Prediction Method of Available Nitrogen in Red Soil Based on BWO-CNN-LSTM

Abstract

1. Introduction

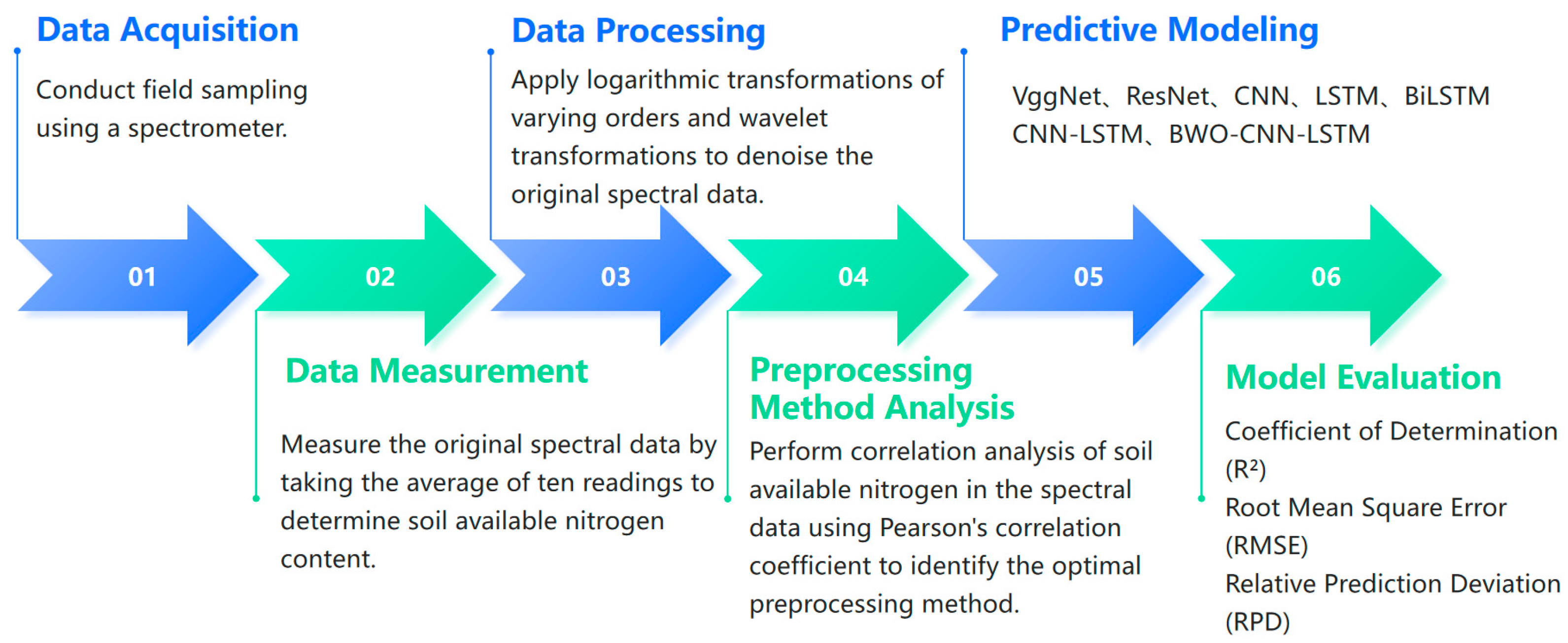

2. Materials and Methods

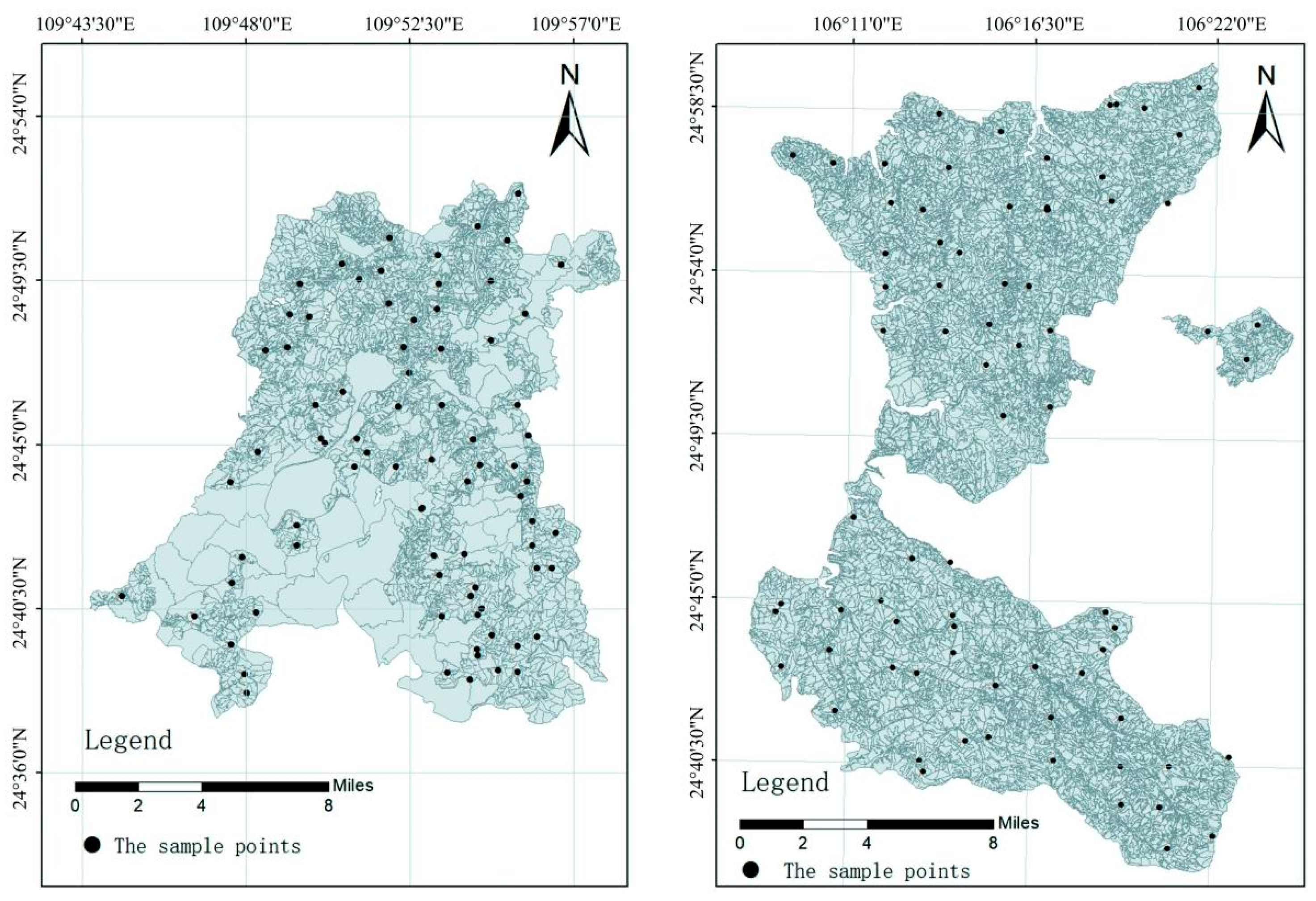

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Soil Sample Collection

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Spectral Processing Methods

2.4.1. SPXY Sample Partitioning Algorithm

2.4.2. Logarithmic Differential Transformation (LOG)

2.4.3. Wavelet Transformation (WT) for Noise Reduction

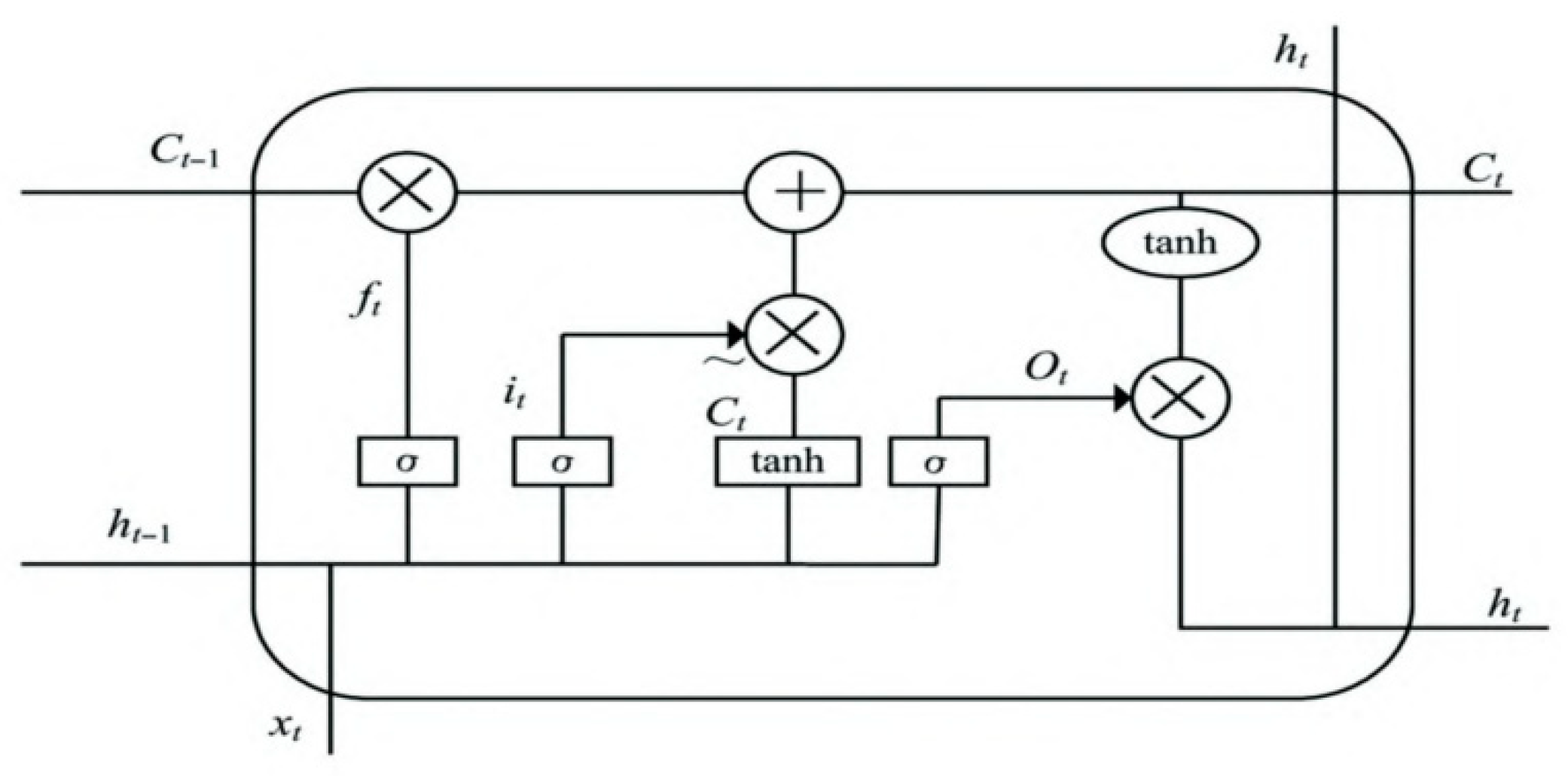

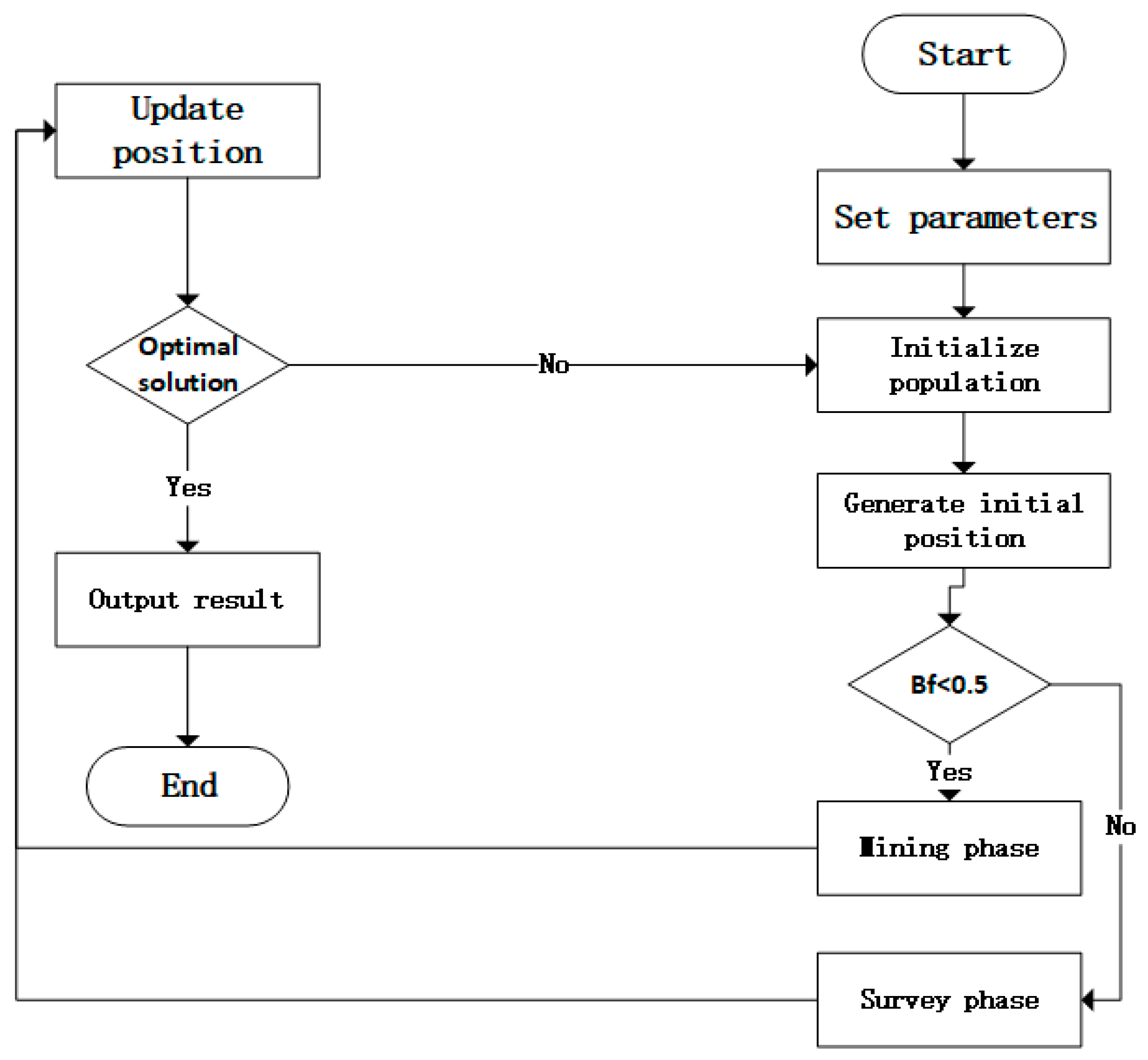

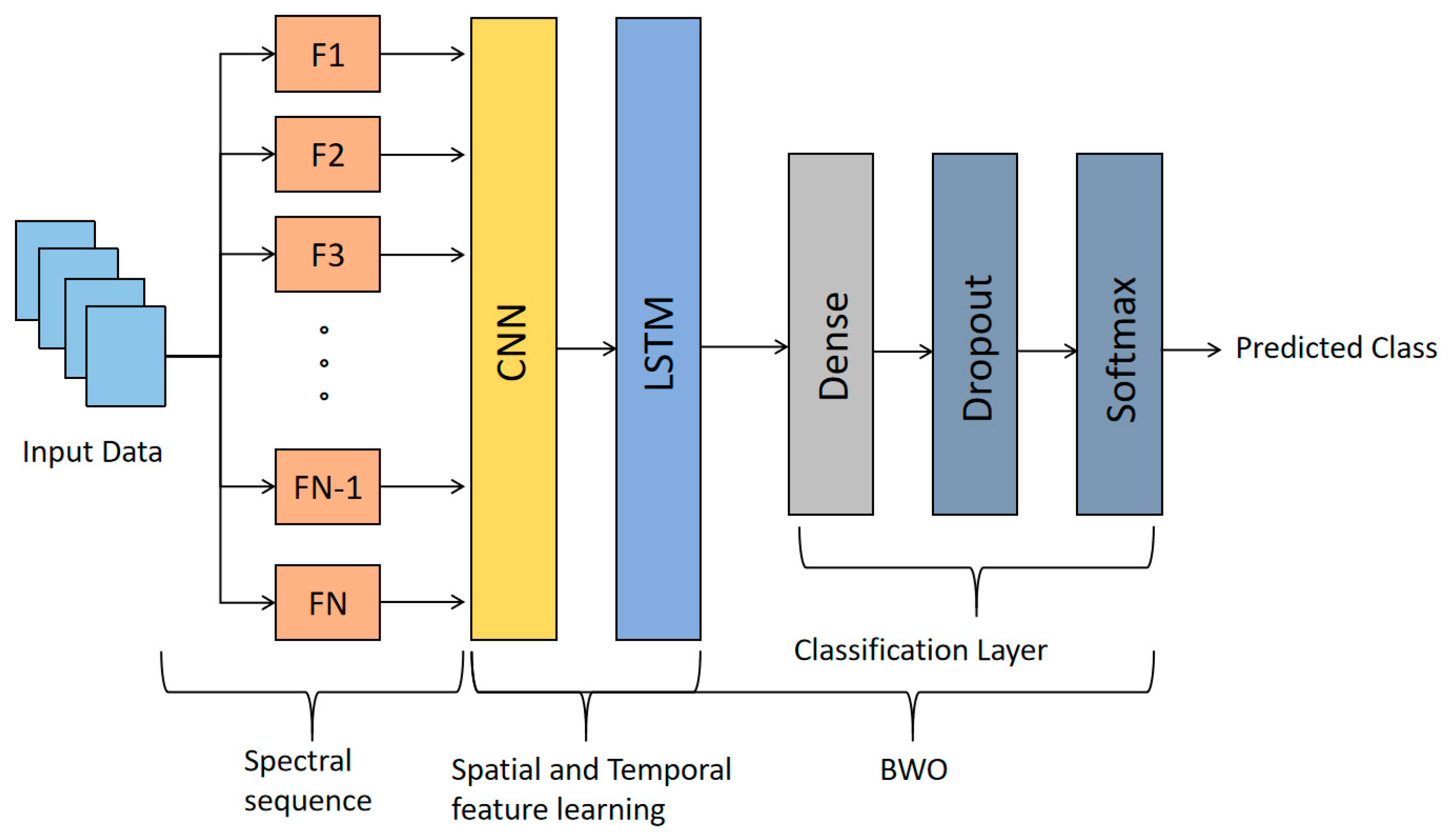

2.5. The Structure of the BWO-CNN-LSTM Network

2.6. Other Deep Learning Methods

2.6.1. VGGNet

2.6.2. ResNet

2.7. Evaluation Metrics

2.8. Experimental Environment

3. Results

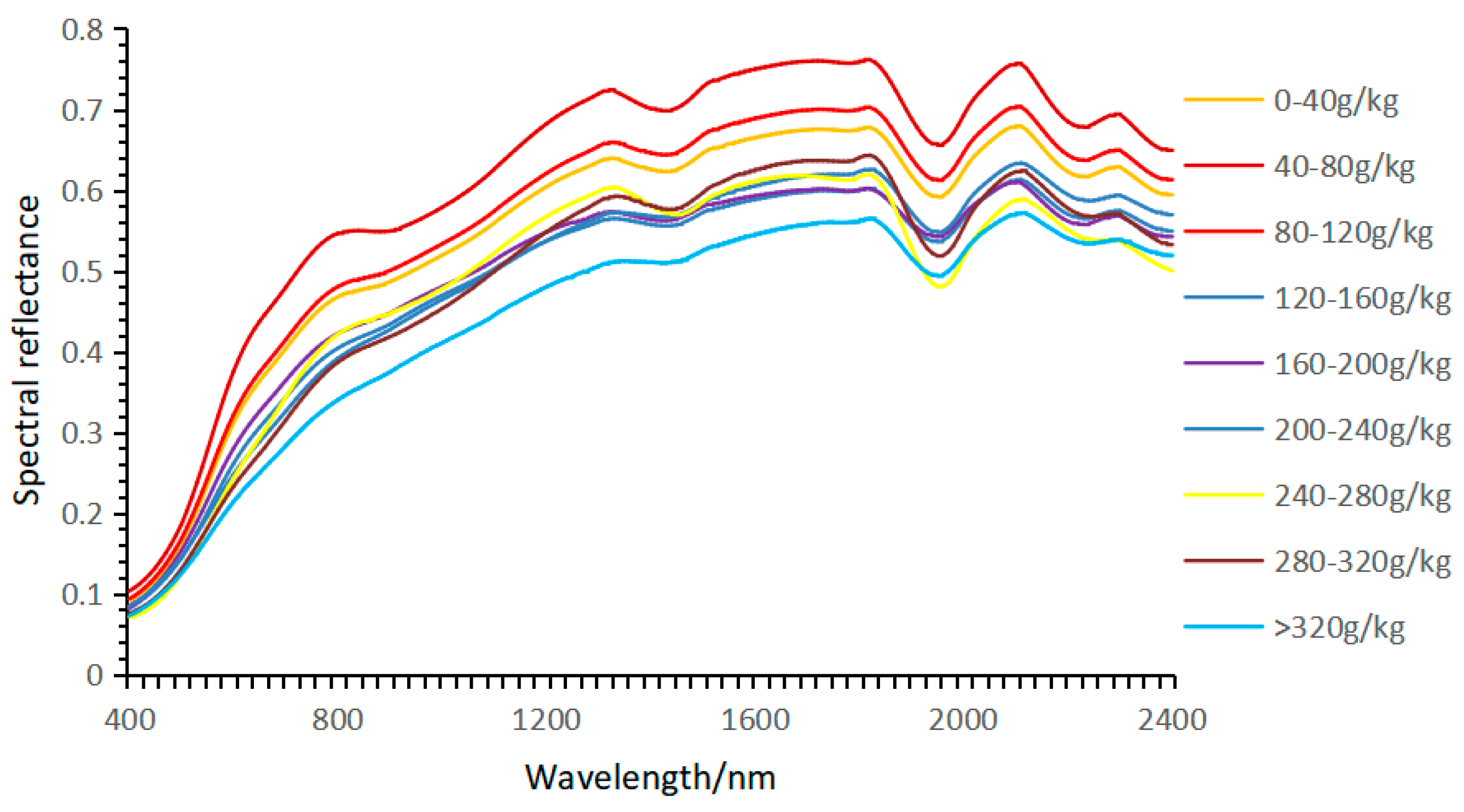

3.1. Statistical Characteristics of Soil Available Nitrogen Content

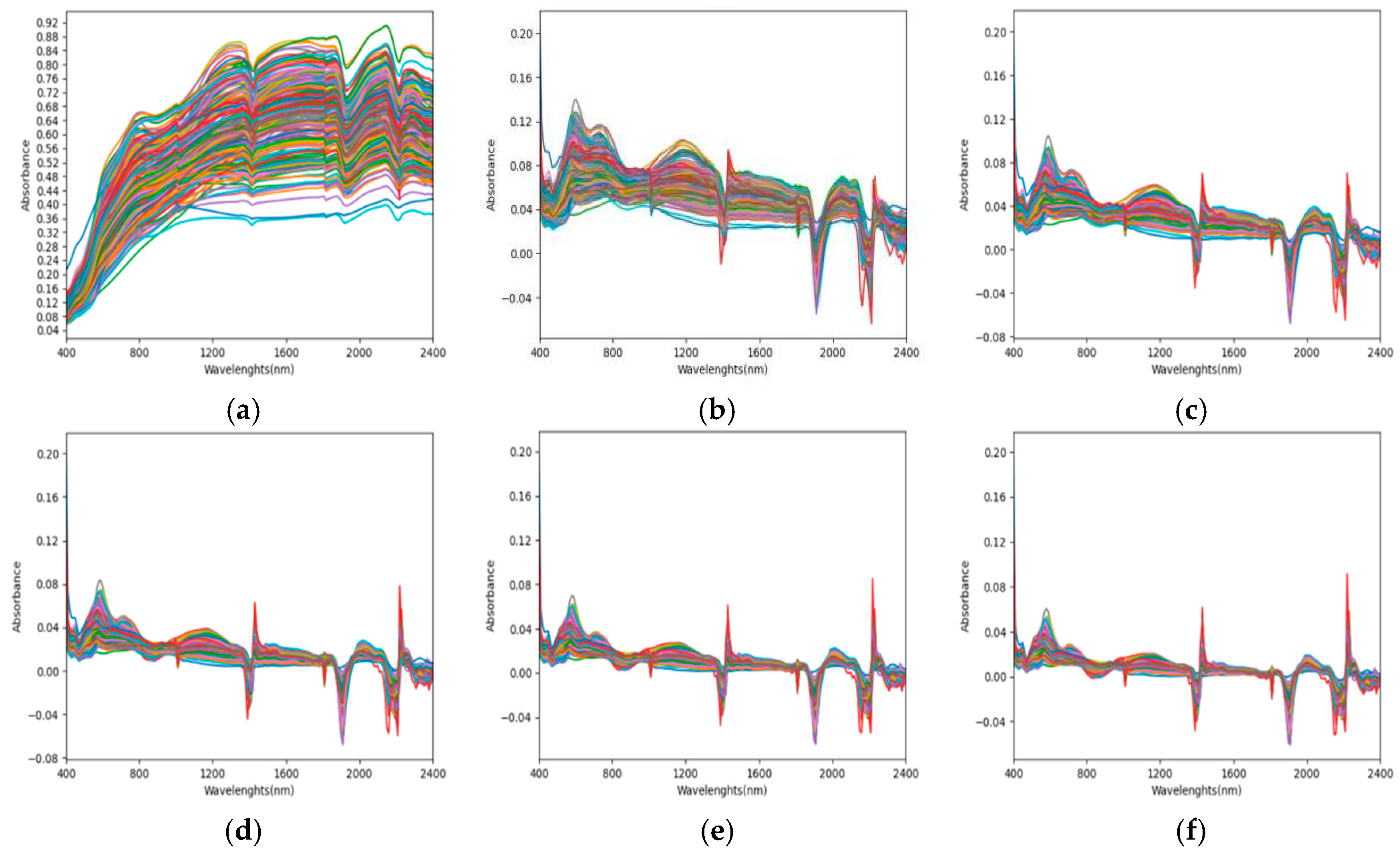

