natural Gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 11592–11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Lyu, X.; Liao, K.; Li, Y.; Sun, L. A Method for Fast Simulating the Liquid Seepage-Diffusion Process Coupled with Internal Flow after Leaking from Buried Pipelines. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liao, Y.; Liang, J.; Cui, Z.; Li, Y. Quantifying Methane Release and Dispersion Estimations for Buried Natural Gas Pipeline Leakages. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 146, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Xu, P.; Lu, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K. Research on Pipeline Leakage Calculation and Correction Method Based on Numerical Calculation Method. Energies 2023, 16, 7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Q.; Chen, M.; He, Q.; Christopher, D.M.; Cheng, X.; Chowdhury, B.R.; Hecht, E.S. Modeling of Underexpanded Hydrogen Jets through Square and Rectangular Slot Nozzles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 6353–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Ni, T.; Zaccariotto, M.; Galvanetto, U. A Hybrid Fractional-Derivative and Peridynamic Model for Water Transport in Unsaturated Porous Media. Fractals 2023, 31, 2350080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-W.; Xu, Y.-S. Investigation on the Phenomena and Influence Factors of Urban Ground Collapse in China. Nat. Hazards 2022, 113, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L.A. Capillary Conduction of Liquids Through Porous Mediums. Physics 1931, 1, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Cheng, W.-C.; Hu, W.; Rahman, M.M. Changes in Air and Liquid Permeability Properties of Loess Due to the Effect of Lead Contamination. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1165685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Cheng, W.-C.; Hu, W.; Li, D.; Shao, L. Effect of Temperature on Gas Breakthrough and Permeability of Compacted Loess in Landfill Cover. Geomech. Energy Environ. 2023, 36, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Qian, H.; Xu, P.; Wang, H. Experimental Study of Permeability of Malan and Lishi Loess in Yan’an New Area. J. Eng. Geol. 2017, 25, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. On basic theories of unsaturated soils and special soils. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 36, 201–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, R.; Liu, L.; Zhou, C.; Bate, B. A Non-Darcy Flow CFD–DEM Method for Simulating Ground Collapse Induced by Leakage through Underground Pipeline Defect. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 162, 105695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Genuchten, M.T. A Closed-form Equation for Predicting the Hydraulic Conductivity of Unsaturated Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, D.G.; Xing, A. Equations for the Soil-Water Characteristic Curve. Can. Geotech. J. 2011, 31, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Soil Seepage Stability and Seepage Control; Water Resources and Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 1992. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Xu, H.; Cao, Y.; Hu, X. A Theoretical Model to Predict the Critical Hydraulic Gradient for Soil Particle Movement under Two-Dimensional Seepage Flow. Water 2017, 9, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Liu, J.; Han, B.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Critical Hydraulic Gradient of Internal Erosion at the Soil–Structure Interface. Processes 2018, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.-H.; Wang, J.-Y. Experiment and Statistical Assessment on Piping Failures in Soils with Different Gradations. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2017, 35, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, L.; Niu, Z. Critical Hydraulic Gradient and Fine Particle Migration of Sand under Upward Seepage Flow. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annapareddy, V.S.R.; Sufian, A.; Bore, T.; Scheuermann, A. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Particle Migration in Gap-Graded Granular Soils: Insights from Experimental Observations. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2023, 149, 04022135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| VG model parameter | α | 0.45 | 1/m |

| VG model parameter | m | 3.3 | 1 |

| VG model parameter | l | 0.5 | 1 |

| Porosity | n | 0.43 | 1 |

| Permeability | k | 9.7 × 10−8 | m/s |

| Intrinsic permeability | κ | 9.7 × 10−15 | m2 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity of soil particles | ds | 2.71 |

| Density | ρ | 1.53 g/cm3 |

| Moisture content | w | 3%~7% |

| Plastic limit | wP | 15.78% |

| Liquid limit | wL | 26.11% |

| Measurement Point | Maximum Relative Error | Average Relative Error |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42% | 13.5% |

| 2 | 37% | 7% |

| Test Scenario | Initial Saturation | Pressure (kPa) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12% | 150 |

| 2 | 12% | 200 |

| 3 | 12% | 250 |

| 4 | 12% | 300 |

| Time (h) | Parameters (a, b, c, l) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (−3.91, 2.58, 0.17, 0.86) | 0.9980 |

| 6 | (−2.79, 3.24, 0.22, 1.57) | 0.9779 |

| 12 | (−2.44, 3.52, 0.24, 2.00) | 0.9964 |

| 24 | (−1.94, 3.71, 0.26, 2.70) | 0.9954 |

| 48 | (−1.34, 3.73, 0.26, 2.70) | 0.9952 |

| Time (h) | Parameters (a3, a2, a1, a0, L) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (−16.87, 42.42, −35.98, 13.25, 0.86) | 0.9828 |

| 6 | (−12.34, 36.39, −36.08, 12.72, 1.57) | 0.9779 |

| 12 | (−6.45, 23.79, −29.31, 12.32, 2.00) | 0.9700 |

| 24 | (−2.93, 14.19, −22.32, 11.81, 2.70) | 0.9572 |

| 48 | (−2.82, 13.63, −21.44, 11.92, 2.70) | 0.9486 |

| Time (h) | Parameters (A, B, L) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (14.28,5.466,0.86) | 0.9828 |

| 6 | (13.45,3.635,1.57) | 0.9779 |

| 12 | (13.24,3.007,2.00) | 0.9700 |

| 24 | (12.93,2.649,2.70) | 0.9572 |

| 48 | (12.68,2.301,2.70) | 0.9486 |

| Time (h) | Expression of i(x,t) | Domain of x (m) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | [0, 0.86] | |

| 6 | [0, 1.57] | |

| 12 | [0, 2.00] | |

| 24 | [0, 2.70] | |

| 48 | [0, 2.70] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Liu, F.; Wang, K.; Cui, J.; Zhao, X. Numerical Analysis of Seepage Damage and Saturation Variation in Surrounding Soil Induced by Municipal Pipeline Leakage. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11088. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011088

Wang S, Liu F, Wang K, Cui J, Zhao X. Numerical Analysis of Seepage Damage and Saturation Variation in Surrounding Soil Induced by Municipal Pipeline Leakage. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11088. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011088

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shuangshuang, Fengyin Liu, Ke Wang, Jingyu Cui, and Xuguang Zhao. 2025. "Numerical Analysis of Seepage Damage and Saturation Variation in Surrounding Soil Induced by Municipal Pipeline Leakage" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11088. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011088

APA StyleWang, S., Liu, F., Wang, K., Cui, J., & Zhao, X. (2025). Numerical Analysis of Seepage Damage and Saturation Variation in Surrounding Soil Induced by Municipal Pipeline Leakage. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11088. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011088