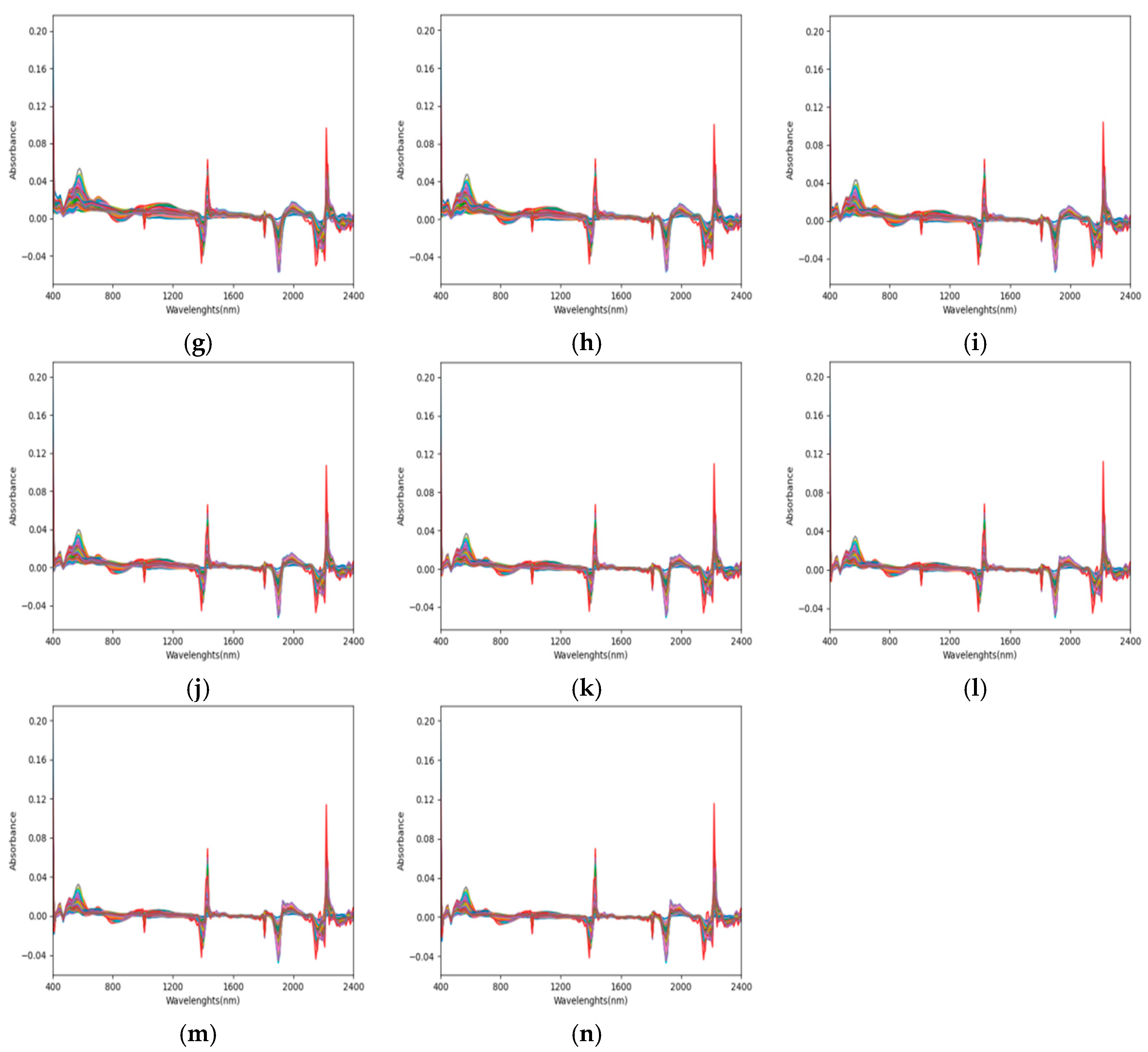

3.2. Laboratory Spectral Preprocessing

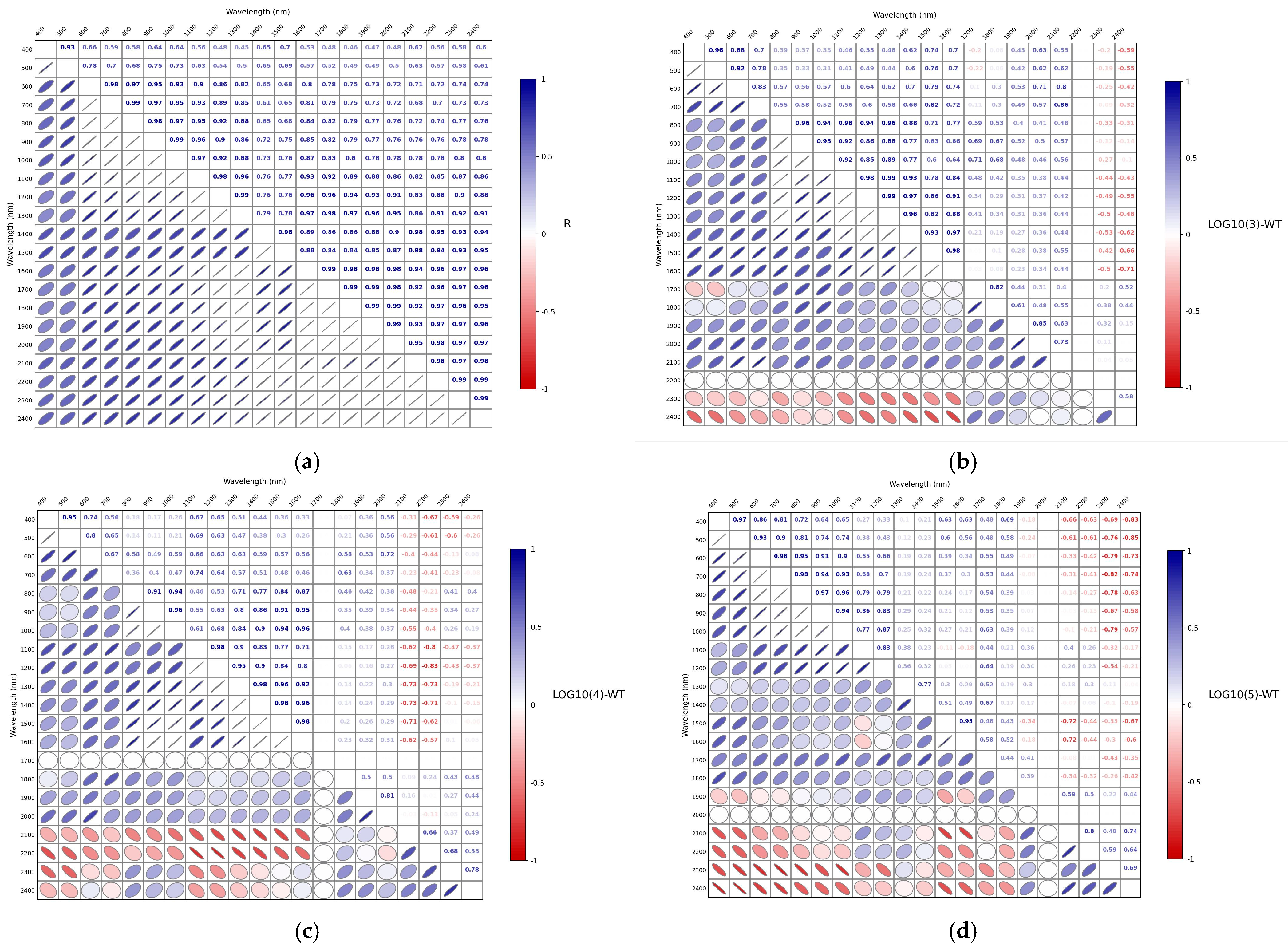

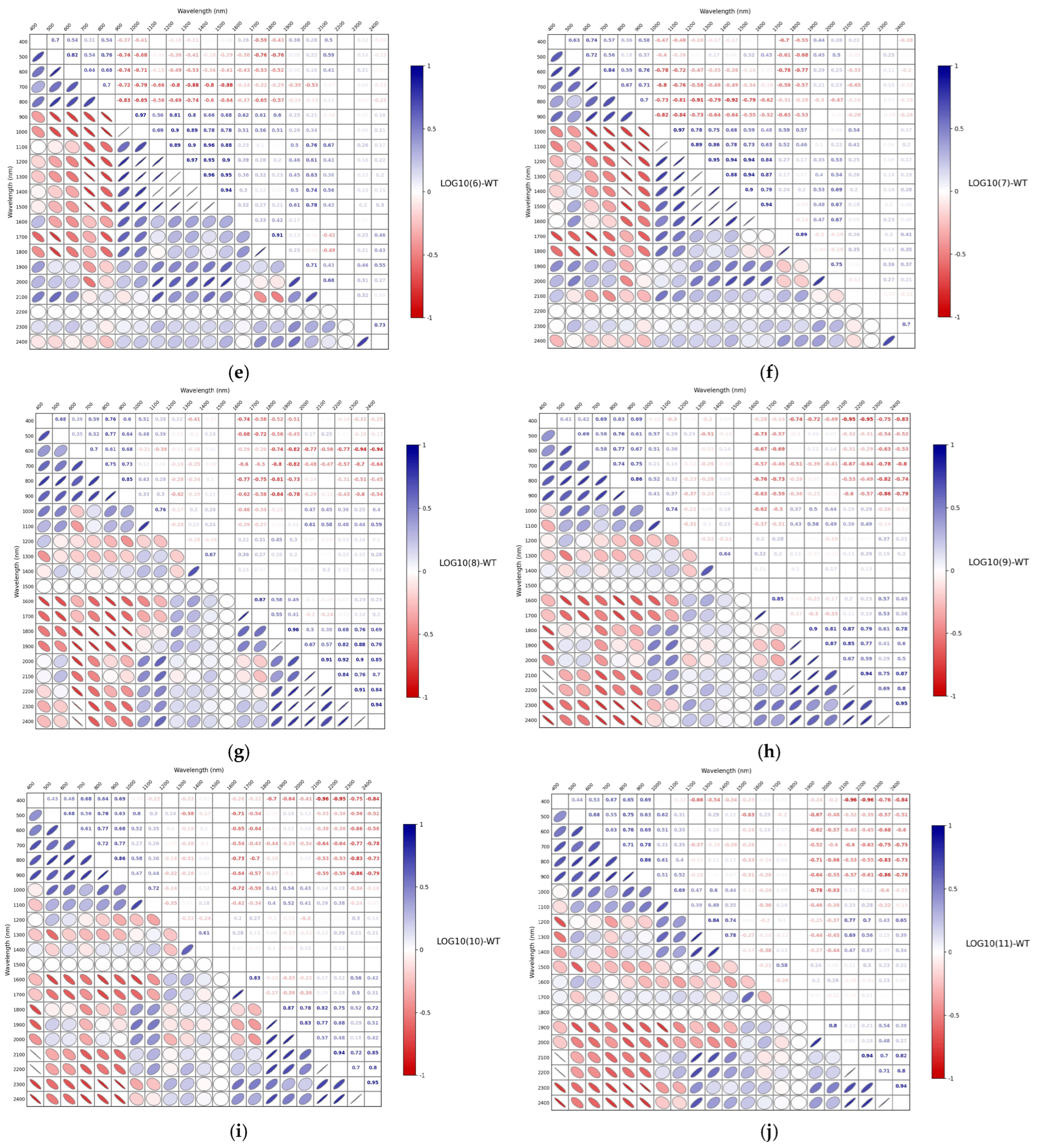

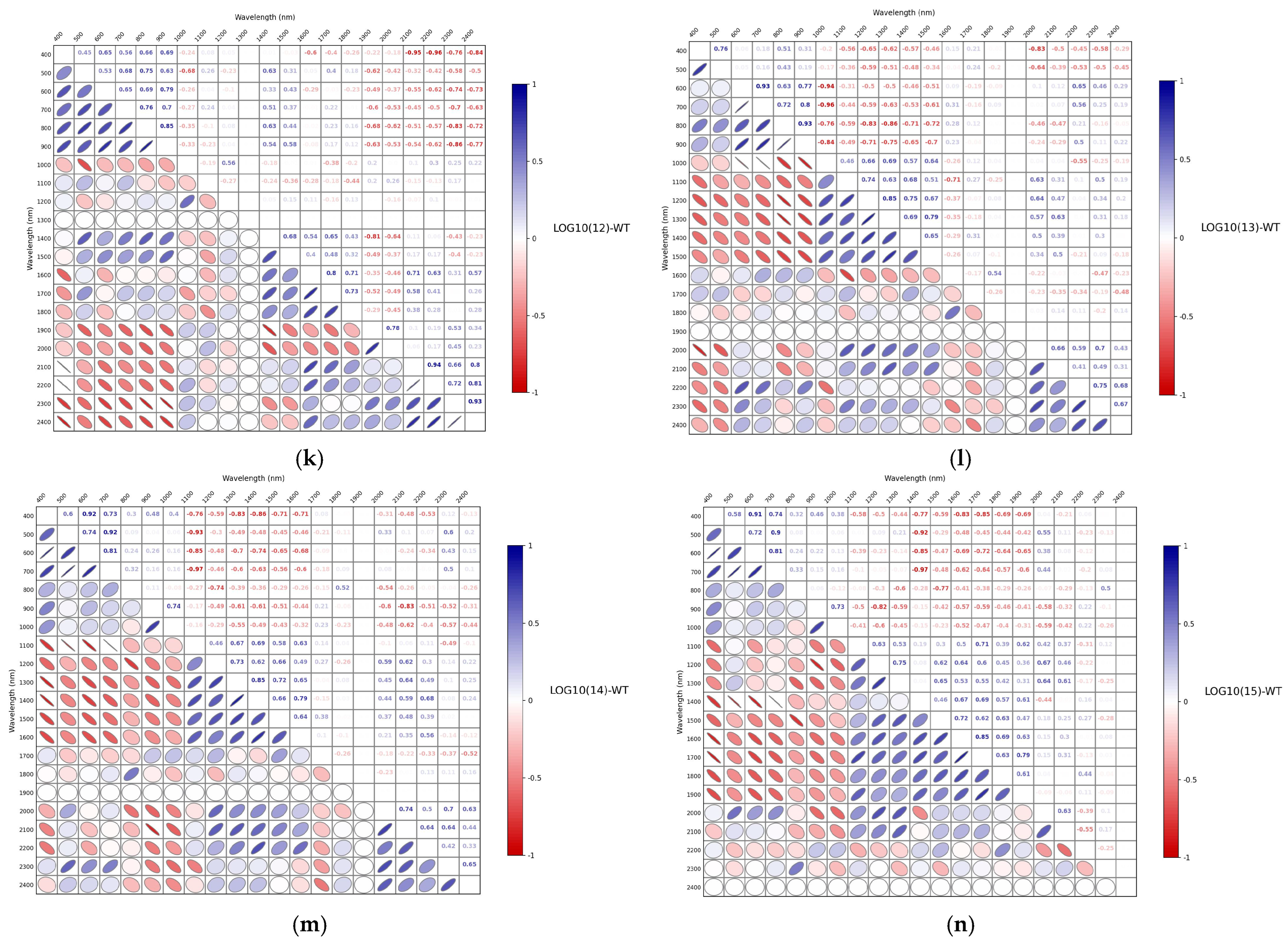

3.3. Correlation Analysis of Spectra After Different Mathematical Transformations

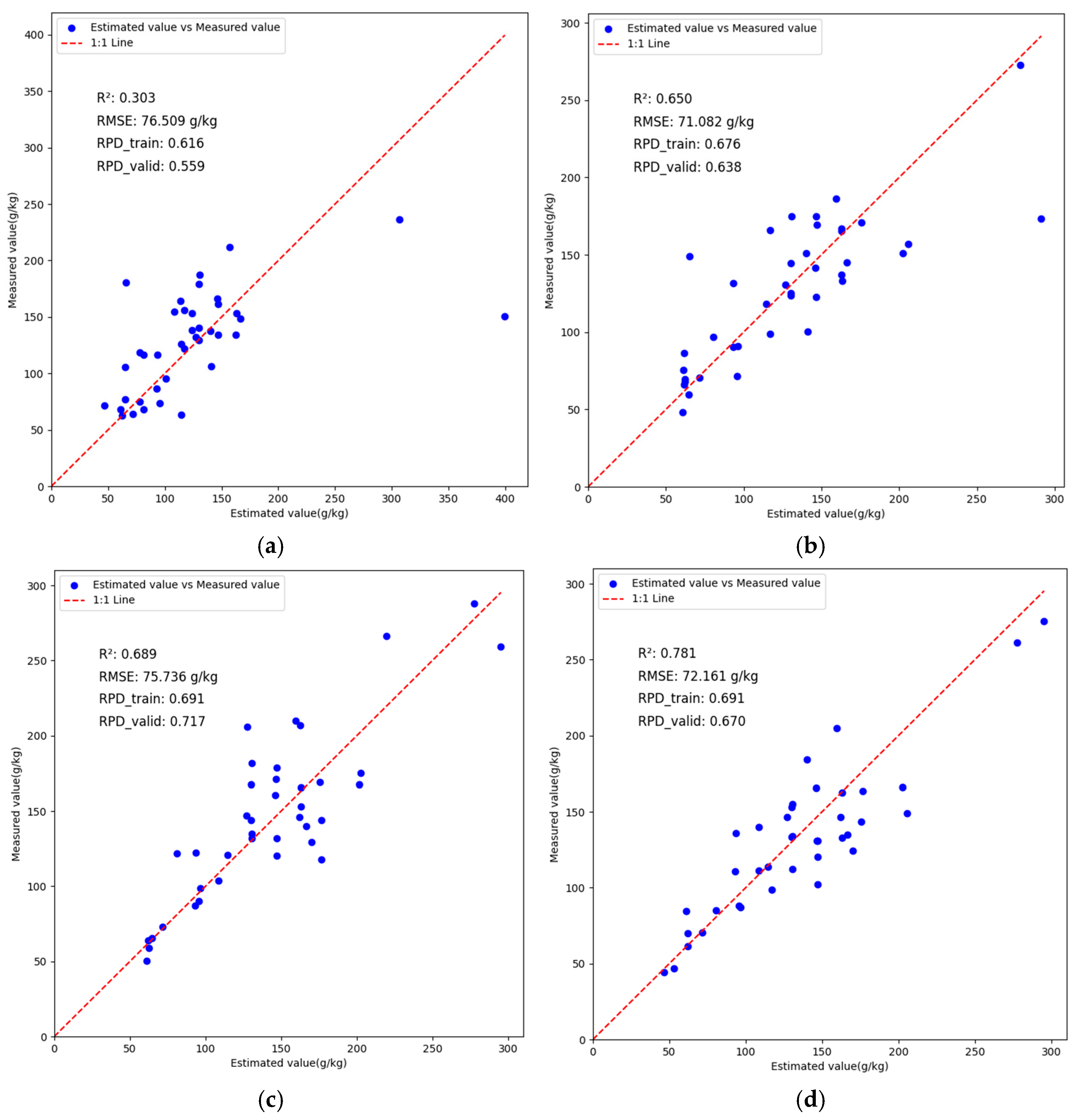

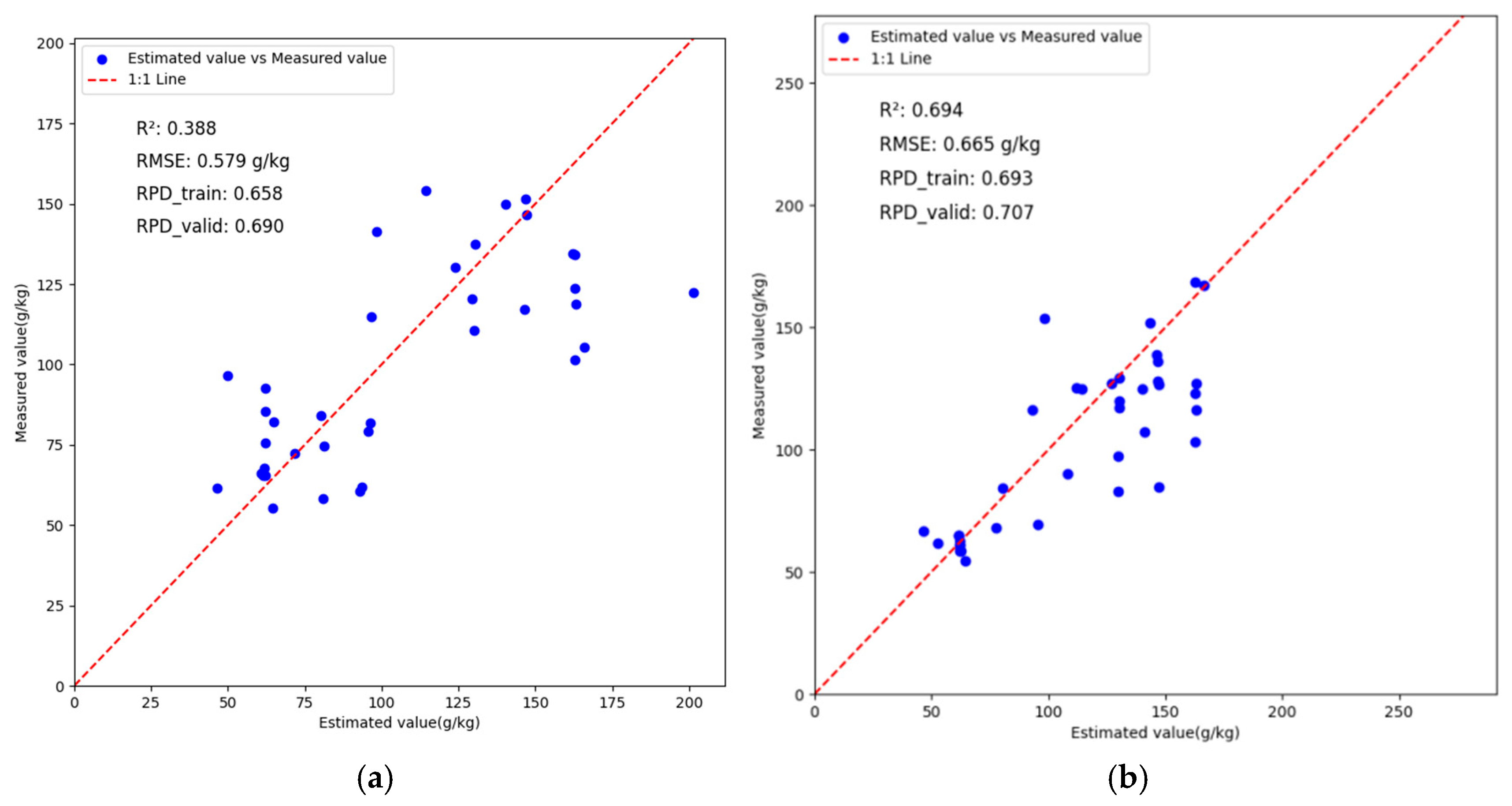

3.4. VggNet Inversion Analysis Based on Different Preprocessing Methods

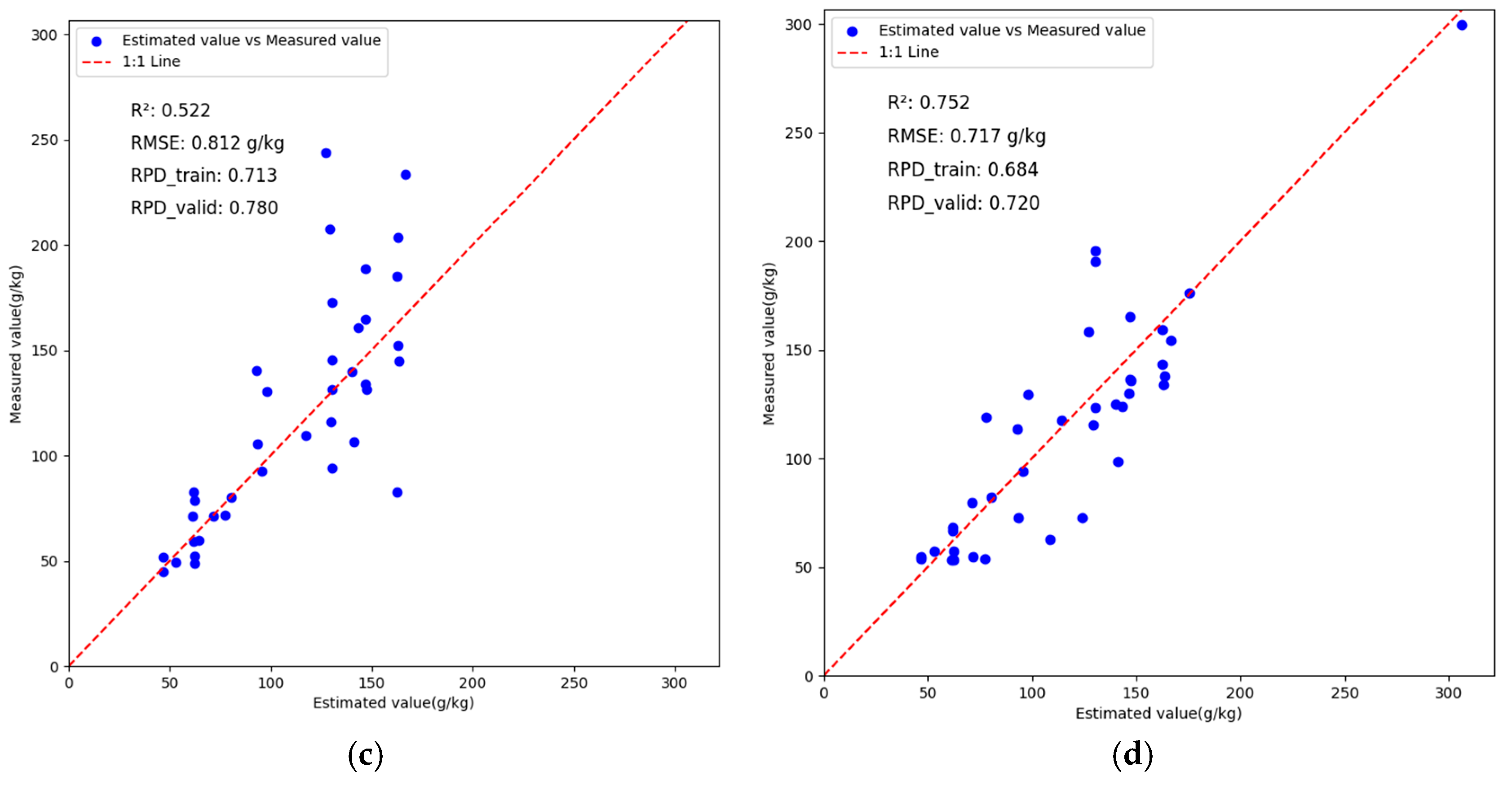

3.5. ResNet Inversion Analysis Based on Different Preprocessing Methods

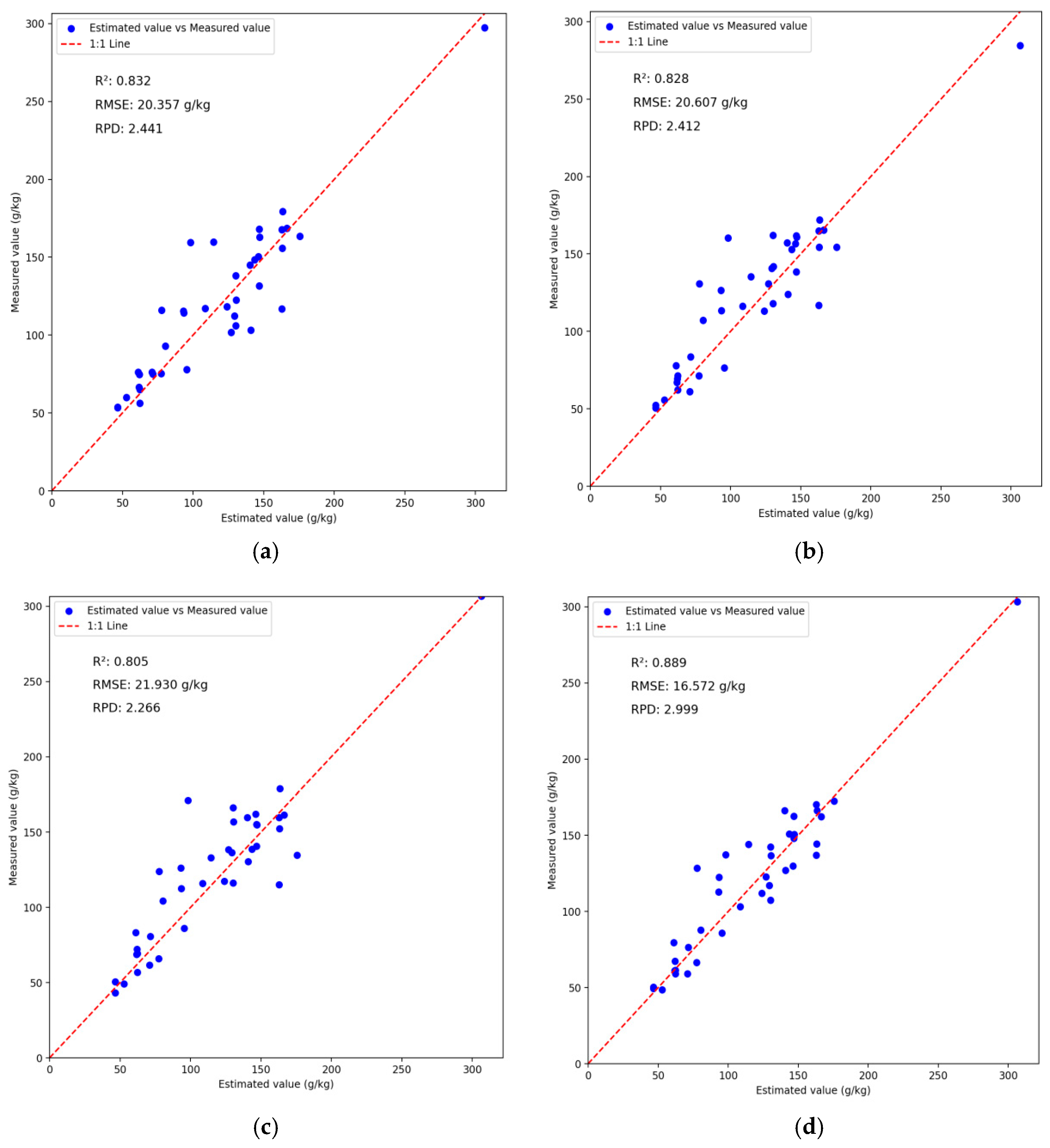

3.6. Analysis of BWO-CNN-LSTM Network Model Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.-C.; Yang, W.; Cui, Y.-L.; Zhou, P.; Wang, D.; Li, M.-Z. Prediction of soil total nitrogen content based on CatBoost algorithm and graph feature fusion. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 316–322. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jian, J. Hyperspectral estimation modeling of soil As content in the eastern part of Tianfu New District, Chengdu based on SPA-BPNN. J. Guilin Univ. Technol. 2024, 44, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Li, X.-C. Indirect estimation of organic matter in cultivated soil based on surface soil spectrum. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2020, 47, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Nitrogen-total. Methods Soil Anal. 1996, 3, 1085–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Nocita, M.; Stevens, A.; Noon, C.; van Wesemael, B. Prediction of soil organic carbon for different levels of soil moisture using Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Geoderma 2013, 199, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, A.; Borůvka, L.; Saberioon, M.; Vašát, R. Visible, near-infrared, and mid-infrared spectroscopy applications for soil assessment with emphasis on soil organic matter content and quality: State-of-the-art and key issues. Appl. Spectrosc. 2013, 67, 1349–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Guo, X. Hyperspectral estimation of organic matter in red soil based on different convolutional neural network models. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.-J.; Zhang, B. Study on hyperspectral model of organic matter content in black soil. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2007, 1, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.-M.; Li, X.-Q. Inversion of total nitrogen content in rubber plantation soil in Yunnan based on hyperspectral analysis. Trop. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 46, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.-Y.; Bai, Z.-J. Comparative study on soil total nitrogen content estimation models based on hyperspectral data. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2022, 1, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-W.; Wei, Y.-X. Study on hyperspectral model of total nitrogen and total phosphorus content in wetland soil. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2016, 36, 5116–5125. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Choi, H.-J.; Park, S.; Kim, Y. Predicting the Freezing Characteristics of Organic Soils Using Laboratory Experiments and Machine Learning Models. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Li, T.; Zhu, X.; Dou, L.; Liu, Z.; Qian, K.; Ye, G.; Lin, K.; Li, B.; Ma, X.; et al. Predicting the Zinc Content in Rice from Farmland Using Machine Learning Models: Insights from Universal Geochemical Parameters. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, T.; Neményi, M.; Nyéki, A. Soil Moisture Content Prediction Using Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) Model: Soil-Specific Modeling with Five Depths. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Kim, J.; Choi, H.; Lee, J.; Han, J. Case Study on Analysis of Soil Compression Index Prediction Performance Using Linear and Regularized Linear Machine Learning Models (In Korea). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, A.-L.; Wang, X.-S. Quantitative modeling method of corn components based on near-infrared spectral fusion and deep learning. Food Ferment. Ind. 2020, 46, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.-Y.; Wu, T.-J. Remote sensing fine mapping of agricultural planting structure based on spatiotemporal coordination. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2024, 28, 2014–2029. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.-Y.; Zhu, Z.-Y. Dataset representativeness measurement and block sampling strategy for the pan-Kennard-Stone algorithm. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2022, 43, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-L.; Wang, H. Estimation of soil organic matter content in mountainous cultivated land based on hyperspectral analysis. Jiangsu J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 40, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Huang, Y. Deep convolutional neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. J. Sens. 2015, 2015, 258619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L.; Johnstone, I.M. Ideal spatial adaptation by wavelet shrinkage. Biometrika 1994, 81, 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, G.; Meng, Z. Beluga whale optimization: A novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 251, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, S.; Shen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Jin, P. Facial expression recognition based on VGGNet convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2018 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Xi’an, China, 30 November–2 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 4146–4151. [Google Scholar]

- Targ, S.; Almeida, D. Resnet in resnet: Generalizing residual architectures. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.08029 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer (Type) | Output Shape | Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| Conv1d | (32, 128) | 128 |

| Max_Pooling1d | (32, 64) | 0 |

| Conv1d_1 | (64, 64) | 6028 |

| Max_Pooling1d_1 | (64, 32) | 0 |

| Conv1d_2 | (128, 32) | 24,704 |

| Max_Pooling1d_2 | (128, 16) | 0 |

| Lstm | 64 | 78,840 |

| Lstm_1 | 64 | 88,440 |

| Flatten | 1024 | 0 |

| Dense | 200 | 322,200 |

| Dropout | 100 | 0 |

| Activation | 1 | 0 |

| Dense_1 | 100 | 20,100 |

| Dropout_1 | 50 | 0 |

| Dense_2 | 1 | 101 |

| Sample Type | Sample Size | Minimum Value | Maximum Value | Average Value | Standard Deviation | Kurtosis | Skewness | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All sample | 196 | 30.9 | 399.7 | 118.11 | 60.37 | 4.19 | 1.60 | 51.11 |

| Training sample | 157 | 30.9 | 396.1 | 117.80 | 57.70 | 3.82 | 1.52 | 48.98 |

| Validation sample | 39 | 46.4 | 399.7 | 119.30 | 69.82 | 4.23 | 1.71 | 58.52 |

| Preprocessing Method | Training Set | Validation Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | RPD | R2 | RMSE | RPD | |

| R | 0.6906 | 33.1286 | 1.4081 | 0.3031 | 52.8481 | 0.8087 |

| LOG10(10) | 0.9159 | 17.8033 | 3.17 | 0.6497 | 32.3812 | 1.4009 |

| LOG10(3)-WT | 0.8881 | 19.7638 | 2.7036 | 0.4380 | 47.9229 | 0.9513 |

| LOG10(4)-WT | 0.9062 | 19.2557 | 2.9212 | 0.7082 | 25.3566 | 1.8336 |

| LOG10(5)-WT | 0.9148 | 18.0504 | 3.1393 | 0.7565 | 36.3067 | 1.9394 |

| LOG10(6)-WT | 0.9545 | 13.2955 | 4.4836 | 0.6731 | 28.7739 | 1.7007 |

| LOG10(7)-WT | 0.9135 | 16.6717 | 3.0913 | 0.4523 | 51.5379 | 0.8439 |

| LOG10(8)-WT | 0.9468 | 14.6119 | 4.0903 | 0.6683 | 26.0886 | 1.7466 |

| LOG10(9)-WT | 0.9392 | 15.1147 | 3.8806 | 0.7811 | 24.9976 | 1.9338 |

| LOG10(10)-WT | 0.9333 | 15.6905 | 3.7059 | 0.6894 | 29.3535 | 1.8491 |

| LOG10(11)-WT | 0.9452 | 14.2308 | 3.9513 | 0.7391 | 28.8747 | 1.7887 |

| LOG10(12)-WT | 0.9472 | 13.9436 | 4.0996 | 0.7616 | 27.8631 | 1.7528 |

| LOG10(13)-WT | 0.9219 | 16.9916 | 3.3569 | 0.6559 | 33.0986 | 1.4460 |

| LOG10(14)-WT | 0.9365 | 15.1711 | 3.6011 | 0.7084 | 30.8213 | 1.5037 |

| LOG10(15)-WT | 0.9375 | 15.0657 | 3.6281 | 0.7474 | 28.6878 | 1.7563 |

| Preprocessing Method | Training Set | Validation Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | RPD | R2 | RMSE | RPD | |

| R | 0.8564 | 0.2421 | 2.3057 | 0.3882 | 0.3273 | 1.2207 |

| LOG10(10) | 0.9925 | 0.0549 | 11.0878 | 0.6936 | 0.2559 | 1.8371 |

| LOG10(3)-WT | 0.9754 | 0.0983 | 6.0457 | 0.5650 | 0.3275 | 1.6445 |

| LOG10(4)-WT | 0.9874 | 0.0705 | 8.5057 | 0.5898 | 0.3135 | 1.3578 |

| LOG10(5)-WT | 0.9828 | 0.0821 | 7.6616 | 0.5857 | 0.3191 | 1.7773 |

| LOG10(6)-WT | 0.9773 | 0.0954 | 6.8182 | 0.6539 | 0.2713 | 1.9935 |

| LOG10(7)-WT | 0.9855 | 0.07629 | 7.9131 | 0.7128 | 0.2499 | 1.9451 |

| LOG10(8)-WT | 0.9903 | 0.0622 | 9.8016 | 0.6848 | 0.2641 | 2.1209 |

| LOG10(9)-WT | 0.9841 | 0.079 | 7.4682 | 0.7519 | 0.2475 | 2.0846 |

| LOG10(10)-WT | 0.9884 | 0.0674 | 9.4681 | 0.5221 | 0.3453 | 1.8356 |

| LOG10(11)-WT | 0.9932 | 0.0512 | 12.0039 | 0.6781 | 0.2944 | 1.9454 |

| LOG10(12)-WT | 0.9859 | 0.0744 | 7.973 | 0.6154 | 0.3069 | 1.471 |

| LOG10(13)-WT | 0.9857 | 0.0749 | 7.9207 | 0.7387 | 0.2538 | 2.1009 |

| LOG10(14)-WT | 0.9925 | 0.0539 | 11.2775 | 0.7191 | 0.2691 | 2.0034 |

| LOG10(15)-WT | 0.9912 | 0.0595 | 10.517 | 0.5298 | 0.3211 | 1.6004 |

| Preprocessing Method | Training Set | Validation Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | RPD | R2 | RMSE | RPD | |

| CNN | 0.9182 | 17.9361 | 3.4976 | 0.8322 | 20.3567 | 2.4412 |

| LSTM | 0.8975 | 20.076 | 3.1247 | 0.828 | 20.6073 | 2.4115 |

| BiLSTM | 0.8977 | 20.0609 | 3.1271 | 0.8052 | 21.9302 | 2.2661 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.9217 | 16.9903 | 3.8575 | 0.8569 | 18.2426 | 2.7052 |

| BWO-CNN-LSTM | 0.9403 | 15.3225 | 4.0941 | 0.8887 | 16.5722 | 2.9987 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, C. Prediction Method of Available Nitrogen in Red Soil Based on BWO-CNN-LSTM. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11077. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011077

Deng Y, Cao Y, Liu C. Prediction Method of Available Nitrogen in Red Soil Based on BWO-CNN-LSTM. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11077. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011077

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Yun, Yuchen Cao, and Chang Liu. 2025. "Prediction Method of Available Nitrogen in Red Soil Based on BWO-CNN-LSTM" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11077. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011077

APA StyleDeng, Y., Cao, Y., & Liu, C. (2025). Prediction Method of Available Nitrogen in Red Soil Based on BWO-CNN-LSTM. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11077. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011077